Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a contested phenomenon. Here, we refer to CSR as an umbrella term to describe how business firms, small and large, integrate social, environmental and ethical responsibilities to which they are connected into their core business strategies, structures and procedures within and across divisions, functions as well as value chains in collaboration with relevant stakeholders. As yet, there is no consensus as to what exactly these responsibilities are, how to best address them, and more generally what the role of business in society is and should be. Researchers, managers, politicians and other stakeholders such as the media have not reached an agreement about the scope and content of CSR. At the same time, CSR has moved from the margins to the mainstream. It now takes centre stage in managerial and scholarly discourses and has entered the boardroom of most corporations.

Our aim with this Element is to shed light on the contested nature of CSR. We thereby do not seek to develop theory or provide an exhaustive review of the literature. Rather, we select those key questions and topics in the contemporary debate on CSR that provide those interested in the concept with a concise and critical introduction to the state-of-the-art of CSR research and practice. In going beyond yet another handbook of ‘how to manage’ CSR strategy and implementation, we provide readers with a fresh perspective to reflect on how CSR is commonly practised by business firms. By illuminating and scrutinizing present approaches to CSR, this Element aims to provide readers with the ability to understand key concepts in the context of CSR and how businesses attempt to meet the social and environmental expectations of society.

This Element is structured into five sections that each deal with a central question in the CSR debate. First, we ask what the relevant CSR issues are that companies nowadays are confronted with, and what the resulting scope of CSR is. Here, we make a critical distinction between what we call the ‘low-hanging fruits of CSR’ and the ‘high-hanging fruits of CSR’. We further explain the important shift in understanding CSR no longer as ‘how the money is spent’ but as ‘how the money is made’. Second, we ask why companies would pay attention to those issues, illuminating the key drivers and motives for CSR. We unfold two important tensions of the instrumental motive for CSR, namely the ‘ethical fallacy’ and the ‘managerial fallacy’, and argue that contemporary CSR is mainly driven by stakeholder expectations that form the institutional infrastructure of CSR. Third, we ask how business firms can implement their CSR commitments into organizational practices and procedures, reviewing important components of the implementation process such as codes of conduct, policies, CSR management frameworks, stakeholder engagement and CSR reporting. We also highlight important complications that are widely observable among business firms in the CSR implementation process. Fourth, we turn to the dark side of CSR and ask why greenwashing and Corporate Social Irresponsibility (CSiR) became common phenomena in the context of CSR. We portray empirical evidence of this and unfold selected theoretical approaches to illustrate some important reasons that help to understand and explain the prevalence of such behaviour. Fifth, in wrapping this Element up, we ask what the key themes are that (should) shape the CSR discussion over the next decade, zooming in on new responsibilities that emerge from digitalization as well as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1 What is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)? Scope, Issues and Definitional Clarity

The objectives of this section are:

To introduce key social, environmental and ethical issues to which business firms are confronted and which define the scope of what is commonly understood as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

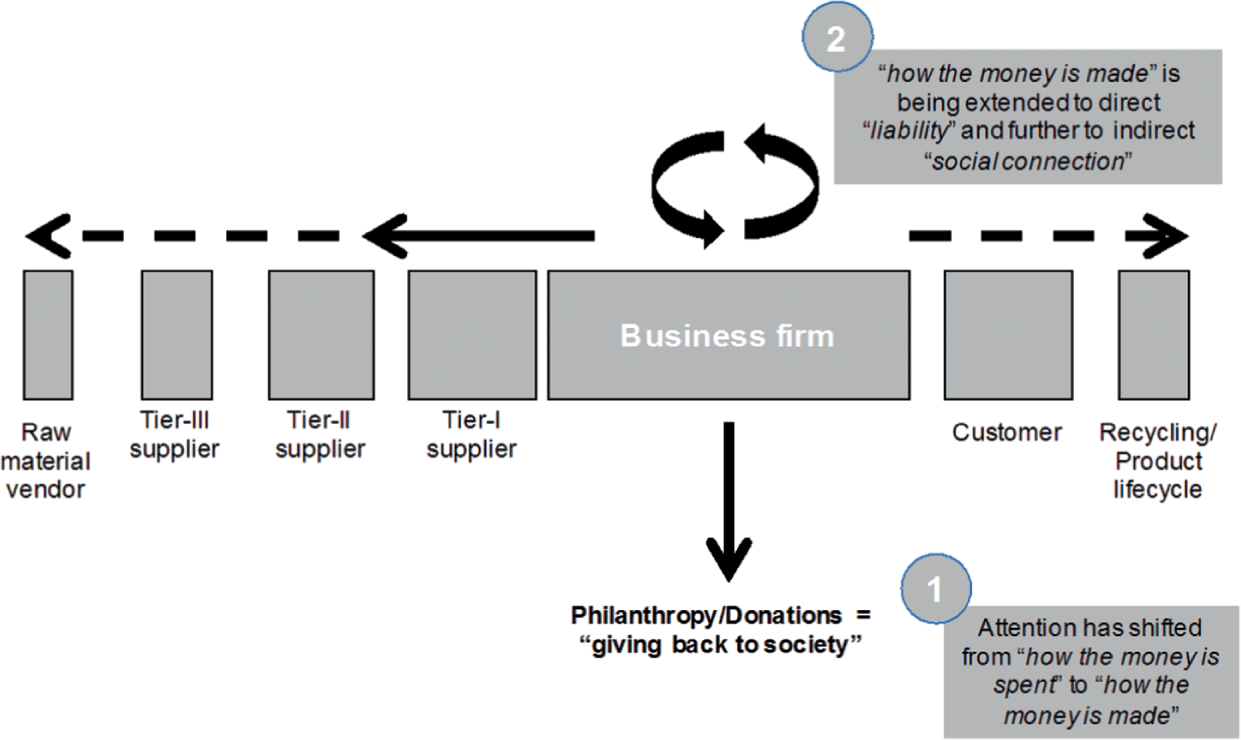

To show that CSR is fundamentally about ‘how the money is made’, in other words about responsibility for harm that emerges along globally expanded value chains. Importantly, CSR is no longer constrained to ‘how the money is spent’, i.e. limiting CSR to philanthropy or other forms of charitable actions.

To explain that for understanding CSR in a globalized economy, attention needs to shift from a liability logic based on legal obligations towards the logic of social connection between companies and societal impacts along their supply chain.

1.1 From ‘How the Money Is Spent’ to ‘How the Money Is Made’

Nowadays, hardly a day passes on which we don’t hear in the media about yet another corporate scandal, irresponsible behaviour or cases of social, environmental or ethical wrongdoing in which business firms are involved in one way or another. Some of these cases come high on the agenda of public attention, such as working conditions in global textile supply chains in the aftermath of the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory building in April 2013. That day, 1,135 workers of a garment factory in Bangladesh died, and 2,438 were injured because of extremely poor safety conditions and an overcrowded factory building. Such kind of – oftentimes deadly – harm to workers in global supply chains of fashion brands is unfortunately not rare. Rather, the Rana Plaza incident was only a particularly severe case leading to the long necessary public outcry that called for change in the global fashion industry.Footnote 1

However, attributing responsibility for such tragedies is not as easy or straightforward as it might seem. One might indeed ask who is responsible for violations of basic health and safety conditions at the workplace: factory operators flouting national laws? Local governments failing to enforce these laws? Multinational retailers squeezing the last penny out of suppliers? Western consumers unwilling to pay more than a few bucks for a T-shirt? The international community failing to intervene? It may not come as a surprise that much of the subsequent controversy was not primarily directed at the local factory owners, but mainly against powerful Western multinational textile brands such as Adidas, H&M, Inditex (the company behind labels such as Zara and Mango), Primark and the like. Western fashion brands reacted not by denying any sort of responsibility, but rather by acknowledging their linkages to factories violating health and safety conditions.

As a consequence, soon after Rana Plaza, major players in the fashion industry, mainly from Europe, set up an initiative called the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh in May 2013, often referred to as ‘the Accord’. This initiative is an independent, legally binding agreement between fashion brands and trade unions designed to work towards a safer garment industry in Bangladesh. Signatories of the Accord pledged to enable a working environment in which basic standards of workplace health and safety measures are implemented and monitored by an independent inspection programme involving retailers, workers, trade unions, local governments as well as non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Furthermore, signatories promised to ensure that safety conditions in involved factories were made publicly available to allow inspections and devise corrective measures in case of breaches of the key health and safety guidelines. In addition, democratically elected health and safety committees were installed in all factories to identify and act on health and safety risks, while worker empowerment was encouraged through training, complaints mechanisms and by giving workers the right to refuse unsafe work. Only a few years later, more than 200 apparel brands had signed the Accord which now covers more than 1,000 Bangladeshi garment factories. Today, six years after the incident, workers’ rights are still much of an issue in Bangladesh and other emerging markets.Footnote 2 However, the example at least demonstrates that even though global fashion brands are connected to those factories only through complex and globally expanded webs of supply chains and production networks, they have accepted a responsibility for the health and safety of workers in distant places.

Another example that, relative to the Rana Plaza tragedy, remained somewhat under the radar of large-scale public attention is a ‘food drive’ organized by US retailer Walmart. The case strikingly illustrates how public perception of social and environmental responsibilities that can be attributed to corporations has changed over the last few decades. According to media reports,Footnote 3 for several years some US branches of Walmart organized Thanksgiving food drives for their own employees in order to help those in need by asking co-workers to donate food. At first sight, this may sound like a nice idea. Walmart employees show how much they care about each other by helping their fellow colleagues with too little income to buy their own food to have a nice Thanksgiving dinner. However, as a CNN journalist reported, many workers at Walmart rather felt betrayed by such hypocrisy and the subsequent public outrage came as no surprise.

While local store managers at Walmart may have even acted out of good intention, critics pointed out that according to a report by the National Employment Law Project in 2012,Footnote 4 Walmart turned out to be one of the worst-paying companies in the USA. In fact, associates at the company were paid so poorly that they could hardly cover their daily bills, let alone a proper Thanksgiving feast. Critics hence argued that the whole idea and need for organizing such a food drive would not be necessary if Walmart would simply pay their employees a decent wage so that they could afford enough food on their own in the first place. In some way, Walmart was delegating the responsibility for its own employees to its other employees. According to Forbes magazine,Footnote 5 at the same time Walmart’s net income was at around US$17bn, and ample amounts of bonus cheques and stock options have been paid to top management and shareholders.

What do the Rana Plaza factory collapse, the Accord in Bangladesh as well as the Walmart food drive demonstrate about contemporary CSR and the roles and responsibilities of business firms in society? They show how CSR has moved from the idea of ‘giving back to society’ towards a concept that is about how value is created by a firm, and what the social, environmental and ethical implications of the corresponding value-creating processes are. CSR is no longer constrained to philanthropy or charity and how the money is spent. According to this logic, companies would maximize their profits without costly adjustments in core business operations, and then compensate for some of the collateral damage by making a few donations to affected stakeholders, as the case of Walmart demonstrates. Today, CSR is elevated to a strategic level and has become fundamentally about how the money is made. Hence, it is about integrating CSR principles in businesses’ strategy and core operations that include all parts of the often globally expanded value chain. This includes paying fair wages to workers in distant factories and making sure production processes are socially and environmentally responsible (Reference Wickert, Scherer and SpenceWickert et al., 2016). The scope of responsibility is then no longer restricted to the company’s headquarters, but is instead stretched along its entire, and often global, supply chain and production network. The Rana Plaza case and the subsequent launch of the Accord demonstrate how CSR has gained strategic relevance in a globalized world.

The expanded scope of CSR brings along a number of complications. As we will show in this Element, disaggregated global supply chains have increasingly replaced the vertically integrated organizational structure that dominated corporations of the twentieth century across multiple industries. While this may allow cost reductions and efficiency gains, it limits a business firm’s ability to control and monitor its own supply chains, including labour practices and the very locations from which materials are sourced (Reference Kim and DavisKim & Davis, 2016). Moreover, stakeholders increasingly attribute corporate responsibility upstream to actors along the supply chain. This includes those workers in sweatshop factories in Bangladesh that sew shirts for global retailers such as H&M, Nike or Adidas. Moreover, upstream responsibility can go even further to fourth- or fifth-tier suppliers that for instance harvest and deliver raw cotton in the fields of Uzbekistan.Footnote 6 Responsibility also reaches downstream to consumers and includes the product life cycle. For example, there are potential implications for the environment once products are disposed of as, for instance, in the case of smartphones. Product ingredients may also have implications for consumers, such as food products with high amounts of sodium or trans fats typical in the fast food industry. Figure 1 summarizes these developments.

Figure 1: How CSR has transformed from philanthropy to liability to a social connection responsibility.

1.2 From a Liability to a Social Connection-based Understanding of CSR

When considering how CSR has evolved, it appears that stakeholders, including civil society groups, NGOs and consumers, have started to attribute responsibility to firms no longer based on liability (i.e. the legal relationship between two entities). Instead, responsibility is increasingly attributed based on a firm’s social connection to an issue. The liability approach to CSR is based on a legal mindset. Here, responsibility emerges when a legal relationship, and hence an immediately visible causal link between action and harm, can be objectively shown. As the examples above show, holding companies legally responsible is limited when CSR is about how the money is made. This is particularly evident in globally dispersed and highly complex production networks. A clear identification of supply chains is extremely difficult since they involve dozens of steps and unclear or interrupted legal relationships between raw-material producers, vendors, manufacturers, distributors, retailers, and so on. Indeed, over the past decades new communication technologies, low-cost shipping and the liberalization of trade have led many businesses to reconsider their ‘make or buy’ decisions covering nearly all sectors, from manufacturing to services. As Reference Kim and DavisKim and Davis (2016: p. 1897) have pointed out, ‘Nike shoes, Apple phones, and Hewlett-Packard laptops are all manufactured by far-flung contractors, not by the company whose logo is engraved on the product.’

An alternative understanding that offers justification for why and when responsibility emerges is therefore necessary. Evidence suggests that companies have started to acknowledge and act according to this new logic of CSR. While in the past companies used to deny responsibility by pointing to the lack of a legal relationship between themselves and a certain supplier where some harm occurred, the public no longer accepts this. Instead, companies have started to act on a concept of responsibility that instead refers to the consequences of their structural connectedness, the social connection that holds actors ‘responsible precisely for things they themselves have not done’ (Reference YoungYoung, 2004: p. 375).

Based on social justice theory, the philosopher Iris Marion Young has developed the concept of social connection (Reference YoungYoung, 2004). Her reasoning provides the moral philosophical, rather than legal, basis for thinking about and justifying why and to what extent business firms should meet their social responsibilities in the global marketplace. Her main concern is where firms might create and maintain systemic forms of injustice or harm to distant parties, such as factory workers in Bangladesh or elsewhere. As such, the social connection approach provides an analytical basis for identifying the areas where it is difficult to establish an immediate causal connection between a social, environmental or ethical problem (e.g. low labour standards for supplier factory workers in developing countries) and companies based in other parts of the world. An important assumption here is that systematic disregard of environmental standards or the continuous exploitation of workers and violations of their rights are sources of chronic, rather than incidental, injustices that are linked to the systems and structures of globalized production networks (Reference SchrempfSchrempf, 2014; Reference WickertWickert, 2016).

What Reference YoungYoung (2004: p. 365) then argues is that companies and also consumers have to ‘acknowledge a responsibility with respect to the working conditions of distant workers in other countries, and to take actions to meet such responsibilities’. If companies are said to hold responsibility for the welfare of subcontracted workers in distant places, then this type of responsibility cannot be understood as a legally grounded liability but must be seen as a morally grounded ‘political duty’. The liability logic would imply that actors who are directly involved in causing injustice plausibly can be held responsible for the consequences. This may include factory owners, but also governmental authorities that are unwilling or unable to enforce basic laws that protect human rights and labour standards. The case of the Rana Plaza tragedy illustrates that indeed some factory owners had been brought to court and received substantial fines because of their legal responsibility. The problematic aspect in the liability logic, however, is that it allows those companies which have sourced from that factory, including well-known fashion brands such as H&M, to defend themselves by arguing that they did not actually own the factory. In consequence, there has not been an immediate legal relationship to the factory owner, as there are typically multiple subcontractors involved (Reference YoungYoung, 2004).

However, stakeholders such as consumers or NGOs no longer accept that powerful global brands can hide behind the excuse of not being legally connected. For example, the Accord in Bangladesh strikingly demonstrates that companies have acknowledged their extended responsibility for global injustice and have taken decisive action. At least among the well-known companies with a valuable brand name to protect, you would hardly find open denial of any sort of responsibility for what happens deep in their supply chain. Young indeed argued that any company’s actions partly depend on the actions of others. In other words, ‘the scope of an agent’s moral obligation extends to all those whom the agent assumes in conducting his or her activity’ (Reference YoungYoung, 2004, p. 371). This means that any company that sources raw materials or pre-products made under inhumane or environmentally damaging conditions by doing so benefits for instance from low prices that are enabled because of those very conditions. Thus, the beneficiary becomes indirectly connected to some form of injustice. If a company relies on low-priced finished products to gain an edge over its competitors, it implicitly depends on the exploitation of workers who are paid below minimum wages. Young argues that no company can deny this connection to processes of structural injustice and that there is at least a moral, if not a legal, obligation of responsibility.

From an ethical point of view, those who participate in the creation or perpetuation of these structures need to recognize that their actions contribute to this injustice and have to take responsibility for altering these structures in order to prevent or reduce injustices. Civil society and all kinds of stakeholder groups have picked up this basic understanding of why and how responsibilities in global supply chains can and should be attributed and shared – some more explicitly than others. What can be observed is that actions of corporations to be considered legitimate and hence socially acceptable are increasingly related to the idea of social connection. What emerged as a largely ethically grounded rationale has turned into a widespread social expectation that is shared by large parts of public audiences.

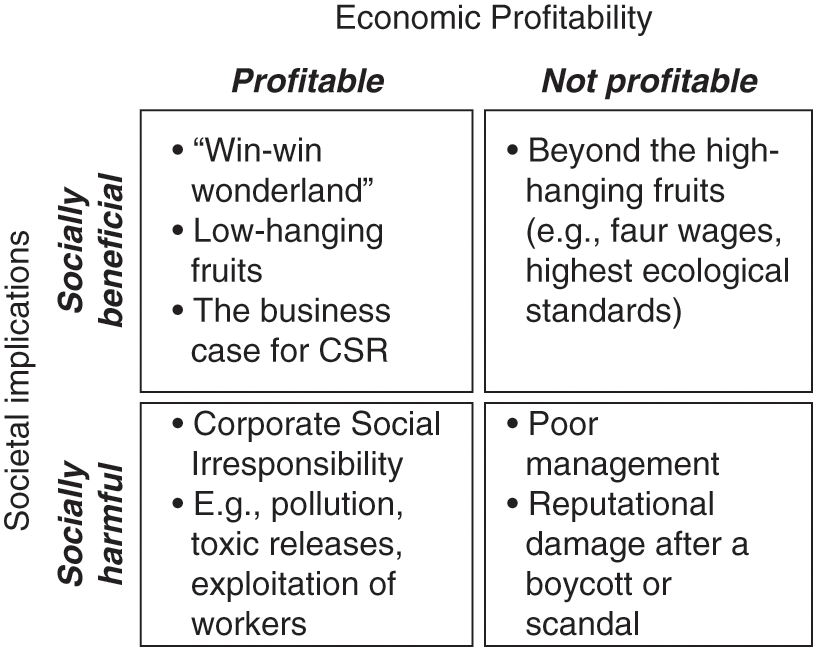

1.3 The Low- and High-hanging Fruits of CSR

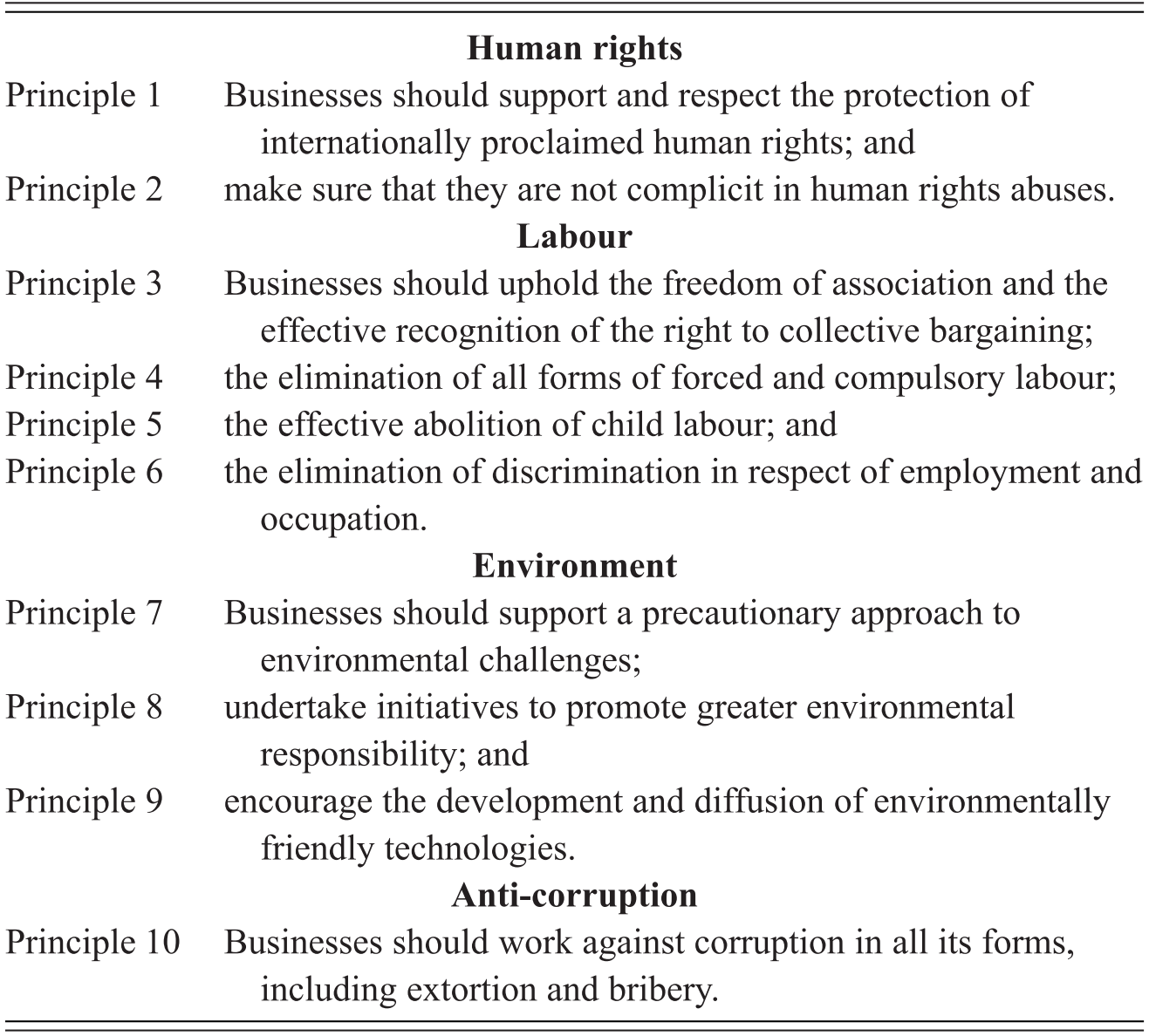

If we take the social connection approach as a basis for justifying that certain responsibilities exist, then what will be the relevant CSR issues that have emerged on the corporate radar? They would certainly stretch the scope of CSR beyond issues such as philanthropy or building a kindergarten at the corporate headquarters. Indeed, the contemporary understanding of CSR suggests that attention has shifted from what could be called the ‘low-hanging fruits’ to what can better be described as ‘high-hanging fruits’ (see e.g. Reference Wickert, Scherer and SpenceWickert et al., 2016; Reference Wickert and de BakkerWickert & de Bakker, 2018).

Low-hanging fruits are certainly not unimportant and often also have significant social or environmental impacts. They include things such as pollution control, eco-efficiency and waste management, granting employee benefits such as free lunch or health benefits. Hence, they typically describe issues that reach comparably low up or down the supply chain. We can define low-hanging fruits as those issues where a connection to core business operations is directly visible because they are in a company’s immediate sphere of influence. Often, they are even simply mandated by law, such as environmental or health and safety regulations. Because of this, low-hanging fruits generally allow for easily establishing a business case (i.e. enhanced profits through higher sales or reduced costs) in terms of straightforward and inexpensive behavioural and material changes. Tackling such issues then leads to a directly measurable effect with clear financial benefits for the company. Research suggests that many companies indeed begin their CSR journey by addressing low-hanging fruits (e.g. Reference Baumann-Pauly, Wickert, Spence and SchererBaumann-Pauly et al., 2013).

Reference Sharma and HenriquesSharma and Henriques (2005: p. 158) studied the Canadian forestry industry and their findings reflect what can be found in many other industries as well: companies are well positioned in the ‘early stages of sustainability performance such as pollution control and eco-efficiency’. However, more fundamental changes in business models that would involve the redefinition of business ecosystems and which would require substantial investments in organizational systems and processes are still ‘in their infancy’.

Turning to the high-hanging fruits, as the example of the forestry industry suggests, becomes progressively more difficult and often requires large-scale changes and reconsideration of production processes, or for instance entirely new technologies and buyer-supplier relationships. For example, a telecommunications company such as Vodafone may place recycling bins in its shops to collect used smartphones. This may seem like a nice gesture, but it certainly remains a low-hanging fruit. Cost implications for Vodafone are relatively low, the measure is far away from a reconsideration of its business model, and responsibility is basically delegated away to consumers to actually return their used phones. However, the real CSR challenge would be to reduce the number of smartphones sold and then thrown away after only a year or so in the first place. This, however, is fundamentally against the business model of many telecommunications providers and how they are currently marketing their products. On top of that, making sure phones are not produced under inhumane conditions using so-called conflict minerals is an even more complex problem.

So what are these high-hanging fruits? Conflict minerals are a case in point that has been gaining more attention by the public as well as by companies and governments (Reference Reinecke and AnsariReinecke & Ansari, 2016). When thinking of Vodafone or one of its competitors, social and ecological problems connected to the mining of minerals very well underscore that a liability logic needs to be replaced by a social connection approach. To illustrate the idea of high-hanging fruits based on the social connection logic, let us take the example of smartphones and other electronic devices that nowadays nearly everyone uses. Where does the production of a smartphone actually begin? It begins with the extraction of raw minerals in mines, many of them located in some of the world’s poorest regions such as Central Africa.

Conflict minerals are natural resources extracted in zones of armed conflict and sold to finance and perpetuate the conflict. One of the most prominent examples has been the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where various armies and rebel groups have profited from mining operations while contributing to violence and exploitation during wars in the region (Global Witness, 2017). Beyond Congo, mineral trading has funded some of the world’s most brutal conflicts for decades and fuelled human rights abuses in areas such as Afghanistan, Colombia, Mexico and Zimbabwe. The four most commonly mined conflict minerals (known as 3TGs, from their initials) are cassiterite (for tin), wolframite (for tungsten), coltan (for tantalum), and gold ore. So-called blood diamonds are also often mentioned alongside the problems associated with conflict minerals, as they are typically mined under similarly horrifying conditions. These minerals and jewels enter global supply chains and are essential in the manufacture of a variety of devices, including consumer electronics such as mobile phones, laptops, and MP3 players as well as jewellery and batteries for electric cars. Because of the highly complex webs of supply chain relations and multiple intermediaries, it is very difficult for consumers to know whether their favourite products fund armed conflicts (Reference Kim and DavisKim & Davis, 2016).

Next to being a source of funding for armed conflicts, the conditions under which the minerals are being mined are extremely problematic. Unsafe working conditions and work-related injuries and deaths, forced and child labour, corruption as well as other systemic human rights abuses are the norm (Global Witness, 2017; Reference Kim and DavisKim & Davis, 2016; Reference Reinecke and AnsariReinecke & Ansari, 2016). Conflict minerals mining therefore represents a striking case of ‘modern slavery’ (Reference CraneCrane, 2013). While we may think that such things as slavery might be something from the dark side of history long overcome, forms of modern slavery continue to exist. Such forms of slavery occur if the following conditions are met: people are (1) forced to work through threat; (2) owned or are controlled by an ‘employer’, particularly through mental, physical or threatened abuse; (3) de-humanized and treated as a resource; (4) physically constrained or restricted in freedom of movement; (5) subject to economic exploitation through underpayment (Reference CraneCrane, 2013: p. 51). According to a reportFootnote 7 of the International Labour Organization (ILO) from 2017, modern forms of slavery affect more than 40 million people, including almost 25 million in forced labour, and more than 15 million in forced marriage. Twenty-five per cent of the victims are typically children. Out of those trapped in forced labour, 16 million are exploited in the private sector including domestic work, construction, agriculture or mining. Other forms include forced sexual exploitation and forced labour imposed by state authorities.

Modern slavery in the context of conflict minerals has led to increased public awareness and strong campaigning by NGOs such as Global Witness, urging governments around the world to act and address the problem of conflict minerals. In June 2016, after years of negotiations, the European Union (EU) reached a political understanding on a new regulation which is intended to break the links between the minerals trade, armed conflicts and widespread and systematic human rights abuses. The EU regulation focuses on conflict-affected or high-risk areas, which refer to regions in a state of armed conflict, fragile post-conflict areas, or areas with weak or non-existent governance and security, such as failed states. Similar regulations emerged in the USA under the Dodd Frank Act of 2010.

To meet these new regulations, firms will be required to demonstrate that they have sourced their minerals responsibly and transparently. Stakeholders including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the European Commission as well as NGOs such as Global Witness have elaborated a process of due diligence to support companies in checking their supply chains and ensuring that they prevent conflict minerals from entering global markets. Due diligence thus describes an ongoing process through which companies can identify whether the minerals they purchase or handle have been linked to human rights abuses, conflict or corruption, and put in place strategies and management systems to mitigate these risks. Due diligence also includes carrying out independent third-party audits and annually reporting on progress. As a concept, it is based upon the premise that companies have a responsibility to ensure that they do not benefit on the back of serious harm to individuals, societies or the environment. At the same time, both the EU and the OECD, which have played a key role in developing the due diligence framework, emphasize that all companies buying, selling or handling any minerals should conduct due diligence on their supply chains. Notably, however, the extent and nature of an appropriate level of due diligence for each company depends on individual circumstances, such as the size of the company, its sector, location and position in the supply chain. In other words, Apple’s due diligence should look very different from that of a one-person operation run out of Kigali, Rwanda. Similarly, the due diligence process of the global diamond miner and trader De Beers should differ significantly from that of a jewellery designer based in Antwerp, Belgium.

Overall, the case of conflict minerals demonstrates some of the high-hanging fruits and upstream responsibilities with regard to the complex production processes of many of the electronic devices we use on a daily basis. It becomes even more complicated when looking downstream: when we buy a new phone once a year, the old one will end up somewhere. Indeed, according to investigationsFootnote 8 of the ILO, e-waste is currently the largest-growing waste stream, exceeding 50 million tons annually. It is hazardous, complex and expensive to treat e-waste in an environmentally sound manner, and there is a general lack of legislation or enforcement surrounding it. Most e-waste ends up in the general waste stream without proper recycling. Eighty per cent of the e-waste in developed countries sent for recycling ends up being shipped (often illegally) to developing countries to be recycled by hundreds of thousands of informal workers. Such globalization of e-waste has adverse environmental and health implications. Open landfills abound in countries such as Ghana where workers are exposed to hazardous substances released on vast unofficial waste dumps, lacking basic protective clothing and health and safety measures. Compared to the case of conflict-minerals, the topic of e-waste is still marginal in terms of public attention and actions taken by companies. It remains to be seen what actions will be taken by civil society, governments and firms to address yet another high-hanging fruit of CSR.

1.4 CSR in the Context of Globalization

It is no surprise that these issues and ideas about the new roles and responsibilities of business in society have reached the corporate world. Even more so, businesses are nowadays under ever-increasing pressure and public scrutiny. In light of the severity of issues such as conflict minerals, and reoccurring scandals, misbehaviour, fraud and greenwashing, even management gurus such as Michael Porter have concluded that ‘the capitalist system is under siege. In recent years business increasingly has been viewed as a major cause of social, environmental, and economic problems. Companies are widely perceived to be prospering at the expense of the broader community’ (Reference Porter and KramerPorter & Kramer, 2011: p. 64). In consequence, Porter continues, ‘The legitimacy of business [i.e. the societal acceptance of what businesses do and how responsibly they behave] has fallen to levels not seen in recent history’ (p. 64).

As the prominence of CSR and its entering into the corporate boardroom underscores, the business world has reacted. In order to gain back the legitimacy and trust of the broader public, business firms began to develop comprehensive CSR profiles. While the idea of social responsibility was not entirely new, however, in particular since the end of the twentieth century, the way CSR is understood and practised is influenced by three key developments. First, in the course of globalization, the political influence of national states has been waning. In what has been called the ‘postnational constellation’ (Reference HabermasHabermas, 2001), national governments have limited control over corporations operating on a global scale and are thus not always able to safeguard the social well-being of their citizens. Second, civil society has developed a much stronger social and environmental awareness, often a result of the political campaigns of activists. Compared to traditional party politics, such campaigns provide an alternative means of addressing topics such as social inequality, ecological destruction, or climate change.

Third, the increasing influence of financial markets on economic success (often referred to as the ‘financialization’ of the economy) and the growing mobility of corporations have induced an economic shift (Reference Scherer and PalazzoScherer & Palazzo, 2007). For example, in order to circumvent high taxation or exploit low wages, firms relocate their headquarters to countries considered as tax havens or where they can afford to pay the lowest possible wages or benefit from lax environmental standards. The failure to address global warming is a case in point where multinational corporations (MNCs) have the chance to arbitrate among alternative regulations. They can escape strict regulations by moving their operations or supply activities to countries with rather low standards (e.g. to lower their tax burden or cost of production). All of this has led to a ‘globalization of responsibility’ and calls for alternative ways to regulate global business activity. Reinforced by media pressure and information technology, these three developments have led to the claim that business should assume more economic, social, environmental and ethical responsibility.

Figure 2 illustrates how the CSR landscape has changed due to the process of globalization. First, the relationship between the three most important societal actors – business firms and the private sector more generally, nation states and governmental authorities, and civil society – has been fundamentally transformed. Second, new players have been formed or (re)entered the playing field, such as self-regulatory initiatives of the private sector, transnational organizations and associated initiatives such as the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), or multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) such as the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). We will explain these developments in greater detail below.

Figure 2: Relationships between business, governments and civil society in the context of globalization.

1.5 Towards a Political Understanding of CSR

In order to understand the assumptions and foundations of the transformation of CSR in a globalized economy, it is useful to distinguish it from traditional conceptualizations. Before the turn of the century, scholars of CSR generally held the assumption of relatively homogeneous societal expectations, functioning nation states, and democratic institutions that can provide and enforce regulatory frameworks to guide business conduct (for an overview, see Reference WindsorWindsor, 2006). This perspective reflects the classical ‘Friedmanian’ view on CSR. Back in 1970, economics Nobel laureate Milton Friedman published a now (in)famous essay in which he proclaimed that the only responsibility of business firms is to increase their profits for the benefit of shareholders, and that it should be the responsibility of governments to ensure societal welfare (Reference FriedmanFriedman, 1970). According to Friedman, corporations should not undertake social policies and programmes because this is what governments are supposed to do. Governments are elected by the public to pursue social goals whereas corporate managers are acting on behalf of shareholders, so their accountability is primarily to shareholders, not to the public.

Based on this assumption Friedman proposes a strict political division of labour in society – corporations pursue economic goals, while governments pursue social goals. It could be argued that his argument was defensible because when the original article was published, globalization and the transnational integration of the economy were at significantly lower levels than today. At the same time, Friedman’s understanding of CSR corresponds largely with what we now consider as philanthropy or charity, or what we have described as ‘how the money is spent’. More recently, the question of the wider responsibilities of business has, however, become far more complex, and societal stakeholders are concerned about how the money is made. Moreover, today, we observe that corporations have taken on or are expected to take a role in society that overlaps and interferes quite substantially with that of governments. This happens mainly in three areas that reflect so-called regulatory gaps (see also Reference Crane and MattenCrane & Matten, 2015):

1. Governments are no longer providing basic social needs: In the past, tasks such as the provision of water, electricity, education, healthcare, basic transportation, public safety and telecommunication were largely considered a fundamental role of governments in exchange for tax earnings. Yet, in consequence of what might be called a neo-liberal watershed of privatization, liberalization and deregulation, services such as water provision have been privatized in many countries and are hence in the hands of companies. When companies take responsibility for important issues such as people’s health and sanitation, a somewhat more complex social responsibility arises. In fact, companies in these new areas face many of the societal expectations hitherto directed at governments and the political sphere in general.

2. Governments are unable or unwilling to address social needs: Particularly in less-developed countries, businesses often deal with government authorities that lack the resources to cater effectively for basic social needs, even though they are formally entitled to do so. To compensate for this, companies have started to build roads, housing, schools, and hospitals for the communities in which they operate, or they compensate for the lack of effective regulation by launching business-led soft-law initiatives. In consequence, corporations often replace governments and hence face social expectations that typically would be placed on the government.

3. Governments cannot address social problems beyond national boundaries: Financial markets, climate change, or the Internet are new social spaces that no single government can control alone. Rather, these spaces are often influenced and governed by businesses. Consequently, the public expects businesses to address climate change, internet privacy or uncontrollable financial markets as a natural consequence of the global reach of these problems.

All three developments have led to a situation where businesses find themselves facing societal expectations that are similar to those usually reserved for political authorities. An increasing number of business firms are confronted with such regulatory gaps, that is, contexts where social and environmental standards are low or not enforced by governmental authorities (Reference Matten and CraneMatten & Crane, 2005; Reference Scherer and PalazzoScherer & Palazzo, 2007). Based on the observation that corporations in such contexts do not just avoid, but jointly with actors from civil society, governments and international organizations, increasingly ‘fill’ regulatory gaps, a conceptualization of CSR has been developed that promotes a view of corporations as political actors. In this context, one of the most notable conceptions addressing the evolving globalization of CSR has been promoted under the label of ‘political CSR’ (e.g. Reference Scherer and PalazzoScherer & Palazzo, 2007). Political CSR, in a nutshell, assumes a broad, potentially global sphere of influence of corporations and assigns them responsibility for those environmental and social externalities to which they are socially connected – that is, for problems ‘to which [corporations] contribute by their actions and … from which they themselves benefit, and which they have encouraged or tolerated through their own behaviour’ (Reference Scherer and PalazzoScherer & Palazzo, 2011, p. 913).

Corporations are urged, for instance by NGOs, to proactively engage in self-regulatory activities which provide specific norms and guidance in relation to global social and environmental problems. For example, globally operating firms are expected to ensure labour rights of workers in distant factories, or to uphold environmentally friendly means of production at the locations where they source raw materials. By engaging in matters hitherto regulated by the state, corporations become increasingly politicized, which means that a strict division of labour between private business and nation states is blurring (Reference Matten and CraneMatten & Crane, 2005). To overcome the democratic deficit inherent in such political engagement of private actors, corporations need to enter into a dialogue with a variety of stakeholders. In short, in political CSR ‘corporate attention and money’ are redirected to ‘societal challenges beyond immediate stakeholder pressure’. Moreover, decision-making processes need to reflect the interests of civil society and those affected by their actions, all of which calls for a democratization of business conduct (Reference Scherer and PalazzoScherer & Palazzo, 2007: p. 1115).

1.6 Multiple Actors Enter the CSR Arena

What do these more theoretical arguments and the notion of political CSR imply for those actors that have entered the field? As we will see, next to businesses themselves, multiple players influence and give direction to what CSR entails and what businesses need to do to address CSR strategically. All of these actors have a certain agenda and interests they represent and pursue, and shape how CSR is understood and practised by corporations. They can be categorized into five groups of actors: international organizations, civil society organizations, business-driven self-regulatory initiatives, cross-sector MSIs, and governments.

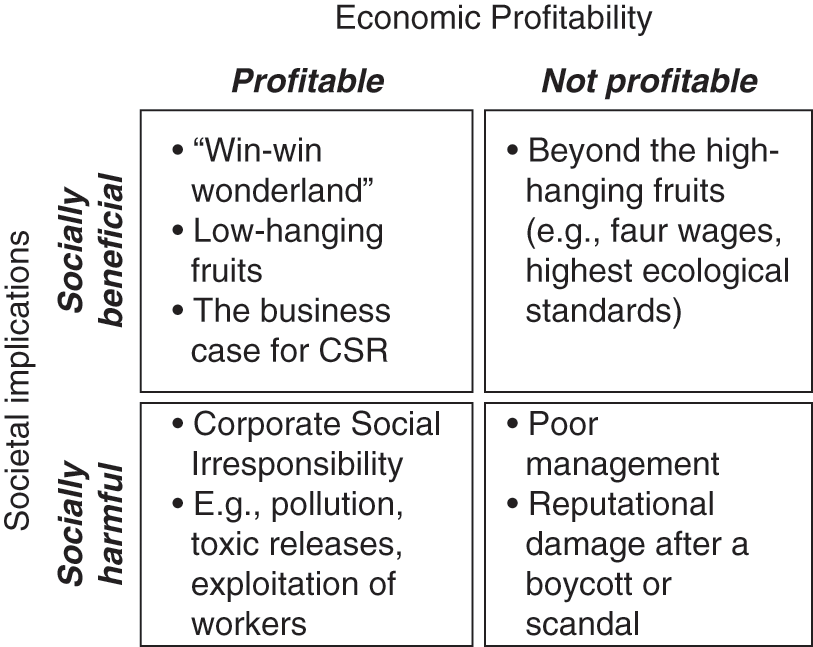

First, we can observe that international organizations play an important role. This includes the United Nations (UN), the OECD, the ILO and the World Bank, all of which have embarked on the CSR agenda and have proposed ideas and policies that generally aim to establish global rules for private actors, so-called soft law. One of the most famous CSR initiatives that deserves special attention and which emerged under the umbrella of an international organization, the UN, is the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC).

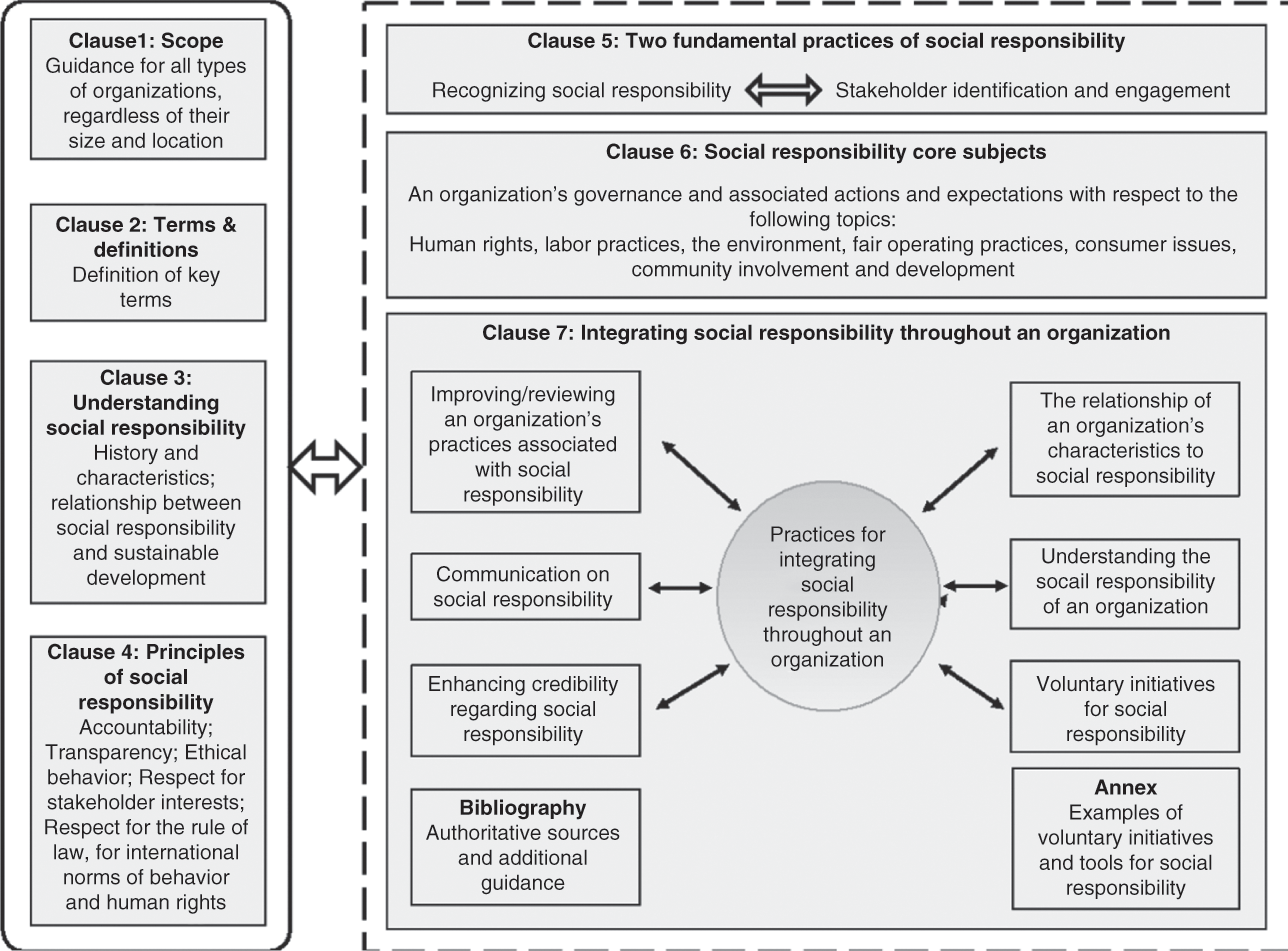

Back in 1999 at the World Economic Forum, then Secretary-General of the UN Kofi Annan announced a ‘Global Compact’ to invite business firms around the globe to work together for sustainable development. Less than a year later, the UN Global Compact Office was founded to promote responsible business practices among the global business community.Footnote 9 By 2019, it became the world’s largest CSR initiative with about 13,000 members in more than 170 countries bringing together stakeholders from the private sector, civil society, academia, and governments. According to its website the UNGC is a ‘call to companies to align strategies and operations with universal principles on human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption, and take actions that advance societal goals’ such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as well as report on their implementation. The goals of the UNGC rest fundamentally on the idea of CSR being about how the money is made. The UNGC suggests that CSR starts with a company’s value system and by incorporating the ten principles of the UNGC into strategies, policies and procedures, and establishing a culture of integrity. This means operating in ways that, at a minimum, meet fundamental responsibilities in the areas of human rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption. Responsible businesses enact the same values and principles wherever they have a presence and know that good practices in one area do not offset harm in another. The ten principles are universal, as they are derived from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the ILO’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, and the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (see Table 1).

Table 1: The ten principles of the UNGC.

| Human rights | |

| Principle 1 | Businesses should support and respect the protection of internationally proclaimed human rights; and |

| Principle 2 | make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses. |

| Labour | |

| Principle 3 | Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining; |

| Principle 4 | the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour; |

| Principle 5 | the effective abolition of child labour; and |

| Principle 6 | the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. |

| Environment | |

| Principle 7 | Businesses should support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges; |

| Principle 8 | undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility; and |

| Principle 9 | encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies. |

| Anti-corruption | |

| Principle 10 | Businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery. |

These principles are important for understanding the scope of CSR as for many business firms they serve as the ‘moral compass’ that guides companies and other stakeholders in setting the agenda. The principles are helpful because they point out the main areas in which regulatory gaps can occur and to which a company may be socially connected through its supply chain. We will get back to the UNGC throughout this Element, for instance when discussing the implementation of CSR principles in core business processes and procedures in Section 3, but also in Section 4 when we critically examine some pitfalls and challenges linked to the way the UNGC is structured.

Second, civil society organizations have been putting significantly more pressure on corporations to act socially and environmentally responsible. NGOs operating at a local or global level aim to police corporations where governments fail to do so. A famous example of a globally known NGO is Greenpeace. The main objective of this NGO is to safeguard the natural environment and raise awareness of issues such as climate change and how the private sector might either accelerate or mitigate this problem. Another well-known NGO is Amnesty International, working for the promotion of human rights around the globe. Often, the strategies of NGOs include ‘naming and shaming’ irresponsible behaviour of businesses. NGOs target firms through campaigns or call for product boycotts when certain very unsustainable actions have been detected, such as Greenpeace’s campaign against Nestlé’s alleged destruction of the rainforest in Borneo. Other NGOs, such as the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) are less confrontational and seek strategic partnerships with specific MNCs in order to address a problematic issue. WWF and The Coca-Cola Company are for instance engaged in a partnership to help conserve the world’s freshwater resources.

Third, we can observe a steady increase in the number of self-regulatory initiatives formed by corporations and explicitly addressing various CSR challenges. Through these initiatives, the private sector and corporate members take on quasi-governmental roles and develop rules and procedures to regulate, for instance, working conditions in the textile industry (see the earlier example of the Accord in Bangladesh). Famous examples include the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and the Business Social Compliance Initiative (BSCI). The WBCSD for instance is a CEO-led global advocacy institution of around 200 MNCs to advance knowledge and share best practices of business involvement in sustainable development.

Fourth, many cross-sector MSIs have emerged that have overlapping objectives with self-regulatory initiatives by businesses, but with an important difference: they include not only private sector members, but are open also to members from different civil society groups. MSIs are thus more democratic than self-regulatory initiatives and are guided by the principle of equal participation. The FSC is one of the most prominent examples that tackles a global regulatory gap, namely the protection of forests by avoiding deforestation and promoting sustainable forestry. The FSC demonstrates how business decisions became embedded in a context of democratic governance and problem-solving by bringing not only corporations but also NGOs and multiple civil society groups to the table. This includes well-known corporations such as IKEA, Home Depot, and OBI, environmental NGOs such as WWF or Greenpeace, but also many smaller local human rights activist and indigenous peoples groups.

Together, FSC members developed a set of principles and criteria for the sustainable management of forests that applies on a global basis, including monitoring and certification. Many timber products worldwide feature the FSC certification logo and signal to consumers that the materials used in the product stem from a sustainably managed forest. Reference Scherer and PalazzoScherer and Palazzo (2007) suggest that the FSC can be considered one of the most advanced concepts reflecting a political understanding of CSR. This is because the FSC illustrates some of the key aspects of a politically embedded corporation. In fact, corporate FSC members address an important environmental challenge that national governments are not able or willing to tackle alone. Self-regulation takes place in a broad process of democratic will formation in collaboration with civil society actors. The independent third-party certification enforces a democratic control of corporate activities.

Fifth, while we have emphasized the emergence and prominent role of non-government players in the CSR landscape and governmental influence shrinking relative to that of the private sector and civil society, governments still play an important role and have been reacting to these developments in different manners (Reference Kourula, Moon, Salles-Djelic and WickertKourula et al., 2019). This is interesting, as most of the discussion on political CSR was based on the assumption that governments generally retreat and become less important as actors shaping the CSR agenda. However, particularly in recent years, various governmental agencies of nation states have aimed to ‘reclaim’ some of the lost territory by re-entering the CSR playing field. On the one hand, demands for social responsibilities of businesses have become more demanding when looking at how CSR is defined by the public. In 2001, the European Commission proposed its first definition of CSR. In a Green Paper,Footnote 10 it is stated that CSR is ‘a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis’. Two components of this definition are important. First, the definition refers to social and environmental concerns, while not being very precise about what those actually are. Second, the definition emphasizes that this should happen on a voluntary basis. As the updated definition of the European Commission released in 2011Footnote 11 shows, public expectations about the scope of CSR became much more demanding: ‘CSR is the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society. To fully meet their social responsibility, enterprises should have in place a process to integrate social, environmental, ethical, human rights and consumer concerns into their business operations and core strategy in close collaboration with their stakeholders’.Footnote 12 While the voluntary nature of CSR is no longer emphasized, the range of issues under the umbrella of CSR is significantly expanded and their connection to core business operations is made explicit.

On the other hand, governments are re-entering the game by trying to push forward several new laws and regulations in light of the failure or lacking effectiveness of many market-based initiatives. This reflects a shift back from the ‘soft-law’ (i.e. voluntary and non-binding) approach that was praised by the private sector back to ‘hard law’ (i.e. non-voluntary and binding). A central argument of governments to introduce hard law was that many of those voluntary initiatives have been ineffective in actually solving or at least mitigating some of the most severe social and environmental problems. Thus, while most of the attention of both researchers as well as companies was on the ‘privatization’ of governance and the emergence of private self-regulation (i.e. shifting authority away from governments to private actors and civil society), recently the trend seems to have been reversed (see Kourula et al., 2019 for an overview). For instance, linked to the case of conflict minerals we discussed earlier, the EU, the USA and other nations have passed laws about the handling of and reporting on conflict minerals, putting an expanded set of demands on businesses. Likewise, legislation about social and environmental reporting is on its way in the EUFootnote 13 and other countries, obliging companies to publish yearly reports about the progress they have made with regard to their CSR objectives. The US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act even allows the US government to sue corporations (even non-US ones) for offering or accepting bribes in another country. These efforts show that governments are (re-)entering the CSR arena and are likely to significantly shape the future agenda much more than they did in the past.

1.7 Defining CSR

After having discussed these developments and players in the CSR arena, we will now develop a definition of CSR. Given the complexity of the social, environmental and ethical challenges that lie ahead, and the multiplicity of actors involved, it seems that finding a one-size-fits-all definition for CSR is impossible. Indeed, scholars have struggled with this ever since the term CSR emerged. In a seminal study, Reference Matten and MoonMatten and Moon (2008: p. 405) have argued that there are at least three reasons for this complication: first, CSR is an essentially contested concept that is defined (and applied) differently by different groups of people in different contexts. It might of course be that this ambiguity about appropriate terminology is the reason why the idea of CSR has been successful. If stakeholders cannot agree upon the meaning of CSR and specify its scope precisely, business firms could easily take advantage of this by selectively framing CSR against those issues areas that they can conveniently address. This relates particularly to the low-hanging fruits where a company might for instance argue that CSR is mainly about things such as eco-efficiency. What is nevertheless a uniting feature of the label CSR is that stakeholders – even if they disagree on its precise meaning – have for decades concurred on the importance of debating the role of business in society.

Second, CSR overlaps with other concepts that describe the business–society relationship, such as business ethics, corporate sustainability, or corporate citizenship. While different and important nuances exist and need to be acknowledged (e.g. business ethics is generally concerned with questions of right or wrong; sustainability is generally concerned with systemwide ecological implications), all of these concepts have at their root the fundamental question of the role of business in society (see Reference Bansal and SongBansal & Song, 2017 for an overview). Finally, as with many other forms of business organization and governance, CSR is a dynamic phenomenon. What counts as an issue relevant to the CSR debate changes over time, as new problems emerge and formerly novel practices become routine. Such change is for instance evident from the shift in the scope of CSR from how the money is spent to how the money is made.

Despite these challenges it is important to have an, albeit broad, working definition for CSR. In this Element, we therefore define CSR as follows:

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is an umbrella term to describe how business firms, small and large, integrate social, environmental and ethical responsibilities to which they are connected into their core business strategies, structures and procedures within and across divisions, functions as well as value chains in collaboration with relevant stakeholders.

This definition emphasizes several important characteristics of CSR. First, the definition does not emphasize that CSR is a voluntary concept. Many prominent definitions point out the voluntary character of CSR with regard to actions beyond the law. What we can observe, however, is that in the global business environment CSR became a de facto requirement and new laws such as those we reviewed are emerging. Moreover, CSR has become a necessary component of business conduct to ensure legitimacy and a firm’s social licence to operate. Even the European Commission removed the word voluntary from its new definition of CSR to emphasize that CSR is a response to societal expectations. Hence, it is nowadays hard to find firms without any sort of CSR activities, often based on industrywide standards. In particular, what we will discuss in Section 2 is that the development towards a mainstream management concept is accompanied by the circumstance that CSR has been pushed much beyond purely voluntary actions.

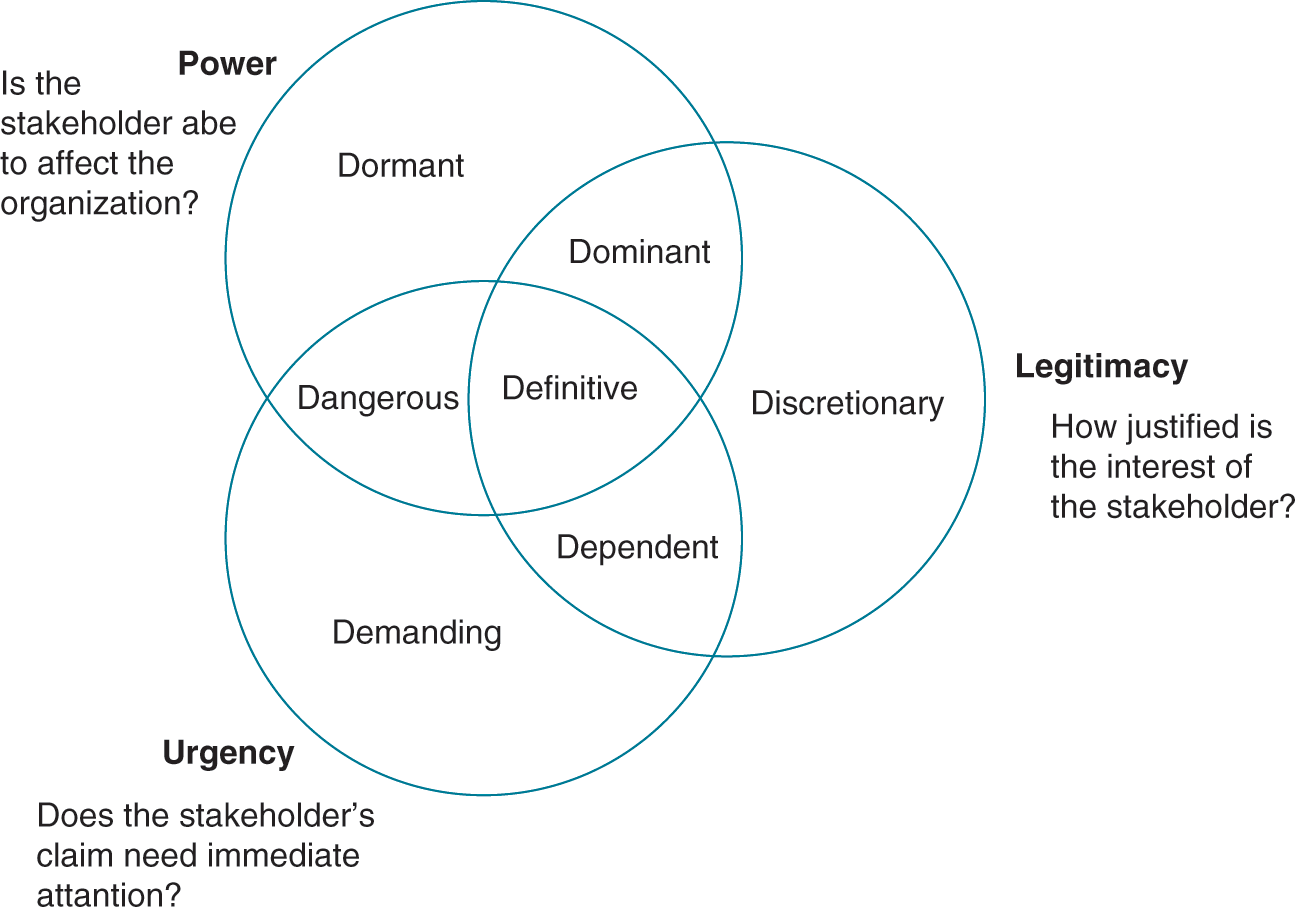

Second, CSR is a multi-actor concept and inherently stakeholder-driven. Business firms are seen as embedded in a web of stakeholder relations and confronted with oftentimes diverging interests to which they react in one way or another. CSR thus involves considering a range of interests and impacts among a variety of different stakeholders other than just shareholders. The assumption that firms have responsibilities to shareholders is usually not contested, but the point is that because corporations rely on various other constituencies such as consumers, employees, suppliers, and local communities in order to survive and prosper, they do not only have responsibilities, or ‘fiduciary duties’, to shareholders. While many disagree on how much emphasis should be given to shareholders in the CSR debate, and on the extent to which other stakeholders should be taken into account, it is the expanding of corporate responsibility to these other groups that characterizes much of the essential nature of CSR.

Next, we explicitly did not use the term ‘corporation’, but ‘business firms, large and small’ in our definition. This is to highlight that CSR is not an idea restricted to large multinational corporations. While the term has emerged in mainstream discussions about the role of business in society and will hence be used for the sake of congruence, it should not be forgotten that also small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have responsibilities towards society, and that they might be connected to the same social and environmental challenges as large firms (Reference WickertWickert, 2016). While SMEs are generally defined as not having more than 250 employees, they make up the vast majority of businesses in nearly every economy worldwide. In fact, often up to 99 per cent of all registered businesses are SMEs. Research has pointed out that the CSR activities of smaller firms are different to those in large firms in a number of ways (Reference Baumann-Pauly, Wickert, Spence and SchererBaumann-Pauly et al., 2013; Reference Wickert, Scherer and SpenceWickert et al., 2016). Typically, owner-managers and their values and beliefs play a more important role than external influences or instrumental considerations to which large firms are more exposed. CSR in SMEs is more informal and more connected to local communities and immediate stakeholders. At the same time, SMEs as much as MNCs are in many cases challenged by similar problems such as working conditions in their suppliers’ factories. For instance, in the textile industry, many SMEs source from exactly the same factories that MNCs do, and while being small might evoke a different way of addressing a social or environmental problem, the social connection is the same. The same basic principles about human rights equally apply to all corporations regardless of their size or the geographic location of their activities.

Lastly, CSR must be understood as a multidimensional construct. That is, even though it includes the word ‘social’, CSR is generally understood as equally being concerned about environmental and ethical issues. This reflects the internationally agreed view that the responsibilities business firms have towards society encompass four key issue areas: human rights (as determined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), labour rights (as stated in the ILO’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work), environmental principles (as agreed upon in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development), as well as anti-corruption (as stated in the UN Convention Against Corruption). These four issue areas that are also reflected in the ten principles of the UN Global Compact should not be seen as an exhaustive and definite list of responsibilities. Rather, they form a moral compass, outlining minimum standards when discussing what should be expected from business firms. We will discuss in the final section of this Element how newly emerging issues such as the SDGs, but also the digitalization of the economy, bring about a set of new issues that will most likely shape the agenda and content of CSR over the next decades.

1.8 Summary

In this section we have addressed the fundamental question of what CSR is and which social, environmental and ethical issues it entails. Fundamentally, CSR is about how companies earn their profits and not how they distribute them. Further, we have shown where those issues can appear along global value chains, classifying them into low- and high-hanging fruits. We have argued that globalized production networks are a key factor that stretches the sphere of business responsibility towards those issues, impacts and consequences with which they are socially connected. The changing relationship between governments and private business firms leads to a fundamental shift in how social and environmental responsibilities are understood. To address these CSR challenges in the context of globalization, scholars have proposed a political understanding of CSR that brings along a range of actors into the arena and with which business firms are urged to collaborate in various ways. We have ended the section with a broad definition of CSR. In the next section, we will elaborate the motives that businesses have to engage with CSR and address those issues we have outlined. We will argue that there are ethical, instrumental and stakeholder-driven motives for CSR that bring about various challenges in how CSR is implemented in strategies and procedures.

2 Why Would Business Firms Engage in CSR? Motives and Drivers Beyond the Business Case

The objectives of this section are:

To address the question of why businesses are motivated to engage in CSR, based on ethical, instrumental, and relational considerations.

To outline the ethical driver for CSR that is based on moral considerations and the understanding of CSR as ‘the right thing to do’.

To introduce the business case for CSR as an instrumental driver that is based on the principle of ‘doing well by doing good’; and to outline two important fallacies of this approach: the ethical fallacy and the managerial fallacy of the business case for CSR.

To illustrate the relational driver for CSR that generally aims to ensure a firm’s licence to operate and societal legitimacy. This driver is based on pressures external to the firm stemming from stakeholders and the institutional environment and has become the most important motive that explains why firms engage in CSR.

In Section 1, we unfolded the scope of CSR by discussing the various social, environmental and ethical issues that fall under the umbrella of CSR. We explained how those issues have expanded over the last few decades from philanthropic and charitable actions towards the ‘high-hanging fruits’ that appear in businesses’ core operations as well as their global value chains and production networks, such as human rights violations, modern forms of slavery, or climate change and environmental pollution. In Section 2, we will expand on this by addressing the fundamental question of why firms would engage in CSR in the first place. We will delve into the various and dynamic motives that explain CSR engagement. Following the literature, we will divide our analysis into three broad motives, namely ‘ethical’, ‘instrumental’, and ‘relational’, all of which influence managerial decision-making for CSR to varying degrees.

2.1 Ethical Motives for CSR

The ethical motive for CSR generally suggests that business firms take up responsibility because it is ‘the right thing to do’ from a moral point of view. This approach marks the historical beginning of the debate about what the social responsibilities of businesses are. Discussions of philanthropic responsibilities of business owners date back to the days of early industrialists such as Rockefeller and Carnegie in the USA, or Alfred Krupp in Germany, who donated large portions of their wealth to charitable causes such as education, healthcare and culture. Recently, the issue has resurged in light of modern-day philanthropists such as Mark Zuckerberg with his Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, or Bill Gates with his Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Critics argue that rising influence of individuals on public welfare undermines democracy and puts the provision of many public services at the discretion of those philanthropists who are not legitimated by public vote. While we have argued that philanthropy should rather be considered an outdated approach to CSR because it is not based on the premise of how the money is made, rather than spent, it nevertheless stood at the beginning of an important discussion that led to the development of the contemporary understanding of CSR.

The birth of what we now understand as CSR is generally associated with the works of Howard R. Bowen and his seminal book The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman from the early 1950s (Reference Bowen1953). Bowen set forth an initial definition of what came to be known as CSR: ‘It refers to the (ethical) obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society.’ Thus, the definition is explicitly linked to the moral obligations of businessmen beyond economic performance. At the same time, it acknowledges that what is morally right and wrong is largely determined by those external societal expectations which still matter a great deal today. Business responsibility then is the ‘social consciousness’ of managers who are responsible for the consequences of their actions in a sphere wider than what is covered by their profit-and-loss statements. Importantly, at the time the focus was largely on individual responsibility of presumably male decision-makers in organizations and their ability for informed ethical judgement, rather than on looking at a company as a whole. This idea of personal responsibility was influential in the early days of CSR and has been picked up in the literature since then, for instance by outlining the distinct personal values of managers as drivers for CSR (e.g. Reference Hemingway and MaclaganHemingway & Maclagan, 2004).

However, discussions about the ethical motive for CSR soon moved to the organizational level of analysis. Influential in this regard is the work of Reference CarrollArchie B. Carroll (1991) and his ‘pyramid of CSR’ that conceptualizes the management of organizational stakeholders based on moral justification. Carroll depicted a four-stage pyramid structure of CSR, in which economic responsibilities (‘be profitable’) lay at the foundation of all business behaviour. On top of that, and somewhat narrower as we move up the pyramid, were legal responsibilities (‘obey the law’). Carroll argued that the law reflects society’s codification of right and wrong, and businesses were obliged to play by the rules of the game – based on the important assumption that governments are actually able to enforce those rules of the game. Further up were ethical responsibilities (‘be ethical’) that comprised businesses’ obligation to do what is right, just and fair, and to avoid harm to stakeholders. On top of the pyramid, markedly the narrowest spot, came philanthropic responsibilities (‘be a good corporate citizen’) where businesses should contribute resources to their communities to improve the overall quality of life and welfare.

The pyramid of CSR also has been very influential in shaping the CSR debate, but holds a number of important limitations. First, with its focus on ethical responsibilities it pays only limited attention to the socio-cultural heterogeneity of what is right and wrong in the global context, as well as how to address more systemic problems and structural injustices linked to the nature of capitalism. Second, with its focus on philanthropy it is rooted in the ‘how the money is spent’ logic that fails to address how CSR shall be implemented into core business operations and strategies. Third, due to the focus on legal responsibilities and the associated liability logic, it does not address the idea of social connection needed when conceptualizing CSR for globalized supply chains and production networks. Fourth, with its focus on economic responsibilities it falls short in cases where there is no business case for CSR, a fundamental problem that we will discuss later in this section.

Reference Crane and MattenCrane and Matten (2015) have taken these discussions about ethical motives further. They have argued that beyond the feeling of personal responsibility for the right thing to do, businesses also bear an ethical responsibility because they often cause social and environmental problems and hence ought to solve those problems. This, in essence, also reflects Young’s social connection logic (Reference YoungYoung, 2004). However, while the social connection approach is morally grounded, companies would probably accept this logic because it might either be profitable to ensure a sustainable supply chain, or more likely because they face substantial stakeholder pressure to behave responsibly.

From an ethical point of view, firms are also embedded in society and thus depend on the contribution of many stakeholders (e.g. employees, suppliers, consumers) and not just shareholders to run their business. Therefore, they have a moral duty to consider the interests and goals of these stakeholders. Next, businesses, in particular large firms, are powerful social actors who have access to substantial resources, so that they ought to use their power and resources responsibly in society. For instance, some of the world’s largest firms such as Microsoft, Walmart, Toyota or Volkswagen (and more and more tech firms as well as Chinese corporations) now have revenues higher than the gross domestic product of many countries, justifying the argument that with greater power comes greater responsibility.

Beyond the power argument, because all business activity has some sort of societal (social, environmental or ethical) impact, firms ought not to escape responsibility for those impacts, whether they are positive, negative or neutral. Thus, there is a moral responsibility to manage one’s externalities – that is, the impacts of economic transactions borne by those other than the parties engaging in the transaction. Business activity commonly leads to a variety of problematic externalities other than through the provision of products and services, the employment of workers, or advertising techniques. Business ethicists therefore attribute a moral responsibility to businesses that emerges due to negative externalities such as pollution, resource depletion or community problems, specifically if these are not adequately dealt with by governments.

In summary, the ethical responsibilities of businesses generally consist of normative guidelines that depict what companies should do beyond economic and legal expectations. Discussions in the literature about ethical motives for CSR continue based on diverse perspectives and moral philosophies such as virtue ethics, Kantian duty ethics, or Rawlsian justice theory. However, as we will show, ethics alone is not a very strong motivation for businesses to engage in CSR, and we would find few companies to behave responsibly simply because it is the right thing to do. Rather, other motives that are based on a much stronger business calculus have taken over.

2.2 Instrumental Motives for CSR – The Business Case

The meta-narrative that pervades much of the debate around CSR is encapsulated in the slogan ‘doing well by doing good’. The idea is that being socially or environmentally responsible ultimately pays off and thus contributes to the financial bottom line of a firm. There are four basic factors explaining why CSR can enhance long-term revenue and can create a competitive advantage for firms, thus providing an instrumental motive for CSR (for overviews see, for instance, Reference Hawn and IoannouHawn & Ioannou, 2016; Reference McWilliams and SiegelMcWilliams & Siegel, 2001; Reference Vishwanathan, van Oosterhout, Heugens, Duran and van EssenVishwanathan et al., 2019).

First, with regard to internal audiences, CSR programmes are said to attract talent, increase employee engagement, motivation and satisfaction, and reduce employee retention, all of which would ultimately contribute to job performance and productivity. For instance, CSR is considered to be a key motivator for millennials when considering a place of work. Second, with regard to external audiences, CSR programmes can enhance trust and support of consumers and investors in products and brands. This allows for creating a favourable reputation, increased sales, and the ability to charge a price premium for socially responsible and sustainable products. Third, with regard to operations, CSR programmes can help to reduce costs. For instance, the implementation of eco-efficiency or recycling measures leads to energy savings and reductions in waste and raw materials used. Fourth, CSR can also allow more effective management of environmental and social risks. For instance, voluntarily committing to a CSR initiative, such as the UNGC, may forestall legislation and ensure greater corporate independence from government. In the aftermath of the Rana Plaza factory collapse in 2013 in Bangladesh that we illustrated in Section 1, many Western retailers were met with calls to ensure worker safety and formed self-regulatory industry initiatives that also helped to prevent negative publicity.

Based on the idea that there is a business case for CSR, a myriad of studies has explored the CSR–financial performance link both theoretically (why would CSR pay off?) and empirically (what is the actual contribution of CSR activities to the financial bottom line?). In one of the most influential theoretical approaches to explain the instrumental motive for CSR, Reference McWilliams and SiegelMcWilliams and Siegel (2001) developed a supply and demand model for CSR. Based on cost–benefit analysis, this model helps managers to determine the optimal level of CSR a firm should supply in order to maximize financial performance while at the same time satisfying stakeholder demands for CSR (e.g. consumers, employees, community, shareholders). The demand for CSR is affected by factors such as the price premium for products with CSR attributes, consumer awareness, preferences and available income. The supply of CSR actions is influenced by higher costs for labour, machinery and other resources such as materials or services that have higher levels of CSR. CSR attributes may include fair-trade produce such as coffee or tea, non-animal-tested cosmetics, pesticide-free cultivation, dolphin-safe tuna and alternative-fuel engines. CSR actions include such things as recycling, pollution abatement, progressive work practices, and support for local social services. Grounded in the resource-based view of the firm, CSR could create a sustainable competitive advantage if these attributes and actions are founded on resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable (Reference BarneyBarney, 1991), as this allows for product differentiation. In sum, Reference McWilliams and SiegelMcWilliams Siegel (2001) suggest that managers should treat decisions regarding CSR precisely as they treat all other investment decisions.