In the interwar 1930s, in an outlying district of the British Gold Coast colony (now Ghana), itself on Britain’s imperial periphery, a group of activist officials and African traditional elites created a self-sustaining community-based health network. The region was the Northern Territories Protectorate, a third of the colony’s total area and home to almost a third of its people, but enduringly marginalized within the colonial and postcolonial states. During the indirect-rule austerity which followed the Great Depression from 1929, a system of village clinic-dispensaries was built by “Native Authority” (NA) chiefs and the communities whom they represented with varying degrees of legitimacy. Staffed by locally trained health workers and sustained by communities themselves with little central support, the new dispensaries were an immediate success. They provided treatment and medical advice to thousands of outpatients, often at higher rates than better resourced facilities in the colony’s wealthier south. The program was explicitly intended to address what local officials and community leaders understood as a central underlying determinant of widespread poor health in the north: that the region and its peoples were seen as a low-cost migrant labor reserve by central governments in Accra, and were therefore accorded little political importance in the colony’s healthcare plans or allocations of central funds.

Despite its success, the north’s rural dispensary program was dismantled in the late 1930s. After 1945, a new service was created, also attempting to circumvent the political and economic exclusion which increased health problems in the north. The Medical Field Units (or MFUs) grew into a far-reaching mobile community health service, staffed by local employees with little formal education, serving extensive rural areas that lay beyond the reach of both the colonial and early post-independence states. With reduced dependence on funds from the central government, and a training program which passed relatively complex knowledge of clinical and public health methods directly from one fieldworker to another, the MFUs were to some extent self-sustaining, independent from the fixed facilities and patronage networks of the national health system. Their successes were recognized by the first government of independent Ghana and after independence in 1957, the MFU program was expanded countrywide. This ad hoc service, created in response to the political neglect and limited funds that underpin poor healthcare at the margins, had become a national healthcare institution.

Over the decades of instability which affected many African countries in the 1970s and 1980s, shaped by the Cold War, global oil shocks and structural adjustment, Ghana’s Medical Field Units became central to the continued provision of basic health services, under conditions of collapse in other parts of the national health system. But adjustment brought ideologies of reduced welfare and severe austerity and the program was closed down in the early 1990s, after a half-century of success which is evident in state documents, World Health Organization (WHO) archives, and community oral histories across Ghana.

This chapter examines northern Ghana’s Native Authority dispensaries and the Medical Field Units as programs which embodied many ideas and practices of social medicine over the twentieth century, although the term was rarely used by the actors themselves. The evolving terminology and central historical figures of “Social Medicine” were largely absent, but these Ghanaian programs were produced by similar ideas and practices (regarding underlying determinants of poor health, community health needs, and just distributions of care) as many contemporary, self-identified social medicine movements elsewhere. In this chapter, “social medicine” is used as an analytical category, comprising these fundamental ideas and practices. The chapter relates the evolution of the MFU program to social histories of individual advocacy, healthcare reforms from colonialism to independence, and shifts in internationally circulating economic beliefs regarding the role of welfare and the state.Footnote 1 African countries have often been represented as places in need of social medicine, suggesting a diffusion of ideas from somewhere else. This chapter discusses locally inflected African social medicine programs which endured for decades, complicated by their origins in the administration of the colonial periphery. Their development calls the notionally monolithic character of colonial medicine into question. This was the case for northern Ghana, where a lack of attention from central colonial governments, who saw the region as unprofitable, meant that there was sometimes more scope for alternative institutional ethics, notions of solidarity, and understandings of the determinants of poor health.

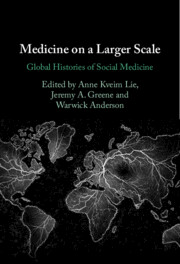

This analysis is based on sources from Ghanaian and WHO archives, and community oral history interviews carried out in Ghana during 2015–22. I also use interviews with current and former Ghanaian health officials and national planners and retired health workers who held positions from c.1960 to the present, notably in community medicine and rural public health. From these sources, some key observations emerge: about the role of the political and economic margins as an enduring test-bed for social medicine’s ideas and about the cyclical creation, decline, and recreation of similar social medicine and community health programs on these margins, in places like northern Ghana (see Figures 13.1(a)–(d)).

Figures 13.1 (a)–(d) Community health facilities in rural Ghana, 2018. Many of these frontline health facilities in Ghana have grown on the same sites as the Local Authority health system of the 1930s, having changed hands with national- or mission-based ownership. They embody many of the same aspirations, at the necessary convergence of social and community medicine.

Native Authorities and Community Health, 1930–9

It is important to understand the north’s relationship to Ghana’s centers of political and economic power, comparable with circumstances that have fostered the emergence of social medicine advocacy elsewhere. Separated from the coast by the West African forest belt, the north’s weather, ecologies, and agricultural potentials were (and are) substantially different to the rest of the country. Unlike southern Ghana, the north has no cocoa production, the crop most valued and supported by colonial and postcolonial governments. When attempts to force cultivation of alternative export crops like cotton were unsuccessful, the colonial government designated the north as a migrant labor reserve from the early 1900s, supplying low-cost workers to the gold mines and cocoa farms of the south.Footnote 2 Migrant labor came to be seen as the “principal asset of the dependency” and by the 1920s, many of the region’s work-capable adults migrated annually as low-cost laborers.Footnote 3 Colonial-era neglect also stemmed from the north’s lack of political influence. With little access to the central government at Accra, which imposed policies to restrict the development of northern education and infrastructure, the region was kept at a political arm’s length over the colonial period.Footnote 4 There were few opportunities for African advocates or northern officials to counter the perception of the colony’s governing elites, who argued that the north and its peoples were of “negligible” importance and that the region “imposes a burden upon the Gold Coast for which it makes no adequate return.”Footnote 5

These problems persist into the present. The north has been a periphery of both the colonial and postcolonial state: in terms of administrative attention and spending from central government, access to education and economic opportunities, and relative political influence.Footnote 6 Following its annexation in 1903, poverty, disease, and poor living conditions appeared increasingly regularly in descriptions of northern communities, contributing to an enduring public discourse which has represented northerners as unhealthy, second-class citizens. By the mid 1920s, orientalist official reports of “the wild tribes” who “leapt out with twanging bows and bloodcurdling yells, in apparent ecstasies of joy,” had been replaced by “the immigrant labourer from the North, who generally reaches the cocoa areas in poor physical condition and is often diseased.”Footnote 7

These were the structural conditions faced by northern societies under colonial rule and since. Beyond economic privation and resulting poor health, however, the north’s peripheral situation shaped healthcare in less expected ways. Necessity was often the mother of invention, when long-term underfunding compelled local officials to find novel answers to problems of health provision. These innovations included Native Authority community healthcare from the 1930s; the Medical Field Units, which operated for decades before and after independence; and the later co-optation of vertical donor-funded campaigns (notably the Carter Centre’s guinea-worm program in the 1980s–90s) to serve broader public health needs. Neglect and underdevelopment created the moral basis for sustained healthcare advocacy by northern communities and officials, while allowing new local health initiatives to proceed with little central oversight.

This was evident in the creation of the Native Authority clinic-dispensaries scheme in the 1930s. The role of “Native Authorities” and indirect rule in colonial Africa has been a focus of critique, concerned with the illegitimacy of the institutions created when Britain began governing via its preferred “traditional” elites.Footnote 8 But there were other aspects to this transition. In the colonial north, Native Authorities became relatively effective activists and managers of health services, prepared to allocate resources to areas which been neglected under centralized British rule. The NAs were not dependent on the Accra government’s largesse. They had their own treasuries, were able to raise and spend revenues locally, and were staffed by northerners, who were more responsive to health problems affecting their communities. Following their establishment during 1930–4, health became an immediate priority of the Native Authorities. Their central achievements were the rapid creation of a rural sanitation program to improve water quality and a network of village dispensaries and treatment centers were set up providing health surveillance and education, drugs, and outpatient treatments for common diseases.

These involved significant investment in local infrastructure by northern communities and from 1930–5, NA spending on new health infrastructure greatly exceeded the north’s total annual medical budgetary allocations from the central government at Accra, which preferred to allocate funds for short-lived campaigns against diseases that threatened the southern labor supply (notably sleeping sickness).Footnote 9 By 1938, there were 16 large dispensaries, many smaller treatment centers, and a training program for local health workers. The north’s native authorities contributed to schemes for training “village overseers,” in charge of preventive rural sanitation, and the construction of a much larger School of Sanitation.Footnote 10 They also developed a course for NA “dressers” in the regional capital, Tamale. After eighteen months of training, the dressers’ work included treating yaws, sleeping sickness, round worm, scabies and ulcers, basic wound dressings, sterilization techniques, and home nursing or referrals to colonial medical officers. NA “dispensers” ran larger facilities. They were trained in similar techniques and in the provision of an expanded range of drugs, including subsidized quinine tablets and the use of new sulfonamide antimicrobials during regional meningitis epidemics.Footnote 11

Supported by activist officials in the north’s colonial administration, the NAs began to address other problems of underdevelopment related to health, including expansion of clean water supplies. These British officials, many of whom remain anonymous in colonial files, were public in their criticism of the Accra government’s “belated realization” that clean water was a requirement for improved northern health, at a time when activism from colonial officials was relatively uncommon. They pointed out that in 1937, the north’s Dagomba and Mamprusi Native Authorities had jointly spent £600 to employ a private engineer to develop proposals for clean water provision in their districts.Footnote 12 The north’s various Native Authorities allocated £9,355 that year toward expenditures on preventive “health” initiatives for village sanitation. This far exceeded comparable funding from the government at Accra, which had allocated only £664 for village sanitation across the entire Northern Territories that year.Footnote 13

The Native Authority health system was an immediate success from its creation in the early 1930s. With community-funded preventive sanitation, and clinical facilities staffed by northerners, its services were intended to compensate for the region’s marginalization within the state and NA healthcare was soon recognized as an effective model by medical officers around the colony. This public success emboldened the region’s medical and political officers in voicing direct criticisms of the central government. The protectorate’s chief commissioner, W. J. A. Jones, wrote that:

The Northern Territories have seen the greatest advance in administration so far recorded in the history of the Gold Coast. Between the years 1902 and 1932 there was little or no alteration in the legislation affecting the lives of the people of the Northern Territories. This fact discloses the attitude of Government towards the people of the Protectorate. They were regarded as … fit only to be hewers of wood and drawers of water for their brothers in the [southern] Colony.Footnote 14

Other officials noted the “tremendous increase in the provision of facilities for medical treatment, improvement in village sanitation, and water supplies” as a result of NA initiatives, and attributed a significant fall in the colony’s total number of out-patients to the work of the northern dispensaries.Footnote 15

In the region’s annual report for 1935, a district commissioner observed that, “The progress made by the Native Authorities has enabled them to obtain benefits which they would probably never have received if they had waited on Government generosity.”Footnote 16 This foundational aspect of social medicine – an engagement with structural factors determining local health outcomes – is evident in many sources on health in the colonial north. The north’s NA system was not simply a facade for the continued exercise of direct rule by British officials. Nor did it devolve into the “decentralised despotisms” assumed by some critiques of indirect rule.Footnote 17 From its creation, the NA health system was co-produced by northern communities, traditional leaders, and a small number of British officials in the region and almost entirely funded by the communities themselves.Footnote 18

Medical Field Units and Ideas of Health and Development, c.1945–57

The colonial north’s NA health system operated for only twenty years, despite its clear successes in improving community health and circumventing distributional inequities between the region and the wealthy south. In 1934, the north’s chief commissioner had written, “it is to be hoped that these endeavors of the people to help themselves will be rewarded by the grant of generous assistance, by the central government or from the Colonial Development Fund.” But no additional health funds were allocated to the region during the 1930s, perhaps because of the success of community-led NA healthcare. There was political resistance by the late 1930s, with efforts to restrict NA health services because they were seen as having expanded beyond supervision by the Accra government. Despite heated advocacy from communities and officials, northern Ghana’s NA health system was shut down in the early 1950s, when the first independent government sought to centralize control of national healthcare and standardize training, considered more important than sustaining independent services in the north. Reflecting on colonial government resistance to northern community health, an activist official in the Northern Territories observed with apparent irony: “Perhaps it is a matter for congratulation, that we have prevented them from running the risk of having a fall by trying to walk, before they can creep properly,” with “creep” connoting obeisance to Accra.Footnote 19

This would be repeated several times over the twentieth century: a northern community health initiative, designed under conditions of privation, would become a blueprint for services across Ghana, and risk becoming a victim of its own success in the interests of maintaining centralized control. The awareness of distributional inequities informed several subsequent northern health initiatives, which also embodied the ideas and practices of social medicine and were closed down in their turn. In 1938, a British official noted that health innovation of this kind was necessary for the region precisely because of persistent economic neglect: “an isolation which is inevitable, so long as the [north] is separated from the seat of Government by so valuable a crop as cocoa.”Footnote 20

With the decline of NA healthcare from the late 1930s, northerners requiring treatments beyond traditional herbalism were compelled to travel long distances to a handful of minimally funded government hospitals. Colonial medical budgets for the region in this period were allocated almost entirely to sleeping sickness control, seen as an economically important disease affecting the southern migrant labor supply.Footnote 21 Distributions of health infrastructure remained evidently unjust, driving continued advocacy on the part of northern communities and local officials. After 1945, local advocacy led to the creation of a new mobile medical service, intended to address the same problems. The Medical Field Units became one of Ghana’s most enduring healthcare institutions, providing rural services across the country. It operated into the early 1980s and its northern fieldworkers became a crucial ark of local health knowledge across the independence divide. The MFUs were created in what some have seen as the “developmental” phase of colonial rule, in which Britain invested in headline infrastructure projects partly intended to improve its public support in the colonies, while privately also seeking to reduce overseas expenditure in the context of post-war austerity. With decolonization increasingly imminent, in 1948 the Gold Coast Medical Department published the 10-Year Development Plan, which proposed that: “the future shape of medical services in the Gold Coast depends on a choice that must be made at this stage, between the rival claims of preventive and curative work. To aim at providing services satisfactory in both respects, for the entire country, is out of the question.”Footnote 22 Relatively little had been done to develop preventive medical capacity under colonial rule in the Gold Coast, and the transition from colonial to independent rule (c.1948–57) brought an increased focus on building hospitals and urban clinics, because curative medicine was believed to generate more immediate political support than longer-term prevention.Footnote 23

With little central funding for preventive medicine in the north, the MFUs were created in the late 1940s with ad hoc resources available on the ground, by fusing remnant personnel from older northern treatment campaigns (against yaws and sleeping sickness) into a service designed to provide wider health services to rural communities. The MFUs did much of the same disease surveillance and treatment that characterized other mobile medical services in Africa, including the General Mobile Service of French West Africa, the Belgian FOREAMI, and the related MFUs of Nigeria.Footnote 24 Beyond this general remit, however, the foundational planning of northern Ghana’s MFUs was focused explicitly on social and economic inequities which gave rise to malnutrition and endemic disease. The MFUs were founded by an Australian medical officer, B. B. Waddy, who argued that increased disease and economic decline were produced by insufficient government support for northern communities during the planting season, when stored food supplies were lowest, disease rates were high and many migrant laborers were absent. He proposed that:

the welfare of people in much of the Gold Coast turns on this vital period annually … even slight exaggerations of the difficulties may cause eventual famine, while amelioration may result in better harvests and a consequent progressive improvement in health and nutrition. With food to sell, the standard of living rises quite obviously … To achieve such a result with the limited resources available, the attack must be made first on those conditions.Footnote 25

Waddy emphasized that this welfarist approach was central to the creation of the MFUs, concerned with precedent conditions that give rise to increased burdens of local disease.Footnote 26

As with NA healthcare in the 1930s, the preventive, structurally aware approach to healthcare that Waddy described would seem to embody some key tenets of social medicine, whether he understood himself to be working in its traditions or not. Both programs aimed to alleviate or circumvent aspects of political and economic neglect unrelated to the immediate disease environment, in circumstances where there was little capacity to effect political change from the center. In this sense, both are comparable with the Pholela Community Health Centre in 1940s South Africa.Footnote 27 The northern Ghana health initiatives discussed above are similarly problematized by their origins on the colonial periphery, as programs co-created with colonial officers at the edges of an exploitative imperial system. It can also be argued that in many places at the rural periphery, with little state infrastructure, economic opportunity and political access, there is a necessary confluence between politically “Social” and practically “Community” Medicine, to the extent that the two are practically coterminous. At these rural margins, beyond advocacy and critique and in the relative absence of integration with the kind of social worlds which international advocates of social medicine might have conceived of (linking people through shared experiences of the state and wage labor), in these contexts “Community Medicine” often comprised all of the practicable interventions which Social Medicine practitioners could bring to bear.

Other forms of “social medicine” were understood by central British administrations in late colonial Africa. For example, in a 10-year Development Plan for Gold Coast health services, published in 1948 but never implemented, “Social Medicine” was proposed as one division of a reformed colonial health service, along with curative medicine, preventive medicine, nutrition, and laboratory services. A Social Medicine division would deal with “maternity and child welfare, school medicine, and dentistry” and planned to use women health visitors as a way of gaining community trust for increased preventive services over time.Footnote 28 Coming from the administrative center, these developments in the pre-Cold War 1940s may have been shaped by the diffusion of ideas from the 1937 Bandung Conference on Rural Hygiene, the rural health programs of the Rockefeller Foundation (which funded concurrent yellow fever research in West Africa), and perhaps by the work of Andrija Štampar and Henry Sigerist. Contemporaneous developments in social medicine may well have been known by those involved in the creation of the NA and MFU programs in the colonial north, although none are referenced in the available sources. From the 1940s “developmental” phase of colonial rule, there were other resources beyond the literature on health – related to broader discussions around labor and social welfare – which could be used to make arguments about the underlying determinants of poor health in colonial northern Ghana. Britain’s 1929–45 Colonial Welfare and Development Acts offered a rhetorical resource for criticizing the colonial state using its own terms.Footnote 29 The idiom of development, and the moral language the Acts contained, were influential in shaping advocacy for health programs which aimed beyond the “great campaigns” and curative preferences of most colonial medicine.Footnote 30

Independent Ghana: Socialized, Community, and Primary Health

At his inaugural Christmas address in 1957, independent Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, said:

My first objective is to abolish from Ghana poverty, ignorance and disease. We shall measure our progress by the improvement in the health of our people; by the number of children in school and the quality of their education; by the availability of water and electricity in our towns and villages … The welfare of our people is our chief pride, and it is by this that my Government will ask to be judged.Footnote 31

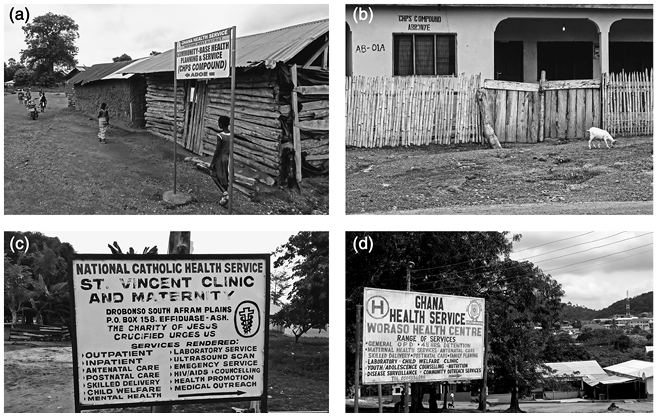

Nkrumah’s Convention People’s Party (CPP) welfare policies set out to create a socialized health service on the British model, funded by general taxation. Fees for drugs and outpatient services were ended and government health workers were prohibited from charging for treatments away from state facilities.Footnote 32 New clinical and training infrastructure expanded across the country and there were attempts to integrate traditional healers into Ghana’s health system.Footnote 33 From 1964, there was a policy shift toward the new paradigm of “community health” promoted internationally by the WHO, emphasizing basic rural healthcare and preventive medicine.Footnote 34 Ghana endorsed this model relatively early, as part of a global movement focused on community needs and primary care, aspects of social medicine which would culminate in the call for “a new global economic order” of the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration. Nkrumah’s government ran various programs oriented toward broader societal health, including national health education initiatives and a family support program which reprised late-colonial social medicine plans for the country, sending hundreds of women health visitors to rural districts to monitor community nutrition (Figures 13.2(a)–(c) are examples of health documents produced during this transition).Footnote 35

Figures 13.2(a)–(c) Internal documents, organizational structures, and reports of the Medical Field Units in 1952 and 1961 across Ghana’s transition to independence. Created to address feedback loop between social conditions, nutrition, and poor health, the Units persisted from the 1940s into the 1980s as the first line of rural healthcare and disease prevention in Ghana.

However, these independence-era programs were short-lived. Decolonization had relocated Ghana from the imperial to the global economic periphery, in the context of Cold War clientalism. As the world’s leading exporter of cocoa in the 1950s and 1960s, there were significant foreign reserves to fund the expansion of socialized health and welfare services. But the situation deteriorated from the early 1960s. As Nkrumah’s government joined the Non-Aligned Movement and partnered with several socialist states, Western cocoa buyers increasingly moved their purchasing to neighboring Côte d’Ivoire under the French-aligned government of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, during a period of global cocoa overproduction. These changes eroded the economic foundation of Ghana’s independence-era health reforms, while restrictions on private enterprise generated resistance from Ghanaian elites (notably doctors who had been restricted from private practice). In 1966, Nkrumah was overthrown by West-aligned military officers who governed as the National Liberation Council. This began a twenty-year period of rapid, unstable political transition, often by military coup, which stalled plans to expand health infrastructure, and resulted in a gradual accretion of authority by transnational health organizations and NGOs, particularly in the management of rural care.

The period 1957–66 was Ghana’s only experiment with extensively socialized healthcare. But the Medical Field Units persisted during Nkrumah’s time and beyond. In the early 1950s, the number of mobile teams was doubled and MFU personnel were tasked with monitoring, preventing, or treating practically all of the north’s principal rural health problems, including village sanitation, health education, general injuries, and obstetrics (to the extent that these were unaddressed by traditional medicine), as well as endemic and epidemic diseases including meningitis, onchocerciasis, guinea worm, tuberculosis, yaws, leprosy, malaria, smallpox, bilharzia, hookworm and other helminths, and malnutrition. At independence in 1957, Ghana’s new Director of Medical Services observed that the north’s MFUs were “of greater service to the community than any hospital, however large.“Footnote 36 Recognizing the value of a mobile, community-oriented medical service for reaching peoples who had received little colonial-era care, the CPP government expanded the service across the country, preserving its remit but greatly increasing the national scope of MFU activities.Footnote 37 Although technically based within the Ministry of Health in Accra, the headquarters and training school remained in Kintampo, a small town on the northern edge of Ghana’s rainforest belt, where MFU candidates, “accustomed to working in primitive surroundings and familiar with local languages,” gathered for courses in field medicine. There are comparisons to be made with the later “barefoot-doctors” movement in 1960s China. Most learning took place by direct instruction between successive cohorts of MFU members, as opposed to book-led instruction from medical professionals, and MFU members were recruited for their local knowledge, community relations, and physical endurance, rather than formal education; many were illiterate or had a basic primary school education. With this adaptive approach, however, the MFUs were able to sustain and transmit the knowledge necessary to perform relatively complex clinical and diagnostic tasks, including field microscopy and forms of surgery, in places beyond the road network and bureaucratic reach of the state.Footnote 38

Beyond frontline care and prevention, Ghana’s MFUs also functioned as a crucial ark of health knowledge and community relations across the independence divide and during the instability which followed the overthrow of Nkrumah. Much institutional knowledge of rural health problems was lost when British health workers left the Gold Coast en masse in the 1950s, having resisted the training of African personnel who might replace them, and problems persisted after independence when southern Ghanaian medics refused to take up vacant posts in the rural north.Footnote 39 Dr. Sam Bugri, who became the north’s Regional Director of Health in 1984, recalled that for decades after independence, district physicians relied on the formally untrained staff of the MFUs as a repository of medical knowledge. Among other things, MFU personnel trained new hospital physicians in the relatively high-risk technique for lumbar puncture, used by MFUs to test for meningococcal meningitis in the field:

We had a team they called the Medical Field Units – they started way back in the colonial times … At first they focused on the North, and they were well trained. I learned how to do lumbar puncture from them, not from medical school. They could screen a village within a short period for any diseases that you want. We had a feeling that there were very few doctors who are comfortable with doing lumbar puncture. So we insisted that all doctors in the field would see this. And these MFU people were not highly educated. But they taught them how to do it safely, and very accurately – they did it with ease.Footnote 40

Over five decades, through economic downturn and successive political upheavals, the widely remembered work of the MFUs stands as a testament to the role played by a group of “uneducated” northerners, operating in difficult environments beyond the reach of the state, in shaping independent Ghana’s public health.Footnote 41 Across overthrows of successive Ghanaian governments during 1966–82 and the severe economic shortfalls experienced by most African states in the 1970s as global oil shocks destabilized poorer countries at the global periphery,Footnote 42 the MFUs played an increasingly central role in the maintenance of community-oriented health services and the preservation of medical knowledge. These disruptions diminished Ghana’s record-keeping capacity and relatively few government documents were archived for these years, including on national health. Community oral histories suggest that in poorer rural districts, the MFUs were often the only persistent state health service from the 1940s to the early 1980s, offering locally adapted healthcare and screening and participating in transnational campaigns against smallpox and onchocerciasis. Reports from the WHO Smallpox campaign in the 1970s reveal the extent to which eradication in Ghana depended on the MFU network.Footnote 43 As other divisions of the national health service contracted or ceased operations, the Medical Field Units became “the pride of the Ministry of Health.”Footnote 44 WHO consultants posted in Ghana consistently remarked on the importance of the MFUs under the economic conditions of the 1970s, observing that they offered the best way of “providing as much coverage to the population as is possible within the limitations of available staff and resources.”Footnote 45

National Planning and International Health

Under the unstable conditions previously discussed, it is surprising that the Medical Field Units remained in place and relatively unchanged from the colonial 1950s to the mid 1980s. Beside their practical successes, the MFUs were also sustained by the health planning orientations of the Ghanaian state, produced by Ghana’s situation in the world of international health and particularly its relationship with the WHO.

The history of pre-Adjustment national health planning in Africa is an emerging area of research, discussing the interplay between domestic visions for health reform and ideas circulating internationally.Footnote 46 After independence, Ghana drew on a heterodox range of influences in the formulation of national health policy. Early influences included Britain’s late-colonial “10-year plans” and the 1953 Maude Commission Report on the Health Needs of Ghana.Footnote 47 Nkrumah’s first independent health plan was drafted with advisors from the Israeli labor movement and, from the early 1960s, his government turned increasingly toward the socialist world as a partner and source of planning advice. After the coup d’état in 1966, the military National Liberation Council set out to “divest the state from the socialist programs pursued under Nkrumah.”Footnote 48 When a second coup brought the left-leaning National Redemption Council to power from 1972, it conversely expanded state welfare and health subsidies and restored relations with the socialist world, developing bilateral relationships for trading medical goods which persisted into the late 1980s.Footnote 49

With stasis or collapse in many areas of Ghanaian healthcare from the 1960s–80s, what sustained the Medical Field Units across these political shifts? They endured in part because the underlying inequities which the MFUs were created to address had remained constant or increased: the economic marginalization and resulting disease burden of rural communities, out of reach of state health infrastructure. But the MFU program was also sustained by the persistence of social medicine as an idea in international health. A strong Ghana–WHO relationship, across different governments, acted as a conduit for new terminologies that rested on the same fundamental orientations. From the 1950s to late 1970s, Ghana’s medium-term national health plans comprised successive proposals for expanding what were variously called “Social,” “Community,” “Basic,” and “Primary” health services, often drafted in collaboration with the staff of the WHO’s Division for Strengthening Health Services.Footnote 50 While the terminology changed, social medicine’s enduring currency in international health thinking and support for its ideas within the Ghana–WHO relationship may have helped to sustain the MFU program across different political regimes.

Adjustment and the End of the MFUs

The Medical Field Units were created to provide healthcare under conditions of economic and political marginality, many years before the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration. They were first designed to secure community health during the vulnerable northern planting season when food stocks were low, migrant labor was absent and there was no state support, with the aim of increasing harvests, productivity and health in the longer term. Although it is unclear whether the MFUs were influenced by the development of social medicine elsewhere, the program was likely sustained by the internationally conducive climate for social medicine discussed above, adapted by health planners in Ghana.

All this changed soon after 1978, a historical high-water mark for the primary care and social medicine movements. From the early 1980s, the community-oriented mobile health services of the MFUs were undermined by centralizing budgetary micromanagement under Structural Adjustment and by competing NGOs, Christian Health organizations, and other external actors that adjustment had brought to the country. In 1983, Ghana became the first African state to accept World Bank-/IMF-mandated restructuring as a condition of development loans, after debt crises reduced national healthcare spending by almost 80 percent during 1976–80.Footnote 51 In some analyses, Ghana’s adjustment program has been seen as an outstanding success. Gareth Austin suggests that the country was “one of the two most successful cases of structural adjustment in Africa.”Footnote 52 Arguments of this kind are often based on aggregate growth, without regard to distributional effects, although adjustment in Ghana arguably also failed on its own macroeconomic terms.Footnote 53 Foreign debt more than doubled between 1983 and 1987 and costs of structural adjustment austerity were consistently passed to peripheral regions and the rural poor, whom the IMF and World Bank had cast as its principal beneficiaries.Footnote 54 Rising poverty resulted from trade liberalization and currency devaluation after 1983 and severe cuts to spending on health and education drove many destitute rural communities to migrate to informal settlements around southern cities.Footnote 55

In healthcare, World Bank purchasing restrictions meant that the country completely ran out of essential medicines at several points in the 1980s, including all tuberculosis treatments and antibiotics like penicillin and ampicillin.Footnote 56 Cost-recovery measures were imposed at government health facilities, requiring full advance payment before treatments or drugs were supplied.Footnote 57 This led to a situation in which an estimated 69 percent of Ghanaians were unable to afford state care, with many people turning to traditional herbalism or forms of faith healing.Footnote 58

Under these conditions, there might seem to have been a clear need for a low-cost, scalable model for maintaining basic health services. But Adjustment-era centralization of health authority was antithetical to a service like the MFUs, which was inherently decentralized and unpredictable by design, intended to address shifting rural health needs away from state infrastructure. The MFU program may also have been affected by changes in health accounting practices which took place concurrently with adjustment from the early 1980s, given the difficulty of calculating a neat return-on-investment for a self-organizing service operating in deep rural areas beyond regular inspection.Footnote 59 The MFU program ended in the mid 1980s and it was intended to be replaced with fewer, formally trained “technical officers” at fixed district health posts. Under Adjustment-era poverty in rural Ghana, however, it was clear that some form of mobile services were still needed to reach poorer communities, then in retreat from state health facilities and advance user fees. The new solutions to this problem reinvented the wheel. A wave of foreign-funded religious and NGO-led health services moved into rural areas and the MFUs which had served Ghana from c.1948–88 were recreated privately as “Mission Mobile Clinics” and “NGO Service Expansions,” funded by external donors.Footnote 60

Conclusion

In contemporary Ghana, there are echoes of the older social medicine initiatives discussed in this chapter. There are mission- and NGO-led mobile health services which replaced the MFUs and in the country’s current frontline healthcare, an initiative which hearkens back to the 1930s. Since 1999, Ghana’s Community-Based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) program has become the most extensive primary healthcare network in the country’s history. Small CHPS compounds now cover most communities in Ghana, housing one to three health workers who serve one or two villages. CHPS was another northern innovation adopted nationally, having been proven under conditions of long-term rural poverty in a politically marginal region. For better and worse, the political and economic margins have always been social medicine’s “living laboratory.” If a mode of healthcare provision works where people can afford little and where little infrastructure has been provided, then it is likely to flourish (and save some money) in better resourced districts elsewhere.

This role of the margins is one central observation of the chapter. Marginalized communities are often the sites of cyclical innovation, decline (through persisting political marginality), and then recreation of similar social medicine programs. Ghana’s current CHPS system was developed from a 1990s community-health study called the “Navrongo Experiment,” conducted by the northern Navrongo Health Research Centre with funds from the Rockefeller Foundation and USAID. This was a large-scale demographic surveillance study of approximately 171,000 people in northeastern Ghana, designed to test new community-health interventions in comparison with existing (or nonexisting) rural health services at the end of structural adjustment.Footnote 61 Offering community-based services with family planning and maternity care, the trial’s clear success led to its national implementation in the early 2000s and in areas where CHPS operated, childhood mortality was halved within years of its inauguration.Footnote 62 CHPS has been hailed as a landmark in the extension of primary healthcare in Ghana and cited as an exemplar for effective community-based medicine worldwide.Footnote 63

It is interesting to note the extent to which the CHPS system resembles a much earlier success. The 1930s Native Authority healthcare system placed trained health workers directly into rural communities, working closely with traditional leaders and their networks. Its approach to health provision was decided collaboratively, through consultation between NA health workers and the communities they served, who provided labor and funding for activities like disease surveillance, maintenance of facilities, and rural sanitation. The NA system was also recognized as an outstanding success by officials and the northern public, who resisted its closure in the 1950s.Footnote 64 Seemingly without knowing of this earlier initiative, the 1990s “Navrongo Experiment” again proposed that successful primary healthcare in Ghana should base trained health workers in rural communities, “to mobilize the previously untapped cultural resources of chieftaincy, social networks, and village gatherings in order to promote community accountability, volunteerism, and investment in health services.”Footnote 65 Beyond its testing in a large-scale trial, and differences in the availability of modern drugs and communications, the CHPS and NA models are closely comparable, based around the same collaborative, community-oriented framework that had been recognized as a success in the 1930s.

This chapter has examined two Ghanaian health programs which embodied many ideas and practices of social medicine. Both the NA system and the Medical Field Units were created in the period 1930–50, both from a foundational concern with the structural determinants of poor health, arising from the long-term political and economic marginalization of northern Ghana – a region which has been the site of multiple successful healthcare “experiments” of this kind. Both programs were responsive to community needs and operated in sequence for almost seventy years: from 1930s colonial rule, across Ghana’s independence transition, and into the late twentieth century. The MFUs demonstrate a practical application of social medicine ideas outside of its main traditions – born from colonial-era advocacy and sustained by African proponents and permissive international contexts for social medicine until the 1980s. The story of these initiatives is in some ways emblematic of broader histories of social and community medicine in Africa from the 1940s. Short-term practical responses to unjust distributions of health resources have endured for much longer than their designers – imagining futures in which such programs would no longer be needed – might have hoped. In the course of group oral histories in 2015 and 2019, many rural communities across different regions of Ghana remembered the Medical Field Units kindly. Older people would sometimes laugh at questions about the availability of government doctors or fixed health facilities from the 1950s–70s. “Government – was there even government?” was one relatively typical reply. “We only had the MFUs.”Footnote 66

As a concluding thought, for these long-past health initiatives and those which succeeded them at the economic and geographical margins of the state, it is worth asking how much was achieved in advancing social medicine’s aims? Initiatives like those discussed above, past and present, were envisioned as creating a virtuous cycle in which improved local healthcare and nutrition might strengthen a community’s economic prospects, relative to other, better resourced places and groups within a state, ameliorating some of the precedent causes of poor health. Community health and social medicine have located many interventions in the gaps of economic opportunity and healthcare distribution which persist at the rural margins. Where did this succeed and why, in the sense of achieving some of social medicine’s aims either locally and practically or as part of a broader political project in the worlds of national and global health?

In addition to research in Ghana, over the past decade this author has intermittently lived and worked near the Pholela Community Healthcare Project, discussed elsewhere in this volume – one of the earliest and most cited exemplars of social medicine in practice, located on South Africa’s rural periphery. The project has been embraced by the post-Apartheid state, celebrated on national health administration websites and new community healthcare facilities and community nutrition projects have been developed as satellites to the main center. Despite the expansion of health facilities, it is hard to say whether political recognition and economic opportunities – as foundational determinants of health – have changed much for people living in these places. By tracing these and other cases over time and into the present, there is more research to be done on how success and its limits should be understood in the historiography and history of applied social medicine.