1.1 Introduction

The importance of foreign direct investment (FDI) has rapidly increased in the world economy since the 1970s (Figure 1.1), reflecting its role in neoliberal approaches to economic development (Reference HarveyHarvey, 2005a; Reference BohleBohle, 2006; Reference GereffiGereffi, 2013). Since the 1960s, FDI-based development strategies have become increasingly important in less developed countries, where FDI levels varied and fluctuated during the twentieth century (Reference TwomeyTwomey, 2000; Reference AmsdenAmsden, 2001; Reference KohliKohli, 2004; Reference Dussel Peters, Weiss and TribeDussel Peters, 2016). During the same period, similar strategies became popular in less developed regions of more developed countries, as we will see in Chapter 2 (Reference Amin, Bradley, Howells, Tomaney and GentleAmin et al., 1994; Reference MacKinnon and PhelpsMacKinnon and Phelps, 2001a). Since the 1990s, FDI played an increasingly prominent role in the economic development of Eastern Europe (Reference PavlínekPavlínek, 2004; Reference DrahokoupilDrahokoupil, 2009), China (Reference Chen, Garnaut, Song and FangChen, 2018) and in other less developed countries (Reference AkyüzAkyüz, 2017), where FDI-based strategies gradually replaced the import substitution strategies of economic development (Reference BrutonBruton, 1998; Reference RodrikRodrik, 2011), in which FDI played a limited role (Reference Humphrey, Oeter, Humphrey, Lecler and SalernoHumphrey and Oeter, 2000; Reference Narula and DriffieldNarula and Driffield, 2012; Reference NarulaNarula, 2018).

Consequently, the average global annual FDI inflows were sixty-three times higher during the decade of 2013–2022 (USD1.51 trillion) than in 1970–1979 (USD24 billion). The average annual FDI inflows to less developed countries grew 115 times (USD730 billion versus USD6.4 billion), while average inflows to more developed countries increased forty-one times (USD748 billion versus USD18 billion). As a result, the share of less developed countries making up total FDI inflows increased from the average of 26 percent during 1970–1979 to 49 percent during 2013–2021. FDI inward stock grew sixty-four times for the world as a whole, seventy-two times for more developed countries and fifty times for less developed countries between 1980 and 2022 (Figure 1.2) (UNCTAD, 2020). The 2020s are projected to be a decade of far-reaching changes in the world economy that will strongly affect global FDI flows with potentially significant development implications for less developed countries (UNCTAD, 2020; Reference ZhanZhan, 2021). Uneven distribution and geographic concentration are the enduring structural features of FDI (Table 1.1) that contribute to global uneven development.

| USD billion | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Developed economies | 29,093 | 65.7 |

| Europe | 15,604 | 35.3 |

| North America | 11,902 | 26.9 |

| Other developed economies | 1,587 | 3.6 |

| Developing economies | 15,160 | 34.3 |

| Africa | 1,053 | 2.4 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 2,580 | 5.8 |

| Asia | 11,495 | 26.0 |

| East Asia | 6,125 | 13.8 |

| Southeast Asia | 3,564 | 8.1 |

| South Asia | 650 | 1.5 |

| West Asia | 939 | 2.1 |

| Central Asia | 216 | 0.5 |

| Oceania | 32 | 0.1 |

| World | 44,253 | 100.0 |

Note: Totals exclude the financial centers in the Caribbean, Belgium/Luxembourg, Iraq and the Netherlands Antilles. Other developed economies include Australia, Bermuda, Israel, Japan and New Zealand.

The significantly increased role of FDI in the world economy underlines the importance of analyzing and understanding the effects of FDI for host economies and its potential contribution to uneven development at various geographic scales, including in less developed countries. It is particularly compelling due to the fact that “the attraction of FDI constitutes a central component of the development strategies of most developing and emerging economies” (Reference Jordaan, Douw and QiangJordaan et al., 2020: 2), while, at the same time, “FDI is perhaps one of the most ambiguous and least understood concepts in international economics” (Reference AkyüzAkyüz, 2017: 169) and “determining exactly how FDI affects development has proved remarkably elusive” (Reference Moran, Graham and BlomströmMoran et al., 2005: back cover).

The goal of this chapter is to review research on the development effects of FDI in less developed countries (what the world-systems approach labels as global periphery and semiperiphery).Footnote 1 I argue two main points. First, the empirical evidence points strongly towards very uneven and limited development effects of FDI in less developed countries. Second, mainstream and heterodox perspectives come to contrasting conclusions about the potential developmental effects of FDI in less developed countries and regions.

1.2 FDI in Less Developed Countries

I start with a brief overview of the history of FDI in less developed countries. Historically, FDI flows and stocks have been much smaller in less developed countries than in more developed countries (Figure 1.1) (Reference TwomeyTwomey, 2000) and there has been a great variation in the importance of FDI across less developed countries because of the high concentration of FDI in particular countries and macro regions (Table 1.1) (UNCTAD, 2023).

In Latin America, FDI played an important role in economic development from the beginning of the twentieth century, with Brazil recording the largest FDI stock among less developed countries by World War II (WWII) (Reference Kuczynski, Kuczynski and WilliamsonKuczynski, 2003; Reference SchneiderSchneider, 2013). In East and Southeast Asia, Japan heavily invested in its colonies before WWII, with the largest FDI stocks in Korea and Taiwan (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 2001). In Africa, FDI concentrated in extractive industries but was extremely low during the colonial period, with the exception of South Africa (e.g., Reference TwomeyTwomey, 2000; Reference KohliKohli, 2004). Overall, the value and importance of FDI in less developed countries declined in the first half of the twentieth century because of world wars and the Great Depression. The decline continued following WWII due to the nationalization of extractive industries during decolonization and anti-FDI policies in many less developed countries. For example, foreign investment was eliminated in key manufacturing industries in Asia after WWII (Reference TwomeyTwomey, 2000; Reference AmsdenAmsden, 2001; UNCTAD, 2007).

In the 1960s, FDI increased in Latin America (Reference ThomasThomas, 2011; Reference Dussel Peters, Weiss and TribeDussel Peters, 2016) but the political uncertainty in the wake of decolonization discouraged FDI in Asia (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 2001). In Africa, FDI was low and concentrated in the extractive industry and commodity exports after independence (Reference KohliKohli, 2004). FDI inflows in less developed countries more than doubled in the 1970s, more than tripled in the 1980s, grew six times in the 1990s, doubled in the 2000s and increased by only 10 percent in the 2010s (UNCTAD, 2023) (Figure 1.1). FDI stocks in less developed countries grew by 60 percent in the 1980s, tripled in the 1990s and again in the 2000s, and almost doubled in the 2010s (UNCTAD, 2023) (Figure 1.2). The efficiency-seeking FDI, especially access to cheap labor and other assets, is now the most important reason for FDI in less developed countries (Reference Yamin, Nixson, Weiss and TribeYamin and Nixson, 2016), although large national and regional differences exist (UNCTAD, 2023).

In Asia, despite the highest FDI stock in less developed countries (Table 1.1), FDI played a limited role in the rapid development of Japan (Reference Paprzycki and FukaoPaprzycki and Fukao, 2008) and once-peripheral Taiwan (Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu, 2003), South Korea (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 1989) and most recently China (Reference Lee, Gao and LiLee et al., 2017). Instead, the growth and development in these countries depended on domestic firms, both private and state-owned, and strong industrial policies that actively supported their growth. Large domestic firms were then able to globalize through outward FDI (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 2001; Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu, 2003; Reference FarrellFarrell, 2008; Reference Lee, Heo and KimLee et al., 2014; Reference Lee, Gao and Li2017; Reference YeungYeung, 2016; Reference Taylor and ZajontzTaylor and Zajontz, 2020; Reference Jo, Jeong and KimJo et al., 2023). The economic success of these countries thus primarily depended on the development of the strong and globally competitive domestic sector rather than FDI.

FDI stock has been low in Africa compared to other world regions (Table 1.1) despite its growth from USD32 billion in 1980 to USD1,053 billion in 2022 amid an increase in FDI inflows from USD926 million in 1970 and USD2.8 billion in 1990 to USD44.9 billion in 2022. The growth in FDI was mainly driven by the rising global demand for natural resources. However, Africa’s share of global FDI inflows decreased from 7.1 percent in 1970 to 3.4 percent in 2022 and its share of global inward FDI stock dropped from 6.4 percent in 1980 to 2.4 percent in 2022 (UNCTAD, 2023). FDI has been heavily concentrated in extractive industries with limited effects on the broader economy and economic growth (Reference MorrisseyMorrissey, 2012; Reference Ndikumana and SarrNdikumana and Sarr, 2019; Reference MunyiMunyi, 2020) and it fueled capital flight during the 1970–2015 period (Reference Ndikumana and SarrNdikumana and Sarr, 2019). FDI did not have any significant effect on manufacturing during the 1980–2009 period (Reference Gui-Diby and RenardGui-Diby and Renard, 2015) and it crowded out domestic investment in the 1990s (Reference Agosin and MachadoAgosin and Machado, 2005). The share of manufacturing of total FDI inflows declined from 46 percent in 2010 to 25 percent in 2017 (Reference MunyiMunyi, 2020) and the future prospects of manufacturing development in Africa remain bleak (Reference Gelb, Ramachandran, Meyer, Wadhwa and NavisGelb et al., 2020). Countries with weak industrial and FDI policies, such as Nigeria, failed to encourage the development of modern large-scale manufacturing despite relatively large FDI inflows and the strong FDI presence (Reference KohliKohli, 2004). A recent rapid rise in Chinese FDI in resource extraction and infrastructure projects follows a familiar pattern of profit extraction and limited economic benefits for Africa (Reference Taylor and ZajontzTaylor and Zajontz, 2020), which is also the case for increasing FDI in tourism (Reference MurphyMurphy, 2019) and agriculture (Reference Allan, Keulertz, Sojamo and WarnerAllan et al., 2013).

In other less developed world regions, such as Latin America, Eastern Europe, China and Southeast Asia, foreign firms developed modern manufacturing in selected industries (e.g., the automotive and electronic industries), which, however, remained mostly isolated from host economies and did not lead to the growth of the domestic-owned internationally competitive manufacturing. This has been the case of efficiency-seeking FDI in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, and resource-seeking FDI in Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru since the mid-1990s (Reference WionczekWionczek, 1986; Reference Gallagher and ZarskyGallagher and Zarsky, 2007; Reference SchneiderSchneider, 2013; Reference Dussel Peters, Weiss and TribeDussel Peters, 2016). In Latin America as a whole, FDI crowded out domestic investment in manufacturing between 1971 and 2000 (Reference Agosin and MachadoAgosin and Machado, 2005), resulting in the negative effect of manufacturing FDI on economic growth (Reference Nunnenkamp and SpatzNunnenkamp and Spatz, 2003).

As in Mexico, the growth of manufacturing in Eastern Europe since the 1990s has been driven by peripheral integration into macro-regional production networks through efficiency-seeking FDI (e.g., Reference PavlínekPavlínek, 2017a). FDI inflows into manufacturing led to large increases in output and exports, created hundreds of thousands of jobs and contributed to GDP growth in both Eastern Europe (e.g., Reference PavlínekPavlínek, 2020) and Mexico (Reference South and KimSouth and Kim, 2019). In Mexico, however, despite large FDI inflows the average annual growth in GDP per capita was lower than in many Latin American and Asian countries between 1980 and 2012 (Reference Dussel Peters, Weiss and TribeDussel Peters, 2016).

The industrial development strategy of many countries in Latin America and Eastern Europe has increasingly relied on attracting manufacturing FDI but without a strategic industrial policy that would encourage the simultaneous development of strong, globally competitive domestic firms (Reference WionczekWionczek, 1986; Reference Gallagher and ZarskyGallagher and Zarsky, 2007; Reference Contreras, Carrillo and AlonsoContreras et al., 2012; Reference PavlínekPavlínek, 2016; Reference Pavlínek2017a; Reference Pavlínek2018; Reference Yülek, Lee, Kim and ParkYülek et al., 2020). As FDI crowded out domestic firms of most dynamic industries (Reference SchneiderSchneider, 2017; Reference PavlínekPavlínek, 2020), the majority of domestic firms are small, possess low capabilities, are concentrated in lower-skill and lower-technology industries, and are often locked in dependent and captive trade relations with larger foreign firms. As a result, they have been unable to globalize at all or not to the same extent as domestic firms in the most successful Asian countries (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 2007; Reference PavlínekPavlínek, 2020). It has been argued that this over-dependence on FDI for the industrial development in less developed countries without a more balanced growth of foreign-controlled and domestic sectors is unlikely to lead to a successful long-term economic development (e.g., Reference Zhao, Wong, Wong and JiangZhao et al., 2020).

Since the 1990s, China has been the largest recipient of FDI in less developed countries. Between 1990 and 2022, China attracted USD2.79 trillion (USD4.66 trillion including Hong Kong) and accounted for 20 percent (34 percent including Hong Kong) of total FDI inflows into less developed countries. By 2022, China’s inward FDI stock stood at USD3.8 trillion (USD5.9 trillion including Hong Kong), accounting for 25 percent (39 percent including Hong Kong) of less developed countries’ total (UNCTAD, 2023). Inspired by the experience of other East Asian countries, China has followed a very careful and highly regulated FDI policy of gradual FDI liberalization, which was driven by national industrial development priorities and a strategic industrial policy (Reference Chen, Garnaut, Song and FangChen, 2018). While it is generally assumed that FDI effects in China have been positive and strongly contributed to the rapid economic growth, no unequivocal conclusion can be made. For example, the removal of publication bias showed the actual effects of FDI to be statistically insignificant and ranging between “small” and “very small,” along with insignificant spillovers at the aggregate level (Reference Gunby, Jin and Robert ReedGunby et al., 2017). However, a different meta-analysis has found statistically significant backward technology spillovers in China (Reference Fan, He and KwanFan et al., 2020).

Overall, the FDI experience across less developed countries has been highly uneven in terms of FDI distribution, national and regional effects of FDI, and government policies toward FDI. After reviewing FDI trends, I will critically assess how the mainstream and heterodox perspectives interpret FDI in less developed countries.

1.3 Mainstream and Heterodox Perspectives of FDI in Less Developed Countries

By its very nature, any theory of international production needs to employ the spatial perspective. It might therefore be surprising that the modern theory of international production was not originally developed by economic geographers but by economists in the 1960s and 1970s, who applied the spatial perspective to conceptualize the rapidly growing FDI in the world economy. Much has been written about Reference HymerHymer’s (1976 [1960]) seminal explanation of FDI based on the theory of the firm and industrial organization (e.g., Reference Dunning and RugmanDunning and Rugman, 1985; Reference PitelisPitelis, 2006). Much has also been said about Hymer’s recognition of the close relationship between FDI and uneven development, what he called the law on uneven development, in which the combination of vertical division of labor within transnational corporations (TNCs) with location strategies of TNCs tends to perpetuate spatial inequalities between core and peripheral regions (Reference Hymer and BhagwatiHymer, 1972). In 1970, Reference HymerHymer (1970: 448) envisioned the future consequences of growing TNCs and FDI in the world economy: “The coming age of multinational corporations should represent a great step forward in the efficiency with which the world uses its economic resources, but it will create grave social and political problems and will be very uneven in exploiting and distributing the benefits of modern science and technology.”

Reference VernonVernon (1966) introduced an explicitly locational dynamic to thinking about FDI by linking the internationalization of production to the product life cycle and recognizing different locational needs for the manufacturing of new, maturing and standardized products. As the product ages, the relative importance of the different factors of production changes and, consequently, an ideal location for its manufacturing shifts from developed to developing countries. Drawing on Hymer, Vernon and other theories of international trade and production, such as Reference CavesCaves (1971) and Reference Buckley and CassonBuckley and Casson (1976), Reference Dunning, Hesselborn, Ohlin and WijkmanDunning (1977) proposed what he originally called an “eclectic theory of international involvement” and later the “OLI (ownership-location-internalization) paradigm” in order to explain the rapidly growing role of FDI in the world economy (Reference DunningDunning, 2000).

These modern approaches to FDI provide the basic conceptual framework within which the contemporary understanding of FDI and international activities of TNCs has developed in mainstream economics, international business and, to a large extent, also in economic geography (e.g., Reference Iammarino and McCannIammarino and McCann, 2013). If we concentrate on FDI in less developed countries, we can recognize two main perspectives: the mainstream and heterodox (e.g., Reference Jo, Chester and D’IppolitiJo et al., 2018). I also recognize the dependency/world-systems perspective on FDI as a distinct approach within heterodox approaches. These perspectives are summarized in Sections 1.3.1 and 1.3.2 and in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Different perspectives on the role of FDI in less developed countries

1.3.1 The Mainstream Perspective

Mainstream economic approaches, which are closely associated with neoclassical economics and neoliberal approaches to economic development (Reference HarveyHarvey, 2005a; Reference GereffiGereffi, 2018), view FDI as the engine of development and economic growth in less developed countries (e.g., Reference HirschmanHirschman, 1958; UN, 1992; Reference Klein, Aaron and HadjimichaelKlein et al., 2001; OECD, 2002; Reference JensenJensen, 2003; Reference Basu and GuarigliaBasu and Guariglia, 2007; WBG, 2019). FDI is considered “a powerful force of convergence across countries” (Reference Brucal, Javorcik and LoveBrucal et al., 2019: 1) (Table 1.2). FDI-related inefficiencies and suboptimal performance in host countries are attributed to governmental intervention and regulation (e.g., Reference MoranMoran, 1999).

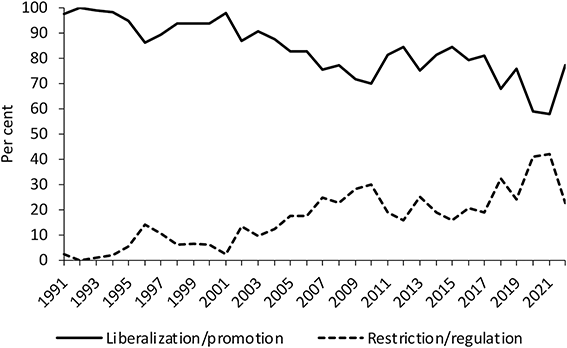

Along with the emphasis on free markets and the minimal role of the government for achieving the most efficient distribution and operation of FDI, this unambiguously positive view of FDI has been incorporated into the global ideology for economic development since the mid-1970s (Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu, 2003; Reference Gallagher and ZarskyGallagher and Zarsky, 2007; Reference Yamin, Nixson, Weiss and TribeYamin and Nixson, 2016; Reference ChuChu, 2017; Reference SornarajahSornarajah, 2017). Accordingly, the policy advice from international institutions such as the World Bank to less developed countries has been to liberalize FDI (e.g., Reference Klein, Aaron and HadjimichaelKlein et al., 2001) because of its “transformative potential for development” (WBG, 2019: 1). Although some less developed countries began to liberalize FDI in the mid-1980s (Reference NunnenkampNunnenkamp, 2004), the trend of FDI liberalization has been the strongest since the 1990s (UNCTAD, 2013; 2023) (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Regulatory changes in national FDI policies, 1991–2022

Note: Data for 1991–1999 were calculated by using a slightly different methodology and are not thus fully compatible with the 2000–2019 data.

This mainstream positive assessment of FDI has persisted despite the fact that depending on the data, research design and estimation method used, econometric analyses have often arrived at contrasting conclusions about the effects of FDI in host economies (Reference Blomström and KokkoBlomström and Kokko, 2001; UNCTAD, 2001; Reference Dunning and LundanDunning and Lundan, 2008; Reference Meyer and SinaniMeyer and Sinani, 2009), including mixed empirical evidence of the benefits of FDI for economic growth (Reference MencingerMencinger, 2003; Reference MahutgaCurwin and Mahutga, 2014; Reference WernerBermejo Carbonell and Werner, 2018) and for the behavior and performance of domestic firms in the form of technology spillovers (Reference Görg and StroblGörg and Strobl, 2001; Reference Görg and GreenawayGörg and Greenaway, 2004; Reference Iršová and HavránekIršová and Havránek, 2013).

The mainstream approach to FDI tends ignore the empirical evidence of no or negative FDI effects on economic growth in less developed countries (e.g., Reference Nunnenkamp and SpatzNunnenkamp and Spatz, 2003; Reference Carkovic, Levine, Moran, Graham and BlomströmCarkovic and Levine, 2005; Reference SarkarSarkar, 2007; Reference Alfaro, Chanda, Kalemli-Ozcan and SayekAlfaro et al., 2010; Reference Alguacil, Cuadros and OrtsAlguacil et al., 2011; Reference MahutgaCurwin and Mahutga, 2014; Reference Alvarado, Iñiguez and PonceAlvarado et al., 2017; Reference WernerBermejo Carbonell and Werner, 2018), including negative FDI spillovers (e.g., Reference Farole, Winkler, Farole and WinklerFarole and Winkler, 2014). Not surprisingly, policymakers often assume that FDI contributes to economic growth in host economies (UN, 1992; Reference Harding and JavorcikHarding and Javorcik, 2011; Reference Hallin and LindHallin and Lind, 2012), although is not always the case (Reference MencingerMencinger, 2003; Reference MahutgaCurwin and Mahutga, 2014) as FDI effects strongly depend on the concrete context of different countries and regions (Reference Blomström and KokkoBlomström and Kokko, 2001; Reference Görg and GreenawayGörg and Greenaway, 2004). Indeed, Reference Alfaro, Chanda, Kalemli-Ozcan and SayekAlfaro et al. (2010: 254) argued as follows.

Although there is a widespread belief among policymakers that FDI generates positive productivity externalities for host countries, the empirical evidence fails to confirm this belief. In the particular case of developing countries, both the micro and macro empirical literatures consistently find either no effect of FDI on the productivity of the host country firms and/or aggregate growth or negative effects.

Similarly, Reference AkyüzAkyüz (2017: 198) maintained, “there can be no generalization regarding the impact of FDI on capital formation, technological progress, economic growth, and structural change. Indeed there is no conclusive evidence to support the myth that FDI makes a major contribution to growth.”

The mainstream perspective recognizes the importance of FDI spillovers to host economies for the long-term economic development in less developed countries (e.g., Reference Narula and BellakNarula and Bellak, 2009). However, spillovers are far from being automatic as they depend on a number of factors, such as the existence of linkages between foreign subsidiaries and host country domestic firms, the absorptive capacity of domestic firms, a favorable institutional environment, mode of entry of foreign firms, nature of the targeted industry, nature of TNC operations, and time since the investment (UNCTAD, 2001; Reference Scott-KennelScott-Kennel, 2007; Reference Saliola and ZanfeiSaliola and Zanfei, 2009; Reference SantangeloSantangelo, 2009; Reference DickenDicken, 2015). In addition to overstating reported spillover estimates, a meta-analysis of publications on FDI spillovers in less developed countries revealed a substantial publication bias in favor of publishing positive and significant spillovers and not publishing the findings of insignificant and negative spillovers (Reference DemenaDemena, 2015).

The policy advice of FDI liberalization in less developed countries has been at odds with the past FDI policies of more developed countries that systematically discriminated against FDI through the range of national policy instruments (Reference ChangChang, 2004; Reference WadeWade, 1990). In the absence of international regulation of FDI, bilateral investment treaties have been the main instrument governing FDI relationships since 1959 (Reference SeidSeid, 2018 [2002]) with 2,584 bilateral investment treaties (including treaties with investment provisions) in force in 2022 out of 3,265 bilateral investment treaties and treaties with investment provisions signed (UNCTAD, 2023). The main function of bilateral investment treaties has been to protect FDI from being nationalized and expropriated in less developed countries (UNCTAD, 2015). At the same time, trade-related investment measures have been used by more developed countries to limit the regulation of FDI by less developed countries (Reference DickenDicken, 2015).

The World Bank and other FDI-promoting global institutions failed to promote industrial policies in less developed countries that played an important role in the successful cases of FDI-based development, such as Ireland and Singapore (Reference ThomasThomas, 2011; Reference MorrisseyMorrissey, 2012). The promotion of FDI in less developed countries also tends to ignore the post-WWII experience of countries, such as Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, that achieved rapid economic growth and development without large FDI inflows (e.g., Reference AmsdenAmsden, 1989; Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu, 2003; Reference Paprzycki and FukaoPaprzycki and Fukao, 2008; Reference FischerFischer, 2015). Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu (2003: 161) argued: “In liberal mainstream theories the heroes of economic development are foreign investors and market forces. But these theories overlook the fact that in the fastest-growing latecomers, high-tech industries tend to be dominated by nationally owned firms, and governments continue vigorously to promote such firms as well as ‘new’ high-tech market segments.”

These geographically varied and uneven experiences with FDI in less developed countries are, however, considered by heterodox perspectives, to which I will now turn.

1.3.2 Heterodox Perspectives

Drawing on the empirical historical evidence and on institutional and evolutionary economics, the heterodox literature argues that on its own, FDI does not automatically lead to successful long-term economic development in less developed countries. It also challenges the emphasis of economic orthodoxy on the decisive role of the free market in promoting development through FDI. Instead, the heterodox literature emphasizes a strong relationship between the strength and quality of state industrial policies and successful economic development that mostly relies on domestic firms (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 1989; Reference Amsden2001; Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu, 2003; Reference KohliKohli, 2004; Reference SchneiderSchneider, 2013; Reference Lee, Heo and KimLee et al., 2014; Reference AkyüzAkyüz, 2017). Countries typified by a weak and ineffective state capacity, industrial policies and policies toward foreign capital and domestic firms (e.g., in Latin America and Africa) have been much less economically successful than countries with a strong and efficient state capacity, industrial policies, policies towards foreign capital and strong support of domestic firms (e.g., in East and Southeast Asia) (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 1989; Reference Amsden2001; Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu, 2003; Reference KohliKohli, 2004; Reference MorrisseyMorrissey, 2012; Reference SchneiderSchneider, 2013; Reference YeungYeung, 2013; Reference Yeung2016; Reference WadeWade, 2018).

Heterodox economists have for decades been highly critical of the long-term effects of FDI in less developed countries (e.g., Reference SingerSinger, 1950; Reference BaranBaran, 1957). For example, Frank argued in 1967 (Reference Frank, Chew and Lauderdale2010 [1967]: 43): “with few exceptions, writers from the developed countries have failed to question, much less to analyze, the supposed benefits of this foreign investment to underdeveloped countries.” Heterodox scholars have emphasized the negative indirect long-term effects of resource-oriented FDI in less developed countries as it led to the development of foreign-controlled enclaves and the infrastructure that predominantly geared to the needs of foreign capital while being isolated from host economies. By disproportionally benefiting source countries of FDI through their access to primary commodities and the transfer of profits, FDI has ultimately slowed down the development of modern industrial capitalism in less developed countries, while intensifying their foreign exploitation (Reference BaranBaran, 1957; Reference AminAmin, 1976; Reference Gallagher and ZarskyGallagher and Zarsky, 2007; Reference Arias, Atienza and CademartoriArias et al., 2014; Reference NarulaNarula, 2018).

This criticism of the long-term effects of FDI in less developed countries, particularly in Latin America and Africa, became strongly articulated in the dependency perspective (e.g., Reference SunkelSunkel, 1972; Reference Chase-DunnChase-Dunn, 1975; Reference FischerFischer, 2015; Reference TaylorTaylor, 2016), which acknowledged the short-term positive effects of FDI in less developed countries, such as economic growth and job creation, but maintained that the long-term growth effects of FDI were neutral or negative (Reference Bornschier and Chase-DunnBornschier and Chase-Dunn, 1985; Reference KentorKentor, 1998; Reference MahutgaCurwin and Mahutga, 2014). It also pointed out that profit repatriation from less developed countries far exceeded FDI inflows, resulting in a net capital flow from the periphery to the core of the world economy (Reference AminAmin, 1976; Reference Frank, Chew and LauderdaleFrank, 2010 [1967]; Reference SornarajahSornarajah, 2017; Reference Taylor and ZajontzTaylor and Zajontz, 2020). Less developed countries that are more dependent on foreign capital have grown more slowly than those less dependent (Reference KentorKentor, 1998), which has been supported by the experience of East Asia (Reference AmsdenAmsden, 1989; Reference Amsden2001; Reference Amsden and ChuAmsden and Chu, 2003). Nevertheless, the dependency theory has been unable to fully account for “FDI success stories” of once less developed countries, such as Ireland, Hong Kong and Singapore, although Ireland and Singapore used strategic industrial policies to channel FDI into what they considered strategic sectors of their economies (Reference ChangChang, 2008; Reference ThomasThomas, 2011).

1.4 Conclusion

This chapter has considered the contribution of FDI to the development in less developed countries in the context of the sharply increased importance of FDI in the world economy. The brief historical review of FDI in less developed countries has revealed FDI’s very uneven distribution and performance in less developed countries. It then reviewed the mainstream and heterodox perspectives on FDI and its development potential in less developed countries.

We may conclude that both the mainstream and heterodox perspectives tend to overlook the empirical evidence that does not necessarily support their one-size-fits-all explanations of FDI effects in less developed countries. Different conclusions of the mainstream and heterodox approaches to FDI in less developed countries (Table 1.2), at least partially, stem from their emphasis on different time horizons of FDI. While the mainstream perspective tends to stress potentially positive short- to medium-term effects of FDI in host economies, heterodox approaches emphasize long-term effects. At the same time, the mainstream and dependency and world-systems perspectives tend to ignore the spatial variation of these effects across different countries and regions in less developed countries. Heterodox scholars recognize the potentially positive effects of FDI in less developed countries. However, they also maintain that different conditions in different countries lead to different FDI outcomes and stress the importance of strong and well-targeted industrial and FDI policies of host country governments for reaping potential FDI benefits, while minimizing its potentially negative effects (e.g., Reference ChangChang, 2008; Reference MorrisseyMorrissey, 2012).

Despite strong arguments presented by heterodox perspectives and despite the lack of strong empirical evidence that would unequivocally support FDI-centered development strategies in less developed countries advocated by the mainstream perspective, FDI-related public debates and policy recommendations have predominantly been dominated by various perspectives from mainstream economics. Compared to mainstream economics, the insights of heterodox economists have had a limited impact on economic policy in most countries. The only exception is the global value chains (GVCs) approach, which was originally developed from the world-systems perspective (Reference Hopkins and WallersteinHopkins and Wallerstein, 1977; Reference Hopkins and Wallerstein1986) and global commodity chains approach (Reference Gereffi and KorzeniewiczGereffi and Korzeniewicz, 1994), and has become increasingly accepted in mainstream analyses of economic development (e.g., Reference Cattaneo, Gereffi and StaritzCattaneo et al., 2010; UNCTAD, 2013; AfDB et al., 2014).

Many governments around the world tend to view FDI positively for several reasons. They value the potential immediate (short-run) direct effects of FDI, such as job creation, income generation, infusion of capital, and contribution to a positive trade balance (Reference DickenDicken, 2015). Governments also tend to assume the long-term indirect positive effects of FDI on economic growth and development (Reference Hallin and LindHallin and Lind, 2012), while often downplaying or ignoring evidence of the negative effects of FDI (Reference BellakBellak, 2004), such as the transfer of profits abroad through transfer pricing and other mechanisms of rent extraction (Reference Dischinger, Knoll and RiedelDischinger et al., 2014a) or negative spillovers from FDI in the host economy (Reference Blomström and KokkoBlomström and Kokko, 1998; Reference De Backer and SleuwaegenDe Backer and Sleuwaegen, 2003; Reference Görg and GreenawayGörg and Greenaway, 2004; Reference Meyer and SinaniMeyer and Sinani, 2009; Reference Oetzel and DohOetzel and Doh, 2009).

The optimistic view of FDI might partially stem from the failure to recognize differences between the effects of FDI in more developed countries and less developed countries. In the eyes of many policymakers, FDI thus potentially represents a relatively easy and quick policy solution to persistent economic problems in less developed countries, such as high unemployment rates and slow growth. FDI might therefore be politically preferable to long-term policies with uncertain outcomes, such as an institutional reform (Reference Fagerberg and SrholecFagerberg and Srholec, 2008; Reference Rodríguez-PoseRodríguez-Pose, 2013; Reference Ketterer and Rodríguez-PoseKetterer and Rodríguez-Pose, 2018) or investment in a high-quality education. In turn, this positive perception of FDI has translated into generous state support for FDI in many countries (Reference MeyerMeyer, 2004; Reference SmeetsSmeets, 2008; Reference Harding and JavorcikHarding and Javorcik, 2011; Reference ThomasThomas, 2011; Reference Narula and DriffieldNarula and Driffield, 2012; UNCTAD, 2012).

In the next chapter, which focuses on FDI in less developed (peripheral) regions of more developed countries, I argue that in order to better understand the potential development effects of FDI in peripheral regions, we need to recognize that FDI effects differ between more developed (core) and peripheral regions.