Individuals with mild cognitive impairment ((MCI) referring to the transitional state between normal ageing and dementia) and dementia (a progressive cognitive impairment syndrome mainly caused by Alzheimer’s disease) have to cope with many challenges. For instance, they often experience impairments in their functionality (e.g. difficulties with handling finances or preparing meals). Reference Liu-Seifert, Siemers, Sundell, Price, Han and Selzler1 Thus, they often demand extensive care and supervision. Reference Angeles, Berge, Gedde, Kjerstad, Vislapuu and Puaschitz2 Because of their cognitive impairment, admission to nursing home is sometimes inevitable.

Such factors can markedly shape their social relationships and social activities. For example, having more unidirectional relationships, such as contact with professional carers, could change the quality of relationships. In this case, one-sided interactions where people living with dementia are cared for by professional carers may feel unsatisfactory. Family relationships can also change as a result of care. Reference Happich, König and Hajek3 The increasing cognitive impairment could also be accompanied by a reduction in social activities (e.g. turning away from social engagement), eventually resulting in loneliness (perceived discrepancy between actual and desired social relationships, either in qualitative or quantitative terms Reference Perlman and Peplau4 ) and social isolation (lack of social activities Reference Hajek and König5 ).

Loneliness and isolation are risk factors for poor health outcomes in later life. Reference Hajek, Riedel-Heller and König6,Reference Luo, Hawkley, Waite and Cacioppo7 For example, they can not only increase the risk of mental disorders (e.g. depression or anxiety), but also the risk of cardiovascular diseases (e.g. coronary heart disease and stroke) and poor self-rated health. Reference Paul, Bu and Fancourt8,Reference Park, Majeed, Gill, Tamura, Ho and Mansur9 Previous research has also demonstrated a link between loneliness/isolation and poor sleep, as well as impaired cognitive functioning. Reference Hajek, Riedel-Heller and König10,Reference Hajek and König11

For instance, a previous meta-analysis of longitudinal studies showed that loneliness was positively associated with an increased risk of MCI (odds ratio 1.14, 95% CI 1.05–1.23). Reference Fan, Seah, Lu, Wang and Zhou12 Another meta-analysis showed that loneliness was also associated with an increased risk of dementia (relative risk 1.23, 95% CI 1.16–1.31). Reference Qiao, Wang, Tang, Zhou, Min and Yin13 Comparably, low social isolation levels were associated with better cognitive functioning in late life (r = 0.05, 95% CI 0.04–0.06). Reference Evans, Martyr, Collins, Brayne and Clare14 In contrast to these frequently investigated associations between loneliness or social isolation and MCI or dementia, the prevalence of loneliness and social isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia has been much less researched.

However, there are some studies that examine the prevalence of loneliness/isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia. For example, Eshkoor et al Reference Eshkoor, Hamid, Nudin and Mun15 found that 47.9% of community-dwelling individuals with dementia can be classified as socially isolated in Peninsular Malaysia. Other research Reference Sung, Chan and Lim-Soh16 has showed that 33.3% of community-dwelling individuals with MCI can be classified as lonely in Singapore. However, no systematic review/meta-analysis synthesising existing evidence has been undertaken. Therefore, our aim was to conduct the first systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the prevalence and factors associated with loneliness and social isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia.

It is projected that the global number of individuals with dementia may increase from 57.5 million in 2019 (95% CI 50.4–65.1) to 152.8 million (95% CI 130.8–175.9) in 2050, Reference Nichols, Steinmetz, Vollset, Fukutaki, Chalek and Abd-Allah17 a fact that underscores the relevance of our topic. Moreover, previous research has also suggested a steep increase in the number of individuals with MCI by 2060, Reference Rajan, Weuve, Barnes, McAninch, Wilson and Evans18 further highlighting the relevance. This present work may determine potential antecedents and consequences of loneliness/social isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia. Furthermore, this work might shed light on present gaps in knowledge. This could further inspire future studies. Compared to single studies, meta-analyses can also yield a more accurate overview. Moreover, it is important because social isolation is a modifiable risk factor for dementia. Reference Livingston, Huntley, Sommerlad, Ames, Ballard and Banerjee19 Consequently, prevalence estimates are crucial for developing dementia prevention strategies. Furthermore, similar to older adults in general, one can assume that loneliness and social isolation predict subsequent poor physical and mental health outcomes among individuals with MCI or dementia. Thus, understanding the frequency of loneliness and social isolation is essential.

In terms of clinical implications, discussing and asking about loneliness and social isolation can improve patient–provider connections and health outcomes. Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20 For example, older adults are frequently worried about developing dementia. Reference Meyer, Buczak-Stec, König and Hajek21 Thus, they might be highly motivated to tackle determinants such as isolation and loneliness. Reference Harrington, Vasan, Kang, Sliwinski and Lim22,Reference Huang, Roth, Cidav, Chung, Amjad and Thorpe23

Method

This current study satisfied the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow24 Our work was also registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42024550504). Subsequent amendments were not made. Of note, we initially intended to perform a meta-regression. However, because of the number of studies included in meta-analysis, we refrained from doing a meta-regression. This procedure is in accordance with existing recommendations. Reference Deeks, Higgins and Altman25

In June 2024, an electronic search was done across five databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Web of Science and Scopus. The search strategy for all electronic databases is shown in Supplementary File 1. Our search strategy (and the selection of databases) was also guided by a librarian’s advice, with whom we had intensive dialogue.

The relevance assessment was performed in two stages by two reviewers (A.H. and H.-H.K.): first, they screened the titles and abstracts independently, and then they examined the full texts independently, i.e. both steps were performed dually and independently. Additionally, a manual search was performed by reviewing the references of the included studies and checking for studies that cited those included. When there were differing opinions on study inclusion, discussions were held to reach a consensus.

The inclusion criteria of this work were as follows: (a) cross-sectional and longitudinal observational studies focusing on the prevalence of loneliness or social isolation among individuals with MCI and/or individuals with dementia, (b) use of appropriate tools for assessing key variables and (c) studies available in English or German and published in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Grey literature was not examined. There were no restrictions regarding place and time of studies. An appropriate assessment for loneliness/isolation and MCI/dementia closely follows the criteria described in the Consensus-Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) guidelines. Reference Prinsen, Mokkink, Bouter, Alonso, Patrick and De Vet26

A pre-test examining 100 titles/abstracts was first performed before determining the final inclusion criteria. However, our inclusion criteria were not altered. One author (A.H.) performed data extraction and a second author (H.-H.K.) checked the data extraction carefully. Data extraction (first extracted on 6 June 2024) covered the design of the study, measurement of loneliness/isolation, tool used to determine MCI/dementia, characteristics of the sample, analytical approach and main findings. When data were incomplete or unclear, the authors of the respective studies were contacted via email. We used Cohen’s kappa to evaluate the interrater agreement between the two authors (A.H., H.-H.K.). Cohen’s kappa was 0.83 for full-text selection.

The Joanna Briggs Institute standardised critical appraisal instrument, designed for prevalence studies, was used for assessing the quality of the studies. Reference Moola, Munn, Tufanaru, Aromataris, Sears, Sfetc, Aromataris and Munn27 The final sum score varies from 0 to 9, whereby higher values reflect a better study quality and a lower risk of bias. The evaluation of the study quality was performed dually (A.H., H.-H.K.) and independently. Of note, we did not apply a specific cut-off for excluding studies from meta-analysis.

A random-effects model for meta-analysis was used because heterogeneity across studies was assumed. Following current recommendations, the I²-statistic was used to evaluate heterogeneity among studies (with I²-values 25–50% categorised as low, 50–75% as moderate and ≥75% as high heterogeneity). Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman28

In our main analysis, we only distinguished between the presence and absence of loneliness. The absence of loneliness refers to ‘no, seldom’ or ‘no, never’ when replying to a single-item measure of loneliness. Moreover, it simply refers to ‘no’ when using a single item of loneliness distinguishing between the absence and presence of loneliness. Furthermore, established cut-offs were used that were applied in the studies included in this meta-analysis (see Table 1 for further details).

Table 1 Study overview and key findings

LSNS-6, Lubben Social Network Scale, 6-item version; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; DemTect, Demenzdetektionstest; UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles.

It was initially intended to compute a funnel plot and perform the Egger test (with P < 0.05 indicating the presence of publication bias) to determine a possible publication bias. Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder29 However, because of the small number of studies, we refrained from performing it. We used Stata version 18.0 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) for statistical analysis, i.e. meta-analysis. We also used the metaprop tool. Reference Nyaga, Arbyn and Aerts30

Results

Study overview

A flowchart illustrating the search process is shown in Supplementary File 2. Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow24 Overall, 7427 records were identified. First, duplicates were removed, resulting in 4217 hits, which were screened. The titles/abstracts were screened. The main reason for excluding studies was the lack of prevalence data on loneliness or social isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia. After this screening procedure, 48 full texts were examined in the next step. Most of these studies did not meet the inclusion criteria, frequently because they did not provide prevalence data for the groups of interest. Some studies were also excluded from the full-text screening because they described loneliness among individuals who only later developed MCI/dementia. Reference Rafnsson, Orrell, d’Orsi, Hogervorst and Steptoe31,Reference Sutin, Stephan, Luchetti and Terracciano32 In this systematic review and meta-analysis, ten studies were included in total (three of these studies were identified in the manual hand search). Reference Eshkoor, Hamid, Nudin and Mun15,Reference Sung, Chan and Lim-Soh16,Reference Victor, Rippon, Nelis, Martyr, Litherland and Pickett33–Reference Fang, Liu, Yang, Xu and Chen40

Main characteristics and key findings of the studies are provided in Table 1. Adjusted findings are presented in Table 1. The studies were exclusively from Europe and Asia: two studies from Sweden, two studies from England (thereof, one study included data from England/Scotland/Wales), two studies from Malaysia and one study each from Germany, China, Pakistan and Singapore. Six studies had a cross-sectional design, and four studies had a longitudinal design. Five studies included both community-dwelling and institutionalised individuals, whereas three other studies exclusively included community-dwelling individuals, and two studies exclusively included individuals residing in institutionalised settings such as nursing homes. The studies were partly based on well-known samples such as the Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life (IDEAL) cohort or the Umeå 85+/Gerontological Regional Database study, whereas other studies conducted surveys/examinations on their own. The established samples in particular had large cohorts of about 1000–2000 individuals with MCI or dementia, whereas the remaining studies included about 100–400 individuals with MCI or dementia. All studies included both women and men, with the proportion of women mainly ranging from approximately 40 to 70%. The average age of study participants often ranged from about 70 to 90 years across the studies. Single-item tools were most frequently used to measure loneliness, followed by University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) tools Reference Hughes, Waite, Hawkley and Cacioppo41 and the De Jong Gierveld (DJG) tool. Reference De Jong-Gierveld and Kamphuls42,Reference Gierveld and Tilburg43 Two studies used the Lubben Social Network Scale, 6-item version (LSNS-6) tool Reference Lubben, Blozik, Gillmann, Iliffe, von Renteln Kruse and Beck44 and one study used the friendship scale to quantify social isolation. Established screening tools (e.g. Mini-Mental State Examination Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh45 ) were mainly used to measure MCI or dementia.

The publication dates ranged from 2000 to 2024, with seven studies published in 2020 or later, and the remaining three studies published in 2000, 2014 and 2015, respectively. The date of data collection is not clear for all studies, but based on the publication date, it can be assumed that all studies used data from before the COVID-19 pandemic. Additional details are shown in Table 1.

In total, four studies reported the prevalence of loneliness among individuals with MCI and four studies reported the prevalence of loneliness among individuals with dementia (one study reported both the prevalence of loneliness among individuals with MCI and individuals with dementia Reference Hajek, Kretzler, Riedel-Heller and König39 ). In addition, one study reported the prevalence of social isolation among individuals with MCI, one study reported the prevalence of social isolation among individuals with dementia and one further study reported the prevalence of social isolation among individuals with cognitive impairment (without further distinguishing between MCI and dementia).

Meta-analysis

The estimated prevalence of loneliness was 38.6% (95% CI 3.7–73.5%, I² = 99.6, P < 0.001) among individuals with MCI (see Fig. 1). When the study conducted by Zafar et al Reference Zafar, Malik, Atta, Makhdoom, Ullah and Manzar34 (which had a very high prevalence of loneliness) was excluded from meta-analysis, the estimated prevalence of loneliness decreased to 22.7% (95% CI 9.9–35.4%, I² = 95.0, P < 0.001) among individuals with MCI.

Fig. 1 Meta-analysis of loneliness among individuals with mild cognitive impairment.

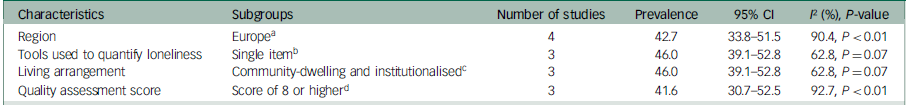

In addition, the estimated prevalence of loneliness was 42.7% (95% CI 33.8–51.5%, I² = 90.4, P < 0.001) among individuals with dementia (see Fig. 2). Of note, stratified by gender, the estimated prevalence of loneliness was 44.2% (95% CI 28.9–59.5, I² = 94.0, P < 0.01) among women with dementia and 32.2% (95% CI 29.4–35.1%, I² = 0.0, P = 0.39) among men with dementia. A meta-analysis for loneliness stratified by gender for individuals with MCI was not possible because of the lack of studies. We also conducted a meta-analysis with prevalence of loneliness for other subgroups among individuals with MCI (Table 2) and individuals with dementia (Table 3).

Fig. 2 Meta-analysis of loneliness among individuals with dementia.

Table 2 Subgroup analysis of the pooled prevalence of loneliness (among individuals with mild cognitive impairment)

a. Because of the lack of studies, a meta-analysis could not be conducted with studies only including single-item tools.

b. Because of the lack of studies, a meta-analysis could not be conducted with studies only including community-dwelling individuals or institutionalised individuals.

Table 3 Subgroup analysis of the pooled prevalence of loneliness (among individuals with dementia)

a. Because of the lack of studies, a meta-analysis could not be conducted with studies only including individuals from Asia.

b. Because of the lack of studies, a meta-analysis could not be conducted with studies only including multi-item tools.

c. Because of the lack of studies, a meta-analysis could not be conducted with studies only including community-dwelling individuals or institutionalised individuals.

d. Because of the lack of studies, a meta-analysis could not be conducted with studies having a quality score of 7 or lower.

With respect to severity of loneliness experienced by the sample (i.e. moderate and severe loneliness), the estimated prevalence of moderate and severe loneliness was 38.1% (95% CI 34.0–42.3%, I² = 0.0) and 9.1% (95% CI 6.2–12.1%, I² = 0.0), respectively, among individuals with MCI. The estimated prevalence of moderate and severe loneliness was 29.8% (95% CI 27.5–32.0%, I² = 0.0) and 5.5% (95% CI 4.3–6.6%, I² = 0.0), respectively, among individuals with dementia.

One study examined social isolation among individuals with dementia, a second study examined social isolation among individuals with MCI and a third study investigating social isolation did not differentiate between MCI and dementia. We decided to consider all three studies in the meta-analysis, to provide a first impression of the prevalence of social isolation among individuals with cognitive impairment; the estimated prevalence of social isolation was 64.3% (95% CI 39.1–89.6%, I² = 99.6, P < 0.001) among individuals with cognitive impairment (see Fig. 3). The prevalence of social isolation reduced to 49.0% (95% CI 47.3–50.8%) among individuals with cognitive impairment when the study by Nikmat et al Reference Nikmat, Hashim, Omar and Razali38 (which had an extraordinarily high prevalence of social isolation) was removed from the meta-analysis.

Fig. 3 Meta-analysis of social isolation among individuals with cognitive impairment.

Loneliness: predictors and outcomes

Two studies investigated the predictors of loneliness among individuals with dementia. Both studies showed that living alone and depressive symptoms were associated with a higher loneliness risk in some European countries. Reference Victor, Rippon, Nelis, Martyr, Litherland and Pickett33,Reference Lampinen, Conradsson, Nyqvist, Olofsson, Gustafson and Nilsson36

Two studies examined the outcomes of loneliness among individuals with MCI. One study showed that loneliness can contribute to the development of dementia in such group. Reference Willmott, Martin West, Yung, Giri Shankar, Perera and Tsamakis37 Another study showed that loneliness of individuals with MCI (care recipients) was not associated with loneliness of caregivers, based on dyadic data. Reference Sung, Chan and Lim-Soh16

A further study showed that loneliness partially mediates the link between depression and quality of life among individuals with MCI. Reference Zafar, Malik, Atta, Makhdoom, Ullah and Manzar34

Social isolation: predictors and outcomes

Two studies examined the consequences of social isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia. One study showed that social isolation was significantly associated with higher odds of sleep disturbances among individuals with dementia. Reference Eshkoor, Hamid, Nudin and Mun15 A second study showed that social isolation was significantly associated with a greater risk of peptic ulcer disease recurrence among individuals with MCI. Reference Fang, Liu, Yang, Xu and Chen40 None of the studies examined the determinants of social isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia.

Quality assessment/risk-of-bias assessment

The assessment of the study quality/risk of bias is shown in Supplementary File 3. The scores varied from 5 to 9 (mean 7.2, s.d. = 0.8), corresponding to a quite good level in total, with a quite low bias risk. The unclear or insufficient presentation or management of low response rates was the most common limitation observed across included studies.

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis showed that loneliness and social isolation are highly prevalent in people with dementia and MCI. This finding has important implications for prevention strategies aimed at reducing the disease burden of these conditions.

A previous meta-analysis revealed a pooled prevalence of loneliness of 28.6% (95% CI 22.9–35.0%) among individuals aged 65 years and over during the COVID-19 pandemic, covering 15 countries across Asia, Europe, North America and South America. Reference Su, Rao, Li, Caron, D’Arcy and Meng46 This work also revealed a pooled prevalence of social isolation of 31.2% (95% CI 20.2–44.9%). Not surprisingly, we found markedly higher prevalence rates in our current work. In our view, this can be explained primarily by the differences in the cognitive impairments of the populations studied.

Comparing the prevalence of loneliness among individuals with MCI and dementia, the rates seem to differ only moderately. However, when the study Reference Zafar, Malik, Atta, Makhdoom, Ullah and Manzar34 with a very high prevalence of loneliness in individuals with MCI was omitted from the meta-analysis, there were much more pronounced differences in loneliness among individuals with MCI compared with individuals with dementia. These greater differences would align with former meta-analyses identifying a weaker association between loneliness and risk of MCI Reference Fan, Seah, Lu, Wang and Zhou12 compared with the association between loneliness and dementia. Reference Qiao, Wang, Tang, Zhou, Min and Yin13 Of note, our meta-analyses for corresponding subgroups (e.g. stratified by continent) must be interpreted with great caution because of the small number of studies. We would therefore like to refrain from discussing these in depth in this current work.

Two included studies determined that living alone and more depressive symptoms were associated with a higher loneliness risk among individuals with dementia. Reference Victor, Rippon, Nelis, Martyr, Litherland and Pickett33,Reference Lampinen, Conradsson, Nyqvist, Olofsson, Gustafson and Nilsson36 Very similar results have been identified by a former systematic review/meta-analysis investigating the prevalence and correlates of loneliness/social isolation among the most eldery. Reference Hajek, Volkmar and König47 Because of the paucity of literature on the predictors and outcomes of loneliness/isolation in people with MCI or dementia, no further reliable conclusions can be drawn. Rather, this lack of studies stresses the need for further research.

The mean quality of the included studies was quite high. However, several studies did not clarify the response rate or clarify how they managed low response rates. Given the fact that older individuals with cognitive impairment were examined, it is reasonable that the (not reported) response rates in the studies might actually be rather low. It is also plausible that individuals with more severe cognitive impairments had a lower participation rate, suggesting a potential sample selection bias. In this respect, the generalisability of the samples may not always be fully given. This should be acknowledged as a potential limitation of the studies included in this work.

Some knowledge gaps were identified. Overall, there are only a few studies on this topic. For instance, there is a clear need for future studies examining social isolation among individuals with MCI and dementia. Although loneliness can be measured with single-item tools, Reference Mund, Maes, Drewke, Gutzeit, Jaki and Qualter48 upcoming research with multi-item tools, such as the DJG tool Reference Gierveld and Tilburg43 or the ALONE scale (a tool specifically developed for older adults) by Deol et al, Reference Deol, Yamashita, Elliott, Malmstorm and Morley49 would be desirable to better capture the complexity of loneliness. Moreover, an additional external assessment of loneliness may also be useful because it may be the case that self-ratings differ from external ratings because of, among other things, language barriers of individuals with MCI or dementia. Future research in this area is recommended. Furthermore, the types of loneliness (emotional versus social loneliness) and subtypes of dementia (e.g. vascular dementia or Alzheimer’s disease) could be examined in future research. Furthermore, long-running studies (with large samples) would be desirable to better identify the factors leading to loneliness or social isolation – in particular, chronic states of loneliness and social isolation – and their consequences among individuals with MCI or dementia (e.g. based on the Social Relationship Expectations Framework). Reference Akhter-Khan, Prina, Wong, Mayston and Li50 Moreover, a greater geographical diversity when examining loneliness/isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia is clearly required. Thus, we encourage research from North America, South America, Oceania and Africa. Individuals with MCI or dementia had a particularly difficult time during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. because of contact restrictions). Reference Levere, Rowan and Wysocki51 We would therefore also recommend future research during and after the pandemic. Although it should be acknowledged that some studies have already included individuals living in institutionalised settings, we would like to stress the need for further research in this setting (which is often associated with more severe cognitive impairment Reference Hajek, Brettschneider, Ernst, Posselt, Mamone and Wiese52 ).

It is important to acknowledge the strengths and limitations of our present systematic review and meta-analysis. This study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis specifically investigating the prevalence of loneliness and social isolation among individuals with MCI or dementia. Important procedures were performed independently by two reviewers. Our work adheres to existing guidelines and was preregistered (PROSPERO). We also conducted a meta-analysis. A notable limitation is our restriction to peer-reviewed articles, which may have led to the exclusion of relevant studies. However, this approach was chosen to maintain a high standard of study quality. Five comprehensive databases were used, although this choice might have still resulted in the exclusion of appropriate studies. However, we assume that we were able to find most of the key studies by using these large databases in combination with the additional hand search. Because of the number of studies, we did not perform a meta-regression, in accordance with existing recommendations. Reference Deeks, Higgins and Altman25 However, if sufficient studies were available in the future, we would encourage future work to perform meta-regressions to uncover possible differences, e.g. in ethnicity, living situation, coping resources or personality.

The high prevalence of loneliness and social isolation among individuals with dementia or MCI indicates a need for public health strategies aimed at alleviating the disease burden caused by loneliness. Implementing such strategies could potentially reduce the incidence of dementia and MCI, and may also enhance outcomes for those already diagnosed with dementia or MCI. Of note, Borjali and Taheri Reference Borjali and Taheri53 recently proposed a multifaceted approach including public awareness campaigns, community-based interventions and training for healthcare providers. Moreover, based on an umbrella review of former systematic reviews and meta-analyses, Veronese et al concluded that meditation/mindfulness, social cognition training and social support interventions can reduce loneliness. Reference Veronese, Galvano, D’Antiga, Vecchiato, Furegon and Allocco54

Perissinotto et al also described individual clinical ways to tackle loneliness. These ways may include improving social skills, enhancing social support, finding opportunities for social interactions and tackling maladaptive social cognition Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20 (see also Masi et al Reference Masi, Chen, Hawkley and Cacioppo55 ). For example, improving social skills may involve psychotherapy for people who have problems with social interactions or relationships. Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20 To improve social support, health professionals need to identify what is missing in a person’s life and use available community resources. Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20 Opportunities for social interactions can be improved by a variety of factors. One simple way may be hearing aids. Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20 Hearing impairments are also quite common among older adults with MCI or dementia. Reference Nieman, Morales, Huang, Reed, Yasar and Oh56 Other efforts could focus on strengthening transportation when being functionally impaired, Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20 which often co-occurs with MCI and dementia. Reference Cipriani, Danti, Picchi, Nuti and Fiorino57 Additionally, cognitive–behavioural therapy may support individuals in reframing harmful beliefs that affect their social interactions, which may require the involvement of behavioural health specialists to support emotional coping with critical life events that may lead to loneliness. Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20 Other research has also suggested including screening tools for isolation and loneliness in electronic health records. Reference Perissinotto, Holt-Lunstad, Periyakoil and Covinsky20

In conclusion, social isolation, and particularly loneliness, are significant challenges for individuals with MCI or dementia. Knowledge summarised by this study can help to improve the quality of life of individuals with MCI or dementia. Future research in regions beyond Asia and Europe are clearly required. Additionally, challenges such as chronic loneliness and chronic social isolation should be examined among individuals with MCI or dementia.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2024.865

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created.

Author contributions

The study concept was developed by A.H. and H.-H.K. The manuscript was drafted by A.H. and critically revised by H.-H.K. The search strategy was developed by A.H. and H.-H.K. Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment were performed by A.H. and H.-H.K. A.H. and H.-H.K. contributed to the interpretation of the extracted data and writing of the manuscript. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.