In 1911 the Glasgow tobacco merchant F. & J. Smith released a series of fifty cigarette cards profiling “Famous Explorers” from Marco Polo to Robert Falcon Scott. Occupying the thirty-fourth position in this mostly British roster—and appearing among various luminaries of African exploration, including Mungo Park and Richard Burton—is a less familiar figure, Verney Lovett Cameron (1844–1894) (fig. 1). While he has now lapsed into relative obscurity, Cameron was celebrated enough in the early twentieth century to appear in the imperial ephemera that were conscripted into the period's advertising campaigns. “In 1872,” reads the synopsis on the reverse of the collectible, “the Royal Geographical Society sent Verney Lovett Cameron in charge of an expedition to find Livingstone. [. . .] He was the first explorer to cross Africa from E. to W.” Cameron's was an expedition, however, that had exceeded its brief. Having learned early in the journey that David Livingstone was dead, he made the controversial decision to continue traveling, first retrieving the missionary-explorer's journals from Ujiji, then surveying Lake Tanganyika, and then following the Lualaba before traversing the Luba heartland, Katanga, and Angola.Footnote 1 The vast expense of Cameron's expedition provoked ire in some quarters of the Royal Geographical Society, but his transcontinental journey was nevertheless enough to secure the Founder's Medal and win a place among the period's foremost explorers.Footnote 2

Figure 1. F & J. Smith's Cigarettes, V. L. Cameron (1911), author's private collection.

In revisiting Cameron, on whom research has been scarce for several decades, the aim is not to rehabilitate his reputation nor to argue for his significant contribution to geographical knowledge. Rather, this article is concerned with Cameron as an author and with exploration as a literary enterprise. Cameron was certainly among the more prolific of explorer authors; in addition to his most famous work, Across Africa (1877), a narrative that traced the transcontinental expedition, he published Our Future Highway (1880) after a journey from Turkey to India and co-authored To the Gold Coast for Gold (1883) with Richard Burton following an expeditionary survey in West Africa. But in the mid-1880s Cameron's authorial career diverted from works of exploration toward popular fiction; in the space of several years, he published eight adventures, most of which were set in Africa. Titles like In Savage Africa (1887) and Harry Raymond: Adventures among Pirates, Slavers and Cannibals (1886) were commended for an educational value grounded in their author's on-the-spot witness. In Savage Africa, according to the Daily News, offered “a good many glimpses of the life and natural history” of terrain spanning “the old Coast to Zanzibar,”Footnote 3 while the Liverpool Mercury commended its effort “to give the young reader a very fair idea of the latest geographical discoveries.”Footnote 4 Yet such remarks, which frame Cameron's turn to adventure as a pedagogical exercise, do not fully account for his literary project. Why, I ask here, should an established author of expeditionary science compose works of prose fiction?

In what follows, I situate Cameron's work in a broader fictional turn among nineteenth-century travelers of Africa.Footnote 5 Focusing on two of his works, The Adventures of Herbert Massey in Eastern Africa (1887) and his more unusual The Queen's Land; or, Ard al Malakat (1886), I argue that explorers sought literary forms that operated outside the formal channels of institutional geography and official expeditionary discourse. Drawing on Gérard Genette's delineation of the “sequel” and “transposition,” I show how Cameron's fiction extended his preoccupation with “commercial geography” and private enterprise while also opening the way to surprising alternative conceptualizations of geographical travel. Herbert Massey, I argue, uses fictional adventure to invite capitalist venture and specifically to advertise East Africa as amenable to administration by chartered company. The highly esoteric plot of The Queen's Land, by contrast, offers an allegory of geographical travel that at once celebrates the explorer's expertise and casts expeditions as the source of secret and unspeakable knowledge. In this novel, the experiences of exploration are coded as occult intelligence to be concealed rather than revealed.

Re-forming Exploration

This case study in the literary culture of expeditions contributes to what has been called “critical exploration studies.”Footnote 6 Analytical approaches to modern exploratory travel date at least to the postcolonial turn in the 1970s, in which travel writings were central among those texts reevaluated for their participation in imperial discourses, but it is in more recent decades that “exploration” has become the focused object of an interdisciplinary field. In place of celebratory historiographies dwelling on heroic exploits, scholarship has instead interrogated eighteenth- and nineteenth-century exploration as what Dane Kennedy calls a “knowledge-producing enterprise.”Footnote 7 Considerable attention, particularly from historians and geographers of science, has been devoted to elaborating exploration's mechanisms of knowledge production; following Bruno Latour, scholars have placed individual explorers within scientific networks and examined the influence of metropolitan institutions—like the Royal Geographical Society and Kew Gardens—in shaping expeditionary objectives and interpreting the information they collected.Footnote 8 Such analyses have extended insight into exploration's promotion of imperial interests while also demonstrating complex motivations behind expeditions that are not reducible to empire. Lately, increased examination of in-field experiences has further complicated the knowledge project of exploration; explorers regularly struggled with the reliability of their instruments, found themselves in vulnerable situations, and faced debilitating health issues. As Martin and Armston-Sheret put it, “nineteenth-century European practices of knowledge production were not the rational or disembodied processes they are often presented as.”Footnote 9 Crucially, moreover, explorers were far from independent agents. In many African contexts, they depended on preexisting caravan networks and the labor of indigenous agents, like porters, guides, and interpreters. Foregrounding neglected actors has resulted in exploration being reframed as a more collaborative and intercultural enterprise than previously recognized.Footnote 10

Central to this critical reappraisal has been careful assessment of the multifarious documents of exploration. Indeed, if exploration was a knowledge project, it was a project contingent on texts. From materials written in the field like letters and diaries to the books that travelers published on their return, expeditions involved the production of records. Most crucial was the expeditionary narrative, usually accompanied by maps; for metropolitan science, as Felix Driver puts it, “a journey of exploration only really counted as such when it was described by a narrative.”Footnote 11 A considerable body of work has now scrutinized the production of travelogues, calling attention to authorial revision and editorial interventions of publishers’ agents that together demonstrate how authorized accounts were often subject to stage management. Yet while texts were negotiated or reshaped during the publication process, the composition of a literary manuscript itself was a late stage in the manufacturing of an expedition's record. Following the guidance of learned societies, explorers generally kept notebooks that formed the basis for more sustained journals, which jointly provided the source material for the major work. As Roy Bridges has argued, expeditionary documentation was produced in multiple phases, beginning with the “raw” record of first observations; “the published text is a third or even later stage production perhaps considerably altered from the original record.”Footnote 12 Recently, first-phase records have received renewed attention; Adrian Wisnicki urges interrogation of “the diverse materials that constitute the expeditionary archive” but places emphasis on raw records as repositories of “unadulterated discursive and material evidence of the intercultural dynamics involved” in expeditions.Footnote 13 Taken together, research on in-field composition and the later publication process shows that analyzing exploration requires disentangling its “inscriptive practices.”Footnote 14

Engaging with explorer fiction complicates existing accounts of the “multi-layered” nature of the expeditionary archive.Footnote 15 Crucially, where explorers wrote prose fiction, the position of the travelogue as the definitive word on an expedition becomes further destabilized. Such texts should not be discounted due to their avowedly imaginative status. Rather, they constitute a further layer of expeditionary documentation that requires the same level of critical attention that has been given to other forms of record. The range of nineteenth-century explorers who wrote prose fiction about Africa is considerable. In addition to Cameron, it includes Sarah Bowdich, a naturalist who traveled in the Gold Coast and the Gambia; Samuel Baker, a central figure in the search for the source of the Nile; Henry Morton Stanley, known for “finding” Livingstone and for tracing the course of the Congo; Winwood Reade, an antireligious polemicist and freethinker who undertook three journeys in West Africa; and Joseph Thomson, whose journeys included an expedition to Lake Tanganyika and another across Maasailand to Lake Victoria and Mount Elgon. There is little doubt that explorers were motivated to compose fiction by the possibility of financial reward. Writing books for the popular market provided a way for them to capitalize on their travels and on any previous expeditionary narratives they had written. It was, then, related to the professionalization of travel in the nineteenth century; as exploration became a career with journeys commissioned by learned societies, notes Brian Murray, “literary labour” became a major channel through which explorers secured their income.Footnote 16 Also critical was the period's flourishing celebrity culture, fostered by an expanding media and the emergence of a more educated public.Footnote 17 If explorers provided enticing material for newspapers and courted press attention in turn, fiction presented another avenue for fame—one that was encouraged by publishers.Footnote 18 Indeed, what Driver calls the period's “proliferating discourse on geographical exploration” is coming to light; in addition to periodical papers, newspaper reports, and geographical narratives, expeditions were mediated in “an array of other formats for the education and entertainment of the literate classes,” including juvenile editions, translations, and heroic biography.Footnote 19 Clearly, explorers’ imaginative writings were a key means to intervene in the vigorous print culture surrounding the geographical enterprise.

The pursuit of fame and remuneration, however, presents only a partial explanation for exploration's fictional turn. It can be understood more fully by paying greater heed to literary form. For the appeal that imaginative literature had for a series of travelers suggests that fictional forms had capabilities that were not readily available in textualities more often associated with exploration. As Caroline Levine has urged, any literary form has a set of “affordances,” a term that signals “both the particular constraints and possibilities” that it carries; forms, in other words, are at once limiting and enabling in distinctive ways.Footnote 20 The potential of fiction for Victorian explorers begins to be clarified by way of contrast to the scientific expeditionary narrative as it took shape from the eighteenth century. The expeditionary narrative was a form that enabled the production of geographical knowledge by providing a regulated mode of reportage. Over the course of the eighteenth century, as Dane Kennedy has argued, explorers were increasingly held to new evidential “standards that demanded verification through quantitative measurement and other scientific methods.”Footnote 21 Practices that had developed in maritime navigation—such as a “daily written record of events, observations, and instrument readings”—were transferred into the arena of terrestrial exploration. In multiple editions of Hints to Travellers (first published in 1854), the Royal Geographical Society offered explorers systematic guidance with the aim of disciplining their observation and recording practices. In their published narratives, therefore, it was beholden on travelers to demonstrate their “ocular authority” by showing that they had followed appropriate protocols.Footnote 22 Since expeditions were not immediately repeatable, the matter of credibility had heightened significance; as a result, explorers followed literary conventions to signpost their reliability. For instance, prefaces signaling affiliation with learned societies and paying tribute to scientific patrons were standard, as were apparently verbatim passages extracted from diaries. Literary style was also a technology of authority; there were different routes to cultivating trust, but it was common to associate plain, unadorned prose with truthful content.Footnote 23

Prose fiction offered an alternative to the expeditionary narrative that was not regulated by the same protocols or expectations. In fiction, explorers deployed media that operated outside the parameters of institutional science and—as my case study shows—offered latitude to re-present the experience of exploration. Indeed, when most explorers wrote fiction, they had not only already traveled but had already published other expeditionary writings. In such cases, the imaginative work functions as a kind of “sequel” in the sense articulated by narrative theorist Gérard Genette. In Genette's taxonomy, the sequel is of course a text written to “capitalize on a first or even second success.” But it also opens new perspectives on the original. It is not the same as a “continuation” of the preceding text, which simply resumes the earlier work to “bring it to a close”; rather, the sequel takes the prior text “beyond what was initially considered to be its ending.”Footnote 24 This conceptualization encourages attention to the ways that explorer novels supplement earlier expeditionary accounts, whether by extending or complicating their preoccupations. Yet as an alternative mode of narration, explorer fiction does not always operate only as sequel but can become what Genette calls a “[s]erious transformation, or transposition.” The transposition is a text that interacts significantly with an earlier one through a variety of “procedures”; for instance, it might involve spatial or temporal alteration, a shift in narrator and point of view, or a change in medium.Footnote 25 Explorer fiction is always a “formal” transposition that reflects a decision to narrate exploratory travel in literary forms other than the expeditionary narrative, but it can also become a significant “thematic transformation” that introduces quite new concerns.Footnote 26 In fact, the formal shift is crucial in facilitating the reimagining that characterizes most explorer fiction; at the broadest level, the introduction of fictitious characters, invented speech, and a narrator distinct from the author not only licensed feats of reimagination but afforded a distance that was unavailable in the expeditionary narrative. If forms are not passive receptacles of content but, as Nathan Hensley argues, “shaping protocols,” then to engage with form is to deal with “mediation,” or the “formal codes through which information is transmitted and, in the act of transmission, inevitably changed.” Understanding form as “conceptually generative,” argues Hensley, encourages a reading practice attentive to the “productive reconfigurations and critical recoding operations––that is, acts of thinking––texts themselves perform.”Footnote 27 Framing explorer fiction, whether romance, short story, or novel, as a suite of forms that could re-mediate expeditions heightens attention to how these texts offer new angles on exploration.

Commercial Geography and Chartered Imperialism

Having had a dual career as a continental explorer and naval officer, it is no surprise that Cameron chose adventure when he turned to fiction in the 1880s. His works drew on existing traditions, following authors of African fiction like R. M. Ballantyne and maritime fiction like Frederick Marryat. The books he produced are characterized by a blend of nautical and terrestrial; an opening maritime episode tends to be followed by an extended African plotline covering considerable geographical terrain. In crucial respects, these imaginative texts are an extension of initiatives that had occupied him since his expedition in search of Livingstone. In this sense, many of his books operate as “sequels,” devised to support a politico-imperial project of “commercial geography” and imperialism by chartered company.

In the immediate aftermath of the Livingstone East Coast Expedition, Cameron had established himself as an imperial exponent.Footnote 28 In a piece written on his return, he called for measures to “colonise Central Africa” and anticipated the day that he would “see the Union Jack flying permanently in the centre of Africa” (1873–75).Footnote 29 Even during his expedition, Cameron had shown imperial sensibilities by attempting some unauthorized, and never ratified, “treaty-making” to extend Britain's influence.Footnote 30 However, by the mid-1880s Cameron was dissatisfied with Britain's response to imperial opportunities and concerned that its interests were under threat. As he watched the proceedings of the 1884–85 Berlin Conference, he became convinced that its principles—particularly the doctrine of “effective occupation”—were militating against British influence. By 1890 Cameron was reflecting on a pattern of diminishment over the previous decade: “roads and countries which should have been British, or under British influence, have passed from our control, and, as far as can be seen, will never again be ours.”Footnote 31

Cameron's desire to redress the problems of imperial politics animated his chief initiative of the mid-1880s. In 1884 he founded the British Commercial Geographical Society, an association that sought to use geographical knowledge to identify markets for British trade. The primary goal was “[t]o collect from all portions of the Globe information of a geographical character which may have a bearing on commerce.” To this end, the society would appoint corresponding agents who would return periodic reports on their region's imports and exports. Within the society's remit would be details of raw materials, trade routes, “Commercial Hygiene,” engineering projects relating to trade, and the conditions of ports. Commercial geography would also rely on the practical findings of exploratory travelers whose expeditions it would support.Footnote 32 Exploration, in other words, was envisaged as an instrument of market expansion.

Cameron was motivated to spearhead the initiative by quickening international competition. In his paper proposing the society at Mansion House, he argued that Britain had languished behind other European countries in promoting geography's commercial applications. Cameron thought he was responding to a problem in British geography by orienting the subject more explicitly to global interests. He was clear that the neglect of commercial geography had real-world effects, for it left an educational deficit that placed Britain at a competitive disadvantage. He argued that “trade––even in the British Colonies––had been wrested from English merchants by strangers, educated and instructed by the commercial geographical societies of their various nations.” Indeed, Cameron framed the commercial instrumentalization of geography as a matter of imperial prestige. Recoiling from the “magnitude of the scheme,” he argued, would be a marker of decline, a clear indication that “the decadence of the British Empire had commenced.”Footnote 33 Cameron's ambitious scheme soon folded due to insufficient financial support, but he did not reject the ideology that underpinned it; in his vision, geography should be in the service of commerce, and commerce should be in the service of imperial interests.

Cameron's commitment to market enterprise intensified following the attempt at a new society. Over the next decade, he involved himself in various African business ventures and propagated the merits of chartered companies. By this stage, Cameron had long been interested in using chartered companies for administrative purposes, having mooted the idea to his father in 1875: a principal means to tackle slavery, he had argued, “would be to grant a charter to a great company like the old H.E.I.C. [Honourable East India Company].”Footnote 34 In Across Africa, Cameron revisited the idea, suggesting that the Congo and Zambezi river systems could be “utilised for commercial purposes” by coming “under the control of a great company.”Footnote 35 In fact, Cameron later reported that he had lobbied for a British charter in East Africa but was dismissed by officials.Footnote 36 Nonetheless, he redoubled his work on imperial charters in the 1880s. This was precipitated by the Sudan Crisis, which culminated in the death of General Gordon during the siege of Khartoum. Pondering solutions to the dominance of the Mahdists––the forces led by Muhammad Ahmad, who claimed divine mandate for an Islamic state and had rebelled against Egyptian authority—Cameron became convinced that private interests provided the best pathway. The region, he proposed in the National Review, should be administered by a company that would be subsidized in the short-term by the British government to support the task of stabilizing the region, before becoming self-sufficient. Expressing remarkable confidence in corporation governance, he asserted that “the company ought soon to restore order and tranquillity in the Soudan, and also prove a financial success.”Footnote 37

Cameron's position was not simply theoretical. As Simon Mollan has shown, Cameron and Francis William Fox, vice chairman of the Anti-Slavery Society, lobbied Lord Salisbury to support a scheme for a company along East India Company lines. These efforts, while ultimately unsuccessful, represented an attempt to integrate Sudan into “the British imperial system” through capitalist ventures.Footnote 38 By 1890, Cameron was even arguing that chartered companies were superior to crown colonies and the consular administration of protectorates. Where colonial administrations were “non-progressive” because bureaucratic obstacles impeded spending, private enterprise was inherently dynamic. Since chartered companies were “instituted for the purposes of commercial gain,” their “instinct” was “to push on everything that is likely to promote commerce and thereby to increase the return on its commercial capital.”Footnote 39 Clearly, Cameron's confidence in company rule emerged from a philosophical commitment to the productivity of a for-profit system.

When Cameron turned to fiction, it was no doubt itself a commercial measure. He reported having “spent far more than [his] limited means warranted” pursuing geographical and business ventures and may have needed an alternative revenue stream.Footnote 40 But his adventure fiction was more intimately connected to his commercial-imperial preoccupations, for he framed it explicitly as a political project. In a preface to one of his novels, Cameron dedicated his work to the “boys of Britain” on whom he laid imperial responsibility. “[T]he future of the British Empire will depend upon them, and the more they know of her vast dependencies the more fitted they will be for the duties and responsibilities of that glorious heritage.”Footnote 41 In the 1880s there were concerted efforts to develop British geography teaching at the secondary level, following an extended review by John Scott Keltie that revealed a curriculum which compared unfavorably with syllabi in Germany and France.Footnote 42 Cameron's effort to educate readers for imperial service can certainly be interpreted as an attempt to invigorate geography among school-age readers. But he did so, more precisely, in a way that was closely allied with the objectives of the British Commercial Geographical Society and its emphasis on international rivals. “British people in general,” he argued, “do not realize how important to us as a commercial nation is the future of Africa, and we are unfortunately allowing foreign nations to benefit by the labours of Livingstone, Burton, and other British explorers.”Footnote 43 It was an understanding of geography and commerce as mutually supportive instruments of imperialism, in the context of international competition, that motivated Cameron's interventions in the boys’ market.

Ecocidal Adventure: Elephants and Empire in East Africa

One of Cameron's books, The Adventures of Herbert Massey in Eastern Africa, demonstrates his use of fiction to mediate and extend his preoccupations. Set in Zanzibar and the East African hinterland, it invites interpretation as a sequel by revisiting areas through which Cameron traveled in the 1870s. Beginning onboard a New Bedford whaler, the novel follows young Herbert Massey from life at sea to an extended East African journey. Herbert's father, the captain, is heir to the Shevinton peerage but has taken up an anonymous life as a New England whaler because of persecution from his own brother.Footnote 44 It is their work cruising for whales around the Zanzibar archipelago that takes them into the politically fraught dynamic of East Africa. The plot transitions from whaling novel to African adventure when a new crew is taken on at Zanzibar and then mutinies, leaving Herbert and two freed slaves stranded at Latham Island. They are picked up by an Arab dhow and taken to Kilwa, but an earlier altercation with authorities at Pemba over the emancipated slaves has made Herbert persona non grata; in order to prevent their rescue, he and his companions are sent “up country” in the custody of a trader, Abd-el-Kadr, who is commencing an ivory expedition in the interlacustrine region (191). Abd-el-Kadr agrees to help Herbert return to Zanzibar, but the hostilities in Pemba make it necessary to first escape the vicinity through an excursion into the interior. Having joined the caravan through coercion, Herbert becomes the merchant's indispensable karani (secretary) and by the end of the novel leads a portion of the retinue “under the British ensign” (335).

Published in 1887, Cameron's novel appeared at a fraught moment in imperial politics in East Africa.Footnote 45 Since the early 1860s, Zanzibar had essentially been a British client state, but there was renewed concern in the 1880s about the sultanate and the East African regions that formed its dominions. Despite a British–Zanzibari treaty to quash the slave trade, an expansion of traffic from the island caused a problem for Britain's antislavery policy. Zanzibar also had strategic value as a port on the trade route to India via the Cape, while the East African hinterland was believed to have untapped economic potential.Footnote 46 From late 1884, moreover, East Africa became the site of international rivalry following the treaty-making expedition of Carl Peters and the Society for German Colonization. This foreign presence in part of Britain's “informal empire” stimulated negotiations that led to the demarcation of British and German “spheres of influence.”Footnote 47 The result was the Anglo–German Boundary Agreement of 1886–87, which delimited Zanzibar's territory and divided a vast swathe of East Africa into a British northern zone and German southern zone; this paved the way for German East Africa and British protectorates over Zanzibar and inland territories including Uganda.

In Herbert Massey, Cameron wrote directly into this evolving situation with a plot that showcased political disarray in Zanzibar and its dominions. Set in the recent past, during the rule of Majid bin Said (r. 1856–70), the Zanzibari state appears divided by faction; the Pemba group hostile to the Masseys owes allegiance to Said Barghash, a “pretender to the sultanate” plotting to undermine his brother Majid, who is better disposed to the British. The fact that the Masseys were fired on in Pemba astonishes the British consul, Captain Martin, and a senior naval officer, Captain Galbraith, who take it as confirmation that Barghash would soon make “some fresh attempt on Zanzibar” (105). This representation of the recent past has direct bearing on the politics of the present. When the novel was published, Barghash bin Said was sultan, having succeeded his brother sixteen years earlier. In representing Barghash as an aspirant ruler who resisted Majid's authority, Cameron was drawing from real historical events; Barghash had attempted to stop his brother succeeding to the sultanate in 1856 and had led an unsuccessful insurrection in 1859.Footnote 48 But in revisiting this recent history, Cameron construes the current sultan in a politically antagonistic light. In this narrative, Barghash has questionable legitimacy and is a source of both political division and anti-British sentiment. The volatile political landscape of the past is mobilized to discredit the political situation of the present; the sultanate, the novel implies, is unstable and occupied by an interloper hostile to British interests.

This representation provides the basis for an argument about British intervention. In a discussion of Zanzibar's political problems, Captain Galbraith traces them to the partition of the Omani Empire: “[T]he whole question of the politics of Zanzibar and Muscat are very complicated,” he notes, “and have been ever since Syud Said, the old Imaum, died and divided his dominions” (105–6). Captain Massey pushes further, wondering if the real trouble is not “[t]he mode of succession among Mahommedans.” Indeed, Massey argues that such political instability legitimates annexation: “I cannot see why England [. . .] does not at once solve the question by proclaiming a sovereignty over the Zanzibar dominions.” Galbraith agrees but notes that “we have some agreement with France, by which we have tied our hands in the matter” (106). In this passing reference to the Zanzibar Guarantee Treaty (1862), in which France and Britain agreed to protect the independence of the Muscat and Zanzibar sultanates, the book suggests that the imposition of British sovereignty might be ideal but was presently debarred.Footnote 49

With direct rule and protectorate status foreclosed, the remainder of the book works toward an alternative possibility for the territory through which Herbert travels. The book, I argue, plots the East African hinterland as suited to the administration of a chartered company, acting as a sequel that extends the commercial-imperial ideas Cameron had articulated as early as Across Africa. It does so chiefly through an ecocidal plot centering on the mass destruction of elephants. The expeditionary portion of the novel is structured around a search for elephant grounds; Abd-el-Kadr is an ivory trader whose caravan is journeying toward hunting grounds in present-day Tanzania. The party splits into three, the first journeying south, the second toward the north end of Lake Nyasa, and the third toward another large lake that Herbert suspects is Tanganyika. In selecting these pathways, the caravan's groups pursue lines that had been adopted by trading expeditions since the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 50 The third group, led by Abd-el-Kadr, does not travel far before meeting local hunters who inform them of a nearby lake where elephants gathered. From this point, hunting dominates the next forty or so pages (284–325).

In some respects, Cameron's rendition of hunting aligns with representations that abound in the period's African adventure fiction. Big game encounters, it has been argued, appear as potent expressions of ideology, symbolizing encounters between “civilization” and “savagery” and celebrating prized characteristics of imperial masculinity.Footnote 51 Although the book capitalizes on individual heroics, however, it is less interested in hunting for sport than in hunting as an industrial trade. In this respect, Herbert's background in whaling—a form of hunting associated more with the products derived from blubber and baleen than with trophies—is no accident.Footnote 52 His prior employment might equip him for the thrill of the chase, but its more interesting function is to establish the connection between hunting and commerce; the elephant appears in the adventure as nothing less than the whale of Africa, an animal at the center of a booming commodity trade.

It is the industrialization of commerce in ivory that concerns the extended hunt scene at the heart of the book. In this episode, the focus is not on Herbert's prowess but on East African technologies of the hunt that allow for mass slaughter. The strategy pursued by local hunters—employed by Abd-el-Kadr—involves mutilating elephants while they sleep in the lake with only their trunk tips above water: men in canoes approach with “sharp swords and knives and cut off the tips of their trunk, when the elephants, not being able to breathe, were very soon drowned, and sank to the bottom; after two or three days their bodies floated and could be towed to the shore” (300). The first such outing allows 97 out of a 400-strong herd to be dispatched, while three subsequent trips allow a further 144 to be killed (312). The lake hunt is then followed by a large-scale game drive, in which hunters stampede the herd into pits using fire, “drums, horns, guns and all sound-making instruments” (311). The result is a massacre: “soon the screams and trumpetings of the affrighted elephants could be heard, and the fall of many of them as they blundered into the pit-falls” (314). With 83 more elephants “trapped in the pit-falls,” the total kills in just a few days amount to 321 (316).

The annihilation of elephants is in part a display of what Cameron regarded as the excess of East African and Arab hunting methods. As John Miller argues, it was common for hunting narratives to place responsibility for species decline on non-European profligacy; “the improvidence of ‘natives’” could be “held up as an exemplar of a congenital irresponsibility that demands British rule.”Footnote 53 Certainly, Herbert balks at the method, which departs from the logic of fair play and risk that was so often valorized in hunt scenes designed to affirm imperial masculinity.Footnote 54 He finds it “very revolting that many of these happy animals should in a few hours be slaughtered” and resolves not to participate since “he thought the mode of killing them a cruel one” (302). At a broad level, then, the elephant slaughter in Herbert Massey serves to invite the regulating influence of British governance. Yet the novel registers an ambivalence in Herbert toward the ecocidal spectacle. At Juma's prompting, he decides to watch “how the hunt was conducted” because “it was a sight that one could scarcely ever have a chance of witnessing” (302–3). The display that follows prompts conflicting impulses: Herbert feels “a sort of fascination” in watching the canoes—for it reminds him of whaling—and though he determines “not to go again to witness the havoc,” he still “could not help congratulating Abd-el-Kadr on the good fortune which was attending him” (303–4). Moral repugnance may trump admiration, but it is tempered by a commercial sentiment that acknowledges the profits realizable through ivory. Herbert's mixed reaction configures the scene as one not only of depredation but of commercial opportunity; the novel imagines an East African ivory market of superabundance while showcasing its depletion in the absence of regulation.

The African ivory trade grew enormously in the nineteenth century, driven by the expansion of global commodity markets. By the 1840s, the East African trade had surpassed the west, as industrial capitalism put a premium on softer savannah tusks, which were easier to carve.Footnote 55 Considerable depletion had taken place by the 1880s, but as Keith Somerville notes, this did not result in a diminished trade but in “a constant search for new and more lucrative hunting grounds.”Footnote 56 Writing into this context, Herbert Massey provides a vision that invites a chartered company into East African commercial space. Indeed, while the book publicizes an ivory market—at risk of overextraction—it displays other sources of wealth for prospective investors. Toward the end of his journey, Herbert stumbles on a prodigious gold seam. Spotting “something glittering in the sand,” he tracks the “main body” to a rock formation at the center of a rapid, which he discovers is “permeated with gold” (356–57, 360). Since the locals are unaware of the element's value—disparaging it as “jungle brass”—the novel advertises a lucrative mineral source, which operates as a symbol of untapped market resources (361). Herbert Massey therefore promotes the trade prospects that Cameron had proclaimed in the aftermath of his transcontinental expedition. In Across Africa, he had anticipated that overhunting would exhaust ivory supplies. “Ivory is not likely to last forever (or for long) as the main export from Africa; indeed the ruthless manner in which the elephants are destroyed and harassed has already begun to show its effects.” In that event, however, Cameron was confident that “the vegetable and mineral products of this marvellous land” presented alternatives for trade and that “vast fortunes will reward those who may be the pioneers of commerce.”Footnote 57

As a sequel to Cameron's expeditionary narrative, Herbert Massey is an outworking of his view that a period of transition in East African trade presented unique opportunities for commercial adventurers. Published in the context of negotiations between Britain and Germany, the book promoted this vision at an acute political juncture. Unsurprisingly, since Cameron had earlier lobbied for a British charter, he was dispirited by how events in the region transpired. In the division of East Africa into two spheres, he saw an unfortunate concession to Germany. As Cameron complained several years later, “I spent a good deal of time and money in endeavouring to obtain a charter to work the countries in Eastern Africa, which have now passed into the hands of the Germans.”Footnote 58 Indeed, the British strategy for the region disappointed him profoundly. Writing to Burton, he blamed matters on William Mackinnon, the Scottish businessman who led negotiations with Peters and whose Imperial British East African Company was granted the northern concession.Footnote 59 It is likely that Cameron was aggrieved not only by the loss of the southern sphere but by Mackinnon's receipt of the charter. Certainly, Cameron resented that others profited from schemes he claimed to have originated: “others have availed themselves of my work and of my ideas without [. . .] in any shape or form recompensing me.”Footnote 60 Herbert Massey made the case for commercial companies in East Africa, but the charters that were granted—both German and British—were far from what he hoped for.

Esoteric Travel: Lost Worlds and Occult Knowledge

In the same year that most of his African novels appeared (1886), Cameron published an adventure with Swan Sonnenschein, The Queen's Land; or, Ard Al Malakat, that combines African exploration with the supernatural. More specifically, drawing on the period's flourishing “occultism”—a renewed preoccupation with gnosis, the mystical, and diverse esoteric traditions—Cameron interwove magical happenings and occult knowledge into a narrative of expeditionary travel.Footnote 61 As an outlier in Cameron's oeuvre, this book occupies an adjacent position to his other works. Where I have read Herbert Massey as a sequel, The Queen's Land is better read as a “serious transposition” that has a more complicated relationship with Cameron's imperial and commercial preoccupations. The Queen's Land, I argue, participates in the ideology that animates his wider literary project but, through its thematic and formal transformation, simultaneously presents alternative ways of conceptualizing expeditionary travel.

Cameron's adventure follows a trio of Freemasons—an independent gentleman, Jock Murray; an officer of the third Bombay Light Cavalry, Tom Hardy; and an Arab traveler, Hamees ibn Haméd—on a journey from Merka (present-day Somalia), in search of an “unknown kingdom” populated by “light-coloured” subjects.Footnote 62 They are, it emerges, looking for the lost land of the Queen of Sheba. Soon after the outset, the narrative introduces magical happenings. Hardy has “dabbled in mysticism” and believes “that some persons have powers which are denied to ordinary mortals” (29). Hamees commands the genie Tebaza and is an aspiring pupil of Amasis, “one of the magicians who stood before Pharoah” (103). Murray is initially skeptical of magic, but a lesson in numerology from a rabbi gifts him powers, including the ability to heal anyone using a “cabalistic combination of numbers” (163). Crucially, the rabbi also gives him the novel's key enchanted object: “a small case ornamented with uncut emeralds,” which turns out to be the stone from the signet of Solomon (17). A ring gifted from Murray's friend, Trevelyan, who is descended from the Arthurian mage Merlin, also allows him to receive telepathic messages. Armed with esoteric knowledge and magical tools, the party pass through various ordeals before arriving in the “country of Saba” (194). There, they find that the queen has been in a trance since the days of Solomon and that the kingdom is ruled by a coterie who worship “the demon Amolak” (240). By returning the stone of Solomon, the Freemason party defeats Amolak, breaks the trance, and restores political order.

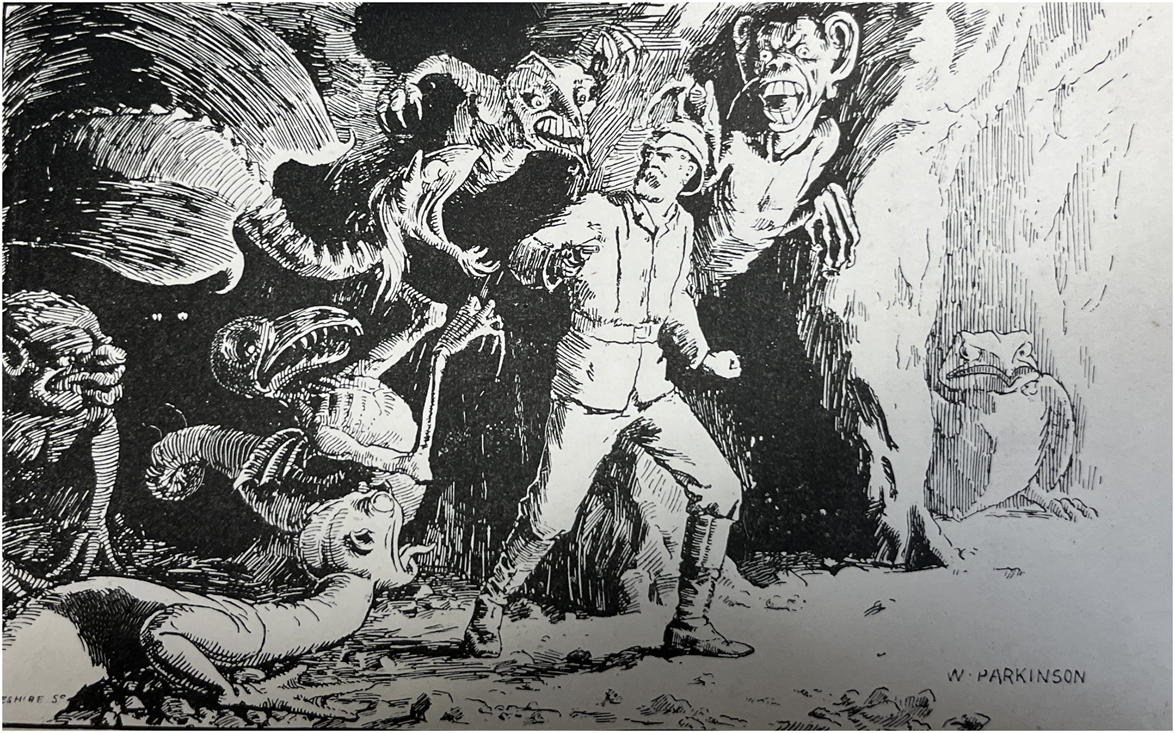

The extent to which this outlandish plot deviates from Cameron's other adventures signals that it was not aimed primarily at a younger readership. The change in protagonists, from adolescents to members of a male fraternity, itself marks this shift. And the narrative also enters territory that would likely have been deemed inappropriate for children by Cameron's more conservative publishers, like Thomas Nelson. For example, in one scene the men witness priests of Amolak “all stripped stark naked,” “attended by six hideous and deformed beings,” and preparing to perform “infernal rites” on a group of infants (234). That the work's primary intended audience was not younger children is confirmed by the archival record. When the book failed to sell well, Sonnenschein's partner F. Lowrey wrote to Cameron to explain the problem. The issue was not simply that “the booksellers say that you have been writing too many books,” but that The Queen's Land appeared in a different form; according to the booksellers, it was “the only one that is not brought out as a boy's book.” Lowrey's proposal was to repackage The Queen's Land by “illustrating the volume, & giving it a gift-book binding,” so as to access the readership it had not been primarily aimed at.Footnote 63 In 1889 a second edition appeared in the new format (fig. 2). The Queen's Land was thus remarketed as a boy's book through publisher intervention even though it had not begun its life cycle this way.

Figure 2. W. Parkinson, “A voice was now heard: ‘Seize the audacious intruder and rend him in pieces!’” Illustration in Cameron, The Queen's Land (1889), 2nd ed, facing page 241. Photograph by Alison Metcalfe. By permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Cameron's effort to write for a more porous audience calls attention to the complex dynamics at work in the novel. In terms of its content and audience positioning, The Queen's Land inevitably invites comparison with the contemporaneous works of H. Rider Haggard and his new model of “romance.” Swan Sonnenschein certainly noted and approved of the resonance. When Cameron first sent the firm a manuscript for their magazine Time, Lowrey suggested that he “work it up into a shilling novel” instead: “Judging from the success of King Solomon's Mines & The Case of Dr Jekyll,” Lowrey told him, “the public taste runs strongly in favour of stories dealing with magic.”Footnote 64 Yet to read The Queen's Land only as an imitation of Haggard would do disservice to Cameron's imbrication of adventure and the supernatural. Although the Solomonic quests and lost worlds of both works are obvious parallels, The Queen's Land is much more esoteric than King Solomon's Mines (1885). In the latter novel, the reality of the supernatural—Gagool's preternatural longevity—is held in abeyance. The more concertedly supernatural enters Haggard with the white queen of She (1886), Ayesha, who possesses the secret to immortality. The publication dates, however, prevent any inference that She might have influenced The Queen's Land. She was published serially in The Graphic between October 1886 and January 1887;Footnote 65 The Queen's Land was published in volume form in December 1886, but Cameron had sent his first draft to the publisher in April of that year, six months before She began to appear in print. Indeed, by early July Cameron had requested proofs and was at work on them the following month.Footnote 66 Since Haggard reportedly drafted She “at white heat” between February and March 1886,Footnote 67 its composition was almost synchronous with Cameron's work on The Queen's Land—and there is no evidence that either author was privy to the other's manuscript.

More pronounced than the similarities with She are resonances between The Queen's Land and the lost-world plot of Allan Quatermain (1887). In that novel, Haggard's adventurers, like Cameron's, are following “rumours of a great white race” thought to reside “in the unknown territories.”Footnote 68 Again, the theory that Allan Quatermain influenced Cameron can be discarded. Allan Quatermain was serialized in Longman's Magazine between January and August 1887,Footnote 69 by which time The Queen's Land had already been released. The alternative possibility that Cameron's work influenced Allan Quatermain is less easily dispensed with. Given Haggard's penchant for reading works of exploration, he may well have kept abreast of Cameron's publications. And it is certainly striking that both these quest narratives, published in proximity, should quote variants of Pliny's proverb that “there was always some new thing coming out of Africa.”Footnote 70 This is no clear evidence that Allan Quatermain borrowed from The Queen's Land, but the possibility of reciprocal influence between Haggard and Cameron should remain an open question.

Given the ambiguities at play, Cameron's Solomonic plot must not be read simply as an imitation of Haggard but as a contributor to a wider trend of lost-race stories in Victorian popular fiction. The idea of a long-lost white tribe dates to at least the fifteenth century and the myth of Prester John, but as Michael F. Robinson has shown, it became the subject of sustained anthropological inquiry in the nineteenth century. As travelers’ reports of white tribes emerged from various parts of the globe, argues Robinson, many scientists concluded that they were connected; anthropological and archaeological records were scrutinized “in hopes of connecting the dots of racial geography to form a picture of the white racial past.”Footnote 71 The swathe of lost white race tales that appeared in the 1880s and ’90s both popularized and intensified these contemporary anthropological preoccupations.

In narrating African travel in the emerging genre of lost-world fiction, Cameron found another way to bolster imperial politics. As Carter Hanson argues, lost-race fictions provided “narratives of imperial permanence” in response to anxieties of “imperial decline.”Footnote 72 On one hand, the “similarity between the British race and a ‘lost’ Other” intimated the endurance of British power; the “historical presence of a lost race” in areas of colonial interest provided a myth “that sanctioned Britain's imperial destiny.” On the other hand, by showcasing differences between the two worlds, these narratives provided “critiques of ‘lost’ societies that reinforced the superiority of British culture.”Footnote 73 Cameron's fiction of a white kingdom in central Africa existing since the days of Solomon can certainly be read as a document of colonial entitlement. The protocivilized kingdom of Saba provides a mythical mandate for white settlement, while the closing stages of the book, in which the trio of adventurers restore legitimate rule, reflect fantasies of the British as ambassadors of order and commerce. The British party provides lessons in judicial restraint and advises that the land should be ruled “by means of justice and mercy,” asserting their influence over the kingdom to the extent that it becomes a spiritual colony (263). And when the queen gives orders for “the frontiers of the kingdom to be thrown open, and people permitted to enter and leave,” the formerly closed kingdom converts to a free-market philosophy (257–58).Footnote 74

More important, however, than Cameron's deployment of the lost-world genre is his recourse to the occult, for the journey into Saba is also one into magical knowledge. Indeed, it is in transposing exploration into esotericism that the novel offers its more surprising intersections with geography and empire. Of central importance is the protagonists’ shared membership in the Freemasons, in which they are all advanced. The book is clearly sympathetic to the Masons, but it also uses the fraternity metaphorically to comment on expeditionary travel. On one level, Freemasonry is important because of the values it imputes to the three travelers. As Jessica Harland-Jacobs has argued, “From its beginnings the institution identified closely with the ideals of Enlightenment cosmopolitanism,” particularly “universal brotherhood.”Footnote 75 In The Queen's Land, a favorable representation of the fraternity confers moral esteem and intensifies the travelers’ fellowship. When Hamees joins the English travelers, they consider that he, “being a mason, is more likely to stick to us” (29). This is confirmed when Hamees gives each of them “the master grip of a mason” and swears fidelity “by the oath that has never been broken” (105). Read as a commentary on exploration, Hamees's ethnicity is vital; he is “the first Arab [Hardy] has ever come across who is” a Freemason (29). As an organization whose stated criterion for membership was belief in a supreme being, and that claimed not to bar access on the grounds of race or class, Freemasonry lends Cameron a model of exploration as intercultural collaboration, albeit one freighted with racial paternalism. Important too is the status of the brotherhood as an imperial organization; since the fraternity established a network of connections across imperial domains, it should be regarded as “central to the building and cohesion of empire.”Footnote 76 The Freemasonry of Cameron's explorers, then, consolidates their identities as imperial travelers whose journey will have implications for empire.

Yet Cameron was not drawn to Freemasonry simply as a respectable imperial institution. It is the suffusion of Masonic mystery and esotericism throughout the book that is most critical to its reflection on geography. With their expertise in Masonry, the explorers operate as masterful decoders able to decipher a web of clues that lead them to Saba. Tom Hardy's motivation for joining Murray is the hope of finding his lost brother, Hugh, who was shipwrecked two decades earlier and is believed to be in the interior. They receive the first clue of his whereabouts in the form of some “‘pieces of hides which have been brought from the coast, on which are some letters’” inscribed by one of the wreck's survivors (19). While others have failed to decode the hides, Murray discovers a message:

I made out several series of dots, which were disposed as follows, in squares round the edges, so as to form a sort of border. Seeing that the numbers were always the same, I puzzled over them for a long time, and at last I said: “I have it. The dot is a thousand, the second hundreds, the third tens, and the last units, and the whole make 1873. Hardy's brother was alive in ’73.” (21)

Following Hamees's advice, they soak the hides to reveal further characters, which they determine are in “a sort of cipher.” Enumerating and organizing the marks reveal a message that confirms Hugh is “far in the interior” and has been sold to a people who allow no one to “leave their country” (38).

If the travelers begin as code crackers, this intensifies when they identify Solomonic traces as they travel. As Masons, they possess special knowledge that allows them to perceive significances in artifacts of which the local peoples are ignorant. Among the “Gallas” they locate an “iron pillar ten feet high [. . .] covered over with symbolical signs.”Footnote 77 While the locals are unaware that “the emblems with which it was covered were decidedly of a masonic character,” they are “full of meaning to Hardy, Hamees, and myself [Murray].” With their Masonic insight, they find a hidden door in the pillar, behind which is “a small parchment packet” containing “a golden key” and writing from “a pupil of Hiram” (125–26). Later in the quest, their understanding of Masonic arcana enables them to locate the tomb of Joash, the “pupil of Hiram the architect [. . .] sent by Solomon,” which contains “documents related to the building of a temple on the model of that at Jerusalem” (166, 262). It is by virtue of their secret knowledge and magical power—for Solomon's signet gives them “power over the genii”—that they successfully complete Joash's mission and bring the tomb's artifacts to the queen (244). In Freemasonry, of course, Solomon and his temple occupy central positions. Guy L. Beck notes that this can be traced back at least as far as 1410 but that it became more pronounced with the development of speculative Freemasonry in the eighteenth century. Indeed, in its well-known origin myth, the fraternity emerged out of the Solomonic period, when Hiram Abiff, the reputed architect of the temple, was murdered “after refusing to reveal Masonic secrets.”Footnote 78 The Queen's Land’s saturation with Masonic lore and magical happenings may suggest that Cameron had interest in these traditions, but on my reading the primary value of the transposition into esotericism is to allegorize the skills and knowledge of geographical travel. At a moment when Africa's last geographical puzzles had lately been settled—the source of the Nile and the course of the Congo—Cameron imagined expeditionary travelers as magical cryptographers.

By analogy, then, the task of the scientific explorer is to decode the terrain with specialist cartographical knowledge that, like the esoteric expertise of the Masonic trio, provides them with a larger picture unavailable to local peoples. We have already seen, moreover, that Cameron tasked the commercial geographer with determining the market potential of natural resources whose economic value may not have been known to the region's inhabitants. If this seems too much like argument by analogy, it is surely important that Murray's primary channel of magical knowledge is his “pocket-book.” It is in the notebook—a key article in any explorer's toolkit—that “the cabalistic numbers” from the rabbi have been recorded. The everyday field diary in which travelers recorded observations is elevated into a magical source of knowledge. And in addition to its “valuable contents,” the pocket-book also becomes the channel of communication with Murray's friend, Trevelyan (191–92). At critical moments, enchanted writing appears in its pages offering reassurance or strategic guidance. In the first instance of chirographic communication, Murray finds his “pocket-book open” on awakening: “on a page which had been blank the night before I saw, in the writing of Trevelyan, ‘To recover Hamees use the numbers of the Rabbi’” (66). The travelers’ mission is dependent on these regular telepathic messages from home. It might be a push too far to read Trevelyan as an “armchair geographer,” the expert who aggregates information at what Latour called the “centre of calculation.”Footnote 79 Yet the transmissions from Trevelyan to Murray stage exploration not as the solo endeavor of travelers but as a project relying on directives from the metropole and on the circulation of knowledge between field and home.

It is important, moreover, that the knowledge the explorers possess is not just specialist but secretive. Some of what they learn during their travels is conspicuously withheld even from the reader. When they discover Masonic emblems, Murray adds an addendum: “the nature of which I am forbidden by the spirit of the craft to disclose” (126). The full details of Joash's tomb are similarly occluded: “Of what we found there it is not lawful to write nor to speak to the uninitiated” (166). At the end of the narrative, the travelers reflect that they may need “to use the power and knowledge which we gained” for the wider good, but this is far from a total revelation of what they have learned (264). Rather, much of their knowledge is occult—typified by the numerology that Murray is instructed to “withhold from all other people”—and therefore to remain hidden (15). In an important respect, the secret nature of the explorers’ findings heightens their status as bearers of expert knowledge, accessible only to an elite coterie. As Hugh Urban has argued, secrecy is “a matter of valued knowledge and contestations over who does and not have access to that information.” It is therefore imbricated with “questions of power” and regularly operates as “a strategy for acquiring, enhancing, preserving and/or protecting power.” Most often, argues Urban, it involves “symbolic power,” for having access to privileged knowledge from which others are excluded “enhances the status and authority” of those who possess it. It is often socially valuable to reveal that one possesses secret information while keeping its content hidden; as Urban puts it, a paradox of secrecy is that “it often displays or publicizes every bit as much as it conceals.”Footnote 80 In The Queen's Land, the Masonic trio engage in just such a display of hidden knowledge, advertising their possession of that which they refuse to disclose. To the extent that occult knowledge allegorizes geography, their commitment to secrecy elevates their status as masters of their field.

Nevertheless, the strange nature of Cameron's geographical allegory must be acknowledged. If the travelers’ esoteric learning equates to scientific expertise, there are tensions in this analogy, for the narrative also sets the travelers’ knowledge against contemporary scientific materialism: the men reflect that they have “seen a world outside that of the matter-of-fact science of the present day” (76). The thematic of secrecy, moreover, sits uneasily beside Cameron's preoccupation with the utility of geography. In contrast to the instrumentalization of useful knowledge that characterizes his commercial geography project, The Queen's Land instead presents knowledge gained in travel that is to remain undisclosed. Indeed, in framing expeditionary travel through traditions, from Masonic craft to kabbalistic mysticism, in which concealment is essential, the novel invites a question: What is it about geographical travel that must be hidden?

Since codes are such an important feature of Cameron's plot, it is tempting to treat the references to secret knowledge as themselves coded allusions. It is well documented that explorers were not always able to freely share their experiences in print; their own reticence or the sensibilities of publishers could prevent transparency on matters that might test genteel standards of politesse. Cameron was a close friend of Richard Burton's, the most celebrated Victorian traveler to show disregard for conventional morality in print. Having first met in 1872, they undertook an expedition to the Gold Coast together in 1881 to survey its goldfields and remained regular correspondents thereafter.Footnote 81 Cameron's letters are convivial and occasionally playful; in one he addresses Burton as “My beloved Hadji,” and in another he signs himself “Your affct [affectionate] bad boy.”Footnote 82 Indeed, in a long obituary for the Fortnightly Review, Cameron presents Burton as a mentor from whom he had “learned much as to the real duties of an explorer.”Footnote 83 There is little doubt that Burton's influence can be traced in The Queen's Land. His abiding interest in the paranormal, including mesmerism, spiritualism, and Eastern mysticism, may have contributed to Cameron's own turn toward esoteric traditions, and the book's genies and magical artifacts, as various reviewers noted, owed something to The Thousand Nights and a Night (1885–86), which Burton famously translated. However, whether Cameron also shared Burton's preoccupation with sexology is uncertain.Footnote 84 He did attempt to defend Burton from accusations of prurience, arguing that the “erotic nature” of his friend's work did not reflect an “impure mind” but the approach of “the pathologist” who must “analyse the impure as well as the pure.”Footnote 85 Is it also clear that Cameron was familiar with works that some contemporaries regarded as obscene,Footnote 86 and on one occasion he sought Burton's opinion on an “erotic poem” composed by a friend.Footnote 87 This is not, of course, sufficient grounds to interpret the secret knowledge of The Queen's Land simply as coded references to sexual matters; to do so would diminish the ambiguity of secrecy and foreclose alternative possibilities. As Urban suggests, the study of secrecy inevitably runs into an epistemological quandary: “how can one even claim with any certainty to know the real content of a secret?”Footnote 88 The Queen's Land’s secrets ultimately evade too clear-cut referential readings; it is enough to argue that Cameron's novel represents travel enigmatically, as the source of experiences that cannot readily be revealed. Indeed, if the novel's esotericism casts explorers as bearers of special expertise, on one hand, it frames them as a coterie sharing in an intensely private knowledge on the other.

Cameron's decision to express dimensions of exploratory travel through magic has a broader implication. Since his recourse to esotericism was not simply derivative, The Queen's Land marks an instance where the effort to renarrate exploration contributed to wider developments in literary culture. This book certainly fed into the resurgence of a gothic aesthetic in late nineteenth-century imperial writing. More precisely, The Queen's Land’s magical allegory of exploration participated in the burgeoning of the “imperial occult” in late Victorian popular fiction.Footnote 89 The book was written in the context of the Occult Revival, which, as Christine Ferguson notes, was “characterized by a flourishing of popular interest [. . .] in forms of knowledge considered to lie beyond the fold of scientific rationalism or contemporary Judeo-Christian orthodoxy,” and by a proliferation of “occult-inflected artistic movements.” It was part of an intensifying occulture, or “diffusion of occult ideas,” outside the context of “earnest belief” in which popular literary culture played a significant role.Footnote 90 Indeed, The Queen's Land should be regarded as an important exemplar of the blend between occult discourse and imperial ideology most often associated with H. Rider Haggard, and which may have anticipated features of the more famous author's work.

Conclusion

The imaginative works of expeditionary travelers, as Cameron's fiction illustrates, present generative source materials for further scholarship on nineteenth-century African exploration. Since the scientific travel narratives that explorers published played an outsize role in documenting African peoples and geographies, and therefore in producing ideas congregating around cultural, racial, and environmental difference, their neglected fictional works merit much closer scrutiny than they have yet received. As texts that both reflected and magnified the public fascination with Africa, they offer new angles on the popularization of geography during the intensive decades of exploration from the mid- to late nineteenth century. The concept of “popularization” has been challenged for the “value-laden” implication that, simplistically, it entails the dissemination or dilution of authoritative scientific knowledge, but it nevertheless draws important attention to distinctions between media. As Richard Fallon points out, following historians of science like Bernard Lightman and Peter Bowler, the term acknowledges “demonstrable differences” between works oriented toward general readers and specialist audiences in the later nineteenth century, even while these boundaries were often porous.Footnote 91 Popularizing, moreover, should not be understood as passive mediation, particularly in a period of proliferating literary forms and new readerships. The fictional forms adopted by nineteenth-century explorers, as shown by Cameron's work, were not simply channels of dissemination but modes of productive reimagination. This owed much to the fact that they operated outside the “official” structures of geography, at a moment in which exploration was becoming increasingly professionalized and regulated by scientific protocols. Crucially, I have argued, it was the relative freedom of representation offered by fiction—since it was not subject to the expectations constraining the reportage of the expeditionary narrative—that afforded the alternative perspectives which now lend these works particular critical interest.

Taking explorer fiction seriously adds complicating layers to the record of exploration that discourage scholars from prioritizing either the “final” expeditionary narrative or the original record composed in the field. In calling attention to the diversity of forms and inscriptive practices associated with exploration, these works suggest that in-field sources are not ineluctably the most revealing materials and that the authoritative travel narrative is not always the end point of an expedition's narrative production. Ultimately, the imaginative writings composed by African travelers compel an extension beyond models of exploration literature that detail the complex literary journey from field notes toward published geographical narrative, to ones that also accommodate the discursive afterlife of expeditions. Explorer fictions, I have argued, are profitably read as sequels that extend and complicate the preoccupations of explorer-authors’ earlier geographical writings. Yet these are sequels in alternative literary forms; explorer fiction involved the re-mediation of expeditionary experience, a formal transposition that could introduce new preoccupations or significant reconceptualization.

Cameron's fiction displays the dynamics of both the sequel and serious transformation. As Herbert Massey illustrates, Cameron repackaged expeditions as boys’ adventures with political objectives. Specifically, his fiction was motivated by the same concerns that underlay his work in commercial geography and chartered companies: the imperative to counteract imperial decline and the ascent of international rivals. For Cameron, private enterprise would provide the practical solution to imperial malaise; his was a distinctively commercial-imperial ideology, in which geographical work would serve commercial ventures, which would then serve British interests. This set of commitments energized his fiction and lent it specific political application in particular contexts. In Herbert Massey, Cameron turned to Zanzibar and the East African hinterland at a moment of precarity, while negotiations between Britain and Germany were ongoing. The book, I argue, construes the region as one best suited to company administration by showcasing political disarray in the Zanzibari dominions and discounting imperial alternatives. By advertising the ivory trade and alternative markets yet to be exploited, the book operates as a sequel to Across Africa that extends its perspectives on East African commercial opportunities.

Cameron's reputation as an author of creative fiction rested on the authority that firsthand witness gave his representations of African geographies. His turn to the supernatural in The Queen's Land is therefore conspicuous in his oeuvre, for it amounts to a major transformation of the source material from which his fiction draws. Certainly, this transposition supports Cameron's imperial project; the lost-world plot stages a fantasy of imperial entitlement, while its esotericism offers an allegory of exploration that valorizes the specialist knowledge of geographical travelers. Yet the transposition is also critically productive, for it poses questions about the very project that it celebrates. In representing geographical travel as the source of occult knowledge, The Queen's Land casts exploration as an elusive enterprise; expeditionary travel results in knowledge that must be concealed. Cameron's unusual book, moreover, calls for further attention to the intersections between exploration and the period's wider literary culture. Nineteenth-century travel writers, argues Murray, “cannibalised other modes of literary, geographical and scientific writing, while simultaneously forging experimental, innovative and dynamic forms in the struggle to represent the contingent realities of the road.”Footnote 92 In my reading, The Queen's Land marks a striking instance in which exploration proved creatively generative. For Cameron's esoteric adventure fed into the imperial occult less by imitating Haggard than by attempting to negotiate the inexpressible experiences of expeditionary travel.