INTRODUCTION

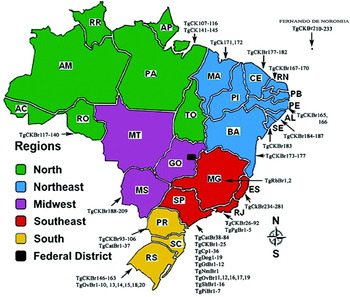

Brazil is a large country with a human population of more than 190 million, and a booming economy. It is divided in to 26 states and a Federal district (Fig. 1). Most of the population is concentrated in the south with 41% of the population in the state of São Paulo. We have used abbreviated names of states in the following review; full names with human population are given in Fig. 1. We review the current status of Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans and animals. We have attempted to incorporate all published reports available to us on natural T. gondii infections, especially papers in Portuguese. We consulted original papers because in many instances information online was not correct. Detailed historical, serological, parasitological, clinical and genetic information on T. gondii infections in humans and other animals are summarized in Tables throughout the review.

Fig. 1. Map of Brazil with 5 regions and distribution of human population, and sources of Toxoplasma gondii isolates genotyped. Figures in parenthesis are millions of people and % of the total population. State abbreviation—(population million, %): AC – Acre (0·7, 0·38%), AL – Alagoas (3·1, 1·64%), AM – Amazonas (3·4, 1·83%), AP – Amapá (0·6, 0·35%), BA – Bahia (14·0, 7·35%), CE – Ceará (8·4, 4·43%), DF – Distrito Federal (2·5,1·35%), ES – Espírito Santo (3·5, 1·84%), GO – Goiás (6·0, 3·15%), MA – Maranhão (6·5, 3·45%) MS – Mato Grosso do Sul (2·4, 1·28%) MG – Minas Gerais (19·5, 10·27%), MT – Mato Grosso (3·0, 1·59%) PA – Pará (7·5, 3·97%), PB – Paraíba (3·7, 1·97%), PE – Pernambuco (8·7, 4·61%), PI – Piauí (3·1, 1·63%), PR – Paraná (10·4, 5·48%), RN – Rio Grande do Norte (3·2, 1·66%), RJ – Rio de Janeiro (15·9, 8·38%), RO – Rondônia (1·5, 0·82%), RR – Roraima (0·4, 0·24%), RS – Rio Grande do Sul (10·6, 5·60%), SC – Santa Catarina (6·2, 3·28%) SE – Sergipe (2·0, 1·08%) SP – São Paulo (41·2, 21·63%) TO – Tocantins (1·3, 0·73%).

HISTORY

The parasite now called Toxoplasma gondii and the disease it causes called toxoplasmosis were first noted in 1908 in the rodent Ctenodactylus gundi in Tunisia by Nicolle and Mancaeux (Reference Nicolle and Manceaux1908, Reference Nicolle and Manceaux1909), and in the domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) in Brazil by Splendore (Reference Splendore1908). Dr Alfonso Splendore was a physician immigrant from Italy (Splendore, Reference Splendore1908, translated in 2009 into English). It is a remarkable coincidence that this disease was first recognized in laboratory animals and was first thought to be Leishmania by both groups of investigators. The parasite was named Toxoplasma gondii by Nicolle and Manceaux (Reference Nicolle and Manceaux1909).

Congenital toxoplasmosis was probably first recognized in Brazil in 1927 by Carlos Bastos Magarinos Torres (Reference Torres1927) who performed an autopsy on a 2-day-old girl in Rio de Janeiro. The child was born at term and had generalized muscular twitching and convulsions soon after birth. Predominant lesions were meningo-encephalomyelitis, myocarditis and myositis. Numerous protozoal bodies were found in histological sections of the central nervous system, heart, skeletal muscles, and subcutaneous tissue. Torres (Reference Torres1927) named the parasite Encephalitozoon chagasi. In retrospect the lesions and the morphology of the parasite are indicative of toxoplasmosis.

The first proven case of congenital toxoplasmosis was described by Drs Wolf, Cowen, and Page (Reference Wolf, Cowen and Paige1939) in a Caesarian-derived infant on 23 May 1938 at the Babies Hospital, New York, USA. Guimarães (Reference Guimarães1943) extensively reviewed worldwide reports of toxoplasmosis in humans and first described confirmed congenital toxoplasmosis in a Brazilian 14-month-old girl. She was born with hydrocephalus, suffered convulsions and ocular tremor, and subsequently radiographical examination revealed intracerebral calcification. The diagnosis was confirmed by bioassay in mice and guinea pigs inoculated with cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) from the child. The strain of T. gondii from the child was virulent for dogs, pigeons, mice, rabbits, and guinea pigs. Guimarães (Reference Guimarães1943) also reported acute fatal toxoplasmosis in an 18-year-old Brazilian male from rural Rio de Janeiro. This man had fever, mononucleosis, headache, paresis of lower limbs, dysphasia, dyspnea, and died after an illness of 37 days. A post-mortem examination revealed pericarditis, hepatitis, splenitis, nephritis, and bronchopneumonia. Toxoplasma gondii stages were seen in sections of several organs including encephalitic lesions in the brain. The histological picture was typical of recently acquired acute toxoplasmosis. Alencar and Schäffer (Reference Alencar and Schäffer1971) histologically confirmed fatal congenital toxoplasmosis in 2 children in Rio de Janeiro. A few landmarks of the history of toxoplasmosis in Brazil are given in Table 1 and also reported by de Souza et al. (Reference de Souza and Casella2009), Melamed (Reference Melamed2009) and Fialho et al. (Reference Fialho, Teixeira and de Araujo2009).

Table 1. Historical landmarks of Toxoplasma gondii and toxoplasmosis in Brazil

TOXOPLASMOSIS IN HUMANS

Prevalence of T. gondii infection

The discovery of a novel and specific serological test, the dye test, by Sabin and Feldman (Reference Sabin and Feldman1948) made it possible to conduct population-based surveys for this parasite. Different serological techniques used in Brazilian studies and their abbreviation are listed in Table S1 (online version only). In many instances commercial test kits were used and the manufacturers have changed over time. Cut-off values for serological tests are listed wherever the authors provided the information. Details of in-house tests are not listed in Table S1 or any subsequent tables.

Reports of serological surveys in Brazilians are summarized in Table 2. Among these reports, the study based on military recruits is most noteworthy because results could be compared with prevalence data in the USA (Feldman, Reference Feldman1965; Lamb and Feldman, Reference Lamb and Feldman1968; Walls and Kagan, Reference Walls and Kagan1967; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Kagan and Turner1967). In this survey, sera were collected from young adult males (18–21 years old) in Brazil and the USA and sera from both countries were deposited at a World Health Organization Center in the USA where they were tested in an identical manner in 2 US laboratories (Feldman's lab [co-inventor of the dye test], and the Centers for Disease Control [CDC], Atlanta, Georgia). Results indicated that the seroprevalence of T. gondii was (and still is, Dubey, Reference Dubey2010a) 4 times (56% versus 13%) higher in Brazil than in the USA, and the magnitude of antibody titres were also higher (27% versus 1% at a titre of 1:256) in Brazil than in the USA. Results based on the dye test are shown in Table S2 (online version only). Similar results were obtained with the IHA test conducted at CDC on sera from both countries (Walls and Kagan, Reference Walls and Kagan1967; Walls et al. Reference Walls, Kagan and Turner1967); seroprevalence at IHA titre of 1:64 was 56·4% (Brazil) versus 24·4% (USA). Such a direct comparison of seroprevalence of T. gondii among countries has never been made elsewhere.

Table 2. Serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in the general population in Brazil

Serological prevalence data in children are summarized in Table 3. Up to 32% of 0–5 year olds, 19·5–59% of 6–10 year olds, and 28·4–84·5% of 11–15 year old children in Brazil were seropositive (Table 3). Limited data indicate that in certain areas approximately 50% of pre-teenage children have been exposed to the parasite (Table 3). Among these reports, Jamra and Guimarães (Reference Jamra and Guimarães1981) provided seroprevalence data in 450 children, 0–15 years old, from a health centre in São Paulo. The percentages of seropositives were: 53·3% in children <1 year old, 0% in 2–3 year olds, 13·3% in 3–4 year olds, and 10% in 4–5 year olds, reaching to 43·3% in 15 year olds (Table 3). Seropositivity in infants <1 year old was attributed to antibodies transferred from their infected mother. Toxoplasma gondii antibodies were found in 4 of 30 (13·3%) 3–4 year old children but not in 2–3 year old children. In isolated Amerindians of Mato Grosso state, 6 of 12 children, 6–9 years old, were seropositive (Amendoeira et al. Reference Amendoeira, Sobral, Teva, de Lima and Klein2003).

Table 3. Serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in children in Brazil

a 0 to 9-year-old.

b 27·2% in 756 7-year-olds, 41·7% in 115 8 to 9-year olds, 31·1% in 86 10-year-olds.

c 4 to 11-year-old.

d Data in Table supplied by authors. Published data were: 13·7% of 459 in 6-year-olds, 15·5% in 419 6 to 7-year-olds, and 25·1% in 339 8 to11-year-olds.

e Children were 1–9 years old.

f Cut-off: average absorbance reading obtained with 15 negative control sera plus 3 standard deviations.

g 11 to 20-year-old.

h Personal communication to E. Lago.

i 12 to14-year-old.

Very high (36–92%) seroprevalences were found in pregnant women (Table 4). These data indicate that seroprevalence of T. gondii in children and in pregnant women in Brazil is one of the highest worldwide (Dubey and Beattie, Reference Dubey and Beattie1988; Tenter et al. Reference Tenter, Heckeroth and Weiss2000; Dubey, Reference Dubey2010a).

Viable T. gondii was isolated from the tonsils of asymptomatic humans (Jamra et al. Reference Jamra, Deane, Mion and Guimarães1971; Amendoeira and Coutinho, Reference Amendoeira and Coutinho1982).

Table 4. Serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in pregnant/delivering, or child-bearing aged women in Brazil

a Antenatal clinics.

b NS: Not stated, as recommended by the manufacturer.

c Personal communication to E.Lago.

Congenital toxoplasmosis in children

Based on one report, ocular toxoplasmosis in congenitally infected children in Brazil was more severe than in children in Europe (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Freeman, Lago, Bahia-Oliveira, Tan, Wallon, Buffolano, Stanford and Petersen2008). This conclusion was based on comparison of ocular lesions in 30 children in Brazil with 281 children in Europe using similar methodology. In these 30 Brazilian children, the lesions in the eyes were more extensive than in the European children and more likely to involve the area of the retina affecting the central vision, in spite of the fact that most of the Brazilian children had been treated for toxoplasmosis for 12 months (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Freeman, Lago, Bahia-Oliveira, Tan, Wallon, Buffolano, Stanford and Petersen2008). This study concluded that the Brazilian children had a 5 times higher risk of severe toxoplasmosis than children in Europe. In another report, the risk of intracranial lesions detected by computed tomography (CT) scan was much higher in Brazilian children than in children in Europe (The SYROCOT, 2007). Some of these differences are thought to be related to the genetic makeup of the T. gondii strains in humans in Brazil but direct evidence for this hypothesis is lacking and difficult to obtain. However, this subject is intriguing. Perhaps further studies using a larger sample size as well as basic studies concerning pathogenesis of infections caused by different isolates may lead to further insight concerning the observations above. In this respect, we summarize published information on prevalence, and severity of congenital toxoplasmosis in Brazil.

An estimate of incidence or prevalence, and clinically manifest neonatal toxoplasmosis may be obtained from reports of observed cases, calculations based on the infection rate during pregnancy, and screening of children at birth. In the present review, we have listed all surveys in pregnant women and serological methods used. There is only limited information on the validity of commercial kits used, especially for the detection of IgM worldwide (Wilson et al. Reference Wilson, Remington, Clavet, Varney, Press, Ware, Herman, Shively, Simms, Hansen, Gaffey, Nutter, Langone, McCracken and Staples1997; Calderaro et al. Reference Calderaro, Picerno, Peruzzi, Gorrini, Chezzi and Dettori2008; Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011); some of these kits were also used for testing sera of Brazilian women and children. However, for the past 2 decades, reagents and manufacturers of the commercial products have changed. Additionally, the performance of kits used for diagnosis of infections with Brazilian strains of the parasite has not been studied, and could be very different from results in other countries in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value. The accuracy of some of the commercial diagnostic kits, especially for the detection of IgM antibodies, is unsatisfactory (Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011). There is no national reference laboratory for T. gondii testing in Brazil.

Congenital toxoplasmosis detected by prenatal screening

There are very few reports of prenatal screening in Brazil. In a study of 2513 consecutive peri-parturient women at a hospital in Porto Alegre, RS, congenital toxoplasmosis was diagnosed in 4 infants (Lago et al. Reference Lago, de Carvalho, Jungblut, da Silva and Fiori2009b). Of these women, 1667 (67·3%), were already seropositive before pregnancy and thus unlikely to deliver congenitally infected children (Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011). In the 810 susceptible women, 3 infected infants were identified through testing of the mother at delivery, and 1 fetus was found infected during the second trimester of gestation; this child had hydrocephalus on fetal ultrasound and hepato-splenomegaly, microphthalmia, and retinochoroiditis at birth. This child had severe mental retardation at 5 years of age. The second child was asymptomatic at birth but had hepatomegaly when 3 weeks old. The other 2 also had retinochoroiditis. Fetal toxoplasmosis was diagnosed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on amionic fluid in 12 of 72 women with acute toxoplasmosis who were followed during pregnancy at a hospital in Belo Horizonte (de Faria Couto and Leite, Reference de Faria Couto and Leite2004). Ultrasound examination was performed fortnightly and children were followed clinically for up to 1 year. Eight fetuses had signs of toxoplasmosis with bilateral ventricular enlargements, some accompanied by lesions in other organs; of these, 4 fetuses were stillborn, and 3 had retinochoroiditis with neurological abnormalities. The 4 surviving fetuses without ventricular lesions remained asymptomatic as infants for the first year of life (de Faria Couto and Leite, Reference de Faria Couto and Leite2004) indicating the prognostic value of fetal ultrasound examination. In another study, severe clinical toxoplasmosis with hydrocephalus was found in an infant born to 1 of 75 women who acquired toxoplasmosis during pregnancy (Higa et al. Reference Higa, Araújo, Tsuneto, Castilho-Pelloso, Garcia, Santana and Falavigna-Guilherme2010).

Varella et al. (Reference Varella, Canti, Santos, Coppini, Argondizzo, Tonin and Wagner2009) recorded acute toxoplasmosis in 41 per 10 000 pregnancies among 44 112 pregnant women submitted to prenatal screening for toxoplasmosis in Porto Alegre, RS. Acute toxoplasmosis was identified by the criteria recommended by the European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis (Lebech et al. Reference Lebech, Joynson, Seitz, Thulliez, Gilbert, Dutton, Ovlisen and Petersen1996) plus IgG avidity test and PCR testing in amniotic fluid. The rates of acute toxoplasmosis decreased from 66 per 10 000 pregnancies in 2001 to 21 per 10 000 pregnancies in 2005. Twenty-five cases of congenital toxoplasmosis were diagnosed at birth, and 12 additional cases were diagnosed at follow-up during the first year of life, resulting in a prevalence of congenital toxoplasmosis of 9 per 10 000 live births (Varella et al. Reference Varella, Canti, Santos, Coppini, Argondizzo, Tonin and Wagner2009).

Congenital toxoplasmosis detected by post-natal filter paper screening

Table 5 summarizes congenital toxoplasmosis identified through screening of children at birth or their mothers. Most of these reports were based on determination of IgM antibodies on blood collected on filter papers. Based on data in Table 5 the prevalence of congenital toxoplasmosis was 5–23 cases per 10 000 live births. In the largest sampling involving 800 164 infants from 27 states in Brazil (Neto et al. Reference Neto, Amorim and Lago2010), 496 infected (average 1 per 1613, range 0–20 per 10 000 infants) were identified. The variation in rate of congenital toxoplasmosis in various samples maybe partly related to the seroprevalence of T. gondii in pregnant women; in some regions >90% of women of child-bearing age are seropositive before pregnancy and thus not likely to deliver a T. gondii-infected baby. However, in most regions of Brazil the seroprevalence of T. gondii in pregnant women is between 50 and 80% and, although the proportion of susceptible pregnant women is still small, these women are a high risk for infection because they live in a highly contaminated environment.

Table 5. Prevalence of congenital toxoplasmosis in Brazil

a Filter paper, universal neonatal screening.

b Venous blood, screening survey of mothers in antenatal clinics.

c Cord blood, screening survey in a delivery room.

d Optical densities ⩾80% of the control cut-off.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and congenital toxoplasmosis

Concurrent HIV infection of the mother may alter the course of toxoplasmosis during pregnancy. De Azevedo et al. (Reference de Azevedo, Setúbal, Lopes, Camacho and de Oliveira2010a) and Fernandes et al. (Reference Fernandes, Vasconcellos, de Araújo and Medina-Acosta2009) reported congenital transmission in 4 infants born to HIV- infected women in Brazil but indicated that this event is rare. Seroprevalences in women with or without HIV are generally similar (Neto and Meira, Reference Neto and Meira2004). Seroprevalence of T. gondii in HIV-positive women (72% of 168) was only slightly higher than in women without HIV (67% of 1624) and no previously T. gondii-infected HIV-positive women delivered a T. gondii-infected child as documented by Lago et al. (Reference Lago, Conrado, Piccoli, Carvalho and Bender2009a). However, T. gondii has been transmitted from HIV-infected women with chronic T. gondii infection to their children (de Azevedo et al. Reference de Azevedo, Setúbal, Lopes, Camacho and de Oliveira2010a). Recently, Delicio et al. (Reference Delicio, Milanez, Amaral, Morais, Lajos, Pinto e Silva and Cecatti2011) reported congenital transmission of HIV and other concurrent infections in 15 (13 women were not on highly active antiretroviral therapy [HAART]) of 452 HIV-infected women; T. gondii infection was found in 6 children. On the face of it this appears to be a high rate of transmission of T. gondii, but methods used for diagnosis were not stated.

Congenital toxoplasmosis from chronically infected women

In immunocompetent women transmission of T. gondii usually occurs when the mother acquires infection during pregnancy. Rarely, congenital transmission has been documented from mothers infected in the months before the pregnancy. Silveira et al. (Reference Silveira, Ferreira, Muccioli, Nussenblatt and Belfort2003) reported congenital toxoplasmosis in a baby whose mother had evidence of past infection before the current pregnancy; she had been diagnosed serologically with ocular toxoplasmosis 20 years previously. She had no known immunocompromise but details of methods used to evaluate immunosuppression were not provided (Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011). Elbez-Rubinstein et al. (Reference Elbez-Rubinstein, Ajzenberg, Dardé, Cohen, Dumètre, Yera, Gondon, Janaud and Thulliez2009) reported a case of severe toxoplasmosis as a result of re-infection during pregnancy, and reviewed 5 previous cases of congenital transmission from chronically infected women. One of the hypotheses for this rare event is re-infection with a highly virulent parasite with atypical T. gondii genotype (Lindsay and Dubey, Reference Lindsay and Dubey2011). In this respect travel to Brazil is a focus of attention (Kodjikian et al. Reference Kodjikian, Hoigne, Adam, Jacquier, Aebi-Ochsner, Aebi and Garweg2004; Anand et al. Reference Anand, Jones, Ricks, Sofarelli and Hale2012) because Brazilian strains of T. gondii are genetically different from those prevalent in Europe and North America (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann, Marcet, Graham, Dahl and Dubey2006). In the case described by Kodjikian et al. (Reference Kodjikian, Hoigne, Adam, Jacquier, Aebi-Ochsner, Aebi and Garweg2004) the mother was a resident of Switzerland for 6 years but born in Brazil and had travelled to Brazil during the fifth month of gestation. Recently, Andrade et al. (Reference Andrade, Vasconcelos-Santos, Carellos, Romanelli, Vitor, Carneiro and Januario2010) described a most unusual ocular toxoplasmosis in a mother and her baby. The baby was born asymptomatic but was found to have bilateral retinochoroiditis and had IgM and IgG antibodies to T. gondii. The mother had clinical retinochorioditis and T. gondii antibodies 10 years before the current pregnancy giving birth to the infected child. During the current pregnancy the mother had clinical retinochorioditis, stable IgG antibodies and no IgM antibodies to T. gondii.

Clinical toxoplasmosis in congenitally infected children

Most congenitally infected children are asymptomatic at birth and some do not manifest symptoms until later in childhood, or even in adult life (McLeod et al. Reference McLeod, Kieffer, Sautter, Hosten and Pelloux2009; Delair et al. Reference Delair, Latkany, Noble, Rabiah, McLeod and Brézin2011; Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011). The most common manifestation of congenital toxoplasmosis is ocular disease, sometimes presenting as retinochoroiditis, cataracts, strabismus or nystagmus, and total blindness. This pattern was observed in studies in Brazil, although most children were not followed past 12 months of age. Depending on how the sample was obtained, some studies are more useful for demonstrating the prevalence of congenital toxoplasmosis. Other studies are case series reported by symptoms, which although not able to determine prevalence, demonstrate the wide range and the possible severity of clinical manifestations (Table 6). The most accurate information with respect to clinical disease during the neonatal period was provided by studies by Vasconcelos-Santos et al. (Reference Vasconcelos-Santos, Azevedo, Campos, Oréfice, Queiroz-Andrade, Carellos, Romanelli, Januário, Resende, Martins, Carneiro, Vitor and Caiaffa2009). Unlike other studies in Brazil, 178 (93·7%) of 190 children were examined ophthalmologically at a median of 56 days of age and all children were born in the state of Minas Gerais. Most (142, 79·8% of 178) infants had some evidence of ocular disease (Table 6). The authors state that some peripheral ocular lesions might have been missed because the children were not sedated during eye examinations. Viable T. gondii was isolated from blood of 27 children and the scientific community is waiting for results of genotyping of these isolates. Hearing was evaluated in 106 of these children (de Resende et al. Reference de Resende, de Andrade, de Azevedo, Perissinoto and Vieira2010). Forty-six children had hearing dysfunction; 13 had conductive hearing loss, 4 had sensorineural hearing loss, and 29 had central hearing dysfunction. Additionally, there was an association between hearing problems and language deficits. The percentage of children with hearing loss in this study is much higher than reported for treated or untreated congenitally infected children in North America or Europe (Olariu et al. Reference Olariu, Remington, McLeod, Alam and Montoya2011; Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011).

Table 6. Clinical toxoplasmosis in congenitally-infected children in Brazil

CT, congenital toxoplasmosis; ICC, intracranial calcification; RC, retinochoroiditis; RS, retinal scar; HS, hepato-splenomegaly; LAD, lymphadenopathy; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ALT, alanine aminotransferase ; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

* 7 eyes presented medial opacities, which prevented fundus examination.

Melamed et al. (Reference Melamed, Dornelles and Eckert2001, Reference Melamed, Eckert, Spadoni, Lago and Uberti2009) examined under sedation the eyes of 44 <1 year-old congenitally infected children. Thirty-one of 44 (70·4%) children had ocular disease and retinochoroiditis was the most common (65·9%) lesion. The retinochoroiditis was bilateral in 22 cases, lesions were active in 8 eyes and had healed in 43 children. This study indicated that, like the study from Minas Gerais, a high proportion of children with ocular disease were observed earlier than studies from other countries (McLeod et al. Reference McLeod, Kieffer, Sautter, Hosten and Pelloux2009; Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011). These findings are contrary to what has been seen in treated children in Europe and North America and might be related to treatment (McLeod et al. Reference McLeod, Boyer, Karrison, Kasza, Swisher, Roizen, Jalbrzikowski, Remington, Heydemann, Noble, Mets, Holfels, Withers, Latkany and Meier2006, Reference McLeod, Kieffer, Sautter, Hosten and Pelloux2009).

Nationwide estimates of congenital toxoplasmosis in Brazil

Data summarized in Table 5 indicate a wide range of 5–23 congenital infections per 10 000 births. Most of the studies were based on selected sampling because there is no national screening of women or children for toxoplasmosis in Brazil. Often the sampling was based on who could afford the testing and under these circumstances there will be under representation of samples from low economic groups. Based on observations in Europe and USA, there is also the possibility of false negativity because many infants with congenital toxoplasmosis are negative for IgM antibodies at birth (Guerina et al. Reference Guerina, Hsu, Meissner, Maguire, Lynfield, Stechenberg, Abroms, Pasternack, Hoff, Eaton, Grady, Cheeseman, McIntosh, Medearis, Robb and Weiblen1994; Lebech et al. Reference Lebech, Andersen, Christensen, Hertel, Nielsen, Peitersen, Rechnitzer, Larsen, Norgaard-Pedersen and Petersen1999; Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011). It is also important to note the issue of false positivity if the newborn IgM tests are not confirmed with follow-up confirmatory tests in the mother and infant. The specificity of various IgM tests used is also of concern (Remington et al. Reference Remington, McLeod, Wilson, Desmonts, Remington, Klein, Wilson, Nizet and Maldonado2011). As stated earlier, there is no national laboratory for confirmation of T. gondii serological testing in Brazil.

The most accurate figures on congenital toxoplasmosis prevalence are provided by the study by Vasconcelos-Santos et al. (Reference Vasconcelos-Santos, Azevedo, Campos, Oréfice, Queiroz-Andrade, Carellos, Romanelli, Januário, Resende, Martins, Carneiro, Vitor and Caiaffa2009). In this study, blood samples were collected from 146 307 newborns at 1560 public health care centres in 853 cities in the state of Minas Gerais. All serological testing was performed in one laboratory initially using an IgM-ELISA capture test kit (Toxo IgMQ-Preven, Symbiosis, Leme, Brazil) and results were confirmed on further testing for IgA antibodies (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) and IgG and IgM anti-T. gondii (enzyme-linked fluorometric assay, VIDAS, BioMérrieux SA, Lyon, France), using blood samples from infants and their mothers. Additionally, infected children were followed clinically months after delivery (Vasconcelos-Santos et al. Reference Vasconcelos-Santos, Azevedo, Campos, Oréfice, Queiroz-Andrade, Carellos, Romanelli, Januário, Resende, Martins, Carneiro, Vitor and Caiaffa2009; de Resende et al. Reference de Resende, de Andrade, de Azevedo, Perissinoto and Vieira2010). Congenital toxoplasmosis was suspected in 235 infants (1 in 622), and confirmed in 190 children (1 in 770 live births). This figure of 1 per 770 live births does not include in-utero mortality due to toxoplasmosis nor infants negative for IgM antibodies at birth.

According to the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE) (http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/projecao_da_populacao/2008/projecao.pdf) 2, 649 396 live births are projected in Brazil in 2015. If one assumes a rate of 1 infected child per 1000 births, 2649 children infected with congenital toxoplasmosis are likely to be born yearly in Brazil. Most of these infected children are likely to develop some symptoms or signs of clinical toxoplasmosis (Table 6).

Currently, there are no estimates of cost of caring for these infected children in Brazil, but financial burden on families and the government will be high. Based on the 1992 cost of living, the human illness losses due to congenital toxoplasmosis were estimated to be up to 8·8 billion dollars in the USA based on 1 infected child per 1000 live births (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Murrell and Marks1994). During the past 2 decades medical costs have sky rocketed (Stillwaggon et al. Reference Stillwaggon, Carrier, Sautter and McLeod2011). As stated earlier the morbidity due to congenital toxoplasmosis in Brazil is much higher than in the other parts of the world (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Freeman, Lago, Bahia-Oliveira, Tan, Wallon, Buffolano, Stanford and Petersen2008; Melamed et al. Reference Melamed2009). Clinical data on congenitally infected children in Brazil in the last 2 decades are summarized in Table 6. Based on those studies whose methodology allows us to estimate morbidity rates, approximately 35% of children had neurological disease including hydrocephalus, microcephaly and mental retardation, approximately 80% had ocular lesions, and in one report 40% of children had hearing loss. Several deaths occurring soon after birth, as a result of congenital toxoplasmosis, have been described. It is remarkable that in 2 studies from Minas Gerais, 2 decades apart, the percentages of children with retinal disease are similar (77% of 74, Bahia et al. Reference Bahia, Oréfice and de Andrade1992, and 80% of 178 Vasconcelos-Santos et al. Reference Vasconcelos-Santos, Azevedo, Campos, Oréfice, Queiroz-Andrade, Carellos, Romanelli, Januário, Resende, Martins, Carneiro, Vitor and Caiaffa2009).

As stated earlier, currently, there are no economic estimates with respect to impact of clinical toxoplasmosis in Brazil. Recently, Stillwaggon et al. (Reference Stillwaggon, Carrier, Sautter and McLeod2011) provided an extensive guideline for estimating costs of preventive maternal screening for and the social costs resulting from toxoplasmosis based on studies in Europe and the USA. While estimating these costs, the value of all resources used or lost should be considered, including the cost of medical and non-medical services, wages lost, cost of in-home care, indirect costs of psychological impacts borne by the family for life-time care of a substantially cognitively impaired child; cost of fetal death was estimated to be $5 million dollars (Stillwaggon et al. Reference Stillwaggon, Carrier, Sautter and McLeod2011).

Although it is unethical to value human life in terms of dollars, each nation has to balance public funding for all the needs of its people, including prevention of crippling ailments. Brazil has one of highest rates of T. gondii infection (50–80%) in women before their first pregnancy. Therefore, these seropositive women are considered immune, and can be excluded from future screening for toxoplasmosis if the infection in Brazil is the same as documented so carefully in France by Desmonts and Couvreur (Reference Desmonts and Couvreur1974) in earlier decades. At issue are pregnant women who are seronegative; their chances of acquiring T. gondii infection during pregnancy are high because the environment is highly contaminated with oocysts. Preventive measures (hygiene education, possible immunization if a vaccine for toxoplasmosis becomes available) should start in elementary schools since as many as 50% of 10-year-old children in many localities in Brazil had been exposed to T. gondii (Table 3).

Post-natal toxoplasmosis

Pregnant women

It has been suggested by Avelino et al. (Reference Avelino, Campos, de Parada and de Castro2003) that women in Brazil are more susceptible to T. gondii infection during pregnancy but there is no definitive evidence for this assumption. However, it is a fact that pregnancy induces immunosuppression and thus toxoplasmosis maybe more severe clinically in pregnant than in non-pregnant women. Judging from the published information it seems that only a small proportion of women who become infected in pregnancy have recognized symptomatic clinical toxoplasmosis. In Lyon, France, where all pregnant women are tested for T. gondii infection, only 36 (5% of 603) recalled any clinical symptoms simulating toxoplasmosis (Dunn et al. Reference Dunn, Wallon, Peyron, Petersen, Peckham and Gilbert1999). In Europe, the severity of toxoplasmosis in the fetus or the infant is not related to the degree of symptoms of T. gondii infection in the mother (Dunn et al. Reference Dunn, Wallon, Peyron, Petersen, Peckham and Gilbert1999; Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Dunn, Wallon, Hayde, Prusa, Lebech, Kortbeek, Peyron, Pollak and Petersen2001), but such data are not available for Brazil. Limited information suggests that clinical toxoplasmosis in the pregnant woman may be more severe in Brazil than in Europe. In a prenatal follow up of 204 women who became infected with T. gondii during pregnancy, 58 (28·4%) were symptomatic (Castilho-Pelloso et al. Reference Castilho-Pelloso, Falavigna and Falavigna-Guilherme2007). These symptoms included headaches in 58 (100%), concomitant symptoms in 45 (77·5%) with visual disturbances, myalgia in 35 (58%), and lymphadenopathy with fever in 24 (41·3%).

Immunocompetent persons

Clinical toxoplasmosis is rarely recognized in immunocompetent adults in Brazil, except in special circumstances. Silva et al. (Reference Silva, de Souza Neves, Benchimol and de Moraes2008) reported acute toxoplasmosis in a group of 313 patients who were seen because of toxoplasmosis like symptoms at a specialized hospital in the city of Rio de Janeiro from 1992 to 2004. Records of these patients were studied retrospectively, and the inclusion criteria were serology for acute infection including IgM and IgA testing, and symptoms. Most of these (65·5%) were child-bearing age women (27·2% pregnant). Clinical signs or symptoms were noted in 261; lymphadenopathy in 59·8%, fever in 27·2%, headache in 10·7%, weakness in 10·0%, weight loss in 8·4%, myalgia in 8%, and hepatosplenomegaly in 1·5%. Nine patients developed retinochoroiditis, 7 had ocular lesions at the time of admission and 2 developed lesions 2 years after initial visit. Of particular interest is that 26 symptomatic patients were children 10 years or younger; to our knowledge this is one of the first reports of clinically acquired toxoplasmosis in children in Brazil. Similar clinical signs were documented by Neves et al. (Reference Neves, Bicudo, Carregal, Bueno, Ferreira, Amendoeira, Benchimol and Fernandes2009) who enrolled 37 symptomatic patients (22 males, 15 females) in a 30-month prospective study. To be included in the sampling, patients had to present with at least 1 of the following signs or symptoms of acquired toxoplasmosis: fever, lymph node enlargement, weight loss or retinochoroiditis. These patients in 2006–2008 attended a clinic in Rio de Janeiro and had ascending IgM and IgG antibody titres to T. gondii. Frequency (%) of symptoms and laboratory findings in these 37 patients were: lymph node enlargement 94·6, asthenia 86·5, headache 70·3, fever 67·6, weight loss 67·2, and retinochoroiditis 10·8.

Unusually severe acute toxoplasmosis was noted in two 41-year-old men who had fever, myalgia, nausea, and severe headache; these were unrelated reports (Leal et al. Reference Leal, Cavazzana, de Andrade, Galisteo, de Mendonça and Kallas2007; de Souza Neves et al. Reference de Souza Neves, Kropf, Bueno, Bonna, Curi, Amendoeira and Fernandes Filho2011). The first patient from São Paulo was admitted to a hospital with an 8-day history of fever, myalgia, and headache followed by 4 days of nausea and vomiting (Leal et al. Reference Leal, Cavazzana, de Andrade, Galisteo, de Mendonça and Kallas2007). On the second day of hospitalization he developed pulmonary insufficiency with bilateral pneumonitis. He was successfully treated with sulfadiazine, pyrimethamine, corticosteroids and folinic acid. The diagnosis was supported by positive findings of IgM and IgG antibodies to T. gondii.

The other patient was admitted to an emergency unit of a hospital in Rio de Janeiro also with a history of fever, myalgia, nausea, and severe headache (de Souza Neves et al. Reference de Souza Neves, Kropf, Bueno, Bonna, Curi, Amendoeira and Fernandes Filho2011). He later developed meningeal signs, pneumonia, and cervical lymphadenopathy. Diagnosis was supported by increasing levels of IgG and IgM antibodies. The patient was treated successfully with anti-T. gondii therapy comprised of intravenous clindamycin and oral pyrimethamine.

Acute toxoplasmosis outbreaks

An epidemic of febrile adenopathy simulating toxoplasmosis was observed in 1966 in a University in São José dos Campos, 100 km from São Paulo city (Magaldi et al. Reference Magaldi, Elkis, Pattoli, de Queiróz, Coscina and Ferreira1967, Reference Magaldi, Elkis, Pattoli and Coscina1969). Between March and May 1966, 99 out of 500 students became ill. Symptoms reported were: fever in 79, lymph node enlargement in 61, asthenia in 52, headache in 32, sore throat in 17, and myalgia in 10. High titred T. gondii antibodies were found in most patients, and titres were still rising 6 months later. Another group of 22 people (not students) also had a similar syndrome. No risk assessment was performed because the life cycle of T. gondii was unknown at that time.

An outbreak of toxoplasmosis was reported in people from a farm in rural Além Paraíba, Minas Gerais (Coutinho et al. Reference Coutinho, Morgado, Wagner, Lobo and Sutmoller1982b). Nine of 36 persons living on a dairy farm developed illness characterized by fever, headache, and lymphadenopathy; all of them had serological evidence of acute toxoplasmosis. The illness was noted in May 1976, one month after the farmer had a party and served barbecued pork from a pig killed on the farm. The source of T. gondii infection was not determined. Viable T. gondii was isolated from soil samples collected from the farm but the year of soil sampling was not stated (Coutinho et al. Reference Coutinho, Lobo and Dutra1982a). Two outbreaks were circumstantially linked to eating mutton (Bonametti et al. Reference Bonametti, Passos, da Silva and Macedo1997b) or pork (de Almeida et al. Reference de Almeida, de Alencar, do Carmo, de Araújo, Garcia, Reis, Figueiredo, Sperb, Branco, Franco and Hatch2006), and in both of these instances a child developed acute toxoplasmosis after drinking mother's milk. Sixteen of 17 people who feasted on raw mutton while attending a party in Paraná, Brazil in September, 1993 became ill, all 16 developed fever, headaches, myalgia, arthralgia, and cervical lymphadenopathy, and 1 also had retinochoroiditis (Bonametti et al. Reference Bonametti, Passos, da Silva and Bortoliero1997a, Reference Bonametti, Passos, da Silva and Macedob). Among these patients was a mother with a nursing child. The child developed fever, malaise, and irritability, and had both IgG and IgM antibodies; and the child was fed exclusively on mother's milk. The mother's illness began 3 weeks before the child became ill.

The second case of acquired toxoplasmosis was in a 2-month-old baby diagnosed by one of the authors (Eleonor Lago). The infant was fed exclusively on mother´s milk. The mother had symptoms of acute toxoplasmosis beginning 1 month after delivery, including fever. Ten members of the same family (including this mother and her baby), and another 1-year-old child from a different mother had acute acquired toxoplasmosis. Eight of 10 were symptomatic, with cervical lymphadenopathy and myalgia in 8, fever and night sweats in 7, and headache in 6 patients. Another adult woman had acute active toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. The family had consumed raw pork sausage at a party in Santa Vitória do Palmar, RS (de Almeida et al. Reference de Almeida, de Alencar, do Carmo, de Araújo, Garcia, Reis, Figueiredo, Sperb, Branco, Franco and Hatch2006).

In May 1999, 113 people at a university campus had evidence of lymphoglandular toxoplasmosis, thought to be associated with contamination of food and water with T. gondii oocysts at the university cafeteria (Gattás et al. Reference Gattás, Nunes, Soares, Pires, Pinto and de Andrade2000-published only as an abstract of a meeting). There were more than 200 cats on the campus. No new cases were observed when filtered (2 μm filter to remove larger particles including T. gondii oocysts) water was served, and efforts were made to control the cat population.

One of the largest outbreaks of clinical toxoplasmosis occurred in Santa Isabel do Ivaí Paraná (Daufenbach et al. Reference Daufenbach, Alves, Carmo, Wanderley, de Azevedo, Elisbão, Santos, Vasconcelos, da Silva, da Silva, Arduino and Hatch2002; de Moura et al. Reference de Moura, Bahia-Oliveira, Wada, Jones, Tuboi, Carmo, Ramalho, Camargo, Trevisan, Graça, da Silva, Moura, Dubey and Garrett2006). The outbreak peaked between November 2001 and January 2002. A total of 426 persons had IgM and IgG antibodies to T. gondii out of 2884 serologically tested (area population 6771). Of these 156 persons participated in the clinical study. The main symptoms were headache (87%), fever (82%), myalgia (80%), lymphadenopathy (75%), anorexia (69%), arthralgia (61%), night sweats (53%), vomiting (38%), and rash (7%) (de Moura et al. 2006). Subsequently, 408 patients from this outbreak were examined for ocular lesions and IgG and IgM T. gondii antibodies; 18 had typical lesions of retinochoroiditis (15 unilateral, 3 bilateral), 24 had atypical superficial retinal lesions. Ten women seroconverted during pregnancy, 6 babies were born with congenital toxoplasmosis, 4 with ocular lesions, and 1 with neurological signs. One woman had lesions in both of her eyes and both eyes of her infant also were affected (Silveira, Reference Silveira2002; Dubey, Reference Dubey2010a). This outbreak was epidemiologically linked to a cistern that supplied municipal water. Viable T. gondii was isolated from water tanks on roof tops that temporarily stored water (de Moura et al. Reference de Moura, Bahia-Oliveira, Wada, Jones, Tuboi, Carmo, Ramalho, Camargo, Trevisan, Graça, da Silva, Moura, Dubey and Garrett2006). Viable T. gondii isolates were also obtained from a cat that was associated with a water cistern, domestic cats from homes in the city (Dubey et al. Reference Dubey, Navarro, Sreekumar, Dahl, Freire, Kawabata, Vianna, Kwok, Shen, Thulliez and Lehmann2004) and feral chickens from the city centre and adjoining area in Santa Isabel do Ivaí (Dubey et al. 2003). Although no attempts were made to isolate T. gondii from sick people a seroepidemiological study based on peptide typing of sera from patients from the outbreak linked the infection to the isolate from the water tank (Vaudaux et al. Reference Vaudaux, Muccioli, James, Silveira, Magargal, Jung, Dubey, Jones, Doymaz, Bruckner, Belfort, Holland and Grigg2010).

Ocular toxoplasmosis

Ocular disease is probably the most common potentially severe symptomatic manifestation in acute, post-natally acquired toxoplasmosis (Holland, Reference Holland2009). Until the 1980s, most of T. gondii retinochoroiditis was thought to be congenital (Holland, Reference Holland2003). Ophthalmologists from Brazil first reported retinochoroiditis in multiple siblings, and in patients who acquired infection later in life (Silveira et al. Reference Silveira, Belfort, Burnier and Nussenblatt1988, Reference Silveira, Belfort, Muccioli, Abreu, Martins, Victora, Nussenblatt and Holland2001). These findings have now been amply confirmed in many countries. Currently, most of the eye disease is thought to be post-natally acquired because <1% of the population becomes infected congenitally (Glasner et al. Reference Glasner, Silveira, Camargo, Kim, Nussenblatt, Belfort and Kaslow1992a, Reference Glasner, Silveira, Kruszon-Moran, Martins, Burnier, Silveira, Camargo, Nussenblatt, Kaslow and Belfortb). The prevalence of ocular toxoplasmosis in Brazil is considered to be high (Table S3, online version only). Glasner et al. (Reference Glasner, Silveira, Kruszon-Moran, Martins, Burnier, Silveira, Camargo, Nussenblatt, Kaslow and Belfort1992b) reported 17·7% prevalence of ocular toxoplasmosis in patients examined at Clínica Silveira in Erechim, southern Brazil. Erechim is mainly rural with a temperate climate and predominantly Italian, German, and Polish immigrant population. A door-to-door survey identified 1042 subjects (63% of the population) who participated in the study; all were examined for ocular lesions and had blood drawn for T. gondii serology. Prevalence increased with age; 4·3% of those 9–12 years old, 14·3% of those 13–16 years old and 24·6% of those 17–20 years old had ocular lesions. All but 1 patient (183 of 184) had antibodies to T. gondii and the prevalence was similar in males and females. This prevalence of ocular toxoplasmosis in Erechim is more than 10-fold higher than the prevalence in the USA (Jones and Holland, Reference Jones and Holland2010).

A follow-up study performed a decade later evaluated risk factors associated with ocular toxoplasmosis in the same locality (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Muccioli, Belfort, Holland, Roberts and Silveira2006). For this study, 131 infected and 110 uninfected controls were selected from the patients with eye disease who were evaluated at the Clínica Silveira for 12 months starting June 2003. All infected patients had IgG and IgM antibodies to T. gondii, indicating recently acquired infection. The controls were patients without T. gondii antibodies and seen at the same time as infected patients. Age, gender, race and ethinicity data were recorded, and all participitants completed a detailed questionnaire. Salient risk factors associated with toxoplasmosis were: eating rare meat, eating home-made cured, dried or smoked meat, having a garden, having soil-related activity, being male, and past and present pregnancy (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Muccioli, Belfort, Holland, Roberts and Silveira2006). The association of pregnancy and the number of children as a risk factor for toxoplasmosis is intriguing and has been observed previously in Brazil (Avelino et al. Reference Avelino, Campos, de Parada and de Castro2003).

Another impressive population-based study on ocular toxoplasmosis prevalence was reported by Portela et al. (Reference Portela, Bethony, Costa, Gazzinelli, Vitor, Hermeto, Correa-Oliveira and Gazzinelli2004). A door-to-door survey was conducted in rural Melquíades, northeast Governador Valadares, MG within a 100 km area of a village. A total of 414 persons were enrolled in the study. Half (49%) of them had T. gondii antibodies with a very high (47% of 49) seroprevalence in children less than 9 years old. A total of 29 of 414 (7%) persons had ocular lesions; 28 of these were seropositive, and 1 was seronegative. Overall, 28 (12·9%) of 216 seropositives had ocular lesions, and only 1 (0·5%) of 198 seronegatives had ocular lesions suggestive of toxoplasmosis. None of the 49 children had ocular toxoplasmosis, although 47% were seropositive. These data affirm that most ocular toxoplasmosis is post-natally acquired. A retinal scar was the most common lesion and predominated in persons older than 50 years. Shared residence was a risk factor for ocular toxoplasmosis, suggesting a common source of seropositivity among household members. It will be seen from data summarized in Table S3 that the prevalence of ocular toxoplasmosis differs with respect to region and the age groups studied. Using similar methods prevalence was 10-fold higher in Erechim (25·5% in patients up to 21 year olds, Glasner et al. Reference Glasner, Silveira, Kruszon-Moran, Martins, Burnier, Silveira, Camargo, Nussenblatt, Kaslow and Belfort1992b) than in Natal (1·15% in 5–21 year- olds, de Amorim Garcia et al. Reference de Amorim Garcia, Oréfice, de Oliveira Lyra, Bezerra Gomes, França and de Amorim Garcia Filho2004). Ocular lesions were found in 11 of 959, 5 to 21-year-old students attending public schools in Natal; lesions were bilateral in 1 student but with 20/20 vision (de Amorim Garcia et al. Reference de Amorim Garcia, Oréfice, de Oliveira Lyra, Bezerra Gomes, França and de Amorim Garcia Filho2004). Overall, lesions were less severe in these students than in patients in Erechim.

As stated earlier, although most reports of ocular toxoplasmosis were from the Clínica Silveira in Erechim, the disease is probably common in the rest of the Brazilian population, and toxoplasmosis has been recognized as an important cause of uveitis in Brazil since late 1970's (Belfort et al. Reference Belfort, Hirata and de Abreu1978; de Abreu et al. Reference de Abreu, Hirata, Belfort and Neto1980, Reference de Abreu, Belfort and Hirata1982; Petrilli et al. Reference Petrilli, Belfort, Moreira and Nishi1987; Silveira et al. Reference Silveira, Belfort and Burnier1987; Pinheiro et al. Reference Pinheiro, Oréfice, Andrade and Caiaffa1990; Glasner et al. Reference Glasner, Silveira, Kruszon-Moran, Martins, Burnier, Silveira, Camargo, Nussenblatt, Kaslow and Belfort1992b; Schellini et al. Reference Schellini, Zambrim, Amarante, Jorge and Silva1993; Reis et al. Reference Reis, Soares, Watanabe, Colombini and Leite1998a, Reference Reis, Campos and Fernandesb; Sebben et al. Reference Sebben, Melamed, Silveira, Locatelli, Fridman and Ferretti1995; Abreu et al. 1998; de Carvalho et al. Reference de Carvalho, Minguini, Moreira and Kara-José1998; Jorge et al. Reference Jorge, de Moraes Silva, Nakamoto and Jorge2003; Gouveia et al. Reference Gouveia, Yamamoto, Abdalla, Hirata, Kubo and Olivalves2004; Oliveira and Reis, Reference Oliveira and Reis2004; do Carmo et al. Reference do Carmo, Bichara and Póva2005; Alvarenga et al. Reference Alvarenga, Couto and Pessoa2007; Haddad et al. Reference Haddad, Sei, Sampaio and Kara-José2007; Nóbrega and Rosa, Reference Nóbrega and Rosa2007; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, de Moraes, Malagueño, Ferreira, Cordeiro and Oréfice2008; Aleixo et al. Reference Aleixo, Benchimol, Neves, Silva, Coura and Amendoeira2009; de Souza and Casella, Reference de Souza and Casella2009; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Malagueño, Lynch, Ferreira, Stheling and Oréfice2009; Melamed, Reference Melamed2009; Diniz et al. Reference Diniz, Regatieri, Andrade and Maia2011; Mattos et al. Reference Mattos, Meira, Ferreira, Frederico, Hiramoto, Almeida, Mattos and Pereira-Chioccola2011). Even though toxoplasmosis can affect any part of the eye, retinochoroiditis is its hallmark (Silveira et al. Reference Silveira, Belfort, Nussenblatt, Farah, Takahashi, Imamura and Burnier1989; Hayashi et al. Reference Hayashi, Kim and Belfort1997; Holland et al. Reference Holland, Muccioli, Silveira, Weisz, Belfort and O'Connor1999; Silveira et al. Reference Silveira, Belfort, Muccioli, Abreu, Martins, Victora, Nussenblatt and Holland2001; Silveira, Reference Silveira2002; Yamamoto et al. Reference Yamamoto, Boletti, Nakashima, Hirata and Olivalves2003; Eckert et al. Reference Eckert, Melamed and Menegaz2007; Oréfice et al. Reference Oréfice, Costa, Oréfice, Campos, da Costa-Lima and Scott2007; Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, de Moraes, Malagueño, Ferreira, Cordeiro and Oréfice2008; Commodaro et al. Reference Commodaro, Belfort, Rizzo, Muccioli, Silveira, Burnier and Belfort2009; Melamed et al. Reference Melamed, Eckert, Spadoni, Lago and Uberti2009; Bottós et al. Reference Bottós, Miller, Belfort, Macedo, Belfort and Grigg2009; de Souza et al. Reference de Souza, DaMatta and Attias2009; Belfort et al. Reference Belfort, Rasmussen, Kherani, Lodha, Williams, Fernandes and Burnier2010; Arevalo et al. Reference Arevalo, Belfort, Muccioli and Espinoza2010; Delair et al. Reference Delair, Latkany, Noble, Rabiah, McLeod and Brézin2011). Ocular toxoplasmosis is the main cause of uveitis worldwide, and in Brazil it is responsible for 70% of the cases (de Amorim Garcia et al. Reference de Amorim Garcia, Oréfice, de Oliveira Lyra, Bezerra Gomes, França and de Amorim Garcia Filho2004). In retrospective studies conducted more than 20 years ago, bilateral toxoplasmic macular scars, optic atrophy, and congenital cataracts were the main cause of reduced vision in children in Brazil (Kara-José et al. Reference Kara José, de Carvalho, Pereira, Venturini, Gasparetto and Gushiken1988; Buchignani and Silva, Reference Buchignani and Silva1991; de Cavalho et al. Reference de Carvalho, Minguini, Moreira and Kara-José1998).

In human ocular toxoplasmosis, the parasite multiplies in the retina and inflammation occurs primarily in the choroid; the choroid alone is not affected. Early lesions of acquired toxoplasmosis are unknown because eyes are often not examined until the infection is symptomatic. Holland et al. (Reference Holland, Muccioli, Silveira, Weisz, Belfort and O'Connor1999) reported retinal vasculitis without necrosis in 10 Brazilian patients who had recently acquired toxoplasmosis. Eckert et al. (Reference Eckert, Melamed and Menegaz2007) reported optic nerve involvement in 5·3% of ocular toxoplasmosis in Brazil and in 23 of 51 eyes, optic nerve lesions preceded retinal lesions. Clinical diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis is difficult in the absence of retinal lesions, and it is often difficult to clinically distinguish congenital versus acquired toxoplasmosis, in both instances ocular lesions may develop several years after infection. However, in congenital infection ocular lesions are more often bilateral, serum IgG antibodies are often low in titre, and IgM is rarely detectable. Antibody levels in ocular patients may differ with respect to patients from different countries; levels of IgG were higher in Brazilian versus Swiss patients (Garweg et al. Reference Garweg, Ventura, Halberstadt, Silveira, Muccioli, Belfort and Jacquier2005). The severity of ocular toxoplasmosis may be influenced by the high virulence of the T. gondii genotype (Vallochi et al. Reference Vallochi, Muccioli, Martins, Silveira, Belfort and Rizzo2005; Bottós et al. Reference Bottós, Miller, Belfort, Macedo, Belfort and Grigg2009).

Definitive cure of ocular toxoplasmosis without recurrence is not possible because available anti-toxoplasmic medicines are not effective in killing tissue cysts present in the retina. Recurrences of retinochoroiditis in Brazilian patients are common in spite of treatment (Silveira et al. Reference Silveira, Belfort, Muccioli, Holland, Victora, Horta, Yu and Nussenblatt2002). A recent study showed that viable T. gondii can circulate in patients with eye disease in both acutely and chronically infected patients (Silveira et al. Reference Silveira, Vallochi, da Silva, Muccioli, Holland, Nussenblatt, Belfort and Rizzo2011).

Toxoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients

The HIV epidemic in the 1980s brought recognition of cerebral toxoplasmosis in adults, resulting from reactivation of latent infection. The percentage of T. gondii seropositive persons with AIDS that develop clinical toxoplasmosis varies. In the USA approximately 10% of seropositives developed clinical toxoplasmosis whereas this percentage was 25–30% of the seropositives in Europe; reasons for this variability are unknown (Luft and Remington, Reference Luft and Remington1992). Cerebral toxoplasmosis was definitively diagnosed in 8–34% of AIDS patients in Brazil who were examined at autopsy (Rosemberg et al. Reference Rosemberg, Lopes and Tsanaclis1986; Chimelli et al. Reference Chimelli, Rosemberg, Hahn, Lopes and Barretto Netto1992; Camara et al. Reference Camara, Tavares, Ribeiro and Dumas2003; Weinstein et al. Reference Wainstein, Ferreira, Wolfenbuttel, Golbspan, Sprinz, Kronfeld and Edelweiss1992; Cury et al. Reference Cury, Pulido, Furtado and da Palma2003; de Souza et al. Reference de Souza, Feitoza, de Araújo, de Andrade and Ferreira2008; Silva et al. Reference Silva, Rodrigues, Micheletti, Tostes, Meneses, Silva-Vergara and Adad2012; Table S4, online version only). However, T. gondii seroprevalence was not determined in these persons that were examined post-mortem. Passos et al. (Reference Passos, de Araújo Filho and de Andrade2000) retrospectively analysed records of 73 AIDS patients considered to have toxoplasmic encephalitis, 38 patients in 1988 (group A), and 33 patients in 1993 (group B) at the main hospital in São Paulo. Toxoplasma gondii antibodies were found in 81·2% (25 of 31) in group A and 61·5% (16 of 26) in group B patients; 21·1% (8 of 38) in group A and 30·3% (17 of 33) in group B died of toxoplasmosis. However, criteria for patient selection and diagnosis were ill defined. Neurological signs or symptoms, CT scan and anti-T. gondii therapy were considered in case selection; however, CT scan and T. gondii serological examination were not performed on all patients. It is worth noting that the definitive diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis should not be made based solely on the CT scan because lymphomas and other conditions may be mistaken for toxoplasmosis (Mentzer et al. Reference Mentzer, Perry, Fitzgerald, Barrington, Siddiqui and Kulasegaram2012).

There are other reports of toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients from different regions of Brazil (Chahade et al. Reference Chahade, de Faria Soares, Guimarães, Berbert, Szwarc and Levi1994; Nascimento et al. Reference Nascimento, Stollar, Tavares, Cavasini, Maia, Cordeiro and Ferreira2001; Nobre et al. Reference Nobre, Braga, Rayes, Serufo, Godoy, Nunes, Antunes and Lambertucci2003; Alves et al. Reference Alves, Magalhães and Gomes de Matos2010a, Reference Alves, Magalhães and Gomes de Matosb; Correia et al. Reference Correia, Melo and Costa2010). The incidence of cerebral toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients is now drastically reduced after the institution of highly active antiviral therapy (HAART). In one report based on 1138 HIV-infected patients admitted to a hospital in São Paulo, 115 (10%) were diagnosed with neural toxoplasmosis (Vidal et al. Reference Vidal, Hernandez, de Oliveira, Dauar, Barbosa and Focaccia2005). In 35% of these patients, neural toxoplasmosis led to the diagnosis of HIV infection and in 75% cerebral toxoplasmosis was the AIDS-defining disease. Of these 115 patients, 55 were followed clinically, 40 had headache and hemiparesis, 28 had confusion, 25 had fever, 11 had alterations of cranial nerves, 8 had visual alterations and 5 were ataxic. Of these 55 patients, cerebral toxoplasmosis was diagnosed at autopsy in 2 patients who had died within 2 weeks of initiation of HAART and anti-T. gondii therapy. De Oliveira et al. (Reference de Oliveira, Greco, Oliveira, Christo, Guimarães and Corrêa-Oliveira2006) reported a high (42·3%) prevalence of neural toxoplasmosis among 417 HIV patients admitted to hospital in Belo Horizonte, MG.

In most AIDS patients, toxoplasmosis is due to reactivation of latent infection and lesions are restricted to the central nervous system (CNS). Of 92 AIDS patients from a reference hospital in Brazil, examined at post-mortem in 1993–2000, 8 were diagnosed with toxoplasmosis, all with CNS involvement (Cury et al. Reference Cury, Pulido, Furtado and da Palma2003). In the brain, the predominant lesion is necrosis, often resulting in multiple abscesses, some of which are as large as a tennis ball. These abscesses often blend with normal tissue in which numerous tachyzoites and tissue cysts are present. As many as 1 million tachyzoites per ml or gramme of affected tissue can be present (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010a). Tissue cysts are often seen at the periphery and often differ in size. Such lesions are now rarely seen in patients treated for toxoplasmosis and HIV. Although any part of the brain may be involved, lesions are more common in the basal ganglia and appear as ring-enhancing lesions (Cota et al. Reference Cota, Assad, Christo, Giannetti, dos Santos and Xavier2008).Vidal et al. (Reference Vidal, Hernandez, de Oliveira, Dauar, Barbosa and Focaccia2005) noted diffuse cerebral necrosis in 2 patients that were examined at autopsy. These atypical diffuse cerebral infections might be caused by atypical genotypes of T. gondii (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Vidal, de Mattos, de Mattos, Qu, Su and Pereira-Chioccola2011). According to Pereira-Chioccola et al. (Reference Pereira-Chioccola, Vidal and Su2009) 20% of AIDS patients in Brazil have these atypical cerebral lesions.

In a few AIDS patients toxoplasmosis is generalized, affecting many organs. Barbosa et al. (Reference Barbosa, Molina, de Souza, Silva, Micheletti, dos Reis, Teixeira and Silva-Vergara2007) reported disseminated toxoplasmosis in 2 AIDS patients confirmed at autopsy. Severe myocarditis was found in 1 patient (Nobre et al. Reference Nobre, Braga, Rayes, Serufo, Godoy, Nunes, Antunes and Lambertucci2003). Ocular toxoplasmosis has been reported in 4–8% of AIDS patients (Rehder et al. Reference Rehder, Burnier, Pavesio, Kim, Rigueiro, Petrilli and Belfort1988; Muccioli et al. Reference Muccioli, Belfort, Lottenberg, Lima, Santos, Kim, de Abbreu and Neves1994; Matos et al. Reference Matos, Santos and Muccioli1999; Arruda et al. Reference Arruda, Muccioli and Belfort2004; Zajdenweber et al. Reference Zajdenweber, Muccioli and Belfort2005; Alves et al. Reference Alves, Magalhães and Gomes de Matos2010a, b), including a 13-month-old child (Moraes, Reference Moraes1999).

In the early days of the AIDS epidemic, diagnosis of cerebral toxoplasmosis was confirmed at autopsy (Table S5, online version only) or by needle biopsy of lesions suspected by computer tomography (CT) scan. Currently, diagnosis is aided by attempts to demonstrate live T. gondii parasites, antibodies to T. gondii or T. gondii antigens or T. gondii DNA in blood or CSF or even in saliva (Borges and Figueiredo, Reference Borges and de Castro Figueiredo2004; Vidal et al. Reference Vidal, Colombo, de Oliveira, Focaccia and Pereira-Chioccola2004; Colombo et al. Reference Colombo, Vidal, Penalva de Oliveira, Hernandez, Bonasser-Filho, Nogueira, Focaccia and Pereira-Chioccola2005; Meira et al. Reference Meira, Costa-Silva, Vidal, Ferreira, Hiramoto and Pereira-Chioccola2008; Nogui et al. Reference Nogui, Mattas, Turcato and Lewi2009; Correia et al. Reference Correia, Melo and Costa2010; Mesquita et al. Reference Mesquita, Ziegler, Hiramoto, Vidal and Pereira-Chioccola2010a, Reference Mesquita, Vidal and Pereira-Chioccolab; Meira et al. Reference Meira, Vidal, Costa-Silva, Frazatti-Gallina and Pereira-Chioccola2011). Obviously, use of peripheral blood for diagnosis is less invasive and good results were obtained using quantitative serology and DNA detection in cerebral toxoplasmosis (Vidal et al. Reference Vidal, Diaz, de Oliveira, Dauar, Colombo and Pereira-Chioccola2011).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The ingestion of oocysts from the environment and the consumption of meat infected with tissue cysts are the two most important modes of transmission of T. gondii. Determination of sources of infection is technically difficult because by the time T. gondii infection is diagnosed the original source of infection may not be demonstrable. Table S5 (online version only) summarizes some of the risk assessment studies for T. gondii infection in Brazil. Much of this epidemiological information was dependent on the type of questions asked and the answers obtained. The environment in many areas in Brazil is highly contaminated by oocysts, and thus it is difficult to pinpoint sources of infection. We will attempt to summarize available information regarding oocyst shedding and infection in meat animals. Among pregnant women, lower socio-economic level, lower level of education, higher age, soil handling, and contact with cats were considered the most important risk factors for T. gondii infection (Table S5, online version only).

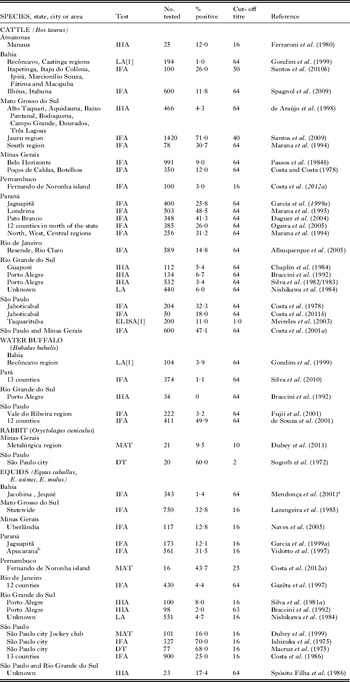

Transmission by oocysts

Cats (both domestic and wild) are the only animals that can excrete T. gondii oocysts. A cat can excrete millions of oocysts, which can survive in the environment for months, depending on moisture and temperature (Dubey, Reference Dubey2010a). Free-roaming domestic cats are abundant in public places in Brazil. Relatively little is known of the prevalence of T. gondii in cats in Brazil, and 7 of 15 surveys were from the São Paulo State (Table 7). Seroprevalence was low in cats sampled in clinics, but these were probably pets and were most likely fed processed food (Table 7).

Table 7. Prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in domestic cats in Brazil

a Veterinary clinic.

b Zoonosis Center.

Of these surveys, the most comprehensive study was that reported by Pena et al. (Reference Pena, Soares, Amaku, Dubey and Gennari2006). In that study an equal number of male and female (118 males, 119 females) stray cats were captured from 15 counties in São Paulo State in 2003. Antibodies to T. gondii were found in 84 (35·4%) of 237 cats. Tissues of 71 seropositive cats were bioassayed in mice and viable T. gondii was isolated from 66·2% (47 cats).

During the epidemiological study of a waterborne outbreak in Santa Isabel do Ivaí, Paraná, 58 adult cats were obtained from 51 houses around this town (Dubey et al. Reference Dubey, Navarro, Sreekumar, Dahl, Freire, Kawabata, Vianna, Kwok, Shen, Thulliez and Lehmann2004). All cats were serologically tested as well as by bioassay, irrespective of their antibody status. Antibodies to T. gondii were found in 49 (84·4%) of 58 cats, and viable T. gondii was isolated from 37 of 54 (68·5%) of these cats. This study indicated that more than 80% of homes in this area had a T. gondii-infected cat.

Cats start shedding T. gondii within 10 days of consuming infected tissues and they shed oocysts only for 1–2 weeks (Dubey and Frenkel, Reference Dubey and Frenkel1972). During the period of oocyst shedding cats are rarely ill and they do not have antibodies to T. gondii. Thus, it is a reasonable assumption that most seropositive cats have already shed oocysts. Therefore for epidemiological studies, seroprevalence data are more meaningful than determining the prevalence of oocysts in feces. Moreover, at any given time-period only 1% of cats are found shedding oocysts (Jones and Dubey, Reference Jones and Dubey2010). This low rate of fecal positivity of oocysts was also exemplified in the report by Pena et al. (Reference Pena, Soares, Amaku, Dubey and Gennari2006); T. gondii oocysts were found in only 3 of 237 (1·2%) cats. Early reports from Brazil also indicate a low prevalence of T. gondii-like oocysts in cat feces (Barbosa et al. Reference Barbosa, Fernandes, Pinheiro, Teixeìra and de Oliveira1973; Nery-Guimarães and Lage Reference Nery-Guimarães and Lage1973; do Amaral et al. Reference Amaral, Santos, Ribeiro and Rebouças1976b; Ogassawara et al. Reference Ogassawara, Benassi, Hagiwara and Larsson1980; Chaplin et al. Reference Chaplin, Silva and Araújo1991).

Based on 12 million cats, a seropositivity of 25–50%, and shedding of 1 million oocysts per cat there could be large numbers of oocysts in the environment in Brazil. In addition to domestic cats, wild felids can shed oocysts. Toxoplasma gondii oocysts have been demonstrated in feces of several species of naturally and experimentally infected wild felids (Jones and Dubey, Reference Jones and Dubey2010). Brazil is home to several species of wild Felidae, especially in zoos (Table S6, online version only).

Epidemiological surveys, especially in pre-teen children (Table 3) imply that the environment is highly contaminated with oocysts, especially in lower socio-economical communities. Dos Santos et al. (Reference dos Santos, Nunes, Luvizotto, de Moura, Lopes, da Costa and Bresciani2010) found T. gondii oocysts in 7 of 31 soil samples from 31 elementary public-school playgrounds in the northwest area of São Paulo State. This is an alarming rate of soil contamination due to T. gondii oocysts. Coutinho et al. (Reference Coutinho, Lobo and Dutra1982a) also found T. gondii in soil samples from a farm where an outbreak of T. gondii had occurred. In earlier studies in Porto Alegre, RS, Chaplin et al. (Reference Chaplin, Silva and Araújo1991) found Toxoplasma-like oocysts in feces of 13 of 15 young cats, and Braccini et al. (Reference Braccini, Chaplin, Stobbe, Araújo and Santos1992) reported oocysts in feces of 5 of 25 cats. However, microscopic diagnosis was not confirmed by bioassays in mice. Drinking water could be easily contaminated with oocysts (Bahia-Oliveira et al. Reference Bahia-Oliveira, Jones, Azevedo-Silva, Alves, Oréfice and Addiss2003). Technically, it is difficult to find T. gondii oocysts in water because the number of oocysts in water is low due to the dilution factor (de Moura et al. Reference de Moura, Bahia-Oliveira, Wada, Jones, Tuboi, Carmo, Ramalho, Camargo, Trevisan, Graça, da Silva, Moura, Dubey and Garrett2006).

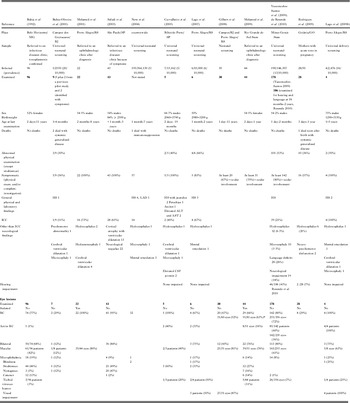

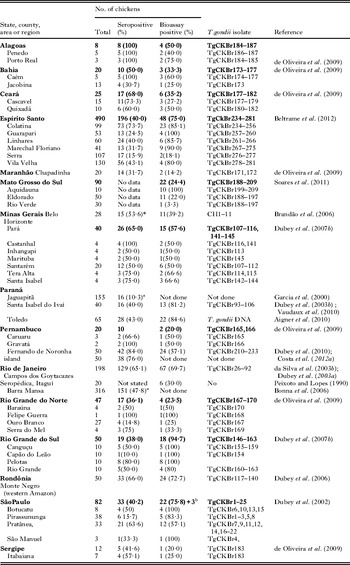

Another epidemiological means to assess soil contamination due to oocysts is to determine T. gondii prevalence in animals that feed from the ground. The authors have used free-range (FR) chickens (Gallus domesticus) for this purpose. This collaborative project was initiated by 2 of us (J.P. Dubey and S. Gennari) in 2000. Our initial objectives were to determine the prevalence of T. gondii infection in FR chickens, and isolate viable T. gondii to study genetic diversity. Subsequently, these studies were extended to other livestock and wild animals. Chickens were obtained from individual properties that were approximately 1 km apart. The number of chickens from one property was no more than 6 to minimize the clustering effect. Chickens were purchased, killed, bled, and serologically and parasitologically tested. Attempts were made to bioassay 50 or more chickens from each area irrespective of the serological status of chickens. Infected chickens were found on most properties or individual houses sampled (Table 8).

Table 8. Serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in free-range chickens from different states, counties or areas of Brazil

a IFA, others were done by MAT.

b Additional isolates from tissues pooled from several chickens.

In addition to indicators of soil contamination these infected chickens could be a source of infection for cats and possibly humans. These FR chickens are frequently slaughtered at home and viscera are often not properly disposed off. Although chickens are usually cooked well before human consumption, improper hygiene while handling and cooking chickens could be a source of infection for people.

Oocyst shedding by wild felids

A large number of wild felids in most of the zoological parks and breeding centres in Brazil had antibodies to T. gondii (Table S6, online version only). Pena et al. (Reference Pena, Marvulo, Horta, Silva, Silva, Siqueira, Lima, Vitaliano and Gennari2011) isolated viable T. gondii from muscles of a captive jaguarandi that died of trauma. There is no information concerning prevalence of T. gondii in free-ranging wild felids in Brazil. The high seropositivity in captive wild felids suggests that they have already shed oocysts and contaminated the zoo environment. In isolated Amerindians, Mato Grosso, 80·4% of 148 people surveyed had T. gondii antibodies (Amendoeira et al. Reference Amendoeira, Sobral, Teva, de Lima and Klein2003). These people live on a large area with little contact with non-Indians, do not have pet cats, and do not eat meat. They eat insects and vegetables, including mushrooms. The authors speculate that T. gondii oocysts excreted by wild felids in the area could contaminate soil and vegetation. In one report 86·3% of 95 free-ranging Amazon River dolphins from Amazonas were seropositive to T. gondii (Table S7, online version only). These herbivorous dolphins most likely became infected by ingesting river waters contaminated with oocysts from wild felids (most likely jaguars) because domestic cats are unlikely in this environment.

Role of dogs in transmission of T. gondii

There have been no epidemiological studies to assess transmission of T. gondii from dogs to people in Brazil but antibodies to T. gondii have been reported widely in dogs in Brazil (Table S7, online version only). How dogs become infected with T. gondii is unknown. They do serve as indicators of environmental contamination with T. gondii because of close association with humans. Higher T. gondii prevalence in stray and farm dogs than in pets suggests that eating infected prey is an important source of infection (de Souza et al. 2003).

Transmission by infected meat

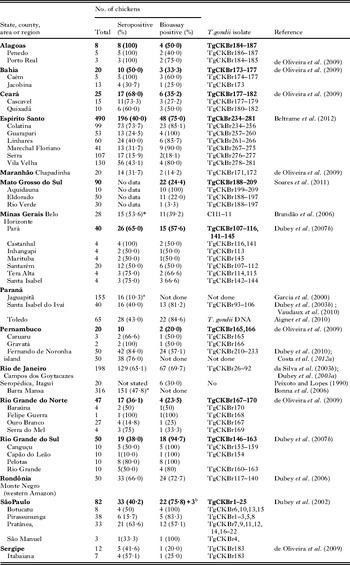

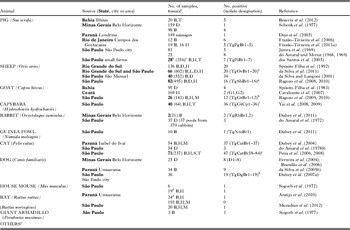

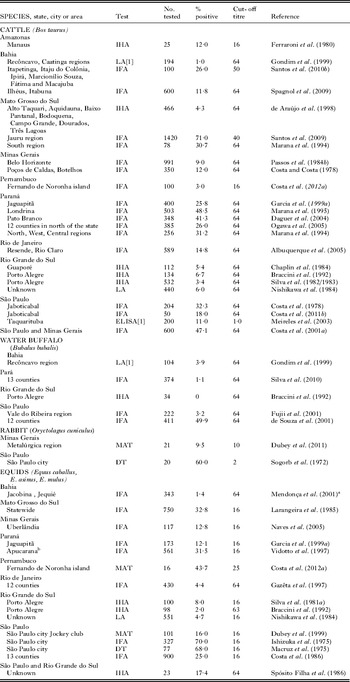

Millions of food animals are slaughtered for human consumption yearly in Brazil. Serological surveys indicate that up to 90% of domestic and wild animals had antibodies to T. gondii, and viable T. gondii was isolated from a variety of animals in Brazil. Details of isolation by bioassays are as follows:

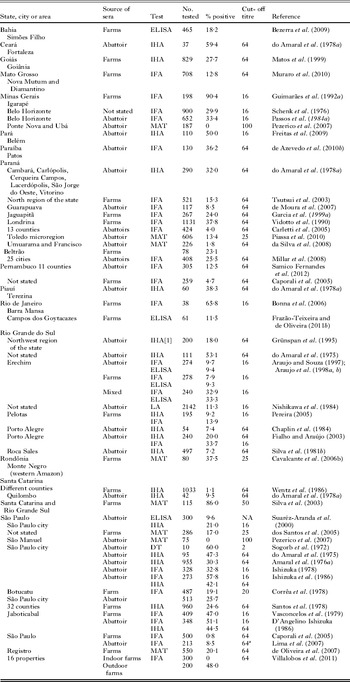

Pigs

Up to 90% of pigs surveyed in Brazil had T. gondii antibodies (Table 9), and viable parasites were isolated from tissues of pigs (Table 10). Jamra et al. (Reference Jamra, Deane and Guimarães1969) tested 83 samples of pork from butcher shops, and grocery stores in São Paulo city but there is no information on the number of pigs that were the sources for these pork samples; 5 samples contained viable T. gondii. At about the same time Amaral and Macruz (1968, 1969) found viable T. gondii in 8 of 25 diaphragms, also from São Paulo. Frazão-Teixeira et al. (Reference Frazão-Teixeira, de Oliveira, Pelissari-Sant’ Ana and Lopes2006, Reference Frazão-Teixeira, Sundar, Dubey, Grigg and de Oliveira2011) isolated viable T. gondii from samples of brains and hearts from the butcher shops in Campos dos Goytacazes, RJ but it is uncertain if the hearts and brains were from the same or different pigs. Bezerra et al. (Reference Bezerra, Carvalho, Guimarães, Rocha, Silva, Wenceslau and Albuquerque2012) isolated viable T. gondii by bioassay of pooled brains and tongues of 5 of the 20 pig heads from small farms and pork butchers in Ilhéus, Bahia. In these studies, the sources of pigs, their ages, and serological status were unknown. Dos Santos et al. (Reference dos Santos, de Carvalho, Ragozo, Soares, Amaku, Yai, Dubey and Gennari2005) tested 286 market-age 6–8 month old pigs, from 17 small poorly managed farms in Jaboticabal, SP. Of these, 49 (17%) were seropositive by MAT. Tissues were collected for bioassay when these pigs were slaughtered. Viable T. gondii was isolated from tissues of 7 (MAT titres 100–1 pig, 200–4 pigs, 1600–2 pigs) pigs. Such information is needed for market-age pigs raised under different management conditions in Brazil.

Table 9. Serological prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in pigs in Brazil

a Personal communication.

Table 10. Isolation of viable Toxoplasma gondii from animals in Brazil

a B = brain, H = heart, L= lung, M = skeletal muscle, S = spleen, T = tongue.

b Figures in bold are the number of seropositive animals bioassayed.

c Figures in parenthesis are the number of animals serologically tested.

d Seronegative (MAT < 1:10).

e Pena et al. (Reference Pena, Marvulo, Horta, Silva, Silva, Siqueira, Lima, Vitaliano and Gennari2011) isolated viable T. gondii from 1 BLACK-EARED OPOSSUM (Didelphis aurita, designatedTgOpBr1), 1 JAGUARUNDI (Puma yagouaroundi, designatedTgJaBr1), and 1 HOWLER MONKEY (Alouatta belzebul, designated TgRhHum1) that died in captivity of unrelated causes.

f TgOvBr 1–4, 6–8, 10, 15, 18, 20 from counties Santana do Livramento, TgOvBr 5, 9, 13, 14 Uruguaiana in state of RS, and TgOvBr11,16 from county Ourinhos, 12, 19 Pirajuí, TgOvBr 17 Mandur were from the state of Sao Paulo.

g Isolates from counties: Presidente Prudente (TgShBr1,2), Araçariguama (TgShBr3,4), Araçatuba (TgShBr5), Marilia (TgShBr6,7), Botucatu (TgShBr 8,9), Coronel Macedo (TgShBr10), Dracena (TgShBr11), Engenheiro Coelho (TgShBr12,13,14), Tietê (TgShBr 15,16).

h Isolates from counties: Botucatu, São Paulo (TgGtBr1–7,9, 11, 12), Jardim do Seridó, Rio Grande Norte (TgGtBr8) and Ouro Branco, Rio Grande Norte (TgGtBr10).

i Isolates from counties: Andradina (TgBrCp1–7), Cordeirópolis TgBrCp8–16), Cosmorama (TgBrCp17–22), Ribeirão Preto (TgBrCp23,24), São Paulo (TgBrCp25–31) and Valparaíso (TgBrCp32–36).

j Isolates from counties: Araçariguama (TgCatBr38–41), Colina (TgCatBr42), Conchas (TgCatBr 43–49), Espírito Santodo Pinhal (TgCatBr50–57), Guaíra (TgCatBr58–62),Marília (TgCatBr63,64) Osasco (TgCatBr65,66), Pirassununga (TgCatBr67–73), Ribeirão Preto (TgCatBr74–76), S.J. do Rio Peto (TgCatBr77–80), and São Paulo (TgCatBr81–84).

k São Paulo county.

Sheep