1. Introduction

Controlling water waves through interaction with specially designed structures is important in energy conversion and protection of off-shore constructions (Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Zhao, Han, Zi, Hu and Chen2024). Efficient control of wave propagation can be achieved using materials structured at the subwavelength scale which exhibit unusual properties, known as metamaterials (Walser Reference Walser2000). These materials have enabled the realization of the cloaking phenomenon, where the object becomes invisible to the incident wave regardless of the wave direction or frequency (Leonhardt Reference Leonhardt2006; Pendry, Schurig & Smith Reference Pendry, Schurig and Smith2006). To effectively render an object invisible, a cloaking device must be both omnidirectional and broadband (Choi & Howell Reference Choi and Howell2015).

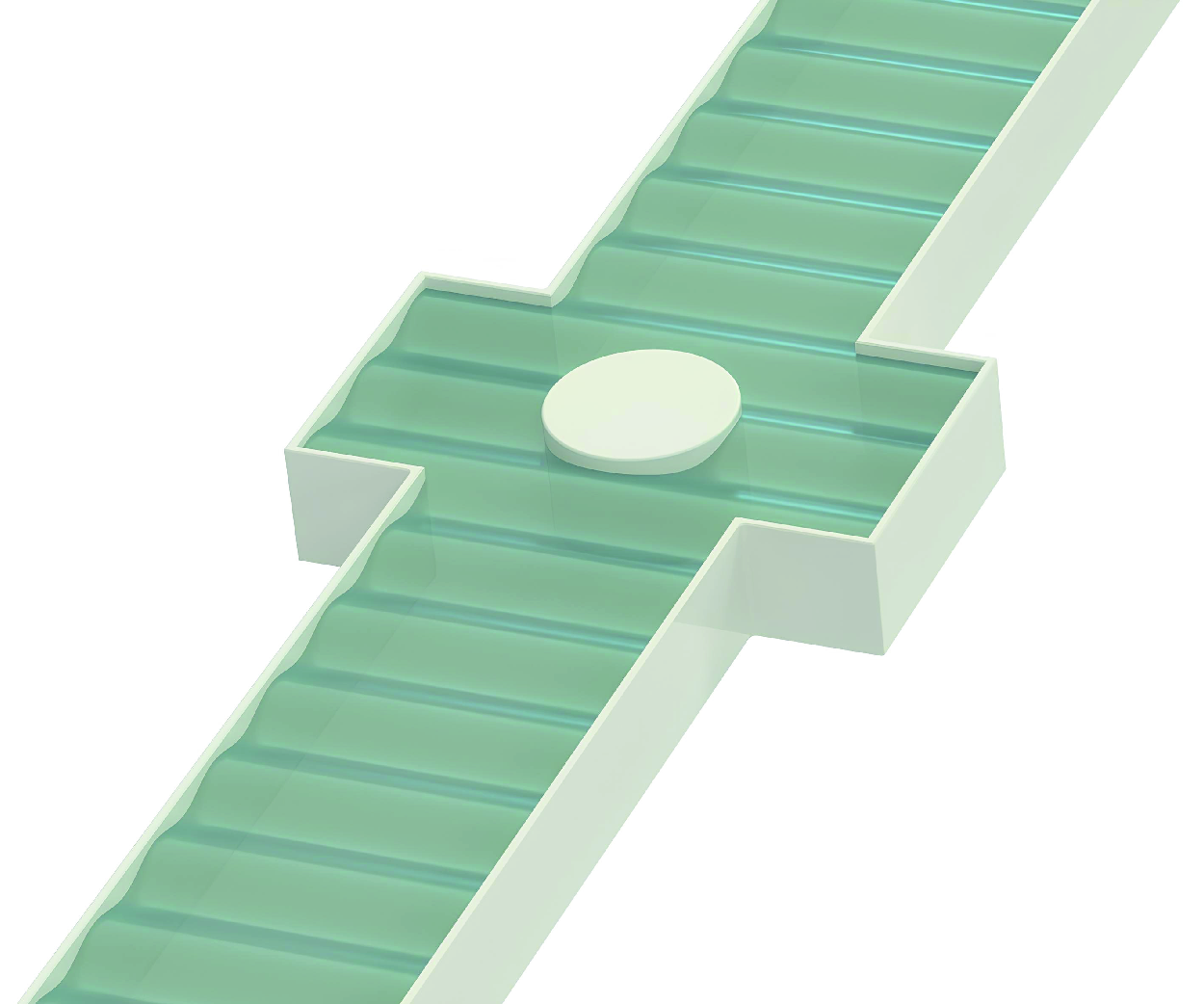

Figure 1. Water wave system. Parallel waveguide of width

![]() $L$

and cylinder of diameter

$L$

and cylinder of diameter

![]() $D$

in the plane of symmetry (

$D$

in the plane of symmetry (

![]() $Ae^{ikx}$

denotes incident wave,

$Ae^{ikx}$

denotes incident wave,

![]() $ARe^{-ikx}$

denotes reflected wave with reflection coefficient

$ARe^{-ikx}$

denotes reflected wave with reflection coefficient

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $ATe^{ikx}$

is transmitted wave with transmission coefficient

$ATe^{ikx}$

is transmitted wave with transmission coefficient

![]() $T$

).

$T$

).

The invisibility effect was initially confirmed experimentally for electromagnetic waves (Schurig et al. Reference Schurig, Mock, Justice, Cummer, Pendry, Starr and Smith2006). Thanks to the similarity of the equations governing the propagation of different types of waves, the cloaking phenomenon was achieved in the case of acoustic (Zigoneanu, Popa & Cummer Reference Zigoneanu, Popa and Cummer2014; Zaremanesh & Bahrami Reference Zaremanesh and Bahrami2022), seismic (Brûlé et al. Reference Brûlé, Javelaud, Enoch and Guenneau2014) and water waves (Porter & Newman Reference Porter and Newman2014). In the case of surface water waves, the invisibility effect can be obtained using different approaches. The first possibility is to design bathymetry around an object to be hidden (Porter & Newman Reference Porter and Newman2014; Zareei & Alam Reference Zareei and Alam2015; Bobinski et al. Reference Bobinski, Maurel, Petitjeans and Pagneux2018; Zou et al. Reference Zou, Xu, Zatianina, Li, Liang, Zhu, Zhang, Liu, Liu, Chen and Wang2019; Cen et al. Reference Cen, Liang, Cheng, Liu and Zou2024). The second method is based on the wave interaction with an array of structured objects piercing the free surface (Newman Reference Newman2014; Dupont et al. Reference Dupont, Guenneau, Kimmoun, Molin and Enoch2016; Kucher et al. Reference Kucher, Koźluk, Petitjeans, Maurel and Pagneux2023). The third method involves altering free-surface boundary conditions by surrounding an object with an elastic composite plate that floats on the surface (Iida, Zareei & Alam Reference Iida, Zareei and Alam2023).

In this work, we focus on cloaking a defect within a water waveguide system, where strong scattering is typically observed. The defect is a vertical, surface-piercing cylinder located on the centreline (figure 1). Systems with a symmetrical defect about the centreline of the waveguide with parallel walls have been extensively analysed in the context of the existence of trapped modes (Callan, Linton & Evans Reference Callan, Linton and Evans1991; Evans, Levitin & Vassiliev Reference Evans, Levitin and Vassiliev1994; Evans & Porter Reference Evans and Porter1997; Linton & McIver Reference Linton and McIver2007; Cobelli et al. Reference Cobelli, Pagneux, Maurel and Petitjeans2011). Trapped modes are localized solutions of the homogeneous wave equation with a real resonance frequency. They are characterized by finite energy rapidly decaying with the distance from the defect (Pagneux Reference Pagneux2013). The eigenvalue associated with a trapped mode is embedded in the real continuous spectrum. Our work focuses on the background scattering produced by a symmetrical obstacle within this spectrum.

Here, we present a new approach to cloak an object at a low-frequency range. We show that by manipulating the local shape of the waveguide walls, one can significantly reduce the backscattering produced by a defect inside a waveguide. We design the shape of the wall perturbation through an optimization process and quantitatively confirm its broadband cloaking properties in the experiments. Section 2 presents the modelling and optimization problem with numerical results. The experimental results are presented in § 3.

2. Modelling and numerical results

We consider a system with linear surface water waves propagating within a parallel waveguide of width

![]() $L$

characterized by a flat bottom and a surface-piercing cylinder of diameter

$L$

characterized by a flat bottom and a surface-piercing cylinder of diameter

![]() $D$

positioned at the plane of symmetry. The system is illustrated in figure 1. We assume a harmonic regime with deformation of the free surface expressed as

$D$

positioned at the plane of symmetry. The system is illustrated in figure 1. We assume a harmonic regime with deformation of the free surface expressed as

![]() $\zeta (x,y,t) = {Re}\{\eta (x,y) \cdot e^{-i\omega t}\}$

, where

$\zeta (x,y,t) = {Re}\{\eta (x,y) \cdot e^{-i\omega t}\}$

, where

![]() $\eta$

denotes the complex wavefield,

$\eta$

denotes the complex wavefield,

![]() $\omega$

is the frequency and

$\omega$

is the frequency and

![]() $Re$

denotes the real part of complex field.

$Re$

denotes the real part of complex field.

2.1. Governing equations

In the analysed case, the propagation of waves can be described by the Helmholtz equation along with the Neumann boundary condition at the rigid walls of the waveguide, at

![]() $y=\pm L/2$

, and the cylinder, at

$y=\pm L/2$

, and the cylinder, at

![]() $x^2+y^2=D^2/4$

$x^2+y^2=D^2/4$

with

![]() $k$

being a wavenumber following the linear dispersion relation

$k$

being a wavenumber following the linear dispersion relation

where

![]() $g$

represents the gravity constant,

$g$

represents the gravity constant,

![]() $\omega$

denotes frequency and

$\omega$

denotes frequency and

![]() $h$

is the water depth. We restrict our considerations to the low-frequency range

$h$

is the water depth. We restrict our considerations to the low-frequency range

![]() $kL/\pi \lt 1$

, i.e. there is only one mode propagating. The solution in the far-field region of the cylinder can be expressed as

$kL/\pi \lt 1$

, i.e. there is only one mode propagating. The solution in the far-field region of the cylinder can be expressed as

\begin{equation} \eta (x)=\begin{cases} Ae^{ikx} + ARe^{-ikx}, & \text {in the region I,}\\ ATe^{ikx}, & \text {in the region II,} \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \eta (x)=\begin{cases} Ae^{ikx} + ARe^{-ikx}, & \text {in the region I,}\\ ATe^{ikx}, & \text {in the region II,} \end{cases} \end{equation}

where

![]() $A$

denotes the amplitude of the incident wave and

$A$

denotes the amplitude of the incident wave and

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $T$

denote the reflection and transmission coefficients, respectively. Region I corresponds to the far-field region in front of the cylinder (

$T$

denote the reflection and transmission coefficients, respectively. Region I corresponds to the far-field region in front of the cylinder (

![]() $x\lt 0$

), and region II corresponds to the far-field region behind the cylinder (

$x\lt 0$

), and region II corresponds to the far-field region behind the cylinder (

![]() $x\gt 0$

).

$x\gt 0$

).

2.2. Making defect invisible – framework

We perform numerical simulations with a cylinder diameter of

![]() $D=0.6L$

in a domain

$D=0.6L$

in a domain

![]() $x\in (-5,5)L$

. We solve the Helmholtz equation (2.1) using the finite element method implemented in MATLAB PDE Toolbox. We impose the Dirichlet boundary condition

$x\in (-5,5)L$

. We solve the Helmholtz equation (2.1) using the finite element method implemented in MATLAB PDE Toolbox. We impose the Dirichlet boundary condition

![]() $\eta =1$

at

$\eta =1$

at

![]() $x=-5L$

and radiation condition

$x=-5L$

and radiation condition

![]() $\partial _x\eta =ik\eta$

at

$\partial _x\eta =ik\eta$

at

![]() $x=5L$

. The maximum edge length of the mesh element is

$x=5L$

. The maximum edge length of the mesh element is

![]() $h_{max }/L=0.01$

. It is worth noting that this problem can be solved using other methods, such as the method proposed by Kirby (Reference Kirby2008) combining a wave-based modal solution with the finite element solution. The scattering of a cylinder within a parallel waveguide can be analysed using the multipole method proposed by Linton & Evans (Reference Linton and Evans1992). We verify the results obtained using the finite element method with the multipole method for this geometry. We also consider different domain sizes and confirm that the considered domain size

$h_{max }/L=0.01$

. It is worth noting that this problem can be solved using other methods, such as the method proposed by Kirby (Reference Kirby2008) combining a wave-based modal solution with the finite element solution. The scattering of a cylinder within a parallel waveguide can be analysed using the multipole method proposed by Linton & Evans (Reference Linton and Evans1992). We verify the results obtained using the finite element method with the multipole method for this geometry. We also consider different domain sizes and confirm that the considered domain size

![]() $x\in (-5,5)L$

is sufficient to provide accurate results.

$x\in (-5,5)L$

is sufficient to provide accurate results.

Figure 2. Examples of wall modifications considered in the optimization problem with the parameters defining the shape: (a)

![]() $h_g/L= 0.16, \gamma /L = 1.6, \delta /L=1.06, N = 2$

and (b)

$h_g/L= 0.16, \gamma /L = 1.6, \delta /L=1.06, N = 2$

and (b)

![]() $h_g/L = 0.2, \gamma /L = 1.6, \delta /L = 0.29,$

$h_g/L = 0.2, \gamma /L = 1.6, \delta /L = 0.29,$

![]() $N = 60$

.

$N = 60$

.

The presence of the cylinder in the analysed scenario leads to a significant reflection of incident wave energy. In the case of a perfectly hidden object, there is no reflection (

![]() $R=0$

), resulting in perfect transmission (

$R=0$

), resulting in perfect transmission (

![]() $T=1$

). We aim to make the cylinder invisible to incident waves by creating narrow indentations

$T=1$

). We aim to make the cylinder invisible to incident waves by creating narrow indentations

![]() $F$

in the waveguide walls near the obstacle. The walls are given by

$F$

in the waveguide walls near the obstacle. The walls are given by

![]() $y=\pm (L/2+F)$

. To determine the specific shape of the wall perturbation providing broadband reduction of the reflection coefficient, we minimize the cloaking factor

$y=\pm (L/2+F)$

. To determine the specific shape of the wall perturbation providing broadband reduction of the reflection coefficient, we minimize the cloaking factor

![]() $\chi$

in the frequency range

$\chi$

in the frequency range

![]() $k\in (k_1,k_2)$

with

$k\in (k_1,k_2)$

with

![]() $k_1=0.01\pi /L$

and

$k_1=0.01\pi /L$

and

![]() $k_2=\pi /L$

. The cloaking factor is defined as

$k_2=\pi /L$

. The cloaking factor is defined as

\begin{equation} \chi = \frac {\int _{k_1}^{k_2} |R|^2{\rm d}k}{\int _{k_1}^{k_2} |R_0|^2 {\rm d}k}, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \chi = \frac {\int _{k_1}^{k_2} |R|^2{\rm d}k}{\int _{k_1}^{k_2} |R_0|^2 {\rm d}k}, \end{equation}

where

![]() $R_0$

denotes the reflection coefficient for the reference case with straight parallel walls. One has to notice that, due to energy conservation, minimizing the reflection coefficient results in the absolute value of the transmission coefficient being close to unity but does not guarantee that the phase shift in the transmitted wave is zero. As an alternative objective function, we consider minimization of the cloaking factor based on total scattered energy, which physically represents radiated power, defined in the following way:

$R_0$

denotes the reflection coefficient for the reference case with straight parallel walls. One has to notice that, due to energy conservation, minimizing the reflection coefficient results in the absolute value of the transmission coefficient being close to unity but does not guarantee that the phase shift in the transmitted wave is zero. As an alternative objective function, we consider minimization of the cloaking factor based on total scattered energy, which physically represents radiated power, defined in the following way:

\begin{equation} \chi _{sc}=\frac {\int _{k_1}^{k_2} (|R|^2+|T-1|^2){\rm d}k}{\int _{k_1}^{k_2} (|R_0|^2+|T_0-1|^2){\rm d}k} .\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \chi _{sc}=\frac {\int _{k_1}^{k_2} (|R|^2+|T-1|^2){\rm d}k}{\int _{k_1}^{k_2} (|R_0|^2+|T_0-1|^2){\rm d}k} .\end{equation}

To minimize

![]() $\chi$

and

$\chi$

and

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

, we consider wall deformations that are symmetrical with respect to the cylinder. The variability of the walls near the obstacle is achieved through the utilization of a cosine Fourier series

$\chi _{sc}$

, we consider wall deformations that are symmetrical with respect to the cylinder. The variability of the walls near the obstacle is achieved through the utilization of a cosine Fourier series

\begin{equation} F(h_g,\zeta ,n,x)= \sum _{n=1}^N \frac {2h_g}{\pi (2n-1)}\left \{ \cos \left (\frac {\zeta \pi }{\gamma } (2n-1)x \right )- \cos \left (\zeta \pi (2n-1)\right ) \right \}(-1)^{5n-1} ,\end{equation}

\begin{equation} F(h_g,\zeta ,n,x)= \sum _{n=1}^N \frac {2h_g}{\pi (2n-1)}\left \{ \cos \left (\frac {\zeta \pi }{\gamma } (2n-1)x \right )- \cos \left (\zeta \pi (2n-1)\right ) \right \}(-1)^{5n-1} ,\end{equation}

Figure 3. (a) Geometries providing cloaking phenomenon: Fourier series geometry (blue solid line,

![]() $h_g/L= 0.258, \delta /L = 1.93, \gamma /L = 0.97, N = 40$

), trapezium (green solid line,

$h_g/L= 0.258, \delta /L = 1.93, \gamma /L = 0.97, N = 40$

), trapezium (green solid line,

![]() $a/L=0.485, b/L=0.465,$

$a/L=0.485, b/L=0.465,$

![]() $h_t/L=0.26$

) and rectangular geometry (red dashed line,

$h_t/L=0.26$

) and rectangular geometry (red dashed line,

![]() $h_r/L=0.26, w_r/L=0.481$

). (b) Reflection coefficient in the considered frequency range. The inset presents the reflection coefficient for three considered geometries in a logarithmic scale to show the difference in the results.

$h_r/L=0.26, w_r/L=0.481$

). (b) Reflection coefficient in the considered frequency range. The inset presents the reflection coefficient for three considered geometries in a logarithmic scale to show the difference in the results.

In the above relation,

![]() $h_g$

denotes the depth of the groove in the channel wall,

$h_g$

denotes the depth of the groove in the channel wall,

![]() $\gamma$

represents half of the width of the variable geometry part,

$\gamma$

represents half of the width of the variable geometry part,

![]() $\delta$

denotes the width of a single groove and

$\delta$

denotes the width of a single groove and

![]() $\lfloor 2\gamma /\delta \rfloor$

denotes the floor function. We impose constraints on the parameters defining wall deformation: (i)

$\lfloor 2\gamma /\delta \rfloor$

denotes the floor function. We impose constraints on the parameters defining wall deformation: (i)

![]() $1\leq N\leq 60$

, (ii)

$1\leq N\leq 60$

, (ii)

![]() $0.09\leq h_g/L\leq 1$

, (iii)

$0.09\leq h_g/L\leq 1$

, (iii)

![]() $0.2\leq \delta /L\leq 4$

and (iv)

$0.2\leq \delta /L\leq 4$

and (iv)

![]() $0.1\leq \gamma /L\leq 2$

. The constraint

$0.1\leq \gamma /L\leq 2$

. The constraint

![]() $\delta \lt 2\gamma$

is introduced to eliminate incorrect geometries. Figure 2 depicts examples of geometries considered in the optimization problem with a graphical representation of different parameters defining the geometry of waveguide indentations. The shape of indentations given by (2.7) is initially chosen due to the lack of knowledge about the expected optimal shape. Its definition is developed to ensure that a few parameters – such as the length of the region with variable geometry, depth, number of grooves and the shape of individual grooves – could unambiguously define the geometry of the grooved region. Additionally, continuity between the variable geometry region and the section with parallel waveguide walls is maintained.

$\delta \lt 2\gamma$

is introduced to eliminate incorrect geometries. Figure 2 depicts examples of geometries considered in the optimization problem with a graphical representation of different parameters defining the geometry of waveguide indentations. The shape of indentations given by (2.7) is initially chosen due to the lack of knowledge about the expected optimal shape. Its definition is developed to ensure that a few parameters – such as the length of the region with variable geometry, depth, number of grooves and the shape of individual grooves – could unambiguously define the geometry of the grooved region. Additionally, continuity between the variable geometry region and the section with parallel waveguide walls is maintained.

The optimization process requires (i) mesh generation for a given set of parameters defining the wall shape perturbation, (ii) solving of the Helmholtz equation for the considered frequency range

![]() $kL/\pi \in (0.01,1)$

and (iii) calculation of the cloaking factor

$kL/\pi \in (0.01,1)$

and (iii) calculation of the cloaking factor

![]() $\chi$

. Given the lack of precise knowledge regarding the function

$\chi$

. Given the lack of precise knowledge regarding the function

![]() $\chi (F)$

and the absence of analytical or derivative information, we employ a black box approach (Audet & Hare Reference Audet and Hare2018). Considering the high computational cost of objective function evaluation, we use a surrogate-based method with a radial basis function approximation (Gutmann & Gutmann Reference Gutmann and Gutmann2001; Vu et al. Reference Vu, D’Ambrosio, Hamadi and Liberti2016). The initial guess is evaluated at 63 random points in the parametric space within the constrained values.

$\chi (F)$

and the absence of analytical or derivative information, we employ a black box approach (Audet & Hare Reference Audet and Hare2018). Considering the high computational cost of objective function evaluation, we use a surrogate-based method with a radial basis function approximation (Gutmann & Gutmann Reference Gutmann and Gutmann2001; Vu et al. Reference Vu, D’Ambrosio, Hamadi and Liberti2016). The initial guess is evaluated at 63 random points in the parametric space within the constrained values.

2.3. Numerical results

Minimizing the cloaking factor

![]() $\chi$

results in the geometry depicted in figure 3(a) by solid blue line (denoted as Fourier) with

$\chi$

results in the geometry depicted in figure 3(a) by solid blue line (denoted as Fourier) with

![]() $\chi =5.44\times 10^{-5}$

. The optimized shape resembles a trapezium, so we verify if we can simplify the indentation geometry and keep a similar objective function value. Geometry simplification is beneficial considering the manufacturing aspects of the experimental counterpart. Therefore, we repeat the optimization process, but this time, we vary the geometry by changing the height

$\chi =5.44\times 10^{-5}$

. The optimized shape resembles a trapezium, so we verify if we can simplify the indentation geometry and keep a similar objective function value. Geometry simplification is beneficial considering the manufacturing aspects of the experimental counterpart. Therefore, we repeat the optimization process, but this time, we vary the geometry by changing the height

![]() $h_t$

and half of the lengths of both bases of an indentation

$h_t$

and half of the lengths of both bases of an indentation

![]() $a$

and

$a$

and

![]() $b$

. As a result we obtain

$b$

. As a result we obtain

![]() $\chi = 1.96 \cdot 10^{-4}$

for

$\chi = 1.96 \cdot 10^{-4}$

for

![]() $a/L=0.485$

,

$a/L=0.485$

,

![]() $b/L=0.465$

and

$b/L=0.465$

and

![]() $h_t/L=0.26$

(figure 3

a green solid line). The optimized trapezium has almost the same length of bases, so we go one step further with simplification, i.e. we perform optimization for a rectangular wall modification. We vary the height

$h_t/L=0.26$

(figure 3

a green solid line). The optimized trapezium has almost the same length of bases, so we go one step further with simplification, i.e. we perform optimization for a rectangular wall modification. We vary the height

![]() $h_r$

and the half of the width

$h_r$

and the half of the width

![]() $w_r$

of the indentation. The best result is obtained for

$w_r$

of the indentation. The best result is obtained for

![]() $h_r/L=0.26$

and

$h_r/L=0.26$

and

![]() $w_r/L=0.481$

with

$w_r/L=0.481$

with

![]() $\chi = 1.77\cdot 10^{-4}$

(figure 3

a, red dashed line). The efficiency of the rectangular geometry is shown in figure 4, where we present wave fields for

$\chi = 1.77\cdot 10^{-4}$

(figure 3

a, red dashed line). The efficiency of the rectangular geometry is shown in figure 4, where we present wave fields for

![]() $kL/\pi =0.8253$

obtained for the reference case (parallel waveguide) and the waveguide with rectangular indentations. The comparison of the reflection coefficient in the considered frequency range for three considered wall modifications and the reference case is presented in figure 3(b), where a significant backscattering reduction is visible. The local minima of the reflection coefficient correspond to the resonant frequencies of a given system. In the case of rectangular indentations, they are observed for

$kL/\pi =0.8253$

obtained for the reference case (parallel waveguide) and the waveguide with rectangular indentations. The comparison of the reflection coefficient in the considered frequency range for three considered wall modifications and the reference case is presented in figure 3(b), where a significant backscattering reduction is visible. The local minima of the reflection coefficient correspond to the resonant frequencies of a given system. In the case of rectangular indentations, they are observed for

![]() $kL/\pi \approx 0.5$

and

$kL/\pi \approx 0.5$

and

![]() $kL/\pi \approx 0.9$

.

$kL/\pi \approx 0.9$

.

We perform the same analysis in the case of cloaking factor

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

(2.6) for three different geometries of the indentations, i.e. Fourier, trapezium and rectangular. The minimum value of

$\chi _{sc}$

(2.6) for three different geometries of the indentations, i.e. Fourier, trapezium and rectangular. The minimum value of

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

is obtained for the geometry defined through the Fourier series (2.7) with

$\chi _{sc}$

is obtained for the geometry defined through the Fourier series (2.7) with

![]() $\chi _{sc}=0.239$

. In the trapezium case, we obtain

$\chi _{sc}=0.239$

. In the trapezium case, we obtain

![]() $\chi _{sc}=0.24$

and for the rectangle

$\chi _{sc}=0.24$

and for the rectangle

![]() $\chi _{sc}=0.319$

. Optimization of the cloaking factor based on total scattered energy provides slightly better results compared with optimization of

$\chi _{sc}=0.319$

. Optimization of the cloaking factor based on total scattered energy provides slightly better results compared with optimization of

![]() $\chi$

in terms of the phase difference (

$\chi$

in terms of the phase difference (

![]() $\Delta \varphi =\arg T$

), where the phase shift is below

$\Delta \varphi =\arg T$

), where the phase shift is below

![]() $0.15\pi$

. The optimization of

$0.15\pi$

. The optimization of

![]() $\chi$

results in a phase shift below

$\chi$

results in a phase shift below

![]() $\Delta \varphi \approx 0.25\pi$

in the considered frequency range. Unfortunately, in the case of minimizing

$\Delta \varphi \approx 0.25\pi$

in the considered frequency range. Unfortunately, in the case of minimizing

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

, the backscattered energy is much higher (see Appendix A for details), so we decided to perform experiments with the geometry provided by the minimization of

$\chi _{sc}$

, the backscattered energy is much higher (see Appendix A for details), so we decided to perform experiments with the geometry provided by the minimization of

![]() $\chi$

.

$\chi$

.

The presented results are based on the initial choice of the function

![]() $F$

, given by (2.7), which defines the shape of the indentations. It is worth noting that other choices of

$F$

, given by (2.7), which defines the shape of the indentations. It is worth noting that other choices of

![]() $F$

might yield even better results with respect to the cloaking factors

$F$

might yield even better results with respect to the cloaking factors

![]() $\chi$

and

$\chi$

and

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

.

$\chi _{sc}$

.

Figure 4. Numerical simulation. Real part of the wave fields for

![]() $kL/\pi =0.8253$

: (a) for a waveguide with parallel walls (reference case) and (b) with rectangular indentations. Wave fields are normalized by the incident wave amplitude.

$kL/\pi =0.8253$

: (a) for a waveguide with parallel walls (reference case) and (b) with rectangular indentations. Wave fields are normalized by the incident wave amplitude.

2.3.1. Wave drift force

For surface water waves, a cloaking device modifies not only scattered field but also the forces acting on an object. Cloaking an object should significantly reduce the force incident waves exert on the body. The force acting on a fixed body can be determined by integrating the pressure on the body’s surface

with

![]() $\Phi$

being the velocity potential. We can decompose

$\Phi$

being the velocity potential. We can decompose

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}(t)$

into a sum of first-order and second-order components. The second-order term has a fluctuating part at frequency

$\boldsymbol{F}(t)$

into a sum of first-order and second-order components. The second-order term has a fluctuating part at frequency

![]() $2\omega$

and a time-independent wave drift force

$2\omega$

and a time-independent wave drift force

![]() $\overline {\boldsymbol{F}^{(2)}}$

, which can be expressed as

$\overline {\boldsymbol{F}^{(2)}}$

, which can be expressed as

where

![]() $S$

is the wetted body’s surface,

$S$

is the wetted body’s surface,

![]() $\boldsymbol{n}_s$

denotes the unit normal vector and

$\boldsymbol{n}_s$

denotes the unit normal vector and

![]() ${\rm d} \ell$

represents an infinitesimal segment along the water contour at

${\rm d} \ell$

represents an infinitesimal segment along the water contour at

![]() $z=0$

(Dupont et al. Reference Dupont, Guenneau, Kimmoun, Molin and Enoch2016). The first-order surface elevation is denoted as

$z=0$

(Dupont et al. Reference Dupont, Guenneau, Kimmoun, Molin and Enoch2016). The first-order surface elevation is denoted as

![]() $\eta ^{(1)}(x,y,t) = \textrm {Re}\{\eta (x,y)\cdot e^{-i \omega t} \}$

and

$\eta ^{(1)}(x,y,t) = \textrm {Re}\{\eta (x,y)\cdot e^{-i \omega t} \}$

and

![]() $\Phi ^{(1)} =\Phi ^{(1)}(x,y,z,t)$

denotes the first-order velocity potential expressed as

$\Phi ^{(1)} =\Phi ^{(1)}(x,y,z,t)$

denotes the first-order velocity potential expressed as

We evaluate the mean drift force acting on the cylinder in the presence of waveguide wall indentations providing invisibility and compare the results with the reference geometry. We analyse the influence of rectangular indentations provided by the minimization of the cloaking factor

![]() $\chi$

. The results concerning the horizontal component of the drift force are presented for the two cases in figure 5(a). The black and red solid lines correspond to the force acting on a cylinder in a parallel waveguide (

$\chi$

. The results concerning the horizontal component of the drift force are presented for the two cases in figure 5(a). The black and red solid lines correspond to the force acting on a cylinder in a parallel waveguide (

![]() $\overline {F_X^R}$

) and with rectangular indentations in the waveguide walls (

$\overline {F_X^R}$

) and with rectangular indentations in the waveguide walls (

![]() $\overline {F_X^C}$

), respectively. Implementing our cloaking device significantly reduces the horizontal force acting on the surface-piercing cylinder in the entire considered frequency range, with the maximum force being less than

$\overline {F_X^C}$

), respectively. Implementing our cloaking device significantly reduces the horizontal force acting on the surface-piercing cylinder in the entire considered frequency range, with the maximum force being less than

![]() $2\%$

of the force in the reference case (see figure 5

b).

$2\%$

of the force in the reference case (see figure 5

b).

Figure 5. The mean drift force as a function of frequency

![]() $kL/\pi$

: (a) the distribution of the mean horizontal force acting on the cylinder for the reference case and the cloaked case, respectively; (b) the ratio of the mean horizontal forces

$kL/\pi$

: (a) the distribution of the mean horizontal force acting on the cylinder for the reference case and the cloaked case, respectively; (b) the ratio of the mean horizontal forces

![]() $\overline {F_x^C}/\overline {F_x^R}$

, where

$\overline {F_x^C}/\overline {F_x^R}$

, where

![]() $\overline {F_x^C}$

represents force for the cloaked case and

$\overline {F_x^C}$

represents force for the cloaked case and

![]() $\overline {F_x^R}$

refers to the reference case with parallel walls.

$\overline {F_x^R}$

refers to the reference case with parallel walls.

2.3.2. Limitations of the cloaking device

Any passive cloaking device designed to achieve invisibility within a specific frequency range does so at the cost of increased scattering outside this range (Monticone & Alù Reference Monticone and Alù2016). Our study focuses on optimizing waveguide wall indentations to reduce backscattering within the frequency range

![]() $ kL/\pi \in (0.01,1)$

. To evaluate the performance of this system, we analyse its scattering behaviour outside the optimized frequency band, specifically in the range

$ kL/\pi \in (0.01,1)$

. To evaluate the performance of this system, we analyse its scattering behaviour outside the optimized frequency band, specifically in the range

![]() $ kL/\pi \in (1,2)$

. Figure 6 compares the reflection coefficients of a cylinder in a waveguide with straight parallel walls (reference case, black solid line) and a cloaking geometry featuring rectangular wall indentations (red line). In the reference case, the reflection coefficient decreases initially, reaching resonance at

$ kL/\pi \in (1,2)$

. Figure 6 compares the reflection coefficients of a cylinder in a waveguide with straight parallel walls (reference case, black solid line) and a cloaking geometry featuring rectangular wall indentations (red line). In the reference case, the reflection coefficient decreases initially, reaching resonance at

![]() $kL/\pi =1.63$

, before increasing with frequency. For the cloaking geometry, the reflection coefficient is significantly reduced up to

$kL/\pi =1.63$

, before increasing with frequency. For the cloaking geometry, the reflection coefficient is significantly reduced up to

![]() $kL/\pi =1.57$

. Beyond this frequency, however, the reflection coefficient rises sharply, exceeding that of the reference case.

$kL/\pi =1.57$

. Beyond this frequency, however, the reflection coefficient rises sharply, exceeding that of the reference case.

Extending the frequency range over which a cloaking device effectively minimizes scattering is a possibility that requires further investigation. Achieving a broader cloaking bandwidth would likely come at the cost of an increased cloaking factor

![]() $\chi$

(Monticone & Alù Reference Monticone and Alù2016).

$\chi$

(Monticone & Alù Reference Monticone and Alù2016).

Our cloaking device, consisting of indentations in the waveguide walls, is obtained through an optimization procedure based on the model of linear water waves. It is, therefore, important to consider the potential response of this system to nonlinear waves. In the weakly nonlinear regime, neglecting the forcing by the fundamental frequency (

![]() $\omega$

), the harmonics satisfy the Helmholtz equations (Belibassakis & Athanassoulis Reference Belibassakis and Athanassoulis2011)

$\omega$

), the harmonics satisfy the Helmholtz equations (Belibassakis & Athanassoulis Reference Belibassakis and Athanassoulis2011)

where

![]() $k_n$

is associated with

$k_n$

is associated with

![]() $n\omega$

, i.e.

$n\omega$

, i.e.

![]() $D(n\omega ,k_n)=0$

, where

$D(n\omega ,k_n)=0$

, where

![]() $D(\omega ,k)=\omega ^2-gk\tanh (kh)$

denotes the water wave dispersion relation. A harmonic that satisfies (2.12) is called a free wave, whereas a non-dispersive term, with a wavenumber

$D(\omega ,k)=\omega ^2-gk\tanh (kh)$

denotes the water wave dispersion relation. A harmonic that satisfies (2.12) is called a free wave, whereas a non-dispersive term, with a wavenumber

![]() $nk_1$

, being slaved to fundamental frequency is called a bound wave (Monsalve et al. Reference Monsalve, Maurel, Pagneux and Petitjeans2022). For a cloaking geometry and waves with a fundamental frequency

$nk_1$

, being slaved to fundamental frequency is called a bound wave (Monsalve et al. Reference Monsalve, Maurel, Pagneux and Petitjeans2022). For a cloaking geometry and waves with a fundamental frequency

![]() $\omega$

such that associated

$\omega$

such that associated

![]() $k$

is in the range

$k$

is in the range

![]() $kL/\pi \in (0,1)$

, the first-order reflection coefficient is very low. Based on the results presented in figure 6, we expect that backscattering of the free wave component

$kL/\pi \in (0,1)$

, the first-order reflection coefficient is very low. Based on the results presented in figure 6, we expect that backscattering of the free wave component

![]() $k_2$

(associated with

$k_2$

(associated with

![]() $2\omega$

) will also be low for

$2\omega$

) will also be low for

![]() $k_2L/\pi \lt 1.57$

with the cloaking geometry, but for

$k_2L/\pi \lt 1.57$

with the cloaking geometry, but for

![]() $k_2L/\pi \gt 1.57$

the reflection of this component would significantly increase. Given that the energy content of the fundamental frequency typically dominates the total energy, our cloaking device is expected to perform very well even for nonlinear waves within the considered frequency band. Nevertheless, the increased scattering of harmonic components outside this band highlights a limitation that could be addressed in future designs.

$k_2L/\pi \gt 1.57$

the reflection of this component would significantly increase. Given that the energy content of the fundamental frequency typically dominates the total energy, our cloaking device is expected to perform very well even for nonlinear waves within the considered frequency band. Nevertheless, the increased scattering of harmonic components outside this band highlights a limitation that could be addressed in future designs.

Figure 6. Reflection coefficient as a function of frequency for a cylinder in the waveguide with straight parallel walls (reference case) and cloaked case (with rectangular indentations).

3. Experimental realization

Figure 7 illustrates a scheme of the employed measurement set-up, which consists of (i) a channel guiding surface water waves of total length

![]() $2.81\, \rm m$

, (ii) a wavemaker with a digitally controlled LinMot linear motor, (iii) a cylindrical obstacle, (iv) an absorbing beach minimizing spurious reflection from the end of the channel, (v) a light source and (vi) two cameras (BASLER ACA 2040-120um and BASLER ACA 1920-40um) allowing registration of a dot pattern placed in front and behind the cylinder. The average signal-to-noise ratio values, calculated based on (Gonzalez & Woods Reference Gonzalez and Woods2008) for these cameras, are 37.49 and 41.21 dB, respectively. The still water level

$2.81\, \rm m$

, (ii) a wavemaker with a digitally controlled LinMot linear motor, (iii) a cylindrical obstacle, (iv) an absorbing beach minimizing spurious reflection from the end of the channel, (v) a light source and (vi) two cameras (BASLER ACA 2040-120um and BASLER ACA 1920-40um) allowing registration of a dot pattern placed in front and behind the cylinder. The average signal-to-noise ratio values, calculated based on (Gonzalez & Woods Reference Gonzalez and Woods2008) for these cameras, are 37.49 and 41.21 dB, respectively. The still water level

![]() $h$

is

$h$

is

![]() $0.02 \pm 5 \times 10^{-4}\, \rm m$

, the waveguide width is

$0.02 \pm 5 \times 10^{-4}\, \rm m$

, the waveguide width is

![]() $L = 0.16\, \rm m$

and the obstacle diameter

$L = 0.16\, \rm m$

and the obstacle diameter

![]() $D = 0.6L = 0.096\, \rm m$

. We analyse two waveguide geometries. The first one is a reference case with straight parallel walls. The second waveguide contains rectangular wall indentations (

$D = 0.6L = 0.096\, \rm m$

. We analyse two waveguide geometries. The first one is a reference case with straight parallel walls. The second waveguide contains rectangular wall indentations (

![]() $h_r=0.042\, \rm m$

,

$h_r=0.042\, \rm m$

,

![]() $w_r=0.077\, \rm m$

). We generate surface waves employing a LinMot linear motor in the frequency range of

$w_r=0.077\, \rm m$

). We generate surface waves employing a LinMot linear motor in the frequency range of

![]() $0.65\, \rm Hz$

to

$0.65\, \rm Hz$

to

![]() $1.36\, \rm Hz$

corresponding to

$1.36\, \rm Hz$

corresponding to

![]() $kL/\pi \in (0.53,0.97)$

. We conduct measurements for a duration corresponding to 20 time periods of oscillation.

$kL/\pi \in (0.53,0.97)$

. We conduct measurements for a duration corresponding to 20 time periods of oscillation.

Figure 7. Experimental set-up consists of (i) a channel of length

![]() $2.81$

m, (ii) a wavemaker – a cylindrical surface mounted to a linear motor, (iii) a cylindrical obstacle, (iv) an absorbing beach reducing reflection from the end of the channel, (v) a light source and (vi) two cameras (BASLER ACA 2040-120um and BASLER ACA 1920-40um).

$2.81$

m, (ii) a wavemaker – a cylindrical surface mounted to a linear motor, (iii) a cylindrical obstacle, (iv) an absorbing beach reducing reflection from the end of the channel, (v) a light source and (vi) two cameras (BASLER ACA 2040-120um and BASLER ACA 1920-40um).

3.1. Measurement method

We perform the measurements using a combination of the optical flow (OF) technique (Farnebäck Reference Farnebäck2003) and the synthetic schlieren (SS) technique (Moisy, Rabaud & Salsac Reference Moisy, Rabaud and Salsac2009). The OF method enables the extraction of displacements from a reference image (e.g., dots), whereas the SS method transforms these displacements into deformations of the free water surface (Bheeroo & Mandel Reference Bheeroo and Mandel2023). The SS method assumes certain geometrical approximations and, as a result, has a few limitations (Metzmacher et al. Reference Metzmacher, Lagubeau, Poty and Vandewalle2022): (i) weak amplitudes, (ii) weak slopes and (iii) weak paraxial angles. The distance between our cameras and the dot pattern placed on the bottom of the channel is

![]() $2.39\, \rm m$

, resulting in a maximum parallax angle of

$2.39\, \rm m$

, resulting in a maximum parallax angle of

![]() $\beta _{max}=0.22$

. In the considered frequency range, the amplitude of the generated waves is in the range of

$\beta _{max}=0.22$

. In the considered frequency range, the amplitude of the generated waves is in the range of

![]() $A\in (0.39,0.94)\, \rm mm$

with the corresponding wave steepness in the range of

$A\in (0.39,0.94)\, \rm mm$

with the corresponding wave steepness in the range of

![]() $kA\in (4.76 \times 10^{-3},13.85\times 10^{-3})$

. The error in free-surface deformation reconstructions can be estimated as (Moisy et al. Reference Moisy, Rabaud and Salsac2009)

$kA\in (4.76 \times 10^{-3},13.85\times 10^{-3})$

. The error in free-surface deformation reconstructions can be estimated as (Moisy et al. Reference Moisy, Rabaud and Salsac2009)

with

![]() $\epsilon$

being relative Gaussian noise,

$\epsilon$

being relative Gaussian noise,

![]() $\lambda$

being wavelength and

$\lambda$

being wavelength and

![]() $\eta _{{rms}}=A/\sqrt {2}$

for a sinusoidal wave, where

$\eta _{{rms}}=A/\sqrt {2}$

for a sinusoidal wave, where

![]() $rms$

is the root-mean-square. In our system, the error for the first camera is in the range

$rms$

is the root-mean-square. In our system, the error for the first camera is in the range

![]() $0.07\times 10^{-3}$

to

$0.07\times 10^{-3}$

to

![]() $0.23\times 10^{-3}$

, while for the second camera, the error ranges from

$0.23\times 10^{-3}$

, while for the second camera, the error ranges from

![]() $0.08 \times 10^{-3}$

to

$0.08 \times 10^{-3}$

to

![]() $0.26\times 10^{-3}$

.

$0.26\times 10^{-3}$

.

3.2. Experimental results

Based on the obtained temporal evolution of the free-surface deformations, we extract wave fields using the Fourier transform in the time domain

with

![]() $\omega$

being the fundamental frequency with

$\omega$

being the fundamental frequency with

![]() $T_p=2\pi /\omega$

. An example of a wave field

$T_p=2\pi /\omega$

. An example of a wave field

![]() ${Re}(\hat { \eta }_1(x,y) )$

is shown in figure 8 where, for the reference case (figure 8

a,c), strong reflection is observed in front of the cylinder and a decrease in the wave amplitude behind the obstacle. The corresponding wave fields obtained in the case of the rectangular cloaking geometry are presented in figure 8(b,d). Based on wave field

${Re}(\hat { \eta }_1(x,y) )$

is shown in figure 8 where, for the reference case (figure 8

a,c), strong reflection is observed in front of the cylinder and a decrease in the wave amplitude behind the obstacle. The corresponding wave fields obtained in the case of the rectangular cloaking geometry are presented in figure 8(b,d). Based on wave field

![]() $\hat {\eta }_n(x,y)$

, we extract transverse modes by projecting it onto

$\hat {\eta }_n(x,y)$

, we extract transverse modes by projecting it onto

![]() $\phi _n(y)=\sqrt {(2-\delta _{0n})/L}\cos (n\pi y/L)$

$\phi _n(y)=\sqrt {(2-\delta _{0n})/L}\cos (n\pi y/L)$

Figure 8. Real part of the experimental fields

![]() $\hat {\eta }_1(x,y)$

for parallel waveguide (a for

$\hat {\eta }_1(x,y)$

for parallel waveguide (a for

![]() $kL/\pi \approx 0.79$

and c for

$kL/\pi \approx 0.79$

and c for

![]() $kL/\pi \approx 0.94$

) and rectangular cloaking geometry (b for

$kL/\pi \approx 0.94$

) and rectangular cloaking geometry (b for

![]() $kL/\pi \approx 0.79$

and d for

$kL/\pi \approx 0.79$

and d for

![]() $kL/\pi \approx 0.94$

). Wave fields are normalized by the incident wave amplitude.

$kL/\pi \approx 0.94$

). Wave fields are normalized by the incident wave amplitude.

Figure 9. Comparison of numerical and experimental results. Reflection

![]() $|R|$

and transmission

$|R|$

and transmission

![]() $|T|$

coefficients as a function of frequency

$|T|$

coefficients as a function of frequency

![]() $kL/\pi$

. Black markers (experiment) and solid magenta lines (numerical simulation) correspond to the reference waveguide with straight walls. Blue markers (experiment) and red solid lines (numerical simulation) correspond to the waveguide with modified walls.

$kL/\pi$

. Black markers (experiment) and solid magenta lines (numerical simulation) correspond to the reference waveguide with straight walls. Blue markers (experiment) and red solid lines (numerical simulation) correspond to the waveguide with modified walls.

In the considered frequency range, only the plane mode propagates. This fact allows us to extract reflection

![]() $R$

and transmission

$R$

and transmission

![]() $T$

coefficients using (2.4) (taking into account reflection from the end of the channel). In figure 9, we present a comparison of both coefficients as a function of

$T$

coefficients using (2.4) (taking into account reflection from the end of the channel). In figure 9, we present a comparison of both coefficients as a function of

![]() $kL/\pi$

for numerical simulations and experimental values. The error bars for the coefficients were estimated based on four realizations of the experiment at a

$kL/\pi$

for numerical simulations and experimental values. The error bars for the coefficients were estimated based on four realizations of the experiment at a

![]() $95\,\%$

confidence level and expressed as

$95\,\%$

confidence level and expressed as

![]() $\overline {|R|} \pm t_{(n-1,1-\alpha /2)}{s}/{\sqrt {n}}$

(similarly

$\overline {|R|} \pm t_{(n-1,1-\alpha /2)}{s}/{\sqrt {n}}$

(similarly

![]() $\overline {|T|}$

) with

$\overline {|T|}$

) with

![]() $n$

,

$n$

,

![]() $\overline {|R|},s$

being the number of realizations, sample mean and sample standard deviation of the results, respectively (Martin Reference Martin2012). The

$\overline {|R|},s$

being the number of realizations, sample mean and sample standard deviation of the results, respectively (Martin Reference Martin2012). The

![]() $t_{(n-1,1-\alpha /2)}$

parameter is the critical value of the Student’s t distribution for significance level

$t_{(n-1,1-\alpha /2)}$

parameter is the critical value of the Student’s t distribution for significance level

![]() $\alpha =0.05$

. We observe a significant reduction of the reflection coefficient in the entire frequency range. In the inset of figure 9, we present the same reflection coefficient in logarithmic scale to demonstrate the extremely high efficiency of the proposed cloaking device. Although the experimental values are not as good as in numerical simulations, one can notice that the reflection coefficient decreases by at least ten times the reference value corresponding to the straight parallel waveguide, meaning that, in the investigated frequency range, the energy of the reflected wave, proportional to

$\alpha =0.05$

. We observe a significant reduction of the reflection coefficient in the entire frequency range. In the inset of figure 9, we present the same reflection coefficient in logarithmic scale to demonstrate the extremely high efficiency of the proposed cloaking device. Although the experimental values are not as good as in numerical simulations, one can notice that the reflection coefficient decreases by at least ten times the reference value corresponding to the straight parallel waveguide, meaning that, in the investigated frequency range, the energy of the reflected wave, proportional to

![]() $|R|^2$

, is at least a hundred times lower than initially. The best experimental result is obtained for

$|R|^2$

, is at least a hundred times lower than initially. The best experimental result is obtained for

![]() $kL/\pi \approx 0.64$

, where backscattered energy is around 5000 times lower than in the reference case.

$kL/\pi \approx 0.64$

, where backscattered energy is around 5000 times lower than in the reference case.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we present a novel technique for achieving an invisibility effect in a water wave system with a circular cylinder placed at the plane of symmetry of a parallel waveguide. Confinement of the considered system and the low-frequency range allow us to treat the problem as one-dimensional in the far field. We obtain the cloaking phenomenon by considering local deformations of the waveguide walls. The effect is visible in a broad range of frequencies. Wall deformation needs to be localized in the neighbourhood of the defect and adjusted for a given shape of an obstacle, suggesting our cloak belongs to a class of devices based on scattering cancellation (Fleury & Alu Reference Fleury and Alu2014). In numerical simulations, the reflection coefficient for the waveguide with the rectangular indentations is at least 20 times lower than that of the reference case with parallel waveguide walls in the entire frequency range. We confirm the high efficiency of the proposed technique experimentally, where the energy of the reflected wave is at least 100 times lower than in the reference case in the investigated frequency range.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank L. Laniewski-Wollk for his support in the implementation of the multipole method used for the verification of the results.

Funding

This research was funded in whole by the National Science Centre Poland, under agreement UMO-2020/39/D/ST8/01. For the purpose of Open Access, the authors have applied a CC-BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

Declaration of interests

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in RepOD at https://doi.org/10.18150/PRNRHW.

Appendix A

In this section, we present results concerning the minimization of the total scattered energy. The optimization of the cloaking factor

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

leads to the geometries presented in figure 10(a). The reflection coefficients corresponding to the geometries defined through Fourier series, trapezium and rectangle are presented in figure 10(b) by blue, green and red solid lines, respectively. In figure 10(c), we present the phase shift

$\chi _{sc}$

leads to the geometries presented in figure 10(a). The reflection coefficients corresponding to the geometries defined through Fourier series, trapezium and rectangle are presented in figure 10(b) by blue, green and red solid lines, respectively. In figure 10(c), we present the phase shift

![]() $\Delta \varphi$

for the two optimizations, where the top and the bottom figures correspond to the optimization of

$\Delta \varphi$

for the two optimizations, where the top and the bottom figures correspond to the optimization of

![]() $\chi$

and

$\chi$

and

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

, respectively. The phase shift is non-zero in both optimization cases and is lower for

$\chi _{sc}$

, respectively. The phase shift is non-zero in both optimization cases and is lower for

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

. However, the reflection coefficient is significantly higher than that obtained in the minimization process of

$\chi _{sc}$

. However, the reflection coefficient is significantly higher than that obtained in the minimization process of

![]() $\chi$

. Geometry providing the lowest value of

$\chi$

. Geometry providing the lowest value of

![]() $\chi$

results in

$\chi$

results in

![]() $\chi _{sc}=0.4$

. To sum up, we can obtain a significant difference in the reflection coefficient at the cost of an increase in phase shift.

$\chi _{sc}=0.4$

. To sum up, we can obtain a significant difference in the reflection coefficient at the cost of an increase in phase shift.

Figure 10. Optimization of the cloaking factor

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

: (a) comparison of the resulting geometries, (b) reflection coefficient as a function of frequency

$\chi _{sc}$

: (a) comparison of the resulting geometries, (b) reflection coefficient as a function of frequency

![]() $kL/\pi$

and (c) phase shift

$kL/\pi$

and (c) phase shift

![]() $\Delta \varphi$

for two optimizations (top: optimization of

$\Delta \varphi$

for two optimizations (top: optimization of

![]() $\chi$

and bottom: optimization of

$\chi$

and bottom: optimization of

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

). The geometries of indentations providing the minimum value of

$\chi _{sc}$

). The geometries of indentations providing the minimum value of

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

have the following dimensions: (i) Fourier (

$\chi _{sc}$

have the following dimensions: (i) Fourier (

![]() $h_g/L= 0.2024, \delta /L = 1.4405, \gamma /L = 0.7281, N = 2$

), (ii) trapezium (

$h_g/L= 0.2024, \delta /L = 1.4405, \gamma /L = 0.7281, N = 2$

), (ii) trapezium (

![]() $a/L=0.606, b/L=0.1458, h_t/L=0.2391$

), (iii) rectangle (

$a/L=0.606, b/L=0.1458, h_t/L=0.2391$

), (iii) rectangle (

![]() $h_r/L=0.1694, w_r/L=0.4286$

).

$h_r/L=0.1694, w_r/L=0.4286$

).

Figure 11. The influence of mesh element size on the cloaking factor (a)

![]() $\chi$

and (b)

$\chi$

and (b)

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

value for three considered geometries. The vertical dashed line corresponds to the mesh size employed in the optimization, i.e.

$\chi _{sc}$

value for three considered geometries. The vertical dashed line corresponds to the mesh size employed in the optimization, i.e.

![]() $h_{max }/L=0.01$

.

$h_{max }/L=0.01$

.

To verify the numerical results, we perform a mesh grid independence study by changing the maximum size of a single finite element. The largest size of finite element

![]() $h_{max }/L$

is selected to ensure a minimum of 20 elements per wavelength. We successively decrease the element size and determine the corresponding cloaking factor

$h_{max }/L$

is selected to ensure a minimum of 20 elements per wavelength. We successively decrease the element size and determine the corresponding cloaking factor

![]() $\chi$

and

$\chi$

and

![]() $\chi _{sc}$

. The results are presented in figure 11. The objective function

$\chi _{sc}$

. The results are presented in figure 11. The objective function

![]() $\chi$

values for

$\chi$

values for

![]() $h_{max }/L = 0.01$

do not significantly differ from those obtained for lower values of

$h_{max }/L = 0.01$

do not significantly differ from those obtained for lower values of

![]() $h_{max }/L$

. We conclude that sufficient convergence is achieved for

$h_{max }/L$

. We conclude that sufficient convergence is achieved for

![]() $h_{max }/L = 0.01$

in both optimization processes.

$h_{max }/L = 0.01$

in both optimization processes.