This chapter examines in detail the cases of failed amendments in two countries, Italy and Chile. On the basis of Chapter 2, these failures were primarily due to the rigid rules of constitutional amendments. However, a closer examination will reveal more institutional reasons. This chapter is divided into three parts. Section 4.1 describes the core of the constitutions of both countries. Italy has two alternative amendment procedures, while Chile has three. We will calculate the core of each one of these countries as specific examples of how the arguments made in Chapter 2 can be applied in single-country analyses. In addition, because the institutions of Chile are quite unusual (in a comparative sense), we will describe the historical conditions of their adoption. Section 4.2 describes the history of the failed amendments. Here, there are similarities (both amendments failed) and differences (in Italy, the result was accepted; in Chile, a series of failed attempts to replace the constitution itself followed). Section 4.3 will deal with another similarity between the two countries, focusing on how they both used referendums in their constitutional procedures. The reason for this was that they were expecting an easy approval of the proposed amendments (Italy) or constitutions (two different attempts at a new constitution in Chile), as we argued in Chapter 2. However, unlike the argument in that chapter, in both countries the referendums led to a NO result (actually in Chile this happened twice!). Because of this, we will explain in Section 4.3 what was mistaken in Chapter 2’s analysis regarding the argument that referendums have no core which, consequently, makes it easier to make amendments (or replacements) through this procedure. We will use examples from EU referendums in order to have a broader understanding of how this institution works.

4.1 Calculating the Core of Two Constitutions

4.1.1 Italy

According to the Italian Constitution (Part II, Title VI, Section II, Article 138), amendments require the following:

Laws amending the Constitution and other constitutional laws shall be adopted by each House after two successive debates at intervals of not less than three months, and shall be approved by an absolute majority of the members of each House in the second voting. Said laws are then submitted to a popular referendum when, within three months of their publication, such request is made by one-fifth of the members of a House or five hundred thousand voters or five Regional Councils. The law submitted to referendum shall not be promulgated if not approved by a majority of valid votes. A referendum shall not be held if the law has been approved in the second voting by each of the Houses by a majority of two-thirds of the members.

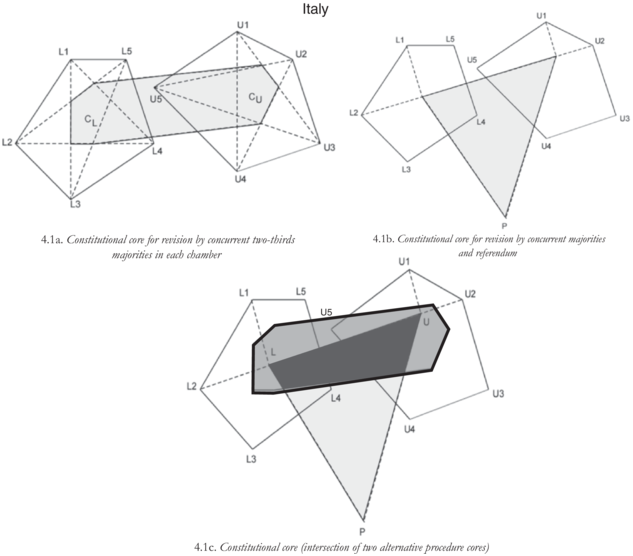

Figure 4.1 helps us visualize the situation. The set of provisions of Article 138 specifies two alternative procedures for constitutional revision: revisions may occur via a two-thirds majority in both chambers of the legislature or by simple majorities plus a referendum.Footnote 1

Figure 4.1a demonstrates the core of the first procedure for revision, which is a two-thirds majority in both chambers. I represent each chamber with five members (L1–5 and U1–5) and look for agreement from four of the five members in each chamber, as four out of five most closely approximates the two-thirds majority required to pass constitutional reforms under the first procedure. Under this arrangement, the pentagon CL represents the core of the lower chamber: any point outside this pentagon can be defeated by its projection on the pentagon since four out of the five members of the lower chamber would prefer this solution. Similarly, the pentagon CU depicts the core of the upper chamber. The bicameral constitutional core, in this case, is comprised not only of both CL and CU but also of the area between them (the shaded area in Figure 4.1a).Footnote 2

Figure 4.1b captures the second possible procedure for constitutional revision: concurrent simple majorities in both chambers plus a referendum. In this case, the bicameral core by simple majority is located along the line segment L2U2. Indeed, this line is a “bicameral median” – that is, it has a majority of members of both houses on either side of it. It follows that there is a majority in both houses that would prefer, over any point outside this line, its projection on the line itself. The bicameral core, however, does not extend beyond point L2 and U2: Anything outside the solid line in the figure does not command a majority in one of the chambers. Therefore, the bicameral core is the solid line between L2 and U2. In order to calculate the whole constitutional core, including the referendum requirement, one must factor in the voters (Point P) and expand the core. The shaded triangle depicts that addition.Footnote 3

The core of the Italian Constitution exists at the intersection of the cores of the two procedures delineated in Figure 4.1a and Figure 4.1b. Indeed, any point that belongs to only one of the procedural cores can be changed by using the alternative procedure. This intersection is represented by the darkly shaded area in Figure 4.1c. It cannot be assessed a priori which one of the two procedures is easier to use. Indeed, this depends not only on the institutional rules but also on the actual preferences of the actors. However, the system does behave in predictable ways. For example, if the preferences of the people are much closer to both houses than Figure 4.1 indicates, then it is easier to make a constitutional revision with a referendum than it would be with two-thirds of both chambers. This seems to be the case for the amendment we will discuss in Section 4.2.1 because it prescribed the reduction of the powers of the senate and consequently would make it difficult to get a two-thirds majority of votes in the senate. Similarly, if the two houses drift apart, the segment LU in Figure 4.1 will become longer, and the core will expand. Indeed, all three cores in Figures 4.1a, 4.1b, and 4.1c will become larger, and constitutional revision will become more difficult. This would be the case under the electoral system for the senate created by the proposed constitutional reforms. The proposed electoral law would have the senate elected indirectly through regional councils. This reform would result in a significantly different composition of the senate from the national assembly. That would generate more disagreements between the house and the senate, but the senate would have lost political significance except on constitutional issues.

4.1.2 Chile

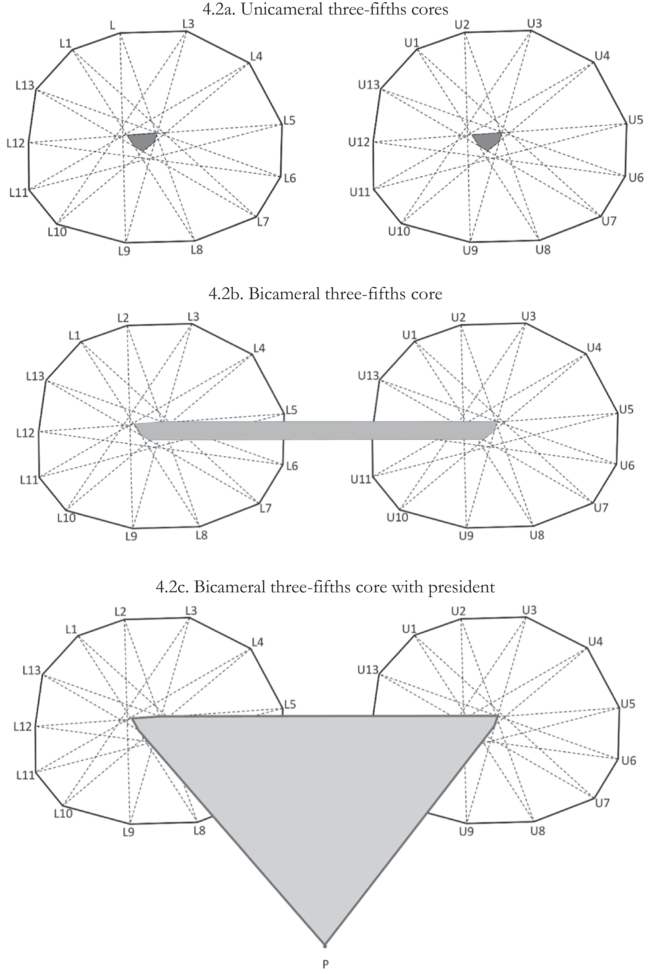

The Chilean constitution provides for two different paths to constitutional amendment. The first, requiring cooperation between the legislature and the executive, is detailed in Article 127: “The Bill of reform will require for its approval in each Chamber the confirming vote of three-fifths of the Deputies and Senators in office.”Footnote 4

Article 128 adds an additional requirement to the three-fifths majority: “The Bill which both Chambers approve will be transmitted to the President of the Republic… If the President of the Republic totally rejects a Bill of reform approved by both Chambers and it insists on its totality by two-thirds of the members in office of each Chamber, the President must promulgate that Bill.” Figure 4.2 depicts the core resulting from this revision procedure, as discussed in Chapter 2. Figure 4.2a presents these cores in two thirteen-member legislatures, as created by the three-fifths majority requirement. Next, Figure 4.2b presents the joint bicameral core with a three-fifths majority in each chamber. Since revision requires approval by both chambers concurrently, the core must grow to include all points located between the two legislative cores. Indeed, any point in this area cannot be defeated by the required three-fifths bicameral majorities: it cannot be moved up or down because such a movement does not get endorsed by three-fifths, and it cannot be moved left or right because one of the two chambers will disagree. Thus, in Figure 4.2b, the core stretches between the cores depicted in Figure 4.2a. Finally, I incorporate the president into the core. Here, because the president’s approval is required alongside both chambers, the core must expand, this time to include all points between the region in Figure 4.2b and the president’s ideal point, P. This generates the triangle-shaped core found in Figure 4.2c.

Figure 4.2 Constitutional core of Chile, three-fifths, and president

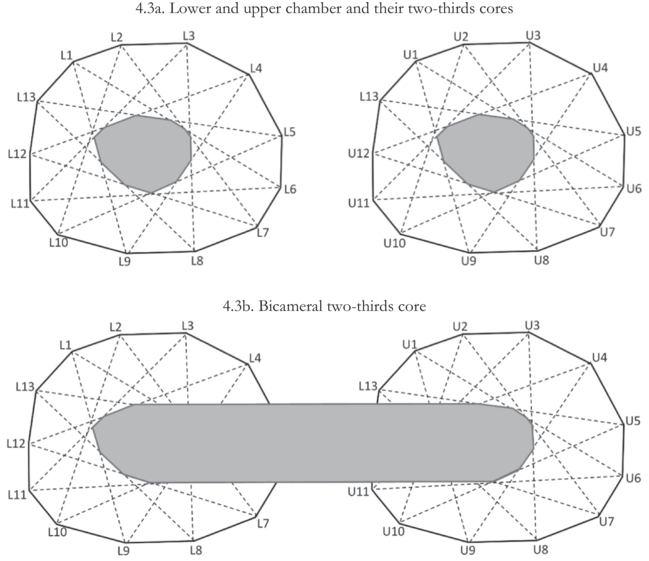

However, according to Article 128, if there is disagreement between Congress and the president, the president’s opinion can be overruled by a two-thirds majority of both chambers. Chile’s constitution, therefore, allows for an alternate route to constitutional revision that bypasses the president. Indeed, if the president decides against proposed revisions, the legislature can overrule their decision via concurrent two-thirds majorities in each chamber of the legislature. Figure 4.3a presents the two-thirds core of each chamber (created using the same procedure presented in Figure 4.2), and Figure 4.3b depicts the bicameral core of this alternative procedure. Figure 4.3b connects the cores of each chamber (just like in Figure 4.2) to account for the concurrent majority requirement. This shaded region is the core of the two-thirds concurrent majority alternative for constitutional revision.

Figure 4.3 Constitutional core of Chile and two-thirds without president

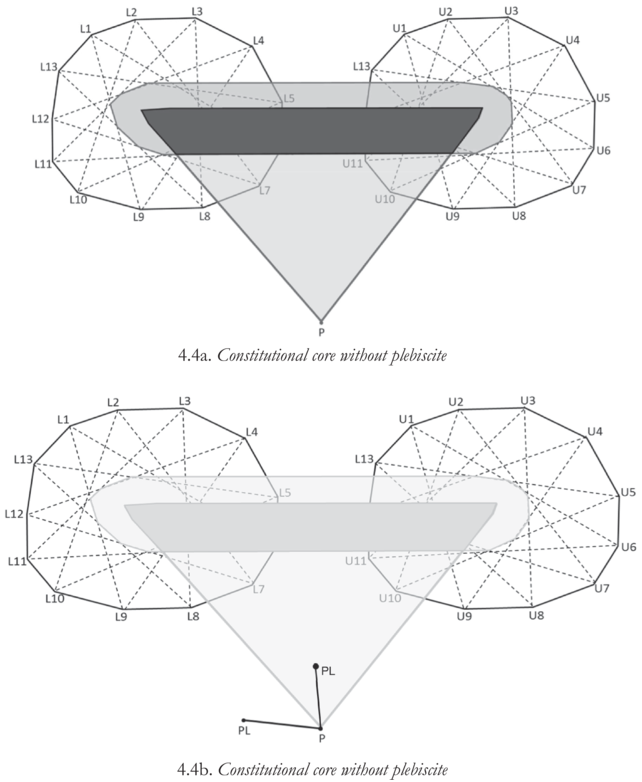

As explained in Chapter 2, the final constitutional core is the intersection of these two cores (just like in Italy). Figure 4.4a thus depicts this final, smaller core.

Figure 4.4 Constitutional core of Chile with all alternatives

However, Chile’s constitution introduces an additional wrinkle into its constitution revision process: If the president is overridden, they can overcome the override through a plebiscite. According to Article 129, the “consultation” of the people through “plebiscite” must proceed as follows:

The convocation to [the] plebiscite must be effected within thirty days following that on which both Chambers insist on the Bill approved by them, and it will be ordered by supreme decree which will establish the date of the plebiscitary voting, which shall be held one hundred twenty days from the publication of the decree if that day corresponds to a Sunday. If this should not be so, it will be held on the Sunday immediately following. If the President has not convoked a plebiscite within such period of time, the Bill approved by the Congress will be promulgated.

The decree of convocation will contain, as it may correspond, the Bill approved by the Plenary Congress and totally vetoed by the President of the Republic, or the questions of the Bill on which the Congress has insisted. In this latter case, each one of the questions in disagreement must be voted [on] separately in the plebiscite.

If the president opts to put constitutional changes up for popular vote, such a choice drastically alters the constitutional core. Because the plebiscite can override any decision made by the legislature, the previous core becomes irrelevant, and the new core now lies along a straight line connecting the president’s and the public’s ideal points. Figure 4.4b presents the new core, which replaces the old one.

The constitutional provision found in Article 129 is completely unique from a comparative perspective and, therefore, merits additional attention. According to my analysis, the third alternative (plebiscite) seems to overrule the previous two, and, consequently, the actual intersection of all three cores is the empty set. Indeed, given that the intersection of the cores of the first two procedures does not include the president, the intersection of the three cores is empty whether the people are located outside the initial triangular core (three-fifths and the president) in the position PL or inside it in the position PL’. An empty constitutional core implies that there is nothing immune to change inside the Pinochet Constitution. If the president is willing to use the plebiscite specified by Article 129, anything can change, and the agreement between the president and the people will become the new constitution. There is one exception to this rule: If the president and the congress want to modify the status quo in opposite directions, but the status quo is the second-best option for both of them (that is, if each one of them prefers the status quo over the other’s proposal), then the status quo will prevail. Here is the description of this rule according to Article 128: “In the case that the Chambers do not approve all or some of the observations of the President, there shall be no constitutional reform of the points in dispute, unless both Chambers insist by two thirds of their members in exercise on the part of the project approved by them.”Footnote 5

The combination of all these constitutional revision articles provides the following synthesis. For an amendment to be successful, it requires a three-fifths majority in both chambers and the president’s approval (two-thirds for articles in Chapters I, III, VIII, XI, XII, or XV of the constitution). In addition, the president can be overruled by concurrent majorities of two-thirds in both chambers. In case of disagreement between Congress and the president, Congress can either opt for the status quo (by not approving the president’s proposals) or for a confrontation (by overruling by two thirds) – in which case, the president can send his proposal to a referendum. In the case of disagreement without confrontation, there is no modification of the constitution; in the case of confrontation, the plebiscite becomes the president’s nuclear option.

The Chilean Constitution provides the president with extraordinary legislative powers. They can introduce amendatory observations in legislation, and the congress can overrule their amendments only by a two-thirds majority. In comparative perspective, these powers do not exist in other Latin American constitutions except for Uruguay and Ecuador (Tsebelis and Alemán Reference Tsebelis and Alemán2005).

However, in terms of constitutional revisions, there is no other constitution in the world that provides one individual with so much power. The president both controls the question that will be asked and can decide whether to trigger the referendum or not. Consequently, they have complete control of the agenda.

It is surprising that such a provision exists in a democratic constitution and has not been removed after so many years of democratic rule. To understand this peculiarity, we need to explore its genesis in the history of Chile’s constitution and its amendment provision.

4.1.3 History of Chilean Article 129

Chile’s modern constitutional history – and its unique plebiscitary provision for constitutional amendment – began with the 1924 efforts to reform the 1833 constitution. Prior to the 1920s reform efforts, the Chilean government had become mired in a struggle for power between the legislative and executive branches. For years, Chile was regarded as a “parliamentary republic” (Valenzuela Reference Valenzuela1977), but. in response to social and economic challenges, their newly elected president Arturo Alessandri had attempted to wrest power from the legislature. This struggle stalemated the Chilean government (in spite of many urgent challenges facing the country), leading the military to form a junta to demand a resolution to the stalemate. After an internal struggle for control within the military itself, political reform efforts began in earnest in 1925 (Stanton Reference Stanton1997b: 134).

Military officers placed President Alessandri in charge of reforming the constitution. This created institutional tension, however, because the 1833 constitution made it clear that constitutional reforms lay within the purview of the legislature’s powers. In response, President Alessandri assembled a consultative commission by decree, which would be made up largely of democratically elected representatives. The commission was to be made up of two subcommissions: one would be in charge of overseeing the constitutional amendment process (and ensuring its popular legitimacy), and the other would decide on the content of the reforms. The commission met for the first time on April 4, 1925 (Stanton Reference Stanton1997b: 135).

From the time of the commission’s first meeting, Alessandri expressed doubts about its efficacy and usefulness. According to Alessandri, political reform via the constituent assembly was not likely to happen, nor was the result likely to match his own vision for constitutional reform. After all, conservatives had not yet submitted to the idea that the “parliamentary republic” needed to be done away with. In his own words, “[I] had contracted a commitment with the country that it was necessary to fulfill; but, that same public opinion would have to come to realize that it was not possible to be successful and to achieve that which it desired” (Alessandri Reference Alessandri Palma1967: 166). Thus, instead of moving forward with the popularly elected constituent assembly, Alessandri concentrated reform efforts in a subcommittee of the commission, called the “Subcommission of Constitutional Reforms” (Alessandri Reference Alessandri Palma1967: 142).

Unlike the constituent assembly in the consultative commission, the subcommission was filled with politicians and other political operatives – particularly representatives of the major political parties in Chile. Thus, while Alessandri seemingly had greater faith in the efficacy of the subcommission, it was not without its own challenges. In fact, following pro-legislature remarks by one conservative party representative, Alessandri reportedly stormed out of a subcommission meeting and was ready to halt reform talks altogether. However, according to historians, a number of factors contributed to the ability of the subcommission to remain intact. First, military leaders arose early in the process as opponents of any return to the “parliamentary republic.” Figures such as General Mariano Navarrete reminded the subcommission throughout the deliberation process that the military junta itself materialized because of public dissatisfaction with parliamentary predominance. General Navarrete stated that “the Army … is horrified at politics … but nor will it look on with indifference as the slate is wiped clean of the ideals of national purification, … as the ends of the revolutions of the 5th of September and the 23rd of January are forgotten in a return to the political orgy that gave life to those movements” (Ministerio del Interior 1925: 454–455). Constitutional reforms, then, should reflect this public desire to roll back the powers of the legislature. Given that the military junta had organized efforts for constitutional reform in the first place, the presence of military officials at the meetings helped to keep conservative and radical party members at the negotiating table. Additionally, the small size and frequent meetings of the subcommission allowed factions to reach a consensus on difficult issues (Stanton Reference Stanton1997a: 13–17).

While the subcommission provided Alessandri with a more favorable venue through which to enact constitutional reform, the president encountered a problem with his new focus on the subcommission: Unlike the constituent assembly, the subcommission lacked popular legitimacy. In response to this problem, Alessandri announced his intention in a manifesto on May 28, 1925, to subject the subcommission’s proposal to the plebiscite. Such a move was not expected by practically any political actor at the time. Indeed, even Alessandri himself did not seem to indicate that a plebiscite was a possibility when he initially convened the consultation commission. Opponents, too, seemed to doubt whether Alessandri was serious about holding a plebiscite: Rather than actually drafting an alternative proposal for a plebiscite, Alessandri’s opponents instead focused their energy on public messaging about the constitutional reform process.

However, while the plebiscite did not appear as part of Alessandri’s original plan, the arrangement ultimately benefited his view of reform quite well. First and foremost, it was not until July 22, 1925, that Alessandri made it explicit that the constituent assembly would have nothing to do with the constitutional reform efforts – an announcement he made by angrily “declaring” at a sub commission meeting that the constituent assembly “has ended.” Alessandri said, “It is time to finish for once and for all the political comedy, it is time for the President of the Republic to stop being the whipping boy” (Ministerio del Interior 1925). The subcommission subsequently voted in favor of holding a plebiscite. Given that the plebiscite occurred in August, this gave opposition reformers only a month to draft an alternative constitution proposal. Unsurprisingly, their proposal was short and unimpressive in comparison to the subcommission’s. In fact, many reformers advocated for a boycott of the plebiscite altogether rather than submit a hasty proposal (Stanton Reference Stanton1997b: 161). Moreover, because President Alessandri’s administration was in charge of executing the plebiscite, Alessandri could (reportedly) further influence the process via biased language in the plebiscite and even police interference (Vial Reference Vial1987: 548). Taken together, in spite of the low turnout resulting from the aforementioned calls for boycott, the subcommission’s constitution was accepted by a count of 127,483 votes to 5,448 (Bernaschina Reference Bernaschina1956: 49).

Ultimately, the ad hoc and combative nature of Chile’s constitutional reform in 1925 led the system to collapse shortly after in 1927. However, its nonlinear development also resulted in the peculiar plebiscitary provision that remains in Chile’s constitution today. Indeed, because Alessandri resorted to an extra-constitutional means of “legitimizing” his subcommission’s constitutional proposal, the plebiscitary provision found its way into the new constitution retroactively. Pinochet retained the provision in his constitutional revisions in 1980, and the provision persists to the present day.

Be that as it may, it is understandable why any elected president would not even think of using this plebiscitary provision: A constitutional revision with the use of Article 129 would be an official admission of war between president and Congress, and the president (if not impeached) would not be able to make any policy decision for the remainder of their term.Footnote 6

4.2 History of Failed Amendments

Having studied the constitutional core of Italy and Chile, let’s now turn to the history of the political events that revolve around the amendments.

4.2.1 Italy

Italy is a country with “symmetric bicameralism” – that is, perfectly equal powers for the House and Senate. Actually, the constitution does not differentiate between the two chambers and uses the expressions “either chamber” or “both chambers” to refer to them. For much of Italy’s history under the 1947 constitution, the Senate did not restrict the set of feasible outcomes (the win-set of the status quo) because of its ideological makeup per se – after all, it had the same composition as the Camera dei Deputati. Instead, lack of political alteration led to “immobilismo,” or immobility. The electoral reforms in 1993 and 2005 created ambiguous results. On the one hand, alternation in the Italian political system turned Italy into a two-coalition (center-left or center-right) system. On the other hand, in the 2005 electoral reform, the bonus distribution at the national level for the House of Deputies and at the regional level for the Senate increased the ideological distance between the National Assembly and the Senate. The resulting complication was compounded by the intervention of the Constitutional Court, which declared the electoral reforms unconstitutional.

The combination of perfect bicameralism and different composition of the two chambers created (in Lijphart’s [Reference Lijphart2012] terms) a “strong bicameralism” in Italy, which reduced the ability of governments to legislate. The government of Enrico Letta (April 2013–January 2014) followed a strategy of “inclusion” and had ministers from parties of both the Left and the Right, but it still could not overcome the problem of political divisions and create policies. Letta resigned when the Democratic Party led by Matteo Renzi withdrew its support to the government.

Renzi was appointed prime minister of Italy, and because his strategy of policy adoption was impossible under the current institutional structures, he had to modify the structures first. He continued a long-standing discussion about the constitutional amendments necessary to alleviate Italy’s problems and proposed amendments that would reduce the policy impact of the Senate (in his plan, he gave the Senate jurisdiction only on regional issues but preserved the perfect bicameralism on constitutional amendment issues).

Given the content of the amendments (including reduction of the power of the Senate), it is obvious that Renzi could not expect a two-thirds approval by the Senate. Therefore, he had to select the alternative procedure of achieving simple majorities in both chambers and being ratified by a referendum. Still, even this procedure could not be considered an easy task. Renzi had made an agreement with Berlusconi to support his amendment, but the latter changed his opinion in the middle of the process.Footnote 7 The procedure was finally aborted, but not from the most obvious obstacle (the Senate).

In October 2015, the Italian Senate voted 179–10 in favor of the largest constitutional reforms since its ratification in 1947. Amid a boycott by over a hundred senators, the vote approved measures that would drastically weaken bicameralism in Italy, stripping the Italian Senate of its ability to veto most types of legislation. Although it was only one step in the constitutional amendment process, the vote represented a key victory for proponents of the reforms who believed the changes would finally address the legislative gridlock and governmental instability that has long beleaguered Italy’s political system. Prime Minister Renzi said of the successful vote, “You can agree or not with what we’re doing, but we’re doing it: the long season of inconclusive politics is over” (Follain Reference Follain2015). Minister of Reform Maria Elena Boschi took it a step further, calling the reforms a “Copernican revolution” for Italy (Economist 2015).

These assessments would be correct for a successful amendment, but the main hurdle turned out to be the last step of the process. Poll information did not indicate popular support for the referendum, particularly after Berlusconi’s reversal. Renzi, in trying to support the reforms, repeatedly declared, “If I lose the referendum, I will go home” (Ansa 2016). (Actually, he made an even more unambiguous statement about abandoning politics altogether and matters of honor.) As we will see in Section 4.3, these statements undermined his chances rather than help him. On December 4, 2016, the referendum rejected the amendments by a decisive 59.12 percent majority.

4.2.2 Chile

The Chilean constitution was introduced in 1980 under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet and was approved by a referendum which, to say the least, had no democratic credentials. As such, it included a series of undemocratic provisions which were considered unacceptable by parties both of the Left and the Right. As a result, the constitution was amended many times, but the most significant revisions (in 1989 and 2005) involved long-negotiated agreements among the political parties in order to achieve the high thresholds specified by the constitution and described in Section 4.1. When major reforms lacked the support of the Right, they failed to get the required majorities (in 1992, 1994, and 1995).

It is interesting to see how this consensus agreement was achieved. According to Fuentes (Reference Fuentes2006) regarding the 1989 agreement:

The then-opposition leaders saw that they should focus their efforts on ensuring opportunities for future constitutional reform. In this sense, the strategic calculation of the negotiators was not to seek reform of all the negative aspects of the 1980 constitution, but rather simply to try to maximize the opportunities for future efforts at reform. This they did in two ways: by reducing the quorums necessary for introducing reforms and increasing the number of senators in order to reduce the relative strength of the non-elected senators (Andrade Reference Andrade Geywitz1991, Heiss and Navia Reference Heiss and Navia2007). This was clear in April 1989, when the then-Interior Minister Carlos Cáceres presented the reform package that would be put up for the plebiscite once negotiations with the opposition concluded.

The second major amendment enterprise began in 2000 and ended in 2005, covering fifty-eight topics of the constitution (Fuentes Reference Fuentes2015: 111). These involved the following:

Repeal of the institution of designated and life senators, a change in the composition of the National Security Council and a reduction in its powers, restoration of the president of Chile’s power to remove commanders-in-chief of the armed forces and the director of the Carabineros (the uniformed national police force), a modification of the composition of the Constitutional Tribunal, an increase in the powers of the Chamber of Deputies to supervise the executive, a reduction in the presidential term of office from six to four years without consecutive re-election, a reform of the constitutional states of exception in order better to protect rights, and the elimination of special sessions of Congress.

By 2015, the constitution was locked (as described in Section 4.1). It still had a serious congenital defect, but it had been significantly improved compared to the initial document. It is interesting to note that in an academic debate in the political science journal Politica y Gobierno one position supported the preservation of the constitution and incremental changes (Navia Reference Navia2018), one its total replacement (Fuentes Reference Fuentes2018), and a third its replacement with incremental changes (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2018a).

In October 2015, President Michelle Bachelet proposed on television a constitutional reform process that included four phases and would be completed by 2017. It involved popular education first; a second stage of participation controlled by a committee selected by the president herself; a third stage which specified the submission of a constitutional amendment accepted by a two-thirds majority in both chambers (note that she increased the required majority from three-fifths according to the constitution to a higher threshold); and finally a discussion of this amendment by a specific body and the ratification by a referendum (Garcia Reference Garcia2023).

On the basis of the analysis of Section 4.1, this project was doomed to failure. Actually, I had predicted this outcome in writing before the end of Bachelet’s term (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2018c). Bachelet did not even propose an amendment, she was replaced in the middle of this process, and her successor refused to continue it. As Fuentes accurately put it:

In the case of Chile, we need to explain the following paradox: knowing the institutional and political difficulties properly described by Tsebelis, President Bachelet nonetheless sought to replace the Constitution through a totally impracticable path. Despite not having a large enough majority in Congress and despite the massive existing legal barriers, her administration tried the apparent “political suicide” of promising a constitutional change that would not happen. Why?

I agree with Fuentes’ analysis,Footnote 8 but there are other analyses that find Bachelet’s process “useful” (Garcia Reference Garcia2023). In fact, after its failure, a formal constitutional revision succeeded. While Bachelet was aiming at an amendment (although the process she adopted would have led to a multiple-screening constitutional revision), Chile chose a series of formal constitutional revisions this next time. In fact, there were two revisions, and both of them failed. Here, I will summarize these “current events” in order to lead into Section 4.3, which analyzes the mode of failure: the referendum process.

In 2020, the people of Chile decided by a majority of 72 percent in a referendum to replace the Pinochet Constitution. As I said before, despite the multiple revisions, the document has a congenital defect. There was a complicated process with a constituent assembly that required a two-thirds majority for successful proposals, wherein the Left cleared this threshold and ignored the objections of the Right. This process led to one of the most progressive constitutional drafts in the world (Harrison Reference Harrison2022). Others have called it “Utopian Constitutionalism” (Landau and Dixon Reference Landau and Dixon2023). The referendum of September 4, 2022, rejected it by 62 percent. A new process was initiated immediately following the rejection. It also required approval by two-thirds of the constituent assembly, but this time the Right cleared the threshold and created a draft constitution that was more conservative than the Pinochet Constitution (after the amendments).Footnote 9 The referendum of December 17, 2023, rejected this one by 56 percent. At the time of writing this book, we do not know what the next step of the process will be. President Gabriel Boric has announced that he will not repeat the process for a third time.

What we see in this section is that in both Italy and Chile the amendment provisions are stringent but provide alternatives, and, consequently, the actors opt for the less stringent path (which, according to Chapter 2, is the referendum). Renzi was not able to get the two-thirds majority and had to go to a referendum; Bachelet failed even to design her amendments, and the new procedure involved new constitution drafting and a referendum for approval. Technically speaking, the Italian case falls within the constitutional amendment scope of the book, while the Chilean one starts as an amendment and develops as a constitutional replacement. However, they both deal with one or two referendum processes, and they both raise questions about the arguments made on referendums in Chapter 2 where they were presented as procedures without a core, consequently facilitating change. Here, we see amendments failing. Of course, it could still be the case that they were the most likely procedures to succeed, and all the others would have led to more patent failures. Nevertheless, it is a serious problem that we need to address, which will be the subject of the next section. There, I will bring more empirical examples in order to buttress my arguments.

4.3 Why So Many Failed Referendums?

We treated referendums in a separate section in Chapter 2 for two reasons. The first was theoretical: Because they are decided by simple majority, there is no core and, consequently, changes are easier to achieve. In addition, the win-set of the status quo (which was the concept we used for the investigation) is simply larger the bigger the size of the electoral body. The second reason was empirical because referendums are often mentioned or used on constitutional issues, whether they are amendments (like in Italy and Chile) or even replacements (like in Chile).

In our theoretical investigation, a fundamental assumption was the comparison of the amendment with the status quo. Indeed, the one investigative concept was the win-set of the status quo – that is, all the solutions that can defeat it – or the core, which is the set of points that cannot be defeated (that is, any invulnerable status quo). This comparison between the status quo and the amendment is legally guaranteed when the decision is made by a parliament or by a convention (which would adopt parliamentary procedures). As Rasch (Reference Rasch2000: 15) argues, in an overwhelming majority of European countries, the most extreme alternatives are introduced first, which leads to the selection of the most central alternative as the final outcome,Footnote 10 or the status quo is formally voted last and compared with the predominant alternative (like in the US). In both procedures, the winner is included in the win-set of the status quo.

Such a provision is not guaranteed to exist in referendums. It is possible that people prefer to modify or replace the constitution yet vote against the amendment or replacement. This is not necessarily a contradictory set of choices. Assume for one individual Voter I that there are four alternatives: The status quo (SQ), the amendment (A) as proposed, the amendment without some negative points according to his judgment (A-i), and his own ideal choice (Ii). There are three different kinds of voters, all of them having their own ideal constitution (Ii) as their first choice and preferring the amendment without their objections (A-i) over the amendment (A):

(1) The ones with the preferences A < SQ < A-i < Ii

(2) The ones with the preferences A < A-i < SQ < Ii

(3) The ones with the preferences SQ < A < A-i < Ii

The differences among these three types are in respect to their evaluation of the status quo. Type (1) considers the status quo to be better than the amendment, and Type (2) prefers the status quo even after embellishments of the amendment. As a result, these two types will vote NO in a referendum. Type (3) voters would vote YES if they compare SQ and A, but NO if they compare A with A-i or Ii.

Type (3) voters, if asked, would answer YES, that they want to amend (or replace) the constitution. If asked if they approve the amendment, they may reply NO if they compare it with A-i or with Ii. Of course, there is no reason to believe that the different voters would have the same ideas about what these projects (A-i or Ii) would be.

Political parties objecting to the referendum would try to make use of these popular preferences and persuade voters that the proposal includes all the negative points they are afraid of or that it does not include the things they desire. In particular, it is easy to make such arguments when the proposal involves over 50 (if it is an amendment) or 200 (if it is a whole constitution) articles. Voters often declare that they would like to know the content of the alternative but do not have time to read it.

The situation I just described would lead to an outcome like the ones we saw in Italy or in Chile: The people have explicitly asked for or are assumed to approve a replacement or a revision, but when this alternative is presented, it is voted down (in Chile, even twice!). The necessary condition for this development is that voters do not compare the alternative to the status quo but respond to different dilemmas prevailing in their own minds. Is there any evidence that this is the case?

The analytical tradition of “retrospective voting” created by V. O. Key is based exactly on the evaluation of one alternative: the incumbent alone. It is a well-known strategy among political strategists of the challenger to turn elections into a referendum on the incumbent. This way, they will turn all the voters who are dissatisfied with the incumbent in their favor. Further, it is the incumbent’s strategy to bring the challenger’s features into focus. President Biden expressed it most forcefully when journalists asked him about his low approval in the polls, responding, “Don’t compare me to the almighty; compare me to the alternative” (White House 2023).

Other people argue about electoral competitions, claiming that they are not referendums. In all these arguments, referendums (and sometimes elections, too) are assumed to be simple one-issue evaluations. Is this true? In order to answer this question, we have to study the voters in the different referendums we spoke about in this chapter and understand their motives.

There are sparse poll data in Italy about why the Italian voters voted NO in their referendum. At the time of the vote, all political parties (including Berlusconi, who initially supported the amendment) advocated a NO vote. A series of research articles mention post-referendum polls by the Italian National Elections Studies Association, but all of them discuss the data without making a specific reference to how the data can be retrieved. Bergman (Reference Bergman2019: 185) analyzes these data and finds that there are three factors that have a statistically significant impact on the NO vote: EU discontent (positive association), government performance (negative association), and referendum-specific (negative association). He explains that this referendum-specific variable is composed of four variables included in the amendment proposal (reduced number of senators, reduced power of the senate, centralization of infrastructure, and reduced quorum requirements for future referendums) which are analyzed by principal components (Bergman Reference Bergman2019: 182). This is not direct evidence but is corroborated by other articles that claim that the NO in the referendum was a decision against Renzi (I remind the reader that the prime minister had placed a target on him by declaring that he would leave if the amendments were rejected). Di Mauro and Memoli (Reference Di Mauro and Memoli2018) entitle their article “Targeting the Government in the Referendum: The Aborted 2016 Italian Constitutional Reform.” Ceccarini and Bordignon (Reference Ceccarini and Bordignon2017) in “Referendum on Renzi: The 2016 Vote on the Italian Constitutional Revision” summarize their point as follows: “The referendum turned into a vote on Renzi himself.” Other analysts like Negri and Rebessi (Reference Negri and Rebessi2018) go one step further and explain the reversal of Berlusconi’s position, which was fatal for the amendment because of Renzi’s support of Mattarella for president of the republic. All of these analysts argue that the political game and the support for the government were significant factors for the vote, but none of them focus on the reasons that the voters themselves would give.

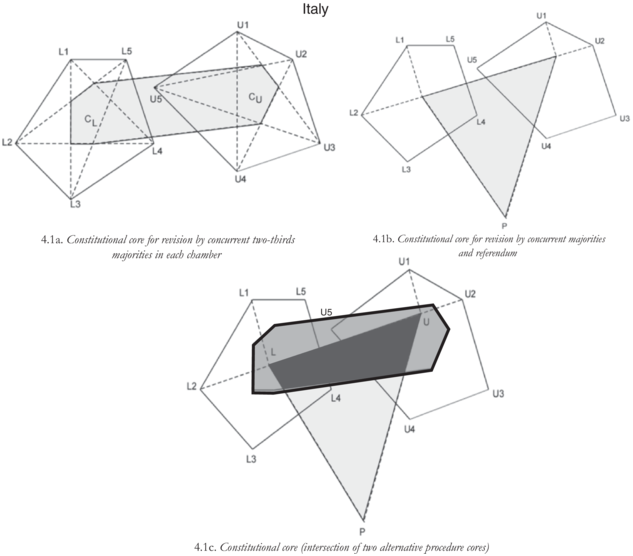

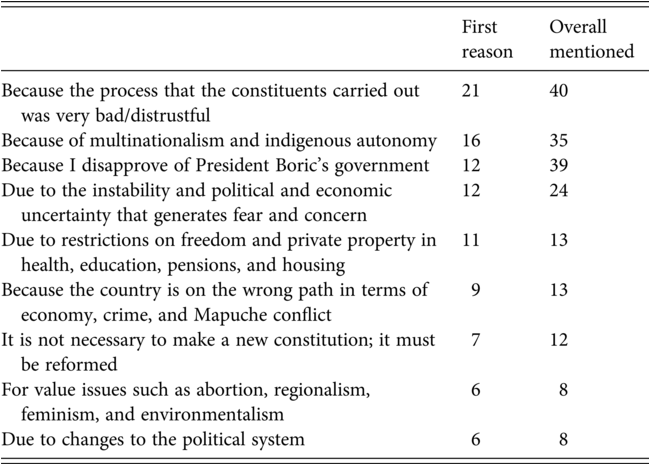

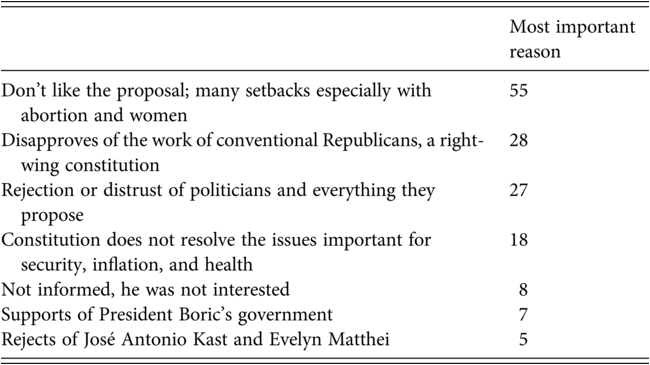

The Chilean evidence is more to the point.Footnote 11 Cadem (2022) runs a survey immediately after the NO vote in September 2022. The results are presented in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Reasons for “NO” vote of Chilean referendum in September 2022

| First reason | Overall mentioned | |

|---|---|---|

| Because the process that the constituents carried out was very bad/distrustful | 21 | 40 |

| Because of multinationalism and indigenous autonomy | 16 | 35 |

| Because I disapprove of President Boric’s government | 12 | 39 |

| Due to the instability and political and economic uncertainty that generates fear and concern | 12 | 24 |

| Due to restrictions on freedom and private property in health, education, pensions, and housing | 11 | 13 |

| Because the country is on the wrong path in terms of economy, crime, and Mapuche conflict | 9 | 13 |

| It is not necessary to make a new constitution; it must be reformed | 7 | 12 |

| For value issues such as abortion, regionalism, feminism, and environmentalism | 6 | 8 |

| Due to changes to the political system | 6 | 8 |

The reader can verify some policy evaluations about the role of the referendum – for example, the disagreement with the recognition of multinationalism and indigenous autonomy, the restrictions of freedom and private property, and objections to value issues like abortion. I remind the reader that this is a very progressive constitution, and these are right-wing objections. However, most objections are contextual: the process was inappropriate, the government is wrong, political and economic uncertainty, and so on.

More to the point, González-Ocantos and Meléndez (Reference González-Ocantos and Meléndez2024), based on data collected during this referendum, performed an “innovative conjoint experiment … to estimate if different elements of the constitution sunk the proposal.” Their conclusion is that “the incumbent’s popularity significantly affected vote choice.”

With respect to the second referendum, the rejection reasons according to the Cadem (2022) poll are presented in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2 Reasons for “NO” vote of Chilean referendum in December 2023

| Most important reason | |

|---|---|

| Don’t like the proposal; many setbacks especially with abortion and women | 55 |

| Disapproves of the work of conventional Republicans, a right-wing constitution | 28 |

| Rejection or distrust of politicians and everything they propose | 27 |

| Constitution does not resolve the issues important for security, inflation, and health | 18 |

| Not informed, he was not interested | 8 |

| Supports of President Boric’s government | 7 |

| Rejects of José Antonio Kast and Evelyn Matthei | 5 |

I will provide some more-to-the-point evidence from the EU because, after the European convention and a series of adjustments to the constitutional documentFootnote 12 it produced, several EU countries chose to submit the constitutional document for evaluation by referendums. This process is exactly equivalent to a series of constitutional ratifications. While some of the countries who had selected the referendum process approved the document, two of the founding countries of the EU, France and the Netherlands, rejected it. The rejection produced a high level of anxiety across the EU first because of the status of the founding countries (particularly France) and second because it was not clear what the implication of a NO vote was. While it was clear that the previous institutions would remain in place, it was not clear how the apparent impact would be overcome. The European Commission declared a six-month period of reflection, and all the European elites were extremely interested in the course of action to overcome the situation. In this context, the commission requested polls in the countries that rejected the constitutional document. The way these polls were performed was by asking open-ended questions and classifying the answers after the fact. The reason they chose this procedure was that the commission wanted to genuinely hear and study the opinion of the people who had rejected the new document. Among other things, this document was a significant simplification and replacement of all the past intergovernmental agreements of the EU countries, which were kept in place and altered by more recent documents.Footnote 13

Table 4.3 presents the reasons why the two peoples voted NO in the referendum. From the differences in the answers, one can understand the superiority of the method selected (codifying the answers a posteriori). Focusing on the specific reasons, the factual irrelevance of the answers is quite impressive. For example, employment and economic conditions (in France) are irrelevant to the constitution. Opposition to national government is not an issue of European jurisdiction (in both countries) but of national electoral politics. The issue of the reduction of national sovereignty had already been materialized. Finally, the original irrelevance of the anti-Turkish feelings in France would have never been captured by a closed questionnaire.

Table 4.3 What are all the reasons why you voted “NO” at the referendum on the European Constitution?

After evaluating the situation the referendums created, the leaders of the EU decided not to use any referendums for the continuation of the process. In order to facilitate this decision, they removed the European flag (blue with twelve yellow stars) and the EU anthem (Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy”) so that there would not be reasons like abdication of national sovereignty that would justify the use of referendums. The commitment was firm and was followed in all countries except for Ireland, where it is constitutionally mandated.

According to my analysis, the vote of NO may depend on the number of voters of Type (3).Footnote 14 There were many such voters in the two reported referendums in the EU, fewer in Italy, and perhaps an insufficient number to be pivotal in Chile.

Conclusions

This chapter started with the presentation of complicated amendment provisions, which led us to the calculation of the core of the Italian case and the absence of it in the Chilean case. However, I explained why Article 129 in the Chilean case, which eliminates the core, will never be applied in a democratic country; consequently, in the empirical analysis that I perform in Chapter 6, I will use the combination of Articles 127 and 128 of the their constitution (but not Article 129). In both cases, the cores of the constitutions of these countries are large enough that successful constitutional amendment requires lots of preparation and successful coalition formation. In Chile, we saw that significant amendments required five years of negotiations to be successful.

I described the conditions of amendment (or replacement) failure in both countries, which were unanticipated referendum rejections. Although referendums were analyzed in Chapter 2 and were found to be malleable institutions, there were two reasons for these failures. In both cases, the agenda-setting institution was a partial reason. In Italy, the referendum was driven by Renzi’s party alone. As I argued, it was a very reasonable amendment that would have improved the way Italian institutions function. In Chile, the first referendum was drafted by a left-wing coalition ignoring the preferences of the right-wing parties, and the second was the opposite. One can argue that what the Chilean people did was the only reasonable option against runaway elites who wanted to weaponize the constitution. The constitutional document of the EU did not provide any reasonable reasons for a return to the status quo. Lupia (Reference Lupia1994, Reference Lupia2006) has argued that people use shortcuts in order to guess the reasonable answers to different political dilemmas that they face. With respect to the examples I gave in this chapter, one can argue that they did a very good job in Chile, a questionable one in Italy, and a bad one in the EU. However, one particular modification of institutions would help the popular decision-making. I demonstrated that a plausible reason for the failures was that people – specifically Type (3) voters – very often do not seem to focus on the actual question, which is the comparison of the amendment to the status quo.

Cancellation of constitutional referendums (as they did in the EU) would produce the results desired by the political elites by moving the power to make decisions on complicated issues from the masses back to them. However, an alternative procedure would be to make sure that coalition building is necessary for the constitutional design phase – that is, the constituent assembly (a proportional electoral system and qualified majority bigger than anticipated splits would achieve that result).Footnote 15 Further, a modification of the question of the referendum so that it would include the status quo would extend the courtesy of making the actual question apparent not only to the elites (as it is done by parliamentary procedures) but to the people as well. So, instead of “Do you want this amendment (or this constitution), yes or no?”, the question should be: “Do you prefer this amendment (or this constitution) to the current one?”. These institutional modifications make a proposal more difficult to emerge, but, when it does, it is more likely to be accepted because it will be supported by the consensus of parties that contributed to its design and, consequently, amendments will be more durable.

The rewording of the question I am proposing may be an issue involving serious political debate. In order to make sure that the process is not hijacked politically, the summary of the question (once the amendment or the alternative is finished) may be delegated to the judiciary or to a specially appointed committee of experts selected by a supermajority.

As we saw in Chapter 1, there is an aversion of political elites toward referendums. The reason is that referendums supersede their legislative authority. However, there are cases where referendums are the only way to respect the popular will. In Chapter 1, we showed examples of simple questions like abortion or the electoral system where the legislature disagrees with the public and tries to reduce the applicability of referendums in order to have its preferences prevail. There are cases in which referendums are excluded as a means to make decisions – for example, on taxes in several jurisdictions. There are cases in which the question is evaluated by the judiciary and the referendum may be aborted. In Italy, unconstitutional referendums have to be approved by the Constitutional Court, which evaluates if the issue is simple enough to have a YES or NO answer.

Briefly, I proposed two amendments to the referendum process. At the level of agenda setting, I proposed a competitive (among potential agenda setters) and/or restrictive (with involvement of the judiciary) process which eliminates unconstitutional or extreme proposals. At the level of voting, I proposed institutional solutions that “turn the referendum into an election” – that is, identify the issue precisely.Footnote 16 The amendments I am proposing are simple and less restrictive than the existing practices and are designed to preserve referendums rather than eliminate them.