The struggle for Vietnam was the crucible of the second half of the twentieth century. As the chapters in Volume I illustrate, the decades-long conflict over the fate of Vietnam centered on disputes about the fundamental essence of international life in the twentieth century – sovereignty, imperialism, development, nationalism, communism – and unfolded as a war of decolonization during the transition from World War II to the Cold War, thus bridging the events that carved the main features of the century. These same dynamics continued into the 1960s, making the five-year period covered by Volume II – from the end of 1963 to the end of 1968 – the hottest part of the twentieth-century crucible, where ideologies melted, fused, and were transformed into a new international system.

Vietnamese nationalists of various kinds had been fighting to determine the future of their country for several decades before 1963, but the escalation of US involvement in the conflict forced a reckoning on all sides. The major American combat phase of Vietnam’s modern history commenced no earlier than 1961, and really not until 1964–5 when Lyndon Johnson crossed two previously unmet thresholds: large-scale bombing of North Vietnam and the deployment of hundreds of thousands of ground troops not simply to support and advise the South Vietnamese military but with the explicit aim of taking the war directly to the enemy. Volume II thus examines the escalation of the conflict, driven by an accelerating action–reaction cycle of rapidly intensifying military commitments by the United States on one side and North Vietnam on the other as they contested for the future of South Vietnam. This process of escalation culminated in 1965 and changed the character of the war irrevocably. A stalemated war ensued, leading to a three-year impasse that did not break until the Tet Offensive of January–February 1968 triggered the beginning of the end of American intervention, a tortuous process that is covered extensively in Volume III. Just as this 1963–8 period acted as the catalyst for major changes in Vietnam, the United States, and beyond, Volume II acts as a hinge between the origins of the Indochina wars examined in Volume I and the prolonged end of war explored in Volume III.

Volume II is divided into three parts, each covering an ever expanding geographical sphere of inquiry. The first part, “Battlefields,” examines the war itself, on the ground and in the air in Vietnam. The second part, “Homefronts,” explores the domestic sides of the conflict in the two Vietnams as well as the United States. Although “domestic” is perhaps not the most appropriate term to describe the Vietnamese homefronts, given that the fighting could never be truly separated from Vietnamese civilian life, it is meant to convey those aspects of wartime conditions that were not dedicated to the pursuit of victory in a contest of arms. This second part, then, explores three separate but violently interlocking societies as they grappled with the demands of war while also trying to maintain alliances, handle political turbulence and antiwar dissent, address probing issues concerning race, ethnicity, and gender, and attain a measure of social security for their citizens. The third part, “Global Vietnam,” zooms out to trace the international dimensions of the American war in Vietnam. The conflict had a profound effect not only on the societies directly at war but also on the international system itself: socially, culturally, politically, and economically. Together these three parts, each a concentric circle expanding outward from the two Vietnams, to Vietnam and the United States, to the world at large, aim to give readers a comprehensive but analytical overview of the causes, conduct, and consequences of the American war in Vietnam.

Battlefields

Vietnamese and Americans contested the fate of Vietnam in many places – in the media, in parliaments and capitals, in the home, and, in Johnson’s famous phrase, in the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people – but most obviously it was a contest that was fought, literally, on the ground, in the water, and in the air in Vietnam. From the beginning of this volume to its end, warfare shaped everything else. Initially, the conflict brought about greater and greater levels of American intervention until the US military took over effective control of fighting from the South Vietnamese in 1965. This is when the conflict embodied the name most commonly used by Americans: the Vietnam War. Fittingly, then, the conflict was also nicknamed after some of its main architects, most notably “Johnson’s War” after President Johnson, “McNamara’s War” after Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, and “Westmoreland’s War” after General William C. Westmoreland, the overall US military commander in Saigon.Footnote 1

Yet despite the US-centered nature of much of the war’s historiography and terminology, understanding the escalation of the conflict in South Vietnam requires an appreciation of the tactics, strategy, and morale of all four main sides of the war – the communist Democratic Republic of (North) Vietnam (DRVN); its communist–nationalist surrogate in South Vietnam, the National Liberation Front (NLF); the anticommunist Republic of (South) Vietnam (RVN); and the United States – and how they reacted to and interacted with each other in combat. This, in turn, offers a greater comprehension of the course of the war and how such an advanced military superpower as the United States could lose to such (supposedly) overwhelmingly outmatched adversaries.

When the presidents of South Vietnam and the United States were assassinated within three weeks of each other in November 1963, the conflict was still at a fairly low but slowly growing level. The insurgency against Ngô Đình Diệm’s government in Saigon had grown dramatically since its launch in the late 1950s, and Diệm’s rule became untenable through the summer of 1963 when Buddhist protest piled on top of armed insurgency. Yet compared with the Korean War, or with the anticolonial insurgency in Algeria that had ended in 1962 – or, indeed, with the French Indochina War that ended in 1954 – the second war for Vietnam was still a limited affair in late 1963, still in its origin stage. This all changed with the instability that resulted from the deaths of Diệm and John F. Kennedy. The communist insurgency in the South picked up pace, and in 1964 military forces from the North intervened directly. Saigon was gripped by chronic political instability for more than a year and a half following Diệm’s assassination, and by the summer of 1965 it appeared that South Vietnam itself might succumb and cease to exist. Under Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, the United States responded to communist escalation and provocation: at the time of Kennedy’s death, just over 16,000 US military personnel were stationed in Vietnam with an ill-defined advisory role, but in March 1965 Johnson authorized the first deployment of regular ground forces: 8,000 marines who waded ashore at Đà Nẵng. The peak total of US troops in South Vietnam continued to increase each year until more than 530,000 Americans were stationed there by the time Richard Nixon won the presidential election of 1968.

The air war escalated even more quickly. Under Kennedy, there had been no campaign from the air that accompanied the gradual increase in US military advisors on the ground; the only significant aerial activity came in the form of helicopters supporting ground operations. Even after Johnson assumed the presidency, the US Air Force and US Navy did not immediately begin major aerial operations. This changed dramatically in February 1965, beginning with the shift from mounting one-off retaliatory strikes against targets in the DRVN – such as against two small North Vietnamese naval installations following the Tonkin Gulf incident in August 1964 – to a policy of “sustained reprisal,” or continuous bombing of the DRVN for an indefinite period. The signature policy of this new strategy was Operation Rolling Thunder, which commenced in March 1965 and continued, aside from occasional pauses to allow space for diplomatic negotiations, until November 1968.

Be it on the ground, on the water, or in the air, the war did not go as planned for the United States. Among most US military strategists and tacticians, there was little overconfidence that the war would be easily won; they always appreciated just how challenging the fighting would be on difficult and unfamiliar terrain against an enemy who was battle-tested, disciplined, and motivated. But the sudden stalemate that raised prospects of defeat, even after the United States had committed its monumental resources in 1965, was unexpected all the same. On the ground, US forces made little headway against an elusive enemy, and their tactics, particularly at the village level, drew increasing resentment among South Vietnamese civilians. While historians have begun to revise their views of General Westmoreland, it remains clear that the ground war was difficult from the start and had only limited success. The same was true of the air war. Destructive though it was, it was already clear by the autumn of 1965 that Rolling Thunder was failing to achieve any of its three main objectives (to stop infiltration from the North, to deter the North from prosecuting the war, and to instill confidence and thereby create political stability in the South), and the bombing campaigns in the South fared little better in stifling the insurgency. When the Tet Offensive hit in early 1968, it dealt a decisive blow to American willingness to continue the war, even though at the tactical level it was a clear defeat for communist-led forces. Reeling from the effects of an unexpected offensive that the enemy was allegedly too weak to pull off, which itself followed three years of frustrating stalemate and political crisis, on March 31, 1968, President Johnson announced he would not seek reelection in the fall and would use his remaining time in office to end the war.

The difficulties US forces confronted led, at the time and ever since, to the scapegoating of their South Vietnamese ally. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) came in for particular criticism for a lack of cohesion, tactical ineptitude, and even cowardice. When US-based historians of the war paid any attention to the ARVN, it was usually to highlight these pernicious traits. However, thanks to more recent historical research, including by contributors to this volume, we now have a better appreciation of the complexities the ARVN faced, as well as the successes it achieved. Just as Westmoreland has come in for a more nuanced reassessment, historians now appreciate that the ARVN must be taken seriously as a central actor in its own drama.

The United States and South Vietnam were of course not the only sides in the conflict, nor were US forces the only ones driving the escalation of the war. Devastating as it was to Vietnamese on both sides of the 17th parallel, the war served communist needs as well. Political infighting in Hanoi, within the Central Committee of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP), resulted in hardliners led by Lê Duẩn taking control not long before Johnson escalated the war and Westmoreland took the fight to communist forces on the ground. The NLF, beholden to Hanoi, increased the pace and intensity of its operations in 1964–5, which in turn prompted further US escalation. When Lê Duẩn decided that national reunification could be achieved only through total victory, despite Johnson making it clear that Washington would not tolerate the loss of South Vietnam, a larger war became unavoidable. Thus around this time Hanoi also increased its own direct participation in the ground war, sending full People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) units to the South and, from the autumn of 1965, engaging in direct combat with US troops. In November 1965, the battle of Ia Đrӑng, in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam, established a pattern that would define the war through to the Tet Offensive: intense fighting with ostensibly a US victory but ultimately an inconclusive result with casualties that, while heavy on both sides, were ultimately less sustainable over the long term for the Americans.

By 1968, were the United States and South Vietnam losing the war? Or were the DRVN and NLF responsible for executing a strategy to win it? The answer to both questions is the same: yes. But that is only because the military traits of both sides were inversely matched, so that what should have been US advantages were actually crippling disadvantages, and what should have been DRVN/NLF disadvantages were actually decisive advantages. Supposed American strengths – the technological sophistication of its weapons and logistics, the firepower of its arsenal in all spheres of battle, the sheer amount of hardware at its disposal that was constantly fed into the theater of operations by transoceanic supply chains, its economic wealth – were largely irrelevant in an unconventional war that was fought with no frontline. More than this, US strengths were actually often liabilities, particularly in the global and political arena, but most especially in the economic and military support it provided South Vietnam, which simply distorted Southern society and blunted the ARVN’s military effectiveness. By contrast, the communist forces’ supposed weaknesses – the lack of an industrial base, a nimble and relatively light footprint in battle, a smaller arsenal, the lack of matching air power – were actually strengths, ideally suited to the geographical terrain and politicized nature of this particular conflict. While it is true that the DRVN received large amounts of war materiel and other aid from the Soviet Union and China, enabling the North Vietnamese to boast one of the most effective air-defense systems in the world, the disparity between its resources and the combined resources of the United States and South Vietnam was stark. The war was a mismatch, then, but not in the way many observers assumed when Johnson committed the United States to war in 1965.

That the war was frustratingly, infuriatingly difficult for the US military is reflected in many of its singular curiosities. Consider, for example, the sheer scale of the bombing of both Vietnams: between 1965, when the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign against the North began and several simultaneous ongoing bombing campaigns against communist targets in the South commenced, and 1968, US forces dropped about the same amount of bombs in Indochina as was dropped over Europe during World War II. For comparison, that is as if every single bomb dropped in Europe during World War II was dropped only on Poland, a country of roughly comparable size to the two Vietnams. Even more curious was the fact that because the ground war took place almost entirely in South Vietnam, the United States inflicted more damage on its ally than on its enemy in the North – including from the air. Of total US bombing between 1965 and 1968, 60 percent was dropped on allied South Vietnam, at a rate more than two-and-a-half times greater than on North Vietnam. In 1968 alone, the United States bombed South Vietnam more heavily than it did the entire Pacific theater in World War II.

The ultimate outcome of the war – a clear military and political defeat for the United States – has led to a series of historiographical controversies about how the United States conducted the war between 1965 and 1968 that all center around the question of whether it could have won had it used different tactics or a different overall strategy. Should US commanders have adopted a less conventional approach that placed greater emphasis on counterinsurgency? Or, by contrast, did they pay too much attention to guerrilla warfare and therefore fail to hit the enemy as hard as the US military could have? Though they are in diametric opposition with one another, both of these arguments are ultimately unprovable because they rest on a counterfactual analysis that can never be corroborated with evidence. Yet a small number of historians contend that counterfactuals are not even necessary because, contrary to media coverage at the time and most of the historical literature published since, by 1963 the United States and South Vietnam were in fact winning the war militarily, only for feckless civilian politicians and officials to throw away the military’s hard-won advantages. This amounted to a “triumph forsaken” that had to be “regained” through the Americanization of the war, according to a leading advocate of this view.Footnote 2 These and other controversies surrounding US military effectiveness are explored in the chapters that follow. Overall, however, the general conclusion of this volume confirms the view that the war was a military defeat for the United States and South Vietnam, and that defeat was virtually impossible to avoid for reasons that were endemic to the type of warfare that occurred.

Homefronts

All wars are political, as the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz observed two centuries ago, but few wars have been as intensely, thoroughly political as the Vietnam War. To an unusual extent, politics about the war conditioned, and in some instances even determined, the course of the war itself. This was the case especially in South Vietnam and the United States, though even the homefront in North Vietnam, a much more closed and politically repressive society, influenced the war in important ways.

Unsurprisingly, as the main site of battle, South Vietnam’s society was particularly roiled by the war. The military was the central actor in South Vietnamese political life, with most of the government leadership drawn from the ranks of the army and air force. Under President Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu (an ARVN general), the authoritarian government in Saigon tried to rule with unquestioned authority. But this was impossible in practice as too many South Vietnamese, in particular a highly activist Buddhist political movement that acted as a kind of unofficial opposition party, continually questioned the government’s handling of the war. The result was a constant state of surprisingly open political contestation that was, ironically, usually characteristic of liberal democracies.Footnote 3 Constant meddling by the US Embassy in Saigon only added to South Vietnam’s chronic political instability. Indeed, the irony of the American presence in South Vietnam was that, while it staved off defeat to the communists, it also led to constant economic turbulence and ever deepening inequality, and a growing divide between the cities that prospered from the US presence and the rural areas that saw little economic gain but most of the fighting in the intensifying war. Just like its military, the RVN government was a more autonomous actor than historians have previously appreciated, but US involvement in the country was simply too overwhelming, and the war too profoundly destabilizing, for the country to find the sure footing it needed to survive.

Even though there was no actual combat in the United States, American society was no less consumed by the war. Defending South Vietnamese independence was never a popular cause among Americans, and though there was no significant antiwar dissent until 1965 there was not much genuine support either, at least not during Johnson’s presidency. Nearly two decades of the Cold War had created widespread deference to presidential war powers and a passive acceptance of anticommunist foreign policies, but this was not the same thing as enthusiasm, or even determined support, for military intervention in Southeast Asia. As the war in South Vietnam escalated and triggered increasing levels of US commitment, public opinion became more attentive but deeply ambivalent. Sensing this lack of commitment, Johnson escalated US involvement incrementally, and surreptitiously, in order to avoid a public debate on whether going to war was a good idea. Moreover, Johnson worried about the war’s effects on his domestic reform program, known as the Great Society, because the financial and political costs of waging war could lead Congress to reduce discretionary domestic spending. Johnson was not about to let South Vietnam be defeated, however, and so he tried to have it both ways by launching the Great Society with a lot of fanfare while escalating military intervention with a lot of subterfuge.

This strategy could work only as long as US military involvement was kept to a minimum, or as long as South Vietnam was not in danger of losing the war, but both conditions had become impossible by the summer of 1965. Johnson’s strategy of “guns and butter” might have worked had the war gone well for the United States and South Vietnam, but from the outset the war did not go well. Instead, it required greater and greater levels of direct US combat involvement, thus prompting greater and greater levels of spending as well as increased economic support for South Vietnam, in turn leading to successive waves of ever growing domestic opposition to the war. Probably a majority of Americans were not enthusiastically supportive of the war even if they were willing to give the president the benefit of the doubt, and with it their political backing for his policies. To be sure, there were many Americans who actively supported the war in Vietnam, but while they could be vocal they were often outnumbered by the war’s opponents. Large outbreaks of protest began in 1965 among university students and religious leaders, but they did not coalesce into a mass movement until 1966 – not coincidentally when the war had clearly stalemated and US tactics had raised concerns about their morality as well as effectiveness. The year 1967 brought larger protests still. Even more important was the deepening of antiwar protest, which radicalized in method, tone, and substance to the point that, by 1968, Americans were asking themselves if they were in the midst of their own civil war.

There probably would have been some kind of antiwar dissent even in normal times, but the 1960s were hardly normal times. Unease about the war in Vietnam intersected with existing social protest movements about racial discrimination and gender inequality. The intersection of these movements, which began separately and sprang from distinct sources, created a rich environment for the emergence of an unusually intense moment of contentious politics.Footnote 4 Frustration, even outrage, about the war then catalyzed the fervor of these protest movements to surprising and unprecedented levels. At the same time, the American media landscape was also changing, as journalists and editors became less willing to automatically accept the administration’s explanations and more willing to conduct their own critical investigations into the administration’s policies. Moreover, not only did this rare period of such widespread contention and media controversy reshape American society, it also affected the prosecution of the war itself by constraining what Johnson could authorize his military commanders to do in the field and by eroding the public’s normally deferential support for a president at war. Historians remain divided about the extent to which antiwar protest, other aspects of the era’s politics of contention, and the media forced Johnson to search for a way out of Vietnam. But there is no doubt that any accounting of the Vietnam War must carefully consider the social and political turbulence of US society.

Whether contested homefronts cost South Vietnam and the United States the war is open to debate, but what is clear is that domestic difficulties affected Saigon and Washington’s ability to wage war. By contrast, North Vietnam had it relatively easy: a quiescent public that had little choice but to be supportive of the war, a government in Hanoi that was often fractious but could keep its factional struggles hidden from public view, and an easily comprehensible and widely supported goal of national reunification under communist rule. While the VWP could never just assume it held social and political legitimacy, and had to work to maintain it, there was simply no space in the North for any kind of public discussion on the war, let alone the emergence of the contentious politics that defined public life in the South, and rare instances of public dissent were quickly suppressed. Still, the DRVN economy, already in a parlous state due to the disastrous central planning the government had imposed before 1965, suffered terribly under the concussive pressure of US bombing, and the exigencies of war meant that the people of North Vietnam regularly had to go without to an extent that was unthinkable even in the South, let alone the United States. Such hardships were as much a part of life in the DRVN as any kind of ideological commitment or nationalist objective.

Global Vietnam

American and Vietnamese newspapers, universities, governments, homes, streets, and cafes were not the only sites of contestation about the war. The young antiwar demonstrators in Chicago who picketed the 1968 Democratic National Convention did not exaggerate when they chanted, “The whole world is watching!”Footnote 5 While the war was contested primarily in the two Vietnams and the United States, it was also an international political conflict – more so, perhaps, than any major war since 1945. Most of the world did not participate militarily in the Vietnam War – although some countries did, especially US allies in the region – but most of the world did observe the war with a passionate interest that did not diminish over time. Other regional wars have acted as crucibles for larger global trends – the Spanish civil war of 1936–9, the Syrian civil war since 2011, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 come to mind – but, by perfectly capturing so many of the world’s pressing concerns over economic and political development and intercultural relations, since 1945 no other major war has grabbed the world’s attention like the American war in Vietnam.

The antiwar dissent seen in South Vietnam and the United States had counterpart movements around the world that not only criticized the belligerents but also pressured their own governments not to participate in or even support the anticommunist cause. This was, ironically perhaps given their solid commitment to military ties with Washington on virtually all other issues, especially notable among US allies in North America and Europe, and to some extent in a more ambivalent Japan. The countries of the Global South naturally saw their own struggles for independence reflected in the fate of Indochina, and in many cases they joined in the widespread condemnation of the war, particularly US intervention. This large, diverse group of critics included not only Soviet and Chinese allies, such as Cuba and North Korea, who lent material and political support to North Vietnam, but also nonaligned states like India and pre-1965 Indonesia that sought neutrality in the Cold War. This widespread group of people, in all regions of the world and counting both US allies and adversaries, gave rise to a richly diverse transnational antiwar movement that established a presence on every continent.

But two of the primary ideological concerns being contested in Vietnam led other countries to take a different position, one that supported US war aims. The first of these ideologies was self-determination, which had been the gold standard of international conduct (even if it was often honored in the breach) since both Vladimir Lenin and Woodrow Wilson had unveiled their very different manifestos for national self-determination during World War I.Footnote 6 For some countries emerging from the grip of European imperialism, the sanctity of the self-determination principle meant that the DRVN had the more legitimate claim to statehood for all of Vietnam. But for other countries with a similar colonial past, South Vietnam had a rightful claim to independent self-government that should be protected even to the point of war.

Not coincidentally, most of the governments that took this pro-RVN view – including South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and the Philippines – were fierce adherents to the second ideology at war: anticommunism. New states emerging from decolonization into the cauldron of the Cold War faced a choice between two types of political and economic development: the Soviet model of anticapitalist socialism, perhaps even full-bore communism; or the American model of procapitalist, market-oriented liberalism that could be amenable to social democracy but not to communism.Footnote 7 However, although some may have paid lip service to American ideals, few new states formed after 1945 actually chose liberal developmentalism and instead moved much further to the right to establish pro- or semi-capitalist regimes that were a blend of authoritarianism and corporatism and always expressed as ferociously pursued anticommunist politics. These new states that turned away from socialism and communism (not coincidentally, some of them, such as South Korea and Taiwan, had also been divided by the Cold War) were not simply philosophically noncommunist but stridently, unwaveringly, violently anticommunist: to them, communism represented not just the ultimate evil, but a very real ultimate threat. Unsurprisingly, they saw a bit of themselves, and their own security concerns, in South Vietnam’s fight for national survival against communist imperialism, and they helped Washington build an “arc of containment” in Southeast Asia.Footnote 8 Indonesia is an indicative case study of the overriding salience of regional communism/anticommunism: opposed to the United States and South Vietnam and supportive of China and North Vietnam before 1965, then supportive of the United States and South Vietnam and opposed to China and North Vietnam after the bloody purge of the Communist Party of Indonesia that began in October 1965.Footnote 9 To varying degrees, other nations in the region that did not have a recent colonial past but were anticommunist US allies, such as Thailand, Australia, and New Zealand, also sent troops to fight alongside the South Vietnamese and Americans. Under its “More Flags” program the Johnson administration encouraged, and for some countries even subsidized, allied military intervention in South Vietnam. Even though they grew to approximately 10 percent of US force levels by 1968, the collective difference these third-party allies made was negligible and certainly did not affect the outcome either way except to accentuate the inherent problems the US military already had to deal with.Footnote 10 By contrast, dozens of other countries, many of them also US allies such as Canada, but also US adversaries such as the Soviet Union, sponsored third-party peace initiatives in an effort to bring the war to an end.

The war in Vietnam had other global consequences. It contributed to ruptures within the transatlantic alliance and, even if the damage to American leadership of Western security was temporary, it was profound nonetheless. The war also helped cleave the communist world in two, with Moscow and Beijing holding ever diverging perspectives of what was to be done in Vietnam. The Sino-Soviet split, which broke wide open just as the United States was taking control of the anticommunist war effort, had far-reaching, long-lasting effects that would eventually contribute to the ending of the Vietnam War itself. The US war had major international economic consequences as well, helping to stimulate the economies of several countries in the region – not least Japan but also South Korea – while at the same time contributing to the overheating and then stagnation of the US economy, and by extension catalyzing the process of deindustrialization that would utterly change the character of American society from the 1970s to the present day.

Overall, then, the ongoing escalation of the war in Vietnam from 1963 to 1968 had a profoundly formative effect not just on Indochina but on international history writ large. The war helped spur regional integration in Southeast Asia along predominantly capitalist, strongly anticommunist lines. It facilitated the economic transformation of East Asia, establishing the conditions for spectacular economic growth not just in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, but eventually also in the People’s Republic of China. As the first major military defeat for the United States in 150 years – a result that was already evident by 1968 – and as one of the signature moments in the Cold War when a decolonizing country was in the process defeating a militarily superior foreign enemy, the war further fueled the fires of national liberation and revolutionary movements worldwide. By stoking protest movements globally, the war led millions of people, and often their governments, to reconsider what was legitimate in the conduct of international relations and to rekindle interest in human rights and the laws of war. Finally, the Vietnam War altered the course of US history and changed the very social and cultural fabric of American society. To paraphrase one of Volume II’s major figures, Martin Luther King, Jr., if the contemporary world order has a product label attached, it must read, “Made in Vietnam.”

Map 0.1 Indochina, Thailand, and southern China during the Vietnam War.

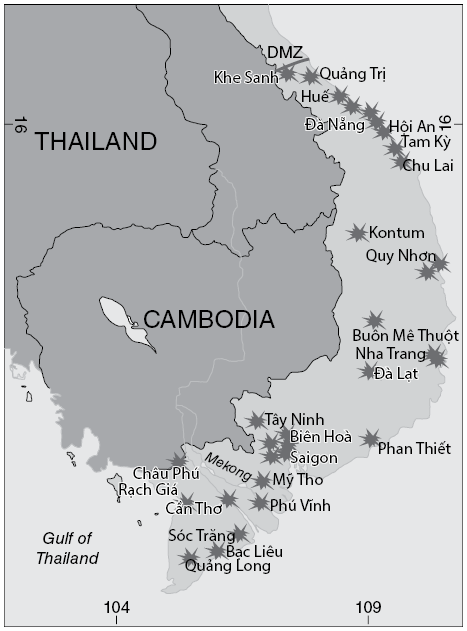

Map 0.2 The Corps Tactical Zones (CTZs) designated by the armed forces of the United States and South Vietnam.

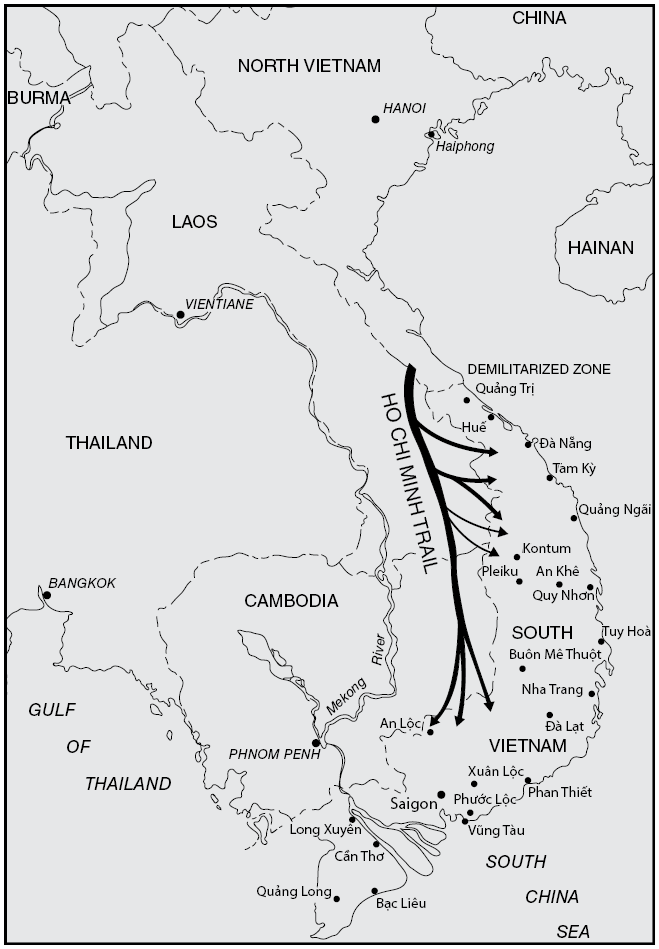

Map 0.3 The DRV/NLF supply route, known as the Hồ Chí Minh Trail, from North Vietnam to South Vietnam.

Map 0.4 The Tet Offensive, 1968.