It promised to be an exciting day for Carlos Burmeister. The Argentine naturalist had persuaded Jordan Hummel, the captain of the steamship Cometa, to have the boat wait for him an entire morning while he made the trek to the massive falls of the Iguazu River, on the border between Argentina and Brazil. At thirty-two, Burmeister was an experienced traveler. He had accompanied his late father, the German-Argentine naturalist Hermann Burmeister, in many of his field explorations and had recently traveled to Patagonia on his own to collect birds. Now Carlos was spending the months of June and July 1899 surveying the status of yerba mate production in the northeastern Argentine territory of Misiones on behalf of the country’s Ministry of Agriculture. Heretofore, his daily routine had consisted mostly of perfunctory observations of yerba mate operations, but now he would finally have a chance to see something different – the quasi-mythical falls.

At the time, Iguazu Falls attracted very few visitors. To reach them, it was necessary to disembark at a yerba mate port on the Brazilian banks of the Iguazu River and walk or ride mules through swamps and forests for several hours. The only existing land route to the falls cut across Brazilian territory. After spending the first hours of the morning traversing the forest, Burmeister and his guide arrived at the trailhead leading to the falls. At the entrance of the footpath, he was surprised to discover a sign nailed to a large tree: “National Park, March 1897, Edimundo Barros [sic].” Asking his local guide, a Frenchman named Puyade, what the sign meant, Burmeister was informed that it had been posted by Barros, a young Brazilian army captain stationed at the border military outpost twenty kilometers away. Burmeister concluded that Barros intended “to reserve the zone surrounding the falls for [the creation of] a national park, like those of the United States of North America [sic].”Footnote 1 To Burmeister, this might have been an alarming development, as it was a sign of Brazil taking steps to claim its side of a natural monument shared by the two countries.

Argentina, not Brazil, was the pioneer in establishing a national park to protect Iguazu Falls, and this chapter focuses on the creation of Iguazú National Park in 1934. Some of the themes informing the creation of the Argentine park were already present in Burmeister’s reaction to the Brazilian “national park” invented by Barros in 1897. The rivalry between the two countries, for example, informed Argentine policymakers’ desire to take material and symbolic possession of their side of the falls. Furthermore, park proponents drew inspiration from the protection of natural landscapes in North America (and to a lesser extent in Europe) and saw national parks as perfect instruments to “Argentinize” the falls and, by extension, the nation’s border with Brazil.

The establishment of Iguazú National Park was part of a 1930s boom of protected areas in Latin America that included five other national parks gazetted by Argentina and three by Brazil.Footnote 2 This upsurge in national park creation is best understood as part of the general expansion of the state in Latin America after 1929. The Great Depression had dealt a severe blow to most Latin American economies, and the response of country after country was to shift away from the largely laissez-faire policies of the previous decades. The reaction to the crisis included the adoption of new forms of economic nationalism and a renewed focus on expanding the institutional capacity of the state.Footnote 3 In the case of Argentina, public expenditure increased from 16 percent of GDP in 1925–29 to 21 percent in 1935–39 as the government of General Agustín Justo (1932–38) responded to the crisis by expanding the role of the state and entrusting several areas of governance to technocrats. It was during Justo’s tenure that Argentina established its national park agency and started to develop the country’s first national parks.Footnote 4

Argentine policymakers were inspired by international examples of national parks, mainly from Europe and North America. The process of implementing those ideas was far from a reflexive adoption, however, as it involved negotiation between different government stakeholders and adaptation to perceived local needs. As the recent literature on protected areas has demonstrated, the national park model was transformed and adapted from its canonical form in most places, especially before the rise of global environmentalism in the 1970s.Footnote 5 Argentina was no different: The country devised national parks as geopolitical tools to “Argentinize” the country’s northeastern and Patagonian borderlands through the promotion of tourism and settlement.

The lack of consensus on the tenets of national park policy was recognized by Exequiel Bustillo, the father of national parks in Argentina, as one of the main challenges to conservation. Writing in 1968, Bustillo explained that the absence of a unifying national park doctrine allowed adaptation to local “geographic, economic, and political needs” to occur.Footnote 6 In the 1930s, Bustillo and his colleagues understood national parks as drivers of economic development in peripheral areas. They were also cognizant of the geopolitical concerns of Argentine political elites, and they managed to reframe national park policy as an instrument for extending de facto sovereignty to sensitive border regions. Thus, park proponents in Argentina managed to create a national park model that combined their plans of fomenting a tourism industry with government and military officials’ goal of promoting colonization at the border. This chapter explores the processes through which Argentine frontier boosters, loosely inspired by foreign examples of national parks, worked to create the Argentine national park agency and Iguazú National Park in 1934. It shows how they conceived parks in 1930s Argentina as vehicles for the settlement and development of frontier regions vis-à-vis competing neighboring countries.Footnote 7

An Argentine Response to the Brazilian “National Park”

Because of Iguazu Falls’ scale, remote location, and uniqueness, many saw them as a natural candidate for monumentalization, and thus as a prominent location for a future national park. The “national park” created on the Brazilian side of the falls by Captain Edmundo de Barros was never more than a fabrication by an independent-minded army official deployed on the country’s isolated frontier. Nevertheless, the effort he put into publicizing the idea to visitors encouraged policymakers on the other side of the border in Argentina to create their own national park. One such visitor was Argentine politician Juan José Lanusse, the governor of the Territory of Misiones between 1896 and 1905. In 1898, Lanusse visited the falls with his family and friends as guests of the steamboat and logging company Nuñez y Gibaja. Like Burmeister a year later, Lanusse reached the falls after landing on the Brazilian banks of the Iguazu and trekking through the forest. In this way, Lanusse ended up seeing the falls from inside the “national park” established by Barros in Brazil.

Lanusse was amazed by the panoramic view of the magnificent falls and began devising a plan to bring tourists from Buenos Aires, located 1,700 kilometers downriver. He first persuaded Porteño businessman Nicolás Mihanovich, whose company operated more than 200 steamers in Argentina, to initiate a regular service to the falls via the Paraná River. The Mihanovich company started offering a twenty-day cruise (round trip) in a luxurious steamboat from Buenos Aires to the falls that culminated with a visit to the “wonder of the Americas” that “put Niagara to shame.”Footnote 8 In 1901, the first Mihanovich ship arrived at the mouth of the Iguazu River, bringing a party of thirty tourists from Buenos Aires that included the crème de la crème of the Argentine elite. With 3,000 pesos donated by Victoria Aguirre, a Buenos Aires socialite who took part in the first 1901 excursion, Lanusse began building a road to the falls within Argentine territory, which would eliminate the embarrassing need for disembarking on the Brazilian side. Lanusse also started pressuring the Argentine government to create a real national park on the Argentine side of the falls. To this end, in 1902 he wrote a decree designating the lands around the falls for the creation of a park.Footnote 9

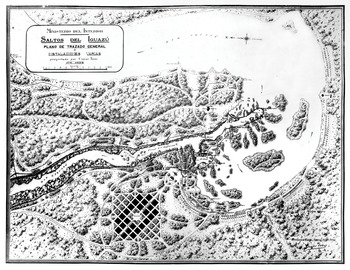

As governor of a federal territory, Lanusse did not have the power to create a national park, but he persuaded the Argentine minister of the interior, Joaquín Víctor González, to support the initiative. The minister, in turn, commissioned the French-born landscape designer Charles Thays, one of Argentina’s most renowned architects at the time, to design a plan for a national park in Iguazu. Since 1891, Thays had been the director of the Buenos Aires Office for Parks and Walkways, and as such was responsible for designing many of the city’s Paris-inspired boulevards and plazas as well as the city’s zoo and botanical garden.Footnote 10 In April 1902, Thays and his team of experts disembarked in Iguazu for a two-month stay, during which they surveyed the Argentine side of the falls and designed a plan for the future national park (see Figure 1.1). The architect was impressed not only by the falls but also by Avenida Aguirre, as he called the still unfinished road connecting the modest port at the mouth of the Iguazu to the cataracts upriver. In the plan he presented to the Ministry of the Interior, Thays expanded the twenty-meter-wide dirt road cutting through the dense forest into a manicured grid of walkways, roads, and gardens. The same principles of ordered and Cartesian nature found in the French-inspired urban parks and plazas he had designed in Buenos Aires guided his plan for a park in Iguazu.Footnote 11

Figure 1.1 Plan for a national park on the Argentine bank of Iguazu Falls by Charles Thays, 1902.

The push for national parks was gaining momentum in Argentina. A year after Lanusse lobbied President Julio A. Roca for the establishment of a national park in the northern tip of the country, in the south the famous explorer Francisco P. Moreno returned 8,000 hectares of public land he had been granted around Lake Nahuel Huapi in Patagonia for the creation of a “natural park.”Footnote 12 The Argentine government officially accepted the donation in 1904 in a presidential decree reserving the returned land for a future “national park.” A decree issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock in January 1908 delimited the tract of land for the creation of the national park, and Congress passed the Territory Development Act in August of the same year, giving the national government greater powers to make use of public land and build railroads in Patagonia.Footnote 13 In 1909, a group of northern congressmen led by the representative Marcial Candioti and the senator Valentino Virasoro protested the exclusion of the Territory of Misiones from the 1908 Territory Development Act and drafted a bill for the development of the northern territory.Footnote 14 The new law, passed in September 1909, provided for the creation of a railroad connecting the falls to the rest of the country. More importantly, it also provided for the purchase – or, if necessary, the expropriation – of a 75,000-hectare tract of land at the border with Brazil. Making the land public would allow for the creation of a national park to facilitate tourism to the falls, the establishment of a military colony such as the one Brazil had established on its side twenty years before, and the construction of a hydroelectric power plant for the industrial exploitation of the falls. Provincial politicians already understood national parks as development tools on equal footing with transportation and energy infrastructure.Footnote 15

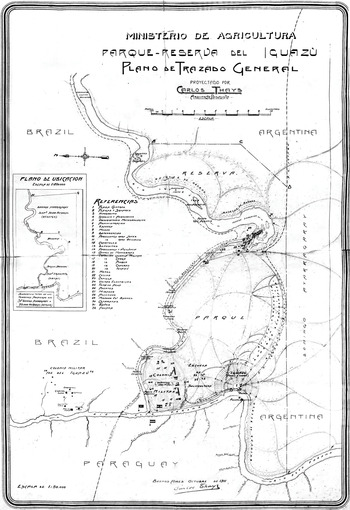

The new 1909 law cited the military colony and national park on the border with Brazil as the backbone of the future development of Misiones. The plan Thays presented in 1902, which provided for a park along the lines of the urban parks he had designed in Buenos Aires, had to be redone to take into account the new demands of border colonization. In 1911, the Ministry of Agriculture commissioned Thays to update his project, and the architect presented his new plan along with a detailed explanation to Minister Adolfo Mujica in 1912 (see Figure 1.2). What Thays initially had envisioned as a French city park adjacent to the falls grew to the scale of a US national park, with an area of about 25,000 hectares. In his new project, Thays argued that the falls at Iguazu, unlike Niagara, were still surrounded by a beautiful, lush subtropical forest, and state intervention would be needed to avert a repetition of the rampant industrial and commercial development that had spoiled their North American counterpart.Footnote 16 This proposal was quite different from his 1902 vision of a manicured landscape, reflecting the influence of US ideas about national parks and the role of forests in the composition of natural scenery.

Figure 1.2 Plan for a national park on the Argentine bank of the Iguazu Falls by Charles Thays, 1911.

Thays was never an enemy of development, however, and his plan for the expanded reserve also provided for a panoply of border infrastructure including a railroad connecting Posadas, the capital of Misiones, to the park; an urban settlement; a military colony; highways; a forestry school; a government-run farm; hydroelectric power plants; hotels; and a casino. A closer look at Thays’s 1909 national park blueprint makes clear his desire to translate Ebenezer Howard’s increasingly popular idea of the garden city to a frontier setting. In the concentric rings of the projected town of “Iguazú,” the new plan would combine conservation of nature with urban development and modernization.Footnote 17 For the architect, all this development not only could be harmonized with the natural beauty of the falls and the surrounding forest but also, in fact, would improve it. As he saw it, the difference between his plan for Iguazu and the uncontrolled development at Niagara Falls was the mind of the planner, who was positioned to improve nature to better suit human needs without spoiling it.Footnote 18

The tension between development and conservation did not go unnoticed by Thays’s contemporaries. His harshest objector was Paul Groussac, a traveler, writer, and literary critic who, like Thays himself, was also a Frenchman living in Buenos Aires. After visiting the falls, Groussac contended that implementing Thays’s plan would lead to a reproduction of the systematic degradation of the natural scenery created by tourism in places like Niagara Falls and the Swiss Alps. For Groussac, the project bore the “incongruity between the term ‘virgin forest’ and the barbarisms of [the proposed] boulevards, plazas, casinos, etc.”Footnote 19 He believed some federal investment was necessary to keep the natural monuments public, but not at the gargantuan scale imagined by Thays – a simple but decent hotel and the renovation of the existing roads and port would suffice. Groussac criticized the excesses he had identified in Thays’s 1911 project, pointing out that much of the planned infrastructure would be of more use elsewhere in the Territory of Misiones, in towns such as Posadas or Candelaria whose populations did not have yet access to necessary improvements such as a telegraph line. Where Groussac agreed with Thays was on the need for federal intervention with regard to the border landscape. Both men accepted the call for state action to preserve the falls and the legitimacy of the state claims to expropriate the lands adjacent to the natural monument.Footnote 20

Turning Private Land into Public Land

In the vast majority of cases, the national government owns a country’s national parks. When the state designates private lands as parkland, it demands their conversion into public land. In Argentina, the lands around Iguazu Falls were in private hands. Domingo Ayarragaray, a Uruguayan-born entrepreneur from Buenos Aires, had acquired the 75,000-hectare estate surrounding the falls in Argentina at auction in 1907. Although Law 6712 had provided for the federal purchase or expropriation of the estate in 1909, the Argentine government did nothing in the following decade. Ayarragaray, for his part, kept his new property idle and waited for the federal government to initiate the proceedings to acquire the estate. When the government in Buenos Aires made no move to purchase or expropriate the area, Ayarragaray decided to put his property to use.Footnote 21

He first moved to profit from the increasing number of people arriving by river to see the cataracts, and in 1920 he hired Buenos Aires engineer Olaf Hansen to build a hotel in front of the falls. The new twenty-four-bedroom Iguazú Hotel was completed in 1922, as a substitute for the rustic wooden lodge that stood there previously. The engineer also built a new road connecting the falls to Puerto Aguirre, the port near the mouth of the Iguazu River where tourists disembarked, shortening by three kilometers the old route built by the territorial government. Hansen became partners with Ayarragaray in Iguazu, managing the hotel and starting an obraje on the estate in 1921.Footnote 22

Obrajes (or obrages in Portuguese) were the most common type of enterprise in this border area before the 1930s. These companies employed temporary workers of indigenous or mixed descent, usually speakers of Guarani, in logging and yerba mate production. In many firms, the relationship between workers and bosses evolved into a situation of debt bondage analogous to the case of the rubber tappers in Amazonia.Footnote 23 In the upper Paraná River, it was common for entrepreneurs to receive land concessions from the governments of Argentina and Brazil of forested areas abundant in hardwood and wild yerba mate, which would be cut, processed, and sent downriver to consumer markets in and around Buenos Aires. At its height, the logging obraje on the Ayarragaray estate employed 1,000 seasonal workers and produced more than 6,000 eighteen-meter beams per month. The beams were transported on large timber rafts downriver to Posadas. For this logging operation, Hansen had his workers blaze a series of trails penetrating deep into the woods, and a new port, called Puerto Iguazú, was established on the bank of the Paraná River, from which the rafts floated to Posadas. It was the first time since the late nineteenth century that the forests on the Argentine bank of the Iguazu were subjected to the pressure of human economic activity. Before the twentieth century, the area had been exploited as a source of wild yerba mate, but the activity had since moved northward to the richer forests of Brazil.Footnote 24

Ayarragaray and Hansen’s investment in the hotel improved the infrastructure to cater to the increasing stream of visitors coming from Buenos Aires through the Paraná River (see Table 1.1). The majority were members of the Porteño elite, but there were also many Europeans and North Americans who wanted to see the mythical cataracts that rivaled Niagara. The development of this nascent tourism industry rekindled in the Argentine government the desire to purchase the area. In 1926, the Ministry of Agriculture commissioned agriculture engineer Franco A. Devoto, along with forest technician Máximo Rothkugel, to survey the Ayarragaray estate and assess its market value in preparation for its nationalization or purchase by the state. Their report exposed the tension between conservation and colonization that dominated Argentine environmental policy up to the 1960s.

Table 1.1 Guests at the Iguazú Hotel

| Year | Guests | Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1924 | 525 | – |

| 1925 | 735 | +40% |

| 1928 | 950 | +30% |

On the one hand, Devoto and Rothkugel criticized Thays’s plans for a park modeled after the plazas of Buenos Aires, arguing that tourists arriving in the new national park were looking to experience a forest in its “natural state,” not the “combed and perfumed” nature of urban parks. All interventions should, therefore, be subtle, avoiding the introduction of nonnative species (the few existent should be extirpated), reforesting human-made clearings, and using rustic materials such as wood and stone in the buildings – thus mimicking the style of the hotel built by Olaf Hansen. On the other hand, the report emphasized, in geopolitical and racial terms, the need to create a military colony similar to the one existing in Brazil before 1910 that had eventually given rise to the town of Foz do Iguaçu. For the two engineers, establishing a military colony would create a vital hub for the “Argentinization” of the borderland.

Misiones already had colonies in other parts of the territory, but in some cases these harbored Brazilians who had moved in from across the border, and the lack of Argentines impeded the communities’ cultural assimilation. Although they valued the “racial purity” of these settlers – the majority descended from Germans who had first immigrated to southern Brazil before moving on to Argentina – Devoto and Rothkugel despised their Brazilian “Creole culture” and their material poverty, which the two attributed to the loss of the work ethic that had characterized their German forefathers. Their close-knit communities were also a problem, keeping them isolated from the rest of Argentina. Using the Guarani and mixed-race population already present in this border region for a state-sponsored colony was out of the question for these two Porteño engineers. Colonization, like tourism, should focus on whites only. They believed a new colony should receive people from different European backgrounds to dilute group identity and facilitate assimilation. The colony’s goal was to transform a heterogeneous influx of white immigrants into a homogenous group of Argentine citizens.Footnote 25

The Argentine government finally purchased the 75,000-hectare estate, along with the hotel and other properties, through an agreement between the Ministries of Agriculture, Interior, War, and Finance on March 12, 1928, for which it paid the sum of 3,199,017.60 pesos to Ayarragaray’s inheritors. Twenty years after the passage of Law 6712 in 1909, the Argentine side of the falls had finally become public land. The 1909 law had provided for the creation of a military colony and a national park, which replicated what Argentines perceived to have happened across the border, with a (real) military colony created by Brazil in 1889 in Foz do Iguaçu and a (made-up) national park on the Brazilian side of the falls. It also regulated the harnessing of the falls’ hydroelectric power, a stricture that had been rejected since then. The Ministry of Public Works started studying the hydroelectric potential of the falls in 1917. In 1928, a final report concluded that the building of a hydroelectric dam at Iguazu Falls was economically infeasible owing to the location’s distance from the major centers of consumption in and around Buenos Aires. The project was dropped, which allowed the Argentine government to focus on border development through settlement and national park policies.Footnote 26

The land was now public, but the creation of the Parque Nacional del Norte, as the project was called in the 1920s, would also require congressional approval and the establishment of a government agency charged with implementing it. The absence of the latter explained the initial failure in creating another national park, the Parque Nacional del Sud in Nahuel Huapi, and served as a cautionary tale for national park proponents in Argentina. This park was gazetted by a 1922 presidential decree, on the Patagonian lands donated by Francisco P. Moreno in 1903, but owing to the lack of institutional support, it existed only on paper until being re-gazetted in 1934.Footnote 27

In the meantime, the Argentine Army would control the estate until a final decision was made. The military maintained a small garrison with sixteen soldiers and, through a concessionaire, exploited the groves of wild yerba mate on the property. The hotel by the falls, which now was state-owned, was also operating through a concessionaire, the Dodero Company. The army authorized the people living on the estate to temporarily plant fruit trees in existing clearings and to cut firewood for personal consumption, but commercial logging as it had been practiced during the Ayarragaray years was strictly prohibited. The military in charge intended to keep the estate free of any significant development until the definitive boundaries between the area of the military colony and the national park were set. The territory of the park was one step closer to becoming an area without extractive activities.Footnote 28

The New Model of National Park Management

Argentina created Iguazú National Park in 1934, six years after the nationalization of the Ayarragaray estate. The law, which set apart a significant portion of the estate as a preserve, also created a national park agency and another park around Nahuel Huapi Lake in Patagonia, picking up where the early proponents of that southern national park had left off in the 1920s.Footnote 29 The 1934 national park act passed in the Argentine Congress with the help of two new lobbies; one from Misiones in the north and the other, more powerful and consequential, made up of a diverse group of Buenos Aires businessmen and politicians connected to the conservative politicians in power in the early 1930s. The Buenos Aires group was crucial to the crafting and passage of the national park act as well as to the establishment of the two parks the legislation gazetted, Iguazú and Nahuel Huapi.Footnote 30

The group of national parks boosters from Buenos Aires included people from different backgrounds, ranging from natural scientists such as Ángel Gallardo to military officers such as General Alonso Baldrich. What they had in common was a connection to the Argentine government – many were employed in the highest echelons of the civil service – and an interest in Andean Patagonia. In 1931, they launched a campaign to reinstate a national park commission that had briefly existed in the 1920s. Initially led by Luis Ortiz Basualdo, the new commission was joined in 1933 by Exequiel Bustillo, who became a key figure in the establishment of a national park system in Argentina. Basualdo and Bustillo were both scions of patrician families from the Argentine capital with real estate interests in Patagonia. They intended to rekindle interest in the creation of a national park in Nahuel Huapi to promote infrastructure works in nearby Bariloche and develop the tourism industry in the Argentine Andes. They had limited knowledge of national parks and conservation – Basualdo introduced the topic to Bustillo as a strategy for reigniting stalled government investment in the region in an unlikely combination of conservation policy and real estate development. But as members of the Porteño elite, with family, friendship, and business ties to the conservative politicians in power during Agustín Justo’s regime, the group now led by Exequiel Bustillo succeeded in convincing federal officials of the need for national parks in Patagonia.Footnote 31

The Argentine government reinstated the Comisión Pró-Parque Nacional del Sud (Pro-Southern National Park Commission) in 1931, and in 1933 expanded it as a broader Comisión de Parques Nacionales (National Parks Commission), now with Bustillo at its head. More importantly, the commission, which initially focused only on Nahuel Huapi in Patagonia, now incorporated the creation of Iguazú National Park among its responsibilities. Led by Bustillo, the renamed commission gained momentum as it fervently started drafting a national park bill that would provide the legal basis for the creation of both Iguazú and Nahuel Huapi national parks as well as a national park agency.Footnote 32 Bustillo’s concerns rested mainly on Nahuel Huapi and Patagonia in the south, and he was only nominally invested in Iguazú and the northern part of the country. However, he intended to ensure the commission would have a lasting legacy in the form of functioning national parks and saw the inclusion of Iguazú, a national park in an advanced stage of implementation on the opposite end of Argentina, as a way to institutionalize parks as a national policy. His goal was to avoid the fate of past isolated initiatives that had focused solely on the creation of Nahuel Huapi and had overlooked the establishment of an institutional structure in the form of a national park agency and specific legislation to support it. Including Iguazú in the responsibilities of the new commission was also a response to the general demand among politicians and the military that national parks be used as a tool for the development and nationalization of border zones. This idea was already present in the plans elaborated by Thays in the 1900s and 1910s for Iguazú and was quickly adopted by the group of park proponents led by Bustillo for the entire Argentine park system.Footnote 33 Geopolitical concerns were made clear in the 1933 presidential decree expanding the commission, whose seventh article stated that national parks located on international boundaries had the mission to “develop a policy of nationalization of borders.”Footnote 34

Bustillo spent months in 1933 drafting the national park bill with the help of other members of the commission – in particular, Antonio M. Lynch and Gustavo Eppens. Bustillo recognized that, initially, he had little knowledge of conservation and national parks, but he had an idea of how national park laws would serve to “occupy and nationalize a border where our sovereignty is only nominal.”Footnote 35 The new legislation included as its backbone the creation of a powerful and semiautonomous national park agency charged with managing national parks and proposing new protected areas. The national park agency would be subordinated to the Ministry of Agriculture, but unlike other departments inside the ministry, it would enjoy greater financial and administrative autonomy to control land in designated areas.

The autonomy of the agency was a crucial point for the framers of the new law, and they closed ranks against attempts by other ministries (e.g., Finance, Interior) to subordinate the new agency to their own offices. Officials inside the Ministry of Agriculture, for example, raised questions about the autonomy of the new national park agency as defined by the new legislation. In his review of the draft of the bill, the head of the Dirección de Tierras (Directorate of Lands) complained that the new text granted excessive powers to the new national park agency, whose sovereignty over protected areas would be comparable to that of the national territories harboring the parks. Despite these criticisms, the commission finished the draft and the executive submitted the bill to the Argentine Congress in September 1934.Footnote 36

National park commission members’ ties to the conservative politicians ruling Argentina in the 1930s greased the process of passing the bill. The Senate commission designated to examine and approve the bill was not invested in advancing the matter, so Bustillo used his family and personal connections to set things in motion and collect a majority of signatures to put the bill to vote. One of the senators in the commission, Antonio Santamarina, was Bustillo’s wife’s uncle. His brother, José María, was a deputy in the lower chamber. Both politicians were members of the National Democratic Party, the conservative party that led the governing coalition and retained the largest number of senators and deputies in the Argentine Congress in 1934. Bustillo also used his contacts in the press to lobby for the passing of the national park act, asking editor friends at La Prensa and La Nación to write editorials in support of the bill.Footnote 37

The bill was put up for a vote at the end of September 1934. Socialist Senator Alfredo Lorenzo Palacios presented the only serious objection: to a clause requiring that all employees in border national parks be Argentine by birth. Palacios objected that not even senators like himself were required to be born Argentine to assume office. Cruz Vera, the conservative senator from Mendoza who had introduced the bill, explained that the planned national parks were located in border areas “flooded with foreigners,” and the article was meant to “Argentinize” the border. Despite his frankness in explaining the geopolitical reasoning behind national park creation, the clause was removed and the bill was finally passed into law.Footnote 38 Law 12103, also known as the National Park Act, established the legal framework for an Argentine national park system. The 1934 act created not only the two first national parks in the country – Iguazú National Park in the north and Nahuel Huapi National Park in the south – but also established a national park agency, the Dirección de Parques Nacionales (Directorate of National Parks, DPN).Footnote 39

The new agency enjoyed a great degree of autonomy, with a budget free from the constraints of the Ministry of Agriculture – to which it was formally subordinated – and with the power to create and enforce protected areas. It also had exclusive jurisdiction over the territories of the national parks, especially vis-à-vis other government agencies, a feature partially inspired by the US national park model. A strong, well-funded, and relatively autonomous national park agency like the one created in 1934 in Argentina was an oddity in South America. In neighboring countries like Brazil, national parks, when they were actually implemented, were usually put under the supervision of forestry departments or botanical gardens, which lacked funds and specialized personnel.

In the case of Argentina, the new national park agency had the mandate to oversee all park-related issues, preserving the fauna, flora, and geological features of national parks; promoting tourism in the parks; and building infrastructure. On paper, this seems similar to the mission of contemporary national park agencies in North America and Europe.Footnote 40 The agency distanced itself from its foreign counterparts, however, in its commitment to nationalizing the border regions and developing settlements.Footnote 41 For this purpose, the national park act provided the DPN with the power to allocate public land within parks and reservations to unique uses. The Argentine agency could grant temporary permits for tenants or sell public land in areas reserved for real estate development inside national parks. National park administrators could set the location of new population centers, plan street grids, build urban infrastructure, and sell urban and rural lots of public land within a 5,000-hectare limit inside their territories. From its inception, national park policy in Argentina was designed to merge the potentially contradictory goals of conservation, public use, and urban development.Footnote 42

Dealing with the Military

Argentine park proponents had managed to build a robust legal framework to support the establishment of the country’s first national parks. At the heart of the new legislation lay the DPN, a powerful national park agency with the capacity, at least on paper, to act within Argentine territory. But as the DPN’s mandate expanded onto other agencies’ turfs, those agencies resisted transferring their functions to national park officials. For Bustillo and the other members of the national park commission, passing a national park law proved to be easier than convincing other sectors of the government to comply with the new legislation and recognize the DPN’s powers and legitimacy. In the case of Iguazú, for example, this type of opposition came from the military.

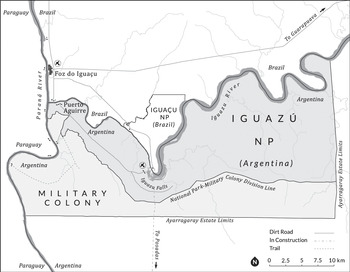

The Argentine Army, which had assumed control of the Ayarragaray estate after its acquisition in 1928 and was required to hand over the area to the DPN in 1934, resisted for seven years before finally transferring the land to the national park agency in 1941. Anticipating this sort of resistance, in July 1935 Bustillo sent General Alonso Baldrich, then one of the directors of the DPN, to take official possession of the Campo Nacional del Iguazú (Iguazú National Camp), as the military called the estate after 1928. The army handed the hotel and other properties inside the estate over to the agency, but it did not give up the control of the land. In August a presidential decree established that of the estate’s 75,000 hectares, 20,000 would be kept by the Argentine Army and 55,000 would be transferred to the DPN as a national park. The boundary between the two areas was to be defined by an agreement between the national park agency and the army.Footnote 43

Setting this boundary proved difficult, as it required the armed forces to accept transferring their sovereignty over a sensitive border area to a new agency whose members had yet to prove their seriousness. The minister of war, General Manuel A. Rodríguez, purposefully delayed the demarcation as a way to postpone the transfer of the area to the DPN. Rodríguez believed the estate and its infrastructure were too important to be given to a “commission created by some politicians’ whim” that “could disappear or be substituted by another commission with different ideas.” In the following years, Rodríguez and his successors at the Ministry of War kept making vague promises to delimit the boundaries while doing little to advance the matter. In Argentina, in the 1930s, passing a new law did not result in immediate compliance, especially when it came to the perceived institutional interests of different entities that formed the state.Footnote 44

The position of the military started to change by the end of the decade, mainly due to its own failure in bringing settlers to populate the border. A 1939 memo from General Martin Gras, the army chief of staff, to the minister of war, Carlos Márquez, brings to light the army’s inability to establish a military colony “to settle an Argentine population in the region to cooperate with the armed forces deployed at the border.” Reproducing a common perception among Buenos Aires–centered public officials, Gras blamed Misiones’s subtropical forests for the army’s failure to attract settlers from the temperate pampas to populate the area.Footnote 45 Also, five years after its creation, the DPN had already demonstrated its seriousness not only with the extensive infrastructure it had developed in Nahuel Huapi National Park but also by improving the properties in Iguazú. Since 1935, the agency had renovated the hotel, built pathways and trails by the falls, installed piers at three different points along the Iguazu River, initiated the construction of a 1,000-meter-long grass landing strip near the falls, and finished the park headquarters in Puerto Aguirre. It had become clear that the DPN’s plan to develop the border through tourism and the urbanization of Puerto Aguirre could work where the military had failed.Footnote 46

At the beginning of 1939 the Ministry of War, through its Engineering Department, finally agreed to demarcate the boundary between the national park and the military camp. But the process still dragged on for two more years as the two parties disagreed over the location of the boundary line between reserve and military area. National park engineer Ivan Romaro proposed boundaries that required the removal of all military settlements from Puerto Aguirre to the new area controlled by the Argentine Army. The engineer insisted that the area occupied by troops in Puerto Aguirre was essential for the expansion and “hygienization” of the town, as he envisioned a zone of small farms occupying the confluence of the Iguazu and Paraná.Footnote 47 The army, unsurprisingly, insisted on keeping the zone for national security reasons, as it was located right at the corner where Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay met.

Bustillo intervened with the minister of agriculture to expedite a solution with the Ministry of War. After all, he argued, “the entire estate had been in the hands of the Army for five years, which had delayed the colonization and settlement of the area of Puerto Aguirre.”Footnote 48 After two more years of negotiation, the two sides finally reached an agreement based on the DPN’s proposed boundary. As a consolation prize, the army would receive lots in Puerto Aguirre along the Paraná River to establish vacation cottages for military officers deployed in the federal territory – an indication that the army’s refusal to transfer the control of the area was as much the product of institutional inertia as it was of national security considerations.Footnote 49 With the boundaries defined, the Argentine Army passed over control of the estate to the DPN through a presidential decree in September 1941. The decree set the boundary line between army and national park lands and designated 500 hectares of public land in Puerto Aguirre to be sold to private parties for colonization with the rest of the land, both in the park and in the army area, remaining public. The agency could now begin the urbanization and colonization of Puerto Aguirre (see Map 1.1).Footnote 50

Map 1.1 Iguazú National Park, Argentina, and Iguaçu National Park, Brazil, in 1941.

The Power of Local Players

With Nahuel Huapi as the flagship of the new national park system, Iguazú occupied a secondary place. When crafting the national park law, Bustillo and his colleagues included the northern park in the draft legislation mainly to justify the creation of a robust national park agency, which they saw as crucial for the viability of Nahuel Huapi and the development of Patagonia in the south. What, then, explains Bustillo’s later commitment to transferring Iguazú National Park’s territory to the DPN in light of his lack of interest in anything outside Patagonia? Here, the same family and class connections that facilitated the passage of the national park bill in 1934, allowing him to create the Nahuel Huapi National Park, ended up working in the opposite direction in the early 1940s, pushing him toward a greater commitment to Iguazú. The most significant source of pressure was Carlos Acuña, Governor of Misiones (1930–35), whose lobbying proved to be crucial in preventing Iguazú from becoming a paper park. Acuña was a close friend of José Maria Bustillo, the conservative federal deputy brother of Exequiel Bustillo who had worked in Congress for the passage of the 1934 national park bill, and thus had direct access to the head of the DPN.

Acuña was deeply invested in the creation of the national park in Iguazu and used his connection with the Bustillos to push the DPN to find a way out of the stalemate with the army. In the many letters Acuña exchanged with Exequiel Bustillo in 1935, he accused him – correctly, as it turned out – of favoring Nahuel Huapi National Park in Patagonia at the expense of Misiones and Iguazú National Park. For months Acuña pressed both Bustillo and the army to solve the imbroglio. Bustillo eventually grew tired of Acuña’s pressure, as it steered his focus away from his main interests in Nahuel Huapi. Yet he maintained a conciliatory façade, pointing the finger at the minister of war for “making use of the most absurd and contradictory arguments” to delay transferring the estate. After a face-to-face meeting with Minister of War Rodríguez in June 1935, Exequiel Bustillo succeeded in gaining control of the hotel and other properties in Iguazu, but he fell short of seizing the land. But the renovation of the hotel and roads, the construction of park headquarters, and the assignment of Julio Amarante, Acuña’s right-hand man, as Park Director in August 1935 were enough to placate the governor’s anxiety.Footnote 51

Julio Amarante was a high-profile federal official working for the government of the Territory of Misiones who had acted as interim governor between June and September 1935 before assuming the post of park director at Iguazú. Originally from Buenos Aires, Amarante had lived fifteen years in Misiones working for the federal government and had a vast knowledge of the federal territory. The first of many of Amarante’s demands as park director was the swift construction of the park headquarters (and director’s residence), which he required to be located not near the waterfalls, but in Puerto Aguirre. After all, it was the future location of “the most important urban settlement” of the region, to be created by the national park as part of its mission to occupy the border with Brazil. Upon moving in October from Posadas to Puerto Aguirre, Amarante was shocked by the destitution of the hamlet. Life in Puerto Aguirre proved to be almost unbearable thanks to the hot weather, mosquitoes, and lack of adequate accommodations for Amarante’s family, who continued to live in Posadas during his tenure as park director. He complained that the rugged wooden house in Puerto Aguirre, where he lived in his first months in the park, lacked “a proper bathroom and shower,” noting that guests “would have to make use of the nearby creek when answering the call of nature.”Footnote 52

Like Acuña, Amarante pressured Bustillo for more investment in the park and, especially, in Puerto Aguirre, which he classified as a “national disgrace.” He found in Miguel Ángel Cárcano, Minister of Agriculture (1936–38), an unexpected ally. While visiting the falls in 1936, Cárcano expressed his support for the development of park infrastructure, which gave Amarante leverage to write Bustillo demanding these investments be made. Yet the head of the DPN turned a deaf ear to most of Amarante’s requests, despite the support of Cárcano, who was nominally their boss. Echoing the opinion expressed by Paul Groussac almost three decades earlier, Bustillo emphasized that, unlike the lakes, mountains, and Swiss landscape of Patagonia in the south, Iguazu’s only selling point was the waterfalls. After one or two days of visiting, tourists grew bored, as the subtropical forest lacked the same opportunities for leisure one encountered in an alpine setting like Nahuel Huapi. To Bustillo, it was foolish to sink funds into a park with only one main attraction, Iguazu Falls.Footnote 53

Acuña and Amarante were right in complaining about the neglect of Iguazú vis-à-vis Nahuel Huapi, as Bustillo’s initial interest in national parks came out of his commitment to developing Patagonia. He shared with others the view of the southern border with Chile, with its snowy peaks, sparse population, and boundary disputes, as a more important target than Misiones for a policy of borderland nationalization through national parks. In 1936 the DPN, through the Ministry of Agriculture, drafted a new bill for the creation of five new national parks, all of them in Patagonia. The new areas were decreed reserves for “future national parks” in 1937 and started receiving investments before being officially gazetted as national parks in 1949, an indication of the consensus around Patagonia as a priority.Footnote 54 In the period between 1935 and 1942, Nahuel Huapi alone received 86 percent of all DPN investment in national parks – Iguazú received only 6 percent (see Table 1.2). The national park agency built a 350-bed grand hotel in Patagonian Park and another thirteen smaller hotels, a ski resort, a golf course, more than 600 kilometers of roads, several public buildings in the town of Bariloche (including a city hall, a police station, a courtroom, a library, a market, and a hospital), a zoo, and a game reserve stocked with imported Canadian moose and European deer.Footnote 55 Exequiel Bustillo’s obsession with Nahuel Huapi was so flagrant that in its 1942 annual report, the DPN tried to justify it with a table using the area and population living in and around the parks to show that the agency had actually invested relatively more in Iguazú than in Nahuel Huapi (see Table 1.3). At first glance, the DPN seems reasonable in justifying more investment in Nahuel Huapi than in Iguazú, as the former park was home to 9,800 people (a figure that included the town of Bariloche), in contrast to the mere 431 individuals living at the border where Iguazú was created. Yet, if the goal was to establish a permanent settler population at the border, then parks in areas without established towns, as it was the case of Iguazú, should have been the ones receiving greater federal investment.

Table 1.2 Investment in national parks, 1935–42 (in peso moneda nacional)

| Year | Nahuel Huapi | Iguazú | Lanín* | Los Alerces* | Copahue* | Glaciares/Perito Moreno* | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1935 | 309,828 | - | - | - | - | - | 309,828 |

| 1936 | 2,868,586 | 172,354 | - | - | - | - | 3,040,940 |

| 1937 | 2,443,580 | 246,241 | - | - | - | - | 2,689,821 |

| 1938 | 2,383,853 | 80,389 | 4,379 | 5,596 | - | - | 2,474,217 |

| 1939 | 1,006,751 | 206,123 | 101,267 | 194,713 | 41,045 | - | 1,549,899 |

| 1940 | 2,022,678 | 46,188 | 84,517 | 57,736 | 1,079 | - | 2,212,198 |

| 1941 | 2,150,842 | 156,222 | 58,219 | 37,662 | 14,203 | 4,987 | 2,422,135 |

| 1942 | 2,300,833 | 290,967 | 257,126 | 138,625 | 70,160 | 53,400 | 3,111,111 |

| Total | 15,486,951 | 1,198,484 | 505,508 | 434,332 | 126,487 | 58,387 | 17,810,149 |

* Established as national reserves for the creation of future national parks by the presidential decree 105433 of May 11, 1937. Law 13895 of September 20, 1949, transformed all the reserves into national parks, except for Copahue, which became a provincial park in 1963.

Table 1.3 Investment in national parks by population and area, 1935–42

| Year | Area | Pop. | Annual increase in number of tourists 1938–1942 | Investment (peso moneda nacional) | Investment per ha (peso moneda nacional) | Investment per capita (peso moneda nacional) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nahuel Huapi | 780,000 ha | 9,800 | 22.11% | 15,488,000.00 | 19.86 | 1,580.41 |

| Iguazú | 55,000 ha | 431 | 5.04% | 1,198,500.00 | 21.80 | 2,780.74 |

| Lanín* | 393,000 ha | 2,917 | - | 505,510.90 | 1.28 | 173.00 |

| Los Alerces* | 263,000 ha | 444 | - | 434,334.79 | 1.65 | 979.00 |

| Copahue* | 90,000 ha | 500 | - | 127,500.00 | 1.42 | 255.00 |

| Los Glaciares* | 600,000 ha | 179 | - | 58,400.00 | .09 | 326.00 |

| Perito Moreno* | 115,000 ha | 49 | - | _ | _ | _ |

* Created as national reserves for the creation of future national parks by presidential decree 105433 of May 11, 1937. Law 13895 of September 20, 1949, transformed all the reserves into national parks, except for Copahue, which became a provincial park in 1963.

As a park, Iguazú was created in the same mold as Nahuel Huapi and the other Argentine national parks of the 1930s and 1940s. They were all conceptualized as instruments for the development and Argentinization of borderlands. Like Nahuel Huapi, Iguazú was devised to promote tourism and attract settlers to the border. The difference between the two parks was quantitative, not qualitative, as Bustillo’s preference for Nahuel Huapi diverted resources from Iguazú. Still, this preference was somewhat mitigated by the pressure of local players such as Acuña and Amarante who insistently pushed the Argentine national park agency in Buenos Aires for more significant investments in the area. Bustillo’s own view of Iguazú as a destination of minor importance revealed poor foresight, as Iguazú would grow to become the most visited national park in Argentina and would be designated a UNESCO natural heritage site, in 1984.

Development versus Conservation

All the infrastructure developed by the DPN in Nahuel Huapi, and on a lesser scale in Iguazú, revealed a philosophy that subordinated conservation to tourism, nationalization, and colonization. Bustillo recognized that, internationally, national park policy lacked a clear doctrine, which freed him to embrace an “eclectic” view of protected areas as catalysts for border development. He understood that tourism would inevitably demand intervention in the form of infrastructure work in protected areas. He also doubted the existence of “unspoiled” natural spaces as defended by most national park proponents at the time. Therefore, in Bustillo’s mind national park development, colonization, and conservation could and should all go together. He pointed out that even Yellowstone, a major inspiration for national parks in Argentina, had once yielded to the pressure of tourism, with its park officials putting up a “circus” with “indigenous camps” and “tamed bears” for visitors. He was not interested in such excesses, but as he saw it, there was no point in adopting a model of strict nature protection if such an approach posed a threat to a country’s sovereignty or brought harm to its economy.Footnote 56

Bustillo’s opinion on the primacy of development over conservation was far from hegemonic. A small group of agricultural and life scientists, including Gustavo Eppens, the head of the DPN’s Technical Division, believed national parks should prioritize protecting nature against human action. DPN scientists such as Eppens were conversant on international debates about conservation and preservation of nature. Bustillo, however, viewed them as an orthodox wing inside the national park agency. Clashes between conservationists and development boosters erupted several times early on in the DPN’s existence. In 1935, for example, General Alonso Baldrich and Colonel Rómulo E. Butty, the two military members of the DPN’s board of directors, proposed to set aside 48,000 of the 55,000 hectares assigned to the agency in Iguazú for settler colonization. They suggested dividing the area into twenty-five-hectare rural lots to be leased to tenants (according to the national park law, the land could not be legally sold). To Baldrich and Butty, there was no point in preserving a recently logged area lacking natural features if only a 2,000-hectare protective buffer around the falls was needed to maintain the park’s aesthetic appeal for tourism. They believed the national park commission had recommended the purchase of the entire 75,000-hectare estate only to make the national park bill more appealing. They contested Gustavo Eppens’s insistence that 50,000 hectares be designated as a protected national park.Footnote 57 Setting aside such a large part of the estate for conservation would be a mistake, the two military men argued, as it would create a “desert” of people in an area primed for colonization.Footnote 58

Despite his commitment to colonization, Bustillo was also a pragmatic man, and after consultation on the matter with the first park director, Julio Amarante, he decided to discard Baldrich and Butty’s proposal. Amarante, who was not a conservationist himself, explained that the military’s idea was nonsensical. Both army and state agents had for years tried to attract farmers to the region, with only partial success. He informed Bustillo that Iguazú was not an appropriate site for the type of colonization practiced in the rest of Argentina: the region had no natural pastures, and settlers would be unable to engage in cattle ranching as they did elsewhere in the country. Moreover, Amarante pointed out that the region’s typical agriculture was based on permanent crops, which required a large investment in infrastructure and machinery. Finally, the estate was adjacent to vast expanses of public land, which were easily available to settlers for purchase, not leasing. Interested parties would prefer to settle in an area where they could acquire land instead of inside the park, where land tenure would be limited to temporary contracts. In sum, to Amarante, the two military men’s plan was doomed to failure.Footnote 59

The conflict resurfaced again with the suggestion, made at the end of 1939 by the park’s second director, Balbino Brañas, of “rational exploitation” of the wild yerba mate groves located inside the park. Brañas was a journalist from Posadas who had acted as provisional director of the Nahuel Huapi (1936) and Lanín (1937) national parks before taking office at Iguazú.Footnote 60 In setting the definitive park boundaries, Brañas saw an opportunity for the national park agency to profit from the exploitation of the yerba mate groves. He planned to commission a third party to harvest yerba mate leaves deep in the forest. The director of the park believed that up to 150,000 kilograms of yerba mate could be processed annually, generating income for both the national park and the military colony.

At first, the head of the DPN and the military both liked the idea of exploiting yerba mate. Surprisingly, it fell to the regulatory agency in charge of the production and commerce of yerba mate, the Comisión Reguladora de la Producción y Comercio de la Yerba Mate (Regulatory Commission for the Production and Commerce of Yerba Mate), to criticize the proposal on conservationist grounds. Federico L. Ezcurra, the head of the agency, came forward to explain that granting a license for a yerba mate operation in the area would not only violate the extant ban on new yerba mate licenses (a ban that had been put in place to deal with an overproduction crisis) but also bring gangs of “reckless laborers” and “precarious encampments” to a national park whose mission was to keep the forest intact. There was also opposition to the proposal inside the DPN, with agency staff claiming that their mission was to preserve nature for tourism and science, not to exploit natural resources. As they saw it, having concessionaires operating in a protected area, however “rational” those commercial activities might be, meant a slippery slope toward allowing other less judicious agents in, which could radically alter the natural conditions of the park.Footnote 61

The polarization on the nature of national parks in Argentina was stronger between outside environmentalists and the agency, with Bustillo calling the former “idiots” in his 1968 memoir.Footnote 62 In Argentina, the two most distinguished environmentalists during Bustillo’s tenure as the head of the DPN were the French-Argentine physician Georges Dennler de la Tour and the German-Argentine physician Hugo Salomon. Both were members of the Comisión Nacional Protectora de la Fauna Sudamericana (National Commission for South American Fauna), which had Salomon as its president.Footnote 63 They believed parks should be created exclusively to preserve endangered species, particularly fauna, a model of conservation that soon became the new international paradigm for national parks after the creation, in 1948, of the International Union for the Protection of Nature, an organization Salomon helped found.Footnote 64

In a 1943 article, Dennler de la Tour proposed the creation of new national parks in the north of Argentina, in the territories of Chaco and Formosa. The locations of these new parks, unlike those of the parks established by the DPN to that point, would be determined by biological criteria, with a focus on the protection of specific fauna and flora species instead of the conservation of natural monuments. Dennler de la Tour also proposed an eastward expansion of Iguazú National Park, which he thought to be too small to protect its fauna. The new park boundaries would encompass the entire area between its present eastern border and the international boundary with Brazil. Hunting had already been prohibited in the park thanks to the pressure of Dennler de la Tour and Salomon, who had managed to secure the passage of several laws banning hunting during that period.Footnote 65 In fact, if not for the pressure of those conservationists, the DPN under Bustillo would have continued to turn a blind eye to the sale of wild animal hides and dead butterflies in the park, and wildlife would still have been kept in cages for tourists in a mini-zoo at the park headquarters. Bustillo himself was oblivious to the conservationists’ plea to protect native animal species and once gladly accepted the offer of two jaguar hides sent to him by park director Amarante.Footnote 66 For Dennler de la Tour the problem of the Argentine national parks went beyond hunting, as he vehemently opposed the DPN’s policy of promoting urban development on park lands. He argued that the agency should evict all settlers living in Iguazú National Park, including those in Puerto Aguirre, and should shut down most of the roads and trails the park had inherited from the logging era, leaving just those necessary to serve tourists’ access to the falls.Footnote 67

Dennler de la Tour’s proposal could not have come at a worse time. Not only had urban development been a key feature of Argentine national parks since their inception, but after 1940 it had become a source of revenue. A funding crisis that year forced the national park agency to sell lots inside the parks to balance its budget. The national park act of 1934 provided for the sale of public land inside a 5,000-hectare area inside national parks to develop urban settlements, which could generate some revenue for the agency. The DPN also profited from fishing and hunting permits, concessions to hotels and tourism agencies, and visitor fees. There was also 2,500,000 pesos in government bonds issued by the national park act to fund infrastructure projects in the parks. Yet the primary source of funding came from 50 percent of the tax on all the tickets for overseas trips sold in Argentina, which had been allocated by the national park act to fund the DPN.Footnote 68

As we can see in Table 1.4, before 1940, income from the overseas tax represented about 87 percent of the agency’s total revenue (excluding the bonds). But the war in Europe in 1939 put the agency in deep financial trouble: as Argentines stopped traveling to their preferred destinations in Europe, revenue from the overseas tax shrank to less than half. The DPN compensated for this loss of external tax income with an increase in revenue from entry fees, concessions, and the sale of land, especially in Nahuel Huapi.

Table 1.4 DPN’s revenue share, 1935–42 (in peso moneda nacional)

| Period | Overseas Travel Tax | % | DPN’s Own Revenue* | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1935 | 669,500.62 | 94 | 43,438.71 | 6 | 712,939.33 |

| 1936 | 935,512.48 | 86 | 155,820.24 | 14 | 1,091,332.72 |

| 1937 | 1,084,981.52 | 86 | 169,752.04 | 14 | 1,254,733.56 |

| 1938 | 1,219,301.95 | 87 | 184,450.77 | 13 | 1,403,752.72 |

| 1939 | 1,072,587.20 | 87 | 155,876.68 | 13 | 1,228,463.88 |

| 1940 | 425,176.30 | 49 | 433,811.98 | 51 | 858,988.28 |

| 1941 | 413,673.30 | 58 | 290,092.11 | 42 | 703,765.41 |

| 1942 | 176,162.29 | 41 | 420,373.23 | 59 | 1,362,535.52 |

| Total | 5,996,895.66 | 69 | 1,853,615.76 | 31 | 8,616,511.42 |

* The sources for DPN revenue were sale of public land; concessions for building, grazing, hunting, fishing, and operating services; sale of railroad tickets; leasing of land; land development services (land measurement, land registration, sale of plans); and fines.

Bustillo was, nevertheless, extremely unhappy with the situation and started lobbying the government and the Congress for an expansion in the DPN government bonds funding, from 2,500,000 to 4,000,000 pesos. To get the new funding approved by an increasingly recalcitrant Congress, he resorted to extreme maneuvers, such as delivering a resignation letter in 1942, which was refused by the Ministry of Agriculture. The bill with the new funding was voted into law, but his tenure as the head of the DPN was coming to a close. With the 1943 military coup, Bustillo became isolated politically and definitively resigned from his position as director of the DPN in 1944.Footnote 69

A Uniquely Argentine National Park

Bustillo’s tenure as the head of the DPN coincided with the perception that Argentina was lagging behind its international rivals in the race to control territory and nationalize borders. The establishment of Iguazú National Park in 1934 was an attempt to reverse that trend and reassert Argentina’s claim to its border with Brazil. Argentina created one of its first national parks both to control its side of the magnificent Iguazu Falls and as a response to the earlier creation of a military colony across the border in Brazil. The park was conceived as a means to take possession of and occupy a borderland that, in the eyes of Argentine leaders, was threatened by cross-border influences. For more than three decades this combination of conservation ideas and geopolitical thinking would guide the territorial policies employed in Iguazú National Park, helping to shape broader ideas of territory and nationhood throughout the country.

The Iguazu Falls, for its magnitude and beauty, comprised the fulcrum of the nationalization of the borderland. Argentine and foreign elites coming from Buenos Aires enjoyed easy river access to the falls, which contributed to a nascent tourism industry beginning in the early 1900s. Buenos Aires’s direct access to the borderland gave Argentina an advantage over Brazil, whose river connection to its own southwestern border was cut by the Iguazu and the Sete Quedas Falls (the latter on the Paraná River). Still, Argentine policymakers understood tourism as incapable of carrying out the desired Argentinization of a border area still sparsely populated. Only federally funded colonization projects, such as the one they saw across the border in Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, could accomplish their vision of a frontier populated by Argentine nationals. In this sense, the demand for border control led to the development of a uniquely Argentine national park model that blended colonization and conservation in frontier areas.

Iguazú National Park fomented innovative ways of promoting territorial occupation. The 1934 national park law had provided for the parceling and sale of sections of national park land to encourage the development of border settlements. Thus, from the 1940s on, the Iguazú National Park administration promoted settlement inside the park, and by 1960, almost 3,000 people lived inside park boundaries.Footnote 70 Argentine national park proponents consciously distanced themselves from their North American and European counterparts, conceiving parks like Iguazú (adjacent to Brazil) and Nahuel Huapi (adjacent to Chile) as tools for colonizing and occupying borderlands. The colonization mission of Iguazú National Park was no accident, as it was already present in the second plan designed by Thays in 1911. From the beginning, national parks in Argentina included as part of their mission the development of population centers and the establishment of infrastructure for dwellers inside park boundaries.

The men in charge of the DPN, therefore, concurred with the military and with local politicians on the need to use the new national park policy to both preserve natural monuments and secure border zones via the development of tourism and settlements. In the 1940s, dissenting voices of conservationists such as Dennler de la Tour and Eppens, although important in curbing the extremes of the policy of border development, were still too weak to challenge the DPN’s main tenets. Still, the near consensus around national park policy did little to harmonize the view of different institutional agents on the importance of a park that Exequiel Bustillo saw as secondary to his main focus on Patagonia.

In the end, the establishment of Iguazú National Park in Argentina owed much of its success to pressure from local players such as territorial governor Acuña and park director Amarante. Iguazú was conceptualized at the federal level as a geopolitical tool of national intervention in the country’s borders with Brazil. But the park was implemented only after the involvement of locals who, in every step of the process, demanded from the central government a commitment to the creation of the park. Across the border, the state government in Brazil would also play a crucial role in lobbying the Brazilian federal government to gazette its Iguaçu National Park in 1939. The two largest countries in South America, therefore, went through similar processes of national park creation that were fueled by federal interest in borderland intervention but whose implementation depended on the active engagement of local elites.