It hardly bears repeating that the danger of “falling dominoes” in Southeast Asia was not as acute as it seemed when the United States committed itself to a bloody conflict in Vietnam. What we know today of the relationship between North Vietnam (the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, DRVN) and its two key allies and sponsors, China and the Soviet Union, is enough to put to rest uncritical assumptions about a global, Moscow-directed conspiracy aimed at turning all of Southeast Asia into a sea of red. Finding themselves at odds with the Chinese and the Soviets, the Vietnamese communist leaders worked to preserve their freedom of maneuver while assuring the continuation of political support and the supply of economic and military aid from both. Hanoi kept its eyes on the prize: the defeat of the United States on the battlefield, a task that was possible only with allied support. Moscow and Beijing recognized the importance of this goal but their prize was Vietnam itself, that is to say, its loyalties in the unfolding Sino-Soviet split.

What was it about Vietnam that proved so important to its communist allies? There was a range of issues, from the geopolitical and security rationales to ideological zeal and the fates of world revolution. Historians have explored these questions in depth.Footnote 1 Acknowledging the importance of their contributions, this chapter makes the case for interpreting Chinese and Soviet policies in light of the narratives of political legitimacy. Much as was the case with American involvement in Vietnam, Beijing and Moscow understood the war in terms of opportunities for asserting their own, and undermining each other’s, credibility as an ally. Credibility was central to the Chinese and Soviet bids for leadership in the socialist camp and the Third World, while the notion of leadership was closely related to self-perceptions of legitimacy of the ruling elites. Their costly, long-lasting commitment to Vietnam was, in a sense, not about Vietnam at all: it was about the Sino-Soviet rivalry for leadership.

In the end, Moscow won the contest. Its victory was as much a function of the Soviet material commitment to Hanoi’s war effort as it was a consequence of China’s domestic meltdown. But it was a very costly victory. The Soviets became a party to a distant war that they could neither adequately control nor even fully understand.

A Slide into Conflict, 1960–1964

At the turn of the 1960s, the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and Chairman Mao Zedong of China were on parallel trajectories in Southeast Asia: both wanted to avoid conflict. In the late 1950s Khrushchev had his hands full with other problems. In 1958–9 he was preoccupied with the Berlin crisis, which he himself had started but was desperate to end, and with the unrest in the Middle East, which he did not start but hoped to turn to his advantage. In September 1959 Khrushchev traveled to the United States, meeting President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The positive spirit of their talks at Camp David imbued Khrushchev with hope that the Cold War itself could be quietly wound down, if only the Americans recognized Moscow’s legitimate interests. These did not include Southeast Asia in any meaningful way. By contrast, the Chinese were very interested in what transpired south of the border but primarily from the standpoint of national security rather than revolutionary strategy. China’s domestic difficulties – the failure of the Great Leap Forward – called for a cautious posture in foreign policy.

In the early 1960s North Vietnam drifted perceptibly in China’s direction. Those were the years of the Sino-Soviet polemics, when China openly challenged Moscow’s leadership in the international communist movement. Mao accused Khrushchev of betraying Marxism and colluding with the United States to sell out revolutionary movements around the world. This charge appeared all the more credible after Khrushchev’s capitulation in the Cuban Missile Crisis, in October 1962, when, under pressure from JFK, he had to remove nuclear-tipped missiles. If Khrushchev sold out Cuba, would he not sell out Vietnam as well? These were questions that the Chinese were now raising with the Vietnamese leaders, hoping to win their support.

Hồ Chí Minh was cautious. When Sino-Soviet relations came under strain because of Khrushchev’s falling out with Albania, he pleaded with the Soviet leader to forgive the Albanians. “If a tiger forgives the cat,” he told skeptical Khrushchev, “he will only become more glorious.”Footnote 2 Hồ Chí Minh was genuinely worried that the fracturing of the socialist camp would undercut Vietnam’s war in the South. Mao was unhappy. “Hồ Chí Minh,” he surmised in June 1962, “is afraid that, if N. Khrushchev expelled Albania today, he may tomorrow expel Vietnam too.” He went on: “In a meeting that Hồ Chí Minh had with me, I asked him, why are you afraid? In our country, in China, the grass is growing just fine even though N. Khrushchev is attacking and fighting us. If you do not believe this, go have a stroll around our mountains and see with your own eyes.”Footnote 3 Two months later, Chairman Mao proclaimed the return to class struggle in China’s foreign policy. Because of this new militant posture, and due to growing concern with the increased American presence in South Vietnam, the Chinese upped their political and military commitment to Hanoi.Footnote 4 Meanwhile, North Vietnamese requests for Soviet aid and cash went largely unanswered.Footnote 5

Mao and other Chinese leaders repeatedly assured the Vietnamese that they would back them in the conflict with the United States, even as the Soviets carefully probed for the possibility of a peaceful settlement. Unsurprisingly, by late 1963 the ranks of “pro-Soviet” Vietnamese leaders grew thinner, while the Chinese gained influence by the day. For a time, Hồ kept up the pretense of friendship with the USSR, blaming rumors of Hanoi’s anti-Soviet tilt on “hooligans and reactionary elements.”Footnote 6 But the Soviets knew that Hồ Chí Minh himself was “swimming between the currents” while others, including the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP) general secretary Lê Duẩn, already “stood on the Chinese bank.”Footnote 7 “Pro-Soviet” players in the Vietnamese leadership reported feeling “complete isolation.”Footnote 8

It was not so much a matter of picking and choosing between ideologies, between embracing China’s “class struggle” and renouncing Khrushchev’s “peaceful coexistence.” The question was simpler: the North Vietnamese sought to take advantage of the deteriorating political situation in the South by launching an armed uprising, a decision formalized by a party plenum in December 1963. They needed political support and weapons, which the Chinese were happy to provide, even as Khrushchev, his eyes on better relations with the West, continued to procrastinate. Under these circumstances, North Vietnam’s siding with China was a tactical move in the absence of better options. Khrushchev himself precipitated this shift by ignoring his client’s needs. But, characteristically blind to his own policy failures, he blamed the loss of North Vietnam on the imaginary machinations of “Chinese half-breeds” in the Vietnamese party leadership.Footnote 9 For Khrushchev, the problem of Vietnam was only an aspect of his broader struggle with China, and a rather peripheral aspect at that. The Chinese worried about Vietnam much more, and for a good reason. The situation on the ground continued to deteriorate.

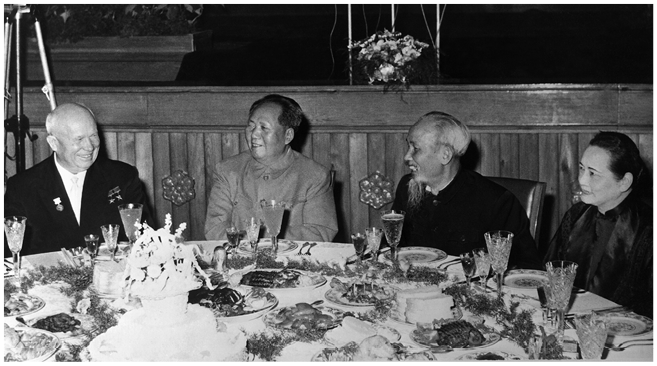

Figure 25.1 Premier Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union, Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Hồ Chí Minh, President of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and Chairman of the Vietnam Workers’ Party, and Soong Ching-Ling, Vice Chairwoman of China (from left to right), dining together in Beijing (October 4, 1959).

The Struggle for Vietnam, 1964–1965

The rapid escalation of American involvement in Vietnam after the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 meant that the war, which Mao and Khrushchev had so hoped to avert in the late 1950s, was now a brutal reality. Khrushchev witnessed the imbroglio from the political sidelines. In October 1964 his comrades-in-leadership overthrew him for reasons that had relatively little to do with foreign relations.Footnote 10 Meanwhile, Mao was egging the Vietnamese on. The escalating Vietnam War developed into the core concern of China’s foreign policy, becoming entangled imperceptibly with a very different struggle that unfolded in China itself. The Soviets half-suspected that the Tonkin Gulf incident was a secret Chinese ploy to prod Vietnam toward an open war with the United States and so instill their allegiance to, and dependence on, China.Footnote 11 There is no evidence of such devious plotting on Mao’s part. But once the war began in earnest, he embraced it with relish. As Mao famously advised the North Vietnamese in October 1964:

If the Americans are determined to invade the inner land, you may allow them to do so … You must not engage your main force in a head-to-head confrontation with them, and must well maintain your main force. My opinion is that so long as the green mountain is there, how can you ever lack firewood?Footnote 12

He preferred to keep the war confined to South Vietnam. But if it expanded to the North, that was fine, too, because the Americans would then find themselves knee-deep in a quagmire.

Three considerations underpinned Beijing’s approach to the deepening conflict. First, the Chinese believed that, for all the dangerous escalation, the chances of a broader regional (never mind a global) conflagration were minimal. The United States was already badly overextended. The more overextended it became, the lower its chances of winning. Speaking in the immediate aftermath of the Tonkin Gulf, Chinese premier Zhou Enlai outlined the stratagem in nearly poetic terms:

If there were just a few more Congos in Africa, a few more Vietnams in Asia, a few more Cubas in Latin America, then America would have to spread 10 fingers to 10 different places, spreading its power very thin … If we make America extend its 10 fingers to 10 different places, then we can chop them off one by one.Footnote 13

It did not matter to the Chinese how long the struggle would take – a hundred years or more, perhaps – but it would end in victory. It was imperative that the United States leave Indochina – indeed, not just leave, but, as Mao put it, “leave with shame.”Footnote 14 Mao valued the Vietnam War for the chance to “humiliate” the Americans, and so undermine their global influence.

Second, the struggle was a good thing because it helped mobilize the “people” – not just the Vietnamese but the Chinese too. The Vietnam War intersected with the trajectory of Chinese domestic politics. Mao’s leftward turn in domestic politics in mid-1962 stemmed from his dissatisfaction with the pace of his country’s revolutionary transformation. Mao now saw an opportunity to drum up support for more radical policies by invoking the threat of war. As he explained shortly after the Tonkin Gulf incident, “though the Americans cannot win in Vietnam, it is useful to have them there because ‘imperialism’ is necessary to unify revolutionary forces, and excesses of ‘imperialism’ are necessary to prove that socialism is the way of the future.”Footnote 15

Millions of Chinese took to the streets in August 1964 to “angrily denounce US imperialist aggression.” The DRVN Embassy in Beijing became a pilgrimage site for expressing officially sanctioned outrage, and for handing in thousands of letters of support, including one by a “78-year-old professor with a long silvery beard” and by a “12-year-old Young Pioneer who, in his summer vacation, had collected signatures to a pledge of support from 11 classmates.”Footnote 16 This outpouring of support was far from spontaneous. The massive demonstrations were organized by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in order to “raise vigilance among the army and the people,” and to “educate [the people] about the concepts of national defence.” The instructions even included the slogans for the demonstrators’ banners: “Resolutely oppose,” “Resolutely support,” and, of course, “Long Live World Peace!”Footnote 17

Third, the war gave Mao an opportunity to assert leadership in the international communist movement amid the deepening conflict with the Soviet Union. The worse the fighting, the better were the grounds to claim that Khrushchev got it wrong: one could not have peaceful coexistence with the United States. By attempting to build bridges to the United States, Khrushchev had betrayed Vietnam’s hopes and the hopes of the entire revolutionary world. That was the message that the Chinese were now selling in Southeast Asia and further afield, and with some success. That said, the Chinese themselves were very careful to keep the war within certain bounds, and signaled to the United States that, as long as the Americans did not directly attack China, Beijing would not intervene. As Zhou Enlai put it in August 1964, “We do not provoke, but answer America’s provocation. As America takes one step, the people of China follow in taking one step … If America wants to expand the war, we will certainly resist.”Footnote 18 The message was reiterated through multiple channels, and it gave China’s policy greater nuance than one could extract from loud proclamations of solidarity.

Moscow’s approach began to change after Khrushchev lost power. The new Soviet leaders Leonid Brezhnev (as First and, later, General Secretary) and Aleksey Kosygin (as prime minister) made an effort to prove that they were truly committed to supporting an ally in need. In late 1964, Brezhnev and Kosygin tried to improve relations with both the Chinese and the Vietnamese. Unlike the former, who remained steadfast in criticizing Soviet “revisionism,” the Vietnamese leaders were eager to rebuild bridges with Moscow. Prime Minister Phạm Vӑn Đồng visited the Soviet Union in November and was promised help. In February 1965 Kosygin traveled to Vietnam. He was in Hanoi when the Americans began their bombing campaign in retaliation for an attack on a US helicopter facility near Pleiku by the National Liberation Front (NLF). This only served to increase the Soviet resolve to aid Vietnam. The underlying rationale for Moscow’s increased interest was that the Soviet leadership faced a deficit of political legitimacy. Aiding Vietnam in a war against “imperialism” helped them to be recognized – by their people, their clients and allies, and the broader world – as the legitimate heirs to the leadership of the socialist camp. An effort to improve relations with China also served the same purpose.

Mao, however, was not inclined to reciprocate. This became clear during Kosygin’s February 1965 trip to Beijing. Kosygin, who passed through China on his way to and from Vietnam, spoke of the need for “united action” to help Hanoi’s war effort. Zhou Enlai initially appeared sympathetic, even enthusiastic. During their meeting on February 10, 1965, Zhou readily agreed that the US bombing campaign gave Moscow and Beijing the freedom to offer the Vietnamese the unconditional support they needed. When Kosygin spoke of sending artillery, tanks, and surface-to-air missiles to North Vietnam, Zhou urged him to supply the equipment more quickly and promised China’s cooperation in transporting these weapons by rail.Footnote 19 If Zhou had actually been in charge of Chinese foreign policy, he and Kosygin could well have worked out a joint approach to North Vietnam, which was what the Vietnamese desperately wanted.

This was not to be. On February 12, 1965, Mao, responding to Soviet pleas with hostile sarcasm, told Kosygin that the Sino-Soviet struggle would last for 10,000 years. “The United States and the USSR are now deciding the world’s destiny,” Mao said acidly. “Well, go ahead and decide. But within the next 10–15 years you will not be able to decide the world’s destiny. It is in the hands of the nations of the world, and not in the hands of the imperialists, exploiters, or revisionists.” Mao appeared unconcerned by the new round of escalation in Vietnam – “So what? What is horrible about the fact that some number of people died?” – and countered Kosygin’s worries about the deepening conflict with optimistic calls for a “revolutionary war.”Footnote 20 Kosygin left Beijing disheartened and empty-handed. The tentative move toward Sino-Soviet rapprochement, of which Kosygin was a foremost advocate in the Soviet leadership, was peremptorily aborted.

The deepening crisis in Sino-Soviet relations made it more difficult for Moscow to supply military aid to North Vietnam. The Chinese flatly refused to establish air corridors for deliveries, held up trains, and rejected the Soviet proposal to cover the Sino-Vietnamese border against US air incursions as a hideous plot to put China under military control.Footnote 21 Still, such obstructionism actually helped Soviet standing in Vietnam, because it made it easier to accuse Beijing of hypocrisy: on the one hand, the Chinese propaganda hammered the Soviets for “selling out” Vietnam; on the other, the Chinese were demonstrably obstructing the delivery of vital supplies to an ally on absurd pretexts. Brezhnev used every opportunity to alert the Vietnamese to this discrepancy between Beijing’s words and actions. “Don’t think that I am trying to cause a quarrel between you and the Chinese,” he told North Vietnamese deputy prime minister and Politburo member Lê Thanh Nghị, when the latter turned up in Moscow in June 1965. “We are surprised and saddened that the Chinese leaders are willing to pay this price to achieve some kind of selfish aims.”Footnote 22

The Chinese, meanwhile, did their best to downplay the extent and the quality of the Soviet aid. “The Soviet leaders are not sincere or serious about providing help to Vietnam,” Zhou Enlai told Lê Thanh Nghị. Zhou reasoned that the Soviets had given Egypt, India, and Indonesia more than they were now giving Vietnam, and this was allegedly “so that Vietnam will not be able to fight big battles, so that it will not be able to start a war.” On the whole, Lê Thanh Nghị suggested in his written report on the trip, the Chinese were “displeased with our attitude toward the Soviet Union.”Footnote 23 This was hardly surprising. As Moscow increased the quantity and the quality of their military aid, providing equipment that China did not have and could not match, the Vietnamese began to move away from their pro-Chinese orientation. Understanding this, the Chinese even attempted to slow down or prevent altogether transport of Soviet weapons by rail, leading to a massive backlog of Vietnam-bound railcars on the Sino-Soviet border.Footnote 24 Moscow then began sending arms by sea – a circuitous and dangerous route. That only helped Brezhnev’s standing in the eyes of the Vietnamese, a reminder that Vietnam’s friendship could be bought if the price was right. Khrushchev had been unwilling to pay but his successors understood that the brutal war unfolding in Southeast Asia was a test of their credibility as the leaders of the socialist world.

War and Diplomacy, 1966–1968

The war continued to escalate. US ground troops carried on conducting combat missions against the NLF, with mounting casualties (with more than 6,000 dead in 1966, the American losses were more than three times greater than the previous year). Meanwhile, with brief respites in May and December 1965, bombs continued to fall on North Vietnam. Operation Rolling Thunder aimed at dissuading Hanoi from supplying their war effort in the South. But it did not work, not even when, in the summer of 1966, the Americans expanded the list of targets by bombing petroleum, oil, and lubricants (POL) facilities. The POL campaign came to an end in September, after a CIA study concluded that it did not significantly diminish Hanoi’s ability to fight. The US president faced divided counsel: Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had lost faith in the war by late 1966. Others, including prominently National Security Advisor Walt Rostow, were upbeat about the prospects. “My feeling is that the pressures on the regime may be greater than most of us realize,” Rostow told LBJ in September.Footnote 25 Yet, two years after the Tonkin Gulf, LBJ was beginning to waver, looking for a way out.

In public, Hanoi presented an impregnable façade of resolve. Summed up in Phạm Vӑn Đồng’s “Four Points” of April 8, 1965, this position called for the unconditional US withdrawal from Vietnam, followed by the country’s unification on communist terms. Continued escalation was spun as evidence of the United States’ growing difficulties, not just in public but also internally, for the benefit of the war-weary audiences in the socialist camp. Records of North Vietnamese discussions with the Soviet leadership often read like propaganda: so many airplanes downed, so many enemies destroyed, and not a word of one’s own losses. As Lê Thanh Nghị explained to Brezhnev in December 1965, “The American imperialists are suffering new defeats … As the latest fighting, and our observations show, American soldiers are afraid of dying in Vietnam. They cannot stand the difficulties and the losses, and cannot spend more than 3–4 days in the swampy areas, in the jungles.”Footnote 26

Careful Soviet probes about potential peace talks were met with stubborn rebuff, presented in terms of: yes, we are in favor of peace talks, but not now. This was the argument Phạm Vӑn Đồng cited to Brezhnev in October 1965 (Brezhnev was amused that the argument was made through the interpreter who read from a prepared text). “The Americans cannot be trusted,” Đồng said. “We don’t want to end up in a trap.”Footnote 27 He did not decipher this reference to a “trap” but, given Hanoi’s bitter experience at the 1954 Geneva Conference, where the North Vietnamese were arm-twisted by their allies into dividing the country along the 17th parallel, it is not surprising that they would be more suspicious the second time around. “An old story,” Brezhnev noted in his diary with evident resignation.Footnote 28

It was an old story but there was new blood spilled every day. Economic losses from bombing were partly made up for by a steady stream of economic aid from the socialist camp, especially the Soviet Union. But there was no making up for the tens of thousands of dead, maimed, and deprived. Recalled Janusz Lewandowski, Poland’s representative at the International Control Commission and (at one point) a crucial interloper in a failed attempt at US–North Vietnamese peace negotiations: “Population was starved, the rations were very limited, you know, the people gathered grass, herbs, finding the crickets … For every American, I think, there were a hundred Vietnamese killed.”Footnote 29 Although an exaggeration, the claim accentuates the brutal reality of war and helps us understand why, from late 1966, the North Vietnamese began sending signals of interest in peace talks. However, the signals were too weak and too equivocal to provide sufficient impetus for serious negotiation. That would have to wait for another two years of carnage and casualties, two years of internal deliberation centered in no small part on the question of China.

The Chinese persisted in their opposition to peace talks. They were at first quite successful. The Sino-Vietnamese relationship seemed to grow ever closer as the war intensified. DRVN leaders were frequent visitors in Beijing, informing, listening, consulting. “At present all the world is depending on you to defeat imperialism,” Chinese foreign minister Chen Yi told Hồ Chí Minh in June 1965, while Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping warned him that Moscow would sell out Vietnam. Hồ Chí Minh played along but there was a perennial concern in Beijing that the Vietnamese might one day tilt the other way: toward the Soviets and toward peace talks. This helps explain the extraordinary lengths to which the Chinese went in trying to prevent the shipments of Soviet aid, and also in warning Hanoi not to take it. “Their help is not sincere,” Zhou cautioned Phạm Vӑn Đồng in October 1965. “The US likes this very much. I want to tell you my opinion. It will be better without the Soviet aid.”Footnote 30 Dong went on to Moscow, where, in talks with Brezhnev, he did exactly what Zhou hoped he would not – asked for aid – but also showed his loyalty by claiming commonality of views with the Chinese: “they have long been helping us.”Footnote 31

The DRVN’s dependence on Chinese aid – light weapons, ammunition, and daily necessities – could partly explain North Vietnam’s opposition to peace talks. This was the preferred Soviet interpretation: Brezhnev and Kosygin were ever prone to see the Chinese hand behind the Vietnamese recalcitrance. But that was not the whole story. Hanoi’s struggle lined up with Mao’s theory of the “people’s war.” When the Vietnamese leaders spoke in well-rehearsed catchphrases that sounded like Chinese propaganda, it was because they believed that propaganda, and were open to Chinese methods of guerrilla warfare. “Fighting a war,” Mao instructed Phạm Vӑn Đồng in April 1967, “is like eating: you eat a bite at a time. It is not hard to understand.”Footnote 32 The Vietnamese thanked Mao profusely for China’s help, and were invariably thanked in return: You are on the frontlines, Mao would say. You are waging the struggle against American imperialism.

In June 1966 Mao proposed to Hồ Chí Minh – half in jest, perhaps – that he would not mind heading down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail to carry on with the struggle. “We wouldn’t be able to vouch [for your safety],” Hồ Chí Minh replied in bemusement. Mao pressed on: “Isn’t this the same thing to die and to be buried in China as to die and be buried in Vietnam? It would be good to be killed by the Americans.”Footnote 33 Mao never went to Vietnam but hundreds of thousands of Chinese did. Between June 1965 and March 1968 a total of some 320,000 railroad, engineering, and minesweeping troops served in North Vietnam (the peak year was 1967, when the number reached 170,000).Footnote 34 One could say that the Vietnam War was organically linked to China in ways that it was not, and never could be, linked to the USSR. Even after the Vietnamese and the Chinese began to develop disagreements, it took years before they proved sufficiently serious to give the Soviets an opening in Vietnam.

Divergences did eventually spring up between Beijing and Hanoi, for two reasons. The first was China’s slide into the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Begun in earnest in mid-1966, this campaign thrust China into radical violence. Senior leaders were purged. Those in “positions of authority” were beaten and tortured by radicalized youngsters. Convulsing in a bacchanalia of rallies and struggle sessions, China turned inward. All ambassadors but one (Huang Hua in Egypt) were recalled from overseas, and diplomacy was downgraded to revolutionary propaganda. The chaos decreased Beijing’s credibility as the DRVN’s protector. Disorder bordering on a civil war, especially in the southern provinces, disrupted the flow of weapons and supplies to Vietnam. Most importantly, Hanoi resented China’s efforts to “export” the Cultural Revolution, especially by relying on the local Chinese community and the railroad troops. There was, as Lê Duẩn put it in 1967, a “crisis of trust” between yesterday’s comrades-in-arms. In an even more telling assessment by the deputy Politburo member Nguyễn Vӑn Vịnh, “as paradoxical as it sounds, we [the Vietnamese] do not fear the Americans but fear the Chinese comrades.”Footnote 35

The second reason was Hanoi’s decision to begin peace talks with the United States in Paris. The discussions began on May 14, 1968, in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive. A brainchild of General Secretary Lê Duẩn, Tet had aimed at overwhelming US forces in South Vietnam in a series of powerful conventional strikes. The idea did not go down well in Beijing and in Moscow but for different reasons. The Chinese were upset that their preference for protracted guerrilla warfare had been ditched in favor of large-scale battles.Footnote 36 The Soviets had long sought a negotiated solution to the war, and did not like further escalation. But the failure of the Tet Offensive prodded Hanoi toward the negotiating table. The Soviets were relieved, and the Chinese outraged.

The Endgame

The DRVN presently showed a little flexibility, agreeing, for instance, to Saigon’s representation at the peace talks. More by innuendo than by diktat, the Soviets continued to encourage their allies to make concessions. Brezhnev was worried by Richard Nixon’s arrival in the White House. “We’ve known Nixon for a long time,” Brezhnev told Phạm Vӑn Đồng in November 1968, days after the Republican presidential nominee clinched victory. “He is distinguished by extreme self-love and great irritability … This does not mean that we are afraid of him. But one must take into account that, in a situation when no solution has been reached, he will have only one policy – to continue the war.”Footnote 37

But the North Vietnamese were not in any great hurry. They interpreted LBJ’s October 31 announcement of ending the bombing of North Vietnam as a momentous victory for the communist forces. “This new victory of ours,” Đồng told Brezhnev in November, “bred the spirit of confusion and decay in the ranks of the enemy, the American and the Saigon armies.” The initiative was in the Vietnamese hands. They had to press on.Footnote 38

Hanoi’s optimism came through in the Vietnamese Workers’ Party Politburo discussions. The records demonstrate that six months into the Nixon administration, the North Vietnamese remained upbeat about the near-term prospects of the ongoing war. This was due to the perceived weakness of South Vietnam’s armed forces, which were supposedly “falling apart,” with three of four top military commanders secretly supportive of the Viet Cong. According to the VWP Central Committee secretary Lê Vӑn Lương (who reported on these developments to the Politburo in early July), Hanoi’s problem was not so much in beating the “puppet” army as in working out what to do with them once they defected: how to feed them and how to sort the good from the bad.Footnote 39 Not long after this Nixon announced his policy of “Vietnamization” of the war: a phase-out of the US military presence accompanied by considerable strengthening of the South Vietnamese forces. Hanoi remained confident of victory just around the corner.Footnote 40

As the 1970s dawned, the end of war was finally in sight. Much of Indochina was in ruins but the North Vietnamese leaders looked forward to their long-sought victory, which would herald Hanoi’s rise to ranks of the leader of, and the socialist bridgehead to, the Third World. These ambitions were compatible with being a Soviet client. As a midsize power, the DRVN desired deference even as it itself deferred to the Kremlin for guidance. Vietnam continued to rely heavily on Moscow’s economic and military aid. Fiercely independent Hanoi accepted this dependence on Soviet largesse, partly because the Vietnamese had little choice, and in part because the Soviets were not competitors for Vietnam’s regional hegemony. Nor, ironically, were the Americans. With the United States on the way out and the Soviets in a detached, advisory role, though generous in contributing weapons, the politics of Southeast Asia were reverting to more ancient rivalries.

Unhealthy tendencies in Sino-Vietnamese relations, present during the early years of the Cultural Revolution, continued to worsen. The feeling in Hanoi was that the Chinese “support our revolution only to the extent to which we support the Cultural Revolution.” Zhou was apologetic, blaming the difficult political situation inside China. “The situation inside our party is very complicated,” he confidentially told the Vietnamese. “These difficulties have reached such a degree that they cannot be resolved at present.”Footnote 41 Externally China was also facing an unprecedented crisis. Following the Sino-Soviet border clashes in March 1969, it seemed that the Soviet Union would invade any moment.

Meanwhile, the Vietnamese were unhappy: not just with the collapse of Chinese aid, not just with meddling in Vietnam’s domestic politics, but with Beijing’s unwillingness to recognize the global importance of the Vietnamese revolution. China had long presented itself as the role model for revolutionary war. Mao instructed visiting revolutionaries – the Vietnamese among them – in the art of guerrilla warfare. The Chinese claimed leadership in the Third World partly by the right of their experience in the revolution and then the war with Korea, where China fought the Americans to a standstill. Now the Vietnamese were more than fighting the Americans to a standstill, emerging as yet another role model in Asia, another leader.

This rivalry was checked by continued Vietnamese obeisance and the decline of Chinese radicalism. In May 1970 Lê Duẩn found Mao more accepting of Hanoi’s conduct of the war and the peace talks in Paris. “You may negotiate,” he told Lê Duẩn. “I am not saying that you cannot negotiate.” “But,” Mao added, “your main energy should be put [into] fighting.” This was one of the last meetings between the Chinese and the Vietnamese leaders, when they still spoke from the same script. Mao was at his militant best: still berating the Americans and the Soviets, still upbeat about the prospects of the global revolution, still full of praise for the Vietnamese war effort. “Who fears whom? Is it you, the Vietnamese, Cambodians, and the people in Southeast Asia, who fear the US imperialists? Or is it the US imperialists who fear you? … It is a great power which fears a small country – when the grass bends as the wind blows, the great power will be in panic.” Lê Duẩn responded with deference and even requested “Chairman Mao’s instructions.”Footnote 42 Yet, even as he encouraged the Vietnamese to continue fighting, the Chinese leader was also carefully exploring the idea of rapprochement with the United States. This led in July 1971 to the bombshell China visit of Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, and the announcement that Nixon himself would soon come to Beijing.

Hanoi was flabbergasted. The Chinese had not consulted them before Kissinger’s trip, and Zhou’s reassurances about how Nixon’s visit to China would be of great benefit to Vietnam, and Beijing’s readiness to increase the aid flow, could hardly make up for the injury, and the insult, of such mistreatment. It was clear that Beijing and Washington had been talking, noted Hanoi’s chief peace negotiator Lê Đức Thọ days after Kissinger’s visit. “But the Chinese invitation to Nixon to visit Beijing was completely unexpected for us.” In November 1971 Phạm Vӑn Đồng visited Beijing in a bid to persuade the Chinese to uninvite Nixon.Footnote 43 In the words of General Võ Nguyên Giáp, who briefed Brezhnev and Kosygin on the visit several days later, Đồng “concluded that the general strategy of the Chinese leaders is a compromise with American imperialism.” “At whose expense will this compromise be reached?” interjected Kosygin. “It’s hard to say,” uttered Giáp. “I think you and I can guess at whose expense.”Footnote 44

As the Vietnamese leaders whetted Brezhnev’s appetite by invoking the bright prospects of a Soviet–Vietnamese revolutionary partnership in Asia, Hanoi’s relationship with Beijing was on a steep downward trajectory. The differences were still carefully papered over: not just in public but also, for the time being, in private. Mao, looking (in Lê Duẩn’s words) “old and very sick,” praised the Vietnamese leaders in a mawkish sort of way when they met in June 1973. “The people of the world, including the Chinese people and the Chinese party, have you to thank,” he said. “You’ve defeated the United States.” He even went as far as to thank the Vietnamese for the Sino-American rapprochement: “Think about it, why did Nixon come to Beijing? If you hadn’t won the war, he wouldn’t have come.”Footnote 45 What struck Lê Duẩn was that this time there was no discussion of the Soviet Union, no scaremongering about the Soviet threat, no pressure to combat “revisionism.” This was a sign of a broader shift in Chinese foreign policy – away from ideology toward Realpolitik. But what role would Vietnam play in this overtly geopolitical game?

A few weeks later Lê Duẩn and Phạm Vӑn Đồng discussed Mao’s intentions with Brezhnev. They were worried about China’s growing ambition in Southeast Asia. Lê Duẩn confided to Brezhnev that since the mid-1960s he had been concerned about the concentration of Chinese troops in the five provinces of southern China. This measure, in theory aimed at securing the DRVN’s rear, was, in Lê Duẩn’s reading, but a part of Mao’s plan “to invade all of Indochina China and Southeast Asia if the circumstances were right.”Footnote 46 He pleaded with Brezhnev to help strengthen Vietnam’s defenses against China.Footnote 47 The Soviets obliged. Their involvement in Vietnam continued to intensify through the 1970s. By 1978 – when the two sides signed an alliance treaty – Vietnam had become one of Moscow’s most important clients, and a key player in its strategy of containing China.

Conclusion

Moscow’s involvement with Vietnam was Brezhnev’s project. Had Khrushchev not been ousted in October 1964, it is unlikely that the Soviet commitment would have been as strong or as lasting as it later became. Although Khrushchev pioneered the Soviet pivot to the Third World, he was in the end quite unconcerned about Vietnam. He even resented his Vietnamese allies. Hanoi’s decision to turn to armed struggle was an irritant in Soviet–American relations at a time when the Soviet leader was seeking rapprochement with Washington. But that was not the main problem. The spirit of “peaceful coexistence” did not prevent Khrushchev from aiding national liberation movements and revolutions around the world. What made the Vietnamese theater so problematic for Khrushchev was that Hanoi’s militancy served China’s interests. He did not think of Vietnam as an East–West problem so much as a Sino-Soviet problem, suspecting the Vietnamese of pro-Chinese leanings. “Winning” Vietnam in this case required him to tone down his disagreements with China and making a massive commitment to Hanoi’s war effort. Khrushchev was unwilling to do that, before or after Tonkin.

Brezhnev and his comrades-in-leadership were an altogether different lot. They faced a deficit of political legitimacy, and the related imperative of securing leadership in the socialist camp. Vietnam offered them an opportunity to demonstrate their revolutionary colors. Supporting Vietnam became a test of leadership that the Soviets were determined not to fail. Moscow’s shift resulted in the DRVN’s return to something of an equidistance between its two powerful patrons. This was an important early achievement of Moscow’s post-Khrushchev diplomacy that the Soviet leaders continued to build on as the war escalated in the late 1960s. This did not mean that the Soviets were prepared to back Vietnam to the hilt. The new Soviet leadership, like Khrushchev, had a broader agenda, which included the East–West détente. Brezhnev and Kosygin used every opportunity to prod their allies toward negotiations with the United States. But they were careful, all the same, not to overdo the prodding for fear of losing Vietnam to Chinese influence.

Supporting Vietnam’s war effort served two related purposes: the first was to advertise Soviet credibility to global revolutionary audiences, in particular would-be clients in the Third World. “Credibility” is an all-too-familiar notion to historians of the American war in Vietnam. Yet the notion of credibility was equally dear to the hearts of the Soviet decision-makers who came to regard Vietnam as a test of their reliability in the face of Chinese accusations of betrayal. Moscow’s (and, for that matter, Beijing’s) involvement in the Vietnam War is therefore best understood not in ideological but in psychological terms, in terms of a struggle for leadership, and not just an East–West struggle but also an East–East struggle.

Second, for the Soviet Union, what happened in the Vietnam War was closely tied to its desire to be recognized as the equal of the United States. “Recognition” was at the center of Brezhnev’s approach to détente. But better relations with the United States did not at all entail curbing Soviet support for revolutionary wars – rather, the opposite. Superpower “equality,” from the Soviet perspective, required a clientele. Clients were what made the Soviet Union a superpower. The same logic worked for China as well. The Chinese were not quite in the same category of “superpowers.” Even so, China’s relationship with Vietnam strengthened Mao’s hand when it came to mending fences with the United States. Mao was stating the obvious when he said the American defeat in Vietnam was what forced Nixon to come to Beijing. Yet the decision-makers in Washington were often under the false impression that recognizing a foe (be it the USSR, China, or anyone else) would in itself prompt the other side to be more “cooperative.” The term itself – “recognition” – entails a follow-up question: recognition as what? Recognition as an “equal” often precluded “cooperation” of the kind that Washington expected.

As the war escalated, commitment by both Beijing and Moscow grew. In the end, this tug-of-war for the DRVN’s loyalty was won by the Soviets. But Moscow’s effort to court Vietnam would not have been nearly as successful had it not been for China’s self-defeating policies. Mao Zedong’s insistence on military struggle was not in itself objectionable, certainly not from Lê Duẩn’s perspective. Like Mao, Lê Duẩn was bitterly opposed to peace talks with the enemy until a decisive victory had been achieved. Where they differed was in their assessment of how long that victory would take, and by what means it was to be achieved, which was why the Tet Offensive of 1968 upset Beijing. The Chinese preferred protracted warfare. Disagreements over military tactics aside, there was frustration in Hanoi with the absurdities of the Cultural Revolution, and fears that it might spill over to Vietnam, causing chaos and undermining the war effort. The Vietnamese leaders’ mounting unease about the political loyalties of the large ethnic Chinese minority was a pointer to deep-seated fears that would poison Sino-Vietnamese relations in the 1970s. But the biggest blow to this relationship of “lips and teeth” was Beijing’s decision to mend fences with the United States, a clear-cut case of “betrayal” that the Soviets tried their best to turn to their advantage – but they did not have to try all that hard.

The end of the Vietnam War occasioned not just Washington’s but also Beijing’s defeat. Moscow, by contrast, emerged as a clear winner. Yet it was a Pyrrhic victory. Once the fighting stopped, reconstruction began, and Brezhnev, having invested so much in Vietnam, had to continue investing. Lê Duẩn and Phạm Vӑn Đồng were quite straightforward with him about Hanoi’s expectations: a massive Soviet aid effort to help “industrialize” Vietnam, in order to show Southeast Asia the practical benefits of socialist orientation. “We have nothing,” Lê Duẩn told Brezhnev, suggesting that everything would have to come from the Soviet bloc, at least for the foreseeable ten to fifteen years.Footnote 48 Brezhnev agreed to cancel all of Hanoi’s debts. Credits kept coming, though, and by 1990 Vietnam had received 16.4 billion rubles in aid, most of which was never repaid. In addition, Soviet military aid to Vietnam in the 1980s alone amounted to more than 4 billion rubles.Footnote 49 Subsidizing Vietnam became a serious burden on the Soviet economy in the 1980s, contributing to Moscow’s financial insolvency. Such were the long-term fruits of the Soviet–Vietnamese “victory” in the war.