The Vietnam War had many beginnings. One of them was a three-story villa of French design that now stands at 606 Đ. Trần Hưng Đạo in Hồ Chí Minh City. Built in the early 1930s at what was then 96 Boulevard Galliéni, the property featured high ceilings and shuttered windows that saturated the interiors with light and vented the heavy, tropical air. Outside, a stately fountain greeted arriving visitors who ascended a broad central staircase to a portico with massive wooden doors. The portico was flanked by elegant curved staircases that swept dramatically around to the front. For the next forty years, the building had a knack for appearing to be more or less than what it was. It looked like a house, but no family ever resided there. It featured a red tile roof and ochre exterior walls – the aesthetic signifiers of French colonial authority – but it was not a government building. Its original occupant did, however, seek to implement a key French colonial policy: the so-called civilizing mission. The Société pour l’amélioration morale, intellectuelle et physique des indigènes de Cochinchine was a state-sanctioned French charity lottery that raised money to “improve” the “moral, intellectual, and physical” stature of Vietnamese people in the southernmost portion of French Indochina. Tenants of the building in the 1940s and early 1950s are unclear. But, as of 1954, the villa housed the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), the first Americans dispatched to Vietnam to bolster French and then Vietnamese forces in the fight against communism. In 1962, when Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) replaced MAAG as the American headquarters from which the coming war would be managed, most MACV staff decamped to a five-story office building on Saigon’s leafy Pasteur Street and then to a modern, custom-built complex at Tân Sơn Nhất Air Base on the outskirts of Saigon. The villa, reflecting its age with chipped paint and missing roof tiles, continued as “MACV II” until 1966 or 1967, when it was transferred to Republic of Korea forces. During this period, security imperatives overwhelmed the property, just as they overwhelmed economic and diplomatic efforts to shape South Vietnam. The welcoming fountain disappeared, the curved staircases were straightened, and the decorative perimeter wall ceased to be decorative and became seriously defensive. Photographs of the villa from the 1960s show it surrounded by sandbags, fencing, and barbed wire stacked twenty feet high. War had come to 606 Trần Hưng Đạo.Footnote 1

The evolution of this little piece of real estate reflects so much of American occupation in South Vietnam. When US officials first toured the property, they surely noted its ample square footage, its safe setback from the street, and the authority its grand staircases and imposing roofline asserted to passing Vietnamese civilians and departing French officials. Like southern Vietnam itself, whose long coastline and natural harbors offered strategic access to Chinese shipping lanes and future Southeast Asian battlefields, the villa suggested a good enough place to begin. Americans then set about continuing the work that the villa’s occupants had performed since its first stone was laid: offering help to rural South Vietnamese people – help that they did not request, in a manner that they did not support – from the comparatively modern confines of a European-style city. Nation-building was the top American priority in South Vietnam at the time, and building a Vietnamese national army to defend the nascent state was but one constituent part of it. In Inventing Vietnam, historian James Carter summarizes the effort: “The projects consisted of installing a president; building a civil service and training bureaucrats around him; creating a domestic economy, currency, and an industrial base; building ports and airfields, hospitals, and schools; dredging canals and harbors to create a transportation grid; constructing an elaborate network of modern roadways; establishing a telecommunications system; and training, equipping, and funding a national police force and a military, among others.”Footnote 2 It was an overwhelming to-do list that speaks to the depths of French colonial neglect and the ambition of American policymakers.

Security soon trumped all of these tasks, as Vietnamese resistance to both the Saigon government and the growing US military presence triggered a gradual reconsideration of American priorities. In October 1957, insurgents injured thirteen American servicemen and five civilians in three bombings around Saigon – including one outside the MAAG advisors’ villa.Footnote 3 In the early 1960s, armed resistance continued and accelerated under the aegis of the National Liberation Front (NLF), as North Vietnamese troops began streaming southward in ever greater numbers. The United States responded in kind, escalating its development of South Vietnam, especially ports, roads, and airfields capable of receiving the eventual arrival of American combat troops. Soon the size, scope, and lethality of the US military mission in South Vietnam surpassed what could be managed from an old French villa. For American officials, improvisation gave way to planning, adaptation of existing infrastructure gave way to new construction, and MACV replaced its villa headquarters with a high-tech air force base. For fear that political instability and security threats would topple the Saigon regime, the US military mission overwhelmed American nation-building efforts by 1965, spawning what Carter terms “the paradox of construction and deconstruction.” American military personnel and private contractors built staggering military and civilian infrastructure in just a few years’ time, which the US armed forces, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), Free World Military Forces, the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF), and the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) took turns destroying at equally staggering cost.Footnote 4 By 1966, the barbed wire that first protected Americans at 606 Trần Hưng Đạo had wound its way deep into the South Vietnamese countryside. There, it entangled millions of impoverished rural people, forcing them to navigate a highly militarized landscape dominated by American soldiers, spaces, and violence.

Little Americas at the Edge of the World

The United States was not alone in militarizing the South Vietnamese countryside, for the region had experienced almost continuous war since 1940 and endured a French military presence for decades before that. According to historian David Biggs, Việt Minh leaders in the Mekong Delta “realized the importance of claiming the slower-moving, everyday routes of movement – footpaths, canals, and creeks – not because this was all they knew but because it gave them advantages over the faster-paced, heavily mechanized forces of the French.” The National Liberation Front continued to rely on this “weblike infrastructure” a generation later.Footnote 5 In the 1950s, the regime of South Vietnamese president Ngô Đình Diệm “remilitarized” the Central Highlands by developing new ARVN bases and repurposing old French military infrastructure. Cần Lao Party operatives, under the direction of Diệm’s brother Cẩn, used a French bunker complex as a torture and interrogation center that supported a secret police and business network. And throughout South Vietnam, NLF and PAVN forces built networks of trails, roads, tunnels, and defensive positions. Long before American troops arrived in force, villagers in affected areas had learned to navigate military checkpoints and barricades that could lead to interrogation, forced labor, or enlistment for one side or the other.Footnote 6

Vietnamese militarization of the Southern landscape was considerable, but American militarization dwarfed it in every respect: size, sophistication, complexity, cost, and waste. American base development in South Vietnam was a spectacular exercise in environmental control, as Navy Seabees and US Army engineers etched firebases into narrow mountaintops and sculpted islands of dry land out of the Mekong Delta’s sodden soil. The decision to create a US base, of any type, was tactical, determined by enemy activity, local geography, and the mission. American bases always started spare, with construction personnel living in tents and exposed to the elements. Security, of people but also hardware, trumped comfort in the early days. But, once perimeters were secure, once the earth was tamped into runways and helipads, then construction priorities shifted to improving living conditions. Next came permanent billets, showers, laundries, and dining facilities, plus stable supplies of electricity and running water. Recreation and retail options were usually last, though command concern about troop morale and local civil–military relations sometimes drove on-post recreational facilities higher up the list of priorities. In relatively secure areas, off-duty soldiers liked to venture into local communities to shop and visit bars and brothels. These sojourns placed American soldiers at risk, more so from crime (drunken fights, getting robbed) than from enemy attack, though insurgents did target businesses patronized by American soldiers throughout the country, throughout the war. Given that only one-third of US forces in Vietnam were true volunteers, commanders were particularly concerned about the effects of boredom and antimilitary sentiment on soldier compliance and job performance. Both troop morale and security were best served, then, by building retail outlets and entertainments on American bases, even on forward bases directly engaged in combat operations. Over time, American bases in South Vietnam developed on a clear trajectory toward more and better: more amenities, better housing, and narrower disparity between warzone living and a stateside quality of life. The result was an archipelago of little Americas on the edge of a frontier that was defined, fluidly, by its proximity to violence.Footnote 7

An undated photograph from the archives of the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, the oldest and largest of the Department of Defense’s retail operations, succinctly makes American life in the Vietnam warzone legible.Footnote 8 It depicts a US Army soldier in a Vietnam PX in the late 1960s. At first glance, the cramped appearance of the facility indicates that it was a small store, and the soldier’s helmet – a requirement in contested areas but not on rearward bases – suggests not a large base on the coast or near Saigon, but rather a small installation further inland and closer to danger. Though small, the PX was probably very profitable, for comparable facilities sold tens of thousands of dollars in merchandise every month. At the peak of the PX system, the Vietnam Regional Exchange (VRE) managed 310 retail stores and 189 snack bars, and carried more than 3,000 items. With sales in excess of $1.9 billion for fiscal years 1968 to 1972 combined, the Vietnam PX system was effectively the third-largest department store chain in the world.Footnote 9

The goods in the photograph are also instructive, of American soldiers’ retail preferences. The soldier stands next to a shelf topped with cases of Juicy Fruit gum and baskets filled with M&Ms and potato chips. In one hand, the soldier manages two cans of Welch’s grape juice and some packets of crackers or cookies. In his other hand, he holds a stack of magazines. The magazine on top, Man Deluxe, promises “A Naked Feast,” a pull-out poster, and “Delicious Nudes!” In its cover image, a topless blonde woman kneels seductively on a chair. The soldier’s purchases (and the photograph of Planters Old Fashioned Peanut Candy that some concerned VRE staffer airbrushed into the photograph to conceal the pinup’s naked breasts) are entirely consistent with PX sales trends in Vietnam. In 1967, two years before US troop strength peaked, VRE was importing 120,000,000 pounds of consumer goods per month to meet American soldiers’ needs, including 260,000 cans of peanut products. The “nudie magazine” was one of millions sold to GIs in Vietnam, yielding $12,000,000 in annual sales. Behind the soldier in the photograph is a wall of suitcases, another common purchase, with VRE selling up to 300,000 pieces of luggage each year. American soldiers needed new luggage to cart home the purchases they made in the warzone, including souvenirs, custom-tailored clothing, and high-end consumer goods such as jewelry, watches, and cameras purchased at significant discount (relative to stateside prices) from the PX or its companion catalog. The US military’s generous “hold baggage” policy also provided free shipping for large items such as furniture, appliances, and stereo systems. Taken together, the PX system and myriad command policies affirmed that US troops in Vietnam were likely to carry home significantly more personal property than they arrived with at the start of their tours. The ability to shop was the linchpin of morale-building initiatives on US bases, making consumption a strange yet essential part of the American Vietnam War experience.Footnote 10

Depending on where the shopping soldier was stationed, his leisure hours were likely filled with copious amounts of alcohol. The US military’s beer ration allowed a soldier to purchase up to five cases per month, plus there was no limit on drinking at open mess clubs, the soldier-run drinking establishments (often with slot machines and live adult entertainment) that mushroomed throughout the occupation.Footnote 11 At the system’s peak, more than 2,000 open mess clubs on US bases in South Vietnam generated an annual gross income of $177 million.Footnote 12 There were wholesome forms of recreation, too, with the US Army building more than 1,300 athletic facilities by 1971. Most were graded fields and multiuse athletic courts, but they also included swimming pools, bowling allies, and golf courses. Day rooms, dark rooms, craft shops, libraries, entertainment centers (some with repertory theater companies), indoor and outdoor movie theaters, on-post steam baths and massage parlors (run by Vietnamese contractors), and recreational beaches rounded out the military’s war on boredom.Footnote 13

Though the soldier in the photograph is augmenting his diet with snacks, the US Army’s massive food program, which served all branches of the US armed forces in South Vietnam, tried to keep him well fed. The army’s model menu provided each diner with 4,500 calories per day, and 90 percent of meals served in Vietnam were hot, even if they had to be airlifted by helicopter to men in the field.Footnote 14 The US Army’s food effort involved erecting a dozen field bakeries to provide fresh-baked bread, with the largest capable of producing 180,000 loaves per day. Two private US dairy firms built plants in South Vietnam that were capable of processing 1.4 million gallons of milk, 160,000 gallons of cottage cheese, and 2 million gallons of ice cream for American soldiers every month. The US Army moved so much perishable food through the warzone that the largest American-built structure in all of South Vietnam was a massive cold storage warehouse in Quy Nhơn the size of six football fields.Footnote 15

The photo of the shopping soldier provides a window into the material conditions of daily life for Americans in Vietnam, but it also hints at the challenges of warzone military service. The soldier is a young man, but he looks tired. His uniform is big on him, suggesting he may have lost weight, as soldiers did on remote bases where they performed manual labor in stifling heat. (Soldiers on rearward bases in sedentary jobs tended to gain weight.) He also looks vaguely stunned – presumably the surprise of a flashbulb going off in his face while picking up sundries at the PX. But, given the capriciousness of the draft, a lot of American soldiers were stunned – to find themselves in the military, let alone in Vietnam, where they faced a year of soul-crushing challenges: monotony, military discipline, degrading tasks, awareness that stateside friends and family were moving on without them, proximity to violence, and an oppressive uncertainty about the future. Given the lack of control they must have felt, is it any wonder that GIs sought to exercise a little dominion over their lives by making choices in how to spend their paychecks? This juice, that magazine, this camera, that stereo – choosing what to consume made Vietnam seem a little more like home.

Some truths of the Vietnam warzone lay beyond the edges of a single photograph. Perhaps the most American aspect of US bases in South Vietnam was how they reflected and enshrined inequality. Just as regional, class, and racial disparities affected income and standards of living in the United States, these factors translated into disparities among the American soldiery in Vietnam. Bases most subject to enemy assault were the least well developed, so soldiers serving in contested areas suffered greater danger but also greater deprivation than personnel stationed in the rear. Militaries are inherently hierarchical and therefore classist, so officers (who were disproportionately white) always lived better than enlisted personnel stationed at the same installation. Race and class also played decisive roles in where and how soldiers served in the Vietnam War. Poor men who lacked formal education were more likely to serve in combat roles in contested areas. Until the army made major policy adjustments in 1968, African Americans were overrepresented among the ranks of the infantry. They also had fewer opportunities to advance in rank or access skilled assignments that would keep them safe. Due to inequities in the draft’s design, wealthy and well-educated men were unlikely to serve in the military at all, let alone in Vietnam. For example, of more than 29,000 graduates of Harvard, MIT, and Princeton’s undergraduate programs between 1962 and 1972, only twenty died in Vietnam. Meanwhile, poorer Americans were 68 percent more likely to die in Vietnam than richer Americans.Footnote 16 The American war machine could deliver on-post security in most places, most of the time, and it could deliver consumer goods and ice cream to the farthest corners of South Vietnam. But it could not create fairness or consistency for American military personnel. They counted down the days until they could return to “the World,” in constant and full awareness that the warzone’s deprivation was not equitably distributed, that its suffering was not universally shared.

The Collision of Wealth, Waste, and Poverty in South Vietnam

American military personnel may have regarded one another with envy – support personnel expressed respect bordering on awe for combat troops, while combat troops deeply resented so-called REMFs (“rear echelon motherfuckers”) for the relative comfort and safety that they enjoyed. But they united in shock and dismay at Vietnamese poverty, especially in rural areas. “I still can’t believe how these people live,” Paul Kelly wrote to his mother in 1969. “They’re just like animals. Way out in the middle of nowhere. There isn’t even a road for miles. It’s all just unused rice paddies,” he conveyed with a cruel and truly American understanding of “unused.” For John Dabonka, rural Vietnamese poverty was a lesson in gratitude. “I’m real glad I have what I have,” he wrote his parents. “It seems poor to you maybe, and you want new things because you think our house doesn’t look good, but after seeing the way these people live, there’s no comparison. We are more than millionaires to these people – they have nothing.” Sharing Kelly’s dismay, but not his contempt, Dabonka concluded, “I can’t see how people can live like this.”Footnote 17

The aesthetics of Vietnamese poverty were one thing, the consequences quite another. David Donovan, who served on an advisory compound in the Mekong Delta, recounts a horrifying story of preventable illness in his memoir. Twice, a mother brought her baby to the compound for assistance. The baby was covered with infected ringworm lesions, because the mother could not afford soap and firewood to boil water. The advisors provided a bar of soap and a shot of penicillin to address the baby’s secondary bacterial infection, but they did not have anthelmintic drugs to kill the ringworm. On the mother’s second visit, the baby she carried in her arms was dead.Footnote 18 Donovan’s story is a testament to US military priorities in South Vietnam, and also to the limits of American power: American advisors could summon an airstrike to kill insurgents, but they could not provide medication to kill worms. And they had no means to address the region’s crippling poverty, a key factor that drove South Vietnamese people to support the revolution, which promised land redistribution and modern improvements in rural areas after the war was over.

The United States did not create poverty in South Vietnam, but the US occupation certainly exacerbated it. By relying on massive firepower to disrupt the activities of the NLF and PAVN forces, the US military rendered much of South Vietnam’s countryside too unsafe for civilians to remain in their homes. As David Hunt’s study of Mỹ Tho shows, the war’s violence arrived in rural areas like a churning tide, casting about people who had tended the same plots of land for generations. Fear of American bombs caused some peasants to leave their villages, where homes were clustered together, and build isolated “field huts” in the middle of their paddies. (A single hut was a less enticing target for US Air Force spotters.) Others moved into government-run “new life” (strategic) hamlets, where they were safe from both American bombs and insurgent retaliation, but they were forced to service the hamlet itself, and they became dependent on short-lived government largesse to survive. Some families split up, with one or two members remaining behind in the ancestral family home while the rest moved to field huts or even to new locales in search of work. It was common for family members not to see one another for years.Footnote 19

The violence in the countryside had profound effects on South Vietnamese life, as one-third of South Vietnam’s population became displaced at some point during the war. South Vietnam went from being a primarily rural society to being a primarily urban one in just a few years, as millions of rural people took their chances on cities for the first time. The South Vietnamese economy also shifted from a primarily agricultural economy, in which 90 percent of the population were subsistence farmers, to a service economy that catered to Americans and wealthy Vietnamese. As journalist Philip Jones Griffiths observed in his 1971 polemic Vietnam Inc., “The only industry that exists in Vietnam is the ‘servicing’ of Americans,” because they were the largest group with disposable income.Footnote 20 Hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese people took jobs on American bases at one time or another. Women with education provided clerical support in American offices, but displaced farmers – primarily women, youths, and elderly people, since most able-bodied men were in military service for one side or the other – had only their strength to sell. They lined up outside bases each morning hoping to be selected for a day’s work digging trenches, filling sandbags, and performing unskilled labor as needed to keep American spaces tidy and secure. Others found a living in providing services directly to American soldiers. On post, “hooch maids” cleaned barracks, did laundry, and shined boots for $5 per soldier per month. Off post, Vietnamese people of all ages peddled wares, from handicrafts to heroin. Bars, car washes, and massage parlors offered steady employment providing legitimate services to American soldiers, but these businesses were also deeply entangled in the sex trade. Work of any kind was scarce, so a single Vietnamese worker – whether typist or professional girlfriend – might support a dozen family members. It was a fragile existence, with little hope of future prosperity but preferable to dying in an airstrike.

The services Vietnamese people provided to Americans situated their poverty alongside unimaginable abundance, divided by a hard boundary that American officials policed with vigor. Inflation in South Vietnam was rampant, with the cost of rice (a principal economic indicator) rising 385 percent between 1965 and 1970.Footnote 21 The spending of American soldiers on the Vietnamese economy was a primary driver of inflation, which US officials addressed by creating dining, entertainment, and retail options to confine American spending to American bases. But US officials also tackled inflation at the expense of impoverished “local national workers.” They set their wages below market rate, then supplemented the artificially low wages with rice. Americans further contributed to Vietnamese poverty by coming down hard on workers accused of “theft.” Vietnamese kitchen staff might scrape “from a single troop’s discarded tray enough to live on for a week in the Vietnamese scheme of things,” as one American veteran recalled.Footnote 22 But if they took even one soggy hamburger bun home, they would be fired. American military police searched Vietnamese workers for pilfered items before they left US bases, even items pulled from the garbage. Even garbage outside American bases was off-limits to Vietnamese scavengers, who combed American dumps for any item that could be used, eaten, or sold. This scavenging could theoretically benefit insurgents, who fashioned discarded canteens and spent shell casings into lanterns and improvised explosive devices. But more commonly, desperate people compiled bits of aluminum to recycle for cash, or they used discarded materials to build improvised shelters. Some base commanders booby-trapped the dumps or set them ablaze to discourage this behavior. The United States preached initiative, self-reliance, and the acquisition of property to Vietnamese people as part of its nation-building efforts. Then it punished them for doing just that.Footnote 23

The war’s violence, displacement, and inflation met with American exploitation to degrade Vietnamese people and, in turn, their culture. Traditional Vietnamese culture revered learning, prized chastity, honored the elderly, and emphasized duty to family. The sacred obligation to family was the last to go, as Vietnamese people did what they must to sustain their loved ones. In her memoir, Dương Vân Mai Elliott recalls how urban, elite South Vietnamese lamented “that the American presence had turned society upside-down”:

In the old days, the social order was expressed in the saying “scholars first, peasants second, artisans third, and merchants fourth.” But now, according to these disillusioned traditionalists, this saying should be changed to “prostitutes first, cyclo drivers second, taxi drivers third, and maids fourth.” Money, not intellectual achievements or social usefulness, had become the yardstick of success.Footnote 24

Jones Griffiths documented this inversion of values in Vietnam Inc. His photographs capture disturbing scenes of Vietnamese debasement: prostitutes soliciting customers on the street, adolescent boys working as pimps, child pickpockets rifling through off-duty soldiers’ pockets, elderly people warehoused in Catholic-run institutions, children collecting discarded Budweiser cans by the hundreds from an American dump, families living in shacks made from soggy C-ration boxes, and displaced people using a Đà Nẵng graveyard as a communal toilet. “Prevailing economic conditions make it necessary for most Vietnamese to steal, simply to live,” Jones Griffiths explains. “The closer they are to the Americans with their ‘waste economy,’ the easier it becomes.”Footnote 25 In her memoir, Elliott similarly observes otherwise good people rationalizing their actions. “Taking from Americans was not really wrong, first of all because they were foreigners and normal ethical principles need not be applied to them, and, second, because they had so much that they would not miss what they lost.”Footnote 26 Elliott’s observation was prescient, for the United States poured nearly a trillion dollars into the Vietnam War, yet it failed to achieve its principal objective: an enduring, independent, noncommunist South Vietnam. The loss of American life, though, was surely noticed – and deeply felt – by the American public. But American material abundance in South Vietnam hardly drew care or critique in the United States, to say nothing of remembrance, even though American soldiers were dying for it.

Abundance versus Austerity in the Vietnam War

Though the American public recalls the Vietnam War principally through combat operations and regards the iconic Vietnam War experience as that of an infantryman humping the boonies, the numbers tell a different story. The American way of war requires a robust logistical apparatus to facilitate the combat arms’ lethality, complicating efforts to fight efficiently. US forces’ “tooth to tail” ratio in Vietnam was lopsided throughout the war. In the early 1960s, when US efforts focused on hardscaping the Vietnamese landscape in anticipation of wider war, construction battalions, private military contractors, and officers charged with advising South Vietnamese forces dramatically outnumbered American troops capable of producing violence. As US involvement escalated between 1965 and 1967, the increase in American combat troops triggered a disproportionate increase in the number of American support personnel. By 1967, only 49,500, or about 10.5 percent, of more than 473,000 American troops in South Vietnam were infantry. Combat support personnel – artillerymen, combat engineers, and airmen – comprised an additional 14 percent. The vast majority of US troops – 75 percent – were combat service support. They cooked food, repaired appliances, facilitated communication, provided entertainment, moved paper, and otherwise managed what went where. The ratio continued to widen, with support and administrative personnel topping 90 percent in 1972, when only 2,400 of the remaining 50,000 American troops in South Vietnam were capable of fighting the enemy on the ground. As historian Michael Clodfelter concludes, “The United States tried to fight a war in Indochina with eight times as many clerks, cooks, truck drivers, and telephone operators as grunts, cannon-cockers, tankers, and other combat personnel.”Footnote 27 American technology and firepower enabled a relatively small concentration of combat troops to inflict staggering damage on Vietnamese people and property, but securing South Vietnam’s long-term future proved elusive.

As striking as the statistics are, the relatively low number of American combat troops was not the problem, as evidenced by their ability to cause high North Vietnamese, insurgent, and civilian casualties. Rather, the problem was the high number of support personnel, whose presence in the warzone complicated civil–military relations and siphoned critical resources away from the shooting war. The abundance with which American troops were kitted addressed, but did not resolve, low soldier morale. At the same time, it was a heavy drain, necessitating incredible resources to ensure its security, which in turn affected local Vietnamese people. As American bases expanded in area, perimeters required increasing numbers of troops to guard them. As US forces occupied more territory, roads and bridges required constant maintenance to resupply them. And the materiel circulating throughout the warzone – the weapons, ammunition, equipment, MREs (meals ready-to-eat or field rations), and gasoline that supplied the shooting war, but also the beer, perishable food, consumer goods, and entertainments designed to insulate American military personnel from hardship – required US soldiers to prevent theft or destruction. At the same time, the US occupation had devastating effects. A nearby American base might mean security for villagers who feared the NLF and jobs for those displaced from their land. But that base also foretold combat operations that dispensed indiscriminate violence, local markets dominated not by affordable necessities but by expensive black-market goods, and the proliferation of bars and brothels to service American soldiers. The American war machine drove South Vietnamese people to support the revolution, or at least to withhold their support from the Saigon government, which amounted to the same thing. The process was both cyclical and spiral: the resources with which the United States fought the war necessitated ever greater resources to protect them. The larger the American footprint in South Vietnam, the more difficult the campaign to win Vietnamese hearts and minds.

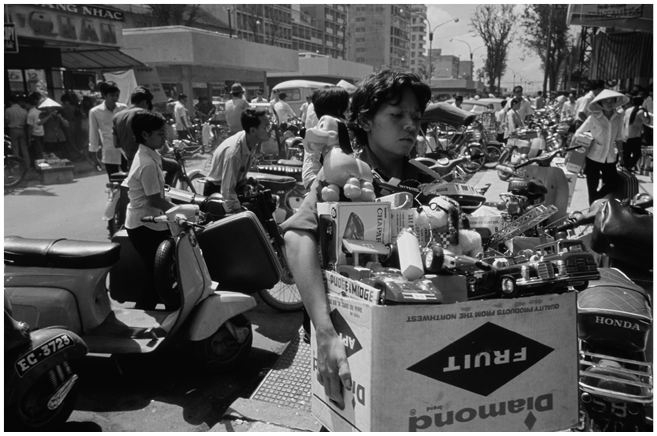

Figure 6.1 A shopper carrying merchandise purchased on the black market, which traded in US Army–issue items as well as general American goods (August 15, 1970).

The 101st Airborne Division’s security plan for a performance of a United Services Organization (USO) show at the Phu Bai Eagle Bowl, a massive outdoor amphitheater, demonstrated American military capabilities and priorities in action. Titled “Project Denton Beauty,” the base commander named the plan for the show’s star attraction, Miss America Phyllis George, who hailed from Denton, Texas. With a crowd estimated at 8,300 US servicemen, the security plan’s first priority was safely funneling area soldiers into the venue by deploying military police to direct traffic and conduct spot-checks of audience members for weapons and explosives. Project Denton Beauty also addressed external base security to protect both the audience and performers from enemy attack. Plan elements included aerial reconnaissance flights and ground patrols to detect enemy activity in the greater Huế–Phú Bài area, aerial rocket artillery fire to suppress enemy forces, three helicopters and a medic on standby to evacuate Miss America in the event of enemy attack, and a “chase team” of helicopters and combat units to pursue hostile forces.Footnote 28 These resources – the envy of PLAF or PAVN troops who lacked airpower, transportation, and a steady supply of ammunition – provided security only during the show. The show itself demanded additional resources: an enormous plot of land sculpted into a US base, seating for 8,000 people, a full-service stage with dressing rooms, sophisticated sound and lighting systems, transportation and housing for the performers, and reliable utilities to pull it all off. Miss America’s performance at the Eagle Bowl was among the grandest productions on the entertainment circuit in South Vietnam, but the circuit itself was vast. The USO sponsored some 5,500 performances during the war, and the US Army’s Special Services sponsored thousands more. Whether elective or essential for morale, these entertainments exacted a cost: soldiers and airmen risked their lives to keep audiences and entertainers safe.

The broader American security effort in South Vietnam enjoyed mixed success. On the one hand, Miss America and the vast majority of entertainers who toured the warzone experienced nothing of the shooting war. (The same could be said of most American military personnel.) On the other hand, US forces were often powerless to prevent war materiel from going astray. A robust black market developed alongside the capitalist, consumerist economy American policymakers hoped to build, as black marketeers purchased, peddled, and stole for profit, politics, or a bit of both. American logisticians’ “push” method of supply, which flooded South Vietnam with goods, created two areas of opportunity for criminals and insurgents alike: ports and trucks. In South Vietnam’s ports, the United States imported more war materiel than port workers could efficiently unload, leaving shipping containers stacked up and largely unguarded for weeks at a time. Once supplies were offloaded at South Vietnam’s ports, private contractors drove them up-country in convoys of heavy trucks, including eighteen-wheelers. The US Army provided security to prevent hijackings en route, but goods still disappeared at a staggering rate. Cornelius Hawkridge, a security employee of Equipment Incorporated,Footnote 29 conducted his own informal investigation of corruption in South Vietnam, culminating in testimony before a US Senate subcommittee. He reported an incident in which one convoy, despite having a US military escort, lost forty-two of sixty-eight truckloads of cement in one night.Footnote 30 Profits, not patriotism, account for the trucking contractors’ indifference to their losses: US taxpayers insured 100 percent of private shipping in the warzone.

Missing cement was not the half of it. Missing gasoline, stolen from private stores but also from the US military’s fuel supply, was a problem throughout the war. In 1971, the US Army provost marshal reported the illegal “diversion” of 1.3 million gallons (4.9 million liters) of fuel from US military stockpiles into the civilian economy in the Saigon area alone.Footnote 31 In 1969, Life magazine reported that 10–12 percent of all cargo transported in South Vietnam by a single trucking company was lost to pilferage or hijacking in 1967 and 1968. Life’s interviews with American contractors also reveal startling information about the 1968 Tet Offensive: “just before the Tet offensive, hijacking of C-rations and medical supplies reached an all-time high.” As one American transport foreman put it, “When the Tet offensive came, we fed ’em, shot ’em and then we provided the medicine to treat ’em.”Footnote 32 US military authorities knew the danger the black market posed, because they constantly entreated American servicemen not to participate. As a typical GI newspaper warned readers, “In effect, the money you place on the black market could purchase the weapon used to kill you.”Footnote 33 Hawkridge, an ardent anticommunist himself, questioned whether a war so corrupt was worth fighting. American military personnel died providing security for goods transported through the warzone. When military commanders wrote to grieving mothers about their sons’ sacrifices, Hawkridge wondered, did the letter “say that their son had gladly given his life for twenty thousand cocktail shakers?”Footnote 34

For all the abundance the United States could direct toward soldier morale and the war effort, the United States’ ARVN ally operated primarily from a position of scarcity. To be sure, the United States spent billions trying to recruit, train, equip, and support the ARVN, but that investment did not often reach the average ARVN soldier. The Saigon government relied on an oppressive draft to staff its armed forces, which deprived impoverished rural families of essential support from their sons for years on end. Conditions on active duty were bad. ARVN barracks were overcrowded and poorly maintained, and ARVN soldiers reported that they seldom had enough to eat, which contributed to high rates of illness. Medical care was inadequate, especially for those injured in combat. Adding insult to literal injury, ARVN soldiers had the cost of food deducted from their pay, which was so low to begin with that food alone accounted for one-third of their annual salaries. Perhaps most concerning, ARVN training usually consisted of being read to from American manuals. Infantrymen sometimes drilled with broomsticks, and combat training seldom involved live-fire exercises. The first time many ARVN soldiers fired their weapons was in actual combat, when their lives depended on it. As a result of these deficiencies, which were compounded by inadequate political education, ARVN soldiers suffered terrible morale, which in turn led to poor performance in the field and devastating rates of desertion.Footnote 35

And what of the revolution’s soldiers and supporters? How did American abundance sit with them? Most obviously, it meant that US forces could direct incomprehensible firepower at even a lone NLF insurgent, a practice that spared American life but led to astonishing Vietnamese civilian casualties. Civilian casualties in turn stirred anger toward American and Saigon soldiers, while civilian displacement affirmed the revolution’s messaging about South Vietnam’s lopsided distribution of wealth. Indirectly, the American presence altered the contours of South Vietnamese life in ways that tended to benefit the revolution. The proliferation of Western consumer goods, even in rural areas, shifted Vietnamese customs and aesthetics: modern clothing, contemporary music, long hair for men, big hair for women, and, for the wealthy, surgically altered eyelids that offered a more Caucasian appearance.Footnote 36 The alteration of Vietnamese culture further underscored the urgent need to drive the “foreign aggressors” from Vietnam, because Vietnamese identity itself was at stake. Ultimately, American success or failure in the war did not rest on the production of violence – at which US forces excelled – but rather on the United States’ ability to win the support of the Vietnamese people. Prioritizing the shooting war impoverished efforts that could have – in theory, if implemented thoroughly and without corruption – created generalized prosperity, instead of fast fortunes for South Vietnamese elites.

Compared to the decadence and corruption of South Vietnam’s ruling class and the wealth of the American occupier, the asceticism of the average North Vietnamese or NLF recruit was both pronounced and politically charged. The revolution’s soldiers usually shared their ARVN counterparts’ lean material circumstances. PAVN and PLAF fighters were lightly equipped with materiel carried overland via the Trường Sơn (Hồ Chí Minh) Trail or smuggled into South Vietnam by boat. The choice to throw a grenade or fire a rocket was made carefully, given the difficulty of resupply. Food was often inadequate. North Vietnamese forces had to forage on the march, and insurgents planted cassava to survive. Medical care lagged far behind what American or even ARVN units could provide, given the lack of timely evacuation from the battlefield. The revolution’s field hospitals and clinics lacked medications, equipment, and power, with some determined medical staff peddling bicycles to power lights for surgery. For seriously injured soldiers whose war was over, the return to North Vietnam meant being carried on a litter for a thousand miles. North Vietnam also deployed an army of porters, laborers, and ordnance disposal specialists to keep Trường Sơn Trail traffic moving in remote areas. Young women returned from years of dangerous nighttime work “hairless with ghostly white eyes” and sterile from malnutrition and disease. Malaria plagued fighters and support workers at such high rates that it was not regarded as a serious malady. The constant threat of American bombs, artillery, and soldiers took its toll. And yet, Vietnamese insurgents and fighters – hunted, hungry, and homesick – did not want for belief. Their enduring morale was sustained through relentless propaganda that North Vietnam’s youth had imbibed since infancy. Heavy emphasis on political education, even in the field (PAVN and PLAF units commonly had a political officer), forged a strong sense of purpose that was strengthened through shared struggle. Vietnamese people who sacrificed for the revolution believed that they had righteousness on their side.Footnote 37

In contrast, US military authorities ceded the moral high ground to the insurgency by shooting and spending lavishly, to prevent American casualties and sustain the morale of American troops – or so it appeared, from the perspective of Vietnamese people whom both sides were trying to sway. The import of this strategy was not lost on insurgent leaders. Vietnamese scholar Nguyễn Khắc Viện describes the role that austerity – abundance’s foil – played in winning adherents to the revolution. For decades, communist militants used the essay “Let’s Change Our Methods of Work” as a manual for how the Southern cadres should comport themselves. Originally published by Hồ Chí Minh under the penname “XYZ” in October 1947, the essay leverages familiar Confucian concepts to explain revolutionary virtues in commonsense terms, the better to appeal to a broad Vietnamese audience. For example, “Let’s Change Our Methods of Work” instructs people to lead lives of simplicity and virtue. The ideal cadre “will not hesitate to be the first to endure hardship and the last to enjoy happiness. That is why he will not covet wealth and honor, nor fear hardship and suffering, nor be afraid to fight those in power.” Viện explains further, “Having integrity [the Confucian concept of liêm] means not coveting status or wealth, not seeking an easy life or not willing to be flattered by others.” In a related essay, Hồ Chí Minh elaborates – pointedly, given the disparity in resources between French and Việt Minh forces at the time – on the relationship between frugality and integrity: “Lavish spending begets greediness.”Footnote 38 Through this messaging, communist leaders made a literal virtue of necessity, which was essential given their impossible task, of resisting an enemy with limitless resources. The rank and file heard them. “Everybody in the world, not the Vietnamese alone, knows that America is a rich country and has all modern weapons,” explained a captured insurgent. “But modern weapons do not make the United States win this war … I think this war will last a long time and the Vietnamese people will certainly win it. The Americans are engaged in an aggressive war which is nonrighteous and they will lose it.”Footnote 39

He was right. The United States lost the war, in that it failed to achieve its political objectives. And yet loss seems to define the Vietnam War, on all sides. South Vietnamese people suffered a loss of identity, as urban Vietnamese culture twisted itself into a simulacrum of American culture that emphasized individualism, consumption (especially of Western brands), and Western aesthetics. Some South Vietnamese people suffered a loss of country when the Republic of Vietnam ceased to exist in the spring of 1975. Vietnamese people on both sides of the 17th parallel lost homes, farms, businesses, and the autonomy those possessions afford. They lost time – years – to spend with family as the war pulled them apart. They lost access to family tombs where they honored their ancestors, they lost loved ones in this life, and they lost their own lives. The losses pile up, one atop the other, so high that it is difficult to discern a victory emerging from the stack. It is also difficult to discern a lesson emerging from the war. Perhaps it is this: Vietnamese people fought with everything they had to repel the “American aggressors” from their country, yet their country lay in ruins after. The United States fought with but a fraction of its wealth yet still managed to saturate South Vietnam with military hardware, consumer goods, and violence. It was simultaneously too much and not enough: too much to defend South Vietnam without altering it irrevocably, yet not enough to silence Vietnamese resistance once and for all.

Coda

The Vietnam War had many endings: the big ones in 1973 and 1975, but also millions of little ones, as individuals succumbed to their injuries, as survivors finally made their way home. When it was all over, the United States left behind so much infrastructure and investment in South Vietnam that it continued to sustain Vietnamese people decades later. In 2006, my dad and I visited the remnants of LZ English (near Bồng Sơn), a mid-sized base where he spent six months late in the war. All traces of the base’s buildings were gone, but the airstrip was beautifully intact, as if prepared to receive a planeload of American supplies and reinforcements at any moment. The locals were using the airstrip to dry cassava, which was laid out in large, tidy squares. A pack of children on colorful bicycles joyfully cruised the level pavement of the wider turnaround, stopping every now and then to eye us foreigners with wariness and amusement from a distance.