1. Introduction

In the tropical forests of New Guinea, the Etoro believe that for a boy to achieve manhood he must ingest the semen of his elders. This is accomplished through ritualized rites of passage that require young male initiates to fellate a senior member (Herdt 1984/1993; Kelley Reference Kelley1980). In contrast, the nearby Kaluli maintain that male initiation is only properly done by ritually delivering the semen through the initiate's anus, not his mouth. The Etoro revile these Kaluli practices, finding them disgusting. To become a man in these societies, and eventually take a wife, every boy undergoes these initiations. Such boy-inseminating practices, which are enmeshed in rich systems of meaning and imbued with local cultural values, were not uncommon among the traditional societies of Melanesia and Aboriginal Australia (Herdt 1984/1993), as well as in Ancient Greece and Tokugawa Japan.

Such in-depth studies of seemingly “exotic” societies, historically the province of anthropology, are crucial for understanding human behavioral and psychological variation. However, this target article is not about these peoples. It is about a truly unusual group: people from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD)Footnote 1 societies. In particular, it is about the Western, and more specifically American, undergraduates who form the bulk of the database in the experimental branches of psychology, cognitive science, and economics, as well as allied fields (hereafter collectively labeled the “behavioral sciences”). Given that scientific knowledge about human psychology is largely based on findings from this subpopulation, we ask just how representative are these typical subjects in light of the available comparative database. How justified are researchers in assuming a species-level generality for their findings? Here, we review the evidence regarding how WEIRD people compare with other populations.

We pursued this question by constructing an empirical review of studies involving large-scale comparative experimentation on important psychological or behavioral variables. Although such larger-scale studies are highly informative, they are rather rare, especially when compared to the frequency of species-generalizing claims. When such comparative projects were absent, we relied on large assemblies of studies comparing two or three populations, and, when available, on meta-analyses.

Of course, researchers do not implicitly assume psychological or motivational universality with everything they study. The present review does not address those phenomena assessed by individual difference measures for which the guiding assumption is variability among populations. Phenomena such as personal values, emotional expressiveness, and personality traits are expected a priori to vary across individuals, and by extension, societies. Indeed, the goal of much research on these topics is to identify the ways that people and societies differ from one another. For example, a number of large projects have sought to map out the world on dimensions such as values (Hofstede Reference Hofstede2001; Inglehart et al. Reference Inglehart, Basanez and Moreno1998; Schwartz & Bilsky Reference Schwartz and Bilsky1990), personality traits (e.g., McCrae et al. 2005; Schmitt et al. Reference Schmitt, Allik, McCrae, Benet-Martinez, Alcaly, Ault, Austers, Bennett, Bianchi, Boholst, Cunen, Braeckman, Brainerd, Gerard, Caron, Casullo, Cunningham, Daibo, de Backer, Desouza, Diaz-Loving, Diniz, Durkin, Echegaray, Eremsoy, Euler, Falzon, Fisher, Foley, Fry, Fry, Ghayar, Giri, Golden, Grammer, Grimaldi, Halberstadt, Hague, Herrera, Hertel, Hoffmann, Hooper, Hradilekova, Jaafar, Jankauskaite, Kabanagu-Stahel, Kardum, Khoury, Kwon, Laidra, Laireiter, Lakerveld, Lampert, Lauri, Lavallee, Lee, Leung, Locke, Locke, Luksik, Magaisa, Marcinkeviciene, Mata, Mata, McCarthy, Mills, Mikhize, Moreira, Moreira, Moya, Munyae, Noller, Olimar, Opre, Panayiotou, Petrovic, Poels, Popper, Poulimenou, P'yatokh, Raymond, Reips, Reneau, Rivera-Aragon, Rowatt, Ruch, Rus, Safir, Salas, Sambataro, Sandnabba, Schulmeyer, Schutz, Scrimali, Shackelford, Sharan, Shaver, Sichona, Simonetti, Sineshaw, Sookdew, Spelman, Spyron, Sumer, Sumer, Supekova, Szlendak, Taylor, Timmermans, Tooke, Tsaousis, Tungaranza, Van Overwalle, Vandermassen, Vanhoomissen, Vanwesenbeeck, Vasey, Verissimo, Voracek, Wan, Wang, Weiss, Wijaya, Woertman, Youn and Zupaneic2007), and levels of happiness, (e.g., Diener et al. Reference Diener, Diener and Diener1995). Similarly, we avoid the vast psychopathology literature, which finds much evidence for both variability and universality in psychological pathologies (Kleinman Reference Kleinman1988; Tseng Reference Tseng2001), because this work focuses on individual-level (and unusual) variations in psychological functioning. Instead, we restrict our exploration to those domains which have largely been assumed, at least until recently, to be de facto psychological universals.

Finally, we also do not address societal-level behavioral universals, or claims thereof, related to phenomena such as dancing, fire making, cooking, kinship systems, body adornment, play, trade, and grammar, for two reasons. First, at this surface level alone, such phenomena do not make specific claims about universal underlying psychological or motivational processes. Second, systematic, quantitative, comparative data based on individual-level measures are typically lacking for these domains.

Our examination of the representativeness of WEIRD subjects is necessarily restricted to the rather limited database currently available. We have organized our presentation into a series of telescoping contrasts showing, at each level of contrast, how WEIRD people measure up relative to the available reference populations. Our first contrast compares people from modern industrialized societies with those from small-scale societies. Our second telescoping stage contrasts people from Western societies with those from non-Western industrialized societies. Next, we contrast Americans with people from other Western societies. Finally, we contrast university-educated Americans with non–university-educated Americans, or university students with non-student adults, depending on the available data. At each level we discuss behavioral and psychological phenomena for which there are available comparative data, and we assess how WEIRD people compare with other samples.

We emphasize that our presentation of telescoping contrasts is only a rhetorical approach guided by the nature of the available data. It should not be taken as capturing any unidimensional continuum, or suggesting any single theoretical explanation for the variation. Throughout this article we take no position regarding the substantive origins of the observed differences between populations. While many of the differences are probably cultural in nature in that they were socially transmitted (Boyd & Richerson Reference Boyd and Richerson1985; Nisbett et al. Reference Nisbett, Peng, Choi and Norenzayan2001), other differences are likely environmental and represent some form of non-cultural phenotypic plasticity, which may be developmental or facultative, as well as either adaptive or maladaptive (Gangestad et al. Reference Gangestad, Haselton and Buss2006; Tooby & Cosmides Reference Tooby, Cosmides, Barkow, Cosmides and Tooby1992). Other population differences could arise from genetic variation, as observed for lactose processing (Beja-Pereira et al. Reference Beja-Pereira, Luikart, England, Bradley, Jann, Bertorelle, Chamberlain, Nunes, Metodiev, Ferrand and Erhardt2003). Regardless of the reasons underlying these population differences, our concern is whether researchers can reasonably generalize from WEIRD samples to humanity at large.

Many radical versions of interpretivism and cultural relativity deny any shared commonalities in human psychologies across populations (e.g., Gergen Reference Gergen1973; see critique and discussion in Slingerland Reference Slingerland2008, Ch. 2). To the contrary, we expect humans from all societies to share, and probably share substantially, basic aspects of cognition, motivation, and behavior. As researchers who see great value in applying evolutionary thinking to psychology and behavior, we have little doubt that if a full accounting were taken across all domains among peoples past and present, the number of similarities would indeed be large, as much ethnographic work suggests (e.g., Brown Reference Brown1991) – ultimately, of course, this is an empirical question. Thus, our thesis is not that humans share few basic psychological properties or processes; rather, we question our current ability to distinguish these reliably developing aspects of human psychology from more developmentally, culturally, or environmentally contingent aspects of our psychology given the disproportionate reliance on WEIRD subjects. Our aim here, then, is to inspire efforts to place knowledge of such universal features of psychology on a firmer footing by empirically addressing, rather than a priori dismissing or ignoring, questions of population variability.

2. Background

Before commencing with our telescoping contrasts, we first discuss two observations regarding the existing literature: (1) The database in the behavioral sciences is drawn from an extremely narrow slice of human diversity; and (2) behavioral scientists routinely assume, at least implicitly, that their findings from this narrow slice generalize to the species.

2.1. The behavioral sciences database is narrow

Who are the people studied in behavioral science research? A recent analysis of the top journals in six subdisciplines of psychology from 2003 to 2007 revealed that 68% of subjects came from the United States, and a full 96% of subjects were from Western industrialized countries, specifically those in North America and Europe, as well as Australia and Israel (Arnett Reference Arnett2008). The make-up of these samples appears to largely reflect the country of residence of the authors, as 73% of first authors were at American universities, and 99% were at universities in Western countries. This means that 96% of psychological samples come from countries with only 12% of the world's population.

Even within the West, however, the typical sampling method for experimental studies is far from representative. In the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, the premier journal in social psychology – the subdiscipline of psychology that should (arguably) be the most attentive to questions about the subjects' backgrounds – 67% of the American samples (and 80% of the samples from other countries) were composed solely of undergraduates in psychology courses (Arnett Reference Arnett2008). In other words, a randomly selected American undergraduate is more than 4,000 times more likely to be a research participant than is a randomly selected person from outside of the West. Furthermore, this tendency to rely on undergraduate samples has not decreased over time (Peterson Reference Peterson2001; Wintre et al. Reference Wintre, North and Sugar2001). Such studies are therefore sampling from a rather limited subpopulation within each country (see Rozin Reference Rozin2001).

It is possible that the dominance of American authors in psychology publications just reflects that American universities have the resources to attract the best international researchers, and that similar tendencies exist in other fields. However, psychology is a distinct outlier here: 70% of all psychology citations come from the United States – a larger percentage than any of the other 19 sciences that were compared in one extensive international survey (see May Reference May1997). In chemistry, by contrast, the percentage of citations that come from the United States is only 37%. It seems problematic that the discipline in which there are the strongest theoretical reasons to anticipate population-level variation is precisely the discipline in which the American bias for research is most extreme.

Beyond psychology and cognitive science, the subject pools of experimental economics and decision science are not much more diverse – still largely dominated by Westerners, and specifically Western undergraduates. However, to give credit where it is due, the nascent field of experimental economics has begun taking steps to address the problem of narrow samples.Footnote 2

In sum, the available database does not reflect the full breadth of human diversity. Rather, we have largely been studying the nature of WEIRD people, a certainly narrow and potentially peculiar subpopulation.

2.2. Researchers often assume their findings are universal

Sampling from a thin slice of humanity would be less problematic if researchers confined their interpretations to the populations from which they sampled. However, despite their narrow samples, behavioral scientists often are interested in drawing inferences about the human mind and human behavior. This inferential step is rarely challenged or defended – with important exceptions (e.g., Medin & Atran Reference Medin and Atran2004; Rozin Reference Rozin2001; Triandis Reference Triandis1994; Witkin & Berry Reference Witkin and Berry1975) – despite the lack of any general effort to assess how well results from WEIRD samples generalize to the species. This lack of epistemic vigilance underscores the prevalent, though implicit, assumption that the findings one derives from a particular sample will generalize broadly; one adult human sample is pretty much the same as the next.

Leading scientific journals and university textbooks routinely publish research findings claiming to generalize to “humans” or “people” based on research done entirely with WEIRD undergraduates. In top journals such as Nature and Science, researchers frequently extend their findings from undergraduates to the species – often declaring this generalization in their titles. These contributions typically lack even a cautionary footnote about these inferential extensions.

In psychology, much of this generalization is implicit. A typical article does not claim to be discussing “humans” but will rather simply describe a decision bias, psychological process, set of correlations, and so on, without addressing issues of generalizability, although findings are often linked to “people.” Commonly, there is no demographic information about the participants, aside from their age and gender. In recent years there is a trend to qualify some findings with disclaimers such as “at least within Western culture,” though there remains a robust tendency to generalize to the species. Arnett (Reference Arnett2008) notes that psychologists would surely bristle if journals were renamed to more accurately reflect the nature of their samples (e.g., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology of American Undergraduate Psychology Students). They would bristle, presumably, because they believe that their findings generalize much beyond this sample. Of course, there are important exceptions to this general tendency, as some researchers have assembled a broad database to provide evidence for universality (Buss Reference Buss1989; Daly & Wilson Reference Daly and Wilson1988; Ekman Reference Ekman, Dalgleish and Power1999b; Elfenbein & Ambady Reference Elfenbein and Ambady2002; Kenrick & Keefe Reference Kenrick and Keefe1992a; Tracy & Matsumoto Reference Tracy and Matsumoto2008).

When is it safe to generalize from a narrow sample to the species? First, if one had good empirical reasons to believe that little variability existed across diverse populations in a particular domain, it would be reasonable to tentatively infer universal processes from a single subpopulation. Second, one could make an argument that as long as one's samples were drawn from near the center of the human distribution, then it would not be overly problematic to generalize across the distribution more broadly – at least the inferred pattern would be in the vicinity of the central tendency of our species. In the following, with these assumptions in mind, we review the evidence for the representativeness of findings from WEIRD people.

3. Contrast 1: Industrialized societies versus small-scale societies

Our theoretical perspective, which is informed by evolutionary thinking, leads us to suspect that many aspects of people's psychological repertoire are universal. However, the current empirical foundations for our suspicions are rather weak because the database of comparative studies that include small-scale societies is scant, despite the obvious importance of such societies in understanding both the evolutionary history of our species and the potential impact of diverse environments on our psychology. Here we first discuss the evidence for differences between populations drawn from industrialized and small-scale societies in some seemingly basic psychological domains, and follow this with research indicating universal patterns across this divide.

3.1. Visual perception

Many readers may suspect that tasks involving “low-level” or “basic” cognitive processes such as vision will not vary much across the human spectrum (Fodor Reference Fodor1983). However, in the 1960s an interdisciplinary team of anthropologists and psychologists systematically gathered data on the susceptibility of both children and adults from a wide range of human societies to five “standard illusions” (Segall et al. Reference Segall, Campbell and Herskovits1966). Here we highlight the comparative findings on the famed Müller-Lyer illusion, because of this illusion's importance in textbooks, and its prominent role as Fodor's indisputable example of “cognitive impenetrability” in debates about the modularity of cognition (McCauley & Henrich Reference McCauley and Henrich2006). Note, however, that population-level variability in illusion susceptibility is not limited to the Müller-Lyer illusion; it was also found for the Sander-Parallelogram and both Horizontal-Vertical illusions.

Segall et al. (Reference Segall, Campbell and Herskovits1966) manipulated the length of the two lines in the Müller-Lyer illusion (Fig. 1) and estimated the magnitude of the illusion by determining the approximate point at which the two lines were perceived as being of the same length. Figure 2 shows the results from 16 societies, including 14 small-scale societies. The vertical axis gives the “point of subjective equality” (PSE), which measures the extent to which segment “a” must be longer than segment “b” before the two segments are judged equal in length. PSE measures the strength of the illusion.

Figure 1. The Müller-Lyer illusion. The lines labeled “a” and “b” are the same length. Many subjects perceive line “b” as longer than line “a”.

Figure 2. Müller-Lyer results for Segall et al.'s (1966) cross-cultural project. PSE (point of subjective equality) is the percentage that segment a must be longer than b before subjects perceived the segments as equal in length. Children were sampled in the 5-to-11 age range.

The results show substantial differences among populations, with American undergraduates anchoring the extreme end of the distribution, followed by the South African-European sample from Johannesburg. On average, the undergraduates required that line “a” be about a fifth longer than line “b” before the two segments were perceived as equal. At the other end, the San foragers of the Kalahari were unaffected by the so-called illusion (it is not an illusion for them). While the San's PSE value cannot be distinguished from zero, the American undergraduates' PSE value is significantly different from all the other societies studied.

As discussed by Segall et al., these findings suggest that visual exposure during ontogeny to factors such as the “carpentered corners” of modern environments may favor certain optical calibrations and visual habits that create and perpetuate this illusion. That is, the visual system ontogenetically adapts to the presence of recurrent features in the local visual environment. Because elements such as carpentered corners are products of particular cultural evolutionary trajectories, and were not part of most environments for most of human history, the Müller-Lyer illusion is a kind of culturally evolved by-product (Henrich Reference Henrich and Brown2008).

These findings highlight three important considerations. First, this work suggests that even a process as apparently basic as visual perception can show substantial variation across populations. If visual perception can vary, what kind of psychological processes can we be sure will not vary? It is not merely that the strength of the illusory effect varies across populations – the effect cannot be detected in two populations. Second, both American undergraduates and children are at the extreme end of the distribution, showing significant differences from all other populations studied; whereas, many of the other populations cannot be distinguished from one another. Since children already show large population-level differences, it is not obvious that developmental work can substitute for research across diverse human populations. Children likely have different developmental trajectories in different societies. Finally, this provides an example of how population-level variation can be useful for illuminating the nature of a psychological process, which would not be as evident in the absence of comparative work.

3.2. Fairness and cooperation in economic decision-making

By the mid-1990s, researchers were arguing that a set of robust experimental findings from behavioral economics were evidence for a set of evolved universal motivations (Fehr & Gächter Reference Fehr and Gächter1998; Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, McCabe and Smith1998). Foremost among these experiments, the Ultimatum Game provides a pair of anonymous subjects with a sum of real money for a one-shot interaction. One of the pair – the proposer – can offer a portion of this sum to the second subject, the responder. Responders must decide whether to accept or reject the offer. If a responder accepts, she gets the amount of the offer and the proposer takes the remainder; if she rejects, both players get zero. If subjects are motivated purely by self-interest, responders should always accept any positive offer; knowing this, a self-interested proposer should offer the smallest non-zero amount. Among subjects from industrialized populations – mostly undergraduates from the United States, Europe, and Asia – proposers typically offer an amount between 40% and 50% of the total, with a modal offer of 50% (Camerer Reference Camerer2003). Offers below about 30% are often rejected.

With this seemingly robust empirical finding in their sights, Nowak et al. (Reference Nowak, Page and Sigmund2000) constructed an evolutionary analysis of the Ultimatum Game. When they modeled the Ultimatum Game exactly as played, they did not get results matching the undergraduate findings. However, if they added reputational information, such that players could know what their partners did with others on previous rounds of play, the analysis predicted offers and rejections in the range of typical undergraduate responses. They concluded that the Ultimatum Game reveals humans' species-specific evolved capacity for fair and punishing behavior in situations with substantial reputational influence. But, since the Ultimatum Game is typically played one-shot without reputational information, Nowak et al. argued that people make fair offers and reject unfair offers because their motivations evolved in a world where such interactions were not fitness relevant – thus, we are not evolved to fully incorporate the possibility of non-reputational action in our decision-making, at least in such artificial experimental contexts.

Recent comparative work has dramatically altered this initial picture. Two unified projects (which we call Phase 1 and Phase 2) have deployed the Ultimatum Game and other related experimental tools across thousands of subjects randomly sampled from 23 small-scale human societies, including foragers, horticulturalists, pastoralists, and subsistence farmers, drawn from Africa, Amazonia, Oceania, Siberia, and New Guinea (Henrich et al. 2005; Reference Henrich, McElreath, Ensminger, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2006; Reference Henrich, Ensminger, McElreath, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2010). Three different experimental measures show that people in industrialized societies consistently occupy the extreme end of the human distribution. Notably, people in some of the smallest-scale societies, where real life is principally face-to-face, behaved in a manner reminiscent of Nowak et al.'s analysis before they added the reputational information. That is, these populations made low offers and did not reject.

To concisely present these diverse empirical findings, we show results only from the Ultimatum and Dictator Games in Phase II. The Dictator Game is the same as the Ultimatum Game except that the second player cannot reject the offer. If subjects are motivated purely by self-interest, they would offer zero in the Dictator Game. Thus, Dictator Game offers yield a measure of “fairness” (equal divisions) among two anonymous people. By contrast, Ultimatum Game offers yield a measure of fairness combined with an assessment of the likelihood of rejection (punishment). Rejections of offers in the Ultimatum Game provide a measure of people's willingness to punish unfairness.

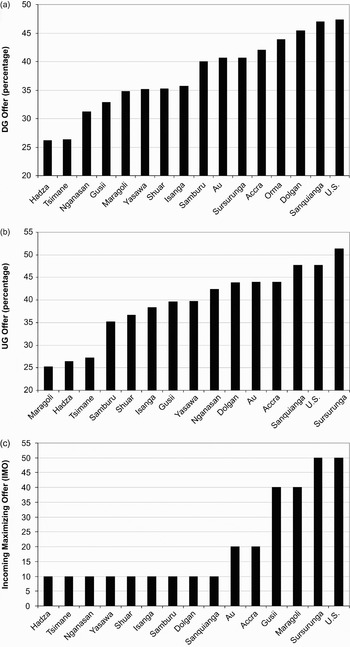

Using aggregate measures, Figure 3 shows that the behavior of the U.S. adult (non-student) sample occupies the extreme end of the distribution in each case. For Dictator Game offers, Figure 3A shows that the U.S. sample has the highest mean offer, followed by the Sanquianga from Colombia, who are renowned for their prosociality (Kraul Reference Kraul2008). The U.S. offers are nearly double that of the Hadza, foragers from Tanzania, and the Tsimane, forager-horticulturalists from the Bolivian Amazon. Figure 3B shows that for Ultimatum Game offers, the United States has the second highest mean offer, behind the Sursurunga from Papua New Guinea. On the punishment side in the Ultimatum Game, Figure 3C shows the income-maximizing offers (IMO) for each population, which is a measure of the population's willingness to punish inequitable offers. IMO is the offer that an income-maximizing proposer would make if he knew the probability of rejection for each of the possible offer amounts. The U.S. sample is tied with the Sursurunga. These two groups have an IMO five times higher than 70% of the other societies. While none of these measures indicates that people from industrialized societies are entirely unique vis-à-vis other populations, they do show that people from industrialized societies consistently occupy the extreme end of the human distribution.

Figure 3. Behavioral measures of fairness and punishment from the Dictator and Ultimatum Games for 15 societies (Phase II). Figures 3A and 3B show mean offers for each society in the Dictator and Ultimatum Games, respectively. Figure 3C gives the income-maximizing offer (IMO) for each society.

Analyses of these data show that a population's degree of market integration and its participation in a world religion both independently predict higher offers, and account for much of the variation between populations. Community size positively predicts greater punishment (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, Ensminger, McElreath, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2010). The authors suggest that norms and institutions for exchange in ephemeral interactions culturally coevolved with markets and expanding larger-scale sedentary populations. In some cases, at least in their most efficient forms, neither markets nor large populations were feasible before such norms and institutions emerged. That is, it may be that what behavioral economists have been measuring among undergraduates in such games is a specific set of social norms, culturally evolved for dealing with money and strangers, that have emerged since the origins of agriculture and the rise of complex societies.

In addition to differences in populations' willingness to reject offers that are too low, the evidence also indicates a willingness to reject offers that are too high in about half the societies studied. This tendency to reject so-called hyper-fair offers rises as offers increase from 60% to 100% of the stake (Henrich et al. Reference Henrich, McElreath, Ensminger, Barr, Barrett, Bolyanatz, Cardenas, Gurven, Gwako, Henrich, Lesorogol, Marlowe, Tracer and Ziker2006). This phenomenon, which is not observed in typical undergraduate subjects (who essentially never reject offers greater than half), has now emerged among populations in Russia (Bahry & Wilson Reference Bahry and Wilson2006) and China (Hennig-Schmidt et al. Reference Hennig-Schmidt, Li and Yang2008), as well as (to a lesser degree) among non-student adults in Sweden (Wallace et al. Reference Wallace, Cesarini, Lichtenstein and Johannesson2007), Germany (Guth et al. Reference Guth, Schmidt and Sutter2003), and the Netherlands (Bellemare et al. Reference Bellemare, Kröger and Van Soest2008). Attempts to explain away this phenomenon as a consequence of confusion or misunderstanding, have not found support despite substantial efforts.

Suppose that Nowak and his coauthors were Tsimane, and that the numerous empirical findings they had on hand were all from Tsimane villages. If this were the case, presumably these researchers would have simulated the Ultimatum Game and found that there was no need to add reputation to their model. This unadorned evolutionary solution would have worked fine until they realized that the Tsimane are not representative of humanity. According to the above data, the Tsimane are about as representative of the species as are Americans, but at the opposite end of the spectrum. If the database of the behavioral sciences consisted entirely of Tsimane subjects, researchers would likely be quite concerned about generalizability.

3.3. Folkbiological reasoning

Recent work in small-scale societies suggests that some of the central conclusions regarding the development and operation of human folkbiological categorization, reasoning, and induction are limited to urban subpopulations of non-experts in industrialized societies. Although much more work needs to be done, it appears that typical subjects (children of WEIRD parents) develop their folkbiological reasoning in a culturally and experientially impoverished environment, by contrast to those of small-scale societies (and of our evolutionary past), distorting both the species-typical pattern of cognitive development and the patterns of reasoning in WEIRD adults.

Cognitive scientists using (as subjects) children drawn from U.S. urban centers – often those surrounding universities – have constructed an influential, though actively debated, developmental theory in which folkbiological reasoning emerges from folkpsychological reasoning. Before age 7, urban children reason about biological phenomena by analogy to, and by extension from, humans. Between ages 7 and 10, urban children undergo a conceptual shift to the adult pattern of viewing humans as one animal among many. These conclusions are underpinned by three robust findings from urban children: (1) Inferential projections of properties from humans are stronger than projections from other living kinds; (2) inferences from humans to mammals emerge as stronger than inferences from mammals to humans; and (3) children's inferences violate their own similarity judgments by, for example, providing stronger inference from humans to bugs than from bugs to bees (Carey Reference Carey1985; Reference Carey, Sperber, Premack and Premack1995).

However, when the folkbiological reasoning of children in rural Native American communities in Wisconsin and Yukatek Maya communities in Mexico was investigated (Atran et al. Reference Atran, Medin, Lynch, Vapnarsky, Ucan and Sousa2001; Ross et al. Reference Ross, Medin, Coley and Atran2003; Waxman & Medin Reference Waxman and Medin2007) none of these three empirical patterns emerged. Among the American urban children, the human category appears to be incorporated into folkbiological induction relatively late compared to these other populations. The results indicate that some background knowledge of the relevant species is crucial for the application and induction across a hierarchical taxonomy (Atran et al. Reference Atran, Medin, Lynch, Vapnarsky, Ucan and Sousa2001). In rural environments, both exposure to and interest in the natural world is commonplace, unavoidable, and an inevitable part of the enculturation process. This suggests that the anthropocentric patterns seen in U.S. urban children result from insufficient cultural input and a lack of exposure to the natural world. The only real animal that most urban children know much about is Homo sapiens, so it is not surprising that this species dominates their inferential patterns. Since such urban environments are highly “unnatural” from the perspective of human evolutionary history, any conclusions drawn from subjects reared in such informationally impoverished environments must remain rather tentative. Indeed, studying the cognitive development of folkbiology in urban children would seem the equivalent of studying “normal” physical growth in malnourished children.

This deficiency of input likely underpins the fact that the basic-level folkbiological categories for WEIRD adults are life-form categories (e.g., bird, fish, and mammal), and these are also the first categories learned by WEIRD children – for example, if one says “What's that?” (pointing at a maple tree), their common answer is “tree.” However, in all small-scale societies studied, the generic species (e.g., maple, crow, trout, and fox) is the basic-level category and the first learned by children (Atran Reference Atran1993; Berlin Reference Berlin1992).

Impoverished interactions with the natural world may also distort assessments of the typicality of natural kinds in categorization. The standard conclusion from American undergraduate samples has been that goodness of example, or typicality, is driven by similarity relations. A robin is a typical bird because this species shares many of the perceptual features that are commonly found in the category BIRD. In the absence of close familiarity with natural kinds, this is the default strategy of American undergraduates, and psychology has assumed it is the universal pattern. However, in samples which interact with the natural world regularly, such as Itza Maya villagers, typicality is based not on similarity but on knowledge of cultural ideals, reflecting the symbolic or material significance of the species in that culture. For the Itza, the wild turkey is a typical bird because of its rich cultural significance, even though it is in no way most similar to other birds. The same pattern holds for similarity effects in inductive reasoning – WEIRD people make strong inferences from computations of similarity, whereas populations with greater familiarity with the natural world, despite their capacity for similarity-based inductions, prefer to make strong inferences from folkbiological knowledge that takes into account ecological context and relationships among species (Atran et al. Reference Atran, Medin and Ross2005). In general, research suggests that what people think about can affect how they think (Bang et al. Reference Bang, Medin and Atran2007). To the extent that there is population-level variability in the content of folkbiological beliefs, such variability affects cognitive processing in this domain as well.

So far we have emphasized differences in folkbiological cognition uncovered by comparative research. This same work has also uncovered reliably developing aspects of human folkbiological cognition that do not vary, such as categorizing plants and animals in a hierarchical taxonomy, or that the generic species level has the strongest inductive potential, despite the fact that this level is not always the basic level across populations, as discussed above. Our goal in emphasizing the differences here is to show (1) how peculiar industrialized (urban, in this case) samples are, given the unprecedented environment they grow up in; and (2) how difficult it is to conclude a priori what aspects will be reliably developing and robust across diverse slices of humanity if research is largely conducted with WEIRD samples.

3.4. Spatial cognition

Human societies vary in their linguistic tools for, and cultural practices associated with, representing and communicating (1) directions in physical space, (2) the color spectrum, and (3) integer amounts. There is some evidence that each of these differences in cultural content may influence some aspects of nonlinguistic cognitive processes (D'Andrade Reference D'Andrade1995; Gordon Reference Gordon2004; Kay Reference Kay2005; Levinson Reference Levinson2003; Roberson et al. Reference Roberson, Davies and Davidoff2000). Here we focus on spatial cognition, for which the evidence is most provocative. As above, it appears that industrialized societies are at the extreme end of the continuum in spatial cognition. Human populations show differences in how they think about spatial orientation and deal with directions, and these differences may be influenced by linguistically based spatial reference systems.

Speakers of English and other Indo-European languages favor the use of an egocentric (relative) system to represent the location of objects – that is, relative to the self (e.g., “the man is on the right side of the flagpole”). In contrast, many if not most languages favor an allocentric frame, which comes in two flavors. Some allocentric languages such as Guugu Yimithirr (an Australian language) and Tzeltal (a Mayan language) favor a geocentric system in which absolute reference is based on cardinal directions (“the man is west of the house”). The other allocentric frame is an object-centered (intrinsic) approach that locates objects in space, relative to some coordinate system anchored to the object (“the man is behind the house”). When languages possess systems for encoding all of these spatial reference frames, they often privilege one at the expense of the others. However, the fact that some languages lack one or more of the reference systems suggests that the accretion of all three systems into most contemporary languages may be a product of long-term cumulative cultural evolution.

In data on spatial reference systems from 20 languages drawn from diverse societies – including foragers, horticulturalists, agriculturalists, and industrialized populations – only three languages relied on egocentric frames as their single preferred system of reference. All three were from industrialized populations: Japanese, English, and Dutch (Majid et al. Reference Majid, Bowerman, Kita, Haun and Levinson2004).

The presence of, or emphasis on, different reference systems may influence nonlinguistic spatial reasoning (Levinson Reference Levinson2003). In one study, Dutch and Tzeltal speakers were seated at a table and shown an arrow pointing either to the right (north) or the left (south). They were then rotated 180 degrees to a second table where they saw two arrows: one pointing to the left (north) and the other one pointing to the right (south). Participants were asked which arrow on the second table was like the one they saw before. Consistent with the spatial-marking system of their languages, Dutch speakers chose the relative solution, whereas the Tzeltal speakers chose the absolute solution. Several other comparative experiments testing spatial memory and reasoning are consistent with this pattern, although lively debates about interpretation persist (Levinson et al. Reference Levinson, Kita, Haun and Rasch2002; Li & Gleitman Reference Li and Gleitman2002).

Extending the above exploration, Haun and colleagues (Haun et al. 2006a; 2006b) examined performance on a spatial reasoning task similar to the one described above, using children and adults from different societies and great apes. In the first step, Dutch-speaking adults and 8-year-olds (speakers of an egocentric language) showed the typical egocentric bias, whereas Hai//om-speaking adults and 8-year-olds (a Namibian foraging population who speak an allocentric language) showed a typical allocentric bias. In the second step, 4-year-old German-speaking children, gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, and bonobos were tested on a simplified version of the same task. All showed a marked preference for allocentric reasoning. These results suggest that children share with other great apes an innate preference for allocentric spatial reasoning, but that this bias can be overridden by input from language and cultural routines.

If one were to work on spatial cognition exclusively with WEIRD subjects (say, using subjects from the United States and Europe), one might conclude that children start off with an allocentric bias but naturally shift to an egocentric bias with maturation. The problem with this conclusion is that it would not apply to many human populations, and it may be the consequence of studying subjects from peculiar cultural environments. The next telescoping contrast highlights some additional evidence suggesting that WEIRD people may even be unusual in their egocentric bias vis-à-vis most other industrialized populations.

3.5. Other potential differences

We have discussed several lines of data suggesting not only population-level variation, but that industrialized populations are consistently unusual compared to small-scale societies. There are also numerous studies that have found differences between much smaller numbers of samples (usually two samples). In these studies it is impossible to discern who is unusual, the small-scale society or the WEIRD population. For example, one study found that both samples from two different industrialized populations were risk-averse decision makers when facing monetary gambles involving gains (Henrich & McElreath Reference Henrich and McElreath2002), whereas both samples from small-scale societies were risk-prone. Risk-aversion for monetary gains may be a recent, local phenomenon. Similarly, extensive inter-temporal choice experiments using a panel method of data collection indicates that the Tsimane, an Amazonian population of forager-horticulturalists, discount the future 10 times more steeply than do WEIRD people (Godoy et al. Reference Godoy, Byron, Reyes-Garcia, Leonard, Patel, Apaza, Perez, Vadez and Wilkie2004). In Uganda, a study of individual decision-making among small-scale farmers showed qualitatively different deviations from expected utility maximization than is typically found among undergraduates. For example, rather than the inverse S-shape for probabilities in Prospect Theory, a regular S-shape was found.Footnote 3

3.6. Similarities between industrialized and small-scale societies

Some larger-scale comparative projects show universal patterns in human psychology. Here we list some noteworthy examples:

-

1. Some perceptual illusions: We discussed the Müller-Lyer illusion above. However, there are illusions, such as the Perspective Drawing Illusion, for which the industrialized populations are not extreme outliers, and for which perception varies little in the populations studied (Segall et al. Reference Segall, Campbell and Herskovits1966).

-

2. Perceiving color: While the number of basic color terms systematically varies across human languages (Regier et al. Reference Regier, Kay and Cook2005), the ability to perceive different colors does emerge in small-scale societies (Rivers Reference Rivers and Haddon1901a),Footnote 4 although terms and categories do influence color perception at the margins (Kay & Regier Reference Kay and Regier2006).

-

3. Emotional expression: In studying facial displays of emotions, Ekman and colleagues have shown much evidence for universality in recognition of the “basic” facial expressions of emotions, although this work has included only a small – yet convincing – sampling of small-scale societies (Ekman Reference Ekman, Dalgleish and Power1999a; Reference Ekman, Dalgleish and Power1999b). There is also evidence for the universality of pride displays (Tracy & Matsumoto Reference Tracy and Matsumoto2008; Tracy & Robins Reference Tracy and Robins2008). This main effect for emotional recognition across population (58% of variance) is qualified by a smaller effect for cultural specificity of emotional expressions (9% of variance: Elfenbein & Ambady Reference Elfenbein and Ambady2002).

-

4. False belief tasks: Comparative work in China, the United States, Canada, Peru, India, Samoa, and Thailand suggests that the ability to explicitly pass the false belief task emerges in all populations studied (Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Rochat, Lillard, Claux, Odden, Itakura, Tapanya and Singh2005; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wellman, Tardif and Sabbagh2008), although the age at which subjects can pass the explicit version of the false belief task varies from 4 to at least 9 (Boesch Reference Boesch2007; Callaghan et al. Reference Callaghan, Rochat, Lillard, Claux, Odden, Itakura, Tapanya and Singh2005; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Wellman, Tardif and Sabbagh2008), with industrialized populations at the extreme low end.

-

5. Analog numeracy: There is growing consensus in the literature on numerical thinking that quantity estimation relies on a primitive “analog” number sense that is sensitive to quantity but limited in accuracy. This cognitive ability appears to be independent of counting practices and was shown to operate in similar ways among two Amazonian societies with very limited counting systems (Gordon Reference Gordon2004; Pica et al. Reference Pica, Lerner, Izard and Dehaene2004), as well as in infants and primates (e.g., Dehaene Reference Dehaene1997).

-

6. Social relationships: Research on the cognitive processes underlying social relationships reveals similar patterns across distinct populations. Fiske (Reference Fiske1993) studied people's tendency to confuse one person with another (e.g., intending to phone your son Bob but accidentally calling your son Fred). Chinese, Korean, Bengali, and Vai (Liberia and Sierra Leone) immigrants tended to confuse people in the same category of social relationship. Interestingly, the social categories in which the most confusion occurred varied across populations.

-

7. Psychological essentialism: Research from a variety of societies, including Vezo children in Madagascar (Astuti et al. Reference Astuti, Solomon and Carey2004), children from impoverished neighborhoods in Brazil (Sousa et al. Reference Sousa, Atran and Medin2002), Menominee in Wisconsin (Waxman et al. Reference Waxman, Medin and Ross2007), and middle-class children and adults in the United States (Gelman Reference Gelman2003), shows evidence of perceiving living organisms as having an underlying and non-trivial nature that makes them what they are. Psychological essentialism also extends to the understanding of social groups, which may be found in Americans (Gelman Reference Gelman2003), rural Ukranians (Kanovsky Reference Kanovsky2007), Vezo in Madagascar (Astuti Reference Astuti2001), Mapuche farmers in Chile (Henrich & Henrich, unpublished manuscript), Iraqi Chaldeans and Hmong immigrants in Detroit (Henrich & Henrich Reference Henrich and Henrich2007), and Mongolian herdsmen (Gil-White Reference Gil-White2001). Notably, this evidence is not well suited to examining differences in the degree of psychological essentialism across populations, though it suggests that inter-population variation may be substantial.

There are also numerous studies involving dyadic comparisons between a single small-scale society and a Western population (or a pattern of Western results) in which cross-population similarities have been found. Examples are numerous but include the development of an understanding of death (Barrett & Behne Reference Barrett and Behne2005), shame (Fessler Reference Fessler2004),Footnote 5 and cheater detection (Sugiyama et al. Reference Sugiyama, Tooby and Cosmides2002). Finding evidence for similarities across two such disparate populations is an important step towards providing evidence for universality (Norenzayan & Heine Reference Norenzayan and Heine2005); however, the case would be considerably stronger if it was found across a larger number of diverse populations.Footnote 6

3.7. Summary for Contrast 1

Although there are several domains in which the data from small-scale societies appear similar to that from industrialized societies, comparative projects involving visual illusions, social motivations (fairness), folkbiological cognition, and spatial cognition all show industrialized populations as outliers. Given all this, it seems problematic to generalize from industrialized populations to humans more broadly, in the absence of supportive empirical evidence.

4. Contrast 2: WesternFootnote 7 versus non-Western societies

For our second contrast, we review evidence comparing Western with non-Western populations. Here we examine four of the most studied domains: social decision making (fairness, cooperation, and punishment), independent versus interdependent self-concepts (and associated motivations), analytic versus holistic reasoning, and moral reasoning. We also briefly return to spatial cognition.

4.1. Anti-social punishment and cooperation

In the previous contrast, we reviewed social decision-making experiments showing that industrialized populations occupy the extreme end of the behavioral distribution vis-à-vis a broad swath of smaller-scale societies. Here we show that even among industrialized populations, Westerners are again clumped at the extreme end of the behavioral distribution. Notably, the behaviors measured in the experiments discussed below are strongly correlated with the strength of formal institutions, norms of civic cooperation, and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita.

In 2002, Fehr and Gächter published their classic paper, “Altruistic Punishment in Humans,” in Nature, based on Public Goods Games with and without punishment, conducted with undergraduates at the University of Zurich. The paper demonstrated that adding the possibility of punishment to a cooperative dilemma dramatically altered the outcome, from a gradual slide towards little cooperation (and rampant free-riding), to a steady increase towards stable cooperation. Enough subjects were willing to punish non-cooperators at a cost to themselves to shift the balance from free-riding to cooperation. In stable groups this cooperation-punishment combination dramatically increases long-run gains (Gächter et al. 2008).

To examine the generalizability of these results, which many took to be a feature of our species, Herrmann, Thoni, and Gächter conducted systematic comparable experiments among undergraduates from a diverse swath of industrialized populations (Herrmann et al. Reference Herrmann, Thoni and Gächter2008). In these Public Goods Games, subjects played with the same four partners for 10 rounds and could contribute during each round to a group project. All contributions to the group project were multiplied by 1.6 and distributed equally among all partners. Players could also pay to punish other players by taking money away from them.

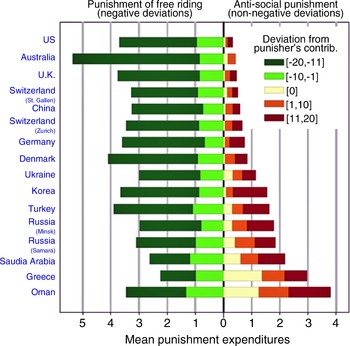

In addition to finding population-level differences in the subjects' initial willingness to cooperate, Gächter's team unearthed in about half of these samples a phenomenon that is not observed beyond a trivial degree among typical undergraduate subjects (see our Fig. 4): Many subjects engaged in anti-social punishment; that is, they paid to reduce the earnings of “overly” cooperative individuals (those who contributed more than the punisher did). The effect of this behavior on levels of cooperation was dramatic, completely compensating for the cooperation-inducing effects of punishment in the Zurich experiment. Possibilities for altruistic punishment do not generate high levels of cooperation in these populations. Meanwhile, participants from a number of Western countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, behaved like the original Zurich students. Thus, it appears that the Zurich sample works well for generalizing to the patterns of other Western samples (as well as the Chinese sample), but such findings cannot be readily extended beyond this.

Figure 4. Mean punishment expenditures from each sample for a given deviation from the punisher's contribution to the public good. The deviations of the punished subject's contribution from the punisher's contribution are grouped into five intervals, where [-20,-11] indicates that the punished subjects contributed between 11 and 20 less than the punishing subject; [0] indicates that the punished subject contributed exactly the same amount as the punishing subject; and [1,10] ([11,20]) indicates that the punished subject contributed between 1 and 10 (11 and 20) more than the punishing subject. Adapted from Herrmann et al. (Reference Herrmann, Thoni and Gächter2008).

4.2. Independent and interdependent self-concepts

Much psychological research has explored the nature of people's self-concepts. Self-concepts are important, as they organize the information that people have about themselves, direct attention to information that is perceived to be relevant, shape motivations, influence how people appraise situations that influence their emotional experiences, and guide their choices of relationship partners. Markus and Kitayama (Reference Markus and Kitayama1991) posited that self-concepts can take on a continuum of forms stretching between two poles, termed independent and interdependent self-views, which relate to the individualism-collectivism construct (Triandis Reference Triandis1989; Reference Triandis1994). Do people conceive of themselves primarily as self-contained individuals, understanding themselves as autonomous agents who consist largely of component parts, such as attitudes, personality traits, and abilities? Or do they conceive of themselves as interpersonal beings intertwined with one another in social webs, with incumbent role-based obligations towards others within those networks? The extent to which people perceive themselves in ways similar to these independent or interdependent poles has significant consequences for a variety of emotions, cognitions, and motivations.

Much research has underscored how Westerners have more independent views of self than non-Westerners. For example, research using the Twenty Statements Test (Kuhn & McPartland Reference Kuhn and McPartland1954) reveals that people from Western populations (e.g., Australians, Americans, Canadians, Swedes) are far more likely to understand their selves in terms of internal psychological characteristics, such as their personality traits and attitudes, and are less likely to understand them in terms of roles and relationships, than are people from non-Western populations, such as Native Americans, Cook Islanders, Maasai and Samburu (both African pastoralists), Malaysians, and East Asians (for a review, see Heine Reference Heine2008). Studies using other measures (Hofstede Reference Hofstede1980; Morling & Lamoreaux Reference Morling and Lamoreaux2008; Oyserman et al. Reference Oyserman, Coon and Kemmelmeier2002; Triandis et al. Reference Triandis, McCusker and Hui1990) provide convergent evidence that Westerners tend to have more independent, and less interdependent, self-concepts than those of other populations. These data converge with much ethnographic observation, in particular Geertz's (1975, p. 48) claim that the Western self is “a rather peculiar idea within the context of the world's cultures.”

There are numerous psychological patterns associated with self-concepts. For example, people with independent self-concepts are more likely to demonstrate (1) positively biased views of themselves; (2) a heightened valuation of personal choice; and (3) an increased motivation to “stand out” rather than to “fit in.” Each of these represents a significant research enterprise, and we discuss them in turn.

4.2.1. Positive self-views

The most widely endorsed assumption regarding the self is that people are motivated to view themselves positively. Roger Brown (Reference Brown1986) famously declared this motivation to maintain high self-esteem an “urge so deeply human, we can hardly imagine its absence” (p. 534). The strength of this motivation has been perhaps most clearly documented by assessing the ways that people go about exaggerating their self-views by engaging in self-serving biases, in which people view themselves more positively than objective benchmarks would justify. For example, in one study, 94% of American professors rated themselves as better than the average American professor (Cross Reference Cross1977). However, meta-analyses reveal that these self-serving biases tend to be more pronounced in Western populations than in non-Western ones (Heine & Hamamura Reference Heine and Hamamura2007; Mezulis et al. Reference Mezulis, Abramson, Hyde and Hankin2004) – for example, Mexicans (Tropp & Wright Reference Tropp and Wright2003), Native Americans (Fryberg & Markus Reference Fryberg and Markus2003), Chileans (Heine & Raineri Reference Heine and Raineri2009), and Fijians (Rennie & Dunne Reference Rennie and Dunne1994) score much lower on various measures of positive self-views than do Westerners (although there are some exceptions to this general pattern; see Harrington & Liu Reference Harrington and Liu2002). Indeed, in some cultural contexts, most notably East Asian ones, evidence for self-serving biases tends to be null, or in some cases, shows significant reversals, with East Asians demonstrating self-effacing biases (Heine & Hamamura Reference Heine and Hamamura2007). At best, the sharp self-enhancing biases of Westerners are less pronounced in much of the rest of the world, although self-enhancement has long been discussed as if it were a fundamental aspect of human psychology (e.g., Rogers Reference Rogers1951; Tesser Reference Tesser and Berkowitz1988).

4.2.2. Personal choice

Psychology has long been fascinated with how people assert agency by making choices (Bandura Reference Bandura1982; Kahneman & Tversky Reference Kahneman and Tversky2000; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2004), and has explored the efforts that people go through to ensure that their actions feel freely chosen and that their choices are sensible. However, there is considerable variation across populations in the extent to which people value choice and in the range of behaviors over which they feel that they are making choices. For example, one study found that European-American children preferred working on a task, worked on it longer, and performed better on it, if they had made some superficial choices regarding the task than if others made the same choices for them. In contrast, Asian-American children were equally motivated by the task if a trusted other made the same choices for them (Iyengar & Lepper Reference Iyengar and Lepper1999). Another two sets of studies found that Indians were slower at making choices, were less likely to make choices consistent with their personal preferences, and were less likely to view their actions as expressions of choice, than were Americans (Savani et al. Reference Savani, Markus and Conner2008; in press). Likewise, the extent to which people feel that they have much choice in their lives varies across populations. Surveys conducted at bank branches in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and the United States found that Americans were more likely to perceive having more choice at their jobs than were subjects from the other countries (Iyengar & DeVoe Reference Iyengar, DeVoe, Murphy-Berman and Berman2003). Another survey administered in more than 40 countries found, in general, that feelings of free choice in one's life were considerably higher in Western nations (e.g., Finland, the United States, and Northern Ireland) than in various non-Western nations (e.g., Turkey, Japan, and Belarus: Inglehart et al. Reference Inglehart, Basanez and Moreno1998). This research reveals that perceptions of choice are experienced less often, and are a lesser concern, among those from non-Western populations.

4.2.3. Motivations to conform

Many studies have explored whether motivations to conform are similar across populations by employing a standard experimental procedure (Asch Reference Asch and Guetzkow1951; Reference Asch1952). In these studies, which were initially conducted with Americans, participants first hear a number of confederates making a perceptual judgment that is obviously incorrect, and then participants are given the opportunity to state their own judgment. A majority of American participants were found to go along with the majority's incorrect judgment at least once. This research sparked much interest, apparently because Westerners typically feel that they are acting on their own independent resolve and are not conforming. A meta-analysis of studies performed in 17 societies (Bond & Smith Reference Bond and Smith1996), including subjects from Oceania, the Middle East, South America, Africa, South America, East Asia, Europe, and the United States, found that motivations for conformity are weaker in Western societies than elsewhere. Other research converges with this conclusion. For example, Kim and Markus (Reference Kim and Markus1999) found that Koreans preferred objects that were more common, whereas Americans showed a greater preference for objects that were more unusual.

4.3. Analytic versus holistic reasoning

Variation in favored modes of reasoning has been compared across several populations. Most of the research has contrasted Western (American, Canadian, Western European) with East Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean) populations with regard to their relative reliance on what is known as “holistic” versus “analytic” reasoning (Nisbett Reference Nisbett2003; Peng & Nisbett Reference Peng and Nisbett1999). However, growing evidence from other non-Western populations points to a divide between Western nations and most everyone else, including groups as diverse as Arabs, Malaysians, and Russians (see Norenzayan et al. [2007] for a review), as well as subsistence farmers in Africa and South America and sedentary foragers (Norenzayan et al., n.d.; Witkin & Berry Reference Witkin and Berry1975), rather than an East-West divide.

Holistic thought involves an orientation to the context or field as a whole, including attention to relationships between a focal object and the field, and a preference for explaining and predicting events on the basis of such relationships. Analytic thought involves a detachment of objects from contexts, a tendency to focus on objects' attributes, and a preference for using categorical rules to explain and predict behavior. This distinction between habits of thought rests on a theoretical partition between two reasoning systems. One system is associative, and its computations reflect similarity and contiguity (i.e., whether two stimuli share perceptual resemblances and co-occur in time); the other system relies on abstract, symbolic representational systems, and its computations reflect a rule-based structure (e.g., Neisser Reference Neisser1963; Sloman Reference Sloman1996).

Although both cognitive systems are available in all normal adults, different environments, experiences, and cultural routines may encourage reliance on one system at the expense of the other, giving rise to population-level differences in the use of these different cognitive strategies to solve identical problems. There is growing evidence that a key factor influencing the prominence of analytic versus holistic cognition is the different self-construals prevalent across populations. First, independent self-construal primes facilitate analytic processing, whereas interdependent primes facilitate holistic processing (Oyserman & Lee Reference Oyserman and Lee2008). Second, geographic regions with greater prevalence of interdependent self-construals show more holistic processing, as can be seen in comparisons of Northern and Southern Italians, Hokkaido and mainland Japanese, and Western and Eastern Europeans (Varnum et al. Reference Varnum, Grossmann, Kitayama and Nisbett2008).

Furthermore, the analytic approach is culturally more valued in Western contexts, whereas the holistic approach is more valued in East Asian contexts, leading to normative judgments about cognitive strategies that differ across the respective populations (Buchtel & Norenzayan Reference Buchtel and Norenzayan2008). Below we highlight some findings from this research showing that, compared to diverse populations of non-Westerners, Westerners (1) attend more to objects than fields; (2) explain behavior in more decontextualized terms; and (3) rely more on rules over similarity relations to classify objects (for further discussion of the cross-cultural evidence, see Nisbett Reference Nisbett2003; Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Choi, Peng and Cohen2007).

-

1. Using evidence derived from the Rod & Frame Test and Embedded Figures Test, Witkin and Berry (Reference Witkin and Berry1975) summarize a wide range of evidence from migratory and sedentary foraging populations (Arctic, Australia, and Africa), sedentary agriculturalists, and industrialized Westerners. Only Westerners and migratory foragers consistently emerged at the field-independent end of the spectrum. Recent work among East Asians (Ji et al. Reference Ji, Nisbett and Zhang2004) in industrialized societies using the Rod & Frame Test, the Framed Line Test (Kitayama et al. Reference Kitayama, Duffy, Kawamura and Larsen2003), and the Embedded Figures Test again shows Westerners at the field-independent end of the spectrum, compared to field-dependent East Asians, Malays, and Russians (Kuhnen et al. Reference Kuhnen, Hannover, Roeder, Shah, Schubert, Upmeyer and Zakaria2001). Similarly, Norenzayan et al. (Reference Norenzayan, Choi, Peng and Cohen2007) found that Canadians showed less field-dependent processing than did Chinese, who in turn were less field-dependent than were Arabs (also see Zebian & Denny Reference Zebian and Denny2001).

-

2. East Asians' recall for objects is worse than Americans' if the background has been switched (Masuda & Nisbett Reference Masuda and Nisbett2001), indicating that East Asians are attending more to the field. This difference in attention has also been found in saccadic eye-movements as measured with eye-trackers. Americans gaze at focal objects longer than East Asians, who in turn gaze at the background more than Americans (Chua et al. Reference Chua, Boland and Nisbett2005). Furthermore, when performing identical cognitive tasks, East Asians and Westerners show differential brain activation, corresponding to the predicted cultural differences in cognitive processing (Gutchess et al. Reference Gutchess, Welsh, Boduroglu and Park2006; Hedden et al. Reference Hedden, Ketay, Aron, Markus and Gabrieli2008).

-

3. Several classic studies, initially conducted with Western participants, found that “people” tend to make strong attributions about a person's disposition, even when there are compelling situational constraints (Jones & Harris Reference Jones and Harris1967; Ross et al. Reference Ross, Amabile and Steinmetz1977). This tendency to ignore situational information in favor of dispositional information is so commonly observed – among typical subjects – that it was dubbed the “fundamental attribution error” (Ross et al. Reference Ross, Amabile and Steinmetz1977). However, consistent with much ethnography in non-Western cultures (e.g., Geertz Reference Geertz1975), comparative experimental work demonstrates differences that, while Americans attend to dispositions at the expense of situations (Gilbert & Malone Reference Gilbert and Malone1995), East Asians are more likely than Americans to infer that behaviors are strongly controlled by the situation (Miyamoto & Kitayama Reference Miyamoto and Kitayama2002; Morris & Peng Reference Morris and Peng1994; Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Choi and Nisbett2002a; Van Boven et al. Reference Van Boven, Kamada and Gilovich1999), particularly when situational information is made salient (Choi & Nisbett Reference Choi and Nisbett1998).Footnote 8 Grossmann and Varnum (Reference Grossmann and Varnum2010) provides parallel findings with Russians. Likewise, in an investigation of people's lay beliefs about personality across eight populations, Church et al. (Reference Church, Katigbak, Del Prado, Ortiz, Mastor, Harumi, Tanaka-Matsumi, De Jesús Vargas-Flores, Ibáñez-Reyes, White, Miramontes, Reyes and Cabrera2006) found that people from Western populations (i.e., American and Euro-Australian) strongly endorsed the notion that traits remain stable over time and predict behavior over many situations, whereas people from non-Western populations (i.e., Asian-Australian, Chinese-Malaysian, Filipino, Japanese, Mexican, and Malay) more strongly endorsed contextual beliefs about personality, such as ideas suggesting that traits do not describe a person as well as roles or duties do, and that trait-related behavior changes from situation to situation. These patterns are consistent with earlier work on attributions comparing Euro-Americans with Hindu Indians (see Miller Reference Miller1984; Shweder & Bourne Reference Shweder, Bourne, Marsella and White1982). Hence, although dispositional inferences can be found outside the West, the fundamental attribution error seems less fundamental elsewhere (Choi et al. Reference Choi, Nisbett and Norenzayan1999).

-

4. Westerners are also more likely to rely on rules over similarity relations in reasoning and categorization. Chinese subjects were found to be more likely to group together objects which shared a functional (e.g., pencil-notebook) or contextual (e.g., sky-sunshine) relationship, whereas Americans were more likely to group objects together if they belonged to a category defined by a simple rule (e.g., notebook-magazine; Ji et al. Reference Ji, Nisbett and Zhang2004). Similarly, work with Russian students (Grossmann, Reference Grossmann2010) and Russian small-scale farmers (Luria Reference Luria1976) showed strong tendencies for participants to group objects according to their practical functions. This appears widespread, as Norenzayan et al. (n.d.) examined classification among the Mapuche and Sangu subsistence farmers in Chile and Tanzania, respectively, and found that their classification resembled the Chinese pattern, although it was exaggerated towards holistic reasoning.

-

5. In a similar vein, research with East Asians found they were more likely to group objects if the objects shared a strong family resemblance, whereas Americans were more likely to group the same objects if they could be assigned to that group on the basis of a deterministic rule (Norenzayan et al. Reference Norenzayan, Smith, Kim and Nisbett2002b). When those results are compared with Uskul et al.'s (2008) findings from herding, fishing, and tea-farming communities on the Black Sea coast in Turkey – the two studies used the same stimuli – it is evident that European-Americans are again at the extreme (see our Figure 5).

Figure 5. Relative dominance of rule-based versus family resemblance–based judgments of categories for the same cognitive task. European-American, Asian-American, and East Asian university students were tested by Norenzayan et al. (Reference Norenzayan, Smith, Kim and Nisbett2002b); the herders, fishermen, and farmers of Turkey's Black Sea coast were tested by Uskul et al. (Reference Uskul, Kitayama and Nisbett2008). Positive scores indicate a relative bias towards rule-based judgments, whereas negative scores indicate a relative bias towards family resemblance–based judgments. It can be seen that European-American students show the most pronounced bias toward rule-based judgments, and they are outliers in terms of absolute deviation from zero. Adapted from Norenzayan et al. (Reference Norenzayan, Smith, Kim and Nisbett2002b) and Uskul et al. (Reference Uskul, Kitayama and Nisbett2008).

In summary, although analytic and holistic cognitive systems are available to all normal adults, a large body of evidence shows that the habitual use of what are considered “basic” cognitive processes, including those involved in attention, perception, categorization, deductive reasoning, and social inference, varies systematically across populations in predictable ways, highlighting the difference between the West and the rest. Several biases and patterns are not merely differences in strength or tendency, but show reversals of Western patterns. We emphasize, however, that Westerners are not unique in their cognitive styles (Uskul et al. Reference Uskul, Kitayama and Nisbett2008; Witkin & Berry Reference Witkin and Berry1975), but they do occupy the extreme end of the distribution.

4.4. Moral reasoning

A central concern in the developmental literature has been the way people acquire the cognitive foundations of moral reasoning. The most influential approach to the development of moral reasoning has been Kohlberg's (Reference Kohlberg and Lickona1971; Reference Kohlberg1976; Reference Kraul1981), in which people's abilities to reason morally are seen to hinge on cognitive abilities that develop over maturation. Kohlberg proposed that people progressed through the same three levels: (1) Children start out at a pre-conventional level, viewing right and wrong as based on internal standards regarding the physical or hedonistic consequences of actions; (2) then they progress to a conventional level, where morality is based on external standards, such as that which maintains the social order of their group; and finally (3) some progress further to a post-conventional level, where they no longer rely on external standards for evaluating right and wrong, but instead do so on the basis of abstract ethical principles regarding justice and individual rights – the moral code inherent in most Western constitutions.

While all of Kohlberg's levels are commonly found in WEIRD populations, much subsequent research has revealed scant evidence for post-conventional moral reasoning in other populations. One meta-analysis carried out with data from 27 countries found consistent evidence for post-conventional moral reasoning in all the Western urbanized samples, yet found no evidence for this type of reasoning in small-scale societies (Snarey Reference Snarey1985). Furthermore, it is not just that formal education is necessary to achieve Kohlberg's post-conventional level. Some highly educated non-Western populations do not show this post-conventional reasoning. At Kuwait University, for example, faculty members scored lower on Kohlberg's schemes than the typical norms for Western adults, and the elder faculty there scored no higher than the younger ones, contrary to Western patterns (Al-Shehab Reference Al-Shehab2002; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Bersoff and Harwood1990).

Research in moral psychology indicates that typical Western subjects rely principally on justice- and harm/care-based principles in judging morality. However, recent work indicates that non-Western adults and Western religious conservatives rely on a wider range of moral principles than these two dimensions of morality (Baek Reference Baek2002; Haidt & Graham Reference Haidt and Graham2007; Haidt et al. Reference Haidt, Koller and Dias1993; e.g., Miller & Bersoff Reference Miller and Bersoff1992). Shweder et al. (Reference Shweder, Much, Mahapatra, Park, Brandt and Rozin1997) proposed that in addition to a dominant justice-based morality, which they termed an “ethic of autonomy,” there are two other ethics that are commonly found outside the West: an ethic of community, in which morality derives from the fulfillment of interpersonal obligations that are tied to an individual's role within the social order, and an ethic of divinity, in which people are perceived to be bearers of something holy or god-like, and have moral obligations to not act in ways that are degrading to or incommensurate with that holiness. The ethic of divinity requires that people treat their bodies as temples, not as playgrounds, and so personal choices that seem to harm nobody else (e.g., about food, sex, and hygiene) are sometimes moralized (for a further elaboration of moral foundations, see Haidt & Graham Reference Haidt and Graham2007). In sum, the high-socioeconomic status (SES), secular Western populations that have been the primary target of study thus far, appear unusual in a global context, based on their peculiarly narrow reliance, relative to the rest of humanity, on a single foundation for moral reasoning (based on justice, individual rights, and the avoidance of harm to others; cf. Haidt & Graham Reference Haidt and Graham2007).

4.5. Other potential differences

There are many other psychological phenomena in which Western samples differ from non-Western ones; however, at present there are insufficient data in these domains derived from diverse populations to assess where Westerners reside in the human spectrum. For example, compared with Westerners, some non-Westerners (1) have less dynamic social networks, in which people work to avoid negative interactions among their existing networks rather than seeking new relations (Adams Reference Adams2005); (2) prefer lower to higher arousal-positive affective states (Tsai Reference Tsai2007); (3) are less egocentric when they try to take the perspective of others (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Hoshino-Browne, Leung and Zanna2007; Wu & Keysar Reference Wu and Keysar2007); (4) have weaker motivations for consistency (Kanagawa et al. Reference Kanagawa, Cross and Markus2001; Suh Reference Suh2002); (5) are less prone to “social-loafing” (i.e., reducing efforts on group tasks when individual contributions are not being monitored) (Earley Reference Earley1993); (6) associate fewer benefits with a person's physical attractiveness (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Adams and Plaut2008); and (7) have more pronounced motivations to avoid negative outcomes relative to their motivations to approach positive outcomes (Elliot et al. Reference Elliot, Chirkov, Kim and Sheldon2001; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Aaker and Gardner2000).