Status motives underpin many political psychological explanations for attitudes and behaviors (Craig and Phillips Reference Craig, Phillips, Huddy, Sears, Levy and Jerit2023; Pérez and Vicuña Reference Pérez, Vicuña, Huddy, Sears, Levy and Jerit2023). A well-known example concerns many White Americans’ negative reactions to threats to their station, observed in responses to demographic change. This perceived status change paradigm, most prominently introduced by Craig and Richeson (Reference Craig and Richeson2014a, b; see also Outten, Schmitt, Miller, and Garcia Reference Outten, Schmitt, Miller and Garcia2012), features a mock news article or press release describing Census projections of demographic change and the United States becoming a majority–minority country. This information leads some Whites to express greater concern with the group’s social and cultural status, support conservative policy positions and candidates, and report more anti-minority attitudes (see Craig, Rucker, and Richeson Reference Craig, Rucker and Richeson2018 for a review; but see Neuner and Hechter Reference Neuner and Hechter2023 for a qualification). Further, studies find demographic shift information can change attitudes among non-Hispanic minorities (e.g., Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2018) and, recently among Whites, relates to attitude change differently for liberals and conservatives (Brown, Rucker, and Richeson Reference Brown, Rucker and Richeson2022).

But while scholars have successfully, and repeatedly, manipulated perceived status change, the typical approach faces at least two challenges. Presently, respondents view a figure on US population trends and a paired text discussion highlighting the United States becoming a majority–minority nation. Yet, as a recent review of this research agenda’s results notes “it is not obvious which forms of threat may be elicited in different hierarchy-challenging contexts” (Craig and Phillips Reference Craig, Phillips, Huddy, Sears, Levy and Jerit2023, 870). How people respond to general information on demographic change may not correspond to their reactions about racial shifts focused on electoral politics and political power or entertainment media and cultural influence.

Attention to different “hierarchy-challenging contexts” points to the second, related limitation in existing designs: evidence is unclear regarding the specific intergroup threats the present paradigm elicits and how these influence other outcomes. Scholars find simultaneous changes on distinct constructs: Whites’ concerns with being prototypical Americans, competing for scarce resources, and preserving cultural symbols and beliefs (e.g., Brown, Rucker, and Richeson Reference Brown, Rucker and Richeson2022). As Craig and Phillips (Reference Craig, Phillips, Huddy, Sears, Levy and Jerit2023, 870) note, treatment effects conveyed via myriad channels cloud our ability to explain precisely native majorities’ responses (see also Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Lee, Oaxaca, Cervantes, Rodríguez, Lam and McFall2024). For instance, precisely identifying the mechanism matters for unpacking why exposure to racial shift information can increase prejudice (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014a) and conservatism on racial and nonracial policies (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014b). These shifts could come from realistic threats, symbolic threats, multiple identity threats, or combinations thereof. Clarifying these channels requires pinpointing which threat(s) specifically information on a racial shift produces that leads to observed outcomes (e.g., Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Abascal Reference Abascal2023; Fouka and Tabellini Reference Fouka and Tabellini2022), with results helping advance debates about the relevance of symbolic versus realistic concerns in driving native majorities’ responses to demographic change (e.g., Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Newman and Malhotra Reference Newman and Malhotra2019).

We evaluate whether the hierarchy-challenging context considered matters for the evidence scholars have marshaled around White responses to demographic change. Based on published results, we hypothesize that non-Hispanic Whites exposed to information on changing demographics will, compared to a placebo condition: report increased perceptions of status change (H1a) and greater levels of status threat (H1b), hold more conservative racial and non-racial policy preferences (H2), and express more negative views of racial and ethnic minorities (H3) (Craig, Rucker, and Richeson Reference Craig, Rucker and Richeson2018). Further, given partisan sorting predisposing White Democrats to favor racial and ethnic minorities and White Republicans to disfavor (Engelhardt Reference Engelhardt2021; Jardina and Ollerenshaw Reference Jardina and Ollerenshaw2022; Ollerenshaw and Jardina Reference Ollerenshaw and Jardina2023), we probe political affiliation’s moderating effects (H4), extending recent work (Brown, Rucker, and Richeson Reference Brown, Rucker and Richeson2022).

We consider evidence for each hypothesis across three separate hierarchy challenges. The first focuses on Whites’ numerical population majority, the typical manipulation. The second challenges Whites’ advantaged political position. By targeting changing political power and influence, this challenge should make more salient realistic threat concerns. The third challenges Whites’ elevated cultural position, pinpointing shifting control over what it means to be American and making salient symbolic threat. Clarifying what the racial shift treatment manipulates addresses important blind spots regarding whether White status loss universally instills status threat (H1b) and whether evidence for a general conservative policy turn (H2) and increased racial prejudice (H3) among some Whites occurs for information on status change of any sort.

Data

We contracted with Bovitz to sample 2100 non-Hispanic White Americans with quotas matching Census benchmarks on age, sex, and region.Footnote 1 Data collection ran July 8–16, 2024, with responses recorded in Qualtrics. This sample accomplishes two goals. First, our interest in whether evidence for each hypothesis varies by hierarchy-challenging context motivates comparing treatment effect sizes. Our sample provides over 80% power to detect differences in treatment effects across conditions larger than d =.20 at the α = .05 level for H1–H3 (Lakens Reference Lakens2017). Second, testing moderated treatment effects requires large samples (H4). Given an expected crossover interaction (Brown, Rucker, and Richeson Reference Brown, Rucker and Richeson2022), and directional expectations (e.g., those on the right respond negatively to change), we preregistered one-tailed tests of H4. Our sample size provides over 80% power to detect a significant interaction effect at the α = .05 level (Sommet et al. Reference Sommet, Weissman, Cheutin and Elliot2023).

After answering pretreatment items, including a two-item ideology measure and public figure evaluation grid, respondents were randomly assigned to one of four treatments: the population racial shift focusing on Census forecasts of population change, the political racial shift describing projections of the US presidential electorate, the cultural racial shift discussing trends in the US media and entertainment landscape on growing diversity in casts and viewership, and a placebo discussing geographic mobility. All racial shift treatments discuss changes in Whites’ dominant position but challenge the racial hierarchy in different contexts and were pretested to uniquely manipulate expectations about where their status will change. Posttreatment respondents first answered factual and subjective manipulation checks, with the former used to ensure respondents understood treatment content and the latter used to ensure each treatment manipulated the intended demographic change perceptions (Kane and Barabas Reference Kane and Barabas2019).

Subsequently, respondents answered four three-item scales previously used to capture status anxiety (Bai and Federico Reference Bai and Federico2021; Brown, Rucker, and Richeson Reference Brown, Rucker and Richeson2022; Danbold and Huo Reference Danbold and Huo2015; Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Ybarra and Bachman1999). One indexes status change perceptions (e.g., “White Americans are losing influence in society due to gains from racial minorities.”), another prototypicality threat (e.g., “Compared to today, 50 years from now what it means to be a true American will be less clear.”), a third symbolic threat (e.g., “The values and beliefs of other ethnic groups regarding work are not compatible with the values and beliefs of my ethnic group”), and the last realistic threat (e.g., “Members of other racial groups are displacing members of my racial group from jobs.”). Scales include two pro-trait items and one con-trait item to address acquiescence bias and were presented in random order.Footnote 2

Participants then completed four separate outcomes, presented in random order, capturing the conservative shift (Craig and Richeson Reference Craig and Richeson2014a, b; Bai and Federico Reference Bai and Federico2021). We measured opinions on nonracial (e.g., “Making access to abortion a constitutionally protected right.”) and racial (e.g., “Increasing the number of border patrol agents along the US–Mexico border.”) policy with 3 items each. We solicited ratings of 6 social and political groups using 101-point feeling thermometers (e.g., “Black Lives Matter,” “Latinos”). We also introduced behavioral intention measures in two domains: politics and personal life. Each domain included four actions, two backlash (e.g., “Put a yard sign up for a candidate who made an insensitive statement about immigrants,” “Boycott a company that employs undocumented immigrants”) and two supportive (e.g., “Vote for a political candidate who vows to fight against racism,” “Buy a friend or family member a book about the unique experiences of people of color”). We created additive indexes for all scales and rescored all variables to run 0–1. These varied outcomes allow us to contrast the conservative shift across treatments in key domains, identifying points of similarity or divergence. Appendix A contains full question wording and treatment text.

Results

Manipulation checks

We first confirmed respondents understood our new treatments. Eighty-eight percent of participants passed the factual manipulation check and evidence indicates the treatments manipulated intended perceptions. All three treatments increased how likely participants thought White people would be a demographic minority in the United States (p < 0.001). But importantly, the population racial shift condition has a uniquely large effect relative to both the control (d = 0.67, p < 0.001) and the other racial shift conditions (political racial shift: d = .43; cultural racial shift: d = .41, p < 0.001). Appendix C contains regression results for these and all reported treatment effects.

All treatments increased the likelihood that participants thought White people would be a minority of US voters (p < 0.001). Our key treatment here, the political racial shift, had a large effect relative to the control (d = 0.66). But while this ranked well ahead of the effect from the cultural racial shift (d = 0.37), the treatment effect did not differ from the population shift condition (d = 0.63, p = 0.548).

Lastly, all three treatments increased how likely participants thought White people would be a minority of actors on TV shows and in movies (p < 0.001). The cultural shift has the largest effect compared to all other treatments (control d = 0.89; population shift d = 0.31; political shift d = 0.37; all p < 0.001).

Status change

We first assess Whites’ beliefs about their changing social status. As Figure 1 shows, all three treatments increased perceptions that they would lose status as racial minorities gain status (p < 0.001). But comparing the treatments, none had uniquely large effects (smallest pairwise p = 0.559; population shift d = 0.33; political shift d = 0.29; and cultural shift d = 0.28). Evidence for H1a – that Whites perceive their status will change – does not depend on the hierarchy-challenging context considered.

Figure 1. Treatment effect on perceived status change. The figure displays raw data, jittered to decrease overlap; box plot with solid line denoting median and box the interquartile range; and a density plot.

However, we find no support for H4–heterogeneity by partisanship or ideology. Moderating treatment assignment by partisanshipFootnote 3 or ideological self-identificationFootnote 4 does not produce the expected crossover interaction for ideological self-identification (smallest p = 0.679) or partisanship (smallest p = 0.875).

Status threat

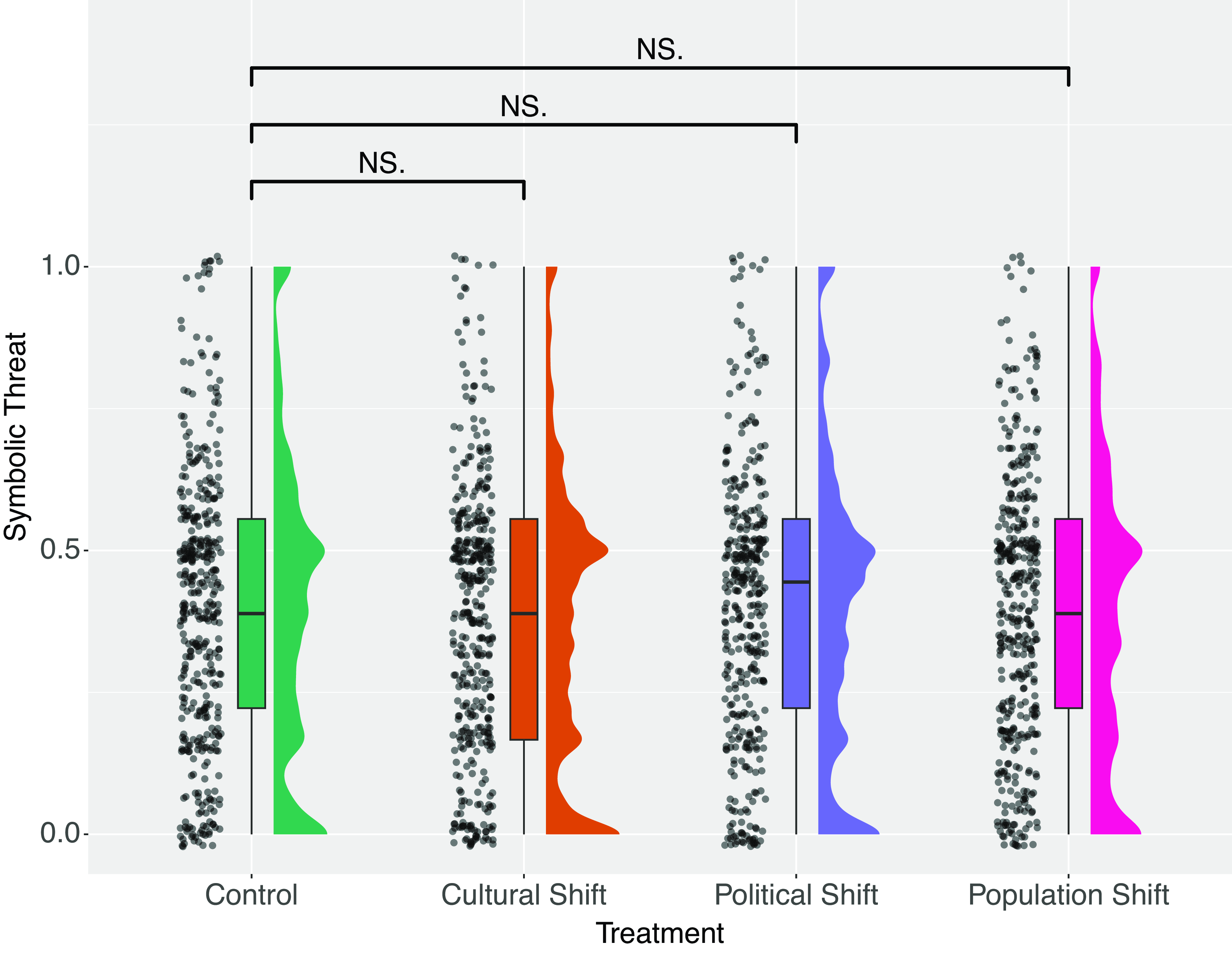

We next probe three status threat responses that research identifies as relevant: symbolic threat, realistic threat, and prototypicality threat.Footnote 5 First, Figure 2 shows that no treatments significantly changed symbolic threat perceptions (smallest p = 0.373), with the largest substantive effect still inconsequential (largest d = 0.06). Figure 3 shows both the cultural and political conditions increased realistic threat (smallest p = .043). But the substantive effects are small (largest d = 0.12) so we don’t make much of them given the p-value and our sample size. Finally, Figure 4 shows insignificant results for prototypicality threat (smallest p = 0.287) with the largest effect size quite small (d = 0.07). We thus conclude we lack evidence for H1b—counter to expectations, racial shift information does not stimulate status threat concerns.

Figure 2. Treatment effect on symbolic threat. The figure displays raw data, jittered to decrease overlap; box plot with solid line denoting median and box the interquartile range; and a density plot.

Figure 3. Treatment effect on realistic threat. The figure displays raw data, jittered to decrease overlap; a box plot with a solid line denoting the median and box the interquartile range; and a density plot.

Figure 4. Treatment effect on prototypicality threat. The figure displays raw data, jittered to decrease overlap; a box plot with a solid line denoting the median and box the interquartile range; and a density plot.

Perhaps the lack of treatment effects comes from sharp, countervailing differences by political commitments as H4 anticipates. We find, however, no support for moderated treatment effects by either partisanship or ideology on any of these outcomes (smallest p = 0.322).

Because prior work established these status threats as mechanisms that produce a conservative shift in attitudes, it is important to consider what null results on these mechanisms mean. As we are adequately powered to detect small effects, our tests are precise (standard errors ≤0.014 for H1b, <0.05 for ideological moderation, and <0.008 for partisan moderation for H4 on variables scaled 0–1). These results furthermore hold not only for the typical treatment in the literature but two new manipulations.

Group attitudes

With no evidence for consistent treatment effects on status threat, perhaps status change underpins the predicted conservative shift. We assess this first by examining attitudes toward racial groups, Black Lives Matter (BLM), and the Alt-Right. As Figure 5 shows, we find no treatment effects. None of the conditions change feelings toward Black (smallest p = 0.315, d ≤ 0.06), Hispanic (smallest p = 0.547, d =≤ 0.04), Asian (smallest p = 0.580, d =≤ 0.03), or White people (smallest p = 0.558, d =≤ 0.04), or BLM (smallest p = 0.249, d =≤ 0.07) or the Alt-Right (smallest p = 0.611, d =≤ 0.03). These precisely estimated effects (standard errors ≤ 0.022), lead us to conclude we lack evidence for H3.

Figure 5. Treatment effects on attitudes toward (a) Black People, (b) Latino People, (c) Asian People, (d) White People, (e) the Alt-Right, (f) BLM.

We also again find no evidence for H4. In no instance does exposure to demographic change foster more pro-minority attitudes among those on the political left and anti-minority/pro-White attitudes among those on the political right as expected (smallest p = 0.118; for White people).

Policy support

We find no support for a conservative shift on policy preferences, outcomes perhaps more easily shifted compared to group evaluations. Figure 6 shows no treatments increased racial (smallest p = 0.186, d ≤ 0.08) or nonracial policy conservatism (smallest p = 0.475, d ≤ 0.04). We thus fail to find support for H2 for any hierarchy-challenging context.

Figure 6. Treatment effect on (a) racial conservative policy support and (b) nonracial conservative policy support.

We also again find no support for H4. Neither ideology nor partisanship affected how the treatment influenced participantsʼ policy preferences (smallest p = 0.094).

Participation

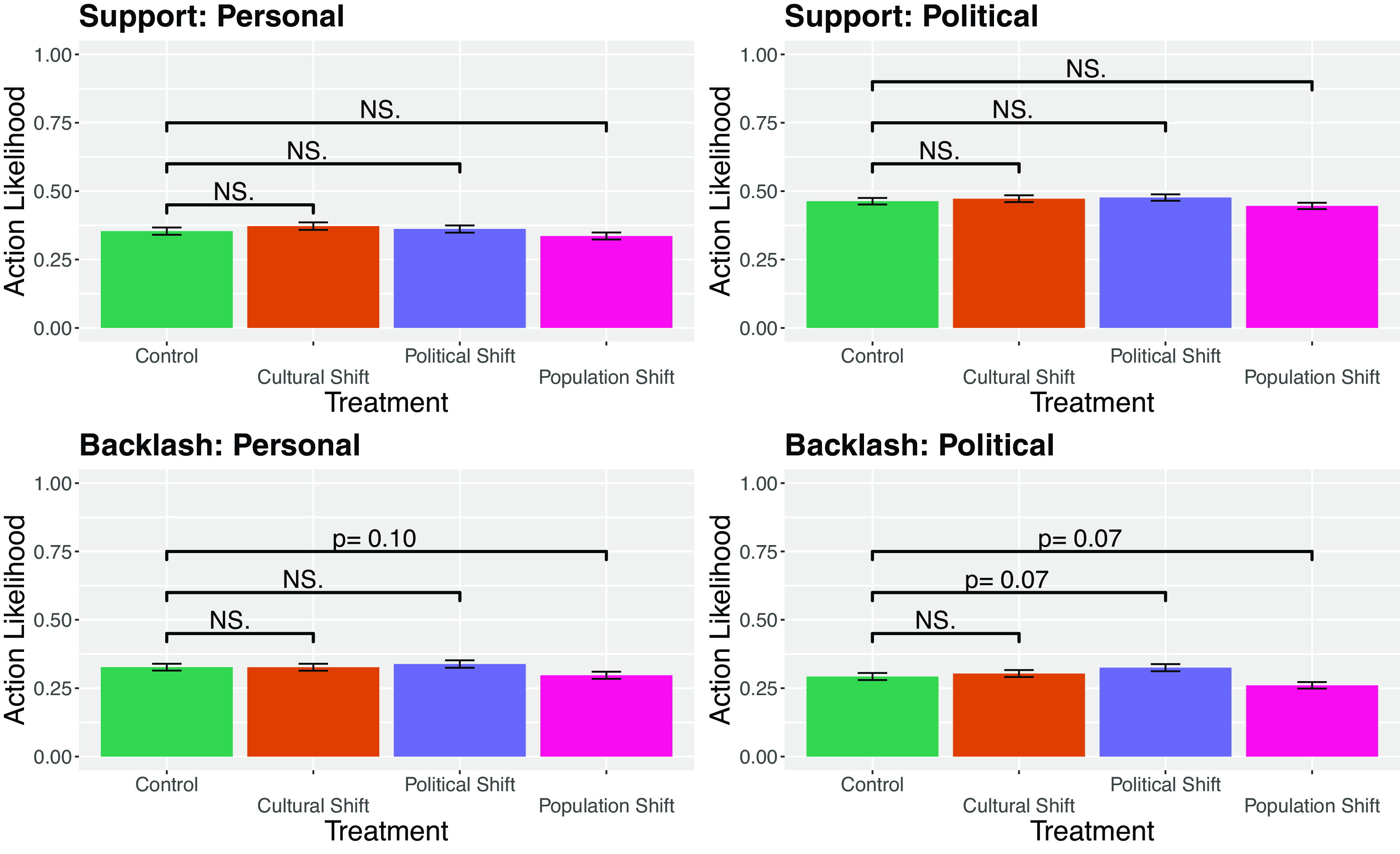

We conclude with our new outcome set: behavioral intentions regarding race either in politics or in one’s personal life. Figure 7 displays the results. Considering first our outcomes that, in some capacity, support people of color or oppose White racism, we find no treatments significantly affected political actions (smallest p = .161, d ≤ 0.09) or personal actions (smallest p = .259, d ≤ 0.07). Turning to the backlash variants, the political shift treatment increased the likelihood of taking political actions (p = 0.003, d = 0.19), a small but substantively meaningful result.

Figure 7. Treatment effect on (a) personal actions to support racial minorities, (b) political actions to support racial minorities, (c) personal actions in backlash to racial minorities, (d) political actions in backlash to racial minorities.

Turning to H4, we find no moderated treatment effects by partisanship (smallest p = .052, political backlash) and just one for ideology. We find a significant difference in intentions to engage in personal backlash actions between liberals and conservatives assigned to the political shift condition (p = 0.013). But this single result, and lack of comparable pattern on partisanship, leads us to see this as limited support for H4.

Conclusion

We sought to test whether the hierarchy-challenging context in which Whites learn about their declining majority status matters for conclusions reached about responses to demographic change. Despite a well-powered design, we found limited support for hypotheses related to existing evidence. While we replicate evidence that Whites perceive a status change in response to these treatments (H1a), there is no evidence of substantive changes in symbolic threat, realistic threat, or prototypicality threat in any condition (H1b). Likewise, Whites exhibit no general conservative policy turn (H2) or increased racial prejudice (H3) in response to any of the treatments. Nor do we find ideology or partisanship consistently moderate responses (H4).

Our results raise important questions about status threat and its connection to White opinion and action in politics.Footnote 6 While we motivated our investigation by asking whether hierarchy-challenging context mattered for Whites’ responses to demographic change, treatment effects were quite similar across conditions. This pattern suggests perceptions of social change and concern with one’s status are global reactions to even particularistic information.

To our knowledge, reported research consistently finds that population shift treatment increases status threat among Whites and promotes conservative attitudes. We are aware of only one other study reporting null effects (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2022), though this is possibly due to file drawer issues or us overlooking relevant work in a canvas of literature. While some of our results may then be false negatives, our study was powered to find treatment effects smaller than those typically reported in the existing literature. It is possible our sample mattered, with many studies using platforms like mTurk or Prolific to recruit convenience samples. But if so, null effects in our more diverse, quota-sampled study suggest weaker external validity, a result we think unlikely given some consistency between observational and experimental status threat studies (e.g., Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Abascal Reference Abascal2023; cf. Fouka and Tabellini Reference Fouka and Tabellini2022).

An alternative explanation concerns potential pretreatment (Druckman and Leeper Reference Druckman and Leeper2012). While events occurring during our field period could have mattered, including the presidential campaign, our subjective manipulation checks found that the treatments worked as intended. We instead speculate that some of demographic change’s attitudinal consequences, seen in status threat beliefs and policy opinions, may be increasingly crystallized, and to like degree for Whites across the political spectrum given the salience of issues related to race and diversity in the last few years (e.g., Sides, Tausanovitch, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tausanovitch and Vavreck2022). This is not to say that related attitudes are not changing in this period (Sides, Tesler, and Griffin Reference Sides, Tesler and Griffin2024). Instead, the present results suggest this is not necessarily connected to facts about, and perceptions of, Whites’ changing population share.

Our manipulations altered perceptions of demographic trends in the US population, electorate, and media landscape, as well as status change beliefs. But the lack of movement on theoretically relevant constructs, including various status threat measures, racial and non-racial policy preferences, racial attitudes, and willingness to take personal and political actions supporting or opposing racial minorities, ultimately suggests that recognizing these facts does not necessarily have downstream consequences. One interpretation is that people may not remember why they, for instance, feel more status threat or willingly take more anti-racist actions, with these orientations previously updated from information akin to the treatments, evidence of online processing (Hastie and Park Reference Hastie and Park1986). That group-based orientations are prototypical symbolic attitudes makes this possible (Sears Reference Sears, Iyengar and McGuire1993). If true, this, in our view, pushes status threat broadly away from state-like features to trait-like orientation. In other words, beliefs about status change are unrelated to feelings of status threat or the myriad status-preserving attitudes we measured. If so, then this qualifies arguments that status threat beliefs necessarily originate in viewing one’s group as losing status. It may not be necessary to perceive Whites as losing influence in society to think that in 50 years what it will mean to be an American will be less clear or that members of other racial groups are displacing members of my racial group from jobs.

That we find sizeable effects of our political affiliation measures on the various outcomes supports prior exposure of some type. For instance, the constituent terms in Appendix Tables C8–13 indicate that not only do conservatives compared to liberals hold more conservative policy preferences, view racial minorities and BLM more negatively but Whites and the Alt-Right more positively, and are more likely to engage in backlash and less likely to engage in supportive behaviors, they also express much greater status threat.

We close by noting that we do not think Whites are unaffected by shifting demographics. Instead, we think our study points to rich areas for future research. First, replication matters, including evidence of null effects. Second, we call for clearer theorizing on status threat, in our read the core mechanism linking demographic change to politically relevant attitudinal responses (Parker and Lavine Reference Parker and Lavine2024). In order to enrich our understanding of the political consequences of status threat, it is essential to clarify whether, or when, it functions as a state, as the present paradigm presumes, or a trait, as our evidence suggests. Lastly, it might be that today, generalized awareness of shifting demographics may not relate to status threat, although challenges to majorities’ status within personally important institutions or organizations, such as one’s political party (e.g., Pérez et al. Reference Pérez, Kuo, Russel, Scott-Curtis, Muñoz and Tobias2022), may remain capable of stoking status threat. Pursuing these questions would help scholars understand when, why, and among whom this lever matters for understanding the politics of native majorities.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2025.2

Data availability

Support for this research was provided by Stony Brook University’s Faculty in the Arts, Humanities and lettered Social Sciences (FAHSS) Award. The funders had no role in the analysis nor restricted what findings could be published. The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: doi: 10.7910/DVN/1F8YVV.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, connections to other organizations, or other financial interests related to this research. This research was supported by a grant from the Stony Brook University Fine Arts, Humanities, and Social Science Initiative. It is not under review at any other party, nor will it be subject to additional review by other parties prior to publication.

Ethics statement

The study presented in this paper was approved by the Stony Brook Institutional Review Board (IRB2024-00265). This research adheres to APSA’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. Please see Appendix H for further information on how the survey was conducted.