The aim of this chapter is to understand the role that the German pathologist and physical anthropologist Rudolf Virchow has come to play, as a historical figure, in the emergence of social medicine as a recognizable set of ideas and practices. The purpose of this exercise is not so much to challenge common assumptions about the value of Virchow’s observations and concepts but rather to contextualize both Virchow’s endeavors and their interpretations by practitioners and historians. We may want to look at this, I suggest, as a case study that helps us to make sense of the role of a celebrated historical figure in an emerging field of practice.

Virchow’s status as a pioneer of social medicine is closely associated with his report on the typhus epidemic in the Prussian province of Upper Silesia in early 1848 and his often cited statement that “Medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine at a larger scale,” which appeared later in the same year in an article published in a journal he edited, Die Medicinische Reform, on how Virchow believed the state should ensure healthcare was provided to the poor.Footnote 1 Virchow’s pioneer status has often been taken for granted, so much so that he and his students are almost automatically assumed to have directly shaped national traditions in social medicine, even when and where, on closer examination, no direct links can be found.Footnote 2

I argue in this chapter that while Virchow’s observations and programmatic writings have been useful for positioning the ideas and practices we associate with social medicine and establish the notion that social medicine has a long tradition, his central place in the historiography of the field is a product of contingencies. The historical figure of Rudolf Virchow has been appropriated and injected into the narrative that dominates the historiography of social medicine, with the implicit purpose of providing the new discipline with a distinguished pedigree and specifically because his early concepts and observations provided useful signposts, in combination with his standing as a great medical scholar who made his name above all as a pathologist and anthropologist. Virchow was a key champion of biomedicine in late nineteenth-century Germany. By biomedicine here, I mean scientific medicine taught at universities, embracing hands-on research, dedicated to materialism and empiricism, and firmly rooted in pathological anatomy and the new experimental physiology pioneered by men such as Johannes Müller, one of Virchow’s mentors, or François Magendie in France.

Virchow’s conceptual legacy in this area is most closely associated with cellular pathology, the proposal that the structural and functional unit of all life was the cell, and that physiological and pathological processes could be most effectively studied and most conclusively understood at the cellular level. Cellular pathology provided an outstandingly productive framework for a wide range of biomedical research programs and, arguably, is still one of the central doctrines of biomedicine. Later in life, Virchow focused his scholarly efforts on institutionalizing anthropology as a scientific pursuit, encompassing what we today term “physical anthropology,” as well as ethnography and archaeology. In this context, he was a key promoter, for example, of the activities of Heinrich Schliemann, the “discoverer” of the ancient city of Troy. Throughout his career, Virchow also dedicated much of his time to politics, as a champion of reform, and, as will be discussed in more detail below, temporarily revolution. He was a member of legislative assemblies at municipal, regional, and national levels and held a number of administrative roles, mostly related to public health.

Social medicine for the purposes of this chapter is best understood as a unifying methodological and theoretical framework underpinning preventive medicine and public health, but also as a fundamental reinterpretation of what medicine should aim for and what the object of intervention should be: the social body rather than individual bodies. As such, it is important to interpret social medicine not as a timeless concept but as a historically situated phenomenon that emerged from a specific context in the mid twentieth century in North America and Britain but with major input from émigré scholars from German-speaking Central Europe.Footnote 3 I will argue that Virchow did not develop a concept of social medicine, as is often assumed, but that he was written into the genealogy of the new concept by those who had an investment in this concept and the ways in which it linked North America to Europe, namely the historian of medicine, public health official, and scholar of public health, George Rosen and some of his associates. In doing so, they initiated a partial shift in the perception of Virchow, reversing the timeline of Virchow’s biography, from pathological anatomist and physical anthropologist to political radical, by emphasizing activities and writings early in Virchow’s career. Virchow’s celebrated statement resonated with the self-understanding of early to mid twentieth-century public health practitioners (and theorists) who prioritized addressing the roots of public health problems in health policy over technical interventions.

I will be approaching this chapter from two directions. First, I will look at Virchow’s journey to Upper Silesia in 1848 and his experiences in the revolutionary upheavals of that year in an attempt to understand what Virchow imagined when he thought of politics as medicine on a larger scale.Footnote 4 Given the enmeshedness of the typhus fact-finding expedition, which has become emblematic in the historiography of social medicine, with Virchow’s role as a revolutionary, and his early programmatic writings on medical and public health reform, I argue that the contingencies shaping this particular nexus deserve a closer look. I will then examine the historiography of social medicine, seeking to understand how and why the historical figure of Rudolf Virchow has come to assume such a central place in this historiography. I will very briefly compare appropriations of Virchow in different traditions of social medicine. I argue that historians of medicine especially, such as Henry Sigerist and George Rosen, who were trained in German-speaking Europe and who campaigned for social medicine as an academic discipline in the US, played a crucial role in this story. George Rosen’s writings are cited centrally by most authors seeking to situate social medicine historically. I argue that Rosen’s representation of Virchow was much more important for modern, post-Second World War understandings of social medicine than the man himself. Rosen employed Virchow because this allowed him to trace the roots of these understandings back to a period which is generally viewed as the time when the foundations of modern biomedicine were established and thus gave the fledgling discipline more gravitas, depth, breadth, and coherence than it may otherwise have been perceived to have.

Revolution and Typhus in Silesia

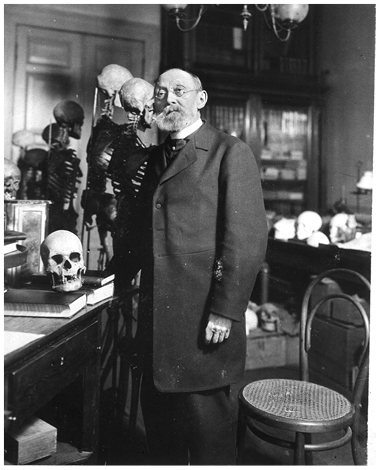

By all accounts, including his own, the ambitious young physician and medical academic Rudolf Virchow (Figure 1.1) was disgusted by what he encountered in Upper Silesia in 1848. It was the beginning of a year that was an important turning point in the history of Prussia and the other states and principalities that made up the German Confederation: a year of political and social upheaval and revolution, a peculiar mix of uncertainty, hope, and excitement.

Figure 1.1 Virchow around 1848.

The year was also a turning point in Virchow’s life and career. He was twenty-six years old, and freshly appointed to the office of Prosector at the Charité Hospital in Berlin. He had completed his doctoral dissertation in 1843 with the influential physiologist and anatomist Johannes Müller. In 1846, he had passed the state examination that qualified him to practice as a physician. In 1847, he had completed the second dissertation (Habilitation) that gave him the right to teach university students – a key step toward a professorial career. He had also, with a friend, launched a journal, the Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin (later known as Virchows Archiv and a key outlet for biomedical research in Germany, still in existence). In 1848, however, along with most other intellectuals in Berlin and other cities of the German Confederation, he devoted much time to being a revolutionary. He joined the Berlin barricades and various assemblies and committees dedicated to making the revolution deliver sustainable change. He also launched a second, short-lived journal with another friend, the psychiatrist Rudolf Leubuscher, Die Medicinische Reform, which was the main publishing outlet for Virchow’s political thoughts. The first issue of Medicinische Reform was published on July 10, 1848 and the last on June 29, 1849.Footnote 5

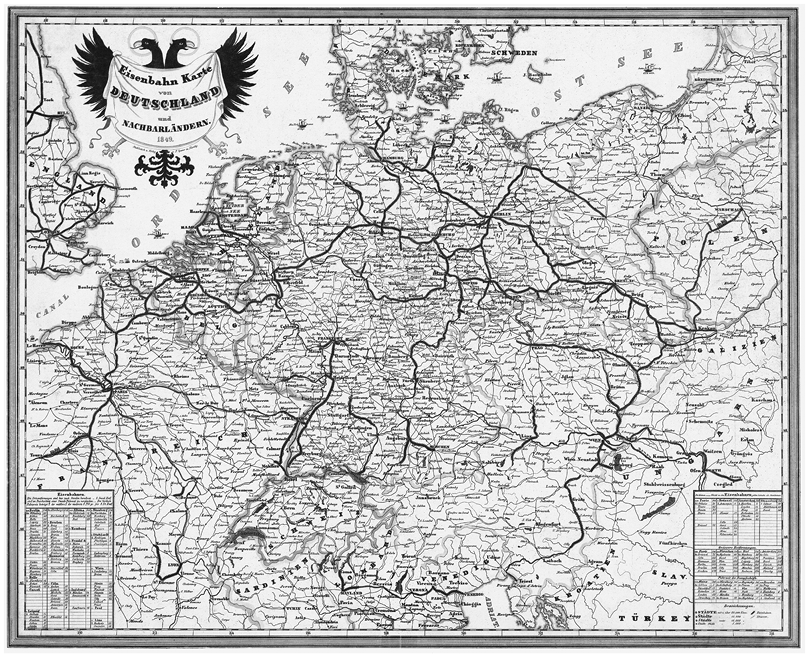

The outbreak in Upper Silesia of what Virchow referred to as “hunger typhus” (Hungertyphus) had started to receive considerable attention in the capital Berlin by early 1848 and not only among reform-minded physicians. The newspapers were reporting the outbreak and rumors were circulating about it, along with there being appeals for help for the victims. The Prussian minister in charge of Culture, Education, and Medical Matters, however, had received no reliable reports from local officials and, after some delay, the government grew concerned about the potential consequences of the epidemic (and presumably the rumors). The minister commissioned one of Virchow’s senior colleagues at the Charité, the professor of pediatrics, Stephan Friedrich Barez, with a fact-finding visit to the affected area in the southeastern corner of the state of Prussia and also to offer advice to the locals. Virchow was invited to join Barez, with the request to undertake a scientific investigation into the outbreak. On the train from Berlin on the new Niederschlesisch-Märkische Eisenbahn, a line completed a couple of years earlier, Barez and Virchow were able to reach Breslau in Lower Silesia in a single day (previously, by stagecoach, this would have been an arduous journey, taking a week or longer; see Figure 1.2).Footnote 6

Figure 1.2 Railway map of Germany in 1849. Upper Silesia is located on the right, along the railway line to Krakow.

They set off in the Prussian capital on February 20 and arrived in the town of Ratibor in Upper Silesia on February 22. They visited a few other towns and villages in the province: Rybnik, Radlin and Loslau, Gleikowitz and Smollna, Sohrau, Pless, and Lonkau. Barez traveled back to Berlin on February 29. Virchow stayed in Sohrau until March 7, very comfortably, at the castle of Count Hochberg, a local aristocrat and large landowner, whom Virchow praised as a generous host.Footnote 7 He spent some time observing the work in a hospital set up specifically to look after victims of the epidemic. On March 10, he also arrived back in Berlin. He would have liked to stay longer, he writes, but had an even stronger urge to participate in unfolding revolutionary developments in Berlin. News of a popular uprising in Paris and the proclamation of the Second French Republic had reached the Prussian capital on February 27 and was reported by the liberal Vossische Zeitung on February 28, followed by news of uprisings in a number of southern German states. On March 6, a large people’s assembly was held in Tiergarten, not far from the Brandenburg Gate – the beginning of what came to be known as the March Revolution in Prussia.

Virchow’s report on his visit to Upper Silesia, 182 pages long, was published later in the same year. It is a report on a substantial piece of epidemiological fieldwork (which is surprising, given the brevity of the visit), with an opening section on the land and its people, a section on endemic conditions in the area and the story of the typhus outbreak under investigation, a third, long section on clinical observations and a discussion of possible causes, and a final, fourth part on possible interventions.Footnote 8 So what did Virchow actually find, how did he make sense of it, how was his perception of the epidemic shaped by the contingencies of the revolutionary developments, and how, in turn, did these experiences shape his outlook as a medical reformer, advocate of public health, and health policy maker?

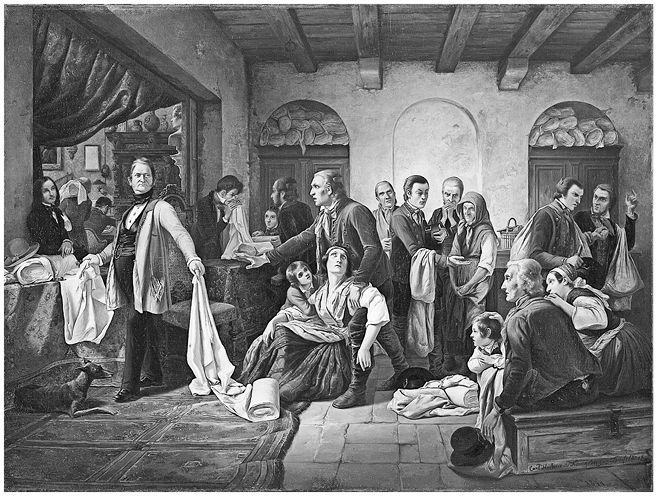

Especially striking are Virchow’s descriptions of the people of Upper Silesia. On the one hand, he explicitly acknowledges that the ethnically Polish, Catholic population were victims of 700 years of colonialization by Protestant Prussia, an exploitative and utterly incompetent administration controlled by large land owners, and centuries of spiritual enslavement by Catholic religious leaders. Virchow writes: “700 years have not been sufficient to free the inhabitants [of Upper Silesia] of their Polish habitus, which their brothers in Pomerania and Prussia have lost completely. However, they have been sufficient to destroy their consciousness, to corrupt their language, and to break their spirit.”Footnote 9 A growing population (from 42,303 in 1834 to 59,320 in 1847) was living in overcrowded, damp, and unhygienic dwellings, which they shared with livestock (Figure 1.3). The authorities had made some attempts to supplement their increasingly poor diet following several failed potato harvests but in ways that did not make sense to Virchow. On the other hand, his descriptions suggest that he was disgusted not only by the conditions but also by the people themselves.

Figure 1.3 Carl Wilhelm Hübener, The Silesian Weavers (1844). This painting illustrates a growing awareness in Germany of the fate of poor Silesian workers and the social question more generally.

The habits of the Silesians, Virchow observes, were utterly uncivilized: they did not wash and the crusts of dirt on their bodies were only occasionally washed away by the rain; vermin such as lice were “permanent guests” on their bodies.Footnote 10 They were “dedicated to the consumption of liquor in the most extreme manner.”Footnote 11 Also, they were subservient like dogs, Virchow writes, and totally disinclined to engage in any intellectual or physical effort, thoroughly lazy, in ways that was bound to trigger disgust rather than pity in any free human being with a good work ethic.Footnote 12 The Polish inhabitants of Upper Silesia were the “Other” to the young, liberal, hardworking intellectual visiting from Berlin to investigate the causes of the typhus epidemic. However, he made clear that he blamed the exploitative structures for the deplorable characteristics displayed by the locals, signaling a belief in human improvement that quite clearly had its roots in Enlightenment values. He appeared to appeal to enlightenment as the key to a solution.

The epidemic of typhus Virchow was asked to investigate had started in summer 1847. The victims developed an increasingly high fever, accompanied by extreme fatigue, headache, sometimes loss of hearing and delirium, aching limbs and sharp pain in the feet, fast pulse and often a cough, and a characteristic skin rush. Between the ninth and fourteenth day, this was followed either by (slow) convalescence or a crisis and death. Incidence and mortality figures communicated to him by various officials and local physicians varied. In a community in Ratibor County, for example, according to the numbers reported to him, just under 9 percent of the population were ill and out of these, just over 40 percent died. During a meeting of doctors in the county of Rybnik, organized when Virchow was visiting, some estimated that mortality was as high as one in three. Others assumed 10–20 percent mortality. Virchow concluded that the exact mortality was uncertain, the available data were not reliable enough. Gender, age, or ethnic origin seemed to make no difference – the disease could affect anyone. Virchow undertook four post-mortem examinations and included detailed accounts of his findings in his report, reflected on reports of other autopsies, and reviewed a wide range of literature on typhus and related conditions, going back to Hippocrates and including much recent writing from England and Ireland.

The key question was the following: was the typhus observed in 1847 and 1848 qualitatively different from endemic typhus? Some assumed that the typhus was passed on through a contagion, others suggested that it was caused by miasma, perhaps a product of fermentation, in environmental conditions not particularly good for human health. Virchow conceded that the poor conditions would have made the Silesians increasingly susceptible to any miasma that may have been emerging in their damp and moldy dwellings. But ultimately we had to assume, based on what he had seen and read, that the epidemic and the famine were caused by the same conditions. In a letter to his father, he stated clearly that he did not believe that the hunger caused the typhus but that it promoted the spread of the disease.Footnote 13 As typhus was endemic in the region, the cause had to be endemic and the hunger was just a contributing factor making people more susceptible. The real cause, Virchow concluded, was a miasma, a product of chemical decomposition, which led to an epidemic under certain weather conditions and was made worse by the circumstances in which the people were living. The miasma poisoned the blood of typhus patients and, in turn, caused the pathological changes Virchow and others had observed in post-mortem examinations.

Virchow also reported on the measures taken to gain control of the epidemic between the time of his visit and the time of publication: relatively simple measures focusing on providing those affected by the typhus with clean surroundings and food and when absolutely necessary, a hospital bed. There was some emphasis on controlling cost and on reporting, and indeed, by the summer, incidence declined dramatically. However, as typhus incidence was declining, other conditions such as intermittent fever returned. How could one prevent future epidemics? Virchow had drawn his conclusions from what he witnessed in Upper Silesia when he returned to Berlin. His conclusions could be summarized in three words, he wrote: “full, unrestricted democracy.”Footnote 14 It is not easy to reconcile this conclusion with the visceral disgust Virchow appears to have felt when dealing with the sick Upper Silesians. Nevertheless, the last twenty-five pages of the report are a call for revolution. The famous Prussian bureaucracy could not save the people of Upper Silesia, Virchow argued. Only democracy could bring about the structural change needed to liberate and educate them. And Virchow was determined, he declared, to help bring about such a revolution.

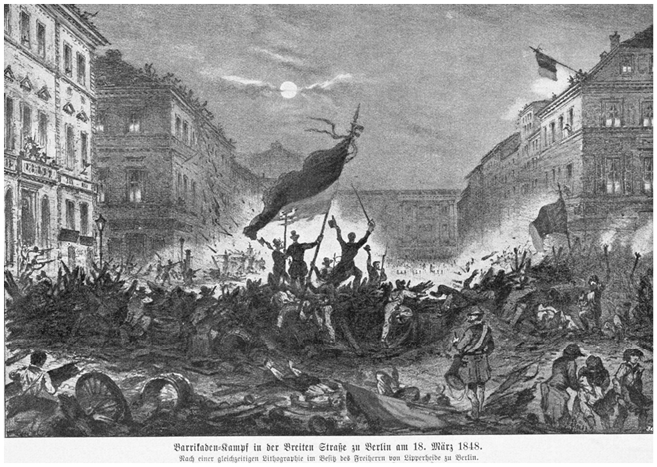

Back in Berlin, Virchow dedicated much of his time and energy to the revolution. He took part in assemblies from the very day of his return onward, and as the Prussian king mobilized the army and clashes in the streets of Berlin grew violent, within less than a week of his return, Virchow was joining the barricades on the corner of Friedrichstrasse and Taubenstrasse, fighting against the King’s Regiment from Stettin. As he reports in a letter to his father, the soldiers had canons, the revolutionaries only twelve guns. Virchow himself had a pistol. Despite the overwhelming firepower of the army, the revolutionaries held many barricades and erected more. Many were wounded or killed and buildings were damaged. The army withdrew and the king promised concessions (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Barricade in Berlin, 1848.

On March 24, Virchow wrote to his father, enthusiastically, that the revolution had been completely victorious.Footnote 15 He successfully ran for election to the electoral college for the new national parliament in his district and joined a number of committees and assemblies, while working on the report on Upper Silesia. By summer, on a typical day, he was attending one or two committee meetings, assemblies or club meetings in the afternoons and evenings, after finishing his teaching and work as a prosector in the morning. Politically he located himself on the “extreme left,” even if he did not always agree with the means, he wrote, that the left used to achieve their aims.Footnote 16 With some of his physician friends he started to draw up plans for a radical reform of medicine. The reflections on what such a reform might entail provided the context for the much cited statement on medicine as a social science.

As a committee member of the Society for Obstetrics, which was chaired by his friend and future father-in-law, Carl Mayer, Virchow acted as a delegate in a series of meetings, many of which he chaired, dedicated to medical renewal – envisaged by Virchow and his friends as a root-and-branch reform of the health system. In July 1848, with his friend, the psychiatrist Rudolf Leubuscher, he launched a journal dedicated to these matters, Die Medicinische Reform.Footnote 17 The main reasons for the end of the journal, less than one year later, were financial problems, along with frustration over the failure of the revolution in general and specifically with a view to Virchow’s ideas for medical renewal. What did Virchow envisage?

Virchow positioned himself as a democrat and a socialist but the ideal society he had in mind is perhaps best characterized as a paternalist technocracy, with medical doctors in key positions as experts, guided above all by their understanding of the natural sciences. This resonates with his distrust, even disgust for the poor in Upper Silesia. Virchow envisaged a privileged role for medicine in the running of the state.Footnote 18 The protection of people’s health was going to be central to the reformed state. With his ideas for medical reform, he drew on proposals by his friend, the physician Salomon Neumann, who suggested that government had a duty to assure the health of its citizens. Healthy bodies were the only property that the poor controlled. As the government had a duty to protect property, protecting the health of the poor had to be recognized as a key duty of government and, thus, an important goal for medical reform. Neumann called for the right to health to be declared a human right.Footnote 19

Virchow suggested that doctors were “the natural advocates of the poor” and that social questions should come “predominantly under their jurisdiction.”Footnote 20 He envisaged that an association of all medical doctors should be put in charge of all matters related to health. Doctors were going to be exclusively guided by reason. Virchow’s ideas were rooted in a strong and persistent Enlightenment belief in the primacy of reason and the transformative power of the natural sciences for all areas of life, which he shared with other students of the physiologist Johannes Müller, such as Hermann Helmholtz or Emil Du Bois-Reymond.Footnote 21 Guided by reason under the leadership of doctors who were applying their anthropological knowledge, the social question would be solved.

Virchow had to adjust his expectations, it seems, when he found himself confronted with the tediousness of practical politics and the lack of support from his medical colleagues. Many did not share his commitments, were reluctant to dedicate themselves to working for medical reform in associations and revolutionary meetings, and did not agree with his idea of compulsory membership in an association of doctors. They did not even subscribe to the Medicinische Reform in sufficient numbers to make the journal financially viable.

His visions conflicted with the ideas of other revolutionaries also in another crucial aspect: a solution of the social question to Virchow did not imply the emancipation of workers and the poor. The solution of the social question to him implied the disappearance of the mob (der Pöbel), not the involvement of the mob in practical politics. It is plausible to assume that his disgust with the wretched typhus patients in Upper Silesia was related to his perception of the revolutionary mob in Berlin. His report from Upper Silesia did not include patients’ perspectives and Virchow’s vision of medical reform did not assume that patients and other non-experts were going to be involved in decision-making processes around health and medicine.Footnote 22

Afterlife: The Making of a Social Medicine Pioneer

While he self-identified as a left-wing Democrat, Virchow’s politics was patriarchal, based on the assumption that doctors knew better. The embrace of social science was ambition rather than reality. While the young pathologist had supporters in the Prussian administration and was much respected, his involvement in the revolutionary activities of 1848 and 1849 did lead to sanctions. Virchow was not sacked from his positions but his pay was cut and he lost the apartment that originally came with the position of prosector. In May of 1949, he was offered a chair appointment at the University of Würzburg. He accepted, moved, got married, and stopped identifying as a revolutionary.

Virchow’s biographers agree that the Würzburg phase was when Virchow established his reputation as Germany’s leading pathologist. Schipperges characterizes Virchow’s time there as “seven fat years.”Footnote 23 He continued to edit the Archiv, turning it into a key journal for the new scientific approach to medicine that he championed, and from 1854 he published his influential Handbuch der speciellen Pathologie and Therapie. In 1855, the term “cellular pathology” appeared in print for the first time, providing the foundation of a new concept for making sense of health and illness, which shapes our thinking about cancer and other conditions until the present day.

In 1856, Virchow returned to Berlin with a chair appointment. In the following year, he was elected as a member of the Berlin city council, which was the start of his career as a politician. In 1861, he was elected to the Prussian Parliament as leader of the German Progress Party (Fortschrittspartei). From 1880 to 1893, he was also a member of the national parliament, the Reichstag. Throughout his career, he was a member of a variety of committees and working parties, and in Berlin he played an important role as a sanitary reformer, campaigning for and overseeing the construction of a new water and sewage system for the city.

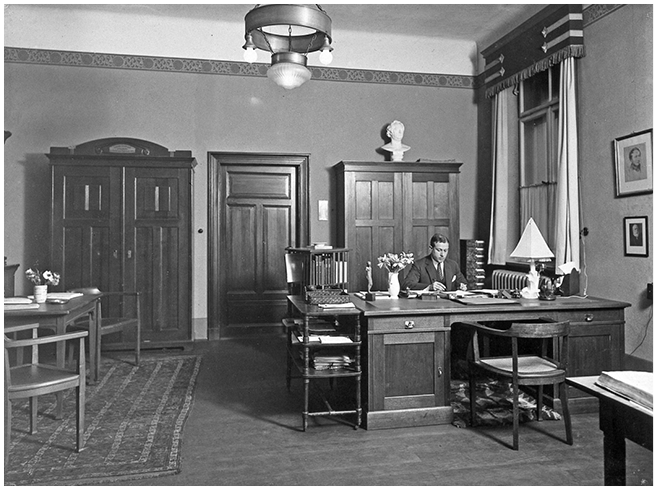

An increasingly influential medical academic and politician, Virchow did not renounce his writings in Medicinische Reform. While acknowledging that he no longer agreed with every word, he republished key texts from this journal in 1879.Footnote 24 Schipperges argues that his programmatic desire to develop a humane politics based on natural science remains a central motivation of Virchow’s actions. Politics was medicine on a large scale and scientifically trained doctors the ideal politicians. The main focus of his scholarship by then, however, was on pathology and anthropology (Figure 1.5). As champion for the natural sciences, he was also a regular participant and speaker on the great scientific controversies of the time at the meetings of the Gesellschaft deutscher Naturforscher und Ärzte (Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians). Given Virchow’s great political ambitions, however, Schipperges suggests that his practical impact was relatively limited.Footnote 25

Figure 1.5 Virchow later in life, in his study, surrounded by skulls and skeletons.

Immediately following his death in 1902, Virchow was celebrated above all as a pathologist, a physical anthropologist, and a politician. His conceptual interest in social and economic factors as causes of disease was reevaluated, in light of a widespread perception in German-speaking Europe, in the interwar period, that medicine was in crisis.Footnote 26 Commentators on the political right tended to view Virchow as part of the problem: the fragmentation that they thought was characteristic of modern, scientific medicine. Those on the left, in contrast, viewed his social engagement and especially his declared commitment to medicine as a social science as a pioneering contribution to a potential solution.

In order to appreciate George Rosen’s role in reinterpreting Virchow, it is helpful to look at biographical accounts prior to Rosen’s two programmatic articles in the late 1940s and perhaps particularly the chapter on Virchow in Henry Sigerist’s Great Doctors, published in German in 1932 and in English translation in 1933.Footnote 27 Sigerist grew increasingly interested in sociological questions and approaches during his time as director of the Leipzig Institute of the History of Medicine, from 1920 onward (Figure 1.6).Footnote 28 However, in Great Doctors, first published in English in 1933, Sigerist presents Virchow as the key protagonist of a new medicine based on natural science, not the study of social conditions. While he dedicates a couple of pages to Upper Silesia, a long quote from the end of Virchow’s report, and his participation in the revolution, there is no notion of Virchow as a founder of social medicine. Most space is dedicated to cellular pathology and the increasingly central role of the pathological institute and the laboratory for the new scientific medicine. The focus on laboratory medicine, however, was what in the eyes of many early twentieth-century critics caused the crisis of medicine.Footnote 29

Figure 1.6 Henry Sigerist in his office.

This is presented very differently in George Rosen’s 1947 essay in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, where Rosen attempts a “genetic analysis” of the concept of social medicine, characterized by Fee and Morman as “rambling,” while “would-be seminal.”Footnote 30 Fee and Morman suggest, convincingly in my view, that the purpose of the paper was “to provide social medicine with a long and distinguished tradition and thus help strengthen the currents of social medical thought within contemporary medicine.”Footnote 31

Rosen starts his exploration of the historical origins of the concept of social medicine with Virchow, or to be precise: with the faint praise that Virchow’s report on the typhoid fever epidemic in Upper Silesia received from the bacteriologist Emil von Behring in 1893. Bacteriology, of course, was synonymous with laboratory medicine. Von Behring presented Virchow’s understanding of the outbreak as caused by “a complex of social and economic factors” as outdated because he believed that bacteriology made all of these complex considerations unnecessary. In the early decades of the twentieth century, however, as Andrew Mendelsohn has shown, it became clear that this was not the case. Epidemics had become complex once again, feeding into the general sense of crisis.Footnote 32

Citing Virchow’s statement that, “Medicine is a social science, and politics nothing but medicine on a grand scale,” Rosen then uses Virchow (along with his associates Salomon Neumann and Rudolf Leubuscher) to develop a programmatic concept of social medicine, which was integrally linked to democratic principles and the assumption that the state should assume a proactive role in the maintenance of public health.Footnote 33 The concept of social medicine that Rosen attributed to Virchow, Neumann, and Leubuscher was founded on three central principles: (1) that “the health of the people is a matter of direct social concern,” (2) that “social and economic conditions have an important effect on health and disease, and that these relations must be subjected to scientific investigation,” and (3) that “steps must be taken to promote health and combat disease, and that the measures involved in such action must be social as well as medical.”Footnote 34 As a central motivation for Virchow’s support for revolution, democracy, and social medicine, Rosen cites a letter by Virchow to his father, in which Virchow declared that he was “no longer a partial man, but a whole one, and that [his] medical creed merge[d] with [his] political and social creed,” thus indirectly suggesting that the embrace of social medicine may also be a solution to the fragmentation of scientific medicine in the early to mid twentieth century.Footnote 35

Why did Rosen turn to Virchow in search for historical support for his concept of social medicine? Rosen, born in 1910, was the son of Jewish immigrants to the US. After graduating from Peter Stuyvesant High School and the College of the City of New York, he found himself excluded from Medical School due to access restrictions for Jewish students. In 1930, he enrolled at the University of Berlin, along with two Jewish American companions. In 1933, he approached the new Director of the Berlin Institute of the History of Medicine, Paul Diepgen, about an MD dissertation topic.Footnote 36 Diepgen encouraged him to contact Henry Sigerist, who by then had moved to Baltimore. Sigerist suggested he wrote on the European reception of the work of William Beaumont, a nineteenth-century American physician and physiologist. After Rosen’s return to the US, he met Sigerist in person at a symposium on the history of industrial and occupational disease held at the New York Academy of Medicine in 1936. This was the beginning of Rosen’s informal but close affiliation with the members of the Johns Hopkins Institute for the History of Medicine.Footnote 37

Rosen’s engagement with both the history of medicine and public health activism and administration is key to understanding his motivation for developing a new social approach to medicine and unpacking the genealogy of the ideas that may have informed this approach. Unable to find a full-time post in the history of medicine, Rosen took the civil service examinations and in 1941 joined the New York City Department of Health as a physician in the Bureau of Tuberculosis. He also enrolled as a graduate student in the Sociology Department in the Graduate Faculty of Political Science, History, and Philosophy at Columbia University, studying with Robert Lynd, Robert Merton, and Robert McIver and focusing on medical sociology. In 1943, Rosen’s History of Miners’ Diseases was published, which correlated the growth of knowledge on these diseases with the social and economic conditions that Rosen believed played a major role in causing them. He was awarded his Doctorate in Sociology in 1944 and in 1946 returned to public health work in the NYC Health Department, while at the same time engaging in formal studies at the School of Public Health at Columbia University, where he was awarded his Master of Public Health degree in 1947.Footnote 38 Rosen practiced what he wanted us to assume Virchow preached: he approached medicine as a social science, in the service of public health.

The immediate pretext to Rosen’s two articles introducing his ideas around social medicine and establishing Virchow as one of its pioneers, appears to have been an initiative of the Milbank Memorial Fund, which held its annual roundtable meeting at the New York Academy of Medicine in 1947. The New York Academy of Medicine, on the occasion of the Academy’s centennial celebration, held what they announced, confusingly for a reader in the early twenty-first century, as an “Institute for Social Medicine,” which in effect was a symposium.Footnote 39 Rosen was asked to speak on the development of the concept of social medicine, covering the 100-year period from 1848 to 1948. In a letter to Sigerist, he reflected that:

in looking over this paper, which by the way will appear in the January 1948 Milbank Quarterly, as well as the one I read last March at the Academy meeting, and the one at the Cleveland meeting it struck me that they actually form an outline for a history of the Idea of Social Medicine, of the theory of social medicine from the eighteenth century to the present.Footnote 40

Rosen’s approach may have been informed by the crisis debate in German medicine in the early twentieth century, but he wrote the essay in 1948, when it was already obvious that a different, much more comprehensive approach to welfare than had ever before been seen, was being embraced in many European countries. The year 1948 was when the National Health Service was launched in Britain and Rosen mentions the foundational Beveridge Report approvingly. The paper also includes a critique of the apparent reluctance of medical and political elites, especially in the English-speaking world, to whole-heartedly embrace the proactive pursuit of public health as part of a comprehensive concept of social medicine and as a central remit of a modern welfare state.

Conclusion: Virchow and Social Medicine

Virchow’s famous statement predated Bismarck’s social insurance reforms and thus the beginnings of the welfare state by four decades. In fact, while he presents Virchow as the pioneer, Rosen looks to the ideas around social hygiene, developed by the likes of Alfred Grotjahn, as a model for his concept of social medicine. Grotjahn did not have his ideas from Virchow. Grotjahn, who qualified as a doctor in 1894 and then worked as a general practitioner in Berlin, actually received training in the social sciences when he attended the seminars of the Nationalökonom Gustav Schmoller at the University of Berlin.Footnote 41 While certainly not a revolutionary, Grotjahn was one of very few professors in German medicine in the early twentieth century who openly supported social democracy. He was a member of the Social Democratic Party and a member of the Reichstag for a few years in the early 1920s.

Where does this leave us with our attempt to reassess Virchow’s role? Virchow found that the democratic ideal of the sovereignty of the people could not easily be reconciled with the primacy of reason that he envisaged for the future of Prussian politics following the March Revolution of 1848, based on the application of natural science and overseen by physicians pursuing the same ideals that he embraced. The revolutionary impulse may have led him to dismiss the frequently praised Prussian bureaucracy and hail democracy as key solution to the problems he witnessed in Upper Silesia but the democracy he was calling for was not universal; he was envisaging a republic of experts, which would necessarily lead to the disappearance of “the mob.”

When I was thinking about how to square Virchow’s commitment to democracy and socialism with his disgust with the poor and the ways in which they lived in Upper Silesia, I started to wonder if it might help to turn to the postcolonial historiography of medicine for a different perspective than that taken in most traditional accounts assessing Virchow’s role in the history of social medicine.Footnote 42 Reading Virchow’s account of his brief expedition to Upper Silesia in the context of his experiences during the Revolution suggests that we do not need to look for colonies to find the patterns that characterized colonial medicine: an othered population on the margins of society, living and working in poor conditions, governed by an elite whose members were representatives of the metropolis, who may show compassion but feel little kinship with the locals. Virchow deplored these conditions but merely wanted to replace the rule of the backward old elite with the rule of enlightened, progressive experts. This is not an approach that George Rosen would have endorsed in 1947.

By shifting emphasis away from Virchow’s status as the father of cellular pathology and champion of (physical) anthropology and by presenting him as a pioneer of the kind of social medicine that Rosen championed (and embodied) in the mid twentieth century, we may want to argue that Rosen decentered Virchow. Authors, especially in the Americas, drawing on Rosen’s vision of social medicine, followed his lead.Footnote 43