Policy makers and academics disagree whether smaller populations are better for economic development. On the one hand, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have long warned of the economic challenges confronting population-scarce states. States with low population levels lack economies of scale. This condemns smaller states to higher per capita government expenditures (Alesina and Wacziarg Reference Alesina and Wacziarg1998), greater economic specialization (Bertram and Poirine Reference Bertram, Poirine and Baldacchino2018; Streeten Reference Streeten1993), and volatility (Armstrong and Read Reference Armstrong and Read2020; Briguglio Reference Briguglio1995; World Bank 2017). Small states’ bureaucracies are overstretched, underspecialized (Jugl Reference Jugl2019), and prone to corruption (Corbett Reference Corbett2015; Veenendaal and Corbett Reference Veenendaal and Corbett2015). Though states with fewer than one million residents represent almost a fifth of United Nations (UN) member states (Veenendaal and Corbett Reference Veenendaal and Corbett2015, 529), they constitute roughly a third of the World Bank’s 2021 list of states with high institutional and social fragility (World Bank 2021).

Others are more optimistic about small states’ development potential. States with smaller populations tend to have stronger social cohesion (Alesina and Spolaore Reference Alesina and Spolaore2003; Gerring and Veenendaal Reference Gerring and Veenendaal2020; Kuznets Reference Kuznets and Robinson1960; Read Reference Read, Briguglio, Byron, Moncada and Veenendaal2020). Their bureaucracies are more adaptable (Jugl Reference Jugl2019), innovative (Baldacchino Reference Baldacchino2010; Baldacchino and Bertram Reference Baldacchino and Bertram2009), and responsive (Congdon Fors Reference Congdon Fors2014; Rigobon and Rodrik Reference Rigobon and Rodrik2005).Footnote 1 Small-state policy makers can also mitigate the costs of smallness through trade liberalization (Alesina and Spolaore Reference Alesina and Spolaore2003; Armstrong and Read Reference Armstrong and Read1998; Leduc and Weiller Reference Leduc, Weiller and Robinson1960, 209; Milner and Weyman-Jones Reference Milner and Weyman-Jones2003), immigration (Corbett Reference Corbett2023, 199), and international alliances that lighten military, education, and healthcare spending (Read Reference Read, Briguglio, Byron, Moncada and Veenendaal2020).

Much of this debate, however, ignores that population size and economic development are endogenous. As low-population states attain higher levels of economic development, prosperity can grow their populations by lengthening life expectancy, curtailing emigration, and attracting immigration. Only examining the relationship between economic development and population size today overlooks yesterday’s states that grew demographically because of economic development. This omission biases the sample of commonly studied small states toward low-population states that are unwilling or unable to become bigger. This biased sample may lead scholars and policy makers to underestimate the developmental advantages of smaller populations.

We confront this omission by investigating how states’ past size can shape their current economic development. We argue that for states that gained independence shortly after World War II, population size in their early years of statehood guided two policies that would be vital to their post-Cold War prosperity: trade openness and public sector size. Low populations pressured leaders of smaller newly independent states to open their markets to international commerce because their domestic labor force produced a smaller variety of goods. Smaller populations also induced larger public sectors. This is because the minimum labor needed to govern and protect a modern state consumes a relatively larger share of smaller states’ local labor force. Newly independent states with smaller populations after World War II were therefore more likely to pair trade openness with large public sectors, “embedding” themselves into the global economy throughout the Cold War.

Open markets and large public sectors upheld smaller newly independent states’ post-Cold War development in two ways. First, larger public sectors promoted political stability by extending state patronage to a broader coalition of constituents. Second, because their economies were more dependent on international trade, leaders of smaller newly independent states were more likely to invest in institutions that promoted global commerce. These trade-enabling institutions were “inclusive” (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013, 74). They protected property rights, supported clean governance, and deepened human capital. As a result, smaller newly independent states were more likely to have built the institutional infrastructure to prosper in the post-Cold War era, an era marked by deepening globalization and mounting political instability (Obermeier and Rustad Reference Obermeier and Rustad2023).

We test this argument by examining the developmental trajectories of 83 states that gained independence between 1946 and 1975. Newly independent states with smaller populations during this period have had on average higher levels and rates of economic development in the post-Cold War era (1992–2020). Smaller newly independent states were also more likely to have open trade policies and large public sectors during the Cold War. These policies correlate with greater political stability and more inclusive economic institutions in the quarter-century after the Cold War.

We then exhibit the processes linking size at early independence and post-Cold War development with a most similar comparative case study of Oman and the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY or South Yemen). Like North and South Korea, Oman and the PDRY is a tragic case of neighboring states with innumerable preindependence similarities but diverging developmental outcomes today. We illustrate how varying population levels at independence—the PDRY’s population was twice as large as Oman’s—engendered contrasting Cold War trade and public sector policies. We then excavate these policies’ imprints on the chasm in post-Cold War development between Oman and South Yemen while accounting for confounding factors like oil and regime type.

Our findings contribute to three strands of scholarship. They are inspired by and aligned with Ruggie’s (Reference Ruggie1982) theory of embedded liberalism (EL): state intervention via welfare facilitates economic integration by compensating and insulating citizens harmed by global competition. The concurrent deepening of economic integration and gutting of social safety nets across the Global South has made some wonder whether EL was a high-income-country phenomenon. We follow Nooruddin and Rudra (Reference Nooruddin and Rudra2014) and present additional evidence that EL exists outside continental Europe. While small European states are flagship cases in the EL literature (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1985), we pave new ground by revealing that low populations drove many newly independent states outside Europe to adopt EL as well. More importantly, we uncover the developmental benefits of EL. Cold War EL helped to foster political stability and inclusive economic institutions in smaller newly independent states, laying the groundwork for their post-Cold War prosperity.

Second, we add to a robust literature on critical junctures and development. Leaders’ choices in critical moments can have long-term implications for states’ institutional development (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013; Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1991; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2001). The years shortly before and after independence are one such critical moment (Wantchekon and García-Ponce Reference Wantchekon and García-Ponce2024). States’ size in the early years of independence influenced their founding leaders’ choices of trade and public sector policies. These decisions formed a bedrock of political and economic arrangements that helped to steer diverging developmental trajectories half a century later.

Lastly, our analysis contributes to the study of small states. Recent scholarship argues that far from being vulnerable to the whims of globalization, smaller states have prospered in the post-Cold War era through innovative policies (Baldacchino Reference Baldacchino2010) and flexible boundaries (Corbett Reference Corbett2023). We unearth the historical demography behind this adaptability. Our work also reminds that we can learn a lot from formerly small states. In only studying states whose current populations fall below a contemporary demographic threshold of “smallness,” small-state scholars forgo a wealth of evidence from states that were once below that threshold. Formerly small states, many of which grew demographically because of economic success, can teach us a lot about size and development, and countless other outcomes.

Early Independence Size, Cold War Embedded Liberalism, and Post-Cold War Development

Summarizing the past two decades of scholarship on size and development, Gerring and Veenendaal (Reference Gerring and Veenendaal2020, 353) conclude that it is unclear whether size in the modern era is an asset or a liability for development. A major limitation of this scholarship, however, is that much of it ignores that economic development can also influence state size. Some of the most cited work on size and development regress a state’s level of development over a period of time on a measure of a state’s population size over that same time period (Alesina, Spolaore, and Wacziarg Reference Alesina, Spolaore, Wacziarg, Aghion and Durlauf2005, 1522; Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, De Kervenoael, Li and Read1998, 643; Congdon Fors Reference Congdon Fors2014, 38–42; Easterly and Kraay Reference Easterly and Kraay2000, 2016; Rose Reference Rose2006, 497–98). Econometric objections aside, these regressions may underestimate the developmental benefits of smaller states by overlooking states that grew demographically because of their developmental success. Case studies and policy reports on small states commit a similar error (OECD 2018). In restricting their analysis to today’s low-population states, they ignore the challenges and accomplishments of yesterday’s small states.

This points to a second limitation in the study of size and development. Most work on size and development disregards how states’ past size shapes their current development. Indeed, some argue that the past is less relevant to smaller states’ political economies (Campbell and Hall Reference Campbell and Hall2017, 5). This ahistoricism departs from canonical works on small states (Katzenstein Reference Katzenstein1985, 34; Kuznets Reference Kuznets and Robinson1960, 30) and development (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2001). Political and economic arrangements forged at critical moments in a state’s history can have long-term developmental ramifications. These arrangements can persist by setting norms and standards for future leaders to follow, and by cultivating special interest groups. Size may matter more for development at critical moments in a state’s history.

For states that obtained independence shortly after World War II, the first decades of sovereignty were one such critical moment (Wantchekon and García-Ponce Reference Wantchekon and García-Ponce2024). This early independence period augured these states’ first postindependence developmental policies. These policies stood on the shoulders of founding leaders. Though not drawn from a tabula rasa (Corbett Reference Corbett2023), they set precedents.

This era also provided unparalleled international peace for small states. Cold War politics and strong international norms of self-determination lessened smaller states’ vulnerabilities to foreign occupation. As a result, the Cold War era witnessed a surge in low-population states (Maass Reference Maass2017, 158). In this new Cold War era, small-state policy makers ruled with relatively less fear of invasion. They could invest more political and economic capital in their states’ first development policies. State size during this foundational period structured two policies with long-term developmental consequences: trade openness and public sector employment.

Trade Openness and Inclusive Economic Institutions

States with smaller populations generally have more open trade policies (Armstrong and Read Reference Armstrong and Read1998; Easterly and Kraay Reference Easterly and Kraay2000; Rigobon and Rodrik Reference Rigobon and Rodrik2005). Protectionism is politically and economically costlier in smaller states. Consumers in smaller states are more dependent on imports because local firms produce a narrower range of goods (Knack and Azfar Reference Knack and Azfar2003; Kuznets Reference Kuznets and Robinson1960). Producers in smaller states are more dependent on exports because their state’s small domestic market constrains expansion. As a result, while protectionism and import substitution industrialization were popular among many newly independent states after World War II, leaders of smaller states were more likely to welcome international trade instead (Haggard Reference Haggard1990; Herbst Reference Herbst2000, 142; Triffin Reference Triffin and Robinson1960).

Smaller newly independent states’ more open Cold War trade policies fueled higher post-Cold War development by catalyzing inclusive economic institutions. These are laws and agencies that lower barriers to economic participation. Inclusive economic institutions protect property rights, ensure the rule of law, and provide public services to give citizens the tools to capitalize on economic opportunity (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013, 74). These institutions are essential for economic development. Strong property rights promote growth by lowering transaction costs and encouraging investment (North and Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989). Public services like education, health, and infrastructure amplify human capital and productivity (Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2013).

Open markets can kindle more inclusive economic institutions (Al Marhubi Reference Al Marhubi2005; Gerring and Thacker Reference Gerring and Thacker2005; Sandholtz and Gray Reference Sandholtz and Gray2003). When the world is your market and hinterland, as the Singaporean adage goes (Huat Reference Huat, Roy and Ong2011), exporters and importers confront greater pressures to develop the capabilities to meet international trade standards. These pressures drove leaders of smaller newly independent states to begin building inclusive economic institutions. They invested in public education (Read Reference Read, Briguglio, Byron, Moncada and Veenendaal2020), established strong intellectual property rights regimes, and founded impartial courts and regulatory agencies. When the Cold War ended, smaller newly independent states were more likely to have already developed the institutional infrastructure to profit from the massive expansion of global commerce in the post-Cold War era.

Granted, open market policies do not necessarily create more inclusive economic institutions (Hellman, Jones, and Kaufmann Reference Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann2000; Knack and Azfar Reference Knack and Azfar2003). Multinational corporations, for example, can conform if not contribute to their host government’s weak rule of law. This is more likely to occur, however, in states with large domestic markets like China (Zhu Reference Zhu2017) or Egypt (Diwan, Keefer, and Schiffbauer Reference Diwan, Keefer and Schiffbauer2020). Multinational corporations should be less interested in subverting the rule of law in states with smaller domestic markets where the rewards of greater market access and a larger labor force are fewer.

Public Sector Size and Political Stability

Lower population levels also encouraged leaders of smaller newly independent states to employ larger public sectors. Smaller states have bigger public sectors relative to their size (Corbett Reference Corbett2023, 191; Randma-Liiv Reference Randma-Liiv2002; Read Reference Read, Briguglio, Byron, Moncada and Veenendaal2020). The labor needed to police, protect, and regulate a modern state occupies a relatively higher share of a smaller state’s labor force.

Larger public sectors buttressed smaller newly independent states’ post-Cold War development in two ways. First, smaller states’ larger public sectors facilitated trade openness by “embedding” or sheltering constituents who would be disadvantaged by international trade (Nooruddin and Rudra Reference Nooruddin and Rudra2014). Congruently, because public sector jobs employ a relatively larger share of smaller states’ native labor force, smaller states’ private sectors were more likely to lobby for open migration policies to keep private sector wages low. Lower private sector wages heightened citizens’ demands for public sector jobs, thus reinforcing domestic pressures for a large public sector, which in turn facilitated open trade and migration policies (Goodman and Pepinsky Reference Goodman and Pepinsky2021).

Second, as will be shown, larger Cold War public sectors promoted greater post-Cold War political stability. Public sector employment is a chief means of welfare in many underdeveloped economies (Nooruddin and Rudra Reference Nooruddin and Rudra2014, 607), where pensions cover less than a tenth of the working population. It is also a form of patronage (Corbett Reference Corbett2023, 209). Lower populations pressed leaders of smaller states to work with the local labor at hand. This meant recruiting civil servants and soldiers across preindependence political and social cleavages. Widely distributed patronage in the form of public sector employment helped to bend citizens’ loyalty toward their newly independent state’s leaders. These loyalties hardened with time, upholding smaller states’ political stability in the long run.

Smaller newly independent states’ larger Cold War public sectors laid a foundation of political stability as the number and intensity of violent conflicts grew in the early twenty-first century. While the post-Cold War era began with a steep decrease in conflict (Mack Reference Mack2007), this decline ended after the new century’s first decade. Weakening international order and the rise of a multipolar international system have fanned growing and intensifying conflicts (Obermeier and Rustad Reference Obermeier and Rustad2023, 9), civil wars (Davies, Pettersson, and Öberg Reference Davies, Pettersson and Öberg2023), and coups (Singh Reference Singh2023, 75). By spreading patronage broadly, larger Cold War public sectors anchored smaller newly independent states against the geopolitical maelstrom of the early twenty-first century.

Stability has helped smaller newly independent states to prosper in the post-Cold War era. Political instability amplifies policy uncertainty and economic volatility (Nooruddin Reference Nooruddin2010). This frightens local and foreign investment, both of which are crucial for the economic development of many newly independent states. As a result, countries with greater political stability tend to have higher levels of growth (Aisen and Veiga Reference Aisen and Veiga2013; Alesina et al. Reference Alesina, Özler, Roubini and Swagel1996).

Smaller newly independent states’ open trade policies and large public sectors endured even as the populations of some smaller states grew. Open migration policies with exclusionary political and social policies—what Goodman and Pepinsky (Reference Goodman and Pepinsky2021) call “exclusionary openness”—can sustain EL. So long as population growth does not expand the citizenry and dilute the public sector employment benefiting native citizens, leaders can open their borders to foreign goods and labor without undermining their protected constituents as their state’s population grows. Meanwhile, smaller newly independent states’ Cold War trade and public sector policies spawned local interests to protect these arrangements over time.

Figure 1 illustrates the argument. Newly independent states with smaller populations after World War II (XT-2, 1946–75) were more likely to adopt EL during the Cold War (ZT-1, 1976–91). These policies contributed to higher levels of post-Cold War economic development by buttressing political stability and building inclusive economic institutions (YT, 1992–2020).

Figure 1 Argument

These outcomes are probabilistic, not deterministic. Leaders of newly independent states had agency over their trade and public sector policies, irrespective of population size. Nor is early independence size the sole determinant of states’ post-Cold War development. Nevertheless, holding all else equal, we expect that newly independent states with smaller populations were more likely to adopt EL during the Cold War and prosper because of it after the Cold War.

This argument is also bounded to states born in the Cold War era, an era uniquely suited for small-state survival (Maass Reference Maass2017). It does not travel to post-Cold War states. Larger post-Cold War states were less likely to adopt the interventionist policies that were in vogue during the Cold War. This post-Cold War convergence in trade policy among large and small states minimizes smaller post-Cold War states’ developmental advantages today.

Early Independence Size and Post-Cold War Development: A Cross-Sectional Analysis

We test our argument by examining the development trajectories of states that became independent between 1946 and 1975 according to Correlates of War (COW) criteria (Pevehouse et al. Reference Pevehouse, Nordstrom, McManus and Jamison2020).Footnote 2 Among these states, we exclude those that lost their sovereignty after the Cold War, like East Germany and South Yemen. This produces a population of 83 newly independent states, whose median year of independence is 1961. Figure 2 colors all 83 newly independent states in our analysis in gray. Section 1 of the online appendix lists those states.

Figure 2 Map of Newly Independent States (1946–75)

State size in the early years of independence is the independent variable. A state’s early independence size is its average population between 1946 and 1975. Our historical population data stems from Gapminder (Maddison Project et al. 2019), which merges data from Bolt and colleagues (Reference Bolt, Inklaar, de Jong and van Zanden2018) and the UN Population Division (2024). We log the population variable because of its rightward skew.

We hypothesize that among newly independent states, smaller populations in the early years of independence correlate with greater post-Cold War economic development (H1). We bookend the post-Cold War era from 1992, the year after the Soviet Union’s dissolution, to 2020. We examine both levels and rates of post-Cold War development.

Our main measure of post-Cold War development is a state’s average GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity rates between 1992 and 2020, logged. We triangulate this measure with 2019 under-five infant mortality rates and human development index (HDI) scores (World Bank 2020).

Two outcomes reinforce smaller newly independent states’ greater post-Cold War development: inclusive economic institutions and political stability. The World Bank’s (2020) Rule of Law index is our chief indicator of post-Cold War inclusive economic institutions. This index is an annual aggregate score based on experts’ perceived confidence in the quality of a state’s property rights, contract enforcement, the police, the courts, and the likelihood of crime and violence. We average a country’s Rule of Law score from 1996, the earliest year these data are available, to 2019. We complement the Rule of Law measure with Transparency International’s (2019) Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), and the credit insurance company Credendo Group’s (2019) expropriation risk indicator. Combined, these measures’ disparate target audiences mitigate the inherent biases confined within each index.

To gauge post-Cold War political stability, we apply the Fund for Peace’s (2020) Fragile States Index. This index is a holistic expert-based evaluation of risks facing a country across four dimensions: political, economic, social, and cohesion. The index sums a country’s score across each index. The data for the Fragile States Index span from 2006 to 2020. We average states’ Fragile States Index scores during this period. We use an instability index calculated by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman and Angiolillo2022) dataset and the PRS Group’s (2022) political risk rating in robustness checks.

Our second hypothesis is that newly independent states with smaller populations were more likely to implement EL during the Cold War (H2). We first measure EL’s components separately. We assess states’ trade policy openness with the KOF de jure Globalization Index (Gygli et al. Reference Gygli, Haelg, Potrafke and Sturm2019). This historical index measures trade policy openness by considering states’ tariff and nontariff trade policies. We average states’ trade de jure globalization scores between 1976 and 1991. We measure Cold War public sector size in terms of government expenditures as a percentage of GDP (IMF 2022). Due to the scarcity of historical cross-national public sector expenditure data, we extend the analysis of Cold War public sector spending from 1976 to 1995. This measure is an average of public sector expenditures during this period. Lastly, we quantify states’ Cold War EL with an index that standardizes and adds the Cold War trade openness and public sector size variables. This index gives equal weight to these two components of EL. A higher score indicates greater Cold War EL. Section 2 of the online appendix provides more information on the political stability, inclusive economic institutions, and EL variables.

Many factors outside a newly independent state’s population size can impact its post-Cold War prosperity. Geography can strain state capacity (Herbst Reference Herbst2000). We control for population density (Pop. density, logged);Footnote 3 terrain ruggedness (Nunn and Puga Reference Nunn and Puga2012); and whether the state is an island, which correlates with cleaner governance (Congdon Fors Reference Congdon Fors2014). Malaria prevalence may have impacted levels of colonial settlement, with long-term implications for the quality of a newly independent state’s institutions (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson2001). We control for the average percentage of a state’s population at risk of malaria between 1965 and 1975 (Conley, McCord, and Sachs Reference Conley, McCord and Sachs2007).

Oil abundance also influences post-Cold War development. We control for a country’s average GDP from oil income between 1946 and 1975 (Haber and Menaldo Reference Haber and Menaldo2011).Footnote 4 We remove Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) states in a robustness check to ensure that oil-abundant small Gulf states are not driving our results. All our models use region fixed effects to account for region-specific determinants of development as well.

Economic development prior to independence is a strong predictor of postindependence development (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2010). Our models adjust for a state’s preindependence levels of economic development by controlling for their average urbanization rate between 1946 and 1975 (HYDE and Our World in Data 2023). This measure also helps to account for the impact of agriculture on newly independent states’ long-term prosperity (Streeten Reference Streeten1993).Footnote 5 We use historical GDP data derived from Bolt and colleagues (Reference Bolt, Inklaar, de Jong and van Zanden2018) to account for preindependence development in robustness checks. Given the more limited scope of these data, however, our main analysis applies urbanization rates as a proxy for early independence levels of economic development.

A large portion of smaller newly independent states are former British colonies (Gerring and Veenendaal Reference Gerring and Veenendaal2020, 36), which have outperformed former French colonies on average (Lee and Schultz Reference Lee and Schultz2012). We control for whether a state’s colonizer was BritishFootnote 6 and whether the state obtained independence through violenceFootnote 7 using the Issues Correlates of War’s Colonial History dataset (Hensel and Mitchell Reference Hensel and Mitchell2007). Our models account for external threats to sovereignty with a binary variable equal to one if a state experienced at least one interstate militarized dispute between 1946 and 1975 (Karreth Reference Karreth2022). We control for the share of years a country was an electoral or liberal democracy during this early independence era with V-Dem’s regime variable (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman and Angiolillo2022). Foreign aid may help or hinder development. Our models adjust for foreign support by controlling for states’ average aid per capita between 1960 and 1975, which we log because of the variable’s skew (OECD 2020).

Lastly, states with smaller populations tend to be more ethnically homogeneous (Alesina and Spolaore Reference Alesina and Spolaore1997; Gerring and Veenendaal Reference Gerring and Veenendaal2020). Ethnic homogeneity is positively associated with public goods provision (Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999; Easterly and Levine Reference Easterly and Levine1997). At the same time, ethnic diversity may be a function of economic development (Weber Reference Weber1976). We control for states’ ethnic diversity between 1946 to 1975 using Dražanovà’s (Reference Dražanovà2020) Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization. Given that ethnic homogeneity may be one pathway in which smaller size promotes economic development, adding this control likely generates more conservative coefficient estimates of the relationship between early independence size and post-Cold War development.Footnote 8

Our main models are ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regressions where for country i:

$$ {Y}_i={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\alpha +{\beta}_1\log {\left(\mathrm{Avg}.\mathrm{Population}\left(1946-75\right)\right)}_{\mathrm{i}}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\beta}_2{\mathrm{Controls}}_{\mathrm{i}}+{\beta}_3{\mathrm{Region}}_{\mathrm{i}}+\in i\end{array}} $$

$$ {Y}_i={\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\alpha +{\beta}_1\log {\left(\mathrm{Avg}.\mathrm{Population}\left(1946-75\right)\right)}_{\mathrm{i}}\\ {}+\hskip2px {\beta}_2{\mathrm{Controls}}_{\mathrm{i}}+{\beta}_3{\mathrm{Region}}_{\mathrm{i}}+\in i\end{array}} $$

Avg.Population is a newly independent state’s average population between 1946 to 1975. All control and independent variables use values from between 1946 and 1975. The dependent variable values are from years after 1975. See table 1 in the online appendix for summary statistics. All regressions use robust standard errors. We hypothesize β 1 to be negatively correlated with both post-Cold War economic development (H1) and Cold War EL (H2).

Table 1 Size at Early Independence and Post-Cold War Economic Development (H1)

Note: * p <0.1; ** p <0.05; *** p <0.01.

An OLS model is appropriate because both the dependent (post-Cold War development) and independent (early independence size) variables are continuous. We apply a cross-sectional model because each country has one theoretically relevant early independence size. Differences in early independence size are also much greater across countries than within countries during the early independence era (1946–75). Furthermore, we theorize and will demonstrate that the impact of early independence size on post-Cold War development is distinct from the developmental impact of size in subsequent years, because early independence is a foundational period in a state’s history. For these reasons, our main analysis eschews a longitudinal model with country fixed effects in favor of a cross-sectional one.

H1: Early Independence Size and Post-Cold War Development

Newly independent states with smaller populations at independence have had on average higher levels and rates of post-Cold War economic development (H1). Table 1 presents a negative association between states’ average early independence size and their post-Cold War development as measured by average GDP per capita (models 1 to 3), HDI (model 4), and infant mortality (model 5).Footnote 9 The negative coefficient estimate of the avg. population coefficient is robust to both parsimonious (model 1) and covariate abundant (model 3) models. This negative association remains after excluding influential and outlier observations.Footnote 10 The size of the avg. population coefficient is also substantively important. Model 3 estimates, holding all else equal, that a 1% increase in a newly independent state’s average population between 1946 and 1975 correlates with a 0.29% decrease in its average GDP per capita from 1992 to 2020. This implies that a doubling of a newly independent state’s early independence size is associated with a 29% lower post-Cold War average GDP per capita.

This negative association persists when assessing the relationship between early independence size and the rate of post-Cold War economic development, except with regard to change in HDI score (see table 4 in the online appendix). Early independence size remains negatively correlated with post-Cold War development even after excluding GCC states, India, and island states (appendix tables 5–7). This negative correlation endures when expanding the population of newly independent states to states that gained independence between 1946 and 1980 (appendix table 8) and using different post-Cold War start years (appendix table 9). The coefficient estimate of this association loses statistical significance, however, when using historical GDP data in models with all controls (appendix table 10), or controlling for year of independence under some model specifications (appendix table 11). These findings hold when restructuring the data into longitudinal form and running a random effects within-between (REWB) model (Bell and Jones Reference Bell and Jones2015; Jugl Reference Jugl2019, 123) (appendix section 3.3). Finally, and in line with theoretical expectations, newly independent states with smaller populations at independence have had more inclusive economic institutions (appendix table 13) and greater political stability (appendix table 14) in the post-Cold War era.

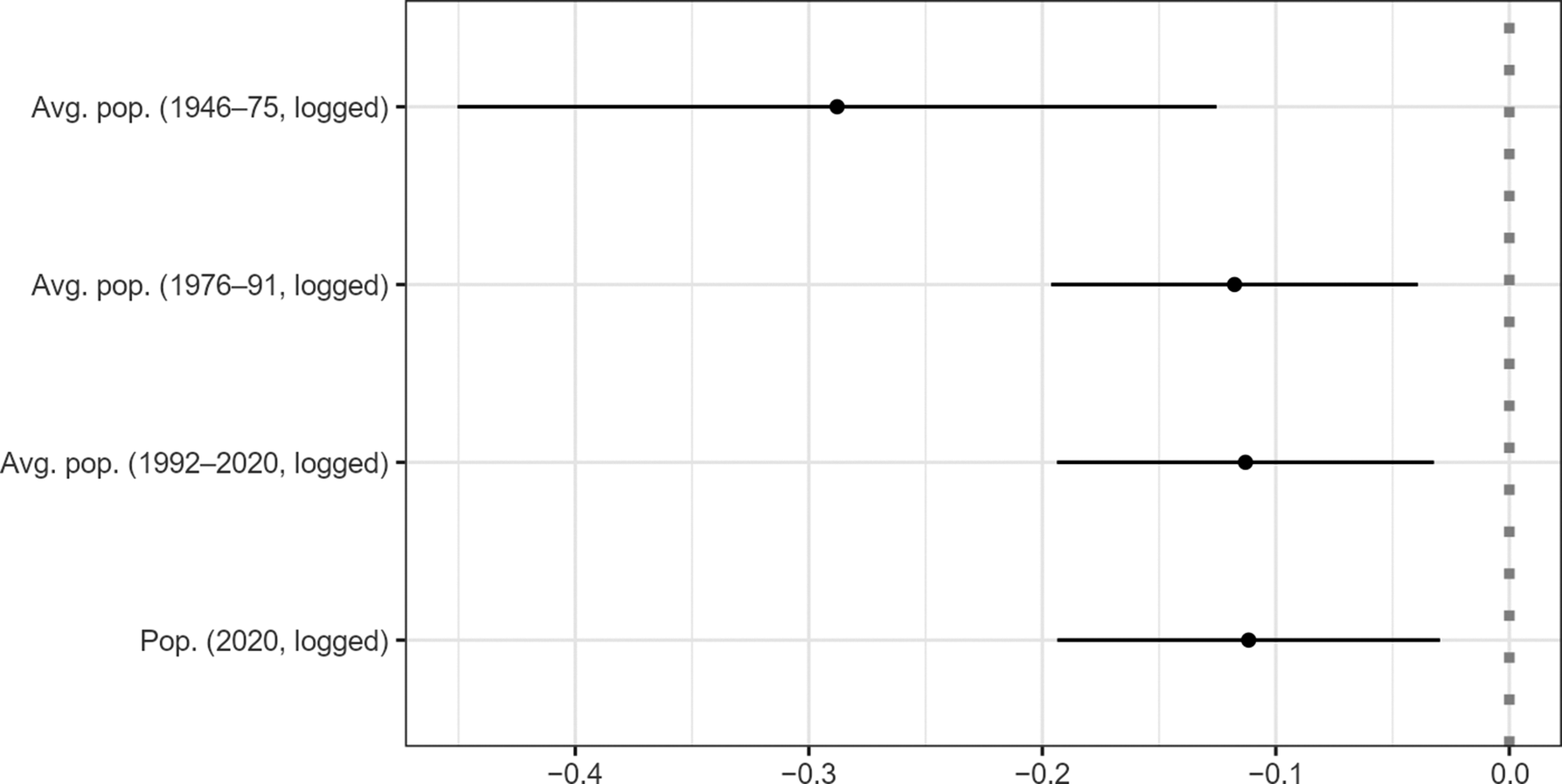

We argue that measuring the relationship between states’ current size and economic development underestimates the developmental benefits of smaller size by ignoring states that grew demographically because of economic development. If true, then the magnitude of the negative coefficient estimates of the relationship between newly independent states’ contemporary size and their post-Cold War development should be smaller than the coefficient estimate of these states’ early independence size and post-Cold War development.

Figure 3 confirms this implication. It plots coefficient estimates of population on post-Cold War development from model 3 of table 1 with different temporal measures of state size. The horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals, and x-axis values are coefficient estimates. The dotted vertical line captures a coefficient value of zero. The first row applies our main measure of state size: average population between 1946 and 1975. The second row measures state size as a population average between 1976 and 1991. The third row is a coefficient estimate for average size from 1992 to 2020, and the last row is size in 2020. All measures are logged. The magnitude of the negative association between size and post-Cold War development is almost twice as large when size is measured in the early years of independence (1946–75) than in subsequent periods. Which period scholars use to measure state size can substantially influence their estimate of size’s impact on development.

Figure 3 Coefficient Estimates of Size on Post-Cold War Development with Different Temporal Measures of Size

Smaller newly independent states’ population growth may account for some of these differences in coefficient estimates. While past size is generally a strong predictor of states’ current size—1976 population size can explain 99% of the variation in newly independent states’ 2020 population size—it is a much poorer predictor of smaller states’ contemporary size. Among the 28 newly independent states in this analysis with an average early independence size of fewer than one million, 1976 size explains roughly 20% of the variation in 2020 size (appendix table 24).

Economic success may have fueled the dramatic demographic growth of some formerly small states, particularly via immigration. Newly independent states with smaller populations between 1946 and 1975 have higher foreign migrants as a share of total population today and experienced greater post-Cold War rates of population growth (appendix table 15). Smaller newly independent states with greater developmental success are more likely to have grown demographically, exiting the population of contemporary low-population states. Their exit shrinks the magnitude of the negative coefficient estimate of contemporary size and post-Cold War development.

H2: Early Independence Size and Cold War EL

Newly independent states with smaller populations were more likely to adopt EL during the Cold War (H2). Early independence size is negatively correlated with Cold War trade openness, public sector size, and Cold War EL (appendix table 16). These policies have largely persisted in the post-Cold War era (appendix table 20).

Newly independent states’ early independence size shaped their post-Cold War development through the pathway of Cold War EL. Smaller states’ more open trade policies and larger public sectors nurtured inclusive economic institutions and political stability that solidified in the post-Cold War era. This bolstered greater post-Cold War economic development.

In support of these expectations, Cold War EL is positively associated with post-Cold War economic development (appendix table 17). In addition to GCC states, newly independent states with high Cold War EL scores and high post-Cold War economic development include Israel, the Maldives, and Singapore (appendix figures 2 and 3)—all states with relatively low population levels at early independence. More open Cold War trade policies correlate with more inclusive post-Cold War economic institutions as well (appendix table 18). The positive association between Cold War public sector size and post-Cold War political stability is positive but sensitive to certain model specifications (appendix table 19).

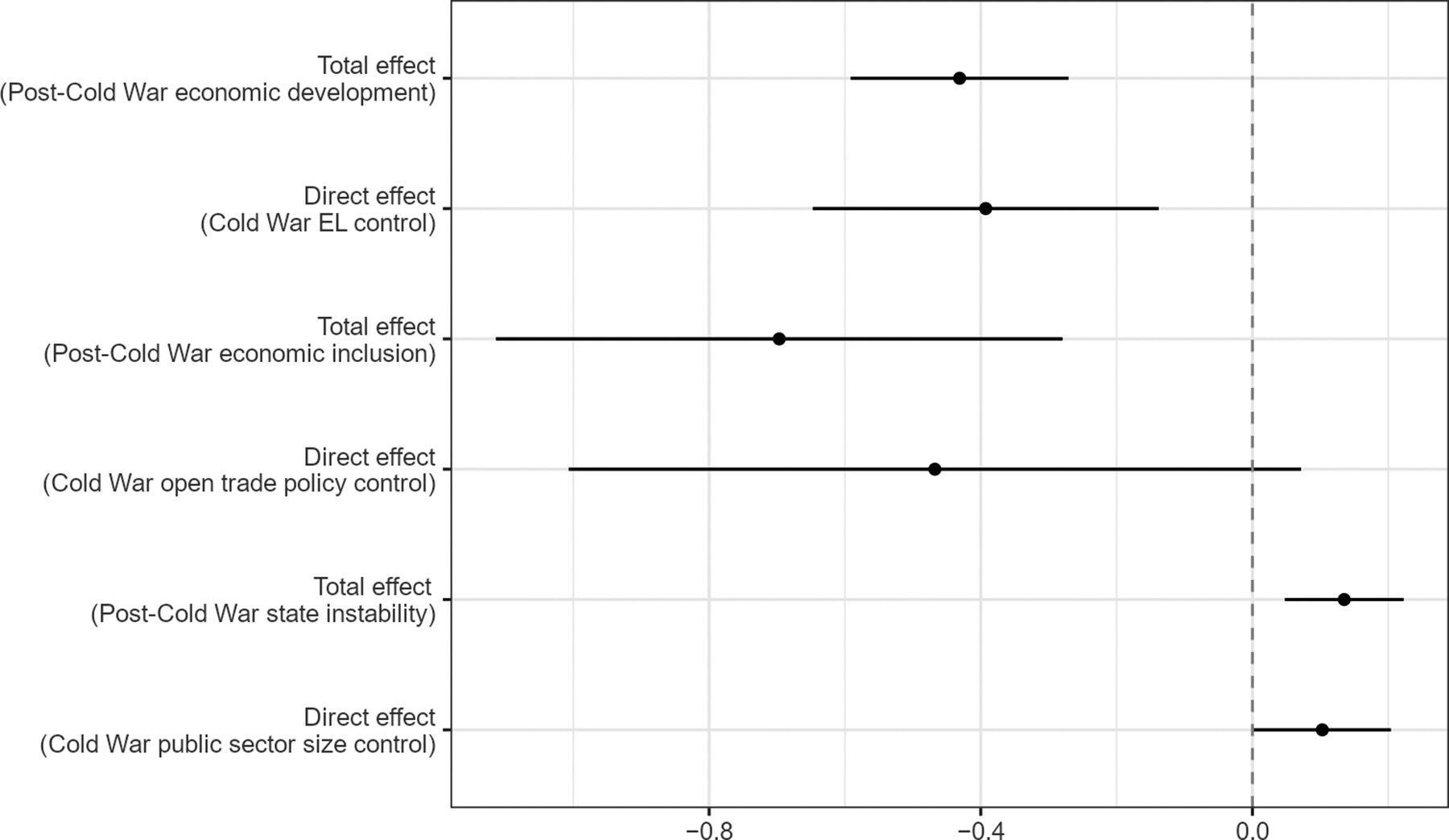

A mediation analysis provides additional but incomplete support of these patterns (appendix section 5).Footnote 11 Figure 4 plots changes in the coefficient estimate of early independence size on the three post-Cold War outcomes of interest (economic development, inclusive economic institutions, political stability) after controlling for their respective mediators (Cold War EL, trade policy openness, public sector size). Each model uses the analysis’s full controls. To facilitate estimate comparisons, we limit the analysis to observations with data on all mediators and outcomes. We also divide values for the political stability measure by one hundred to render the magnitude of its coefficient estimates to be of a similar scale as the economic development and economic inclusion estimates.

Figure 4 Mediation Analysis of Early Independence Size on Post-Cold War Outcomes

The total effect estimates are coefficient estimates without mediators. The direct effect estimates control for the mediator. If the magnitude of the direct effect estimate becomes smaller, and the coefficient estimate loses statistical significance, this suggests that the mediating variable is the main driver of the total effect.

Figure 4 offers two insights. First, controlling for Cold War EL has a marginal impact on the negative association between early independence size and post-Cold War development (rows 1 and 2). Factors outside of Cold War EL also contributed to the negative association between early independence size and post-Cold War development. The separate policy components of EL, however, seem to mediate the relationship between early independence size and post-Cold War inclusive economic institutions and political stability (rows 3 to 6). Neither estimate is statistically significant at the 5% level after controlling for the mediators of Cold War trade policy (row 4) or public sector size (row 6).

Second, Cold War trade policy has a larger impact on post-Cold War outcomes than the other two mediators. The magnitude of the negative coefficient estimate of early independence size on post-Cold War economic development decreases by almost a third in the mediation analysis, and by almost a half after controlling for Cold War trade policies in our cross-sectional analysis (appendix table 22). By promoting inclusive economic institutions, Cold War open trade policies may be the most important driver behind smaller newly independent states’ greater post-Cold War prosperity.

The preceding results present associations between early independence size and post-Cold War development. Causally identifying the relationship between size and any political or economic outcome is difficult (Gerring and Veenendaal Reference Gerring and Veenendaal2020, 33). These states’ independence was neither inevitable nor random (Lawrence Reference Lawrence2013). Developmental potential likely influenced their leaders’ choice and ability to become independent (Armstrong and Read Reference Armstrong and Read2000; Bertram Reference Bertram2004; Reference Bertram2015; Bertram and Poirine Reference Bertram, Poirine and Baldacchino2018). Once independent, both observable and unobservable factors likely influenced the size and post-Cold War development of these states.

To help mitigate these causal identification concerns, we—like others (Gerring and Veenendaal Reference Gerring and Veenendaal2020; Jugl Reference Jugl2019; Rose Reference Rose2006)—use the size and quality of states’ arable land as instrumental variables (IV) for their early independence size (appendix section 6). Agricultural size and suitability violate the exclusion restriction necessary for an IV analysis.Footnote 12 We thus treat the IV analysis as a robustness check. The negative coefficient estimate of early independence size in our IV analysis provides additional, albeit partial, evidence that states born with smaller populations after World War II have had higher levels of post-Cold War development (appendix table 23).

The preceding analysis also does not disclose the mechanisms connecting early independence size, Cold War EL, and post-Cold War development. The next section illustrates these mechanisms with a most similar comparative analysis of Oman and South Yemen (PDRY). It delineates how Oman and South Yemen’s contrasting population levels at early independence engendered diverging levels of Cold War EL. The most similar comparison then exposes how this Cold War divergence in public sector and trade policies contributed to the vast gulf in development between these neighboring states today.

Early Independence Size and Post-Cold War Development in Oman and South Yemen

When Oman’s ruler Sultan Qaboos bin Said Al Said usurped his father and came to power in a British-backed coup in 1970, he inherited “a territory without a state” (Valeri Reference Valeri2009, 71). His regime was fighting its second separatist insurrection since independence two decades earlier. And though commercial quantities of oil had been discovered six years earlier and constituted 95% of state revenue (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 286), Oman was one of the poorest countries in the Arabian Peninsula. Qaboos ruled a territory with an infant mortality rate of 75%, three primary schools, and a 5% literacy rate (274–75).

Many of Qaboos’s challenges mirrored those of the Marxist National Liberation Front (NLF) in the neighboring PDRY. The NLF came to power shortly after independence in 1967 through guerrilla warfare. Like Qaboos, it ruled a newly independent state with British-created borders that grouped a mix of rural sultanates with a more populous port city. The two former British colonies had similar geographies. They covered roughly 300,000 square kilometers of desert, arid plains, and mountainous terrain. Like Qaboos at the time, the NLF—soon to be called the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP)—governed while fighting a foreign-backed insurgency.Footnote 13 Though the YSP was a party and Qaboos a sultan, the two regimes were autocracies propped up by foreign patrons.Footnote 14 South Yemen was also destitute. Less than a fifth of its population was literate (Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 86). Almost four out of 10 South Yemeni children died before turning five in 1960, a rate identical to Oman’s at the time (UNDP 1990, 96).

A half-century later, Oman and South Yemen stand at opposite ends of the development spectrum. Oman ascended from being a country with “medium levels of human development” (UNDP 1990) in 1990 to one with “very high levels of human development” almost three decades later (UNDP 2019). The country’s GDP per capita has tripled and life expectancy lengthened by seven years during the post-Cold War era (World Bank 2020). South Yemen, in contrast, underwent state and economic collapse. Economic crisis and fear of invasion pushed the YSP to unite with the northern Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union. Since then, the people of South Yemen have endured two civil wars, famine, and the largest cholera outbreak in recorded history (Cappelaere and Al Mandhari Reference Cappelaere and Al Mandhari2019).

While many factors widened Oman’s and South Yemen’s post-Cold War development disparities, size in the early years of independence is an important driver of this divergence. Oman had a population of roughly eight hundred thousand in 1970 (Maddison Project et al. 2019). The PDRY’s population was twice as large (World Bank 1982, 22). Technology and geography explain this difference. Premodern irrigation techniques cultivated a substantial agricultural community in the western part of South Yemen (Dresch Reference Dresch2000, 121; Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 3). South Yemen also had Aden, the Arabian Peninsula’s best natural port (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 154) and the world’s second busiest in 1958 after New York (Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 77). A quarter of a million residents lived in Aden in 1967 (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 156), more than 10 times larger than Oman’s capital port city of Muscat (Valeri Reference Valeri2009, 81).

Early Independence Size and Cold War Embedded Liberalism (1976–91)

South Yemen’s larger early independence size helped to dissuade its early independence leaders from adopting EL. Most YSP leaders did not see the country’s size as an impediment to their efforts to transform South Yemen from a trade-oriented service economy into a primarily industrial and agricultural one (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 249; Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 80–81). In its first party congress after coming to power, the YSP emphasized the importance of the “masses” of workers and peasants in powering South Yemen’s development (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 232; Rabi Reference Rabi2014, 84). The PDRY’s constitution credits the “toiling masses” for the revolution’s success (PDRY 1978, Preamble) and calls “the people’s labor” the source for the country’s “development and growth” (Article 21). The YSP in fact confronted a surplus of unemployed labor in its early years of rule (Lackner Reference Lackner1985, 153). As a result, the YSP’s initial development plans prioritized and protected labor-intensive industries like textiles to tame unemployment.

Contra EL, the YSP shunned international trade (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 251). YSP policy makers thought their country’s domestic market was large enough to flourish on its own. “Self-reliance,” in the words of the country’s foreign minister at the time, was the first principle of South Yemeni foreign policy (Stork Reference Stork1973, 24). The YSP abolished Aden’s free-port status in 1970 (Halliday Reference Halliday1979, 5). It also restricted foreign capital and labor (PDRY 1978, Article 20). The YSP nationalized foreign-owned banks (Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 81) and insurance companies (Brehony Reference Brehony2011, 65), and required three-quarters of firms’ employees and half of senior staff to be South Yemeni (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 252).

The YSP invested heavily in industry and agriculture to replace imports. These two sectors consumed half of government expenditures in the YSP’s first and second five-year plans (Halliday Reference Halliday1979, 5; World Bank 1982; 1984). The YSP nationalized industry (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 250–52; Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 81) and established cooperatives to manage larger farms and fisheries (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 244; Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 83–85). State-owned enterprises (SOEs) produced tradable goods like textiles, flour, dairy, and tomato paste (Stookey Reference Stookey1982, 81). By 1984, SOEs and public–private partnerships directed South Yemen’s handful of large firms (World Bank 1984, vi).Footnote 15

The YSP did employ a relatively large public sector. Public sector employment represented a quarter of the 1988 labor force (Carapico Reference Carapico1998, 45)—a rate higher than most newly independent states, but lower than Oman’s. The YSP’s large public sector was nevertheless chronically understaffed (Lackner Reference Lackner1985, 167). Higher private sector wages at home and abroad depleted the bureaucracy. South Yemen’s construction industry, for example, paid up to seven times higher than low-skilled public sector employment (167).

In contrast to his peers in South Yemen, Oman’s young sultan embraced EL. Demography facilitated this choice. Oman at early independence lacked the manpower to produce most goods. Industry was nonexistent (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 292). Unlike in South Yemen, the Omani regime never rushed to prop up or protect labor-intensive industries to mitigate unemployment. One of Qaboos’s first royal decrees declared that “free and unrestricted competition”—not the toiling masses—would power the country’s development (Hill Reference Hill1983, 525). Free trade was one of eight major long-term development objectives in Qaboos’s 1976 First Development Plan (Alshanfari Reference Alshanfari1989, 37). The Qaboos regime then actively sought trade agreements and greater economic integration with its neighbors (O’Reilly Reference O’Reilly1998, 71, 76; Owen Reference Owen1993, 4).

Unlike the YSP, the Qaboos regime welcomed foreign investment (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 289). Lacking domestic capital and labor, Qaboos hired foreign firms to build Oman’s infrastructure (287). The Qaboos regime did not redistribute land or expropriate or nationalize foreign industries and banks. On the contrary, Qaboos invited foreign banks to Oman. The 1974 law founding Oman’s Central Bank had provisions facilitating the entrance of foreign-owned banks into Oman (Hanieh Reference Hanieh2011, 80–81). Indeed, the British Bank of the Middle East managed 85% of all banking in the sultanate (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 293).

Though open to foreign goods and capital, the Qaboos regime still required foreign companies to work with Omani intermediaries (Hill Reference Hill1983, 517; Valeri Reference Valeri2009, 102). This requirement enriched a coterie of elite merchant families that had the capital to establish intermediary companies and profit from international trade (Hanieh Reference Hanieh2011, 75; Valeri Reference Valeri, Hertog, Luciani and Valeri2013b; Reference Valeri, Hudson and Kirk2014, 57). This created a powerful local constituency to defend the sultanate’s open trade policies.

The Qaboos regime paired open markets with a large public sector. Demography once again eased this choice. The country’s small population at the time of independence ensured that the public sector would consume a relatively large share of the local labor force. Qaboos needed to work with his country’s scarce labor force to build his state.

This required forgiving past rivalries. Once in power, Qaboos quickly passed an amnesty and invited leaders and members of rebellious regions into government (Valeri Reference Valeri2009, 153; Reference Valeri and Wippel2013a, 269). Qaboos’s clemency was pragmatic. Incorporating disparate groups within the bureaucracy helped his regime to govern its thinly populated state.

Qaboos then expanded public sector employment dramatically. Government administration—which includes spending on defense and public sector employment—constituted almost a third of government expenditures in Qaboos’s first (Alshanfari Reference Alshanfari1989, 41) and second (42) five-year development plans. Industry and agriculture received less than 6% of government investment. In 1971, 5,500 Omanis worked in public administration and the military—roughly 5.5% of the country’s total labor force (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 292). Four years later, the number of Omanis employed in the armed forces and civil services expanded to 24,000—representing close to half of the country’s nonrural employment (World Bank 1977, table 1.2). Oman’s public sector grew 7% per year in the 1980s, representing 35% of the Omani labor force in the early 1990s (World Bank 1994). This was roughly 10 percentage points higher than South Yemen’s rate of public sector employment at the time (Carapico Reference Carapico1998, 45).

Two factors upheld Oman’s large public sector during the Cold War. The first was oil. The sultanate’s oil revenue quintupled between 1975 and 1985 (Alshanfari Reference Alshanfari1989, 30) and would carry 90% of government revenue. The Qaboos regime had the means to expand its public sector.

Second, the Qaboos regime welcomed foreign labor. A slight exporter of labor in the 1950s and 1960s, Oman had positive net migrant flows in the 1970s and 1980s (Abdul Nasir and Tahir Reference Abdul Nasir and Tahir2011, 181). Foreign labor permits almost doubled from 130,000 to 248,000 between 1980 and 1986 (Technical Secretariat of the Development Council 1988, 125, table 68). Foreign labor helped the Omani private sector to ease labor-force constraints and keep labor costs low as Omanis gravitated toward the security and higher wages of public sector jobs (Swailes and Al Fahdi Reference Swailes and Al Fahdi2011, 684). Omanis’ stronger preferences for public sector jobs and the private sector’s cheap access to foreign labor sustained Oman’s large public sector over time as the country’s population almost quadrupled to two million between 1975 and 1990.

Oman’s large public sector lubricated the country’s open trade policies. Unlike in South Yemen, Oman’s public sector employees did not produce tradable goods. The Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health were Oman’s largest civil service employers (Valeri Reference Valeri2009, 88). Cheap imports did not threaten their livelihoods. This made it politically easier for the Qaboos regime to open Oman’s markets to foreign goods and capital.

Economic integration incentivized the Omani regime to begin building inclusive economic institutions in the 1980s (Hill Reference Hill1983). The Qaboos regime passed an investment law that safeguarded foreign firms from nationalization to alleviate foreign firms’ fears of expropriation (Jones and Ridout Reference Jones and Ridout2015, 224). After local merchants denounced the influx of fake goods into the market (Hill Reference Hill1983, 520), the Qaboos regime issued the Commercial Law of 1987 to defend trademark and intellectual property. These laws foreshadowed numerous international trade and intellectual property rights agreements adopted in the 2000s (Sangar Reference Sangar2010). Less successfully, the Qaboos regime tried to subdue corruption by banning government officials and their relatives from owning shares in companies bidding for government contracts (Valeri Reference Valeri2009, 107).

Diverging Post-Cold War Development (1992–2020)

The Qaboos and YSP regimes’ contrasting Cold War trade and public sector policies helped to wedge the two states’ diverging post-Cold War development. Oman’s Cold War trade, property, and investment laws scaffolded the country’s post-Cold War prosperity as globalization accelerated in the 2000s. The World Bank (2019) rated Oman as the fifth best place to do business in the Middle East and North Africa region, and 68th globally in 2019. Oman’s corruption perception indicator ranked 56th that year, better than the world average (Transparency International 2019). Given oil abundance’s strain on the ease of doing business (Mazaheri Reference Mazaheri2016), Oman’s economic institutions are remarkably inclusive.

Meanwhile, Oman’s large public sector helped to entrench political stability. As in South Yemen, the Omani regime ruled an ethnically, religiously, and socioeconomically diverse territory. Public sector jobs, however, weakened citizens’ tribal and parochial loyalties in favor of a more inclusive Omani state (Valeri Reference Valeri2009, 88). Oman’s large bureaucracy was not efficacious. A World Bank (1994) report denounced “substantial overstaffing” and noted that “a substantial fraction” of Omani civil servants were “underqualified for the positions they hold.” But this bureaucracy inculcated political stability. Qaboos had ruled Oman for 50 years when he died in 2020. The peaceful transition of power to Qaboos’s cousin, Haitham bin Tariq, is the greatest testament to the Qaboos regime’s political stability. This stability contributed to Oman’s post-Cold War prosperity.

Political instability, in contrast, rocked South Yemen. The PDRY had five presidents between 1967 and 1986, three of whom left power violently (Rabi Reference Rabi2014, 106). Each presidential turnover sprang from ideological divisions among the YSP’s centrist and leftist flanks. A feud within the ruling party in 1986 led to intraparty clashes, causing thousands of deaths (Nagi Reference Nagi2022). Regional rivalries tainted these ideological divides. The YSP’s urban constituents gravitated toward Marxist ideologies and preferred industrialization. Its rural constituents favored Maoist policies and agricultural development. Political turnover and elite factions balkanized ministries and military units along regional and family lines (Kostiner Reference Kostiner1990, 27; Rabi Reference Rabi2014, 85). Thus while Oman’s large public sector helped to soothe preindependence rivalries and weld a collective Omani identity loyal to the Qaboos regime, the communal calculus guiding the YSP’s hiring and purging of public sector and military officials calcified subnational and intraparty rivalries—to the detriment of South Yemen’s post-Cold War development.

Indeed, YSP divisions hastened the PDRY’s unification with, and subsequent occupation by, the northern YAR shortly after the Cold War. The PDRY lost its chief foreign donor and lender in the Soviet Union when the Cold War ended (World Bank 1984, iii, 12). The discovery of oil on the border between the PDRY and YAR, far from being seen as a cure for the country’s ills, amplified YSP leaders’ fears of a northern invasion (Wedeen Reference Wedeen2008, 54). They opted for unification with the north in 1990 instead. This accord did not last long. Leaders from the north and south contested the unification agreement’s power sharing arrangements and fought over how to manage the country’s oil reserves (Carapico Reference Carapico1998, 55). When civil war erupted four years later, the YAR crushed the PDRY’s military and occupied Aden, ending South Yemen’s sovereignty (Rabi Reference Rabi2014, 115–35). Divisions among the YSP facilitated the YAR’s invasion, as some YSP factions allied with the YAR (Lackner Reference Lackner2017, 119; Nagi Reference Nagi2022).

South Yemen and its people have suffered immense hardship in the post-Cold War era. The Yemeni government’s privatization of SOEs and firing of PDRY military personnel after the civil war exacerbated unemployment. Many industries left Aden for the north (Dahlgren Reference Dahlgren2019; Lackner Reference Lackner2017, 175). What industry remained stagnated or capitulated from greater international competition (250). Youth unemployment ballooned to 50% (Augustin Reference Augustin2021, 120). These grievances fueled a southern separatist movement in 2007. Retired officers, heads of civil society, and unemployed youth led this movement (Dahlgren Reference Dahlgren2019), which the Yemeni government brutally crushed (Lackner Reference Lackner2017, 177–82). The separatist movement reemerged and militarized in the wake of the Arab Spring and Yemen’s descent into civil war and humanitarian catastrophe.

Stepping back, three factors outside early independence size might also explain Oman’s and South Yemen’s developmental divergence. The first is oil. Though scholars disagree whether oil is a blessing or a curse (Ross Reference Ross2015), Oman’s oil reserves were integral to its developmental success. But oil can only explain part of its success. Oil wealth does not predetermine open markets and large public sectors. Oil-abundant Iran and Venezuela have not embraced open trade policies. Low population levels in Oman, however, propelled Qaboos to adopt EL. By encouraging political stability and inclusive economic institutions, Cold War EL helped the sultanate to capitalize on its oil wealth.

It is also unclear whether South Yemen would have prospered if it had Oman’s oil wealth. Corruption, mismanagement, and insecurity incapacitated Yemen’s oil industry (Lackner Reference Lackner2017, 228–29), which at times represented up to 80% of government revenue in the 2000s (Augustin Reference Augustin2021, 125). Greater oil revenue may have amplified tensions within the YSP. Indeed, disputes over how to manage Yemen’s oil resources were one cause of the 1994 civil war (Carapico Reference Carapico1998, 55). These fights may have further factionalized an already divided YSP.

Regime type is a second alternative explanation. A party ruled South Yemen, a sultan governed Oman. Monarchies, which are like sultanates, survive longer on average than authoritarian party states (Hadenius and Teorell Reference Hadenius and Teorell2007, 150), though this difference is slight (eight years). State size, however, might account for this difference. Most ruling monarchies today govern low-population states, which tend to be more politically stable.

Regime ideology is another alternative explanation for Oman’s and South Yemen’s development divergence. If Qaboos had been a Marxist, Oman would have fared no better than its western neighbor. Though possible, Oman’s smaller population would have made Marxist policies incredibly hard to implement. Unlike the YSP, the Qaboos regime in its early years of rule did not have a surplus of labor to establish new industries. Oman’s small domestic market would have also made protectionist policies especially costly for consumers. Meanwhile, the labor needed to govern Oman would have still consumed a relatively large share of the local labor force. Marxism might have slowed but it is unlikely to have stopped Oman’s tilt toward EL.

Finally, the drastic differences between Qaboos and his father—a recluse who once banned eyeglasses (Halliday Reference Halliday1974, 275)—underscore the importance of leaders in helming newly independent states’ long-term development. Qaboos’s father resisted investing his country’s oil wealth in education and health for fear it would lead to rebellion (276). The stark contrast between Qaboos and his father reiterate that early independence size does not predetermine development. While population scarcity eased the Qaboos regime’s choice of EL, Qaboos’s leadership, competency, and charisma allowed the sultanate to successfully execute and benefit from these policies.

Conclusion

States born with smaller populations after World War II were more likely to implement EL during the Cold War and subsequently prosper in the post-Cold War era. We demonstrate these patterns with a cross-sectional statistical analysis. We then expose the mechanisms linking early independence size and post-Cold War prosperity with a case study of Oman and South Yemen. Together, these analyses expose complementary pathways in which early independence size can promote post-Cold War development. The mediation analysis highlights the importance of open trade policies in building inclusive economic institutions and post-Cold War development. The case study, however, emphasizes how smaller states’ larger public sectors can help to lay a foundation of political stability on which states can prosper.

Our analysis points to many future avenues of research. One next step is to explore why and how some historically smaller states have eased their population constraints (Oman) while others have not (Cape Verde). If embeddedness and labor-force expansion require exclusive welfare policies and citizenship regimes (Goodman and Pepinsky Reference Goodman and Pepinsky2021), perhaps low-population states with less open political systems are more likely to become “big.” Domestic politics undoubtedly structure whether and how small states grow demographically and economically.

Indeed, who participates in domestic politics shapes states’ policies and institutions. Most measures of state size ignore this difference by assessing state size in terms of residents, not citizens. Though both citizens and migrants are residents, citizens typically exert greater political influence. A state’s citizenry may be a more politically consequential marker of population size than its residents.

Another strand of future research can clarify differences in development among small and large newly independent states. Size is not destiny. Some states born with large populations have prospered in the post-Cold War era (South Korea); some small newly independent states have not (Comoros). Investigating “off-the-line” cases (Lieberman Reference Lieberman2005) can expose underlying conditions that buttress the generally negative association between early independence size and post-Cold War prosperity (figure 1 in the online appendix). We suspect that leadership helps to steer diverging developmental outcomes among small newly independent states. While demography facilitated EL, newly independent states’ founding leaders ultimate chose whether their state would adopt these policies. Former colonizers also influenced newly independent states’ Cold War trade and public sector policies. Future work can explore the institutional and international factors that forged these early independence choices.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592724002640.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the editors Ana Arjona and Wendy Pearlman and the four anonymous reviewers for their guidance, patience, and support. We also thank Faisal Ahmed, Basil Bastaki, John Gerring, Marlene Jugl, Matt Khoo, Soo Yeon Kim, Bob Kubinec, Martin Mattson, Nimah Mazaheri, Jong Hee Park, Alison Post, Rachel Riedl, Xu Jian, and participants at the 2022 Midwest Political Science Association annual conference, the 2023 Asian PolMeth conference, the 2023 American Political Science Association conference, and the Singapore Political Economy Seminar for their excellent feedback. We are especially indebted to Nicholas Kuipers for his advice on revising the manuscript. Jonathan Fu was a tremendous help in the initial phases of the project. Ian Chai, Norah Chan, and Siddharth Roy were superb research assistants. We thank Yale-NUS College for its generous financial support. All faults are our own.

Data availability statement

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/8U47M6