Introduction

As the first multilateral agreement to ban an entire category of weapons of mass destruction, the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC) is considered a landmark treaty. However, unlike other nonproliferation treaties, the BTWC does not have a verification mechanism, leaving states parties unable to formally demonstrate or evaluate compliance. The Convention, in other words, is essentially a codified taboo, one established to protect humanity from weapons deemed “repugnant to the conscience of mankind” (Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction, 1972). It is thus reasonable to question what the consequences to the Convention—and to the larger taboo it embodies—might be if one state party, in good faith or not, accuses another of prohibited activity. Indeed, such a scenario is presently unfolding.

On June 29, 2022, the Russian Federation invoked Article V of the BTWC, mandating a Formal Consultative Meeting to discuss alleged U.S.-funded biological weapons laboratories in Ukraine. Article V serves as the Convention’s dispute mechanism, allowing states parties to request bilateral or multilateral consultations to resolve compliance concerns. While the Ukrainian facilities that were the subject of Russia’s request do exist, they are dedicated to purely peaceful activities, including epidemiological surveillance and the development of disease diagnostics and medical countermeasures (Houser et al., Reference Houser, Koblentz and Lentzos2023; Nikitin, Reference Nikitin2022). Forty six of these facilities have received funding and technical assistance through the U.S. Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) Program (U.S. Mission to International Organizations in Geneva, 2022), which was established in the 1990s to destroy, secure, or divert weapons of mass destruction and associated infrastructure, materials, and expertise in countries of the former Soviet Union (Goodby et al., Reference Goodby, Burghart, Loeb and Thornton2004). Russia is well acquainted with the peaceful nature of U.S. CTR activities, having been a beneficiary of the program for many years (Nikitin & Woolf, Reference Nikitin and Woolf2015). Nevertheless, at the conclusion of the September 2022 Formal Consultative Meeting, despite detailed presentations from the United States and Ukraine, the Russian delegation insisted that it had not received satisfactory explanations regarding the activities of the Ukrainian laboratories, leaving them with remaining concerns about U.S. and Ukrainian compliance (Russian Federation, 2022a). Accordingly, in October of the same year, Russia invoked Article VI of the BTWC, requesting that the United Nations (UN) Security Council initiate an investigation of the Ukrainian facilities. While Article VI allows states parties to make such requests, Russia’s proposal did not pass a subsequent Security Council vote, meaning no investigation was initiated.

Russia has a long history of spreading disinformation (false information that is spread deliberately to cause harm) about biological weapons to sow distrust in and among the U.S. government and its allies (U.S. Department of State, 2023). Russian (and formerly Soviet) officials have in fact falsely accused the United States of developing or using biological weapons for over half a century. In the 1950s, the Soviet Union, together with North Korea and China, falsely accused the United States of using biological weapons during the Korean War (Leitenberg, Reference Leitenberg2020). In the 1980s, the KGB, together with the East German Ministry for State Security, launched the disinformation campaign known as “Operation Denver,” using news outlets to spread the idea that the emerging HIV/AIDS pandemic was the result of clandestine biological weapons experiments overseen by the Pentagon (Selvage, Reference Selvage2019). More recently, Russian biological weapons disinformation has focused on U.S. cooperative biological activities abroad, particularly those carried out in former Soviet republics through the CTR Program. In 2009, for example, following the Russian incursion into Georgia, the Russian government initiated what would turn into a years-long disinformation campaign about alleged biological weapons development at the Richard Lugar Center in Tbilisi, which was built with funds from the U.S. CTR Program (Leitenberg, Reference Leitenberg2020). The Russian invasion of Ukraine was similarly accompanied by an onslaught of disinformation about U.S.-assisted laboratories in Ukraine (Cigar, Reference Cigar2023; Sundelson et al., Reference Sundelson, Trotochaud, Huhn and Kirk Sell2023). In addition to sowing division and reducing trust in the U.S. government, such disinformation campaigns have the potential to undermine cooperative biological activities that contribute significantly to global health security.

Russia also engaged in considerable disinformation efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic, using digital media to blame the United States for the pandemic and accuse it of creating SARS-CoV-2 as a biological weapon (Cigar, Reference Cigar2023; Nisbet & Kamenchuk, Reference Nisbet and Kamenchuk2021). Such efforts have contributed to a growing interest among scholars in understanding the danger posed by disinformation about biological threats (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Baez and Rutland2021; Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Bowsher, Sullivan and Gibson-Fall2021; Kosal, Reference Kosal2024; Sontag et al., Reference Sontag, Rogers and Yates2022), with some arguing that disinformation could be ushering in a new era of biological warfare, one in which naturally occurring disease outbreaks are co-opted for the purposes of deception and disruption (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Bowsher, Sullivan and Gibson-Fall2021).

Despite Russia’s long history of biological weapons disinformation efforts, their actions in 2022 were largely unprecedented, representing the second-ever invocation of Article V (the first being Cuba’s invocation in 1997) and the first-ever invocation of Article VI in the BTWC’s history. Since then, scholars and diplomats alike have grappled with the potential ramifications of these actions, with many arguing that Russia’s decision to invoke formal BTWC procedures on the basis of false allegations was an abuse of those provisions and risked undermining the Convention by reducing it to an instrument of disinformation (Attal-Juncqua et al., Reference Attal-Juncqua, Shearer and Gronvall2022; Lentzos & Littlewood, Reference Lentzos and Littlewood2022b; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Vogel and Gillum2022). As U.S. Special Representative Kenneth Ward put it in his opening statement at the Article V Formal Consultative Meeting:

The Russian Federation, by fabricating and circulating its lies, is seeking to exploit the Article V consultation mechanism to continue its efforts to falsely justify its war of aggression against Ukraine and to further its confrontation with the West. Russia’s use of the Article V consultation process for these reasons is an abuse of and, indeed, a disgrace to, that very process and an attack on the integrity of the Biological Weapons Convention (United States of America, 2022)

Notwithstanding the magnitude of Russia’s invocation of Articles V and VI, the events that occurred after these procedures could have even greater implications for the strength and functioning of the Convention. Indeed, Russia’s invocation of Article VI took place mere weeks before the Ninth Review Conference. Review Conferences, which are only held once every 5 years, are considered the official decision-making body of the BTWC. Accordingly, at the end of each Review Conference, a Final Document is produced in which states parties review the implementation of the Convention, elaborate their interpretation of its articles, and set a program of work for the upcoming intersessional period (the period between Review Conferences) (Littlewood, Reference Littlewood2021). Review Conferences therefore represent a critical (and infrequent) opportunity to ensure continued implementation and progression of the Convention. When their request for an investigation pursuant to Article VI was blocked, however, Russia proceeded to use the Ninth Review Conference as a forum to recapitulate their false claims. Additionally, in BTWC meetings since the Ninth Review Conference, Russia has only continued to steer the conversation back to the Ukrainian biolaboratories (Zanders, Reference Zanders2023).

Such ongoing attempts by the Russian Federation to sidetrack BTWC meetings with disinformation have the potential to undermine the Convention in several ways. First, there is the opportunity cost: a substantial amount of time may be taken up discussing Russian allegations at these meetings, limiting the ability of states parties to discuss other, more legitimate issues. Russia’s insistence on continuing to level false allegations in such meetings could also impact the types of proposals brought forward and the ability of states parties to reach consensus on issues that will further the aims of the BTWC. At the Ninth Review Conference, for example, Russia introduced two proposals for the Final Document that were clearly related to their allegations: one for a form for states parties to disclose information about biological activities carried out outside of their national territory (Russian Federation, 2022d) and another for the elaboration of procedures for investigating alleged breaches of the BTWC under Article VI (Russian Federation, 2022c). Such proposals put other states parties in the difficult position of having to choose between conceding to Russia, thereby legitimizing their false claims, or rejecting Russia’s proposals, thereby angering the Russian delegation and potentially reducing the chances of achieving consensus on other important issues.

The framing of Russian allegations in BTWC meetings (i.e., how the Russian delegation chooses to present their false claims) may also have important implications for the strength and functioning of the Convention. Framing is a theoretical construct that has been used across social science disciplines for decades. However, the exact definition and use of the construct has varied. Cornelissen and Werner (Reference Cornelissen and Werner2014) described these variations across three levels of analysis. At the micro level, framing analysis has focused on how individuals use mental models or “frames of reference” (March & Simon, Reference March and Simon1958) to process information. At the meso level (where the present analysis is situated), framing analysis has focused on how communicators frame issues strategically to influence audience perceptions and beliefs (see Creed et al., Reference Creed, Langstraat and Scully2002 for a discussion of this type of analysis). At the macro level, framing analysis has focused on how higher-level cultural frames or “templates of understanding” (Cornelissen & Werner, Reference Cornelissen and Werner2014, p. 183) drive institutional behavior and social or cultural change. Despite these differences, one overarching theory, backed by empirical evidence (see Cornelissen & Werner, Reference Cornelissen and Werner2014 for an overview), has persisted across disciplines: the notion that frames, whether held internally or presented externally, influence meaning making, actions, and beliefs. The frames that the Russian delegation employs when discussing their compliance concerns, in other words, are important to consider because they may influence how other states parties perceive Russian allegations, how they choose to respond to such allegations, and their confidence in the Convention as a whole.

While there has been some scholarly commentary on Russian disinformation in the context of the BTWC, including several reflections on the implications of Russia’s invocation of Articles V and VI (Attal-Juncqua et al., Reference Attal-Juncqua, Shearer and Gronvall2022; Lentzos & Littlewood, Reference Lentzos and Littlewood2022b; Zanders, Reference Zanders2023), to date, there has been little analysis of Russia’s ongoing disinformation efforts in BTWC meetings following the Article V and VI procedures (this issue is discussed briefly by Lentzos & Francese, Reference Lentzos and Francese2023b and Zanders, Reference Zanders2023). The aim of this analysis is to begin to fill this gap in knowledge by characterizing the volume (i.e., the amount of time spent discussing Russian false allegations and related content), consequences (including the specific proposals put forward and their inclusion or exclusion in the Final Document), and framing of Russian false allegations at the BTWC Ninth Review Conference.

Methods

Volume

Publicly available, multilingual recordings of the Ninth Review Conference (The United Nations Office at Geneva, n.d.) were used to assess the volume of Russian false allegations and related discussion. For the purposes of this analysis, volume was defined as the total amount of recorded time (in minutes) spent discussing Russian false allegations or related content by any state party, organization, or chairholder (i.e., the president of the Conference or the chair of a committee) present at the Review Conference. Russian false allegations were defined as claims originally emanating from the Russian Federation regarding alleged biological weapons activities taking place in either U.S.-assisted laboratories in Ukraine or at the Richard Lugar Center in Georgia. These claims have been refuted or dismissed as false by the governments of those accused (Georgia, 2022; U.S. Department of State, 2022), 42 other states parties that were present at the 2022 Article V Formal Consultative Meeting (Littlewood & Lentzos, Reference Littlewood and Lentzos2022), and experts and diplomats from 17 countries who participated in a 2018 transparency visit to the Richard Lugar Center (Georgia & Germany, 2018). Related content was defined as content connected to or resulting from Russian false allegations, such as discussion of Russia’s proposals related to their allegations or of Russia’s recent invocation of Articles V and VI. The first author listened to all available recordings in their entirety, listening to statements made in English or Russian in their original language. English-language recordings (using simultaneous interpretation provided by UN interpreters) were used to listen to statements made in languages other than English or Russian.

A spreadsheet was used to track discussion of Russian false allegations and related content during the Review Conference, with each entry in the spreadsheet corresponding to a statement made on or related to Russia’s allegations. Statements were categorized based on the type of discussion they represented: explicit discussion of Russian allegations (e.g., arguments that Russian allegations were disinformation, arguments that Russian allegations had merit or required further discussion, etc.), veiled discussion of Russian allegations (e.g., implicit references to unresolved “compliance concerns,” references to the recent rise in disinformation about peaceful biological activities, etc.), discussion of Russia’s two proposals related to their allegations, discussion of how to reflect Russia’s invocation of Articles V and VI in the Final Document, and discussion that took place in the context of a so-called point of order. A point of order is a procedural mechanism that allows any state party to interrupt another when they believe a rule of procedure is being violated. Statements that took place during a point of order were included in the assessment of volume if the interruption occurred when the speaker was discussing Russia’s false allegations (i.e., when the interruption was related to the discussion of Russian false claims). The time it took for the president or chair to respond to a relevant point of order was also included, as it contributed to the total time spent on the discussion of Russian allegations or related content. Explicit discussion of Russian allegations was further divided into two subcategories: (1) discussion in which Russian allegations were framed as legitimate (i.e., when such allegations were described as valid or warranting further discussion or action) and (2) discussion in which Russian allegations were framed as illegitimate (i.e., when such allegations were described as unfounded, politically motivated, unsubstantiated, or a form of disinformation). Timestamps were used to calculate the time it took (in minutes) for each speaker to complete their statement. All data from the spreadsheet were imported into RStudio for descriptive analysis.

Outcomes of the Review Conference

To assess the consequences of Russian false allegations, the first author used the available recordings to track all outcomes of the Review Conference that were connected to Russia’s false claims, including which proposals were included in the Final Document and which proposals did not achieve consensus. The first author also read publicly available official conference documents in detail, including drafts of the Final Document and working papers with proposals for the Final Document, to supplement the discussion contained in the recordings.

Framing

Qualitative analysis of conference transcripts was used to assess the framing of Russian allegations. Only statements made by the Russian delegation were included in this analysis. Automated English-language transcripts were available online alongside the recordings of the Ninth Review Conference. However, most (but not all) of the Russian delegation’s statements were made in Russian. As such, the first author created Russian-language transcripts by downloading audio files of the Russian delegation’s non-English statements and converting them to text using Google Cloud Speech to Text. All transcripts (in both English and Russian) were then edited for accuracy and clarity by the first author, who edited them while listening to the recorded statements in their original language. These transcripts were then imported to NVivo for codebook development and qualitative analysis.

The first author read through each transcript in its original language (Russian or English), using iterative open and axial coding (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2008) to develop and refine an inductive codebook over the course of 7 open coding sessions. The codebook development process was theoretically informed by the work of Entman (Reference Entman1993), who described framing as a means to “select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation” (p. 52). Accordingly, the final codebook contained five higher-level codes, each of which corresponded to a frame representing one or more of Entman’s constructs (a problem definition, casual interpretation, or moral evaluation of, or treatment recommendation for, alleged noncompliance with the Convention). Lower-level codes were used to delineate the constituent components of each frame, including specific details, narratives, and arguments. An additional higher-level code was used to identify discussion pertaining to the Final Document.

To mitigate the potential bias associated with using a single coder, once developed, the final codebook was used by the first author and a second researcher to code all transcripts. Each transcript was coded independently by both researchers, who then met to discuss and resolve any coding discrepancies. This method of coding, referred to as negotiated agreement, is beneficial when conducting exploratory qualitative research with coders who have different levels of subject-matter expertise (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Quincy, Osserman and Pedersen2013). The double-coding process was completed in three coding sessions. While clarifications to the codebook were made following the first two sessions, both coders agreed after each coding session that no material changes to the codebook were necessary. The automated English-language transcripts (with interpretation provided by UN interpreters) were used for coding given that the second coder did not have Russian language proficiency. However, the first author consulted the Russian transcripts throughout the coding process to ensure both coders were interpreting frames accurately. All quotes included below are from the automated English-language transcripts (which were edited for accuracy and clarity by the first author).

Results

The following sections provide an overview of the volume of Russian false allegations and related discussion during the Ninth Review Conference (a measure of opportunity cost), the consequences of such discussion (in terms of the outcomes of the Ninth Review Conference), and the ways in which the Russian delegation chose to frame their false claims.

Volume

A total of 184.95 recorded minutes (5.47% of total recorded conference time) were spent discussing Russian false allegations or related content at the BTWC Ninth Review Conference. As can be seen in Table 1, most of this time was spent on explicit discussion of Russian allegations, followed by discussion of how to reflect Russia’s Article V and VI invocations in the Final Document and points of order, respectively.

Table 1. Total recorded time (in minutes) and percentage of total recorded conference time spent on discussion of Russian false allegations or related content at the BTWC Ninth Review Conference, by category of discussion.

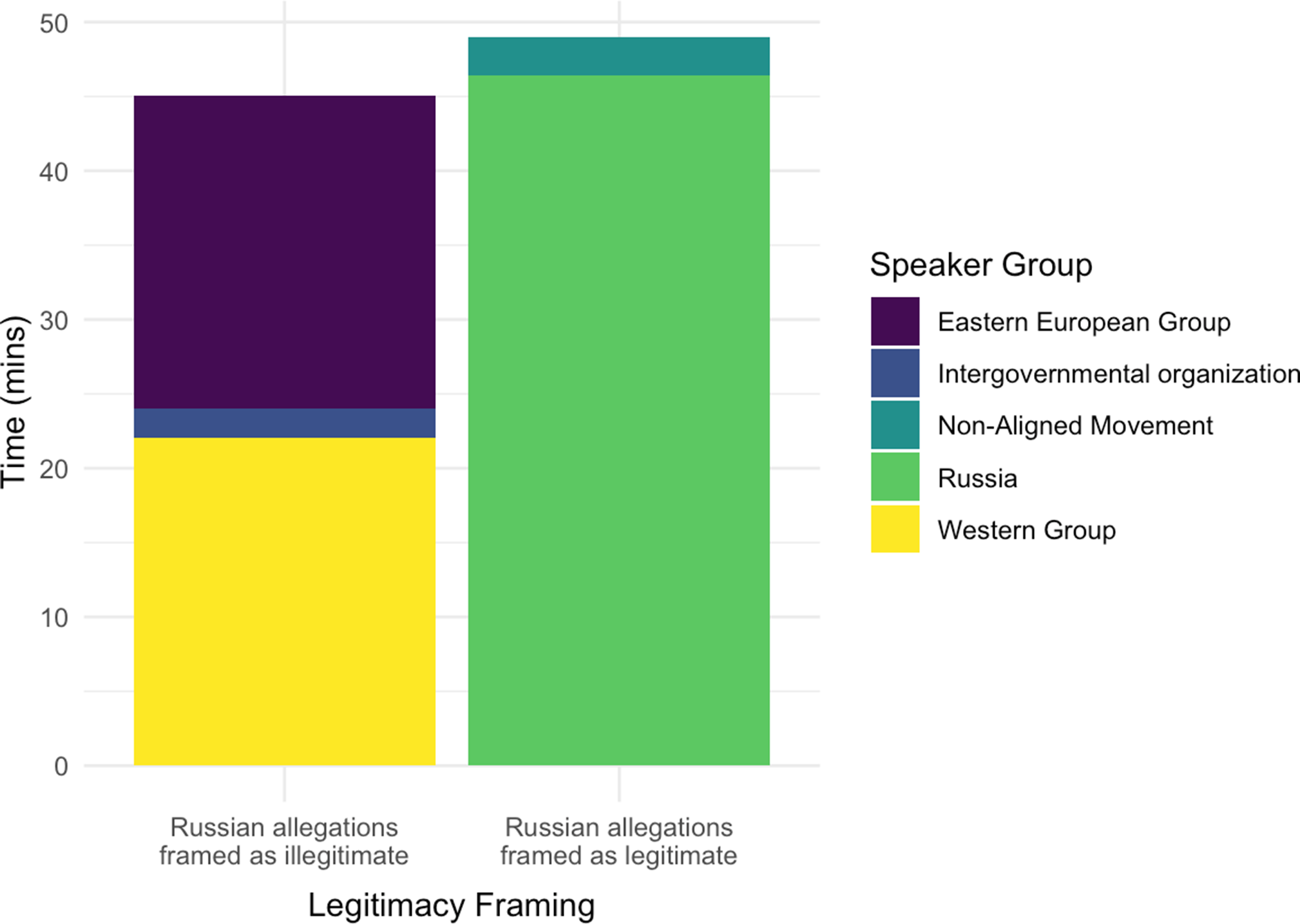

Figure 1 depicts the time spent discussing Russian false allegations or related content by speaker group (with states parties categorized according to their BTWC regional group) and category of discussion. As can be seen in the figure, Russia was the dominant speaker overall, spending a total of 83.5 minutes on discussion of their allegations or related content. However, members of the Western Group and Eastern European Group also spent a substantial amount of time discussing Russian allegations or related content (46.5 minutes and 29.2 minutes, respectively). The Non-Aligned Movement spent the least amount of time of all BTWC regional groups discussing Russian false allegations.

Figure 1. Time spent discussing Russian false allegations or related content at the BTWC Ninth Review Conference, by speaker group and category of discussion.

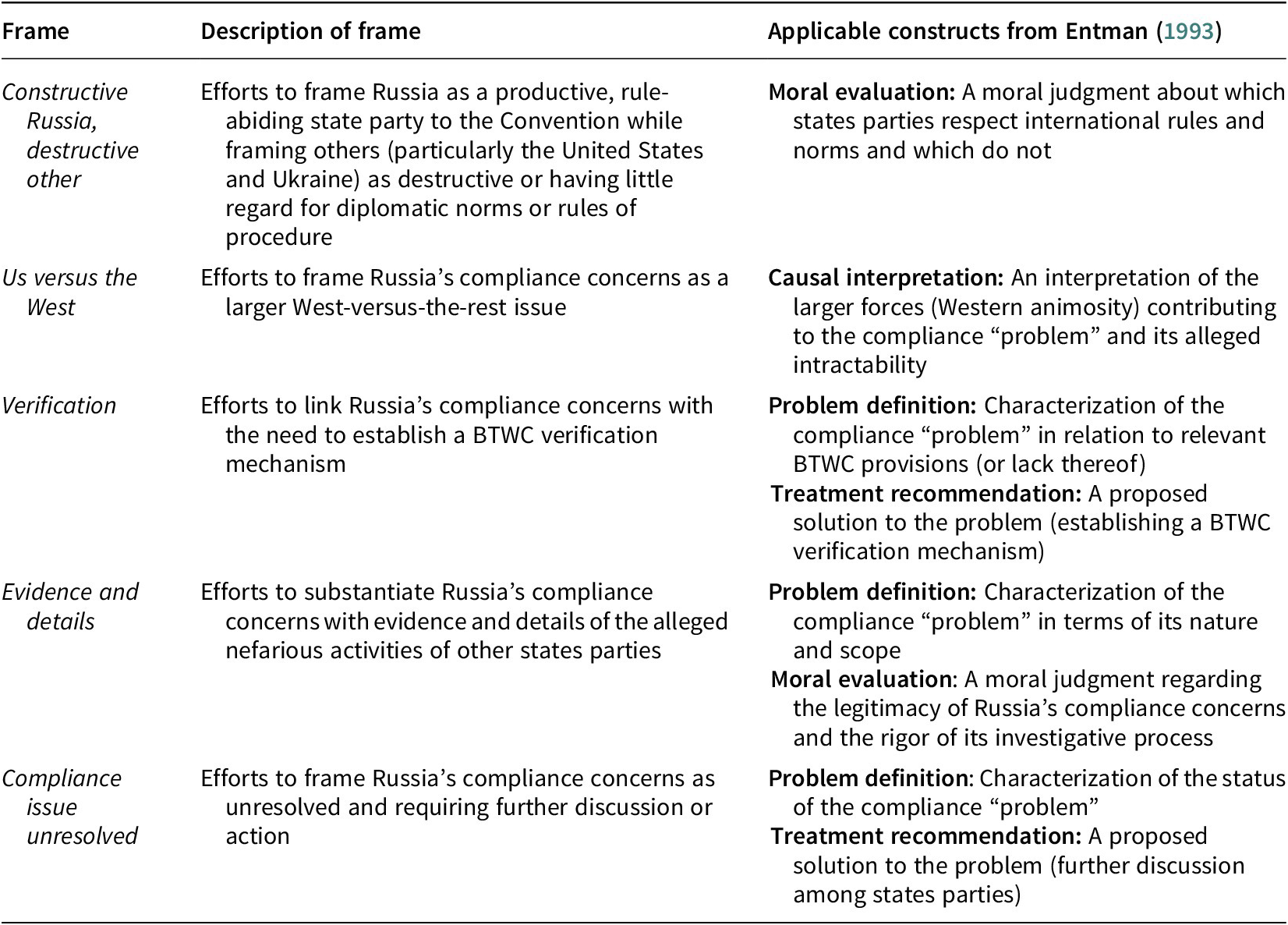

When examining the time spent on explicit discussion of Russian allegations (Figure 2), it is evident that a similar amount of time was spent framing such allegations as legitimate (49 minutes) compared to illegitimate (45.1 minutes). However, only Russia and China (the only member of the Non-Aligned Movement to spend time on explicit discussion of Russian allegations) framed Russian allegations as legitimate, while representatives from the Western Group, Eastern European Group, as well as intergovernmental organizations framed them as illegitimate. Together, states parties from the Eastern European Group and Western Group spent a total of 43.2 minutes framing Russian allegations as illegimitate, while Russia alone spent 46.4 minutes framing its allegations as legitimate.

Figure 2. Time spent on explicit discussion of Russian false allegations at the BTWC Ninth Review Conference, by speaker group and legitimacy framing.

Among those states parties that spent time framing Russian allegations as illegitimate, only two did so in statements lasting longer than 3 minutes (the United States and Georgia). In these statements, the United States and Georgia both made attempts to discredit or refute Russian allegations by providing alternative explanations for the biological activities in question or highlighting the Russian delegation’s evident lack of sincerity. The U.S. delegation, for example, argued that it was clear that Russia’s claims had been made in bad faith given their behavior at the Article V Formal Consultative Meeting (the Russian delegation circulated a draft document on the outcome of the meeting prior to ever hearing statements from the United States or Ukraine). In contrast, the other states parties that spoke against Russian allegations did so in short statements typically lasting less than a minute. Such statements were dismissive of Russian claims but largely void of any concrete argumentation. In these statements, many referenced the Article V Formal Consultative Meeting, arguing that Russian allegations had been discussed sufficiently at that meeting and that no further discussion was required.

Outcomes of the Review Conference

Several outcomes of the Ninth Review Conference were directly related to Russia’s false allegations. The first pertains to the participation (or lack thereof) of international and intergovernmental organizations. During BTWC Review Conferences, there is typically an agenda item allowing nongovernmental, international, and intergovernmental organizations to make statements relevant to the Convention. During this allotted slot at the Ninth Review Conference, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) attempted to make a statement on Russia’s “profoundly irresponsible campaign of disinformation” about the biological laboratories in Ukraine (December 29, 2022, afternoon session). In the midst of this statement, however, the Russian delegation lodged a point of order, arguing that the NATO representative was undermining the constructive nature of the Conference by refusing to adhere to “elementary diplomatic ethics” (December 29, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian). In addition, the Russian delegation argued that according to the rules of procedure, international and intergovernmental organizations did not actually have the formal right to make statements. This point of order resulted in an extended back and forth between the NATO representative (while attempting to complete their statement), the president of the Conference, and the Russian delegate, who insisted that no additional statements by intergovernmental organizations should be made. Ultimately, the president decided to postpone formal discussion of the issue and undertake informal consultations during breaks in the Conference. However, such consultations were unsuccessful, and all remaining international and intergovernmental organizations that had yet to make statements were prevented from doing so.

The Russian delegation also used their false allegations to justify sidelining several proposals submitted by other states parties. Panama, for example, introduced a proposal on incorporating a gender perspective in the implementation of the Convention, highlighting the need for equal participation by men and women in biological weapons nonproliferation efforts as well as the need to recognize the differential impacts of deliberate biological events on women and men (Panama, 2022). The Russian delegation, however, felt that states parties should be focusing on more pressing issues, namely their concerns about alleged violations by the United States and Ukraine of key articles of the Convention (Article I and Article IV). As the Russian delegate explained:

Then turning to the proposal of Panama, we have already presented our general position on the issue of gender in the context of the BTWC. I am not going to repeat it. We consider it very premature and inexpedient to focus the attention of states parties on matters which are not priorities in the context of the implementation of the Convention. As we have already said, there are much more serious matters which require the attention and the focus of states parties—not only their attention, but they require solutions to be found for the Convention to be able to function normally. Some of these matters directly concern issues linked to the implementation of key articles of the Convention, including Articles I and IV of the Convention. This is very serious, Madam Chair. (December 8, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

In addition, France, Senegal, and Togo jointly submitted a proposal for the establishment of an online biosecurity and biosafety platform through which countries could share best practices (France, Senegal and Togo, 2022). However, the Russian delegation was similarly dismissive of this proposal, arguing once again that the priority of the Conference should be to resolve their compliance concerns:

Then on the proposal of France, Senegal and Togo… we do not see any need to deal with issues which are not part of core of the implementation of the Convention. I mean issues of biosafety and biosecurity…. Let us deal first and foremost with the core tasks of the Convention, namely, again, the implementation of the key articles of the Convention, including Articles I and IV. In our opinion, we still have serious problems with these articles that require the closest attention from states parties, including the need to reach consensus on a series of matters in connection with the implementation of these articles. (December 8, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

Because the BTWC operates on the principle of consensus, one state party’s rejection of a proposal is enough to prevent that proposal from being included in the Final Document. Accordingly, the Final Document of the Ninth Review Conference contained no decisions or recommendations on incorporating a gender perspective nor on establishing the proposed biosecurity and biosafety platform (though both proposals were included in an annex) (Ninth Review Conference, 2022).

Russia’s false allegations also contributed to the loss of an entire section of the Final Document. This section, which is referred to as the Final Declaration, typically contains a review of the implementation of the Convention during the preceding intersessional period. During discussions on this section, specifically the paragraphs relating to the implementation of Articles V and VI, the Russian delegation insisted on including language indicating that their compliance concerns remained unresolved. Other delegations, however, including the U.S. and Ukrainian delegations, felt that it was sufficient to state that Articles V and VI had been invoked that year without going into further details about Russia’s alleged compliance concerns. This conflict contributed to a diplomatic impasse, leaving states parties unable to reach consensus on the Final Declaration. With time running short, the president ultimately decided to cut out the entire section, resulting in a stunted Final Document with no discussion of the implementation of the Convention during the intersessional period. The Russian delegation blamed this outcome squarely on “one country” (the United States), stating that,

We are quite disappointed that the position—destructive and politicized position of one country could not allow us to reach consensus on the usual Part II of the Final Document of the Review Conference. We could not reach consensus because one state party would not put any words in the Final Declaration with regard to Article V and VI in order to resolve the situation and reach the consensus needed with regards to military and biological activities in violation of the BTWC in Ukraine. We are disappointed with the fact that it would not be possible even to encourage states parties to reach consensus and to resolve this situation. And the victim of that was the Final Declaration of the Final Document. (December 16, 2022, afternoon session)

Framing

The research team identified five frames that were used by the Russian delegation when discussing their false allegations or related content. These frames are described in Table 2 and mapped to the relevant framing constructs described by Entman (Reference Entman1993). Each frame is also described in further detail below, alongside representative quotes.

Table 2. Frames employed by the Russian delegation when discussing their false allegations, mapped to applicable framing constructs described by Entman (Reference Entman1993).

Constructive Russia, destructive other

In this frame, the Russian delegation sought to portray their country as a productive, rule-abiding state party to the Convention—one that, unlike other states parties (particularly the United States and Ukraine), was committed to honoring and upholding international regulations and norms. For example, the Russian delegation often emphasized that Russia had invoked Article V in full accordance with its provisions and in good faith, believing that such an invocation would allow for productive dialogue that would ultimately resolve the issue related to the Ukrainian laboratories:

The Russian side operated under the assumption that the Consultative Meeting would allow interested delegations, with the support of their experts, to understand the situation in full, exchange opinions, ask professional questions, and, mostly importantly, receive detailed answers. During the meeting, the Russian side took all necessary steps to present its materials and arguments in detail so as to ensure that the Consultative Meeting could achieve its goals and settle the situation linked to the military biological activities in Ukraine. (December 1, 2022, morning session, translated from Russian)

In contrast, the Russian delegation framed the behavior of the United States, Ukraine, and their allies at the Formal Consultative Meeting as “destructive” and even flippant:

At the Consultative Meeting of states parties to the BTWC under Article V, Washington and Kiev gave no exhaustive responses to the legitimate questions that we raised, nor did we receive any substantive reaction to the documents and evidence presented to shed light on the true nature of the dealings of the Pentagon and its contractors with Ukraine in the military biological sphere. In view of the destructive policy of the United States and its allies, there was no follow-up to the Russian complaint. (November 28, 2022, morning session, translated from Russian)

The Russian delegation further demonstrated the “destructive” modus operandi of Ukraine and others by lodging points of order during their statements on or related to Russia’s false allegations, arguing that they were violating rules of procedure and undermining the important work of the Conference. For example, during a statement by Ukraine on the Formal Consultative Meeting and the larger implications of Russian disinformation, the Russian delegation interrupted several times, arguing that Ukraine was violating rules of procedure by showing disrespect to the Russian Federation:

Distinguished Madam Chair, we are forced once again to remind the delegation of Ukraine that in this forum, states parties are on equal footing, and we are all instructed to treat each other with mutual respect. However, the delegation of Ukraine has demonstrated on several occasions that it is flouting the rules of procedure, abusing your patience, distinguished Chair, and undermining the authority of this forum, demonstrating disrespect to the Russian Federation—and this is far from the first such instance of ignoring and neglect of the UN charter, in which all member states of the UN participate on equal footing. (November 30, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

Us versus the West

Throughout the Conference, the Russian delegation also made attempts to frame their compliance concerns as a larger West-versus-the-rest issue. For example, on several occasions, the Russian delegation claimed that only Western countries doubted the validity of their concerns regarding the laboratories in Ukraine. Furthermore, the Russian delegation argued that such countries were intent on stifling the opinion of others within the international community:

The Russian Federation categorically rejects any attempts by Western countries to call into question the convincing materials and arguments that we presented in the context of the violation by the United States and Ukraine of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention through military biological activities on the territory of Ukraine. Only Western countries contested the Russian documents and convincing evidence. We see in this yet another attempt by Western countries to present their own point of view as the view of the entire international community. This can only lead to disappointment. (November 28, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

The Russian delegation also described attempts by certain countries, specifically Western countries, to “hush up” questions about U.S. biological activities abroad: “The Ninth Review Conference confirms that only Western countries—the allies of the United States and no one else—are trying to quietly hush up awkward questions for them, but that won’t work” (November 29, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian).

Additionally, the Russian delegation argued that voluntary visits to biological laboratories that were the subject of compliance concerns (such as the 2018 visit to the Richard Lugar Center in Georgia) could not be considered a legitimate means to verify compliance because such visits were likely rigged by the same Western countries that promoted them:

The mechanism of voluntary visits that are being promoted by Western countries, the so-called peer review exercises, references to which we have heard numerous times from the Delegation of Georgia, have nothing to do with any assessment of compliance by states parties to the BTWC…. We have serious concerns related to voluntary peer review visits. We know very well that such visits are programmed in advance by Western countries. (November 28, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

Verification

In another frame, the Russian delegation sought to link their compliance concerns with the need for a BTWC verification mechanism, arguing that the unresolved nature of their concerns underscored the pressing need to adopt formal measures to assess compliance:

The lack of consensus on Russian claims means only one thing. This means that they persist and require resolution. It is necessary to establish the facts of the military biological activities in Ukraine. This highlights the urgent need for additional measures in the context of the Convention, including the formation of a legally binding mechanism for verifying obligations under the Convention. (December 1, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

Within this frame, the Russian delegation made frequent references to when the United States blocked a potential verification mechanism that had taken years to develop in July 2001. Though the U.S. delegation has since stated their interest in resuming negotiations toward a verification protocol, this fact was ignored by the Russian delegation, which argued that the United States showed continued resistance to adopting any form of verification:

This deplorable situation clearly confirms the vital need for genuine and not just theoretical strengthening of the Convention. Together with the vast majority of states parties, Russia is convinced that the effectiveness of the Convention would be significantly strengthened through the adoption a universal, legally binding, non-discriminatory protocol concerning all articles of the Convention with an effective verification mechanism. Unfortunately, the development of such an instrument, which would allow us to ensure sustainable implementation of the Convention and would prevent violations thereof, has, since 2001, been blocked without justification by the United States. We are in favor of resuming work on a protocol. (November 28, 2022, morning session, translated from Russian)

The Russian delegation also claimed that the United States’ alleged resistance to establishing a verification mechanism stemmed from their desire to continue conducting illicit biological activities abroad:

The Russian Federation is also disappointed that this one country continue[s] to block any possibility to resume the work on a legally binding instrument—protocol under the Convention with [an] efficient verification mechanism. It is more than 20 years that we are facing this situation, and this Review Conference was not the exclusion in this chain. We could not reach the consensus on resuming the work on a legally binding protocol because of the position of one state. That is totally disappointing. And we do see the reason for that. The reason is quite clear: just to hide and to let hands free to continue these military and biological activities in violation of the BTWC around the world [sic]. (December 16, 2022, afternoon session)

Evidence and details

In another frame, the Russian delegation described the allegedly nefarious biological activities carried out by the United States and Ukraine in extensive detail. According to the Russian delegation, such details, which were often gleaned (and subsequently misrepresented or misinterpreted) from official government documents or laboratory reports, left little doubt that the United States and Ukraine were acting in violation of the Convention. For example, in one statement, the Russian delegation described the types and quantities of pathogenic agents contained in a Ukrainian laboratory, arguing that such pathogens were not of public health relevance to Ukraine and were being stored in suspiciously large quantities:

The scale and focus of the military biological activities conducted in Ukraine are described most precisely by the report on the results of an assessment of strains of microorganisms at the Mechnikov Anti-plague Research Institute in Odessa on December 28, 2018. According to this document, in the institute, there were over 422 storage units with the causative agent of cholera and 32 storage units with the causative agent of anthrax. Noteworthy is the accumulation of a large number of test tubes with identical strains of different passages. In the absence of cases of mass outbreaks of these diseases in Ukraine in recent years, the nomenclature and accumulated volumes of bioagents call into question their designation for preventive, protective, or other peaceful purposes. (November 30, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

The Russian delegation also described several projects undertaken by the U.S. CTR Program in Ukraine in detail. In one statement, the Russian delegate claimed that the specifics of these projects indicated that the United States was interested in using birds and bats as a means to deliver biological weapons:

The documents which we have obtained contain a list of international projects executed in such laboratories in Kiev, Odessa, and Kharkov: UP-4, Flu Flyway, P-781, which study the potential to spread dangerous infections through migratory birds, including highly pathogenic influenza and Newcastle Disease, and bats, in particular, as a means to infect a person with plague, leptospirosis, and brucellosis, as well as coronaviruses and filoviruses; these can be seen as delivery vehicles. The strains were collected and the conditions under which transmission processes could become uncontrollable, cause economic damage, and create food security risks were assessed. The spatial scope of the projects actually included not only the Ukrainian regions bordering Russia, but also the territory of Russia itself. (November 30, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

In another statement, the Russian delegation described a patent application approved by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for a device that appeared to be a biological weapons delivery system:

Also unanswered is the question of the patent from March 3, 2015 that was issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for an unmanned aerial vehicle designed to disperse infected mosquitoes in the air, that is, for equipment or a product that is intended for use as a technical means of delivering and using “biological and immunobiological agents, bacteria, and viruses”—this is a quote from the patent—including those that are highly contagious and “could destroy all enemy troops”—this is also a quote from the document. In accordance with American legislation, a U.S. patent cannot be issued in the absence of an exhaustive description of the actual device. Therefore, you can draw the conclusion that the device as a means of delivering bioagents was developed and could be produced quickly. (December 1, 2022, morning session, translated from Russian)

In a small number of instances, other states parties felt the need to respond to the specific details mentioned by the Russian delegation. At one point in the Conference, for example, the Russian delegation described a request for information that was allegedly sent by a Ukrainian government agency to a Turkish drone manufacturer regarding the quantity of aerosolized material that could be loaded onto a drone. According to the representative from the Russian delegation, such a request was concerning given that the Russian armed forces had recently discovered drones in Ukraine that were capable of “spraying bioagents” (November 30, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian). Following these remarks, the Turkish delegation felt the need to make a statement clarifying that the drones from the manufacturing company in question were not in fact equipped with biological weapons delivery systems.

Compliance issue unresolved

In the final frame, the Russian delegation insisted that their compliance concerns remained unresolved and required further discussion, including during the Ninth Review Conference. This frame was often employed during discussion of Russia’s invocation of Article V and the resulting Formal Consultative Meeting, which, according to the Russian delegation, was not successful in establishing the necessary facts about U.S. and Ukrainian cooperative biological activities:

After the exchange of opinions between states parties, the Russian Federation noted that the vast majority of the questions put forward by it were not answered. As follows from the outcome report of the Consultative Meeting, consensus was not reached. These questions remain outstanding and need to be settled…. Steps need to be taken to establish all facts connected to violations by the United States and Ukraine of their commitments under the Convention. Until the questions we put forward are resolved, they will remain open on the platform of the Convention and undermine its implementation. (December 1, 2022, morning session, translated from Russian)

Within this frame, the Russian delegation argued that the Ninth Review Conference was not only a suitable forum in which to discuss their compliance concerns, but also one in which a decision should be made on how to resolve their concerns:

We still believe that the BTWC Review Conference is precisely the forum that should resolve problematic issues within the framework of the Convention… Therefore, this Conference should send a certain signal and provide certain guidelines for action for states parties on how to resolve these problematic questions that remain. (December 7, 2022, afternoon session, translated from Russian)

This frame was also used to foreshadow Russia’s intention to continue to discuss its false allegations beyond the Ninth Review Conference. For example, during the last session of the Conference, the Russian delegation stated:

We will continue seeking answers to the outstanding issues and questions with regard to the military and biological activities in violation of the BTWC in Ukraine. We will continue urging the United States and Ukraine to settle this unacceptable situation undermining the implementation of the Convention. (December 16, 2022, afternoon session)

Discussion

This analysis demonstrates that a substantial amount of time (over three hours) was spent discussing Russian false allegations of noncompliance or related content at the BTWC Ninth Review Conference. The Review Conference took place over the course of 15 days, with each day scheduled to have two 3-hour formal sessions. Discussion of Russia’s allegations and related content, in other words, took the equivalent of an entire formal session. Given that (a) Russia’s allegations are unfounded and (b) an entire separate BTWC meeting to discuss such allegations was already held, the time spent re-discussing them during the Ninth Review Conference can in some ways be considered time wasted. After all, Review Conferences only occur once every five years and remain the main decision-making body of the BTWC, leaving states parties with a limited window of opportunity to make concrete decisions on strengthening the Convention. Spending any amount of time at a Review Conference on the discussion of disproven, politically motivated allegations is therefore concerning. It should also be noted that only sessions that were publicly available and recorded were considered in this analysis; the time spent discussing Russia’s compliance concerns in private sessions or informal consultations was not included in the assessment of volume. As such, the total time presented in this analysis is likely an underestimate of the true amount of time spent discussing Russian allegations at the Ninth Review Conference.

When examining which states parties and regional groups spent the most time discussing Russian allegations or related content, it is unsurprising that the Russian Federation dominated. However, states parties in the Western Group and Eastern European Group also spent a considerable amount of time on Russia’s compliance concerns, particularly on explicit discussion of such concerns. In fact, together, the Eastern European Group and Western Group spent almost the same amount of time on explicit discussion of Russian allegations as the Russian delegation itself. The Russian delegation, of course, spent that time framing their allegations as legitimate, while the Eastern European Group and Western Group spent their corresponding time framing Russian allegations as illegitimate. The time spent discussing Russian allegations by the Eastern European Group and Western Group can be seen in both a positive and negative light. On the one hand, research has shown that claims (even those that are implausible) are more likely to be perceived as true the more they are repeated (Fazio et al., Reference Fazio, Rand and Pennycook2019). This phenomenon is likely one that the Russian Federation seeks to exploit. Indeed, BTWC Review Conferences are attended not only by delegates from states parties, but also by members of the press, youth delegations, and representatives from various academic and civil society organizations, providing the Russian Federation with a diverse and potentially impressionable audience to persuade with its never-ending barrage of falsehoods. It is thus somewhat reassuring to note that during the Ninth Review Conference, Russia’s efforts to frame their baseless allegations as legitimate were accompanied by equally lengthy efforts to frame them as illegitimate.

However, it is unclear whether the statements made by representatives from the Western Group or Eastern European Group were effective in countering Russian claims. The correction or refutation of false information (also known as debunking) is complex and does not always work, meaning some may still believe false information even after attempts to refute it (Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Ecker, Seifert, Schwarz and Cook2012; Nyhan & Reifler, Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010). Furthermore, debunking is more likely to be effective when detailed refutations and alternative explanations are provided (as opposed to simply stating that a claim is false) (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Jones, Hall Jamieson and Albarracín2017; Ecker et al., Reference Ecker, Lewandowsky and Apai2011; Johnson & Seifert, Reference Johnson and Seifert1994). While detailed explanations of U.S. and Ukrainian cooperative biological activities were provided during the Formal Consultative Meeting (an event that was closed to the public), most of the statements made by representatives from the Eastern European Group and Western Group at the Ninth Review Conference were brief and simply dismissive of Russian claims. As a result, such statements may not have done much to alleviate any concerns raised by the Russian delegation and may have simply taken up valuable time.

Additionally, some attempts to denounce or refute Russian allegations only resulted in further disruption to the meeting. The statement by the NATO representative, for example, resulted in a lengthy exchange between the Russian delegation and the president of the Conference, one that ultimately stripped the remaining intergovernmental organizations of their opportunity to make statements at all. Unfortunately, the participation of intergovernmental organizations in BTWC meetings has continued to be a topic of debate well beyond the Ninth Review Conference, and nongovernmental organizations seem to have become collateral damage. At the 2023 Meeting of States Parties, for example, the Russian Federation refused to adopt the rules of procedure unless it was established that intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations would not be able to make oral statements. During their intervention, the Russian delegation specifically referenced NATO’s statement from the Ninth Review Conference, arguing that it represented an abuse of the privileges given to such organizations. Other states parties, however, felt that it was important for intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations to be able to make statements. As a result, the meeting could not move forward, and delegations were forced to wait while the chair of the Conference attempted (unsuccessfully) to resolve the issue through informal consultations. These events represent not only a significant waste of time and financial resources (with delegates paying to travel to Geneva only for the meeting to be stalled), but also a threat to the integrity and inclusivity of the Convention, which benefits greatly from the participation of intergovernmental and civil society organizations.

Of course, the participation of intergovernmental organizations was not the only casualty of the Ninth Review Conference stemming from Russia’s false allegations. In fact, the Russian delegation used their false claims to sideline several proposals for strengthening the Convention, including the proposal to incorporate a gender perspective in the implementation of the Convention and the proposal to establish an online biosecurity and biosafety platform. Such proposals would have undoubtedly contributed to a stronger Convention, one in which the importance of gender was recognized and through which biosecurity and biosafety best practices could be more easily shared. In addition, Russia’s insistence on including language in the Final Document about the “unresolved” nature of their compliance concerns led to the removal of an entire section—a section that contained numerous additional promising proposals. Such outcomes underscore that Russian disinformation can be a real impediment to strengthening the BTWC—a treaty that some argue is already “languishing at a critical time” (Lentzos & Littlewood, Reference Lentzos and Littlewood2022a).

The implications of the framing of Russian allegations also warrant discussion. It is evident that some of the frames employed by the Russian delegation were aimed at legitimizing their allegations in the minds of other states parties (or others present at the meeting). The evidence and details frame, for example, was clearly meant to persuade others that Russian claims were credible and could be backed up by hard evidence. Many of the specific details presented in this frame were also presented at the Formal Consultative Meeting, during which the Russian Federation attempted to build a convincing case (Russian Federation, 2022b). At both meetings, the specific details that were included were likely chosen for their potential to raise suspicion. The U.S. government’s approval of a patent for a device capable of dispersing infected mosquitoes over enemy territory, for example, could certainly seem suspicious, especially to those unfamiliar with the minutia of U.S. patent law (under which the approval of a patent does not make it legal to produce or use the patented device).

The verification frame may have also been designed to confer legitimacy to Russian claims, as numerous states parties are in favor of developing a formal verification mechanism. By drawing a connection between their allegations and the legitimate need for a verification mechanism, in other words, the Russian delegation may have sought to improve their standing among other states parties and possibly even garner support for their false claims. In a similar vein, Russia’s frequent references to the United States’ alleged opposition to verification were likely designed to legitimize the notion that the Unites States had—and continues to have—nefarious intentions. In this context, the fact that the U.S. delegation did block efforts to develop a verification mechanism in 2001 only works in Russia’s favor. Scholars have identified a similar frame in Russian discourse outside of the Ninth Review Conference. Lentzos and Francese (Reference Lentzos and Francese2023a), for example, noted its presence in a joint statement by Xi and Putin during the 2022 Olympic Games, highlighting that the “widely accepted narrative of the need for a legally-binding protocol [to the BTWC] was carefully linked with the narrative of compliance concerns… again conflating the two narratives, potentially widening their appeal and increasing their legitimacy.” The use of this frame in a joint statement with the Chinese president highlights its potential appeal to other states parties, particularly those that have been vocal about the need to adopt a formal verification protocol.

While it may be unlikely for the frames discussed above to fully convince states parties that Russia’s claims are legitimate or that the United States and Ukraine are acting in violation of the Convention, they may nevertheless sow seeds of doubt. Such seeds, no matter how small, are dangerous given that the BTWC is, in essence, a codified taboo. Indeed, as Lentzos (Reference Lentzos2018) has argued, Russia’s claims, if perceived as legitimate, could erode that taboo by giving the impression that compliance with the Convention is not universal. As a result, various state actors may begin to think about the potential strategic benefits of acquiring an offensive biological weapons capability, either as a form of deterrence or as a means to achieve their geopolitical objectives. Given recent advances in biotechnology and synthetic biology (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018), the consequences of such offensive programs could be catastrophic (Schoch-Spana et al., Reference Schoch-Spana, Cicero, Adalja, Gronvall, Kirk Sell, Meyer, Nuzzo, Ravi, Shearer, Toner, Watson, Watson and Inglesby2017).

Other frames appeared more designed to stoke divisions among states parties than to confer legitimacy to Russian allegations. The clearest example is the us versus the West frame, in which the Russian delegation sought to situate their compliance concerns within a larger narrative of Western aggression. The various claims included in this frame, particularly the claim that Western countries were attempting to present their opinion as the opinion of the entire international community, may have resonated with delegates from countries with strong anti-Western or non-aligned sentiment, including those with a history of colonization by Western powers (i.e., countries that have long felt that the collective West was trying to speak for them). Russia’s attempt to frame the United States and other (often Western-aligned) nations as a collective destructive force with little regard for diplomatic norms or rules of procedure was also likely designed to stoke divisions. In fact, the constructive Russia, destructive other frame may have similarly resonated with delegates from countries with a history of colonization by—or conflict with—Western nations, who may feel that Western countries are intent on bypassing international rules in favor of establishing their own rules-based system. This very sentiment has been expressed by scholars across the Global South, who have described ongoing attempts by Western actors to “construct and reconstruct the norms of international law in their favor” (Ikejiaku, Reference Ikejiaku2014, p. 338). Given that the BTWC operates on consensus, such attempts by the Russian delegation to stoke divisions are problematic, potentially making it more difficult for states parties to come to agreement on proposals, especially those submitted by Western or Western-aligned states.

The potential implications of the compliance issue unresolved frame are also worth noting. This frame certainly made it possible for the Russian delegation to justify their repeated (and likely future) attempts to steer the conversation back to the Ukrainian laboratories, no matter how many times the U.S. and other delegations emphasized that they considered the matter resolved. Other frames were also likely aimed at keeping the conversation centered on Russia’s compliance concerns. Many of the details discussed in the evidence and details frame, for example, were likely chosen because they were provocative in nature, making other states parties more likely to respond in statements of their own. The fact that the Turkish delegation felt the need to respond to Russia’s statement regarding the drones allegedly capable of spraying bioagents is evidence that this frame served its intended purpose. Given the success of these frames at the Ninth Review Conference, the Russian delegation is likely to continue using them in future BTWC meetings.

Limitations

This study should be considered in view of several limitations. First, as mentioned above, only publicly available, recorded sessions were used to assess both the volume and framing of Russian false allegations at the Ninth Review Conference. Six of the 30 scheduled formal sessions were either fully or partially closed to the public, and an unknown number of informal consultations took place that were not recorded. It is possible that during these sessions, additional discussion of Russian allegations took place and additional (or different) frames were employed by the Russian delegation. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that several components of this analysis, namely the assessment of the volume and consequences of Russia’s allegations, were conducted solely by the first author. However, when assessing any statements or documents that were not explicitly clear, the first author consulted with other scholars in the field (including those who were present at the Ninth Review Conference), limiting the potential for misinterpretation.

In addition, while Russian disinformation certainly had an impact on the outcomes of the Ninth Review Conference, it is difficult to disentangle the effects of disinformation from the effects of the larger geopolitical climate in which such disinformation occurs. For example, the Russian delegation may still have interrupted the NATO representative even if their false allegations had not been mentioned, if only because of NATO’s role in the war in Ukraine. Regardless, disinformation appears to be an important component of the strategic maneuvering that occurs in multilateral settings, serving as a tool that states can employ to achieve their broader geopolitical goals. Finally, it is important to note that the framing analysis in this study was not causal in nature. As such, the proposed implications of the frames employed by the Russian delegation should be interpreted with caution. In future studies, researchers could explore these implications in a more empirical manner. Experimental simulations, which have been used previously to assess the impacts of information operations (Ackerman et al., Reference Ackerman, Sundelson and Wetzel2024), offer a promising methodology for this future work.

Conclusions and recommendations

This analysis illustrates that Russian disinformation efforts during the BTWC Ninth Review Conference had numerous negative effects, including the loss of valuable time, sidelined proposals, and a stunted Final Document. The framing of Russia’s false allegations at the Review Conference may be associated with additional negative consequences, including increased division and suspicion among states parties. Given that Russia is unlikely to cease such disinformation activities in the immediate future (Lentzos & Francese, Reference Lentzos and Francese2023b; Zanders, Reference Zanders2023), targeted action is required to safeguard the BTWC moving forward. In an ideal world, such action would involve implementing changes to BTWC procedures and structures, such as limiting the ability of states parties to repeat allegations already discussed in a Formal Consultative Meeting (Siegmann, Reference Siegmann2024), ensuring the right of intergovernmental and nongovernmental organizations to make oral statements during all BTWC meetings, and developing a robust verification mechanism capable of quashing ill-founded allegations. However, given today’s geopolitical climate, the likelihood of achieving consensus on any of these issues in the near feature is low.

A more pragmatic approach may be to develop training or briefing materials on Russian disinformation for delegates attending future BTWC meetings. Such materials could contain guidance on when and how to debunk false claims, ensuring any future attempts to refute Russian allegations are both maximally effective and minimally disruptive. Guidance of this kind already exists and could be adapted to better fit the BTWC context (Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Cook, Ecker, Albarracín, Amazeen, Kendeou, Lombardi, Newman, Pennycook, Porter, Rand, Rapp, Reifler, Roozenbeek, Schmid, Seifert, Sinatra, Swire-Thompson, van der Linden and Zaragoza2020; United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute, 2023). Given that Russian disinformation broadly consists of repeated tropes (EUvsDisinfo, 2022), briefing materials could also include information on the narratives and frames that the Russian Federation is expected to employ in upcoming BTWC meetings, as these will likely mirror those employed during the Ninth Review Conference. This form of pre-emptive warning and refutation, often referred to as inoculation or prebunking, has been shown to confer psychological resistance against future attempts to manipulate or deceive (Lewandowsky & van der Linden, Reference Lewandowsky and van der Linden2021; Roozenbeek et al., Reference Roozenbeek, van der Linden and Nygren2020). Such briefing materials could be distributed to both delegates and others planning to attend BTWC meetings, conferring broad resistance to Russian information manipulation. Regardless of the chosen approach, care should be taken to ensure any counter-disinformation activities are led and conducted by a geographically diverse group of partners, including those from the Global South. Such an approach will reduce the chances of the Russian Federation weaponizing counter-disinformation efforts by framing them as another Western plot to influence international opinion.

Competing interest

Gigi Gronvall is on the Editorial Advisory Board of Politics and the Life Sciences.