The victory at Điện Biên Phủ on May 7, 1954, ended the French Indochina War (1946–54) between Vietnam and France, and brought to Vietnam a temporary peace, but also a long-term division of the country into North and South at the 17th parallel, which lasted until April 30, 1975. Like the 38th parallel on the Korean peninsula and the Berlin Wall, the 17th parallel became a symbol of the confrontation between two superpowers, namely the Soviet Union and the United States, during the Cold War. But the difference between these cases is that, during these twenty-one long years of division, North Vietnam became an object of the most terrible, bloody, and annihilative attacks, the legacy of which still remains.

According to an official report of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) dated September 23, 1975, during the air and naval war against North Vietnam, the Americans dropped over its territory 2,550,000 tons of bombs in total, more than Americans dropped on the Pacific, Europe, and Mediterranean fronts combined during World War II. All six big cities of North Vietnam were bombed, and half of them were completely destroyed. Moreover, 28 of 30 provincial towns, 96 of 116 district towns, and 4,000 of 5,788 villages were heavily bombed. In addition, 350 hospitals, 3,000 schools and universities, 491 churches, and 530 pagodas and temples were extensively damaged by bombs. In the economic sphere, 66 sovkhozes (state-run farms), 1,600 irrigation structures, 1,000 dykes, all harbors and power stations, all 6 railroads, and even all railway bridges were destroyed. About 40,000 cattle were killed. The American air and naval attacks killed 10,000 civilians and made 70,000 children orphans and another 10,000 disabled. And, in return, North Vietnam shot down 4,181 airplanes including 68 B-52s and 13 F-111s, captured 472 American pilots, and fired upon and sank 271 ships of different kinds.Footnote 1

Fighting against the United States and Supplying the War in the South

Facing the escalation of American involvement in Vietnam, on March 27, 1964, President Hồ Chí Minh convened a special political meeting to discuss the chances of the war being expanded through the direct participation of American soldiers. In his report to the meeting, President Hồ Chí Minh underlined North Vietnam’s twofold main task: on the one hand to preserve more human and material resources to increase aid for the struggle in the South, and on the other hand to promote national capacities for defense and to ensure they were ready to resist. He confirmed that “if they [the Americans] risk touching the North, they certainly will be defeated.” President Hồ Chí Minh called on all North Vietnamese to double their workloads and produce twice their output in order to better serve their Southern compatriots. This meeting played an important role in the warfighting, similar to the Diên Hồng meeting in the thirteenth century, organized by the Trần dynasty to discuss how to fight against Mongol invasions. After focusing on these twofold tasks of North Vietnam, President Hồ Chí Minh appealed to the people: “Keep in mind your oppressed Southern brothers and sisters as you toil, labor, and work on their behalf too.” Following this appeal, there was a series of competitions held among people in the whole of North Vietnam: for example, “Three Improvements” (ba cải tiến), “Three Undertakings” (ba đảm đang), “Three Readies” (ba sẵn sàng), “Three Firsts Flag” (cờ ba nhất; referring to the army movement encouraging all to be the best and the most uniform and to achieve the most), and “Medical doctors are as kind as Mother” (Thầy thuốc như mẹ hiền). Many proverbs, sayings about the North helping the South, appeared during this time, such as “There is not a single pound of rice missing, and the army is full, not lacking a single person” (Thóc không thiếu một cân, quân không thiếu một người). In Thái Bình, an agricultural province in the Red River Delta, there was a popular movement known as “rice field providing 5 tons of rice” (cánh đồng 5 tấn).

On August 7, 1964, the US Congress approved the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which allowed President Lyndon B. Johnson to greatly escalate US military involvement in the Vietnam War. The USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy were sent to the area that year in order to conduct reconnaissance and to intercept North Vietnamese communications in support of South Vietnamese war efforts. By the night of August 4, the US military had intercepted North Vietnamese communications that led officials to believe that a North Vietnamese attack on its destroyers was being planned. That night proved to be a stormy one. The Maddox and the Turner Joy moved out to sea, but both reported that they were being fired upon by North Vietnamese patrol boats. Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution at the insistence of President Johnson, with the understanding that he would not use it to go to war. Facing the escalation of the US air and naval war against the North, in March 1964, the North Vietnamese Ministry of National Defense decided to increase the number of permanent soldiers to 300,000.Footnote 2

“Special Warfare” to “Limited Warfare”

North Vietnam transitioned from conducting “special warfare” (chiến tranh đặc biệt) to enter a new phase of working to defeat the United States in “limited warfare” (chiến tranh hạn chế) following Johnson’s approval in July 1965 of the search-and-destroy strategy of General William Westmoreland, the commander of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV). That year, the Vietnamese people’s resistance to US military intervention entered a new period of “local warfare” (chiến tranh cục bộ) with the direct involvement of US soldiers in the South and an enlarged air war in the North. In the new situation, an important question rose to the fore: Should North Vietnam continue the cause of building the socialist transformation of its economy or cease and shift its attention southward? And, if it continued promoting socialism, how should it continue?

On March 25, 1965, the 11th meeting (Session III) of the Central Committee discussed and decided to move the North’s economy from a peacetime basis to a war one. The strategic redirection was a long, difficult, and challenging process. There was a comprehensive strategy including all aspects from ideological and structural ones, to economic construction, to defense capacities. Having considered the reality of wartime, on April 10, 1965, the National Assembly approved a resolution assigning its Permanent Commission the right to approve a state plan, decide on issues relating to the annual budget and taxes, and even to take the decision to convene the National Assembly at an appropriate time. In wartime, the best way to develop was to mobilize the capacities of localities. In April 1966, a government report confirmed: “Developing the local economy with a higher tempo than normal is the main direction for all locals to promote their own forces to fight against enemy according to the guidelines of the people’s war.”Footnote 3 According to these guidelines, all localities were assigned more power, in particular the right to establish an economic plan and a budget for their province. The state did not design a long-term plan; instead the plans ran for one or two years, according to the reality of the war. The production plan had fixed priorities; the first was to serve the demands of war and the needs of the people. To encourage people in the new situation of the war enlarging to the whole country, on July 20, 1965, President Hồ Chí Minh appealed to the people: “Even if [we have] to struggle for five years, ten years, or longer, we will also firmly struggle until complete victory.”Footnote 4

Parallel with building socialism, the CPV also had to construct defenses to fight against the air and naval war being conducted by the Americans. On January 2, 1965, the Politburo issued Decree No. 88-CT/TW concerning a Political Correction Campaign, requiring cadres and people to be fully aware of new situations and tasks in the new phase, “raising revolutionary quality and ethics and criticizing [any] appearance of individualism.”Footnote 5

In January 1965, the Defense Council met under the chairmanship of Hồ Chí Minh. It discussed and set guidelines for a national defense strategy in the new circumstances:

To strengthen the nation’s defenses and to increase security and military preparedness.

To strive to build up strong people’s military forces including a permanent force, a local force, volunteer militias, and a reserve force.

To consolidate the North comprehensively by combining economic and defense tasks.

Based on Resolution No. 102 of the Permanent Committee of the National Assembly, on April 25, 1965, President Hồ Chí Minh signed a decree to announce official mobilization: a number of officers, noncommissioned officers, reserve soldiers, and some reserve civilians who were not yet serving in the army would be mobilized.

In 1965, nearly 290,000 people voluntarily joined the army, so that the number of permanent forces of the North reached 400,000 soldiers. Among them air defense and the air force were strengthened significantly with surface-to-air rockets, warning radar, and fighter jets. Logistics was the other unit that was strengthened rapidly. Đinh Đức Thiện, an alternate member of the Central Committee, who had a lot of experience in leading logistics and transportation during the resistance fighting against the French, returned to the position of director general of the logistics department. The volunteer militia was increased to 10 percent of the population. It was equipped with heavy machine anti-aircraft guns, ranging in size from 12.7mm to 100mm. In parallel the coastal defense force and the sapper forces were increased. In a short time the whole North became the great rear base of the people’s war, allowing it to attack and defend everywhere at any time.

From 1965 to 1967, the Americans carried out an air war against North Vietnam with intensive attacks. From the southern provinces close to the demilitarized zone (DMZ) such as Quảng Bình, Quảng Trị, and Vĩnh Linh, they crossed the 20th parallel heading northward in June 1965. The targets of the attack were military and economic, and especially transportation lines such as the Hàm Rồng bridge and the railways Phú Thọ–Yên Bái–Lào Cai, Hòa Bình–Lạng Sơn, Hanoi–Hải Phòng, and Đông Triều–Hòn Gai. On May 22, 1965, American aircraft bombed two Soviet fishing vessels under charter to North Vietnam in Hải Hậu (Nam Định), damaging one, killing two people, and injuring seven more. Another thirty sailors were rescued. On July 24, 1965, the anti-aircraft rocket troops participated for the first time in a battle together with other forces; they shot down three F-4 aircraft from the height of 23,000 feet (7,000 meters) in Hà Tây province (today Hanoi). In 1965, the total number of American aircraft shot down by North Vietnamese was 834, among them 163 in April, 111 in September, and 105 in October.Footnote 6 Up to April 30, 1966, the North’s air defense forces shot down 1,005 planes and captured many pilots.

In 1966, in order to support ground forces in the South, the Americans intensified the air war attacking the North. Over the course of two days in 1966, April 14 and 27, several groups of B-52s bombed National Route 12 through Quảng Bình province with the aim of cutting transportation through the border with Laos connecting with People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) Group 559, which was in charge of maintenance and extension of the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. Alongside bombing of main transportation links, other targets of American attacks included military bases, industrial zones such as the Uông Bí and Cao Ngạn thermal power stations, the Cẩm Phả coal mine, and the Thái Nguyên cast iron zone, among others. Moreover, American aircraft bombed the areas surrounding Hanoi and Hải Phòng, focusing on gas and petroleum storage facilities. The more aircraft they sent, the more were shot down. During a single month from July 17 to August 17, 1966, 138 American airplanes were shot down (on average 4.4 aircraft a day). After more than one month of bombing gas and petroleum storage facilities, the CIA reported that 70 percent of North Vietnam’s gas and petroleum storage capacity had been destroyed. However, a secret document from the US Department of Defense had to admit that the bombing of oil storages had failed. There was no evidence to show North Vietnam faced any difficulties of lacking oil.Footnote 7

In 1967, a year of strategic importance for both the United States and Vietnam, American air forces increased their attack on North Vietnam and focused on six objectives, namely power facilities, industry, transportation, reserve fuel storage, airports, and air defense bases. On the one hand they bombed areas around big cities such as Hanoi and Hải Phòng; on the other hand they scattered land mines and torpedoes in rivers and estuaries, and controlled the coastal areas from the 17th to the 20th parallel with their navy. According to Don Oberdorfer, until the end of 1967, Americans dropped approximately 1,630,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnam, more than dropped on European battlefields during World War II, double what it dropped in the Korean War, and triple what it dropped on the battlefields of the Asia–Pacific region during World War II. On average each square mile of North and South Vietnam received 12 tons (4.6 tons per square km) of bombs, about 110 lb (50 kg) of bombs per capita.Footnote 8 American bombardment caused heavy damage to North Vietnam. According to the CIA, the US Air Force’s Operation Rolling Thunder alone killed 13,000 people in North Vietnam in 1965, 24,000 in 1966 (of whom 80 percent were civilians), and approximately 29,000 in 1967.Footnote 9 According to research done by the PAVN General Staff’s Department of Operations, during four years of the American air and naval war (1964–8), 14,000 North Vietnamese soldiers and 60,000 North Vietnamese civilians were killed by bombs and bullets.Footnote 10 Beside the catastrophic levels of human lives lost, North Vietnam was heavily damaged materially: 391 schools, 92 healthcare facilities, 149 churches, and 79 pagodas were destroyed, while 25 of 30 towns and 3 of 5 cities were bombed many times.

But there was an irony: the more the Americans attacked, the less they achieved. The former US secretary of defense Robert S. McNamara admitted that “bombing did not achieve its basic goals: as Rolling Thunder intensified, US intelligence estimated that infiltration [of Northern soldiers into the South] increased from about 35,000 men in 1965 to as many as 90,000 in 1967, while Hanoi’s will to carry on the fight stayed firm.”Footnote 11 McNamara did not know what his counterpart on the other side was thinking. According to Võ Nguyên Giáp in 1967, after two years of war, the more the Vietnamese fought, the stronger they became, and he believed they would definitively defeat the United States. Võ Nguyên Giáp pointed out the US mistake the Americans perhaps never considered: “the decision to bring a big expeditionary army to invade the south of our country was one of the biggest strategic mistakes in the history of American imperialism. Within this strategic mistake, the use of the air force and navy to expand the war to the North was again one of the most serious mistakes and one of the most stupid measures of the US imperialists. Still, the generals of the Pentagon were thinking that only escalation of the war to the North could take the initiative and improve the war situation.”Footnote 12

Building the Great Northern Homefront

The will of North Vietnam was confirmed decisively by President Hồ Chí Minh in his appeal on July 17, 1966, as the peak time of the war in both South and North Vietnam: “The war may last for five, ten, twenty years or even longer; Hanoi, Hải Phòng, and some cities, factories may be destroyed; however, the Vietnamese people are wholeheartedly committed. Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom. After the day of victory, our people will rebuild our country to be more comfortable, bigger, and more beautiful than today.”Footnote 13

Hồ Chí Minh’s persona represented the power of unity and national spirit in the struggle of fighting for independence and unification. He knew how to encourage people when they fulfilled their task excellently. On his birthday, May 19, 1967, he sent eight flower baskets to the missile and anti-aircraft artillery units around Hanoi, which had shot down seven American aircraft that day. On one afternoon in July 1967, having listened to the report of his secretary Vũ Kỳ about the artillery battery that was on the alert on the roof of Ba Đình Hall, Hồ Chí Minh withdrew 25,000 dong from honorariums he had received from international newspapers, and presented the monetary award to the soldiers to celebrate.Footnote 14

By the end of 1967, North Vietnam had already shot down 2,680 American aircraft. Amid the spate of victories, on June 16, 1967, the first female volunteer militia from Hoa Lộc commune, Hậu Lộc district, Thanh Hóa province, shot down an A-4D with infantry rifles. Following this, on October 14 and 24, 1967, a platoon of veteran volunteer militia from Hoằng Trường commune, Hoằng Hóa district, Thanh Hóa province, shot down two more American aircraft in their home area also with infantry rifles.

Alongside shooting down aircraft, North Vietnamese people still rescued many American pilots and kept them alive as prisoners of war after the latter had jumped out of their flaming planes. John McCain, later a US senator and presidential candidate, was retrieved by Mai Van On from Truc Bach Lake in Hanoi on October 26, 1967. Pete Peterson, who later served as the first American ambassador to Vietnam (from April 1997 to July 2001), was captured by Nguyen Van Chop on September 10, 1967, in An Bài village, An Bình commune, Nam Sách district, Hải Dương province.

Responding to President Hồ Chí Minh’s appeal, 268,974 young people voluntarily joined the army in summer 1966 with the spirit of “Split the Truong Son Mountains to save the country” (Xẻ dọc Trường Sơn đi cứu nước). The percentage of the population in volunteer militias increased from 8 percent in 1964 to 10 percent in 1965. The number of householders joining agricultural cooperatives increased from 84 percent in 1964 to 94.1 percent in 1967, and 94.8 percent in 1968. There were 23,264 agricultural cooperatives with 29,896 members.Footnote 15 Compared with 1964, the total value of mechanized agricultural output in 1967 increased 40.5 percent. During the period 1965–8, the production of food remained as high as in 1964; in fact in 1965 it was even higher at 5,562,000 tons. In industry, the number of factories increased from 1,132 in 1965 to 1,352 in 1969. However, due to war circumstances, the average industrial output decreased by 2 percent. In the academic year 1967–8 the number of students reached more than 6 million, compared to 4.5 million pupils in the academic year 1964–5. Accordingly, the number of teachers in schools increased from 77,685 in 1964–5 to 102,697 in 1967–8, and the number of lecturers in universities increased from 2,750 to 6,727. In 1964–5 there were 9,295 schools and 16 universities, and by 1967–8 those numbers had increased to 11,497 and 35 respectively. In terms of printing, in 1965 1,887 books were published in more than 22 million copies, while in 1968 this number increased by another 1,471 books, with 30 million copies published. In 1964 there were 176 libraries, then in 1967, even after the bombing, this number remained 176. In terms of public health, in 1964 there were 457 hospitals, 7 nursing homes, and 5,289 healthcare stations; by 1967 those numbers increased to 981, 50, and 6,043 respectively. In 1967, there were 60,000 medical doctors, nurses, physicians, and midwives and 9,435 pharmacists.Footnote 16

One of the most important tasks of the North during the war was supplying South Vietnam. Immediately after Resolution 15 (1959), the Politburo planned to establish a military transportation unit along the Truong Son Mountain range named Group 559 (mentioned above) and a maritime transportation unit in the East Sea (the South China Sea) named Group 759. In the beginning, Group 559 mostly transported supplies by bicycle. Based on the old communications roads that had existed during the French Indochina War, Group 559 reconstructed and opened roads, established stations along them, and arranged the first transportation of weapons and food to supply the South. Secrecy was the most important watchword of Group 559. Its most popular saying was “Walk without a trace, live without a shack, cook without smoke, speak without a voice” (Đi không dấu, ở không lán, nấu không khói, nói không tiếng). In August 1959, the first wave of soldiers and goods arrived in the South. On August 20, 1959, Group 559 handed over to the V Military District 31 tons of goods including 1,700 guns with ammunition. Up to 1960, each month Group 559 transported on average five tons of goods to Palin (Western Thừa Thiên Huế). In the meantime, Group 759 used fishing boats with motors and small ships of the T50 and T100 models to transport the first wave of goods from Hải Phòng port and the IV District to the provinces of V District and the southern part of Vietnam. In the first ten months of 1960, there were 5 ships (each carrying 50–60 tons) that traveled 21 times to the coastal provinces of the South.

To meet the higher demands from the South, in June 1965, the party decided to develop Group 559 into a “motorized transport network” (mạng lưới đường vận tải cơ giới) so that it could more quickly transport more soldiers, weapons, food, and other war materiel to the South. In parallel, on June 21, 1965, the prime minister issued Decree No. 71-TTg to establish “Youth Volunteers against the United States for the Salvation of the Country” (Thanh niên xung phong chống Mỹ cứu nước). Responding to guidelines from the government, from the middle of 1965, all the provinces of the North proactively organized their youth volunteer groups to meet the requirements of making transportation feasible. On April 25, 1965, Thanh Hóa province established its youth volunteer organization with 1,200 members. During June 1965 alone, 8,856 volunteers from Hà Tĩnh, Quảng Bình, Ninh Bình, and Nam Hà provinces joined Group 559 to help with transportation tasks. Until July 1965 the youth volunteer movement (in which women participants were the majority) set a record as the number of volunteers exceeded demand many times over.

This force of youth volunteers served mostly on the transportation network. According to this strategy, to ensure the transport network always flowed freely became the one central task of the whole party, the army, and the people; this task held strategic importance both for the consolidation and defense of the socialist North and for aiding the war of liberation in the South and supporting revolution in friendly countries. On the whole, from 1965 to 1968, more than half the personnel and 80 percent of the weapons, ammunition, and other technical means were sent from the homefront in the North to the battlefields in the South. Among these supplies, human resources formed the major part. During the three years from 1965 to 1968, 888,641 young people joined military forces, among whom 336,900 marched over mountains, across rivers, and through forests to reach the South. In 1968 alone, North Vietnam mobilized 311,749 in the army and supplied 141,084 soldiers for the fronts in the South. Among Northern regions, Military District No. 3 was prominent because it contained two-thirds of the Northern population.

Among the localities of North Vietnam, the autonomous Northwest Region played an important role in supplying the South. This region is mountainous with a difficult economic situation, and it was home to many different ethnic minorities. However, according to a regional party conference addressing the five-year mobilization drive from 1965 to 1969: “The outstanding achievement was that no single ethnic group had no person joining the army over the past five years. The quality [of the mobilization drive] was good. In general, it was clear that the party had pursued a long-term strategy of readying local forces as well as developing and building up the homefront.”Footnote 17

In the Northwest Region, in comparison to other regions of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN), the mobilization of people into a professional army was no easy task because of the distrustful relationship in the past between the government and ethnic minority groups. Another reason was that many of the minority ethnic people had never left their home area and forests. However, thanks to the mobilization policy of the party, they “actively joined in all military services of the people’s army to fight the air war to protect the socialist North, to protect the homeland and revolutionary base, and to go to the front.”Footnote 18 Although North Vietnam was successful in mobilizing people for the army and converting the land into a great rear base, there were many violations of official policy. A report from the same autonomous Northwest Region pointed out such situations: “The number of desertions was 193 (9 percent of mobilized people). There were six cases of adultery that were judged, but this trend was increasing. There were also some cases that gave birth, but did not register for benefits.”Footnote 19

In order to promote mobilization of ethnic groups to the front, the best method was a policy of taking care of a soldier’s relatives and family who remained at home (chính sách hậu phương quân đội). In general North Vietnam was successful in implementing this policy, but it was far from perfect, especially in the autonomous Northwest Region; the report suggested it was important “(1) to make sure that post was sent from the front to the homefront; (2) the victory news of soldiers and their units was very important for their families and home regions; (3) when a death notice arrives for a soldier, it is important to have their effects [to give to the family].”Footnote 20

In short, over the course of three years, 1965–7, of escalation of the air war against North Vietnam, Americans did not achieve their strategic objectives. North Vietnam was not destroyed, but instead was able to build up, develop itself, and supply the South. This reality led Secretary of Defense McNamara to admit: “All this led me to conclude that no amount of bombing of the North – short of genocidal destruction, which no one contemplated – could end the war.”Footnote 21

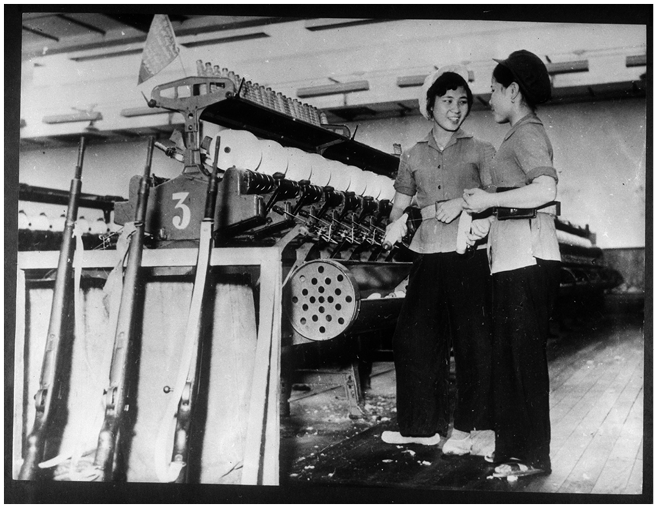

Figure 23.1 Women factory workers in Hanoi go about their jobs with their rifles nearby (August 14, 1965).

Conclusion

The Tet Offensive in 1968 was a turning point in the war, and put an end to the Johnson presidency with his limited warfare strategy. Under pressure from both Congress and the American people, President Richard Nixon planned a new strategy, “Vietnamization,” to end the war with peace and honor for Americans. According to DRVN president Hồ Chí Minh, Vietnamization was a continuation of the war by other means: Vietnamese fighting Vietnamese using American power. At the beginning of 1969, on the occasion of Tet, Hồ Chí Minh sent New Year wishes: “To fight so that the Americans quit; to fight so that the [South Vietnamese] puppets fall” (đánh cho Mỹ cút, đánh cho ngụy nhào). In order to do this, North Vietnam had to rebuild its economy, honor its duties and commitments to the South, and strengthen its own military forces for the next step of the war.

During 1965–8, with more than 100,000 bombing sorties and more than 1 million tons of bombs and missiles dropped, the American air war heavily damaged the North’s economy. In this context, on September 2, 1969, President Hồ Chí Minh died. In his Testament, Hồ Chí Minh expressed: “My ultimate wish is that our whole Party and all our people, closely joining their efforts, build a peaceful, unified, independent, democratic, and prosperous Vietnam and make a worthy contribution to the world revolution.”Footnote 22 On this occasion, North Vietnam was carrying out a series of political campaigns to learn and to follow Hồ Chí Minh’s Testament. On February 3, 1979, First Secretary Lê Duẩn published his work, “Under the Glorious Flag of the Party” (Dưới lá cờ vẻ vang của Đảng), to summarize the most important experiences of the leadership of the party over the previous four decades and to appeal to all party members and all people to forge ahead in the cause of revolution.

Hồ Chí Minh’s parting words and Lê Duẩn’s exhortations held more urgency as the North Vietnamese homefront suffered setbacks in the post–Tet Offensive war. For instance, the DRVN needed to set its priority on agricultural production because yields were declining: from 5.4 million tons in 1967 to 4.6 million tons in 1968. While the major cause of the agricultural setbacks was the US bombing under Operation Rolling Thunder, mismanagement also plagued the cooperatives. Following the suspension of bombing, poor management was the main cause of cooperatives’ low income. A report from the Northwestern Region underlined the North’s socialist model during the Vietnam War: “In general, the management of cooperatives had a lot of weaknesses: on average there were only between four to six working hours per day, and the value of each working hour was so low (in 1964 a working day cost 0.77 VND [dong], but in 1970 the same working day was valued at only 0.43 VND) that cooperative peasants did not work enthusiastically.”Footnote 23

In short, during the Vietnam War, North Vietnam carried out two parallel tasks with equal emphasis: building socialism and supplying the South. These two tasks were closely interrelated. Without building socialism, there would of course be nothing to supply the South with. And without supplying the South the construction of socialism would be impossible.

More than that, between 1965 and 1968 North Vietnam faced being destroyed by the air and naval war launched by US forces, but kept its footing amid bombings and death. North Vietnam not only successfully built socialism, but it also fulfilled the task of supplying the South thanks to the nationalism and sacrifice of millions of people. In his “Lessons of Vietnam,” McNamara recognized one of the most important reasons for the US failure in Vietnam: “We underestimated the power of nationalism to motivate a people (in this case, the North Vietnamese and Vietcong) to fight and die for their beliefs and values.”Footnote 24