In the 1940s and early 1950s, the Cold War conventions that undergirded the growing American involvement in Vietnam – essentially, that the containment of the global Soviet–communist threat to the West required building a noncommunist bulwark in (southern) Vietnam, with American support – were broadly shared, internalized, at times even fostered, by the United States’ European allies. That consensus broke down by the 1960s as successive US administrations, in particular that of President Lyndon B. Johnson, saw themselves locked ever more rigidly into the Cold War logic that seemed to require going to war to preserve a noncommunist South Vietnam: American officials feared that the credibility of American defense commitments in Europe and elsewhere around the world would be diminished should the Vietnamese communists take over the country. In fact, US efforts to demonstrate resolve in Vietnam hurt rather than enhanced the credibility of American power, commitments, and prestige in the eyes of many Europeans. The United States’ transatlantic allies and partners increasingly came to question the very rationale of the US intervention: that South Vietnam’s survival was vital to Western security, to winning the Cold War. With ever greater investment of American manpower and other resources in Vietnam, security interests on both sides of the Atlantic began to diverge. Washington’s Cold War intervention in Southeast Asia helped to catalyze new efforts in Western Europe to contain and transform the Cold War altogether, at home and abroad. At the same time, the Vietnam War tore at the very fabric of values and bonds imagined to constitute the West, and to a part of a generation of West Europeans American warfare in Southeast Asia came to represent systemic evil.

By 1964–5 there was a remarkable consensus among government officials across Western Europe about the futility of the central objective of the American intervention in Vietnam of defending and stabilizing a noncommunist (South) Vietnam. Similarly remarkable was the common European phalanx of obstinate refusal when it came to providing military support eagerly and increasingly desperately sought and expected by the Johnson administration: not one of Washington’s European allies would send troops to Vietnam. To be sure, West European governments differed considerably in the public attitude they displayed toward the United States in Vietnam: On one end of the spectrum stood France’s strategic opposition to (and Sweden’s principled and vocal criticism of) the Vietnam War. By contrast, the British and West German governments exhibited strong though not limitless public support for their US ally. Yet for their own historical, political, and geostrategic reasons they resolved not to make even a nominal troop commitment either. Across Western Europe, the Vietnam War cut deeply into West European domestic politics, aggravated political and societal tensions, and diminished the righteousness of the United States’ – and the West’s – cause in the eyes of many Europeans.Footnote 1

France: Strategic Opposition

Among the United States’ NATO allies, France emerged as the sharpest critic of the expanding American involvement in Vietnam in the 1960s. This was not without some irony, as the French political class of the Fourth Republic had just two decades earlier staked their nation’s credibility as a global power on its continued colonial hold on Indochina and to that end made an all-out effort to engage the United States in the region. Born of the humiliation that French national pride had suffered in defeat, occupation, and collaboration in World War II, this “unprecedented imperialist consensus” across the domestic political divide had induced an “unquestioning faith in imperial possessions” as a marker of global power.Footnote 2 With the French empire in Southeast Asia threatened by a wartime Japanese takeover and after war’s end by the revolutionary Việt Minh movement led by Hồ Chí Minh, French policymakers mobilized American support for colonial restoration, above all, as Mark Lawrence has persuasively argued, by “recasting the Vietnamese political situation” in the late 1940s as a Cold War conflict stemming “from the same causes and requiring the same solutions as anticommunist fights elsewhere.” France had in fact joined the Western side in the bipolar confrontation belatedly and reluctantly, for this relegated the country to second-class status. But the new global conflict offered a chance to attract Washington’s backing for a colonial project it had only recently opposed by selling the Americans on the idea of a Western-oriented Vietnamese nationalism led by former emperor Bảo Đại. By early 1950, the French government had successfully lobbied the administration of Harry Truman into supporting the French war effort against the Việt Minh.Footnote 3

In the following years, French officials proved adept at manipulating American Cold War anxieties to retain US aid to French Indochina. They played on American fears of domestic instability in France and exploited Washington’s commitment to strengthening the transatlantic alliance. Most importantly, they leveraged keen American interest in securing French support for West German rearmament (considered critical to bolstering Western defenses in Europe) to extract US aid for French efforts in Indochina. The French government was able to successfully condition its support of the European Defence Community on, among other things, cuts to its military expenditures in Vietnam. By 1954, the United States had provided France with nearly as much aid in Vietnam as it had under the Marshall Plan.

At the same time, frictions developed between the two countries over the conduct of the French Indochina War. Franco-American disagreements climaxed over the Điện Biên Phủ crisis and during the Geneva Conference in 1954. In the following two years France retreated militarily from Vietnam in the face of “South Vietnamese and American determination to replace France at every level – whether political, military, economic, or cultural.” In May 1956 France formally relinquished its responsibility to enforce the Geneva Agreements. Through educational and commercial programs France fought to hold on to a degree of economic and especially cultural presence in Vietnam, with growing success by the late 1950s. Prompted in part by French support of South Vietnam’s bid to join the United Nations in 1957 and the Franco-Vietnamese accords of March 1960, by the beginning of the decade France had managed to stage a “miraculous comeback” and rebuild its cultural and economic footprint and behind-the-scenes political influence in the country.Footnote 4

The loss of colonial empire in Southeast Asia fed into the growing sense of frustration in the late Fourth Republic with the country’s place in the world. General Charles de Gaulle tapped into this discontent and, once returned to power as president of the Fifth Republic, he sought to restore France’s “rank” in world affairs. De Gaulle set about to transform the Cold War system that had relegated France to a secondary role: by demanding a rebalance of power within the Atlantic alliance to give France greater weight and independence; by calling for greater autonomy for Western Europe vis-à-vis the United States; by recasting France as a mediator between East and West; by reaching out to the Third World and championing North–South cooperation.Footnote 5 The growing American involvement in Vietnam epitomized to de Gaulle why it was necessary to reassert French leadership and independence: in his view, the Vietnam problem distracted US attention and resources from strengthening NATO’s defense capacity on which his country relied. In the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 it was not even entirely inconceivable that the brewing crisis in Vietnam might drag France into a full-scale conflict with Moscow. Staking out a contrarian approach to Vietnam also served as a perfect foil to challenge the United States and enhance his reputation as maverick global statesman.

The colonial experience in Indochina informed de Gaulle’s concern about American policy vis-à-vis Vietnam.Footnote 6 At their first meeting at the Elysée Palace in May 1961 de Gaulle warned President John F. Kennedy against the more forceful intervention in Southeast Asia that was being considered by the latter. According to his memoirs, de Gaulle told JFK that “the more you become involved out there against the Communists, the more the Communists will appear as the champions of national independence, and the more support they will receive, if only from despair. We French have experience of it. You Americans want to take our place … I predict that you will sink step by step into a bottomless military and political quagmire, however much you spend in men and money.”Footnote 7 The next year, de Gaulle, along with British prime minister Harold Macmillan, successfully prevailed on Kennedy to agree to a negotiated settlement rather than military intervention in neighboring Laos.

De Gaulle came to advocate a neutralization scheme in Vietnam similar to the solution reached for Laos which effectively removed the country from the Cold War agenda. The French leader contested the notion that a compliant, pro-Western nationalism could in fact be implanted in the South, one that would draw support away from the revolutionary nationalism represented by Hồ Chí Minh in the North. He became convinced that Western nation-building in Vietnam, even if reinforced by superior American military might, was a losing proposition, as he viewed the struggle in Vietnam as “fundamentally a political and not a military problem – a struggle for the minds and hearts of the people of South Vietnam.” Nor did de Gaulle fear that unification under communist control, which would likely result from a neutralization scheme, would strengthen global communism: Vietnamese nationalism, he ventured, would resist Chinese or Soviet control, much as it had eluded mastery by the West. Most importantly, neutralization would reduce American commitments, freeing up critical Western resources urgently needed on Cold War fronts de Gaulle deemed more important than Vietnam.Footnote 8

When a full-blown political crisis in South Vietnam in the spring and summer of 1963 threw the deteriorating situation in the country into sharp relief, de Gaulle offered his sharpest public critique of US involvement in Vietnam yet and seized the moment to position himself as the leading European critic. Referring to the long relationship between the two countries that allowed the French people to “understand particularly well, and share sincerely, the hardships of the Vietnamese people,” de Gaulle declared in a major address in August that the French could see the positive role Vietnam could play “for its own progress and for the benefit of international understanding, once it is able to carry on its activity independent of outside influences, in internal peace and unity, and in concord with its neighbors.”Footnote 9 France, de Gaulle implied, supported Vietnam’s reunification and independence and opposed both Soviet and Chinese as well as American involvement. His push for a diplomatic solution to the Indochina conflict also pursued geopolitical ambitions: it paved the way for the grand reentry of France into the politics of a region it had left in defeat: “Nous faison notre rentrée en Asie,” de Gaulle told a confidant after his August speech.Footnote 10

With France’s cultural shadow and economic footprint still looming large in Vietnam, de Gaulle’s speech immediately produced widespread speculation in Vietnam about whether the general was suggesting a Laos-type neutralization to reunify the country. The vague nature of de Gaulle’s pronouncement facilitated its getting widespread traction. American policymakers were faced with the dilemma that de Gaulle’s initiative raised the possibility of a North–South peace precisely “at a time when US officials were working feverishly to strengthen the war effort.”Footnote 11 The general’s critique, moreover, came as the Kennedy administration sanctioned a coup d’état against the increasingly repressive and unpopular regime of Diệm and his brother Ngô Đình Nhu. Not only could de Gaulle’s announcement be seen as a shot in the arm for the faltering Diệm regime, but it also raised alarms in Washington that Diệm and Nhu might engage de Gaulle with a scheme for the neutralization of South Vietnam to thwart any action against them. Once a new military junta had been installed in a bloody, US-sanctioned coup against the Diệm regime in early December, paradoxically, US officials came to suspect rather quickly that it too harbored pro-French sympathies; according to one source the new government was “70 percent pro-French.”Footnote 12

De Gaulle’s August speech outraged official Washington, which saw it as little more than grandstanding. But efforts to tone down French criticism only led French leaders to double down in their efforts to challenge American policy as the situation continued to deteriorate in South Vietnam. Anticipating a growing US military engagement in support of the new military junta under the leadership of General Dương Vӑn Minh, De Gaulle told US ambassador Charles E. Bohlen that “you will be blamed for the deaths of Diệm and Nhu” and warned of the disastrous consequences of greater American involvement. The very public French insistence that the American effort to bring about a noncommunist independent South Vietnam was doomed to fail, as Fredrik Logevall has pointed out, also created space for growing criticism within the US media, where influential voices increasingly echoed French demands for a negotiated settlement and questioned American strategy. De Gaulle’s statement became a frequent reference point for those in the United States who began to cast doubt on the thrust of American policy in Vietnam.Footnote 13

Vietnam also played into de Gaulle’s formal recognition of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on January 27, 1964. The resumption of Sino-French diplomatic ties was part of his larger strategy to break the Anglo-American dominance in the West. The decision “to play the China card” seems to have been spurred in particular by the Limited Test Ban Treaty signed by the United States, the USSR, and the United Kingdom in August 1963, which he viewed as a threat to French global interests. The establishment of mutual relations reflected a partial alignment of French and PRC interests on a number of issues – including an end to the Algerian liberation struggle in the spring of 1962, but also a growing sense of China’s importance. At a news conference, de Gaulle announced that there was “no political reality in Asia” which did not affect China, and that it was “absolutely inconceivable that without her participation there can be any accord on the eventual neutrality of Southeast Asia.”Footnote 14 But China’s diplomatic elevation by the French Republic further undercut the core rationale upon which the growing US commitment to South Vietnam rested: that the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) was to be a noncommunist bulwark against communist China’s expansion in the region. Not surprisingly, the French initiative fell on deaf ears in Washington, where another coup in South Vietnam, replacing the Minh junta with that of General Nguyễn Khánh, had given rise to new hopes for prevailing in the conflict.

The US–French rift over Vietnam continued after Lyndon B. Johnson succeeded his slain predecessor in the presidency. If anything, de Gaulle became more reluctant to give in to ever more desperate American pressure for some level of support from Paris. In early March 1964, French foreign minister Maurice Couve de Murville declined a request from Washington, conveyed through Bohlen, that the French government “clarify” publicly that it was opposed to neutralization and refrain from any statements on Vietnam. Later that month, de Gaulle refused a US request to state that the neutralization idea would not apply to the Government of Vietnam at this stage “in the face of the current communist aggression.” At the annual South East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) meeting, Couve de Murville repeated his government’s conviction that the United States would not succeed in Vietnam, as France had failed there in 1954 and in Algeria in 1962, where in spite of France’s complete physical control of the country “we lost the battle.” China, Couve de Murville argued instead, would agree to a neutralization scheme. Underscoring its opposition to the American strategy, France chose to abstain from supporting a conference communiqué on the independence of South Vietnam.Footnote 15 Another Johnson administration mission to Paris in early June, this time in the person of Under Secretary of State George Ball, equally failed to move the French president: Vietnam was a “rotten country,” he told the American, where the United States’ efforts to win by force were doomed to failure.Footnote 16

As the LBJ administration embraced the US commitment to South Vietnam as a total one in the summer of 1964, de Gaulle strengthened his efforts to reconvene the Geneva Conference. In late June, he called for a new Geneva conference during a visit to Paris by Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, and in a major speech a month later announced that “since war cannot bring a solution, one must make peace” by a return to Geneva. Unlike his earlier pronouncements, de Gaulle proposed that the conference cover the entire region, not just, as he had argued earlier, the continued fighting in Laos. He also stipulated that, to be successful, the conference had to comprise the same participants and convene without preconditions. From Washington, President Johnson blasted the French initiative, telling reporters that “we do not believe in a conference called to ratify terror.”Footnote 17

De Gaulle seemed to take the escalation of American involvement in Vietnam in February–March 1965 rather philosophically, suggesting that the United States would find itself bogged down militarily for a long time. In fact, de Gaulle continued to push for an early end to the conflict, at multiple levels. With Vietnam on the agenda during Soviet foreign minister Andrey Gromyko’s visit to Paris in the spring of 1965, de Gaulle signaled his eagerness to bring about a diplomatic solution, all the while casting himself in a central role. Paris also became a pivotal venue for secret negotiations exploring a potential path toward a negotiated solution, the so-called XYZ talks between the United States and North Vietnamese representatives. All of this required holding back on the criticism he leveled at the United States publicly. To be sure, there was little that could be done to turn French public opinion against the United States any further; by 1965, it was the most anti-American in Western Europe, with de Gaulle’s opposition to American hegemony boosting his electoral appeal.Footnote 18

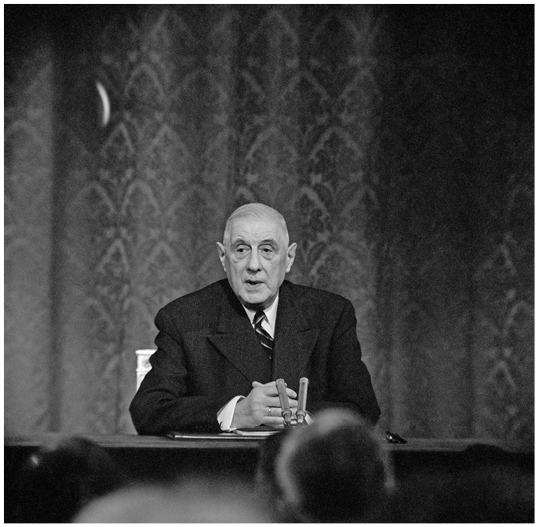

Figure 26.1 French president Charles de Gaulle at a press conference on Vietnam (October 28, 1966).

With the failure of these efforts in the face of increased US military efforts in Vietnam, de Gaulle, by 1966, once again stepped up his vocal criticism of the United States. Perhaps the climax of these efforts was his September 1, 1966, speech in Phnom Penh, in which de Gaulle came out strongly in support of Cambodia’s neutrality and, more generally, the emancipation of subject peoples, attributing the collapsing situation in South Vietnam to the American presence. Later that year de Gaulle decried the war in Vietnam as unjust and blamed it on the armed intervention of the United States, a “despicable war since its leads a great nation to ravage a small one.”Footnote 19 By 1968, de Gaulle’s foreign policy had turned into “an all-out crusade”Footnote 20 against US preponderance, with Vietnam as exhibit no. 1. Yet for all his exasperation with the American war, de Gaulle remained committed to furthering a diplomatic outcome. In 1967, the French Foreign Ministry endorsed French civil society initiatives to explore a negotiated settlement and conveyed the result of such efforts to American negotiators. It was a fitting recognition of France’s strenuous diplomatic efforts and intermediary role that the final peace negotiations took place in Paris.

Great Britain: Restrained Support

For Great Britain, too, hanging on to its imperial position “east of Suez,” in the Persian Gulf and Malaya–Singapore, had in the aftermath of World War II been vital to its self-image as a global power and a leading actor in the Asia–Pacific theater. Not surprisingly, British officials had been sympathetic to the restoration of French colonial rule in Indochina, as any challenges to French hold on its colonies, whether from China or the United States, had the potential to aggravate the difficulties of British colonial empire in Southeast Asia. More generally, British governments saw themselves as representing Western interests in stability in East Asia against communist upheavals, and they valued continued French rule in Indochina in these terms. Most importantly, they viewed France’s hold on Indochina as critical to resuscitating a psychologically, economically, and militarily weakened partner in Europe where British strategic outlook demanded French capacity to balance a potentially resurging Germany and growing Soviet power to its east.Footnote 21

Working with their French counterparts, British policymakers tried to blunt American hostility toward colonialism of the French variety by advancing political and economic concessions that sought to temper the sharpest edges of colonial rule (including international control); and by appealing to US strategic and economic interests that would best be served by continued French control of Indochina. Britain hence played a key role in helping to bring about the Western partnership in support for the French war against the Việt Minh, feeding a vision of Vietnamese politics that could supposedly be shaped to accommodate both Western and Vietnamese interests. With American support accomplished by 1950, “London could at last settle into the position to which it had aspired, that of benevolent but low-profile support for its close ally,” France. From the mid-1940s to mid-1950s, British governments, whether Labour or Conservative, managed to maneuver the United States into the leading role in backing French colonial rule, into “assuming the burden” of the fight while lessening that on Britain itself. “Most impressive of all,” writes Mark Lawrence, “the British government achieved that aim while preserving a significant degree of political leadership in Southeast Asia.”Footnote 22

Early diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China in 1950 and cochairmanship of the Geneva Conference in 1954 reflected London’s efforts to preserve this leadership role during a period of escalating Cold War tensions caused by the Korean War. Thanks to long-standing ties to the region, British officials understood that Asian communism was too multifaceted to lend itself to simplistic zero-sum calculations for the global Cold War balance sheet that had become the predominant paradigm in Washington. Instead, they feared Cold War logic could pull the United States and its SEATO allies into a major military conflagration. As Washington’s closest partner in the region, Britain therefore also sought to exert a moderating influence on American policy during the Korean War in 1950–3, the Điện Biên Phủ crisis in 1954, and again during the Laos Crisis in 1961–2 (which led to a reconvening of the Geneva Conference). An unenthusiastic (though ultimately loyal) SEATO participant, London backed the division of Vietnam at Geneva and later the neutralization of Laos and Cambodia. This deescalatory approach was echoed in British opposition in 1963 to American plans to bomb North Vietnam and a series of peace initiatives following the American military intervention in the spring of 1965.Footnote 23

But this was only one side of the coin of British policy. Just as it had committed considerable resources to the French fight against the Việt Minh prior to 1950, in the second half of the 1950s London was eager to support the struggling Saigon regime, especially after the communist insurgency had organized itself as the National Liberation Front (NLF) in 1960. Convinced that British success in dealing with the “Malayan Emergency” had positioned them exquisitely to help the Americans and South Vietnamese deal with the growing NLF insurgency in the RVN, British officials felt the time had come to play a more active part in Vietnam. By the end of the 1950s London shared the basic American assumption that South Vietnam could be stabilized by strengthening the capacity of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) to deal with the insurgency. In 1960–1 the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan lobbied the Kennedy administration to allow it to send an advisory mission to Vietnam. The mission served not just to aid the growing number of American military advisors in South Vietnam to find the winning formula to turn around the situation in South Vietnam. It also demonstrated that the UK was willing to do its part in fighting the Cold War and strengthen the “special relationship” with the United States, which was fraying in East Asia from disagreements over Laos. The mission was also to assuage Australia, New Zealand, and Malaya, all British Commonwealth allies that strongly supported the American anticommunist campaign. This British commitment to a military victory in South Vietnam sharply curbed its efforts after Geneva to find a diplomatic solution: in fact, as one Foreign Office official noted in 1962, “the policy which we have agreed with the Americans is to avoid international discussion on Vietnam until the military situation has been restored.”Footnote 24

The South Vietnamese leadership and much of the American military establishment in the RVN was at first staunchly opposed to a British Advisory Mission (BRIAM). With support from the US State Department, London was finally, in the spring of 1961, able to gain the Kennedy administration’s approval for its new role in Vietnam. In September a five-man counterinsurgency mission under Robert Thompson, Malaya’s permanent undersecretary of defense, would give London an important observation post and new stakes in the conflict in Vietnam; in 1963 the British Advisory Mission was extended for another two years. While the American failure to stabilize the Saigon regime led some in the Foreign Office as early as 1961 to view Vietnam as “a more dangerous problem than Laos,” many British officials, including BRIAM leader Robert Thompson, were optimistic, well into 1963, about the possibility of creating a pro-Western South Vietnam.Footnote 25

While the Macmillan government was supportive of American policy, it did not consider Vietnam a “vital theater of the Cold War.” Shortly after de Gaulle’s August 1963 speech criticizing the failing American involvement, the prime minister noted that “with so many other troubles in the world we had better keep out of the Vietnam one.”Footnote 26 For officials in London, the Vietnam problem was soon overshadowed by the “Confrontation” with Indonesia, which brought the costs and fragility of the British position “east of Suez” into sharp relief. Triggered by the creation in September 1963 of the “Federation of Malaysia” (comprising Malaya, Singapore, and the island of Borneo, to whose northern half Indonesia laid claims), the low-intensity border conflict soon consumed British attention and resources. Amidst more frequent calls in Britain for giving up positions “east of Suez,” American officials worried about a dangerous power vacuum in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. In February 1964, Johnson and the Conservative prime minister Alec Douglas-Home, who had succeeded Macmillan after the latter’s resignation in October 1963, assured each other once more of their intention to oppose aggression and pledged their mutual political support for their Southeast Asia projects. Yet, as his predecessor had done, Douglas-Home evaded the Johnson administration’s mounting pressure for British troop support in Vietnam.

Prime Minister Harold Wilson, whose Labour Party narrowly won the October 1964 elections, continued British diplomatic support of Johnson’s determination to stave off defeat in Vietnam. A decade earlier, he had warned that “not a man, not a gun,” must be sent to Indochina. “We must not join with nor in any way encourage the anti-Communist crusade in Asia, whether it is under the leadership of the Americans or anyone else.”Footnote 27 Once settled in 10 Downing Street, though, Wilson muted his criticism of Washington, and in fact sought to make the “special relationship” with the United States the “cornerstone of his foreign policy.”Footnote 28 Under American pressure, the British government stymied French and Soviet efforts in November–December to convene another Geneva conference to discuss the neutralization of Cambodia (which would have raised the prospect of a similar diplomatic effort for South Vietnam – anathema to Washington). When he met with Lyndon Johnson in December 1964 on the heels of the latter’s landslide election victory, Wilson signaled his general support for the president’s Vietnam policy. Yet he refused to give in to American demands for a British military contribution in Vietnam, pushed ever more persistently by the administration as part of its “More Flags” campaign, which was to demonstrate symbolically international support for its Vietnam policy. Johnson is said to have told Wilson that “a platoon of bagpipers would be sufficient, it was the British flag that was needed.”Footnote 29

In evading Johnson’s request, Wilson pointed to Britain’s role as a cochair of the Geneva Conference, to the unpopularity at home of any British military contribution, and, above all, to the substantial deployment of British money and men – some 80 naval vessels in the area and (at the peak) some 50,000 troops deployed in Borneo – in fighting the Confrontation. With the Americans increasingly concerned about Britain maintaining a presence “east of Suez,” the latter argument was particularly powerful. Wilson would hold to this line – steadfast refusal to commit British troops to Vietnam while providing firm diplomatic support – throughout the American military escalation in 1965–6 when such US demands reached a fever pitch. Matthew Jones has argued that by “closing down the option of a more active British involvement in … Vietnam during 1964–1965, Indonesian policy … may have saved Britain from a far more costly exercise … in the jungles of Southeast Asia.”Footnote 30

Wilson’s initial positive encounter with Johnson may have led him to believe he had more sway that he in fact did. When he grew concerned by the dramatic escalation of the conflict in early 1965 in the aftermath of the Pleiku attack, Wilson called Johnson, offering to visit Washington for consultations. Concerned that the visit would lend publicity to his own growing military involvement in Vietnam, LBJ angrily rejected the proposal, telling Wilson that “I won’t tell you how to run Malaysia and you don’t tell us how to run Vietnam.”Footnote 31 As Logevall has argued, Johnson was by then too committed to escalation and military victory to listen, not to speak of seriously engaging with British cautions.Footnote 32 Wilson’s persistent refusal to send British troops to Vietnam notwithstanding, the British government continued to lend public support to the American war effort. This was not empty rhetoric, as John Young has pointed out: British support included considerable overt and covert assistance, ranging from educational, agricultural, and technical aid to Saigon to arms sales, the training of South Vietnamese troops, and the availability of ports and airfields in Hong Kong and Thailand for US military use, freeing up US military capacity to devote to the war effort. After the BRIAM was withdrawn in 1965, British police advisors supported the RVN’s civil police. The British government also provided human and signals intelligence through its consulate in Hanoi and the monitoring of military and diplomatic communications through Hong Kong. A number of British soldiers and Special Forces members joined the war privately (by serving in the Australian and New Zealand forces deployed in Vietnam).Footnote 33

Wilson’s balancing act in the Vietnam War took place against Britain’s shrinking economic wealth and growing dependence on the United States, a process at play since the end of World War II, now aggravated by the conflict in Southeast Asia. The Confrontation deepened a sense on the part of many Britons – foreign policy elites and public alike – that the country had been overextended as a global power.Footnote 34 Chronic balance-of-payments deficits (since the late 1950s) weakened the British pound, the second reserve currency for the international monetary system. Recurring “sterling crises” beginning in late 1964 would lead Wilson – much to the Americans’ consternation – to contemplate the devaluation of the pound and to seek substantial reductions in defense spending.

Perhaps the most controversial question regarding Wilson’s support for LBJ’s Vietnam policy is what Young has framed as the possibility of a “Hessian Option”: a deal in the summer of 1965 by which the Americans helped to stabilize sterling in return for the British government’s commitment to more stringent economic policies, to maintenance of its bases “east of Suez” and support in Vietnam. Such a “mercenary deal” might have been advocated by some within the Johnson administration, especially Johnson’s national security advisor McGeorge Bundy, as the administration went to rescue the pound through a large international credit. But, as Thomas Schwartz has argued, “although the Americans insinuated a general link between their support for sterling and British defense policies, they stayed away from any direct connection to Vietnam.”Footnote 35 In fact, after the Confrontation was called off in 1966, Wilson followed through on deliberations to plan for an accelerated military withdrawal from Malaysia and Singapore. Despite continued American reservations, Wilson also went through with his decision in 1967 to devalue the pound in an effort to strengthen Britain’s trade balance.

Despite his public support, privately Wilson grew more skeptical of the American war in Vietnam, eventually harboring grave doubts about US capacity to achieve military victory. Wilson worried that the war posed a “real danger of the moral authority of the United States diminishing very sharply.”Footnote 36 Even Wilson’s public support was not without limits: he had his foreign secretary Michael Stewart seek an apology after the Americans announced the use of poison gas in Vietnam in March 1965. A year later, in June 1966, Wilson officially “dissociated” himself from the broadening of the systematic bombing campaign to include oil installations around North Vietnam’s population centers in Hanoi and Hải Phòng, Wilson’s only public break with the Johnson administration over Vietnam.Footnote 37 The American escalation in Vietnam in early 1965 led Wilson to give greater thought and energy to various mediation efforts: the Commonwealth Peace Mission in June 1965, the Harold Davies Peace Mission, and the “Sunflower talks” initiative in 1967.Footnote 38 Not only would any successfully negotiated settlement in Vietnam lessen the risks of being dragged into a war with China, it would also allow the British prime minister to reassert British international leadership. Wilson’s repeated efforts to mediate peace talks as an “honest broker” fell flat, however, hampered either by his closeness to the Johnson administration or by a lack of coordination with Washington (even when, as was the case in late 1967, Johnson solicited Wilson’s help). The British prime minister seems to have continually overestimated his ability to serve as an effective go-between with the Soviet government. Wilson’s various peace feelers failed to produce an early, negotiated end to the war.

Scholars have debated to what extent domestic political calculations motivated Wilson’s mediation efforts: such efforts would appease the growing number of Vietnam critics on the backbenches of the Labour Party which, by the mid-1960s, still held on to the idea of an independent, even internationalist foreign policy, with sections of the party remaining wedded to the notion of the UK as a “third force” in the Cold War system.Footnote 39 William Warbey, Labour MP for Ashfield, had pressed Conservative ministers in the House of Commons on the Vietnam issue as early as March 1955. When, following Operation Flaming Dart, the retaliatory airstrikes in response to the Vietnamese attack on the American air base at Pleiku, Foreign Secretary Stewart rejected calls to reconvene the Geneva Conference, some fifty Labour MPs demanded that the British government secure a ceasefire and political settlement in Vietnam. Later that month Wilson issued a statement that his government had been “actively engaged in diplomatic consultations of a confidential nature,” the results of which would be prejudiced by any “premature public announcement.” Hints at secret diplomatic efforts “became one of Harold Wilson’s key pieces of armour against attack” by his critics, including those within his party and cabinet.Footnote 40

A substantial number of Britons supported the US war in Vietnam in the early 1960s, but public attitudes shifted in the wake of the US escalation: in April 1965, Gallup polls found that for the first time a majority of the public disapproved of American actions in Vietnam (though other polls suggested continued support). US escalation also catalyzed the rather scattered antiwar protests, many of which built on the activities of existing peace and disarmament groups, such as the communist-leaning British Vietnam Committee (BVC) and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), known for its nonviolent protest marches. In May 1965, leftwing activists launched the British Council for Peace in Vietnam (BCPV) which was to play a central role in transforming the protests into a coordinated movement. An umbrella organization for some twenty-nine religious, labor, and political anti–Vietnam War groups, the BCPV advocated for peace in Vietnam on the basis of the 1954 Geneva Agreements and called on the Wilson government to dissociate itself from the American war, focusing in particular on its growing humanitarian and moral costs. “Once BCPV members realised that the war was not going to end quickly, they adopted a formal constitution, a council with officers, held regular meetings, circulated a news bulletin, established working groups and local subgroups, and planned a range of fundraising and protest activities to ensure the British and American governments were aware of the growing dissent and to further encourage that dissent, including teach-ins, torchlight processions, an on-going vigil at the US Embassy, pageants, and a ‘knock on a million doors’ campaign to get protest signatures.”Footnote 41 In July 1967 the BCPV organized a 7,000-strong rally in Trafalgar Square, indicating a level of mass discontent with Wilson’s Vietnam policy.

Dissatisfied with the more traditional BCPV campaigning, more radical activists founded a new and influential antiwar group in the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign (VSC) in January 1966. Partly sponsored by the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation and formed by the Trotskyist International Marxist Group, the VSC sought to mobilize support for an NLF victory. In its heyday, the VSC organized two major demonstrations in Grosvenor Square: Some 10,000–25,000 protestors gathered under its auspices on March 17, 1968. An even larger rally counting more than 100,000 demonstrators on October 27, 1968, seared itself into public memory with its dramatic television coverage of the ensuing violence. By now, British protests had become part of a transnational worldwide anti–Vietnam War movement: demonstrations in London, for example, had accompanied the October 1967 march on the Pentagon. The site of the first session of the International War Crimes Tribunal in November 1966, which had been established at the initiative of prominent polymath and pacifist Bertrand Russell, London came to be seen as a “major centre of global opposition” to the Vietnam War.Footnote 42

Despite widespread moral unease with US warfare in Vietnam, the British antiwar movement failed to shift public attitudes effectively against the war; polls of critical attitudes consistently peaked barely past the 50 percent mark and waned in the later years of the war. With public opinion on the war at an equilibrium, the most formidable opposition to Wilson’s policies arose within the cabinet and among Labour MPs. Labour MP Michael Foot later remembered the “blaze of anger” about Vietnam that “swept through the Parliamentary Labour Party” after the beginning of the sustained bombing of North Vietnam and early revelations of US napalm use. Labour and Liberal MPs soon became involved in the antiwar movement. Dissent about Wilson’s public support of the Johnson administration’s military intervention gained strength on Labour’s backbenches, especially after the party’s gain of some ninety-six seats in the March 1966 elections freed intra-party critics from risking government defeat in Parliament. More moderate Labour MPs joined the party’s left wing in pushing the government to actively pursue an end to the war. Vietnam featured prominently in foreign affairs debates in the House in June and July 1965; more than 300 questions were asked in the House over the course of the war.Footnote 43

Yet to what extent the intra-party opposition affected Wilson’s Vietnam policy, even the extent to which it dominated cabinet meetings, remains controversial. At no time did the majority of Labour MPs split with Wilson over his support of the US involvement in Vietnam, despite strong opposition within Labour’s traditional power base among trade unionists. According to Young, Vietnam did not play a major role in cabinet meetings either, and “few ministers were prepared to press their opposition very far.” While his critics at Labour’s annual party conventions in 1966 and 1967 voted down several of Wilson’s foreign policy stances, including Vietnam, these resolutions tended to affect the government only marginally. With “compromise and manipulation,” Wilson effectively managed his critics at the more important meetings of the Parliamentary Labour Party whose members, for all their criticism over Vietnam, did not want to see Wilson ousted.Footnote 44

Caught between alliance loyalties and economic dependencies, and increasingly critical attitudes within the Labour Party and the British public, Wilson charted a middle course on Vietnam – broad but not unlimited public support for Johnson while refusing to send British troops into the fight and pursuing a variety of peace initiatives. With Johnson’s March 31, 1968, announcement not to seek reelection and to limit Rolling Thunder bombing, Wilson’s active role on Vietnam came to an end. Traditionally more favorably disposed to United States involvement in Vietnam, the Conservative government of Edward Heath (1970–4) continued to lend verbal support to President Richard Nixon’s Vietnam policies, “cautioning against an early withdrawal from Vietnam.”Footnote 45

West Germany: Strategic Support

While British prime minister Wilson publicly supported Johnson’s Vietnam War out of broader alliance calculations, West German chancellor Ludwig Erhard embraced the American stake in Vietnam as intrinsically related to his country’s most vital security interests. “Viet-Nam was important to most Germans because they regarded it as a kind of testing ground as to how firmly the US honors its commitments. In that respect, there existed a parallel between Saigon and Berlin,” Erhard told Johnson in June 1965.Footnote 46 For Erhard the US intervention in support of South Vietnam was both imperative and reassuring: if Washington was ready to defend Saigon, it would do so for West Berlin, the strategically embattled Western outpost in Europe’s central Cold War battleground.Footnote 47 To many Germans Vietnam therefore initially stood as a symbol of American commitment to its allies. It would, however, not take long before Vietnam became a metaphor for the opposite: the weakening credibility of US defense commitments to Europe.

For Erhard, as for many Germans, the Saigon–Berlin analogy captured more deeply held convictions. As recent ideological arrivals in the “Free West,” Wilfried Mausbach has argued, Germans had “internalized the bipolar certainties of the East–West conflict” and viewed decolonization, including the developments in Indochina, through a Cold War lens. Unlike the French and British, who employed the Cold War frame to engage the United States in Indochina in the early 1950s, then came to question the extent to which Cold War analogies applied to the conflict, Germans embraced Vietnam within the dualistic framework of the Cold War. “No country was more closely attached to Vietnam than Germany,” Erhard told Johnson, “even if it lay far away geographically.”Footnote 48 In several interviews in the wake of his June 1965 meetings in Washington, the chancellor made clear that he had embraced as his own Washington’s “domino theory” arguments in favor of holding the South Vietnam “outpost”: otherwise “a communist bridge could reach from the Chinese mainland all the way to Australia.”Footnote 49

Beyond the Cold War optic, for Erhard support of the allies’ intervention in Vietnam was grounded in a “moral imperative”: in a letter to Johnson in May 1965, the West German leader reassured LBJ that it was simply impossible for the Federal Republic to refuse its moral support to the United States anywhere in the world. He particularly appreciated, Erhard confided to Johnson, that the American president’s stance was grounded in moral responsibility.Footnote 50 Despite growing objections at home to US escalation in Vietnam, Erhard avoided any public criticism of the Johnson administration, arguing that it did not behoove Germans to act as “teachers of morality in world affairs.” On the contrary, the chancellor continued to insist publicly on maintaining “solidarity in spirit” with the American effort in Vietnam.Footnote 51

To be sure, there was also an instrumental nature to Erhard’s outspoken political support for Washington on Vietnam: it was part of his determined effort to restore close ties with the United States.Footnote 52 His predecessor, Konrad Adenauer, who had steered the Federal Republic’s integration with the West under American leadership since 1949, had by the early 1960s become vocally skeptical of the US war in Vietnam (telling visitors “Vietnam was a disaster”)Footnote 53 and had come to support de Gaulle in his conflict with Washington. Once he succeeded Adenauer in October 1963, Erhard prioritized restoring close West German–American relations, convinced that the United States was vital to the Federal Republic’s security, national reunification, and identity: “Without the US,” Erhard told Secretary of State Rusk shortly after he took office, “Germany would be lost.” Reassuring the Americans of his support for their objectives in Vietnam was part of his goodwill offensive. Within days of his election to the chancellorship, Erhard stepped forward to recognize the newly installed military junta that had taken power in Saigon. In the volatile days after the bloody coup against Diệm that it had helped engineer, the Kennedy administration was eager to see Bonn spearhead efforts to shore up international support for the regime of General Dương Vӑn Minh. Internally, the German officials harbored reservations about the new South Vietnamese regime and misgivings about its long-term stability. Nonetheless, Bonn opted for immediate recognition and, in another sign of support, extended DM 15 million in credit to South Vietnam the following month.Footnote 54 Meeting Johnson in June 1964, Erhard assured LBJ that “Germany stood ready to do all that could be done economically, politically and financially.”Footnote 55

American demands for German military support in Vietnam increased as the Johnson administration set course for an all-out military intervention. In the context of the More Flags initiative, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara pressed the Erhard government in May 1964 to deploy a field hospital to Vietnam. In December 1965, Johnson confronted Erhard personally over the lagging German deployment, insisting that the chancellor could get “two battalions” to Vietnam: “If we are going to be partners, we better find out right now.”Footnote 56 (Later requests called for a German “construction battalion.”) For all his vocal support of US efforts to maintain South Vietnam as a bulwark of the “Free World” in Southeast Asia, deploying Bundeswehr soldiers of any kind was a bridge too far even for Erhard. The chancellor stated in May 1964 that it was “out of the question that a single German soldier will touch the ground there.”Footnote 57 The chancellor’s rejection of repeated US demands for German troop deployments in Vietnam reflected a basic consensus among West German leaders – and within the German public – that for historical reasons the Bundeswehr should not be deployed outside NATO. According to polls, some 88 percent of West Germans rejected sending German troops to Vietnam.Footnote 58

In addition, military aid of any kind had become a sensitive issue for West Germans. In early 1965 leaks about secret West German arms deliveries to Israel had led to a spectacular diplomatic defeat by the Federal Republic when in response to the revelations Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser invited East German leader Walter Ulbricht for a friendship visit, undermining West Germany’s long-standing diplomatic boycott of the East German regime, then threatened Bonn with a diplomatic break imposed by Arab countries, causing the federal cabinet to resolve to abstain from further arms deliveries in crisis regions. Faced with outrage from the Israelis and Americans, Erhard opted to recognize Israel, leading in turn to a break in relations with the Arab world. This abysmal experience led the leader of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) parliamentary group, Rainer Barzel, to declare at a party convention in April 1965 that a German response to demands for military aid must derive “from the situation of our country, from our history with its burden, from our division with its repercussions and from our political goals, self-determination of all Germans.” In light of the debacle in the Middle East, German military aid to Vietnam seemed even less desirable.Footnote 59

With his strident use of the Saigon–Berlin analogy and verbal support of Johnson’s Vietnam policy, Erhard occupied a hardline position within the governing party. Many of his fellow party officials worried about weakened US leadership in Europe because of the Southeast Asian entanglements. A swelling number of foreign policy officials grew increasingly doubtful that the Americans would succeed militarily in Vietnam. Christian Social Union leader Franz Josef Strauss declared as early as November 1964 that he no longer considered a military victory in Vietnam possible, leaving a political solution as the only resort. Growing skepticism even within the Atlanticist faction of the CDU about the real situation in Vietnam was evident when no less than the German foreign minister Gerhard Schröder noted at a NATO meeting in the aftermath of the US intervention in the Dominican Republic in April 1965 that he trusted that the Johnson administration had solid information on the civil war there and that the measures taken were “justified by the actual circumstances.”Footnote 60

By contrast, by 1965 the oppositional Social Democratic Party (SPD) had shed its early ambivalence toward the United States to embrace close ties with Washington and therefore seemed bent on outdoing the Erhard government on Vietnam. Willy Brandt, West Berlin’s lord mayor who had become the SPD leader, was among the first to confront the issue when, during the Berlin Crisis in 1961, Rusk had queried him about parallels between Berlin and Southeast Asia (though the focus then was on Laos). For Brandt, criticizing the West’s foremost protective power in divided Berlin over its growing involvement in Vietnam was out of the question. For several years he remained silent on the Vietnam War. Like Erhard, Brandt felt that Germans could not claim to be “teachers of world politics.”Footnote 61 He knew little about Vietnam, in what amounted to cognitive blinders – “an inner thought taboo,” as he put it in retrospect.Footnote 62 Other leading SPD foreign policy lights such as Helmut Schmidt and Fritz Erler shared his attitude at the time. Schmidt held that “indirectly vital interests of the remaining NATO partners were at stake” in India, Southeast Asia, and the Far East; the Europeans had to show understanding of this larger context of US foreign policy. Beneath the surface of seemingly limitless verbal support for the United States’ Vietnam intervention, however, the SPD leaders harbored concerns about the growing escalation of the conflict and therefore welcomed Johnson’s “Peace without Conquest” speech in April 1965. After meeting with Johnson and Rusk later that month, Brandt and Erler publicly expressed their “moral support for President Johnson’s firmness and determination to bring about peace with freedom in Southeast Asia.”Footnote 63

Bonn’s only tangible “deployment” to Vietnam came in the spring and summer of 1966 when the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) finally authorized and dispatched a Red Cross (not Bundeswehr) hospital ship, the SS Helgoland, complete with crew, to aid the civilian population, calling port in Saigon and Đà Nẵng. Given growing doubts about the viability of the South Vietnamese regime, Bonn emphasized the humanitarian nature of its aid to the RVN. It also viewed “quiet” economic aid to South Vietnam as a more appropriate and effective contribution, part of a broader foreign policy strategy of leveraging the Federal Republic’s growing economic might.Footnote 64 FRG officials were thus far more receptive to American requests in 1965 for support for a Southeast Asian Development Bank, though they pledged far less than the Johnson administration had hoped for. West Germany did extend multimillion-dollar credits to the RVN (including for the delivery of a modern slaughterhouse), eventually supplying assistance averaging $7.5 million annually between 1967 and 1973.Footnote 65

Far more important than direct aid to Vietnam were German efforts to use its economic prowess to mitigate against the repercussions from the growing American military engagement in Southeast Asia for US troop presence in Germany. American demands for greater shares by its European allies in shouldering the burden of fighting the Cold War had beset transatlantic relations since US balance-of-payments deficits had opened up in the late 1950s. US military commitments in Europe had contributed significantly to ballooning deficits and the drain on US gold reserves, and both President Dwight D. Eisenhower and President Kennedy had been frustrated by what they viewed as lackluster contributions by their NATO allies. In 1961 the Federal Republic had agreed to offset US outlays for the American troop presence in Germany by procuring American-made weaponry, essentially recycling the troop dollars streaming into Germany. The “offset agreement” had helped to stabilize the US troop presence in Germany and spared the Federal Republic from initial US troop reductions implemented elsewhere in Europe.

As the deepening engagement in Vietnam aggravated the budgetary shortfalls for the Johnson administration, West German offset payments took on a more important role. Johnson had reminded Erhard of the significance of the West German defense procurement as early as the latter’s first visit to LBJ’s Texas ranch in December 1963. Erhard had assured the president in turn that Germany would continue the current practice through 1967. During the rapid expansion of the Bundeswehr, transatlantic agreement on these offset purchases had posed few problems. But, as the Bundeswehr buildup subsided by the early 1960s, the German side found placing military contracts in the United States more difficult, in part because US offerings were driven by the US defense industry’s export priorities, not German needs. Compounding the problem was the onset of the first major postwar recession in the Federal Republic in late 1964, forcing Erhard, the father of Germany’s postwar “economic miracle,” to cut government spending. Erhard assured the irritated US president in December 1965 that he would honor the commitments but would need to balance his budget first. By mid-1966, German purchases for the US military equipment lagged considerably behind schedule for the 1965–7 agreement. With LBJ questioning German alliance obligations, in May 1966 Defense Secretary McNamara insisted that the existing agreement be fulfilled and negotiations for a new agreement commence without delay, threatening the withdrawal of portions of 7th Army from Germany.Footnote 66

The Vietnam War aggravated other foreign policy dilemmas for Erhard as well. In the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Washington began to search for some kind of détente with the Soviet Union, worrying Bonn officials that German security interests would become less of a priority. The growing military involvement of the United States in Vietnam pushed American initiatives in Europe, including the Multilateral Force (MLF) agreement (envisioned as a way for Germany to participate in NATO’s nuclear decision-making)Footnote 67 and the German unity question, further to the political backburner. By heightening Franco-American tensions, the conflict in Vietnam also complicated the tightrope that Erhard was trying to walk between maintaining allegiance to Washington and preserving close relations with Paris. With China as a major factor in the war’s rationale, the Johnson administration quickly squelched efforts within the FRG’s Foreign Ministry to rethink its China policy in the months after the French recognition of the PRC. Bonn officials were intrigued by PRC foreign minister Chen Yi’s suggestion of a trade agreement that played to West German business interests and notably held out the formal inclusion of West Berlin in the pact, undermining Soviet “three-state policy” that claimed a special status for the Western half of the city. Confronted with unexpected opposition by Washington, Erhard quickly disavowed the initiative. More generally, Germany’s political class grew increasingly wary that with American focus fixed on Southeast Asia, US support for restoring Germany unity was waning, in particular that “the US at this time was ostensibly not prepared to put pressure on the Soviet Union.”Footnote 68 The United States’ Southeast Asian diversion created a “crisis of confidence” in West German–American relations but it also may have spurred new thinking among German leaders about pursuing national unity.Footnote 69

The challenge of balancing the American connection with that with France also reverberated into domestic politics, where Erhard found himself squeezed between the “Gaullist wing” of his party, led by the ever more stridently critical Adenauer, on the one hand, and the Social Democratic opposition on the other. The Johnson administration’s abandonment of the Multilateral Force project by the end of 1964 and the start of negotiations toward a nonproliferation treaty in early 1965 tended to undercut the “Atlanticist” supporters of the American alliance (and American involvement in Vietnam) within the CDU. McNamara’s “shockingly high-pressure sales techniques” in the discussion over the offset agreements created outrage within the CDU, further narrowing Erhard’s political base. In addition to supercharging key foreign policy challenges for Erhard, the Vietnam War also undermined a key pillar of his authority as he faced mounting domestic and international problems: the chancellor’s personal relationship with Johnson. A Washington trip by Erhard in September 1966, frustrated by the war’s impact on nearly every agenda item and widely panned in the German media, contributed to, and may have been the final straw in, the fall of Erhard’s government in October.Footnote 70

The Great Coalition government led by Chancellor Georg Kiesinger and Foreign Minister Willy Brandt (1966–9) and then the SPD-led government under Brandt after 1969 continued Bonn’s verbal support for US efforts in Vietnam, though more cautiously and quietly than Erhard’s, in what was internally framed as “solidarity evinced with restraint.” Attitudes within the SPD in particular were evolving: after Washington trips by Brandt and Erler in the spring of 1966 the SPD leaders – while still voicing support for Johnson – returned with a more nuanced sense of the conflict and began to reject simplistic analogies between Berlin and Vietnam. The party began to engage in a difficult balancing act to retain the US administration’s support (which was deemed to be critical for the party’s rise to power): avoiding a disavowal of its US ally while keeping the country at arm’s length. A case in point, the party leadership effectively sidelined discussion of the issue at the Dortmund Party Convention in June 1966 despite the growing resonance of the Vietnam topic among party youth and local chapters. It would take another two years before Brandt – now foreign minister of the Great Coalition – would convey his party’s concern over the war and urge the Johnson administration to seek peace. But even as chancellor (1969–74) Brandt continued to hold back public criticism of US actions. He supported US incursions into Cambodia in 1970 as a means to a “just peace,” even as he urged Washington to negotiate, and stayed silent when the Christmas bombings in December 1972 caused a new wave of criticism and protest around the globe. Much like his predecessors, Brandt justified his “painful” silence as prioritizing West German security interests, in particular the pursuit of Ostpolitik and disarmament in Europe. Only much later would Brandt concede that “in reality our loyalty to the West and our sense of the balance of power went so far that we remained silent on the Vietnamese tragedy, despite the fact that there was no lack of better knowledge and that such self-censorship came at the price of our credibility.”Footnote 71

The Vietnam War increasingly permeated domestic discourse and politics in Germany. Public opinion in the Federal Republic began to shift, albeit slowly; in March 1966, polling showed that only 44 percent of West Germans still viewed the US struggle in Vietnam as defending freedom against communism, with just a quarter of those polled arguing that the United States had no right to be there. Two years later, some 60 percent of West Germans disapproved of the US military campaign in Vietnam, with some 42 percent believing that American soldiers were committing atrocities.Footnote 72 Major antiwar demonstrations did not occur until fall of 1965. Building on the Easter March peace campaign against nuclear weapons, pacifist and humanitarian currents initially prevailed in the rather heterogeneous groups that comprised the early anti–Vietnam War protests: they focused on bringing about an early end to the fighting and a return to the 1954 Geneva Accords. By 1966, New Left groups led by the Socialist German Student League (SDS) had started to gain influence within the movement. For the SDS, the war in Vietnam became “one of the central mobilizing and radicalizing issues.”Footnote 73 The SDS and other more radical groups aimed not just at bringing about an end to the war (and the Federal Republic’s colluding role): many came to see themselves as part of a globally connected revolutionary alliance that viewed the Vietnam War as the product of Western cultural imperialism and considered the North Vietnamese struggle part of an international struggle against capitalism. At home, the antiwar struggle was linked to the broader agenda of the Extraparliamentary Opposition in which SDS came to play a leading role: opposition to the government’s plan to install emergency laws, a push for democratic university reforms, and a broader leftist critique of the Federal Republic’s political system.

West Berlin became the most notorious staging ground for anti–Vietnam War protests in Germany (competing with Frankfurt, home to the “Critical Theory” school that provided the intellectual foundation for New Left critique and activism). A frontline city in the Cold War, formally still under Allied rule, by the mid-1960s West Berlin pitted a fiercely anticommunist establishment and population, symbolized by the conservative Springer publishing house, against “draft dodgers seeking immunity from military conscription and radical instigators searching for an ideal stage on which to mock the pieties of Cold War anti-communism.”Footnote 74 This “extreme division of the social milieus” in West Berlin produced some of the most powerful early antiwar protests but also some of the most violent clashes. Led by the charismatic Rudi Duschke, a more radical “anti-authoritarian” faction within the SDS Berlin that would soon dominate the national SDS, it launched the so-called poster protest in February 1966, a “direct action” in the course of which they plastered some 5,000 anti–Vietnam War posters across Berlin. Posters attacked Erhard for supporting “murder through napalm bombs” and proclaimed that “taking up arms” was the only remaining option for oppressed people from Vietnam to Cuba and Congo. In Berlin as elsewhere, protests and demonstrations often aimed at United States military and cultural institutions, which were seen as representing “American imperialism.” In a pointed reversal of the Saigon–Berlin linkage employed by Erhard, the antiwar protestors now linked up in solidarity with North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front: “Every victory for the Viet Cong means a victory for our democracy.”Footnote 75 In a high point of the anti–Vietnam War activism in West Germany, the International Vietnam Congress, organized by the SDS at the Technical University of Berlin in February 1968, gathered 5,000 participants and concluded with 12,000 protestors marching through the streets of Berlin (facing a police force of 6,000 officers). The antiwar movement in the Federal Republic crested soon after. The ratification of the emergency laws in May and the beginning of the Paris Peace Talks on Vietnam, as well as incessant infighting, caused the SDS-led national movement to lose its luster as it disintegrated into various local and ideologically diverse splinter groups.

Conclusion

The United States’ European allies reacted to the Vietnam War in starkly different ways – and yet they came to agree on several fundamental assumptions: that the US intervention in Southeast Asia had the potential to endanger Western Europe’s security, that it could not be won on the battlefield, and that they would not be drawn into it militarily. In contrast to their American ally, they came to view it as a conflict that more and more defied Cold War definition. To them, the conflict increasingly risked “losing the Cold War on the domestic front”Footnote 76 as it exacerbated political tensions at home, as European publics and in particular a new generation turned against the war, and as leftist oppositions instrumentalized “Vietnam” for a more radical systemic critique. Did a growing transatlantic gap of what constituted the geopolitical and moral character of the “West” lurk behind the dissonance on Cold War logics, on the reliance on escalating military might, and on accepting the tragic humanitarian consequences of the war? In the short term, Cold War (and post–Cold War) realities in Europe, and the remarkable resiliency and transformation of the broader institutional framework of the transatlantic community, covered up, bridged, and possibly overcame the rift caused by the Vietnam War. Its long-term consequences for the transatlantic West have perhaps yet to play out.