Sources

Given the paucity of sources for our subject, the scholarly focus has been mainly on the few sources themselves. These can be roughly divided into the histories and the ‘military’ books, in Western literature described as the classical treatises on the art of war.

The Histories

The Spring and Autumn period is named after an eponymous chronicle that spans the first part of the Eastern Zhou dynasty. The Spring and Autumn Annals, covering the period from 771 to 481 bc, was written in the state or fief of Lu, in modern Shandong province. It is an extremely terse listing of events from the perspective of the Lu court. A later work, the Zuozhuan, traditionally understood as a commentary or explanation of the Spring and Autumn Annals, provides much greater detail, but is also a more literary or even fictional account of the political and military events of the period. The Zuozhuan also became a canonical history, making its narrative of battles and strategy extremely influential.

Like the Zuozhuan, the narrative of the Strategies of the Warring States, which covers the following period from the end of the fifth to the third centuries bc, but was written after this, is obviously an idealised, literary account of the centuries-long struggle for power leading to Qin’s conquest of the other six major states.

The main narrative of the founding of the Qin and Han empires, as well as the construction of the category of ‘militarist bingjia’, which included Sunzi, Wuzi and Sun Bin, comes from Sima Qian’s Records of the Historian (Shiji). The military books section of The History of the Han Dynasty provides a final gloss on the Han construction of strategy. This approach is relatively concise, though in no way a comprehensive survey of the actual strategies applied over 400 years of Han dynasty history. The Records of the Historian was begun by Sima Tan (c. 165–110 bc) and finished by his son, Sima Qian (c. 145–c. 86 bc), to whom the work is usually attributed.

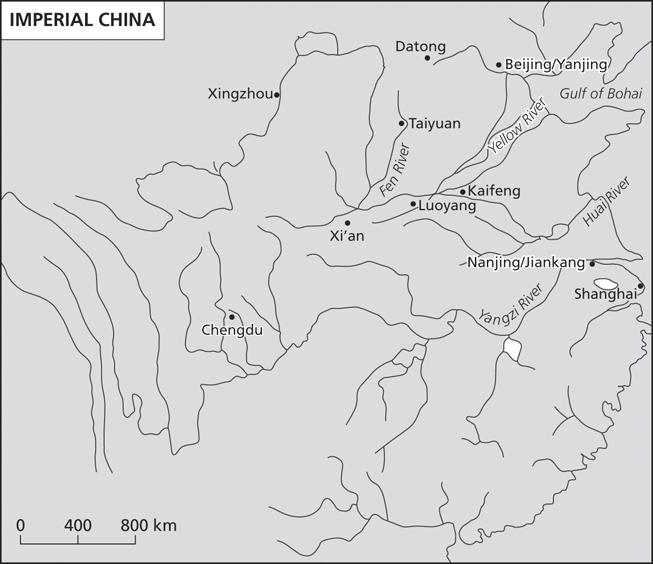

Map 1.1 Chinese strategies to ad 180

The Classical Treatises on the Art of War

Sima Qian’s description of pre-Han history created the category of ‘militarist’, consisting of Sunzi, Wuzi and Sun Bin. The Warring States period was the golden age of Chinese philosophy, when most of the foundational thinkers lived and taught. It was also when many canonical works, like the Analects of Master Kong (Confucius) and the Art of War of Master Sun (Sunzi), began to be written down. Master Kong, a Spring and Autumn figure, was mostly concerned to downplay the importance of warfare, a position those Ruists (Confucians) who claimed to follow him also maintained. One of those followers, Master Xun (c. 310–c. 220 bc), took direct issue with Master Sun and Master Wu (Wu Qi). When the Lord of Linwu and Master Xun were debating military policy in front of the King of Zhao, Linwu first asserted that the key to warfare was, ‘Above, utilize the most seasonable times of heaven; below, take advantage of the most profitable aspects of the earth. Observe the movements of your enemy, set out after he does, but get there before him.’ Master Xun rejected this, arguing that unifying the people of a state behind a ruler was the most important basis of warfare.Footnote 1

Lord Linwu responded,

In using arms, one should place the highest value upon advantageous circumstances, and should move by stealth and deception. He who is good at using arms moves suddenly and secretly, and no one knows from whence he comes. Sun Wu and Wu Qi employed this method and there was no one in the world who could stand up against them. Why is it necessary to win the support of the people?Footnote 2

Master Xun’s extended rejoinder makes a critical distinction between strategy for an ordinary or even a bad ruler, and strategy for a true king. He backhandedly admits that it is possible for a state like Qin to emphasise warfare and terrorise its people into success in battle, but he insists that stratagems, advantageous circumstances and deception would not be effective against the troops of a benevolent ruler.Footnote 3 Rather than arguing against Master Sun and Master Wu, Master Xun might simply have pointed out that both of those military writers did, in fact, advocate for unifying the population behind a moral general or ruler. Sima Qian, for example, would later attribute to Master Wu the saying that strength ‘lies in virtue, not in strategic places’.Footnote 4 Master Xun chose instead to set them up as straw men in order to urge the king to become a benevolent ruler.

Master Xun also had to respond to his own student, Li Si, who went to work for Qin and ultimately became prime minister to the First Emperor. He argues that the fact that Qin has been winning for four generations is not an indication of sound, long-term strategy, because harsh rule that runs contrary to ritual will fail in the end: ‘What proceeds by the way of ritual will advance; what proceeds by any other way will end in failure.’Footnote 5 Master Xun’s discussion of military affairs is therefore an early example of the Ruist use of military texts and military matters as a foil for arguments in favour of morality. While the argument for morality and benevolence as the best strategy for a ruler is consistent with the Zuozhuan and other Ruist thinkers, it seems (and likely seemed at the time to rulers) unconvincing on a pragmatic level.

Master Xun’s arguments in favour of morality and benevolence were particularly difficult to advance while the Qin kingdom had been successfully prosecuting a systematic strategy of conquest for ‘four generations’. The Qin government was strongly associated with a school of thought known in the West as ‘Legalism’. Legalism focused government policy on instituting and carrying out a strict system of laws that centralised power in the ruler, and rewarded agricultural productivity and success in war. Curiously, two of Master Xun’s students, Li Si and Master Han Fei, were later seen as Legalists, rather than as Ruists; Master Sun’s Art of War and Master Wu’s Art of War, on the other hand, were consonant with Ruists in several areas (though by no means all). For Master Xun and Ruists, morality and benevolence were the be all and end all of strategy, since they were both idealistically and pragmatically the only way to establish stable political authority.

The Strategies of the Warring States presents a considerably less idealistic view of strategy and how to achieve power. A long book with an unknown author (or, more likely, authors), The Strategies focuses on diplomacy and political manoeuvring, and is based in the complex history of the continuous struggles in the centuries before the Qin unification of China. The narrative is based upon a compilation of anecdotes describing interactions between rulers, statesmen and aristocrats, few if any of which can be corroborated independently in other sources. (It is currently understood to be a handbook of rhetoric for officials rather than a record of events.) Military events form a backdrop to diplomatic and political manoeuvring, much of which takes place within the courts of the various states. Rulers spend as much of their time trying to decide which minister to trust as they do which policy to pursue, while ministers and generals navigate between multiple courts, rulers, generals and ministers. Slander against one minister or general or another is a constant problem, undermining the loyal and competent, while advancing treacherous power seekers. The individual pursuit of power within a court has critical effects on the fate of states, while family conflicts between the ruling families, as well as among the other elites, continually disrupt diplomacy and policy making.

Given that the audience for the Strategies was ministers and officials at imperial, royal or aristocratic courts, it was an extremely pragmatic strategic manual. The Strategies provides example after example of the sorts of policy struggle that take place in a highly politicised environment with high stakes. Success led to power, status and wealth, and failure to disgrace, poverty and death.

In the Han period, the question of strategies concerning border problems and their relation to internal concerns is thoroughly debated in the Discourses on Salt and Iron (Yantielun). A work full of practical strategic discussions, it failed to have any impact on strategic thought or policy making.

The next summation of military books, listed under militarists, came in ad 111 in the bibliographic section of The History of the Han Dynasty. The fifty-three writers and 790 chapters of material in the ‘Militarist’ section of the bibliography are divided into four sections: ‘Military Power and Planning’ (兵權謀), ‘Military Form and Position’ (兵形勢), ‘Yin Yang’ (陰陽) and ‘Artful Military Skills’ (兵技巧). Some military works were placed in other sections of the bibliography – a Taigong in 237 chapters, including eighty-one chapters of plans and eighty-five chapters on war or soldiers, was in the Daoist section, along with a Sunzi in sixteen chapters, though this might be a different Master Sun and not a book on war.

Critically, Ban Gu, the compiler of The History of the Han Dynasty, inserts a quote from Master Kong in the description of the military books. This began a very intentional process of bringing abstract works on the military into Ruist ideology. Where Master Xun, as a good Ruist, objected to Sunzi as a false strategist, Ban Gu invoked Master Kong’s statement that the people needed to be trained before being used in war. The bibliography section of The History of the Han Dynasty does not include a work by Sun Bin (unless it is one of the Master Sun texts, but not specifically indicated as such), but does have Sunzi and Wuzi. The ambiguity of many of the titles, coupled with most of them no longer being extant, makes a clear determination of what was and what was not important in the category of military works impossible. It is apparent, however, that this was a very broad group of books that was not defined as ‘the art of war’ (bingfa). The usual category in the Han and subsequent imperial bibliographies was ‘military books’ (bingshu). Presumably, though this must remain speculative, this was because only a few military works or books on strategy had bingfa in their titles so the term could not define a category.

Confusing Categories

Some of the narratives of the past came to be seen as ‘classics’, and some as ‘histories’, but all of these early works became fundamental parts of an educated man’s knowledge. Unlike works of military thought like Sunzi’s Art of War, these were not considered specialised works, and were not looked down upon because of their association with war. Educated Chinese statesmen were not naive in their aversion to books on war, and they recognised that war and the military were important for their states, but they were more concerned that a ruler would focus on war too much rather than too little. Their problem was not a ruler reluctant to fight, but one who preferred fighting to ruling, or refused to think carefully about when and how to fight. Those concerns were amply reflected in the historical accounts, which repeatedly showed the dangers of careless involvement in war.

Setting aside the very small number of extant military texts, we end up with an account of strategy based on histories and some histories classed as classics. Chinese rulers, statesmen or generals looking for strategic wisdom relied upon histories rather than specialised strategic works. The books most often read and referred to in China with respect to strategy were chosen not only because they offered direct answers to pressing strategic questions, but also because they asserted the primacy of certain cultural norms. Those norms, which grew out of the Ruist political tradition, were in considerable tension with narrowly focused military works like the Sunzi during the Warring States period.

The Warring States period’s ideology was itself a sharp break from the aristocratic ethos of the Spring and Autumn period, when war was repurposed to serve the state rather than to demonstrate aristocratic status. Earlier texts, or those claiming to be early, were interpreted through Ruist eyes and used to stress the importance of morality over stratagems or even planning. Master Xun argued that the immediate value of strategy was outweighed by the longer-term advantages gained by morality.

Later in the Han dynasty the general category of military books became less suspect in Ruist eyes, or at least in the eyes of some Ruists. The truly operative strategic texts for literate officials remained, however, core histories like the Zuozhuan, the Strategies of the Warring States, the Records of the Historian, and Ruist thinkers like Master Xun. That reliance on military history would later reappear in the post-Han dynasty period when commentators sought to explain passages in Sunzi’s Art of War.

In this respect, China was no different to anywhere else; to the extent that people learned strategy from books; it was derived from historical narratives of battles and wars, along with the events that preceded and followed them.

The Contenders

The 700 years covered in this chapter saw both wars among Chinese polities and wars with ‘foreign’ entities. The Warring States period was just that – a period in which Chinese polities fought among themselves, culminating in the success of one, the Qin, defeating and absorbing the other six major states, Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Zhao and Wei.

In the immediate collapse of the Qin, ambitious men arose within the empire’s territory and gathered armies to fight over the ruins. Sima Qian presents the struggle for power culminating in a contest between Xiang Yu (c. 232–202 bc), an aristocrat from the former state of Chu, and Liu Bang (256–195 bc), a commoner who had served as a low-level Qin officer. Liu became the first emperor of the Han dynasty, and was posthumously known as Han Gaozu (r. 202–195 bc). Subsequent Han emperors varied in their foreign policies, in response to foreign threats and their personal inclinations. Han Wudi was the most expansionist emperor, for example, and Han Wendi one of the least.

But then there were also attacks from without on the Chinese-populated lands by the peoples from the steppes. The main threat until the first century ad came from the Xiongnu, though other steppe groups also caused problems.

Causes of War

The Warring States period saw war mainly among seven Chinese principalities with Qin step by step conquering of the other states. The basic question was whether the other six states could unite together to defeat the Qin, fight individually and likely lose, or submit to Qin. Unity required each ruler to overcome their personal feuds with the other rulers, thus putting the interests of their states ahead of their own feelings. Perhaps not surprisingly, and despite the efforts of the great diplomat Su Qin, unity could only be achieved briefly before collapsing.

Without a central court, officials and generals were faced with difficult questions of loyalty versus survival. It was not clear that a man owed loyalty to a ruler who mistreated him, or did not properly value him. Of course, that made it difficult for a ruler to trust the men beneath him, who might decide or be misled into believing that he distrusted them, becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Because diplomacy and politicking are stressed, campaign and military strategies usually involve non-military means for achieving power goals. Generals or officials are subverted through clever insinuations, raising sieges, undermining plans and deflecting armies. There are no benevolent rulers or true kings immune to deception, or whose morality insulates them from military action and treachery.

From the point of view of contemporary and later Chinese authors, the success of imposing peace within China, among the Chinese polities, by uniting them into one empire, and thus domestic rule, and policing it well, were thus as important as the skill of using armed force to defeat other armies. Despotic governance could thus become a cause of insurrection or separatism, and thus of war.

Sima Qian’s narrative of the Qin founding generally supports Master Xun’s perspective on the Qin during the Warring States period: the Qin succeeded by applying harsh Legalist principles to grand strategy, organising society around war and agriculture, and pursuing conquest ruthlessly, but fell after only a few years because of that harsh rule. In this telling, the success and failure of the Qin were due to its particular use of Legalist policies, and that interpretation was largely accepted for the rest of Chinese history. More recent archaeology, however, has shown that Qin was not alone in militarising its state and applying harsh laws to maximise the power of its population.

In practice, the ideological shift required to create an all-encompassing empire was followed by a similarly revolutionary strategic change to maintaining that empire. Inter-state warfare was replaced by domestic rebellions and by defending the northern border from steppe powers. The strategy of an established dynasty aimed to maintain the status quo, but it was unclear whether border threats and rebellions were an acute or chronic problem. If rebellions were caused by misrule, then the strategy for preventing or suppressing them would be very different than if they were caused by occasional episodes of evildoers joining together to make trouble.

In the Han period, the predominant cause of war was incursions into the empire by peoples from the steppes, mainly the Xiongnu. In the Discourses on Salt and Iron, we find two sides arguing about the causes of these incursions. The critics of Han government strategy, the ‘Worthies and Literati’, believed that Han expansion caused a steppe reaction, and that a withdrawal from these forward positions and an end to forays into the steppe would remove this cause of war. Han government ministers, by contrast, believed that Han expansion either had nothing to do with barbarian incursions, or was a necessary response to barbarian incursions. Barbarians, by their nature, would always raid China. There was some truth to both sides, and absolutely no agreement. Both sides offered historical examples to support their policy claims, providing concrete evidence for the effects of war or diplomacy with the steppe barbarians.Footnote 6

Objectives (Ends)

There are two kinds of strategic goal in early Chinese historical accounts: the use of organised violence to achieve cultural aims and the use of organised violence to achieve political aims, functionally the extension or establishment of temporal authority over people and land. While there were occasions when the two areas overlapped, for the most part there was a general shift away from purely cultural aims toward exclusively political aims from the late Spring and Autumn period into the Warring States period. In his classic study of warfare in that time, Mark Edward Lewis argued that sanctioned violence went from being a cultural practice of the aristocracy to a political tool of state.Footnote 7 That change was also reflected in the text of the mythical Sunzi (or Sun Tzu), whose Art of War asserted that war should be waged for reasons of state rather than the whim of the ruler.

The Warring States period (475–221 bc) was brought to a close by the success of the Qin state’s relentless campaigns to create a unified empire. This not only required a new strategic goal, the complete destruction of any subsidiary political authority, but also created a new strategic reality in the form of an empire. Neither Sunzi nor any of the other Warring States strategists had anything to say about these problems. Yet creating a unified empire through conquest marked a sharp ideological break with past practice. Incremental advancements in territory or influence within the existing framework were no longer enough. A ruler would not aim to replace the hostile ruler of another state with a more amenable member of the same lineage; the government of other states had to be completely overthrown. As goals shifted, so too did strategy. The limited-war ideology that underpinned the strategy of pre-imperial works biased tactical and operational practices in a manner that no longer worked. The Qin waged war relentlessly and ruthlessly, a good example being the Battle of Changping in 260 bc, following which the Qin army reportedly slaughtered 450,000 men. Although the number is exaggerated, a mass killing did take place, contrary to any strategist’s advice, and ably served the Qin’s war aims at that time.

The Qin dynasty unified China under its rule and created the first true imperial government in 221 bc. Qin rule proved unstable, however, and barely survived for a few years after the death of the first emperor. In the wake of the Qin fall, there was a fundamental question whether the Qin empire would revert back to the kingdoms of the Warring States period, or the feudal domains of the Spring and Autumn period, or be re-established under another man claiming the new title ‘emperor’, huangdi, created by the Qin ruler. The Han dynasty that emerged from the wars after the Qin fall was initially something of a hybrid. A new emperor was established who theoretically ruled over an empire like that of the Qin, but the first Han emperor had been forced by the expectations of his supporters and family members to bestow fiefs and titles on his generals and imperial clansmen. He and his successors would spend generations fighting to re-create the centralised empire of the Qin.

Han Wudi (157–87 bc, r. 141–87 bc) came to the throne intent on expanding Han territory. To some extent this was an effort to defeat the steppe people who regularly invaded the Han empire. Steppe raiding served both material and political ends, obtaining resources for survival and luxury goods for successful leaders to distribute to their followers. These motives were not always fully understood by Chinese officials, to whom the raids seemed merely to be uncontrollable acts of barbarians.

As we have seen, the domestic critics of the Han government argued that the steppe peoples were reacting to Han expansionism; aiming for peace rather than expansion, the critics advocated for less provocative strategic deployment which would also allow a reduction of indirect taxation domestically (see below). By contrast, Han Wudi and his loyal government ministers put the strategic objective of expansion above peaceful coexistence, arguing that the latter was impossible.Footnote 8

The Available Means

Armies in the Spring and Autumn period were built around chariot-riding aristocrats accompanied by squads of infantrymen drafted from the farmer population. During the Warring States period, most of the aristocrats were replaced by professional officers, and the farmer-soldiers serving as infantry became the main force of the armies. Very little information remains concerning how these armies were raised or deployed in battle.

Until the Xiongnu attacks from the steppes, Han armies had relied heavily upon farmers rendering mandatory military service to make up the mass of soldiers. Once the Han dynasty was in place, Liu Bang, who would posthumously be known as Han Gaozu, spent much of his time putting down rebellions and consolidating power. While the problems of internal dissent remained a cause for concern, they gradually gave way in importance to military problems on the northern border. The growing threat of the Xiongnu presented very different strategic problems. It was extremely difficult to defend against fast-moving steppe cavalry when they raided into Han territory, and nearly impossible to attack the Xiongnu in the steppe. The need for a standing army to defend the border required soldiers serving for longer enlistments. Not only Han strategy but also the Han military itself needed to change.

Han Wudi’s aim of expanding Han territory was expensive to put into strategic practice. Han farmers had gradually been escaping the control of the central government by placing themselves or being forced to place themselves under the control of powerful lords, officials and families. In order to raise the money that could no longer be extracted from the farmers, Wudi turned to a set of monopolies on salt, iron and liquor. These indirect taxes succeeded in their goal of providing a new source of revenue that enabled Wudi to pursue his policies without confronting the powerholders undermining government authority. Functionally, this was a useful expedient that did not address the larger structural problem of the general loss of government control over land and labour. That loss of control would have serious long-term implications far beyond military strategy.

Han Wudi’s adoption of indirect taxes was a sharp break in political ideology, and opened up the possibility of a vast increase in central government power. This change was recognised almost immediately for two reasons. First, it removed economic and manpower restraints on the emperor, since he was no longer solely reliant upon the farming population for men and materials. This was, of course, why the expedients had been adopted in the first place, to get resources formerly available to the throne, but captured by powerful families. Second, an independent source of money increased the power of the emperor with respect to those prominent families contending with the government for control. Emperors could raise and maintain armies without drawing upon the agricultural population. These professional soldiers would be of higher quality and beholden only to the throne. Wudi also employed ministers from merchant backgrounds to carry out these policies, further irritating the existing elites who usually dominated the government bureaucracy.

After Han Wudi’s death, during the regency of his successor, Emperor Zhao (94–74 bc, r. 87–74 bc), the salt and iron monopolies and several related policies were criticised by ‘Worthies and Literati’ who sought to overturn them. It is not clear exactly who they were. They had enough political status to have their objections taken seriously, and to be brought together to debate with several government ministers. They were thus men of some standing, likely from powerful families with a pre-existing relationship with the court. Because the text that later provided an account of these debates, the Discourses on Salt and Iron, would be categorised as a Ruist work, and because of the sorts of arguments they made, the Worthies and Literati have usually been seen as Ruists objecting to essentially Legalist policies. Although it is implied in the Discourses that the Worthies won the debate, a reader would have to be partisan to their arguments, and hostile to those of the ministers, to come to that conclusion.

The arguments are framed around the connection between taxes, resources, government power, government responsibility and border defence. In other words, the Discourses describes a debate over grand strategy. The Worthies argued that the monopolies should be rescinded because they disturbed the people, taking something from the economy that would otherwise belong to the people. The ministers, by contrast, argued that the money was needed for border defence, and that, if uncontrolled, individuals would become rich enough to challenge the state. Which is better, enhanced state power or a limited state within limited borders?

Since it was a debate, there was no move to compromise and develop a policy cognisant of both sides’ stronger arguments. In part this was because, as arguments over grand strategy, the fundamental issues of economics, political power and social status far exceeded the specific disagreements over war or government revenue.

The Process of Strategic Prioritisation and the Application of Strategy

Most discussions of Chinese military history and Chinese strategy rely heavily, sometimes exclusively, on Sunzi’s Art of War, with the occasional inclusion of a few other works of strategy. There is, however, no evidence that Sunzi or any other abstract strategist, mythical or real, influenced the actual course of campaigns or battles.

Rulers made strategic decisions during conflicts, but the historic accounts focus on counsellors’ advice and the court debates.

Sunzi’s plea to wage war only in the rational pursuit of political or state interests is the very definition of strategy, but it is also an indication that rulers, officials and generals often acted irrationally, or, at least, not in the interests of the state. Even when they acted in the interests of the state, however defined, they did so without consulting abstract works of strategy like the Art of War. While literacy was common among government officials, and the contents of works on strategy were available orally or in rare written versions by the fourth century bc at the latest, most strategic decisions were made based upon the limited concrete information available to a given court or council of war. For those historical actors, strategy was not abstract, and the stakes were very high. What was subsequently known about their decisions and the outcomes of their decisions was passed down to later rulers, officials and generals through the lens of a limited number of histories. Those works of history, or perhaps more accurately narratives of the past, informed their readers about strategic decision making at court and on the battlefield.

Whether or not the accounts of battles and wars in the histories are truthful is hard to tell, and beside the point with respect to establishing the normative precepts of strategy. There is a general sense that the descriptions of the political relationships between states and the outcomes of battles are reliable, but that the details of planning, conversations, diplomatic manoeuvring and the courses of battles are, not surprisingly, much more suspect. There is no way to determine whether these accounts are merely cleaned-up versions of reality, or wholly fabricated. Battles are notoriously confusing events whose tactical details are hard to render coherent even when known. It may thus not be a great loss that battles in early Chinese texts are not presented with an unreliable gloss of precision. Much as we might want to know the exact strategic plans of the generals and the events of the battlefield, it is unlikely that most such accounts would be accurate.

The Spring and Autumn Period (771–476 bc)

Very little is known about the course of battles before the Spring and Autumn period, or the strategic deliberations of the participants, so I will begin in the Spring and Autumn period itself, relying on the narrative account of the Zuozhuan’s Five Great Battles, before turning to the Strategies of the Warring States (Zhanguoce) for the Warring States period.

The Zuozhuan tells us about Five Great Battles (the battles of Chengpu, 632 bc; Yao, 627 bc; Bi, 598 bc; An, 589 bc; and Yanling, 575 bc) to which a sixth battle, the Battle of Han, 645 bc, is sometimes added, making the Six Great Battles. These six battles are presented as coherent narratives of the causes leading up to the actual battle, the various debates and discussions of political and military matters, the selection of commanders, a brief description of the battle itself, and a fuller description of the aftermath. The tactical aspects of the battles are neglected in favour of vignettes describing the experiences of noteworthy individuals. The ethos described in the Zuozhuan is amoral: once engaged in battle, a general or commander must seize any opportunity that presents itself. The goal of fighting a battle is to win, rather than to have a ‘fair’ contest that confirms the aristocratic status of both sides regardless of outcome.

In the Zuozhuan, and the Annals, military operations are never divorced from internal and external political concerns, or larger strategic context. The battlefield is not a separate realm for generals, but one of several different fora in which states struggle for power. That struggle is waged within a cultural matrix that imposes costs on the players who violate its norms. From the histories, we get more insights into the deliberations that were taking place at the rulers’ courts than into the military operations or the tactics used on the battlefield. The greatest level of detail in the histories is usually presented for events at the courts of the various rulers, while battles are dealt with cursorily. What happened at those courts would have been better known to the sorts of literate men who might compile a historical account. The literary requirements of historical narratives emphasised dramatic stratagems rather than strategy, morality in general but particularly for a ruler, political manoeuvring, and the success of perceptive predictions.

Military narratives were driven by clashes of personality, and the success of rational strategy over emotionally driven actions. The usual structure for a war or political struggle is for a wise counsellor to admonish his ruler to treat his subjects well, be true to his word, follow correct ritual practice and act in good faith. The ruler who listens to his counsellor eventually succeeds, while the one who doesn’t is defeated. Morality is effectively grand strategy in these narratives, a practice for the ruler and his officials and generals that produces military success by establishing a solid foundation for power. Morality generates military power.

Although morality for rulers and elites is important, the Zuozhuan is clearly on the side of the newer culture of war that has overtaken earlier aristocratic manners. The cultural practices of the elites that treated war as a gentleman’s game wherein he proved his status as an elite are shown to be counterproductive and foolish. Not only have the needs of the state overridden the performative needs of an individual gentleman, but also the culture has moved on. There is no longer anything admirable from the historian’s perspective in giving up a military advantage for the sake of manners.

These principles of strategy often appear to be in tension during actual events, and it is the responsibility of the various statesmen and advisers to debate which principles are, in fact, operative. Thus we see in the account of the Battle of Chengpu an instance of Duke Wen of Jin keeping his promise to requite a previous kindness, and give up a military advantage by withdrawing his army a three-day march, instead of attacking the Chu army to rescue the state of Song. His generals object to this on the ground of military expediency, claiming that the Chu army is about to collapse, but an official explains that the withdrawal will, in fact, be the most effective tactic. First of all, the Chu army is not ready to collapse. Second, Duke Wen must keep his earlier promise to pay back Chu if he is to show that he is on the side of correct ritual. Even though the point of the campaign was to protect Song, Duke Wen, given Chu’s earlier help when the duke was in exile, could not directly attack Chu to save Chu’s enemy, Song. By withdrawing, the duke showed that he was acting with ritual propriety, while still undermining Chu’s attack on Song.

Duke Wen was both acting correctly and executing an effective strategy. Indeed, the strategy was more effective, it was argued, because it was morally or ritually correct. The presence of the Jin army nearby, even three days away, forced Chu to raise the siege of Song. The only question was whether Song would simply withdraw, or initiate its own attack on the Jin army. If the Chu army attacked the Jin army after it had withdrawn, then it would be Chu violating ritual, absolving Duke Wen of blame. Good military strategy took into account the larger ritual framework of inter-state relations. By withdrawing a three-day march after meeting the Chu army, Duke Wen manoeuvred Chu into a strategic corner. He immediately seized a superior diplomatic position and presented Chu with the choice of military withdrawal or fighting at a disadvantage.

While the Chu ruler wisely chose military withdrawal, having realised that he had been outmanoeuvred, his commanding general defied his orders and brought on the battle of Chengpu. The defeat of Chu’s army at Chengpu is not presented in tactical detail, but it is used to emphasise the critical value for rulers of choosing good generals and listening to advice, and the accuracy of good portent interpretation. The Chu ruler was warned that he had chosen a bad general earlier in the account, and the predictions made by one official are ultimately shown to be accurate. Meanwhile, Duke Wen listened to his wise officials, and had his dreams correctly interpreted, so that he proceeded to victory. The only ambiguity in the account is whether the Chu ruler’s decision to take most of his troops with him in retreat when his general defied him and chose to fight was a good or bad choice. He could have lost more troops had he not angrily abandoned the general, or perhaps the general might have won with more men. This was also a refutation of Sunzi’s contention that, once in the field, there are commands from the ruler that a good general does not obey. At Chengpu, the general unwisely disobeyed his ruler’s better strategic judgement.

Many facets of the Battle of Chengpu are narrative demonstrations of Sunzi’s abstract discussion of strategy. A ruler and his general must be moral, or at least publicly moral. Choosing a good general is critical. A bad general can be manipulated into fighting at a disadvantage, and thus defeated. Duke Wen also waited several years before going on campaigns in order to internally unify his state, train his troops and make his subjects prosperous. More generally, Duke Wen had excellent intelligence concerning the state of the opposing army and the Chu leadership. He knew exactly whom he was fighting, and what their capabilities were.

There are also critical differences from Sunzi, which show that the Art of War describes a later period of warfare. Both Duke Wen and King Cheng, the Chu ruler, took the field with their armies. Although they used generals to command their armies, and were accompanied by officials who served in both civil and military capacities, rulers during the Spring and Autumn period went on campaign, and either took part in battles or were close by. Perhaps most significantly, the pure raison d’état of Sunzi is in some tension with personal and emotional reasons in the Zuozhuan. Attacking rulers who offended you is not frowned upon and, indeed, after the Battle of Chengpu, Duke Wen attacks a state that would not allow his army to pass through on the way to Song. Events like the Qin massacre of a reported 450,000 men after the Battle of Changping in 260 bc, which followed a prolonged siege, seems to have run counter to strategic writing, but was tremendously effective.

The Zuozhuan described war, politics and strategy as detailed events rather than dwelling on abstract analysis. To the extent that analysis and strategic principles are offered, they take the form of explanations of why specific policies or decisions are strategically correct or to be avoided. A reader is offered stratagems, responses to particular situations, instead of principles. In that sense, the Zuozhuan is a store of practical lessons on strategy at actual courts, dealing with rulers, officials and generals.

From the Warring States Period to the Beginning of a Unified Empire (475–206 bc)

The second half of the Eastern Zhou dynasty is usually called the Warring States period. Like the Spring and Autumn period, the Warring States period is named after a history, the Strategies of the Warring States (Zhanguoce), compiled during the following Han dynasty, and refers to the period from the early fifth to the third centuries bc. Different beginning and ending years are given by various authors, but it roughly encompasses the period from the end of the Spring and Autumn period to the Qin unification of China in 221 bc.

In the historical accounts, the military thinkers and generals Sun Bin and Master Wu are known and mentioned, but in a positive tone. For example, a general holding the town of Liao for the state of Yan against the army of Qi was induced to raise the siege after holding out for over a year by a carefully worded letter. Lu Zhonglian (or Lu Lian) praised the general’s accomplishment in holding out:

Now you have exhausted the people of Liao, and staved off the entire army of Qi for a whole year without relief. This is a feat worthy of Mo Di! You have eaten your soldiers’ companions and boiled their bones, yet still they do not mutiny. These are troops fit for Sun Bin or Wu Qi! These acts alone are enough to make you known throughout the length and breadth of the land.Footnote 9

The rest of the very long letter, which was shot into the town, is a tour de force of historical examples explaining why, given the current military situation across China, and the problems at the Yan court, the general would be better off personally, and Yan would be better off militarily, if he marched out and returned to the Yan court with his army intact.

More so than the Zuozhuan, the Strategies promotes a relentlessly rational approach to affairs. Political and military actors are always calculating what their interests are and how to achieve them, with little regard for real, as opposed to apparent, morality. This may have been because the military and political environment had deteriorated so badly by the fifth century that the earlier sense of aristocratic restraint no longer obtained. Where the struggle for power in the Spring and Autumn period at least seemed to take place within an established system that adhered to generally agreed values, usually referred to as ‘ritual’, the remaining seven states in the Warring States period were fighting for survival. There was a new drive not just to achieve dominance in a multi-state environment, but rather to overturn the existing order and directly rule everything. Consequently, war aims went from limited to total.

The Han Dynasty (206 bc–ad 220)

The Han conquest and return to an imperial state also created a new strategic reality. An established unified empire was a very different political and military entity than a state coexisting and competing with other peer or near-peer states. The absolute claim to power that drove the Qin conquest, and the Han conquest that followed it, posited an end to warfare following the establishment of a unified imperial dynasty. Sunzi, in contrast, assumed not only limited warfare, but also a continual state of hostilities. Even in the periods between actual campaigns and battles, the states of the Warring States period were still struggling for power. All that changed when there were no other legitimate states to fight. In theory, at least, the creation of the empire initiated a time of positive peace. One of the main Legalist justifications for investing all power in a single ruler who governed by strict regulation was to create a stable peace.

The Records of the Historian, like all the earlier Chinese histories, has very little to say concerning battle tactics and operations of the ambitious aristocrats who fought for predominance after the collapse of the Qin, confining its account to the political manoeuvring in and around battles, with brief mentions of the battles themselves. Battles were clearly important, but the politics dominating strategy were more important. As the contest culminated in the showdown between Xiang Yu from the former kingdom of Chu and the upstart Qin officer Liu Bang, the latter rose to power through competence and determination, but did not win every battle he fought. Xiang Yu, by contrast, who had every advantage of station and mental and physical attributes, won every battle but ultimately lost to Liu Bang.

Much of the narrative of Xiang Yu is an indictment of a supremely talented aristocrat who could not overcome his own ego to pursue an effective strategy for long-term success. Xiang Yu was ambivalent about reconstituting a new empire to succeed the Qin, and chose, instead, to rule as hegemon, enfeoffing Liu Bang as King of the Han in poor Sichuan. It should have been obvious that this was bad strategy since it neither eliminated nor sated the ambitious Liu Bang. Liu Bang soon broke out of his peripheral posting, outmanoeuvred and defeated Xiang Yu at the Battle of Gaixia, and founded the Han dynasty. Sima Qian was at pains to show that Liu Bang, despite many negative aspects of his personality, stuck to his goal of establishing a new empire and becoming emperor.

Sima Qian’s portrayal of Liu Bang demonstrates a specific model of leadership for an emperor. Where Xiang Yu was an extraordinary individual who knew he was extraordinary, and relied solely on his own capabilities, Liu Bang was careful to gain the services of capable generals, officials and advisers, and to use them effectively. Liu Bang listened to his advisers even when they disagreed with him, and gave credit to and rewarded his generals when they succeeded. In the simplest terms, Xiang Yu was a hero rather than a ruler, and Liu Bang a ruler rather than a hero. The world could only be settled by someone who subordinated his ego to a larger plan, and made use of talented men in his cause. Although Liu Bang had led armies and fought in combat, it was when he rose above the personal command of armies and fighting that he was able to carry out a larger strategy. For Sima Qian, Liu Bang’s actual military experience was not a necessary component to imperial legitimacy, or even desirable. Rulers were not required to be generals, nor was experience of the battlefield required for civilian strategic advisers. Military strategy was something decided at court and carried out by professional generals.

There were no good purely military options. Even if a Xiongnu force was defeated on a raid, much of the defeated force might still escape. Standing on the defensive behind fortifications ceded all the initiative to the Xiongnu, while incurring very high maintenance costs. Han infantry could not proceed very far into the steppe, and their logistic burden also slowed them down. The only solution was to mix diplomacy and war in order to placate some parts of the Xiongnu leadership, raise their costs of raiding and foment factional disputes. This was expensive, forcing the Han to spend money on both military preparations and pay-offs for the Xiongnu. Han princesses were sent as brides to keep the peace. As unpleasant and costly as this mix of practices was, it was somewhat effective. Eventually the combination of Han attacks and, probably more importantly, internal divisions and the rise of other steppe groups in the first century ad ended the Xiongnu as an existential threat to the Han empire.