Since the end of World War II, the balance between civilian and military voices in the formulation of national security policy had leaned decisively in favor of the OSD and its civilian authorities. In its early years, military voices dominated the NSC, but with the Defense Reorganization Act of 1958 and then McNamara’s tenure, these voices were ever more distanced from the process of setting national security strategy. McNamara reduced his own office to one primarily concerned with managing defense agencies and aligning military tools and resources to the President’s overarching strategy. He positioned the office as a pivot for foreign policy in a way that derived from his particular conception of his job as Secretary of Defense and of what he, as well as the administration, considered to be the appropriate nature of civil-military relations. For McNamara, the Secretary of Defense served the President, and the services were there to provide tools, and not policy guidance, in the execution of foreign policy. McNamara favored “subjective control”: he implemented processes and rules that were designed to reinforce civilian authority and to erode the institutional autonomy that the military services had heretofore enjoyed.

McNamara’s changes within the Defense Department came at a time when President Kennedy began dismantling the NSC structures that his predecessor had built up for foreign and defense policy. Together with McNamara’s personal influence on the President, these changes paved the way for the OSD to become ubiquitous on many foreign policy issues and eventually on Vietnam. Paradoxically, although McNamara’s reforms were designed to limit the role of the Defense Department in national policy formulation, they resulted instead in his office becoming far more influential.

McNamara came to office with a reform agenda that his predecessor, Thomas Gates, had essentially already laid out for him. Above all else, the Defense Reorganization Act of 1958 was concerned with centralizing control over strategy and operations in the hands of the President and his civilian advisors. In time, each of the act’s objectives were, albeit imperfectly, implemented through what became McNamara’s landmark reforms. As the act had anticipated, McNamara and his Deputy, Roswell Gilpatric, centralized authority in their hands in an unprecedented manner.

The act called for “integrated policies and procedures” in national security policy. To achieve this objective, McNamara introduced Draft Presidential Memoranda (DPMs) that provided strategic guidance on which force levels were planned for. Finally, it called for economies and efficiency gains. To this end, McNamara introduced systems analysis and the Planning, Programming and Budgeting System (PPBS) that “rationalized” the budgetary process in a groundbreaking way.

Each of McNamara’s reforms was concerned with aligning civilian and military objectives. Much like Eisenhower before him, McNamara believed that in order to achieve this alignment, the administration needed a guiding grand strategy and civilian “security intellectuals.” The latter could inform defense policy in a way that allowed the Secretary of Defense to “avoid becoming a captive of the Chiefs and the Joint Staff and the Generals,” and what McNamara saw as their parochial bureaucratic interests.1 McNamara acknowledged that while Eisenhower and Secretary Gates had made some progress in producing an overarching strategy, they had failed to produce a detailed strategy that could usefully serve as a basis for long-term defense planning and budgeting.2

Informed by the Defense Reorganization Act, McNamara also felt that the President should have greater control over the formulation of national security policy to the detriment of military voices. Charles J. Hitch, McNamara’s Comptroller and a leading “security intellectual” in his department, recalled that “Robert S. McNamara made it clear from the beginning that he intended to be the kind of Secretary that President Eisenhower had in mind in 1958.”3 McNamara explained what this “kind of Secretary” was: “I believed, for example, that there must be a definite integration of defense policies and programs with State Department policies. Military strategy must be a derivative of foreign policy. Force structure is a derivative of military strategy. Budgets are a derivative of force structures. So in a very real sense, a defense budget, in all of its detail, is a function of the foreign policy of the nation.”4 McNamara was to be the civilian manager who executed this neat alignment.

McNamara moved to cut back the Chiefs’ power in designing national security policy in part because he sought neat alignment with foreign policy objectives but also because both he, and arguably the Kennedy administration as a whole, lacked respect for the Chiefs, who were deemed out of step with their times. Many of the administration’s senior advisors had also served in some capacity during the war, and according to the in-house historian Arthur Schlesinger, “The war experience helped give the New Frontier generation its casual and laconic tone, its grim, puncturing humor and its mistrust of evangelism.”5

Although McNamara had served under General Curtis LeMay in the US strategic bombing campaign during the war, once he came to office and with the General now Chief of Staff of the Air Force, whatever respect he had had seemed to evaporate. The young Secretary felt that neither of his Generals “got it” and seemed especially irritated with his old boss, who needed a hearing aid and did not reflect the tenor of the New Frontier either physically or intellectually.6 For his part, the President mirrored this chasm: he always referred to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Lyman Lemnitzer as “General,” a mark, as one colleague remembered, “that he didn’t like him.”7

Very quickly, the administration neither gave the Chiefs’ views a central role nor valued their intellectual contributions. McNamara remembered, “It never bothered me that I overruled the majority of the Chiefs, or even occasionally the unanimous recommendations of the Chiefs. It didn’t bother me in the slightest.”8 McNamara’s will to impose his authority and his condescending attitude toward military institutions and leaders drove his attitude. For instance, McNamara refused to speak at military colleges, telling his friends, “These are not worthy academic institutions, and I will not lend my presence to them.”9

From an organizational point of view, McNamara became dominant in the administration and loomed large across the board on Kennedy’s foreign policy but especially on Vietnam for a number of reasons. First and foremost, he centralized authority around his office. Making good on Eisenhower’s reforms, the JCS now reported to him rather than directly to the President. In turn, this centralization of authority meant that McNamara could come to the President with one, clear position for his department. Given that Kennedy’s dismantling of the NSC structures had resulted in somewhat chaotic decision-making in the administration, this clarity gave McNamara enormous power. Finally, his personality and bullishness, if not authoritarianism, coupled with his personal connection to Kennedy gave him an advantage over other actors involved in national security decision-making.

McNamara’s changes to the budgetary process also reflected a move to impose “subjective control” over the Chiefs. This ultimately strained relations with congressional leaders as well. One flash point in these deteriorating relations occurred during what came to be called the “muzzling hearings.” McNamara’s Special Assistant, Adam Yarmolinsky, had asked that all senior military officials’ public statements be sent to his office for clearance in order to remove “color words.” As McNamara later explained, the administration was “annoyed” that military leaders “were exaggerating the [Communist] threat, treating it as monolithic,” whereas the administration did not feel “it should be simplified to the extent of an ideology.” He also added, “I wasn’t an expert of the Soviet Union but I did recognize that a degree of paranoia existed in certain parts of our Republic.”10

The administration’s frustration with the politicization of military leaders came to head with its dismissal of General Walker from the 24th Infantry Division in Germany in 1961 after it emerged that he had distributed John Birch Society material during the election campaign and that he had questioned the patriotism of then-Senator Kennedy, of Harry Truman and of Eleanor Roosevelt in an effort to influence his troops’ voting.11 General Walker, who was a World War II and Korean War hero, later became a figurehead for radical right groups in the South and made a bid for the governorship of his home state, Texas.12 Walker’s allies in Congress, who included Senator Strom Thurmond, accused Assistant Secretary of Defense Arthur Sylvester of being “taken in” by anti-military propaganda and used the confrontation to resurrect a complaint that dated back to the 1950s when he had lobbied for a preemptive strike against the Soviets and against containment as a “no win foreign policy.”13 For both Walker and Thurmond, civilian oversight of military officials’ public statements implied a “retreat from victory” as it imposed a conciliatory foreign policy that was inconsistent with their preferred “victory ethos of the military.”14

The administration’s directive and the confrontation with Walker ultimately led to a furor in Congress, which accused the OSD of attempting to “muzzle” the military and which insidiously suggested that Yarmolinsky was a Communist infiltrator.15 McNamara, defending his assistant, insisted to the Chairman of the SASC, Richard Russell, that while the Chiefs had a right to share their frank opinions with Congress “as provided by the National Security Act,” it was the “long-standing policy of the Department [that] military and civilian personnel of the Department should not volunteer pronouncements at variance with established policy.”16 Former Secretary Lovett also stepped into the fray and testified at the hearings, explaining that it was fundamental to the process of national security decision-making in the US system of government that civilian authorities should control foreign policy and that military subordination and obedience to this civilian authority was legally mandated. On the issue of troop indoctrination, he added that the absentee ballot had been granted to troops stationed abroad on the sole precondition that base commanders should not influence their vote.17

Although these issues, in retrospect, may seem minor or inconsequential, in 1962 they contributed greatly to the souring of relations between McNamara, the services and key members of Congress. Writing in 1963, a columnist noted how quickly McNamara had fallen from grace. Formerly “the greatest thing to come off the Ford assembly line since the Model T,” he was now decried as a “dictator and a bum.”18 McNamara persevered despite the many headlines, one of which read “Kennedy Fights the Generals,” and in spite of the climate of mutual distrust if not outright hostility.19

Outside the OSD, Kennedy made a move that further undermined the authority of the Chiefs. In April 1961, the administration acted on a CIA-led plan that it had inherited from the previous administration to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs with a group of CIA-trained paramilitary groups composed of Cuban exiles. Unfortunately, the operation ended in a debacle, which left the administration humiliated only months after coming to office. Publicly, President Kennedy took full responsibility for the failure and saw his public ratings paradoxically shoot up as a result. In private, he was furious at the Chiefs and the CIA for their lack of candor and their flawed advice.

As a result, he commissioned Maxwell Taylor to produce a report to identify failures and lessons. Taylor had an impressive background, notably as Superintendent of West Point and as Eisenhower’s Army Chief of Staff. During the Eisenhower years, he had openly criticized the New Look strategy and published two best-selling books that had contributed to the intellectual foundations of flexible response. He was widely respected as a soldier-scholar and eventually became very close to both Kennedy brothers.20 In his final report, Taylor was especially scathing about the Chiefs and their failures to highlight predictable operational weaknesses of the invasion plan. When Kennedy subsequently kept him on as his personal Military Representative, the Chiefs quietly seethed. The position was unprecedented and effectively went even further in undermining the Chiefs’ advisory role to the President.

In 1962, Taylor was promoted to become the Chairman of the JCS. On one level, this meant that Kennedy and McNamara had an “agent” among the Chiefs. Taylor explained that he informed McNamara that he “would never take a black snake whip to try to drive unanimity between the Chiefs,” but then that “It was amazing how few splits we had. Why? Because they knew that I was very close to McNamara, that I would never bring a paper that the Secretary wouldn’t support. So I had a great advantage versus the Chiefs.”21 However, Taylor was tactfully pushed out as he began to show his “limits.” In the months leading up this “promotion,” Taylor had repeatedly taken hawkish stances on a range of issues, notably in suggesting the introduction of troops to Vietnam, leading to suspicions that, in practice, he really was more of a soldier than a scholar.22

Two offices within the Defense Department were especially concerned with matching defense resources with strategy. These were the Deputy Secretary of Defense’s office, whose incumbent, Roswell Gilpatric, McNamara described as his “alter-ego,” and the Office of International Security Affairs (ISA). A lawyer by training and protégé of former Secretary of Defense Lovett, Gilpatric had a long career in and around the Defense Department, including as Undersecretary of the Air Force and more recently as a member of the Symington Committee. As for ISA, it became a central unit for adapting defense policy to the administration’s new thinking: McNamara described it as “one of the two or three most significant posts in the department.”23

ISA was set up in the fall of 1949 to help administer the Mutual Assistance Program. Although the military aid program remained one of its core functions, during the Eisenhower administration and in a reflection of the United States’ growing international responsibilities, the unit grew and became known as the “little State Department.” It was the principal vehicle through which the department coordinated its policies with other agencies concerned with foreign policy, principally the State Department.24 Among its new and more visible responsibilities, ISA also oversaw NATO affairs.

However, the office really came into its own with the Kennedy administration’s expanded interest in the developing world and with McNamara’s efforts at aligning defense tools to foreign policy. As one Foreign Office report at the time put it: it was “one of the main instruments through which Mr. McNamara has affected his considerable changes in the Pentagon.”25 For McNamara, the Secretary of Defense was “a servant of the foreign policy of the country, and therefore I conceived Dean Rusk as superior to me.”26 This hierarchy was reflected in the budgetary changes with the introduction of PPBS: the President and Secretary of State established missions and objectives that informed military strategy and eventually budgets.27 By definition, this meant that McNamara needed a team within the OSD that could develop security policy independently from military advice. ISA fulfilled this function and became the key unit for the implementation of flexible response and for a very broad set of foreign policy challenges including Vietnam.

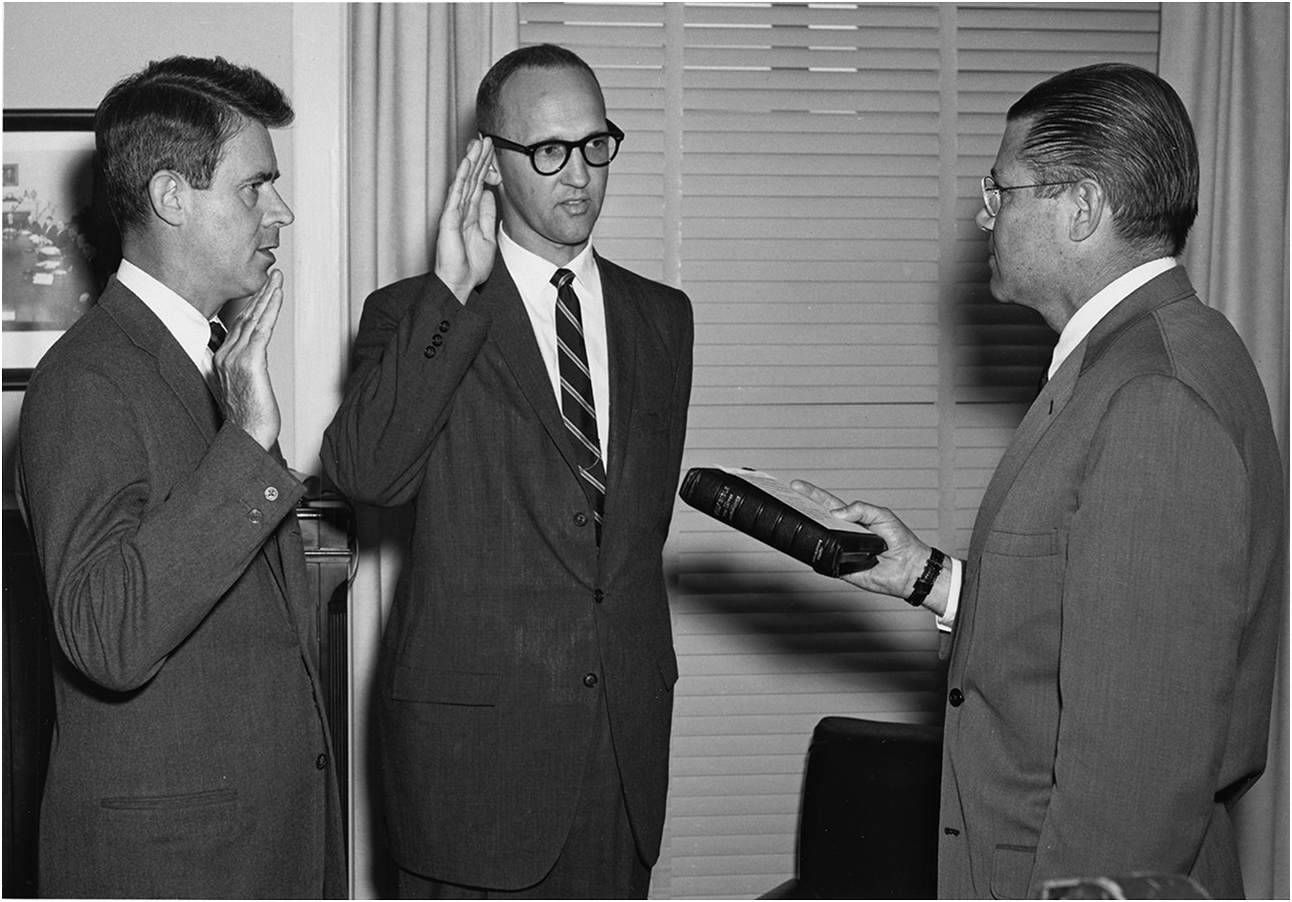

At the same time, ISA’s growing role in coordinating policy did not necessarily mean that it favored “defense answers” to problems or even that it played a greater part in designing policy. McNamara slammed, and eventually removed, the first head of ISA, Paul Nitze, largely because he tried to fill in the policy void that Dean Rusk had left and because he had advocated more aggressive steps during both the 1961 Berlin Crisis and the 1962 Cuba Missile Crisis. When Nitze overstepped his office’s prerogatives, McNamara angrily told him “just keep your sticky fingers out of foreign policy.”28 For McNamara, the head of ISA needed to align with foreign policy objectives, not set the policy himself. McNamara “handpicked” each of its incumbents who were all men he trusted. They included William Bundy, Paul Warnke and John McNaughton; the latter became one of McNamara’s closest friends and a notable skeptic in the later years of US involvement in Vietnam (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Secretary of Defense McNamara (right), swears in Secretary of the Army Cyrus R. Vance (left) and Defense Department General Counsel John T. McNaughton (middle), July 5, 1962. He described his appointees as the “finest group of associates of any Cabinet member, possibly ever” and the two men would become confidants.

Ultimately, the centralization of authority within the Defense Department had important repercussions for the role of the OSD in national security decision-making and in the administration as a whole. McNamara ran a tight ship and had gathered an impressive group of experts, most of whom reflected the Kennedy administration’s ethos. They were “men in the same age bracket as the President, … tough and highly-trained specialists”29 who were impatient and decisive. McNamara described them as the “finest group of associates of any Cabinet member, possibly ever.”30 Collectively, they guaranteed that the Defense Department maintained one stance on all the key issues, however forced the consensus might be.

In the New York Times in 1964, McNamara explained how he managed the potentially unruly defense structure: “It goes without saying, perhaps, that once a decision has been made, we all must close ranks and support it.”31 However authoritarian the process might have been, it meant that McNamara could report to the President with one “defense” position that fit into the President’s worldview. In this, he had a marked advantage over the State Department, which the much gentler Dean Rusk led at the time.

Kennedy may have deliberately chosen a weak Secretary of State hoping to carve out a central role for himself in the articulation of the administration’s foreign policy, much like Eisenhower had done with his Secretary of Defense. However, the result was that, faced with a more improvised national security decision-making style, many junior State Department officials reported directly to the President. Even while this improvised decision-making process guaranteed access for some State Department officials, more often than not it resulted in the Defense Department taking responsibility for many issues “by default, because neither the State Department nor [US]AID seemed to zero in on the problem.”32

Kennedy’s decision to replace existing NSC working groups that had dominated decision-making under the Eisenhower administration with ad hoc interdepartmental task forces, designed to address crises, favored the Defense Department. Defense Department staff, Deputy Secretary Gilpatric and Paul Nitze, led the administration’s first two task forces on Laos and Cuba, respectively.33

Part of the problem was also that the State Department was historically a “talking department” as opposed to the Defense Department, which was an “operating department.”34 Arthur Schlesinger wrote: “Other departments provided quick answers to presidential questions and quick action on presidential orders. It was a constant puzzle to Kennedy that the State Department remained so formless and impenetrable.” The State Department seemed riddled with “intellectual exhaustion” and seemed always to fall short of Kennedy’s ambition to have it act as an “agent of coordination.”35

Moreover, the same junior State Department officials that benefited from direct access to the President complained that because Rusk did not defend them or a “State” position in NSC meetings, McNamara inevitably overpowered them. One of the staff members observed: “So it went by, with Rusk not taking a strong stand and McNamara interrupting anybody less than the President and the Secretary of State so there wasn’t much I could do.”36 The implication was that the Defense Department dominated national security decisions by the sheer force of McNamara’s personality, which contrasted starkly with Dean Rusk’s reserved demeanor. The Director of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) Roger Hilsman, who played an important role in the Vietnam decisions, sarcastically described one NSC meeting where the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) John McCone “got two sentences out and McNamara interrupted him because Man Namara had been in that part of the world only 15 hours before he knew more than the CIA by a long shot.”37

Kennedy’s more informal arrangements tended to favor personal rapport. Here too, McNamara was at an advantage. He enjoyed a special relationship with the President, who often remarked that McNamara was his “most versatile member of Cabinet.”38 Listening to the Kennedy presidential tapes, McNamara is the only official who ever interrupted the President. According to Robert Kennedy, “it was a more formal relationship than some but President Kennedy liked and admired him more than anybody else in the Cabinet,”39 while Jacqueline Kennedy recalled that “the McNamaras” were the only couple, aside from “the Dillons,” that the President interacted with socially and added that the President “loved and admired” him.40

Aside from personal amity, President Kennedy appreciated McNamara’s proven loyalty, a core value in choosing associates for both the Kennedys and McNamara. Kennedy’s associates recall how McNamara fought through Kennedy’s projects as if they were his own: “He’s got his marching order and he doesn’t walk away because he’s being beaten on the head. I’ve never seen a man more willing to take so much abuse, sometimes for a position I know he’s already taken the opposite position for. He continues to be loyal beyond his congressional testimony, even into his most private remarks.”41

The concept of loyalty was central to the way that Kennedy managed his administration and McNamara the OSD. The most loyal members of Kennedy’s administration, men such as McNamara, were rewarded with the power of proximity to the President in a sometimes unstructured decision-making process (see Figure 2.2). Loyalty provided organizational coherence and order by guaranteeing a unity of purpose: subordinates applied the directives of their bosses. Recalling the atmosphere at the OSD, Daniel Ellsberg described a “feudal concept of loyalty to the king,” that loyalty was “the number one value.” As McNamara himself suggested, it was a particular kind of loyalty: to the boss rather than to the country.42

Figure 2.2 President John F. Kennedy with Secretary of Defense McNamara outside the Oval Office, October 29, 1962.

Each of McNamara’s policy decisions, and particularly those on Vietnam, needs to be understood in the context of his loyalty to the President and not to his office per se and with his definition of the job of Secretary of Defense in mind. McNamara came to the issue of Vietnam, as he did with all issues, with his biases and blind spots, and with his particular understanding of what the role of Secretary of Defense should be. He changed the Defense Department to match the foreign policy direction that the White House laid out and, in keeping with this, moved toward capabilities for counterinsurgency that played a central role in Vietnam during the Kennedy years.

The net result of McNamara’s policy reforms was that, whereas in 1947, the OSD had been limited to coordinating war plans that were produced in each military service, by 1962, the latter had little input on setting strategy in Vietnam or indeed elsewhere. On the budgetary side, the evolution of the OSD’s role historically had been more erratic, while McNamara’s changes were sweeping and enduring. Since 1947, each successive administration had tried to reinforce civilian control of the budgetary process but with only limited success. The 1958 Defense Reorganization Act asked that the OSD “provide more effective, efficient, and economical administration in the Department of Defense,” and McNamara’s immediate successor, Thomas Gates, defined the outlines of an action plan to this end but without substantially acting on it. With McNamara, this too changed.

McNamara’s predecessors were divided between those who were great economizers, such as Eisenhower’s Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson, who put a primacy on fiscal balance, and those who were “defense-firsters,” such as Truman’s last Secretary, Robert Lovett. In 1961, the incumbent President seemed to fall into the latter group: a central theme of his campaign was that Eisenhower had been dangerously concerned with budgetary balance and thus had allowed a “missile gap” to emerge. Moreover, Kennedy reached out to figurehead “big spenders” in the transition, including Symington and Lovett. He tried to bring Lovett into his administration, offering him either his old job or the Secretary of the Treasury post. However, despite the campaign rhetoric and after Lovett turned down the offers, Kennedy filled both positions with Republicans with more conservative attitudes toward the budget.

As Secretary of Defense, McNamara erred on the side of fiscal prudence and developed a reputation for cost-cutting while he recognized, and at times was alarmed with, the pressures to increase spending on defense projects. The pressures were those that had troubled his immediate predecessors, particularly the services’ defense of their budgets and the congressional leaders’ defense of the services and related jobs in their constituencies. At the same time, with a Congress that dragged its feet on most of the administration’s proposed social programs, McNamara and his colleagues recognized the Keynesian potential of the defense budget and pushed through programs, including the civil defense program, that were as much defense projects as they were about upgrading civilian infrastructure.

Ultimately, McNamara’s core “revolution” on implementing civilian control came to the budgetary process, principally in the shape of systems analysis and PPBS. More than the changes to the reporting lines, these changes became a “substitute for unification of the services and the establishment of a single chief of staff” as they forced the services to produce one overarching budget in keeping with national, shared objectives.43 In addition to the analytic rigor they brought to defining the United States’ goals and aligning resources to those ends, they gave McNamara a privileged overview of the department’s economic impact.

Having been given a free hand to hire the team he desired, McNamara brought in his “whiz kids,” primarily analysts from RAND or other security intellectuals, many of whom had a background in economics, to radically overhaul what they saw as an archaic way of organizing the defense budget. They brought a culture of “rational” thought from RAND and the techniques of systems analysis to existing “irrational planning and budgeting practices.”44

The key office for this agenda was the Comptroller. McNamara chose Charles Hitch. Their first meeting “was reported to be ‘love at first sight.’”45 Before coming into government, Hitch had been the head of the Economics Division at RAND and, together with his colleague Roland McKean, had written the “bible of defense economics,”46 Economics of Defense in the Nuclear Age, which spelled out PPBS, his main innovation in office.47 As his Deputy Alain Enthoven later wrote in an obituary for his mentor, “‘Hitchcraft,’ as it was affectionately known, was the most important advance in public administration of our time.”48

While Hitch was known as the “father of defense economics” and of PPBS in its precise form, similar ideas circulated already both in and outside the US Defense Department. At its core, systems analysis was a method of reducing otherwise political and fungible issues to numerical values that allowed a more “objective” assessment of costs and benefits. This approach chimed with McNamara’s work at HBS, the Army Air Force and Ford where he encouraged the use of statistics to improve policy. Ultimately, Hitch’s ideas reflected a bipartisan consensus that the defense budget, as it drew on a growing share of federal resources, should become more transparent and accountable.

First applied to the 1963 budget, PPBS was essentially a planning tool to define national security objectives and to break these objectives into missions and functional areas (through so-called DPMs). Before, the budget had been allocated on a yearly basis and according to service-specific inputs, for instance, personnel or logistics costs. Under the new system, services budgets were allocated according to their ability to achieve the stated objectives in the most cost-efficient way and were calculated over a five-year period in order to capture the total cost of programs, which invariably spread over many years. When McNamara presented his first budget in the spring of 1962, newspapers recognized the transformative nature of the changes and noted that McNamara had “virtually abolished separate budgets and it was he and not the Joint Chiefs of Staff who explained the new military strategy to Congress.”49

By placing ultimate budgetary authority in the hands of civilian agencies of the Defense Department, namely with the Comptroller, rather than the services, PPBS further eroded the services’ power. PPBS required that each service submit its budget through its Chief rather than its Secretary, which de facto stripped the Service Secretary positions of their power and made them organizationally redundant. As a result, Service Secretary positions became “parking lot” positions for Kennedy’s friends. Secretary of the Navy Paul B. Fay, for instance, was mostly remembered for his time on the golf course.50 When he left, he was replaced with Paul Nitze as a way of short-circuiting Nitze’s long-term ambition to replace Gilpatric as Deputy Secretary of Defense.51

In principle, under PPBS, the budget was open-ended and not bound by the set budgetary ceilings that had capped the budgets of McNamara’s predecessors. In practice, the reforms were designed with a cost-cutting agenda at their core and forced civilian authorities, mainly the President, to be more modest in setting strategies and national ambitions. Enthoven and Smith explained, “A frequently stated but mistaken view of setting strategy and force requirements is that the process is one of starting at the top with broad national objectives and then successively deriving a strategy, force requirements, and a budget. It is mistaken because costs must be considered from the very outset in choosing strategies and objectives.”52

The whole system of forward planning and budgeting was designed to align the Defense Department’s resources and planning more effectively with the rest of government. As a result, the budgetary process was coordinated with the Bureau of the Budget, whose director, not surprisingly, praised the first budget. He noted that it made “enormous advances in concept, clarity and logic” that were “literally revolutionary.” He added, “there is much more to be done, as Secretary McNamara knows better than any of us, but the improvement in the degree of rationality which can be applied to military planning and budgeting is already tremendous.”53

However, as they were implemented further, the steps to rationalize and reduce defense expenditures ruffled many feathers, not least in the services. The services were the principal target of cuts, and the reforms challenged their authority most. The State Department was also often unsupportive. Looking back on this period, Paul Nitze asserted that if McNamara’s “belief in forward planning, in particular time phased logistic and financial planning was close to absolute,” it also sometimes lacked “tactical and broad judgmental vision.”54

For the services and the Defense Department, cost-cutting first came in the shape of the 1962 Defense Department Cost Reduction Program, which included standardizing logistics and procurement and especially military base closures.55 To support his effort, McNamara created a set of dedicated offices within the OSD, including the Defense Supply Agency, which was responsible for procurement, and the Defense Contract Audit Agency. Base closures were especially complicated politically because many of the senators in the SASC, which was ultimately responsible for allocating the defense budget, were also from states that hosted major bases and defense-related operations, and so, if nothing else, base closures involved job losses for their constituents.

McNamara’s relations with the congressional Armed Services Committees were just as ambivalent on budgetary issues as they were on defense policy issues. On the one hand, Richard Russell, had pushed through the Defense Reorganization Act of 1958 and thus welcomed the reforms that McNamara promised to implement. On the other, like many on his committee, he was prone to adding wasteful projects to the defense budget for political, rather than operational, reasons.

In an oral history, McNamara described some of the tensions that blighted his congressional relationships. He explained that the members of the Armed Services Committees in the House and Senate at the time “were not representative of the people” and “were disproportionately Southerners,” where many military installations were located. He added, “Southerners, as we all know, have had a different view of the military requirements of the nation and the national security of the nation, and how it might best be achieved, than have the rest of the people.” Moreover, the committees were “dominated by reserve officers,” who were “spokesmen for military interests as opposed to the national interest. They saw things through the narrow parochial views of the military.” He ended on one of the main points of contention in his congressional relations, namely that they got in the way of his cost-reduction programs: “There was at that time a situation difficult for many people to imagine today: a desire in the Congress to spend far more than the Secretary of Defense and the President wished to spend on defense.”56

McNamara’s remarks raised many issues but especially Eisenhower’s concern about the “iron triangle” between industry, the military and congressional leaders, or what the President had called the “military-industrial complex.” Ironically, Eisenhower’s remarks were in part a reaction to Kennedy’s and Symington’s accusations during the campaign that he had been “weak on defense”57 and reflected not just on the failures of congressional oversight but also on the novelty of a major military establishment in the US experience. In later years, McNamara’s colleagues, including Yarmolinsky, echoed Eisenhower’s views and complained about the “military-industrial-labor-congressional complex.” Yarmolinsky wrote that Congress “since World War II” had “to a considerable extent abdicated” its oversight role of the armed services in part because of the growing complexity of military issues and programs but also because of “self-interest in major contracts” which produced “wasteful development and procurement procedures.”58

Nevertheless, from McNamara’s vantage point, PPBS coupled with the sheer strength of his character could be enough to short-circuit congressional manipulations that would undermine an efficient allocation of federal resources to clear defense purposes. He claimed not to “share Eisenhower’s concerns” and suggested that the “influences” could affect national security policy only “to the extent that the President and/or Secretary of Defense wants to be influenced.”59 In office, he did not shy away from following through with the logic of PPBS and overruling the services’ military judgment on costly procurement decisions for new weapon systems, precisely the kind of program their allies in Congress tended to defend.

However, this led to more acrimonious arguments between the OSD and the Senate and services, most famously over the so-called Tactical Fighter Experimental (TFX) fighter jet. On McNamara’s insistence, the Air Force and Navy were meant to jointly procure and operate the jet. Despite reservations from both services, the OSD pushed the program in an effort to pool resources, encourage inter-service cooperation and, in so doing, cut costs and apply the logic of PPBS more effecitvely. The OSD also chose General Dynamics over Boeing to build the jet, a choice that overruled the services’ recommendations. The whole program became even more controversial as cost overruns dented McNamara’s effort to showcase its cost-efficiency logic and when the Senate openly challenged McNamara’s competence by initiating an investigation into his decision.

The TFX incident was emblematic of relations between McNamara and the services and their allies in the Senate. It highlighted their resistance to McNamara’s reforms. Within the OSD it crystallized a confrontational attitude toward the Chiefs and the Senate and further contributed to the deterioration of trust and goodwill between the two. Writing about the incident to President Kennedy’s Special Counsel Theodore Sorensen, Gilpatric was angry:

The only feasible method of handling this situation as far as the Defense Department is concerned is to shift the basis for the debate. Every effort must be made, of course, to establish the facts. But this will not do the job that must be done. Somehow, the debate must be shifted from a question of merits (which the public is incapable of deciding) to a question of whether the military, in conjunction with large weapons systems producers, will be able to dominate the responsible officials of our Government who, under our Constitution, are supposed to be in charge … What we are really dealing with in the TFX investigation is the spectacle of a large corporation, backed by Air Force Generals, using the investigatory powers of Congress to intimidate civilian officials just because it lost out on a contract.60

Gilpatric’s letter betrays both the extent to which the OSD, by 1963, was in a confrontational relationship with the services and their friends in the Congress and the extent to which McNamara and his colleagues saw themselves as serving the public interest in spite of, if not against, them.

The battle lines in this confrontation were actually between the executive, through the President’s advisors, and the military and legislative branches of government. In the short term, the confrontation hinged on the latter’s resistance to any cuts in the defense budget. In the longer term, it reflected a deeper rift over McNamara’s attempts to break through their entrenched interests in the status quo and, more broadly, his efforts to move foreign and defense policy-making into civilian and specifically the President’s hands.

While the Armed Services Committees were relatively spendthrift, the same was not true across Congress, especially after 1962 when Kennedy announced his intention to pass a personal and corporate tax cut to kick-start the ailing economy. In the wake of the Berlin Crisis in 1961, Kennedy had planned on proposing a tax increase to match increases in defense spending, but his economic advisors, including Sorensen and Walter Heller, the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, convinced him otherwise. By the summer of 1962, when Kennedy finally settled on the tax cut, he met with almost immediate resistance from Republicans in the House and conservative Democrats in the Senate who wanted to force the administration to match the proposed tax cuts with cuts to federal expenditures.61

The administration’s decision to push for a tax cut and increases in defense spending rather than spend directly on social programs, as Kennedy’s more Keynesian advisors would have preferred, hinged on issues of political feasibility. Kennedy concluded that it was “probably easier, given the mood of Congress and the country, to obtain the necessary economic stimulus through tax reduction than through expenditure increases.”62 Similarly, given the relative invulnerability of the defense budget to cuts, the Kennedy administration concluded that “spending for national security, with its remarkable sanctity from attack by pressure groups, including business[, should take] the place of massive public works.”63

Whereas Eisenhower had added $7 billion to federal spending between 1953 and 1961, Kennedy added $17 billion in three years. Three-quarters was allocated to defense,64 but the Defense Department’s funds were also used for social purposes. In addition to creating jobs, the ill-fated civil defense program morphed into a civilian infrastructure project and McNamara spearheaded civil rights issues in the Defense Department specifically to compensate for the lack of congressional action.65 McNamara also used the department’s clout over industry to intervene in the domestic economy. For instance, when in 1961 steel companies flouted the administration’s suggested price guidelines that were designed to stem inflation, McNamara threatened to change the department’s steel providers, forcing them to back down. Overall, Kennedy’s liberal critics failed to appreciate the way the defense budget was used, albeit as a second-best option, to influence the domestic economy and to push social spending through a resistant Congress.

At the same time, Kennedy’s liberal critics were correct in their suspicion that he was more fiscally conservative than they would have liked. Even before his decision to pass the tax cut, Kennedy sought to balance the budget. In fact, the CEA remembered his “bombshell” just after the inauguration when he agreed with leaders of the Democratic Party in both houses to balance his budget as soon as feasible. He would have achieved a balanced budget as early as FY63 were it not for weak economic indicators in 1962.66

Moreover, he chose Republicans to fill two of the most important positions for federal spending, namely Treasury and Defense. C. Douglas Dillon, with his background in finance at his father’s investment bank, Dillon, Read & Co. where the late James Forrestal had also begun his career, and McNamara were both nominal Republicans disposed to balanced budgets. The Council of Economic Advisers, which was filled with Keynesian economists, complained about Dillon’s influence on the President.67 Although Dillon later explained that in Kennedy’s view the Treasury and Defense positions should be apolitical, he also described himself as Kennedy’s “Chief Financial Officer” and accepted that he usually had the last word on most economic issues.68

In addition, Kennedy gave both Dillon and McNamara operational control of his attempts to limit federal spending. In an effort to reduce expenditures across the board and on defense in particular, Kennedy charged Dillon with a government-wide cost-cutting drive. Dillon’s principal ally in this campaign was McNamara, who enthusiastically supported the agenda against both the State Department and the advice of the services. As one of National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy’s deputies, Carl Kaysen, observed at the time, McNamara used “the pressures Dillon … generated as a means for pushing through various reorganizations that he had in mind in any event.”69

McNamara enthusiastically jumped on Dillon’s bandwagon for a number of reasons but especially because Defense Department expenditures had increased exponentially since the end of World War II and were at the heart of expanding federal expenditures. One of the President’s notes on the budget and debt from January 1963 put it simply: in response to “what causes the budget deficit?” it answered, “first, the cost of national security.”70 According to official estimates, by 1963 the defense budget represented approximately 50 percent the federal budget,71 but national security expenditures generally, including space, raised that number to over 70 percent.72 In other words, if the administration was going to cut federal expenditures and especially expenditures abroad, the first and most obvious place to begin was the Defense Department.

Kennedy had campaigned on a platform that suggested that he would overturn Eisenhower’s fiscal conservatism, with respect to both the federal budget and the defense budget in particular. However, much to the chagrin of his more liberal advisors, he was far more fiscally conservative than they had anticipated and chose Republicans for both the Treasury and Defense positions. Even if defense expenditures increased in absolute terms in the short term, McNamara’s reforms were geared toward economies in the longer term. To a large extent, his professional reputation at the OSD was built on his abilities as a cost-cutter.

McNamara sought to align Defense Department resources to civilian objectives and strategies, but this was also true in the economic sense. As envisaged in the Defense Reorganization Act, McNamara’s major reforms, including PPBS, were aimed at matching the department’s resources in the most cost-efficient way possible and with domestic, economic concerns in mind. At the same time, McNamara confronted entrenched interests in the status quo, including from the services and Congress, which made defense spending easier to access. As a result, the administration drew on the defense budget to support programs that were only tangentially relevant to it, for instance, on civilian infrastructure projects and eventually in Vietnam.

The two conflicting types of pressures played a part in McNamara’s policies for Vietnam. On the one hand, the ready availability of resources propelled McNamara and his department into a leading role on Vietnam. On the other, Kennedy’s, Dillon’s and McNamara’s fiscal conservatism, as well as McNamara’s concerns about the costs associated with Vietnam, explain why he favored a more modest commitment.