This cancer of the mind … consists of thinking all too sadly that certain things “are,” while others, which well might be, “are not”

The outbreak of the highly pathogenic viral infection caused by SARS-CoV-2, popularly known as Covid-19, was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020. Within days of this announcement, many countries focused exclusively on containment, treatment, and prevention among their respective populaces, quickly shuttering their national borders; implementing travel restrictions and lockdown measures; and rolling out social distancing, quarantine, and isolation guidelines. The Cuban Government implemented similar measures at home, and, confident in its strategic investments in its public healthcare system for over half a century, simultaneously embarked on another project on a global scale.

Armed with biomedical knowledge and technical expertise, on March 22, the island nation sent the Henry Reeve Medical Brigade, comprising thirty-six doctors, fifteen nurses, and additional logistics specialists, to Italy’s Lombardy region. Italy had already reported 54,000 confirmed Covid cases and 4,825 related deaths. The all-too-familiar scene of arrival, a dramaturgy of Western-styled humanitarianism, captured headlines: an army of white lab coats unloading boxes of supplies, rapid deployment of medical tents, and staff poised to deliver much needed aid in a time of crisis. Under the rare glare of the global media spotlight, the Cuban humanitarian brigade of fifty-two doctors and health workers established a field hospital alongside the Crema Maggiore Hospital in Milan (see Figure 15.1). As dubbed by the media, the “army of white coats,” this scene became note- and newsworthy in no small part because of the actors involved, who inverted geopolitical, racial, and gendered hierarchies.Footnote 2 The subtext: Italy, the third wealthiest country in the European Union, struggling to manage the exponential number of coronavirus cases and a mounting death toll in the early phase of the pandemic, requests biomedical expertise from a middle-income Caribbean country. The reversal of roles of protagonists, experts, heroes, and victims that traditionally characterize Western humanitarianism and capital flows from North to South set the stage for a theater of the absurd, with a surrealist script of an illogical plot.

Figure 15.1 Cuban and Italian doctors meeting in Turin, Italy, to combat Covid-19.

What makes this scene absurd, as the media spectacle revealed, is that the common sense of humanitarianism naturalizes certain geopolitical actors performing scripted roles of the donor (Global North) and the recipient (Global South). The illogical, or the presumed implausibility of Cuba as a principal actor in global health, disrupts the imperial gaze of humanitarianism. Such a gaze reasserts colonial legacies of empire, invoking racialized constructions of people, places, and things. Rather than analyze this as a residual artifact of history as incidental, Adia Benton stresses, this is a “foundational aspect of how humanitarianism functions.”Footnote 3 Indispensable work at the intersection of global health and humanitarianism has produced a rich analytic vocabulary to denaturalize the seemingly apolitical global health industry.Footnote 4 As a humanitarian apparatus claiming the right of intervention and interference beyond sovereign borders, global health functions as a biopolitical regime, in and through competing claims on who has duties to whom and why. Fine-tuned ethnographic studies have unraveled parts of this assemblage, including the methods, assumptions, financing, and political inner workings.Footnote 5 In so doing, these studies demonstrate how interventions, including biomedical technologies (from pharmaceuticals to health learning campaigns), are tethered to notions of standardization, economic theories of development, conditional trade agreements, and militarism.Footnote 6

Still, what remains out of view, or to see without seeing, is the inequality built into the very design of this assemblage, coded into its DNA. Global histories of violence and subjugation, epistemic and otherwise, continually reproduce and solidify the same actors (e.g., the definition of problems, funding, and research solutions) and targets (e.g., subjects of the intervention) of this field. The assemblage moves along well-oiled paths, many long established since the beginning of European imperialist expansionism in the sixteenth century.Footnote 7 Decentering the dominant script of humanitarianism requires considering traces of other and often unacknowledged histories and political formations, experiences, and knowledge-production systems that might appear, at first, as peripheral to what has become legible as social medicine.

For example, since the Cuban Revolution of 1959, the socialist island nation, classified as a low-income country in the Global South, has invested considerable capital, labor, and infrastructure in developing a comprehensive medical program. This program includes accessible healthcare delivery integrated into an extensive, multitiered program of medical education, training, and advanced research in biotechnical innovation. Under the umbrella of medical internationalism, the country has imparted this biomedical expertise through mobile medical brigades dispatched to geographically diverse locales. Since the early 1960s, the government has sent over 400,000 medical brigades to provide short- and long-term healthcare in over 164 countries, more than all the G8 industrial nations combined. These brigades, engaged in “humanitarian biomedicine,” address acute and chronic lack of access to primary healthcare (and, to a limited extent, secondary and tertiary care) for historically vulnerable and underserved areas and populations.Footnote 8

Cuba has designed prize-winning primary healthcare delivery models, including tailored responses to controlling epidemics and developing innovations in vaccine production and experimental cancer therapies. In July 2021, Cuba became the first and only country in Latin America to successfully produce its Covid-19 vaccine, known as Abdala (Figure 15.2). The vaccine takes its name, Abdala, from a patriotic drama verse by José Martí, a heroic symbol of Cuba’s struggle for independence from Spain. The country is also home to the world’s largest medical school, the Latin American School of Medicine, which since 2005, has graduated tens of thousands of physicians from low-income communities in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, including the United States. Through this reshaping of economies of care, Cuba has garnered accolades for transforming the landscape and bodies in healthcare delivery in Latin America, the Caribbean, and several African countries. In scope, depth, and breadth, the magnitude of this brand of humanitarianism far outpaces the most iconic faces of the contemporary global health industry, such as Doctors Without Borders, the Red Cross, or UNICEF.Footnote 9

Figure 15.2 Abdala Covid-19 vaccine.

Despite brandishing these evidentiary forms of success, Cuba’s quest for global health equity occupies the margin or the subaltern in the global health landscape, even for a field that uncritically celebrates quantitative metrics.Footnote 10 For most observers in North America and Europe, Cuba likely occupies the rhetorical and discursive space of the singular case study or alternative, if it even makes an appearance. It is an outlier, a kind of exceptionalism marginal to mainstream discussions of global health equity; it is in the footnote or addendum of history, outside of central debates, or reduced to a compelling “theory from the South.” This positionality is often glossed as minoritized or identarian and is usually significant only in unveiling moral, political, economic, and affective attachments. Ultimately, such discourses circulate in the register of singularity, a local among taken-for-granted universals.

How do we understand the absence–presence of Cuba’s medical-internationalism efforts as a non-event in the contemporary global health landscape? This chapter extends and reformulates Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s incisive historical analysis of how the Haitian Revolution, even as it happened, was unthinkable.Footnote 11 This event, he argues, challenged “that which one cannot conceive within the range of possible alternatives which perverts all answers because it defies the terms under which the questions are phrased.”Footnote 12 As a thought experiment: what would it mean to engage seriously with Cuba’s approach to social medicine – moving it from the footnote to the main text? Notes toward a speculative answer shape this chapter. I examine the foundational assertations structuring contemporary global health – the problematics, concepts, methods, and practices – that render different imaginaries of care and aid legible and thus thinkable. Many of these assertions remain unchallenged, which include world making assumptions what Trouillot terms “North Atlantic universal fictions” (e.g., progress, development, modernity, nation-state, freedom, equity). More than discursive abstractions, Trouillot explains, such fictions operate as transcendental categories that “appear to refer to things as they exist, but because they are rooted in a particular history, they evoke multiple layers of sensibilities, persuasions, cultural assumptions, and ideological choices tied to that localized history.”Footnote 13

Drawing on more than two decades of extensive ethnographic research with Cuban health professionals, government officials, and everyday citizens, both in and outside of Cuba, this chapter approaches the discussion of Cuban social medicine as a form of speculative thinking, embracing possibility as an abstract noun – that is, the what-if – to provoke “political and ethical imagination in the present,” echoing María de Puíg de la Bellacasa work. She argues that this entails drawing out the “existential domains of care as something open-ended.”Footnote 14 To attend this way of seeing Otherwise requires developing an ethics of care, where ethics “cannot be about a realm of normative moral obligations but rather about thick, impure involvement in a world where the question of how to care needs to be posed.”Footnote 15 Such an approach demands cultivating an analytic “toward reading and seeing otherwise; toward reading and seeing something in excess of what is caught in the frame,” as argued by Christina Sharpe.Footnote 16 I commence with a snapshot of the centerpiece of Cuba’s current primary healthcare system, the neighborhood clinic. Since the early 1980s, this clinic has served as a site of heated debate on the country’s biopolitical project, wherein the plasticity of biomedicine, a term I unpack shortly, transforms, even distorts, the perceived rigidity of the biological and social body, and the body politic.

The Plasticity of Biomedicine

After her daily round of home visits, Dr. Ruiz,Footnote 17 flustered by the unrelenting humidity of August, was returning to her consultorio (clinic) in the early evening. My elderly neighbors, patients of Ruiz, introduced us in 2000. Our bustling residential block, la Plaza, comprising low-rise buildings and multi-level homes now converted into several apartments, was typical of this urban neighborhood a few miles west of the Havana city center. Ruiz, who lived in a small apartment adjacent to her consultorio, was a familiar face. She made her daily afternoon home visits to patients who required additional monitoring and care, accompanied by one of a rotating roster of nurses. On the day we met for coffee, two cases were worrying Ruiz. A young woman had missed her prenatal checkup and an older man lived alone with chronic health problems.

“I am like an annoying family member,” Ruiz joked as she discussed her patients, who were also her neighbors and friends. Most were accustomed to her cheerful nature, peppered with health promotion, education, and sometimes clinical interventions. Prenatal appointments are not optional, Ruiz asserted. The young woman’s missed appointment was a reason for concern. Slightly embarrassed by the impromptu visit, the young woman assured the doctor that the appointment had just slipped her mind. Ruiz used the opportunity to discuss the additional monthly rations from the local bodega of food and vitamin supplements allotted for the young woman’s pregnancy.

In Ruiz’s interactions within the neighborhood, she always skillfully balanced admonishing and encouragement, establishing a familial rapport with many of the people of la Plaza. The physician, in her mid-thirties and with a family of her own, was accessible and often the person people reached out to at all hours of the day and night, asking for the cause of puzzling physical symptoms, on-the-fly blood-pressure checks, and nutritional advice. Despite the hectic, fast-paced rhythm of the dense urban block, there was also a sense of community. People, even without regular direct engagement with one another on this chaotic block, quickly recognized new faces and noted absences. For Ruiz, already embedded in multiple familial webs of care and a nodal point in diverse therapeutic itineraries of individuals and families seeking advice and treatment, this tangled involvement in people’s quotidian lives was a defining feature of her medical practice.

Since 2000, I have researched the ethnographic intricacies of consultorios in and around the neighborhoods of Havana, scaling from individual health-related practices to the changing macroeconomic and political influences, some external to Cuba, shaping the country’s healthcare system. The consultorio in la Plaza is just one among thousands (in 2020, approximately 26,173) of similar community-based clinics scattered throughout the island, serving as the bedrock of Cuba’s primary healthcare system.Footnote 18 The Family Physician and Nurse Program (El Programa del Médico y Enfermera de la Familia, MEF), launched in 1984, called for physician-and-nurse teams to live and work in small clinics on the city block or the rural community they serve.

Each consultorio serves roughly 120 families (approximately 600–700 persons) in a designated health area. The design and structure of the MEF program are to provide greater access to healthcare services and a closer relationship between health teams and their patients. In the 1980s, Cuba’s health profile underwent an epidemiological shift. This shift from so-called diseases of poverty (e.g., parasitic and infectious diseases) to “diseases of development” (e.g., heart disease and cancer). With an increase in chronic health problems and cancers linked to multicausal factors, including lifestyle (e.g., smoking, diet, and physical activity) and psychosocial and economic considerations, the success of previous curative interventions achieved through pharmaceutical prophylaxis was out of sync with the country’s changing morbidity patterns. Faced with this new challenge, the Cuban Ministry of Public Health (MINSAP) overhauled the health system by training a new cohort of primary healthcare physicians. This pedagogical calibration would better equip physicians to carry out clinical and social-epidemiological vigilance of the population, promote health, and prevent disease by working with the community.

In 2023, almost forty years after its launch, the MEF program, with its mandate to train primary healthcare physicians, contributes to Cuba’s reigning status of having the highest physician-to-inhabitant ratio globally. Women constitute 61.7 percent of all physicians (from primary to tertiary specialties) and 71.2 percent of healthcare workers.Footnote 19 Women also form most physicians making up the brigades on humanitarian solidarity missions. Within the past decade, these solidarity missions have tripled in size, partly owing to the domestic success of Cuba’s integrated primary healthcare model, as measured by statistical indicators determined by multinational organizations. For example, the collection and circulation of nationwide vital health statistics by the WHO and World Bank form part of a complex standardization algorithm. The outcome is numerical snapshots of any country’s health and social welfare (especially vulnerable populations, such as infants). As a country with scarce economic resources and modest per capita total expenditures on health, Cuba has long leveraged the political semiotics of its vital health statistics (e.g., the country’s low infant mortality rate).

Physicians like Ruiz, paired with a nurse, offer a decentralized, neighborhood health(care)Footnote 20 model. As Cuba’s government contends, they have a more intimate knowledge of their patients from this location, always connected to the dynamic bio-psycho-social and economic factors that shape their lives. On any given day, Ruiz and a nurse were charged with administering four priority health programs: maternal and child health, chronic non-communicable diseases, infectious diseases, and the care of older adults. Through a classification surveillance system known as dispensarización or the classification and monitoring of epidemiological-risk categories, Ruiz would evaluate the overall health situation of her designated area and define the at-risk populations by a patient group – for example, hypertensive, diabetic, expectant mother, and so on. In addition to assigning a “risk group,” health teams, as stipulated by the MEF methodological manual, also qualitatively assess the socioeconomic factors of each household in three categories: cultural hygiene, psychosocial characteristics, and the provision of necessities. Thus, health teams can provide immediate, continuous, and tailored forms of care.

On the surface, Ruiz’s quotidian clinical practices may fit neatly within what most contemporary public experts, for example, the WHO, now defined as an attention to the structural determinants of health (SDOH), or addressing “the social, physical, and economic conditions that impact upon health.” However, a fundamental difference remains, that is, the question of praxis, linking theory and action or, in the words of decolonial theorist Catherine Walsh and Walter Mignolo, constitute a “praxis of living” where theory and the action “are enacted and, at the time, rendered possible.”Footnote 21 Health(care), defined through this framework, increasingly blurs the biological body as the site of medical intervention. In the twenty-first century, Cuba’s primary health(care) systems, such as Ruiz’s consultorio, which is the model that forms the basis of the solidarity humanitarian brigades, which I will discuss shortly, actively work to enact comprehensive, historically sensitive biomedical health(care). Here, SDOHs are an active component of the medical gaze, in no small part owing to the previous and ongoing transformations of social and political conditions that have radically altered the physical/biological bodies that medicine operates on and through.

More than sixty years after the Cuban Revolution, through the vagaries of radical economic setbacks, the country has remained steadfast in its commitment to address the historical reproduction of structural inequality, even if faltering at times.Footnote 22 While Cuba’s socialist economy is an analytic departure point from other studies of biomedicine, my specific aim is to examine how the country’s biomedical expansionism emerged in response to the structural and material conditions that gave rise to the 1959 revolution, which was an anti-imperialist movement focused on agrarian reform and ending racial and gender discrimination, predatory capitalism of economic exploitation and expendability, rampant structural inequality, and widespread corruption. Cuba’s variant of biomedicine is conscripted to serve as a revolutionary project and was conceived as a form of social medicine and reparative social justice.

Cuba’s philosophy of social medicine as political praxis approaches health as flourishing. By extension, care is or can be “the social capacity and activity involving the nurturing of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life.”Footnote 23 Through this, the practice of health(care) implodes the therapeutic boundaries of the consultorio, offering a generative space for reinterpreting biomedicine’s transformative properties or its plasticity. Plasticity, philosopher Catherine Malabou suggests, provides an interpretive lens for exploring the creative, annihilating, and transformative meanings of organic structures and systems of thought, including ideas, discourses, or practices. She defines plasticity as the capacity to give and receive from, and as plastique (the French term for explosive), the power to annihilate form. Malabou has applied this concept to think through organic material, such as theories of the brain, to open a field of possibilities for other ways of thinking about the human condition.Footnote 24 Here, I apply plasticity to biomedicine to draw attention to its potential as a therapeutic and transformative system of social justice, wherein the corporeal, social, and political bodies are sites of historical reparations. In other words, the reparative capacity of biomedicine can be molded and transformed to alleviate the enduring material and embodied legacies of colonialism, now magnified through global capitalism. Cuba’s biomedical focus on human health and, by extension, approaches to care are two sides of the same coin, configured as therapeutic and affective labor but also a political technology invested in creating the conditions for individuals, groups, and populations to flourish. As Cuba’s healthcare model travels through international medical brigades, social medicine becomes enveloped in solidarity praxis, producing unexpected and expected transnational alliances and adversaries.

Solidarity Humanitarianism As Reparative Justice

Cuba’s programs of solidarity humanitarianism, racially marked as the Global South, allow me to reframe the common sense of the affective and ethical bonds constituting attempts at global health equity. Here, solidarity here operates through several political valences that warrant closer examination. On the one hand, it is the provision of care as a response to acute suffering of humanity in post-disaster relief and, on the other, care as restitution to remediate what Lauren Berlant terms the quotidian “destruction of life, bodies, imaginaries, and environments by and under contemporary regimes of capital.”Footnote 25

The Henry Reeve Medical Brigade’s arrival in Italy forms a much longer, complex history of Cuba’s expanding approach to health(care) as political praxis. In late August 2005, Hurricane Katrina swept over southeast Louisiana and Mississippi, causing massive damage, particularly to New Orleans. The city’s levee system failed, unleashing massive flood waters, and leaving tens of thousands of people, primarily Black residents, stranded without food, shelter, power, or necessities. The US federal government’s response was slow and inept, exacerbating the magnitude of the disaster. Days after the storm made landfall, the Cuban government assembled 1,500 physicians with several tons of medical supplies and materials in Havana’s Convention Center. Then President Fidel Castro offered to dispatch them to the devastated areas along the Gulf Coast. Addressing the brigade of physicians, Castro explained his rationale: “It was clear to us that those who faced the greatest danger [in New Orleans] were these huge numbers of poor, desperate people, many elderly citizens with health situations, pregnant women, mothers and children among them, all in urgent need of medical care.” This duty to act, Castro asserted, was “writing a new page in the history of solidarity … showing a course of peace for the suffering and imperiled human species to which we all belong.”Footnote 26

After a week of slow deliberation, the U.S. Department of State finally responded by declining the offer, citing that the United States had no diplomatic relations with Cuba. Such ties were severed in 1962 when President John F. Kennedy proclaimed an embargo on trade between the two countries, which later expanded to a comprehensive economic blockade and severe travel restrictions. Undeterred by this rebuke, the Cuban government used the opportunity to inaugurate a medical emergency response team known as the Henry Reeve International Contingent Brigade Specialized in Disasters and Serious Epidemics (HRIMB). This newly formed eponymous brigade, an army of white lab coats, honors the New York-born Brigadier General Henry Reeve, who fought in Cuba’s Army of Liberation during the First Cuban War of Independence from Spain (1868–78). This act of naming transforms medicine, through the political semiotics of liberation and struggle, to Guevara’s commitment to building a cadre of proletariat physicians, or “revolutionary doctors,” who now, as internationalists (internacionalistas), “pledge to serve wherever they are needed.”Footnote 27

A narrative history of Cuba’s medical brigades through monumental events, such as their arrival in Italy or the army of physicians poised to assist after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, eclipses how emergency and disaster assistance has been a staple since the early 1960s of Cuban internationalism. For example, the first team of physicians was sent to Chile in 1960 after an earthquake. Other groups were dispatched throughout Central America and the Caribbean after hurricanes George and Mitch in 1998. In 1986, teams brought victims of the Chernobyl disaster to Cuba for treatment and rehabilitation. The HRIMB, then, is an extension of these efforts, which include the brigade’s collaboration with the WHO in controlling the Ebola epidemics in West Africa in 2014; humanitarian medical teams sent to Haiti after the 2010 and 2016 earthquakes; and, more recently, sending health professionals to thirty-nine countries to assist in their battles to manage Covid-19.Footnote 28

How, then, do these recent efforts write a new page in the history of solidarity? Since the 1960s, Cuba’s approach to solidarity, within a political-epistemological context, suggests the co-emergence of interrelated forms of solidarity worth disentangling. In one instance, solidarity – invoking the writings of Simon Bolívar, Che Guevara, Jose Martí, and Karl Marx – emerges from cooperation rather than development assistance or aid. This shift in language highlights the non-hierarchical relations of mutual trust and support, comradeship, or camaraderie. As Robert Huish has noted, this form of solidarity contradicts normative aid frameworks or the common sense of Western humanitarianism. The latter is rooted in charity, altruism, and a moral incentive to act.Footnote 29 Cuban solidarity brigades in a post-disaster context are a form of cooperation without political conditionality or material self-interest and do not retrain the conventional power imbalances implicit in the geopolitics of donor–recipient relations. Yet this history of solidarity as cooperation also intersects with the country’s humanitarian imperative through an explicitly political framework of social justice, rationalized as part and parcel of a form of ethics rooted in subaltern politics. This form of international solidarity resonates with the decolonization debates of the Bandung Conference of 1955, a meeting of twenty-nine African and Asian countries to discuss the global reconfiguration of power taking shape post-Second World War. As European empires collapsed, the US and USSR emerged as influential international figures alongside China’s Maoist revolution.

The formation of the United Nations in 1945 and the rise of Cold War factions between the US and USSR precipitated the founding of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1956. This movement sought a platform for the countries not aligned with these significant power blocs to discuss battles over national self-determination against all forms of colonialism and imperialism. Cuba’s Cold War alliance with the Soviet Union was also influential in importing the language of Soviet-style Marxist-Leninism into Cuba’s political discourses (e.g., proletariat internationalism). However, throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, the anti-imperialist and anticolonial leanings of Cuba’s active involvement in liberation struggles were evident in the military, technical, and medical realms. Participation in campaigns in Angola, Algeria, Bolivia, Congo, Grenada, and Nicaragua, among others, provides ample instances. Fidel Castro argued in the Second Declaration of Havana (1962) that these formative acts of solidarity, both military and medical, could not be reduced to the idea that “revolutions can be bought, sold, rented, loaned, exported and imported like some piece of merchandise.”Footnote 30 The revolution is not a commodity, Castro affirmed. Instead, it was a worldview centered on cultivating an ethics of humanity committed to ending exploitation and cycles of structural violence. Early political discourses of solidarity as struggle were present in the Tricontinental Conference hosted in Havana in 1966. With representatives from eighty-two countries spanning three continents, Castro asserted internationalism was about “strengthening the bonds of revolutionary and anti-imperialist solidarity in the battle against the imperialist, colonialist and neocolonialist system of exploitation, against which we declared a fight to the death.”Footnote 31

From medical brigades (e.g., Henry Reeves) to vaccines (e.g., Abdala Covid vaccine), the resignification of the transformative properties of biomedicine signals a complex, entangled history of solidarity in liberation struggles for self-determination. In Cuba’s post-Soviet era, solidarity humanitarianism moves beyond crisis as an exceptional event or emergency to an approach to crisis defined by the quotidian experience of multiple forms of structural violence. This new page of humanitarian intervention is focused more on capacity-building and strengthening primary healthcare infrastructure, training health professionals, and developing extensive South–South cooperation, concentrating on health, social welfare, and biotechnology. Solidarity, then, rather than an identarian project, is an activity that emerges when working together on a common task, cutting across presumed attributes such as class, nationality, or ethnicity, thus destabilizing the “reductive binarity of similarity and dissimilarity, as Fertherstone asserts.”Footnote 32

The postcolonial anxieties of Latin America reflect a unique set of historical concerns, incorporating the demographic richness and conflicts of the region. Yet it is clear from historical events – such as the emergence of the Non-Alignment Movement and centuries of liberation battles for self-determination, political sovereignty, and an end to exploitative economic relations – that Cuba’s approach to humanitarian solidarity crystallizes and addresses a shared set of geopolitical tensions. For an increasing number of populations, some even within the Global North, everyday life has become unlivable and shaped by exceptional poverty and the abandonment of care. As a form of solidarity, Cuba’s medical brigades are an experiment in “actually building new social relations that are more survivable,” following Dean Spade’s work on mutual aid.Footnote 33 This gesture is a form of restitution as care, acknowledging cumulative injuries of histories in the present and attempting to remediate the structural conditions that cyclically enact bodily harm.

For Cuban officials, developing an ethics of care as solidarity, as an ethos of cooperation, is part of the broader resignification of medicine in the country’s development of humanitarian biomedicine. Such strategies of care need to be adapted to confront the liberation struggles of the present day. The twenty-first century has given rise to unprecedented levels of global inequality, reordering previous colonial mappings. The increase of indirect and insidious forms of economic accumulation and dispossession, through neoliberalism, for instance, has hollowed out the social welfare state, resulting in unprecedented global inequity. How does Cuba’s approach to social medicine, as mobile technology, transform discursively and materially from a domestic to an international context through different social-economic and political contexts? What configurations of care are envisioned through Cuba’s explicitly politicized variant of solidarity humanitarianism? To demonstrate this, I turn for a moment to the historic agreement between the government of Venezuela (and President Hugo Chávez, d. 2013) and President Fidel Castro (d. 2016) to form the program “Inside the Neighborhood” in March 2003. This program, known as Missions, not in the religious sense but as a social justice project, was at the heart of Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution (named after anti-imperialist fighter Simon Bolivar). To do so, however, also requires that we contend with political contingencies, or, I will discuss, constraint, that is, on the one hand, an act or force that restrains and on the other, a condition, sense of the state of being restricted, or kept in check to avoid or perform some action, thought or way of life. It is an Otherwise, kept at bay.

Between Constraint and Possibility

After Hugo Chávez was elected president of Venezuela in 1998, a new alliance with Cuba gave birth to several bilateral and subsidized trade agreements (e.g., subsidized oil) between the two countries. Chávez’s populist political movement amended the constitutionality of access to health(care) as a priority for the newly formed Bolivarian government. However, this plan proved challenging to put into practice. After failing to secure Venezuelan doctors willing to live and work in underserved communities nationwide, with minimal healthcare infrastructure, the Chávez government turned to Cuba for support.

In March 2003, Plan Barrio Adentro, renamed Misión Barrio Adentro (MBA) in 2005, emerged from an agreement between Chávez’s government and Cuba as part of the larger project of redesigning the welfare state in Venezuela, funded petro-capital and formation of a hemispheric alliance known as ALBA, or the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America. ALBA was created as a decisive turning away from the Free Trade Area of the Americas, as a new day in politics, defined by an anti-imperialist, regional, and hemispheric united front against US interventionism and the logic of capitalist development. Moving against the 1990s trend of other Latin American countries, where neoliberal reforms and loan conditions of international financial institutions had curtailed state investments in healthcare, Barrio Adentro (Inside the Neighborhood) proposed a radically different model of care. With access to healthcare a constitutional right, the MBA model would seek the assistance of 20,000 Cuban physicians and auxiliary health professionals stationed in primarily poor neighborhoods in Venezuela to provide free medical care. In this context, “missions” (misiones), typically associated with Catholic or evangelical projects of conversion or with civilian or militarized mobilizations, take on new meaning within programs centered on antipoverty, social welfare, education, and social justice.

Since MBA’s emergence, the program has been subject to vigorous discussions, from declarations of it as a striking example of Latin American social medicine to criticisms of the oil-for-aid deal as a totalitarian form of humanitarian business For example, the summer of 2013 witnessed mass protests staged by private medical associations in Brazil over the intent of former President Dilma Rousseff’s government, which committed to a program of universal health coverage, to subcontract 4,000 Cuban physicians (with the hopes of obtaining 20,000) to work in rural, underserved outposts, through a program known as Mais Médicos. Rousseff’s impeachment and removal from office in 2016, and the subsequent election of Jair Bolsanaro in 2018, who espoused a tough stance against Cuba, labeling the socialist government a “troika of tyranny” (alongside Venezuela and Nicaragua) resulted in the Cuban government later recalling all of its doctors in protest, which had grown to over 10,000 by that time. Still facing gaping holes in healthcare access for large swaths of the population precipitated by the closure of Mais Médicos in May 2020, surging Covid cases led the Brazil government to license and rehire 157 Cuban doctors who had remained in the country.Footnote 34

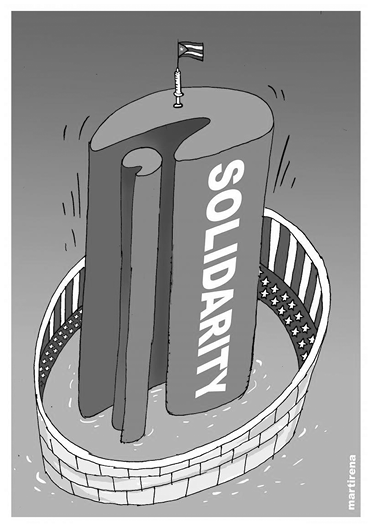

Cuba’s cooperative missions form a biopolitical project working to fill in the gaps of state-sponsored social welfare programs, where rights discourses, such as the constitutionality of health, break down at the level of quotidian access. Such an endeavor is never apolitical and the Cuban government, its solidarity missions, and individual Cubans must traverse these overlapping histories and controversies. In so doing, they must face conflictual world-making strategies engendered through enacting definitions of what constitutes health(care) vis-à-vis the state. Cuban solidarity missions, caught in this nexus, have thus also become the target of aggressive foreign policies. For over sixty years, and throughout thirteen US presidents, Cuba has navigated the contours of the ongoing obstacles of the US economic embargo. From this enforced position, and because of it, Cuban socialism, and its variant of solidarity humanitarianism, is a history of antagonism. The country has hit brick walls, thwarted, and persisted beyond and in the face of existing normative and regulatory logics (dominated mainly by US interests) operating in concert with the forces of liberal states and laissez-faire capitalist markets – markets designed by Bretton Woods agreements, the World Trade Organization, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. For example, Cuban political cartoonist Alfredo Martirena compellingly visualizes Cuba’s solidarity missions within a context of political contingency (see Figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3 “Cuba solidarity blocked, October 5, 2014”

Examining political contingency and Cuba’s solidarity humanitarianism must also confront what José Quiroga asserts: “that there are at least two histories” of the Cuban Revolution, divided into categories of the “official and the dissident.”Footnote 35 Quiroga’s insistence on the multivocality of Cuba’s historiography problematizes, as other scholars have noted, that no shared neutral vocabulary exists to discuss the Cuban Revolution of 1959.Footnote 36 The revolution is a utopic dream for some and a nightmare for others. For instance, as Misión Barrio Adentro expanded in Venezuela, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of State instituted the Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program (CMPP) under President George W. Bush’s administration. The CMPP, created in 2006, allowed Cuban medical personnel, and in some cases, their family, working in third-party countries to apply for “parole” in the United States. Cuban physicians were given a legal path to seek resident status in the United States. US senators argued that the rationale for the CMPP is to rescue Cuban doctors living in impoverished conditions without necessities, such as food and electricity, and a small salary. The Obama Administration suspended the CMPP program in January 2017. By then, the United States had approved parole for 7,117 Cuban medical professionals, mainly from missions in Venezuela. However, the suspension of the program prompted a concerned group of senators and representatives to urge the DHS to reinstate it, claiming that the Cuban government exploited medical workers in return for as much as $8 billion in payments a year, drawing heavily on the language of human trafficking and the “doctor-as-slave” discourse.Footnote 37

In 2020, an official for the U.S. Department of State asserted in a statement to the Washington Post, “Cuba’s deployment of medical missions overseas, while cloaked in altruism, is a scheme to generate income that exploits Cuban medical workers. Cuba’s medical missions program is not inherently humanitarian; the regime earns income by retaining up to 90 percent of the doctors’ salaries.”Footnote 38 Yet, eclipsed from this selective framing is why altruism is the universal benchmark for defining humanitarianism as a practice. For instance, why does the insertion of any form of economic value intrinsically change the nature of the relationship of care? Historically, Western humanitarianism, which includes much of mainstream global health, is tied, sometimes obliquely, to disaster and philanthropy capitalism, structural adjustment programs and conditional trade agreements, and blossoming industries of NGOs and for-profit voluntourism in health and development. These complex entanglements suggest that the marriage of humanitarianism to explicit or implicit (or both) economic and political agendas is not unique to Cuba.

Social Medicine, Otherwise

At the end of the twentieth century, global health became the dominant narrative and organizing logic for a “new regime of representation and intervention” into the health and well-being of targeted populations.Footnote 39 What is needed, then, is a critical analysis of the dominant discourses and practices of global health as a particular kind of problem space. The concept of “problem-space,” introduced by David Scott, examines an “ensemble of questions and answers around which a horizon of identifiable stakes (conceptual as well as political stakes) hangs.”Footnote 40 This approach provides critical conceptual resources to explore the discursive historical context that generates questions that may be vibrant and urgent for a period but sometimes lose traction and stop being relevant over time. Still, as Scott notes, other questions persist in relevance and importance. He argues that the task at hand is in recognizing at what moment a problem-space of questions about the past from the past is “no longer in sync with the world they were meant to describe and normatively criticize.”Footnote 41

As the ravages wrought by the Covid-19 epidemic lay bare, globally divergent histories of colonialism and racism, redlining, and institutionalized forms of structural violence and modern-day extractive capitalism negatively and disproportionately impact the health of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. Yet, these complex and often violent entanglements contributing to health and well-being are often excised out of view, bracketed as questions of a different order outside interventions targeting health in the problem space of global health. This demands questions: What constitutes health or well-being, or the notion of a healthy subject, why, and to whom? Within the dominant global health discourses, some answers to these questions are illegible “because [they defy] the terms under which the questions are phrased.”Footnote 42 What is needed is to question the stable, timeless, and transparent concepts that establish the political conditions for “unthinkability.” This interrogation requires confronting paradigm paralysis: the inability, epistemic blindness, or political refusal to see beyond the current models that structure the logic and practice of contemporary global health.

For example, in mid 2020, calls to decolonize global health, bolstered by ongoing social movements such as Black Lives Matter, Standing Rock, Idle No More, and the People’s Health Movement, challenged the pervasive logics of intervention defining global health. Consider the work of Hi’ilei Hobart and Tamara Kneese, who advocate for radical care as “a set of vital but underappreciated strategies for enduring precarious worlds.”Footnote 43 Such strategies, they argue, are attentive to the plurality of care and differential objectives and aims. Solidarity, not aid or charity, they note, drawing on the work of Dean Spade, offers a strategy for “working with communities and asking them what they need rather than making paternalistic assumptions. Instead of following neoliberal, colonialist development models around innovation and the mining of hope, mutual aid offers a space of collaboration.”Footnote 44

Chávez died in 2013 and Castro in 2016. In 2025, Misión Barrio Adentro continues to persist, even as the socioeconomic conditions in Venezuela deteriorate under US sanctions, dropping global oil prices, and political factionalism within the country. What, then, of the future of solidarity as care? With the dominant script of global health, there is a tendency to rapidly skim over programs like Barrio Adentro or Mais Medicos as transparent forms of political theater, as radical or socialist dystopic fantasies, and thus dismissible without much consideration. What if we examined Barrio Adentro with the same critical scrutiny and serious engagement as past and current global health ambitions, such as the Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations in 2016, defined as: “A blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all people and the world by 2030.” This latest UN program, following a similar trajectory of other multilateral, transnational global health programs sponsored by the WHO, among other leading institutional actors, will undoubtedly join the growing archive of past-tense promises, populating growing lists of elusive target goals (e.g., WHO’s “Health for All by 2000”). Despite repeated failures, such promissory campaigns generate a distinct genre of futurity, defined by speculative and political stakes of health equity. This genre, essential to the liberal imaginary, prescribes, reinforces, and calcifies a limited political vocabulary for defining the present and expanding future possibilities for constructing economies of care.

Like all the promissory targets of mainstream global health programs, social medicine projects such as Mais Medicos and Barrio Adentro have political stakes and they all stake political claims as an investment in futurity. Most global health discussions of Cuba’s humanitarian solidarity programs are relegated to Cuban or Latin American studies or bracketed as South–South collaboration models in development studies literature. As a result, different iterations of a “single story” – that is, Cuba’s solidarity humanitarian missions as a case study of global health from the South – continue to be the only narrative framing available.Footnote 45 My argument goes in a slightly different direction. Cuba’s solidarity programs envision radically different health(care) geographies through institutional practices, producing innovative arrangements of capital, labor, commodities/goods, and services. Such programs generate critical optics to redact and annotate the dominant script of global health.

Writing about futurity amidst debates focused on anti-relationality and the impossibility of a queer political collectivity, the late queer theorist José Muñoz argues, “We must strive in the face of the here and now’s totalizing rendering of reality, to think, and feel a then and there.”Footnote 46 Queerness, rather than anti-relational, he suggested, is a “performance because it is not simply a being but a doing for and toward the future.”Footnote 47 Queerness is not yet here but an ideality, Muñoz asserted. His insistence on queer futurity challenges the normative responses to the fear of hope and utopia as affective projects of disappointment and failure. The history of global health is an archive of broken promises as health inequities continue to rise, sediment, and become institutionalized. Interventions necessitate interventions that necessitate further interventions in perpetuity. The queering of care in global health interventions may offer another framework to theorize care as an ideality, not-yet-here, as anticipatory.

This chapter ends with a speculative thought experiment. What if capitalism is the disease and rampant economic inequality is the symptom? What if global health interventions took the form of sovereign debt alleviation, restitution of land, or reparations for slavery, among other macro-structural targets? Of course, to express such speculative utterances is to adopt the style of a manifesto, bearing uncanny cadence to the opening epigraph outlining Breton’s surrealist ambitions for thought, language, and human experience to escape the reductive forces of Enlightenment rationalism. Cuban heath(care) praxis offers a lens to think and theorize an Otherwise, unveiling dominant ideological networks of power but, equally and crucially, creating space to interrupt the so-called canon, explore other modalities of existence, and imagine different speculative futures. I argue that rather than a script of an illogical plot, it sets the stage to repeat Muñoz’s words, “to think and feel a then and there” of future praxis.