There have been thousands of histories of the Vietnam War, but none assigns a pivotal role to international law. Research nevertheless indicates that, more than any history has acknowledged, both state actors and outside observers looked at the war through the prism of international law, whether it came to the legality of American intervention in the first place or to the constraints both sides adopted over the long years of struggle.

Perhaps the most important fact about international law, however, is that it never became a primary focus of how choices were made – not in the hallways of power, not on the fields of battle. Even in garnering public support for opposition to America’s intervention, international law played a small role. “It is a humbling realization of no small moment,” observed Richard Falk in 1973 – at the time the most energetic figure to try to bring the field’s materials to bear on the war – “to acknowledge that only international lawyers have been paying attention to the international law arguments on the war.”Footnote 1 And yet the aftermath of Vietnam showed that it was indeed a pivotal event in the history of international law. In the long run it changed forever how war is fought and how it is talked about.

This chapter offers a synthetic overview of the range of issues in international law that arose during the course of the Vietnam War, especially as Americans took over from the French after Điện Biên Phủ in 1954 and moved, seemingly inexorably, toward massive escalation between 1964 and 1973. The chapter begins by seeking to discern what law applied to the conflict, emphasizing the points of agreement between actors on both sides and observers of different political sympathies concerning the legal status of South Vietnam. The chapter then asks – relying on the prevailing understanding of prior diplomatic events, as well as evolving notions of statehood – what claims were possible and plausible when it came to the legality of American intervention in the war. Next, the chapter addresses the different kinds of warfare in which the United States engaged, from its bombing campaigns over North Vietnamese territory and waters to the changing forms of its counterinsurgency in the South and, later, across the Cambodian border. Finally, the chapter concludes by examining the legal impact of Vietnam: not only how it led to the most significant substantive development of the laws of war since the Geneva Conventions, but also, and equally importantly, how it ensured that international law would play (for good or ill) a central role in debate over and analysis of all future conflicts – particularly those in the current era, in which the United States has returned to counterinsurgent warfare abroad.

However peripheral they may have been alone, or even together, a great many actors addressed international law issues as the war unfolded: governments, the most relevant obviously being those in Hanoi and Saigon, along with Washington; international lawyers around the world, including ones who joined antiwar movements over time; and ordinary people, both those who opposed the war and those who supported it.

All told, concern with the legality of the Vietnam War was at its height in two distinct periods: 1966–7, during which the debate revolved around the legality of the war itself (the jus ad bellum); and 1969–71, when it revolved around the legality of how the war was fought (the jus in bello). Given the impossibility of a full-scale survey (especially of North Vietnamese and non-American legal and public opinion), it will help to introduce at the start the primary actors on whom this chapter focuses. The first and perhaps most significant, in part because it was formed so early after the American escalation, was the Lawyers Committee Concerning American Policy in Vietnam. Organized in 1965 after the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and founded by lawyers in private practice in New York, the Lawyers Committee was important not least because it forced the US government to respond. Soon after its inception, the group attracted prominent international lawyers, such as Falk and John Fried, to argue and refine its positions. On the other side of the legal divide, in the early years of the escalation it was Leonard Meeker, the legal advisor of the US State Department, who publicly clarified his government’s views on central legal questions – around which debate then ensued. And there were other important voices, as well. From a very different direction, the eponymous Russell Tribunal, created in 1966 by the elderly British philosopher Bertrand Russell, stood out in the early years. The twenty-two–person tribunal, which included a number of international legal experts, made its own claims about the legality of the war. Indeed, it anticipated the tremendous debates over atrocities that were to consume attention after the revelation of Mỹ Lai – when an enormous number of activists and groups joined the fray.

Contested Statehood: Was Vietnam One State or Two?

The threshold legal issue in the early period of the war was the status of the territory constituting Vietnam. Was Vietnam one state temporarily divided in two as a result of the Geneva Accords of 1954 ending French colonialism in the region, which brought a nervous peace by drawing a provisional boundary across the country at the 17th parallel? Or was there no “Vietnam” at all, but instead two independent states – the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) in the North and the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) in the South? It is difficult to overstate the importance of this question. The answer determined, in large part, three critical and interrelated legal issues: whether US support for the Saigon government and the DRVN’s support for the National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) violated the principle of nonintervention; whether US bombing campaigns against the DRVN could be justified as collective self-defense of the RVN; and whether, in terms of the applicable rules of the jus in bello, the conflict was international or noninternational. If the RVN was not a state under international law, the United States was illegally intervening in the affairs of the DRVN; without the predicate of the South’s statehood, there was no legal justification for Operation Rolling Thunder – the massive bombing campaign initiated in 1965 – and later bombing attacks on the North; and unless the conflict was international, the conduct of hostilities was governed by almost no rules at all.

Under international law, a political entity qualifies as a state only if it satisfies the four criteria set out in the Montevideo Convention of 1933: (1) a permanent population; (2) a defined territory; (3) a government exercising effective control; and (4) the capacity to enter into relations with other states.Footnote 2 The Montevideo Convention’s focus on the factual conditions of statehood helps clarify the status of Vietnam prior to the Geneva Accords. Neither the DRVN’s Declaration of Independence in September 1945 nor France’s formal recognition of the “Republic of Vietnam” as a free state under Hồ Chí Minh in March 1946Footnote 3 was necessary to establish Vietnam’s statehood. On the contrary, Vietnam existed as a state because Hồ Chí Minh’s provisional government had by that time established its effective control over the entire territory of Vietnam.Footnote 4 Even the Pentagon Papers acknowledge that “when the allies arrived, the Việt Minh were the de facto government in both North and South Vietnam.”Footnote 5

The DRVN lost much of its control during the French Indochina War. Once established, though, a state does not lose its statehood simply because it (temporarily) fails to satisfy the Montevideo criteria. The disputed issue during the French Indochina War was instead whether the legitimate government of Vietnam was the Việt Minh in Hanoi or Bảo Đại, the head of the Associated State of Vietnam (ASVN) that France had recognized in September 1949, in Saigon.Footnote 6 That issue was moot by the time of the Geneva Conference, because the Việt Minh had reasserted its control over nearly all of Vietnam. It is thus not surprising that Hanoi claimed to participate in the conference as the government of the unitary State of Vietnam – a state of affairs that the other participants implicitly acknowledged by “summarily ignor[ing]” the ASVN during the negotiations.Footnote 7

Critically, none of the participants in the conference intended the Geneva Accords to divide Vietnam into two states. The Ceasefire Agreement consistently referred to “Viet-Nam” as a single entity, deeming the two sides of the provisional military demarcation line “zones,” not states, and Article 14 specifically granted administrative authority to the parties “[p]ending the general elections which will bring about the unification of Viet-Nam.” The unsigned Final Declaration was even more explicit: Paragraph 6 insisted that “the military demarcation line is provisional and should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary,” while Paragraph 12 stated that “each member of the Geneva Conference undertakes to respect the sovereignty, the independence, the unity and the territorial integrity of” Vietnam.

Given the clarity of the participants’ intentions and the text of the accords, it is not surprising that, in the immediate aftermath of the Geneva Conference, the United States, the DRVN, and the RVN each asserted that Vietnam was one state – to quote the US government – “temporarily divided against its will.”Footnote 8 But that in no way precludes the possibility that the RVN eventually achieved statehood by establishing the permanent population, defined territory, effective government, and capacity for external relations required by the Montevideo Convention.

A comprehensive factual analysis of that issue is beyond the scope of this chapter. But there is reason to question whether the RVN ever became a state – especially as not even its primary supporter, the United States, ever explicitly took that position. To begin with, it is not clear whether the government led by Ngô Đình Diệm – or by any of his successors – ever exercised the necessary effective control over the territory south of the 17th parallel. Scholars were divided over that question throughout the war. In 1966, for example, Quincy Wright, one of the intellectual leaders of the Lawyers Committee, claimed that South Vietnam lacked “sufficient governmental authority” to qualify as a state.Footnote 9 Seven years later, Eugene Rostow, who had served as Lyndon Johnson’s under secretary of state for political affairs from 1966 to 1969, insisted that South Vietnam exercised its authority “at least as effectively as most governments, and more effectively than many.”Footnote 10

The effective-control issue does not admit of an easy answer. Saigon’s control of South Vietnam was at its apex in 1955 and 1956, when Hanoi was preparing for the reunification of Vietnam through general elections, and then steadily declined thereafter. That might be legally sufficient to establish South Vietnam’s statehood; after all, the Việt Minh also only effectively controlled Vietnam for a short time. But Diệm’s control was likely far more tenuous than the Việt Minh’s. In his classic 1966 article “The Faceless Viet Cong,” for example, George Carver, Jr. wrote that “[i]n the aftermath of Geneva, the area South of the 17th parallel was in a state of political chaos bordering on anarchy,” because Diệm “had only the shell of a government.”Footnote 11

An even more serious issue is whether the Saigon government was so dependent on the United States that the RVN lacked the actual independence necessary to satisfy the Montevideo Convention’s “external relations” requirement. Simply put, “[a]n entity, even one possessing formal marks of independence, which is subject to foreign domination and control on a permanent or long-term basis is not ‘independent’ for the purposes of statehood in international law.”Footnote 12 The Saigon government’s independence from the United States was questioned as soon as the ink was dry on the Geneva Accords, with the French referring to Diệm in 1955 as nothing more than an “American puppet.” More importantly, the US government itself appears to have recognized that the case for South Vietnam’s statehood was anything but iron-clad. The State Department’s formal response to the Lawyers Committee – the Meeker Memorandum (or Memo) – never unequivocally asserted that South Vietnam was a state under international law. On the contrary, it acknowledged that South Vietnam lacked “some of the attributes of an independent sovereign state” and consistently referred to South Vietnam as a “recognized international entity” instead of as a state.Footnote 13

Although it stopped short of asserting the RVN’s statehood, the Meeker Memo emphasized – as did scholars more convinced of the statehood argument – that approximately sixty other states recognized the RVN as a state and that the RVN had been admitted to a variety of United Nations (UN) agencies.Footnote 14 The recognition argument, however, is problematic. The Montevideo Convention affirms that a qualifying entity’s existence “is independent of recognition by the other states,”Footnote 15 what is known as the “declaratory” theory of statehood. That theory has always enjoyed more support – both legal and scholarly – than the “constitutive” theory, which holds that sufficient recognition by other states is an equally necessary condition. In any event, the constitutive theory views recognition as an additional requirement, not one that can compensate for a political entity’s failure to objectively satisfy the Montevideo criteria.Footnote 16

Furthermore, it is simply not the case that “South Vietnam” enjoyed widespread recognition by other states. The number of states that formally recognized the RVN was actually about twenty-five; the other thirty-five recognitions – including those by the United States and United Kingdom – took place before Vietnam was divided. By definition, predivision recognitions (like memberships in UN agencies) could not support the idea that South Vietnam was an independent state or even, as Meeker maintained, a “recognized international entity.”

The Legality of Intervention (jus ad bellum)

Debate raged during the war over whether the Geneva Accords of 1954, agreed by the DRVN and France, allowed for US intervention. Although Articles 16 and 17 of the Ceasefire Agreement prohibited the parties from introducing new soldiers and military equipment into Vietnam, neither the RVN nor the United States signed the agreement. Whether the RVN and the United States were nevertheless bound by the two articles is an exceedingly complex legal question. Notably, however, the Meeker Memorandum did not argue that the RVN and United States were free to violate the Ceasefire Agreement. Instead, Meeker claimed that America’s (ostensibly) minimal assistance to the RVN before 1961 was consistent with Articles 16 and 17, which permitted the replacement of military forces and equipment, while Washington’s much more significant assistance after 1961 was justified by the DRVN’s prior “material breaches” of the two articles.Footnote 17 But it is almost impossible to say with any certainty which party, the DRVN or the RVN/United States, breached Articles 16 and 17 first. Indeed, the International Control Commission, set up to monitor the accords, routinely concluded that both sides had breached the Ceasefire Agreement without taking a position on that issue.

For this reason, controversy quickly turned from the accords to the international law governing external involvement in a conflict. Two legal principles were of cardinal importance: the principle of nonintervention and the prohibition of the use of force. The principle of nonintervention is based on the “Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their Independence and Sovereignty,” which the UN General Assembly adopted unanimously (with one abstention – the United Kingdom) in 1965. According to that principle, “[n]o State has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatsoever, in the internal or external affairs of any other State.”Footnote 18 The Lawyers Committee pressed nonintervention very hard, insisting that the principle, “fundamental in international law,” prohibited the United States from intervening in what it described as the “civil war” in South Vietnam.Footnote 19

The meaning of the principle of nonintervention, however, was (and is) deeply contested, especially in a situation of internal conflict. The term “civil war” has never had a formal legal meaning. Instead, international law has traditionally distinguished between three different levels of conflict within a state: rebellion, insurgency, and belligerency. Domestic violence is a “rebellion” if the threatened government’s police forces are capable of maintaining order. An “insurgency” exists when a rebel group and the government are engaged in armed conflict that requires additional pacification efforts by the government. And a “belligerency” exists where there is general armed conflict within the state, the insurgents are hierarchically organized under responsible command, and the conflict affects other states.Footnote 20

Assuming the RVN qualified as a state, the basic rules concerning intervention in an internal conflict indicate that US assistance to the Saigon government was almost certainly legal. The traditional view at the time was that a state was free to assist a government facing either a rebellion or an insurgency. Indeed, even the Lawyers Committee’s own Richard Falk accepted that rule. The situation was more complicated when hostilities escalated into a belligerency – as was clearly the case in South Vietnam – because at that point the rebels were entitled to the same rights and privileges as the de jure government. But the principle of nonintervention only prohibited a state from assisting the government if it formally recognized the rebels as belligerents and declared itself neutral in the conflict – a discretionary act, and one the United States never contemplated concerning the NLF.

Perhaps recognizing the weakness of its argument that states could not assist a government involved in a civil war, the Lawyers Committee also argued that Saigon was so dependent on the United States that it could not legitimately consent to US assistance: “[t]he present junta in Saigon, and its predecessor ‘governments,’ are appropriately viewed as client regimes of the United States; at no time have they been capable of making an independent ‘request’ to their patron.”Footnote 21 That was a canny argument, because the rule that only an independent government could lawfully request foreign assistance was accepted by both the United States and the Soviet Union – the latter even though the UN had invoked it to condemn Soviet assistance to the Hungarian government in 1956. Whether it was factually justified, however, is difficult to assess.Footnote 22

The Lawyers Committee also vociferously argued that the United States’ direct military intervention in Vietnam – both introducing combat troops into the South and engaging in aerial bombing in the North – violated Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, adopted in 1945, which provides that all members “shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” The Charter’s prohibition on interstate violence is categorical and admits of only two exceptions: authorization by the Security Council (as in Korea) and individual or collective self-defense against armed attack.Footnote 23

In the early days of the escalation, American officials vacillated concerning the legal justification for attacks across the 17th parallel. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident in early August 1964, a State Department legal advisor described the US attacks against four torpedo-boat bases and an oil storage depot in the DRVN as self-defense, while US Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said they were acts of “retaliation” – a colloquial way of describing the doctrine of armed reprisal. Not long thereafter, American officials inconsistently described Operation Flaming Dart I – a series of February 1965 air attacks and bombing raids launched in response to NLF assaults on Camp Holloway, near Pleiku – as “appropriate reprisal action” and (before the UN) as “measures of self-defense.”Footnote 24

By the time of the Meeker Memo, March 1966, the United States no longer referred to its actions as reprisals. In part, that was because there was an emerging consensus in the era – by states and scholars alike – that armed reprisals were inconsistent with the monopoly on legitimate force established by the UN Charter. In fact, during the Security Council debate concerning the Tonkin Gulf, the Czech delegate had pointedly reminded the United States that it had previously condemned both reprisals and “retaliatory raids.” Moreover, with regard to Pleiku, American officials did not even attempt to explain why the NLF’s actions were attributable to the DRVN, a necessary condition of using force against the DRVN regardless of whether the response was styled as an armed reprisal or as self-defense – as the Lawyers Committee pointed out. Any such argument would have been difficult to make in both fact and law.

The Meeker Memo thus sought to shoehorn all US direct military intervention in Vietnam – North and South – into the category of self-defense. The very first sentence of the memo stated that “[i]n response to requests from the government of South Vietnam, the United States has been assisting that country in defending itself against armed attack from the Communist North.” That attack, according to Meeker, consisted of the “infiltration” of “40,000 armed and unarmed guerrillas” into South Vietnam, including “elements of the North Vietnamese army.”Footnote 25

The Lawyers Committee rejected Meeker’s argument on multiple grounds. Most broadly, seizing on his acknowledgment that the RVN might have lacked “some of the attributes of an independent sovereign state,” they argued – extending their argument about nonintervention – that the Saigon regime was so dependent on the United States that it could not legitimately ask Washington to act in its “collective” self-defense. “The relevant question is whether, even granting the widest possible interpretation of self-defense under both the Charter and general international law, a regime that does not possess political autonomy with its own society enjoys a legal right to request military assistance from a foreign country.” That right, the committee insisted, “must be denied.”Footnote 26

The Lawyers Committee also challenged Meeker’s claim that the RVN had been the victim of an armed attack. First, the committee argued that the United States significantly overstated the number of soldiers that had “infiltrated” South Vietnam from the North prior to the initiation of Operation Rolling Thunder and the arrival of US combat forces. In defense of that position, they cited Senator Mark Mansfield’s 1966 report to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which had concluded that infiltration was generally limited to “political cadres and military leadership” until the end of 1964 and that subsequent infiltration of People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) regulars was a “counterresponse” to Saigon’s request for direct military assistance.Footnote 27 The size and timing of the DRVN’s actions, according to the committee, indicated “some intervention by North Vietnam in the civil strife or ‘insurgency’ in South Vietnam, but they do not establish an armed attack within the accepted meaning of Article 51 of the Charter.”Footnote 28

The merits of that argument were inextricably bound to the Lawyers Committee’s insistence that South Vietnam was not a state and thus could not consent to US intervention in the war. If Saigon was capable of consent, the arrival of US combat forces in South Vietnam was lawful and could not justify infiltration of PAVN regulars even as a “counterresponse.” Perhaps recognizing that problem, the Lawyers Committee seized upon Meeker’s frank acknowledgment in his memo that “[i]n the guerrilla war in Viet-Nam, an ‘armed attack’ is not as easily fixed by date and hour as in the case of traditional warfare” and that “[t]here may be some question as to the exact date at which North Viet-Nam’s aggression grew into an ‘armed attack.’”Footnote 29 Those concessions were fatal to Washington’s collective self-defense claim, the Lawyers Committee argued, because they meant that its direct military involvement in the war was a form of anticipatory self-defense prohibited by the UN Charter. This was a sophisticated argument, because the committee did not try to limit self-defense – as many states still did – to situations in which an armed attack had already occurred, which was the most natural reading of Article 51. Instead, they accepted, quoting the classic formulation of imminence in the Caroline case,Footnote 30 that a state could also act when the “necessity of self-defense [was] instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means, and no moment of deliberation.” As the committee pointed out, though, the gradual accretion of Northern soldiers in the South over a number of years hardly satisfied the Caroline standard.

The Lawyers Committee also questioned the proportionality of the US bombing campaigns across the 17th parallel, noting that “these air attacks have from the outset vastly exceeded in destructiveness the Pleiku incidents, and have escalated into a massive, ever-growing war against North Vietnam.”Footnote 31 The committee did so, however, only in the context of whether the United States could justify the campaigns as armed reprisals.Footnote 32 Their narrow emphasis is revealing, because although questions about proportionality now routinely feature in debates over individual and collective self-defense, little attention was paid in the mid-1960s to that principle. Indeed, the Meeker Memo assumed almost carte blanche justification to respond in collective self-defense to “communist aggression,” failing to note any limits at all on the relationship between the predicate attacks and the US response.

Precisely because the United States’ earlier interventions caused a modicum of public debate about their legality under international law, Richard Nixon’s initially secret decision in March 1969 to use air power across the Cambodian border in order to attack NLF “sanctuaries” and to interdict traffic along the Hồ Chí Minh Trail eventually did too. The enormous outcry over the news in March 1970 that Cambodia was being bombed led the US government to elaborate its legal rationale for doing so. The main problem Nixon’s lawyers (including future Chief Justice William Rehnquist) faced was domestic: namely, the lack of congressional approval, as required by the US Constitution’s war powers provisions. But the intervention also appeared legally problematic under international standards insofar as it violated the sovereignty of a state that had formally declared itself neutral in the war.

In a speech to the Dag Hammersköld Forum in New York, John Stevenson, Meeker’s successor as legal advisor to the State Department, addressed that issue. He argued that the bombings were legal because Cambodia was not fulfilling its obligation as a neutral power to prohibit the NLF’s belligerent use of its territory. Stevenson acknowledged that the UN Charter prohibited all force other than in self-defense against an armed attack by a belligerent – and Cambodia had never launched such an attack. But he insisted that the right of self-defense nevertheless justified the United States’ violating Cambodia’s sovereignty, because “a belligerent may take action on a neutral’s territory to prevent violation by another belligerent of the neutral’s neutrality which the neutral cannot or will not prevent.”Footnote 33 This argument neatly solved the attribution problem that had plagued US self-defense arguments since Operation Flaming Dart I by simply not requiring a nonstate actor’s attack to be attributed to a state. But it also directly contradicted the central limit on self-defense that both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations had accepted. Indeed, Abram Chayes, the legal advisor under Kennedy, was so incensed by the Nixon administration’s decision to jettison the attribution requirement that he publicly denounced the Cambodian bombings as illegal under international law.Footnote 34

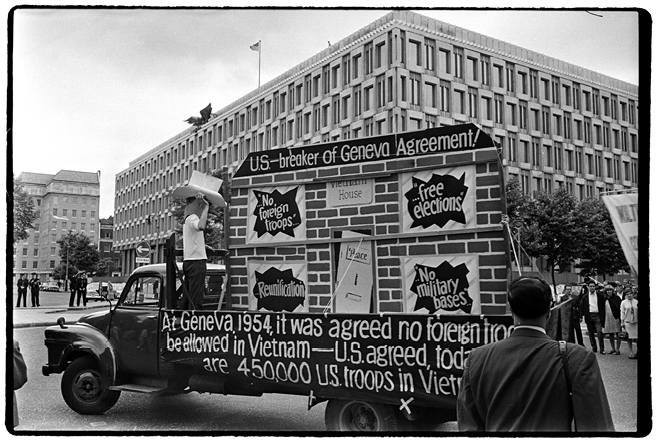

Figure 20.1 Demonstrators call out the USA for violating the Geneva Accords (1954) during a rally in London (July 6, 1967).

The Conduct of Hostilities (jus in bello)

As the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War deepened, and especially after the Mỹ Lai massacre was revealed in 1969, attention to the jus ad bellum, the rules governing the use of interstate force, declined – in part because the intervention had already gone on so long. By 1970, for example, Stevenson could defend the Cambodian operation simply by referring to the prior five years of debate on the legality of the war. Correspondingly, the jus in bello, the rules governing the conduct of hostilities, came to the fore.

Applying international law to the conduct of hostilities, however, presupposed classifying what kind of conflict it was – which again began with whether there were one or two states in Vietnam. The two primary treaty-based sources of law in force at the time, Hague Convention IV of 1907 and the Geneva Conventions of 1949, applied only insofar as the hostilities in Vietnam qualified as an international armed conflict (IAC) – one between two or more states. Insofar as the conflict involved hostilities between a government and an organized armed group, a noninternational armed conflict (NIAC), only one provision applied: Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions.

Hostilities between the DRVN and the United States – for example, bombing campaigns across the 17th parallel – obviously qualified as an IAC. Although the United States refused to acknowledge the existence of an IAC when US soldiers were serving in South Vietnam only in an advisory capacity, it accepted that qualification once it began to bomb North Vietnam.Footnote 35 For its part, the DRVN never denied that it was involved in an IAC with the United States.

Hostilities between North Vietnam and South Vietnam are more difficult to qualify. The DRVN never publicly articulated a position on that issue, because it always denied that its forces were formally engaged in South Vietnam. (Northerners fighting below the 17th parallel were “volunteers,” Hanoi maintained.) By contrast, the United States viewed the conflict as international once large numbers of American, Australian, New Zealand, Korean, and Thai soldiers began to engage in combat in South Vietnam, and eventually convinced the RVN to (reluctantly) accept that qualification.Footnote 36

The most complicated issue – and the most important, because it determined the legality of many US practices during the war – is whether the hostilities in South Vietnam between the NLF and the RVN were part of the larger international armed conflict or were best understood as a NIAC. The parties themselves took the former position, though for very different reasons. In the DRVN’s view, the NLF was engaged in a war of national liberation against the RVN and thus, in keeping with communist legal theory at the time, the conflict was international.Footnote 37 The United States and the RVN denied that the NLF was a national-liberation movement, but they nevertheless insisted that the hostilities in South Vietnam qualified as an IAC because they believed the DRVN both created and controlled the NLF, making the NLF’s hostilities part of its larger conflict with the DRVN.Footnote 38 Interestingly, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) – custodian of the laws of war for more than a century – concluded that the hostilities were an IAC via yet another path: in its view, any “civil war” in which either the legitimate government or the rebels received military support from a foreign state qualified as international.Footnote 39

It is difficult to credit any of these rationales. The ICRC’s theory was inconsistent with state practice at the time, which as noted made clear that foreign states could assist a legitimate government without internationalizing a conflict. Indeed, when the ICRC later formally proposed its position in 1971 during the negotiations that led to the two post-Vietnam Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions (1977), states overwhelmingly rejected it.Footnote 40 The US/RVN position was legally stronger: if the NLF was nothing more than an extension of the DRVN, the conflict between the NLF and the RVN was indeed international. It is anything but clear, however, that the NLF was created and controlled by the DRVN.Footnote 41 If not, the DRVN’s assistance would not have sufficed to internationalize the conflict. The DRVN’s position, in turn, was both legally and factually questionable. Legally, there was no agreement among states at the time that wars of national liberation qualified as IACs – although the First Additional Protocol would ultimately, and controversially, adopt that position. Moreover, as discussed earlier, it is far from self-evident that the NLF was fighting a war of national liberation against the RVN.

US practices whose legality was questioned can be divided into four categories: (1) violations of the principles of distinction and proportionality; (2) use of prohibited weapons of war; (3) mistreatment of POWs; and (4) mistreatment of South Vietnamese civilians. Bombing of the DRVN aside, US practices generally complied with the jus in bello, although individual military units undoubtedly engaged in unlawful behavior.

The principle of distinction, which categorically prohibits the intentional targeting of civilians and civilian objects, is at the heart of international humanitarian law (IHL). Closely related is the principle of proportionality, which prohibits attacks on legitimate targets when the anticipated military advantage is outweighed by the expected collateral civilian damage.Footnote 42 Critics of US involvement in the war questioned whether a number of common practices complied with these principles, which applied in both the North and the South regardless of whether hostilities there qualified as international or noninternational.

A significant amount of criticism was focused on Washington’s bombing campaigns between 1965 and 1968 and again in 1972 (Operation Linebacker and Operation Linebacker II). Critics often denounced the very existence of the campaigns, but they also expressed skepticism about whether they were conducted in accordance with jus in bello principles, particularly distinction. How, critics asked, could such intense bombing of the North – several times the tonnage of bombs the United States dropped during all of World War II – have targeted military objectives alone? It was a natural question, given that counterinsurgency against anticolonial uprisings had long taken the form of using massive air power against civilian populations to destroy morale, including by Americans during World War II (as celebrated Air Force General Curtis LeMay reminded Americans in 1965).Footnote 43 Moreover, early reports of Western journalists in North Vietnam, especially Harrison Salisbury’s articles in the New York Times in the winter of 1966–7, suggested civilian death that was difficult to describe as permissible collateral damage. (Salisbury’s reporting was later scrutinized heavily, including allegations that he relied on DRVN propaganda, but the initial impact of his reporting was enormous.)Footnote 44

The truth was, however, that very few specific rules governing aerial bombardment existed at the time – and as former Nuremberg prosecutor Telford Taylor noted in his enormously successful 1970 book Nuremberg and Vietnam,Footnote 45 no one had been punished for deliberately bombing civilians at Nuremberg, in part because all parties to World War II had engaged in it.Footnote 46 Customary principles surely prohibited directly targeting civilians, but state practice – equally surely – did not rule out strategic bombing of areas populated by civilians. And in any event, no cities were razed by the US Air Force in Vietnam in the way that had occurred a quarter-century before across Europe and in Japan. Moreover, while it was clear that a great deal of bombing of the Northern landscape was difficult to justify (like close air support or village bombings in the South on minimal suspicion of danger), it was equally difficult to disprove the US government’s routine insistence that it bombed only military targets. The factual disputes involved in allegations about indiscriminate bombing even allowed one prominent revisionist historian to claim that “the application of American air power was probably the most restrained in modern warfare.”Footnote 47 Even though the US Air Force occasionally demolished civilian objects – such as the Bach Mai hospital during Operation Linebacker II – the Cornell Air War Study Group was likely correct to assert in 1972 that “the central legal defect” of American bombing in the North and South (as well as in Cambodia and Laos) was not that it violated the principle of distinction, but that it “generally failed to comply with the rule of proportionality.”Footnote 48

Even that conclusion was contestable, given the difficulty involved in comparing military advantage to collateral damage. By the end of the war, though, a number of lawyers, including Taylor himself, were willing to raise serious doubts about American aerial targeting, mainstreaming what had from the beginning been the preserve of marginal critics. In the winter of 1972–3, Taylor traveled to Hanoi with folk singer Joan Baez in order to deliver holiday mail to POWs and happened to be present during the wrath of Linebacker II. When he emerged from the bomb shelter near his hotel, reporters asked him whether DRVN authorities had deliberately shown him Bach Mai and devastated residential areas. He responded: “We might not have seen some things that we would have liked to have seen, but nonetheless we did see the things we saw.” Instead of saying that such aerial fury was tragic but legal – as he had in his book two years earlier – Taylor now claimed that American conduct, though still not comparable to the destruction of cities during World War II, incontestably ran afoul of the cornerstone principles of the laws of war.Footnote 49

A number of other controversial military practices took place in the context of counterinsurgency in the South. A particularly notorious practice was the United States’ liberal use of “free fire” (artillery) and “free strike” (air) zones. Critics alleged that such zones violated the principle of distinction because they permitted US forces to presume that anyone found within a zone following Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) efforts to remove the civilian population was a combatant who could be lawfully attacked. It seems likely that a number of individual military units acted in the manner the critics decry, killing any person they encountered without attempting to distinguish between combatants and civilians. Army regulations concerning “free fire” and “free strike” zones, however, did not permit such callous disregard for the principle of distinction. On the contrary, they specifically stated that “the conduct of fire must be in accordance with established rules of engagement,”Footnote 50 which included the requirement that US forces make “every effort … to avoid civilian casualties.”Footnote 51

Critics also focused on the systematic use of “body counts” as a measure of military success. There was nothing per se illegal about asking American combat soldiers to keep track of the number of PAVN and People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF, the armed wing of the NLF) troops they killed, nor even to encourage them to kill as many as possible, as long as they were required (as they were) to respect the principle of distinction. Body counts are “a necessary feature of war.”Footnote 52 It seems clear, however, that commanders throughout South Vietnam pressured their subordinates to kill unreasonable numbers of PAVN and PLAF forces. Such pressure was bound to lead American soldiers to ignore the distinction between combatants and civilians and simply kill indiscriminately. After all, one ear looked like any other.Footnote 53

Third, critics decried the widespread use of defoliants and herbicides to destroy crops that South Vietnamese civilians needed to survive. Article 23 of the Hague Regulations deems it impermissible “[t]o destroy or seize the enemy’s property, unless such destruction or seizure be imperatively demanded by the necessities of war.” Under Article 23, US soldiers could lawfully destroy crops that were limiting their ability to engage in combat (such as rice paddies PLAF fighters used for cover) or crops that were – to quote the Army Field Manual – “intended solely for consumption by the armed forces.”Footnote 54 But they could not intentionally destroy crops that were not being used for military purposes and that they knew were designated for civilian consumption. That is a fact-specific determination, but the sheer scale of the army’s crop-destruction program – Operation Ranch Hand – makes it difficult to believe that US soldiers did not intentionally target civilian crops.

Critics did not simply allege that the United States was using lawful weapons in unlawful ways, such as using herbicides to destroy civilian crops or flamethrowers to burn villages. They also routinely claimed that the weapons the United States used in Vietnam were themselves unlawful – no matter how they were used.

No weapon aroused as much horror as napalm, which – as reflected in the iconic 1972 photo of Phan Thị Kim Phúc – causes terrible suffering when it comes in contact with human skin. The strongest argument for napalm’s illegality was based on Article 23(e) of the Hague Regulations, which prohibits the use of “arms, projectiles, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering.” The key to Article 23(e), however, is the qualifier “unnecessary,” which requires balancing the suffering a weapon causes against that weapon’s military utility. Given states’ widespread use of napalm for various purposes – such as attacking fortifications and providing flak suppression – prior to Vietnam, it is difficult to argue that napalm itself violates Article 23(e).

Critics also argued that the use of napalm violated international law’s prohibition on asphyxiating or poisoned weapons. That argument was complicated by the fact that the United States had not yet adhered to the Geneva Protocol of 1925, which prohibits the use of “asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of all analogous liquids materials or devices.” Moreover, even if that prohibition had passed into customary international law – a question that divided experts at the time – it was not clear that napalm even qualified as an asphyxiating or poisoned weapon. Indeed, the ICRC concluded in 1969 that “napalm and incendiary weapons in general are not specifically prohibited” by customary international law, a position seconded by the United Nations Group of Consultant Experts on Chemical and Bacteriological (Biological) Weapons.Footnote 55

Criticism of Washington’s use of lachrymatories faced similar problems. Even if the Geneva Protocol could be read to prohibit all gaseous weapons – which the United States denied – the United States was not bound by the Protocol. Moreover, as argued by the United States, customary international law likely prohibited only tear gas that was capable of killing or at least causing lasting damage to health. Most lachrymatories in the American arsenal, such as “ordinary” CS (tear gas), were legal under that standard. The case against defoliants and herbicides, such as the notorious Agent Orange, was weaker still. Because such weapons were rarely used in conflict situations prior to Vietnam, it was difficult for critics to argue that either the Geneva Protocol or customary international law prohibited their use. That said, the use of defoliants prompted more pioneering calls to revise the laws of war than area bombing or “free fire zones” ever did, reflecting a dawning age of ecological consciousness.Footnote 56

Finally, critics took issue with the use of cluster munitions, particularly the CBU-24 (“guava”). Guavas were the “darling of the aviators,” to quote a high-ranking Pentagon official at the time, because they were extremely effective – better even than napalm – at neutralizing anti-aircraft weapons.Footnote 57 Of course, the fact that guavas could disperse explosive fragments over a radius of several miles also made them particularly likely to cause civilian casualties. Regardless, their use was not prohibited by any treaty, and all scholars agreed at the time that there was no customary prohibition of their use.

Throughout the war, detained individuals were mistreated by all of the parties to the conflict. The applicable legal standards were rarely debated: the Geneva Conventions obligated the parties to treat all detainees humanely, regardless of whether they were POWs or civilians. Any kind of violence against detainees was absolutely prohibited. There was significant debate over the distinction between POWs and civilians itself, however, because that distinction mattered in other ways, such as whether a detained person could be prosecuted for actions ostensibly violating IHL. POW status was particularly important concerning the DRVN’s detention of captured American soldiers. Although the DRVN acknowledged that the Geneva Conventions applied to its international armed conflict with the United States, Hanoi insisted that captured American soldiers – particularly downed American flyers like John McCain – were “pirates” who were not entitled to POW status and could be prosecuted in the DRVN’s domestic courts. That claim, which infuriated America, received as much attention during the war as any other legal issue.

On the surface, the DRVN’s claim had no merit: the DRVN acknowledged that it was engaged in an IAC with the United States and that all of the captured pilots were uniformed members of the US Navy or Air Force. But there was one complication: when the DRVN adhered to the Third Geneva Convention in 1957, it submitted a reservation to Article 85, which provides that a POW does not lose his status simply because the detaining state convicts him for violating IHL. According to the reservation, the DRVN did not have to continue treating an individual as a POW if he was “prosecuted for and convicted of war crimes or crimes against humanity.” Going beyond even the Soviet Union, which (like all the communist states) filed the same reservation to Article 85, the DRVN read the “and” disjunctively, insisting that a POW would lose his status as soon as he was charged with an international crime: conviction was not necessary. That reading of the reservation was manifestly incompatible with the object and purpose of Article 85 – to ensure that POWs were provided due process of law when charged with misconduct – because it would permit a state to remove POW status simply by accusing a POW of committing an international crime. The DRVN’s reading of the reservation was thus invalid under normal principles of treaty law.

The United States engaged in no such sleight of hand. It took the position that all PAVN soldiers captured in South Vietnam were entitled to POW status as a matter of law – a straightforward application of the Third Geneva Convention.Footnote 58 The more significant legal question for the United States was the status of captured PLAF fighters who, as insurgents, did not fit easily into any of the recognized categories of POWs. Given that Washington viewed the NLF as created and controlled by the DRVN, it could have extended POW status to the PLAF forces on the ground that they were, to quote the Third Geneva Convention, part of an “organized resistance movement belonging to” the DRVN. Meyrowitz made that case during the war,Footnote 59 but there is no evidence that the United States considered the possibility – likely because the PLAF did not fulfill the Third Geneva Convention’s requirements for such “irregular” armed forces, particularly wearing a fixed and distinctive sign and complying with the laws of war.

Because of the PLAF’s shortcomings, the United States could simply have denied the group POW status, treating them in accordance with Common Article 3 instead of the Third Geneva Convention as a whole. General Westmoreland nevertheless ordered his forces to treat all detained PLAF members as POWs, unless they were captured while engaged in acts of terrorism, sabotage, or espionage.Footnote 60 That was a policy decision, not a legal one – yet it earned widespread praise. Indeed, a delegate of the ICRC called the relevant directive one of the most important “in the history of humanitarian law.”Footnote 61

There is little evidence that US forces regularly mistreated detainees. The same cannot be said, however, of the ARVN. On the contrary, from the moment Americans arrived in South Vietnam as advisors, the United States received reports that the ARVN routinely tortured and mistreated captured PLAF fighters. The United States had no direct legal responsibility for the mistreatment of PLAF troops that the ARVN had captured, but Article 12 of the Third Geneva Convention prohibited it from turning its own detainees over to the ARVN unless it ensured their humane treatment. The United States consistently ignored that prohibition.

South Vietnamese civilians were also mistreated during the war. Two practices drew particular opprobrium from critics. The first was the United States and RVN’s mass relocation of civilians from their homes to specially created “strategic hamlets.” More than 8 million South Vietnamese civilians were relocated between 1961 and 1963, ostensibly to deprive the NLF/PLAF of necessary resources and to win civilians’ “hearts and minds” by providing them with increased security and living standards. The overwhelming majority of civilians were, however, relocated against their will – and conditions in the hamlets were, according to a Senate Judiciary Committee report, almost invariably deplorable. At first glance, therefore, the Strategic Hamlet Program would seem to have violated Article 42 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits interning or assigning residences to civilians unless “the security of the Detaining Power makes it absolutely necessary,” as well as Article 85, which requires living conditions far better than the South Vietnamese actually received. The problem is that those provisions apply only to “Protected Persons”: civilians who are “in the hands of a Party to the conflict … of which they are not nationals.” Under that definition, the South Vietnamese civilians forcibly relocated by the RVN were not Protected Persons. The Strategic Hamlet Program thus did not violate IHL, however ill-conceived and deplorable it might have been.

The second practice was more problematic: the wanton destruction of civilian property by US forces, particularly burning to the ground or massively bombarding entire villages suspected of harboring PLAF fighters. Such collective punishment – holding civilians accountable for the actions of the NLF/PLAF – is categorically prohibited by Article 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Moreover, no Protected Person issue arose in this context, because the South Vietnamese civilians collectively punished were not nationals of the United States.

Mỹ Lai, War Crimes, and Accountability

Interventions that are illegal under international law are not necessarily crimes of war. But it did not take long for critics to accuse the United States of committing aggression against the DRVN. In the aftermath of Mỹ Lai, however, critics de-emphasized aggression in favor of focusing on war crimes committed by US soldiers.

Although members of the Lawyers Committee occasionally accused the United States of committing aggression against North Vietnam – most notably Richard Falk during a Columbia University roundtable on the war in 1971 – the most strident allegations of aggression were leveled by the Russell Tribunal. The work of the tribunal, whose participants included Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Stokely Carmichael (Che Guevara and Herbert Marcuse declined invitations), was greatly facilitated by the DRVN, which financed the tribunal’s fact-finding trips to North Vietnam and hailed it as “the first international tribunal of the masses to try the crimes of aggression committed by US imperialism in Vietnam.”Footnote 62 The United States, by contrast, alternated between denouncing Russell’s politics and ignoring the tribunal completely. After hearing eight days of testimony in May 1967 concerning questions of international law and the impact of Operation Rolling Thunder, the Russell Tribunal issued its verdict that December: the United States was guilty of aggression toward North Vietnam, and its allies Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea were guilty of complicity in aggression.

From a narrowly legal perspective, the Russell Tribunal was difficult to take seriously. No less a critic of the United States than Richard Falk himself condemned the tribunal as a “juridical farce”Footnote 63 – a fair description, given that it had no official status, made almost no attempt to comply with basic principles of fairness, and did not even address the criminal responsibility of specific individuals. Moreover, although the judgment made reference to such legal sources as the UN Charter, the tribunal’s legal analysis was cursory (Russell did not believe in “rigorous adherence to formal definitions”) and its verdict almost impossible to defend. Even if Operation Rolling Thunder violated the UN Charter’s prohibition of the use of force – itself far from obvious, as noted above – it was not necessarily criminal. No treaty in force during the Cold War specifically criminalized aggression, and customary international law – reflecting the Nuremberg Charter, and even sources the Vietnam War itself produced, such as the 1970 Friendly Relations Declaration and the 1973 UN Definition of Aggression – criminalized only “wars” of aggression: namely, those designed to bring about regime change or permanently acquire another state’s territory in order to control its natural and human resources. The bombing of North Vietnam obviously did not fall into that category, which is why even former Nuremberg prosecutors like Telford Taylor and Benjamin Ferencz were skeptical at the time that the United States had committed aggression.

Whatever its legal failings, though, the Russell Tribunal contributed significantly to the public’s understanding of the Vietnam War. The tribunal’s work was widely covered by media around the world and spurred considerable discussion both inside and outside of academia. It also cemented a parallel between the American-instigated trials of major Nazi and Japanese war criminals and the later events, which was fateful after Mỹ Lai, and led many to take more seriously the necessity of individual accountability for other war crimes – especially atrocities. Most prominently, Telford Taylor insisted that, while aggression was off the table, Americans should certainly consider prosecuting war crimes.

Indeed, allegations that all of the parties to the conflict were responsible for war crimes are more difficult to dismiss. The Geneva Conventions require parties to a conflict to apprehend and prosecute persons suspected of committing “grave breaches” of IHL – acts that give rise to individual criminal responsibility. That obligation applies regardless of the suspect’s nationality.

Despite acknowledging that they were bound by the Geneva Conventions, however, the DRVN made no attempt to prosecute its own soldiers who committed war crimes, such as the torture or murder of captured American soldiers. Nor did it ever prosecute the American flyers it shot down over North Vietnam, despite having the legal right to do so – and despite keeping the world on edge for nearly two weeks in July 1966 by announcing that such trials were imminent.

The United States defined war crimes much more broadly than the Geneva Conventions, criminalizing every violation of IHL, not simply the grave breaches.Footnote 64 Nevertheless, no soldier of any nationality was ever convicted of a war crime during the Vietnam War. The United States never prosecuted PAVN soldiers or NLF fighters who committed war crimes, despite creating a procedure for investigating them in 1968.Footnote 65 Moreover, although it could have prosecuted American soldiers in military tribunals for war crimes, as a matter of policy it always court-martialed them instead for violations of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ).

In general, the US decision to charge American soldiers with violating the UCMJ was not problematic: Article 18 of the UCMJ incorporated all war crimes into military law. There was, however, one important absence from the UCMJ: command responsibility. Under IHL, a military commander is criminally responsible for his subordinates’ crimes as long as he either knew or should have known the crimes were being committed. The UCMJ, by contrast, did not (and still does not) contain a general provision on command responsibility. Instead, commanders had to be charged with a form of complicity by omission, a lesser degree of homicide (such as involuntary manslaughter), or – most commonly – dereliction of duty. None of those alternatives, however, were functionally equivalent to command responsibility. Complicity by omission could also be committed negligently, but it required the commander to be present at the scene of his subordinates’ crimes, which excluded in practice all but the lowest-level military commanders. Involuntary manslaughter required the commander to have actual knowledge of his subordinates’ crimes. And dereliction of duty, which could be negligently committed, was punishable at the time by a maximum of three months’ imprisonment.Footnote 66

The difference between IHL and the UCMJ concerning command responsibility was imperfectly understood at the time, leading to widespread confusion concerning the most notorious acquittal during the Vietnam War: that of Captain Ernest Medina, who commanded the units involved in the Mỹ Lai massacre. Numerous scholars, including Telford Taylor, faulted the military judge advocate for instructing the jury that it could not convict Medina unless it believed he had actual knowledge that his soldiers were killing innocent civilians – a much more exacting mental state than IHL’s “knew or should have known” standard for command responsibility, which had been articulated by the American-run Nuremberg Military Tribunals in the aftermath of the more famous Nuremberg trial. Command responsibility, however, played no role in Medina’s court-martial. He was instead charged with involuntary manslaughter under the UCMJ after the judge advocate concluded that complicity in premeditated murder was not available because Medina had not been present during the Mỹ Lai killings. Having reduced the charges to involuntary manslaughter, the judge advocate’s instruction that Medina had to have actual knowledge of the killings was legally correct.Footnote 67

Command responsibility, in short, was never addressed either within the system of military justice or in any other legal forum – a fact that critics of the war after Mỹ Lai hammered tirelessly into the consciousness of the American public: Taylor himself, for example, went on the widely watched Dick Cavett show and suggested that the US commander in Vietnam through 1968, General William Westmoreland, and perhaps even President Lyndon Johnson, were criminally responsible for subordinates’ crimes. Taylor’s suggestion outraged many Americans – starting with Westmoreland himself – but the issue was never adjudicated.Footnote 68

Medina’s lenient treatment was unfortunately typical of the Mỹ Lai defendants. Of the more than two dozen soldiers – enlisted men and officers – charged with criminal offenses concerning the massacre, Lieutenant William Calley was the only one ever convicted. Charges against most of the soldiers were quietly dropped; the remaining few were acquitted by court-martials. Despite high-ranking officers like Mỹ Lai acquittee Colonel Oran Henderson openly acknowledging that “every unit of brigade size has its Mỹ Lai hidden someplace,”Footnote 69 impunity for war crimes was the norm, not the exception, throughout the war. It is impossible to know precisely how many American soldiers were convicted of acts qualifying as war crimes, because the army was the only armed service that kept track of its court-martials – and many of its records are either missing or incomplete. The statistics we do have, however, are striking. Between January 1, 1965 and September 25, 1975 – just over a decade – the army formally registered only 241 formal allegations of war crimes. Of those allegations 163 were dismissed as unsubstantiated, and only fifty-six of the seventy-eight substantiated allegations ever resulted in a court-martial. Thirty-six of those fifty-six court-martials resulted in acquittal, and only twelve of the twenty convictions involved a serious office such as murder, manslaughter, or rape.

The sentences served by the small number of American soldiers convicted of war crime–like acts are also troubling. Records exist concerning twenty-seven marines convicted in court-martials of murdering Vietnamese noncombatants. Although fifteen were originally sentenced to life imprisonment, the longest any of the convicted marines actually spent in confinement – Private First Class John Potter, who had murdered five civilians, including executing a wounded woman from point-blank range with a burst of fire from his machine gun – was twelve years and one month. The actual confinement of the fifteen averaged far less, a mere six and a half years. Indeed, only four of the twenty-seven convicted marines served his original sentence, none of which was longer than five years; the twenty-three other sentences were significantly reduced on appeal by the soldiers’ commanding general, the Navy–Marine Corps Court of Criminal Appeal, the US Court of Military Appeals, or by clemency and parole boards. Overall, the reductions were so significant that even Guenter Lewy, the great revisionist historian, condemned them as being “so light as to eliminate any deterrent effect.”Footnote 70

Conclusion

The Vietnam War’s effect on international law was profound and transformative. In both of the main areas in our survey – the jus ad bellum and the jus in bello – the war led to agitation to change international rules. More importantly, though, the war raised the stakes of international law. Indeed, it was in large part because of Vietnam that international law became, unlike in any prior era, such a contested terrain of political struggle and even a dimension of war itself. As a result, more recent conflicts have mutated into an inherently legal struggle – a fight not merely over who wins, but also over what fights are permissible and how they are allowed to proceed.

It is an extraordinary fact that the United States did not have even an internal legal rationale – much less a publicly articulated one – for escalating the Vietnam War until it was forced to do so by external critics such as the Lawyers Committee. And while those critics made little difference (the war had, after all, already been initiated), others moved to side with them. The Vietnam War took place in the era of decolonization, a process that had already given “new states” (as they were called in the era) extraordinary power to define and redefine international law. International law had once justified the expansion of global empires, but postcolonial states tried to make international law a tool of the decolonization process itself. Vietnam did as much as any other event to prompt an attempt to make international law friendlier to anticolonial struggle.Footnote 71 The results, however, were mixed – especially viewed from the perspective of our own day, when international law coexists with ongoing war in a world that still features profound global hierarchy.

To be brief, the most useful landmark to assess the early success of the anticolonial campaign is the storied UN Declaration on Friendly Relations, negotiated at the height of the Vietnam War and approved by the General Assembly in 1970. Much of its rhetoric, as its name indicates, emphasized peace. But the hard-fought declaration – adopted by consensus after being saved at the last minute from disaster by a series of compromises on contentious points – consecrated the right of self-determination of peoples as an international legal obligation. It also gave novel legality and legitimacy alike to national liberation movements. During the negotiations, the United States and other Western powers had hoped to reserve to states their traditional authority to suppress insurrection and to intervene in support of states facing insurgencies fought under the banner of “self-determination.” New states nevertheless succeeded in having the declaration interpret the UN Charter’s prohibition on the use of force to cover “any forcible action which deprives peoples … of their right to self-determination,” as well as to interpret “nonintervention” to bar such action. What this meant was that, while leaving some matters within the domestic jurisdiction of states, the international legal order in principle approved uses of force by national liberation movements and recognition of those movements by other states. Had the Vietnam War not been raging at the time, it is doubtful that such breakthroughs would have been possible.Footnote 72 And like the declaration’s prohibition on reprisals and criminalization of wars of aggression, they made international law a newly significant hurdle for hegemonic states to clear.

It would nevertheless be false to suggest that such breakthroughs were clear and uncontested, or that Vietnam did not leave legacies that have unexpectedly served the United States in the very different era of the global war on terror. The most vivid example of how the Vietnam War licensed future American force, and not merely imposed limits on it (or vindicated uses of force seen to fit with decolonization), comes from the resurrection of the justification for the Cambodian incursion after 9/11. In spite of the vast disparity of circumstance, counterterrorism has recently renewed the desire to use force against nonstate actors who launch transnational attacks that cannot be attributed to the territorial state. And almost overnight, a doctrine has arisen – with citation to the American interdiction of the NLF/PLAF’s Cambodian sanctuaries – that permits forcible intervention if and when a state is “unable or unwilling” to prevent nonstate actors from using their territory for belligerent purposes. For example, the Cambodian episode, though enormously controversial at the time, has been invoked in support of the proposition that state practice permits the United States to attack the Islamic State (ISIS) on the territory of Syria without the Syrian government’s consent.

Whatever its complex and spotty legacy for international rules governing the resort to force, the Vietnam era more clearly transformed rules for the conduct of hostilities. Indeed, those rules were not widely understood as primarily humane in intent until Vietnam and other wars of decolonization prompted the creative rebranding of the field as “international humanitarian law.”Footnote 73 What this involved was of major significance, quite apart from the rewriting of the rules of war – largely sponsored by the postcolonial states – through the adoption of the Additional Protocols in 1977. Not only did the United States not bother with the jus in bello until required by Vietnam’s opponents, they assumed that it would satisfy the world to announce their scrupulous adherence to the 1949 Geneva Conventions. Since Vietnam, by enormous contrast, American policymakers have routinely tried to exempt the wars to come from the ever-accreting rules of IHL.

The fate of Additional Protocol I itself is a case in point. The US delegation, led by George Aldrich, a longtime State Department lawyer who had served as Kissinger’s legal advisor for the Paris Peace Accords, played a key role in negotiating Protocol I and was generally satisfied with the end result. Nevertheless, although the United States signed the Protocol in 1977, President Ronald Reagan ultimately accepted the recommendation of the Department of Defense a decade later to not submit it to the Senate for ratification. The department objected to a number of provisions in Protocol I, particularly those that made it easier for irregular armed forces to qualify for the combatant’s privilege to kill and the prohibition on means and methods of warfare (such as Agent Orange) that could cause widespread and long-term damage to the natural environment.Footnote 74 The straw that broke the camel’s back, however, was Article 4(1), which deemed international – and thus subject to IHL in its entirety – “armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial domination and alien occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their self-determination.” The United States categorically rejected Article 4(1), which had been written with such groups as the African National Congress (ANC) and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in mind, because it wanted “to deny these groups legitimacy as international actors.”Footnote 75

The result of these changes and controversies was fateful for the future. In the decades after Mỹ Lai, and in direct response to the public relations disaster it represented, the United States’ military self-legalized. In particular, the Judge Advocates General Corps in all the armed services immediately assumed a vastly expanded role. During the Vietnam War, it had been an outfit for processing criminal allegations against American service members – a role that was largely insignificant before Mỹ Lai because so few war crimes were reported. By the time of 9/11, by contrast, a new body of “operational law” was central to even the targeting decisions of the most powerful states (including the United States) in an historically unprecedented manner.Footnote 76

To be sure, the tremendous inflation of legal awareness and the proliferation of international jus in bello rules has not necessarily made war more compliant, let alone more humane. It is nevertheless due to the transformation that Vietnam wrought that debate on the war on terror since 9/11 has so often taken the form of jousting about whether counterterrorism efforts are both humane and legally compliant. No American intervention abroad since 9/11 has led to debate over the legality of intervention itself (the jus ad bellum) with the intensity of the years after 1965. Nevertheless, in seeming compensation, there is now almost permanent debate about whether the United States is conducting hostilities in a legal manner (the jus in bello). It is important to ponder whether the world is better off, all things considered, where constraints on the use of force have weakened even as rules on the way states fight receive both preeminent and unprecedented attention from professional lawyers and the general public alike. But there is no doubt that the war in Vietnam and its aftermath make the question necessary to consider.

The environmental history of the Vietnam War is unique in the twentieth century for the unprecedented scale of aerial bombing and use of incendiaries such as napalm, as well as the United States military’s use of tactical herbicides to destroy forest cover in combat zones. The most widely used herbicide was called Agent Orange, named after the orange stripe on drums containing the herbicides 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D. Specially equipped US Air Force cargo planes covered about one-third of South Vietnam’s forests with some 21 million gallons of the herbicide. When reports surfaced in 1969 and 1970 suggesting that a dioxin contaminant in it caused birth defects, environmental and antiwar activists joined forces, labeling this intentional destruction of Vietnam’s forests and widespread toxic exposure “ecocide.”Footnote 1 The Hanoi government repeatedly decried the herbicide-spraying as a war crime violating the 1925 Geneva Protocol banning the use of chemical weapons. After the war, as more veterans reported strange illnesses, class-action lawsuits erupted that held American public attention in the 1980s until, in 1991, the US Congress passed an Agent Orange Act guaranteeing funding for independent scientific research and health care for veterans, at least for US veterans. For the 3–4 million Vietnamese who were exposed to the toxic hotspots where tactical herbicides had leaked into the ground, there was minimal medical support and little in the way of cleanups, until very recently. These two issues, responding to health claims and remediating hotspots, remained top level for over thirty years of US–Vietnam relations, and only in the past decade have both sides reached new agreements as the United States has committed more than $300 million for remediation efforts at its former bases.Footnote 2

The Agent Orange story is unique for many reasons, and it is addressed in more detail below, as well as in several dozen books and documentaries, but this was just one of a broad spectrum of the war’s environmental legacies. Drawing on recent trends in environmental and military history, this chapter aims to provide a more comprehensive sketch of the environmental legacies of the Vietnam War. Besides the effects of bombing and herbicides, these include inquiries into the “footprints” of warfare in urban and industrial development, in ethnic and demographic shifts in former war zones, in the dispersion of invasive species, and even in the creation of wilderness or conservation areas. Historians have only recently begun to grapple with a set of military processes called “militarization” that includes not only following events on the battlefield, but also looking at the ways military activity and occupation affect political systems, logistics networks, cultural affairs, tourism, and migration. Feminist scholar Cynthia Enloe’s studies on militarism, masculinity, and gender relations, especially in the peripheries of American bases in the Philippines and Okinawa, extends analyses of the American military’s influence far beyond the battlefield and the base, exploring military legacies in advertising, sex work, and tourism.Footnote 3 This chapter considers the Vietnam War’s legacies in a similarly wide-ranging manner but with respect to landscapes and ecosystems. The term “landscape” is used to recognize natural and built environments that are understood in both physical and social or cultural terms. Ecosystems describe mostly physical phenomena, including human activities, and they describe larger webs of environmental events connected to human and nonhuman life, geologic activity, and climatic stimuli.Footnote 4 This chapter considers the environmental legacies of the Vietnam War with respect to a wider set of military processes, the varied landscapes of Vietnam, and rapidly changing ecosystems.

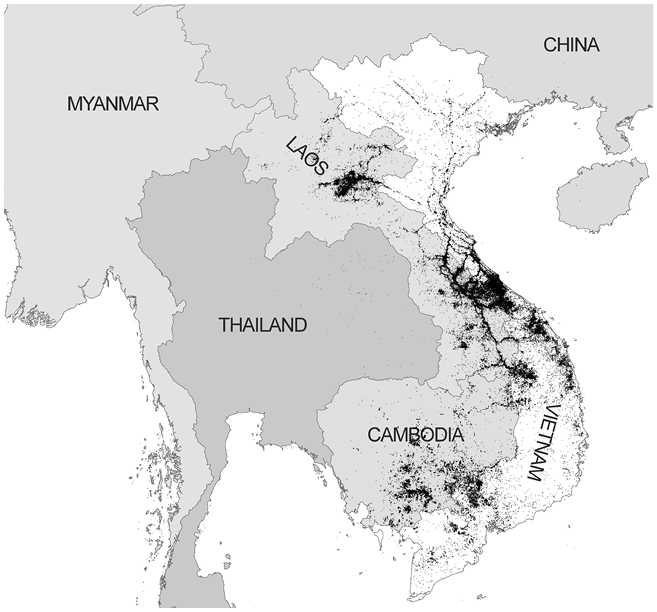

The environmental legacies of the Vietnam War extend far beyond areas scarred by bombing or toxic chemicals. Military activities such as base operations, road construction, and population resettlement remade landscapes, from the Chinese border to Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and the Mekong River Delta. War left indelible footprints on Vietnamese cities, from Soviet- and East German–designed housing blocks built in the North to airports, highways, and deep-sea ports built in the South. The war accelerated new trends in agriculture, and it dramatically reworked the ethnic landscapes of Vietnam’s Highlands. From an historical perspective, the challenge in studying the Vietnam War’s environmental legacies begins with the problem of contextualization. How might one tease out specific impacts from the 1960–75 era versus decades of military conflict that preceded it or events that followed in the Third Indochina War? How did legacies differ from one regional context to another? Many impacts, including those of Agent Orange, were targeted to specific locales, so how can we assess environmental legacies without losing these local particularities of place and ecology?

Timescapes