1. Setting the scene

The rising embrace of internationalisation in higher education has led to a global surge in demand for English-medium education (EME) programmes (e.g., Dimova et al., Reference Dimova, Hultgren and Jensen2015; Molino et al., Reference Molino, Dimova, Kling and Larsen2022). Since 2002, the increase of English in tertiary education has experienced a staggering growth (Studyportals, 2024). Most such programmes have emerged outside the traditional Big Four English-speaking countries (i.e. UK, USA, Australia, and Canada), finding footing in the European Economic Area (EEA) (43.0%) with Ireland, Germany, and the Netherlands in the lead as of June 2024 (Studyportals, 2024). In Taiwan, where I talk today, the government's initiative outlined in the ‘Blueprint for Developing Taiwan into a Bilingual Nation by 2030’ (MOE, 2017; Tsou & Shin-Mei, Reference Tsou and Shin-Mei2017) exemplifies a strategic commitment to embracing English as a language of instruction within the educational framework.

But what are we referring to when talking about EME? English-medium education (also known as English-medium instruction or EMI) describes ‘the use of the English language to teach academic subjects, other than English itself usually without an explicit focus on language learning or specific language aims’ (Dafouz & Gray, Reference Dafouz and Gray2022, p. 1). Research into EME settings has noted several reasons for this lack of explicit attention to language matters. First, there is a certain resistance to take responsibility for English language issues, as lecturers see these beyond their teaching competences and training (Kling, Reference Kling, Snow and Brinton2017); second, time-constrains in an already crammed curriculum, and, third, and most importantly, lecturers’ assumption that students’ general English proficiency is equivalent to disciplinary language knowledge (Dafouz et al., Reference Dafouz, López-Serrano and Pérez-Paredes2023). Nevertheless, this oversight in addressing language issues in many EME settings may hinder students’ ability to comprehend and produce discipline-specific texts, while raising concerns about their satisfactory learning of disciplinary content.

As we convene here in Taiwan, this keynote will first begin by foregrounding the need to provide explicit and integrative linguistic support to students and lecturers in EME by focusing on the construct of disciplinary literacies (DLs). Defined as ‘the ability to appropriately participate in the communicative practices of a discipline’ (Airey, Reference Airey2011, p. 3), DLs will be foregrounded as the building block for effective access to subject-specific engagement and communication in EME contexts. Second, I will examine the construct of DLs with the help of a conceptual and analytical framework, known under the acronym ROAD-MAPPING (Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2016, Reference Dafouz and Smit2020, Reference Dafouz and Smit2023), which analyses ‘the diversity and complexity of EME in a holistic, dynamic and integrative manner’ (Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2020, p. 31). To illustrate the explanatory power of ROAD-MAPPING and focusing on DLs, I will use data from the SHIFT research project (see Section 4). More particularly, I will draw on data from focus group interviews with students and lecturers on their views of DLs and internationalisation in a business studies programme.

With the use of the six intersecting dimensions that make up ROAD-MAPPING as referred to in this paper (see Figure 1), I will offer a situated account of how DLs are conceptualised, practised, and socialised in this EME setting and touch upon the different roles that English for Specific Purposes/English for Academic Purposes (ESP/EAP) and EME professionals play in this specific context. The plenary will close with implications for these professionals, advocating for the need to regard such agents as pivotal in supporting students and lecturers in the effective implementation of internationalised EME programmes (Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021; Dafouz & Gray, Reference Dafouz and Gray2022; Wingate, Reference Wingate2022).

2. From academic literacies to disciplinary literacies

While interest in academic literacies is not new, its theorisation, research focus, and pedagogical practices (PP) have undergone noticeable changes over time. From the Languages Across the Curriculum (LAC) movement developed in the 1970s, to Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and genre theories in Australia in the 1980s, what these approaches have in common is their interest in supporting students in their literacy development across all subject areas. With the advent of the New Literacies approach in the 1990s, the notion of academic literacies becomes socially situated (Lea & Street, Reference Lea and Street2006). This meant that literacy was no longer viewed solely as the ability to read, write, and communicate effectively but to do so in different social contexts. Thus, communication styles differ across location, class, ethnicity, gender, and discipline, to the point that literacy itself does not automatically lead to success: it is rather the knowledge, habits, and dispositions learned through literacy and matching societal expectations that are related to success. In other words, instances of literacy, as socially situated practices, can only be fully understood when the context is considered (Gee, Reference Gee2012). Thus, literacy may be better understood through an ideological model that leads to economic opportunity for members of dominant classes or races, as dictated by a society's political history, economic conditions, social structures, and local ideologies. This ideological model guides teachers to be more aware of how social literacies influence how people interact, including how teachers socialise students into a particular discipline. Through this process of socialisation, students learn not just content, but also the different methods, values, and intellectual habits that are particular to each discipline. Since we are in the field of business, methods in this discipline include, for instance, market and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analyses, and intellectual habits range from problem-solving to address business challenges to ethical considerations and corporate responsibility (America, Reference America2014).

Recent studies (Spires et al., Reference Spires, Kerkhoff, Graham, Thompson and Lee2018) suggest that literacies have been mostly theorised from linguistic perspectives rather than disciplinary ones, thus suggesting the use of the label ‘disciplinary’ instead of ‘academic’ and the plural ‘literacies’ rather than the singular ‘literacy’. Whatever term we use (see Wingate, Reference Wingate2022, for an interesting discussion of the terminology), the main message is that literacy is not a uniform or universal skill but a set of social practices that vary across different disciplines and professional fields, with each discipline having its own unique set of language practices, norms, and ways of constructing knowledge. Therefore, as students engage in their academic life, they not only learn specific communication styles (e.g. writing reports, presenting case studies, producing executive summaries) but also adopt the epistemological behaviours and identities typical of their fields (Airey, Reference Airey2011). Such knowledge-seeking practices encompass how individuals approach the process of learning, the sources of knowledge they rely on, and their beliefs about the nature of knowledge itself, depending on the disciplinary group they belong to (Clarence & McKenna, Reference Clarence and McKenna2017, p. 40). Mastering these literacies is precisely what enables students to participate in their subject-specific areas, first by effectively understanding knowledge and later by developing such knowledge further.

The approaches sketched above draw particularly on studies in education where disciplinary literacy for first language (L1) students has featured strongly. However, as stated in the introduction, in the context of EME, language teaching and learning are often incidental since lecturers and management (wrongly) assume that students’ English proficiency equates to DLs (Dafouz et al., Reference Dafouz, Hüttner, Smit, Smit, Nikula, Dafouz and Moore2016)). To support such literacy development in English, for over 60 years, EAP/ESP programmes have focused on identifying the genres, vocabulary, and communicative practices of particular disciplinary groups in English-speaking academic and professional contexts (see e.g. Hyland & Hamp-Lyons, Reference Hyland and Hamp-Lyons2002). Without going into the differences between EAP/ESP and EME, which fall beyond the scope of this paper (but see Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021), I would like to argue that DLs can be the natural meeting ground for ESP/EAP and EME professionals for several reasons (see Dafouz, Reference Dafouz and Chapelleforthcoming). First, from a pedagogical perspective, EAP/ESP professionals have solid expertise in the teaching of genres and their lexico-grammatical features. Their work is rooted in needs analysis principles and task-based learning where teachers engage students in practical, real-world tasks that mirror the genres and communicative practices they will encounter in their academic and professional lives. In contrast, EME lecturers are socialised in their disciplinary fields, where they conduct research, publish, and teach in English. Although these lecturers possess the ‘know-how’ of their discipline after years of practice, they often find it challenging to share such knowledge with students in an explicit and pedagogical manner (Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021).

Second, concerning assessment, because language development is the main target of EAP/ESP, the focus is largely on language. Student linguistic skills tailored to their disciplinary language needs are therefore evaluated. In EME, the emphasis on content usually means that language is not assessed, at least formally. Yet, according to research, student work is sometimes downgraded when language errors (usually grammatical or lexical) become too numerous or impede communication (Hultgren et al., Reference Hultgren, Owen, Shrestha, Kuteeva and Mežek2022).

Third, regarding teaching materials, EAP/ESP textbooks and resources covering a wide range of professional and academic areas, have typically been abundant and specialised; EME courses, at least initially, often lacked customised materials and relied heavily on content textbooks. These textbooks largely came from two different sources: they were either designed for English-speaking audiences with little or no linguistic scaffolding or well-known manuals on the subject written in local language and translated into English (see Ávila-López, Reference Ávila-López and Sánchez-Pérez2020; Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021, p. 25).

Finally, EME classrooms are often more heterogeneous than ESP/EAP ones with bi/multilingual and multicultural students interacting with local students, different linguistic repertoires in place, and disciplinary literacy practices constantly negotiated. Thus, to examine this new internationalised EME context and, more specifically, the nature of the DLs developed within, I now turn to the ROAD-MAPPING framework itself.

3. ROAD-MAPPING as a metalevel analytical framework

The ROAD-MAPPING framework was originally designed to overcome prior fragmented conceptualisations that examined the EME phenomenon in separate compartments and isolated language issues from other contextual variables (Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2020). Drawing on theories from sociolinguistics, ecolinguistics, and language policy and planning (Blommaert, Reference Blommaert2010; Fill, Reference Fill, Fill and Penz2018; Spolsky, Reference Spolsky2004), the framework serves as a reference when analysing particular contexts or examining different settings (Hüttner & Baker, Reference Hüttner, Baker, Dafouz and Smit2023). Moreover, ROAD-MAPPING brings with it the renaming of the context of study. Thus, instead of the EMI label, Dafouz and Smit (Reference Dafouz and Smit2016) coined the term ‘English-Medium education in Multilingual University Settings’ (EMEMUS or EME for short). EMEMUS is conceptually wider than EMI in that it is inclusive of diverse research agendas, pedagogical approaches, and different types of education. The concept, moreover, is more transparent because it refers to ‘education’, thus embracing both ‘instruction’ and ‘learning’ instead of prioritising one over the other. Additionally, EMEMUS explicitly describes the sociolinguistic setting in question, which is understood as multilingual in the widest sense (Preece & Phan, Reference Preece and Phan2016; Soler & Gallego-Balsà, Reference Soler and Gallego-Balsà2019; van der Walt, Reference van der Walt2013), be it as a reflection of top-down regulations or bottom-up practices. This, in turn, recognises that English as a medium of education goes hand in hand with other languages that form part of the multilingual landscape. Finally, with the inclusion of the term ‘universities’, the label makes clear that the focus is exclusively on the tertiary level, a level with specific characteristics: adult students voluntarily engaged in advanced learning, lecturers who are also, or mainly, researchers, and higher degrees of mobility and internationalisation.

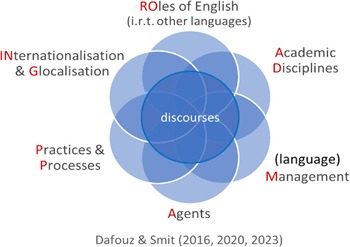

Operationally, ROAD-MAPPING contains six different core dimensions: Roles of English in relation to Other languages (RO), Academic Disciplines (AD), (language) Management (M), Agents (A), Practices and Processes (PP), and Internationalisation and Glocalisation (ING), which together form the acronym. Such dimensions are understood as equally relevant, independent but interconnected and complex. In this model, discourse is placed at the centre, ‘as the intersecting access point through which all six dimensions can be examined’ (Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2016, p. 403), reflecting the centrally discursive nature of the social practices that construct and are constructed dynamically in EMEMUS. Figure 1 offers the visual representation of the framework with the intersecting six dimensions.

Figure 1. The ROAD-MAPPING framework.

Due to space limitations, these six dimensions can only be described briefly (for a detailed description, see Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2020, pp. 40–68). I will start with the dimension of DLs, given that this is the main focus of the paper. In the ROAD-MAPPING model, DLs were labelled originally Academic Disciplines (see Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2016), which encompass two related notions: on the one hand, the diverse range of academic products (whether spoken or written) typically developed in an educational setting and conforming to socially conventionalised situated practices, and on the other, the ‘subject-specific conventions, norms and values that define different disciplinary areas’ (Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2020, p. 60). From a terminological perspective, I am aware that Academic Disciplines (ADs) and DLs are not entirely synonymous (see Wingate, Reference Wingate2022, p. 5, for an interesting discussion of the ‘unnecessary distinction’ between academic and disciplinary). Yet, at this point, I shall prioritise the use of the former term (ADs) over the latter (DLs) for pragmatic reasons, to maintain the consistency of the ROAD-MAPPING framework and its acronym. In any case, the two notions explained above are essential as a means of exploring and constructing knowledge and acculturating students into specific academic communities of practice. Having named students, I now turn to the dimension Agents, which refers to the different social players that are engaged in EMEMUS at diverse socio-political, institutional, and hierarchical levels. These actors can be conceptualised as individuals (e.g. lecturers, students, administrative staff) or as collectives (e.g. department, International Relations Office, student union). Agents may adopt different roles and identities and thus implement (or not) changes in their respective higher education institution (HEI), depending on their hierarchical status within such organisations, their professional or academic concerns or their English language proficiency. As stated earlier, students, lecturers, and their views and experiences of DLs will be the main focus of this analysis but always considering the other dimensions involved for a comprehensive analysis.

Practices and Processes (PP) include the administrative, research, and educational activities that construct and are constructed by EMEMUS realities. This dimension adopts a process-focused perspective that allows for dynamic analyses at all levels. It involves ways of thinking, that is, teacher beliefs and views, which shape the instructional approaches and the pedagogical decisions taken, as well as actual ways of doing in the classroom. In this particular study, where I am focusing today, PP addresses lecturer and student views as gathered in the focus groups.

The Internationalisation and Glocalisation (ING) dimension refers to the different forces (i.e. local and global) that operate simultaneously in most twenty-first-century HEIs. Current HEIs are transnational sites where stakeholders from different social settings, diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, and educational cultures are gaining a presence (van der Walt, Reference van der Walt2013). Equally important, nonetheless, are national and local drivers, such as the local languages used in particular HEIs and/or the educational models followed. The combination of these ‘glocal’ forces needs to be taken into consideration when examining EMEMUS, and most particularly when describing the DLs at play in such settings (Dafouz et al., Reference Dafouz, López-Serrano and Pérez-Paredes2023).

Regarding Roles of English (Ro) (in relation to Other languages), this dimension refers to the diverse communicative functions that language fulfils in HEIs, with the focus placed on English, as the main medium of education. Given the many functions English can play within the setting (ESP, EAP, English as a Foreign Language (EFL), English as a Lingua Franca (ELF)), and its often-contested relation with other languages found in the environment, this dimension acknowledges the situated complexity of English and the multilingual nature of EME contexts. In other words, it goes beyond an arguably monolingual or monocultural English-only view of practices and discipline and encourages instead multilingual practices. The last dimension to describe, (Language) Management (M) is concerned with language policy statements and documents, whether implicit or explicit, issued by governments, institutions and other actors to control and ‘manipulate the language situation’ (Spolsky, Reference Spolsky2004, p. 8). Such policies can operate at a macro, meso, and/or micro level and may often be in conflict. For example, while at the institutional level some universities may officially require a C1 level of English (CEFR) for lecturers to teach in EME programmes, this requirement may not be applied in certain faculties or departments depending on the number of certified teachers or their availability in certain subject courses. Having described the dimensions briefly, I will now refer to the research project, the dataset, and the analysis.

4. The SHIFT project

SHIFT is an international projectFootnote 2 that aims to focus on students’ views of EME, recognising them as key stakeholders in the process of internationalisation of higher education. A primary objective of SHIFT is to study in detail students’ understanding and development of DLs within the specific context of economics and business studies. The exploration of DLs in EME business settings addresses disciplinary practices and habits that students need to discover and use gradually to become full members of the target discipline, as well as the disciplinary oral and written products that such students engage with (Airey, Reference Airey2011). To meet these objectives, the project conducted a longitudinal study employing a multilevel mixed-methods research design. This type of research design integrates both qualitative and quantitative data across different levels of analysis (e.g. individual, group or organisational) to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon (Headley and Plano Clark, Reference Headley and Plano Clark2020). The project gathered a rich set of data over a four-year period, which included a student survey (Dafouz et al., Reference Dafouz, López-Serrano and Pérez-Paredes2023), student written assignments and oral presentations, as well as focus group interviews with students and lecturers.

4.1 The study setting

The setting of this study is the school of economics and business studies (EBS) in a large state-run university based in a de jure monolingual region in Spain. The school hosts 6,000 students and over 400 lecturers and offers a wide range of international programmes, generally known as ‘Bilingual degrees’ (English/Spanish) in several areas: business administration and economics, law and business, and economics and international relations. In terms of language requirements, a B2 (CEFR) official certification is the minimum required for students enrolling in these degrees, whereas lecturers are required a C1. Parallel syllabi with Spanish-medium groups are followed to ensure that the same content is covered across programmes and that assessment criteria are uniform. Regarding assignments, students are expected to complete most of their courses and exams in English (up to 85%), produce texts of very different nature and lengths (ranging from 300 to 1,000 words), and give oral case-study presentations. Moreover, the writing of the final BA dissertation, usually 10,000 words long, is also completed in English.

The rationale for choosing economics and business studies as the disciplinary fields for this analysis responds to several reasons. First, English is recognised as the dominant language in business education (Komori-Glatz, Reference Komori-Glatz2018). This linguistic dominance is reflected in the high proportion of English-medium programmes within these fields (Studyportals, 2024). Additionally, economics and business programmes attract the highest share of international students, as reported by the Komori-Glatz & Schmidt-Unterberger (Reference Komori-Glatz and Schmidt-Unterberger2018), highlighting the international mobility and demand for English proficiency among students. Furthermore, the strong competition among business schools, driven by the requirements of prestigious accreditation agencies (e.g. the European Quality Improvement System or EQUIS) needs high levels of internationalisation, with English being a crucial component.

4.2 Dataset and analysis

The dataset for this study is drawn from four focus group interviews with lecturer and student cohorts during Spring 2021. These interviews represent part of the initial data collected in the first year of the SHIFT research project and provide a foundation for the longitudinal study conducted as undergraduates progress through the programme. Regarding participants, the lecturers were selected through purposive sampling, specifically intensity sampling to gain ‘information-rich’ cases (Gray, Reference Gray2018, p. 215). These participants were chosen as disciplinary experts and had certification of C1-level English as well as a relatively high level of awareness concerning communicative effectiveness for EME. In contrast, the student participants were selected through a mixture of snowball and convenience sampling, with some volunteering to participate and others agreeing in response to an active call for participants at the end of a class. This implies some self-selection bias, but the value of having student perspectives outweighed this risk. Both lecturers and students participated based on informed consent and this resulted in four focus groups with a total of 19 participants (10 students and nine lecturers). Interviews were conducted in Spanish, as it is the L1 of both the students and lecturers (except for a Belgian lecturer based in Spain and proficient in Spanish), as well as the primary language of the interviewer. The interviews took place in the second term of the students’ first-year and lasted between one hour and one hour and thirty minutes. Due to the COVID-19 regulations in place at the time, lecturer interviews were conducted online, while students’ focus groups were onsite and after class to ensure maximum participation. Student participants were all first-year undergraduates and lecturers taught different subjects within the business studies programme (e.g. accounting, management, statistics, applied econometrics, etc.). The interview questions were loosely aligned with the key constructs of the SHIFT survey (see Dafouz et al., Reference Dafouz, López-Serrano and Pérez-Paredes2023, for a detailed account), which included questions related to the role of English in their disciplinary practices (i.e. skills, such as reading, writing, speaking and listening, note-taking, group work, etc.); the use of L1 in the development of DLs (e.g. is your L1 ever used in the classroom? If so, when? By whom? etc.), and participant views of internationalisation in EME (do you consider your course international? Are there international topics covered in your degree?).

Interviews were transcribed and imported into MAXQDA (2022). To guarantee inter-rater reliability, four members of the SHIFT project participated in the coding. Coders initially examined the same 100 turns from one interview, using the basic code structure. They then compared results to clarify and ensure consistent coding for each category. Given that the initial coding framework was based on the SHIFT student survey, this process was vital for integrating also the teachers’ perspectives accurately. Once reliability was confirmed, each coder individually coded two interviews, which were later cross-checked by another coder working on the same interviews to further ensure consistency (Loewen & Plonsky, Reference Loewen and Plonsky2016).

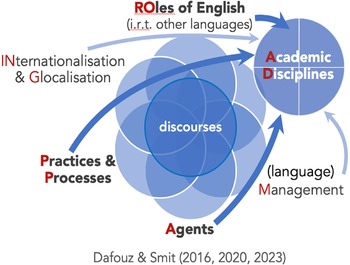

For the analysis, the six dimensions explained earlier were mainly taken as conceptual or deductive codes to be complemented by inductive, data-driven codes as part of a qualitative thematic analysis. Thematic analysis provides an interpretation of participants’ meanings, ‘acknowledge[s] the ways individuals make meaning of their experience, and, in turn, the ways the broader social context impinges on those meanings’ (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006, p. 81). It is thus ideal to identify or examine participants’ underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualisations and lends itself well to exploring tacit knowledge, as is the case of DLs. Figure 2 represents visually the influence of the ROAD-MAPPING dimensions on ADs.

Figure 2. Academic disciplines under the ROAD-MAPPING lens.

Two research questions were formulated to examine this dataset foregrounding DLs/ADs and how the different ROAD-MAPPING dimensions affect this dimension, as visually displayed in Figure 2:

• RQ1: How do lecturers and students (A) conceptualise DLs/(ADs) in the EME (ING, RoE) setting under scrutiny?

• RQ2: How are such disciplinary literacies (ADs) manifested and managed (PP, M)?

The findings for these research questions were mapped against the ROAD-MAPPING dimensions, as developed in the next section.

4.3 Findings

Following the same order as in the theoretical framework and placing DLs (or in ROAD-MAPPING terms, Academic Literacies) centre stage, I will start with the dimension of Agents and their views of such DLs from a ROAD-MAPPING lens. Despite the relatively small sample size, considerable diversity among the perspectives was found, not only between the student and teacher groups but also within the respective focus groups. The interviews indicated that students and lecturers shared a somewhat vague, tacit understanding of DLs, often referring to them with proxy terms such as text types and specialised language. Both groups perceived disciplines as being more discursively oriented (i.e., soft sciences) or numerically oriented (i.e., hard sciences), which had implications for pedagogical practice as will be described later (see PP). However, they diverged in their views of specific genres in that lecturers were more precise, citing examples like business cases, business plans, reports, press releases, and balance sheets, while students offered less precise examples such as opinion essays and oral presentations. This difference, however, might have been influenced by the novice status of the first-year students interviewed versus lecturers referring to the entire degree program (see Evans & Morrison, Reference Evans and Morrison2011, on first-year students). Additionally, lecturers and students reported differing expectations for the development of DLs. Lecturers emphasised the importance of discipline-specific terminology, conventions, and critical thinking strategies, which students often perceived as overwhelming and disconnected from their broader educational goals. Students focused primarily on subject-specific terminology, as this is generally the most noticeable feature encountered in the subject. There was also a divergence in perceptions of student support whereby students expressed a need for guidance in learning the genres and meeting disciplinary expectations, while lecturers believed that students would learn ‘by doing’ and viewed their role as content experts as excluding the responsibility to teach the discursive aspects of these genres. This tension was intensified by the observation that these skills extended beyond language with teachers noting that students lacked these competencies in both English and their first language (Spanish) (Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021; Wingate, Reference Wingate2022).

Regarding Practices and Processes (PP), the beliefs and attitudes of lecturers and students described previously transferred to the classroom setting in various ways. Lecturers’ procedural understanding of DLs meant that these were not approached explicitly in the classroom. For example, in terms of skills, both lecturers and students did not deem reading particularly complicated. Much of the reading was reported by students to consist of PowerPoint presentations accompanying lectures. These presentations typically used bullet points, graphics, and limited text and aimed to make complex ideas or data more accessible and memorable for students. Nonetheless, it is worth further investigating whether these sources of information are sufficient for truly developing DL reading skills, including the resources and bibliography used in class.

Speaking was highlighted as a skill that Undegraduates needed to develop further, as noted by both lecturers and students. Disciplinary differences in the oral mode emerged between soft and hard subjects. Thus, marketing lecturers claimed their course heavily relied on discussing and presenting case studies, requiring strong oral communication skills for negotiations, and client interactions, as well as good written communication skills for content creation, campaign documentation, and advertising. In more numerical subjects (accounting, statistics, and mathematics), speaking skills were conceptualised less precisely. Lecturers in these fields requested that students verbalise the thinking process behind calculations or problem-solving activities when revising homework or correcting exercises. Additionally, classroom English was reported to be necessary for both sets of participants to manage the classroom effectively (e.g. to give instructions, provide feedback, set up interactive activities, etc.).

Concerning writing, lecturers were generally critical of students’ overall writing abilities, both in English and their L1 (Spanish), as the quotes below portray:

T2: So [the writing task] is about how they respond to the topics and how they construct an argument, and the truth is I DO think it's a big challenge for them.

T3): … their writing is REALLY bad … I don't know if it's much worse than the students in Spanish, in the classes I teach in Spanish, but I think there is a, there is a very serious problem of writing in general amongst the students I teach.

Such difficulties were also pointed out by students, particularly when referring to the structure to be followed when writing a text, with one particular student stating he adopts the general models learned when preparing for EFL exams:

S5: I've always been prepared a lot for Cambridge exams, so … I follow the structure of the opinion essay and all the writings that exist. So I think I've internalised it, I've got used to it and it's something I do a bit intuitively.

Disciplinary differences were also said to emerge in the types of texts and genres demanded and practised by students within the business studies programme (ADs). As with the oral skills, lecturers reported that more numerical subjects usually involved short exercises or calculations, whilst, in the qualitative subjects (such as economic history, marketing, or business law), students were often required to analyse and synthesise concepts and theories. By and large, the general value of texts was deemed varied depending on the courses and the lecturers interviewed, with comments ranging from structural aspects (‘well-written and organised’) to content aspects (‘poor development of ideas’) or general formal remarks (‘written in good English’).

Turning to Internationalisation and Glocalisation (ING), this dimension is particularly important, since a true shift towards a more internationalised view of study programmes has profound implications for curricular design (see Leask, Reference Leask2015, internationalisation of the curriculum), and for pedagogical and DLs practices. Regarding the curriculum, there was a general belief amongst lecturers that ‘business is done in English’ but that the numerical subjects (e.g. accounting, statistics) are intrinsically international, or culture-free, and thus the concepts and their PP are essentially the same, irrespective of the medium of instruction (L1 or L2). In contrast, certain more culturally embedded subjects, such as Spanish tax or Spanish economic history, were viewed as difficult to internationalise by our lecturers unless a comparative or broader approach was adopted:

T2: It doesn't have to be specifically about the here and now in Spain.

T9: It was hard work but, in the end, we managed, we switched the focus from the degrees in Spanish to something wider.

Research in this area suggests that more practice-oriented courses, as is the case of business, are offered through EME and that syllabi are often designed following a topical rather than a sequential criterion (Chang, Reference Chang, Dafouz and Smit2023). These changes have led to interesting reflections on which knowledge remains in current HEIs and which knowledge disappears, linking it to the possible Englishisation or Westernisation of the higher education curriculum at large (Wilkinson and Gabriëls, Reference Wilkinson and Gabriëls2021). As for changes in the PP, the presence of international students in the classroom (A), with their own academic and educational cultures, has also raised questions about the genres, disciplinary conventions, and skills developed in their home countries. In this respect, lecturers agreed that Erasmus students generally ‘write better’ than locals but, concurrently, sometimes display more shallow content than the home students (see Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2020, p. 9).

Within the Roles of English (RO) (in relation to Other languages), lecturers agreed that English is the vehicle for content learning and thus expect students to be linguistically well-equipped to follow classes and complete assignments. As mentioned earlier, lecturers tend to equate student English proficiency with ESP/EAP skills, most particularly, subject-specific vocabulary. Further, some may adopt an ELF stance, prioritising effective communication among students from the same or diverse linguistic backgrounds rather than adhering to native-like English standards (Cogo, Reference Cogo2008). This view of function taking precedence over form is said to reflect managers’ descriptions of using language as a tool (Komori-Glatz, Reference Komori-Glatz2018), where effectiveness and efficiency in communication govern language use rather than linguistic correction (Louhiala-Salminen & Charles, Reference Louhiala-Salminen, Charles, Palmer-Silveira and Ruiz-Garrido2006). This EFL view was pointed out by one lecturer who stated that:

T5: Business is very much about negotiating, talking a lot, defending ideas, selling a product in an academic environment with an academic tone [ … ] I never stop them to correct a mistake in the middle.

As for students, while they also typically reported to share an ELF perspective, at the same time, they appreciated some attention to form, when, for instance, grammatical errors affected communication, something which many lecturers often failed to provide (PP). These discrepancies between lecturers’ and students’ views of the role of English in this setting reflect the tensions between viewing EME as an ELF context where students are seen as users of the English language (as in the professional world) or treating it as an educational setting whereby students are learners who are required to learn and use the DLs of their respective fields.

Regarding the use of languages other than English in the classroom, lecturers (A) generally reported adopting a monolingual (English-only) posture in class, and using English between 90–100% of the time. Translanguaging, thus, was not practised by lecturers nor encouraged in the classroom, although some teachers said it was sometimes present during office hours. One teacher explained that she used Spanish to clarify accounting terminology:

T4: Let's see, at a comprehension level, I give them [students] a glossary of all the important terms in English and Spanish so that they know what we are talking about, and mix them in the class.

Students (A), in contrast, viewed the pedagogical use of the first language (Spanish) – shared by most first-year undergraduates – as beneficial, though not universally. They highlighted the sporadic use of the L1 when certain content or disciplinary language was unclear and for group work. Such requests for L1 use responded to two main reasons: one academic/professional, for developing a bilingual competence to operate in both global and local settings (ING); and, one interpersonal, for integrating more easily with students from Spanish-medium programmes. Both types of uses are included in the examples below:

S11: I would also like to work in Spain because, in the end, it is my country where my family and friends are. So, if I go to work in a company and they ask me something and I don't know how to say it, well … no matter how well I know it in English … there are times when English is not the only thing I need.

S8: If I use English terms, my friends mock me … and that's horrible.

As regards language Management (M), it must be noted that this dimension was not directly addressed in the focus group interviews; however, there were some comments worth discussing. For example, both sets of participants agreed that a B2 level in English (CEFR) as an entry requirement into the EME programme was deemed insufficient to meet the DLs’ practices of the degree. Students also noted that there was no common faculty policy on how to integrate and assess English language issues in exams and assignments, with one student remarking that (S3), ‘what was encouraged in one classroom was stifled in another’. Thus, criticisms were raised on such decisions being solved at an individual level with clear differences across lecturers (A) and course subjects (ADs/DLs).

In sum, this somewhat brief analysis of the dimension of DLs through the six ROAD-MAPPING dimensions has attempted to show that this construct is multifaceted, complex, and dynamic. Thus, only by incorporating the different contextual factors that come into play simultaneously when learning, teaching, and socialising in a particular set of DLs in an EME setting and by recognising the different interactions of the ROAD-MAPPING dimensions can we truly describe DLs in a comprehensive and socially-situated manner (Dafouz et al., Reference Dafouz, López-Serrano and Pérez-Paredes2023; Gee, Reference Gee2012; Lea & Street, Reference Lea and Street2006). Moreover, beyond its analytical and explanatory power, the ROAD-MAPPING framework is also useful for the professionals involved. EAP specialists can find the framework particularly valuable as it allows them to broaden their perspective and address sociolinguistic aspects that often fall outside their typical expertise. At the same time, it offers content lecturers the opportunity to recognise the linguistic implications of EME, which are frequently underestimated or overlooked. This dual approach helps bridge the gap between linguistic awareness and content delivery in EMEMUS settings.

In the next section, I shall summarise the main contributions of this keynote and present some implications for ESP/EAP and EME professionals, arguing for the cross-fertilisation of these two areas (Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021; Galloway & Rose, Reference Galloway and Rose2022; Wingate, Reference Wingate2022).

5. Final remarks and pedagogical implications

This keynote has examined the construct of DLs in an EME setting with the use of the ROAD-MAPPING framework to examine focus group interview data. The ROAD-MAPPINGmapping model helped to map out the different contextual factors that have an impact on how DLs are viewed, practised, and taught in a particular business studies programme. On the whole, it was found that the different stakeholders interviewed, lecturers and students (A), have a limited understanding of what DLs entail. This lack of clarity influences how lecturers implicitly address DLs in their teaching and how students engage with and learn these literacies (PP). Moreover, in the case of lecturers, their conceptualisation of such DLs, even within the same disciplinary area of business studies, is quite diverse and is contingent on the subject courses they teach (whether more oracy and numeracy-oriented), which, in turn, influences the specific skills, practices, and genres requested from their students (ADs). As regards students, the first-year novice factor may have played a major role in how DLs are understood (see Evans & Morrison, Reference Evans and Morrison2011), a finding that the SHIFT project is following up by looking into longitudinal data from students in their second and third year of studies (Reference Dafouz and López-SerranoDafouz & López-Serrano, in preparation).

The perspectives on how local or international (ING) students and lecturers view their EME programme also touch upon how English (and other linguistic repertoires students bring to the classroom) are handled (RoE). Thus, more localised visions seem to encourage the development of English-only DLs whilst more internationalised ones favour bi/multilingual glossaries and exchanges amongst participants for both academic and interpersonal purposes.

Finally, the lack of an institutional language policy (M), whether at school or departmental level, that provides some common official guidelines on, for instance, how to assess English language issues in coursework and exams, ties back to the beginning of the analysis where participants (A) acknowledge an imprecise vague understanding of what DLs are. Admittedly, while DLs are much broader than language assessment, this example aims to underline that their development is partly contingent on an explicit language policy that supports language growth strategies. These strategies also impact other educational areas, such as classroom interaction, access to learning materials, and curriculum development, by offering a clear framework that integrates language and content learning within HEIs (Kuteeva & Airey, Reference Kuteeva and Airey2014). Overall, discrepancies between lecturer and student responses regarding skills, genres, and educational responsibilities reflect distinct epistemological positions as either experts or novices within their respective subject courses, as well as lecturers’ varying perceptions of the roles they should play in fostering the development of DLs, genre awareness, and critical thinking abilities.

Against this somewhat bleak backdrop, I believe that lecturers should be reminded that EME cannot be seen as a simple change in the language of instruction but rather as an opportunity for a transformative pedagogical change (Dafouz & Gray, Reference Dafouz and Gray2022). Such pedagogical changes should incorporate, as was argued throughout this keynote, the construct of DLs as a building block for the teaching and learning of effective disciplinary knowledge. Furthermore, given the internationalised nature of EME contexts, a multilingual perspective that pursues pluriliterate graduates (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Coyle, Halbach, Schuck and Ting2015) is also paramount to avoid a monolingual (English-only) bias. In this relatively new scenario, university administrators, policy developers, and curricular planners need to realise that, far from being redundant, ESP/EAP programmes are more important than ever. These programmes should be envisaged as a unique chance to seriously rethink teaching and learning strategies in EME and introduce innovation to the ESP setting in a systematic fashion (Jiang & Zhang, Reference Jiang, Zhang, Reinders, Nunan and Zou2017; Kırkgöz et al., Reference Kırkgöz, Dikilitaş, Kırkgöz and Dikilitaş2018). In fostering collaboration between EME and ESP/EAP professionals, several strategies can be suggested: for example, the development of disciplinary literacies-based curricula that integrate local and global contexts while addressing specialised language needs within disciplinary domains; second, the cultivation of genre-awareness activities for both lecturers and students, empowering learners to take ownership of their learning processes and enhance their engagement and autonomy; third, the promotion of multilingualism and translanguaging (Paulsrud et al., Reference Paulsrud, Tian and Toth2021) as reflected in materials development efforts (e.g., Breeze & Roothooft, Reference Breeze and Roothooft2021; Kuteeva et al., Reference Kuteeva, Kaufhold and Hynninen2020; Palfreyman & van der Walt, Reference Palfreyman and van der Walt2017); and, finally, the co-design of professional development programmes aiming to equip educators with the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively navigate the intersection of EME and ESP/EAP (Arnó-Macià et al., Reference Arnó-Macià, Aguilar-Pérez, Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk and Trojszczak2022; Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021; Duarte & van der Ploeg, Reference Duarte and van der Ploeg2019; Ruiz-Madrid & Fortanet-Gómez, Reference Ruiz Madrid and Fortanet-Gómez2024; Tsui, Reference Tsui, Tsou and Kao2017). All in all, I believe that these professional development programmes need to be institutionalised and such provision ‘extended to students beyond EME and ESP settings’ to include ‘disciplinary competence building in the L1’ (Dafouz, Reference Dafouz2021, p. 32). For this to happen, comprehensive measures that truly coordinate language-in-education strategies across institutional levels still need to be designed in the context studied.

It is hoped that some of the strategies and professional development initiatives suggested here can be implemented in different EME settings per their specific needs and resources, ultimately, helping to empower our stakeholder minds, which brings this paper full circle to the title of this keynote and the overall theme of the conference.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to the lecturers and students whose invaluable contributions and cooperation have been instrumental in the writing of this paper and the success of the SHIFT project. Additionally, I am deeply grateful to the organisers of the APLX; ETRA and TESPA joint conference for inviting me to give this keynote in Taipei. This has been a wonderful experience. Finally, I need to thanks the Spanish Ministry of Research and Universities for their funding and support of the project from 2020-2024 (PID2019-103862RB-100).

Emma Dafouz is a Professor of English Linguistics at Complutense University of Madrid. Her research focuses on English in educational settings, including CLIL programs and English-medium internationalised higher education. She has published extensively in international journals (Applied Linguistics, Modern Language Journal, ESP, System, etc.) and co-authored ROAD-MAPPING English-medium education in the internationalised university (2020 Palgrave-MacMillan, with Ute Smit). Her most recent publication is Researching English-medium higher education: Diverse applications and critical evaluations of the ROAD-MAPPING framework (2023, Routledge, co-edited with Ute Smit). She leads the international project SHIFT, funded by the Spanish Government, which examines the internationalisation of higher education by exploring students’ development of disciplinary literacies in English-medium business programs.