1 Bringing Shared Leadership to the Fore

The discussion of leadership is omnipresent – of that there is no doubt. Leadership permeates every aspect of our lives, whether we like it or not. But what do we mean when we talk about leadership? Typically, the idea of leadership boils down to the exertion of some type of influence of one person on another person or on a group. For most people the idea of leadership conjures an image of a powerful person projecting influence downward, through an organizational or social hierarchy, onto others designated as followers or subordinates. Figure 1 captures the essence of this perspective on leadership. This weighted view of leadership – usually based on formal, hierarchical position – is generally termed vertical leadership or hierarchical leadership. While this is a very useful way to frame leadership, it is insufficient, at best, and neglects to encompass the vast array of nuance that is part of the enactment of influence between social actors.

Figure 1 Traditional perspective on top-down leadership as a role

Leadership is not just about a hierarchical position; it is not simply a role to play, a position to fill. In fact, many people can be put into formal positions of leadership but not really engage in much actual influence, other than through the administrative power that rests in their position. Their position becomes the mechanism for leadership, not the person. In contrast, there are some people who, while they do not occupy formal leadership positions, can often, through collaborative efforts, be highly influential, possibly enabling entire social movements, changing the course of history (see Pearce & van Knippenberg, Reference Pearce and van Knippenberg2023 for a discussion of the leadership of social innovation). This informal perspective on leadership is generally termed shared leadership, where multiple people rise to the challenge and lead one another.

This book will focus on shared leadership – leadership from informal sources – especially as it relates to the leadership of groups, teams, and organizations. We will explore it as both an informal, naturally occurring phenomenon, but also discuss how to enable more leadership to be shared through intentional, thoughtful decisions on the part of the formal leader, as well as the organizations in which they work. Shared leadership is generally defined “as a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both” (Pearce & Conger, Reference Pearce and Conger2003: 1). Pearce and Conger (Reference Pearce and Conger2003) proffered that vertical leadership was part of the shared leadership process but also suggested that it would be useful to accord it unique status in the analysis of leadership processes. We come back to this issue in Section 5, where we discuss future research directions.

Today most people think of shared leadership as a normal part of the leadership lexicon. The reality, however, is that a clear definition, and thus the scientific study of shared leadership, has only been around for a few decades (Pearce & Conger, Reference Pearce and Conger2003). While it is now an established theoretical perspective used to guide scholarly inquiry into the topic, and as a framework to facilitate practitioner quests to improve organizations, the start of the field was rocky – the first major empirical article on shared leadership, by Pearce and Sims (Reference Pearce and Sims2002), which is now cited more than 2,100 times, was initially met with much significant resistance by the gate keepers of the premier journals of the field. The idea was simply too far from the traditionally accepted norms where the vertical/formal leader held primacy as the main target of study, yet, in reality, sharing leadership has been part of human organizational experience for millennia.

This first study was rejected by most of the major journals in management, applied psychology, and leadership (Academy of Management Journal, Administrative Science Quarterly, Journal of Applied Psychology, Personnel Psychology, and Leadership Quarterly). It ultimately found a home in Group Dynamics, a newer journal, started in 1997 – and thus at the time not nearly as prestigious as the old guard publications – with a focus on small group research and innovation in the field. Yet, even the publishing process at Group Dynamics was not without its hurdles, requiring a challenging set of four rounds of revisions, and a change of editors, before the final acceptance. Over the years, many people have asked why we didn’t publish that article in a “premier” journal, including the more recent editors of Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Applied Psychology, Administrative Science Quarterly, and Personnel Psychology. Our answer has always simply been that we tried … but new thought does not always meet with the formal leader’s (in this case, the leading journals’ editors) approval, as they would be required to shift their mindset away from established norms regarding the source of influence.

It took six years from initial submission of the original Pearce and Sims manuscript to a journal for it to be published in 2002. At the time, the manuscript simply did not fit the predominant paradigm of top-down, vertical leadership. The editors of these journals, at the time, were uniformly encouraging of the novel aspects of the manuscript but, likewise, uniformly concerned that the construct of shared leadership simply was not leadership – they wished us luck in publishing elsewhere and chose to stay embedded in the idea that leadership influence was not a bilateral experience, much less, multidirectional – as we now clearly know it is.

Nonetheless, some form of shared leadership has been practiced in many groups and societies for as long as humans have engaged in complex, social, and creative activities, requiring divergent inputs from diverse individuals to develop breakthrough solutions to intractable problems. For example, the ancient Greeks devised an early system of democracy in an effort to decentralize power and to enable leadership from a broader group of people than was possible under the traditional approach to top-down leadership inherent in a hereditary monarchy. They recognized the latent issues that come with embedding leadership through an accident of birth and created deliberate structures to allow for a shared voice in leading their society. Almost a thousand years later, the Anglo-Saxons developed a structure where their kings were elected through an Assembly, sometimes called the Witenagemot – a group of secular and ecclesiastic delegates – who were then expected to advise the king on policies and laws, based on their personal expertise. The essence of this society was that it was organized with the understanding that influence between the king and assembly was reciprocal, and mutually reliant. This governance structure ended abruptly in 1066 with the Norman invasion and the reversion to the Frankish norms of hereditary kingship, but the people of Britain never quite lost their desire for sharing the lead – hence their rebellion, which culminated in the publication of the Magna Carta in 1215.

In a similar vein, Mandela, in his autobiography, wrote that the core tenets of his leadership style were formulated from watching how his tribal leader would sit silently as his people talked, listening to them, hearing their thoughts and needs, seeing the dynamics that were employed to develop a more complete and complex understanding of a situation, after which, the chief would summarize the discussion, noting where ideas had emerged from, as a mechanism to acknowledge and reward the influence that had been exerted by the various tribal members.

People want to share the lead. It’s not that we don’t recognize that it’s useful to have someone to whom we can point at and say that they are responsible, but it is also in our nature to want to be heard, seen, and valued for our ideas and to be acknowledged as influential. With that said, we will focus this Element on the scientific side of the shared leadership equation, illuminating the progress made to date, as well as articulating promising avenues for future inquiry.

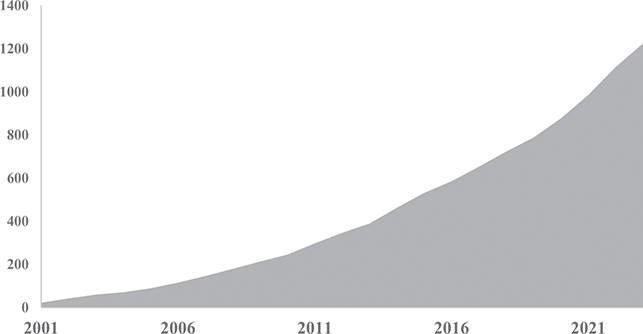

Pearce and colleagues (e.g., Pearce, Reference Pearce1993, Reference Pearce1995, Reference Pearce1997; Pearce & Sims, Reference Pearce, Sims, Beyerlein, Johnson and Beyerlein2000, Reference Pearce and Sims2002; Pearce & Conger, Reference Pearce and Conger2003) are credited as the pioneers in crafting the shared leadership space, especially the Pearce and Sims (Reference Pearce and Sims2002) empirical article on the relative influence of vertical versus shared leadership on team outcomes and the Pearce and Conger (Reference Pearce and Conger2003) book which contained essays on shared leadership from the leading authorities on leadership and teamwork. These two publications are considered the seminal works on shared leadership, marking an inflection point and providing the catalyst for the increasing interest, in the ensuring years, in shared leadership. Since Reference Pearce, Sims, Beyerlein, Johnson and Beyerlein2000, at least 1,225 articles and book chapters on shared leadership have been published in the scientific literature (see Figure 2). What is evident from the graph is that interest in shared leadership theory is on the rise.

Figure 2 Cumulative research publications on shared leadership (2001–2023)

Shared leadership is a philosophical perspective on leadership – with a foundational premise that nearly every single person is capable of leading, at least some of the time. This flies in the face of traditional notions of leadership – that leadership is something inherently special and few people are capable of being leaders. The more traditional concept of leadership has its roots, scientifically, in the “great man” philosophy, suggesting that leaders are rare, and that they are highly unique individuals with natural leadership abilities, and who should then be put into unilateral positions of power to exert downward influence on others, that is, vertical leadership.

While we certainly do not subscribe to the “leadership is rare” ideology, we believe that top-down, vertical leadership is necessary in most human endeavors (see Pearce, Reference Pearce2004; Pearce, van Knippenberg, & van Ginkel, Reference Pearce, van Knippenberg and van Ginkel2023 for a deeper discussion on this issue). We temper this perspective, greatly, however, by also advocating that shared leadership is necessary and, in fact, natural in those same endeavors as evidenced by the unintentional development of shared leadership structures throughout known human history.

With the uptick in interest regarding shared leadership as an area of research has been a proliferation of terms used to capture the notion of shared leadership – terms like collective leadership, distributed leadership, and many others. While we applaud the interest in the space, we caution against this proliferation of terms in both the academic and also in the practitioner literatures as it dis-unifies the definitional discussion for no clear theoretical gain. It typically causes more confusion than it clears up and ends up creating organizational frustration due to missed or misguided expectations. While we believe that this confusion is generally unintentional, it is nevertheless distracting from the value of truly understanding shared leadership. From an individual researcher point of view, however, it is easy to understand how these terms are forwarded – these researchers are attempting to carve out an area of research that becomes associated with their name. Conger and Pearce (Reference Pearce and Jay2003), in an effort to stimulate interest in shared leadership, likely hold a bit of the blame for this proliferation by specifically encouraging “academic entrepreneurism” in the field.

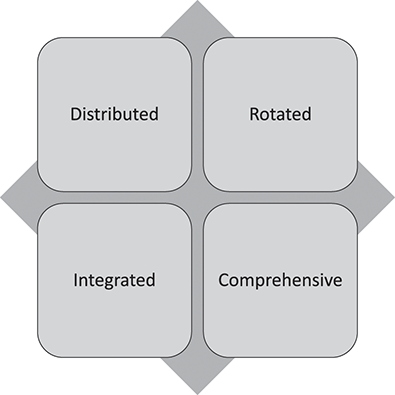

Nevertheless, to establish some order to this burgeoning area, Pearce, Manz, and Sims (Reference Pearce, Manz and Sims2014) provided a framework for understanding the interrelationship of these various terms – identifying special cases of the overarching term of shared leadership: rotated shared leadership, integrated shared leadership, distributed shared leadership, and comprehensive shared leadership (see Figure 3). One could easily identify additional special cases of shared leadership to add to this list (e.g., dyadic shared leadership). Nonetheless, the upshot is that all of these interrelated terms are, in the end, shared leadership. The field would do better to rationalize these terms into the overarching umbrella term of shared leadership, while continuing to explore such special cases. Otherwise, to simply proliferate terms in order to attempt to put a scholarly stake in the ground creates more confusion than it clarifies when it comes to the science of shared leadership.

Figure 3 Primary forms of shared leadership

Notwithstanding the special case of what is termed self-leadership (Manz, Reference Manz1986), the generally understood term of leadership focuses on influence processes between people – that is, a leader who influences and a follower who accepts, influence. Historically, the scientific study of leadership has focused on one part of this equation, that is, just the top-down influence of a designated or appointed leader on someone or some group of people below that person. Nonetheless, even in such circumstances there are almost always additional influence factors in the social situation that are not captured by studying leadership with that singular lens. Shared leadership research addresses this gap and provides a more encompassing view of leadership social dynamics. Leadership implies the existence of influence between people. Shared leadership is an overarching term that encapsulates all leadership social influence: all leadership is shared leadership; it is simply a matter of degree.

Perhaps now, as a continued remedy to this definitional proliferation and concept blur, it would be more useful to conceptualize shared leadership as a meta-theory. Calling it this does not assume that shared leadership assumes primacy or a higher level of importance than other theoretical work on leadership; we believe that calling it this is more of a clarifying description of a theory that can be described as something distinct, but that also permeates many other leadership, or influence based experiences. It is meta also in that shared leadership theory is integrative, or holistic in nature and, as we increasingly develop more sophistication in our models, especially now that so much ground work has been laid (see Sections 3 and 4), it is time to explore how shared leadership can both synthesize and unify varying leadership perspectives more seamlessly, ultimately with the goal of reflecting the organizational experience more accurately.

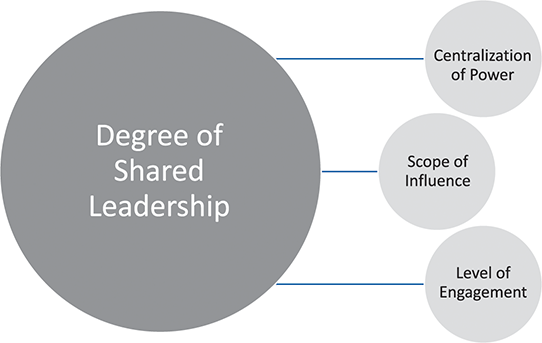

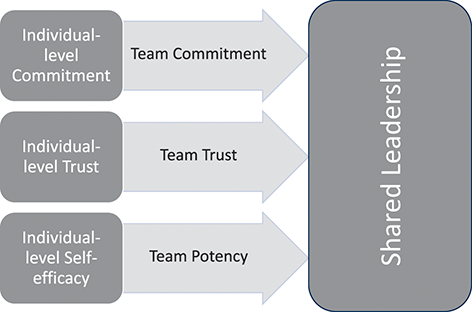

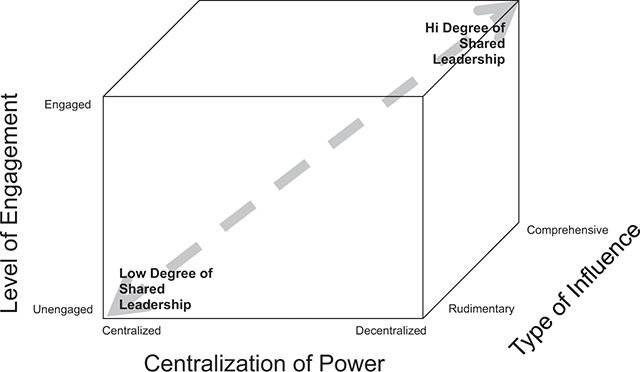

There are several primary dimensions along which leadership is shared. The first, of course, is reasonably straightforward and has to do with the number of people, from the social grouping of interest, involved in influencing one another. Second, we can ascertain the degree of influence the various actors have upon one another. This is also fairly straightforward. Third, we can consider the type of influence the various actors have which is a bit more complex than the first two dimensions. On the one hand, the type of influence might vary between people, which is natural. But, in a more overarching sense it is the range of types of influence that are important here. Figure 4 captures these three components, which comprise the degree of shared leadership inherent in situations.

Figure 4 Underlying dimensions related to the degree of shared leadership

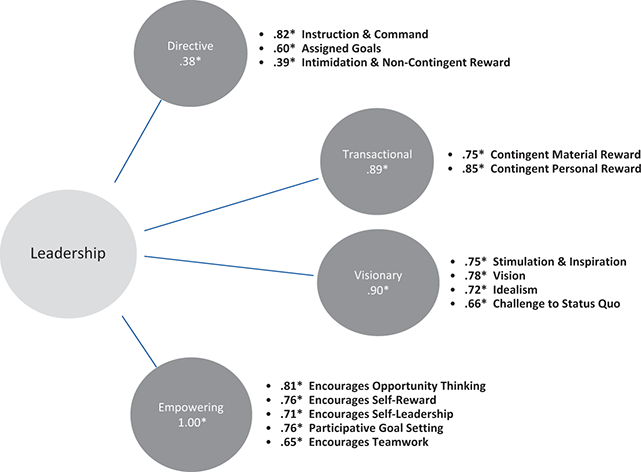

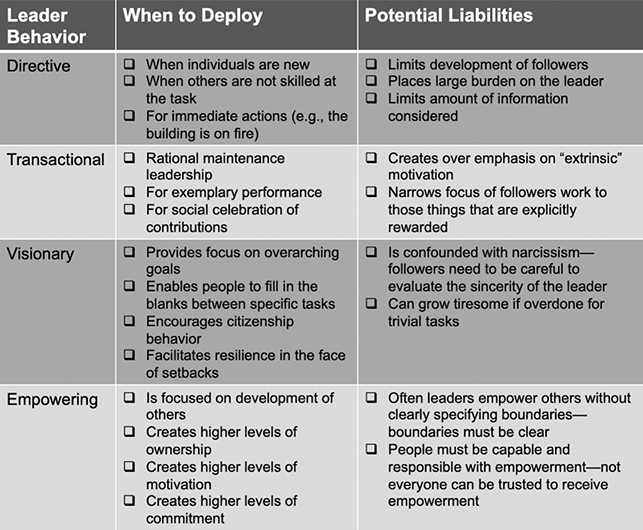

Building on the previous dimensions, there are four fundamental types of leadership influence that can be exerted between people, ranging from directive to transactional, visionary and empowering (see Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Sims and Cox2003 for a thorough discussion). The most common idea is that people would, based on their inclinations, enact the behaviors and attitudes associated with their dominant leadership style without any facility for shifting from one type to another. For example, the most obvious and typically understood type of influence is directive (sometimes referred to as authoritative) leadership. This entails providing instruction and commands to others, and assigning goals and similarly aligned influence strategies. Transactional leadership influence is focused upon setting up reward contingencies for desired outcomes, that is, providing rewards, either material, such as monetary rewards, or more personal rewards, such as recognition and praise, to induce others to engage in a course of action. Visionary leadership is more overarching and long-term oriented (of course visionary leadership is related to the term transformational leadership, but see van Knippenberg and Sitkin (Reference Van Knippenberg and Sitkin2013) for a comprehensive discussion on the scientific issues surrounding transformational leadership). This type of influence is focused on aligning others toward an overarching mission or toward some type of idealized state for the future. Finally, empowering leadership influence processes are focused on developing and unleashing the leadership capabilities of others. Figure 5 illustrates the scientific backdrop of these four encompassing types of leadership behavior and Figure 6 details the more precise components of each type, specifying the application and potential pitfalls of each influence strategy.

Figure 5 Fundamental leadership influence strategies

Figure 6 Deployment and caveats regarding fundamental leadership influence strategies

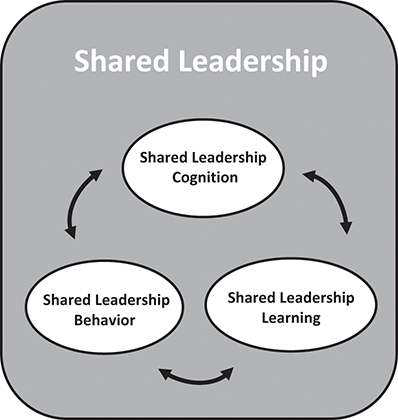

Shared leadership, however, is not just about types of influence behaviors, in isolation. The core dynamics of shared leadership center on shared leadership cognition, shared leadership learning, and shared leadership behavior (van Knippenberg, Pearce & van Ginkel, Reference Van Knippenberg, Pearce and van Ginkel2024). Shared leadership cognition entails mental models people hold when it comes to the enactment of leadership influence processes in social interactions – what they believe to be appropriate ways to engage in influence. Shared leadership learning involves the processes involved in refining shared leadership cognition, in line with training and development, as well as experience and reflection. Shared leadership behavior entails the actual engagement in social influence between social actors and may involve any or all of the various types of influence identified and described in Figure 6, that is, directive, transactional, visionary and empowering leader behaviors. We assert that these three constructs, in concert, form the core dynamics of shared leadership. We elaborate on this assertion in Section 5.

Figure 7 The core dynamics of shared leadership

In the following sections we first provide an analysis of the historical foundations of shared leadership in the management, organizational behavior, and applied psychology literatures. Then, we provide a comprehensive review of the scientific progress on shared leadership, exploring both the antecedents and outcomes of shared leadership. Subsequently, we turn our attention to highlighting the key avenues for future research, clarifying the progress to date in seven research domains relating to shared leadership (Conger & Pearce, Reference Pearce and Jay2003). Next, we proffer advice regarding the practice of shared leadership. Finally, we provide some concluding thoughts on the current state of the field.

2 Historical Bases of Shared Leadership

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, very little intellectual effort was given to the scientific study of leadership. That is not to say that people were not interested in leaders and their sources of influence; it is just that the attempt to evaluate that influence using some sort of scientific method was essentially nonexistent. Still, a great deal about leadership philosophy can be gleaned from the writings of Cicero, or from Machiavelli, who, in his both famous and oftreviled book The Prince, offered leadership advice to hereditary princes and church leaders, but also to a new sort of prince, as he called them – people who we would now call business leaders.

Looking further east, Saladin successfully navigated his rise to leadership between three contentious and competitive empires (Damascus, Baghdad, and Egypt) to build an almost obsessively loyal army, capable of defeating the Crusader armies. A great deal of his success was based on his patient development of a system of trusted aides, who understood clearly what the overall goals were, and who were also given, once their loyalty was proven, an unusual measure of autonomy for how they achieved those goals. Yet even with each of these significant people, the study of leadership was almost always merely anecdotal – that is, until the Industrial Revolution emerged as a global phenomenon.

It was during the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, and more specifically in the late 1700s, we witness the beginnings of the application of the scientific process to all manner of issues that could be converted into productive economic endeavors (Nardinelli, Reference Nardinelli2008). Naturally, the vast majority of these early efforts were more centered upon the hard sciences, with the goal of developing technological advances (Stewart, Reference Stewart1998), particularly as the role of people in the Industrial Revolution were mainly seen as supplementary to the far more interesting mechanical opportunities for the time. With that said, Stewart (Reference Stewart, Fitzpatrick, Jones, Knelworf and McAlmon2003) noted that by the end of the eighteenth century many of those who were considered scientists also began to address the questions related to the measurement of the social and managerial issues involved in organizational activities. There were people like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who, in 1762, wrote The Social Contract (for a translated edition of this work see Rousseau, Reference Rousseau2018). At the time of publication, his work was deeply uncomfortable to many – where he argued against the idea of the hereditary top-down leader, instead advocating for rule “by the people.” He also realized that the scientific focus on technical innovation only offered part of the answer to increased organizational efficiencies, and called for a more holistic focus on the impact of this growth on the humans who were instrumental in this revolution.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the French economist Jean Baptiste Say (Reference Say1803/1964) observed that entrepreneurs “must possess the art of superintendence and administration” (p. 330). Economists, prior to his writing, were largely concerned with land and labor and, to some extent, capital as the important factors of production. Jean Baptiste Say’s initial observations on entrepreneurship catalyzed interest into managerial insights for economic enterprise. Thus, early observations in this space were largely focused on what we would call the command-and-control model of hierarchical leadership (Pearce & Conger, Reference Pearce and Conger2003). It was much later in the nineteenth century that minor hints of the concept of shared leadership could be detected in management writing as an alternative approach to leading groups of people (Pearce & Conger, Reference Pearce and Conger2003). One such reason that the focus was so heavily on the top-down model of leadership was simply that human interaction was considered the province of the sociologists, theologians, and philosophers – which, given the fact that humans are at the core of all organizational interaction and innovation, is an extraordinarily narrow intellectual path. Yet, until quite recently, leadership in organizations was the province of economists, and leadership in societies was for the aptly named humanities to interpret.

Thus, in order to gain a more clear understanding of how the nineteenth century perceived the human side of organizations, it is useful to consider the work of people such as Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1893), who compared leadership emergence in the social structures to two different types of societies: one, where the innate sameness (e.g., shared kinship, history, interdependence, homogeneity, collective responsibility/goals) of the group resulted in the selection of a leader who embodied their own selves; the second, where what he labeled “organic solidarity” as a more dominant form of organizing and where leaders emerge more typically from merit and their demonstrated expertise. This second type of society is characterized by “a system of different organs each of which has a special role, and which are themselves formed of differentiated parts. Not only are social elements not of the same nature, but they are not arranged in the same manner” (cited from Durkheim Reference Durkheim and Bellah1973 translation, pg. 69). He goes on to describe that in this society, there is a moderating/central “organ” but that the rest of the group is coordinated and subordinated both to the central node but also to each other in a web of interdependence. In this society individuals are grouped by the nature of the activity that they contribute to the society – that is, an occupational expertise is necessary to participate in this society, and the amount of expertise and usefulness is how influence is gained, rather than from to whom one is born.

One of the more holistic and thus also pioneering thinkers of the nineteenth century, regarding systematic and integrative approaches to management and leadership, was Daniel C. McCallum. He developed what could be considered the first documented principles of management and leadership that could be widely applied across organizations and industries. One of the principles he articulated focused upon the importance of “unity of command,” where orders originated from the top and were implemented by those at lower levels of the hierarchy (Wren, Reference Wren1994). The overwhelming majority of writing about leadership during the Industrial Revolution focused on this top-down, command-and-control perspective (e.g., Montgomery, Reference Montgomery1836, Reference Montgomery1840). This command-and-control perspective became the globally acknowledged de facto model of leadership advice of the nineteenth century (Wren, Reference Wren1994).

By the turn of the twentieth century the top-down model of leadership was firmly embedded in what became known as “scientific management” (Gantt, Reference Gantt1916; Gilbreth, Reference Gilbreth1912; Gilbreth & Gilbreth, Reference Gilbreth and Gilbreth1917; Taylor, Reference Taylor1903, Reference Taylor1911). However, moving forward into the twentieth century, multiple ideas began to emerge that form the foundation for shared leadership. We identify twenty-four such concepts. These ideas are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Historical contributions to the theoretical foundations of shared leadership theory

| Theory/Research | Key Issues | Representative Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Law of the situation | Let the situation, not the person, determine the “orders.” | Follett (Reference Follett1924) |

| Human relations | One should pay attention to the social and psychological needs of employees. | Mayo (Reference Mayo1933); Bernard (Reference Bernard1938) |

| Social systems perspective | People in organizations are embedded in social systems, which, in turn, influence behavior. | Turner (Reference Turner1933) |

| Role differentiation in groups | Members of groups typically assume different types of roles. | Benne & Sheats (Reference Benne and Sheats1948) |

| Co-leadership – mentor protégé | Concerns the division of the leadership role between two people – primarily research examines mentor and protégé relationships. | Solomon, Loeffler & Frank (Reference Solomon, Loeffler and Frank1953) |

| Social comparison | People engage in social comparisons with one another. | Festinger (Reference Festinger1953) |

| Social exchange | People exchange punishments and rewards in their social interactions | Homans (Reference Homans1958) |

| Management by objectives | Subordinates and superiors jointly set performance expectations. | Drucker (Reference Drucker1954) |

| Emergent leadership | Leaders can “emerge” from a leaderless group. | Hollander (Reference Hollander1961) |

| Mutual leadership | Leadership can come from peers. | Bowers & Seashore (Reference Bowers and Seashore1966) |

| Expectation states theory | Team members develop models of status differential between various team members. | Berger, Cohen & Zelditch (Reference Berger, Cohen and Zelditch1972) |

| Participative decision making | Under certain circumstances, it is advisable to elicit more involvement by subordinates in the decision-making process. | Vroom & Yetton (Reference Vroom and Yetton1973) |

| Vertical dyad linkage | Examines the process between leaders and followers and the creation of in-groups and out-groups. | Graen (Reference Graen and Dunnette1976) |

| Substitutes for leadership | Situation characteristics (e.g., highly routinized work) diminish the need for leadership. | Kerr & Jermier (Reference Kerr and Jermier1978) |

| Leader member exchange | Examines the quality of exchanges between leaders and followers | Liden & Graen (Reference Liden and Graen1979) |

| Self-management | Given certain tools, employees, in general, can manage themselves. | Manz & Sims (Reference Manz and Sims1980) |

| Self-leadership | Employees, given certain conditions, are capable of leading themselves. | Manz (Reference Manz1986) |

| Participative goal setting | Examines how to set goals in participation with subordinates | Erez & Arad (Reference Erez and Arad1986) |

| Self-managing work teams | Team members can take on roles that were formerly reserved for managers. | Manz & Sims (Reference Manz and Sims1987) |

| Followership | Examines the characteristics of good followers. | Kelly (Reference Kelly1988) |

| Empowerment | Examines power sharing with subordinates. | Conger & Kanungo (Reference Conger and Kanungo1988) |

| Team member exchange | Examines how team members engage in social exchanges. | Seers (Reference Seers1989) |

| Shared cognition | Examines the extent to which team members share similar mental models about key internal and external environmental issues. | Klimoski & Mohammed (Reference Klimoski and Mohammed1994); Cannon-Bowers, Salas & Converse (Reference Cannon-Bowers, Salas, Converse and Castellan1993) |

| Co-leadership – role sharing | Examines how two leaders can share a leadership role. | Heenan & Bennis (Reference Heenan and Bennis1999) |

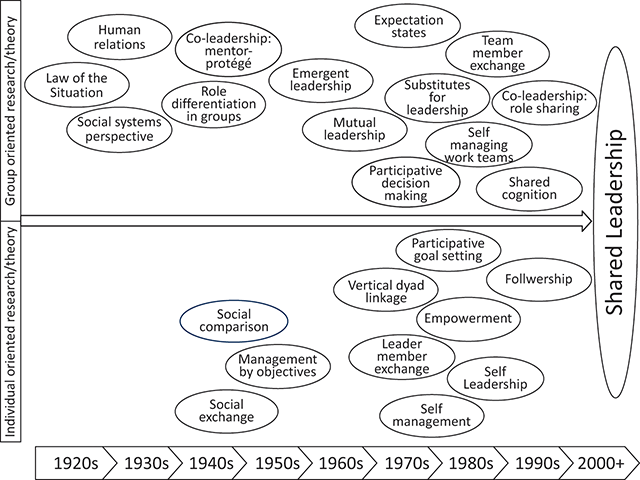

Figure 8 provides a graphic representation of how the twenty-four precursor ideas of shared leadership emerged through the decades. Moreover, the figure parses and categorizes these ideas by group-level issues versus individual-level issues. Ten of these foundational concepts were developed at the individual-level of analysis, while fourteen were generated at the group-level of analysis. In the following paragraphs we briefly review each of these ideas, associating them with their primary proponents.

Figure 8 The shared leadership timeline: Foundations in theory and research.

Leadership Thinking of the Early Twentieth Century Related to Shared Leadership

While several of the most influential authors of the early twentieth century (e.g., Gantt, Reference Gantt1916; Gilbreth, Reference Gilbreth1912; Gilbreth & Gilbreth, Reference Gilbreth and Gilbreth1917; Taylor, Reference Taylor1903, Reference Taylor1911), proponents of scientific management, advocated for and clearly articulated top-down model of leadership, there were pockets of early shared leadership discourse, even if it was not labeled as such. For instance, Mary Parker Follett, a community activist and management consultant, advocated a concept called the law of the situation (Follett, Reference Follett1924). The essence of the law of the situation was that, instead of simply following the dictates of someone in a hierarchical position, people should take direction from the person with the most knowledge about the situation at hand, and that this would vary from situation to situation. At the time of publication, this was a novel idea and was in sharp contrast to the prevailing wisdom of the day when it came to leadership. Her perspective is clearly a forerunner of shared leadership theory.

Even though Follett was popular as both a management consultant and as a speaker in the 1920s, her thinking was largely discounted by the majority of the mainstream business community. One might speculate that the economic uncertainties of the time may have had a role in that regard. For instance, the world was filled with uncertainty with respect to the classic external organizational factors (i.e., political, economic, sociocultural, technological, legal, and environmental (PESTLE) (Aguilar, Reference Aguilar1967), especially during the late 1920s through the mid 1940s, and this may have caused business leaders to loathe the notion of giving up control to others that was inherent in Parker’s writings. With that said, Peter Drucker called her “the brightest star in the management firmament” in her era (Drucker, Reference Drucker1995, p. 2).

Regardless of the global systemic upheaval, in the 1930s, the human relations school (e.g., Bernard, Reference Bernard1938; Mayo, Reference Mayo1933) and social systems perspective (Turner, Reference Turner1933) also both articulated the importance to paying attention to workers and that their psychological needs were imbedded in the social systems of economic activity. As such, these early writers foreshadowed the concept of shared leadership.

Mid Twentieth-Century Developments Related to Shared Leadership

As we move forward to the 1940s and 1950s, we note additional perspectives adding foundational work for the ultimate development of shared leadership theory. For example, Benne and Sheats (Reference Benne and Sheats1948) described the notion of role differentiation in groups, where various members would have a role for influencing group achievement due to their experience and topical knowledge, as just two examples. Solomon, Loeffler, and Frank (Reference Solomon, Loeffler and Frank1953) described the idea of “co-leadership” in mentor-protégé relationships in psychological counseling. They found that even if the therapeutic team were different in seniority in title, neither co-leader would be placed in a differing level of authority or dominance, while in the therapeutic group meeting setting and, in fact, they would behave as supportive partners who shared responsibility for a common goal.

Further, two theories elaborated on key social interactions: social comparison theory was articulated by Festinger (Reference Festinger1953), where group members include ability evaluation in their assessment of others, and secondly, where the stability of that evaluative process is predicated on the similarities or divergences from the others’ abilities, often compared to their own as ‘prototypes’, and social exchange theory as explained by Homans (Reference Homans1958) as the interaction that occurs when influence is gained from others by the act of accepting the other’s influence in return. Finally, Drucker (Reference Drucker1954) forwarded the concept of management by objectives, which described both the allowance and innate desirability for individuality in goal setting but also highlights how those individual goals exist in an interdependent organizational system – reinforcing the notion that organizations are essentially systemic communities of interdisciplinary actors reliant upon one another for success, rather than independent cogs or constituents. Each of these ideas from the 1940s and 1950s added additional intellectual components for the construction of shared leadership theory.

Building on this previous work, scholars in the 1960s provided additional insights closely aligned with shared leadership theory. For instance, Hollander (Reference Hollander1961) observed and wrote about the idea of leader emergence from leaderless groups, while Bowers and Seashore (Reference Bowers and Seashore1966) observed what they called mutual leadership, where the support for a group’s needs could be offered by the formal leader or members for each other, or both. These two concepts are core intellectual contributions to the ultimate development of shared leadership theory.

Late Twentieth-Century Thinking Related to Shared Leadership

In the 1970s we witnessed an accelerated pace of scientific discoveries related to shared leadership. For instance, Berger, Cohen and Zelditch (Reference Berger, Cohen and Zelditch1972) postulated expectation states theory, that is, how individual expectation-states are formed and determine interactive behavior between members of a group. Group members form different evaluations of status, expectations of status, and, overall, generally different expectations based on the assessment of status characteristics. Vroom and Yetton (Reference Vroom and Yetton1973) articulated the idea of participative decision making, and Graen (Reference Graen and Dunnette1976) described the concept of vertical dyad linkage, which built on previous ideas about social exchange mechanisms. A bit later in the decade, Kerr and Jermier (Reference Kerr and Jermier1978) forwarded the notion of substitutes for leadership and Liden and Graen (Reference Liden and Graen1979) articulated the importance of leader-member exchange – that is, leaders will form relationships that differ with each of their followers/subordinates based on various factors, including leadership styles and subordinate roles. All of these concepts provide additional explicative foundations for shared leadership theory.

In the 1980s and 1990s we witnessed several additional developments regarding concepts related to shared leadership. For instance, Manz and Sims (Reference Manz and Sims1980) forwarded the notion of self-management, where group members managed their own behaviors by self-administering consequences for their performance, which Manz subsequently developed into the concept of self-leadership (Manz, Reference Manz1986). Self-leadership expanded the previous work on self-management in that it explored the role of intentional self-influence (self-leading) on personal growth, motivation, and performance. Relatedly, Erez and Arad (Reference Erez and Arad1986) described the process of participative goal setting, where they found that cognitive, social, and motivational participation factors were useful in facilitating positive group and organizational outcomes. Finally, Manz and Sims (Reference Manz and Sims1987) investigated self-managing work teams and the seemingly paradoxical nature of a leader’s role in such a team, and the behaviors that are useful to cultivate in facilitating a team where the leader becomes nominally superfluous yet still present.

Following in these footsteps, Kelly (Reference Kelly1988) articulated the concept of followership, mainly in answer to the almost universal focus on the leader. He noted that if followers were considered, it was usually still simply to bring more clarity to the role of “leader,” yet to exclude them as a discrete component of the relationship was to paint an incomplete picture of both, as neither exists without each other. Conger and Kanungo (Reference Conger and Kanungo1988) forwarded a model of the empowerment process that integrated the diverse viewpoints of the field from both the management and psychology literatures and Seers (Reference Seers1989) provided a perspective on team member exchange relationships that provided a complementary clarity of the role that quality team member exchange relationships played intra-team, thus rounding out the network relationships that were initially explored in the earlier leader-member exchange research.

Finally, the idea of shared cognition, also known as shared mental models, as illuminated by Cannon-Bowers, Salas and Converse (Reference Cannon-Bowers, Salas, Converse and Castellan1993) as well as Klimoski and Mohammed (Reference Klimoski and Mohammed1994) are useful in understanding more of how teams make decisions, particularly with respect to how consequences are defined in the context of the team. Klimoski and Mohammed (Reference Klimoski and Mohammed1994) note that while Durkheim (Reference Durkheim1895/1938) also made mention of the idea “group mind,” it was more to imply a general sense of unified collectiveness. However, the early interest in understanding this notion of individual group member’s various expectations, thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions as a summative group-level phenomenon had fallen away until the later twentieth century when there was again critical interest in more purposeful exploration of the value not just in the top-down leader’s vision-making process, but the notion of shared thought as organizationally beneficial. Slightly later, Heenan and Bennis (Reference Heenan and Bennis1999) described an alternative type of co-leadership that involved truly equal role sharing between two leaders, what they called vertically contiguous leaders who shared the leadership responsibilities of their respective positions. They elaborated further by highlighting that the truly “shrewd leaders of the future are those who recognize the significance of creating alliances with others whose fates are correlated with their own” (Heenan & Bennis, Reference Heenan and Bennis1999: viii).

Summary of Twentieth-Century Intellectual Foundations of Shared Leadership

We have very briefly discussed some of the most important historical underpinnings to the development of shared leadership theory – from the Industrial Revolution, which began in Great Britain, but which quickly spread to the rest of the globe, to the pioneers in the area of scientific management, to several interesting and valuable streams of research that allow us more clarity for understanding the development of shared leadership theory.

While two of these earlier publications (Follett, Reference Follett1924; Bowers & Seashore, Reference Bowers and Seashore1966) might best be described as one-hit-wonders, which were squarely in line with shared leadership, they quickly faded from the scientific discourse. Clearly, the scientific community did not embrace these ideas at the time but they, nonetheless, provided important intellectual stakes in the ground for our current understanding of shared leadership theory. What is clear is that each of these scientific traditions provide intellectual ingredients for the galvanization of shared leadership theory, and again, reinforce that shared leadership theory exists in a meta theoretical plateau, in that it is woven from both supportive and contextual social experiences that when drawn together create an environment where shared leadership can exist.

It is always important to look back in time, to understand how we have arrived at our current location. The historical backdrop of shared leadership theory is rich and complex and up until quite recently, fragmented within other human social experience without much theoretical clarity. With that said, it is now uniformly understood that shared leadership is a critical frame through which to conceptualize leadership dynamics. To wit, in Section 1 we provided an overview graph documenting the rising interest in shared leadership, particularly from the early 2000s. From humble beginnings in the 1990s (Pearce, Reference Pearce1993, Reference Pearce1995, Reference Pearce1997) and two key publications (Pearce & Sims, Reference Pearce and Sims2002; Pearce & Conger, Reference Pearce and Conger2003) in the early 2000s, we now witness an exponential growth in the number of publications on shared leadership, both empirical and conceptual in nature, across many disciplines (e.g., organizational psychology, management and sociology, political science, etc.) and industry sectors (e.g., healthcare, education, public administration, engineering, construction, etc.). Since 2000, at least 1,225 research-focused publications have appeared on shared leadership, with many more in the popular literature, and the number and type of work in this area is not only accelerating in actual numbers but also in the sophistication of analysis. In the next two sections, we delve much more deeply into the research findings surrounding shared leadership.

3 Antecedents of Shared Leadership

Twenty years ago most of the literature regarding the antecedents of shared leadership was conceptual in nature (e.g., Burke, Fiore, & Salas, Reference Burke, Fiore, Salas, Pearce and Conger2003; Ensley, Pearson, & Pearce, Reference Pearce and Jay2003; Houghton, Neck, & Manz, Reference Houghton, Neck, Manz, Pearce and Conger2003; Mayo, Meindl, & Pastor, Reference Mayo, Meindl, Pastor, Pearce and Conger2003; Pearce, Reference Pearce1993, Reference Pearce1995, Reference Pearce and Ensley2004; Pearce & Conger, Reference Pearce and Conger2003; Pearce & Sims, Reference Pearce, Sims, Beyerlein, Johnson and Beyerlein2000). Nonetheless, more recently there have been significant empirical advances in the study of factors that support the formation of shared leadership.

While antecedents of phenomena are critical to a scientific understanding, researchers typically examine outcomes more frequently than antecedents, and shared leadership is no exception. Thus, the predominance of empirical studies of shared leadership has focused on understanding the outcomes. With that said, some researchers have been focusing efforts on developing a richer and deeper understanding of the precursors of shared leadership in teams and organizations. In this vein, empirical research addressing the antecedents of shared leadership has primarily examined four fundamental types of antecedents: (1) vertical leadership, (2) organizational support systems and structures, (3) cultural context, and (4) team factors. Table 2 summarizes this research.

Table 2 Summary of current state of antecedent research on shared leadership

| Vertical Leadership | Leader support/enabling resources/trust/transformational/transparency/vision/ empowering/humility/shared decision-making/servant leadership/engagement/ coaching/goal alignment/expectations of excellence/matching skills/creating focus/ feedback/freedom/safety/values alignment/responsibility/diversity orientation/ fairness/gender |

| Organizational Support Systems | Technology that supports collaboration/communication/institutional empowerment/selection/compensation/education, training and development/shared events/planned responsibility distribution/equity/shared cues/coaching |

| Cultural Context | Organizational cultural/group values/cultural structures/participative safety/voice/social support/purpose/intentional social structures/entrepreneurial support/proactivity/open feedback/autonomy/feedback/job characteristics/perceptions of empowerment/empowerment culture |

| Team Factors | Group member behaviors/complementary expertise/cohesive support/collective achievement/transactional knowledge/knowledge sharing/beliefs about competency and ability/task interdependence/goal interdependence/team connectedness/informal communication opportunities/extraversion/empathy/core self evaluations (CSE)/homogeneity/collective identification/team rewards/member integrity/voice/perceived virtuality/task reflexivity/expectations of creativity/work complexity |

We do not purport that these categories represent a typology of potential antecedents of shared leadership but rather that they provide a useful organizing mechanism for reporting the results that have been found to date. Accordingly, we review each of these categories, in turn, in the following paragraphs, after that we subsequently discuss several research advances regarding antecedents of shared leadership which do not fall neatly into these categories.

Vertical Leadership

Much of the theoretical writing about antecedents of shared leadership has focused on the role of vertical leadership. This seems quite logical for two reasons: first, because the traditional focus in leadership research has been on the formal leaders, but second, and more importantly, the formal leader would appear to be critical component of shared leadership emergence in a group or team. As such, it is not surprising that a great deal of the empirical work on antecedents of shared leadership has focused on this issue. For example, (Hoch, Reference Hoch2013; Hess, Reference Hess2015) found vertical leader support (e.g., commitment to the team, continuous reinforcement of involvement and of team autonomy, and commitment to enabling resources) to be linked to shared leadership development. Moreover, George, Burke, Rodgers, Duthie, Hoffmann, Koceja et al. (Reference George, Burke and Rodgers2002), Klasmeier and Rowold (Reference Klasmeier and Rowold2020), and Olson-Sanders (Reference Olson-Sanders2006) identified trust in the vertical leader to be directly associated with shared leadership development.

More recently, in the context of police work, Masal (Reference Masal2015) found transformational leadership from above to be a predictor of shared leadership. Transformational leadership has been evaluated by others as well (e.g., Hoch, Reference Hoch2013; Klasmeier & Rowold, Reference Klasmeier and Rowold2020; Tung & Shih, Reference Tung and Shih2023; Von Stieglitz, Reference Von Stieglitz2023), with similar results.

Shamir and Lapidot (Reference Shamir, Lapidot, Pearce and Conger2003), in a study of the Israeli Defense Forces, concluded that goal alignment between leaders and followers, as well as follower trust in and satisfaction with vertical leaders, was associated with the development of shared leadership. Abson and Schofield (Reference Abson and Schofield2022) found that a leader’s transparency, and the development of a shared vision, was also integral for shared leadership to emerge in teams where knowledge work and high pressure was also present. This same research team, and others, have found that leaders who engage in empowering leadership behaviors will have followers who report more shared leadership (e.g., Carson, et al., Reference Carson, Tesluk and Marrone2007; Fausing, Joensson, Lewandowski, & Bligh, Reference Fausing, Joensson, Lewandowski and Bligh2015, Grille, Schulte, and Kauffeld, Reference Grille, Schulte and Kauffeld2015; Hoch, Reference Hoch2013; Lyndon, & Pandey, Reference Lyndon and Pandey2020; Margolis & Ziegert, Reference Margolis and Ziegert2016; Svensson, Jones, & Kang, Reference Svensson, Jones and Kang2021; Wassenaar, Reference Wassenaar2017).

In a similar vein, Elloy (Reference Elloy2008) concluded vertical leader engagement with team members in decision-making facilitates the development of shared leadership, while more recently, several studies (e.g., Chiu, Reference Chiu2014; Chiu, Owens, & Tesluk, Reference Chiu, Owens and Tesluk2016; Svensson, et al., Reference Svensson, Jones and Kang2021) found that the humility demonstrated by the vertical leader to be a precursor of shared leadership, where humility promoted both leadership-claiming as well as leadership-granting behaviors from team members. Wang, Jiang, Liu, and Ma, (Reference Wang, Jiang, Liu and Ma2017) and Svensson, et al., (Reference Svensson, Jones and Kang2021) also found that servant leadership behaviors demonstrated by the leader led to more shared leadership in the sports teams that were the target respondents in their study, especially in development environments – that is, environments where the amount of resources are scant.

Hooker and Csikszentmihalyi (Reference Hooker, Csikszentmihalyi, Pearce and Conger2003), in a qualitative study of research and development laboratories, found six vertical leader behaviors to provide the conditions for the development of shared leadership: (1) valuing excellence, (2) providing clear goals, (3) giving timely feedback, (4) matching challenges and skills, (5) diminishing distractions, and (6) creating freedom. Echoing some of these findings, Wood (Reference Wood2005) and Margolis and Ziegert (Reference Margolis and Ziegert2016) found that leaders who enabled more group safety through lower levels of abusive supervision enable groups to experience more shared leadership. Similarly, in a series of qualitative studies, Pearce et al. (Reference Pearce, Manz and Sims2014) found vertical leader engagement in empowering behavior, visionary behavior, as well as providing a focus on values to be associated with the development of shared leadership. Wassenaar (Reference Wassenaar2017) found that a leader’s diversity orientation and the perception of their fairness toward members of the team also resulted in higher levels of shared leadership.

While not directly associated with the formal leader of the team, Carson et al. (Reference Carson, Tesluk and Marrone2007) noted that supportive coaching from external leaders – leaders who are not in any sort of supervisorial role of the team members – was useful in developing more shared leadership. Grille et al. (Reference Grille, Schulte and Kauffeld2015) note that team member’s perception of how fairly they are rewarded by the leader, is also associated with shared leadership. Finally, in a study of several major Finnish healthcare organizations, Konu and Viitanen (Reference Konu and Viitanen2008) found that female vertical leaders are more likely to develop shared leadership than their male counterparts. In sum, these aforementioned studies identify a critical role of vertical leadership in the shared leadership equation.

Organizational Support Systems and Structures

A second major category of antecedents that have been linked to shared leadership are those that focus on support structures and systems within organizations. For example, information technology systems that facilitate collaboration continues to evolve in sophistication and scope, and where well used in organizations to develop communication and information exchange mechanisms for group work, has also been identified as a facilitator of shared leadership. To support this notion, Wassenaar, Pearce, Hoch, and Wegge (Reference Wassenaar, Pearce, Hoch, Wegge and Yoong2010) found information technology support systems, in a qualitative study of German virtual teams, to facilitate the development of shared leadership. Similarly, Cordery, Soo, Kirkman, Rosen, and Mathieu (Reference Cordery, Soo, Kirkman, Rosen and Mathieu2009), in a study of parallel virtual global teams, found technological support structures, which focused on enabling team members to communicate more easily, and which facilitated the transfer of learning across team members, generated greater development of shared leadership across such teams.

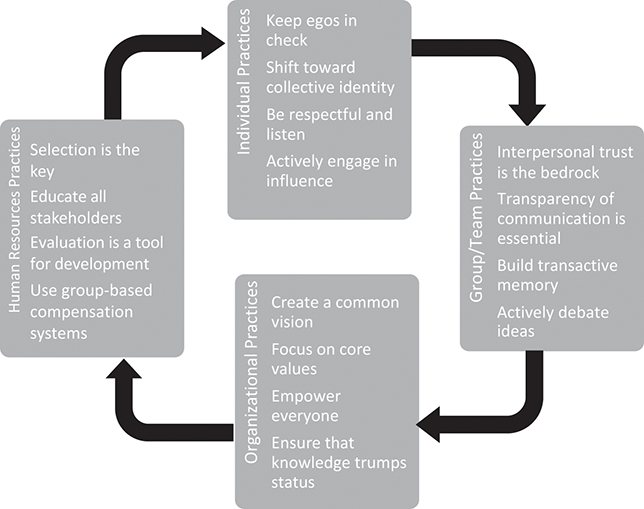

Beyond technology, Pearce et al. (Reference Pearce, Manz and Sims2014), in a compilation of qualitative studies, found that three key internal systems: selection; compensation; and education, training, and development systems were integral in providing a platform that enabled a shared leadership environment to evolve. The support of the organization for creating shared events, such as professional development opportunities or town hall meetings, as just two examples, are also useful platforms (Kang & Svensson, Reference Kang and Svensson2023). In that same study, Kang and Svensson (Reference Kang and Svensson2023) also evaluated how strategic planning, in this case conceptualized as the strategic decision to distribute various leader functions collaboratively, resulted in reports of more shared leadership. Similarly, Hess (Reference Hess2015) found that focus on equity in team member recruitment and focus on team outcomes facilitated the development of shared leadership. Moreover, Elloy (Reference Elloy2008), in a paper mill study, found team training, focused on collaborative communication, to be linked to the development of shared leadership. From a different perspective, DeRue, Nahrgang, and Ashford (Reference DeRue, Nahrgang and Ashford2015) found perceptions of warmth (characterized by: benevolence, trustworthiness, and liking), and a shared understanding of network cues to be linked to the development of shared leadership.

A related line of inquiry that has gained traction in the literature is focused on the role of coaching (e.g., Bono, Purvanova, Towler, & Peterson, Reference Bono, Purvanova, Towler and Peterson2009; Leonard & Goff, Reference Leonard and Goff2003). In this regard, Carson et al. (Reference Carson, Tesluk and Marrone2007), as well as Cordery et al. (Reference Cordery, Soo, Kirkman, Rosen and Mathieu2009), both found various forms of coaching to be positively linked to the demonstration and development of shared leadership. In total, organizational support systems and structures appear to be a critical ingredient when it comes to the development of shared leadership.

Cultural Context

While vertical leadership from above, as well as organizational support systems and structures have been linked to shared leadership development, another broad category of antecedents to shared leadership entails cultural context. Cultural context includes factors as broad as national and organizational culture, to shared team member values. Konu and Viitanen (Reference Konu and Viitanen2008), for example, identified team values as an important predictor of the development of shared leadership. Similarly, Carson et al. (Reference Carson, Tesluk and Marrone2007), as well as Serban and Roberts (Reference Serban and Roberts2016) and Wu, Cormican, and Chen (Reference Wu, Cormican and Chen2020), as well as Carvalho, Sobral, and Mansur (Reference Carvalho, Sobral and Mansur2020), found what they labeled internal environments of groups, where there were higher levels of participative safety present, to be linked to the development of shared leadership (e.g., where environments that support shared voice, social support, and purpose). They found that this is where the internal culture of the team is intentionally set up to enable members to offer others leadership influence.

In a study conducted in innovation labs, Rose, Groeger, and Hölzle (Reference Rose, Groeger and Hölzle2021) learned that cultivating a culture of shared voice, room for experimentation, and organized opportunities for entrepreneurial thinking resulted in shared leadership emergence in creative environments. Another consideration was uncovered by the team of Coun, Gelderman, and Perez-Arendsen (Reference Coun, Gelderman and Perez-Arendsen2015), where they were able to compare two different groups of people, both who experienced a New Ways of Working (NWW, facilitated by new and high levels of information communications technology) rollout in the organization, but where one group also had an articulated emphasis placed on support structures for proactivity. The assumption was that the NWW (characterized by an open feedback culture, more autonomy and internally supported entrepreneurship) would facilitate shared leadership emergence in both groups, but this was not the case, as the group that did have the proactivity support did report shared leadership, while the other group did not.

Wood (Reference Wood2005), in a study of church leadership, found that perceptions of empowerment by teams and their members were predictive of shared leadership behavior. Similarly, institutional empowerment has been linked to shared leadership (Mi et al., 2023). Finally, Pearce et al. (Reference Pearce, Manz and Sims2014), across a number of qualitative studies, found organizational culture to be an important antecedent of shared leadership. Taken together, these studies point to an important role for cultural context as an important precursor of shared leadership.

Team Factors as Antecedents

Up until recently, the study related to antecedents included only the role that the vertical/formal leader played, organizational structures that help or harm, or cultural context factors in shared leadership emergence. However, there are now enough studies that have been done that a fourth category is needed – one that considers team factors separately. For example, Xu and Zhao (Reference Xu and Zhao2023), in a mixed methods study, found that the macro level shared leadership phenomenon was enabled through individual team member behaviors (in their model they observed three dimensions: collective achievement leadership, cohesive support leadership, and complementary expertise leadership).

Transactional knowledge and knowledge sharing within and between team members have also emerged as important antecedents, as has been found in various studies (e.g., Abson, & Schofield, Reference Abson and Schofield2022; Fransen et al., Reference Fransen, Delvaux, Mesquita and Van Puyenbroeck2018; Vandavasi et al., Reference Vandavasi, McConville, Uen and Yepuru2020). Fransen et al. (Reference Fransen, Delvaux, Mesquita and Van Puyenbroeck2018) also found that, in addition to their work on team transactional knowledge, the team members’ beliefs about each other’s competency, the perception of the other’s ability to complete a task well, was an important factor for shared leadership. Similarly, Lyndon, Pandey, and Navare, (Reference Lyndon, Pandey and Navare2022) found transactive memory systems to be positively related to shared leadership.

Another set of team-based antecedents are those related to the tasks that are expected from the team. Task interdependence, where team members are expected to rely on others’ skills, interact with, and also depend on others to accomplish a goal (Guzzo & Shea, 1992), was found to be an antecedent of shared leadership in several studies (e.g., Fausing et al., Reference Fausing, Joensson, Lewandowski and Bligh2015; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cormican and Chen2020; Wu, Zhou, & Cormican, Reference Wu, Zhou and Cormican2023). Fausing et al. (Reference Fausing, Joensson, Lewandowski and Bligh2015) note that they base their empirical work on Pearce and Sims’ (Reference Pearce, Sims, Beyerlein, Johnson and Beyerlein2000) theoretical framework which highlighted the mutual cooperation, interaction, and guidance that is part of the shared leadership influence process, and also note that in contexts where interdependence is low, employees are also able to complete their work with less interaction with one another. This bears out the notion put forward by Wassenaar and Pearce (Reference Wassenaar, Pearce, Day and Antonakis2012, p. 382) that “shared leadership is applicable only to tasks where there is interdependency between the individuals involved.” Fausing et al. (Reference Fausing, Joensson, Lewandowski and Bligh2015) also found that goal interdependence, where the goals are specifically related to the work that is completed by the team itself and the members can see how their work fits into the completion of the whole, was a significant antecedent for shared leadership. Along this same vein, Hans and Gupta (Reference Hans and Gupta2018) noted that the job characteristics of skill variety, task significance, autonomy, and feedback are significantly supportive of shared leadership, thus suggesting the notion that job design is a critical component for shared leadership.

Van Zyl (Reference Van Zyl2020) found that team connectedness was a clear antecedent for shared leadership emergence in dispersed team members, but also notes that the type of interactions that generated the highest level of connectedness between these dispersed team members were informal connections made through shared interactions outside of formally organized settings. Building further on the type of team member interactions that are useful for shared leadership development, Ge et al. (Reference Ge, Liu and Zhang2024) found that team-based relationship- and task-oriented personality compositions positively impact reported shared leadership when mediated by team member exchange (TMX). Further, Abson and Schofield (Reference Abson and Schofield2022) note that empathy between the members in a team enhances the willingness for people to share influence among each other.

Team core self-evaluations (CSE) can also influence both the emergence and effectiveness (outcomes) of shared leadership (Siangchokyoo & Klinger, Reference Siangchokyoo and Klinger2022). As an example, they note that the amount of homogeneity and team collective identification in team members CSE influence the decisions of team members to share leadership. Building on the notion of collective identification within teams, Gu, Hu, and Hempel (Reference Gu, Hu and Hempel2022) found that the interdependence of team rewards and incentives positively supported more shared leadership in teams.

In an interesting study of both antecedents and outcomes of shared leadership, Hoch (Reference Hoch2013) found that team member integrity was positively associated with shared leadership. Finally, Rose et al., Reference Rose, Groeger and Hölzle2021 noted that voice, where team members feel enabled “to speak up and get involved” (Carson et al., Reference Carson, Tesluk and Marrone2007, p. 1223), was positively related to how much shared leadership was reported in the respondents studied. This bears out the earlier findings from Carson et al. (Reference Carson, Tesluk and Marrone2007), making voice an interesting factor to continue to study as part of shared leadership emergence. Darban (Reference Darban2022), in a university study with 341 students in 48 virtual teams, found that team empowerment and perceived virtuality were positively associated with shared leadership, in turn increasing the team members intention to learn, and to update their knowledge about a topic.

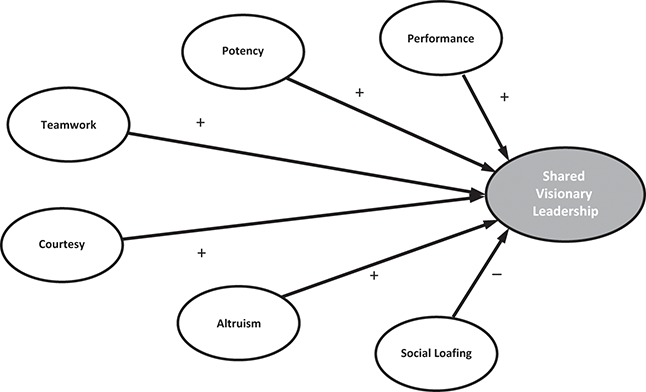

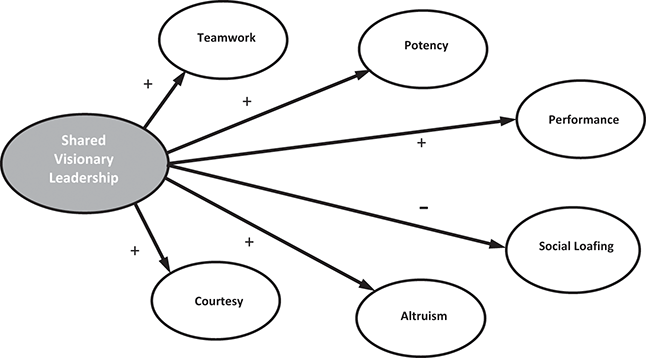

Rose et al. (Reference Rose, Groeger and Hölzle2021) note that the amount of shared leadership is also positively related to the team’s expected creativity of the work output as well as the task reflexivity – how much the team members reflect on the goals and so on that are expected of them and feel willing and enabled to adapt them to current or expected circumstances (West, Reference West1996). This idea particularly built on the theoretical work of Pearce (Reference Pearce2004), where it was noted that where tasks were highly interdependent, complex, and requiring creativity, shared leadership would also be more likely to be present and useful. Finally, Pearce and Ensley (Reference Pearce and Ensley2004), in a study of product and process improvement teams, provided a fairly comprehensive analysis of antecedents of shared leadership. They identified prior team performance, team potency, teamwork, courtesy, and altruism as positive predictors of shared leadership, as well as social loafing as a negative predictor of shared leadership. Figure 9 provides a graphic view of this study.

Figure 9 Antecedents of shared leadership in product and process improvement teams

Other Antecedents of Shared Leadership

Additional studies have examined factors that do not fall neatly into one of the above categories but have been linked to the development and display of shared leadership. Ropo and Sauer (Reference Ropo and Sauer2003), in a longitudinal study of orchestras, identified length of relationships between various members as an antecedent to shared leadership between orchestral constituents. Relatedly, Fransen et al., (Reference Fransen, Delvaux, Mesquita and Van Puyenbroeck2018) found that the amount of warmth-oriented traits (e.g., trustworthiness, helpfulness, and friendliness) that were exhibited by a team member are positively predictive of the amount of influence that team member would have in the group environment. Kang and Svensson (Reference Kang and Svensson2023) noted that the personality traits of extraversion and introversion are important to the development of shared leadership, in that extraverts are more likely to share easily, and introverts can be more intentionally supported by the leaders and other team members.

From a different tack, Chiu (Reference Chiu2014) found proactivity of team members to facilitate the development of shared leadership. Similarly, Pearce et al. (Reference Pearce, Manz and Sims2014) found proactivity, trust, and openness to be related to the development of shared leadership, across a number of qualitative studies, while Hooker and Csikszentmihalyi (Reference Hooker, Csikszentmihalyi, Pearce and Conger2003), in their study of research and development laboratories, identified the state of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990) as a foundational link in the development of shared leadership. Moreover, Paunova and Lee (Reference Paunova, Lee, Osland, Li and Mendenhall2016) found team learning orientation to be related to the development of shared leadership.

Muethel, Gehrlein, and Hoegl (Reference Muethel, Gehrlein and Hoegl2012), on the other hand, found demographic characteristics of groups affect the development of shared leadership. Kukenberger and I’Innocenzo (Reference Kukenberger and D’Innocenzo2020) note that certain types of diversity, such as gender diversity, will initially negatively impact the development of shared leadership, particularly in climates where cooperation is low, or the team is newly formed. However, as time passes, the impact of gender diversity will be mitigated, particularly in teams where task-related experiences are high. They also found that shared leadership was more present in teams who reported functional diversity and high levels of a cooperative climate. Serban and Roberts (Reference Serban and Roberts2016) identified task cohesion as well as task ambiguity as factors related to shared leadership development. Finally, Hess (Reference Hess2015) found face-to-face teams to be more inclined to demonstrate and develop shared leadership than their virtual team counterparts. Together, these studies demonstrate a range of additional factors associated with the development of shared leadership.

Summary of the Empirical Examination of Antecedents of Shared Leadership

While there has lately been an increase in the number of studies (both qualitative and quantitative) on the antecedents of shared leadership, there are still far fewer relative to research on the outcomes of shared leadership. Nonetheless, given the clear value of shared leadership in many settings, there is a great deal of opportunity for more development in this area. Given this, we will specify some further possibilities for research on antecedents of shared leadership in Section 5. In the next section, however, we detail the work that has been done regarding the outcomes of shared leadership.

4 Outcomes of Shared Leadership

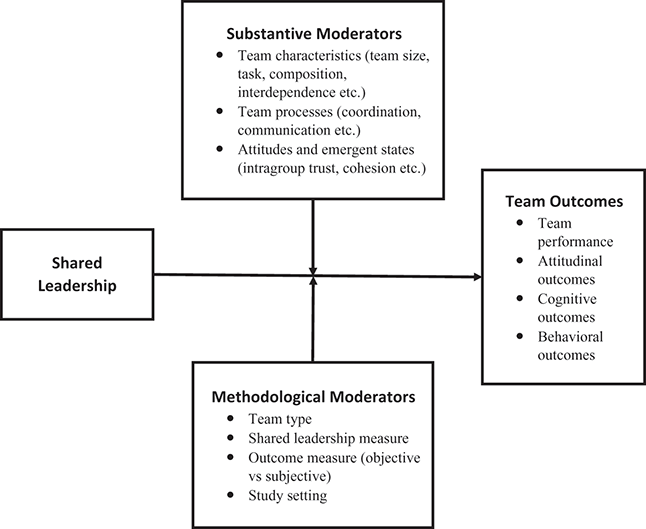

Much of the early work on the outcomes of shared leadership was conceptual in nature (e.g., Burke, Fiore, & Salas, Reference Burke, Fiore, Salas, Pearce and Conger2003; Ensley, Pearson, & Pearce, Reference Pearce and Jay2003; Mayo, Meindl, & Pastor, Reference Mayo, Meindl, Pastor, Pearce and Conger2003; Pearce, Reference Pearce1993, Reference Pearce1995; Pearce & Sims, Reference Pearce, Sims, Beyerlein, Johnson and Beyerlein2000; Seibert, Sparrowe, & Liden, Reference Seibert, Sparrowe, Liden, Pearce and Conger2003) with emphasis placed on defining the concept of shared leadership and its role in the larger organizational literature. Over the last two decades, in addition to many qualitative investigations, the study of shared leadership has produced an increasingly wide and thoughtful body of quantitative studies that examine the relationship between shared leadership and a variety of outcomes. In fact, the proliferation of empirical research has allowed for the publication of no less than four different meta-analyses linking shared leadership to several important outcomes (Nicolaides et al., Reference Nicolaides, LaPort and Chen2014; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Waldman and Zhang2014; D’Innocenzo et al., 2016; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Cormican and Chen2020).

Research in organizational behavior generally references and studies outcomes at three different levels of analysis – individual-, group/team-, and organization-level outcomes, with shared leadership being no exception. Outcomes in organizational behavior and general management research include such things as cognition, attitudes, behavior, and performance. Some examples, at the individual-level of analysis, include individual job performance, job satisfaction, motivation, and well-being. Some examples of outcomes traditionally examined at the group/team level include group/team performance, collaboration and communication, coordination, team satisfaction, trust and cohesion, and similar concepts. Finally, some examples of organizational-level outcomes include such things as organizational financial performance, organizational culture and climate, customer service and satisfaction, and organizational turnover rate, to name a few.

By definition, shared leadership describes and refers to a group/team-level phenomenon; consequently, the majority of the empirical studies focus on group/team-level outcomes, although individual- and organizational-level outcomes have also been examined. Consequently, in the remainder of this section, we start with explaining the relationship between shared leadership and group/team outcomes, and then move on to briefly discuss individual and organizational level consequences of shared leadership.

Shared Leadership and Team-Level Outcomes

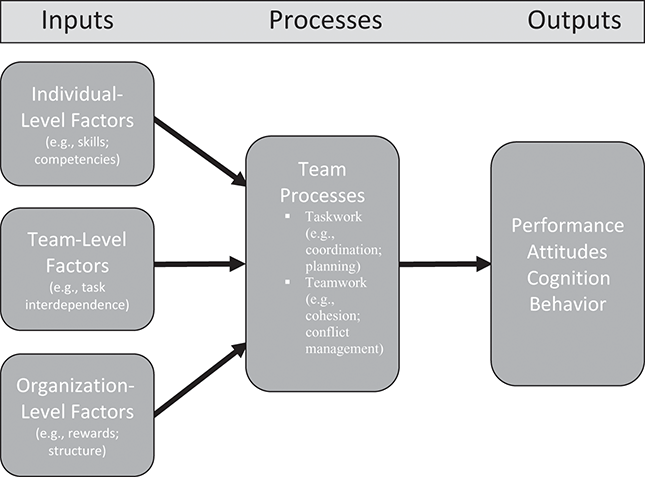

The examination of the team level consequences of shared leadership has been grounded in the general group/teams’ research literature, which suggests that team effectiveness – an umbrella term defined in the section called shared leadership and overall team effectiveness – encompasses four categories: performance, attitudes, cognition, and behaviors (Cohen & Bailey, Reference Cohen and Bailey1997; Cox, Pearce & Perry, Reference Cox, Pearce, Perry, Pearce and Conger2003), with each one of these categories potentially subjected to the influence of shared leadership. Other authors (e.g., Nicolaides et al., Reference Nicolaides, LaPort and Chen2014; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Liao, Yam and Johnson2018; Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Houghton and Manz2023) split the consequences of shared leadership into proximal outcomes (e.g., team affective tone or team efficacy) and distal outcomes (e.g., team performance or team creativity), arguing that proximal outcomes transfer the influence shared leadership to, and, in turn, relate to distal outcomes. Both systematizations of the outcomes, however, may be traced back to the input-process-output model of team effectiveness (IPO), which we explain briefly in the next paragraph before we outline the specifics of the shared leadership outcomes.

Shared Leadership and Overall Team Effectiveness

As an umbrella term, team effectiveness encompasses performance as well as other team-level outcomes. Extant team effectiveness research dates to almost sixty years ago when McGrath (Reference McGrath1964) advanced the so-called input-process-output (IPO) model for studying and analyzing the functioning of systems, including teams and organizations. This conceptual model breaks down a system into three main components – Inputs, Processes, and Outputs – and is often applied to the study and assessment of team effectiveness. Figure 10 contains a team context version of this model.

Figure 10 Input-process-output model of team effectiveness

As represented by the figure and as noted by Mathieu and colleagues, in the IPO model “Inputs describe antecedent factors that enable and constrain members’ interactions” (2008, p. 412). Inputs may be individual, such as individual team member characteristics (e.g., competence, personality); team, such as team task structure, team composition, or leadership, and contextual and organizational, such as environmental factors (e.g., external environment complexity or organizational factors, such as organizational climate or organizational structure). These inputs serve as antecedents for various processes, which describe members’ interactions directed toward task accomplishment. Historically, team processes have been categorized as “taskwork” – or processes describing functions that team members engage in for team task accomplishment, and “teamwork” – or interactions between team members. In 2001, Marks and colleagues offered a new taxonomy, which discusses transition, action and interpersonal team processes, which have a more temporal nature and refer to planning and coordination activities, task-accomplishment related activities, and the more transient interpersonal processes, which include conflict management, trust building and similar interpersonal processes. Finally, outputs describe the results, outcomes, or products generated by the system, as a result of the processes applied to the inputs. In the context of teams, outputs can include the overall team performance, the achievement of the team’s goals, or timely project completion. Outcomes, however, can also include more attitudinal, cognitive, or behavioral-based aspects such as increased knowledge, team members’ cohesion, team vitality, and similar. In other words, “outcomes are results and by-products of team activity that are valued by one or more constituencies” (Mathieu et al., Reference Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp and Gilson2008). In the literature using the IPO model, leadership (including shared leadership) is usually treated as an antecedent factor (or input), and sometimes as a process, which influences several outputs. As seen from the figure and in the previous paragraphs, team effectiveness comprises both performance and other outcomes, with performance encompassing objective and subjective performance, and other outcomes encompassing team members’ attitudinal (e.g., team members’ overall satisfaction, commitment), cognitive (e.g., mental models) and behavioral outcomes (e.g., cooperation, helping and similar).