I prefer “both-and” to “either-or,” black and white, and sometimes gray, to black or white.

Palladio’s long legacy has been defined by his 1570 treatise, I quattro libri dell’architettura (The Four Books on Architecture). Aiming for simplicity of language and the clarity of the rule,2 it communicated a system or grammar of architecture grounded in his own design and building practice.3 Yet the buildings themselves often embrace complexity and contradiction, in response to site conditions, program, and other concerns. This chapter examines the ways in which Palladio’s design for Villa Pisani at Montagnana sought what Robert Venturi called “the phenomenon of ‘both-and’ in architecture.”4

Palladio and Venturi might seem an odd pairing. After all, it was Michelangelo to whom Venturi referred in almost every chapter of his postmodernist manifesto Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), and he perhaps saw the Palladio resurrected in modernist discourse as unduly rigid and systematic.5 For Venturi, complexity and contradiction in architecture reside, in part, where the system gets distorted: where functional and environmental factors intrude to thwart consistency, convention, and simplicity. “Both/and” architecture records these moments of conflict and their resolution.6 Palladio was no postmodernist,7 but Venturi’s “both-and” provides a useful heuristic with which to analyze Villa Pisani.

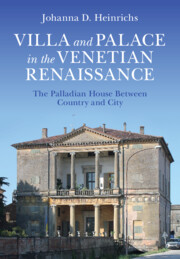

The house takes the form of both a palace and a villa. While the two principal facades retain the same basic composition, in their divergence they record the impact of urbanistic and environmental forces and functional considerations. Its “both-and” status reflects a negotiation of the particularities of the villa’s semi-urban site. This chapter examines how Palladio and his contemporaries conceived the palace and villa typologies in their theory and practice and shows that his approach was more expansive and flexible than the ossified categories applied by modern scholarship. Villa Pisani should nonetheless be understood as an architectural hybrid.

Double-Functioning Facades

Villa Pisani stands on a corner immediately outside the walls of Montagnana (Fig. 7). Here, the town’s main east–west road, now called Via Borgo Eniano, exits the gate known as Porta Padova and intersects with Via Circonvallazione, the ring road that encircles the walls. The villa’s two-story block abuts these roads on the south and west sides. (For convenience and brevity, I will refer to the orientation using the cardinal directions, which is how contemporary documents located it, but in reality, the street front faces southwest and the garden front faces northeast.) The central bays of the street facade are defined by a classical tetrastyle, or four-column, colonnade that is repeated in a second order on the second story and crowned by a pediment, as in an ancient temple. In the lateral bays, a single window on each floor punctures the broad expanse of wall. This three-part division reflects the interior division of space.

7. Montagnana, Villa Pisani, south front on Via Borgo Eniano.

On the ground floor, at street level, Palladio applied four Doric half-columns that support a projecting entablature (Fig. 8). The unfluted columns lack bases, in the ancient manner later described by Palladio.8 The two inner half-columns sit directly on the five steps leading to the central portal, while the outer half-columns rest on plinths. The Doric entablature with its prominent frieze, endowed with triglyphs and metopes bearing antique-style paterae and bucrania, runs continuously around the building like a belt. Villa Pisani’s large entrance portal fills the central bay of the Doric colonnade, and its stone frame tapers toward the bracketed architrave like the Doric columns flanking it. As Tommaso Temanza observed, the doorframe resembles the portal and window frames of the Temple of Vesta at Tivoli, which were later recorded by Palladio in the Four Books.9 The second order, on the piano nobile of the south front, comprises four Ionic half-columns, again made of stuccoed brick with stone bases and capitals (Fig. 9). Three stone balustrades link the dados of the column pedestals to form narrow balconies. A cornice composed of modillions, below the hip roof, forms the uppermost visual accent.

8. Villa Pisani, south facade, detail of Doric order.

9. Villa Pisani, south facade, detail of Ionic order and pediment.

The south elevation exemplifies Palladio’s ability to transmute modest materials into refined all’antica forms.10 His masons crafted the Doric frieze from molded terracotta pieces, while the architraves of both orders and even the Doric guttae are made of wood. All these elements would have been plastered and painted to resemble stone. Palladio sometimes employed timber, a common material for Venetian post-and-lintel construction, for extra-wide intercolumniations, but here it serves as an inexpensive solution for the applied temple-front.11 The walls are constructed of brick, cloaked with a creamy tan intonaco, or plaster. Incised lines, only faintly visible today, originally enlivened their surfaces (Fig. 10). They would have resembled more elevated ashlar construction, usually associated with urban buildings though also employed at Villa Cornaro at Piombino Dese (see Fig. 15).12 The window openings were similarly framed by fictive voussoirs. Smooth bands of stuccoed brick at ground and attic level, and a narrower stringcourse above the Doric entablature, created visual contrast with the fictive ashlar. They counter the verticality of the columns.

10. Villa Pisani at Montagnana, from Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi, Le fabbriche e i disegni di Andrea Palladio raccolti e illustrati, vol. 2, 1778.

That vertical thrust culminates in the pediment, where the ornamental and representational motifs also condense (see Fig. 9). A cartouche with the Pisani coat of arms, a rampant lion, occupies the center, flanked by two reclining winged Victories. These stuccoes have been attributed to Alessandro Vittoria (1525–1608), who, like Palladio himself, was a friend of the patron and executed the Four Seasons sculptures in the palace’s entrance hall.13 The Ionic frieze evokes the Agrippan inscription of the Roman Pantheon as it announces the identity of the patron with crisp Roman capitals: “FRANCISCUS PISANUS IO[ANNIS] F[ILIUS] F[ECIT] (Francesco Pisani, son of Giovanni, made [this]).”14 This all’antica character constituted a break from Palladio’s early villa projects.15 The expanded version of Villa Pisani with triumphal arches, which was published in the Four Books but never realized, would have heightened this novel effect (see Figs 5, 10).

The house’s suspension over water is one of its most striking features, though Palladio did not mention it in the Four Books, nor have many subsequent observers. The western flank of the building rests on a low barrel vault slung over a watercourse known as the Fiumicello (see Fig. 85). On the south side, the vault’s opening now lies well below street level and is only visible through a grate in the modern sidewalk. Early modern passersby, however, would have seen it from both the north and the south. A seventeenth-century map shows its conspicuous presence parallel to a bridge in front of Villa Pisani (Fig. 11). Mainland villas, including Palladio’s own Villa Pisani at Bagnolo and Villa Badoer, often were situated in direct relation to a river or canal.16 The patron Francesco Pisani, having been raised in the lagoon city, would have found nothing strange about living next to and even over water. The fifteenth-century apse of the Venetian church of Santo Stefano, for example, rests on a similar barrel vault spanning the canal.17

11. Villa Pisani, detail from Zuane Malamàn (copy after), “Hydrography of the territory of Montagnana,” 1699. Archivio Storico del Comune di Montagnana, Raccolta Mappe, dis. 84.

Sober and imposing, Villa Pisani’s street front assumes the guise of an urban palace. With its columnar motif attached to the wall, the facade appears closed off from the bustle of the street corner, like Palladio’s palaces in Vicenza (Fig. 12). Its two stories reinforce this palatial impression. The rear elevation, on the other hand, bears a less insistently mural countenance (Fig. 13). In place of the engaged columns of the street front, the free-standing Doric and Ionic orders open up the wall to form superimposed loggias or porticoes in antis, again surmounted by a pediment.18 These two vaulted loggias connect to one another by way of two spacious, well-lit spiral staircases encased in the northeast and northwest corners of the house. Today the loggias’ columns frame views of a leafy garden, as they have since the early eighteenth century (Fig. 14; see also Fig. 87). Originally, however, the Pisani farm court (cortivo) and orchard (brolo), lay behind the house, as Chapter 4 will show. A peschiera, or fishpond, dug from an older water channel, the Fossetta della Bastia, separated these two areas. The open loggias, long a feature of rural buildings in the Veneto and elsewhere, responded to the nature of this side of Pisani’s property. From here, Villa Pisani looks like a villa.

12. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto, Vicenza, designed ca. 1546.

13. Villa Pisani, north front.

14. Villa Pisani, view of garden and later farm dependency from the upper loggia.

Its two facades mirror one another in composition, but with Palladio’s variation of the columnar temple-front motif they take on different purposes and meanings in response to the environment around them. This typological ambivalence or ambiguity has proven an interpretive obstacle in the literature on Villa Pisani. Attention to function and setting can help us to recognize Palladio’s “both-and” approach.

Palace or Villa?

Since the early twentieth century, scholars have struggled to categorize Villa Pisani within the standard typology of Renaissance domestic architecture: Is it a palace or a villa? It has always received the appellation “villa,” because Palladio included it in book two of his treatise among his designs for case di villa (houses on country estates) for noble Venetians – not in the chapter on case di città, or city houses.19 In its expanded form published in 1570, it looks somewhat more like the other villas presented in the same chapter, which have barchesse (arcaded or colonnaded barns) and other agricultural annexes attached to a central residential core. Its two stories nonetheless distinguish it from most of Palladio’s case di villa, which have one piano nobile, or living floor. Catalogs of the villas usually include Villa Pisani,20 but Palladio’s first modern critics rejected this classification because of its palatial qualities. Fritz Burger, for example, excluded it from his 1909 study of the villas: he averred in a footnote without further discussion that it ought “to be counted among the city palaces.”21 Giangiorgio Zorzi’s magisterial studies enshrined this brusque judgment when he treated Villa Pisani in his 1965 volume on Palladio’s public works and private palaces. He went so far as to claim that Villa Pisani “has not a single characteristic of country houses but only of urban dwellings.” It appeared to lack agricultural outbuildings on the site, and the wings projected in the Four Books were designated by Palladio as service spaces for the household, not for the farm. Zorzi concluded that Palladio’s classification of Villa Pisani was “inexact” and showed the architect ignoring his own rules as put forth in the treatise.22 Later authors reiterated Zorzi’s assessment, citing the (apparent) lack of farm buildings and concluding that Villa Pisani has “the character more of a palace than a villa.”23

Some scholars moved away from the palace–villa dichotomy to seek a more nuanced classification system that would account for the formal variety of Palladio’s villas. Villa Pisani thus has received the designation “suburban villa,” to distinguish it from the villa rustica or villa-fattoria, the farm type with which Palladio is more commonly associated.24 Ackerman grouped Villa Pisani with similar examples, such as Villa Cornaro at Piombino Dese and Villa Mocenigo at Marocco, that shared its two stories and location on a well-traveled road (Fig. 15). Forssman suggested Villa Pisani is a “villa suburbana in the Vitruvian sense,” or “a villa that is almost a palace.”25 Other scholars have dubbed it a palazzo suburbano26 and a “villa-palace.”27 The following tortuous description reveals the taxonomic knots Villa Pisani has wound in the scholarship: it “must be considered rather a palace than a villa, or a villa suburbana, not dissimilar from a villa true and proper, but with features typical of a palace.” Like Villa Cornaro and Palazzo Antonini in Udine, it is continually “oscillating … between two different typologies.”28

15. Andrea Palladio, Villa Cornaro, Piombino Dese, exterior from the northeast, 1552–54.

The emphasis on labels characterizes the typological approach of the first modern Palladian studies and the catalog genre to which so many publications on Palladio and his villas belong – an approach that ultimately goes back to Vitruvius and Renaissance theorists themselves. Carolyn Kolb’s fundamental essay of 1984, by contrast, sought to elucidate its function through original documents rather than formal categories. She marshalled a range of archival evidence to prove that Villa Pisani had operated as the center of an agricultural estate and had possessed auxiliary buildings to serve this function. She also posited the neo-feudal implications of Francesco Pisani’s consolidation of land around Montagnana, as scholars had recently done for other Palladian villas.29 Her assessment, confirmed by further research presented in Chapter 4, validated Palladio’s original designation of Villa Pisani as a casa di villa.

The trouble with classifying Villa Pisani is partly a problem of the scholarship’s own creation as it has tried to fit this building into categories unrecognizable to the period of its ideation, as we shall see.30 Nor has it acknowledged shifts in Palladio’s own thinking, as it seeks to apply the broad categories of the 1570 treatise to buildings designed years earlier for a wide variety of settings. The difficulty categorizing this villa also reflects the broader challenge of formulating a coherent formal typology for the Renaissance villa that correlates with function.31 As Burns noted, Palladio himself was “much less preoccupied with villa and palace typology than many who have written about his architecture.”32 The focus on typology in the Palladio literature has rightly underscored Villa Pisani’s “mixed character”33 but also diverted attention from its significance. The building’s urban or palatial qualities, and its relationship to Palladio’s designs for both city palaces and similar villas, must be accounted for, especially considering the villa’s farm function. But no label can resolve the fundamental – and intentional – ambiguity of Palladio’s conception.

The Problem of Language

Contradictions and ambiguity in terminology and usage further muddy the classificatory waters. Modern scholars draw a clear distinction between the villa, country house, and the palace, city house, but the sixteenth-century lexicon did not. The term villa usually encompassed an entire rural estate: not just the casa dominicale, or owner’s house, but also fields and orchards, barns and dovecotes. In contrast, modern English uses “villa” as a synecdoche, reducing the sixteenth-century whole to one of its parts – the owner’s residence.34 Palace (palazzo), on the other hand, was used infrequently in the Veneto before the middle of the sixteenth century, but it did not imply an exclusively urban location. A survey of the Montagnana estate conducted in 1570 described Villa Pisani as “a palazzo at Montagnana on the main road” and valued it at 3,500 Venetian ducats.35 Here the term underscored its great size and financial worth. Palazzo becomes a synonym for another phrase used in a notarial document, domus magna, which distinguished it from the humbler houses surrounding it in Montagnana’s Borgo San Zeno.36 The use of palazzo here also may have alluded to the social station of the building’s owner. Yet, in Venice proper, as Francesco Sansovino observed in 1581, the generic, modest term house (casa or ca’) was employed even for patrician homes, because Venetians reserved palazzo for the Doge’s Palace.37 In good Venetian fashion, then, Francesco Pisani refers, in his will of 1567, to Villa Pisani as “la casa da Montagnana” and his smaller villa in Monselice as “la casina.”38

Within the theoretical discourse on domestic architecture, Francesco di Giorgio Martini had defined a palazzo as a casa for a noble family (“le case delli nobili overo palazzi”), whose status required a more ample residence with spaces for the reception of guests, dining rooms, storerooms, and gardens.39 In Palladio’s Four Books, however, location inflects terminology. He used house for residences both in the city and on country estates: case di città and case di villa. He underscored this geographical distinction when he placed his best-known villa, La Rotonda (Villa Almerico-Capra), with his designs for city houses because it stood so close to the city of Vicenza “that one could say it is in the city itself.”40 Rigid definitions of and distinctions between palace and villa would have made little sense to Renaissance ears accustomed to greater flexibility in vocabulary and usage. Location, decorum, and function were more likely to inform word choice than formal characteristics other than size.41 But by these measures, Villa Pisani still oscillates between terms and types.

“E si fa come si usa nelle Città”

The flexible terminology applied to domestic architecture further reflects the lack of a distinct formal type for the Veneto villa and the fluidity with which architectural forms moved among different settings and contexts. Many fifteenth-century villas for the terraferma nobility borrowed from their counterparts in mainland cities, especially in the three-part plan and a centrally placed loggia on the piano nobile.42 An extreme example is Villa Porto Colleoni in Thiene, a villa-castle of the mid-Quattrocento, whose central loggia lighting the main hall, ground-level portico, and corner towers have been traced to the Venetian fondaco typology (Fig. 16). The rectangular frame and ornamental detail of the central loggia derive from Venetian Gothic palaces.43

16. Thiene, Villa-Castello Porto Colleoni, mid-fifteenth century.

Villa Pisani’s motif of double porticoes or loggias in a tripartite facade can similarly be traced to earlier sources in both urban and rural building traditions. Francesco Pisani would have been intimately familiar with the Pisani palace at Santa Maria Zobenigo, where his father grew up and which has superimposed loggias of five pointed arches at the center of its canal front (see Fig. 35). This facade arrangement was typical of Venetian palaces, where the clustering of arched openings normally lit the portego, the deep central hall on each of the two principal living floors.44 But fifteenth-century vernacular architecture on the mainland would have furnished examples of a similar form employed for a more rustic setting and function. The Casa dal Zotto in Venegazzù (Treviso), for example, features a loggia above a portico, both with wooden trabeation, while the Villa Piovene in Brendola (Vicenza) presents a five-arch ground-level portico with a loggia above, attached to a tower (Fig. 17).45 The lower of the two porticoes probably stored farm implements.46 In the early sixteenth century, Villa Giustinian at Roncade (under construction in 1514 and attributed variously to Tullio Lombardo and Fra Giocondo) brought these monumental and vernacular traditions together with the new all’antica style (Fig. 18). With its two stories, double loggias, and pediment, it represented an important precedent for Villa Pisani.47

17. Brendola, Villa Piovene, fifteenth century.

18. Roncade, Villa Giustinian, ca. 1515.

Not only local examples but also the Vitruvian legacy would have conditioned Palladio’s thinking about domestic architecture. The Roman architect had posited essential similarities between city and country houses in book six of De architectura libri decem. The only difference he noted lay in the reversal of the atrium-peristyle sequence of the urban domus; in the villa the peristyle courtyard came first.48 In De re aedificatoria, written ca. 1450 but first published in 1486, Leon Battista Alberti elaborated on the relationship between the two types of “private buildings.” He was concerned with three aspects: availability of space, ornament, and architectural form. Of the first, he noted in book nine that the dense city fabric restricted the footprint of urban buildings, requiring development upward, in multiple stories. Villas, on the other hand, enjoyed “greater freedom” to expand outward across one main living floor.49 Palladio reiterated this point in his own chapter on the site of a villa, and most of his villa plans have one principal story.50 Alberti’s treatment of ornament, his second area of concern, appears to reinforce the spatial distinction he drew between restriction and freedom. The town house requires a sober, dignified appearance (gravitatem), while the villa permits the ornamental “allures of license and delight” (festivitatis amoenitatisque illecebrae).51 Licentiousness in the decorative articulation of a villa house corresponds to its more expansive footprint. Later in book nine, however, Alberti qualifies this rule in a chapter dedicated to ornament on private houses. He suggests that a town house’s interior rooms may be as festive as those of a country house, but the exterior, especially the portico and vestibule, “should not be so frivolous as to appear to have obscured some sense of dignity.”52 A glance at book five complicates matters further. There Alberti advises that the town houses of the wealthy should “assume all the charm and delight of a villa” insofar as the restrictive urban setting allowed it.53 He refers here to architectural forms that encouraged openness, light, and views outside: walkways, loggias, porticoes, gardens.

In Alberti’s view, then, a palace should resemble a villa as much as possible, except where urban decorum demands prudence or the site poses constraints. Indeed, the villa type provides him with “the basis for an entire ideal regarding domestic architecture.”54 The town house and country house seem to occupy different positions on a single spatial, ornamental, and architectural continuum that ranged from constraint and restraint to liberty and license. Their relative positions on this spectrum were dictated by their location, not by an essential difference in building type. Therefore, a particular setting might dictate a specific design choice, such as construction of multiple stories in a dense urban site. Similarly, loggias and porticoes opened the villa to its natural surroundings while palaces sometimes required a more closed external appearance.

Palladio, a close reader of Alberti and Vitruvius, likewise did not consider the casa di villa and the casa di città to be distinctly different building types.55 In book two of the Four Books, he places Villa Pisani among his designs for country houses, and Palazzo Antonini in Udine, which has a similar plan, among the town houses. He asserts that the architect should approach the design of a villa with regard for the owner’s family and status, just as he would do in the city (“E si fa come si usa nelle Città”).56 His emphasis on the appropriateness of a building to its owner’s status and wealth recalls Vitruvius, who discussed the differences between the urban domus and the villa in his chapter on decorum in domestic architecture. When choosing the site of a villa, Palladio wrote, “one must bear in mind all those considerations that relate to selecting a site in the city, because the city is nothing other than some great house and, contrariwise, the house is a small city.” Palladio borrowed this analogy from Alberti’s treatise as it had been translated in 1550 by Cosimo Bartoli.57 Palladio, like his predecessors Alberti and Vitruvius, observes distinct categories of city house and country house but, also like them, saw more parallels than rigid boundaries. The site, as well as status of the owner, determines precise form. This flexible approach is best illustrated not by Palladio’s theoretical text but by his buildings.

Villa Pisani and Its Sister Houses

Scholars have long observed an affinity among Villa Pisani and two other residential projects undertaken by Palladio in the same period: Villa Cornaro at Piombino Dese, whose first phase of construction took place in 1552–54, and Palazzo Antonini in Udine (1556). Palladio underscored the close relationship between Villa Cornaro and Villa Pisani, its “twin palace,” by publishing the two buildings side by side in the Four Books (see Fig. 5).58 They shared not only Venetian patronage and nearly identical dates of ideation and construction but also obvious similarities in their design, from the two stories to the interior organization centered on a four-column hall. Unlike the more ambitious scheme for Villa Pisani, Villa Cornaro’s projected wings were realized, though not during the lifetime of the original patron.59 In both houses, Palladio employed a double columnar order with a pediment on both the street and garden facades, but he transformed Villa Pisani’s Doric-Ionic tetrastyle into a less sober Ionic and Corinthian hexastyle for the Cornaro (Fig. 19; see also Fig. 15). These take the form of superimposed loggias in antis on the garden (south) side, like those at Villa Pisani. On the street facade, however, the columns form porches that advance from the body of the house, similar to Villa Giustinian at Roncade (see Fig. 18). The relative distance of Villa Cornaro from the road may have justified the more ornate order.

19. Andrea Palladio, Villa Cornaro, Piombino Dese, south facade, 1552–54.

Palazzo Antonini in Udine also presents a block-like central unit and a tripartite facade with superimposed columnar orders.60 In his treatise, Palladio included a tympanum above the orders and a single wing for service spaces, but these were never realized (Fig. 20). It exhibits the same striking combination of open and closed facades present at Villa Pisani: the orders are applied to the wall as half-columns on the street side and inset loggias on the garden side. And it shares the orders of Villa Cornaro: Ionic and Corinthian hexastyle. It departs from both its predecessors, however, in the unusual rusticated treatment of the lower Ionic order and corner quoins, which reinforce the robust, mural character of the street facade.

20. Andrea Palladio, plan and elevation of Palazzo Antonini, Udine, from I quattro libri dell’architettura, 1570.

Since Rudolf Wittkower’s influential analysis of the geometry of Palladian villas, both scholars and architects have admired Palladio’s compositional “play” with a set of basic building blocks.61 He generated an astonishing variety of plans using a standard set of room shapes, interrelated proportions, and a basic tripartite plan, in which parallel suites of small and medium-sized rooms flank a central axis defined by the sala or main hall. The plans of Villas Pisani and Cornaro and Palazzo Antonini similarly reveal iterations of the theme of a square central hall axially aligned with a loggia and a connecting corridor (Figs 20–21; see also Fig. 5). This axis is flanked by suites of two or three rooms. The double staircases, which fill in the corner spaces flanking the rear loggia in Montagnana and Piombino, have shifted to either side of the central corridor in Udine. At Villa Cornaro, the entrance hall lies adjacent to the garden loggia, with the corridor leading to the street-side portico. In Villa Pisani and Palazzo Antonini, the order is reversed, so that the tetrastyle hall ushers in visitors from the street and the axial corridor leads to the rear loggia. Palladio endowed each ground-floor hall with four columns to support the story above, and these spaces in turn recall the entrance atrium of the recent Palazzo Porto in Vicenza. Within Palladio’s own body of work, architectural forms migrated with ease between country and city.

21. Andrea Palladio, Villa Cornaro, Piombino Dese, plan and elevation, from I quattro libri dell’architettura, 1570.

Palladio introduced the combination of a frontespicio, or tympanum, with a double order on a house in Villa Pisani and Villa Cornaro. But this idea, too, originated in the early planning for Palladio’s palace for Girolamo Chiericati in Vicenza (1550–51) (Fig. 22).62 Palladio experimented with a projecting, five-bay central section composed of superimposed Doric and Ionic orders. As built, it forms an open portico at ground level and engaged columns on the wall of the sala above. Notably, project drawings show that a classical pediment or frontespicio was to accentuate the central bays, though it disappeared in the realized design, which has a continuous ground-floor portico. One drawing also anticipates the use of a baseless Doric order at Villa Pisani.63 As built, Palazzo Chiericati may have suggested the pairing of open and closed facades. It too possessed an engaged order on the street (upper floor) and Doric-Ionic tetrastyle loggias on the rear. The placement of staircases to either side of those courtyard loggias would be repeated at Montagnana and Piombino Dese.64

22. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Chiericati, Vicenza, begun 1550.

Domestic architecture for Palladio, as for Alberti, represented a continuum of possible solutions conditioned by location. In some cases, the setting required the combination of urban and rural forms. At Villa Pisani and its sister houses, we find both the loggias of the villa and the taller profile of an urban palace. Palazzo Antonini and Villa Pisani display a closed palatial facade conjoined to the perforated elevation of a villa. Palazzo Chiericati, meanwhile, opens to the piazza on which it stands in the manner of a country house with its spacious columnar porticoes and loggias.65 The deliberate ambiguity – the combination of elements associated with both palaces and villas – was appropriate to their liminal position at the interstices of city and country. Palladio would present several related designs in the Four Books, for two-story houses with double porticoes, and at least three of them also were planned for suburban sites or sites near major roads.66

Palazzo Chiericati and Palazzo Antonini are both located within the walls of Vicenza and Udine, respectively, but in the sixteenth century they stood at the periphery of the dense city center where open space prevailed. The Chiericati portico surveys a broad, irregular piazza known as the Isola, located at the edge of the city center and the site of the cattle market. The Isola served as Vicenza’s “port” on the Bacchiglione River, prompting the palace’s comparison to a Roman villa marittima.67 In Udine, the Antonini family accumulated property in Borgo Gemona, the area between the third and outermost circuits of the city walls. At the time of Palladio’s intervention, this district was still devoted in part to agricultural production, but it also lay on the route of merchants and goods traveling to and from Germany. A small watercourse, like the Fiumicello in Montagnana, passed immediately behind the house, and the rear loggias provided views of an uninhabited verdant expanse known later as the Giardino Grande (Fig. 23).68

23. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Antonini, Udine, garden facade (ca. 1964).

Villa Cornaro’s situation was more rural than the others, but its northern facade overlooked a regional road running through the village of Piombino Dese. The south side faced a garden and the family’s orchard (brolo), which lay beyond a watercourse called the Draganzuol Vecchio (Fig. 24).69 Villa Pisani faced a well-trafficked, extraurban road and a significant water course, within view of Montagnana’s major town gate and public mills. The loggias on the north side overlooked the family’s farm court, as Chapter 4 will show.

24. Villa Cornaro, Piombino Dese, view of garden and fishpond from south portico.

The architectural forms that Palladio first tried at Palazzo Chiericati responded to the relative openness and mixed urban-rural character of its site, and they proved suitable for the commissions he received soon afterward. He did not design according to a predetermined typology but rather developed variations on a theme adapted to the unique nature and exigencies of the site and the building’s intended function. At Villa Pisani, as at Villa Cornaro and Palazzo Antonini, a clear distinction existed between the semi-urban character of the street and the private, more rural character of the site on the opposite side of the house, and the building responded to this dual nature.

Two Faces

Many of Palladio’s built villas distinguish front from back hierarchically, with a shift in architectural and ornamental elaboration. He put a frontespicio, or pediment, on the front facade because it showed off the house’s entrance, “thus making the front part more imposing than the others.”70 Although some villas in fact bear two pediments, the presence of an arcaded portico on the side facing the main approach re-establishes the hierarchy of elevations, as at Villa Saraceno at Finale (ca. 1546).71 Palladio’s statement applies best to his villas of the 1550s, when he began to employ a full, pedimented temple portico at the house’s main entrance. At Villa Chiericati at Vancimuglio, begun around 1555–57, a full classical pronaos projects assertively on the front elevation, while the rear presents a simplified pediment above a stone portal.72 The entrance of Villa Emo at Fanzolo, designed by 1556, is instead set within the body of the house, and the portico columns stand in line with the front wall (Fig. 25). The rear, facing Emo fields, lacks both a pediment and an order and boasts no ornament whatsoever. It could never be mistaken for the front. Palladio modulated his facades according to the nature of the surroundings.

25. Andrea Palladio, Villa Emo, Fanzolo, 1559.

The designs for Montagnana, Piombino, and Udine call attention to what is usually considered the building’s rear – that is, the opposite side from the main entrance or the street front. These houses can be said to have two principal fronts, for both the street and garden facades present the same degree of finish and architectonic complexity. Palladio endowed both sides with the double order and temple pediment, while varying the treatment of the order and the portico. At Villa Pisani, the columnar motif shifts from applied to freestanding; at Palazzo Antonini, the columns further change from rusticated to smooth (see Fig. 23). Villa Cornaro’s garden porticoes in antis become projecting porches on the north side overlooking the street (see Figs 15, 19). In all three houses, the entablature of the lower order continues across the breadth of the facade on both front and rear. Each front is subtly differentiated from the other but given equal visual importance. These two-faced villas look back to Falconetto’s Villa dei Vescovi at Luvigliano, designed around 1535, but also anticipate the four identical facades at Villa Rotonda of ca. 1566–67.

While the differences between the orders on each facade reflect in each case the shift from street to garden, the parity between the facades may relate to use. The Cornaro likely traveled by boat from Venice and disembarked at a landing stage near the brick bridge at the southern end of their garden (see Fig. 24).73 From here, they made their way across the garden before a ceremonious ascent of the ramp to the entrance portico. Villa Pisani’s public face on the street declared the family name and nobility to passersby through the arms in the pediment and the refined inscription. Its closed, palatial countenance addressed the semi-urban setting. The same combination of elements on the garden front, articulated as loggias, referred to the natural environment and the private world of villa, garden, and farm. But it also established a dignified approach for the owner and his family and guests. When an anonymous painter undertook a portrait of the Montagnana residence on the interior of Francesco Pisani’s second villa at Monselice, he did not represent the house’s street side, as one might expect. Instead, as we will see in Chapter 6, he depicted the north front, the view enjoyed by the family and their retinue upon arrival by coach (see Fig. 113).

The equivalence between the villa’s two facades suggests that the typological oscillation we have described can be more precisely identified as a form of hybridity.74 A hybrid’s two parts do not blend together beyond recognition but remain identifiable constituents. Villa Pisani’s Janus-like faces, joined by their continuous entablature, express the conjunction of two worlds: urban and rural. Hybridity was not a word used in the sixteenth century, but its conceptual foundation would have made sense to contemporaries.

Hybrid Architecture

Originally a biological term for the offspring of two different species, hybrid denotes an intentional combination of unlike things. Its Latinate root, for example, referred originally to the offspring of a tame sow and a wild boar.75 This concept has enjoyed considerable currency since the late twentieth century. In popular culture its reference points swing from science fiction to automobile engineering. It has become a central if contested concept in postcolonial discourse, where it often reflects a concern for the permeability of boundaries and identity.76

Renaissance thinkers, on the other hand, were drawn to taxonomic modes of analysis that tended to reinforce categorical boundaries and hierarchies. Literary, art, and architectural theorists drew distinctions among objects of study and compared or ranked their relative merits. The short 1566 text Le ville by Anton Francesco Doni identified five types of country residences based on the social class of the owners from peasant to prince.77 The codification of the columnar orders in Renaissance treatises offers a well-known example. In Book IV of Sebastiano Serlio’s treatise, titled Regole generali di architettura sopra le cinque maniere de gli edifici (General Rules of Architecture on the Five Styles of Building) and first published in 1537, the Bolognese architect codified the five orders inherited and adapted from antiquity (Fig. 26).78 He established each column’s place in a definitive sequence of increasing proportions and ornateness and recommended appropriate uses for each one.

26. Sebastiano Serlio, The Five Styles of Buildings, from Book IV, Le regole generali di architettura sopra le cinque maniere de gli edifici, second edition, 1540.

Serlio’s “rules” were flexible enough, however, to admit the possibility of mixing column styles. He suggests that an architect could join elements of one order with those of another to create visual variety and expressive nuances. He presents several of his own portal designs in which he applied rusticated stonework to finished columns of various orders, a practice sanctioned, he explains, by ancient Roman examples. A doorway with engaged Tuscan columns banded by rustication combines “the work of nature” and “the work of human skill” (Fig. 27). Serlio cites Giulio Romano’s suburban villa-palace, the Palazzo Te in Mantua, as a praiseworthy example of such “mixing” (mescolanza).79 As Alberti had indicated, the architect could exercise creative license in a setting where the rules of decorum applied less stringently and where nature held sway over art.80 Significantly, Serlio’s “mixing” – what we might call hybridization – preserves the unique identities of the two constituents. New meaning emerges from their visual juxtaposition, not from an undifferentiated merging.81 Serlio would surely have appreciated the metaphorical potency of the hybrid’s etymological combination of domestication and wildness. It was like wrapping an elegant Ionic column in coarse rustication, as Palladio would later do on the ground-floor order of Palazzo Antonini in Udine. Serlio might even have deemed it appropriate to describe the conjunction of two building types associated, respectively, with urban civilization and what was seen as the less constricted and constricting countryside.

27. Sebastiano Serlio, rusticated Tuscan-order portal, from Book IV, Le regole generali, 2nd ed., 1540.

City and country constituted two other categories whose merits were compared and debated in Renaissance literature – from Petrarch to Alberti to sixteenth-century agricultural writers like Agostino Gallo. They found the topos of the antithesis between city and country in their reading of the ancients. Indeed, Ackerman has posited the urban-rural opposition as the basis of villa ideology throughout western history.82 Authors celebrated the freedoms afforded to the city-dweller who spent time in the countryside: to escape the formality and rules of society; the pressures of politics and negotium (business); the clamor of urban existence. Pliny the Younger had praised the peaceful otium (leisure) of his Tuscan villa: “the repose I enjoy here is more quiet and undisturbed than anywhere else. No summons to the bar; no clients at my gate; all is calm and still.”83 In Gallo’s dialogue Le dieci giornate della vera agricoltura, e piaceri della villa (Ten Days of True Agriculture and Villa Pleasures), the villa-dwelling Giovanni Battista Avogadro echoed Pliny’s encomium: “Who would want to live anywhere but in the country? Here we have complete peace, real freedom, tranquil security and sweet repose.”84 Architectural practice did not necessarily conform to this literary duality, as the flexible interchange between town and country houses demonstrates.85 The tropes of urban constriction and rural freedom nonetheless resonate in Alberti’s discussion of town and country houses in De re aedificatoria, as we have seen. A rural location afforded greater openness in architectural form; greater spatial freedom for the house to sprawl on one level rather than rise vertically; and greater license in its ornament and decoration. Alberti recommended that the palace model itself on these qualities of the villa whenever possible.

He identified a third type of private residence, however, that constituted a “middle way” between city palace and country house: the suburban garden (orti suburbani). Located outside but close to an urban center, the suburban garden combined “the dignity of a city house with the delight of a villa.”86 This solution resolved a dilemma, namely that while country life encourages good health, his affairs require a patron to reside in the city. “[O]f all buildings for practical use, I consider the garden to be the foremost and healthiest: it does not detain you from business in the city, nor is it troubled by impurity of air.”87 Alberti’s orti suburbani, rendered as “gardens surrounding the city” (“giardini intorno alla città”) in the Bartoli translation of 1550, exploited the open space in the urban periphery for the planting of extensive gardens conducive to pleasure, recreation, and health.88 It is clear, despite the name, that Alberti’s suburban garden had an architectural component, for his reference to dignity and delights echoes his discussion of the ornament of town and country houses earlier in the chapter. Like Serlio’s rusticated Doric column, the suburban garden was a hybrid, combining the forms of the villa and the palace.

Villa Pisani is an Albertian hortus suburbanus.89 Palatial in height, it would also have sprawled laterally with the addition of the wings presented in the Four Books. Its corner site and the absence of other large buildings surrounding it gave the house a relative freedom emphasized by Palladio’s deployment of the pediment, which could only be appreciated from a distance.90 As with Serlio’s mescolanza of columnar types, Alberti’s hybrid category is meaningful as long as both the palatial and the rustic characters remain discernible. The building must maintain dignified sobriety while promoting cheerful relaxation. Palladio’s two-faced design achieves this equilibrium. As in the hortus, decorum and dignity required the closed, urbane character of the street facade. The shady recesses of the north-facing rear loggias sheltered the padrone as he enjoyed fresh breezes and pleasant views framed by columns – Alberti’s villa delights. The Pisani’s garden rubbed shoulders with the farmyard, however, and so elements of the farm villa were further grafted onto this hybrid building.

The Suburban Villa ca. 1550

Villa Pisani can be compared not only with its Palladian sisters and Alberti’s hortus but also with suburban villas of the mid-sixteenth century in Rome and Genoa. A similar fusion of palace and villa architecture characterizes Genoese Renaissance villas. Their architecture reflected their role as an alternate family seat, close to the city but set in nature, and serving as a formal ceremonial or entertainment center.91 The Umbrian architect Galeazzo Alessi, who arrived in Genoa in 1548, established an influential formal type with his villa for Luca Giustiniani (Fig. 28). Vasari was so struck by its similarities to Palladio’s work that he attributed its design to Palladio himself, though in another part of the Lives he designates the “palazzo in villa di messer Luca Iustiniano” as Alessi’s.92 Villa Giustiniani, now Cambiaso, rises on the slopes of Albaro, a suburb immediately east of the city. Its two-story cubic volume, similar to Villa Pisani, also recalls the palaces that would be built along Alessi’s Strada Nuova and published in Rubens’s Palazzi di Genova – justifying Vasari’s description.93 Yet, unlike the palaces, Villa Giustiniani’s main facade opens itself to views of the sea in a central, ground-floor loggia, which is matched on the rear facade by a loggia on the second story.94 Both Alessi and Palladio experimented with a spatial organization in which the loggia, hall, and corridor are aligned along the central axis to create continuous views through the house and into the landscape.95

28. Galeazzo Alessi, Villa Giustiniani Cambiaso, Albaro (Genoa), 1548.

In Rome earlier in the century, Baldassare Peruzzi had combined a closed, palatial elevation with a facade pierced by loggias in his suburban villa-palace for Agostino Chigi, later the Villa Farnesina (see Fig. 50).96 The new papal retreat for Julius III in Rome, begun in 1551, took up this precedent and offers further points of comparison with Villa Pisani (Fig. 29).97 Villa Giulia’s gardens and fountains and its location close to Via Flaminia, just north of Rome’s Porta del Popolo, give it the character of an Albertian hortus suburbanus.98 Palladio likely visited the building site during his sojourn in Rome in 1554.99 The papal casino, designed by Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola, shares with Villa Pisani the palatial character of its two-story entrance front, while the garden side boasts the semi-circular portico frescoed as a fictive pergola. Palladio may have recognized other similarities with his own Villa Pisani, which was then nearing completion. On the brick facade facing toward Via Flaminia, Vignola emphasized the central bay with a triumphal arch motif doubled on two stories, using rusticated forms of the Tuscan and Composite orders. The two superimposed levels of orders create a vertical unity across the two-story elevation, not unlike the columnar frontispiece of Villa Pisani’s facade. An alternative scheme shows a rusticated triumphal arch at ground level, a serliana above, and a pediment crowning the composition (Fig. 30). The result even more strongly recalls Palladio’s facade solutions.100 Vignola’s deployment of the triumphal arch on this villa facade finds a further parallel in the unbuilt arches for Villa Pisani, as recorded in his 1570 treatise (see Fig. 116). By the time Palladio arrived in Rome, the casino’s main structure was nearly complete and he would have found Vignola’s facade already in place, so any direct influence in the early planning of either building is unlikely. The connections are nonetheless striking and may hint at some cross-pollination of ideas between the two architects.

29. Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola, Villa Giulia, Rome, 1551–55.

30. Anonymous, project for the elevation of the exterior facade of Villa Giulia, ca. 1560–70. Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, NMH CC 1367.

Palladio was not alone in his investigation of the appropriate form for a building located between country and city. Alberti’s hortus suburbanus provided an important conceptual precedent for these brick-and-mortar essays in architectural ambiguity. Yet, at Villa Pisani, unlike the villas in Genoa and Rome, its capacity as a villa encompassed the functions of not only the pleasure retreat envisioned by Alberti but also the productive farm.

* * *

Questions of typology will not take us far into the life of a building.101 Villa Pisani has proven difficult for scholars to categorize, but as with Alberti’s suburban garden, its ambiguity was a deliberate choice by the designer. Villa Pisani, together with Palladio’s other villa-palaces of the early 1550s, reveals the flexibility of his approach to villa and palace design. Form was generated not according to a preconceived typology but in response to the site and intended uses, to which the architect was closely attuned.102 The significance of Villa Pisani’s double visage lies in the fact that it is recognizably both a villa and a palace.

Villa Pisani provided more ample living space than Palladio’s one-story villas, as appropriate to its hybrid typology and to a villa used as a primary residence. In Chapter 3, our focus will shift from Villa Pisani’s place in Palladio’s design practice and thought to the villa as a lived experience. It has been suggested that Palladio’s villa-palaces hid their utilitarian farm functions to “exalt the roles of (self-) representation or of the privileged refuge of humanistic otium.”103 We will see the ways in which, at Villa Pisani, these functions coexisted with rural business (negotium), hospitality, and even religious devotion. But, first, we will examine the patron, Francesco Pisani, his family, and his life in Venice, to understand why he needed not only a villa but also a palace in Montagnana.