Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought numerous challenges globally, including economic recession, unemployment, rising poverty, and widening gender gaps in income and unpaid care work. Prevented by lockdowns and social distancing measures from meeting others, including grandparents, outside of their households, parents became solely responsible for childcare when schools and childcare centres closed (Bernhardt et al., Reference Bernhardt, Recksiedler and Linberg2023). Working mothers specifically encountered additional difficulties in balancing work and family responsibilities arising from increased care demands (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021).

The gendered context is crucial for analysing work–family balance, as women worldwide take more responsibility for unpaid family work (Adisa et al., Reference Adisa, Aiyenitau and Adekoya2021) and are more likely to reduce their working hours than men (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021). This study contributes to the literature highlighting the persistence of gender inequality in work–family balance during the pandemic by comparing policy and perceptions of working mothers in the UK and South Korea (hereafter “Korea”). It also critically analyses work–family balance policies from a gender perspective, highlighting opportunities for policy development to support mothers combining work and care. Drawing on survey data from working mothers in the UK and Korea in July 2020, this study investigates the following research questions: (1) How do gender differences in time spent on unpaid work differ before and during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) How does the amount and change in gendered unpaid labour during the pandemic shape work–family balance?; (3) To what extent do work–family policies support working mothers in balancing work and family? What are the main areas for policy development from a gender perspective?

Various differences between the two countries make them an interesting case through which to compare the gender context in work–family balance during the pandemic. Notably, the gender gap in pay and employment rates is much more apparent in Korea than in the UK (OECD, 2023a; World Economic Forum, 2024). Moreover, traditional gender role attitudes and behaviour are more prevalent in Korea than in the UK (Craig and Van Tienoven, Reference Craig and Van Tienoven2021). Furthermore, while both countries have recently expanded early childhood education and care (ECEC) provision (An, Reference An2018; Deeming, Reference Deeming, Blum, Kuhlmann and Schubert2020), leading to high rates of enrolment (OECD, 2023b), their childcare leave policies have developed differently. In Korea, the focus has been on father-specific leave, while UK policies have focused more on flexible working hours. Moreover, the two countries adopted different strategies to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, with the UK introducing stricter social distancing rules (e.g., lockdown).

A number of studies (Lewis, Reference Lewis2009; Sung, Reference Sung, Sung and Pascall2014; Reference Sung and Sung2025b) have examined work–family balance issues in the UK and Korea. However, few have compared the two in terms of gender differences in unpaid work during the pandemic and its impact on women balancing work and family. Policy comparisons between them are even more scarce, particularly in relation to work–family balance and childcare. Likewise, although work–family balance policies are aligned across the UK, the number of free childcare hours available differs in Northern Ireland (NI), from which the majority of the UK sample is drawn; these differences will be examined. Finally, by examining the impact of COVID-19 on working mothers, this study provides an insight into gender inequality in the division of labour, which affects mothers’ ability to balance work and family, and highlights the need for further policy development to reduce gender gaps in unpaid care work.

The impact of COVID-19 on mothers balancing work and family

The social distancing measures many countries introduced to control the COVID-19 pandemic created significant challenges globally. In the UK, the national lockdown during the first phase of the pandemic (March–June 2020) involved school closures and restrictions on travel and social contact (Shum et al., Reference Shum, Klampe, Pearcey, Cattel, Burgess, Lawrence and Waite2023). By contrast, the Korean government did not impose a full lockdown. Although strict social distancing guidelines were introduced at the start of the pandemic in March 2020, these were relaxed in April and replaced with routine distancing in May (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chin and Sung2020). Nevertheless, the closure of schools and childcare centres had a significant impact on Korean mothers by intensifying the double burden of paid and unpaid work. This burden was even greater for UK mothers as the national lockdown also limited family support.

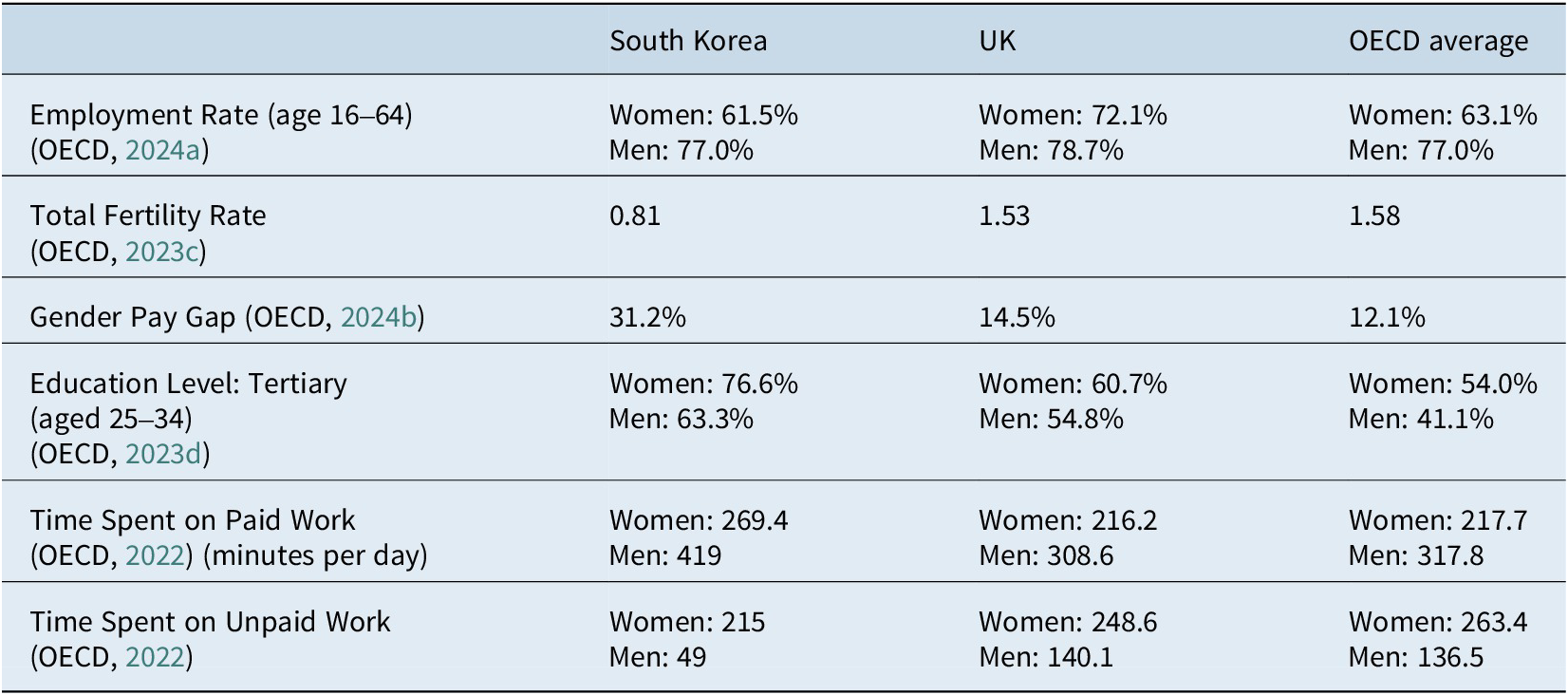

Gender inequalities in employment and time use also differ between the two countries, with Korea showing a larger gender gap in pay and time spent on unpaid work (Table 1). Although women in the UK spend more time on unpaid work overall, Korean women spend four times as many hours on unpaid work compared to Korean men, almost double the gap between men and women in the UK. Moreover, although Korea boasts the highest percentage (76.6%) of women aged 25–34 with a tertiary education among the OECD countries, women’s employment is significantly lower in Korea than in the UK and slightly lower than the OECD average (OECD, 2024a, 2023d). Also, the gender pay gap is highest in Korea and the fertility rate is lowest (OECD, 2023c, 2024b), providing further evidence that gender inequality in Korea is greater than in the UK.

Table 1. The relative position of women and men in the UK and South Korea

Although gender inequalities existed in both countries pre-pandemic, COVID-19 exacerbated these inequalities (Bernhardt et al., Reference Bernhardt, Recksiedler and Linberg2023). Overall, research shows that the pandemic reinforced traditional gendered family roles (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Landivar, Ruppanner and Scarborough2021) and heightened the challenges faced by mothers seeking work–family balance (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chin and Sung2020; Adisa et al., Reference Adisa, Aiyenitau and Adekoya2021). In some studies, women reported that their male partners were more involved in childcare and domestic work during the pandemic, but men were more likely to assist than assume full responsibility, or performed the role poorly (Chung et al., Reference Chung, Lanier and Wong2020). Most studies have highlighted the additional burden that working mothers shouldered during the pandemic as their responsibility for unpaid work intensified (Craig and Van Tienoven, Reference Craig and Van Tienoven2021; Bernhardt et al., Reference Bernhardt, Recksiedler and Linberg2023).

Work–family balance policies in the UK and South Korea from a gender perspective

While some studies highlight the importance of work–family balance policies for working parents (Shum et al., Reference Shum, Klampe, Pearcey, Cattel, Burgess, Lawrence and Waite2023; OECD, 2023a), others show that such policies can have a negative impact due to gendered patterns of policy-use (Thebaud and Pedulla, Reference Thebaud and Pedulla2022). For example, women are more likely than men to avail of such policies and to take longer periods of leave, which can negatively affect career progression (Lewis, Reference Lewis2009) and exacerbate gender gaps in the labour market (Hook et al., Reference Hook, Li, Paek and Cotter2023). Thus, it is crucial to implement gender-egalitarian policies (Author1 and a colleague, Reference Sung and Smyth2022).

The UK ranks second in the world in childcare costs, with families spending 35.7% of their pay on childcare (World Economic Forum, 2019). Studies show that low-income women often reduce working hours and seek informal childcare provision by grandparents to manage work and family responsibilities (Adisa et al., Reference Adisa, Aiyenitau and Adekoya2021). To reduce childcare costs, 30 hour of free childcare are available in Scotland, England, and Wales, while in NI, at least 12.5 hour of “funded pre-school education” are available for 3- and 4-year-olds. Since September 2024, free childcare hours have been extended to eligible working parents of children from 9 months old to school age in England (Gov.UK, 2024a). The increase does not apply to NI, however, making work–family balance more difficult for NI mothers. Also, UK employees have a legal/statutory right to request flexible working, enabling them to change work hours, days, and locations (Gov.UK, 2024b). Shared parental leave has been available since 2014 and parents can share up to 50 weeks, but the pay (£184.03 per week or 90% of your average weekly earnings, whichever is lower) (Gov.UK, 2024c) is too low to encourage use by fathers.

In Korea, work–family balance policies have undergone a significant transformation, in concert with recent socioeconomic and demographic changes. The most notable change was the introduction of father-specific leave – specifically, paternity leave in 2012 and “daddy months” in 2016 – designed to encourage father’s involvement in childcare (Sung, Reference Sung2018). In 2022, as a further financial incentive to fathers, the Korean government introduced 3 + 3 parental leave, through which each parent is eligible to take 3 months of leave and is entitled to ₩7,500,000 (£4776) if they take this leave simultaneously or sequentially for the same child within the 12-month period following the child’s birth (MOEL, 2023). Despite these notable improvements, uptake of parental leave by fathers remains low (6.8%) (Jeong, Reference Jeong2024). Moreover, although the 2013 universal childcare scheme covers formal childcare costs (MOHW, 2024), it does little to ease the burden of childcare on mothers or to promote gender equality due to the lack of public nurseries. Parents who use private nurseries tend to incur additional childcare costs despite the scheme covering tuition fees (Park et al., Reference Park, Kim and Yoon2021). The reduced working hour scheme introduced in 2019 for parents with children (aged 0–8) has similar shortcomings. Designed to provide flexibility, the scheme is not widely implemented (as of 2021, only 32% of employers offered it), and some parents have used it to replace parental leave (Jeong, Reference Jeong2024). This is especially true of those working for small companies, who reported more difficulty requesting longer periods of parental leave.

Recent policy developments have failed to shift the gendered notion of care as women’s work or gendered patterns of policy use in either country. While policies in the UK provide better options for flexible working patterns than Korean policies, father-specific leave is more developed in Korea. Nevertheless, paternity/parental leave remains under the “maternity protection” scheme in Korea, reflecting women’s role as primary carers (Sung, Reference Sung2018). In the UK, further incentives are required to encourage fathers to take up shared parental leave, which should be reserved for fathers’ use. Currently, because it is part of maternity leave, it cannot be transferred to fathers without mothers’ consent and therefore fails to challenge existing gender norms (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2022).

Gender and work–family balance: unpaid work time, care and policy implications

Gender inequality in the division of labour within households has a significant impact on women’s ability to reconcile work and family, as unequal sharing of unpaid work can negatively affect women’s career progression (Hook et al., Reference Hook, Li, Paek and Cotter2023). As traditionally conceived, a father’s primary role is that of financial provider, while mothers are cast as carers (Ladge and Humberd, Reference Ladge, Humberd, Grau, Bowles and Maestro2022). This understanding has been gradually changing, however, due to socio-economic and cultural developments such as women’s increasing participation in the labour market and attitudinal shifts towards more egalitarian conceptions of gender roles (Sung and Smyth, Reference Sung and Smyth2022). Nevertheless, men’s involvement in unpaid work has not significantly improved, with women continuing to take primary responsibility for childcare and housework.

Culture and norms are crucial in shaping gender roles in both the workplace and the home (OECD, 2017) and are closely related to unequal sharing of unpaid family work (Sung, Reference Sung2018). Gender culture – the cultural values and ideals that affect the forms of social integration and gender division of labour in a society (Pauf-Effinger, Reference Pauf-Effinger2004) – is of utmost importance to an understanding of cross-national variations in gender division of labour (Aboim, Reference Aboim2010). The gendered cultural norms and assumptions that impede the greater involvement of men in familial work have significant consequences for most working women (Adisa et al., Reference Adisa, Aiyenitau and Adekoya2021). For example, research has shown that while ‘gender egalitarian care beliefs’ allowed Korean mothers to maintain and pursue their career aspirations during the pandemic, “gendered care beliefs,” such as the assumption that a mother’s role is that of primary carer, weakened those aspirations (Nam and Sennott, Reference Nam and Sennott2023, p. 161). In the UK, women whose attitudes before having children were more traditional are more likely to reduce their working hours after having children, whereas women with less traditional attitudes are less likely to do so (Schober and Scott, Reference Schober and Scott2012). Cultural expectations and demands that amplify the importance of family responsibility – what Bianchi et al. (Reference Bianchi, Robinson and Milke2006), p. 124) call the ‘cultural ideals surrounding motherhood’ – also can lead working mothers to spend more time with their children (Blair-Loy and Cech, Reference Blair-Loy and Cech2017). In this cultural construction of motherhood, not only do mothers have primary responsibility for childcare, but motherhood is a “natural” female trait (Hays, Reference Hays1996, p. 110). While Hay’s (Reference Hays1996) concept of “intensive mothering” has been extended to include fathers under the rubric of “intensive parenting” in Western societies (Wall, Reference Wall2010), in Korea, it has been extended to grandparents, and particularly to grandmothers, whose role in childcare is more prominent than that of fathers (Sung, Reference Sung2025a).

Time, too, is often gendered. As Bryson and Deery (Reference Bryson and Deery2010, p. 91) have observed, ‘time cultures are bound up with power and control’, and gender inequalities are sustained by gender differences in time use. During the pandemic, family obligations and childcare issues were more likely to impinge upon mothers’ working time than fathers’ (Craig and Van Tienoven, Reference Craig and Van Tienoven2021). For instance, Korean women were more likely to leave their jobs due to the difficulties of balancing work and family (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Chin and Sung2020). In the UK, women are more likely than men to manage their caring responsibilities by working part-time (Warren and Lyonette, Reference Warren, Lyonette, Felstead, Gallie and Green2015).

Additionally, workplace culture and a conception of the ideal worker as someone who is always available to meet employer demands tend to permeate the workplace through organisational practice (Correll et al., Reference Correll, Kelly, O’Connor and Williams2014). When employees take leave or work flexibly, they risk being stigmatised as less committed, low-quality workers (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Blair-Loy and Berdahl2013). Because women are more likely to avail of such policies than men, this has significant implications for working mothers (Thebaud and Pedulla, Reference Thebaud and Pedulla2022).

The gender context is also important for which policies and laws are constructed, as this determines the options available to women and men (Hagqvist et al., Reference Hagqvist, Gadin and Nordenmark2017). For example, policies that support work–family balance can have a positive influence on gender equality norms (Pascall and Lewis, Reference Pascall and Lewis2004) and egalitarian policy design can contribute to more egalitarian gender role attitudes and behaviour (Gangl and Ziefel, Reference Gangl and Ziefel2015). The effectiveness of these policies can be impeded, however, by traditional cultural beliefs (Sung, Reference Sung2025a) and dynamics between men and women which, despite the egalitarian culture promoted in many developed countries, can hinder their achievement of work–family balance (Seierstad and Kirton, Reference Seierstad and Kirton2015). Further investigation of the interplay between gender norms/culture, time use, and work–family balance policies is crucial for tackling these obstacles.

Research methods

The data is derived from an online survey conducted in July 2020 on unpaid labour practices among mothers and their partners. To capture how policy and gender norms might shape work–family conflict during the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were limited to women in dual-earner families who were 18 years old or older, partnered with men, and living with minor children. The Korean sample was recruited via the Kindergarten Association in Seoul. The UK sample was recruited from Employers for Childcare in Northern Ireland (ECNI). Notably, ECNI shared the survey with its counterpart NGOs in the other UK regions; consequently, while the majority of the sample comes from NI (92.6%), it includes some mothers from England and Scotland. Excluding incomplete surveys (defined as those automatically exited from the survey for not meeting the criteria or those that ended the survey after completing criteria questions), the sample comprised 360 UK mothers and 242 Korean mothers. The survey covered demographics, housework, care-work, relationship quality, attitudes on work–life balance as well as parenting, and views on work–family policy needs both prior to the pandemic and at the time of survey (July 2020). The survey was written in English and translated into Korean for the Korean sample. Responses to an open-ended, short-answer text about useful policies were translated from Korean into English. Questionnaires were collected using Microsoft Forms. The data was cleaned in Excel before being uploaded into Stata v15 for analysis. The study protocol was approved by the Queen’s University Belfast Ethics Committee.

Work–family balance scale

Mothers were asked about their perspectives on work–family balance. The following questions were selected from the Work–Family Conflict Scale encompassing time, strain, and behaviour-based conflict (Stephens and Sommer, Reference Stephens and Sommer1996; Ahmad and Skitmore, Reference Ahmad and Skitmore2003): (1) My working hours prevent me from having more quality time with my children. (2) My work responsibilities demand more of my time than my family responsibilities. (3) My family is able to adapt to my working hours and work demands. The five-point Likert responses ranged from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” These were combined into a scale by summing the three questions for those with non-missing responses on all three. The third question (on adaptation) was reverse-coded so that higher values indicate greater work–family conflict. The Cronbach Alpha test reported a satisfactory scale reliability coefficient of 0.5890.

Unpaid labour

Unpaid labour was captured from multiple angles to distinguish housework and childcare, between mother and partner contributions, and identify what the contributions were prior and after pandemic control measures came into effect. Participants reported how many additional hours they and their partner each spent on childcare since the pandemic began. Responses were collapsed into three categories: “fewer hours,” “no extra hours” and “more hours” (combining 1–5, 6–10, or 11+ more hours). Due to small numbers, “not involved in childcare” and “do not know” were excluded. Furthermore, participants were asked who mainly looked after their young children (0 to 18 years old) when they were not at school or daycare after pandemic control measures were introduced. Participants gave separate responses for themselves and their partner ranging from “always” to “never.” Due to low numbers, “never” responses were combined with “sometimes,” while “not applicable”/“don’t know” were combined with non-responses into a missing flag category.

Regarding housework, participants identified how many hours their partner spent on housework (e.g., cooking, washing, cleaning, care of clothes, shopping, maintenance of property) in the last week, excluding childcare and leisure activities. Response options originally ranged from “none” to “41 hours or more,” including five options in 10 hour increments in between, plus “don’t know.” Based on the distribution of responses, however, these were subsequently consolidated into three: “none,” “1 to 10 hours,” and “11 or more hours.” The few “don’t know” responses were recoded as missing data. Participants were also asked if their partner was “doing more” or “doing less” housework since pandemic control measures came into effect or if there had been “no change.”

Participants were asked about their own housework activities. As none of the mothers reported doing zero hours of housework, three final categories emerged: “1 to 10 hours,” “11 to 20 hours” and “21 or more hours.” Participants were also asked if their household tasks had changed since pandemic measures were enforced. Their responses were ultimately grouped into three categories, including “doing less” (identified from the response “I have been spending fewer hours on household tasks than before”) and “no change” (identified from the response “no extra hours”). The responses “about 1–5 extra hours” and “about 6–10 extra hours” were combined into a single category of “doing more.” The few “don’t know” responses to either question were coded as “missing.”

Additionally, participants were asked to choose the response that best described how they and their partner shared housework, both currently and before pandemic measures were enforced. Three responses were available for both questions: “I do more than my fair share,” “I do roughly my fair share,” and “I do less than my fair share.” To capture participants’ feelings about the fairness of both current and previous arrangements, their responses were combined into five categories. Three groups capture those reporting identical current and pre-Covid responses: “Always more,” “Always fair,” and “Always less.” A minority of participants reported a change in perspective before and after Covid measures; due to the low numbers involved, these were combined into two groups: “doing more” (e.g., was ‘doing equal’ pre-Covid but ‘doing more’ post-Covid), and “doing less” (e.g., was ‘doing equal’ pre-Covid but ‘doing less’ post-Covid). The six no-response answers were kept as missing.

Gendered parenting

Using a Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” participants were asked to reflect on the following statements about gendered parenting: “Mothers are usually more nurturing than fathers” and “I feel my partner has all the necessary skills to be a good father.” Based on the distribution of responses, the original responses to the assertion that “mothers are more nurturing” were coded as “agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” and “disagree,” with “don’t know” and “non-response” combined into a missing flag category. Responses to the statement regarding fathering skills were coded as “strongly agree,” “agree,” and “neither agree or disagree”/“disagree”, with “don’t know,” “not applicable” and missing data combined into a missing flag category.

Demographics

Regarding the age of participants, three categories were developed: “18 to 35 years old,” “36 to 45 years old” and “46 or older.” From the number of children that participants reported, three categories evolved: “1 child,” “2 children,” and “3 to 4 children”. No participant reported having more than four children. In responding to the question, ‘What age are the children living in your household?’, participants were offered two categories, “0 to 5 years old” and “6 to 18 years old,” and asked to tick all that applied. Their responses were then recoded as two mutually exclusive categories to facilitate analysis and to account for those caring for younger children: “any children 0 to 5 years old” and “only children 6 to 18 years old”. To determine employment background, participants were asked which of five options best described their employment status before pandemic control measures came into effect. These five options were then merged into three categories, including “full-time employment” and “part-time employment”; “self-employed” and “other” were combined as “other category”; “not working” was excluded from the analysis. Lastly, to capture their experience of financial stress, participants were asked, “Has the coronavirus pandemic impacted your family’s ability to meet financial obligations?” The six original response options were then merged into four categories, including “no impact,” “minor or moderate impact” and “major impact,” with “too soon to say,” “prefer not to say” and “missing” incorporated into a single category of “too soon/missing.” Due to the small number of participants who responded “missing” or “don’t know” to the above measures, the final analytical sample for the purpose of regression analysis was n = 344 UK mothers and n = 224 Korean mothers.

Family policy

Lastly, participants were asked to identify family policies that could improve work–family balance. Participants could select one or more of the following options: “Good quality and affordable childcare”; “Flexibility in your working time”; “Parental leave provision”; “Father-specific leave policy (e.g., Daddy leave)”. Participants could also provide additional information by responding to the prompt “If there is a welfare service not listed above that would be most helpful to you in balancing work and family life, please write it in the space below.” In total 128 UK and 80 Korean participants provided written responses. Although participants were asked to write down any other policies they felt would be helpful, most mentioned only those referenced in the close-ended questions. However, open-ended responses generated more detailed information about participants’ views on gender inequality in unpaid work, workplace culture, and the use of work–family policies.

Data analysis

To understand how changes in the gendered division of unpaid labour during the COVID-19 pandemic shaped work–family balance, the first part of the analysis involved OLS regressions investigating participant and partner characteristics on work–family balance by country. Interactions by country were run to determine if the relationship between unpaid labour and work–family balance varied by country. The second part of the analysis considered how work–family policy might explain variations between the UK and Korea by examining the policy needs of each country.

Results

Descriptive statistics

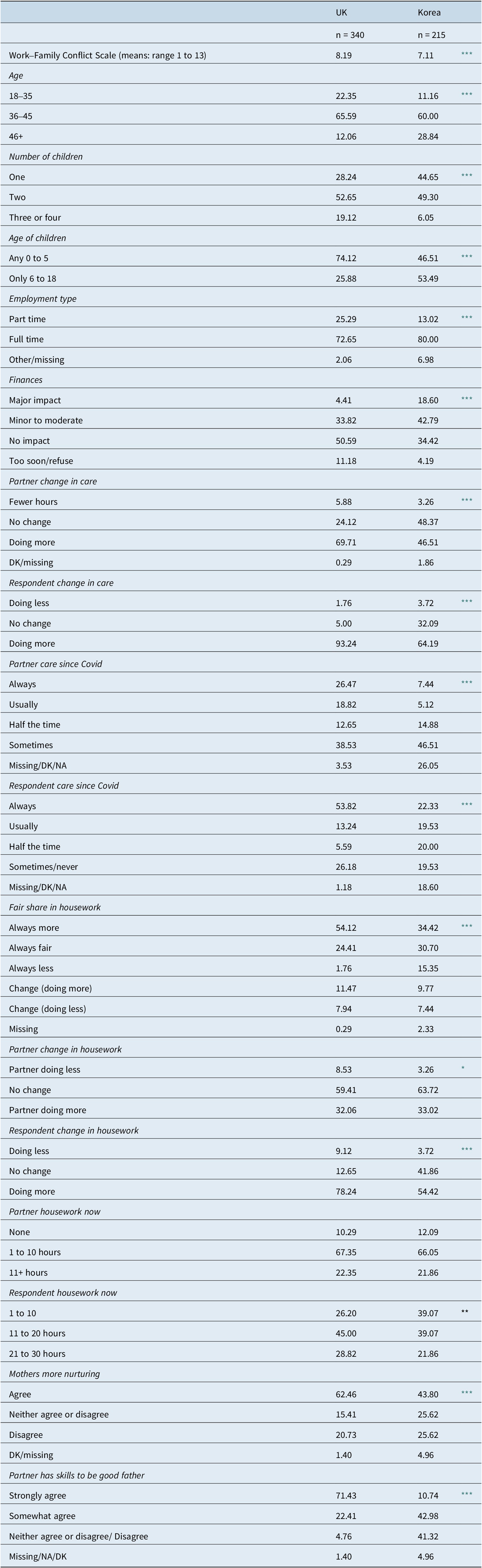

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the measures used in the OLS regressions. Regarding the change in childcare hours, 93% of participants and 70% of partners in the UK were providing more care, compared to 64.2% of participants and 47% of partners in Korea. Furthermore, when asked how often their partner provided childcare since pandemic control measures were introduced, the most common response from participants in both countries was “sometimes” or “never” (39% UK, 47% Korea). By contrast, when asked how often they provided care themselves, the most common response was “always” (54% UK, 22% Korea). That UK participants reported both doing more childcare and a greater change from pre-pandemic levels compared to Korean participants may reflect the full national lockdown in the UK.

Table 2. Descriptive characteristics

Note: Country differences using t-test on means differences for Work–Family Conflict Scale otherwise Chi-Square on percent distributions.

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.001.

Turning to housework, the majority of participants in both countries reported no change in the number of hours their partners spent on childcare during the pandemic (1–10 hours when surveyed). By contrast, 78% of UK mothers reported doing more housework, compared to 54% of Korean mothers, with the highest percentage of participants in both countries (45% in the UK, 39% in Korea) reporting doing 11–20 hours per week. Regarding perceived fairness, most mothers in both countries felt there had been no change, with 54% of UK mothers and 34% of Korean mothers reporting that they did more than their fair share before and after pandemic measures were enforced.

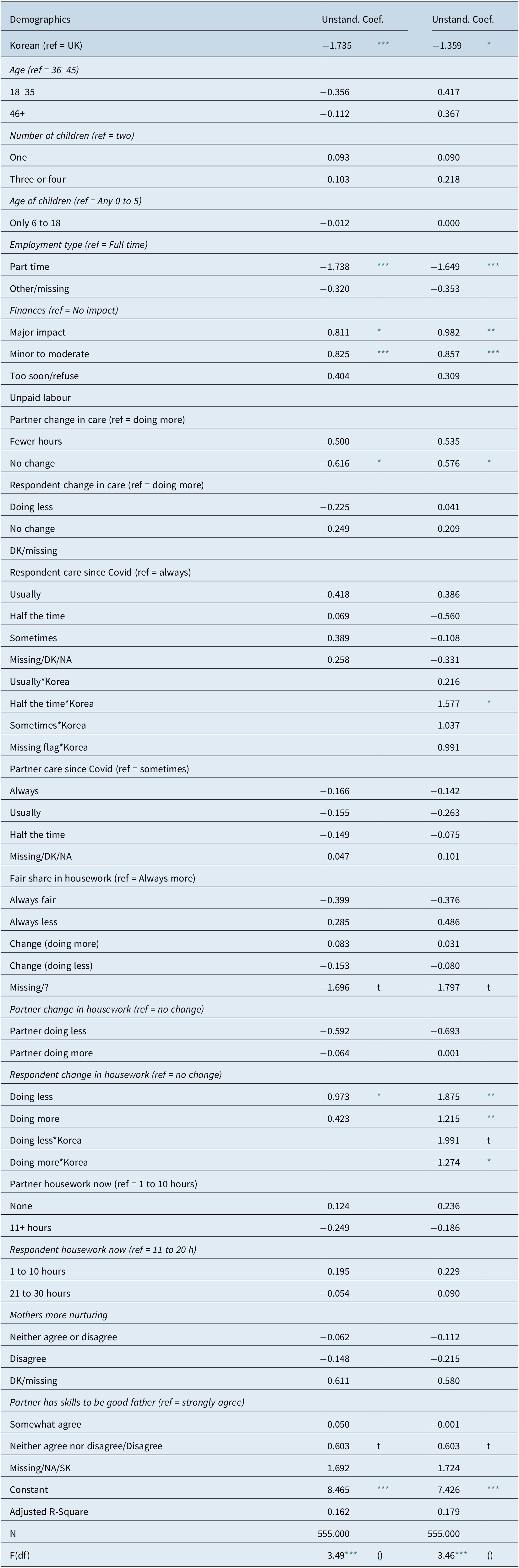

Multivariate analysis

Table 3 presents the OLS regressions investigating how the gender dynamics of changes in an amount of unpaid labour during the COVID-19 pandemic shape work–family balance by country. As Model 1 shows, Korean participants reported lower work–family conflict on average, controlling for demographics, unpaid labour, and gendered attitudes towards parenting related to work–family balance (B = −1.735, p < 0.001). In terms of demographics, those working part-time had significantly lower work–family conflict than those working full-time, and those who reported that COVID-19 had either “a major or minor-to-moderate impact” on their finances experienced higher work–family conflict on average than those reporting “no financial impact”. Regarding unpaid care, those reporting no change in their partner’s contribution had lower work–family balance than those whose partners were doing more. Moreover, participants doing less housework had lower work–family balance on average than those experiencing no change. Although unexpected, this finding may reflect a need for more care work from partners due to increased disruption of work-family balance by COVID-19 as participants were diverted from housework to other duties, such as care work or job responsibilities.

Table 3. OLS regression of unpaid labour during covid on work–family balance (higher score equates to greater work–family conflict)

t p < 0.10;

* p < 0.05;

** p < 0.01;

*** p < 0.001.

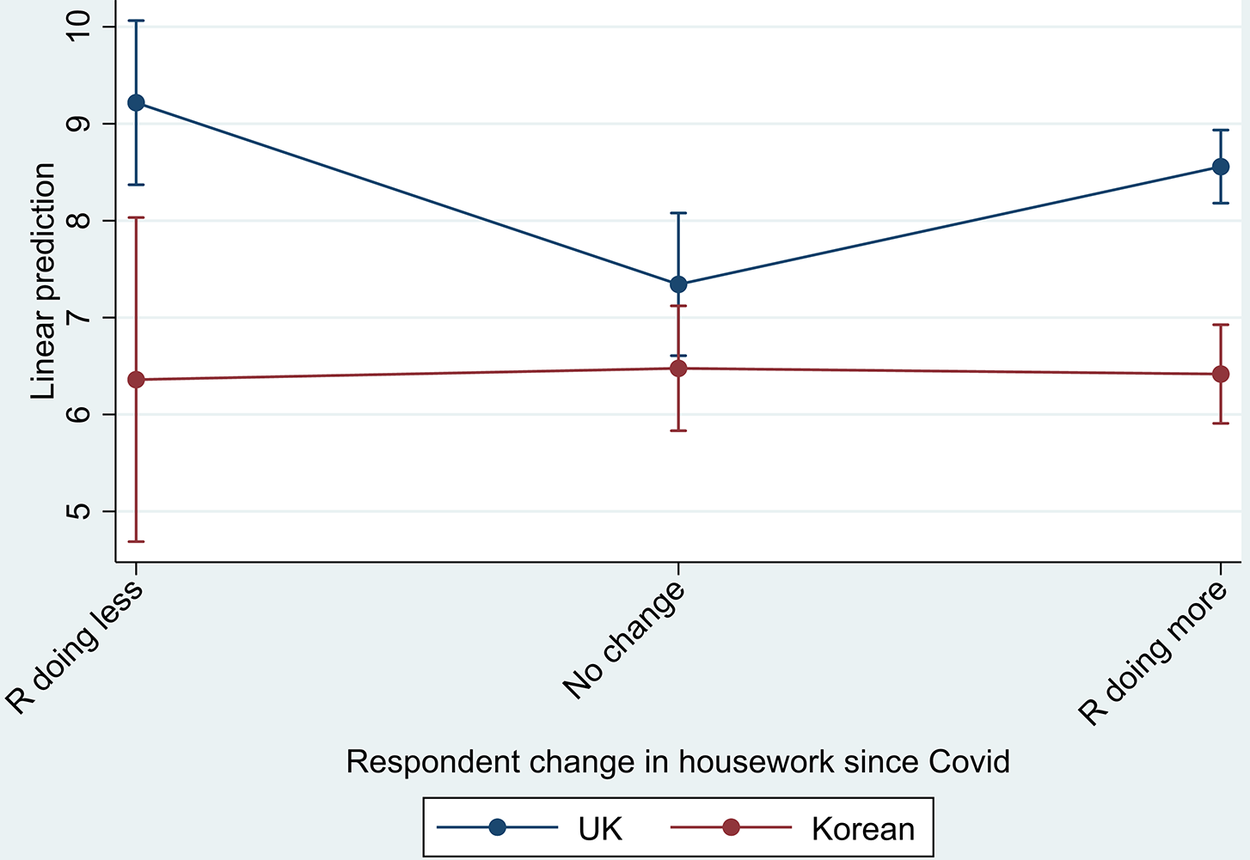

Furthermore, participants who “disagree” or “neither agree nor disagree” that their partner has the skills to be a good father had on average higher work–family conflict compared to those who “strongly agree” (p = 0.077). Model 2 includes interactions to show how these characteristics on work–family balance might differ by country. Employment, finance, change in partner’s contribution to care, and partner fathering skills did not have statistically significant interactions, suggesting these relationships with work–family balance operate in similar ways in the UK and Korea. However, the amount of time the participant spent on care since the pandemic did reveal differences in country interactions (Figure 1). UK participants who reported that, since the pandemic, they “always” did the care work had higher levels of work–family conflict than those who did so only half the time, whereas Koreans who said they “always” did it had less work–family conflict than those who did it half the time. Notably, these Korean participants also reported that grandparents provided more care than their partners, with 28% reporting that grandparents “always” or “usually” helped, compared to 13% who said their partners did so (data not shown). Another significant difference is that UK mothers showed higher work–family conflict on average whether they did less or more housework than before the pandemic compared to those for whom there had been no change, whereas Korean mothers had around the same work–family conflict score whether their housework burden had changed or not (Figure 2). This may reflect the fact that, at the time of the survey, the UK was subject to a more restrictive lockdown than Korea, and UK families experienced greater disruption to their homelife during the pandemic.

Figure 1. Predictive margins on Work–Family Balance (higher score equates to greater work–family conflict) for interactions between frequency of respondent care since Covid by count.

Figure 2. Predictive margins on Work–Family Balance (higher score equates to greater work–family conflict) for interactions between respondent change in housework since Covid by country.

Policy analysis

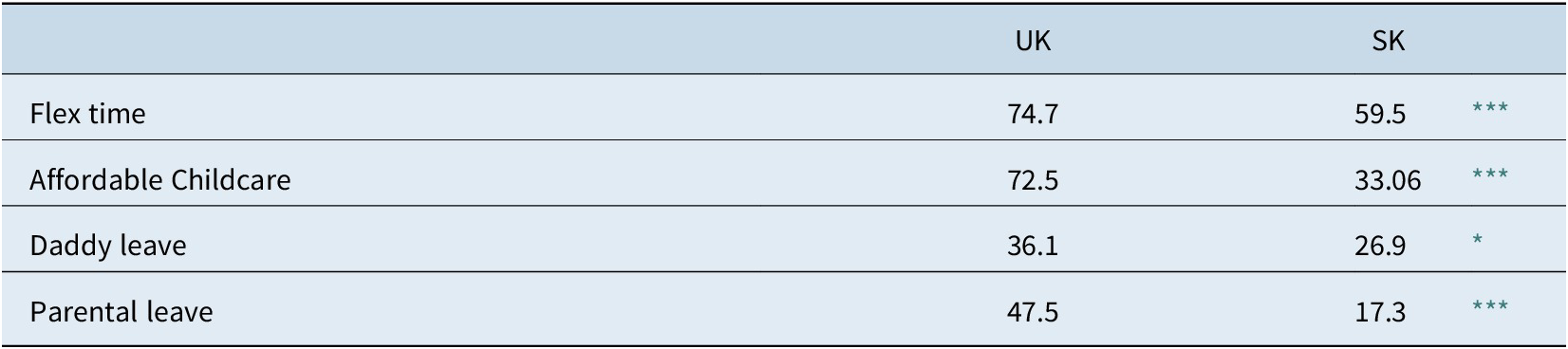

The cross-cultural family policy context is summarised in Table 4, which shows the extent to which participants felt flexi-time, affordable childcare, daddy leave, and parental leave would improve work–family balance. A higher percentage of UK mothers indicated support for these policies compared to Korean mothers, with the differences reaching statistical significance. This could be because these options are more available in Korea than in the UK, and therefore their usefulness has already been established and/or barriers to uptake identified. It is important to highlight, however, that the children in the Korean sample were relatively older, which could also be a factor.

Table 4. Percentage agreeing services that would make work–family balance better by country

Note: Chi-Square Tests; Not mutually exclusive.

* p < 0.05;

*** p < 0.001.

Text analysis: mothers’ views on work–family balance policies

The survey included the question, “Which policies would be useful for you to balance work and family?” While childcare, flexible working hours, parental leave for fathers, gendered expectations of childcare, and long working hours were common themes for participants in both countries, thematic differences were also apparent. UK respondents highlighted the difficulties of balancing work and family during the pandemic, whilst Korean participants focused on changing aspects of workplace culture that make existing work–family policies ineffective.

The majority of UK participants stressed the importance of high-quality, affordable childcare. Of these, many sought more government support to address the high cost of childcare, while others underscored the need for childcare at “evenings and weekends,” and “afterschool care”. Childcare was the second most frequently mentioned topic for Korean participants, but they mainly focused on increasing the number of public kindergartens rather than financial support, perhaps because the Korean government covers formal childcare costs. Interestingly, several Korean participants, noting the important role grandparents play in childcare, advocated financial support for grandparents looking after grandchildren.

Flexible working hours were the second most important issue for UK participants, and the most frequently mentioned by Korean participants. Participants from both countries identified working from home, reduced hours, and staggered starting and finishing times as useful policies. Likewise, both UK and Korean participants considered a workplace culture of long working hours and overtime as the main obstacle to work-family balance and women’s career progression. Interestingly, Korean participants highlighted the importance of extended annual leave and family emergency leave, as they often use their annual leave for family emergencies. This practice also was evident in (Sung, Reference Sung and Sung2025b).

Father-specific leave was another significant issue, and the third most frequently mentioned theme for both participant groups. UK participants emphasised that paternity leave must be “extended,” “better paid,” and “culturally normal.” Gendered expectations that mothers are “the main carer’ and must ‘sacrifice their jobs to care for children” were noted, as was the extent to which workplace culture was geared towards these expectations because men are embarrassed to take parental leave or request flexible hours. Unequal sharing of childcare duties was also mentioned, underscoring the need for policies that encourage fathers’ involvement in childcare. Interestingly, while Korean participants raised similar issues, they felt men lacked the necessary skills to look after children and underlined the importance of training fathers to provide childcare. They also mentioned the disadvantages that women experience because of gendered patterns of policy-use whereby women are more likely to avail of parental leave and family emergency leave (Thebaud and Pedulla, Reference Thebaud and Pedulla2022).

Furthermore, both UK and Korean participants highlighted challenges of work–family balance for working mothers, who carry the double burden of paid and unpaid work and the expectation ‘to perform as full-time parents and full-time workers’. However, UK participants particularly highlighted the challenges brought by COVID-19, such as working from home while having to homeschool when the schools closed.

Discussion and conclusion

Gender disparity in unpaid care work intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the school and childcare centre closures, placing greater pressure on working mothers (Bernhardt et al., Reference Bernhardt, Recksiedler and Linberg2023). This article explored these work–family balance issues and policies from a gender perspective in the UK and Korea, by examining key related factors, including gender differences in unpaid work time, gendered parenting, mothers’ perceptions of work–family balance, and policy implications.

Time is a significant indicator when analysing work–family balance issues, as cultural differences in relation to gender roles contribute to gender differences in time-use. Unequal sharing of unpaid work is apparent in both countries, as mothers overall spend more time on housework and childcare than fathers. However, gender disparity in time spent on unpaid work tends to be greater in Korea, where traditional gender role attitudes are more prevalent (Craig and Van Tienoven, Reference Craig and Van Tienoven2021). Research has shown that women are more likely than men to experience an increase in childcare and domestic chores if they start working part-time, suggesting that the time gained by reducing their working hours is often transferred to family duties (Warren and Lyonette, Reference Warren, Lyonette, Felstead, Gallie and Green2015). During the pandemic, women in the UK were more likely than men to reduce their working hours to balance their work and family responsibilities. Moreover, findings suggest that participants whose partners increased their childcare contribution had greater work–family conflict than those who experienced no change. This is consistent with previous studies, in which both fathers and mothers reported a high level of time stress and dissatisfaction with work–family balance during the pandemic due to increased unpaid work time (Craig and Churchill, Reference Craig and Churchill2021). However, the additional contributions from fathers were insufficient to reverse pre-existing gender inequalities, as mothers’ unpaid work time went up even more (Garcia, Reference Garcia2022). Furthermore, the vast majority of participants saw no change in the level of fairness in how housework was shared before and after pandemic control measures were implemented. The findings show that differences in national lockdown policies meant UK families experienced a larger increase in unpaid work hours more, which may partly explain the higher work–family conflict seen among UK participants.

Moreover, our analysis suggests that Korean mothers may not perceive partner support as the solution to work–family imbalance. Korean mothers doing less informal care would be expected to experience less work–family conflict, but the findings showed the opposite effect. This suggests that Korean women doing care half the time are not necessarily sharing responsibility equally with their partners and instead are relying heavily on grandparental support. This is supported by our supplementary analysis that the percentage of UK grandparents “always” or “usually” doing childcare was small before Covid (9.0%) and decreased significantly afterward (1.5%), whereas Korean grandparents’ involvement in childcare was notably higher before Covid (28.1%) and increased afterward (34.4%). By contrast, a higher percentage of UK fathers “always/usually” provided care both before (28.5%) and after Covid (46.4%), compared to Korean fathers (16.4% before, 17.6% after). Korean fathers provided the least childcare, doing less than both UK fathers and even Korean grandparents. These results align with An’s (Reference An2018) study, which indicates the significant role of Korean grandparents in childcare. Given that grandmothers are more likely to be involved in childcare than grandfathers, this finding reflects the gendered division of labour within the Korean family, in which care is provided primarily by women. Furthermore, participants who thought that their partner had the skills to be a good father showed (marginally) lower levels of work–family conflict. Koreans were much more likely to disagree that their partners had strong fathering skills.

Differences were also apparent in participants’ views on work–family policy. Although both UK and Korean participants underscored the importance of policy development in relation to childcare and flexible working, Korean mothers highlighted the need for cultural change, arguing that useful policies already were in place but were ineffective because the workplace culture prevented employees from availing of them. By contrast, UK participants stressed the importance of financial support with childcare costs.

Daddy/parental leave was the third most frequently mentioned useful family policy by both UK and Korean participants. In the UK, the percentage of participants who reported needing daddy/parental leave and affordable childcare was significantly higher than in Korea (see Table 4), perhaps because well-paid, father-specific leave, and universal free childcare are already available in Korea. Moreover, the challenges created by COVID-19 were particularly highlighted by UK mothers, perhaps because the rules governing social distancing were tighter in the UK than in Korea.

These findings strongly suggest that work–family policies must be further developed in both countries. In the UK, high-quality and affordable childcare is needed, and father-specific leave should include more generous income-replacement to encourage fathers to take parental leave. “Gender-neutral” childcare leave policies (e.g., shared parental leave in the UK) appear ideal in theory, but there is a danger that the true imbalance manifests in families could be overlooked due to gender inequalities imbedded within society (Burnett et al., Reference Burnett, Gatrell, Cooper and Sparrow2010, p. 545). For instance, parental leave may be available regardless of gender, but mothers are more likely to avail of the policy because of gender-role attitudes, organisational culture, the gender pay gap, and so forth. Studies have found that men’s use of parental leave increases when father-specific leave is offered on a use-it-or-lose-it basis, is non-transferable to the mother, and includes financial incentives (OECD, 2017; Mitchell, Reference Mitchell2022). In Korea, policies supporting flexible working patterns must be further developed to ensure that the reduced working hour scheme is not used to replace parental leave. Additionally, despite notable policy developments (e.g., “daddy” months and universal childcare), Korean men’s involvement in childcare has not greatly improved (Jeong, Reference Jeong2024), with Korean women spending much more time on unpaid work (OECD, 2022). To facilitate the cultural shift required to redress this, policies promoting gender equality in paid and unpaid work must be developed. More “gender-responsive” policies to encourage men’s involvement in care, together with a shift in organisational culture to allow men to take parental leave and adopt flexible working patterns, will be crucial to eradicate the gender disparity arising from the negative impact of these factors on women’s career progression.

This study has a number of limitations. The research design involved online collection of primary data, not a panel survey, and therefore cannot claim to be representative of the general population. Furthermore, because the survey was conducted during the first phase of the pandemic (July 2020), its findings do not reflect changes in women’s experience throughout its duration. Also, the study captured the perspectives of working mothers in relationships with men; the views of fathers and those in same-gender relationships were not examined. Further research into fathers’ views on gender differences in the division of labour, how same-gender couples manage responsibility for unpaid work and its impact on work–family balance issues would help to deepen understanding in the field of gender and family policy development. Nevertheless, this study sheds light on the gendered division of unpaid work during the pandemic and its impact on women seeking to balance work and family in two countries with evident differences in gender culture and work–family policies. While the fact that most UK participants are from NI is an acknowledged limitation, it also contributes to the literature, as there has been little research on work–family issues and policies from a gender perspective in NI.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the working mothers who participated in our research, without whom this article would not have been possible. We also appreciate the support we had from the Kindergarten Association in Seoul, South Korea, and Employers for Childcare in Northern Ireland. Our special thanks go to Ms Aoife Hamilton, currently the Deputy Chief Commissioner to the Board of the Charity Commission for Northern Ireland and the former Head of Charity Services at Employers for Childcare, who supported us to gain an access to survey participants. We are also grateful for the constructive and insightful feedback we received from anonymous reviewers.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work (SSESW), Queen’s University Belfast, UK, under the Research into Covid-19 funding scheme.