Race pervades the history of the United States. It has been a powerful historical actor and, as such, played a critical role in the execution of the Vietnam War. Racism long defined what was possible for American people of color. By the time the United States had committed nearly half a million troops in Vietnam, however, racism had been discredited in scientific circles, and segregation as a national institution had been formally abolished. With white supremacy no longer acceptable as an ideological support, US policymakers could not permit racism as an acknowledged presence in foreign conflicts and interventions. At home, race remained a preoccupation because not all Americans accepted the challenges of an integrated society. Abroad, it had to be made illegible.Footnote 1

This chapter defines race as an assemblage of traits based on perceived physical appearance and ancestry. As a term of classification, it has little scientific value. Race has considerable social salience, however, as a marker from which various assumptions may be made. Racism uses perceptions about physical traits and beliefs about descent to erect a system of hierarchy based on difference. Perceived cultural deficits have also been racialized as characteristic of people deemed inferior. Racial hierarchy organized chattel slavery in the United States. After the abolition of slavery, it was reconfigured to support a system of racial segregation embedded in the economic and political structures of American life.

Prevalent ideas about race widely circulating throughout the Western world buttressed segregation. Belief in the inequality of races had justified the Western conquest and economic exploitation of African and Asian lands and undergirded American Caribbean and Pacific conquests at the turn of the twentieth century. In the years between the world wars, French colonial practice envisioned a Vietnamese inferiority rooted not only in culture but also in bodily traits. American officials, like French colonialists, saw Asians through a buckled mirror of both cultural and racial distortion. Once engaged in World War II, belligerents on both sides of the Pacific theater racialized their opponents: the squat, bucktoothed Japanese officer of Hollywood fame had his counterpart in Tokyo’s projection of pale, snarling US troops.Footnote 2 These distortions reverberated in the Vietnam conflict.

France in the American War

The racial narrative of US intervention in Vietnam starts with France. The French mission in Indochina began as a gradual process of colonization in the mid-nineteenth century. It embodied then-current orientalist ideas about culture and environment. To establish a permanent presence in a region that many Western commentators believed unsuitable for white people, French colonial administrators sought to encourage the acculturation of Asians and focused particularly on Eurasians. Generations of soldiers, officials, and merchants had sired children with Indochinese women. The job of “rescuing” these children was cloaked in humanitarian impulses but also aspired to create a “middleman minority” that would be loyal to France. This practice differed from that of such colonial powers as Britain and Germany, which tried to maintain clear status differences between white people and others. While French administrators viewed Southeast Asians as racial inferiors, they thought that mixed-race individuals could be redeemed, at least as a subject population. In a combination of callousness and paternalism, social workers canvassed the Vietnamese countryside in search of Eurasian children who looked white. They went so far as to forcibly wrest from their Indochinese mothers children whose French fathers had not claimed them. The children’s new homes would be state-supported orphanages run by private entities. Similar policies had been enacted in Canada, Australia, and the United States, where aboriginal youth were inducted into boarding schools that suppressed indigenous languages and limited students’ contact with their families. As in Vietnam, finding obedient, acculturated subjects was the goal.Footnote 3

In 1945 Vietnamese nationalists began a war of independence from France that troubled the United States because of the communist affiliation and radical nationalism of the Việt Minh and the region’s proximity to unsettled conditions in China. After the Chinese Revolution of 1949, the Cold War became a significant factor, suggesting to US policymakers that Southeast Asia had to be secured for the West. The United States accordingly supplied France’s Indochina War with money and materiel. France fought this war with a largely colonial army. One historian suggests that as little as 10 percent of the fighting force was French. Instead soldiers from Africa comprised nearly a third of the Far Eastern Expeditionary Corps and contributed to a mixed-race population in Vietnam. Following the French defeat in 1954, Washington began gradually to displace Paris politically, culturally, and militarily.

America on a Mission

American leaders were uncompromisingly anticommunist, but some had doubts about extensive involvement in Southeast Asia. They differed over the extent to which foreign aid should be offered to fragile economies, the wisdom of pursuing military action on the Asian continent, the degree to which military action should proceed without congressional consent, and the extent to which global policing should take priority over homeland defense. These disagreements were overcome when proponents of intervention in the region achieved a rough consensus by defining their mission as noncolonial.

The United States did not perceive itself as imperialist and deliberately sought to distinguish its interest in Vietnam from that of France. It had comparatively few territorial possessions, and government officials sought to deny imperialist ambitions. After the Spanish–American War the United States granted formal sovereignty to Cuba; it withdrew its Caribbean protectorates during the Great Depression, restored Philippine sovereignty in 1946, and retained the Trust Territory of the Pacific for geostrategic reasons. Americans intended imperialism for practical purposes only. Intervention in Vietnam similarly would not be for territorial aggrandizement. Having emerged from World War II without significant civilian casualties or major damage to infrastructure, the United States had the resources to pursue its Southeast Asian program. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State John Foster Dulles did not believe France was up to a comparable task. France’s defeat by Vietnamese nationalists at Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, the precariousness of the French Fourth Republic, and the concurrent Algerian War encouraged Washington’s determination to substitute French domination in Vietnam for American hegemony.Footnote 4

While US officials did not think they were replacing one form of colonialism with another, and were only doing what was necessary to block communist advances in Southeast Asia, their program in Vietnam took on both the appearance and the substance of practices earlier put in place by France. Both countries, for example, used language instruction as a strategic instrument. French was perceived as a cultural adhesive binding colonial subjects to the metropole. Later, as Americans claimed they came to Vietnam without a colonial agenda, they presented English-language instruction as simply a Cold War necessity. Anticommunism and the desire to promote modernization provided the chief rationale for their involvement. English was the lingua franca of technical assistance and development initiatives. This offended French officials who wanted the United States to function in Vietnam without usurping the historic role of the French language. A similar situation occurred in Congo in 1958 when Belgian officials became alarmed at the growing activity of the United States Information Service. This included not only the provision of English-language publications but also instruction in that language. Belgians clearly saw their influence as tied to the continuing predominance of French. The belief in American technical superiority was tied to the desire to spread the use of English.Footnote 5

The United States had no history of continual intervention in Southeast Asia as it did in Central America and the Caribbean. It defined its goals in Asia differently. A focus on modernization tied its foreign and domestic policies together in the 1960s. President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society and Vietnam pacification schemes had common roots in Progressive Era and New Deal reform. Plans to win over Vietnamese through major infrastructural projects and food programs represented an effort to internationalize reform and were premised on the desirability of uplifting populations perceived as backward and deficient. Despite missionary overtones, by the mid-twentieth century science rather than religion was the driving ideological force underwriting the technology of progress. Many nationalists in newly independent countries also embraced the doctrine. Race, at first glance, would seem unimportant in this context.Footnote 6

Modernization theory held that development, including industrialization and the growth of democracy, could be instituted and tracked scientifically. When proponents made invidious comparisons between Western and non-Western societies, space was left to reintroduce racial ascriptions and the culturally laden binaries latent in modernization thought. Target populations were urged to abandon putatively backward-looking habits, as tribalism was contrasted to civil society, tradition to modernity, communal life to individualism, and so on. Under the coercive circumstances imposed by the Vietnam War, the voluntary and cooperative aspects of modernization began to fade. Combat disrupted agricultural production, a staple of development, as a country once self-sufficient in rice now imported it from the United States. Some of the most ambitious programs, including farm aid and a development bank, fell prey to corruption. The American mission in Vietnam by the late 1960s came close to approximating France’s classic mission civilisatrice.

Race and the Military

The military was the preeminent agent of US power in Vietnam, although personnel on the ground included both civilians and soldiers. Race played a role in how the armed forces functioned in that country and in other theaters that supported the war effort. Less than twenty years separated the beginning of the Vietnam War and President Harry Truman’s 1948 executive order desegregating the armed forces. The military had previously placed African Americans in separate units, provided them with inferior equipment, and largely confined them to menial, noncombat pursuits. Many officers held a low opinion of Black soldiers, perceiving them as unintelligent and fit only for labor rather than for combat. In the navy, African Americans could only be cooks and stewards. The Marine Corps recruited a Black battalion in 1942 but kept it in camp until the war was almost over. Only afterwards did the marines name two officers, in 1945 and 1948 respectively, but gave them no units to command. There were success stories, like the specially trained Tuskegee airmen, but for most Black troops military service made the perception of injustice more acute. A particularly stinging experience occurred when Black soldiers guarding German POWs after World War II had to wait outside restaurants that served the Germans but barred them. These humiliations officially ended in 1948 but traces of Jim Crow persisted.Footnote 7

Just as Truman’s reforms were based on the stance that all soldiers were Americans and should be treated equally, they were also founded on the principle of unquestioning loyalty to the republic. But the civil rights insurgency, which increased dramatically after the war, began undermining the implicit rule against criticizing the country. Racial disparities could no longer be ignored, and conscription that converted citizens into soldiers meant a flow of ideas between the homefront and military sites. The Vietnam War exposed the clash between conventional civic ideology and the reality of Black second-class citizenship.

Racial conflict in the US military during the Vietnam War occurred everywhere that bases were located. The circulation of troops between Vietnam and these locales meant that soldiers were drawn into the conduct and the ethos of the war wherever they were. In Germany, Black troops protested negative experiences they endured as 13 percent of the 165,000-member 7th Army. Although racial conflicts occurred at US bases everywhere, Germany ranked highest for incidence and seriousness. Targeted for discrimination by white personnel and German civilians alike, African American GIs often found themselves barred from off-base housing. Some Germans routinely refused to serve Black soldiers in bars and restaurants and complaints to the US top brass were unavailing. Black servicemen were disproportionately subjected to nonjudicial punishment and arrest and numbered at least half of those imprisoned in stockades. They challenged discrimination in promotions, assignments, and the dispensation of justice. They complained about the open display of Confederate flags, cross burnings, and efforts by white soldiers to organize Ku Klux Klan chapters. Further causes of disaffection included poor leadership by ranking officers, their scarcity in the officer corps, and minority underrepresentation in the military police. While African Americans faced discrimination in other countries, the presence in Germany of the US 7th Army’s bases and their salience to the Cold War, combined with the remaining memory of the Third Reich, aggravated tensions. By 1970 racial conflicts in Germany had escalated, along with a general deterioration of morale. Observers noted a growing insolence and independent spirit among US soldiers generally. Antiwar newspapers emerged, evidently printed secretly on base. The banning of GI meetings and arbitrary punishments did not appear to stem the tide of dissidence.Footnote 8

African American troops in Germany were attuned to the Black Power movement at home. Many adopted Afros despite military rules that ordered short haircuts. Peace signs appeared. Soldiers wore pendants and other symbols of Black militancy that challenged customary uniform codes. The initial response of the authorities to this behavior was to suppress knowledge of the gravity and frequency of both peaceful protest and violent resistance. They did so by censoring publications, an action that suggested that more incidents occurred than were reported. By 1970, increased racial friction posed an image problem for a nation attempting to shore up its credibility in Vietnam and represent the armed forces as colorblind institutions.

President Richard Nixon responded by sending a delegation headed by Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense Frank Render II to Europe to investigate racial conditions at US bases. The subsequent Render Report recorded the “frustration and anger” of Black soldiers. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird then ordered base commanders to set timetables for the elimination of all bias on bases and in surrounding communities. The report may have arrived too late and contributed too little, failing to avert a mutiny in the 7th Army late in 1971.Footnote 9

Foreign outposts were not the only sites of unrest. In Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, tacit housing discrimination practiced by local businesses with the acquiescence of resident top brass added to rising racial tension. In 1969, a white marine from Mississippi stationed at Lejeune was killed in a fight with a group of African American and Puerto Rican marines. Violence erupted in Hawai’i when white soldiers contested fifty Black marines who raised their fists in a Black Power salute at a flag-lowering ceremony.Footnote 10

According to congressional testimony by Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, commander of naval forces in Vietnam, long deployments, personnel shortages, and crowded shipboard conditions contributed to mutinies by Black sailors on the naval ships Kitty Hawk, Hassayampa, Constellation, and Intrepid in 1972 and 1973. The seamen complained of relegation to the worst jobs, verbal abuse by officers, and denial of the right to assemble in groups. Zumwalt accused flag officers of dragging their feet in implementing the navy’s equal opportunity programs.Footnote 11

Racial conflict was also evident in the theater of war itself. In early autumn 1968, prisoners in the military stockade at Long Bình took over the overcrowded jail and burned down several buildings in the large facility where African Americans constituted more than 50 percent of the inmates. In 1969, at Camp Tien Sha in Đà Nẵng, one hundred Black troops, including marines, soldiers, and sailors, met to discuss discrimination in promotion, racial slurs, and disproportionate assignments to hazardous duty. Following the meeting they staged a peaceful march on headquarters, but no concessions were made. Other incidents at China Beach and Đà Nẵng proper and in Qui Nhơn indicated the persistence of racial division. Cross burning and the raising of Confederate flags remained flashpoints.Footnote 12

Communist forces hoped to benefit from these conflicts. James E. Jackson, a POW for eighteen months, told a reporter how his captors broadcast a speech by Stokely Carmichael that questioned the Black soldier’s role in Vietnam and cited American racism as a reason why he should not cooperate with the war effort. “This country will only be able to stop the war in Vietnam when the young men who are made to fight it begin to say, ‘Hell, no, we ain’t going,’” Carmichael told a University of California, Berkeley, audience on October 29, 1966.Footnote 13 Manuel Marin, a Mexican American Seabee, related an appeal to racial solidarity made by a Vietnamese who pointed out to him the similarity of their skin colors. A Native American in the army reported a similar experience. Yet the sense that many minority GIs had that they were fighting a war against people of color did not make most of them yield to these solidarity arguments even though it sharpened their criticism of US racism.Footnote 14

Soldiers stationed overseas were aware of the cresting civil rights and antiwar movements. They received news of the uprisings in cities such as Los Angeles, Chicago, and Detroit. Whatever their disdain for the antiwar movement per se, often perceived as the stomping grounds of discredited subversives, entitled youth who declined military service, and hippies, minority troops remained cognizant of activism at home and participated in fragmentary or symbolic forms of protest themselves. Most of those on assignments abroad had originally been stationed on troubled stateside bases. As National Guardsmen or army troops they had patrolled the streets of angry cities. News of domestic events reinforced the sense of many that they were embarked upon a contradictory mission.Footnote 15 The Pentagon chose several methods to address the unrest. One was to suppress the most violent manifestations, transferring or arresting alleged ringleaders. Another was to make minor concessions on such matters as hairstyle or military dress. A third way was to attempt to guide the development of citizen-soldiers and improve their performance. Military authorities thus embarked on a social science experiment.

Discourse in the 1960s was marked by an increasing rejection of segregation and a consensus in policymaking circles that discrimination and its effects, not biology, explained the United States’ persistent racial problems. Social science, however, was still prone to condemn the habits and attitudes of the poor and marginalized. Economist Daniel P. Moynihan, Assistant Secretary of Labor, rooted Black difficulties in mother-centered family structures, rather than in long-term unemployment, poor schooling, or racism. Moynihan’s March 1965 report for the Labor Department Office of Policy Planning and Research, “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” called for the remasculinization of African American men. The study came at a time when the family wage, a breadwinner salary generous enough to allow a wife to stay home, was declining for all Americans. Moynihan suggested military service as a possible instrument of Black male revitalization.Footnote 16 His work struck a nerve: the era’s plays and films about African Americans, such as Raisin in the Sun (1959) and Nothing But a Man (1964), foreshadowed this gendered concern. While Black popular culture subject matter ranged widely, a perceived need for male self-assertion remained an abiding theme during the period.

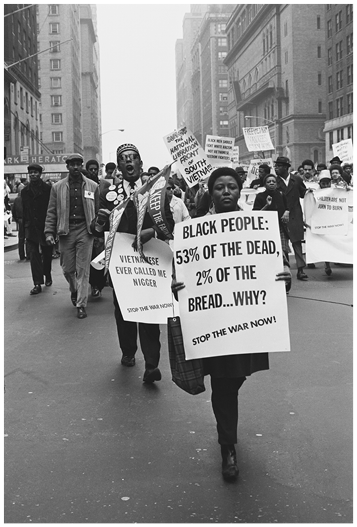

Figure 19.1 Black Americans march in New York City, calling for an end to the Vietnam War (1967).

In 1965 the Pentagon unveiled its own response to this issue. The goal of Project 100,000 was to add 40,000 formerly rejected men to the army in 1966 and another 100,000 in succeeding years. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara referred to these men as being “salvaged” for military service.Footnote 17 In lowering its standards, the Pentagon meant to instill in young Black men a proper conception of manhood as interpreted by Moynihan and other “culture of poverty” theorists. They hoped the initiative could also undercut the disaffection increasingly being expressed in American cities through violent insurrection.

Many of these soldiers, called New Standards men, lacked the basic skills to qualify for specialized training, and half were shipped to Vietnam as combat troops. Ultimately, some 300,000 joined the program, 50 percent of whom were Black, in a country where some 10.5 percent of the population was Black. Fewer than 8 percent received any advanced instruction. In 1971 the Pentagon terminated the project because of its cost and the deescalation of the war. New Standards men suffered disproportionately from post-traumatic stress syndrome and other injuries that impeded their employability and reintegration into civilian society. Whatever benefits the Black family was supposed to reap from the experiment proved elusive.Footnote 18

Black people were not the only Americans to experience the varied dissonances of the Vietnam era. Discussions of race have historically been premised on the assumption of a racial binary: white and Black people comprise most of the population in the dominant narrative, with such groups as Native Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans being marginal. That discourse was abetted by the frequent ambiguity and indeterminacy with which those groups were historically categorized in the United States. Some state law characterized Latinos and Asians as white during some eras and as nonwhite in others. The lack of clarity sometimes provided non-Black minorities a buffer from the lowest common denominator of status that African Americans occupied but could also further a sense of alienation.

While Native Americans constituted no more than 0.6 percent of the US population, they numbered some 1.4 percent of the fighting force in Vietnam. Estimating the total number of Native American veterans is difficult because of the inconsistency with which non-Black racial groups have been classified. Native Americans might be catalogued as Caucasian or Hispanic depending on circumstances such as surname or place of residence. Unlike African Americans, warfare for indigenous men was often linked to warrior traditions that antedate European contact. Native Americans were generally less critical of their treatment in the military. Because of their average low levels of education, however, they were commonly assigned to combat operations. Here stereotypes about Native Americans’ prowess as hunters led to their overuse as scouts and consequent high casualty rates. While protest activity among Native Americans was low compared to other groups, many saw the Vietnam War as one from which they would gain little benefit.Footnote 19

Like Native Americans, Mexican Americans did not originally take an oppositional stance regarding military service or their place in US society. Mexican American leaders had approached the race question by positioning their communities as ethnic rather than racial entities. This strategy was aided by the uneven application of racial categorization to Mexican Americans. Although officially deemed white, they were widely discriminated against in the Southwest United States, where most lived. The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), for years the major Mexican American civil rights organization, first followed a strictly assimilationist policy. LULAC had been less interested in fighting racial battles than in litigation designed to have Mexican Americans incorporated into mainstream white society. Some of the lawsuits it sponsored aimed at ending the exclusion of Mexican American children from white schools, not abolishing the principle of segregated schools. LULAC was also initially hostile to Mexican immigration in the belief that low-wage Mexican labor would undercut the gains that Mexican Americans had made. The American GI Forum, a Mexican American veterans’ organization, followed a similar policy.Footnote 20

Strong assimilationist goals within Mexican American society thus encouraged loyalty among Vietnam-era soldiers. They at first prided themselves on stoic acceptance of conscription, a traditional masculinism, bravery, and achievements in war. Vietnam began to weaken this orientation as antiwar activists rejected the implicit assumption that Chicanos had to prove their belonging through conspicuous acts of Americanism. Yet Mexican American soldiers were more often influenced by their own experiences. Modest education, nontechnical skills, and sometimes a language barrier caused many to be assigned to less appealing and more dangerous work. On the USS Kitty Hawk, for example, they labored with African Americans and Filipinos on the lower decks of the ship. In the army, they noted their overrepresentation in the infantry and their absence from safe jobs in the rear. These observations led to an increasingly critical examination of customary patriotism. Americanism, some realized, did not have to be limited to embracing an Anglo identity.Footnote 21

Some 48,000 Puerto Ricans served in Vietnam, and oral accounts affirm that they experienced the war in ways that other Latinos did, but important differences existed. Many soldiers coming directly from the Caribbean island did not speak English and, while there was no universal policy regarding language, the informal prohibition on speaking Spanish by some US officers remained a source of difficulty. Puerto Rico’s relationship to the United States was problematic for some. As a so-called Free Associated State with local powers, the island has no congressional representation and, while residents are US citizens, islanders cannot vote in presidential elections, although men during the Vietnam era were liable for conscription. During the height of the war in 1967, Puerto Ricans voted in a plebiscite to maintain the status quo, but the island’s position underlined the sense of being second-class citizens that many GIs felt. As a people of mixed-race ancestry, Puerto Ricans experienced racism in the military in ways that varied with their specific phenotypes. Some identified Puerto Rico’s liminal status with Vietnam, including one soldier who experienced a shock of recognition when ordered to set fire to the thatch roof of a village house that reminded him of the rural bohíos of his own tropical home.Footnote 22

Asian American soldiers fought in the context of a highly problematic history. Despite a lengthy Asian presence in the United States, courts had rendered contradictory decisions about Asians’ right to citizenship, based on racial criteria. Japanese American soldiers during the Vietnam era included some who had been born in internment camps during World War II. The military also recruited men from Pacific territories. Guamanians and other Pacific Islanders comprised part of the complement that today occupies an official census category. An East Asian phenotype could create situations where Asian Americans were mistaken for Vietnamese insurgents. The common use of such racial expletives as “gook” (an epithet with origins among US troops in the Philippine War and reprised during the US occupation of Haiti), “zipperhead,” “dink,” and “slope” required Asian American soldiers to identify themselves in ways that were not required of others. Military planners exploited the resemblance between these troops and the adversary in humiliating ways. Surprise raids conducted by soldiers sometimes disguised as peasants were used against suspected communist sympathizers. To slip past enemy vigilance, the troops chosen for these actions were often Asian Americans, Native Americans, or any man of color thought to look sufficiently Vietnamese. On bases soldiers were trained for what they might encounter “in country.” There, Asian American and Polynesian soldiers were dressed as residents of an enemy village in simulations meant to prepare troops for field conditions. Through these dramatizations and an often-expressed mistrust by fellow soldiers, the Asian American soldier experienced two sides of the war.Footnote 23

Crisis Mode

Military leadership, by inserting itself into civilian affairs, brought the war even closer to home. The army collected sociological data in efforts to predict domestic ghetto uprisings and spied on civilians to keep GIs away from influences deemed subversive. It maintained dossiers on soldiers who belonged to certain civilian groups, read “subversive” material, or contacted congressional representatives. Although the FBI filed weekly reports on African American and student organizations, the army claimed the Bureau’s data was inadequate for its purposes. Military intelligence could better enlist Black people and youth, and thus had greater ability to infiltrate organizations and monitor dissidents.

The civil rights movement had begun with claims on citizenship rights and a critique of the lapses of American democracy. The Vietnam War heightened participants’ sense of the contradictions between the country’s lofty ideals and its practices. Antiwar opinion among African Americans grew in 1966 in response to growing Black casualties, reports of bias in the military, and the inequitable nature of the draft in many communities. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) condemned all-white draft boards in Southern states, alleging that they targeted civil rights workers to derail the movement. Segregationist authorities used antidraft activism to discredit Black insurgency, prosecuting activists as subversives, and using conscription to banish troublesome young men. Heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali garnered wide press coverage when he challenged his own draft status. During a 1967 appearance in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, he gave his reasons: “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on Brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” Even without overt bias and manipulation, the Selective Service System was discriminatory, giving cover through student deferments to white middle-class youth while keeping militant Black college students in its sights.Footnote 24

Draft resistance activities on historically Black college campuses led students to oppose the war and heightened their opposition to the nation’s continued recalcitrance on the civil rights front. Southern authorities responded to Black antiwar activity with repression. In 1967 police shot into a dormitory at Texas Southern University. In 1968 officers killed three students and wounded thirty at South Carolina State University. Later that same year, when Tuskegee University students took over the campus and refused compulsory participation in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program, the Alabama governor called out the National Guard and the state police.Footnote 25

Martin Luther King, Jr., had privately expressed misgivings about Vietnam as early as 1965 but had refrained from public criticism, despite urging from those civil rights and peace activists who had opposed the war early. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and certain Black Democratic politicians loyal to President Johnson had urged King to remain quiet. In late 1966 he finally spoke out when he accepted an invitation to deliver remarks at an April 4, 1967, meeting at the Riverside Church in New York City. His address, titled “A Time to Break Silence,” forthrightly posited a connection between racism at home, predatory capitalism, and brutal policies abroad targeting the poor and people of color. King referred to his early optimism that the United States was changing for the better. “There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings.” Federal antipoverty initiatives promised reform. “Then came the buildup in Vietnam and I watched the program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war, and I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube.” It was at this point that King “was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.”Footnote 26

The NAACP continued to back President Johnson despite protest from rank-and-file members. A resolution passed at its 1967 conference in Boston implied that condemning the war was off the table so long as the War on Poverty remained intact. The NAACP did not acknowledge that the conflict was draining resources needed to aid the poor. Other civil rights groups were less hesitant. SNCC and the Black Panther Party, for example, linked compromises and failures on civil rights to the war in Southeast Asia and called for a more assertive approach to American politics.Footnote 27

Black Power activism differed from civil rights insurgency in claiming a broader field of both rights and oppositions. African American freedom, according to the civil rights movement’s discourse of citizenship, would be realized within the framework of the democratic nation-state. Black Power proponents, however, saw American nationalism as part of the problem exacerbating global conflicts. SNCC, for example, first emerged as an organization that strongly affirmed a liberal vision of the United States as inclusive and democratic. After years of political work in a violent South, bereft of meaningful support from the federal government, SNCC activists increasingly defined the Black freedom struggle as worldwide and sought international alliances of the oppressed. The granting to SNCC of status as a quasi-liberation organization by radical governments and national liberation movements abroad encouraged its practice as a challenger of US imperialism.

While SNCC remained a small group that would diminish considerably before finally extinguishing itself by the mid-1970s, its significance for race relations during the Vietnam era is that it helped to define a generational stance among the cohort of Black Americans that would fight the war and those who would fight against it. Along with the Black Panther Party and more local organizations, it disagreed that attaining legislative victories was sufficient to heal the United States’ racial divisions, and called for discussion of the best plans for Black liberation going forward. SNCC buttressed this with an internationalism that denounced colonial and neocolonial regimes and called on African American solidarity with those striving for self-determination abroad.Footnote 28

Most African Americans, however, were more in tune with King’s expanded vision of the community of the poor. Even here activists came up sharply against the reality of the state’s repressive potential. Protestors placed by the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, DC, in 1968 vowed to remain there until the federal government took decisive action on poverty. In the spring they began constructing a shantytown on the National Mall that they named Resurrection City. Unnerved by 2,600 residents at Resurrection City’s peak, and especially by the presence of large numbers of young Black men, the Justice Department, local police, and the US Army made contingency plans for a violent insurrection in the city. In late June the authorities stormed the encampment and razed its flimsy tents. As noted above, the army was not only an overwhelming presence in Southeast Asia, but also a major player in the domestic racial drama of the period, a role that intensified in the aftermath of King’s assassination in April 1968.Footnote 29

The ubiquitous fluidity of the military presence meant that race as well as the military were both inside and outside every zone of conflict. If the armed forces went to war in Vietnam, they also went to war in the United States in the form of riot suppression, surveillance, and infiltration. If there were civilian antiwar activists, there were also military deserters, saboteurs, and quiet dissidents. The military was thus embedded in all aspects of race relations during the period and in how people of color responded to the Vietnam War.

Vietnam also prompted Martin Luther King, Jr., and more radical activists to challenge the assumption that civil rights, and more broadly human rights, should be confined to specialist organizations, and the view that people of color were not entitled to stances on foreign policy. Critics assailed the forward edge of the civil rights movement for embracing a class-conscious, multiracial position on domestic issues and linking these to the war.

Linking the Movements

While African Americans had always been racialized subjects in the United States, not all nonwhite groups had such an unequivocal experience. Mexican Americans had adhered to a model of hyphenated ethnicity and Puerto Ricans to nationality. The war encouraged many to see themselves as racially defined in a conflict whose costs were disproportionately borne by people of color. The stage was thus set for collective action by multiracial antiwar coalitions such as the Third World Women’s Alliance and the Third World Liberation Front.

The questioning of customary authority in the society at large and Native Americans’ wartime experience helped alter the quiescence of native communities and revived an appreciation of traditional life. Native activism was thus the product of several cumulative factors. The rise of the environmental movement, coterminous with the war and the civil rights movement, led many Native Americans to reassess their relationship, both historical and contemporary, with the federal government and reclaim aspects of their historic ties to the land. The growth of the indigenous population and the increased number who lived outside reservations and rural areas made space to articulate more than one kind of politics.

While Native Americans were frequently regarded as inert symbols of the purity of nature, their rights to the environment were routinely violated. In the mid-1960s indigenous organizations and civil rights groups challenged Washington State’s violation of Native American treaty rights by holding “fish-ins,” netting and trapping fish according to traditional methods. In 1969 indigenous activists began a nearly two-year occupation of Alcatraz Island, claiming this disused federal property for natives. The increasing number of Native Americans living outside reservations and willing to operate politically beyond the constraints of tribal politics set up the conditions for later challenges to the status quo such as the 1972 occupation of the headquarters of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the confrontation with federal agents the next year in Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Some of this activism involved both racialization and ethnicization of Native Americans who in the past had been submerged in specific tribal identities, but not all Native Americans accepted the new approaches.Footnote 30

The reshaping of identity also played a role in antiwar resistance mounted by Mexican Americans. Adoption of the term Chicano signified a transition in thinking as the word had negatively connoted a lower-class status. In embracing it, Chicanos and Chicanas abandoned what might be called a politics of respectability: humble, loyal service to a state that questioned their citizenship and often denied them equal rights. As the African American freedom struggle began to realize concrete legislative gains by the mid-1960s accompanied by redistributionist federal policies, some Chicanos felt that quiescence and compliance – as well as cultivation of white personas – had not advanced their interests or provided opportunity. Renewed concern for the rights of farm workers emerged from a reevaluation of what it meant to be Mexican American. Changes in consciousness accompanied the emergence of a labor movement around the United Farm Workers Union. In California, Texas, Arizona, Colorado, and Illinois, Chicano demonstrators protested police brutality, poor education, and the discriminatory draft system. In New Mexico, home for centuries to people of Spanish and Mexican descent, conflict with state authorities erupted over land grants bestowed long ago. The clash echoed Native Americans’ awakened consciousness regarding land rights. Some emerging organizations emulated the Black Panther paramilitary style, including the Chicano Brown Berets and the Puerto Rican Young Lords.Footnote 31

Beginning in 1969 Chicano activists organized a series of demonstrations in East Los Angeles. Under the rubric of the Chicano Moratorium, they brought together thousands of people to protest the Vietnam War and discrimination. The capstone demonstration took place on August 29, 1970, and drew 25,000 people in a protest unprecedented for its size and the Mexican American participation rate. For reasons that remain unclear, the Los Angeles Police Department fired on the assemblage and dropped tear gas, killing four people, including a Los Angeles Times reporter of Mexican descent, perpetuating the already existing tension between Spanish-speaking Angelinos and the police.Footnote 32

Antiwar opposition among Asian Americans helped to invent the category Asian American as one that crossed lines of national origin and aspired to a united front of dissent. Before passage of the Immigration Reform Act of 1965 and the arrival of Vietnamese, Hmong, and other Southeast Asian immigrants at the end of the Vietnam War, most Asian Americans were of Japanese, Chinese, or Filipino descent. Although their links to their original homelands were often attenuated, a popular perception was that they were foreigners. The nature of US relations with Japan and China over time influenced how immigrants were perceived. The long period of “Oriental” exclusion, anti-Chinese riots in the nineteenth century, arbitrary and conflicting efforts by courts at racial classification, and the World War II–era incarceration of Japanese Americans reaffirmed an outsider status and reinforced the cautiousness with which many Asian Americans had approached political participation.

At first glance, circumstances suggested that activism would thus be minimal within these communities. In Chinatowns, the strong anticommunist influence of Guomindang adherents had neutralized leftwing radicalism and quelled demonstrative opposition to US foreign policy. Yet the Vietnam War by the early 1970s had engulfed the entire Southeast Asian peninsula. Looking backward, Asian American dissidents could see the Afro-Asian Conference of 1955, the Bandung Conference, as a precursor for challenges to Western domination and as a call for Asian solidarity. Additionally, the lack of a common national origin as a source for a collective Asian American identity suggested another possibility: Asian Americans as a people of color, i.e., a racial group. As such, antiwar organizations like I Wor Kuen merged with the Chicano(a) August 29 Movement and made common cause with the Congress of African People. Some scholars suggest that Asian American radicals rejected their model minority status and embraced a racial identification based on their interpretation of Black militancy. Dissident Chinese Americans in the San Francisco Bay area sought direct counsel from the Black Panther Party in establishing an organization called the Red Guards. This late 1960s group avidly read the works of Mao Zedong but knew little of the character and excesses of the Cultural Revolution occurring in China. While students had some insulation from the draft, it was not secure, and they recognized that others in their age cohort were being sent to war.Footnote 33

Racial self-definitions owed something to the meanings assigned to people in US popular culture. Only one major film of note dealing with the Vietnam War, The Green Berets (1968), appeared during the war itself. That film rehearsed familiar tropes about white American bravery in the face of foreign racial others. The film industry, pulp fiction, and cartoons had long provided a host of stereotypes about East Asians, many dating from the nineteenth century. Hollywood’s antidote to the lethal villain Fu Manchu was the partially Americanized detective Charlie Chan. During the war with Japan in the 1940s Chan came to represent the “good” Asian, in marked contrast to the flamboyant Orientalism embodied by the evil Dr. Fu Manchu and the cruel Japanese militarist. The Green Berets characterized the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces as the “good Asians” in this enduring convention.

Asian women could also be malevolent, calculating “dragon ladies” in league with Fu-like criminals. They were just as often described as eroticized, exotic, and passive victims of sex trafficking or other ills, and generally deprived of character development in fictional treatments. While Charlie Chan and his son (who called his father “Pop” in an informal manner comfortable to Americans) were portrayed as acculturated, no parallel role existed for Asian American women. Women who broadcast wartime propaganda for US enemies – Tokyo Rose, Peiping Polly, Hanoi Hannah – could easily have been non-Asian because they were simple voices but nevertheless helped fortify prevailing stereotypes which found few alternatives in popular media until after the Vietnam War ended.Footnote 34

Children were generally spared from these representations. Large-scale adoptions of Korean children by US citizens began shortly after the Korean conflict ended in 1953. Orphans included the biracial offspring of white and Black American troops. The adoptions marked the beginning of a change in American racial attitudes, although approved adoptions initially followed racial lines. Korean children with white American ancestry were to go to white families, and those with African physical traits to Black parents. Unlike the media portrayal of Asian adults, the Korean orphans were considered innocent and redeemable candidates for assimilation into American families. Little public attention was given to the specific circumstances in which each had become parentless.

In Vietnam, American soldiers sired mixed-race children, as had French troops before them. As in the colonial period, children’s fate often hinged on paternal recognition. This recognition was not always an individual decision. During World War II and the Korean War, African American soldiers often had difficulty receiving permission to marry foreign nationals and repatriate their offspring. Some reported the top brass’s continuing resistance to Black veterans’ constituting such families during the Vietnam era. The federal government proved hesitant to allow paternally unrecognized children to immigrate. Abandoned children were disproportionately Black and were thought less likely to assimilate positively into Vietnamese society. Senator Mark Hatfield and others authored a bill that assumed moral responsibility for orphans left behind by US servicemen and proposed the creation of an agency to attend to their welfare. The bill was postponed and the plight of abandoned children in Vietnam left to private organizations to address.

Concerned officials then turned for advice to experienced French private agencies that still operated in the country and expatriated Vietnamese children. In 1975, as the war was collapsing and American defeat was imminent, private US groups with federal support began flying orphans to the United States. One of the planes carrying children in so-called Operation Babylift crashed, killing most of the young passengers. In the ensuing investigation, it was revealed that many evacuees had not really been orphans. American aid organizations had followed French precedent in removing children without maternal consent even though it was well known that mothers sometimes placed children in orphanages as a temporary measure while they sought work. US charities had also ignored the desires of both South and North Vietnamese governments, which opposed foreign adoption of Vietnamese children.Footnote 35

The Babylift fiasco reflected the racial dynamics of the Vietnam era. Cavalier attitudes toward mothers and children in crisis by both Vietnamese and American authorities, the racial assessments made, the evasion of responsibility, and ultimately the hasty evacuation helped write the narrative of the war. While Americans have historically distanced themselves from the colonial legacy of domination over people of color, Vietnam reaffirmed hierarchical relationships based on force. At home, African Americans and other racial–ethnic minorities continued to challenge a white supremacy that had retreated from claims to legitimacy but remained a persistent structural element of US society.