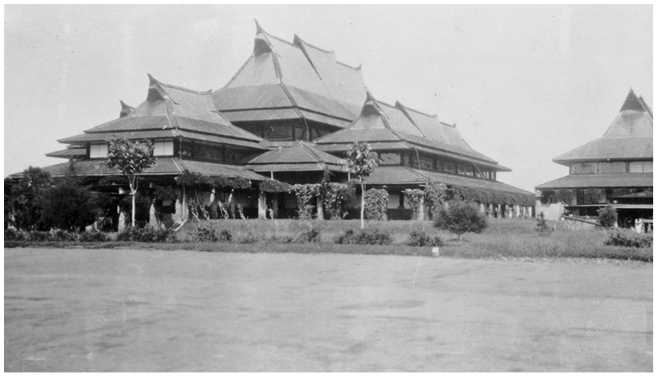

In August 1937, more than 80 delegates from ten “Far Eastern” Asian colonized regions and three independent countries gathered in fashionable and cool Bandung, a new and modern city situated in a mountainous area immediately south of the slopes of the modestly active volcano Tangkuban Perahu (“upturned prau”), visible on the northern skyline on a clear day.Footnote 1 Bandung is a mere 160 kilometers southeast of Batavia (today’s Jakarta), the capital of the Dutch East Indies, and can be reached by a scenic train ride. These delegates, joined by international health experts, assistants and observers including representatives from the Indian Research Fund Association, the League of Red Cross Societies, and the Rockefeller Foundation, long active in international health initiatives – nearly 200 individuals in all – attended the Intergovernmental Conference of Far-Eastern Countries on Rural Hygiene, organized by the League of Nations Health Organization (LNHO). The conference met at the main building of the recently established Technical School, which had a traditional Minangkabau appearance but was built with modern construction methods (Figure 4.1). It was accompanied by an impressive exhibition in the nearby trade fair building (Jaarbeurs).Footnote 2 The local hosts clearly hoped to impress the international visitors by presenting an event as lavish as the Depression era would allow. The postal service even set up a small post office close to the conference site where mail was stamped with “Rural Hygiene Conference” (Figure 4.2). Both Dutch and Malay Dutch East Indies newspapers reported extensively on the conference.

Figure 4.1 The main building of the Technical School in Bandung, erected in the style common among the Minangkabau of Western Sumatra. The meetings were held in this building.

Figure 4.2 An envelope issued for the Bandung Conference with a special postage mark reading, “Rural Hygiene Conference, Bandoeng, Volkenbond [League of Nations].” A small post office was erected near the meeting hall to stamp all outgoing mail. The envelope displays a rat poking its head from a bamboo pole, which refers to the bubonic plague epidemic that had been ravaging Java over the previous twenty years.

According to a Sundanese folktale, the Tangkuban Perahu volcano and the adjacent Bandung basin were created by a local deity who smashed the large prau he had just completed to assuage his anger and disappointment. As a child, he had been banished from the household of his mother, a princess who had been expelled from her parents’ palace, after he had killed a large dog and gave its liver to his mother, who cooked and ate it. Unbeknownst to him, this dog was his own father. When mother and son reunited years later, they failed to recognize each other, fell in love, and planned to marry. Just before the marriage would take place, the princess recognized her son’s birthmark and tried to avert their wedding by setting him an impossible task: to create, overnight, a lake (which later became the Bandung basin) and a large prau to traverse it.Footnote 3 Her plan was successful: her son was utterly disappointed, threw the prau away, and drained the lake. This Sundanese Oedipus had killed his father but did not get to marry his mother.

Several medical historians, global health experts, and international relations specialists have analyzed the legacy of the 1937 Bandung Conference in the areas of international health, social medicine, and primary healthcare. Most view it as a landmark event in the history of international health and a precursor to the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care.Footnote 4 Theodore Brown and Elizabeth Fee, for example, characterize “Bandung” as a “milestone event” in health and development, while Randall Packard views it as the “culmination” of the interest in rural reconstruction and hygiene outside Europe.Footnote 5 According to Iris Borowy, the conference was one of the first major international public health meetings hosting representatives from non-Western regions who challenged the idea that there was one universal model for health.Footnote 6 The highly respected and outspoken Polish bacteriologist and LNHO medical director Dr. Ludwik Rajchman, who gave one of the opening addresses, was probably the first to revisit the meeting. In 1938, he extolled the “Bandung spirit” and argued that it “was probably the first time a governmental conference was able to face the problems of social medicine directly.”Footnote 7 Constructing a genealogy to the Alma Ata conference on Primary Health Care, World Health Organization (WHO) General-Director Halfdan T. Mahler referred to “Bandung” to support his own agenda to replace the organization’s then common techno-centrism and vertical interventions by focusing on decentralizing services, intersectoral collaboration, and community engagement.Footnote 8

Rather than focusing on its legacy, this chapter focuses on the Bandung Conference’s antecedents. We view “Bandung” as a synthetic formulation of various Southeast Asian initiatives, experiments, and experiences in rural hygiene and social medicine, most of which were designed and developed in areas under colonial rule. Experts in the region had already engaged in discussions on health, hygiene, and medical care for almost thirty years, for example at the biennial meetings of the Far Eastern Tropical Medicine Association (FEATM), which was founded in 1908.Footnote 9 Physicians, both European (colonial) and Southeast Asian (colonized), frequently traveled within the region to observe healthcare initiatives.Footnote 10 Through expert networks, meetings, and site visits, physicians and other experts collectively developed expertise in health relevant to Southeast Asia. At the time of the Bandung Conference, several colonial governments had implemented decentralization policies to deal with the economic consequences of the Great Depression. Their health departments followed suit but attempted to make a virtue out of necessity by claiming that health interventions were ideally designed to respond to local conditions and the health needs of rural communities.

The Great Depression hit the region hard, leading to increased poverty, malnutrition, and decreased expenditures on health and medical services. In the 1930s, malaria, famine, and colonial exploitation affected the already poor health of colonized populations, forcefully illustrating the social dimensions of health and well-being. The Depression also fueled political unrest in the region. Nationalist movements, in which indigenous health personnel played significant roles, became increasingly vocal, demanding improvements in healthcare provision for indigenous populations.Footnote 11 Politically, developing health solutions for the mostly rural Southeast Asian populations therefore became more urgent while the funds to implement these plans were scarcer than ever. During the 1930s, health departments aspired to do much more but had to do so with much less. Both factors, political unrest and a lack of meaningful financial resources, inspired the discussions at the Bandung Conference. In this chapter, we explore the meanings of social medicine and rural hygiene in Southeast Asian contexts, where health measures were tied to (colonial) economic objectives, health budgets were limited, and populations mostly rural. We primarily focus on French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies. With 21 delegates, French Indochina (9) and the Dutch East Indies (12), which hosted the event, clearly played a significant part in both organizing and running the conference.

Before “Bandung”: Rural Hygiene and Social Medicine in Southeast Asia

After the First World War, international interest in medical care and public health intensified, initially focusing on preventing the global spread of epidemics. The various colonial empires became increasingly interested in improving the health of colonized populations. These interests motivated the establishment, in 1924, of the League of Nations Health Organization to collect and distribute information, organize international health projects, and advise the League of Nation’s Council. Dr. Rajchman served as its medical director from its inception to 1939. Under his leadership, the LHNO promoted cooperation and exchange between countries through conferences and expert missions. In 1915, the Rockefeller Foundation had established the International Health Board (IHB), directed by physician Victor Heiser, former Director of Health for the Philippines. The IHB funded most of the activities of the LHNO and various health initiatives worldwide. In 1925, the LNHO established an Eastern Bureau in Singapore to collect epidemiological intelligence; at the same time, the IHB started to promote intercolonial cooperation in Asia.Footnote 12 The Far Eastern Association for Tropical Medicine had been established in 1908 to provide physicians, public health, and other experts working in Southeast Asia with opportunities to exchange ideas, share discoveries and the results of local initiatives, and to present a voice to influence health-governing agendas.Footnote 13 These three organizations established and funded a dynamic intercolonial network of physicians working in Southeast Asia, who collectively developed a specifically Southeast Asian body of knowledge and expertise in health, hygiene, and medicine.

In the aftermath of the 1929 economic crisis, the LHNO encouraged further intercolonial cooperation. Colonial public health experts discussed how to improve the health of “rural masses,” and the connections between poverty, malnutrition, and poor health, and came to emphasize the need for social and economic improvement through rural reconstruction.Footnote 14 According to Brimnes, rural hygiene connected health, nutrition, and agriculture to the principles of social medicine by promoting simple, broad, and affordable solutions to health problems such as general sanitation, better housing, improved nutrition, and expanded educational facilities.Footnote 15 Because health was related to several social and economic variables, health experts became increasingly convinced that these variables needed to be addressed as well.

In 1930, the LNHO organized a conference on rural health centers – clinics offering basic medical services – in Budapest.Footnote 16 In July 1931, it held it first rural hygiene conference in Geneva, focusing on Europe, followed by two Pan-African conferences. The first one, held in 1932, called for an integrative approach to curative and preventive interventions and services, and for cooperation among different fields of expertise and departments – agriculture, veterinary services, and education. The second one, held in 1935, recommended that local healthcare infrastructure were staffed with local personnel and emphasized the importance of economic growth for health. In Asia, the League of Nations organized several meetings on “social questions,” including opium control (Bangkok, 1931) and the trafficking of women and children (Bandung, 1937). In the meantime, Heiser, as head of the IHB, started participating in debates taking place in the region and insisted on developing closer ties between the LNHO and FEATM.Footnote 17 At successive meetings of the FEATM, ecological approaches to malaria eradication, nutrition and deficiency diseases such as beriberi, and “social diseases” (i.e., pathologies that were related to living conditions and social behavior such as sexually transmitted diseases, leprosy, cancer, or addictions) were discussed. These health issues and social medicine were already at the core of colonial healthcare policies in the region.

In both French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies, various initiatives in social medicine and rural hygiene had been discussed for some time and some initiatives already been undertaken at the time of the Bandung Conference. The health services of both colonies had hired an increasing number of indigenous physicians to staff rural services. In both regions, there was also some discussion about the potential role of traditional medicine and traditional practitioners while nationalist movements were becoming increasingly active.

Health in the Colonies and the Indigenization of Colonial Medical Services

To address health and disease among indigenous populations in the French Empire, the Assistance Médicale Indigène (Native Medical Assistance, AMI) was founded in Madagascar in 1899 as part of France’s mission civilisatrice, inducing colonized populations to accept Western civilization through medicine. AMI was established in French Indochina in 1905 and focused primarily, with the help of a medical (mostly military at the time) corps, on public health – sanitation and the prevention and control of epidemic diseases – rather than medical care. It organized (smallpox) mass immunization programs and various vertical initiatives targeting one pathogen at a time. From the outset, it faced the challenge of managing pathological environments characterized by a volatile combination of high morbidity and mortality rates, especially in infants and children. Despite the civilizing rhetoric and the insistence on free care, colonial medical initiatives in Indochina remained minimal and focused on the large urban centers, where sanitation was improving and a network of medical facilities had been established. In rural areas, a modest number of medical outposts, first-aid posts, infirmaries, and maternity clinics had been established but their numbers were grossly insufficient and chronically understaffed. Life-threatening epidemic and endemic diseases continued to be omnipresent. Although the challenges were enormous, the AMI received a modest and inconsistent budget from the French Government-general in Hanoi. It was impossible to combat malaria with strictly biomedical measures, as complex local environmental variables, economic exploitation, the plantation economy, forest clearing, and increased human mobility all played a role. Effective measures, such as general sanitation, better housing, and improved nutrition were, unfortunately, expensive. From the very beginning, AMI officials were facing tremendous challenges which they were supposed to attack while they were supported with minimal and ever dwindling resources.

After the First World War, AMI resources increased in the context of the French mise en valeur (“colonial development” or “improvement”) policy,Footnote 18 and more Vietnamese personnel – auxiliary doctors and nurses were cheaper than European physicians and considered closer to the indigenous population – were hired. New investments in maternal and child health led to the creation of maternity wards, specialized consultation services, and milk stations and the training of midwives. Attention to rural needs was growing among Vietnamese auxiliary doctors trained at the Indochina Medical College (since 1902) who were generally sent to the countryside. In 1926, one of them, Henri Marcel, strongly criticized the growing gap in health services between Tonkin (Northern Vietnam) provinces, the major urban centers, and “the rest.”Footnote 19 The French local director of health in Cochinchina (Southern Vietnam), Dr. A. Lecomte, admitted that rural hygiene had thus far been neglected and announced several new initiatives, such as the creation of a body of “hygiene agents” who, after a brief education, would be able to detect cases of contagious diseases, and of mobile teams of health professionals who would assist bringing clean drinking water everywhere, and ensure the cleanliness of public places, schools, and homes. This “applied hygiene” would require legislative tools and be under the control of “local hygiene committees” (made of French civil servants: medical doctors, public works engineers, policemen). Rural hygiene, according to the director, was vertical in nature and costly; it would not take local specificities, needs, or social practices into consideration.Footnote 20

As maternal and child health was nevertheless improving (neonatal tetanus, for instance, vanished from the hospital statistics in the 1920sFootnote 21), in 1927, the AMI launched a “program of rural assistance” (Programme d’Assistance Rurale), providing basic medications to rural populations and disseminating small outposts staffed primarily by indigenous physicians, nurses, and midwives. It emphasized close cooperation between administrative services – departments of public works, education, agriculture, and, of course, health – but remained biomedical, vertical, and centralized. One of its most interesting initiatives was the “re-education” of traditional birth attendants (Ba mu). The two Western-style midwifery training schools that had opened in the 1900s had never attracted many students. Now, traditional birth attendants received a six-month training at the maternity hospital closest to their village of origin after which they were sent back to their community, which was expected to pay their salaries, at least in part. Their role in childbirth was initially strictly codified: they were only meant to attend normal deliveries and refer risky pregnancies and deliveries to the nearest doctor and hospital. Nevertheless, their duties quickly expanded “on the ground” to include a variety of maternal and childcare services, such as vaccinations, eye care, emergency first aid, and even monitoring daycare facilities.Footnote 22

In 1901, the Dutch Queen announced the Ethical Policy, a new approach to its colonies. Instead of viewing them as a source of financial gain for the Dutch Treasury or private initiative, the Dutch government now accepted the ethical responsibility to guide the further development of indigenous populations to higher levels of welfare.Footnote 23 The Ethical Policy inspired new initiatives in public health and medical care, which started including the Indonesian population. Various new medical initiatives were announced but insufficiently funded. Previously, the colonial administration had maintained a military health service; the health and medical care of the indigenous fell outside its remit, except in the prevention and management of epidemics. The extensive smallpox inoculation campaigns, initiated in the 1830s, probably constitute one of the few health initiatives that reduced mortality among Indonesians.Footnote 24

Medical care and public health initiatives for Indonesians were primarily provided through private initiative – plantations, sugar factories, and mines – or through various Protestant (Zending) and Catholic (Missie) missionary initiatives. After the turn of the twentieth century, the immensely profitable tobacco plantations in the Deli area surrounding Medan (North Sumatra) pioneered public health initiatives to increase labor vitality and longevity, supported by several hospitals and a medical laboratory.Footnote 25 An evaluation of these initiatives in 1909 indicated that mortality rates had dropped markedly – from 60 to 0.95 per 1,000 per year.Footnote 26 While the colonies had been “off limits” for missionary activity so as not to antagonize the mostly Muslim population, they started to become active in healthcare at the same time, after colonial officials realized that they were willing to establish much needed schools and hospitals (thereby fulfilling the Ethical Policy “on the cheap”). Protestant and Catholic organizations soon built hospitals, clinics, and other health facilities, which became their modus operandi as the population preferred them over preaching and attempts at conversion. The first missionary hospital was established in Mojowarno (near Surabaya) in 1894 and had a stellar reputation. The extensive Petronella Hospital in Yogyakarta, operated by the Gereformeerde Church (Calvinist) and headed by Dr. J. Offringa, was often cited as an example of the benefits of denominational initiatives in the Dutch East Indies.

The Civil Medical Service, established in 1911, operated a limited number of medical services. It preferred to subsidize the health initiatives undertaken by private initiative and missionary groups, either by offering the services of Indies physicians (graduates of the Batavia Medical College (founded in 1851) and the Surabaya Medical College (founded in 1913), providing medical equipment, or through grants. It also offered salary supplements to physicians practicing in rural areas, which required them to provide medical services to the indigenous population for free. The obligations these physicians had half-heartedly accepted to supplement their meager income grew exponentially with the aim of providing more medical services, leading to much unhappiness among them. Semarang’s city physician, W. T. de Vogel, campaigned to transform the colonial medical service into a colonial public health service, which would relinquish physicians of providing ever more medical services.Footnote 27 As city physician in Semarang, he had successfully implemented malaria prevention programs, the provision of fresh drinking water, a sewage system, and kampung (indigenous neighborhood) improvement programs. According to him, the Civil Medical Service should focus its efforts on public health, leaving medical care to private initiative. De Vogel was promptly appointed as head of the Civil Medical Service; initially, he tasked with addressing Java’s plague epidemic. He initiated a widespread (and expensive) program of housing improvement, as the rats that spread the plague were fond of living in the bamboo poles which Indonesians used to build their houses.Footnote 28 In 1925, the Civil Medical Service was transformed into the Public Health Service. Offringa – even though he was a “hospital man” and knew little about public health – became its head.

The Great Depression and Rural Hygiene in Southeast Asia

The Great Depression hit colonial economies hard. According to some studies, 12.8 percent of the peasantry in the Red River Delta, Northern Vietnam (8 million people) suffered from severe malnutrition in the mid-1930s; despite efforts at double cropping, food often ran out only two months after harvest,Footnote 29 while the price of rice dropped rapidly. The colony’s allocation to health and sanitation dropped as well, from 10,034,000 piasters in 1931 to 6,935,000 in 1935.Footnote 30 Poverty, overpopulation, and famine fostered the radicalization of nationalist and anti-colonial sentiment – the Indochinese Communist Party, established in 1930, became very popular among peasants. More than ever, providing basic medical care in the countryside became politically imperative.

Budgetary and personnel challenges became unusually pressing, especially in Annam (Central Vietnam), the most rural area of Vietnam and the cradle of the opposition to French rule in the late nineteenth century. Annam’s facilities consisted of small medical posts and dispensaries lined up along the coast and a few hospitals concentrated in the cities. Medical officers often complained about the lack of resources and personnel in the region, which made it virtually impossible to send nurses on tours or maintain daily consultation services. In 1932, Dr. Pierre Chesneau, who had been a military physician before joining the AMI and had worked extensively in Annam from the early 1920s, estimated that the average medical facility in Annam only served an “attraction perimeter” of maximum 10 kilometers, unless it was located close to a market or in areas where malaria was prevalent.Footnote 31 He recommended that rural infirmaries be strategically located and that medical tours not only distribute basic medications but also educated locals about available services. He emphasized that malaria was still the prime cause of child mortality in the region, particularly when associated with overcrowding, malnutrition, and comorbidities. Posted in the province of Thanh Hoa for a couple of years, he reported on fertility issues in women and strongly advocated for “rural midwives” and regular screening for trachoma, a prevalent social disease often leading to blindness, in local schools.Footnote 32

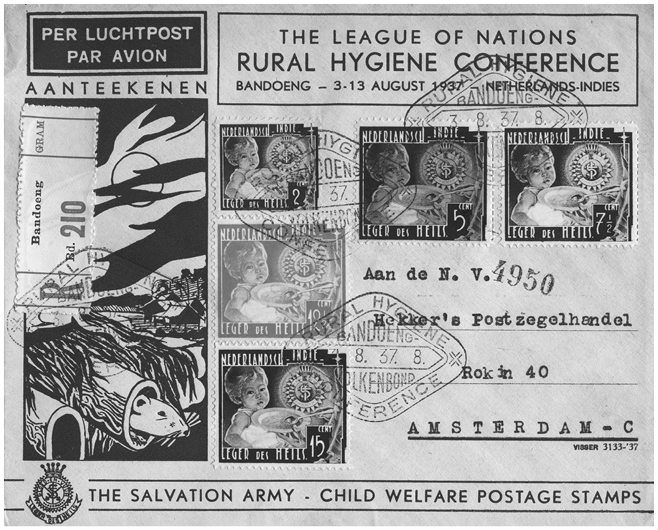

In 1937, a rural assistance program specifically designed for Annam was launched. Chesneau’s “rural assistance” and “social medicine” work in Thanh Hoa had already received praise for increasing the local population’s trust in what the AMI, biomedicine, and French physicians had to offer.Footnote 33 The program divided Annam into twenty-two “sectors,” which were further divided into “health itineraries” (itinéraires sanitaires) by grouping ten to fifteen villages together, established after consultation with local authorities. Both decentralization and mobility were key. Re-educated Ba mu were to be trained and hired locally; villages were to be regularly visited by rural nurses who would screen for diseases, provide emergency care and hygiene advice, and draw a health sheet (fiche sanitaire) for each village.Footnote 34 The sheets were to be transmitted to sectors’ doctors who would check on the sick monthly, send the most serious cases to the provincial hospital (conditions were identified by index cards to facilitate triage), and educate audiences in “basic hygiene principles” (Figure 4.3). This approach was still top-down and biomedical in nature; health promotion initiatives were limited. Although food hygiene and fresh drinking water were considered important, scarce resources continued to limit attention to the “most devastating (epidemic) diseases” for which education and vaccinations to prevent them were prioritized.Footnote 35

Figure 4.3 Index cards used to facilitate triage by the medical doctor in charge of a health sector, Thanh Hoa Province (Annam), 1937. The cards show the local prevalence of eye infections.

By late 1938, only three sectors were functional because of a shortage of personnel; most villages could not afford to hire Ba mu.Footnote 36 Appeals were made to private charities and the Red Cross to help run facilities and to traditional healers and druggists to “reach the rural masses.”Footnote 37 Health authorities had to admit that money remained exceedingly tight, requiring pragmatism everywhere, beyond Annam. In addition, “tolerating traditional medicine,” General Inspector for health services in Indochina Dr. Pierre Hermant (whose own work on malaria prevention and knowledge of rural health issues in Indochina was extensive) argued in 1937, “was not only a moral and political obligation … it was also a material imperative” to ensure that the 25,000 villages of Indochina receive minimal care.Footnote 38 Involving traditional healers was not necessarily a first step toward integrating Sino-Vietnamese medicine within the colonial healthcare system. At the time of the Bandung Conference, traditional medicine was nevertheless in the process of being defined as a second-class medical system, complementary to biomedicine or, rather, an alternative to it in rural areas where resources were particularly scarce.Footnote 39

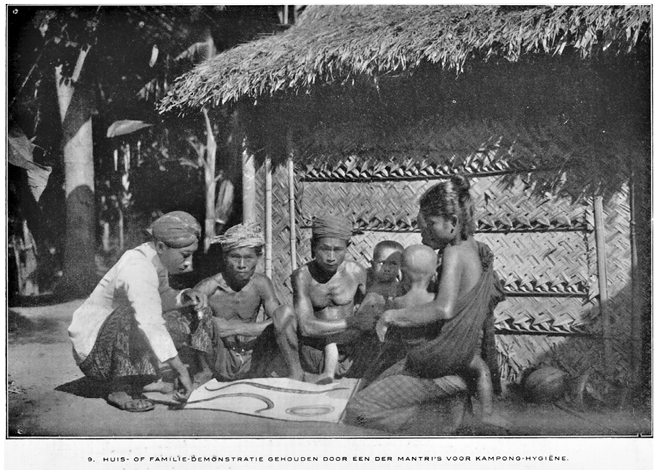

Until 1925, the economy of the Dutch East Indies was in good shape. The colonial administration modestly supported various initiatives in health and education, although it preferred that they were established and run by others. After 1925, colonial profits and tax revenue started declining; after 1929, severe budget cuts were implemented. In the 1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation had sent J. L. Hydrick to the Indies to establish demonstration projects in rural hygiene in the Banyumas (Central Java) area. Instead of relying on technology-intensive hospitals in major urban centers, these projects established modest clinics in rural areas and ran extensive public health education campaigns (Figure 4.4).Footnote 40 Their overarching motive was to provide effective forms of medical care that were within the means of the indigenous population – in other words, they had to be very cheap. Hydrick often waxed lyrical about how villagers under his guidance made toothbrushes and other cleaning utensils from coconut hulls, twigs, and different materials. Initially, the Dutch had not appreciated the interference of an American in their hygienic affairs; the Public Health Services either ignored Hydrick’s work or were obstructive.Footnote 41 After the economic situation darkened, however, it warmed to his ideas as they indicated how health could be purchased at bargain-basement prices. Offringa, the head of the Public Health Service, now saw Hydrick’s program – a combination of public health education, public health measures, and local health centers – as key to the decentralization of health services and reducing health expenditures. Indonesian physicians had embraced Hydrick’s work with great enthusiasm from the outset. Abdul Rasyid, a physician, politician, member of the colonial parliament, and, after 1938, president of the Indonesian Association of Physicians, viewed it as an example of how health and medicine could be organized to meet the needs of average Indonesian and modeled his ideas on medical nationalism on Hydrick’s work. For the same reason, he embraced traditional herbal medicine as Indonesia’s own medicine: it was cheap, its ingredients were available everywhere, and it was one of Indonesia’s own products.Footnote 42

Figure 4.4 A mantri (health worker) educates a family about the intricacies of hygiene (in this case hookworm) at their home. Instructions for home visits stipulated the hygiene mantris would squat at the same level as the families they visited, indicating equality.

Another expert in economizing health expenditures was psychiatrist W. F. Theunissen, a prominent psychiatrist not known for his research but for his organizational skills in managing large mental hospitals at minimal cost.Footnote 43 In 1917, he published a programmatic article on the current state and future development of healthcare provisions for the (indigenous) insane.Footnote 44 As demand would always expected to exceed supply, Theunissen argued that more much needed beds could become available when expenses per bed were reduced, which could be achieved by building and running institutions as cheaply as possible and by increasing revenue. Unlike the first and very expensive modern mental hospital in the Indies, located near Buitenzorg (Bogor), pavilions at the Magelang and Lawang mental hospitals, where only Indonesian patients were institutionalized, were not built with bricks and mortar but with much cheaper bamboo. Theunissen argued that these pavilions were much more comfortable for Indonesian patients because they resembled the housing of the indigenous population. He also advocated occupational therapy because it enabled patients to learn skills that would enable to earn their living upon discharge as well for its potential to reduce the cost of running asylums. Housing patients with their families living near mental hospitals also promised to reduce expenses. Similar initiatives had been undertaken with leprosy patients.

Once economic problems increased in the colonies, Theunissen expanded occupational therapy in the large agricultural colonies surrounding mental hospitals by introducing several new crops, fishponds, and orchards. After purchasing machinery to process rice, the hospital sold the surplus. Cattle, chicken, and duck farms were established, in addition to large vegetable gardens and small plots for the cultivation of tobacco and sugar cane. Kapok trees, which produce material to fill mattresses and pillows, were planted. Theunissen also introduced cotton plants. In 1935, the Lawang asylum was able to sell large quantities of surplus food. Patients also made and repaired furniture and buildings. Female patients worked in batik workshops and products were either sold or used by patients. Patients made mats from coconut fiber to sleep on. Almost everything used and consumed at the asylum, a journalist noted, had been grown, produced, or manufactured there.Footnote 45 Occupational therapy motivated patients to work to improve their own condition and had a salubrious healing effect. It also reduced expenses significantly. Theunissen also introduced new residences for psychiatric patients who could no longer benefit from treatment; they were housed more cheaply elsewhere. These patients were placed in simple housing, built by patients themselves, on the slopes of Bromo volcano and tended crops with minimal supervision. Even though these initiatives are not strictly speaking social medicine, they reduced expenditures by transforming care provided in large institutions into initiatives resembling village care. His accomplishments – activating patients to contribute to their own care – did not go unnoticed and became central in later health initiatives.

In 1935, Theunissen was appointed acting head of the Public Health Service and became head in 1938. While holding the first position, he was tasked with preparing the Bandung Conference as the head of the Dutch delegation. He and other medical experts from the Dutch East Indies and French Indochina actively participated at the 1937 conference, preparing and attending it because of their experience with rural health initiatives that had become more pressing after the onset of the Great Depression.

Preparing and Attending the Bandung Conference

To prepare for the conference, the LHNO proposed to establish a small preparatory committee to make site visits all over South and Southeast Asia to consult with local health officials, visit medical institutions, and observe initiatives in public health and social medicine. Coordination problems and chronic medical staff shortages in all participating countries made it difficult to appoint expert rapporteurs who could dedicate their time to prepare the meeting, which was consequently postponed.Footnote 46 While the preparatory work was enormous, it was done carefully. The LNHO appointed A. S. Haynes, former colonial secretary of the Federated Malay States; Professor C. D. de Langen, former dean of the Batavia Medical School; and Dr. E. J. Pampana, Secretary of the Malaria Commission of the Health section of the League of Nations secretariat to the preparatory committee. These three men toured South and Southeast Asia (bypassing China and Japan) from April to August 1936. They met colonial health administrators and officers of the Rockefeller Foundation IHB and consulted local public health staff. Based on these surveys, the final conference program had five main topics: health and medical services; rural reconstruction and collaboration of the population; sanitation and sanitary engineering; nutrition; and measures for combatting specific diseases in rural districts. Preparatory reports on each of these topics were prepared by physicians appointed by the organizing committee. The report of the preparatory committee was made available before the start of the conference.Footnote 47 In addition, every participating country was asked to name delegates and to submit a national report addressing these five issues. Reports included surveys, elaborate descriptions, and photos of local rural hygiene initiatives.Footnote 48 Most of the delegates to the Bandung Conference had spent long periods in Asian colonies and were intimately familiar with health and medical conditions there. They had extensive experience in matters related to rural health.

Most delegates from French Indochina (six out of nine) were health professionals and had been associated with the AMI for years. Dr. Pierre-Marie Dorolle, the delegation’s vice president, had accompanied the preparatory mission during their visit to Indochina in June 1936 and co-wrote the preparatory report on Health and Medical Services. Starting in 1925, he had built a career in Vietnam and became involved in the LNHO and the Eastern Bureau by participating in several international missions. He was first active in malaria prevention and was concerned with accessibility issues – he had observed that the high price of quinine restricted its impact.Footnote 49 In 1933, he specialized in psychiatry and was put in charge of the most important local asylum, the Bien Hoa asylum. He had visited the Dutch East Indies to explore more affordable options for housing psychiatric patients.Footnote 50 Dorolle was accompanied by Dr. Chesneau, who had co-authored the preparatory report on rural reconstruction, Dr. Henry G. S. Morin, a famous malaria expert interested in the prevention, treatment, and ecology of malaria in rural Southeast Asia,Footnote 51 Professor Henri Galliard from the Faculty of medicine in Hanoi, and Tran Van Thin, an AMI physician. They were joined by Marcel Autret, a military pharmacist who specialized in potable water in rural centers; he was also interested in nutritional deficiencies as well as quinine fraud and traditional herbal remedies.Footnote 52

The delegation from the Dutch East Indies was headed by Theunissen. The Dutch East Indies were eager to show off their psychiatric services, the most extensive in Asia, at the conference.Footnote 53 He was joined by Professor J. E. Dinger, director of Batavia’s Institute of Hygiene and Bacteriology and member of the preparatory committee on Nutrition; Professor W. F. Donath of the Batavia Medical School, a specialist on diet and nutrition; Dr. J. G. Overbeek, director of the malaria control services, and M. S. W. de Wolff, head of the West Java Health Service. Hydrick (who chaired the Health and Medical Services preparatory committee) was joined by his associate Arifin gelar Sutan Saidi Maharaja, an aristocrat from Sumatra’s Minangkabau area and Head of the Division of Medical and Hygiene propaganda of the Public Health Service, and, for several years, member of the Volksraad, the colonial parliament.Footnote 54 Hydrick also was a member of the preparatory commission on rural reconstruction.

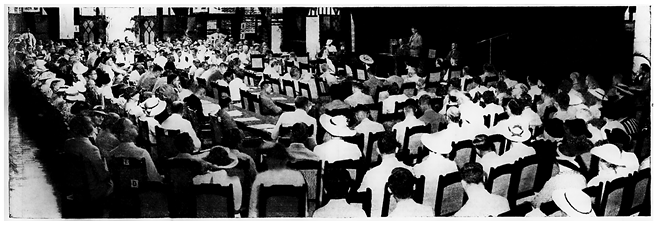

Dr. Offringa, the head of the Dutch Indies Public Health Service, presided over the Bandung Conference while the leaders of each delegation served as vice presidents (Figure 4.5). The purpose of the meeting was to propose measures that could improve the health of indigenous populations in Asia, over 90 percent of whom lived in rural areas which could be implemented with severely limited funds. Building hospitals and clinics, as was commonly done in the urban centers in Asia’s colonies, was neither feasible not useful in Southeast Asia’s vast rural areas. Novel and innovative approaches were needed; fortunately, several promising experiments had already been conducted in the region. In the midst of the Great Depression, health interventions had to be effective as well as affordable. Discussions therefore focused on prevention, public health, hygiene, and health promotion – rather than individualized and curative approaches. Central were mosquitos, sanitation, water supply, sewers, waste disposal, and vaccinations, but also agricultural improvements, education, and establishing farming cooperatives. Social medicine was heralded as the “only possible system in these countries that are still poor,” and hence not particularly relevant in Europe and North America.Footnote 55 To improve the health of rural populations, delegates argued that more than medicine was needed: improvements in agriculture, credit provision, and education were needed, as well as cooperatives and representative bodies, all of which were placed under the heading “rural reconstruction.” To realize change, intersectoral collaboration was necessary, as well as an intensive focus on specific and local health conditions.

Figure 4.5 Name badge for the delegates to the Bandung Conference.

From its inception, it was obvious that the Bandung Conference was a conference on colonial public health and social medicine. Virtually all conference attendees originated from Europe and North America and had spent a considerable time of their careers in Asia working within the colonial health services; many of them had developed expertise on social diseases broadly defined (from malaria and trachoma to mental health issues) and experience with rural health issues (accessibility to medical personnel, facilities, essential medicines). Even though there were a small number of Asian participants, they hardly played a meaningful role. All public health initiatives discussed at the meeting were organized and implemented by colonial physicians, at times with the assistance of their local colleagues working under their guidance and direction. Only a few colonized and Asian people present at the meeting were participants, most Indonesians were there as spectacle.Footnote 56 The most striking absence at the conference were physicians and experts from the Philippines: the American colony only sent one representative. In 1935, the Philippines had been granted Commonwealth status by the United States with the expectation that it would gain full independence in ten years. Its health services were already almost exclusively staffed by locals and many initiatives in rural health developed there were exemplary. Medical professionals from the Philippines might not have been interested in attending a meeting where the white man abounded on the health needs specific to the region.

The most interesting part of the conference dealt with rural reconstruction. Delegates assumed that the health problems among indigenous populations in the region had worsened as an effect of the Depression. Health experts therefore had to pay attention to social and economic factors affecting these populations beyond a fixed list of social diseases and how they could be addressed. Improvements in health, they agreed, would be the outcome of rural reconstruction, which included the introduction of innovative agricultural practices, the establishment of farming cooperatives and representative bodies, education, and cooperation. Yet the most difficult obstacle in realizing this was the difficulty in motivating the indigenous population to improve its own fate along indicated lines. Rural health in Southeast Asia was about implementing community health initiatives but the roles the members of the community itself could play were reduced to a minimum.

Traditional medicines were mentioned at the conference but did not attract much attention. Involving re-educated birth attendants, traditional healers, indigenous pharmacists, and local remedies was merely instrumental to reduce expenses and, probably, to create the appearance of doing something. The need for accessible and affordable medical care was clear at a time of growing anti-colonial sentiment in Southeast Asia. In the 1930s, several Western-trained Vietnamese and Indonesian physicians were discussing the “right to health,” claiming that indigenous populations needed accessible and cheap medications. Several came to advocate pluralistic therapeutic practices and even self-medication.Footnote 57

The “native” did not understand what we colonial health experts were up to and was passive and inert, Offringa, the president of the conference, opined in his opening address (Figure 4.6). He heralded the “Victory March of Western Medicine” and bemoaned the lack of understanding of indigenous populations of hygienic measures for their own benefit. Too often, he stated, prejudice and ignorance, stemming from a different psychological orientation among local populations, resulted in most health initiatives remaining fruitless.Footnote 58 As the final conference report states:

no remedy or plan of work however well conceived or well intentioned can effect the desired changes and improvements for the well-being and happiness of the rural population unless there is genuine desire on the part of the people in the rural areas to accept them and voluntarily work for them. No legislation, no efforts can help those who are not determined to help themselves. The problem becomes thus fundamentally psychological.Footnote 59

When the delegates pondered “enrolling the local people themselves to co-operate in the task of their own improvement,” the locals could have been suspicious and interpreted this as an attempt to reduce services and cut spending by transferring them from the colonial state to colonial subjects.Footnote 60 The proposed interventions, although intersectoral and holistic, were still fundamentally vertical, biomedical, and colonial in nature, as state-driven intervention toward a “civil society” that had local needs into account.

Figure 4.6 The opening ceremony of the Bandung Conference on August 3, 1937.

Needless to say, when indigenous populations were characterized by apathy, ignorance, and lack of initiative, the realization of the high ambitions of the conference necessarily remained unattainable. If the problem was both “psychological” and intractable, all possible health interventions would come to nothing. Fortunately, the attendees were much more comfortable discussing the last topic of the conference: specific diseases – malaria, plague, ancylostomiasis, and tuberculosis. They were, as it were, on “home” ground. The emphasis on individual diseases and their prevention (BCG vaccinations were discussed at length in the French Indochina preparatory report) resembled earlier vertical approaches and interests in infectious disease, despite the holistic emphasis of the conference.

Conclusions

In Southeast Asia, interest in social medicine and rural hygiene become pronounced in the 1930s as it promised to deliver substantial health improvements at a fraction of the price of curative medical initiatives. Rural hygiene included the provision of basic medical care for the masses, and cheap creative solutions for ever-increasing health problems. (It appears that the health of city-dwelling indigenous populations was not considered similarly pressing, as most participants agreed that urban centers had ample medical institutions, making innovative approaches such as those proposed for rural areas appear unnecessary.) The delegates to the Bandung Conference, in particular those from French Indochina and the Dutch East indies, had been familiar with debates on rural hygiene and had been involved in implementing such initiatives for at least two decades. The conference allowed them to showcase their initiatives and formulate a synthetic statement based on their experiences.

We have situated “Bandung” in the context of imperial medicine and the Great Depression to provide a genealogy of its proposals in social medicine as the combination of political pressure to do something about the health of the rural masses with an exceedingly small budget. This complicates other assessments that have heralded it as a precursor for later initiatives in primary healthcare. We assume that, in general, large international events accompanied with ample press which are presented as ultimate “landmarks” or point of departure for global health transformation are best analyzed based on what happened before (their genealogy) rather than what happened after (their legacy).

The delegates at the conference proposed highly idealistic programs that could not possibly be realized. Consequently, all lofty plans turned into a mirage that symbolically absolved colonial administrations from their responsibility to safeguard their subject’s health. This somewhat negative conclusion contrasts with the more positive appraisals the Bandung Conference has received from historians and health professionals previously. Iris Borowy, for example, has asserted that the Bandung Conference “may have been one of the first, if not indeed the first, major international event in public health in which Asian voices were heard” and that it “helped challenge the idea of a universal Western model for world health.”Footnote 61 Borowy is correct that the delegates at the conference continuously emphasized the local and the specific and that health measures needed to be tailor-made for specific contexts. They consequently argued that solutions that appeared feasible in Europe could not simply be transplanted to the “Far East.” The colonial health experts gathered at the conference continuously emphasized specific local factors related to climate, agricultural conditions, and socioeconomic factors. Conservative views that had been common among colonial physicians, emphasizing the primitive and backward nature of the “natives,” had mostly disappeared – the specificity of the “East” lay in socioeconomic factors, not in racial ones. Yet the “Asian voices” she refers to were almost all the voices of Western health experts working in Southeast Asia, as indigenous voices were mostly either silent or absent. The indigenous-looking building where the meeting took place – erected with the most advanced Western engineering techniques and sporting the appearance of a Minangkabau dwelling, an ethnic group residing 2,000 kilometers westward on the island of Sumatra, best symbolizes the Asian involvement at the conference – its appearance was local but its essence Western.

The proposals for public health measures and medical services ventured at the conference were primarily motivated by economic and political pressures. Colonial physicians remained in charge of designing and implementing programs. Delegates viewed increasing the number of indigenous auxiliary health personnel as fundamental, while the re-education of traditional birth attendants and research in traditional medicine were pragmatic propositions – and most probably added some exotic flourishes to the discussions. The proposals discussed at the meeting went beyond earlier vertical approaches, which had viewed natives as primitive, undeveloped, and apathetic, indicating that change had to be brought about by force and compulsion. Instead, indigenous populations were invited to participate in health initiatives led by indigenous physicians while designing these programs remained in the hands of biomedically trained colonial physicians. According to Packard, the Bandung Conference reflected the continued entanglement of international health organizations, colonial medicine, and rural hygiene was mainly an issue of colonial governance.Footnote 62 We agree with this assessment: social medicine at Bandung was a tool for colonial governmentality at a time when colonial empires were contested and weakened.

Progressive voices had discussed a type of colonialism that disdained compulsion and the use of force and, instead, recognized individual or community agency when it came to health. The colonialism on display at the Bandung Conference was empathic and reasonable, suffused with a moralistic and paternalistic feelings. It was an example of empire by persuasion, education, and argument, of necessity guided by the best interests of its subject population and ample attention to its specific and crucial needs at a time of global economic turmoil. Unfortunately, despite the best of intentions, health professionals often reported that their attempts were thwarted by indigenous misunderstanding, irrational prejudice, and obstruction. The conference’s high ideals soon became an upturned boat as it caught in the floods of the Great Depression and Japan’s military expansion – the lack of indigenous appreciation for colonial health initiatives had little to do with it. The somewhat Oedipal motives inspiring it – the caring and morally infused feelings cherished by Western physicians for indigenous populations – could not hide that they were projecting their own image on those silenced Others. After independence, however, Southeast Asian physicians continued to be inspired by these programs and were successful in implementing them as they viewed rural hygiene initiatives as essential components in nation-building.