1 Introduction

The prevalence of insufficient physical exercise is 36.8% in high-income Western countries and has been increasing over the past two decades (Guthold et al. Reference Guthold, Stevens, Riley and Bull2018). Given the overwhelming evidence of the long-term health benefits of regular exercise and the related short-term benefits of improved well-being, such low levels of physical activity are both surprising and worrisome. Research has pointed towards behavior that deviates from a standard rational-economic model to explain underinvestment in preventive activities. One explanation for the lack of exercising is ‘limited attention’ (e.g., Dean et al. Reference Dean, Kıbrıs and Masatlioglu2017), which describes that individuals have limited cognitive ability and therefore may forget to exercise during busy day-to-day life.Footnote 1

In this paper, we provide new evidence on the importance of limited attention in the repeated decision to exercise, using detailed data from a large health club in Sweden. We evaluate a randomized experiment among almost 2500 gym members in which we sent weekly email reminders to half of the sample. We find a strong and robust positive effect of these reminders on the number of gym visits during and after the intervention, for nearly all types of individuals. This result is most naturally explained by the prevalence of limited attention among gym members.

Our setup is related to the study by Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017), and our contribution lies in (i) the use of a large sample size, allowing for more precise estimates, (ii) a sample of gym members who are arguably more representative of the general population than those used in previous studiesFootnote 2, and (iii) a gym that offers a wide variety of activities, ranging from regular weightlifting to ball sports, yoga, cycling, swimming and dancing classes.Footnote 3 All of these factors speak towards strong external validity of our analysis. Furthermore, our paper is the first to identify whether the reminder emails were actually opened, allowing us to investigate whether opening the email is related to a behavioral response. Finally, we observe the booking and canceling of gym classes, allowing investigation of the making of plans to exercise in the future.

We sent weekly reminders during a three-month period to gym members who had recently purchased an annual membership.Footnote 4 While the content varied across weeks, the emails were always short and encouraged regular visits to the gym. We find that email reminders lead to a substantial and statistically significant increase in gym visits of 13%.Footnote 5 The effect appears to be somewhat larger for class training (19%) than for free training (11%), although the difference is not statistically significant. These estimates follow from a difference-in-differences (DiD) model in which we control for a slight pre-experiment difference in attendance between the control and treatment groups, but we find similar effects when using simple differences. These findings are robust to a number of different specifications. Furthermore, the positive impact of email reminders applies to nearly all types of individuals (students, nonstudents, men, women, etc.), except that low attenders (based on the pre-experiment period) seem to benefit substantially more than high attenders. This finding is not surprising, given that high attenders typically have a lower scope to increase their exercising frequency.

When extending the observation period to three months after the last reminder was sent, we find evidence that the positive effects of reminders persist (visits remain 12% higher in the treated group). We interpret this finding as a sign of habit formation, although it should be noted that these results are less precise than those for the experimental period and slightly smaller in some robustness checks. Furthermore, due to lower baseline attendance in the postexperiment period, the same percentage increase implies a lower increase in absolute terms. We do not find any effects of the reminders on the duration or renewal of membership contracts, which initially lasted 12 months.

Comparing our results to Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017), we find a significant effect of the reminders for the whole sample and not only for low attenders. For the latter group, we find a 16% increase in weekly visits, which is 10%-points smaller than the effect in Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017). In addition, our postexperiment effects are significant for the whole sample, while Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017) find no significant postexperiment effects for the whole sample (although their effect size is similar).

We also use novel data on class bookings and cancellations of bookings to document how individuals plan their future gym visits and how they change their plans over time. We find that the majority of individuals who attend classes plan their class attendance several days in advance of the class (by making a booking), but a significant share of class bookings (42%) are canceled, most of those (82%) on the day of the class. This suggests that many individuals change their plans at short notice. With respect to the effect of the email reminders, we find that class attendance is affected through an increase in the number of bookings and a lack of an increase (or even a decrease) in the share of bookings that are canceled (though these results are less precise).

The positive impact of regular reminders on gym visits (and the significant share of bookings that are ‘forgotten’Footnote 6) can best be explained by the prevalence of limited attention, which is loosely defined as decision makers not taking their full set of choices or actions into consideration, due to cognitive limitations.Footnote 7 In the context of exercising, gym members may forget to visit the gym on a particular day, forget to book a gym class in advance or forget to attend a previously booked class. Reminders are a potential remedy for limited attention because they can direct people’s attention to a particular choice or action and thus make the execution of this choice or action more likely. In the conclusion, we argue that alternative explanations for the effectiveness of reminders are less plausible.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the setup for the reminder experiment. In Sect. 3, we analyze the effects of reminders on the number of gym visits, class bookings and cancellations as well as on contract renewal. Section 4 provides a discussion of plausible mechanisms and concludes.

2 Experimental setup

Below, we describe the health club at which our study was performed, the selection of the experimental sample, the randomization procedure, and the setup of the reminder experiment.

2.1 The health club

The study was carried out in collaboration with one of the largest health clubs in Gothenburg, Sweden. The club is a nonprofit organization, has four facilities and records over 800,000 visits per year. Three facilities offer free workout areas, as well as a large range of group exercise classes led by fitness instructors (more than 200 per week). The fourth facility is a large climbing hall. Contracts can be bought for access to a single facility, or to all facilities (‘Multi card’). Access to each of the four facilities requires the scanning of an electronic membership card. Participation in a group exercise class requires an additional scan. Gym attendance is thus almost perfectly observed. Because many classes are at risk of being crowded, each class has a participant limit, and members can sign up for classes in advance. We discuss the booking and cancellation policy in Sect. 3.4.

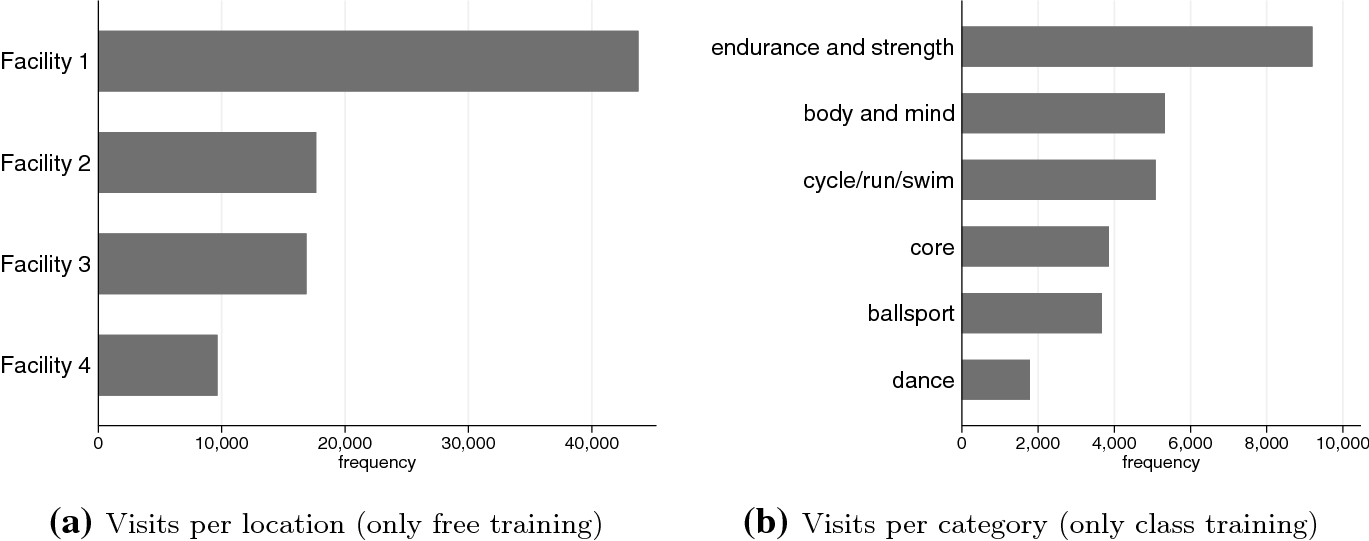

Fig. 1 Gym attendance (July 1, 2016–June 30, 2017)

2.2 Sample selection, randomization and balance

From the health club, we received all data on gym attendance, class bookings, class booking cancellations and class no-shows for the time period from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017, for all individuals who purchased a 12-month contract between July 1, 2016, and December 1, 2016 (2881 individuals).Footnote 8 We select individuals who remained active members on December 1, 2016, which was true for almost all members, as an annual membership cannot be canceled during its duration.Footnote 9 Furthermore, we exclude members who did not provide a valid email address when registering with the gym, leaving us with a final sample of 2463 gym members.

In Fig. 1, we show attendance statistics for this sample. Altogether, we observe 115,963 gym visits, of which 88,217 are free training and 27,746 are class attendances. Panel (a) shows the distribution of free training visits across the four facilities. Facility 1 is the most popular facility, with 55% of all visits. The gym classes vary across more than 37 different types, which we break down into six categories. The distribution of participation across these six categories is presented in panel (b) of Fig. 1, while the distribution of visits across all 37 specific class types is shown in Fig. 1 in the Online Appendix. The most popular classes are indoor cycling (spinning), bodypump (muscle strength training using free weights) and yoga.

Table 1 Pre-treatment characteristics of the treatment and control groups

|

Control group |

Treatment group |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

mean |

sd |

min |

max |

mean |

sd |

min |

max |

p-val. t-test |

|

|

Age |

30 |

10 |

14 |

79 |

30 |

11 |

16 |

80 |

0.77 |

|

Male |

0.59 |

0.49 |

0.58 |

0.49 |

0.50 |

||||

|

Student |

0.51 |

0.50 |

0.54 |

0.50 |

0.10 |

||||

|

Recurring member

|

0.49 |

0.50 |

0.44 |

0.50 |

0.01 |

||||

|

Membership type: |

|||||||||

|

Multi card (and CrossFit)

|

0.41 |

0.49 |

0.40 |

0.49 |

0.66 |

||||

|

Facility 1 |

0.32 |

0.47 |

0.34 |

0.47 |

0.43 |

||||

|

Facility 2 |

0.10 |

0.30 |

0.10 |

0.31 |

0.73 |

||||

|

Facility 3 |

0.12 |

0.32 |

0.10 |

0.30 |

0.34 |

||||

|

Facility 4 |

0.05 |

0.23 |

0.06 |

0.23 |

0.86 |

||||

|

Daytime card |

0.04 |

0.19 |

0.06 |

0.23 |

0.05 |

||||

|

Date of purchasing contract

|

23 sep 2016 |

38 |

01 ju l2016 |

01 dec 2016 |

23 sep 2016 |

39 |

01 jul 2016 |

01 dec 2016 |

0.66 |

|

Weekly (pre-experiment) attendance:

|

|||||||||

|

Gym visits |

0.98 |

1 |

0 |

7 |

0.88 |

0.96 |

0 |

5.8 |

0.02 |

|

Free training |

0.77 |

0.97 |

0 |

6.8 |

0.69 |

0.89 |

0 |

5.8 |

0.03 |

|

Class training |

0.21 |

0.49 |

0 |

3.4 |

0.19 |

0.46 |

0 |

3.4 |

0.43 |

|

Observations |

1232 |

1231 |

|||||||

![]() A ‘Recurring member’ is someone who had an active contract at some point during the six months prior to our sample inflow period (January 1, 2016 –June 30, 2016).

A ‘Recurring member’ is someone who had an active contract at some point during the six months prior to our sample inflow period (January 1, 2016 –June 30, 2016).

![]() A CrossFit membership is similar to a ‘Multi card’ membership but also allows entry to CrossFit.

A CrossFit membership is similar to a ‘Multi card’ membership but also allows entry to CrossFit.

![]() For the distribution of the dates of contract purchases in the control and treatment groups, see Fig. 2 in the Online Appendix.

For the distribution of the dates of contract purchases in the control and treatment groups, see Fig. 2 in the Online Appendix.

![]() Attendance statistics are computed over the period from December 2, 2016 to January 8, 2017 (this is the pre-experiment period for which we have attendance data for all individuals)

Attendance statistics are computed over the period from December 2, 2016 to January 8, 2017 (this is the pre-experiment period for which we have attendance data for all individuals)

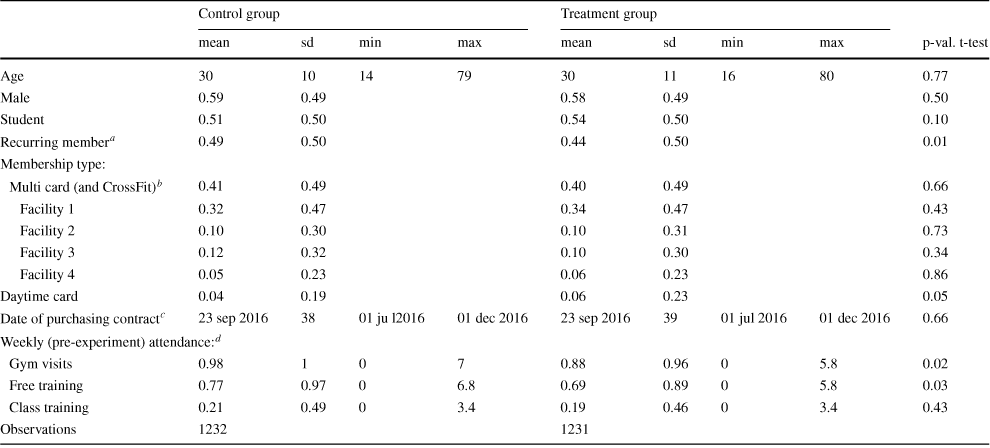

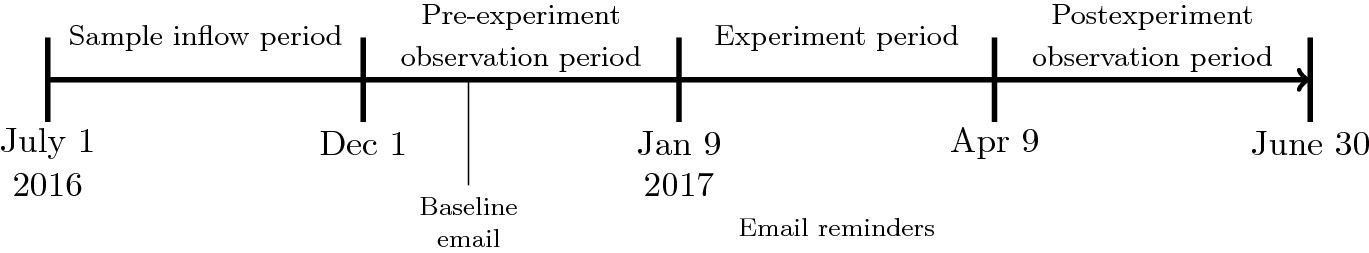

We randomly assigned these individuals into treatment and control groups in the first week of December 2016. The experiment, which we describe in detail below, began on January 9, 2017 (see Fig. 2 for a timeline of our setup). We present descriptive statistics in Table 1, which contains the mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum for the control group (columns 1–4) and for the treatment group (columns 5–8) and the p-value of a t-test for equal means (column 9). The top panel presents individual characteristics, the second panel membership and contract details. The average age is 30, a share of 58% of the gym members are males, 52% registered as students and 46% had been members of this gym previously. A total of 40% bought a Multi card, and 5% bought a membership that is valid only during daytime hours (a ‘daytime card’). The mean date of purchasing the contract is September 23 for both groups (see Fig. 2 in the Online Appendix for the full distributions of contract buying dates). Most variables do not differ significantly between control and treatment groups, with the exception of a slightly lower share of recurring members and a slightly higher share of members who bought a daytime card in the treatment group.

The five-week period of pre-experiment gym visit observations (December 2, 2016–January 8, 2017) allows us to compare the control and treatment groups in terms of attendance. In the lower panel of Table 1, we find that the treatment group has a significantly lower number of weekly visits in the pre-experiment period, and this difference is caused by a lower number of free training visits. In Sect. 3.1, we discuss that we control for these differences by including individual fixed effects when estimating the impact of the reminders. Note that the number of weekly visits is lower in this pre-experiment period than is typically the case because this time period includes the Christmas holidays, during which gym attendance is low. In Fig. 3 in the Online Appendix, we compare the distributions of gym visits of the control and treatment groups across facilities, class types and weekly number of visits and find that the groups are similar.

Fig. 2 Timeline of the experiment

2.3 Experiment details

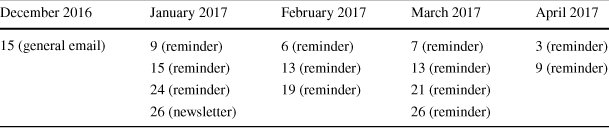

The intervention consisted of a series of email reminders that were dispatched to the treatment group between January 9, 2017, and April 9, 2017 (see Table 7 in “Appendix” for the dates).Footnote 10

The reminders were sent from the gym’s email account once per week, and they contained a short message (typically no longer than three sentences) encouraging the recipient to attend the gym. In addition, they contained a picture related to the gym and a link to the club’s website (for an example, see Fig. 4 in the Online Appendix). Header, text and picture differed every week in order to attract the recipients’ interest and make them more likely to open and read the reminders. Most emails referred to the various exercise options available at the club or reminded the reader about the potential benefits of attending the gym.Footnote 11 An example of a reminder is the following: “Did you know that we offer more than 200 classes per week? Drop in any time to work out, or sign up for a class on www.fysiken.nu/en/book/. We hope to see you soon!” The complete list of reminders can be found in “Appendix”.Footnote 12

Each reminder email contained a line at the bottom explaining that the readers had received this email because of their gym membership and that they could unsubscribe by clicking on a link. When members unsubscribed, they were removed from our email list and did not receive any further email communication related to the study.

Receiving emails from the gym is not unusual for members. The gym has a policy of sending out an automated welcome email when a new member signs up. Furthermore, automated emails are sent when a new member has not attended the gym for 90 days (though these emails were suspended during our experiment). A few times per year, all members receive a newsletter (unless they have unsubscribed from this service). Both the control and the treatment groups received such a newsletter once during the experiment. The starting date and the end date of the email reminders were unknown to participants. Finally, the days on which the reminders were dispatched were randomized between Sundays, Mondays and Tuesdays in order to make sure that members in the treatment group did not expect to receive a reminder on a particular weekday.

The effectiveness of email reminders obviously depends on whether the recipient receives (and notices) the reminders. An email might not be received because, for example, members have misspelled their email address or registered an address that they fail to use, or the emails have ended up in their spam folders. Even if the email appears in the user’s inbox, it may be deleted without being opened (although in that case, its impact could already have been achieved if it brought the gym to the top of the receiver’s mind). Since email reading behavior is likely to depend on individual characteristics, selecting a sample of recipients who have responded to an email, as in Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017), may imply that the sample is also more responsive to subsequent email reminders than the average gym population.

To what degree emails are received is difficult to assess, because whether someone opens and reads a particular email is not typically observed. We address this issue in two ways. First, we observe a proxy for whether each email has been opened using so-called ‘web beacons’, which record whether the picture included in the email has been downloaded. This measure of email opening is not perfect because not every email client downloads the picture by default. An email can thus be read without downloading the picture, implying that our obtained measure provides a lower bound for the opening rate.

Second, we sent out a ‘baseline email’ to our entire sample about five weeks prior to the start of the study. In this email, we briefly described the widely known challenge of achieving one’s exercising goals and asked the recipients whether they believed that regular email reminders could help them improve in this regard. If they thought that regular reminders could indeed be helpful, they were asked to click on a button in the email.Footnote 13 The baseline email provides a measure of which members—in both the control and treatment groups—open emails. In addition, when someone clicked on the button, we know with certainty that the email was read. We will make use of the web beacons and the baseline email in the empirical analysis to identify a subgroup of individuals who are likely to open and read emails so that we can estimate heterogeneous effects for this group (see Sect. 3.3).

2.4 Opening of emails and unsubscribing

Before we analyze the impact of our reminders, we show some statistics on the email opening rate for our reminders and on members’ unsubscription from our email list.

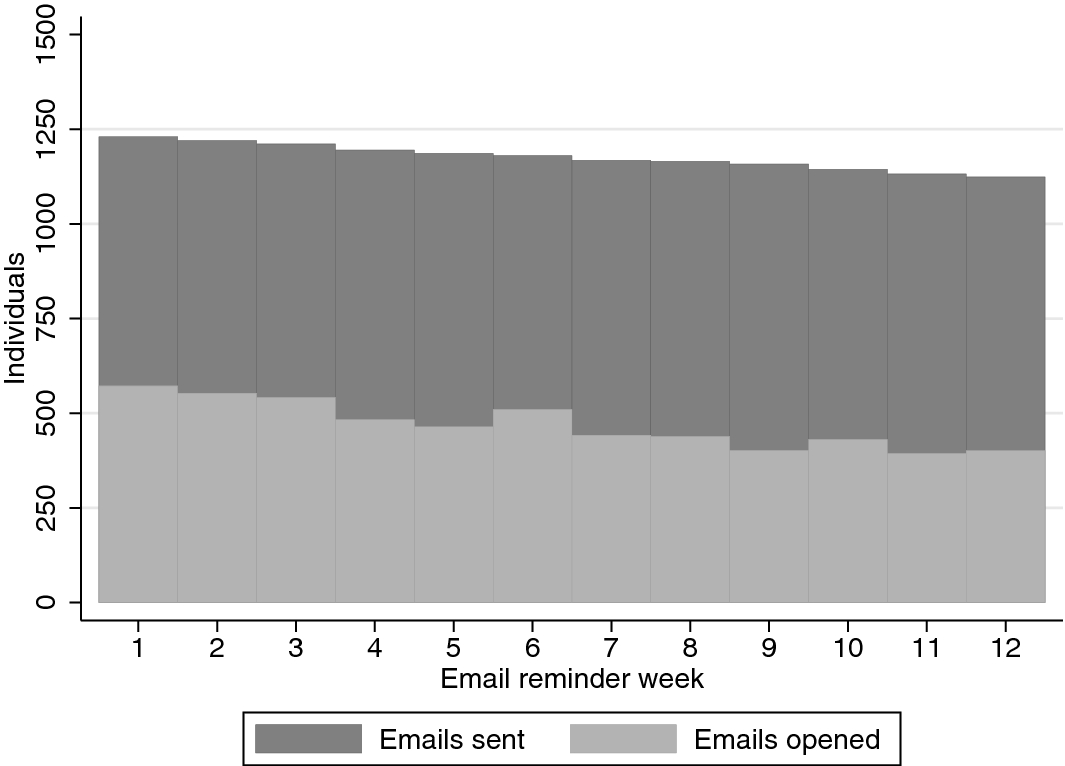

Fig. 3 Number of emails sent and opened

Weekly unsubscribing is measured after each reminder email. It is important to note that unsubscription is not equivalent to attrition in our study. We observe gym attendance (or nonattendance) for all individuals in the study. Unsubscription merely implies that fewer emails are received. In Fig. 3, we present the weekly number of emails that were dispatched. While the number of email addresses on our list declined steadily, 91% of all individuals in the treatment group remained on the mailing list at the end of the intervention. Thus, weekly unsubscription is approximately 1%. In the same figure, we show the number of delivered emails that we know with certainty were opened, i.e., those for which the picture was downloaded. Considering that this percentage is a conservative estimate, the opening rate is quite substantial: 46% in the first week, decreasing to 36% in the final week.

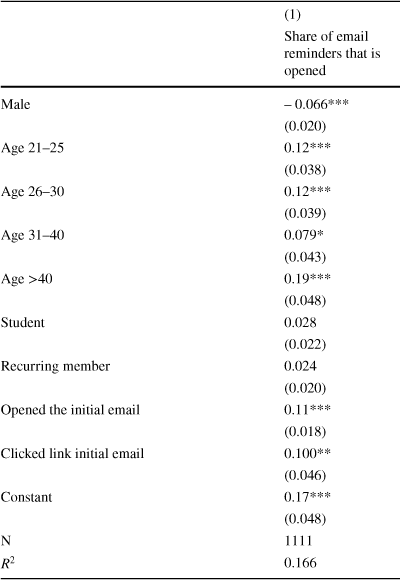

Table 2 Regression of the email opening rate on individual characteristics

|

(1) |

|

|---|---|

|

Share of email reminders that is opened |

|

|

Male |

– 0.066*** |

|

(0.020) |

|

|

Age 21–25 |

0.12*** |

|

(0.038) |

|

|

Age 26–30 |

0.12*** |

|

(0.039) |

|

|

Age 31–40 |

0.079* |

|

(0.043) |

|

|

Age >40 |

0.19*** |

|

(0.048) |

|

|

Student |

0.028 |

|

(0.022) |

|

|

Recurring member |

0.024 |

|

(0.020) |

|

|

Opened the initial email |

0.11*** |

|

(0.018) |

|

|

Clicked link initial email |

0.100** |

|

(0.046) |

|

|

Constant |

0.17*** |

|

(0.048) |

|

|

N |

1111 |

|

|

0.166 |

*p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01. Standard errors clustered by individual in parentheses. In addition to the variables above, six email client dummies are included in the regression. The sample contains only the treatment group and excludes 120 individuals for which the sex variable is missing

To assess whether certain types of individuals are more likely to open the email, we regress the share of reminders that are opened on individual characteristics. The results are shown in Table 2 (clearly only the treatment group is included). We find that men are significantly less likely to open emails (– 7%-points). The same holds for gym members aged below 20 years (with the difference between this group and most other age groups being more than 10%-points). We find no differences for students or recurring members. Furthermore, we find that responding to the baseline email is, unsurprisingly, a good predictor of opening the reminder emails. Opening the baseline email is associated with an 11%-points increase in the share of reminders that are opened during the study. Clicking on the link in the baseline email adds another 10%-points increase.

3 Experimental results

In this section, we discuss the effect of our intervention on gym attendance during and after the intervention. We also consider the effect on class bookings and the cancellation of bookings, as well as heterogeneous effects and individuals’ contract renewal decisions.

3.1 Impact on gym attendance

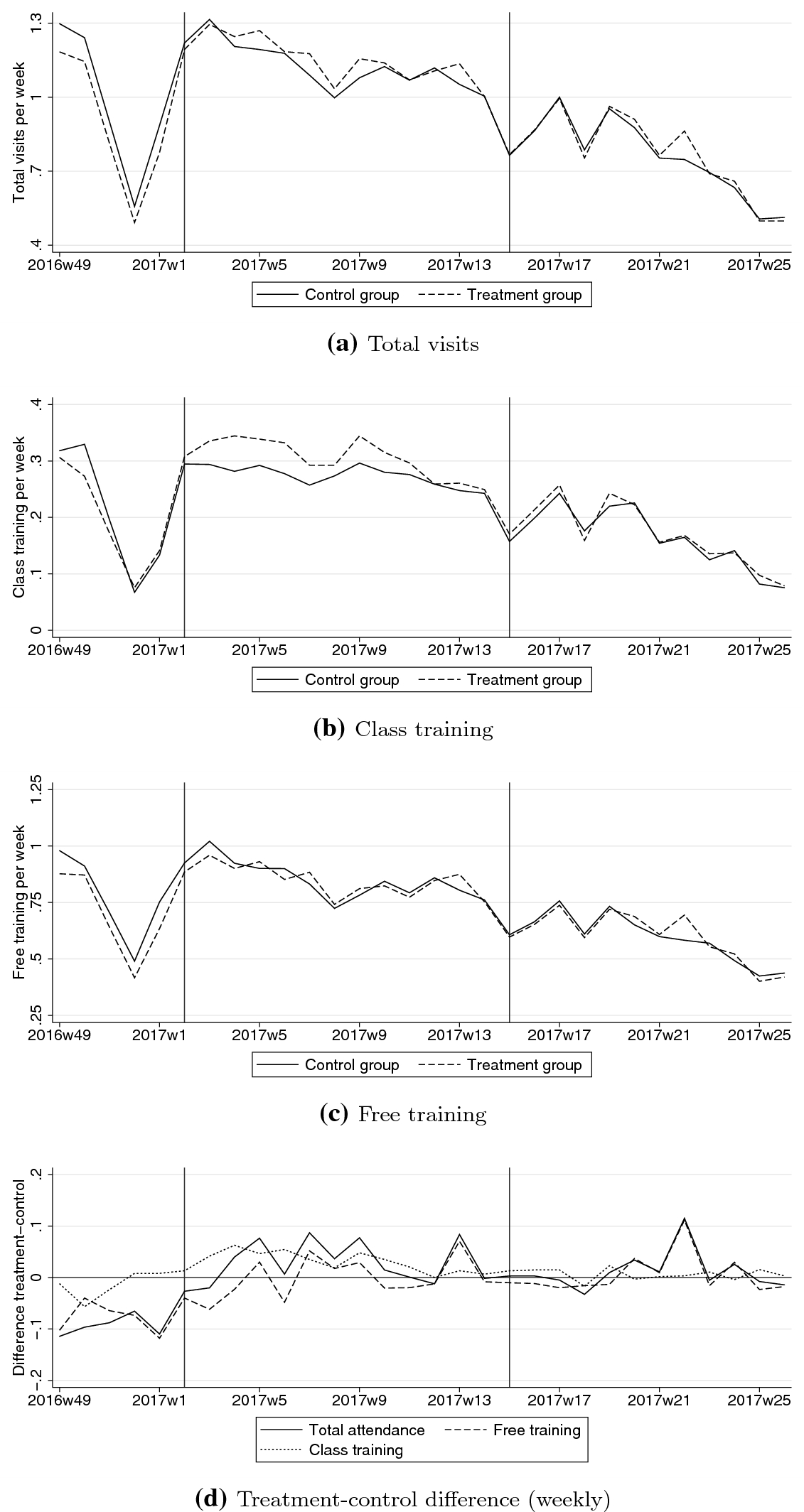

Fig. 4 Weekly gym attendance

We show the average weekly number of gym visits in the control and treatment groups in panel (a) of Fig. 4. On average, individuals visit the gym around once per week (with the exception of a large dip around the Christmas break). The time trend is negative and can have two possible explanations. First, our sample contains members with new contracts, and attendance typically declines over the course of the membership (e.g., DellaVigna and Malmendier Reference DellaVigna and Malmendier2006; Garon et al. Reference Garon, Masse and Michaud2015). Second, higher temperatures and longer hours of sunshine might drive gym members from indoor to outdoor activities in spring and summer.Footnote 14

The first vertical line in Fig. 4 indicates the start of the experiment period in which the email reminders were sent. As mentioned earlier, the control group has a slightly higher gym attendance than the treatment group in the weeks before the experiment begins (but the trends look extremely similar). Almost directly after the reminders begin, this pattern reverses, and the treatment group has a slightly higher attendance than the control group, see panel (a). In panel (b), we find that the impact of the reminders on class training is particularly pronounced. Class attendance is higher for the treatment group in all experiment period weeks, while the two groups have almost identical pre-experiment class attendance. In panel (c), we show the average number of free training sessions per week. Finally, in panel (d), the difference between the treatment and control groups for each of the three variables is depicted. The diagram clearly shows that the lower attendance of the treatment group in the pre-experiment period reverses to higher attendance after the email reminders begin.

The second vertical line indicates the end of the intervention, after which no further reminders are sent. We observe attendance until June 30. After that, the vacation period begins, during which gym attendance is traditionally very low and the number of offered classes is greatly reduced. Furthermore, extending the postexperiment period beyond this day would imply that we would lose participants in our sample since some of them will not prolong their contracts. The negative trend in weekly attendance clearly continues after the experiment ends. The difference between the control and treatment groups is smaller than it is during the experiment but still suggests a slightly higher average attendance for the treatment group (especially when taking the pre-experiment difference into account). As shown in panel (d), for each of the three lines, the difference is either (slightly) positive or close to zero during the postexperiment period.Footnote 15

To obtain estimates of the impact of the reminders, we compute the average weekly attendance in the pre-experiment and experiment period for the control and treatment groups.Footnote 16 The simple DiD estimate for the total number of gym visits is 0.12 additional visits per week as a result of the email reminders, which is equivalent to an 11% increase. The additional visits consist of 0.045 additional classes (17% increase) and 0.083 additional free training sessions (10% increase). Over the 12 weeks of the experiment, this effect aggregates into 1.5 extra visits on average for each individual who received the reminders. Given that marginal costs of the intervention are close to zero, this shift can be considered a substantial effect.

We now turn to a regression framework and estimate a DiD model. The impact of the reminders is identified from the assumption that in the absence of the intervention, the control and treatment groups would have had the same time trend in weekly gym attendance. Weekly gym attendance (

![]() ) of individual i in week t depends on week fixed effects

) of individual i in week t depends on week fixed effects

![]() , individual fixed effects

, individual fixed effects

![]() and treatment assignment

and treatment assignment

![]() , which is a dummy equal to 1 if individual i is in the treatment group and week t is in the experiment period. Furthermore, we control for membership duration in a flexible way by including a set of dummies for different membership duration intervals (

, which is a dummy equal to 1 if individual i is in the treatment group and week t is in the experiment period. Furthermore, we control for membership duration in a flexible way by including a set of dummies for different membership duration intervals (

![]() ).Footnote 17 The error term is

).Footnote 17 The error term is

![]() .

.

The parameters of interest are

![]() and

and

![]() , which measure the immediate and posttreatment effects of the reminders, respectively. From panels (c) and (d) of Fig. 3 in the Online Appendix, it is clear that weekly gym attendance is a count variable with many zeros. Thus, a Poisson regression is more suitable than a linear regression. We report the results for a linear model as a robustness check (see Sect. 3.2) and find that the results are very similar.Footnote 18 Standard errors are clustered by individual.

, which measure the immediate and posttreatment effects of the reminders, respectively. From panels (c) and (d) of Fig. 3 in the Online Appendix, it is clear that weekly gym attendance is a count variable with many zeros. Thus, a Poisson regression is more suitable than a linear regression. We report the results for a linear model as a robustness check (see Sect. 3.2) and find that the results are very similar.Footnote 18 Standard errors are clustered by individual.

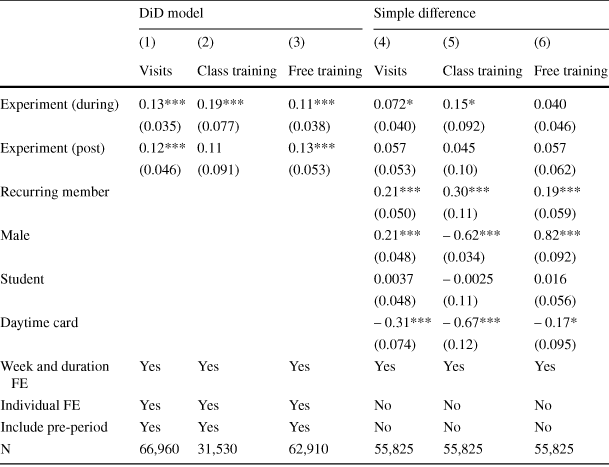

The regression results are presented in Table 3, where we report

![]() , which is the percentage effect. We first discuss the immediate impact of the reminders (

, which is the percentage effect. We first discuss the immediate impact of the reminders (

![]() ), which is shown in the first row. We find that total visits increase by 13%, which is significant at the 1% level (column 1). We split these visits into class training and free training in columns (2) and (3) and find that attendance in class exercise training increases by 19%, while free training visits increase by 11%. Although the percentage effect for class training visits is larger than for free training, their much lower base level implies that the impact in terms of additional visits is actually greater for free training (and in fact the difference between the two estimates is not statistically significant).Footnote 19,

Footnote 20

), which is shown in the first row. We find that total visits increase by 13%, which is significant at the 1% level (column 1). We split these visits into class training and free training in columns (2) and (3) and find that attendance in class exercise training increases by 19%, while free training visits increase by 11%. Although the percentage effect for class training visits is larger than for free training, their much lower base level implies that the impact in terms of additional visits is actually greater for free training (and in fact the difference between the two estimates is not statistically significant).Footnote 19,

Footnote 20

Table 3 Regressions on weekly gym attendance (Poisson models)

|

DiD model |

Simple difference |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

|

|

Visits |

Class training |

Free training |

Visits |

Class training |

Free training |

|

|

Experiment (during) |

0.13*** |

0.19*** |

0.11*** |

0.072* |

0.15* |

0.040 |

|

(0.035) |

(0.077) |

(0.038) |

(0.040) |

(0.092) |

(0.046) |

|

|

Experiment (post) |

0.12*** |

0.11 |

0.13*** |

0.057 |

0.045 |

0.057 |

|

(0.046) |

(0.091) |

(0.053) |

(0.053) |

(0.10) |

(0.062) |

|

|

Recurring member |

0.21*** |

0.30*** |

0.19*** |

|||

|

(0.050) |

(0.11) |

(0.059) |

||||

|

Male |

0.21*** |

– 0.62*** |

0.82*** |

|||

|

(0.048) |

(0.034) |

(0.092) |

||||

|

Student |

0.0037 |

– 0.0025 |

0.016 |

|||

|

(0.048) |

(0.11) |

(0.056) |

||||

|

Daytime card |

– 0.31*** |

– 0.67*** |

– 0.17* |

|||

|

(0.074) |

(0.12) |

(0.095) |

||||

|

Week and duration FE |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Individual FE |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

Include pre-period |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

|

N |

66,960 |

31,530 |

62,910 |

55,825 |

55,825 |

55,825 |

Standard errors clustered by individual in parentheses. We report

![]() , which is the percentage effect. Seven age dummies and six gym location dummies are included but not reported in columns (4–6). Note that the number of observations in columns (1–3) varies because individuals with zero attendance in all time periods drop out in Poisson regressions with fixed effects (FE)

, which is the percentage effect. Seven age dummies and six gym location dummies are included but not reported in columns (4–6). Note that the number of observations in columns (1–3) varies because individuals with zero attendance in all time periods drop out in Poisson regressions with fixed effects (FE)

*p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

As a robustness check, we also present regressions in which we exclude the pre-experiment period and thus do not include individual fixed effects (columns 4–6 in Table 3). Instead, we include a number of time-invariant individual covariates (a sex dummy, a student dummy, seven age category dummies and a dummy for being a recurring member of the gym).Footnote 21 The results are similarly positive, although somewhat smaller in magnitude. Combined with somewhat larger standard errors, only the effect on the total number of visits is statistically significant. This finding was expected, as the slightly lower attendance level of the treatment group in the pre-experiment period is ignored in these regressions. Note that while the control and treatment groups are balanced with respect to most observed characteristics (see Table 1), the share of recurring members is 5%-points higher in the control group. Recurring members typically exercise more frequently, which may explain the slightly higher pre-experiment number of visits within the control group. Thus, we prefer the DiD model that corrects for these (and potentially other) differences.

So far, we have looked at the immediate effect of email reminders on gym attendance. One might expect that once the reminders cease, treated individuals will stop attending the gym at an increased frequency. Persistent effects of a short-term intervention might, however, be explained by habit formation. Habits are acquired when ‘repetition of a behavior in a consistent context progressively increases the automaticity with which the behavior is performed when the situation is encountered’ (Lally et al. Reference Lally, van Jaarsveld, Potts and Wardle2010, p. 998). In our context, the higher frequency of attending the gym might make it easier to attend even when the reminders have ended. Only weak or no evidence of habituation has been found by studies in the field of health behavior (see, e.g., Charness and Gneezy Reference Charness and Gneezy2009; Acland and Levy Reference Acland and Levy2015; Calzolari and Nardotto Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017; Carrera et al. Reference Carrera, Royer, Stehr and Sydnor2018a, Reference Carrera, Royer, Stehr and Sydnor2020), although this might be due partly to a lack of statistical power.

We present estimates of the impact of the reminders during the postexperiment period (

![]() ) in the second row of Table 3. We find the surprising result that the postexperiment impact on total visits is—in relative terms—of a similar magnitude as the immediate impact (a 12% increase). The same result holds for the impact on free training visits (column 3). The coefficient for class training in column (2) is slightly smaller, which, combined with less precision due to a lower base rate of attendance of class trainings, leads to the impact not being statistically significant. However, the magnitude of the class training coefficient is very similar to that of the free training coefficient. In contrast to Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017), our postexperiment effects have the same size as the effects during the experiment period, at least in relative terms, and are statistically significant for the whole sample.Footnote 22

) in the second row of Table 3. We find the surprising result that the postexperiment impact on total visits is—in relative terms—of a similar magnitude as the immediate impact (a 12% increase). The same result holds for the impact on free training visits (column 3). The coefficient for class training in column (2) is slightly smaller, which, combined with less precision due to a lower base rate of attendance of class trainings, leads to the impact not being statistically significant. However, the magnitude of the class training coefficient is very similar to that of the free training coefficient. In contrast to Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017), our postexperiment effects have the same size as the effects during the experiment period, at least in relative terms, and are statistically significant for the whole sample.Footnote 22

While these postexperiment results are perhaps larger than expected, it should be stressed that they are less robust, and, in absolute terms, somewhat smaller than the during-experiment effects. First of all, standard errors are larger, indicating less precision. Second, the baseline level of attendance of our sample decreases over time. In particular, this level is lower in the postexperiment period than during the experiment. Since our Poisson model estimates percentage effects, an equal coefficient implies a smaller number of additional visits in the postexperiment period. Third, there is a large outlier in terms of attendance in the treatment group in week 22 (see Fig. 4). The gym sent out a newsletter email to all members in this week, and it appears as if this had more influence on our treatment group than on the control group. This particular week drives some of the positive posttreatment difference. In “the Online Appendix”, we show that the postexperiment effect is smaller than the during-experiment effect if we use a linear model and exclude the outlier in week 22 (see Table 2).Footnote 23

To conclude, we find clear evidence of a persistent positive effect of reminders on attendance. Interestingly, the effect of the reminders remains substantial after the reminders have ended. We interpret this finding as a sign of habit formation.

3.2 Robustness checks

We perform a series of robustness checks to investigate whether our results are sensitive to choices in the empirical model. First, we estimate the baseline models with simple OLS to assess the sensitivity of the results to the Poisson model. The results are presented in Table 1 in “the Online Appendix”. The statistically significant increase of 0.12 weekly visits translates into a 13% increase, which is very similar to the Poisson regression estimate (13%). The same holds for the effects on class training and free training.

Second, we perform robustness checks with respect to the last two weeks of 2016 (weeks 51 and 52) and the first week of 2017 (week 1), in which gym attendance was substantially below its long-run level (see Fig. 4). Since these weeks are part of the pre-experiment period, they may affect the DiD estimates. In Table 5 in “the Online Appendix”, we exclude either week 52 or weeks 51, 52 and 1 from the analysis. Note that the total pre-experiment period consists of weeks 49, 50, 51, 52 and 1, and thus, we can estimate the DiD model even when excluding the Christmas holidays. We find that excluding either one or three weeks hardly affects our results.

Third, we consider the length of the pre-experiment period. In all DiD estimations, the pre-experiment period consists of five weeks. This period is restricted by the fact that our sample consists of gym members who purchased their contracts between July 1, 2016, and December 1, 2016. As a robustness check, we select a subsample of individuals who purchased their contracts earlier (July 1–October 1) and extend the pre-experiment period accordingly. The results are presented in “the Online Appendix” in Table 6. The DiD estimates for all visits are still positive but smaller in magnitude, which, combined with somewhat larger standard errors, makes them no longer significant. The effect on class training is still large and significant.

Fourth, we consider using daily data on gym visits instead of aggregated weekly data (see Fig. 6 in the Online Appendix). We use a linear specification that is similar to the one used for weekly visits, but we include additional day-of-the-week fixed effects. The results are presented in Table 7 in the Online Appendix. We find that the impact of reminders is very similar to our baseline model in terms of magnitude and statistical significance.

We conclude that the positive effect of reminders on gym attendance is robust against several alternative specifications.

3.3 Heterogeneous effects

The impact of email reminders may vary, depending on an individual’s characteristics. Given our large sample size, we can investigate different sources of heterogeneous effects, and we focus on sex, baseline gym attendance, previous gym membership (at the same gym), student status and a pre-experiment measure of the likelihood of opening emails. We estimate the same model for each particular subsample.Footnote 24 Identification follows from a similar standard DiD assumption as before. We report results only for the total number of weekly gym visits (rather than distinguishing between classes and free training).

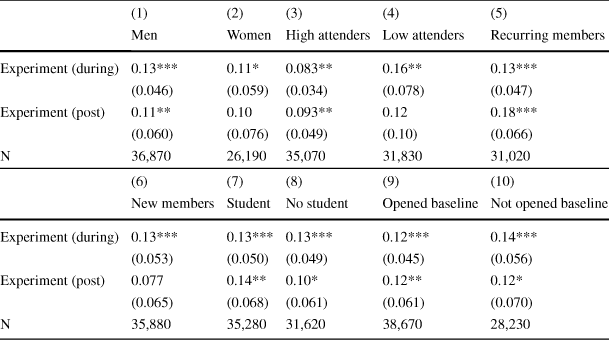

We first consider heterogeneous effects by sex. While men and women have similar average numbers of weekly visits (1.16 for men and 1.00 for women), they exercise in different ways. One-third of gym visits by women are class trainings, while the corresponding number is less than 10% for men. In Table 4, we present estimation results for men in column (1) and for women in column (2). We find that the estimates are very similar, and we conclude that reminders are equally effective for both sexes.

Table 4 DiD regressions on weekly gym attendance (Poisson models): heterogeneous effects

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Men |

Women |

High attenders |

Low attenders |

Recurring members |

|

|

Experiment (during) |

0.13*** |

0.11* |

0.083** |

0.16** |

0.13*** |

|

(0.046) |

(0.059) |

(0.034) |

(0.078) |

(0.047) |

|

|

Experiment (post) |

0.11** |

0.10 |

0.093** |

0.12 |

0.18*** |

|

(0.060) |

(0.076) |

(0.049) |

(0.10) |

(0.066) |

|

|

N |

36,870 |

26,190 |

35,070 |

31,830 |

31,020 |

|

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

New members |

Student |

No student |

Opened baseline |

Not opened baseline |

|

|

Experiment (during) |

0.13*** |

0.13*** |

0.13*** |

0.12*** |

0.14*** |

|

(0.053) |

(0.050) |

(0.049) |

(0.045) |

(0.056) |

|

|

Experiment (post) |

0.077 |

0.14** |

0.10* |

0.12** |

0.12* |

|

(0.065) |

(0.068) |

(0.061) |

(0.061) |

(0.070) |

|

|

N |

35,880 |

35,280 |

31,620 |

38,670 |

28,230 |

Standard errors clustered by individual in parentheses. We report

![]() , which is the percentage effect. All regressions include individual fixed effects and membership duration dummies

, which is the percentage effect. All regressions include individual fixed effects and membership duration dummies

*p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

Second, we consider heterogeneous effects by baseline gym attendance. We split the sample at the median weekly attendance in the pre-experiment period, which is 0.6 visits per week. The estimation results are presented in column (3) for high attenders and column (4) for low attenders and suggest a greater impact on members who attended less frequently than the median. This finding is in line with the results by Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017) and is not surprising since for high attenders, there is a lower scope to increase the amount of exercising beyond the current level (e.g., due to time constraints). Note, however, that a formal test cannot reject equal coefficients for high and low attenders.

Third, we test whether recurring members are more or less affected by the reminders. Since recurring members extended their previous contract, they are likely to be more committed to exercising, and thus, we expect them to benefit less from email reminders. We do not find evidence supporting this hypothesis, with the coefficients for the two groups being almost identical (columns 5 and 6). This finding suggests that the group of recurring members is perhaps less selective than one might expect.Footnote 25

Fourth, we consider student status. As shown in Table 1, approximately half of our sample consists of students.Footnote 26 While we have no strong hypothesis for differing impacts of the reminders for students and nonstudents (except for maybe differently binding time constraints), we still believe it is important with respect to external validity. For example, previous findings on the effectiveness of reminders by Calzolari and Nardotto (Reference Calzolari and Nardotto2017) were based only on a student population, and thus, we are interested in whether the impact extends to a more general population. The results are presented in columns (7) and (8), and we find that the estimates are virtually identical for students and nonstudents. Thus, the positive effect is present even for a population that is more likely to be (full-time) employed and that has (perhaps) more stringent time restrictions for exercising.

Finally, we consider heterogeneous effects according to whether one opens the baseline email (1405 out of the 2463 individuals in the sample opened this email; see Sect. 2.3). Ideally, one would measure whether those who actually opened the reminders were more likely to visit the gym. However, since those members are a selective subset of the treatment group and because we do not observe opening rates for the control group, we have no valid control for those who opened the reminders. Thus, we use opening the baseline email as a proxy for opening gym emails in general. The results for those who opened the email are presented in column (9) and for those who did not open the email in column (10). We find the rather surprising result that there is no significant difference between the two groups. The coefficient for those who did not open the baseline email is even slightly larger than the coefficient for those who opened the email.Footnote 27 Thus, even for those who are (relatively) less likely to open and/or read emails, we find a significantly positive effect. While somewhat puzzling, this finding can have various explanations.

First, it might be that seeing the email appear in one’s inbox is sufficient to bring the gym to one’s attention and thus overcome limited attention (without actually opening the message). Second, the statistics on downloading web beacons may severely underestimate the actual reading rate: some recipients read the email without downloading the image. It is possible that this kind of measurement error is to some extent correlated with whether individuals open the email, resulting in less reliable estimates. Third, we cannot rule out the possibility that individuals that generally open fewer emails also differ in other personality traits. For example, individuals who are less organized in their daily lives might be more prone to not read emails and, simultaneously, more likely to forget about attending the gym. As a result, the reminders that they do open are particularly effective in nudging them to attend the gym.

In summary, we do not find strong evidence for heterogeneous effects of email reminders, except for some suggestive evidence that low attenders are more affected than high attenders (but the difference is not statistically significant). These findings suggest that nearly all groups benefit from reminders in terms of overcoming their limited attention, which strengthens the case for reminder policies.

3.4 Booking and canceling

In the previous sections, we established that gym members who received email reminders attended gym classes more frequently both during the treatment period and in the three months after the reminders had ended. In this section, we shed light on whether reminders lead only to an almost immediate response of visiting the gym or whether they also stimulate the recipient to plan a future visit by booking a gym class.Footnote 28 Before we proceed with the empirical analysis, we briefly describe the features of the booking and cancellation system and provide some descriptive statistics on booking and canceling behavior.

The classes offered at the gym have a maximum capacity. Members can book a spot in a class online or through a mobile app up to seven days prior to the class. After a booking, the gym does not send any reminders for the booked class. Once all spots are booked, new bookings are placed on a waiting list and result in a spot when earlier bookings are canceled. A booking can be canceled online or through the mobile app up to one hour prior to the class. In the last 60 minutes before the class, members without a booking can claim a spot with the gym’s reception staff if a spot is still available (we refer to this as ‘drop-in attendance’). Finally, those with a prior booking must show up at least 10 minutes prior to the class; otherwise, the booking is canceled and the spot becomes available for drop-in attendance. If a booking is not canceled in time and the individual does not show up, his or her card is blocked from further bookings until a fine of SEK25 (approximately $3) is paid. We refer to these cases as ‘no-shows’.Footnote 29 It is not uncommon for all spots in a class to be taken, often several days in advance. For example, of all 9513 classes for which we have data, 30.7% had a waiting list (at some point). This does not mean that all spots were eventually taken for one-third of the classes because canceling is also very common. However, it does illustrate that booking classes beforehand is often necessary and very common.

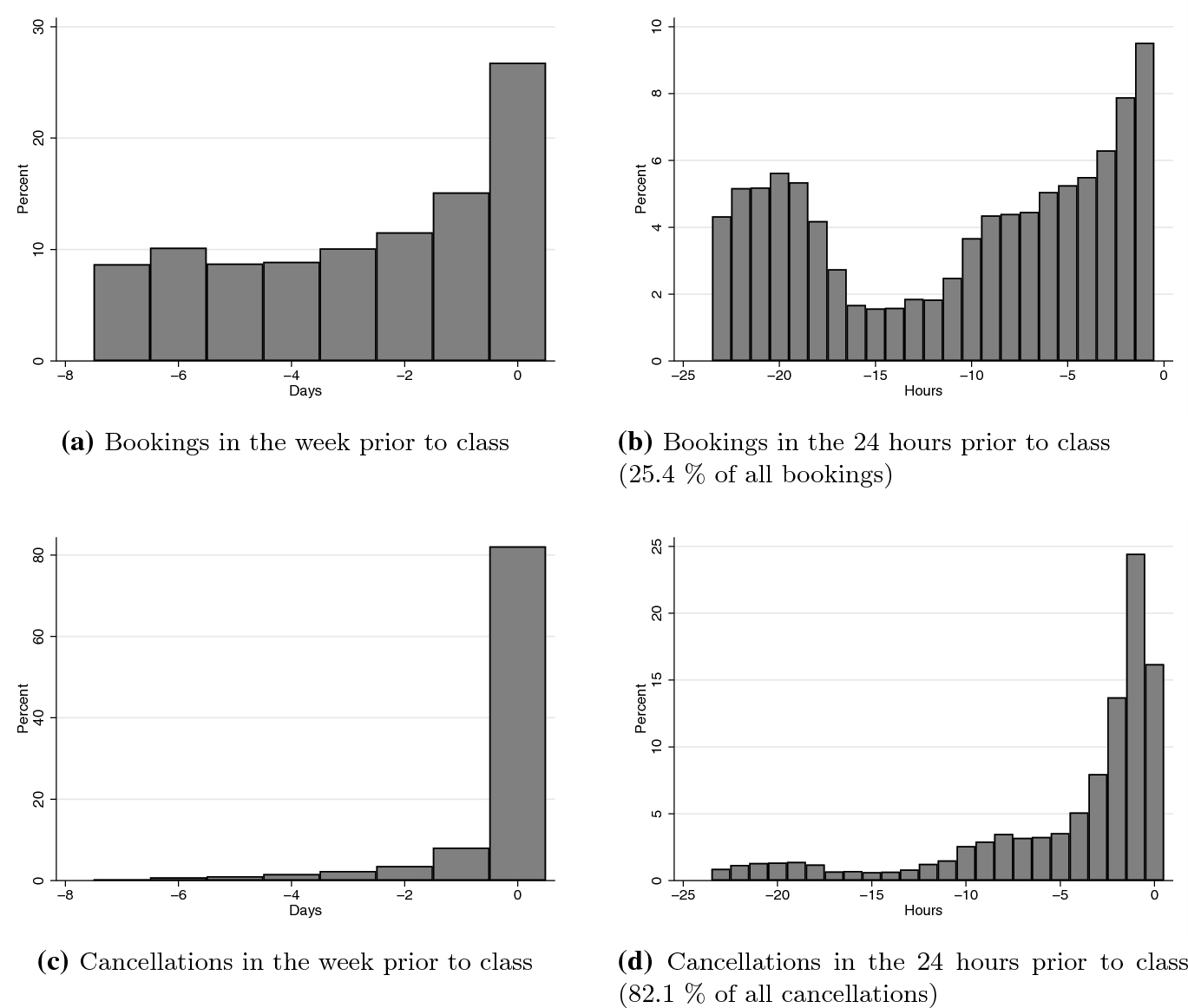

Fig. 5 Distribution of bookings and cancellations

Our dataset contains observations for class bookings, cancellations and no-shows of the experimental sample for the period from July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017. In total, we observe 43,953 bookings and 6114 drop-in attendances. In the upper panel of Fig. 5, we show the distribution of class bookings. In panel (a), we find that the number of daily bookings is approximately uniform across the first six days prior to a class (roughly 10% per day). Around 15% of all bookings are made on the day before a class and another 28% on the day of the class (‘day zero’). Most of the bookings on day zero are made in the very last hours before the class (panel b).Footnote 30 Furthermore, most gym class visits are booked prior to the class (79%) and are not made through drop-in (see also Table 8 in the Online Appendix). In the lower panel of Fig. 5, we show how cancellations are distributed across days prior to the class (no-shows are included in the figure as canceling zero minutes prior to the class). We observe that a significant share of bookings are canceled (42%) and that the vast majority (82%) of all cancellations occur on the day of the class (panel c), 61% of all cancellations even within the final six hours (panel d). Furthermore, slightly more than 5% of all bookings or, equivalently, 13% of all cancellations are no-shows, i.e., never followed up on. As the cancellation costs seem rather low as compared to the costs of not showing up to a booked class (around $3), we take no-shows as evidence for limited attention.

There is substantial variation in the popularity of the classes. In the Online Appendix, we show that a majority of those who attend unpopular classes (which never have a waiting list), still make an early booking. This even holds for experienced attenders of these unpopular classes. We take this finding as evidence that many individuals value bookings as a commitment device to overcome time-inconsistent preferences, i.e., present bias: through making a booking, they reduce their likelihood not to attend the class. See the Online Appendix for further details and discussion.

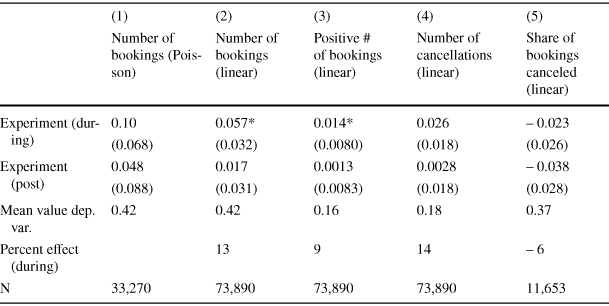

Table 5 Regressions on weekly class bookings and cancellations of bookings

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of bookings (Poisson) |

Number of bookings (linear) |

Positive # of bookings (linear) |

Number of cancellations (linear) |

Share of bookings canceled (linear) |

|

|

Experiment (during) |

0.10 |

0.057* |

0.014* |

0.026 |

– 0.023 |

|

(0.068) |

(0.032) |

(0.0080) |

(0.018) |

(0.026) |

|

|

Experiment (post) |

0.048 |

0.017 |

0.0013 |

0.0028 |

– 0.038 |

|

(0.088) |

(0.031) |

(0.0083) |

(0.018) |

(0.028) |

|

|

Mean value dep. var. |

0.42 |

0.42 |

0.16 |

0.18 |

0.37 |

|

Percent effect (during) |

13 |

9 |

14 |

– 6 |

|

|

N |

33,270 |

73,890 |

73,890 |

73,890 |

11,653 |

Standard errors clustered by individual in parentheses. In column (1), we report

![]() , which is the percentage effect. Note that the number of observations is lower in column (1) because individuals with zero bookings in all time periods drop out in Poisson regressions with fixed effects. In column (3), the outcome is an indicator variable equal to 1 in the case of a positive number of bookings

, which is the percentage effect. Note that the number of observations is lower in column (1) because individuals with zero bookings in all time periods drop out in Poisson regressions with fixed effects. In column (3), the outcome is an indicator variable equal to 1 in the case of a positive number of bookings

*p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01

We now proceed with estimating the impact of the reminders on booking and canceling. Limited attention potentially affects bookings and cancellations and thus class participation. First, members may forget to make a booking. Second, given that they have made a booking, they may forget about the booked class. Third, they may not have forgotten about the booked class but they may forget to cancel the booking for this class. We thus expect that email reminders lead to i) more bookings, and ii) fewer no-shows. To test these hypotheses, we estimate a DiD model with individual fixed effects, similar to equation (1), but with different outcome variables.

First, we estimate the impact of the reminders on the number of weekly bookings (column 1 in Table 5), using a Poisson regression. We find an increase in the number of bookings per week equal to 10% (though not statistically significant). Using a linear model (column 2), we find an increase of 0.057 in the number of bookings per week (significant at the 10% level), which translates into an increase of 13%. Given the relatively small share of gym members who attend classes, we also consider the extensive margin of making any positive number of bookings in column (3). We find that reminders lead to significantly more members making at least one booking (an increase of 9%).

We next consider cancellations. In column (4), we show that the number of weekly cancellations increases during the experiment; however, the coefficient is small and not statistically significant. Cancellations are obviously possible only if a booking was made earlier. Thus, we consider in column (5) the share of bookings that are canceled. This regression thus includes only observations for weeks in which the individual made at least one booking. We find a negative coefficient, although it is again small in magnitude and not statistically significant. We conclude that the increase in class visits as a result of the reminders is due to (1) an increase in the number of bookings and (2) a lack of an increase (and perhaps even a decrease) in the share of bookings that are canceled.

The effects of the reminders for the postexperiment period all share the sign of the effect during the experiment. However, none of the effects are statistically significant. This finding is in line with the estimated impact on class attendance for the postexperiment period, which is smaller in magnitude than the estimate for the experiment period and not statistically significant (see Table 3).

3.5 Impact on contract duration and renewal

Having seen persistent effects of the intervention in terms of increased attendance in the postexperiment period, we now investigate whether these increases carry over to the decision on contract renewal once the 12-month contract period ends. One would expect that individuals who were induced by the intervention to exercise more regularly are more likely to remain members of the gym.

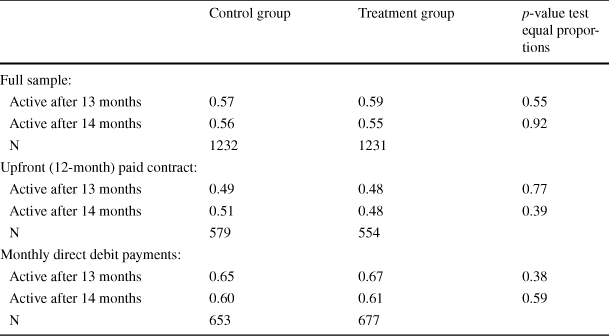

Table 6 Contract renewal after initial 12-month period

|

Control group |

Treatment group |

p-value test equal proportions |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Full sample: |

|||

|

Active after 13 months |

0.57 |

0.59 |

0.55 |

|

Active after 14 months |

0.56 |

0.55 |

0.92 |

|

N |

1232 |

1231 |

|

|

Upfront (12-month) paid contract: |

|||

|

Active after 13 months |

0.49 |

0.48 |

0.77 |

|

Active after 14 months |

0.51 |

0.48 |

0.39 |

|

N |

579 |

554 |

|

|

Monthly direct debit payments: |

|||

|

Active after 13 months |

0.65 |

0.67 |

0.38 |

|

Active after 14 months |

0.60 |

0.61 |

0.59 |

|

N |

653 |

677 |

|

We obtained data on whether individuals buy a new contract (or extend the first contract) and define as the outcome measure an indicator for being a member 13 or 14 months after purchasing the initial contract.Footnote 31 Table 6 shows the share of individuals in the control and treatment groups that were members 13 and 14 months after the initial contract began. In the upper panel, we observe that slightly more than half of our sample had contracts both 13 and 14 months after the initial contract began. The share of members with active contracts is very similar in the treatment and control groups, and the difference is not significant (with a p-value of 0.55 after 13 months and 0.92 after 14 months).

The type of payment of the initial contract (upfront or monthly) is likely to affect the likelihood of contract renewal, and thus, we report the same statistics, split by the type of payment, in the lower panels of Table 6. Again, we find no significant differences between the control and treatment groups for both payment methods after 13 months or after 14 months. Interestingly, the number of contracts is much higher among those who had initially chosen direct debit payments compared to those who had paid upfront. This finding suggests that there is some kind of cancellation delay for contracts with direct debit payment, as also reported by DellaVigna and Malmendier (Reference DellaVigna and Malmendier2006), although some of this difference may result from self-selection into the two payment types.Footnote 32

There are several explanations for why we do not observe any effects on contract duration and renewal. First, if the decision maker is perfectly rational, it could be that the magnitude of the increase in attendance induced by the intervention does not suffice to affect the bigger and financially consequential decision of buying another contract or prolonging the existing one. Second, assuming that the decision maker is not fully rational, she may not update her expectations about future attendance based on past experience and is, if she is in the treatment group, not more likely to prolong the contract than if she were in the control group. Third, some individuals may suffer from a status quo bias (Samuelson and Zeckhauser Reference Samuelson and Zeckhauser1988), taking the current baseline, i.e., being a member of the gym, as the reference point, and thus renew the contract, irrespective of any other considerations. That the majority of memberships in our sample are still active after 13 and 14 months speaks to this hypothesis. It is, of course, possible that a combination of these explanations leads to the observed outcome.

4 Conclusion

Using a large-scale randomized field experiment, we find that short and simple weekly reminders lead to a significant 13% increase in the number of weekly gym visits during the intervention and a slightly lower increase in attendance in the postexperiment period.

We believe that the external validity of our results is relatively strong. Our large sample contains a diverse set of individuals with both students and employed members and a wide range of age groups. Since the gym offers many different sports activities, our results are not based solely on individuals interested in one activity (e.g. weightlifting), but apply to people interested in all types of regular exercise and sports. Finally, average attendance in our sample (approximately once per week) is similar to the commonly found attendance rates but well below the general advice from a health perspective. Our heterogeneity analysis shows that reminders are effective for almost all types of individuals.

We argue that limited attention is the most plausible explanation for the fact that reminders are so effective at increasing exercising frequencies. Gym members might forget to exercise regularly, they might forget to make plans for future attendance, or they might forget to follow through on their plans. Email reminders may overcome these hurdles to reach a higher level of exercising.

There are alternative explanations for why reminders are effective, but those seem less plausible. First, if the reminder emails contain new information (of whichever type), individuals could be induced to re-optimize their attendance. This is unlikely, as the reminders in our study were short and contained very general messages that both experienced and new members should be well aware of (see “Appendix”). Second, the observed effect of reminders could have been due to guilt aversion (see, e.g., Battigalli and Dufwenberg Reference Battigalli and Dufwenberg2009). This concept suggests that guilt-averse individuals experience a utility loss if they believe that they let someone down. In the context of the gym, members could have felt an obligation to attend when they received a reminder email if they believed that the gym—or, rather, the gym’s employees—expected them to come. Given the size of the health club, it is unlikely though that the members felt observed by the employees. Also, members were not addressed with their names in the emails, and there was no mention of any individual attendance. Third, receiving emails from the gym might have induced feelings of guilt towards oneself, e.g., of having bought an expensive contract that is not sufficiently used. This is conceivable, but it is in fact in line with the idea of limited attention. Individuals certainly reflect from time to time on how often they attend the gym compared to their expectations. An email sent by the gym would just bring this reflection to the top of members’ minds.

Our findings point towards the importance of reminders in assisting those who are interested in attaining a higher level of regular exercise. Simple reminders, which essentially have zero marginal cost, have the potential to stimulate individuals to exercise more by ensuring that the option to exercise is not forgotten during busy day-to-day life. Our experimental results show that the impact might even persist after reminders end, potentially due to habit formation.

This poses the question why gyms (or at least the gym in our study) do not send email reminders in the first place. First, the positive impact of reminders might not be known, as large-scale randomized experiments have not been abundant in this area. Second, there may be costs to recipients from sending substantial amounts of reminders (in terms of distraction or annoyance, see, e.g., Damgaard and Gravert Reference Damgaard and Gravert2018). Third, it might not actually be optimal for a gym to increase attendance of existing members. While increased attendance raises operating costs for the gym, it does not produce any additional revenue in the short term.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

See Table 7.

Table 7 Calendar schedule email reminders

|

December 2016 |

January 2017 |

February 2017 |

March 2017 |

April 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

15 (general email) |

9 (reminder) |

6 (reminder) |

7 (reminder) |

3 (reminder) |

|

15 (reminder) |

13 (reminder) |

13 (reminder) |

9 (reminder) |

|

|

24 (reminder) |

19 (reminder) |

21 (reminder) |

||

|

26 (newsletter) |

26 (reminder) |

Reminders were always sent at the beginning of a week. To vary the day of dispatch, we randomized between Sundays, Mondays and Tuesdays. The newsletter on January 26 was sent to all gym members. The lack of a reminder in the fourth week of February was due to a scheduled newsletter, which was, eventually, not sent out by the gym

List of email reminders with header (in chronological order):

1. Get inspired by the broad range of workout possibilities [sent January 9, 2017]

Did you know that we offer more than 200 classes per week? Drop in any time to work out, or sign up for a class on www.fysiken.nu/en/book/. We hope to see you soon!

2. Did you know that you can work out around the clock at Fysiken? [sent January 15, 2017]

Did you know that you can train at Fysiken 24/7? Our facility at Gibraltargatan is now open 24 hours a day. Also our facilities Lindholmen and Kaserntorget have long opening hours. See www.fysiken.nu/en/ for more information. See you soon!

3. Exercise gives you more energy! [sent January 24, 2017]

Did you know that research has shown that working out makes you feel more energetic? Go to our website and get inspired for your next energizing workout: www.fysiken.nu/en/. We hope to see you soon.

4. Regular exercise offers great health benefits! [sent February 6, 2017]

Did you know that regular exercising has huge health benefits such as a boosted immune system? Reap the benefits of regular exercising and sign up for one of Fysiken’s classes at www.fysiken.nu/en/book/. We hope to see you soon!

5. Did you know that regular exercise reduces stress? [sent February 13, 2017]

Research has shown that regular workout reduces your stress levels significantly. Try out one of the many classes we offer. Look at www.fysiken.nu/en/ for more information. See you soon!

6. At Fysiken you can vary your workout! [sent February 19, 2017]

Fysiken offers a huge variety of training activities. For example, you can try out various ball sports, climbing activities and water training. Find more information on www.fysiken.nu/en/ and get inspired! We hope to see you soon!

7. Practice mindfulness at Fysiken [sent March 7, 2017]

Did you know that exercising helps reduce stress and improve concentration? Body and mind are connected—book your yoga, Pilates or Mindfulness class at www.fysiken.nu/en/book/. Welcome!

8. Enter your workout plans into your calendar [sent March 13, 2017]

We all have problems with committing ourselves to a strict workout schedule. Did you know that simply putting reminders in your calendar might help you to better stick to your exercise goals? Inspired? Take a look at www.fysiken.nu/en/. We hope to see you soon.

9. Did you know that regular exercise improves your sleep? [sent March 21, 2017]

Research has shown that regular exercise improves the quality of your sleep. Improve your life now and take a look at our wide range of gym classes at www.fysiken.nu/en/. We hope to see you soon!

10. Work out together with your friends [sent March 26, 2017]

Working out together is more fun - and it helps you commit to going to the gym. Why don’t you contact a friend and schedule a training session right away? Go to www.fysiken.nu/en. We hope to see you soon!

11. At Fysiken you have the widest range of sports activities in town [sent April 3, 2017]

At Fysiken, we offer a huge range of classes and training facilities. You can find the schedule and sign up for classes at www.fysiken.nu/en/book/. Get inspired!

12. Take time for training [sent April 9, 2017]

We know that you are very busy with your job or your studies. But do not forget to get some regular exercise! Look at www.fysiken.nu/en for new inspiration. We hope to see you soon!