What commerce […] for the people that are the sole proprietors of the most powerful remedy that medicine possesses to restore the health of mankind in the four corners of the Earth.

By the late 1700s and early 1800s, cinchona bark was, to many, ‘the most important, and the most usual remedy that medicine possessed’.Footnote 1 Though of limited repertoire – cinchona trees prospered only on the precipitous eastern slopes of the Andes at the time, in the Spanish American Viceroyalties of Peru and New Granada – and comparatively recent acceptance into Old World materia medica, the bark had, by the turn of the eighteenth century, woven itself into the texture of everyday medical practice in a wide range of societies within, or tied to, the Atlantic World. It was everywhere attributed ‘wonderful’,Footnote 2 ‘singular’,Footnote 3 even ‘divine’Footnote 4 medicinal virtues, the knowledge of which, so it was said, had come to mankind from its simplest, and humblest, specimens, ‘wild Indians’Footnote 5 close to nature and privy to its most coveted secrets. Bittersweet ‘febrifugal lemonades’ and bottled wines of the bark sat on the shelves of Lima apothecaries, the counters of Cantonese market stands and in the medicine chests of Luanda hospital orderlies. They were routinely concocted, and administered at the bedside, by Moroccan court physicians, French housewives and slave healers alike and they accompanied, tucked into their pouches, Dutch sailors to febrile environs, Peruvian soldiers to the battlefield and North American settlers westward. Scottish physicians, creole botanists and French writers alike were unanimous not only in according the bark ‘singularity’,Footnote 6 and ‘the first place among the most effective remedies’ (die erste Stelle unter den würksamsten Arzneimitteln),Footnote 7 but also in holding it to be ‘more generally useful to mankind than any in the materia medica’.Footnote 8 It was commonly agreed upon that there was ‘no febrifuge of such well-known virtue in all of medicine’ (por que no se halla en la Medicina febrífugo de virtud tan conocida),Footnote 9 and that not a single remedy ‘more estimable and precious [than the bark] had been discovered unto this day’.Footnote 10

For decades now, historians of science, medicine and technology have insisted on the epistemological lesson that science and knowledge are the result of specific circumstances and close, local settings, situated and bound ‘ineluctably to the conditions of their production’ – historically contingent, idiosyncratic ‘form[s] of practice’, rooted in a particular time and place.Footnote 11 The field is at present said to be in the midst of a fundamental turn toward global approaches that straddle traditional spatial boundaries but, as some of its most prominent advocates have cautioned, practitioners have hardly begun to understand the consequences of that shift for the field’s most basic values and principles, especially its emphasis on locality.Footnote 12 This book is an attempt at writing a history of how medical knowledge – in the shape of matter, words and practices – was shared between and across a wide range of geographically disperse and socially diverse societies within the Atlantic World and its Asian entrepôts between 1751 and 1820. Centred on the Peruvian bark, or cinchona, it exposes and examines how that medicine and the imaginaries, therapeutic practices and medical understandings attendant to its consumption, were ‘part of the taken-for-granted understanding’Footnote 13 of people in many different social and cultural contexts: at Peruvian academies and in Scottish households, on Louisiana plantations and in Moroccan court pharmacies alike. Much of the book is concerned with the conditions, contingency and idiosyncrasy of the prevalence and movement of bark knowledge – through contingent ‘act[s] of communication’,Footnote 14 ‘brokerage’Footnote 15 and sociality,Footnote 16 ‘between […] settings’ tied together by Atlantic trade, proselytizing, and imperialismFootnote 17 – as well as with the variability of the knowledge in motion. Indeed, the book suggests that cinchona’s wide spread owed less to its utter immutability and consistency than, as historians have argued for other tools and substances, to a measure of malleability, and multivalence: its ability to ‘subtly adapt’, be refashioned, or tinkered with.Footnote 18 Scholarship on modern and early modern globalization, with its liquid language of elusive flows and unconstrained circulation, still tends to evoke an idea of movement as erosive and antithetical to place, and of ‘the very idea of locality […] as a form of opposition or resistance to the […] global’, a gesture towards the discrete, and authentic.Footnote 19 It was in large measure the bark’s ability to tie itself to locales, however, to settle and become situated,Footnote 20 again and again, that accounted for its prevalence and mobility. Science and knowledge are not bound to one time and place, this book holds. They may be unmoored and moved – become well known and generally useful elsewhere – but they will invariably do so in ways that are just as contingent, situated and local as those traditionally associated with their production.

The Outlines of Cinchona

It may appear redundant for the historical account of a plant component to further define the outlines of its object of study. The seeming definitional sharpness of cinchona is deceptive, however.Footnote 21 Because the bark was, by the late 1700s and early 1800s, spoken of, sought after and studied in countless tongues across the Atlantic World and beyond, there were considerable shifts in its epistemic, chemical and medical contours, its nomenclature and, not least, its therapeutic indications. This is not to say that cinchona was not a distinct, identifiable object by the late 1700s and early 1800s.Footnote 22 Indeed, though its passage into the wider Galenic medical repertoire during the late 1600s had been attended by controversy over its nature, virtues and properties,Footnote 23 by the late 1700s and early 1800s, medical practitioners, both lay and professional, across the Atlantic World generally agreed on the bark’s utility as a remedy and its coherence as a category.Footnote 24 Rather, the very latitude and cosmopolitanism of the bark’s pathways entailed acts of adaptation, customizing and calibration, and, with them, a measure of variability and volatility that compels us to handle both the subject and the term, cinchona, advisedly, and with a measure of care.Footnote 25 As much recent scholarship reminds us, objects exist both in space and in time. They have a diachronic quality; are possessed of lives and biographies;Footnote 26 and accrete new meanings, names and properties, as they are identified, translated or ‘adjust […] to context’ in the process.Footnote 27 They ought thus to be understood as malleable to a point: as multiple yet coherent, as liminal yet recognizable.Footnote 28

As with other introduced exotic commodities – coffee, rhubarb or pineappleFootnote 29 – by the late 1700s and early 1800s appellations for the bark across languages varied, if seldom beyond recognition. Cinchona was the standard botanical name for the bark after Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) first defined the genus in the second, 1742 edition of his Genera Plantarum, naming it after the Countess of Chinchón, Francisca Fernández de Ribera, for her legendary and, by all accounts, imaginary role in drawing attention to the bark’s virtues sometime between 1632 and 1638.Footnote 30 The bark also continued to be referred to by the older name of quinquina – from Quina-Quina, a Quechua word that actually referred to the balsam tree, and had been misapplied to cinchona by the Genoese physician Sebastianus Badus (fl. 1643–1676) in his 1663 Anastasis Corticis Peruviae.Footnote 31 Quinquina persisted in various guises, coterminous with and alongside cinchona, particularly in FrenchFootnote 32 and Italian,Footnote 33 into the early nineteenth century, while SpanishFootnote 34 and PortugueseFootnote 35 sources employed the shorter quina. German and Dutch texts, presumably onomatopoetically with the Iberian term, likewise referred in common parlance to ChinaFootnote 36 – or ChinarindeFootnote 37 – and kina,Footnote 38 respectively, and to cinchona in jargon. Some European languages possessed other alternate terms for cinchona, revolving around its provenance, medicinal properties or materiality. In English, for instance, its popularity allowed it to be known simply as the ‘bark’ or, owing to its supposed provenance, as the ‘Peruvian bark’. On account of its close association with the Jesuit order, particularly in earlier sources, it was also referred to as the ‘Jesuit’s bark’ or, since it was often available in the pulverized form, the ‘Jesuit’s powder’.Footnote 39 Spanish sources, too, often spoke rather than of quina of cascarilla, a diminutive of the Spanish word for ‘tree bark’ (cascara), while German sources occasionally referred to it as Fieberrinde, that is, ‘fever bark’.Footnote 40 Nomenclature maintained a measure of coherence and kinship even beyond these earlier consumer societies by virtue of linguistic relationships – translation equivalence, or onomatopoeia – references to geographical provenance, or therapeutic indications. Slavic, Turkic or Asian-language renderings in particular appear to have had onomatopoetic qualities. Eighteenth-century Chinese sources referred to ‘金鸡勒’ (‘chin-chi-lei’ in Wade-Giles, ‘jin ji lei’ in pīnyīn),Footnote 41 for instance, Russian sources to ‘хина’ (khina), or ‘перуанская хина’ (peruanskaya khina),Footnote 42 while in the Ottoman Empire the bark was referred to as ‘kına’ (kina), or ‘kûşûru’l-Peruviyane’, a literal translation of ‘Peruvian bark’.Footnote 43 Equations are, to be sure, fraught with difficulty, and these various terms were idiosyncratic and part of widely divergent epistemic systems. They were also, however, cognate appellations, fragments of discourse that reveal networks of production,Footnote 44 threaded together by men and women from various world regions who had evidently long engaged with and relied upon one another – not only in apprehending that substance’s ‘admirable effects’Footnote 45 but also in crafting a name for it.

Significant, and growing, world market demand for the bark in the late 1700s and early 1800s – from buyers in Portuguese Luanda, at the Ottoman Porte and in the Archduchy of Austria alike – rendered cinchona’s botanical classification and demarcation both imperative and difficult. As with other plant-based medicinal substances of the period,Footnote 46 there was considerable controversy not only over the boundary of cinchona via-à-vis other plants but also over the varieties cinchona was to encompass – the kinds and number of species that were to be contained in the genus Cinchona, to resort to the period’s botanical lexis.Footnote 47 It was in particular the repeated removal to novel bark-growing regions in the Spanish American Viceroyalties of New Granada and Peru – on account of the bark’s worldwide appeal, and resultant overexploitation – and with it, the encounter with divergent varieties of cinchona, that distressed consumers, medical practitioners and naturalists alike.Footnote 48 The Spanish, British and French commercial quest for substitutes also yielded several South Asian, Filipino, and Caribbean cinchonas – from St Lucia, Saint Domingue, Guadeloupe and Martinique – that were subject to clinical trials and chemical analyses, but eventually, for the most part, discarded.Footnote 49 In 1805, as the result of a two-decades-long quest, two tree species supposed to be cinchona varieties – Cinchona macrocarpa and Cinchona pubescens – were discovered on Portuguese territory in Rio de Janeiro.Footnote 50 Other than to the general limitations of Linnaean taxonomy and the difficulty of examining live plant specimens,Footnote 51 it was owing to the variation in propertiesFootnote 52 (bark colour, taste and texture), presented by the proliferation of newly found cinchonas by the beginning of the nineteenth century, that caused contemporaries to continue to differ – in some measure, increasingly so – on how to delineate and group that plant. Opinions on the sheer quantity of extant cinchona species varied from author to author, from two to twenty-two.Footnote 53 While the inner and outer botanical outlines of cinchona remained elusive, fragile and tenuous in the eyes of botanists from Uppsala to Santa Fé de Bogotá into the early nineteenth century, however, constant debate about its varieties also reified the idea of cinchona as a single object. As historians have argued for other plants, the very discussion of its instantiations – in continuously referencing the category they instantiate – also contributed to stabilizing and objectifying the bark as a recognizable thing.Footnote 54

London physicians,Footnote 55 creole bark merchants in the Viceroyalty of New Granada,Footnote 56 and Chinese medical authorsFootnote 57 alike commonly circumscribed the bark’s identity in the late 1700s and early 1800s, like botanists, by virtue of its geographical provenance as well as its material properties – texture, taste, consistency and colour. Genuine cinchona was supposed to have the same shape as cinnamon; a rough, splintery and mealy texture; and to be of either white, pale-yellow, reddish or orange colour, according to species (Figure 0.1).Footnote 58 When chewed, it was to be of a bitter, aromatic and astringent taste.Footnote 59 In conjunction with the rise of clinical pharmacology, experimenters also began to define the bark chemically, through experiments and the testing of properties – its acidity, solubility in various solvents or reaction with other substances, particularly bodily fluids.Footnote 60 At a time when simple clinical observations, experiences and statistics to evaluate treatments were gradually being introduced, doctors, botanists and surgeons in Madrid, Cartagena de Indias, London, Saint Domingue, New York, Rio de Janeiro or Lyon also increasingly conducted clinical trials – ‘exact, and repeated observations’, ‘by means of a general, extensive administration’ of the bark – among the populations of hospitals, slave plantations, or the military to put different or newly discovered varieties of cinchona on trial and gain ‘a proper understanding of their virtues’ (o devido conceito das virtudes).Footnote 61 None of these criteria of demarcation was absolute or definite, however. Plant materials belonged in the world of commodities and trade, and human indiscretion, as well as natural variation in their materiality – or ‘perceptible qualities’, to use the period’s lexis – rendered them as resistant to epistemic and medical stabilization as they did to botanical classification. Other than the removal to novel bark-growing regions and the commercial quest for substitutes, by the late eighteenth century, instances of wilful fraud – the addition of poor-quality cinchona or other, non-medicinal barks – by Caribbean pirates,Footnote 62 Habsburg customs officialsFootnote 63 and London apothecariesFootnote 64 alike, as well as of deterioration in transport, further induced the authors of health advice manuals and popular recipe collections to advise caution in selecting cinchona bark.Footnote 65 Cinchona was ‘now for the most part adulterated’, as the author of an Italian manuscript recipe collection phrased it.Footnote 66 Readers were well advised to take care that the bark they purchased not be ‘spoiled by moisture,’Footnote 67 that its taste be neither ‘nauseous, or […] mucilaginous’, nor its surface too tough or too ‘spongy, […] woody, or powdery’Footnote 68 – that the bark be, in short, neither false nor deteriorated. Cinchona, as it was conveyed across landmasses and bodies of water, and taken into hospitals, laboratories and apothecary shops the Atlantic World over, thus exhibited a material tendency to decay and a natural and circumstantial bent for variation that hinged on the very breadth of its acceptance and the steadfastness of its appeal. Discourses and practices attendant to the bark’s propensity to decay, and its bent for variation, certainly encumbered and delayed its epistemic and medical delineation, and stabilization in ways that render any account of it a ‘history of likenesses rather than […] of an object’,Footnote 69 of a historical category rather than of a specific kind of matter. They also indicate, however, the extent to which cinchona had, by the decades around 1800, become an object that trained observation could discern, and the integrity of which it was considered necessary, and ultimately possible, to maintain, police and regulate.Footnote 70

Figure 0.1 Cinchona rosea Flor. Peruviana. Sample collected under the aegis of the Botanical Expedition to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1778–1816), under the command of Hipólito Ruiz López and José Antonio Pavón. MA-780943. Herbario del Real Jardín Botánico, CSIC.

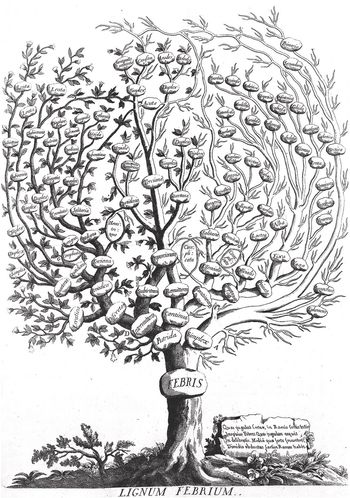

Cinchona was extensive not only in its geographic reach by the late 1700s and early 1800s – enjoying popularity in societies the Atlantic World over – but also in its therapeutic indications. As historians of pharmacology have shown, while in the seventeenth century physicians had still taken cinchona to be a ‘specific’ – a remedy that targeted and extinguished one particular kind of disease, ‘intermittent fevers’Footnote 71 – by the eighteenth, medical practitioners from Britain to Muscovy, and from the sultanate of Morocco to the Viceroyalty of New Spain, would have agreed that the bark was effective for various types of fevers – intermittent, but also remittent,Footnote 72 bilious,Footnote 73 nervousFootnote 74 or yellowFootnote 75 (Figure 0.2). Some practitioners suggested that cinchona could also be useful in other diseases: in gangrene,Footnote 76 haemorrhages,Footnote 77 dysentery,Footnote 78 epilepsy,Footnote 79 smallpox,Footnote 80 rheumatism,Footnote 81 consumption,Footnote 82 scurvy,Footnote 83 jaundice,Footnote 84 the goutFootnote 85 or in obstructions of the menstrual flux, that is, to induce the menses.Footnote 86 Novel indications were brought on both inadvertently, by ‘chance observations’ and therapeutic experience,Footnote 87 and on account of alterations in interpretations of the bark’s mode of operation – it was increasingly thought to act through general, not specific, tonic, or stimulant, antiseptic, astringent or corroborant propertiesFootnote 88 – as well as in the understanding of the causes of fevers. In the late eighteenth century, fevers came to be seen as the effect of conditions such as debility of the fibres, recurrent ‘atony’ or putridity, the same disorders that were thought to produce ailments like gangrene, smallpox or dysentery.Footnote 89 This is not to say that cinchona ceased to be the remedy of choice in intermittent fevers. As a matter of fact, while it was ‘pretty generally agreed’ among medical practitioners, both lay and professional, from the West Indies to the Ottoman Porte, that cinchona was the remedy they could ‘most certainly rely on for the cure of intermittent fevers’,Footnote 90 its propriety and effects in other disorders, particularly those that were not fevers, were considered uncertain, ‘various and often opposite in different patients, and in different states of the same patients’.Footnote 91 It is to say, however, that the bark’s curative indications expanded considerably, rendering it, by all accounts, a broad-spectrum febrifuge by the turn of the eighteenth century, and, at least temporarilyFootnote 92 and to some practitioners, also a panacea and universal remedy.

Figure 0.2 The ‘Fever Tree (Lignum Febrium)’ by Francisco Torti, which supplemented the author’s taxonomy of fevers. Branches covered with bark, occupying the left part of the picture, represent fevers curable by Peruvian bark, whereas denuded, leafless branches represent continued fevers not curable by cinchona. At the centre are trunks and branches partly covered by bark, corresponding to the ‘proportionate fever’, in which susceptibility varied. Branches that anastomose represent fevers that change from one category to another, 1712. Francisco Torti Therapeutice Specialis Ad Febres Periodicas Perniciosas.

We tend to think of substances as durable kinds of matter with uniform, definite properties: as foundational, fundamental entities, and as ontologically basicFootnote 93 – everything that cinchona, in its evident variability and ambiguity, its shifting epistemic, chemical and medical contours, was not. The Peruvian bark was not so much a specific kind of matter by the late 1700s and early 1800s. It was, rather, a specific historical category that encompassed various kinds of matter: a number of dried, bitter-tasting shreds of tree bark marketed, dispensed and classified under the name of cinchona – or, indeed, one of that name’s alternate and foreign equivalents – inclusive and aware of their shifting therapeutic attributes and of their material tendencies toward decay or variation over time and space.

An Appraisal of the Historiography

The singular medicinal virtues ascribed to cinchona have, over the centuries, attracted a considerable number of historians to the subject. The historiography has suffered, however, from a tendency toward presentism on the one hand – a subservience to quinine, one of cinchona’s active compounds, and malaria – and a close association with particular empires and states on the other, the British and Spanish especially. Particularly with an Anglo-American reading public, cinchona is still closely associated with the British Empire and the salvation of the lives and minds of Englishmen in the malaria-stricken Raj of the late nineteenth century.Footnote 94 A Singular Remedy breaks with these two historiographical traditions, in that it centres on the knowledge movement that limitation to particular empires has largely obliterated and on the contingency, variability and idiosyncrasy of bark knowledge that presentism has so often obscured. At the very heart of A Singular Remedy is the richness and latitude of the life of a substance that habitually crossed imperial and medical boundaries: the diversity of therapeutic practices and routines of medication pertaining to cinchona, the variety of ailments and conditions in which it was employed, and the wide range of creole, French, Cantonese, Portuguese or Levantine experts, sufferers and vendors given to its consumption, sale or advocacy.

The book breaks, first, from an important sector of the historiography that has reduced the bark to its part as the source of, and precursor to, quinine, and proceeded on the assumption that it would have been, like that active compound it contained, effective against malaria. Indeed, cinchona has long occupied a prominent place in presentist histories of medicine chronicling ‘the ideas and events which brought medicine ever closer to the secrets of disease and health’.Footnote 95 Along those same lines, a popular, laudatory, genre of historiography has celebrated the bark as ‘the remedy that has spared, or at least ameliorated, the greatest number of lives in human history’.Footnote 96 That historiography has also celebrated its discoverers, advocates and pioneers: the friars of the Jesuit order who first appreciated its true value, the visionary physicians and apothecaries – Robert Talbor (1642–1681) and Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689) – who overcame widespread resistance to it, and French and Prussian naturalists – Charles-Marie de La Condamine (1701–1774), Joseph de Jussieu (1704–1779) and Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) – who ‘braved swamps, […] dangerous animals, and wild river rapids’ to bring back specimens, and observations, of cinchona plants in their natural habitat.Footnote 97 Much of the academic historiography, too, though far from embracing the same triumphalist rhetoric, has proceeded on the assumption that the bark was a natural remedy against malaria.Footnote 98 Even where historians have doubted the bark’s efficacy, they have reduced it largely to its administration in ailments retrospectively diagnosed as malaria. Many of the earliest historical studies of the bark,Footnote 99 as well as some of the most conspicuous recent publications that make reference to it by environmental and global historians of disease,Footnote 100 have come out of the historiography pertaining to malaria. It is, to be sure, perfectly plausible to assume that the various barks contemporaries consumed under the designation of cinchona effectively contained, like their modern-day equivalents and in varying proportions according to species, natural alkaloids (among them, quinine and quinidine, cinchonine and cinchonidine), which, in an isolated and crystallized state, are at present thought to interfere with the growth and reproduction of malarial parasites.Footnote 101 It is also reasonable to assume a relationship between intermittent fevers, the ailments most commonly treated with the bark, and forms of malaria, or rather, the disease consequences of the protozoan parasite species Plasmodium vivax, which occurs with 48-hour periodicity, Plasmodium malariae, which causes paroxysms every 72 hours, and Plasmodium falciparum, respectively.Footnote 102 For intermittent fevers, as distinguished from continual or remitting fevers, had ‘intervals or remissions of the symptoms’.Footnote 103 There were tertian fevers, so-called because febrile accessions recurred on the third day, and quartan fevers, so-called because they came with attacks on the first and fourth days, as well as several less clearly synchronous, malignant forms of intermittent fevers.Footnote 104 It is not pertinent, however, to reduce the bark to its administration in intermittent fevers, when it was by all accounts a broad-spectrum febrifuge and panacea by the turn of the eighteenth century. Nor is it commensurate to assume that the bark cured men and women in the past, nor that it even afforded them relief. Not only is there in fact only limited clinical evidence to support ideas about the efficacy of whole cinchona bark extracts, even in the treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum and vivax malaria, especially since the last extensive clinical trials with whole cinchona bark extracts were conducted in the 1930s.Footnote 105 There is also great uncertainty about the concentration of alkaloids in the barks commercially available in the eighteenth century. Even if we were to assume that barks sold under the name of cinchona uniformly contained active compounds and that these were effective in the treatment of malaria, there would still be no way of knowing whether the intermittent fevers for which the bark was ordered were identical with modern-day malaria – retrospective diagnosis based on observation and description of symptoms naturally leads to a wide margin of errorFootnote 106 – whether contemporaries administered curative doses of the bark, and whether the by all accounts common admixture of purgatives would not have mitigated sufferers’ response.Footnote 107 Also, the historical record is too incomplete to allow for any kind of quantitative assessment. Comprehensive, systematic military and civilian health records that would allow for conclusions on the impact of medications are essentially creatures of the later nineteenth century.Footnote 108 The material point, however, is whether it is the historian’s province to pose the essentially ahistorical question of efficacy, and to wrench early modern medicine, and pharmacology, into a twenty-first-century biomedical lexis, and explanatory repertoire, at all. There is overwhelming evidence that ‘efficacy and rapid cures were not part of the cultural expectation of the suffering’Footnote 109 in the eighteenth century, that our historical subjects’ medical horizon of expectation and therapeutic experience differed radically from ours.Footnote 110 What is more, historians have long argued that body knowledge is ‘in and of itself constituting’, productive rather than merely reflective of versions of the diseased body.Footnote 111 Just as any assumption of the constancy of human nature and the human condition is untenable in the face of historians’ heightened awareness of historical singularity and discontinuity,Footnote 112 the act of collapsing past medical experiences into present categories will invariably distort and obscure our understanding of the corporeal experience of the suffering, their bodily anxieties, knowledge and imaginaries. Cinchona’s complexity – the fact that it yields natural alkaloids that are today believed to profoundly affect humans and other living organisms – would have unfolded not only at a scale invisible to the experience of men, women and children in the past, but also at a level that was likely irrelevant to them. This book is greatly indebted to, and draws significantly on, global histories of disease in general, and of malaria in particular. It distances itself, however, from a history written in terms that are not those of its historical subjects and structured in terms of concepts and categories of sickness and therapy not available to past societies.Footnote 113 A Singular Remedy is concerned precisely with the contingency and peculiarity of medical knowledge and the knowledge movement in the past that a presentist approach will obscure. It studies the variety of illnesses and fevers in which the bark was employed, and the profuse medical vocabulary, rich curative repertoire and influential cultural and topographical imaginary that grounded practitioners’ and sufferers’ experience of them.

A Singular Remedy breaks, second, from a historiographical tradition confined to imperial boundaries and frameworks, in its attempt at writing a history of how medical knowledge was shared between and across the Atlantic empires. The tendency among historians of the bark to settle for explanations that can be drawn from events and processes within particular national, or imperial, territories is partly symptomatic of the wider field. Indeed, there are few global histories of health, or medicine in general,Footnote 114 the one exception being the thriving field of historical scholarship on disease, epidemics and contagion.Footnote 115 Even the buoyant literature on medicine trade and therapeutic exchange across the Atlantic basin that had taken shape already from the fifteenth centuryFootnote 116 has commonly been written along imperial lines, with studies focusing on the Dutch,Footnote 117 Spanish,Footnote 118 BritishFootnote 119 or PortugueseFootnote 120 contexts. A tendency to limit the purview to one imperial context among historians of cinchona is also, however, intrinsic to the subject matter, and an effect of the bark’s longstanding association with particular empires and states. Much of the post-1970s English-language historiography, for instance, refers to cinchona almost exclusively as the source of, and precursor to, quinine, a drug that has captured historians’ imaginations owing to its alleged role in British imperial expansion in particular and in the high tide of European imperialism after 1878 more broadly. Malaria – or rather, tropical fevers retrospectively diagnosed as P. falciparum malaria – historians argued, had long represented perhaps ‘the most powerful barrier to the projection of European influence in the tropics’.Footnote 121 Increasingly, systematic quinine therapy and prophylaxis after 1820, in reducing Europeans’ mortality from the disease, enabled French and British colonizers to finally ‘break into the African interior successfully’.Footnote 122 In a tendency perhaps symptomatic of a historiographical tradition enamoured with human scientific and technological ingenuity,Footnote 123 quinine was often considered, alongside submarine cables, breech-loaders and railroads, as yet ‘another technological advance, a triumph over disease’, as Daniel R. Headrick put it,Footnote 124 or, as Richard Drayton re-phrased it, the ‘parable of the relations of mutual benefit struck between science and British Empire’.Footnote 125 Along those same lines, historians have devoted considerable attention to imperial rivalries, particularly the British, Dutch, French and Portuguese attempts at breaking the Spanish Empire’s natural monopoly on cinchona. The British, Dutch and French quest for cinchona surrogates – plant components that promised similar effects, such as tulip tree bark, quassia, gentian root or Winter’s bark – in the Greater Caribbean and South Asia,Footnote 126 the Portuguese pursuit of cinchona varieties on Brazilian territoryFootnote 127 and the long-standing Dutch and British attempts at smuggling and transplanting cinchona seedlings have long received comparatively abundant consideration.Footnote 128 So have, of course, the Spanish Empire’s efforts at managing, regulating and preserving the harvest of and trade in cinchona. There are a series of valuable studies on its administrative organization,Footnote 129 the five – failed – projects aiming to establish a royal monopoly over the barkFootnote 130 and the politics of knowledge, science and expertise attendant to it.Footnote 131 Particularly in the latter field of study, historians of Spain’s imperial project of economic botany – a Bourbon reform effort centred on the exploitation of profitable natural commodities, of which cinchona exports were one cornerstone – have studied the quest for experiences with and classification of new cinchona varieties in botanical expeditions and studies, especially those in the service of the Spanish Crown. In particular, the cinchona research carried out by José Celestino Mutis (1732–1808) in and beyond the framework of the Royal Botanical Expedition to the Kingdom of Granada (1783–1816),Footnote 132 by Jorge Juan y Santacilia (1713–1773) and Antonio de Ulloa (1716–1795), members of the Charles-Marie de La Condamine expedition (1735–1745),Footnote 133 and by the 1778–1816 botanical expedition to the Viceroyalty of Peru headed by Hipólito Ruiz López (1754–1816), José Antonio Pavón (1754–1840) and Joseph Dombey (1742–1794) has attracted considerable attention,Footnote 134 even if mostly on the margins of studies of these men’s wider botanical interests. Scholars from other linguistic or national backgrounds have, likewise, been concerned primarily with the bark’s reception in their various domestic contexts: Finland,Footnote 135 the Ottoman EmpireFootnote 136 or the Habsburg territories, with the German-language literature converging on Samuel Hahnemann’s (1755–1843) self-experimentation with cinchona and its part in the formation of homeopathy.Footnote 137 In virtually all of these studies, developments elsewhere serve principally as a distant backdrop against which a given intellectual, political or economic history may unfold – be that elsewhere in the Spanish American natural habitat, as in the case of British historians of empire, or the consumer societies, for Spanish historians of cinchona production and commerce. While it does not deny the relevance of imperial frameworks, or, indeed, the bark’s implication in them, the purpose of this book is to bring together, synergistically, cinchona’s many elsewheres, in pursuing its object ‘across time, space, and specialism’.Footnote 138 Inspired by a growing body of research on plant trade, epistemic brokerage and therapeutic exchange across imperial boundaries,Footnote 139 A Singular Remedy does not settle for explanations drawn from one territory, denomination or linguistic framework. As various historians have argued, though medicine trade across the Atlantic basin was lively and extensive around 1800, few medicinal substances travelled as widely and were traded as massively as the Peruvian bark.Footnote 140 With its range and reach fully understood and explored – unfettered by a reductionist emphasis on its collusion, and complicity, with either the British or the Spanish Empire – the bark provides a rare, and valuable, window into drug trade, epistemic brokerage and sustained interactionFootnote 141 in the realm of medicine during the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Book Structure

This book covers the period in which the bark was at the height of its popularity: the decades running from 1751, the year when the Spanish Crown issued the royal order that declared cinchona to be ‘an object worthy of interest, curiosity and attention’,Footnote 142 to 1820, when the dislocations of the struggle for independence in the harvest areas and the isolation of quinine, which unfolded through a sequence of experiments conducted in Lisbon, Paris and Jena,Footnote 143 changed the grounds of its production, commerce and consumption. Geographically, it covers an Atlantic World constituted by relations among the continents rimming the Atlantic basin and with other regions, especially the Asian reaches of the Atlantic empires.Footnote 144 Its focus rests in particular on the Viceroyalties of Peru, Brazil, New Granada and New Spain, the Dutch, British and French West Indian possessions, and the French and British North American colonies – or, after 1776, the United States; on the Portuguese, Spanish and British enclaves along the African coast, the Sultanate of Morocco and the Ottoman Empire; on France, England and Scotland, the Habsburg territories, Scandinavia, the Swiss Confederacy, the Italian peninsula and Muscovy; on the Spanish, Portuguese, French, British and Dutch colonial possessions and commercial and evangelizing entrepôts in Qing China, Mughal India and Tokugawa Japan, on Java and the Philippines.Footnote 145

At its core, A Singular Remedy is concerned with how the Peruvian bark and stories, practices and understandings attendant to its consumption were shared between and across Atlantic societies. The five chapters that follow expose and examine the prevalence and movement of narratives about the discovery of the bark’s medicinal properties, of the Peruvian bark as a form of matter, of medical formulae for preparations of the bark, and of understandings of the environs and ailments in which the use of the Peruvian bark would be most beneficial. A Singular Remedy contends not only that bark knowledge – in the shape of matter, words and practices – was movable but that it moved in ways that were contingent upon place and locality – a peculiar culinary lore, cultural imaginary or medical topography. Chapter 1 not only exposes the various story elements present in narratives about the bark’s discovery – the natives’ alleged secrecy, their closeness to nature and unlettered simplicity – as long-lived topoi that served to make sense of, and propagate, the bark’s wonderful properties. It also points to these stories’ divergent reception across the Atlantic World and the part of cultural, religious or political idiosyncrasies in it. Chapter 2 exposes and examines how bottled compound wines and powdered bark moved along the veins of Atlantic trade, proselytizing and imperialism, with their course defined by the situation of these societies’ trade entrepôts, military outposts and diaspora communities. Chapter 3 contends that even though methods for arranging and administering the bark had coalesced into identifiable formulae by the late 1700s and early 1800s – bittersweet febrifugal lemonades, extracts of cinchona and aromatic compound wines of the bark, most notably – these preparations also accommodated a measure of variability. Indeed, medical practitioners tinkered with the particulars of these formulae, adapting them to the religious beliefs, peculiar culinary lore or commercial possibilities of their place of abode. Chapter 4 exposes how bark knowledge was shared in the form of expertise in indications for cinchona, a topographic literacy of sorts that associated certain environments with febrile threat. The chapter holds not only that the period’s medical topography, with its distinct contours of insalubrious, febrile environments, directed the bark to particular situations – the world’s low-lying marshlands, the sickly air of close, crowded spaces, and the hot and humid climates of the tropics. It also exposes how sufferers adapted modes of administration, depending on the season, place or climate they sought to shield themselves from. There is an unspoken premise in much current scholarship that the local and the global are opposites – the dichotomy of a discrete locale that resists change and a placeless global that imposes it.Footnote 146 Not only is that polarity a figment of our scholarly imagination; it is a detrimental one, since it diverts attention from the contingency of both knowledge and its movement. By the late 1700s and early 1800s, knowledge and use of the Peruvian bark was common across a wide range of geographically disperse and socially diverse societies within, or tied to, the Atlantic World, in part because of that substance’s ability to acquire validity, become situated, and weave itself into the fabric of everyday therapeutic practice elsewhere. Both knowledge of the bark and its global movement were, so this book contends, local – as in, related to place, and peculiar to it.

Chapter 5 reminds readers, at parting, once more of how plant trade, therapeutic exchange and epistemic brokerage are not extricable from space. Written in the style of a lengthy coda, it is concerned with how the bark’s prevalence, wide fame and general usefulness in therapeutic practice among disperse societies, affected its natural habitat in the central and northern Andes. The last chapter argues that the bark’s very mobility, and the popular demand that arose for it, altered the area’s landscape of possession, commerce and demographics; the distribution and abundance of vegetation; and the livelihood, health and fate of the men and women implicated in harvesting, processing and conveying the bark. Consumption, and the imaginaries, therapeutic practices and medical understandings attendant to it, it contends, invariably begins with changes to the material world, to physical nature and to society.Footnote 147