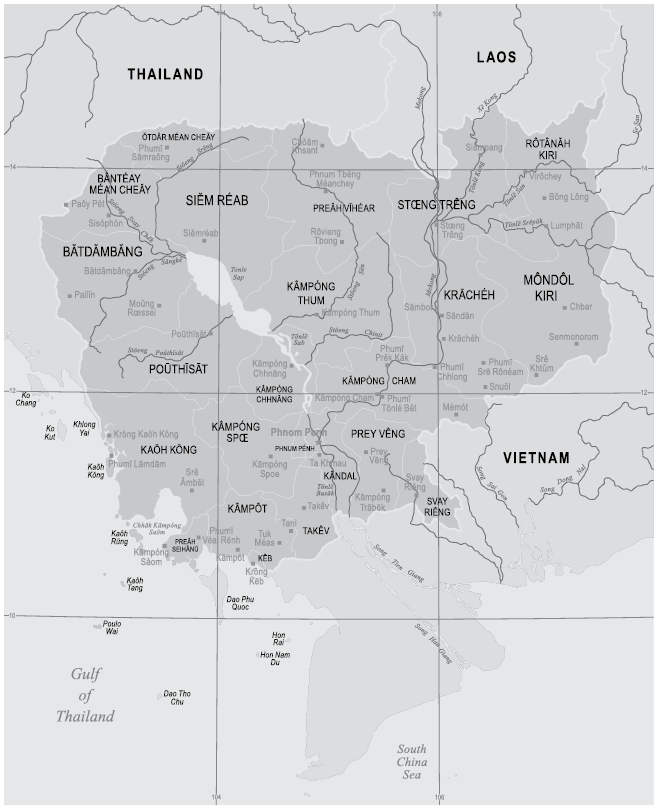

Cambodia sits in the middle of the Southeast Asian peninsula, with Thailand along its western and northern border, Laos to the northeast, and Vietnam along its eastern border all the way from Laos to the Gulf of Thailand. Cambodia’s size makes it a little larger than Washington State. In 1960 its population came to almost 5.5 million; by 1970 it had grown to just over 7 million.

Because of its geographical location, and considering its neighbors and various historical forces, over the centuries prior to French colonization in the mid-nineteenth century Cambodia faced pressure from the Thais when the Thai kingdom was strong and well run. Conversely, Cambodia also faced pressure from the east when the Vietnamese were aggressive and expansionist. Cambodia, much like Poland in Europe, has struggled over the centuries to maintain its independence and territorial integrity in the face of strong neighbors on both sides.Footnote 1

It is important, however, not to equate Cambodian–Thai relations with Cambodian–Vietnamese relations. There were major differences. Thai–Khmer relations were both influenced by Indian history and culture, whereas Khmer–Vietnamese relations were filled with greater tension and animosity in large part because the Vietnamese were influenced by China, and not India, and looked at Khmer people as barbarians. By one formulation, Cambodians have been “possessed by fear that not only their country but also the very existence of the Khmer people are in mortal danger, and they are convinced that the Vietnamese are their hereditary, implacable enemies, who hypocritically hide their true, rapacious intentions with words of false friendship.”Footnote 2

Cambodia fell victim to colonialization in the nineteenth century when France made the territory a protectorate within its broader mission civilisatrice efforts in Southeast Asia. Indochina, which encompassed Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, was the larger prize, but Vietnam was the primary focus, and because of that, Cambodia benefited in some ways. Cambodia, for example, never felt the heavy hand of the French colonial administration and was never asked to provide the same amounts of raw materials. In short, France never exerted the same level of intrusion into Cambodian affairs. On the other hand, this relative neglect came with a price: Cambodian society was never developed to the same degree as was Vietnamese, and that meant fewer schools, less infrastructure, and a lower commitment to building Cambodia’s administrative services.

Map 11.1 Cambodia.

The French did, however, involve themselves in the selection of Cambodia’s head of state. At the time of their arrival, the French encountered King Norodom. When Norodom died in 1904, the French moved the crown to a competing royal family, the Sisowaths, who were seen to be more agreeable to French rule. The French then moved the crown back to the Norodoms in 1941 in the form of Prince Norodom Sihanouk, then 18 years of age, because of his pliability. Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak was especially displeased, as he had expected to inherit the throne, and not his cousin.Footnote 3

Years of Escalation: 1953 to 1968

The young Sihanouk served as prince during World War II. As had been the case for much of the period of French colonial rule, Cambodia was not as affected by events during the war as was Vietnam. “Vichy rule was in some ways more flexible, in others more repressive and certainly more ideological” because of the need to appease the Japanese after France’s capitulation.Footnote 4 Cambodia did not suffer excessively from the Japanese occupation, and there was no great famine as the war ended. The French had a much lighter footprint in Cambodia after the war, as their energies were focused on reestablishing control in Vietnam. Sihanouk cooperated with the French, but when a rebel movement appeared to develop, the French negotiated a temporary agreement in January 1946 allowing Cambodia to hold elections in September. Sihanouk was able to proclaim the first Cambodian constitution in 1947, and by the end of 1948 Cambodia became an independent state within the French Union.

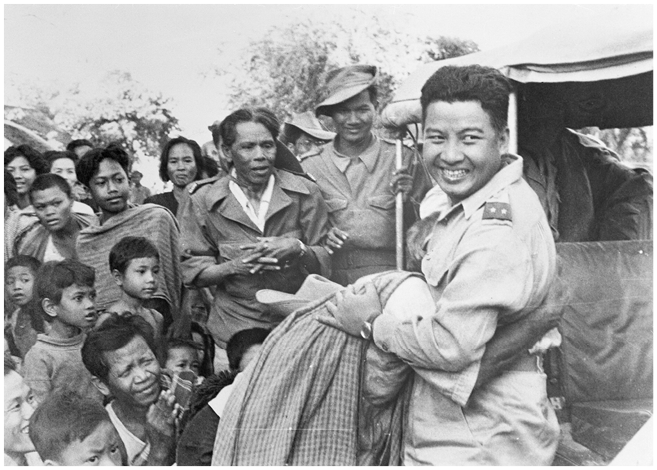

Sihanouk gave up his royal title in 1953 to become more involved in national politics and assumed the function of prime minister. By then, the United States was involved as it sought to bolster French efforts against the Việt Minh led by Hồ Chí Minh. American aid to France between 1950 and 1954 totaled $2 billion, all of it designated to assist French efforts in Vietnam. By contrast, Cambodia received $7.8 million. It was not much, but it was a beginning. After his father died in 1960, Sihanouk resumed his position as head of state. Between 1941 and 1970, Sihanouk ruled over Cambodia as “King, Chief of State, Prince, Prime Minister, head of the main political movement, jazz-band leader, magazine editor, film director and gambling concessionaire.”Footnote 5 The prince had an array of interests, it turned out, many of which did not actually involve governing Cambodia. Still, he was hugely popular among peasants. He was also incredibly vain and could be both petty and brutal in the way he treated those he deemed insufficiently loyal.

Although his first dozen years as king could be overlooked as the product of France’s seemingly complicated and neglectful designs, his rule, under various titles, from 1953 to 1970 was a testament to his diplomatic savviness in balancing Cambodia’s interests relative to a fading France, a China that grew increasingly central to the Cold War in Asia, and the United States, the most powerful of them all. He also demonstrated enormous internal political skill, and his popularity with Cambodian peasants, representing close to 85 percent of the population, allowed him to retain his standing as head of state despite a certain amount of turmoil and unhappiness amongst the small coterie of educated Cambodians.

In 1949–50, under President Harry Truman, the United States began committing itself to Southeast Asia. The initial aid took the form of military assistance to France. In January 1953, Truman was succeeded by Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower continued the assistance to France but balked in 1954 at providing American troops to rescue the besieged French garrison at Điện Biên Phủ. Despite the French defeat, the Eisenhower administration refused to abandon Indochina. Instead, the United States supported Ngô Đình Diệm to serve as eventual head of a new Vietnamese government south of the 17th parallel.

Figure 11.1 Cambodia’s King Norodom Sihanouk embraces an old woman in Battambang province (December 1953).

Diplomatically speaking, Sihanouk kept Cambodia out of the situation in Vietnam, much to the annoyance of the Eisenhower administration and especially Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. Dulles abhorred neutrality almost as much as he despised communism, and he told Sihanouk that he could not be neutral. “You cannot be a Switzerland in Asia,” Dulles told him, “you have to choose between the free world and the Communist camp.” For his part, Sihanouk thought Dulles was unpleasant and arrogant, and he denounced the 1954 Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).Footnote 6 Sihanouk did, however, allow for US military assistance to begin under the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) in 1955, which continued until 1963. Shortly after the assassination of South Vietnamese leader Ngô Đình Diệm and his brother-in-law, Ngô Đình Nhu, on November 2, 1963, Sihanouk ended all US military and economic aid, and he forced the Americans to close their embassy, though he did not formally break relations. In addition to the shock of Diệm’s assassination, Sihanouk worried that some of his more conservative officers were becoming too chummy with, and too dependent on, the United States. Such dependency had not boded well for Diệm.

Sihanouk also recognized the growing power of North Vietnam, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN), and wished to make a typical Cambodian accommodation to that reality. Sihanouk’s position became more precarious in the 1960s when first the Kennedy administration, and then the Johnson administration, escalated the war in Vietnam by increasing the number of US advisors and then troops in South Vietnam and initiating sustained bombings of the DRVN in Operation Rolling Thunder. Sihanouk reached such a point of frustration as the war escalated that he broke off formal diplomatic relations with the United States in May 1965. His decision did not change American policy one bit, and with the diplomatic cutoff, combined with the end of American aid, circumstances changed for those Cambodians, almost entirely located in the capital, Phnom Penh, who had become dependent on US spending. But Sihanouk was committed to preserving Cambodia’s neutrality, even at the cost of alienating Washington.

The United States and Cambodia were not entirely cut off from each other. Australia agreed to represent US interests in Phnom Penh as France represented Cambodia in Washington. The two sides thus continued to communicate when circumstances necessitated. When former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy wished to visit Cambodia in 1967, Sihanouk readily agreed and proved a gracious host. Sihanouk’s overriding concern during this period was to get as many countries as possible, including and especially the United States, to respect Cambodia’s neutrality and its current territorial boundaries. During the presidency of Lyndon Johnson, both sides made gestures toward improving relations. Johnson tasked a National Security Council (NSC) official with investigating ways to improve relations, despite opposition from the Pentagon. Sihanouk, for his part, spoke more favorably about the United States (or least less negatively) and even went so far as to support an American proposal regarding international negotiations, a position neither Beijing nor Hanoi favored. A border aerial assault by US forces that killed several Cambodians – and was witnessed by international observers, as well as members of the American media – put all progress on hold.

As the war escalated, American military leaders uniformly expressed negative views of Sihanouk. They disliked his insistence on Cambodian neutrality, since they wanted to use military force against North Vietnamese forces in Cambodia.Footnote 7 Sihanouk responded by quipping, “Americans attract Communists like sugar attracts ants.”Footnote 8 He had no intention of acquiescing. Still, Sihanouk worried about becoming too close to the Chinese communists and sought ways to keep open relations, or at least the possibility of discussions, with the Americans. Whatever steps both the Americans and Cambodians took toward healing the rupture, the war pushed them asunder. American military leaders continued aggressive actions into Cambodia, and Sihanouk continued to object. And yet, the escalation of the war, and the mounting North Vietnamese and National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) encroachment into Cambodia, put Sihanouk into an increasingly precarious position. How could he govern over territory occupied by communist-led Vietnamese forces or wantonly attacked by the Americans?

In July 1968, after Johnson had endured the Tet Offensive and announced his decision not to run for reelection in March, an American landing craft vessel, LCU 1577, traveled up the Mekong River. Thinking they were still in South Vietnam, the crew made a wrong turn into Cambodia, and the vessel and its crew of eleven were captured by Cambodian government forces. Johnson worried this could become a repeat of the US vessel Pueblo that had been taken hostage in January 1968 by the North Koreans. The administration made immediate overtures to have the crew returned. For various reasons, it took six months, but the crew was released in December, in time for everyone to return to the United States before Christmas. It all happened without Sihanouk insisting on American concessions. By the end of Johnson’s time in office, Sihanouk sought better relations because he worried about the growing power of political leftists in Cambodia, especially those ideologically aligned with Beijing and Hanoi. That led him to conclude that renewed relations with the United States would be to his strategic advantage. Standing in the way were continued US-led cross-border military incursions into Cambodia, so-called Daniel Boone raids, part of a reconnaissance effort that resulted in scores of Cambodians losing their lives in 1967. Before leaving office, Johnson officials approved direct compensation to Cambodians whose family members had been killed or injured as a result of American actions.

Henry Kamm, a New York Times correspondent who spent considerable time in Cambodia interviewing the principal actors, noted of Norodom Sihanouk that, whatever his shortcomings and idiosyncrasies, he was driven by a remarkably consistent view, one that derived “largely of his leading a desperately weak country tossed about by upheavals caused by more powerful neighbors and by great outside forces pursuing their own interests.”Footnote 9 Historian Kenton Clymer expressed the same sentiment a bit differently, observing that Sihanouk “had to maneuver carefully in a web of conflicting pressures.”Footnote 10

Despite bilateral efforts, relations did not improve enough, and they were not normalized before Johnson left office. Issues surrounding a border declaration (something the Thais and South Vietnamese opposed because of the consequences for their own borders) and continued loss of Cambodian life and destruction of Cambodian property in American attacks across the border prevented a reconciliation. After some time, however, the Cambodian government finally announced on June 11, 1969 that it was prepared to resume diplomatic relations. Lloyd “Mike” Rives reopened the US Embassy in Phnom Penh on August 15 as chargé d’affaires.

The Bombing Begins: 1969

While efforts were moving forward on the diplomatic front, American military leaders were busy with their own plans for how to integrate Cambodia into the war effort. US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) Commander General Creighton Abrams had wanted to bomb suspected Vietnamese communist sanctuaries in Cambodia since taking over from William Westmoreland in 1968. He argued that such action was necessary to destroy or degrade the North Vietnamese and People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF, the armed wing of the NLF) troops attacking American units and then crossing the border and hiding in sanctuaries just inside Cambodia. The Johnson administration had limited American actions to “hot pursuit,” with notable exceptions and plausibly deniable errors, but in January 1969 Richard Nixon became president, and he viewed things differently.

A conniving politician and at the same time a deeply insecure and suspicious individual, Nixon had campaigned on the promise of having a plan to end the war. Now that he was president, Nixon worried about real and imagined political enemies, as well as appearing weak, about secrecy, about getting proper credit for his actions, and much more. And when the DRVN launched an offensive shortly after he took office, Nixon took it personally and viewed North Vietnamese actions as testing his leadership, if not his manhood. So, when General Abrams requested, yet again, to bomb Cambodia, Nixon agreed. The initial request came in February, but it took a month for permission to work its way through the system and be granted. It was not until March 13, 1969 that the first strike of forty-two B-52 bombers was sent with an objective of disrupting and degrading Hanoi’s central office in South Vietnam, given the acronym COSVN (Central Office [Directorate] of South Vietnam). The elusive central office was not destroyed in the attack. American military advisors should have anticipated as much, for in the previous year, in the immediate aftermath of one of the Daniel Boone raids, a team visited the bombing site shortly afterwards to assess the damage and was promptly met with a hail of gunfire. Another team had to be dispatched to rescue the first team.

The Vietnamese troops in Cambodia were thus not cowed, but they were put on alert. When the first bombing run proved ineffective, the decision was made to initiate a sustained bombing campaign, just as Washington had in 1965 against North Vietnam. Over the next year, the United States conducted 3,695 bombing raids in Cambodia, a number that came to represent 16 percent of all bombing being conducted by American B-52 forces in Southeast Asia. The net impact was to radicalize the Cambodian peasantry and push Vietnamese units farther into Cambodia. The sustained campaign took on the code name Operation Menu, and the specific targets became Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner, Supper, Snack, and Dessert. Because of the Nixon administration’s intense desire to maintain secrecy about the bombing, especially as regarded the media, Congress, and the American public, two sets of flight logs were created: one laid out the actual bombing targets in Cambodia, the other, official log put the targets in South Vietnam.Footnote 11

Arnold Isaacs indicated what the problem was from the outset: “American policy makers perceived Cambodia only through lenses that were focused on Vietnam.” But as he correctly pointed out, Cambodia was different. “Its culture, politics, history, and needs were different.” And that meant that the war would also be different, something completely ignored by the Nixon administration and military leaders. “Possibly for that reason, American actions there were enveloped from the start in ambiguity of purpose, official untruths, confusion, and controversy. In a sense, the act of deceit that began the American war in Cambodia – the secret B-52 bombing – set the pattern for everything that would follow.”Footnote 12

The initial and continuing justification for bombing was the search to destroy COSVN. As Isaacs noted,

COSVN was to occupy a bizarre place in the evolution of America’s Cambodia strategy. It was offered, like Eve’s apple, every time the military leadership sought to expand American actions there; in 1970 it became a famous, if chimerical, objective when Nixon himself called it one of the targets of the US “incursion” into the Cambodian sanctuaries.Footnote 13

But the Cambodian invasion was a year away. Nixon agreed to the bombing as a response to a new DRVN offensive in South Vietnam. He thought the North was testing him.

Overthrowing Sihanouk: 1970

The Nixon administration thus began the extensive and indiscriminate bombing of Cambodia in March 1969. Norodom Sihanouk faced a dilemma: he could object and thus alienate any possibility of reconciling with the Americans as a way of counterbalancing the growing North Vietnamese strength, or he could acquiesce by remaining silent and see the eastern portion of his country devastated by American ordnance. By choosing the latter, Sihanouk gave later cover to Nixon administration officials to claim that not only had Sihanouk known about the bombing, he had approved it, even though there was no evidence of any such agreement.

The bombing proved destructive to Cambodia but largely ineffectual in hampering North Vietnamese military actions in South Vietnam. Conditions in Cambodia deteriorated, and Sihanouk’s commitment to American actions came into question by members of the Nixon administration. Given the growing domestic discontent, Sihanouk erred in deciding to leave Cambodia in early 1970 to seek medical treatment in France. He was scheduled to be gone for two months. He would not return. The length of his rule, the severity with which he treated those he deemed insufficiently loyal, the way in which he humiliated or stifled those who challenged him, all came home to roost. “The Prince’s conniving at corruption, the authoritarian arbitrariness and economic incompetence of his rule,” Henry Kamm wrote, “his spiteful intolerance of those who would not be sycophants outweighed in the minds of educated Cambodians his principal achievement – warding off the ever-present menace of being drawn fully into the war of Indochina.”Footnote 14

The National Assembly voted unanimously to strip Sihanouk of his title on March 26, 1970. Although the initial thrust within the Cambodian government was to move Sihanouk toward a more aggressive policy against the North Vietnamese, when it became clear he had no such intention, and even more disconcertingly for those in the government, that Sihanouk planned to return and punish those who were advocating such a policy, what had begun as a movement to curb the prince’s power quickly became a full-blown coup d’état. Sihanouk compounded the situation by deciding to travel to Moscow and Beijing, instead of returning to Phnom Penh to confront his critics.

The announcement in Cambodia of Sihanouk’s ouster was greeted with great enthusiasm by the wealthy, the educated, and the middle class, as small as those groups were in Cambodian society. They had grown weary of kowtowing to Sihanouk or serving as flunkies in order to stay on his good side. “Among the educated, Sihanouk had clearly suffered an ever-spreading erosion of support that was inevitable after he had run the nation like a one-man show for a quarter-century. That he had led Cambodia imaginatively and peacefully to the restoration of its independence in 1953 lay too far in the past to matter much in 1970.”Footnote 15

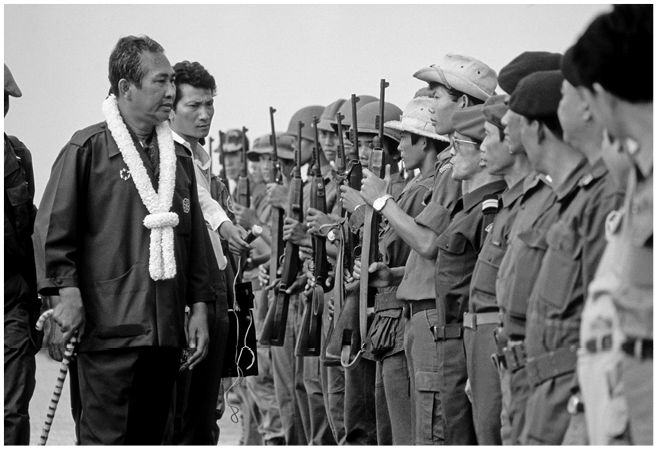

Sihanouk was replaced by his prime minister, Lon Nol, who had been a loyal follower, but who seized the opportunity and promised economic reforms, had political prisoners on both sides of the political spectrum released, and made sure that his military supporters knew that his ascension portended a return of American military aid. Prince Sirik Matak also abetted the coup, but he had personal reasons for wanting his cousin ousted, considering that he believed he should have been appointed to rule by the French in 1941. Predictably, the response in the countryside was much different. Peasants, farmers, and fishermen still adored Sihanouk, and rioting against the coup broke out in Kampong Cham. In one particularly grizzly scene, one of Lon Nol’s brothers, Lon Nil, was captured by the crowd, killed, and then cut into pieces, including having his liver cooked and then diced at a nearby restaurant with the pieces distributed to members of the crowd.

Lon Nol: 1970–3

Lon Nol was an unlikely war leader. Like so many in the Cambodian military, Lon Nol had originally been a civil servant at the time of Cambodia’s independence, and he had been given military rank by Norodom Sihanouk. As a reward for his loyalty, Lon Nol was promoted. He also had a younger brother, Lon Non, who also received military rank. Unlike the coup against Ngô Đình Diệm in South Vietnam in 1963 in which the Kennedy administration was explicitly involved, the extent of the Nixon administration’s involvement in the coup against Sihanouk is less clear. Lon Nol and Sirik Matak had complete confidence that the Americans would support them and acted accordingly. And they were right: the United States immediately recognized the new government and moved instantly to provide support.Footnote 16

Within weeks of Lon Nol taking over, the Nixon administration decided to involve Cambodia more fully in the war. The military justification to invade Cambodia in 1970 was the same as it had been to initiate the secret bombing the previous year: to degrade North Vietnamese troop strength in the sanctuaries on the border and disrupt the elusive COSVN as a way of protecting the American flank as Washington pursued the so-called Vietnamization of the war and withdrew its troops from South Vietnam. The invasion also served as a way of demonstrating American resolve to continue supporting the South Vietnamese government led by Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu and the new regime in Cambodia even as the United States scaled down its direct involvement in Indochina. South Vietnam remained the first priority; Cambodia was secondary.

But there was another reason for the invasion. April 1970 was a difficult month for Nixon. He had two Supreme Court nominees rejected by the Senate, and his mood darkened. He watched multiple showings of the movie Patton, starring George C. Scott, in which the actor portrays the World War II general as a brilliant and driven, if mercurial and misunderstood, leader. The gloomy, self-pitying Nixon felt an increasing need to demonstrate his authority and decisiveness to Congress, and invading Cambodia became the act by which he would do that, regardless of the costs. The initial plan was to use only South Vietnamese troops, but Nixon wanted more and a greater show of toughness, so he added American troops. Defense Secretary Melvin Laird and Secretary of State William Rogers were largely kept in the dark to ensure secrecy, especially since the State Department was seen as a major source of leaks by the White House. A suggestion was made to have General Abrams make the announcement as part of a regular briefing and as a way to emphasize the operation as something routine, but again Nixon was having none of that and wrote his own speech, which he delivered in prime time on the evening of April 30.

Figure 11.2 President Lon Nol of Cambodia reviews troops (1973).

Nixon began with a brief history of Cambodia by mentioning the 1954 Geneva Accords and then claiming, “American policy since then has been to scrupulously respect the neutrality of the Cambodian people” – except for the secret bombing, of course, which went unmentioned. Nixon offered a semantic clarification: “This is not an invasion of Cambodia.” Instead, it was an “incursion” designed to clear out sanctuaries that the North Vietnamese had created and been using to attack American and South Vietnamese forces. “We take this action not for the purpose of expanding the war into Cambodia but for the purpose of ending the war in Vietnam and winning the just peace we all desire.” Nixon explained that he made his decision in order to put “the leaders of North Vietnam on notice that” the United States would “be patient in working for peace”; he added, “we will be conciliatory at the conference table, but we will not be humiliated. We will not be defeated.” The speech then took a dark and gloomy turn, revealing more of the president’s mindset than perhaps he intended. “My fellow Americans,” he began, “we live in an age of anarchy, both abroad and at home. We see mindless attacks on all the great institutions which have been created by free civilization in the last 500 years.” He spoke about the systematic destruction of the great universities in the United States, an obvious reference to student protest against the war. Finally, Nixon inveighed, “If, when the chips are down, the world’s most powerful nation, the United States of America, acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world.”Footnote 17 Nixon went full Nixon, thinking that the “incursion” represented another one of his seminal moments, just like the ones he had described in his book, Six Crises. Nixon wanted to reassure the American people (but especially his critics) that he was up to the challenge.

Lon Nol was not consulted, let alone informed, prior to the invasion. Neither was the US Mission in Phnom Penh, which only found out by listening to Nixon’s address on radio. Lon Nol was officially briefed when US chargé d’affaires ad interim in Cambodia, Lloyd M. (Mike) Rives, rushed to visit him. Lon Nol was not happy and later spoke of the violation of Cambodia’s territorial integrity, but he did nothing. The invasion of Cambodia exacerbated and reinforced past relationships, both personal and institutional, and hardened opposing sides. The domestic reaction to the invasion drove Nixon even further into the depths of his darkest views about those who opposed him or those he suspected of insufficient loyalty. He visited the Pentagon the morning after the invasion and delivered a tirade that shocked his audience, which included the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCF) and the defense secretary. Nixon used “locker-room language” and spoke of “bold decisions,” and specifically cited Theodore Roosevelt charging up San Juan Hill during the Spanish–American War. General Westmoreland, now the army chief of staff, cautioned against unrealistic expectations, noting that the sanctuaries were not something that could be completely erased. Nixon dismissed him by replying, “Let’s go blow the hell out of them.”Footnote 18

Far from “electrifying people” in the way he had envisioned, Nixon’s actions divided Americans even further. Student protests erupted around the country and caused many college campuses to close before the spring semester was completed. The worst incidents occurred at Kent State University, where Ohio National guardsmen shot fifteen students, killing four, and Jackson State College, where city and state police killed two students and injured twelve others. Tensions mounted, and Nixon’s siege mentality worsened. In the early morning of May 9, Nixon made a visit to the Lincoln Memorial, where he spoke to a bewildered group of college students about football. Kissinger later claimed Nixon was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The situation in Cambodia worsened in obvious and predictable ways. Communist forces moved west, farther from the border and deeper into Cambodia. Lon Nol and the Cambodian Army were powerless to stop them. Of the Cambodian peasantry in the area, those who were not killed fled and became radicalized in the process. A Cambodian lieutenant captured by the Khmer Rouge who escaped after six weeks commented on who was doing the fighting: 70 percent were Cambodians, despite the government’s denial. “Their motivation was simple …: escape from the steady bombing, strafing, and napalming by American, South Vietnamese, and Cambodian planes, which were causing heavy civilian casualties. Yet the government steadfastly maintained that the Vietnamese met little success in recruiting Cambodians.”Footnote 19

Lon Nol issued a meaningless ultimatum to the North Vietnamese troops that they must leave Cambodia within seventy-two hours, an absurd demand. However futile Lon Nol’s declaration was, it stoked long-standing Cambodian animosity against ethnic Vietnamese living in Cambodia, who numbered approximately 400,000. The wholescale scapegoating of the ethnic Vietnamese began in March 1970, and the pageantry that surrounded it reminded one observer of his time growing up in 1930s Germany: “In its strident chauvinism and xenophobia,” verbal attacks on the Vietnamese “stirred in me unpleasant reminiscences from my childhood among the Nazis.” The situation only went from bad to worse. Those peasants from the countryside who were not killed, or did not join Khmer Rouge forces, fled to the cities, in particular Phnom Penh. A city of roughly 600,000 in 1970, Phnom Penh had a population of between 2 and 3 million by April 1975. In addition, the traditional economy collapsed. The military situation was no better. Khmer Rouge forces closed to within striking distance of the capital. They used mortars and 122mm rockets to strike at Pochentong airport and destroy the tiny Cambodian Air Force. When Cambodian troops initiated an assault to relieve the city of Kampong Thom, located north of Phnom Penh, in October 1971 as part of Operation Chenla II, the battle was initially declared a great victory when government troops took the city. And then North Vietnamese forces counterattacked, inflicting heavy losses. Lon Nol, who earlier in the year had spent two months in Hawai’i recovering from a stroke, and who was quite frail, visited the battlefield but then issued a set of contradictory orders. Sirik Matak and the leader of the group called the Khmer Serei tried to get Lon Nol to step down for the good of the country, but Lon Nol refused, and he continued to enjoy the full support of the Nixon administration.

In spring 1972, Hanoi launched a major offensive against South Vietnam, the so-called Easter or Spring Offensive. The massive effort meant that North Vietnamese troops were, for the most part, no longer in Cambodia. At that point, the war inside Cambodia became a primarily internecine affair, with the Khmer Rouge troops facing the Cambodian National Army. By year’s end, the Khmer Rouge army had grown to approximately 50,000 men. And just as importantly, the Khmer Rouge could, and did, act independently.

Paris Peace Agreement on Vietnam: 1973

The Paris Peace Agreement on Vietnam was signed on January 27, 1973, ending the direct American participation in the war in Vietnam. Article 20 of the agreement dealt with Laos and Cambodia. It stipulated that “foreign countries shall put an end to all military activities in Cambodia and Laos, totally withdraw from and refrain from reintroducing into these two countries troops, military advisors and military personnel, armaments, munitions, and war material.”Footnote 20 While that all sounded well and good, it set no deadline. The Nixon administration used that loophole to justify its resumption of the bombings of Cambodia in February 1973. Kissinger met with the American ambassadors to South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia on February 8 in Bangkok. He explained that all bombing strikes would be coordinated through the embassies in secrecy. This meant Cambodia, since the Paris Agreement on Vietnam prohibited American military activity in South Vietnam, and the situation in Laos had stabilized. Despite working with the ambassadors, Kissinger failed to involve Secretary of State William Rogers. “The Paris agreement did not bring even a fictitious peace to Cambodia,” one journalist commented at the time. Instead, “it brought a new paroxysm of violence and devastation.”Footnote 21

Over the next six months, the American bombing was carried out with a ferocity previously unknown, as Nixon sought to project the notion that he was a little crazy, a “madman,” with the expectation that this would compel the North Vietnamese, as well as the Khmer Rouge, to negotiate. Just as importantly, the savage bombing was a key component of Nixon and Kissinger’s idea about creating a “decent interval” between the time of the American withdrawal and the collapse of the South Vietnamese government. And now Lon Nol’s government became part of the equation. During the entire twelve months of 1972, US bombing of Cambodia came to 37,000 tons. In March 1973 alone, the amount came to 24,000 tons, followed by 35,000 tons in April, and 36,000 tons in May. B-52s were now unleashing monthly onto Cambodia what they had once dropped annually.

The bombing was designed to bolster Lon Nol’s government and the performance of his forces. It did no such thing. Corruption, known as “bonjour” to the Cambodians, remained rife in the form of officers padding payrolls with ghost soldiers and officers selling rice and equipment on the black market. Inflation skyrocketed, troops deserted, and morale sank as Lon Nol held firm to his mystical views of the whole situation, a view informed by monks who saw in the Cambodian civil war a long-prophesied challenge to the survival of Buddhism. The monks considered the Khmer nation to be the divinely chosen defender of the faith and saw in Lon Nol a savior of sorts. The Cambodian government was falling apart, and Lon Nol remained as aloof as ever. “Lon Nol’s ever-deepening belief in what monks told him of the future became the despair of those who had to deal with him about the present, both Cambodians and Americans.”Footnote 22

In March 1973, strikes led by teachers and students broke out in Phnom Penh. Lon Nol responded with force, using the secret police commanded by his younger brother to attack strikers. He closed newspapers critical of the government and even went so far as to place Sirik Matak under house arrest. Despite these circumstances, the Nixon administration never wavered in its support for Lon Nol. Congress began to think differently. When the Senate Foreign Relations Committee sent two experienced staffers to evaluate the scene, they reported that the political, military, and economic performance of Lon Nol’s government had reached an all-time low. What the two staffers also began to uncover was the extent of renewed US bombing of Cambodia and the lengths to which the Nixon administration had gone to conceal that bombing – even from key members of the administration like Secretary of State William Rogers.

Overshadowing all this was the specter of Watergate, and that specter came into fully realized form on April 30, as Rogers was about to go before Congress to answer questions about the bombing. Nixon announced the resignations of his two top aides, John Ehrlichman and H. R. Haldeman, as well as that of the attorney general. Up to this point, Watergate had been a nuisance; now it became a crisis, one that would dog the president until he resigned fifteen months later.

Nixon and most members of his administration believed in a Khmer Rouge largely directed from Hanoi and Moscow. That was not the case. As the bombing had begun in 1969, and then intensified from 1970 to 1973, the Khmer Rouge had become more independent. The DRVN provided logistical support through 1972, but since the Paris Agreement on Vietnam, Hanoi had been looking out for itself, and Khmer Rouge military activities threatened to jeopardize the economic aid promised by Nixon as a separate, secret codicil to the Paris Agreement. Diplomatic efforts to negotiate a ceasefire throughout 1973 failed for these reasons; the leverage simply was not there. Nixon, and especially Kissinger, blamed Congress. Upon learning of the secret bombing, and as the Watergate revelations became front-page news, Congress began to aggressively investigate the situation in Cambodia. The administration responded by lying and falsifying documents. That only made the situation worse. Congress pressed even more with additional hearings, and the administration’s façade began to crack. Congress tried to cut off funds for the bombing immediately, but the administration pushed back, arguing it would jeopardize negotiations and undercut American policy. Eventually, a compromise was reached: bombing could continue for six weeks. Nixon agreed and signed legislation on June 29, 1973 that gave the administration until August 15 to bomb.

Negotiations between Sihanouk, Zhou Enlai, representing the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and the Nixon administration went nowhere. Kissinger blamed the congressional decision to halt the bombing, but the parties were simply not going to agree. Kenton Clymer summed up Kissinger’s machinations nicely: “Kissinger’s diplomacy always offered too little and was too late and too secretive.”Footnote 23 Perhaps even more important, the Khmer Rouge were determined to achieve victory. By June 1973, the Khmer Rouge had turned on their North Vietnamese supporters and were evicting any remaining advisors. Hanoi, Khmer Rouge leaders believed, was focused on overthrowing the Thiệu regime, not on aiding the Khmer Rouge. But the Khmer Rouge leadership went further. In what was a preview of the post-1975 relationship between Cambodia and Vietnam, it pressed Vietnamese residents whose families had lived in Cambodia for decades, if not longer, to leave as well.

The Watergate scandal finally forced Nixon to resign on August 8, 1974, leaving it to Gerald Ford to assume the presidency. Ford, by his own admission, had been a hawk on the Vietnam War, and he indicated to members of Congress that he had no intention of changing now that he was in the White House. Toward that end, he followed Kissinger’s lead and once again requested emergency aid for Cambodia and South Vietnam. There had been reason for some optimism, given the way the Cambodian government had fought throughout 1974. Phnom Penh, for example, was no longer being attacked by Khmer rockets, and in some areas government troops had pushed back Khmer forces. It was not to last. Corruption, desertion, and a lack of supplies ravaged the Cambodian Army. Organizationally, Khmer Rouge forces grew stronger and controlled most of the countryside, as well as the roads and rivers. The Ford administration vainly sought a diplomatic solution through Sihanouk and the Chinese only begrudgingly and far too late. Instead, in January 1975 the administration pushed for initially another $1.5 billion in aid, which Congress reduced to $1 billion and then $700 million in military and economic assistance.Footnote 24 Congress reluctantly agreed to send a fact-finding mission to Cambodia, but time was running out. By February, it was clear the Lon Nol government was no longer tenable.

The evacuation of Phnom Penh, unlike the one that would occur in Saigon two weeks later, began on April 8 and went smoothly. Operation Eagle Pull involved helicopters from the USS Okinawa in the Gulf of Thailand landing on a soccer field next to an abandoned hotel and whisking away all remaining Americans and any Cambodians deemed to be at risk should Phnom Penh fall to the Khmer Rouge. Some of the latter, like Sirik Matak and Lon Non, elected to remain and became some of the first victims of the Khmer Rouge’s murderous rampage, which began after Phnom Penh fell to its armies on April 17, 1975. In assessing what caused the collapse, Henry Kamm wrote, “The way in which the Khmer Republic was born in 1970 – last-minute improvisations, borrowed forms devoid of meaningful content, and destructive blunders in the execution of plans – marked its life of four and a half years.” To make matters worse, “At the time the republic was proclaimed, about half of its territory was already occupied by North Vietnamese troops, Cambodian guerrillas organized by the Vietnamese, and, gaining strength rapidly, purely Cambodian units formed by the Khmer Rouge leadership.” In short, it was doomed from the start. Kamm added two additional causes, one internal and one external, for Cambodia’s collapse. “First was the unfathomable mélange of mysticism and dictatorial nonleadership of Lon Nol, combined with the relentlessly ambitious and divisive machinations of Lon Non.” Those two brothers oversaw an administrative structure that was both brutal and incompetent. “And second was America’s cruel exploitation of Cambodia’s uncomprehending, blind confidence that the United States would protect it and never let it down.”Footnote 25

The US withdrawal from Cambodia was quickly overshadowed by the dramatic end to the South Vietnamese government and the rush to evacuate all Americans, and as many South Vietnamese who had worked with the United States, as possible, at the end of April. Whereas the Cambodian operation had been handled without much drama beyond what would be expected under the circumstances, in South Vietnam thousands of Vietnamese crammed into boats of all sizes or took their chances at the airport, pressing against fences and holding children aloft. The final scene of an American helicopter atop a building when the airport became untenable, and the long line of Vietnamese stretching down from the roof on the stairway, spoke to the chaos that engulfed that ignominious departure. There was a coda, of sorts, to the American involvement in Cambodia: on May 12, the merchant ship SS Mayaguez was captured by Cambodian gunships, now manned by Khmer Rouge sailors, while traveling from Hong Kong to Sattahip, Thailand. They took the vessel and its crew to the nearby island of Koh Tong. With Kissinger’s encouragement, Ford made scant effort to negotiate the crew’s release and instead sent in marines on May 15. Although the crew of the Mayaguez was safely rescued, more marines lost their lives than there were members of the Mayaguez’s crew, and the crew was actually released by the Khmer Rouge troops and taken on a Thai fishing vessel to an awaiting US warship as the assault got underway. Despite the losses, Ford was enthusiastic about the operation, and his popularity rose with the American public.

Khmer Rouge Rule and Afterwards

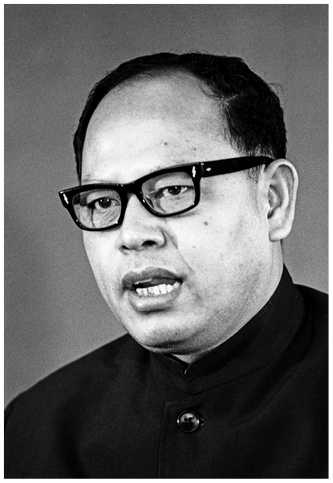

When the Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh, they already had indicated how they intended to rule. Led by a group of Cambodians educated in France during the 1950s, these individuals had returned to Cambodia only to face Sihanouk’s persecution. They fled to the countryside, where they began organizing. The Khmer Rouge was still very small in 1969, but as the US bombing ravaged the countryside, they found a growing supply of peasants ready to join their cause. They also became more radicalized. The leadership included Pol Pot (head of the party and originally named Saloth Sar), Ieng Saray (who served as diplomatic secretary), and Khieu Samphan (who served as military commander and who had written a doctoral dissertation while studying at the Sorbonne in 1959).

Figure 11.3 Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot in the Cambodian jungle.

Figure 11.4 Khmer Rouge Foreign Minister Ieng Sary.

Prior to their capture of Phnom Penh, the Khmer Rouge had depopulated other cities they captured. Now in control of Cambodia’s largest city, one that had swelled to over 2 million inhabitants, they implemented this policy for practical as well as ideological reasons. There was simply no way to effectively administer so many refugees in a city that only five years previously had had a population of 600,000. But there was much more to it than that. The Khmer Rouge leadership had a vision for Cambodian society that was strictly egalitarian (except when it came to them, of course), agricultural, and brutally enforced. People were forced out of the cities and marched into the countryside, regardless of age or physical condition. Thousands died and were left along the roadside.Footnote 26

Figure 11.5 Khmer Rouge leader Khieu Samphan.

In proclaiming Democratic Kampuchea, the Khmer Rouge leadership insisted it was the dawn of a new society. Gone was the past royal Cambodian society with its princes and kings, and along with it any vestiges of that age, including schools and governmental offices. Private property was abolished. Material goods were confiscated. The population was forbidden from wearing bright clothes. Personal relationships now came under the province of the government. Land was redistributed. And thousands upon thousands of people, real and imagined enemies of the Khmer Rouge revolutionary project, were tortured and executed.Footnote 27

The Khmer Rouge also amplified the anti-Vietnamese sentiment already running deep among Cambodians. Many of the 400,000 ethnic Vietnamese who were living in Cambodia in 1970 had fled or been killed by 1975–6, so the Khmer Rouge focused their attention on villages in Vietnam along the border with Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese government also disagreed over offshore islands. Relations with Hanoi deteriorated rapidly after 1975, reaching their nadir in 1977–8. Following a series of Khmer attacks on Vietnamese villages, Hanoi responded by invading Cambodia in December 1978. “Distrust eventually snowballed into paranoia,” Stephen Morris wrote. “This condition later led to Hanoi’s false belief that Beijing was instigating Khmer Rouge attacks upon it.”Footnote 28 This, in turn, led to a retaliatory invasion of Vietnam by China in February 1979. As Chinese paramount leader Deng Xiaoping explained to President Jimmy Carter and National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski while visiting the United States in January, China planned on teaching the Vietnamese a lesson.Footnote 29 The Chinese quickly discovered what the French and Americans had experienced: the Vietnamese were formidable foes on the battlefield.Footnote 30

In Cambodia, the Vietnamese clearly had the upper hand. Their troops were battle-tested after more than two decades of fighting US, South Vietnamese, and other allied forces. Their army was well supplied with Soviet and captured American equipment. The Khmer Rouge soldiers had no chance, and the government quickly fled Phnom Penh to the dense jungles along the border with Thailand. The Vietnamese then installed, in January 1979, a puppet government led initially by Heng Samrin and later by Hun Sen. And then the accounting began. Early testimony by fleeing refugees in 1975 had initially been disregarded by Western observers. Later, it became clear just how repressive and genocidal the Khmer Rouge government was, but after the Vietnamese invasion, the sheer magnitude of the horrors inflicted by Pol Pot’s regime emerged: estimates range from between 1.5 to 2 million Cambodians, including ethnic Vietnamese residents and members of other minority groups, killed between April 1975 and December 1978.

In what has to be one of the strangest twists, the United States, under President Carter’s leadership, backed the Khmer Rouge. Known as a champion of human rights, Carter supported the genocidal Khmer Rouge for entirely geopolitical reasons. After unification in April 1975, Vietnam had hoped to receive the economic aid promised by the Nixon administration.Footnote 31 Nixon had fallen victim to his own paranoia and illegal actions and resigned. President Ford never took up the matter, and so when Carter entered office, one of his first goals was to establish diplomatic relations with Vietnam. For their part, the Vietnamese wanted what Nixon had promised. Carter balked. By December 1978, the Carter administration announced the reestablishment of diplomatic relations with the PRC, the biggest supporters of the Khmer Rouge. Vietnam then signed a friendship treaty with the Soviet Union, and Brzezinski, putting on his best Henry Kissinger imitation, argued that continued recognition of the Khmer Rouge, despite the atrocities, was in the best interests of the United States and a way to stick it to the Vietnamese. As Henry Kamm acidly commented on the decision of the West, and particularly of America, to back the Khmer Rouge,

Faced with a choice between upholding the most tyrannical and bloodthirsty regime since the days of Hitler and Stalin, or a puppet regime put in place by an invader, it backed the tyrant’s claim to legitimacy. The elevation of sovereignty to the pinnacle of international virtue is a damning comment on the sincerity of the Western democracies’ constantly proclaimed advocacy of human rights.Footnote 32

Conclusion

The Vietnamese paid a price for their actions. Although the killing had stopped and they could now enjoy some basic human rights, Cambodians were not about to express their gratitude to being occupied by their historic rival. And the Vietnamese depended on assistance from the Soviet Union, so when Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985 and decided on a new course, Vietnam had to change as well, including opening its economy and negotiating an end to its occupation of Cambodia.

By the time the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991, Vietnam was out of Cambodia, and the latter became the focus of United Nations’ (UN) negotiations through the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) that ultimately resulted in elections in May 1993. The royalist party led by Prince Norodom Ranariddh, son of Norodom Sihanouk, won and formed a coalition government that included Hun Sen, but that coalition was forced on the royalists as the price for avoiding widespread violence instigated by Hun Sen and his followers, who were in no mood to give up actual power.Footnote 33 In September that same year, Norodom Sihanouk returned as head of state when the constitutional monarchy was restored, but, again, this was symbolic and little more. A personal account of the UN’s failure to ensure the integrity of the elections was offered by Benny Widyono. He served as a senior official for UNTAC during the election and remained in Cambodia as the UN secretary general’s personal representative until 1997.Footnote 34

David Chandler provided a historian’s perspective: “Cambodian history since World War II, and probably for a much longer period, can be characterized in part as a chronic failure of contending groups of patrons and their clients to compromise, cooperate, or share power. These hegemonic tendencies, familiar in other Southeast Asian countries, have deep roots in Cambodia’s past.”Footnote 35 The decade of the 1990s was no different, but at least after another round of elections in 1998, Cambodia was at peace and had become a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Conditions remained stark for millions, but there was no war, and the future had a tinge of brightness to it.