Introduction

It has been established that suicidal behaviour is highly prevalent in individuals with schizophrenia. Compared to the healthy population, people with schizophrenia are at a 4.5-fold increased risk of dying from suicide [Reference Olfson, Stroup, Huang, Wall, Crystal and Gerhard1], with an estimated rates of 5.6% for completed suicide [Reference Jakhar, Beniwal, Bhatia and Deshpande2], 20.3% for suicidal attempts [Reference Álvarez, Guàrdia, González-Rodríguez, Betriu, Palao and Monreal3] and 34.5% for suicidal ideation [Reference Bai, Liu, Jiang, Zhang, Rao and Cheung4]. This risk is further heightened in the early stages of illness, with up to 40% of total suicides associated with schizophrenia occurring during the First Episode of Psychosis (FEP) [Reference Ventriglio, Gentile, Bonfitto, Stella, Mari and Steardo5]. This has given rise to increased clinical focus on individuals experiencing the prodromal stage of psychosis.

Clinicians have characterised this demographic as being at Ultra-High Risk for Psychosis (UHR). UHR individuals are identified by one or more of the following characteristics: (1) Attenuated Psychotic Symptoms (APS); sub-threshold positive psychotic symptoms during the past 12 months; (2) Brief Limited Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms (BLIPS) – frank psychotic symptoms for less than 1 week which resolve spontaneously; and (3) Genetic vulnerability (Trait) – meeting the criteria for Schizotypal Personality Disorder or having a first-degree relative with a psychotic disorder [Reference Yung and McGorry6].

However, there is a lacuna in the current literature surrounding suicidal behaviour among UHR youths. Most papers have focused on suicide in the general UHR population, with a 2014 meta-analysis establishing a lifetime prevalence of 66% for current suicidal ideation, 18% for lifetime suicide attempts, and 49% for lifetime self-harm behaviour [Reference Taylor, Hutton and Wood7]. Yet, youths and adolescents make up most of the UHR population, with only 15% of this demographic aged 25 and above [Reference Fusar-Poli, Borgwardt, Bechdolf, Addington, Riecher-Rössler and Schultze-Lutter8]. Furthermore, youth is an inherent risk factor for suicide in the schizophrenia population, with younger patients experiencing higher rates of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts than their older counterparts [Reference Olfson, Stroup, Huang, Wall, Crystal and Gerhard9]. This underscores the need for accurate characterisation of suicidal behaviour and ideation among the UHR youth to provide targeted support for this particularly vulnerable demographic.

The primary aim of this study is to synthesise the existing literature on the prevalence of suicidal ideation and behaviour in the adolescent and youth at Ultra-High Risk for Psychosis (UHR) and provide a meta-analysis on the prevalence of suicidal behaviour and self-harm when appropriate. The secondary aims include comparing the prevalence of suicidal behaviour between UHR and Non-UHR Criteria-fulfilling/Healthy Control (HC)/First Episode Psychosis (FEP) population, and systematically reviewing the risk factors and correlates of suicidal behaviour within the UHR adolescent and young adult population.

Methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted following the MOOSE (Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [Reference Stroup10]. (Supplementary Appendix 1) The protocol was registered on PROSPERO: CRD42024583255.) The databases PsycINFO, PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and Scopus were searched from inception up to 31 July 2024. Keywords and controlled vocabulary used consisted of: (“Ultra-High Risk” OR “At Risk Mental State” OR “Clinical High Risk”) AND (“Schizophrenia” OR “Psychosis”) AND (“Self-Harm” OR “Suicide” OR “NSSI”) AND (“Adolescent” OR “Youth”). (Supplementary Appendix 2 – Search strategy. Supplementary Appendix 3 – PICO table.) Title/abstract and full-text screening were conducted by three independent reviewers, with any conflicts resolved by a fourth reviewer. Conference abstracts and theses that were identified through systematic searching were also followed up with the original authors for the full text, if available. Hand-searching was also undertaken within eligible articles to identify suitable articles. Fifteen eligible articles were eventually identified and presented in a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart outlining the study selection process.

The inclusion criteria for articles were as follows: studies published in English; participants aged < =25 years; participants classified as UHR according to a validated tool, for example, the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS) [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly and Dell’Olio11], the Structured Interview for Psychosis-Risk Symptoms (SIPS) [Reference Miller, McGlashan, Rosen, Cadenhead, Ventura and McFarlane12], and Prodromal Screen for Psychosis (PROD) [Reference Heinimaa, Salokangas, Plathin M, Huttunen and Ilonen13]; and studies that provided quantitative data on suicidal behaviour and self-harm. Articles that were not written in English, included participants aged over 25, included participants with an established diagnosis of schizophrenia or intellectual disability, history of frank psychotic episodes and extended use of antipsychotics were excluded. The cut-off age of 25 was selected to capture health outcomes of transitional aged youths – a demographic at increased risk of mental illness due to the changes in social roles, peer support, and education that accompany adulthood [Reference Martel14].

In this study, suicidal ideation was defined as the act of thinking about or formulating plans for suicide [Reference Nock, Borges, Bromet, Cha, Kessler and Lee15]. Suicidal attempts were defined as self-injurious behaviour done with at least the partial aim of ending one’s life [Reference Vijayakumar, Phillips, Silverman, Gunnell, Carli, Patel, Chisholm, Dua, Laxminarayan and Medina-Mora16]. Non-suicidal self-injury was defined as the intentional destruction of one’s own body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes that are not socially sanctioned [Reference Klonsky17]. The term suicidality was defined as the full spectrum of suicidal phenomena, from suicidal ideation to execution [Reference Keefner and Stenvig18]. However, it should be acknowledged that the term “suicidality” is controversial among suicidologists due to its lack of precision [Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner19] and will be used in this review only in the context of specific nomenclature (e.g., CAARMS [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly and Dell’Olio11], SIPS [Reference Miller, McGlashan, Rosen, Cadenhead, Ventura and McFarlane12]). It should also be highlighted that non-suicidal self-injury would not fall under the definition of suicidality [Reference Nock20].

Data extraction

Data extraction commenced on 15 September 2024. Three medical students (A.S.H., S.V., and M.G.) independently undertook data extraction of the predetermined relevant outcomes. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through discussion with a fourth reviewer (G.K.K.), an academic psychiatrist. The authors of one study [Reference Koren, Rothschild-Yakar, Lacoua, Brunstein-Klomek, Zelezniak and Parnas21] were contacted for information regarding their demographic breakdown that was missing in the original article, which was later obtained.

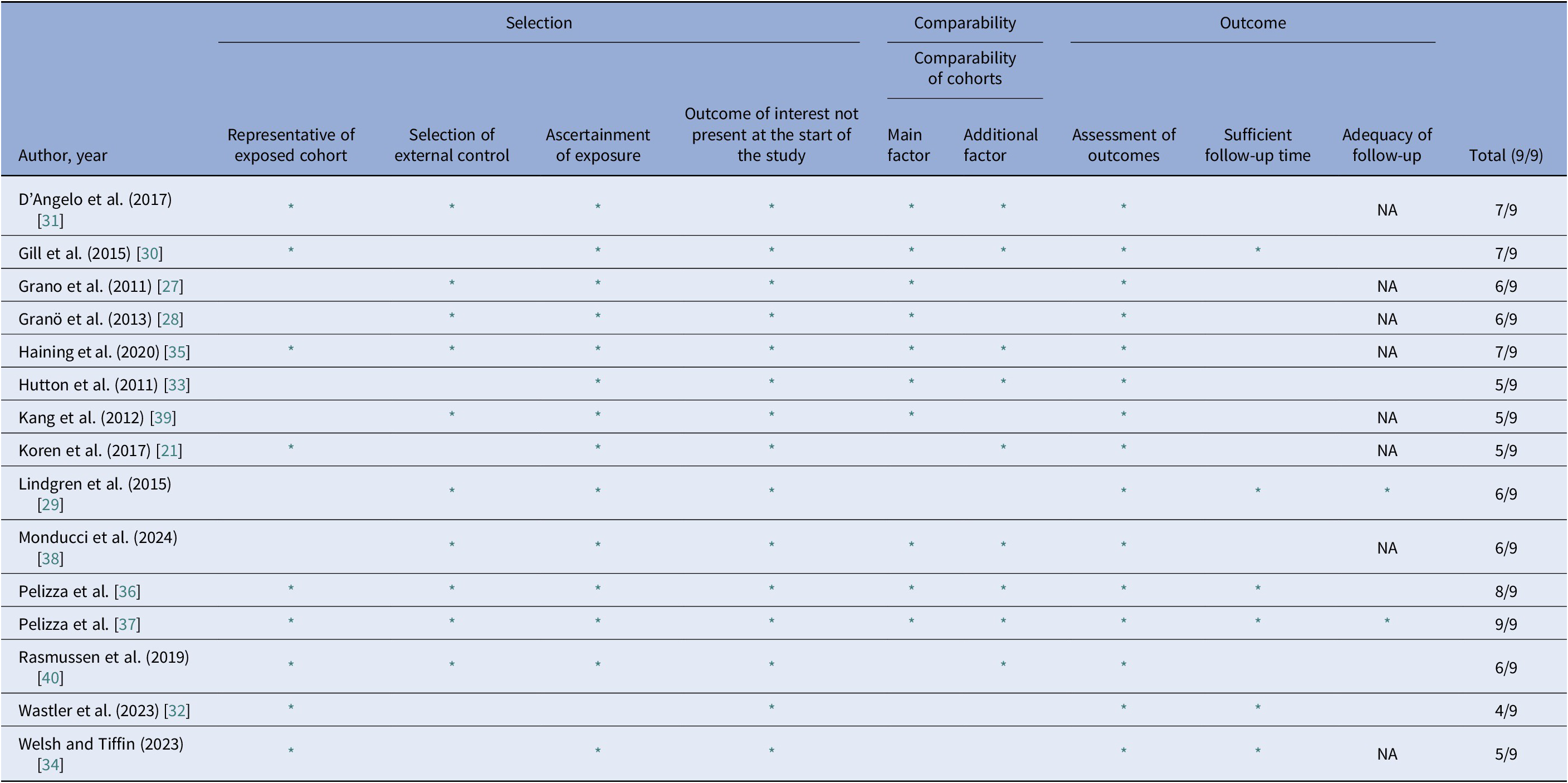

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the studies included was assessed independently by two authors using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [Reference Stang22] (Table 1). Studies were considered representative of the exposed cohort if participants were selected from national, state-wide, or regional cohorts. Sufficient follow-up was defined as 6 months or more with an attrition rate of less than 10%. The quality of the articles was classified based on the score obtained into one of the following three and ranked: High (7–9), Medium (5–6), and low (0–5). Among the included studies, 5 were considered high quality, while the remaining 10 studies scored 6 and below. The mean score of the articles was 6.1. However, it should be noted that more than half of the studies were considered cross-sectional and lost a point under the “adequacy of follow-up” criteria due to their study design. Hence, the NOS may underestimate the methodological quality of these studies.

Table 1. Newcastle-Ottawa scale

* indicates met criteria. NA indicates cross-sectional study design.

A key problem in the methodology not measured by the NOS was the measurement of suicidal behaviour and self-harm. Suicidal behaviour and self-harm were often determined with single self-report items such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [Reference Beck, Steer and Brown23] or continuous subscales measures of suicidality such as the CAARM [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly and Dell’Olio11] or SIPS [Reference Miller, McGlashan, Rosen, Cadenhead, Ventura and McFarlane12]. These scales were developed as one-off measurements and may provide a limited coverage of suicidal behaviour [Reference Borschmann, Hogg, Phillips and Moran24]. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the BDI-II has been validated as a strong predictor of the likelihood of patients dying by suicide [Reference Green, Brown, Jager-Hyman, Cha, Steer and Beck25]. Another limitation in the methodology of included studies is the lack of blinding of interviewers to the participants’ UHR status. This may have introduced bias where pre-conceived notions of UHR individuals influenced interviewer perception [Reference Hiebert and Nordin26]. Lastly, confounding variables were not consistently applied in studies that analysed correlates of self-harm and suicide. This may lead to biased group comparisons.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis of prevalence was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of lifetime suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, and non-suicidal self-injury when three or more studies were available. A random-effects model with inverse variance weighting was applied to account for between-study heterogeneity, with proportions logit-transformed for variance stabilisation and back-transformed for interpretability. Results are presented with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) and assessed for heterogeneity using the I 2 statistic. Analyses were performed in RStudio Version 2023.09.1, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. For group comparisons on suicidal behaviour and ideation between UHR and other demographics, the odds ratio was calculated using MedCalc-based population data from the dataset.

Results

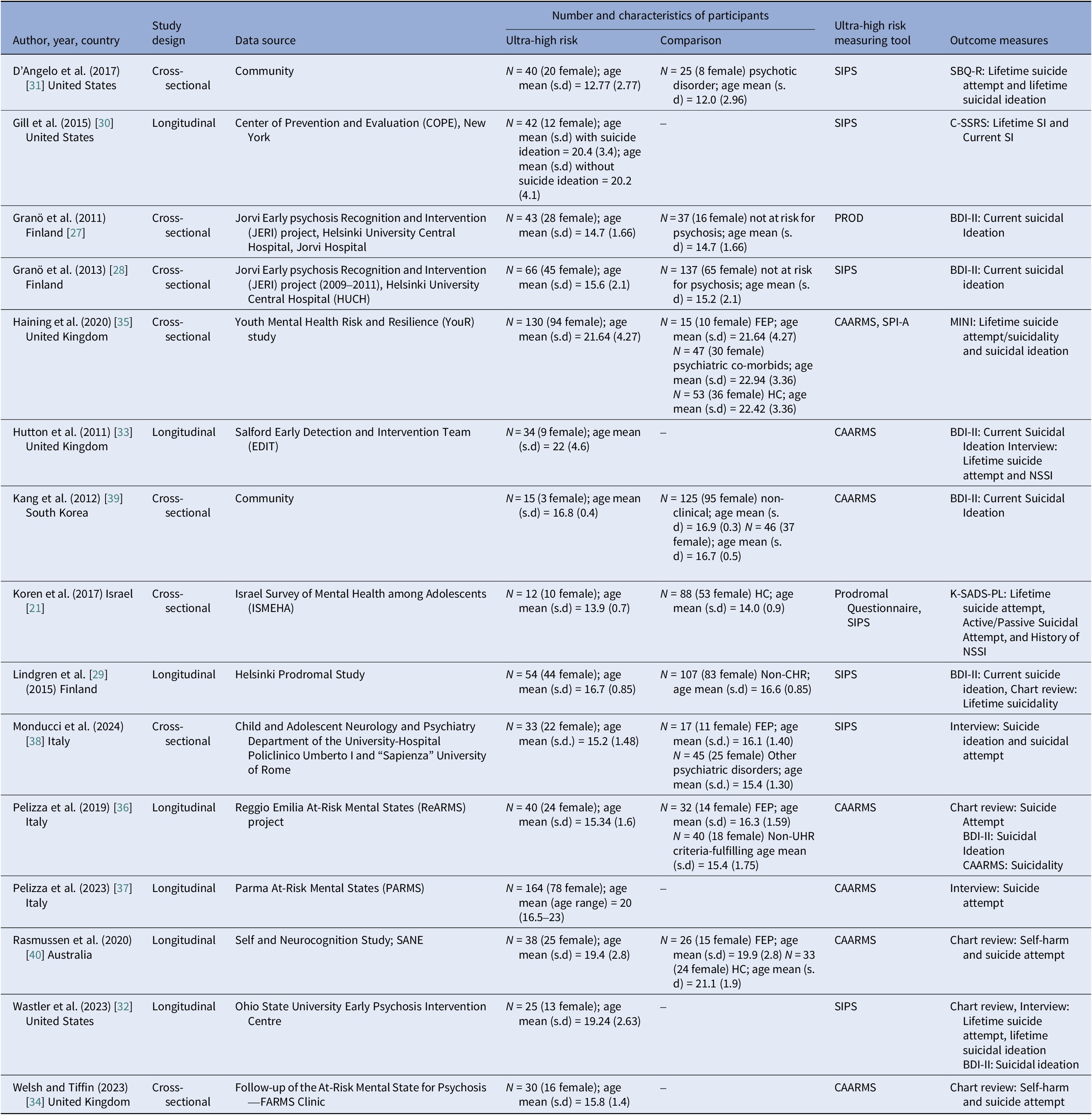

Of the 15 studies selected, seven were longitudinal, while eight were cross-sectional. (Table 2) (Supplementary Appendix 4 – full list of studies included) Three studies were conducted in Finland [Reference Granö, Karjalainen, Suominen and Roine27–Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29], the US [Reference Gill, Quintero, Poe, Moreira, Brucato and Corcoran30–Reference Wastler, Cowan, Hamilton, Lundin, Manges and Moe32], the UK [Reference Hutton, Bowe, Parker and Ford33–Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35], and Italy [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36–Reference Monducci, Mammarella, Maffucci, Colaiori, Cox and Cesario38] while one study each was conducted in South Korea [Reference Kang, Park, Yang, Oh, Shim and Chung39], Israel [Reference Koren, Rothschild-Yakar, Lacoua, Brunstein-Klomek, Zelezniak and Parnas21], and Australia [Reference Rasmussen, Reich, Lavoie, Li, Hartmann and McHugh40]. The Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State assessment tool (CAARMS) [Reference Yung, Yuen, McGorry, Phillips, Kelly and Dell’Olio11] was used most frequently by the studies to evaluate the presence of Ultra-High Risk status in the subjects. Other assessment tools used included the Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms (SIPS) [Reference Miller, McGlashan, Rosen, Cadenhead, Ventura and McFarlane41], Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms—Version A (SPI-A) [Reference Schultze-Lutter, Ruhrmann, Picker and Klosterkötter42], and the Prodromal Questionnaire [Reference Loewy, Pearson, Vinogradov, Bearden and Cannon43].

Table 2. List of included studies

CAARMS, Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental State; SIPS, Structure Interview for Psychotic-risk Symptoms; SPI-A, Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument-Adult; BDI-II, Beck’s Depression Index-II, K-SADS, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

The results for lifetime suicidal attempts, current (2 week) suicidal ideation, lifetime suicidal ideation, and lifetime non-suicidal self-injury are displayed in figure plots. Sensitivity analyses were used to further explore the role of individual studies in contributing to heterogeneity.

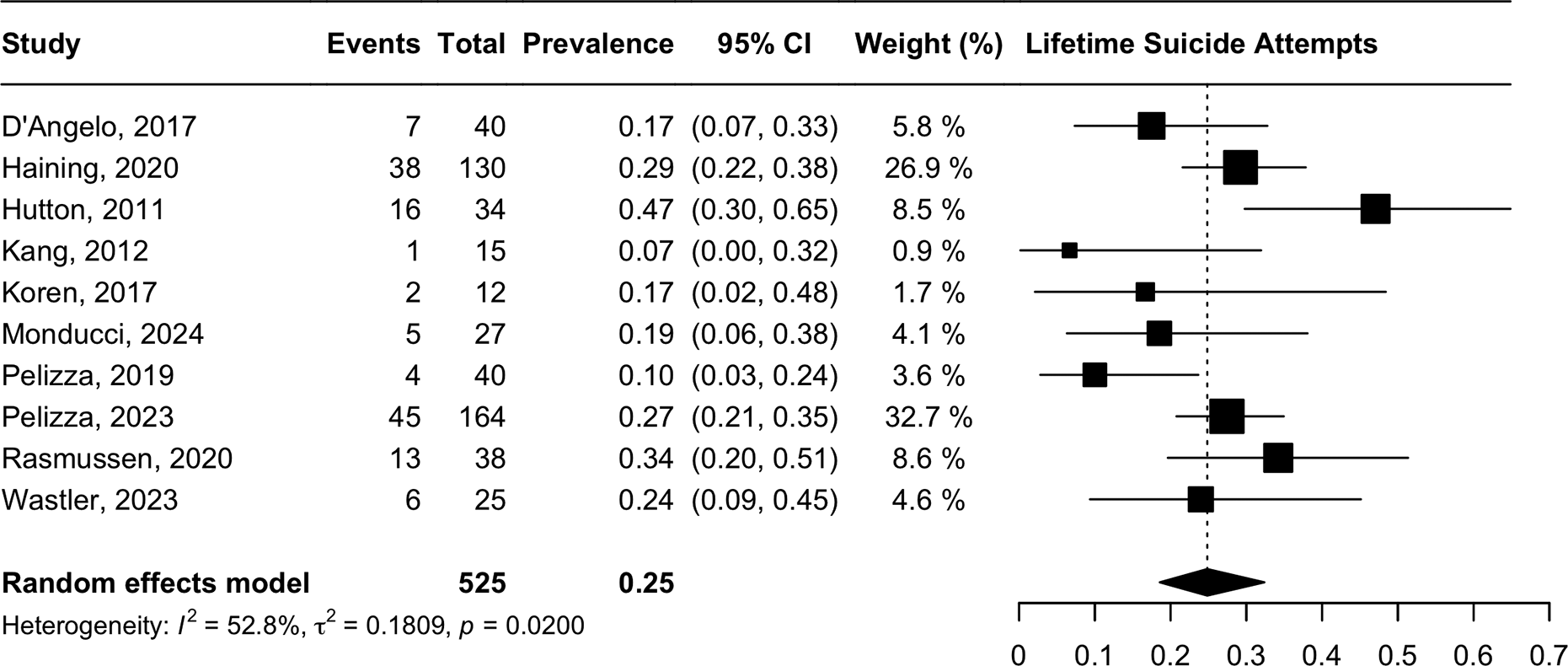

Suicidal attempt

The prevalence of lifetime suicide attempts was 24.84% (95% CI 18.6–32.4, N = 525, I 2 = 52.8%, p = 0.02), with moderate heterogeneity. (Figure 2.) For past suicidal attempts, one study reported a prevalence of 2.3% (n = 3/130) within the past 1 month [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35]. Two studies reported longitudinal data on new suicide attempts from the follow-up period. Pelizza et al. [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36] reported that 6.25% (n = 2/32) and 10.5% (n = 2/19) of their cohort had attempted suicide at the 1-year and 2-year follow-up point [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36]. Pelizza et al. [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37] reported that 7.3% (n = 12/164) and 7.9% (n = 13/164) of their sample attempted suicide at the 1-year and 2-year follow-up period [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37]. However, this figure may be over-represented as some members of the original cohort were unable to be reassessed at the 1- or 2-year mark, as they had withdrawn from the study or were lost to follow-up.

Figure 2. Lifetime suicidal attempt.

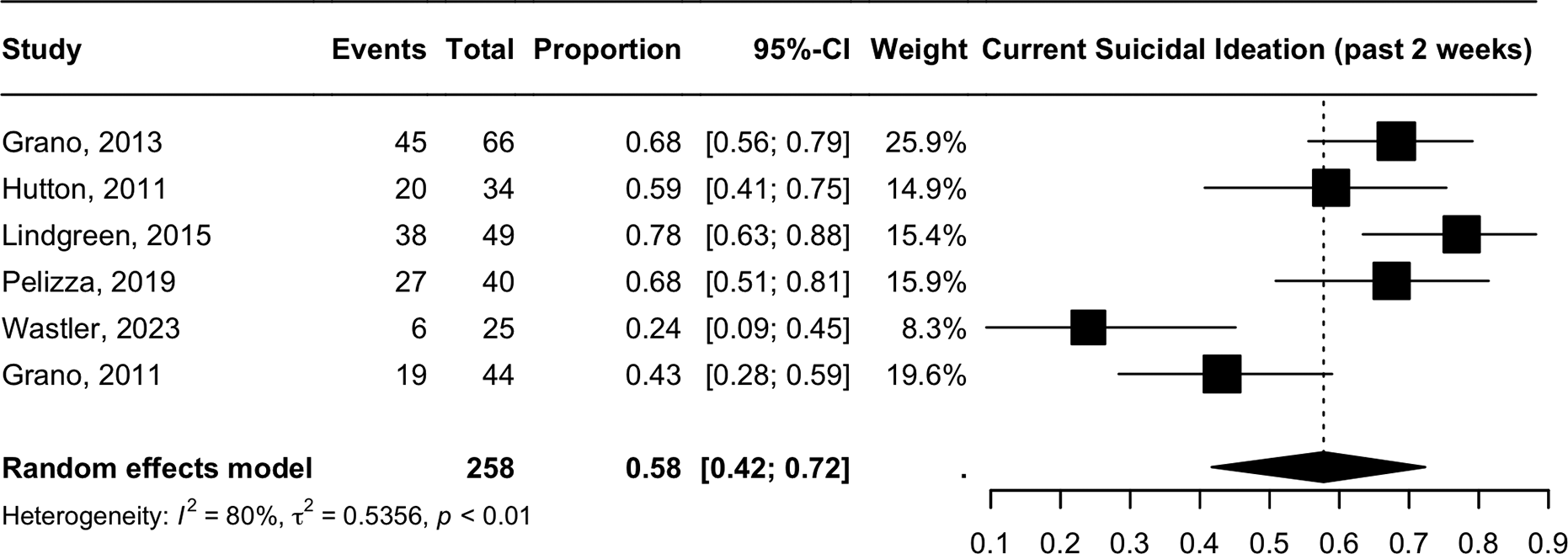

Current suicidal ideation (2 weeks)

Recent (2 week) suicidal ideation had a prevalence of 57.75% (95% CI 41.70–72.31, n = 58, I 2 = 80%, p = <0.01), with significant heterogeneity. (Figure 3) All studies in the meta-analysis dichotomized the presence and absence of suicidal ideation using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). The degree of heterogeneity is attributable to the low prevalence reported in Granö et al. [Reference Granö, Karjalainen, Suominen and Roine27] (43.18%, n = 44) and Wastler et al. [Reference Wastler, Cowan, Hamilton, Lundin, Manges and Moe32] (24.00%, n = 25). Removal of the following studies resulted in a larger prevalence estimate of 68.43% (95% CI 61.38–74.73) with minor levels of heterogeneity (I = 9.2%, p = 0.35).

Figure 3. Current suicidal ideation (2 weeks).

For the prevalence of SI in the past 1 month, Haining et al. [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35] reported the prevalence at 34.6% (n = 45/130) [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35]. Gill et al. [Reference Gill, Quintero, Poe, Moreira, Brucato and Corcoran30] reported the prevalence of suicidal ideation for the past 6 months at 42.9% (n = 18/42) [Reference Gill, Quintero, Poe, Moreira, Brucato and Corcoran30].

Suicidal ideation (lifetime)

The meta-analysis of lifetime suicidal ideation indicated a prevalence of 56.34% (95% CI 42.0–72.0, n = 164, I 2 = 61%, p = 0.04) with moderate heterogeneity. (Figure 4) The degree of heterogeneity is attributable to the high rates of NSSI reported in Gill et al. [Reference Gill, Quintero, Poe, Moreira, Brucato and Corcoran30] (76.77%, n = 30) [Reference Gill, Quintero, Poe, Moreira, Brucato and Corcoran30]. Excluding this study gave a slightly lower prevalence of 50.49% (95% CI 41.97–58.99) but with lower heterogeneity (I 2 = 22%, p = 0.28).

Figure 4. Lifetime suicidal ideation.

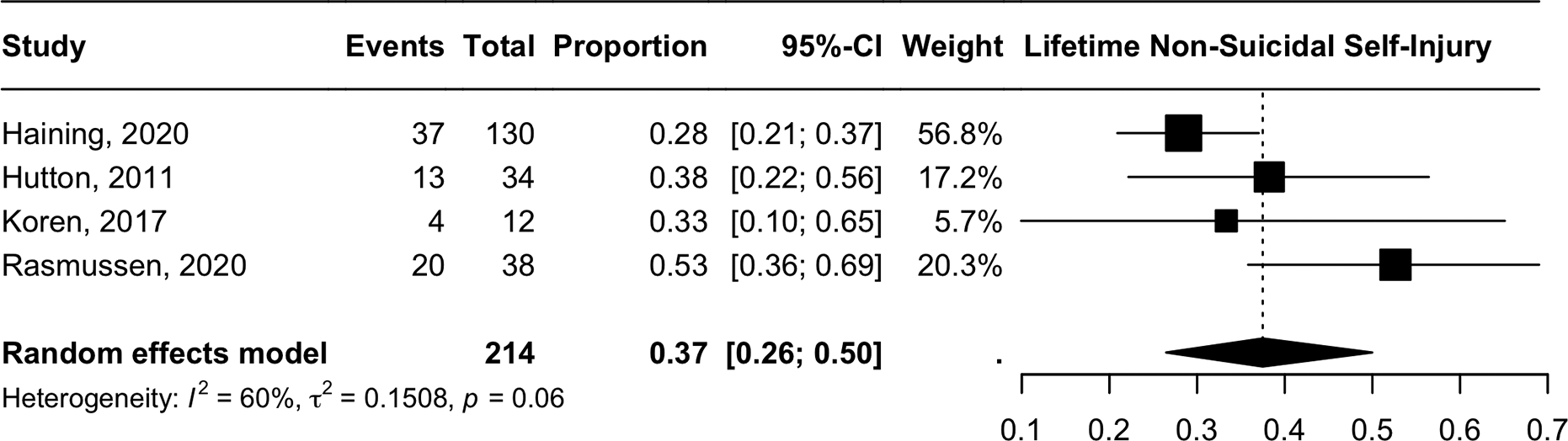

Non-suicidal self-injury

The meta-analysis of non-suicidal self-injury indicated a prevalence of 37.49% (CI 95% 26.47–49.98, n = 214, I 2 = 60%, p = 0.060), with moderate heterogeneity. (Figure 5) The degree of heterogeneity is attributable to the high rates of NSSI reported in Rasmussen et al. [Reference Rasmussen, Reich, Lavoie, Li, Hartmann and McHugh40] (52.6%, n = 38), whereas the prevalence reported in the other three studies ranges from 28.5 to 38.2%. The removal of this study reduced heterogeneity to non-significant levels (I 2 = 0) and led to a smaller prevalence estimate of 30.79% (CI 95% 24.39–38.03, p = 0.54).

Figure 5. Lifetime non-suicidal self injury.

For the prevalence of current NSSI (one-month), one study reported it at 5.38% (n = 7/130) [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35].

CAARMS/MINI suicidality severity

One study reported continuous mean data for the CAARMS severity scoring, a seven-point scale that reflects the intensity of suicidal thinking and self-harm behaviour. Pelizza et al. [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36] reported an average CAARMS suicidality score of 1.83 (95% CI 0.02–3.64) in its population, with 50% (n = 20/40) reporting a score of > = 2 [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36]. A score of 2 on the CAARMS corresponds to occasional thoughts of self-harm without active suicidal ideation plans [Reference Yung, Yuen, Phillips, Francey and McGorry44]. This apparent inconsistency with the high prevalence of suicidal ideation reflected by the BDI-II questionnaire (68.0%, n = 27/40) in the same study could be attributed to the interview mode of administration for CAARMS, which might discourage explicit disclosure of suicidal thoughts to the interviewer [Reference Kaplan, Asnis, Sanderson, Keswani, de Lecuona and Joseph45].

Another study reported data on the Mini Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Suicidality Subscale [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35]. The MINI Suicidality Subscale categorizes respondents as low, moderate, or high suicidal risk based on six questions relating to recent suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, suicidal attempts, and lifetime suicidal attempts [Reference Roaldset, Linaker and Bjørkly46]. 21.5% (n = 28/130) were classified as low MINI Suicidality risk, while 16.2% (n = 21/130) were each classified as moderate and high MINI Suicidality risk. Considering the study’s significant prevalence of past suicidal attempts (29.2%), non-suicidal self-injury (28.5%), and past 1-month suicidal ideation (34.6%), the MINI Suicidality Subscale accurately reflects the high level of suicidality in the studied population.

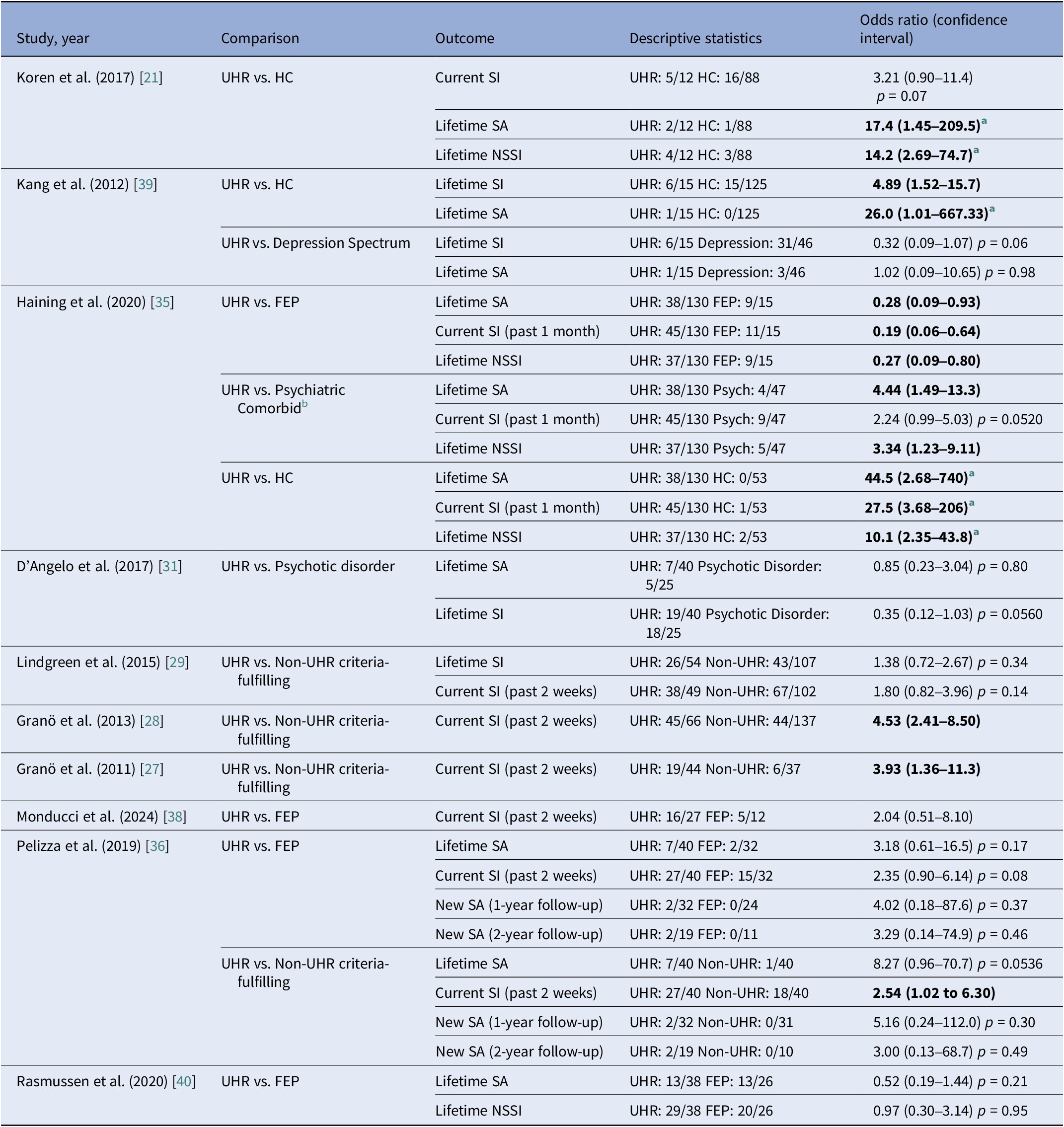

Group comparison

Ten studies established comparisons between UHR and other groups (e.g., Non-UHR-Criteria-fulfilling patients, first-episode psychosis, depressive disorders, psychotic disorders, other psychiatric conditions, and healthy control). The large degree of variance by outcome and comparison groups did not allow for a meta-analysis of the results. The results of these comparisons are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison between UHR and other groups

Significance = p < 0.05, odds ratio (OR) and associated 95% confidence interval calculated from study data for purposes of review. Bolded indicates significant finding.

SI , suicidal ideation; SA , suicide attempt; NSSI , non-suicidal self-injury; HC , healthy control; FEP , first episode psychosis.

a Few cases were present, interpret test and odds ratio with caution.

b Psychiatric comorbid includes mood disorder, anxiety disorder, drug abuse/dependence, alcohol abuse/depending, and eating disorder.

Lifetime suicidal attempts, suicidal ideation, and non-suicidal self-injury were more prevalent among the UHR population compared to healthy controls. Apart from one study [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29], current (2 week) suicidal ideation was also higher in UHR groups compared to Non-UHR-Criteria fulfilling groups. Suicidal attempts, suicidal ideation, and non-suicidal self-injury were generally lower in the UHR population compared to the FEP group. There was no significant difference in suicidal behaviour between UHR and groups with Depressive Disorders or Psychotic Disorders.

Predictors of suicidal behaviour

Demographics

Two studies reported longitudinal data associating demographic variables and suicide. Pelizza et al. [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37] reported a higher prevalence of new suicide attempts in an ethnic (non-Caucasian) population during a 2-year follow-up period, with no associations between gender, age, and education [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37]. Girls with UHR status were more likely to be at risk of current suicidal ideation than boys (p = 0.008), but this relationship did not hold for lifetime suicidal ideation [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29].

Family history of psychosis

Two studies reported a longitudinal relationship between a family history of psychosis and future suicidal attempts. Having at least one first-degree relative with psychosis was a risk factor for a new suicidal attempt within a 2-year follow-up period (HR = 9.834, p < 0.01) [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37]. Lingrend et al. [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29] reported that a family history of psychosis was also a risk factor for future NSSI in a nine-year follow-up period [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29].

Previous suicide attempts

Haining et al. (2020) reported a positive cross-sectional relationship between previous suicide attempts and lifetime suicidal ideation (OR = 2.701, p = 0.040) [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35]. Pelizza et al. [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37] reported that new longitudinal suicide attempts were associated with a past suicidal attempt (HR = 7.918, p = 0.026) [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37].

Transition to psychosis

Two studies reported a longitudinal relationship between eventual transition to psychosis and suicidal behaviour. One study reported that eventual psychosis transition in a 2-year follow-up period strongly predicted a new suicidal attempt (HR = 3.919, p = 0.017) [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37]. Similarly, psychosis transition within a 9-year follow-up period was associated with new NSSI (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.08) [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29].

Psychiatric comorbidity

Psychiatric comorbidity was typically associated with greater suicidal behaviour. Both current and lifetime suicidal ideation were associated with depression (p < 0.001, [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36]) and non-psychotic mood disorders at baseline (p = 0.002 and p < 0.001 respectively; [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29]). Dysphoric mood (as assessed by SIPS) was also significantly associated with the severity of suicidal ideation. (r = 0.52, p = 0.001; [Reference D’Angelo, Lincoln, Morelli, Graber, Tembulkar and Gonzalez-Heydrich31]). Substance usage was found to be related to lifetime suicidal behaviour (Mann–Whitney U = 3,387.5, p = 0.007; [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29]). Co-morbid Axis 1 disorders were also found to be associated with current suicidal ideation in one study (OR = 1.631, p = 0.014; [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35]); however, details of the specific illnesses investigated were not reported. Anxiety disorder and eating disorder at baseline did not offer predictive value for suicidal behaviour [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29].

Certain features of psychosis also exhibited strong associations with suicidal behaviour. Negative symptoms exhibited strong associations with current suicidal ideation (r = 0.49, p = 0.002; Gill et al., 2015) [Reference Gill, Quintero, Poe, Moreira, Brucato and Corcoran30], with one study [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29] specifically identifying avolition (r = 0.42, p < 0.001; [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29]) and decreased expression of emotion (r = 0.31, p < 0.001; [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29]) as predictive factors (as measured by SIPS). Basic Self-Disturbance exhibited a strong association with past suicidal attempts [Reference Koren, Rothschild-Yakar, Lacoua, Brunstein-Klomek, Zelezniak and Parnas21]. Studies employing continuous subscale measures for UHR psychosis also reported correlations between Huber Basic Symptoms (as measured by CAARMS) and the severity of current suicidal ideation [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36]. The “Odd Behaviour/Appearance” subscale of SIPS was also found to be predictive of the severity of lifetime suicidal ideation. (r = 0.45, p = 0.005; [Reference D’Angelo, Lincoln, Morelli, Graber, Tembulkar and Gonzalez-Heydrich31]). No association was found between Positive Symptoms and current suicidal ideation [Reference Pelizza, Poletti, Azzali, Paterlini, Garlassi and Scazza36].

Functioning

Functional impairment refers to the overall social and occupational impairment caused by psychiatric illness [Reference Pedersen, Urnes, Hummelen, Wilberg and Kvarstein47]. Functional impairment exhibited strong cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with suicidal behaviour and ideation. Current suicidal ideation was predicted by functional impairment, as measured by decreased Global Assessment Functioning (GAF) (r = 0.48, p = 0.002; [Reference Gill, Quintero, Poe, Moreira, Brucato and Corcoran30]) (r = 0.53, p = 0.001; [Reference D’Angelo, Lincoln, Morelli, Graber, Tembulkar and Gonzalez-Heydrich31]) and Global Functioning: Social (GF: Social) scores [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35]. New suicidal attempts during a 2-year follow-up period were also predicted by longitudinal functional impairment as measured by CAARMS (HR = 1.70, p = 0.02; [Reference Pelizza, Leuci, Quattrone, Azzali, Pupo and Paulillo37]) School bullying was not found to be a significant predictive factor for suicidal behaviour [Reference Lindgren, Manninen, Kalska, Mustonen, Laajasalo and Moilanen29].

CAARMS severity

Lower CAARMS severity was found to be marginally associated with reduced current suicidal ideation (OR = 0.971, p = 0.043; [Reference Haining, Karagiorgou, Gajwani, Gross, Gumley and Lawrie35]). There was no similar data available for the other validated tools used for UHR Psychosis such as SIPS [Reference Miller, McGlashan, Rosen, Cadenhead, Ventura and McFarlane12], PROD [Reference Monducci, Mammarella, Maffucci, Colaiori, Cox and Cesario38], or K-SADS [Reference Kaufman, Birmaher and Brent48].

Discussion

The results of this novel meta-analysis suggested that suicidal behaviour was highly prevalent in the UHR youth and adolescent population, particularly with regards to lifetime and current suicidal ideation. Over half of UHR youth reported lifetime (56.34%) and current (57.75%) suicidal ideation, with a quarter (25.00%) reporting a lifetime suicide attempt. A previous meta-analysis on suicidal behaviour in the adult UHR population suggested similar rates of suicidal behaviour (66% prevalence for current suicidal ideation, 18% for lifetime suicide attempts) [Reference Taylor, Hutton and Wood7].

Group comparisons between UHR, healthy controls, and First Episode of Psychosis (FEP) groups in this meta-analysis revealed greater lifetime suicidal attempts and suicidal ideation in UHR youth than healthy controls. However, suicidal attempts, suicidal ideation, and non-suicidal self-injury were generally higher in the FEP population than the UHR population. The greater prevalence may be attributed to the difference in psychotic experiences experienced by both demographics. Current literature reflects that both UHR and FEP youth may experience similar levels of impaired social functioning [Reference Popolo, Vinci and Balbi49] and cognitive dysfunction (e.g., worsening academic performance) [Reference Roy, Rousseau, Fortier and Mottard50]. However, the UHR population may be shielded from some of the challenges associated with the first episode of psychosis, including heightened psychotic symptoms [Reference Larson, Walker and Compton51], distressing interventions such as involuntary hospitalisation [Reference Strauss, Zervakis, Stechuchak, Olsen, Swanson and Swartz52] and associated stigma [Reference Oexle, Waldmann, Staiger, Xu and Rüsch53]. Nonetheless, suicidal behaviour remains a major adverse outcome for UHR youth and should be adequately addressed during intervention.

The risk factors for suicidal behaviour identified in this study mirrors prior findings in the schizophrenia-spectrum disorder population. Co-morbid depression and poor functioning were found to be risk factors in the FEP youth population [Reference Toll, Pechuan, Bergé, Legido, Martínez-Sadurni and Abidi54]. Negative symptoms (e.g., anhedonia) were found to be suicidal risk factors in both UHR and the schizophrenia population [Reference Grigoriou and Upthegrove55, Reference Poletti, Pelizza and Loas56]. Prior suicidal attempts, as a risk factor for new suicidal attempts, was also supported by findings in the FEP youth [Reference Moe, Llamocca, Wastler, Steelesmith, Brock and Bridge57, Reference Pelizza, Lisi, Leuci, Quattrone, Palmisano and Pellegrini58] and general schizophrenia [Reference Cassidy, Yang, Kapczinski and Passos59] population. This highlights the importance of identifying and treating co-morbidities that drive up the risk of suicide in all stages of psychotic disorders – including UHR, first episode of psychosis, or schizophrenia.

There are certain limitations in this review. Precise definitions for non-suicidal self-injury were not consistently provided by the included studies. This could have led to variances in behaviours that were considered as self-harm between the different studies. These studies could have benefited from utilising standardised nomenclature for defining self-harm [Reference Goodfellow, Kõlves and de Leo60]. Secondly, studies included in the meta-analysis for current suicidal ideation were limited due to variances in instrumental measurement. The meta-analysis only includes studies that used the BDI-II to assess for current suicidal ideation. This resulted in the exclusion of certain studies that utilised other instruments (e.g., BDI-I [Reference Lasa, Ayuso-Mateos, Vázquez-Barquero, Dı́ez-Manrique and Dowrick61], C-SSRS [Reference Bjureberg, Dahlin, Carlborg, Edberg, Haglund and Runeson62]). Additionally, studies were too few to allow for systematic exploration of heterogeneity (e.g., publication bias, meta-regression). Nonetheless, heterogeneity was addressed via the random effects model during analysis. The total number of participants for the analyses was also sufficiently large, such that prevalence rates remained high even with the removal of outlier studies. Lastly, language barriers of reviewers also prevented the inclusion of non-English language articles. This may have hindered the generalisability of results in an international context.

In summary, this study demonstrates a concerning level of suicidal behaviour within the UHR youth population, which necessitates a paradigm shift in the treatment of UHR youth. To date, early intervention programmes for UHR youth feature a mix of psychological therapy, pharmacotherapy, family intervention, and social intervention [Reference Williams, Ostinelli, Agorinya, Minichino, De Crescenzo and Maughan63]. with the overarching goal of reducing the risk of transition to psychosis [Reference Mei, van der Gaag, Nelson, Smit, Yuen and Berger64]. Future emphasis should also be placed on reducing suicidal ideation in this group. Potential psychological treatment methods include Dialectical Behavioural Therapy, which has demonstrated efficacy in reducing adolescent self-harm and suicidal ideation [Reference Kothgassner, Goreis, Robinson, Huscsava, Schmahl and Plener65]. Increasing the frequency of outpatient follow-up for UHR youth may also reduce suicidal ideation [Reference Ee, Gwon and Kim66]. Recognising the psychological pain – defined as intense feelings of shame, distress and hopeless – associated with UHR psychotic experiences is also important, given its strong predictor of suicidal behaviour [Reference Pompili67].

In addition to addressing suicidal behaviour, mental health professionals should also address co-morbidities that increase suicidal risk, such as depression and substance use [Reference Brådvik68]. Lastly, clinicians working with youths who present with self-harm injuries (e.g., Paediatricians, Emergency Physicians) may also benefit from greater familiarity with the UHR criteria. This allows for early specialist referral and prevents transition to frank psychosis.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.2444.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, A.S.H., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lim Siu Chen of the National University of Singapore Libraries for providing support with search strategy formulation. The authors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the studies being reported; that no important aspects of the studies have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the studies as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Author contributions

A.S.H., V.S., and M.G. contributed to the formulation of the research question, formulation, execution, and coding of the search strategy, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. K.N. contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript. M.S. and G.K.K. contributed to the formulation of the research question, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.