1 Introduction: An Experiment in Learning – and Teaching – Early Global Literatures and Cultures

Anyone who has contemplated teaching a course on the literatures and cultures of the early global world has surely known a mix of emotions.

At first blush comes excitement and curiosity, perhaps a sense of mission. Teaching of this kind, after all, is still in its experimental stages, its infancy, and it is exciting to join a community committed to trying something intellectually new. But it must be said, this kind of teaching is also fraught with risk and the possibility of error. We are forced to confront the limitations of our training, our life experiences, our knowledge, and, frankly, our nerve. Part and parcel of the mix of responses is surely a degree of intimidation and anxiety, perhaps even a little fear.

But if you are reading this, you are likely someone drawn to the idea of continual self-learning, which teaching of this kind will ensure. Very probably, you see learning and teaching as mutually sustaining, conjoined processes, with that twinning being highly desirable. Already the first reward has arrived: You will acquire life-long learning far beyond anything your disciplinary training prepared you for, and you will never be bored. The teaching process, in the first instance, is then a learning process, as you and your students traverse the terra incognita of the global literature classroom together.

So, you accept, from the start, that no single person can be a thorough expert in the field of early global literatures and cultures – a specialist in all the literary and cultural texts and contexts that would be desirable to encounter, with students, in a classroom, whether of a brick-and-mortar kind or a virtual kind.Footnote 1 With that humbling recognition comes possibility: You will attempt to learn as much as you can, whenever you can, for the rest of your pedagogical life.

In researching an early global world, I’ve said in lectures and publications, collaboration is key: because you are not going to master within a single lifetime the spectrum of languages, knowledges, and disciplinary expertise you will need for global research.Footnote 2 In teaching, however, unless you are extraordinarily fortunate to be at an institution that welcomes and facilitates multi-instructor, collaborative teaching, you’ll likely find yourself facing a classroom of students alone.

If we let the impossibility of full knowledge of our subject daunt us, we should stop here. When anxiety and intimidation remain the dominant emotions, we are likely never to accomplish a course on early global literatures.Footnote 3 For one, unlike world literature courses, there isn’t a plethora of road maps and guides for solo-teaching of the literatures and cultures of the early global world. And there are certainly no Norton anthologies to serve as ballast for our syllabi.

This, in part, is because global literature is not the same thing as world literature (for which there are several Norton editions), though there are, of course, some convergences among texts. World literature courses tend to collect a miscellany of texts to represent the many cultures and localities of the world: to offer a snapshot of the world’s literary creations in the form of best practices. Disparate texts can be plucked from many countries, many eras – sometimes across millennia – each of which serves to represent a place, a people, or a culture; an era, a style, a genre; or a particular type of author or society. The instructor must then find a way to stitch together some kind of course coherence – perhaps through themes, motifs, tropes, styles, genres, periods, and so forth – so as to assemble connections among a smorgasbord of texts that could range from the Epic of Gilgamesh to Lady Murasaki’s Tale of Genji to Chairil Anwar’s poetry to Chinua Achebe’s novels.Footnote 4

By contrast, global literature already arrives with a theme and connectedness: It thematizes the interconnectivities, the globalism, of early worlds. Whether the texts describe actual human travel, or show how a global religion arrives and reshapes local and regional lives, or demonstrate how art and artistry are exchanged along vast networks of trade, the texts of early globalism narrate interconnected worlds. They narrate with precision the intricate interconnectivity of the early world, and are produced by a multifarious world and its peoples. The texts are windows that open onto those interwoven, interknitted worlds.

This suggests another feature of global texts: Often, they do not offer themselves up as fiction or literary creations, but as accounts of how ordinary and extraordinary people lived their lives in the deep past, made their way in their world, and came to understand the environments and the societies they encountered.

Or they are reports of what people most valued – deeply held beliefs and ideas, remarkable art or important social practices, sought-after objects and goods – and how these came to interlink an early world. For that reason alone, students are often deeply curious about these texts, because they offer stories that not only open onto worlds, but stories that are lived worlds.

Sometimes, such texts even demonstrate global interconnectedness through their very composition: They demonstrate globalism by the way they have been assembled as a result of global transmission and accretion. One example is the co-created tale of Balaam and Josaphat, the story of the Buddha’s life that, in the course of westward journeying from India over a millennium and a half, gradually metamorphoses – thanks to being handled and reshaped by various societies through which the story passes – into the tale of two Christian saints, by the time the story reaches the West. A much more famous exemplar, of course, is The Thousand and One Nights, Alf Layla wa-Layla (also known as The Arabian Nights), a migratory, accumulating body of stories that have been co-created for a millennium and more, well into modern time.

Still, unlike survey courses on world literature, there are no Norton anthologies of global literature on which to rely for teaching. Nor, perhaps, should there be: There is little reason why we cannot offer students many global texts in their entirety, with some exceptions of gloriously long texts that cannot be responsibly studied in their entirety within a span of weeks. In the sections that follow, I’ll suggest texts that can be plumbed in entirety during a semester, and texts from which selections can responsibly be extracted.

Responsibly, here, is the key word. In teaching global literatures, a subject where we must surrender the pretense of mastery, we still have a duty – a responsibility – to learn as much as we can about the backgrounds, the historical and cultural contexts, styles, authors and authorial communities, that produced the texts we read in the classroom. We cannot throw up our hands that it’s all too much: that it’s impossible to learn enough to teach Sundiata, or the Malay Annals, or the Secret History of the Mongols with any degree of adequacy.

It is our responsibility to step outside our comfort zones, and incrementally, determinedly, extend our horizons of knowledge and learning as best we can. To aid us in this process is the reward of gradual familiarization: If you return to teaching early global literatures again and again, you will accrue incremental familiarity with the backgrounds and cultural contexts of your texts over time, and you can correct any possible earlier misapprehensions.

In this, your students can be allies. Students love nothing better than undertaking research. In lieu of requiring exams, quizzes, and tests, where students regurgitate what they have read, or what you have told them, consider asking for individual research presentations, and offering the possibility of collaborative projects where students conduct and share research and writing, an option I explore in Section 9 and elsewhere in this Element.

Students learn best when they are actively involved in hands-on work spurred by their own curiosity, interest, and preference – work of their own design – and, in the process, perform ownership of and shared responsibility for course content, which enables them to know that their contributions are valued as a significant and integral part of the course.

Whether your purview is literature, history, art history, or something else, there are also free aids in the form of online digital resources, such as Berkeley’s ORIAS websites, the Global Middle Ages Project (G-MAP) platform, an increasing number of titles in the born-digital Cambridge Elements series (with each title downloadable for free, and sharable, the first two weeks after publication), as well as hard-copy guides like the MLA’s Reference HengTeaching the Global Middle Ages, or, if you prefer, old and new giant tomes of world-history surveys for broad-brush, rapid background sweeps of information.Footnote 5

A caveat, however, as we consider the nonexistence of premade anthologies of literature and the imperative to step outside our comfort zones: In discussing the literatures of early globalism, I do not mean to suggest we should study what the world looks like through the eyes of Europe, as depicted in European literatures.

Yes, Chaucer’s Squire’s Tale mentions the name of Genghis Khan, and Mandeville’s Travels purports to be about the real world “out there” when it issues its simulacra. Yes, the Man of Law’s Tale has a fictitious woman fictively travel all over the Mediterranean, and the King of Tars fantasizes a Black sultan who turns white upon baptism.Footnote 6

But teaching early globalism does not mean reissuing familiar texts that describe nonwestern worlds and peoples as these are fictionalized or imagined by Europe’s authorial gaze. Reissuing European literature by the back door in this way, and rebranding Europe’s canonical and familiar texts as global literature is merely eurocentrism by another name.

This is not to say, of course, that we shouldn’t teach a critical canon of European literature, even as we teach a counter-canon of early global literatures. But we should not imagine that teaching European texts in a critical way is the same thing as teaching the global.

There are exceptional European texts, of course, that grant extraordinary views into far-flung worlds of their time, like Marco Polo’s and Rustichello of Pisa’s Le Devisement du Monde (The Description of the World) and early Franciscan reports of Mongol Eurasia and Yuan China, but these are exceptional historical accounts that decenter, rather than recenter the West, by virtue of the information they contain (whether or not the texts intend any decentering), and they can be useful additives in a global literature course. But we should remember that the purpose of teaching early global literatures is not to find new pretexts for reteaching Europe’s universally, extensively taught texts under rebranded course rubrics.

2 Why Teach Early Global Literatures and Cultures?

What is the purpose of teaching global literatures then? For those of us concerned with the dominance of eurocentrism in university curricula, an important reason to teach global literature is that, by its very nature, it loosens and uncenters the grip of the West, provincializing Europe avant la lettre by being produced elsewhere, drawing attention to the multifarious lives and places in the world’s many vectors.

In our current historical moment in the West, when white supremacists and ultra-nationalist extremists are busily fantasizing a glorified past in which so-called Christian-European values and civilization supposedly reigned triumphally in an idealized world of Christian domination, attention to the rest of the premodern world can be profoundly important.Footnote 7 Teaching the global can be a way to oppose pernicious ideological narratives of white-Christian-European supremacy and hegemony that purport to represent the deep past’s historical truths, authenticity, and facticity.

When students learn that the city of London had 100,000 people and Paris had 200,000, at a time when Cairo had three-quarters of a million inhabitants, and a number of China’s immense metropoles had populations of well over a million lives, an important shift in students’ understanding of the past occurs, so that ethical, responsible recoveries of knowledge can begin.

The teaching of global literatures and cultures is then a process of counter-narration – an ethical imperative that opposes fantasies of a past where Europe took center stage in white societies of unfractured Christian homogeneity, while the histories and cultures of the rest of the world are forgotten and erased, rendered unimportant.

That such erasure and forgetting has pernicious effects is seen from a report by an African American medievalist, Cord Whitaker, who has been repeatedly asked, “Where were the Black people in the Middle Ages?” Apparently, Whitaker’s “well-educated” interlocutors only knew of Africa from histories of slavery and colonialism in the modern era, and nothing of Africa’s histories and cultures before the encroachments of the West. Given the outrageousness of such lacunae, teaching the stories and cultures of the early world – especially, in this case, Africa – can be an act of epistemological and ethical commitment.

Teaching of this kind can even correct the narratives of the well-intentioned left, along with the ideological fabulations of the extremist right. For instance, it is impossible to read premodern global literature without recognizing that for its texts, every place is the center of the world.

No person or polity in the epic of Sundiata considers the Empire of Mali to be positioned on the periphery of a great world-system whose economic and political center is hived elsewhere, not in Mali. The magnificent city of Vijayanagar, capital of the Indian empire of the same name in Kamaluddin Abdul-Razzaq Samarqandi’s Mission to Calicut and Vijayanagar, is also the center of the world. Marco Polo’s and Rustichello da Pisa’s Hangzhou, surpassing other thirteenth-century megalopolises by its immensity of population, wealth, and cosmopolitanism, cannot be anything but the center of the world.

But it isn’t just size, wealth, or fame that decides what gets to be the center of the world. For each text, the world turns on the axis of wherever its people and their lives are. Everywhere is the world’s center. Global literature thus undercuts well-intentioned economic models like world-systems analysis that systematize the world into centers and peripheries through economic or other rationales, and undoes assumptions of cultural superiority or priority that might be extrapolated from such organizational schemas.Footnote 8 Wherever the people are is the center of the world.

In the twenty-first-century classroom, where demographic and population changes in the West have created cohorts of students in higher learning who are substantially diverse in terms of their race, class, and countries of origin, the recognition that every place is the world’s center acknowledges a multicentered – and thus, uncentered – world in which Europe assumes no special importance.

As significantly, for students whose ancestry, family origins, or childhoods were rooted in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Latin America, Pacifica, and elsewhere, the global literature classroom is a way to encounter their countries of origin outside the West before the advent of European colonialism and imperialism in the modern eras. Students learn that history does not begin when Europe arrives.

Indeed, the sheer diversity of global texts, lives, cultures, cities, treasures, arts, technologies, trade, and networks in a thriving premodern world in which a Christendom-that-will-become-Europe is little more than a backwater by comparison, shifts the scales of comparison and understanding for students.

Learning that ninth-century Tang China had ceramic industries that were already mass-producing ceramic wares for export to the rest of the world by the tens of thousands, carried by ocean-going vessels that enabled the international demand for Chinese ceramics to be met, a millennium before the West’s own mass-produced ceramics, thoroughly reconfigures a student’s understanding of commercial revolutions that are defined only in western terms (see Heng, Reference Heng“An Ordinary Ship”).

When a student learns that the tonnage of coal burnt in eleventh-century Song China’s iron and steel industries was already roughly seventy percent of the tonnage of coal burnt in Britain’s iron and steel industries at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the revelation that there could, in fact, have been a number of industrial revolutions, rather than a single, unique Industrial Revolution occurring only in modernity, and only in the West, is a mind-altering moment (see Hartwell, Reference Hartwell“Cycle,” and Reference Hartwell“Revolution”).

For graduate students, one important outcome of learning globally is the incubation of new habits in thinking and research. Global learning fosters habits of reaching across cultures in the kinds of questions asked and the kinds of projects pursued. Even as departments and programs continue to ensure deep disciplinary training and knowledges, the aggregative process of global-local-regional training over time produces the happy result of distinctively new skills and professional identities for graduate students in what seems a perennially challenging academic market.Footnote 9

Focusing on the global, of course, also works to bring medieval studies itself – a field that is still occasionally misunderstood by the rest of the academy as concerned largely with obscure interests mainly fascinating to academic antiquarians performing custodial functions for archives of little importance or urgency to anyone else – more visibly into conversation with other kinds of teaching, including contemporary globalization studies, in the twenty-first century academy.

Two decades ago, an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education showed what was at stake, by pointing to the dangers that lay ahead for a field whose interests were thought to be unimportant to the rest of the academy or society at large. In 2003, a journalist, Reference GalbraithKate Galbraith, reported The Guardian quoting Charles Clarke, Great Britain’s Secretary of State for Education at the time, facetiously intoning, “I don’t mind there being some medievalists around for ornamental purposes, but there is no reason for the state to pay them” (emphasis added).

While medievalists in Britain were stung by this ignorant cabinet official’s condescension, they also seemed to have difficulty arguing for their work’s importance. Reference GalbraithGalbraith quoted a Cambridge medievalist falling back on an old vagueness, when she defended medievalists as “working on clarity and the pursuit of truth.” The Cambridge scholar’s lament that Clarke was “someone who doesn’t understand what we do” touched on precisely the problem.

Nearly two decades later, the situation worsened: In 2021, the University of Leicester was reported as replacing its medieval literary curriculum with a decolonial curriculum prioritized by university administrators as urgently necessary in twenty-first-century England, thereby rendering the medievalists in Leicester’s English department redundant (Reference JohnstonJohnston). Leicester’s demand of a decolonial curriculum, we might note, could have been met with critical teaching of an early global world: a critical pedagogy that meets the objectives of diversity, equity, and inclusion that have become important priorities in today’s academy in the West.Footnote 10 Since 2021, other universities have also ended medieval programs (see, e.g., Reference CassidyCassidy).

3 Organizing a Course, and a Scaffold of Questions in Search of Answers

It is important to acknowledge, from the outset, that global literature can only be taught through textual translations. When David Damrosch leads a world literature class on Gilgamesh, we must assume that nobody is first required to learn Sumerian or Akkadian. The sample list of possible teaching texts I outline in Section 4 includes accounts in Old Norse, Mande/Mandingo, Arabic, Jawi/Malay, Chinese, Uighur-Mongolian, Latin, Syriac, Franco-Italian, and Hebrew: Any concatenation of global texts is going to be unteachable except through translations.

Thanks to the proliferation of translation theory in the academy, we are familiar, of course, with the problematics and politics of translation. We understand that every translation is a rewriting and a re-creation, not a facsimile or clone of the original that becomes replicated, with perfect exactitude, in another language. We recognize that translators make choices that can alter the sense of a word, a sentence, a passage; and that affect, meaning, and emphasis can all shift across the translational process.

Perhaps because we work with multiple languages, premodernists are among those who are most alive to the fact that any translation is never co-identical with the original from which it is reconstituted – if, that is, an original can even be determined, which is no sure thing in premodern literature. Inevitably, there will also be terms and concepts in all languages that we will deem utterly untranslatable.Footnote 11

But the success of many translations-as-re-creations – from the King James Bible to Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf, to name just two famous examples in the West – argues for the value of translations that evince cultural sensitivity, nuance, tact, and insight, as well as literary richness and genius.Footnote 12 More recently, Zrinka Stahuljak has argued for assessing a translation for its qualities of commensuration, not for its attempt at equivalence, so that equality, not exactitude, is the hallmark of translational success and effectiveness.Footnote 13

Rather than seeing translation as a process of loss and distortion, we might then instead join the ranks of those who see translation as a creative, enlivening process that mediates between an original text and the new audiences to which the text would speak, and for whom it must become intelligible in order for its life and significance to continue. This is especially important for texts originally created in languages and dialects hundreds of years old, that can be accessed by fewer and fewer people today in their original languages.

We might join those who wish for more translations, so that the supply of available translations, and translational variety, can be enlarged, and a greater number, not a fewer number, of choices becomes availableFootnote 14 – especially for instructors who might wish to conduct comparative linguistic study across translations and texts.Footnote 15 We may even hope that introducing students to texts they have never encountered before, through translation, might be a way to fascinate and to interest students in acquiring new languages.

So, rather than thinking of translation as something that must always detract from a text – and teaching in translation as disseminating imperfect, inexact replicas from which something is always missing or askew – we might see translation instead as the invitational dynamic that allows a text to acquire its fullest possible audience over time, as well as its widest possible range of significance for those audiences, as Damrosch urges (Reference DamroschHow to Read 5).

Without translations, premodern texts with few exceptions are easily neglected or forgotten, confined to their initial audiences who are distant in time and place.

Noncanonical premodern texts are, of course, the most vulnerable, readily ignored and forgotten – especially, let’s face it, in contemporary literature departments saturated with a multitude of modern literatures and the alluring creations of popular culture and digital media. By contrast, circulating early literatures through translations conduces to ensuring their continual reception across time, well into the future, and grants premodern texts long, rich, afterlives.

In this way, translation can be seen as imparting “a new stage in a work’s life as it moves from its first home out into the world” (Damrosch, Reference DamroschHow to Read 84). We might even say that teaching with translations performs an exchange between the past and the present that parallels the sociocultural and geospatial exchanges so often thematized in global texts. This is a positive outcome of the fact that there can be no courses on global literatures (or world literatures) without translations.Footnote 16

The actual texts we select for teaching a course on early global literatures and cultures will depend, of course, not only on the translations available to us, but also on what we want from the course. When I first began teaching early global literatures, a student asked, “What do you want us to know?” Her simple question went right to the heart of things. What the driving questions are, for you, will decide the texts you choose for your syllabus, and determine how you shape your course. Each person’s answers will differ, and the discussions below are shaped by my own imperatives.

The broadest driving questions that scaffold my teaching of global literatures are the obvious ones: (1) Why does knowledge of the early world matter today? (2) What interconnects that early world? We know what interconnects the modern and contemporary worlds, but the globalization of the twenty-first century is not the globalism of premodernity.Footnote 17 (3) What does that early interconnected world look and feel like? This is an invitation to consider not just people, but climate, environment, towns and cities, topography, oceans, flora and fauna, and even how time is experienced. These large questions – each of which allows for finer-grained, detailed sub-inquiries – decide what texts are best suited to teaching a course.

Why does knowledge of the early global world matter? To combat Eurocentrism, and pernicious white supremacist fantasies. To end the ignorance and atomization of knowledge that represents whole continents as without a history till Europe arrives. To critically decolonize the curriculum. To expand the horizons, skills, and opportunities of a graduate education. To be responsive to increasingly diverse twenty-first-century classrooms of global citizens. To ensure that a cultural archive of noncanonical, readily ignored texts are taught, and find contemporary audiences and significant afterlives. To end any lingering assumptions that premodern studies today represent obscure, ivory-tower indulgence in a world and an academy of shrinking resources. And more: Ultimately, the goal is the transformation of teaching in the twenty-first-century academy itself.Footnote 18

What interconnects the early world? People in motion, for a variety of reasons; goods in motion; religions that spread; art and artistry in dynamic exchange; political and military power amassing territory. What did that interconnected world look and feel like? Answering this, leads us to global cities and how people lived and worked in them; to climate change and monsoons that enabled passage across oceans; or how the experience of time might involve counting the intervals between obligatory prayers, or the length of time it takes to read verses of the Quran.

Together, the questions remind us that the interconnectedness of an early world is not the planetary globalization of today, a globalization that – at least in theory – touches every part of our planet. Early globalism is not tantamount to, and should not be equated with, a twenty-first-century globalization that knits together, however unevenly, the inhabitants of all pockets of the planet.

Rather, we can conceptualize early globalism as a push for ever-larger scales of relation. The drive to invade, conquer, and occupy globalizes, but language also globalizes. Religion globalizes. Cultural habits, styles, artistic motifs globalize. Popular stories that travel widely globalize. Some forms of globalism in an early world are thus not spatial, or geographic, but assume a linguistic, artistic, religious, or cultural character.

We see, in this way, that early globalism involves not just a concept of interconnected, interrelated spaces and geographies, but also a dynamic: forces pushing toward larger and larger scales of relation.

The reminder of differences between the present and the past is helpful in a number of ways. For instance: A teacher or student of global literature should not feel a requirement to find texts addressing every place on the planet, nor feel a corollary obligation to establish the interconnectivity of each corner of the earth with every other corner of the earth through literature. The study of early globality is not synonymous with the study of planetarity.

Though Europeans in the form of Greenlanders and Icelanders crossed the Atlantic Ocean to reach the North American continent around 1000 CE, they did not cross the Pacific Ocean to reach Austronesia. Though China’s imperial “treasure ships” helmed by the Muslim eunuch admiral Zheng He crossed the Indian Ocean to reach Africa in the fifteenth century, they did not arrive in Austronesia, the Americas, or Antarctica. Extraordinarily, DNA research in plant biology now seems to indicate that Oceanic peoples traversed half the watery world to reach the South American continent, but there are no suggestions yet that the inhabitants of Oceania arrived in Siberia or Greenland. As new discoveries are made, of course, we can adjust syllabi to suit, but a totalizing comprehensiveness that must aim to envelope everything, everywhere, is neither the point nor the spirit of a global literature course.

For the present, the examples I suggest in the next section as one possible spectrum of texts to consider for critically investigating the interconnectivity of the early world will show early globalism at work as a dynamic and a force, as well as globalism in the more conventionally understood sense of interconnected spatialities and geographies.

When a religion like Islam makes its way out of the Hijaz in Arabia to West Africa, up the Volga to the Eurasian steppe, and into South Asia and island Southeast Asia, we can follow the pathways of early globalism by examining the tracery of a global religion’s travels and its impact on local and regional societies as conveyed in textual accounts. Literature also shows globalism at work when Indic culture scatters across maritime Southeast Asia, spreading names and mythologies, along with Buddhism and Hinduism, all of which is highly visible in texts.

Literary texts also show Pax Mongolica famously securing overland trade routes and moving artisans and goods around the vast Eurasian continent from termini to emporia, so that an English king, Edward I, can wear Chinese brocade as part of his inauguration robes, and an Indian monarch at Vijayanagar, Deva Raya II, can wear a tunic of Zaytuni silk from Quanzhou, and fan himself with a Chinese fan, as reported by a Muslim diplomat from the Timurid empire. Continual experimentation will disclose myriad forms of globalism that may not be apparent until you begin the journey with students into the terra incognita of the global literature classroom.

4 What Should We Teach? Two Dozen Texts from Which to Extract a Possible Syllabus

To open windows onto an interconnected early world, I have a cluster of favorite texts that cycle in and out of my syllabi over the years, subject to change and substitution. Many other texts can be productively taught, of course, and this is just one possible concatenation among innumerable from which to choose. The selection combines well-known and less familiar texts, with translations available in English, but instructors located in French, German, Italian, Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, and other literature departments should be able to substitute appropriate translations in their own vernaculars.

After trial and error, this is the cluster of texts from which I currently extract a working syllabus:Footnote 19

The Vinland Sagas: The Norse Discovery of America (Reference Magnusson and PálssonMagnusson and Pálsson; and/or Reference JonesJones, Eirik the Red and Other Icelandic Sagas; and/or Reference KunzKunz, “The Vinland Sagas”)Footnote 20: taught in full, and paired with The Ice Hearts (Reference BruchacBruchac) and Skraelings (Reference Qitsualik-Tinsley and SeanQitsualik-Tinsley) – novellas which imagine how Native North Americans might have viewed the settler-colonists of Greenlanders and Icelanders – and online exploration of the “‘Discoveries’ of the Americas” project on the G-MAP platform at www.globalmiddleages.org.

Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali (Reference Kouyaté and PickettKouyaté-Niane-Pickett); and/or Sunjata: A New Prose Version, by Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradCondé-Conrad; and/or The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition, by Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson): taught in full, and paired with online exploration of the empire of Mali in the Zamani Project (https://zamaniproject.org), the Timbouctou Manuscripts Project (http://www.tombouctoumanuscripts.uct.ac.za), the “Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time” exhibit at Northwestern University’s Block Museum (https://www.blockmuseum.northwestern.edu/exhibitions/2019/caravans-of-gold,-fragments-in-time-art,-culture,-and-exchange-across-medieval-saharan-africa.html and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6C_WCz67Dw) that emphasize the north–south gold caravan routes of the Sahel and Sahara, in which Mali is prominent, alongside selected readings from the exhibition catalog of the same name, edited by Reference BerzockKathleen Bickford Berzock. Students may also consult, as needed, the Berkeley ORIAS website on Sundiata (which seems aimed at high school teachers: https://orias.berkeley.edu/resources-teachers/monomyth-heros-journey-project/sundiata).Footnote 21

Ibn Battuta in Black Africa (Reference Hamdun and KingHamdun and King), selections from accounts of the famous Moroccan traveler’s sojourns in West Africa (extensively recounted by Ibn Battuta) and East Africa (parsimoniously recounted by him): paired with selected readings from Reference GomezAfrican Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa (Gomez) and Al-Jahiz’s Reference Preston and CornellThe Book of the Glory of the Black Race (Preston/Cornell; and/or Reference KhalidiThe Boasts of the Blacks Over the Whites, Khalidi).

Ibn Fadlan’s Mission to the Volga (Reference Montgomery and ibn FadlanMontgomery, James E.; and/or Reference FryeIbn Fadlan’s Journey to Russia: A Tenth-Century Traveler from Baghdad to the Volga River, Frye): taught in full, with clips from the film Reference Binyam and KrebsThe Thirteenth Warrior (for visual depiction of Nordic hygiene and funerary customs). Facing-page text in Arabic, in Montgomery’s edition and translation of Ibn Fadlan, appears in Reference Montgomery and FadlanTwo Arabic Travel Books, a volume that also contains Abu Zayd al-Sirafi’s Reference Mackintosh-SmithAccounts of China and India, translated by Tim Mackintosh-Smith.

Ibn Jubayr’s travels around the Mediterranean: taught as selections from Reference BroadhurstThe Travels of Ibn Jubayr (Broadhurst), and paired with selections from Usama ibn Munqidh’s Reference CobbBook of Contemplation (Cobb), and clips from Kingdom of Heaven (for visual depictions of architectural hybridity in the portrayal of Jerusalem and crusader territories, the famed “pincer movements” of Seljuk/Arab militaries in the field, and the politics of coexistence under crusader occupation), with selections focusing on crusades/counter-crusades/holy war, and social-religious-cultural accommodations in life on the ground, as modalities of globalism in Syria, Palestine, Sicily, and the eastern Mediterranean.

The Arabian Nights (Reference HaddawyHaddawy; and/or Tales from the Thousand and One Nights, Dawood; and/or The Arabian Nights, Reference Heller-Roazen and HaddawyHeller-Roazen and Haddawy; and/or The Annotated Arabian Nights, Reference Seale and HortaSeale): taught as a series of rotating selections that are chosen for different emphases in different iterations of the syllabus.Footnote 22

Buzurg ibn Shahriyar’s The Book of the Wonders of India: Mainland, Sea and Islands (Reference Freeman-GrenvilleFreeman-Grenville): a lesser-known compendium of accounts and tales by mariners, attributed to a sea-captain of Ramhormuz, that can be taught in full, and is excellent for comparison with the fictional sea-oriented stories in The Arabian Nights such as Jullanar of the Sea, The Third Dervish’s Tale, and The Tale of the First Lady in The Story of the Porter and the Three Ladies. Also useful for comparing with sea journeys in nonfictional texts – sea-travel stretches across several texts in this cluster – and with accounts of caravan journeys across the Eurasian landmass.

Documents from the Cairo Genizah – in particular, a selection from India Traders of the Middle Ages (Reference Goitein and FriedmanGoitein and Friedman) featuring the business transactions, agents, and relationships of the Jewish India trader Abraham ben Yizu – paired with Reference GhoshAmitav Ghosh’s In an Antique Land: History in the Guise of a Traveler’s Tale and Ghosh’s Subaltern Studies article, Reference Ghosh, Chatterjee and Pandey“The Slave of MS. H.6”: These texts, which narrate the movement of goods and people between North Africa and India, include a focus on Ghosh’s attempt to recover, from the anonymity of history, the name and identity of an enslaved South Asian man on the Malabar coast who functioned as ben Yizu’s business agent in the twelfth-century Indian Ocean trade. The texts thus form an important corrective to narratives of empire-formation and imperial history that tend to feature prominently in archives of texts that survive (including the ones listed here) and constitute a key way to demonstrate to students how importantly histories-from-below, and microhistories, can contribute to our understanding of early globalism.

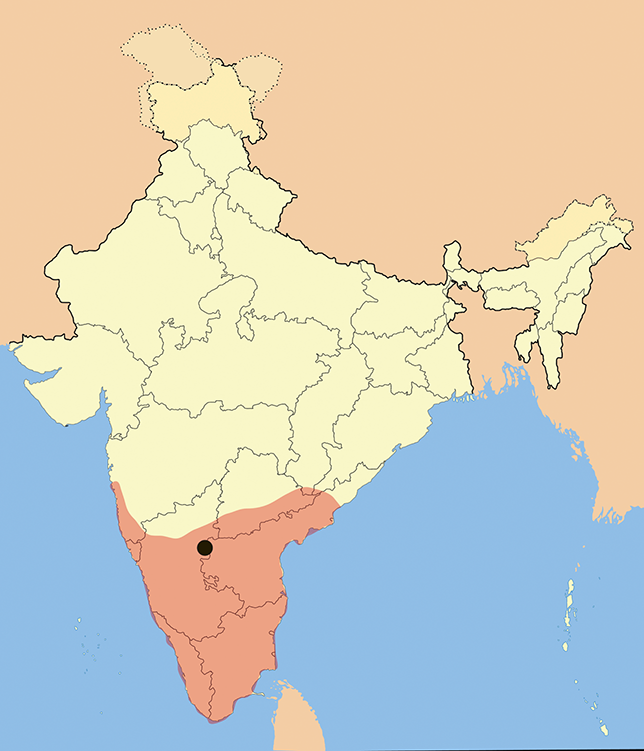

Reference ThackstonKamaluddin Abdul-Razzaq Samarqandi’s Mission to Calicut and Vijayanagar (Thackston): taught in full, and containing a spectacular description of a premodern global city – Vijayanagar – with detailed portrayals of the city’s infrastructure, layout, and architecture, its markets and vendors, elephantorium, mint, and bordello, complete with festivals and spectacles, and the Muslim diplomat-narrator’s account of India’s port cities, the hazards of sea travel, flora and fauna, temple art and architecture, and featuring pungent ethnoracist commentary on South Asians.

Selections from the Reference WilsonSejarah Melayu or Malay Annals (Brown): a chronicle-cum-epic depicting the cultural and mythological relations between India and island Southeast Asia, especially as transacted through the global Alexander legend, with storied accounts of the web of sea-borne interrelationships among the island-polities of maritime Southeast Asia. My selection begins at the beginning and ends at the point of the formation of the Malacca Sultanate, including the formation of the port-city of Temasek (premodern Singapore), and the dynamic movement of prestige and power among these island-societies and kingdoms in a world dominated by seas and water.Footnote 23

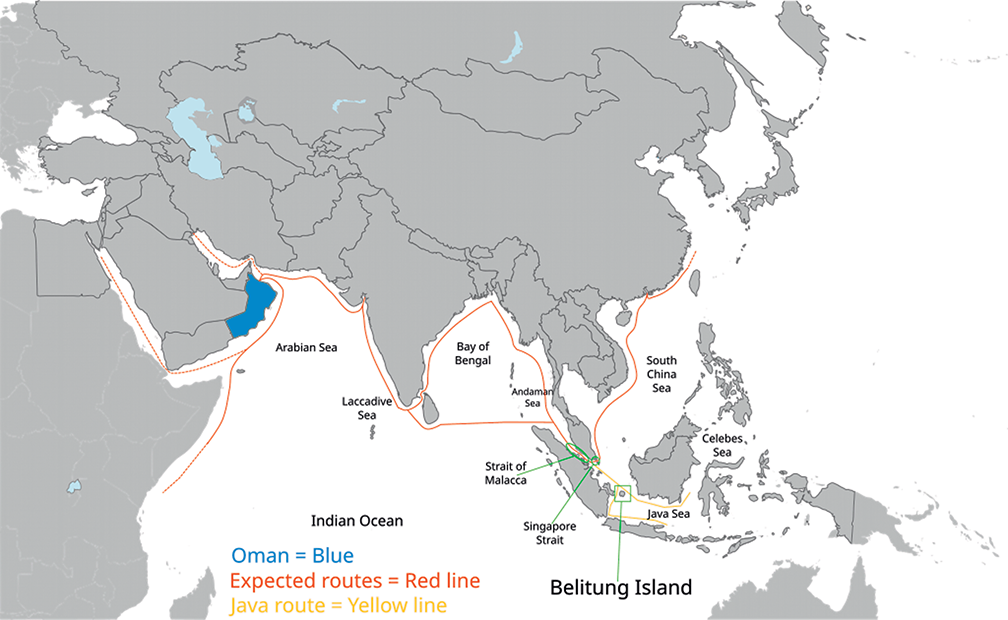

Reference Mackintosh-SmithAbu Zayd al-Sirafi’s Accounts of China and India (Mackintosh-Smith, with facing-page text in Arabic): taught in full, and paired with online exploration of the Tang Shipwreck exhibit at the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore (http://globalmiddleages.org/project/tang-shipwreck): This is a handbook of ninth- and tenth-century merchants’ accounts, primarily of China, but also of India, compiled in two books, the first attributed to Sulayman al-Tajir (Sulayman the Merchant), and the second claimed as Abu Zayd’s. Excellent for comparison with other merchants’ accounts of China and India, like Polo-Rustichello’s Description of the World; fictional stories of mercantilism and travel in Reference HaddawyThe Arabian Nights; and other texts in this cluster like the Reference Heng and HengMalay Annals, and Reference ThackstonMission to Calicut and Vijayanagar for descriptions of islands and seas, coastal ports, and merchandise. Exploration of the Tang Shipwreck helps to bring alive the ships (including hand-sewn ships, without nails), cargoes, and peoples described by Abu Zayd.

Reference HennesseyProclaiming Harmony (Hennessey): recommended to me by the Sinologist Valerie Hansen, and taught in full, to introduce students to the repeating phenomenon of premodern China’s history of invasions-and-displacements through a fourteenth-century semi-fictional dramatization of historical events that occurred two centuries earlier: featuring the disastrous reign of Huizong, the last emperor of the Northern Song dynasty and his profligate, debauched rule, his trust in corrupt, inept officials, and his eventual captivity and deportation, along with his son and their wives, to Manchuria, by the Juchen conquerors who formed the Jin dynasty before the advent of the Mongols.

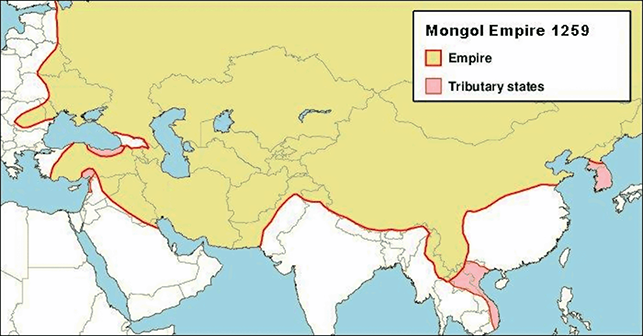

Reference De RachewiltzThe Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century (de Rachewiltz, 3 vols; and/or Reference AtwoodThe Secret History of the Mongols, Atwood), paired with Mongol: The Rise of Genghis Khan (Bodrov): The first three chapters can be taught in undergraduate courses; graduate students can read the full text. The full text, in volume 1 of Reference De Rachewiltzde Rachewiltz, is available online as an open-access book of 268 pages (Reference De Rachewiltzde Rachewiltz’s print version of vol. 1 is 642 pages long): https://cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=cedarbooks. Volume 2 comprises invaluable historical, contextual, stylistic, and background apparatuses, and a supplementary volume 3 has an updated commentary, revisions, and some new interpretations. A Penguin translation, by Reference AtwoodChristopher Atwood, was published in late 2023. Mongol, the first of Sergei Bodrov’s three-part film series, is useful to help students visualize the landscapes, environment, clothing, and customs of the Mongols, and for listening to the Mongolian language and throat-singing. The sequel, Mongol II: The Legend, is being financed for production at the time of my writing.Footnote 24

John of Plano Carpini’s History of the Mongols (Reference DawsonDawson, Mission to Asia 1–72): taught in full, together with Dawson’s introduction (vii–xli), “Two Bulls of Pope Innocent IV Addressed to the Emperor of the Tartars” (Reference DawsonDawson 73), “Guyuk Khan’s Letter to Pope Innocent IV” (Reference DawsonDawson 85), and an extract from chapter 6 of Race (“The Mongol Empire: Global Race as Absolute Power”) on the Hystoria Mongalorum (287–302).

William of Rubruck’s Journey (Reference DawsonDawson, Mission to Asia 89–220; and/or Reference Jackson and MorganJackson and Morgan’s The Mission of Friar William of Rubruck: His Journey to the Court of the Great Khan Mongkë 1253–1255): taught in full, together with the letters of Franciscan missionaries to China – John of Monte Corvino, Peregrine of Castello, and Andrew of Perugia (Reference DawsonDawson 224–237) – and an extract from chapter 6 of Race (“The Mongol Empire: Global Race as Absolute Power”) on William of Rubruck (298–323).Footnote 25

Rabban Sauma’s journey to the Latin West (Reference BorboneBorbone; also translated by Reference MontgomeryJames A. Montgomery; by Reference BudgeBudge; and excerpted as chapter 4 of Reference MouleMoule), recounting the journey of a Uighur/Ongut monk/priest/envoy named Sauma, of the Church of the East (the so-called “Nestorian” Church) – whose one-time fellow-sojourner, Mark, aka Yaballaha or Jabalaha, became Patriarch of the Church of the East – as Sauma journeyed to the Latin West.Footnote 26 Sauma had polite discussions-that-seemingly-did-not-amount-to-disputations with the Curia in Rome, visited shrines and relics, was blessed and given gifts and honors by Pope Nicholas IV, and performed a mass of the Eastern rite in Gascony in 1288 attended by Edward I of England, who took communion at the hands of Sauma – a churchman who, under other conditions, would likely have been considered a heretic by the thirteenth-century Latin Church.Footnote 27

Marco Polo-Rustichello of Pisa’s Description of the World (Reference Moule and PelliotMoule and Pelliot; and/or Reference LathamLatham, The Travels of Marco Polo; and/or Reference KinoshitaKinoshita): taught in full and paired with the sections on Polo-Rustichello in chapter 6 of Race (“Marco Polo in a World of Differences”), 323–349. Though long, this European text coauthored by a Venetian merchant and an Italian romancer decenters the West to such an extent and is so detailed in its global description of goods, peoples, and lands that it is worth teaching in entirety. Also, merchant accounts form an important counterpoint to accounts by religious personnel and diplomats, and accounts about warriors and empire-formation that may otherwise dominate a syllabus.Footnote 28

The preceding texts are most useful for my current purposes in devising a syllabus, but the following texts are also excellent to consider.Footnote 29

Benjamin of Tudela’s Itinerary (Reference AdlerAdler)Footnote 30

Selections from Ata-Malik Juvaini’s Genghis Khan: The History of the World Conqueror (Reference BoyleBoyle)

Rashid al-Din’s The Successors of Genghis Khan (Reference BoyleBoyle)

Selections from Ibn Battuta’s Travels (Reference Gibb, Beckingham and Mackintosh-SmithGibb)

5 What Interconnects the Early World? What Does that Early World Look Like? Teaching The Vinland Sagas, Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali, and Ibn Fadlan’s Mission to the Volga as Global Texts

Observant readers will notice that the texts listed in Section 4 more or less move students across the globe from west to east, starting with North America, and ending with China, after visiting trans-Saharan Africa, Eurasia, North Africa, the Mediterranean, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. This is partly an organizational idiosyncrasy – another instructor may prefer to have texts advance chronologically or thematically – and partly a preference born of students’ satisfaction at seeing themselves literally proceed across the world with each reading.

This and the next sections go on to discuss ways to teach some ten texts combed from the basket of teachable texts in Section 4, augmenting the discussion with references to additional texts that, because of an Element’s word limitations, cannot be treated in detail. For reasons of length limitations, I concentrate on issues of globalism, and the aims identified in the preceding sections as of particular urgency or significance, leaving aside more literary considerations to subject specialists of these texts cited in notes and the bibliography.Footnote 31

To my regret, the texts listed in Section 4 focus primarily on narrative, written literatures (including accounts finally written down after centuries of orature), and so bracket for now the globalisms of Mesoamerica, Austronesia, Native America, and Oceania (nonetheless, island worlds are here represented by the Malay Annals). I’ve noted, of course, that teaching the global in premodernity need not be tantamount to teaching the planetary, but others might wish to consider materials studied by art historians, archeologists, and historical anthropologists, and treat inscriptions, epigraphs, law codes, folklore/legends/myth, among other cultural resources, as varieties of global literature.Footnote 32

In classroom teaching, I begin by telling students we are guided by a set of focal points that become incrementally elaborated as the semester advances. I ask students to keep an eye on those focal issues that particularly interest them, as they read text after text, so that by the semester’s end, they will have acquired a rich comparative perspective across the world’s cultures.

The focal questions begin like this: What does globalism look like in a given text? How is the unknown represented in global encounter? How are otherness and difference represented? Do climates and ecoscapes elicit types of human responses that repeat across the world? How are women treated, what are their roles, and are there similarities across cultures? What constitutes wealth or treasure for a society? How is a society organized, and what are its values? What kinds of animals, plants, tools, arts, and occupations seem to matter the most? What particular colors, directions, rituals, and customs are given special significance? And, not least of all, what bridges exist across differences and incomprehension in global encounter?

I warn students there will be disorientation as we move across the world, repeatedly encountering new strings of names and naming traditions, strange environments, unfamiliar social and cultural mores, perplexing forms of magic or the supernatural, metaphysical or religious beliefs antithetical to their own, as well as literary and narrational styles and genres that will change with every text.Footnote 33

Usually, literature majors and minors can reliably be counted on to use the close reading skills they’ve acquired to engage with the texts we read. If they feel overwhelmed by a mass of details, I ask them to follow the main characters, and the primary arc or arcs of narrative as a practical measure, and to raise questions when something is so unclear that they have not been able to ferret out its meaning after trying.

I explain that I will not be able to answer every question they have, and they should expect to do research, and find answers of their own, to share with the class. But I also tell them they should never hesitate to ask questions for fear of looking foolish or ignorant – because, in the terra incognita of the global literature classroom, there are no bad questions. No questions are out of bounds.Footnote 34

“What do you want us to know?” a student once asked on the first day of class, preempting the question I usually ask them, what do you want from this class?

I tell students I’d like them to know that globalism (to be distinguished from our contemporary globalization)Footnote 35 did not begin in the modern era, nor with European colonial maritime expansionism and “discovery” across the world. Cosmopolitan global cities like Vijayanagar, Cairo, and Quanzhou dwarfed the towns of Latin Christendom/Europe; supernovas were charted in eleventh-century China; the number zero had appeared in Indian mathematics by the seventh century; and linear algebra had been invented outside the West by the thirteenth (Reference HartHart).

Understanding that thriving, nonwestern cultures and civilizations existed, and were in dynamic interchange for centuries and millennia, undercuts grands récits about modernity and the West that have been cloned and recloned in the academy and public culture for generations, and gives the lie to alt-right fantasies of a dominant Christian Europe whose assumed supremacy relegates the rest of the early world to erasure.

So, to begin.

The Vinland Sagas: The Greenlanders’ Saga and Eirik the Red’s Saga

Beginning with the Vinland Sagas and Nordic journeying from eastern Greenland across the Atlantic to North America highlights an important focal question: Why did premodern peoples travel, given the extreme hazards and sometimes near-impossibilities of long-distance journeying? Student responses, partly conditioned by Hollywood and television, will include: a desire for exploration, a love of adventure and discovery, and “because it’s there.”

According to the Sagas, however, the motives of the would-be settler-colonists in “Vinland” – North American regions believed to be somewhere in New Brunswick, around the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Miramichi River, though excavation has thus far only unearthed the settlers’ gateway or staging post at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland – involve resource extraction.Footnote 36 While a mix of reasons may have prompted the journeys – from characteristic patterns of Nordic settler-colonization, to individual and communal impulses – the Sagas usefully establish the profit motive as an impelling prompt.

The Sagas depict a North America around 1000 CE teeming with rich natural resources: timber from tall trees absent in Greenland and essential for boatbuilding and homesteads; wild grapes for making wine, a high-value prestige product usually requiring importation from the Mediterranean; “wild wheat” (a kind of rye?) growing unbidden, without the need for cultivation; fish fat in tidal pools when the tide went out; and a climate so mild in Vinland’s southern outpost, even in winter, that livestock could conveniently be kept outdoors (56–57, 65, 95, 98).Footnote 37

In addition to the land’s Edenic natural resources, the Sagas also relate how the Indigenous peoples of North America proffer valuable furs and pelts in trade for what the settlers extend – sips of milk, or strips of red cloth (65, 99). Accordingly, the Greenlanders’ Saga (henceforth, GS) shows Thorfinn Karlsefni, co-leader of the most prominent North American expedition, growing wealthy from his Vinland enterprise. Disembarking in Norway after departing Vinland, Karlsefni unloads and sells his furs, pelts, and other Vinland treasures – including a ship’s figurehead carved from North American wood – for a small fortune, thereafter buying a farm and homestead in Iceland where his and his wife’s descendants (which include three bishops) live for generations thereafter.Footnote 38

The profit motive, students begin to see, is a theme that runs through global texts. While humans may indeed desire adventure and exploration, profit is a reliable instigator of trans-world journeying, despite all hazards and risks. The Sagas also introduce the idea that what is considered valuable, and constitutes wealth, assumes different forms in different places. Timber and grapes (and wine made from grapes) are not palpably forms of wealth in students’ lives today, though these are animating attractions for the earliest visits to the North American continent. Students may find imagining a world where lumber is scarce a worthwhile thought experiment.

Beginning a global literature course with the Vinland Sagas also at once raises the paramount role of climate and atmospheric phenomena in shaping early globalism. In the eleventh century, a period of global warming dubbed the Little Climatic Optimum, the Medieval Climate Anomaly, or the Medieval Warm Period (among other names) increased the temperature in circumpolar regions by a few degrees, thereby enabling the Atlantic to be traversable in summer months.Footnote 39

Students may notice on their own that even after the settler-colonists are routed by native Indigenous populations in pitched battles, and decide to abandon their settlements, the Sagas show they do not leave till summer arrives, but merely hunker down in their more northerly camp, where no Indigenous are ever encountered, till the weather allows for departure.

They should also be told that Greenland, from which the European settler-colonists sailed, would itself be abandoned during the Little Ice Age that arrived in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, leaving Greenland habitable only by the Inuit, whose lifestyles were adaptable to late-medieval climate change. Climate change is an issue close to students’ minds, as their generation inherits the Anthropocene created by earlier generations and ours, and the Sagas bring home the impact of climate on human lives.

Indeed, students will encounter the impact of climate and atmospheric conditions again and again in the semester’s readings. Journeying from the Abbasid Caliphate up the Volga, the Arab emissary Ibn Fadlan is taken aback by how his beard freezes in the cold after his bath, and how layers of clothing necessary for warmth obstruct his being able to move on his mount. But while atmospheric conditions pose challenges, they can also awe: The aurora borealis is a marvel Ibn Fadlan beholds, an extraordinary spectacle to be experienced in a lifetime.

In other texts, students will see how the weather phenomenon of winds known as the monsoons (from Arabic, mawsim, “season”) decides in which direction a ship can sail across the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, and during which months of the year. Diplomats, merchants, and sailors are stranded in ports, awaiting the right winds to blow from the right direction, before they can complete their missions and enterprises. The impact of climate and weather upon human ambitions and human activity is a repeating, sometimes sobering lesson.Footnote 40

Crises and exigencies that arise are shown to elicit a range of human responses. In premodernity, many responses involve explanations issuing from religious faith, especially among people espousing the Abrahamic confessions. In the Sagas, clashes between Christian and “pagan” viewpoints furnish opportunities to discuss the spread of global religions like Christianity, and how the arrival of a global religion changes local behavior, but also meets with resistance.

Eirik the Red’s Saga (henceforth, ESR) has an episode of hunger in Vinland where those who follow Thorhall the Hunter and eat the flesh of a “whale” that washes ashore at the northerly outpost of Straumfjord – a food source Thorhall glosses as a reward from the Norse god Thor – fall violently ill. Those who abstain from eating the animal and pray to Christ instead are rewarded with good weather and good fishing soon afterward (95–96). Christianity wins, here and elsewhere in the Sagas, as a new global religion is shown successfully to displace older faith traditions.

But ESR also describes a famine in Greenland, and how a sorceress, Thorbjorg, is invited to Herjolfsness to prophesy the future to anxious homesteaders. Treated with great deference, her outlandish appearance and demands meet with no hint of criticism, and even possibly a touch of awe. When the sorceress calls for old warlock songs to be sung, an opportunity is created to demonstrate possession of deep pagan knowledge by Gudrid Thorbjarnardóttir, Karlsefni’s important wife-to-be, yet also Gudrid’s strong commitment to Christianity, signaled by her initial refusal to perform the songs. Eventually, after singing the warlock songs beautifully, Gudrid is rewarded with sorcerous prophecy of an eminent lineage to issue from her (81–83).

Students quickly see Gudrid’s consent to performing old pagan songs, despite her initial reluctance, as essential to her characterization as someone who is the ideal woman in her society – a good Christian reluctant to perform forbidden pagan knowledge, but whose commitment to hospitality and civility is overriding, and ultimately allows her to behave like a wise woman bestriding old and new worlds, possessing wisdom in both.

Gudrid’s role in the Sagas thus offers an opportunity to begin a discussion thread on the roles of women in early global texts. Both GS and ESR highlight episodes where male settler-colonists, on encountering the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, gratuitously kill them, cheat them, and commit various kinds of violence. I discuss these episodes in detail in Invention of Race (chapter 5), and will refrain from rehearsing the discussion here, except to say that these episodes form prime examples of a racializing dynamic seen to occur in early global texts when members of one civilization encounter members of another civilization who seem wholly foreign to them.

Native North Americans are presented in the Sagas as primitive peoples fascinated with the superior metal technology of the expeditioners’ weapons, and as naifs ignorant of the value of their furs and pelts in the international circuits of commerce to which the expeditioners have access. The racialization of Indigenous peoples thus turns not only on their physical appearance – facial features, hair, coloring, clothing – but also on the assumption that the Indigenous are located relatively low on a socio-evolutionary ladder of civilizational maturity. (That the expeditioners are nonetheless routed by the natives in pitched battles is an embarrassment the Sagas do not address.)

Themes of comparative civilizational maturity are introduced again and again in texts of global encounter. The Sagas usefully lend themselves to addressing this thematic early in the semester.

Revealingly, an episode in GS featuring Gudrid serves up a counterexample to the masculine violence on display in the Sagas: Gudrid is sitting by the door of her home, peaceably rocking her new infant son Snorri in his cradle, when a Native woman appears in the doorway. Gudrid, who has been described as not only beautiful but also intelligent, and someone who knows well how to behave, asks the Native woman for her name; says her own name first; and, when the Indigenous woman echoes her words, hospitably gestures to her visitor to come and sit down beside her.Footnote 41

The tranquil domestic scene ends abruptly, however, when a loud crash occurs outside (predictably, one of Karlsefni’s men has killed a native), and the woman promptly vanishes.

Here, it’s worth asking students: After generations of cultural transmission through which communal memories of the Vinland expeditions were narrated before they were set down in writing, who would have wanted an episode like this to exist, and why? What is accomplished, when a counterpoint to masculine bellicosity is created with a domestic setting in a woman’s home, with a mother rocking her baby? We can have students consider how women are made to carry symbolic significance for a society, including today – whether the symbolism is of a mother with an infant, or a woman wearing hijab, or a woman sporting battle fatigues.

The Sagas do not, however, essentialize women as peacemakers and consistently unlike violent men. GS portrays a sanguinary, murderous woman, Freydis – Leif Erickson’s (half?) sister – and ESR has a Valkyrie-like, pregnant Freydis terrify Native Americans by beating a naked sword against her bared breast. Often, students are quick to see that the portrayal of a bellicose Freydis is likely a foil for an idealized Gudrid, with both women lessoning us as to what women should, and should not, be for their societies.

Yet the episode staging two women from vastly different worlds – one Christian and representing the Latin West, the other presumably “pagan” and representing Native North America – who meet in the domestic setting of a woman’s home, with an infant close by, memorably remains. I suggest the episode can be offered to students as a narrative attempt – of however limited or fleeting a kind – to imagine a bridge across difference.

We should not exaggerate the success of this narrative attempt, of course. For instance, no Native tongue or speech is ever heard – Gudrid’s words only function as a kind of echo chamber, as the Indigenous woman repeats Gudrid’s words back to her, trying out the Norse syllables on her tongue. The sudden conclusion to the episode, moreover, truncated by male violence rearing its head once again, also does not portend a happy outcome for Europe’s encounters with Native North America.

But I work hard to find and help students see the possibility – even if it exists merely as a shadow, or a hint – of bridges across difference being imagined, perhaps as a thought experiment, within a text. While we aim to teach students critical thinking and incisive analysis that often require degrees of disenchantment, the production of an unremitting narrative of woe – unearthing a thousand years of othering, racism, exploitation, and domination in the textual record – can imbue in students a paralyzing, existential sense of dread and pessimism.

Finding moments like the episode between the two women, episodes which awaken curiosity and instigate discussion, then helps to interrupt, and ameliorate, any inadvertent production of an overarching, totalizing narrative that discourages, rather than encourages, idealism and action in the young.Footnote 42

It is also important to point to the role played by children in the Sagas. Exhibits at the L’Anse aux Meadows heritage project, overseen by Parks Canada today, rightly call attention to the unique role of Snorri Thorfinnsson, Gudrid’s infant and the first European child to be born in the Americas, so far as we know. But ESR also highlights two Native American boys who are abducted from their parents by the expeditioners, baptized, and taught language (i.e., Old Norse), and who then become native informants relaying ethnographic information that the saga duly narrates (102–103).

These kidnapped boys, students should be told, form an important historical-anthropological hinge, and not only in the way the saga relates. Scientists today have discovered that Native Americans and Icelanders share DNA in the form of the C1e gene element: a genetic inheritance shared by no other ethnoracial groups in the world (Race 270–271). While scientists rightly do not expatiate on the meaning of this shared genetic heritage – beyond suggesting that unrecorded intermarriage might have occurred in premodernity – students can see, with this genetic evidence, the historicity of the Sagas in an immediate and forceful way.

Most importantly, we can call attention to the myriad ways the Sagas can be used to counter white supremacists who see the Vinland expeditions as an example of early European supremacy. For white supremacists, “Hail Vinland!” is a rallying cry today that has displaced “Heil Hitler,” as supremacists imagine themselves as latter-day “Vikings” continuing an “ancient battle” in the Americas.Footnote 43 Students are tickled to learn that, contrary to white-supremacist wishful thinking, the Vinland Sagas depict Native American success, and European failure, as the would-be settler-colonists are routed from Vinland, and that thereafter, Native American genes spread to Iceland, complicating ideas of who has conquered whom.

Thanks to early encounters in North America, on which the Vinland Sagas open a window, white supremacists who are so proud of their white heritage are not even really as white as they think they are. This is something students discover when they take a course in early global literature.Footnote 44

Teaching Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali

To the question, “Where were the Black people in the Middle Ages?” the epic of Sunjata returns the panorama of a thriving, dynamic trans-Saharan Africa: a vast Black Africa alive in indigenous story traditions, visitor accounts by sojourners such as the world-traversing Moroccan Ibn Battuta, poetry, song, dance, performance arts, music, monuments, gold, sculptures, law codes, games, rituals, festivities, and treasure, among a plethora of expressive and material culture.

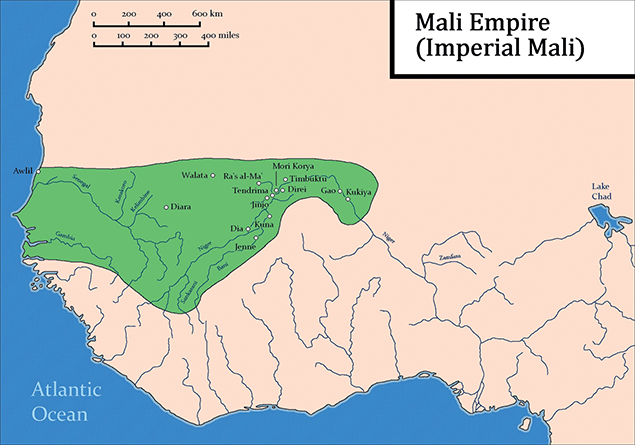

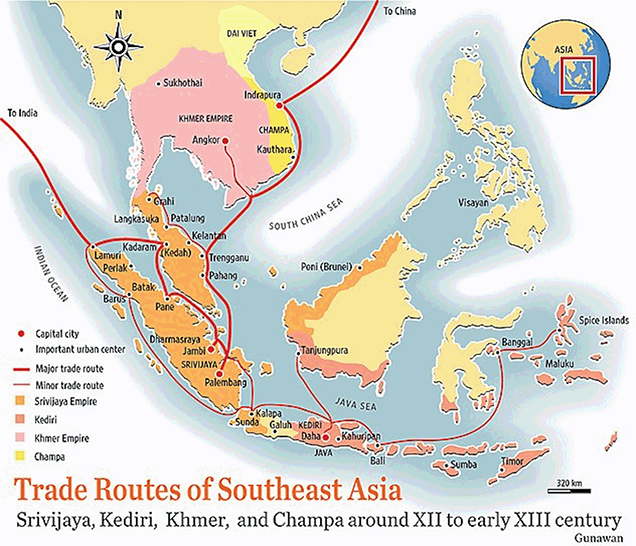

Students reading Sunjata,Footnote 45 the best-known of premodern African epics, learn that before there was a Wakanda in modern pop culture, there was the massive premodern Empire of Mali, stretching at its height from the Atlantic Ocean to the interiors of central Africa, encompassing nearly half a million square miles (Reference GomezGomez, African Dominion 220), preceded by the kingdoms of Ghana, and succeeded by the empire of Songhay (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Map of the Empire of Mali

Beyond West Africa, civilizations in Ethiopia, Nubia, the Swahili Coast, Zimbabwe, Benin, among others, have been excavated, studied, and offered to the academy and the public through books and articles, heritage sites, digital projects, and film and television documentaries that should, at their best, have made it unlikely, if not impossible, for questions like those addressed to Reference WhitakerWhitaker to be asked – yet knowledge of premodern Africa seems to have been siloed in ways that prevented it from reaching my colleague’s otherwise “well-educated” interlocuters.

Sundiata can thus be offered to students as a gateway to the rich cultures and societies of premodern Africa across siloes of knowledge, with journeys of discovery made through student presentations and reports, term papers, and collaborative projects that students can be asked to undertake.Footnote 46

Students are always impressed to read about the birth of an African empire, as recorded by its people over the centuries through their griots or jeliw: bard-archivists entrusted with the generational transmission of history, and whose ancestors played key roles as advisors and counselors to rulers of old. These bardic reciters-musicians-singers-historians-counselors descend from families who pass down their specialized, inherited knowledge and role across the generations as virtually a “caste” privilege.Footnote 47

Unsurprisingly, Sundiata is often students’ favorite text in my global literature classes. It is a text that should be taught with substantial contextualization at the outset. Students should understand something of how oral traditions transmit knowledge – and why there may be formulaic repetitions, inconsistencies, or even contradictions in whatever version of Sundiata they read, narrated by contemporary jeliw with all their individual preferences, after oral transmission for hundreds of years, and set down in writing by transcribers, translators, and editors.

They should also understand that numerous variants of the epic exist – by a 1997 count, there are sixty-four published versions (in addition to oral performances by living jeliw) – and the translation they read is but one version of the multi-variant epic of Old Mali, and other variants may offer details of plot and treatment differing greatly from the version they read, even when a core content exists (Reference GomezGomez, African Dominion 390–392 n.2).Footnote 48

These substantial caveats do not seem to deter instructors or students, however, and the epic is encountered in full or abridged form in many kinds of courses. Berkeley’s ORIAS websites, designed for K-12 educators, testifies to the epic’s enduring popularity: https://orias.berkeley.edu/resources-teachers/monomyth-heros-journey-project/sundiata

The texts listed in Section 4 are the most often used English translations of the epic in classroom teaching: the Longman’s/Pearson’s translation by D(jibril) T(amsir) Reference Kouyaté and PickettNiane and G. D. Pickett, transposed and edited from the narration of Mamoudou Kouyaté, who claims descent in the lineage of the Reference Kouyaté and PickettKouyatés serving Sunjata’s royal Keita line; the Hackett translation by Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradDavid C. Conrad, transcribed from an abridged oral narration by Djanka Tassey Condé of the Condés of Fadama; and the Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson translation (Epic), performed by the jeli Fa-Digi Sisòkò, and recorded, transcribed, and translated in stages by an African-western team of six collaborators coordinated by John William Johnson.

My preference is to teach the Reference Kouyaté and PickettKouyaté-Niane-Pickett translation, “the most influential single version of the story” as base text, in part because it has the fullest rendition of the epic’s key materials, while occasionally interleaving details from Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradCondé-Conrad and Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson to discuss alternate traditions and story details (Reference BelcherBelcher 92). Instructors who want to stress the performance aspects of contemporary oral narrations of the epic may prefer to center the Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson or Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradCondé-Conrad translations instead.

The Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradCondé-Conrad abridgement (which contains omissions of many passages that are summarized for readers by the translator) features a chatty jeli-narrator who intrudes modern musings ranging from his thoughts on race (“Americans are the best of the white people” [98]) to repeated mentions of muskets, guns, and gunpowder, that is, nonexistent technology in premodern Mali (e.g., 29, 55, 64, 69, 85, 92, 103, 109, 115, 119).Footnote 49 A colleague who has taught the Norton anthology extract excerpted from Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradCondé-Conrad reports that students became confused by, and skeptical of the narrator – whose proclamations about cities (“if Paris was ever built by anyone, it was God”), musings on Black–White relations (“God made blackness after he made whiteness”), and views on women (“No matter how proud a girl is, once you call her ‘beautiful,’ she will soften”) – are admittedly odd, to put it gently (100, 4, 23).

But the Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradCondé-Conrad translation is highly interesting as a rendition of orality, featuring a jeli with a big personality and many opinions, responding to his audience in a lively, sprawling way – catering, for instance, to avid interest in family genealogies of not-necessarily-central characters who are ancestors (while omitting core events of the epic), and interpolating modern topics and his personal opinions to bring alive the dynamics of performance. Dramatizing how orature works, this translation would be excellent for courses on performance and the dramatic arts. It also offers engaging material for courses on medievalism.

Still, for those interested in oral performance as a dynamic process, even in a written text, the Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson translation is likely a better choice. This is a word-for-word transcription of a four-hour performance of the epic in verse (with rare prose interpolations by the translator) recited by a jeli whose cadences are beautifully caught in the transcription – a jeli, moreover, who has an assistant-apprentice commenting on his recitation throughout, in a call-and-response dynamic well-captured in the text.Footnote 50 Much is opaque in the narration, however, and Johnson’s copious notes are absolutely essential to study carefully, for students to make sense of what they are reading.

Delightfully, the jeli-narrator in Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson uses ideophones to convey actions, like making a tearing sound, “fèsè fèsè fèsè!” as Sunjata’s dog rips Dankaran Tuman’s dog to shreds (Epic 64), or a falling sound, “gejebu!” when Sogolon drops to her knees (Epic 61), and a rushing sound, “birri birri birri” as Susu people pursue Fakoli, and “yrrrrrrr!” when they attack him (Epic 61). The liveliness of the orature communicates a sense of immediacy, a sense of you-are-there, that is unmatched. This jeli-narrator contradicts himself or loses the thread when he is tired; he takes breaks, then forgets where he left off. For students of ethnography, folklore, anthropology, drama, orature, and performance arts, the Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson translation is superior.

Graduate students might forge a path through the copious notes more easily, to understand what’s happening in the Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson narrative line-by-line, and a graduate class can usefully read Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson’s fuller companion volume, Reference SisòkòSon-Jara: The Mande Epic, Madekan/English Edition with Notes and Commentary as base text. Indeed, if an instructor can afford to spend several weeks on Sunjata, a comparison of Reference Sisòkò, griot-jeli and William JohnsonSisòkò-Johnson, Reference Condé, griot-jeli and ConradCondé-Conrad, and Reference Kouyaté and PickettKouyaté-Niane-Pickett would yield many fruitful discussions on the role of narrators and audiences, translations, and the retrieval of stories across time.

The Reference Kouyaté and PickettKouyaté-Niane-Pickett version (henceforth, Reference Kouyaté and PickettSundiata), is compact, yet highly detailed and vivacious, and a pragmatic choice that readily allows us to approach the diegesis as a set of key stories within a central epic framework – a narrative tree – from start to finish, by a griot who substantially refrains from foregrounding his personality, or indulging in digressions.Footnote 51 Students immediately recognize what narrative trees are like – acclimated as they are to contemporary popular culture, where narrative trees proliferate (e.g., the capacious Star Trek universe) – so that changes in details across alternate versions of stories tend to excite questions of why, which can prompt lively discussions.

Michael A. Gomez’ recent scholarship guides us to see the epic as narrating the formation of an African empire out of earlier regional polities in the thirteenth century, while establishing the geographic boundaries and constituent territories of that empire at its most powerful expanse and greatest height in the fourteenth (“Epic;” African Dominion, chapters 5–7). Simultaneously, Gomez points to how Islam, a global religion, starts to take root among the Mande/Mandinka, embedding itself in social structures and spreading its influence.Footnote 52

We thus see early globalism in West Africa taking the form of global religious forces that arrive, and negotiate local and regional cultures and societies, transforming political structures and human relations, personal identities, and producing new articulations of power.

Signs of Islam are everywhere in the epic. We learn that Sunjata’s royal family, the Keitas, impressively claim descent from Bilal ibn Rabah, the Black African companion to the Prophet Mohammad, who occupies the esteemed role of the first muezzin or summoner of the faithful to prayer (2). Princes of Mali make the hajj (2). Sunjata wears the robes of “a great Muslim king,” and Islamic jinn populate the narrative alongside indigenous deities (73, 70–72).

Traditional beliefs, practices, and forces do not disappear, however, but transact an intertwining coexistence with Islamic beliefs, practices, and forces; and scholars invariably point to the religious syncretism the epic exhibits. Animal sacrifices are made to Islamic forces like jinn, but also to indigenous deities; individuals may possess pre-Islamic occult forms of personal power (nyama, dalilu) that are inherited or achieved, but can also possess Islamic gifts of grace and blessings (baraka); and merchants who spread Islam jostle alongside the powerful old hunter-guilds and smiths of pre-Islamic society (Reference GomezAfrican Dominion 91).

Revealingly, one outcome of globalism-as-religion is a transformation in leadership roles earlier occupied by women: