1. Introduction

‘The problem of the way Luke viewed and used the miracles of Jesus is a subject that has remained remarkably innocent of systematic treatment in recent biblical scholarship.’Footnote 1 This remark written by P. Achtemeier in 1975 has retained its validity until now.Footnote 2 Considering how many instances of miracles and supernatural events occur in the third GospelFootnote 3, the above observations must be surprising.Footnote 4 An even more neglected topic in Luke (and this is the reason why this paper dedicates more space to its elaboration) is the praise. The author of the first monograph on praise in the third Gospel, K. P. De Long stated in 2009: ‘to this point, researchers of Luke‐Acts have repeatedly noticed the motif of praise of God, and some studies have examined it in an isolated way, but no investigation has focused on praise of God in either Luke or Acts or throughout the two‐volume work’.Footnote 5 As the further analysis will show, there are numerous acts of praise in Luke that make the question even more conspicuous: how was it possible that such a prominent motif did not undergo serious scrutiny? One of the reasons is Bultmann’s definition of miracle stories.Footnote 6 The acclamations of praise do not occur only in this genre but are frequent enough to be associated with miracle stories. Bultmann has bounded three reactions: praise, fear and amazement together and called them Eindruck. In his view, it was irrelevant whether a witness gives praise or is astonished. Only one thing matters that a miracle elicited a reaction which spread Jesus’ fame. Nevertheless, a miracle is a thing causing wonder, not necessarily praise.Footnote 7 Amazement is an expected and ‘natural’ reaction to witnessing a miracle. In this perspective, every example of praise is a separate act which means that the character who gives praise acknowledges and confesses that the action is of divine origin.

Luke is the only Evangelist who combines both motifs: praise with miracles to a great extent.Footnote 8 In Mark, only one (out of four: 6.41; 11.9–10; 14.26) acts of praise in 2.12 is given after a miracle; in Matthew, four (out of ten) acts of praise (9.8; 15.31; 28.9, 17)Footnote 9 follow miracles. Luke almost always combines praise-giving with miracles: with healing, resuscitation, Jesus’ miraculous conception and birth, and his ascension. The evident difference between the third Gospel and the other Synoptics appears in the entry to Jerusalem. Luke modifies the crucial acclamation of praise in this pericope by adding an introduction so that the joyous shout of the disciples is given for all the miracles which they had seen – περὶ πασῶν ὧν εἶδον δυνάμεων (19.37). The reason for the praise in the Markan and Matthean parallels is not specified at all by the narrator: the characters just start praising. It is only in Luke that this praise is given by disciples, and only in Luke that it is foretold by Jesus (13.31) and discussed right after in 19.39–40. Moreover, it is again only in Luke that the disciples give praise after the ascension (24.52) and in the summary, which is the very last act of the third Gospel (24.53). Another important Lukan act of praise is the significant centurion’s recognition of Jesus in 23.47, which became a praise only in Luke.Footnote 10

In Luke, acts of praise occur in five miracle stories (5.17–26; 7.11–17; 13.10–17; 17.11–19; 18.35–43). The distinctive feature – the acclamation of praise – will be the subject of this article. Acts of praise occur not only in scenes that are not shared with other Synoptics but also ‘added’ to the stories that appear in the Markan material. Although the motif of praise has not yet been studied carefully in the exegesis, many scholars ascribed significant value to this topic because it marks the salvific dimension of miracle stories.Footnote 11

The main question of this article will be the consideration that the collective praise in miracle stories is given exclusively by the Jewish crowd (and it is lacking once in 17.19) and not by any other collective character. This generates an interesting question: if praise is the proper response to God’s plan, then why is the collective praise given only by the crowd and not by the disciples (or other groups, like publicans) before the entry to Jerusalem? Moreover, the crowd is the character most often named in all the miracle stories, more than the disciples and the Jewish leaders. The crowd’s responses to Jesus’ mission are narrated mainly in the miracle stories. The narrative question addressed in this paper is as follows: what is the role of the crowd in miracle stories and the reason that evokes a response of praise? Why is the communal response of praise given only by the crowd during Jesus’ public ministry?

The thesis of this article is as follows: the narrative meaning of praise miracle stories (the acronym: PMS) is to describe the progression of the Jewish crowd in understanding Jesus’ identity, i.e., from perceiving him as a miracle worker (5.26) to perceiving him as a prophet (7.16) and to seeing in him the Son of David and Messiah (18.43).

2. Miracle Stories in Luke

Jesus’ teaching and his miraculous activity are balanced in Luke, and the author gives them equal importance. Jesus’ programmatic sermon in Nazareth justifies both sides of his mission before passion – preaching 4.18–22 and the miraculous deeds 4.23–7.Footnote 12 In fact, the Nazareth scene is the perfect example of coherence between the two realities: Jesus speaks about himself, his identity, and an essential part of it is the discourse about miracles. In general terms, there is an intrinsic link between two realities: miracles are not comprehensible without teaching (i.e., without comment or explanation), and teaching without deeds would make Jesus a sort of philosopher, a mere teacher. In the subsequent narratives, AchtemeierFootnote 13 notes in his essay the redactional activity of ‘balancing’ the deeds with teaching (1). Other results of his work are as follows: 2) miracles stress the importance of Jesus; 3) they validate him; 4) incite faith; 5) are a basis for discipleship; 6) summarise in 7.18 Jesus’ mission; 7) might be the reason for his death in 13.32, 8) cause the spreading of Jesus’ fame. Furthermore, miracles punctuate the crucial moments of Jesus’ career and of the disciples: they launch the public ministry (3.21) and mark its extension beyond Jewish boundaries (7.1–17; 8.26–39; 17.11–19) and also the commissioning of disciples (5.1–11; 10.9, 17–20; 24.48–9).Footnote 14

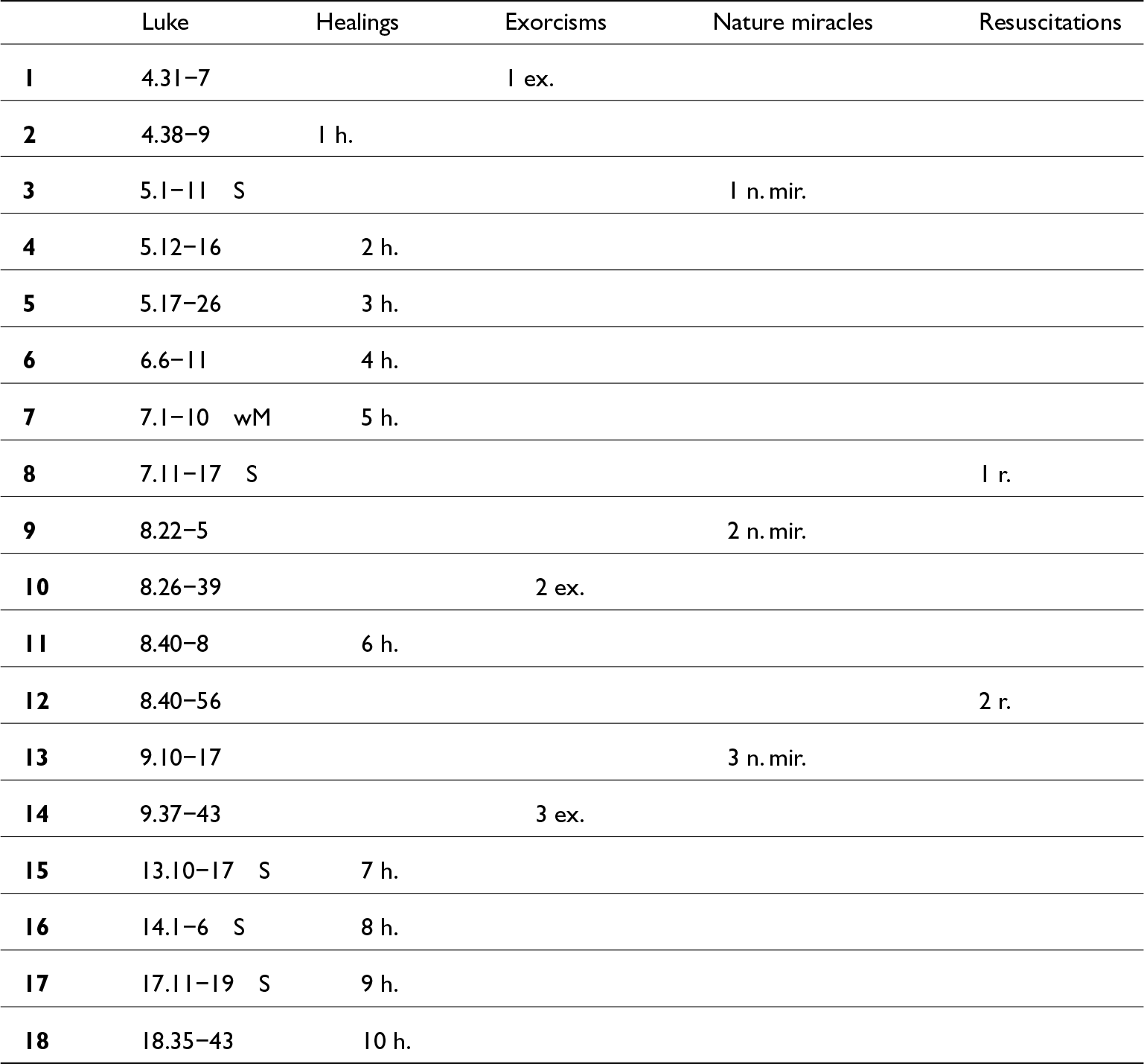

Mark’s Gospel has the largest percentage of miracle stories – twenty-five per cent. Luke’s miracle stories and Matthew’s occupy eleven per cent of the narrative. There are miracles that occur only in Mark, in material proper to Matthew, proper to Luke and in the Gospel of John. Only one healing (Luke 7.1–10) is attested in Luke and Matthew but not in Mark. Six miracle stories that occur in Mark (6.45–52; 7.24–30; 7.31–7; 8.1–10; 8.22–6; 11.12–14) are not attested in Luke. The passage called traditionally ‘great omission’ (of Mark 6.45–8.26) contains five of the six above-mentioned pericopes. The catena of miracles in Luke is the same as in Mark.Footnote 15 In sum, there are eighteen miracle stories in Luke:Footnote 16

Miracle stories occur frequently in every chapter in Luke 4–9, i.e., in the section traditionally called ‘Galilean ministry’. In the so-called ‘Travel Narrative’, miracle stories are less numerous, and three out of four appear only under Lukan pen. Ellis observes: ‘In the Galilean mission, the Lord’s acts are presented as a messianic witness. Here (in Travel Narrative), they primarily serve only as an introduction and a context for his teaching.’Footnote 17 Von der Osten-SackenFootnote 18 advances the Christological thesis that the miracles prove the messianic identity of Jesus. Busse comments that the miracles are (rather than messianic proof) to be perceived in the light of the message of God’s Kingdom.Footnote 19 Aletti sees the relationship between teaching, proclaiming the Gospel and healings.Footnote 20 According to the French exegete: ‘tipologia profetica unifica gli episodi di Lc 4–9’,Footnote 21 and of Luke 10–19 as well. The essential part of this typology is miracles, which relate to the Nazareth sermon and the commencement of the Elijah/Elisha typology. The Galilean section, Luke 4–9, is marked by many allusions to prophetic typology mainly through the miracles. Jesus is frequently accepted and recognised. In Luke 10–19, the mighty deeds are less numerous and have another meaning, according to Aletti: ‘Non è che Gesù non compia più segni in Lc 9,51–19,44, ma la loro funzione non è più di permettere il riconoscimento, bensì di provocare la discussione, e, grazie a questo, di svelare le radici profonde del rifiuto e delle resistenze.’Footnote 22

However, when all the miracle stories are scrutinised, the results differ. The first mention of the miracle (11.14) in ‘the rejection section’, Luke 9.51–19.28, is meant to provoke discussion about the source of Jesus’ power. The second one (13.11–13) provokes another Sabbath debate. The third one (14.4b) raises once more the question of the Sabbath. The fourth one (17.14) is more focused on the lack of recognition and its reasons. The fifth one (18.35–43) creates a clear exception to Aletti’s observation. Jesus is recognised because the scene ends with a communal praise acclamation. In fact, there is no reason to perceive the miracles in the Travel Narrative in a different way. Allegedly, they are ‘more messianic’ and form rather a context for the teaching in this section or serve primarily to reveal reasons of rejection, rather than to narrate the miracle itself. However, when we examine the miracle stories from both the Galilean and the Travel Narrative sections, there is no essential difference between them. The occurrence of praise miracle stories in both sections is another argument that there is no division between miracles in the Galilean Ministry and in the Travel Narrative. Above all, the miracle stories play an important role in the structure of the Lukan Gospel not only by the quantity of them but also because of association with the essential characteristics of Jesus revealed in the programmatic Nazareth sermon.

3. Praise in Luke

The Lukan author makes praise – this noble and powerful human activity – an important element of his narration. The nature of praise is more than a recognition of God and his action but is also an increase in his glory, and thus in some sense of his presence in the world.Footnote 23 Furthermore, the praise should be rooted in reality; it is imparted in connection with a salvific event, or it could have some divine attributes as its object. From this perspective, it is highly important to investigate not only which events and/or attributes of God stand behind Luke’s praise-giving, but also which character/s express praise. It also means that for Luke, all praise has to be directed to God.

Praise can be expressed in many narrative ways, among which is such a basic distinction as showing and telling. Moreover, the motif of praise is strictly correlated with joy in Luke (1.14, 28, 44, 58; 2.10; 10.21; 11.2; 13.17; 19.37; 24.52) and in other biblical books.Footnote 24 Thus, joy very frequently, depending on the context, may express praise.

The occurrence of the acts of praise in the narrative may be divided into three parts, and this threefold division of praise coincides with the common division of the Gospel of Luke:Footnote 25 1) the Infancy Narrative (Luke 1–2) is the section where praise occurs massively (in long praise speeches as well) in almost all pericopes; 2) Galilean Ministry and Travel Narrative (Luke 5–18): praise occurs virtually only in PMS (except for one acclamation by Jesus) and occurs quite regularly both at the beginning and towards the end of the section; 3) Jerusalem Section (Luke 19–24): praise given by disciples serves to bracket the beginning and end of the section; and another significant example of praise is given by the centurion just after the death on the cross.

Luke 1–2 contains the following acclamation: John the Baptist (1.41); Elisabeth’s speech (1.42–5); Mary’s speech (1.46–55); neighbours and relatives (1.58); Zechariah (1.64 and 1.68–79); angels (2.13–14); shepherds (2.20); Simeon (2.28–32); Anna (2.38).

Luke 5–18 contains less instances of praise-giving: paralytic (5.25); ‘all’, ‘the whole crowd’, ‘the whole people’ – the Jewish crowd (5.26; 7.16; 13.17; 18.43); Jesus (10.21); cured woman (13.13); Samaritan (17.15); beggar (18.43).

Luke 19–24 contains only a few examples of praise but in very significant moments of the narration: the whole of the disciples (19.37–8); centurion (23.47); disciples (24.52 and 24.53).

Luke is prolific in his use of praise of various kinds with a rich vocabulary to describe them. This acclamation occurs regularly in different parts of the Gospel: abundantly at its beginning, at its very end and in every section in between. Furthermore, the acts of praise mark the strategic moments in the narrative: Jesus’ and John’s conception and birth, the beginning and the end of public ministry, the entry to Jerusalem, the death on the cross and Jesus’ ascension.

3.1 Praise in Luke 1–2

The characteristic of the first praise section (Luke 1–2) is the insertion of long speeches that are actually praises: Benedictus, Magnificat, Nunc Dimittis and Gloria.Footnote 26 Only one other praise acclamation of the third Gospel (19.38) can be paralleled with these. The individual praise occurs more often than the collective ones. Moreover, the individual praises seem to be more crucial since almost all major figures of Luke 1–2 give praise in lengthy, significant hymns which reveal truths about Jesus and John and the salvation plan of God.Footnote 27 This observation coincides with the correlation of praise and providence in Greek literature: ‘praise (and its counterpart, petition) not only mark a person’s recognition of divine beneficence but also a person’s understanding of providence’.Footnote 28

The promise-fulfillment pattern in the Infancy narratives in Matthew and Luke differs from each other. Particularly interesting is Luke’s employment of the pattern in chapters 1 and 2. While Matthew speaks of the fulfillment of the OT promises through ‘formula quotations’ (e.g., 1:22f; 2:5-6; 2:15; 2:17), Luke responds with hymns of praise. While Matthew emphasizes an apologetic intent in proving Jesus’ messiahship, Luke instead focuses on hymns as the response to God’s act of salvation. Thus, instead of just Matthew’s promise-fulfillment, Luke has a pattern of promise-fulfillment-praise.Footnote 29

It can be specified that the reasons for praise in these instances stem from the connection that the persons of Jesus and John have in the context of God’s plan. There are miraculous conceptions of both; however, the principal miracle is that God has begun the plan of the liberation of Israel. The miraculous conceptions-births prompt praise-giving of Elisabeth, neighbours, and relatives in 1.58, and Zechariah in 1.64, 66 (because of John); of Mary in 1.46, of John in 1.41 and Elisabeth in 1.42, and of Zechariah in 1.68 (who mentions salvation in the house of David); of angels in 2.14, shepherds in 2.20, and Simeon and Anna in 2.28, 38. What is conspicuous is that the objects of praise are not John’s and Jesus’ deeds (and they might be, e.g., in 2.47 or in Luke 3) but their mere presence, and existence, which reveals God’s activity. On the other hand, the long speeches reveal more clearly than in other sections what the characters understood about Jesus and the salvation of Israel. The Jewish people are mentioned several times in this context (1.54; 1.68–9; 1.77; 2.10–11; 2.30–2).

The praise in Luke 1–2 leaves the implied reader with the following thoughts: praise is the recognition of God’s plan of salvation, expressing a proper reaction to the experience of his action; the characters reveal what is the reason for their praise, which is the realisation of God’s salvific plan. Furthermore, the Lukan pattern of promise-fulfilment-praise, present in Luke 1–2, may be extended for the rest of the Gospel.

3.2 Praise in Luke 5–18

In the ‘middle’ section, which extends between the Infancy Narrative and the entry into Jerusalem, the acclamations of praise are different from those in Luke 1–2. If we exclude the one instance of Jesus’ praise in Luke 13.21 (which does not occur in the pericope with the plot and is not a structural element for the narration), the sections can be described as follows: all instances of praise appear in miracle stories and after healings (once after a resuscitation). Though many individual praises occur, they are all somehow related to communal praises; the Jewish crowd gives praise regularly and most frequently: at the beginning of a section (scholars put the commencement of ‘Galilean ministry’ between 4.14–5.1) and towards its end (which is established between 18.35–20.1).

When the minor characters give praise (four times), this always has some connection with the Jewish crowd. In three cases, they respond in the same way as a minor character. In 17.11–19, the lack of communal praise is the point which the story wants to make. Minor characters and recipients of miracles respond mostly with praise (four times), twice with amazement, and once with fear in miracle stories. The only kind of reaction of minor characters, later shared by collective characters, spectators who are always the Jewish crowd, is praise: three times. This pattern demonstrates that the praise of individual minor characters is always related to the communal one.

The preferred verb to describe praise in PMS is δοξάζω six times, and in 17.18 the lack of praise is expressed by Jesus: δοῦναι δόξαν τῷ θεῷ; in 13.17 occurs ἔχαιρεν; in 18.43b ἔδωκεν αἶνον τῷ θεῷ. The phrase: δοξάζω τὸν θεόν seems to be a technical formula for the introduction of praise discourse and the description of praise. It occurs seven times in PMS (we include 17.18) and once more in 23.47 (in 2.20 the phrase occurs with αἰνέω).Footnote 30 The variations in the description of praise in 13.17 and 18.43 (Lukan Sondergut and addition) reveal particular redactional activity, especially when they do not contain direct speeches. The praise of minor characters is always described stereotypically and appears as one activity in the series of deeds. In three cases, the praise is described by the participle δοξάζων, which means that it is a secondary activity. Only in 13.13 does the description of praise of a woman occur in the imperfect as does the communal praise in 5.26; 7.16; and 13.17, which reinforces the impression that the action was durative. The last communal praise is expressed by an aorist in 18.43. Communal praise concludes the pericopes with the exception of 7.16, which is followed by the notice of spreading Jesus’ fame. It always follows individual praise and in two instances (5.25; 18.43) follows immediately. Furthermore, while individual praises are described by the narrator without giving the exact reason for them, there is always the cause of communal praise (also in 18.43: what they have seen – ἰδών), and it is even given in two direct discourses (5.26; 7.16).Footnote 31 The communal praise is always given by the same intradiegetic character, while the minor character disappears after giving praise. Altogether, the Jewish crowd gives praise four times, which is more than any other collective character in the Gospel: disciples do so twice, while the angels, shepherds, neighbours and relatives only once, but in none of these instances is the communal praise preceded by any individual one. In sum, communal praise is depicted far more precisely, which supports the claim that individual praise is subordinated to the more elaborate and significant communal one in Luke 5–18. The bond of individual-communal praise seems to be relevant to understanding the PMS, and this suggests that the reason for the praise of minor characters is shared by the crowd.

The connection of individual-communal praise underscores another crucial aspect of PMS: that the praise follows immediately after the miraculous acts of Jesus (with the one exception of 13.17). This instantaneity is plainer than in Luke 1–2, where praise is foretold and follows, although indirectly, the miraculous conceptions of John and Jesus but directly with some proofs/ signs. Furthermore, in Luke 1–2, God’s action is the actual object of praise, while in Luke 5–18 it is the acts of Jesus. In Luke 19–24, only the act of praise in 24.52 immediately follows the miraculous act of Jesus.

Luke 5–18 is a long section narrated in an episodic style, and the crowd in every PMS is described differently. However, there are good reasons for seeing the continuity of this character. Surely, these praises contribute greatly to the depiction of the Jewish crowd in Luke, especially in that they reveal how the crowd understands, through Jesus’ miraculous deeds, the significance of both his identity and God’s plan of salvation.

In sum, the praise in Luke 5–18 is combined with the character of the Jewish crowd, which is the only ‘element’ that unites those instances of praise. This crowd gives praise most frequently, and the communal praise is given only by the crowd (and never by any of the disciples), and all individual praises are related to communal ones. All these instances appear in miracle stories and are, obviously, strictly related to the miracles (and all eighteen Lukan miracle stories occur in chapters 4–18). Surprisingly, in Jesus’ long public ministry, the praise of the crowd dominates and occurs quite regularly, as this analysis has shown, from the beginning of this section until the end.

3.3 Praise in Luke 19–24

Almost all pericopes of the Infancy Narrative contain praise. In Luke 5–18, praise occurs quite regularly, but the section Luke 19.29–24.53 begins with a story which has the acclamations of praise in the centre (19.37–8) and ends again with praise (24.53). In Luke 24.52–3, there are actually two different praises: one just after the ascension and the second which appears in a summary (which is the only Lukan summary which describes praise) when the disciples returned to Jerusalem and gave praise for continually (which is described by the use of a periphrastic construction).Footnote 32 According to the most common division of the third GospelFootnote 33, Luke 19.29 begins the Jerusalem section, which ends in 24.53. I include in the section the passage 19.29–48 as well (as the majority of scholars), which forms an inclusion with 24.50–3.

There are more similarities between Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem and ascension than most scholars are willing to admit. In both cases, Jesus leads the way. First, he and his disciples reach Bethany, and then they go to Jerusalem and to the temple. The geography of the accounts is the same. Moreover, the attitude of the disciples is almost entirely similar (noteworthy, verse 19.37 occurs only in the Lukan version):

Only in Luke do mere disciples give praise (Mark 11.8 πολλοί; Matt 21.8 ὁ δὲ πλεῖστος ὄχλος), and this is especially striking in the case of 19.39 which gives one to understand that the crowd who are present with the Pharisees are silent: τινες τῶν Φαρισαίων ἀπὸ τοῦ ὄχλου.

This is narratively the most important praise in Luke due to:

a) the references from other pericopes: two anticipations, i.e., Jesus’ exhortation in 10.20Footnote 35 and the prolepsis in 13.35; it is discussed in 19.39–40; it is linked to 2.13–14 (other crucial praise given by angels) and also linked to 24.52–3. These affinities are reinforced by the vocabulary: αἰν-; εὐλογ- occurs after Luke 1–2 as praise only in 13.35; 19.38; and 24.53;

b) the description: the most solemn description of character in an acclamation of praise: ἅπαν τὸ πλῆθος τῶν μαθητῶν; the most detailed telling of praise – two verbs with the subject of praise χαίροντες αἰνεῖν τὸν θεόν, the manner φωνῇ μεγάλῃ, the reason (which is a summary) for praise although is followed by direct speech with other reasons περὶ πασῶν ὧν εἶδον δυνάμεων, and direct speech with the recognition of Jesus and of God’s action;

c) the context: it appears in the crucial and pre-announced moment of the entry to Jerusalem.

The third praise section does not contain PMS, but the praise of disciples is caused by some miraculous event. Furthermore, there is a crucial and redactional instance of praise of the centurion. This praise is quite particular: it should be counted as such because of the narrator’s explicit introduction to the direct speech which, however, does not contain any language of praise. Without the narrator’s voice, it would not be recognisable as an acclamation of praise. The parallel in Mark 15.39 is not introduced by the language of praise, but the content of the speech suits praise better (and Matt 27.54 as well). This relevant praise of the centurion occurs in 23.47, only the second given by a non-Jew in Luke. The first non-Jewish praise was given by the Samaritan in 17.15. Both acclamations can be considered as the signs that God’s plan of salvation embraces also Gentiles. The praise in 23.47 is a sign that this divine plan did not fail after the death on the cross.Footnote 36

The three sections of praise (Luke 1–2/4; Luke 5–18; Luke 19–24) differ significantly. The first section contains many examples of praise given by variety by both individual and communal characters. All these acclamations appear in the promise-fulfilment-praise scheme. The praise in Luke 5–18 centres around the most frequent and relevant one: the Jewish crowd’s praise to which the individual acts of praise are subordinated. The praise in the public ministry is strictly related to Jesus’ miracles. In fact, they are almost always explicitly mentioned as the reasons for the acclamations of praise. Luke 19–24 is a different section regarding the use of praise motif. The disciples are the only communal character who gives praise. Their praise appears in the first and the last scene of the section. The only individual praise is given by a non-Jew (the centurion) after Jesus’ death. The analysis of the three sections highlights the role of the Jewish crowd in the middle part (Luke 5–18).

4. Praise Miracle Stories

The meaning of all PMS and their narrative role are multidimensional. Each story has a different function and not all single PMS contribute to the main narrative plot at the same level. Considering the main task of this paper, three PMS will be analysed more carefully: the scene with the paralytic (5.17–26), Nain scene (7.11–17) and the healing in Jericho (18.35–43). In 5.26 Jesus is recognised as a miracle worker, in 7.16 as a prophet and in 18.43 as Messiah.

4.1 Praise in Luke 5.26 – Jesus Recognised as a Miracle Worker

The first PMS occurs in the initial part of Jesus’ public ministry. However, Jesus is already quite popular having accomplished two significant miracles just before 5.17–26 (i.e., a nature miracle in 5.1–11 and a healing in 5.12–16). The spreading of Jesus’ fame is extensively described in 5.15–16, which distinguishes this miracle story from all the others. The spectators from 5.17 came from every village of Galilee, Judah and from Jerusalem. All significant venues of Jesus’ activity are mentioned, which adds symbolic value to the scene.

Luke 5.17–26 is not only about the healing but also about the question of Jesus’ identity, which occupies significant space in the pericope. The Jewish leaders are involved in the controversy, but their reaction to the turning point with the miracle is not described by the narrator (as in Luke 14.6). The reaction of the group that brought the paralytic is not recounted either.

In the various moments of the plot 5.17–26, just two parties or characters are involved: Jesus with the men accompanying the paralytic in 5.18–20 and Jesus with the leaders in 5.21–4. The first moment recounts the courageous action of the group of people. The peak of the tension appears in 5.19, but Jesus does not heal the man in need and forgives his sins. All of sudden, the leaders turn from spectators into opponents of Jesus. This reaction creates the second moment in the scene: 5.21–4. Due to S. Bar-Efrat’s following observation, I suppose that ‘all’ in 5.26 describes only the Jewish crowd (this applies to 7.16 as well):

In biblical narrative the number of characters involved at any one time is very small, usually not more than two. Even when the total number of characters in a narrative is greater, only a very limited number of active characters appear in each scene (sometimes there are additional ‘silent’ characters in the background, who do not take an active part in what is happening). Since there are rarely more than two active characters in any one scene, virtually all conversations are duologues. Although in some conversations one of the participants is not an individual but a group, as in the case of Lot and the men of Sodom, for example (Gen 19.4–9), these should also be regarded as duologues, because the group of people is in fact a collective figure.Footnote 37

The above observation fits the Lukan Gospel as well. In 5.17–26, there are two duologues of such: Christ with the people accompanying the paralytic and Christ with the leaders. Usually, the act of praise of the crowd occurs at the end of the story. In 5.26, the subject of praise is described as πάντες. The narrative use of πάντες deserves closer attention. Its use was noted in scholarship as ‘characteristic’ for Luke or hyperbolic.Footnote 38 It occurs mostly in responses to Jesus’ actions (4.15; 4.20; 4.22; 4.28; 4.32; 4.36; 5.26; 7.16; 9.43a; 9.43b). Another peculiar instance of Lukan narrative style is 12.41, where Peter uses ‘all’ as a description of the crowd: πρὸς ἡμᾶς τὴν παραβολὴν ταύτην λέγεις ἢ καὶ πρὸς πάντας; The occurrences of πάντες are also surprising in 5.26; 7.16; 9.43 (final moments of pericopes) given that the crowd was described as ὄχλος in the beginning of those pericopes. Why was the term ὄχλος not chosen? The use of ‘all’ is an indication that not only the concrete gathering of people matters, but that it was a common response made by ‘all’.Footnote 39 This narrative explanation of πάντες helps to avoid the tension between the allegedly positive response of the Pharisees in 5.26 and the very negative one in 6.11. A similar tension is sidestepped in 7.16 when it seems that the disciples recognise Jesus as a prophet, and also, in 9.20 when Peter asserts in the name of others that Jesus is the Messiah. In sum, there are good reasons to think that the Pharisees and scribes do not recognise Jesus’ authority in 5.26.

Verse 25 finally narrates the activity of the paralytic. Marshall’s explanation presents the reason why his acclamation was ‘added’ by Luke: ‘Finally, Luke adds that the man praised God, a fact which could be deduced from Mark’s description of the action of the bystanders: if the spectators glorified God, how much more was the healed man likely to do so also.’Footnote 40 Both praises differ: the act of the paralytic is a concurrent action, and the praise of ‘all’ mixed with other emotions appears in direct speech.

The word παράδοξοςFootnote 41 is a hapax legomenon in the NT. The Markan version is different: Οὐδέποτε οὕτως εἴδομεν in 2.12 and Matt 9.8 stresses the power of Jesus. ‘This word is quite common in secular Gk., Philo, Joseph. and the LXX. It always denotes an “unusual event contrary to belief and expectation” (τό παρὰ δόξαν ὄν, cf. the LXX verb παραδοξάζω, “I do something unusual”).’Footnote 42 The word describes the unexpected aspect of a thing, and in this sense, is used by LXX. Two instances are comparable to Luke 5.26, but they do not follow a miracle in the strict sense (3 Mac 6.33; Wis 5.2). Hobart observes: ‘παράδοξον is used by St. Luke alone of the NT writers, and is the very word we would expect a physician to employ in reference to the healing of the paralytic; for in medical language it was used of an unusual or unexpected recovery from illness, or an unexpected death, wonderful benefit derived from a medicine’.Footnote 43 Furthermore, ‘als παράδοξα gelten solche Vorgange, die jenseits der menschlichen Erfahrung liegen (vgl. klassisch Plutarch, Mor. 305a; s. auch Phlegon Trall., Mirab, 26; ein Mann bringt ein Kind zur Welt)’Footnote 44. These observations demonstrate that the reaction of the crowd in 5.25 is understandable as a reaction to seeing the astonishing healing that may be miraculous. The term παράδοξος was so frequent that it was used to describe the genre of παραδοξογράφοι that recounts fictional and fantastic events.Footnote 45 All told, the word does not belong to a typical praise vocabulary and stresses the unexpected aspect of the healing.

The acclamation in 5.26 per se is an expression of amazement. Only the introduction to the speech makes a praise out of it. Fear and amazement can be understood as a sign of some misunderstanding, and it is fear that immediately precedes the direct speech. What is the praise in 5.26 given for? Busse explains the plural form of παράδοξα in the way that the crowd refers to both the miracle of healing and the forgiveness of sins.Footnote 46 They both are unexpected, but the plural form in the crowd’s responses refer to one deed in 9.43b; 13.17; 19.39. In my opinion, παράδοξα broaden the meaning of the acclamation: it is given for all miracles already recounted. Luke 5.26 summarises the crowd’s perception of Christ at the initial stage of his activity, and this is the last acclamation and direct speech of this character until 7.16. ‘The strange things’ are seen today, σήμερον.Footnote 47 The eschatological aspect of this term is commonly recognisedFootnote 48, and it refers not only to things seen literally ‘today’. In 13.32–3 (‘I cast out demons and perform cures today’), the word has a broader meaning. This consideration is another hint that the direct speech of the crowd in 5.26 summarises the crowd’s perception of Jesus.

The above analysis leads to the statement that the Jewish crowd did not fully understand the meaning of the miracle that they attested. The leaders ask the question: ‘Who can forgive sins, but God alone?’ but the crowd does not enter into this discussion. For them, Jesus is just a miracle worker at the beginning of his public ministry.

4.2 Praise in Luke 7.16 – Jesus Recognised as a Prophet

There are few similarities between the first and the second praise-giving performed by the crowd: the subject of praise is ‘all’, and it is the only acclamation expressed in a direct speech in the scene. The leaders, the men carrying the paralytic and the disciples, and the widow in 7.11–17 do not praise God. No reaction of the widow when she receives her son back is particularly surprisingFootnote 49.

The direct speech is immediately preceded by the mentioning of fear that seems to dominate over praise. Jesus is called a ‘great’ prophet, and that adjective appears numerous times in Luke. The word μέγας itself does not describe someone ‘more’ than prophet nor have a messianic connotation. This word is used by the angel Gabriel twice: in 1.15 when he speaks about John the Baptist, and in 1.32 when he refers to Jesus. John, however, as other characters in the Bible (like Nimrod in Gen 10.9 and Elijah in Sir 48.22) is called μέγας ‘before God’. Jesus is ‘just’ great in 1.32. Bovon presents the following opinion:

Is the use of ‘great’ (μέγας) as a title of divine sovereignty, of Hellenistic, Samaritan, or Jewish origin? And how does the term relate to the same designation of Jesus (1.32)? I understand the word in a Jewish sense. John will become great before the Lord, that is, a great prophet. Similarly, Elijah is called this in Sir 48.22, and John in Luke 7.28, under the influence of the Elijah tradition.Footnote 50

The adjective ‘great’ stresses the exalted position among prophets, and Jesus is perceived as a special prophet possibly comparable with extraordinary OT figures. Eve points out: ‘Judaism often associated miracle-working and prophets, not least the prophets Elijah and Elisha.’Footnote 51 However, the crowd rather does not allude to the eschatological prophet since there is no definite article in the speech. The crowd describes Jesus as a prophet and sees in him a special envoy of God: ‘God has visited his people’. The meaning of the word – ἐπισκέπτομαι is to make a careful inspection, look at, examine and can have a religious sense:

In the Greek OT it often denotes God’s gracious visitation of his people, bringing them deliverance of various sorts (see Exod 4.31; Ruth 1.6; Pss 80.14; 106.4). This religious sense of the verb, apparently unattested in extrabiblical Greek, renders the Hebrew pāqad. Yahweh’s visitation is associated with ‘salvation’ in Ps 106.4. (…) This use of episkeptesthai should be compared with the use of Hebrew pqd in the Qumran Damascus Document (CD 1.7–11, where God is said to have raised up a Teacher of Righteousness in a similar ‘visitation’)Footnote 52.

The above-mentioned religious meaning of the word corresponds to the theologically significant term – λαός that is the subject of ἐπισκέπτομαι. The narrator broadens in this way the sense of the passage: not only the gathering in Nain but the whole people of God are involved in the scene. This impression is reinforced by 7.17: ‘And this report concerning him went out all over Judea, and in all the surrounding district.’ The spreading of Jesus’ fame is mentioned by the narrator several times: 4.14; 4.37; 4.44; 5.15–16; 6.17; 7.17. All the above indications demonstrate that in the first phase of Jesus’ activity (until chapter 9), Luke stressed that his fame was broadly spread and that he was commonly admired and praised by ‘all’ his audience. Moreover, in this first part (until Luke 9), the responses of the crowd contain four direct speeches, which create the impression that the content of the response is more relevant than its subject. What matters is the fact that there were, with the exception of Jewish leaders, widespread positive effects of Jesus’ activity. After 7.17, the spread of Jesus’ fame is not recounted.Footnote 53 The crowd seems to refer to themselves as λαός in the direct speech; however, they are called ὄχλος by the narrator in 7.11 and ‘all’ in 7.16. This dissonance creates an impression that the people do not completely recognise Jesus’ identity because they might perceive themselves as representatives of λαός, but in the eyes of the narrator, they are just ‘all’. ‘In brief, the author allows the audience to express a not yet complete confession of faith.’Footnote 54 The acclamation in 7.16 is the only illeism coming from the mouth of the Jewish crowd.

The speech of the crowd is frequently linked to another praise speech of Zachariah. The obvious connection is created by the use of the word ἐπισκέπτομαι (1.68, 78; 7.16). There are, however, more links:

1) in both stories the gathering of the people who come to attend the religious ceremony (circumcision and funeral) are not expecting any miracle, 2) both stories concern an only son, who is not active, 3) the miracle happens in the turning point, 4) the demonstration of the miracle happens through speech (1.64; 7.15), 5) both stories end with a praise speech, 6) the fear occurs as the reaction of the crowds (1.65; 7.16), 7) in both stories the word (τὰ ῥήματα 1.65; ὁ λόγος 7.17) concerning what happened is spread in regions: ἐν ὅλῃ τῇ ὀρεινῇ τῆς Ἰουδαίας (1.65); ἐν ὅλῃ τῇ Ἰουδαίᾳ καὶ πάσῃ τῇ περιχώρῳ (7.17), 8) the verb ἐπεσκέψατο (1.68; 7.16).Footnote 55

God’s plan of salvation progresses in Luke 1 and in 7.11–17 as well, regardless of the fact that the characters do not completely understand it (as the witnesses of the miracle in 7.16) or are doubtful like Zachariah in 1.18. The crowd, however, recognises Jesus as someone through whom God acts. Calling Jesus ‘a great prophet’ is significant, ‘one should, however, not refer to this title as having anything to do with Jesus’ messianic role; there is nothing here about his anointed agency’.Footnote 56 Jesus is not confessed as the Messiah, but the crowd sees that his ministry extends to the afflicted, the poor and even to people in the grip of death. Luke 7.11–17 is another explication of Jesus’ programmatic speech in Nazareth. In Nain, Jesus demonstrated his ἐξουσία over death for the first time. The crowd, however, did not completely comprehend Jesus’ identity and perceived Jesus as a prophet. This kind of fame was spread by the numerous witnesses of the miracle throughout the whole country.

4.3 Praise in 18.43 – Jesus Recognised as Messiah

The fifth PMS appears at the end of the Travel Narrative. The pericope contains several surprising elements. The cast of the characters in the story is unexpected: the disciples and the Jewish leaders are absent, at least explicitly, which creates the impression that the encounter between Jesus and the beggar has a special meaning for the Jewish crowd, who are involved in the scene from the beginning. Furthermore, the behaviour of the blind man is particular: he tries to approach Jesus with singular determination. The ultimate expression of this attitude is the double cry Ἰησοῦ υἱὲ Δαυίδ that is the first (after the Infancy Narrative) and the last royal title bestowed on Jesus. The title has a messianic dimensionFootnote 57 and stays in contrast to the previous description of Jesus in the pericope (Ιησοῦς ὁ Ναζωραῖος in v.37). The title is unusual because it is not a flattery term to attract attention, and ‘Israel was expecting its future sovereign to bring peace but did not dream of that person accomplishing miracles. If the blind man nevertheless addressed Jesus as the Messiah, it was because he had followed his own line of reasoning.’Footnote 58 The blind man displays a great faith in Jesus as the messianic King who gives salvation. Elijah was considered an eschatological prophet who could restore sightFootnote 59, and the prophetic typology is present in 18.35–43; however, thanks to this double powerful cry of the beggar, the scene serves more to confirm Jesus’ messianic kingship than his status as a prophet.

Luke 18.43 recounts briefly the conclusion of the story. The phrase used to describe the attitude of the beggar (ἠκολούθει αὐτῷ) is the same as in 5.11 (Simon) and in 5.28 (Levi). These are only instances in Luke when an individual character starts to follow Jesus after the first encounter with him. As in the previous cases, the phrase in 18.43a rather means that the beggar becomes a disciple, even if it is the only example when following Jesus happens without a previous call to be a disciple. However, the context suggests this interpretation: the man joins the crowd of Jesus’ followers and has an exemplary faith and understanding of Jesus’ identity suitable for being a disciple.

The praise-giving of the crowd in 18.43b does not appear in the Markan and Matthean versions of the story. In Luke, it is the only example when ὁ λαός finally gives praise. As Fitzmyer states, ‘the added comment shows wherein Luke’s interest really lies, more in the reaction of the people than in the miracle itself’.Footnote 60 The miracle which confirms the recognition of Jesus’ messianic status was accomplished for the Jewish crowd. This character was involved in the scene from the beginning (v. 35) and during the development of the action in v. 36 when the beggar asks them for some time (ἐπυνθάνετο, imperfect is more than just ‘to ask’ and denotes a durative action); they speak in v. 37 (only in the Lukan version); the cry about Jesus the King was heard by the whole crowd (even προάγοντες in v. 39, those in front heard it) and afterwards, the shouting was even louder and more persistent (in v. 39 the imperfect ἔκραζεν occurs which describes a repetitive action).

For the first time in the narration, the narrator states in v. 43 that the crowd’s praise was given for what they have seen (ἰδών). The people saw and witnessed the singular determination of the beggar and his faith, which was exalted by Jesus; the cry with a messianic title and the immediate healing that results in following Jesus. The participle of the verb ὁράω has also the meaning ‘to experience, to witness, to perceive’ and refers to the event in general. This word occurs in significant pericopes in connection with the motif of praise: δοξάζοντες καὶ αἰνοῦντες τὸν θεὸν ἐπὶ πᾶσιν οἷς ἤκουσαν καὶ εἶδον in 2.20; εἴδομεν παράδοξα σήμερον in 5.26; αἰνεῖν τὸν θεὸν φωνῇ μεγάλῃ περὶ πασῶν ὧν εἶδον δυνάμεων in 19.37; ἰδὼν δὲ ὁ ἑκατοντάρχης τὸ γενόμενον ἐδόξαζεν τὸν θεόν in 23.47. The participle ἰδών appears many times in the miracle stories when a character experiences some new, surprising event or person (5.8; 5.12; 5.20; 7.13; 8.28; 8.34; 13.12; 17.14; 17.15). Luke 18.35–43 is the last miracle story in the Gospel, and the people have seen numerous miracles already. The most conspicuous and never-experienced-before element of the story in Jericho is the messianic title addressed to Jesus. Jesus does not reject the title ‘Son of David’ but confirms his royal dignity through the miracle, having seen that the crowd responds with a pure act of praise with no trace of amazement or fear as before (5.26; 7.16). The Jewish crowd sees in Jesus not only a prophet but also the messianic King.

Luke’s miracle stories always imply that Jesus has great power. However, Luke uses these stories to teach far more than this. First, the miracles will give insight into Jesus’ identity. Although Jesus does not publicly reveal his identity until the end of the Gospel, the miracles offer hints to those who have eyes to see. Jesus will be seen as one who has power over nature, demons, disease, disabilities, and even death. Jesus will display his power over Satan and his various agents, and he will on several occasions do that which only God can do, giving the onlookers a glimpse at his divine natureFootnote 61.

Jesus reveals his identity gradually through the miracle stories from the onset of his public ministry until the events in Jericho. This progressive revelation serves to teach the crowd who accompanied Jesus. The four instances of praise of the Jewish crowd demonstrate that they have finally recognised Jesus’ messianic dignity in 18.43.

4.4 Praise of the Crowd in Luke

There is a certain notable ‘development’ in the descriptions of the Jewish crowd when they give praise – what all these descriptions have in common is that the word πᾶς always occurs:

− 5.19: διὰ τὸν ὄχλον; v. 26 ἔκστασις ἔλαβεν ἅπαντας καὶ ἐδόξαζον – the crowd is described as ὄχλος at the beginning of the story but is not one of the principal characters of the scene (ὄχλος appears in accusative and stays in the background of the action of people with the paralytic); v.26 ἅπαντες occurs in accusative and is actually the subject of amazement. Moreover, the amazement in the nominative stays in the centre of the phrase,

− 7.11: ὄχλος πολύς the large crowd appears at the beginning in the nominative as one of the important figures of the story; v.16 ἔλαβεν δὲ φόβος πάντας καὶ ἐδόξαζον – again, πάντες in accusative refers primarily not to praise but to fear,

− 13.17: πᾶς ὁ ὄχλος – the whole crowd appears only at the end of the story in the nominative,

− 18.36: ὄχλος is mentioned in the genitive; v.43 πᾶς ὁ λαός – the term has the theological meaning of God’s ‘people’ in Luke.

The above descriptions diverge substantially. First, two acts of praise centre on the content of praise, that it was common and given by all. Furthermore, only these two moments of praise have direct speeches, and only these two among all the praises in Luke are combined with other emotions: 5.26 with amazement and fear and 7.16 with fear. In the case of 5.26, one could even wonder whether the direct speech is actually an expression of praise since it is preceded by the description of fear which does not occur in Mark 2.12: ‘they glorified God, and were filled with fear, saying’. Furthermore, the aspect of fear is softened in 7.16 and appears before the mentioning of praise:

5.26: καὶ ἔκστασις ἔλαβεν ἅπαντας καὶ ἐδόξαζον τὸν θεὸν καὶ ἐπλήσθησανφόβου λέγοντες ὅτι

7.16: ἔλαβεν δὲ φόβος πάντας καὶ ἐδόξαζον τὸν θεὸν λέγοντες ὅτι.

The ‘development’ consists not only in the clearer description of the character but also in the clearer description of the praise itself: in 5.26, praise is mixed with amazement and fear (in W, only fear occurs; in D, only amazement); in 7.16, with fear; in 13.17, it is described as joy; and in 18.43, there is pure praise of the λαός.

The two first praises are described by the technical formula (δοξάζω). The subject of praise differs, however: in 5.26, they are unexpected deeds seen today; in 7.16, Jesus is praised as a prophet, and God’s coming is seen in him. This praise resembles praises from Luke 1–2 mostly, not only because of the reference to Zechariah’s acclamationFootnote 62, but as it follows a similar pattern of underscoring an aspect which goes beyond what was seen: that Jesus acted as a prophet.

Two final communal praises stress the importance of the character. The last one in its allusion to 2.10–11 gives the impression that God’s plan of salvation succeeds. The crescendo of reason for praise can be observed in four steps which cannot be anything but deliberate in the development by the Evangelist:

5.26: the reason is simply an extraordinary deed just performed;

7.16: God’s plan is seen behind the miracle, but Jesus is ‘just’ a prophet;

13.17: the value of all of Jesus’ miracles is recognised but not his identity;

18.43: Jesus is recognised as Messiah.

The last two communal praises indicate clearly that the Jewish crowd gives praise: 13.17 expresses it by ὄχλος and in 18.43 by the theological term λαός. Both terms are preceded by πᾶς which makes a representative entity of them: ‘the phrase πᾶς ὁ λαός should probably be translated as by “the whole people” rather than by “all the people”’Footnote 63. The reason for praise is precisely presented in 13.17 and briefly in 18.43 (ἰδών). The praise in 13.17 is contrasted with the shame of opponents (the only example where praise occurs with a negative reaction); 18.43b follows the individual praise. All communal praises describe the ‘totality’ of this response but in slightly different ways. In the first two PMS, what matters most is that the praise was given and for what reason rather than which character is giving it.

5. Conclusion

This article has shown the peculiarity of Lukan use of the praise motif in the middle part of his Gospel (Luke 5–18), and in general. Praise is a very Lukan motif which does not occur in other Synoptic Gospels to a similar degree, and three of five PMS appear only in Luke (7.11–17; 13.10–17; 17.11–19). In two instances, Luke has also the acts of praise where other Synoptics do not: one of the healed man (Luke 5.26) and the second of the cured one in 18.42. In comparison to Mark, Luke ‘adds’ six miracle stories and three of them are PMS. Praise is the motif which occurs very often and mainly in miracle stories. Furthermore, the motif occurs only in miracle stories in Luke 5–18 except for one acclamation of Jesus (10.21). Moreover, the most frequent response that appears in the miracle stories is the acclamation of praise. The only communal character who gives praise is the Jewish crowd. Their four acclamations of praise occur regularly in the narration and dominate over the individual acts of praise. The above-mentioned observations make it clear that there is a redactional activity and certain meaning behind the motif of praise.

Another relevant conclusion is that the Jewish crowd’s praise-giving reveals the gradual recognition of Jesus’ identity. The perception of Jesus as a miracle worker and prophet (5.26; 7.16) has changed to seeing in him the Son of David and Messiah (18.38, 39, 43). The people are constantly on Jesus’ side before the entry to Jerusalem. Most of their reactions and responses occur in miracle stories. These pericopes demonstrate the consciousness of the Jewish crowd. Therefore, the miracle stories – and particularly PMS – are crucial narratives for the characterisation of this communal figure. The disciples do not play a prominent role before the entry to Jerusalem, and their primary task is to learn and witness.Footnote 64 There is a crescendo of the crowd’s praise towards 18.43 which is ‘narratively’ the most relevant praise due to the following arguments: a) the praise is described distinctively and not by stereotypical formulae (δοξάζω) but ἔδωκεν αἶνον and stands as a unique emotion (without amazement or fear); b) the subject is the theological term πᾶς ὁ λαός in the nominative; c) the most ‘accurate’ recognition of Jesus’ identity as Messiah; d) its link with 2.10. These arguments prove that the praise-giving in 18.43 depicts the last and the most important response of the Jewish crowd in the public ministry that reveals their final understanding of Jesus’ identity.

The constantly favourable attitude of the crowd to Jesus in Luke 5–18 has its narrative consequences: during the ministry in Jerusalem, the λαός is always on Jesus’ side (19.48; 20.19, 26; 21.38; 22.2)Footnote 65. Luke 19.29–22.6 is also characterised by several attempts of the leaders to kill Jesus (19.47; 20.2, 20, 27; 22.2–6) who are afraid of the popularity that Jesus has among the people. There is, however, one scene where the crowd acts together with their leaders (23.18–25). The implied reader can be surprised by this co-operation (which is stressed by the hapax legomenon: παμπληθείFootnote 66 in 23.18) because it was not pre-announced in the previous narrative at all. Until this moment, the activity of the crowd is always separated from the actions of their leaders. The presence of λαός in the scene 23.13–25 is in itself surprising. During the trials before the council and Pilate, many characters are mentioned explicitly: the elders of the people, scribes, Sanhedrin (22.66); the chief priests and the gathering who is called ὄχλος (23.4). Before Pilate (23.13) come the chief priests, members of Sanhedrin and the λαός. The unexpected change in the crowd’s attitude from praising God after Jesus’ miracle in 18.43 to shouting ‘crucify him’ in 23.21 is the peculiarity of the passion narrative. The most probable explanation for the unexpected attitude of the crowd in 23.13–25 is that they were manipulated by the archpriests. It is the only scene in Luke when the people act in concert with their leaders who ferociously try to condemn Jesus before the authorities. The crowd is dissociated from their leaders just after the trial, and they repent after the crucifixion in 23.48. This is another reason to see in the crowd’s acclamations of praise a crucial element in the characterisation of this important character.

Competing interests

The author declares none.