1. Introduction

Vibrations can play a pivotal role in determining the properties of a wide range of fluid motions. Sometimes, in mechanical systems, vibrations are both unavoidable and undesirable because they may make the flow sensitive to instability and prone to premature breakdown to turbulence. On the other hand, vibrations can be used quite intentionally as a flow control method to reduce the flow resistance or to provide a propulsive effect. In other applications, we wish to actively encourage the vibrations of the conduit to enhance fluid mixing, including inducing low Reynolds number chaos (Gepner & Floryan Reference Gepner and Floryan2020). Then, of course, one is interested in determining changes in the fundamental flow properties caused by vibrations. Furthermore, vibrations are known to play a role in various environmental flow phenomena, with the classic example prototype example provided by Langmuir circulation, which is driven by wind that blows waves across the surface of an expanse of water (Leibovich Reference Leibovich1983; Thorpe Reference Thorpe2004).

Our concern in this work is to provide insight into the stability of shear flows affected by vibrations used as an active control tool. The principal goal of this class of problems is to devise a strategy such that energy saving from drag reduction exceeds the energy expended in applying the control. Until recently, it was thought that this goal was unachievable (Bewley Reference Bewley2009), but this view has been challenged recently (Floryan Reference Floryan2023). In the work described below, we consider an active flow distributed propulsion system in which part of the externally supplied energy is used to reduce the resistance rather than overcome it. However, rather than just measuring the effectiveness of the process in terms of an energy balance assuming no change in the performance of the system, we attempt to improve matters by enhancing the propulsion energy (Haq & Floryan Reference Haq and Floryan2022; Floryan, Aman & Panday Reference Floryan, Aman and Panday2023b ). The concept of distributed propulsion is not new and has a long history within various biological flows (Taylor Reference Taylor1951; Blake & Sleigh Reference Blake and Sleigh1974; Katz Reference Katz1974; Brennen & Winet Reference Brennen and Winet1977; Chan, Balmforth & Hosoi Reference Chan, Balmforth and Hosoi2005; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Bush, Hosoi and Lauga2008; Lauga Reference Lauga2016). More recently, other instances of distributed propulsion have been investigated at larger scales; some examples include nonlinear streaming created by wall transpiration (Jiao & Floryan Reference Jiao and Floryan2021), the so-called pattern interaction effect (Floryan & Inasawa Reference Floryan and Inasawa2021) that leads to thermal drift (Abtahi & Floryan Reference Abtahi and Floryan2017), patterned heating (Floryan & Floryan Reference Floryan and Floryan2015), nonlinear thermal streaming (Floryan et al. Reference Floryan, Aman and Panday2023), thermal waves (Hossain & Floryan Reference Hossain and Floryan2023) and wall vibrations (Floryan & Haq Reference Floryan and Haq2022). The previously mentioned biological examples of distributed propulsion occur on such short scales that the stability of the flow is ensured, but this issue is not so clear-cut when dealing with the other problems. To date, scant attention has been paid to this question, and it is this problem that we seek to address herein.

We tackle our task by selecting a straightforward paradigm problem free from as many superfluous and distracting effects as is feasible. To that end, we focus on the instabilities caused by vibrations in wall-bounded shear layers. More precisely, we investigate the effect of wall vibrations on two-dimensional laminar Couette flow. Since this flow is linearly stable without vibrations (Romanov Reference Romanov1972), we can be assured that any instability can be ascribed to the imposition of vibration rather than being an intrinsic property of the motion. It is already known that this flow can be destabilised using modifications produced by wall transpiration (Jiao & Floryan Reference Jiao and Floryan2021) and surface grooves (Floryan Reference Floryan2002), but its response to wall vibrations is unknown. We focus on disturbances that form streamwise vortices and explore the system response across a wide range of vibration wavelengths and phase speeds. Our calculations are restricted to cases in which the amplitude of the vibrations is less than about 5 % of the slot opening. There are two reasons for this. First, any uncontrolled vibrations generally are of small amplitude, as any system susceptible to larger unwanted vibrations normally necessitates a complete redesign. Conversely, when the vibrations are intentional, they are frequently created using piezoelectric actuators characterised by small-amplitude and high-frequency displacements. Finally, we mention limiting the flow Reynolds number to less than 2000 as we are interested in laminar flows. Experimental evidence suggests that Couette flow becomes turbulent at larger Reynolds numbers (Tillmark & Alfredsson Reference Tillmark and Alfredsson1992).

Our control strategy belongs to a class of problems that uses a spatial pattern of actuation rather than relying solely on the strength of the forcing. In most circumstances, it is thought that using a pattern-based control is typically associated with lower energy actuation costs. One question in pattern-based control is how best to select the spatial distribution. Clearly, an almost limitless range of options is available, and exploring them on a case-by-case basis is not feasible. If the pattern is spatially periodic, then it is natural to write the profile of the wall vibration using an appropriate Fourier series. In our analysis, we will suppose that the wall shape is just a single Fourier mode of a given wavelength. While this may seem somewhat over-simplistic, there is evidence that the flow characteristics over a wall of a more general profile can be well modelled by the single component if chosen carefully (Floryan Reference Floryan2007). The reduced model identifies those parts of Fourier space that are hydraulically active by considering the projection of an arbitrary pattern onto Fourier space and determining whether any dynamically important components are involved.

To understand how wall vibrations can influence the stability of wall-bounded shear flows, we organise the remainder of the paper in the following way. In § 2, we describe our idealised two-dimensional model problem that consists of an infinite slot bounded by a translating smooth upper plate and a lower surface whose shape takes the form of travelling waves. Then, in § 3, we isolate the primary state of the flow, i.e. the Couette flow modified by the vibrations. This basic state requires a numerical solution of the relevant field equations. Once this has been found, we move on to § 4, which outlines the key stability problem and discusses the numerical solution of the disturbance equations. Most of our results are collected in § 5, where the characteristics of flow instabilities caused by wall vibrations are described. The paper closes with a few final remarks and observations.

2. Problem formulation

Consider flow in a slot driven by movement of the upper plate with a prescribed velocity

![]() $U_{top}$

while the lower plate is stationary. The slot extends to

$U_{top}$

while the lower plate is stationary. The slot extends to

![]() $\pm \mathrm{\infty }$

in the X- and Z-directions with plates placed at a distance

$\pm \mathrm{\infty }$

in the X- and Z-directions with plates placed at a distance

![]() $2h$

apart, as shown in figure 1. The lower plate is exposed to vibrations in the form of a sinusoidal travelling wave, resulting in the time-dependent slot geometry of the form

$2h$

apart, as shown in figure 1. The lower plate is exposed to vibrations in the form of a sinusoidal travelling wave, resulting in the time-dependent slot geometry of the form

where subscript

![]() $L$

refers to the lower plate, and

$L$

refers to the lower plate, and

![]() $h$

was used as the length scale.

$h$

was used as the length scale.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the flow system.

The velocity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{{V}}=(u,v,w)$

is scaled with the viscous velocity scale

$\boldsymbol{{V}}=(u,v,w)$

is scaled with the viscous velocity scale

![]() $U_{v}=v/h$

, the pressure

$U_{v}=v/h$

, the pressure

![]() $p$

is scaled with

$p$

is scaled with

![]() $\rho U_{v}^{2}$

(where

$\rho U_{v}^{2}$

(where

![]() $\rho$

denotes the fluid density), and the time

$\rho$

denotes the fluid density), and the time

![]() $t$

is scaled with

$t$

is scaled with

![]() $h/U_{v}$

. The relevant boundary conditions are

$h/U_{v}$

. The relevant boundary conditions are

where

is the Reynolds number. Since the flow is driven solely by the movement of the upper plate, the pressure gradient constraint in the form

where subscript m denotes the mean value, must be imposed.

It is simpler to carry out detailed calculations using the frame of reference moving with the wave, which leads to Galileo’s transformation of the form

The complete problem formulation can now be written as

The next section begins with a detailed analysis of the two-dimensional stationary state in the moving reference frame.

3. Determination of the primary state

The primary state has the form of a two-dimensional stationary flow in the moving frame of reference, i.e.

![]() $w=0$

,

$w=0$

,

![]() ${\partial }/{\partial z}=0$

,

${\partial }/{\partial z}=0$

,

![]() ${\partial }/{\partial t}=0$

. This flow is expected to bifurcate to a secondary state consisting of streamwise vortices. This analysis aims to determine critical conditions leading to such a bifurcation. We begin with a discussion of the properties of the stationary state before proceeding to stability analysis.

${\partial }/{\partial t}=0$

. This flow is expected to bifurcate to a secondary state consisting of streamwise vortices. This analysis aims to determine critical conditions leading to such a bifurcation. We begin with a discussion of the properties of the stationary state before proceeding to stability analysis.

3.1. Problem formulation and numerical solution

The translation of the upper plate in the absence of any vibrations creates a simple Couette flow. The velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_{\mathbf{0}}$

, pressure

$\boldsymbol{v}_{\mathbf{0}}$

, pressure

![]() $p_{0}$

, pulling force applied to the upper plate (per unit length and width)

$p_{0}$

, pulling force applied to the upper plate (per unit length and width)

![]() $F_{0}$

, shear acting on the upper plate

$F_{0}$

, shear acting on the upper plate

![]() $\tau _{0}$

, and flow rate

$\tau _{0}$

, and flow rate

![]() $Q_{0}$

are given by

$Q_{0}$

are given by

Here, the velocity of the upper plate

![]() $U_{top}$

has been adopted as the velocity scale,

$U_{top}$

has been adopted as the velocity scale,

![]() $\rho U_{top}^{2}$

as the pressure scale, and

$\rho U_{top}^{2}$

as the pressure scale, and

![]() $U_{top}\mu /h$

as the surface force scale, and the flow rate was scaled using

$U_{top}\mu /h$

as the surface force scale, and the flow rate was scaled using

![]() $U_{top}$

. To describe the effects of surface vibrations, we represent the total flow quantities as a sum of the reference flow and the vibration-induced modifications, i.e.

$U_{top}$

. To describe the effects of surface vibrations, we represent the total flow quantities as a sum of the reference flow and the vibration-induced modifications, i.e.

In the above,

![]() $(u_{B},v_{B})$

,

$(u_{B},v_{B})$

,

![]() $p_{B}$

,

$p_{B}$

,

![]() $\psi _{B}$

,

$\psi _{B}$

,

![]() $Q_{B,mean}$

,

$Q_{B,mean}$

,

![]() ${\tau} _{B}$

and

${\tau} _{B}$

and

![]() $F_{B}$

denote the complete velocity, pressure, stream function, mean flow rate, shear, and pulling force, respectively, and

$F_{B}$

denote the complete velocity, pressure, stream function, mean flow rate, shear, and pulling force, respectively, and

![]() $(u_{1,B},v_{1,B})$

,

$(u_{1,B},v_{1,B})$

,

![]() $\psi _{1,B}$

,

$\psi _{1,B}$

,

![]() $p_{1,B}$

,

$p_{1,B}$

,

![]() $Q_{1B,mean}$

and

$Q_{1B,mean}$

and

![]() $F_{1,B}$

denote the velocity, stream function, pressure, mean flow rate, and pulling force modifications caused by vibrations. We eliminate pressure by introducing stream function modifications

$F_{1,B}$

denote the velocity, stream function, pressure, mean flow rate, and pulling force modifications caused by vibrations. We eliminate pressure by introducing stream function modifications

![]() $\psi _{1,B}$

defined as

$\psi _{1,B}$

defined as

Taking the

![]() $y$

-derivative of (3.2a

) and the

$y$

-derivative of (3.2a

) and the

![]() $x$

-derivative of (3.2b

), and subtracting the latter from the former, leads to the formulation of the form

$x$

-derivative of (3.2b

), and subtracting the latter from the former, leads to the formulation of the form

In the above,

![]() $N_{uv}\equiv ({\partial }/{\partial y})(({\partial }/{\partial x})(\widehat{u_{1,B}u_{1,B}})+({\partial }/{\partial y})(\widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}}))-({\partial }/{\partial x})(({\partial }/{\partial x})(\widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}})+({\partial }/{\partial y})(\widehat{v_{1,B}v_{1,B}}))$

, and hats denote products of quantities. The above system needs to be supplemented by the pressure gradient constraint (2.6k), whose explicit form depends on the type of discretisation.

$N_{uv}\equiv ({\partial }/{\partial y})(({\partial }/{\partial x})(\widehat{u_{1,B}u_{1,B}})+({\partial }/{\partial y})(\widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}}))-({\partial }/{\partial x})(({\partial }/{\partial x})(\widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}})+({\partial }/{\partial y})(\widehat{v_{1,B}v_{1,B}}))$

, and hats denote products of quantities. The above system needs to be supplemented by the pressure gradient constraint (2.6k), whose explicit form depends on the type of discretisation.

The discretisation process begins with the transformation

which maps the strip

![]() $y\in (-1-y_{b},1)$

in the

$y\in (-1-y_{b},1)$

in the

![]() $y$

-direction into the strip

$y$

-direction into the strip

![]() $\hat{y}\in (-1,1)$

in the

$\hat{y}\in (-1,1)$

in the

![]() $\hat{y}$

-direction. Here,

$\hat{y}$

-direction. Here,

![]() $y_{b}$

denotes the location of the lower extremity of the lower plate. This preliminary step is required to use the standard definition of Chebyshev polynomials in discretisation. The unknowns are expressed in terms of Fourier expansions of the form

$y_{b}$

denotes the location of the lower extremity of the lower plate. This preliminary step is required to use the standard definition of Chebyshev polynomials in discretisation. The unknowns are expressed in terms of Fourier expansions of the form

\begin{equation}q(x,\hat{y})=\sum _{n=-N_{B}}^{+N_{B}}q^{(n)}(\hat{y})\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}n\alpha x},\end{equation}

\begin{equation}q(x,\hat{y})=\sum _{n=-N_{B}}^{+N_{B}}q^{(n)}(\hat{y})\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}n\alpha x},\end{equation}

where

![]() $q$

stands for any of the following quantities:

$q$

stands for any of the following quantities:

![]() $\psi _{1,B},u_{1,B}, v_{1,B}, \widehat{u_{1,B}u_{1,B}}, \widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}},\widehat{v_{1,B}v_{1,B}}$

, and the modal functions

$\psi _{1,B},u_{1,B}, v_{1,B}, \widehat{u_{1,B}u_{1,B}}, \widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}},\widehat{v_{1,B}v_{1,B}}$

, and the modal functions

![]() $q^{(m)}(\hat{y})$

satisfy the reality conditions, i.e.

$q^{(m)}(\hat{y})$

satisfy the reality conditions, i.e.

![]() $q^{(m)}$

is the complex conjugate of

$q^{(m)}$

is the complex conjugate of

![]() $q^{(-m)}$

. Substitution of (3.7) into (3.4), and separation of Fourier modes, lead to a system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations of the form

$q^{(-m)}$

. Substitution of (3.7) into (3.4), and separation of Fourier modes, lead to a system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations of the form

\begin{align} &\left[-2n^{2}\alpha ^{2}{\Gamma ^{2}}{\rm D}^{2}+{\Gamma ^{4}}{\rm D}^{4}+\left(n\alpha \right)^{4}-{\rm i}n\alpha (Re\, u_{o}-c)({\Gamma ^{2}}{\rm D}^{2}-\left(n\alpha \right)^{2})\nonumber \right.\\&\quad\left. +{{\rm i}n}\alpha\, Re\,\Gamma ^{2}{\rm D}^{2}u_{0}\right]\,\psi _{1,B}^{(n)}(y)={{\rm i}n}\alpha \Gamma {\rm D}\,\widehat{u_{1,B}u_{1,B}}^{(n)}+({\Gamma ^{2}}{\rm D}^{2}+\left(n\alpha \right)^{2})\,\widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}}^{(n)}\nonumber \\&\quad-{{\rm i}n}\alpha \Gamma {\rm D}\,\widehat{v_{1,B}v_{1,B}}^{(n)},\end{align}

\begin{align} &\left[-2n^{2}\alpha ^{2}{\Gamma ^{2}}{\rm D}^{2}+{\Gamma ^{4}}{\rm D}^{4}+\left(n\alpha \right)^{4}-{\rm i}n\alpha (Re\, u_{o}-c)({\Gamma ^{2}}{\rm D}^{2}-\left(n\alpha \right)^{2})\nonumber \right.\\&\quad\left. +{{\rm i}n}\alpha\, Re\,\Gamma ^{2}{\rm D}^{2}u_{0}\right]\,\psi _{1,B}^{(n)}(y)={{\rm i}n}\alpha \Gamma {\rm D}\,\widehat{u_{1,B}u_{1,B}}^{(n)}+({\Gamma ^{2}}{\rm D}^{2}+\left(n\alpha \right)^{2})\,\widehat{u_{1,B}v_{1,B}}^{(n)}\nonumber \\&\quad-{{\rm i}n}\alpha \Gamma {\rm D}\,\widehat{v_{1,B}v_{1,B}}^{(n)},\end{align}

where

![]() ${\rm D}={\rm d}/{{\rm d}\hat{y}}$

, and the right-hand side provides coupling between different modes. These equations need to be supplemented by the relevant form of boundary conditions. Boundary conditions at the upper plate can be set explicitly for each Fourier mode, i.e.

${\rm D}={\rm d}/{{\rm d}\hat{y}}$

, and the right-hand side provides coupling between different modes. These equations need to be supplemented by the relevant form of boundary conditions. Boundary conditions at the upper plate can be set explicitly for each Fourier mode, i.e.

Since (3.9a ) does not include mode zero, the relevant boundary conditions required separate development described below. Boundary conditions at the lower plate involve a combination of modes coupled through the plate geometry. We start by expressing them in terms of the stream function in the form

The condition (3.5d

) is written in an alternative way by noting that variations in

![]() $\psi _{B}$

along the lower plate can be expressed as

$\psi _{B}$

along the lower plate can be expressed as

Integrating (3.11) along this plate yields

where the constant of integration was selected by assuming that

![]() $\psi _{1,B}(x_{0})=0$

, with

$\psi _{1,B}(x_{0})=0$

, with

![]() $x_{0}$

being an arbitrary point along the plate. The stream function is constant along the upper plate, i.e.

$x_{0}$

being an arbitrary point along the plate. The stream function is constant along the upper plate, i.e.

![]() $\psi _{B}=G$

, where

$\psi _{B}=G$

, where

![]() $G$

needs to be determined from the pressure gradient constraint. This constraint can be expressed as

$G$

needs to be determined from the pressure gradient constraint. This constraint can be expressed as

with details of the derivation explained in Appendix A. The reader may note that this constraint involves both ends of the solution domain. Expressing the remaining conditions using modal functions requires invoking the immersed boundary conditions method.

The ordinary differential equations (3.8) arising from Fourier decomposition were discretised by expressing modal functions as Chebyshev expansions, and algebraic equations for the expansion coefficients were constructed using the Galerkin projection method. The irregularity of the flow domain was handled using the spectrally accurate immersed boundary conditions method, with flow boundary conditions replaced by constraints. Details of implementations of these conditions are omitted from this presentation due to their excessive length, but can be found in Szumbarski & Floryan (Reference Szumbarski and Floryan1999) and Husain, Szumbarski & Floryan (Reference Husain, Szumbarski and Floryan2009). These constraints were implemented using the tau method (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Hussaini, Quarteroni and Zang1992). The overall algorithm is gridless and spectrally accurate. The computations were carried out with at least five-digit accuracy, and this requirement was satisfied by selecting the required number of Fourier modes and Chebyshev polynomials to be used in the computations.

In the solution process, the right-hand side of (3.8) was assumed to be known (taken from the previous iteration), and the system was solved to provide a new approximation for

![]() $\psi _{1,B}(x,\hat{y})$

. A new approximation for velocity components was determined, leading to a new approximation of the right-hand side, then a new approximation for

$\psi _{1,B}(x,\hat{y})$

. A new approximation for velocity components was determined, leading to a new approximation of the right-hand side, then a new approximation for

![]() $\psi _{1,B}(x,\hat{y})$

was computed. The process was continued until convergence was achieved.

$\psi _{1,B}(x,\hat{y})$

was computed. The process was continued until convergence was achieved.

The stability analysis requires knowledge of the velocity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{{V}}_{B}=(u_{B},v_{B},0)$

and the vorticity vector

$\boldsymbol{{V}}_{B}=(u_{B},v_{B},0)$

and the vorticity vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{\omega}_{B}=(\xi _{B},\eta _{B},\phi _{B})=(0,0,{\partial v_{B}}/{\partial x}-{\partial u_{B}}/{\partial y})$

of the stationary state. These quantities were determined in the post-processing stage and were represented as

$\boldsymbol{\omega}_{B}=(\xi _{B},\eta _{B},\phi _{B})=(0,0,{\partial v_{B}}/{\partial x}-{\partial u_{B}}/{\partial y})$

of the stationary state. These quantities were determined in the post-processing stage and were represented as

\begin{equation}\left[u_{B, }v_{B},\phi _{B}\right]\left(x,\hat{y}\right)=\sum _{n=-N_{B}}^{N_{B}}\left[f_{u}^{\lt n\gt },f_{v}^{\lt n\gt },f_{\phi }^{\lt n\gt }\right]\left(\hat{y}\right)\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}n\alpha x}.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\left[u_{B, }v_{B},\phi _{B}\right]\left(x,\hat{y}\right)=\sum _{n=-N_{B}}^{N_{B}}\left[f_{u}^{\lt n\gt },f_{v}^{\lt n\gt },f_{\phi }^{\lt n\gt }\right]\left(\hat{y}\right)\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}n\alpha x}.\end{equation}

3.2. Properties of the primary state

Vibrations propel the fluid along the lower plate using the peristaltic effect, thus reducing the relative fluid velocity with respect to the moving plate and reducing shear stress at that plate. Reduction of flow resistance was discussed extensively in Floryan & Haq (Reference Floryan and Haq2022). Its effectiveness can be gauged by determining the external force required to maintain the movement of the upper plate at the same velocity with and without vibrations. The shear stress on the upper plate was integrated over a wavelength to determine the vibrations-induced change of the pulling force. The shear stress

![]() $\sigma _{Xv,U}$

that acts on the fluid and the external pulling force (per unit length and width) on the upper plate

$\sigma _{Xv,U}$

that acts on the fluid and the external pulling force (per unit length and width) on the upper plate

![]() $F_{B}$

are given by

$F_{B}$

are given by

\begin{equation}\sigma _{xv,U}=\left.\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial y}\right| _{y=1},\quad F_{B}=\lambda ^{-1}\int _{0}^{\lambda }\left.\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial y}\right| _{y=1}{\rm d}x,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\sigma _{xv,U}=\left.\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial y}\right| _{y=1},\quad F_{B}=\lambda ^{-1}\int _{0}^{\lambda }\left.\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial y}\right| _{y=1}{\rm d}x,\end{equation}

where

![]() $\lambda ={2\pi }/{\alpha }$

denotes wavelength. The force correction can be evaluated as

$\lambda ={2\pi }/{\alpha }$

denotes wavelength. The force correction can be evaluated as

and its negative values correspond to a reduction of the required external force.

Figure 2 illustrates variations of

![]() $F_{1,B}$

normalised as

$F_{1,B}$

normalised as

![]() $F_{norm}={(F_{1,B})}/{(Re\,F_{0}A^{2})}$

. The resistance reduction zones are greyed for easy identification. The

$F_{norm}={(F_{1,B})}/{(Re\,F_{0}A^{2})}$

. The resistance reduction zones are greyed for easy identification. The

![]() $c$

-axis can be divided into two zones. The lower zone corresponds to

$c$

-axis can be divided into two zones. The lower zone corresponds to

![]() $0\lt c\lt Re$

, i.e. the wave velocity is in the fluid velocity range. Such waves are called subcritical (Floryan & Haq Reference Floryan and Haq2022). The upper zone corresponds to

$0\lt c\lt Re$

, i.e. the wave velocity is in the fluid velocity range. Such waves are called subcritical (Floryan & Haq Reference Floryan and Haq2022). The upper zone corresponds to

![]() $c\gt Re$

, i.e. these waves are faster than the fluid and are called supercritical. The supercritical waves generally reduce flow losses, with this reduction changing in a fairly regular manner and increasing with

$c\gt Re$

, i.e. these waves are faster than the fluid and are called supercritical. The supercritical waves generally reduce flow losses, with this reduction changing in a fairly regular manner and increasing with

![]() $c$

and

$c$

and

![]() $\alpha$

. The subcritical waves exhibit complex behaviour that changes with

$\alpha$

. The subcritical waves exhibit complex behaviour that changes with

![]() $Re$

– they generally increase flow losses, but there are islands in the parameter space where they decrease losses, so making generalisations is difficult. The natural flow frequencies of the Orr–Sommerfeld modes in the absence of vibrations overlap with the subcritical waves, but no near resonance was observed.

$Re$

– they generally increase flow losses, but there are islands in the parameter space where they decrease losses, so making generalisations is difficult. The natural flow frequencies of the Orr–Sommerfeld modes in the absence of vibrations overlap with the subcritical waves, but no near resonance was observed.

Figure 2. Variations in the normalised force correction

![]() $F_{norm}={F_{1,B}}/({Re\,F_{0}A^{2}})$

as a function of

$F_{norm}={F_{1,B}}/({Re\,F_{0}A^{2}})$

as a function of

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $c$

for (a)

$c$

for (a)

![]() $Re=800$

, (b)

$Re=800$

, (b)

![]() $Re=1000$

, (c)

$Re=1000$

, (c)

![]() $Re=1500$

, (d)

$Re=1500$

, (d)

![]() $Re=2000$

. The grey shading indicates negative values; the red line shows conditions giving

$Re=2000$

. The grey shading indicates negative values; the red line shows conditions giving

![]() $F_{1,B}=0$

; zones between the blue lines provide the range of natural frequencies of the Orr–Sommerfeld modes in the absence of vibrations.

$F_{1,B}=0$

; zones between the blue lines provide the range of natural frequencies of the Orr–Sommerfeld modes in the absence of vibrations.

An analysis of the flow modifications provides another view of the flow response. Figure 3 shows how subcritical waves modify the streamwise component profiles. These structures are concentrated in the boundary layer adjacent to the vibrating wall when the waves are sufficiently short, as illustrated in the third column in figure 3. The fluid outside the boundary layer behaves as if this layer were a wall moving with the velocity correction outside the boundary layer having the form of Couette flow driven by the velocity at the edge of the boundary layer. This type of response has previously been referred to as a ‘moving wall’ pattern (Floryan & Haq Reference Floryan and Haq2022). By contrast, long waves seem to produce modifications in the form of a sloshing-type behaviour that extends across the whole slot, with the forward movement occurring around the wave troughs, and the backward movement near the crests. Unsurprisingly, modes of an intermediate wavelength are somewhat of a hybrid of these two extremes: the middle column of figure 3 shows some structure concentration near the vibrating wall, while some sloshing still penetrates the slot interior. The character of the flow response remains qualitatively the same regardless of the flow Reynolds number (details not shown).

Figure 3. Distributions of the x-component of the vibrations-induced velocity modifications

![]() $u_{1,B}$

at

$u_{1,B}$

at

![]() ${x}/{\lambda }=0,0.25,0.5,0.75$

for

${x}/{\lambda }=0,0.25,0.5,0.75$

for

![]() $Re=1000$

,

$Re=1000$

,

![]() $A=0.04$

.

$A=0.04$

.

4. Formulation of the linear stability theory and its numerical solution

We have now seen how the imposed wall vibrations modify the basic state, and this raises the possibility that this new state may possess stability characteristics qualitatively very different from the unmodified (linearly stable) Couette flow (Romanov Reference Romanov1972). We investigate this question here, focusing on possible instabilities leading to streamwise vortices forming.

We begin by writing the governing equations in the moving frame of reference expressed in terms of the vorticity transport and continuity equations, i.e.

Unsteady three-dimensional disturbances are added to the stationary state in the form

where subscript

![]() $D$

denotes disturbance quantities,

$D$

denotes disturbance quantities,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\omega}_{D}=(\xi _{D},\eta _{D},\phi _{D})$

,

$\boldsymbol{\omega}_{D}=(\xi _{D},\eta _{D},\phi _{D})$

,

![]() $\boldsymbol{{V}}_{D}=(u_{D},v_{D},w_{D})$

, the flow quantities (4.2) are substituted into (4.1), the base part is subtracted, and the equations are linearised. The resulting linear disturbance equations have the form

$\boldsymbol{{V}}_{D}=(u_{D},v_{D},w_{D})$

, the flow quantities (4.2) are substituted into (4.1), the base part is subtracted, and the equations are linearised. The resulting linear disturbance equations have the form

Since vibrations modulate the stationary state, the disturbance quantities can be expressed as waves with amplitudes modulated in the -direction (Floryan Reference Floryan1997), i.e.

where

![]() $\delta$

and

$\delta$

and

![]() $\mu$

are the real wavenumbers in the x- and z-directions, respectively,

$\mu$

are the real wavenumbers in the x- and z-directions, respectively,

![]() $\sigma =\sigma _{r}+{\rm i}\sigma _{i}$

is the complex frequency with

$\sigma =\sigma _{r}+{\rm i}\sigma _{i}$

is the complex frequency with

![]() $\sigma _{i}$

describing the rate of growth of disturbances and

$\sigma _{i}$

describing the rate of growth of disturbances and

![]() $\sigma _{r}$

describing their frequency, and c.c. stands for the complex conjugate. The amplitude functions

$\sigma _{r}$

describing their frequency, and c.c. stands for the complex conjugate. The amplitude functions

![]() $\boldsymbol{{G}}_{D}(x,y)$

and

$\boldsymbol{{G}}_{D}(x,y)$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\Omega}_{D}(x,y)$

are x-periodic as dictated by the type of modulation. Accordingly, these functions can be expressed in terms of Fourier expansions of the form

$\boldsymbol{\Omega}_{D}(x,y)$

are x-periodic as dictated by the type of modulation. Accordingly, these functions can be expressed in terms of Fourier expansions of the form

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{{G}}_{D}\left(x,y\right)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}[g_{u}^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{w}^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right)]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}+ \text{c.c.},\end{align}

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{{G}}_{D}\left(x,y\right)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}[g_{u}^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{w}^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right)]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}+ \text{c.c.},\end{align}

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{{\Omega} }_{D}\left(x,y\right)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}[g_{\xi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{\phi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right)]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}+\text{c.c.}.\end{align}

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{{\Omega} }_{D}\left(x,y\right)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}[g_{\xi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right),g_{\phi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right)]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}+\text{c.c.}.\end{align}

Quantities in square brackets on the right-hand sides of (4.5) are the modal functions. Combining (4.4) and (4.5) leads to the final expressions for the disturbance quantities in the form

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{{V}}_{D}(x,y,z,t)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}\left[g_{u}^{\lt m\gt }(y), g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }(y), g_{w}^{\lt m\gt }(y)\right]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}\left[(\delta +m\alpha )x+\mu z-\sigma t\right]}+\text{c.c.},\end{align}

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{{V}}_{D}(x,y,z,t)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}\left[g_{u}^{\lt m\gt }(y), g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }(y), g_{w}^{\lt m\gt }(y)\right]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}\left[(\delta +m\alpha )x+\mu z-\sigma t\right]}+\text{c.c.},\end{align}

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{\omega}_{D}\left(x,y,z,t\right)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}\left[g_{\xi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right), g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right), g_{\phi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right)\right]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}\left[(\delta +m\alpha )x+\mu z-\sigma t\right]}+\text{c.c.}.\end{align}

\begin{align}\boldsymbol{\omega}_{D}\left(x,y,z,t\right)&=\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}\left[g_{\xi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right), g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right), g_{\phi }^{\lt m\gt }\left(y\right)\right]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}\left[(\delta +m\alpha )x+\mu z-\sigma t\right]}+\text{c.c.}.\end{align}

Substituting (4.6) into (4.3a–c

) and separating Fourier modes leads to a system of coupled ordinary differential equations for the modal functions. These equations are then combined into a system involving only

![]() $g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }$

and

$g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }$

and

![]() $g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }$

in the form

$g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }$

in the form

\begin{align}T^{\lt m\gt }g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }&=-\sum _{n=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\big[(T_{1}^{\lt m-n\gt }+T_{2}^{\lt m-n\gt }+T_{3}^{\lt m-n\gt })g_{v}^{\lt m-n\gt }\nonumber\\&\quad+\left(T_{4}^{\lt m-n\gt }-T_{5}^{\lt m-n\gt }\right)g_{\eta }^{\lt m-n\gt }\big],\end{align}

\begin{align}T^{\lt m\gt }g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }&=-\sum _{n=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\big[(T_{1}^{\lt m-n\gt }+T_{2}^{\lt m-n\gt }+T_{3}^{\lt m-n\gt })g_{v}^{\lt m-n\gt }\nonumber\\&\quad+\left(T_{4}^{\lt m-n\gt }-T_{5}^{\lt m-n\gt }\right)g_{\eta }^{\lt m-n\gt }\big],\end{align}

\begin{align}S^{\lt m\gt }g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }&=\sum _{n=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}\big[\left(S_{1}^{\lt m-n\gt }+S_{2}^{\lt m-n\gt }+S_{3}^{\lt m-n\gt }\right)g_{v}^{\lt m-n\gt }\nonumber\\&\quad + \left(S_{4}^{\lt m-n\gt }-S_{5}^{\lt m-n\gt }\right)g_{\eta }^{\lt m-n\gt }\big],\end{align}

\begin{align}S^{\lt m\gt }g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }&=\sum _{n=-N_{D}}^{+N_{D}}\big[\left(S_{1}^{\lt m-n\gt }+S_{2}^{\lt m-n\gt }+S_{3}^{\lt m-n\gt }\right)g_{v}^{\lt m-n\gt }\nonumber\\&\quad + \left(S_{4}^{\lt m-n\gt }-S_{5}^{\lt m-n\gt }\right)g_{\eta }^{\lt m-n\gt }\big],\end{align}

where

![]() $N_{D}\leq m\leq -N_{D}$

, and all operators are defined in Appendix B.

$N_{D}\leq m\leq -N_{D}$

, and all operators are defined in Appendix B.

The boundary conditions for the modal functions at the upper plate follow from (4.3d ) and have a simple form, i.e.

and when expressed only in terms of

![]() $g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }$

and

$g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }$

and

![]() $g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }$

, they take the form

$g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }$

, they take the form

The boundary conditions at the lower plate involve a combination of modes dictated by the plate geometry. They can be written as

\begin{equation}\text{for }y=y_{L}(x),\,\,\! \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\!g_{u}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\,\,\! \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\!g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\,\,\! \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\!g_{w}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\text{for }y=y_{L}(x),\,\,\! \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\!g_{u}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\,\,\! \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\!g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\,\,\! \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}\!g_{w}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\end{equation}

and, when expressed in terms of

![]() $g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }$

and

$g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }$

and

![]() $g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }$

, they take the form

$g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }$

, they take the form

\begin{equation}\text{for }y=y_{L}(x),\quad \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}[-{\rm i}\mu g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }+{\rm i}t_{m}{\rm D}g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\quad \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\text{for }y=y_{L}(x),\quad \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}[-{\rm i}\mu g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }+{\rm i}t_{m}{\rm D}g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\quad \sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0,\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}[{\rm i}t_{m}g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }+{\rm i}\mu {\rm D}g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0.\end{equation}

\begin{equation}\sum _{m=-N_{D}}^{N_{D}}[{\rm i}t_{m}g_{\eta }^{\lt m\gt }+{\rm i}\mu {\rm D}g_{v}^{\lt m\gt }]\,{\rm e}^{{\rm i}m\alpha x}=0.\end{equation}

These conditions are replaced by constraints whose form suitable for numerical implementation is dictated by the discretisation applied to (4.7).

The discretisation of (4.7) relies on Chebyshev expansions, with the first step involving transformation (3.6) so that a standard definition of Chebyshev expansions can be used. The modal functions were represented as Chebyshev expansions, i.e.

\begin{equation}q_{D}^{(m)}(\hat{y})=\sum _{k=0}^{N_{K-1}}Gq_{k,D}^{(m)}\,T_{k}\left(\hat{y}\right),\end{equation}

\begin{equation}q_{D}^{(m)}(\hat{y})=\sum _{k=0}^{N_{K-1}}Gq_{k,D}^{(m)}\,T_{k}\left(\hat{y}\right),\end{equation}

where

![]() $q_{D}^{(m)}(\hat{y})$

stands for any of the modal functions, and

$q_{D}^{(m)}(\hat{y})$

stands for any of the modal functions, and

![]() $Gq_{k,D}^{(m)}$

are the unknown expansion coefficients. The complete discretisation procedure involving a combination of (4.7), (4.9), and (4.11) provides spectral accuracy. The immersed boundary conditions method was used to discretise (4.11). Details are omitted from this presentation due to their length, but can be found in Panday & Floryan (Reference Panday and Floryan2023). The use of the Galerkin projection method combined with the tau procedure (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Hussaini, Quarteroni and Zang1992) for incorporation of the boundary conditions led to an eigenvalue problem for a very large system of linear algebraic equations for the unknowns

$Gq_{k,D}^{(m)}$

are the unknown expansion coefficients. The complete discretisation procedure involving a combination of (4.7), (4.9), and (4.11) provides spectral accuracy. The immersed boundary conditions method was used to discretise (4.11). Details are omitted from this presentation due to their length, but can be found in Panday & Floryan (Reference Panday and Floryan2023). The use of the Galerkin projection method combined with the tau procedure (Canuto et al. Reference Canuto, Hussaini, Quarteroni and Zang1992) for incorporation of the boundary conditions led to an eigenvalue problem for a very large system of linear algebraic equations for the unknowns

![]() $Gq_{k,D}^{(m)}$

. The solution procedure and its accuracy testing are described in Panday & Floryan (Reference Panday and Floryan2023). All eigenvalues presented in the discussion below were determined with an accuracy of no less than four digits.

$Gq_{k,D}^{(m)}$

. The solution procedure and its accuracy testing are described in Panday & Floryan (Reference Panday and Floryan2023). All eigenvalues presented in the discussion below were determined with an accuracy of no less than four digits.

5. Discussion of results

Secondary structures in the form of vortices are aligned with the flow direction with their spanwise size given by the spanwise wavenumber

![]() $\mu$

. These vortices are modulated by the spatial form of vibrations, which means that their modulation is characterised by the wavenumber

$\mu$

. These vortices are modulated by the spatial form of vibrations, which means that their modulation is characterised by the wavenumber

![]() $\alpha$

. Our first set of results pertains to the amplification of vortex-type disturbances as a function of

$\alpha$

. Our first set of results pertains to the amplification of vortex-type disturbances as a function of

![]() $\mu$

. The growth rates are shown in figure 4 for those waves that are the most effective in producing instability (we return to this point later). Amplification of the modes is possible only if the phase speed of the vibration is sufficiently large, and our calculations show that the phase speed needs to reach at least

$\mu$

. The growth rates are shown in figure 4 for those waves that are the most effective in producing instability (we return to this point later). Amplification of the modes is possible only if the phase speed of the vibration is sufficiently large, and our calculations show that the phase speed needs to reach at least

![]() $c\approx 300$

. Our calculations also show that vortices with wavenumbers in the interval

$c\approx 300$

. Our calculations also show that vortices with wavenumbers in the interval

![]() $\mu \approx 1{-}2$

seem to be the most likely to emerge.

$\mu \approx 1{-}2$

seem to be the most likely to emerge.

Figure 4. Variations of the amplification rate

![]() $\sigma _{i}$

as a function of the vortex wavenumber

$\sigma _{i}$

as a function of the vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu$

for selected flow Reynolds numbers

$\mu$

for selected flow Reynolds numbers

![]() $Re$

, wavenumber

$Re$

, wavenumber

![]() $\alpha$

, and wave phase speeds

$\alpha$

, and wave phase speeds

![]() $c$

.

$c$

.

The critical Reynolds number required for instability depends on both

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $c$

; typical results are depicted in figure 5(a). There is an absolute minimal phase speed required to produce instability – it is

$c$

; typical results are depicted in figure 5(a). There is an absolute minimal phase speed required to produce instability – it is

![]() $c=406.4,260.5,248.8,248.1$

for

$c=406.4,260.5,248.8,248.1$

for

![]() $\alpha =0.3,1,1.5,2$

. This minimal phase speed increases with the Reynolds number, as documented in figure 6. The results presented in figure 6 are for

$\alpha =0.3,1,1.5,2$

. This minimal phase speed increases with the Reynolds number, as documented in figure 6. The results presented in figure 6 are for

![]() $Re=980,1005,1230,1500$

, which are Reynolds numbers producing instability for the smallest

$Re=980,1005,1230,1500$

, which are Reynolds numbers producing instability for the smallest

![]() $c$

for

$c$

for

![]() $\alpha =0.3,1,1.5,2$

, respectively. There is no upper limit on the phase speed producing instability, but

$\alpha =0.3,1,1.5,2$

, respectively. There is no upper limit on the phase speed producing instability, but

![]() $Re_{cr}$

increases nearly linearly with

$Re_{cr}$

increases nearly linearly with

![]() $c$

at large values of

$c$

at large values of

![]() $c$

(see figure 5

a). It is clear that waves with phase speed

$c$

(see figure 5

a). It is clear that waves with phase speed

![]() $c\approx 300{-}500$

lead to the smallest

$c\approx 300{-}500$

lead to the smallest

![]() $Re_{cr}$

. The minimum

$Re_{cr}$

. The minimum

![]() $Re_{cr}$

depends on the wave wavelength, and it is

$Re_{cr}$

depends on the wave wavelength, and it is

![]() $Re_{cr}=884.6,737,1025.5,1298.5$

for

$Re_{cr}=884.6,737,1025.5,1298.5$

for

![]() $\alpha =0.3,1,1.5,2$

.

$\alpha =0.3,1,1.5,2$

.

Figure 5. Variations of (a) the critical Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{cr}$

, and (b) the critical wavenumber

$Re_{cr}$

, and (b) the critical wavenumber

![]() $\mu$

, as functions of the wave phase speed

$\mu$

, as functions of the wave phase speed

![]() $c$

for the wave with amplitude

$c$

for the wave with amplitude

![]() $A=0.06$

and selected wavenumbers

$A=0.06$

and selected wavenumbers

![]() $\alpha$

. The vertical dotted lines in (a) show the minimum wave speed required to initiate the instability. The horizontal dotted lines show the minimum critical Reynolds number

$\alpha$

. The vertical dotted lines in (a) show the minimum wave speed required to initiate the instability. The horizontal dotted lines show the minimum critical Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{cr}$

for all phase speeds

$Re_{cr}$

for all phase speeds

![]() $c$

.

$c$

.

Figure 6. Variations of the amplification rate

![]() $\sigma _{i}$

as a function of the phase speed

$\sigma _{i}$

as a function of the phase speed

![]() $c$

for waves with amplitude

$c$

for waves with amplitude

![]() $A=0.06$

and (a)

$A=0.06$

and (a)

![]() $(\alpha ,Re)=(0.3,980)$

, (b)

$(\alpha ,Re)=(0.3,980)$

, (b)

![]() $(\alpha ,Re)=(1,1005)$

, (c)

$(\alpha ,Re)=(1,1005)$

, (c)

![]() $(\alpha ,Re)=(1.5,1230)$

, (d)

$(\alpha ,Re)=(1.5,1230)$

, (d)

![]() $(\alpha ,Re)=(2,1500)$

.

$(\alpha ,Re)=(2,1500)$

.

The vortex properties corresponding to critical conditions exhibit complex behaviour. In general,

![]() $\mu _{cr}$

increases with an increase of

$\mu _{cr}$

increases with an increase of

![]() $\alpha$

. Variations of

$\alpha$

. Variations of

![]() $\mu _{cr}$

as a function of

$\mu _{cr}$

as a function of

![]() $c$

exhibit a local minimum around

$c$

exhibit a local minimum around

![]() $c\approx 400$

for all

$c\approx 400$

for all

![]() $\alpha$

; however, an increase of

$\alpha$

; however, an increase of

![]() $c$

away from this minimum leads to an increase of

$c$

away from this minimum leads to an increase of

![]() $\mu _{cr}$

for midrange

$\mu _{cr}$

for midrange

![]() $\alpha$

(

$\alpha$

(

![]() $\alpha =1,1.5)$

and a decrease for small (

$\alpha =1,1.5)$

and a decrease for small (

![]() $\alpha =0.3)$

and large (

$\alpha =0.3)$

and large (

![]() $\alpha =2$

) values, as illustrated in figure 5(b).

$\alpha =2$

) values, as illustrated in figure 5(b).

The fact that the wave is required to have a certain minimum phase speed before it can destabilise the flow is further illustrated in figure 6. Here, it is seen that a small increase of

![]() $c$

above its minimum value leads to a relatively rapid increase in the amplification rate, and a significant widening in the vortex wavenumber

$c$

above its minimum value leads to a relatively rapid increase in the amplification rate, and a significant widening in the vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu$

range that is unstable. One may speculate that once the flow becomes susceptible to this form of instability, a wide range of vortex sizes may plausibly emerge.

$\mu$

range that is unstable. One may speculate that once the flow becomes susceptible to this form of instability, a wide range of vortex sizes may plausibly emerge.

The next two figures concern the structure of the curves that identify neutrally stable modes. First, figure 7 shows the form of these curves in the

![]() $(\mu , Re)$

-plane for a selection of vibration wavenumbers

$(\mu , Re)$

-plane for a selection of vibration wavenumbers

![]() $\alpha$

; the companion plot in figure 8 displays similar data but for a few phase speeds

$\alpha$

; the companion plot in figure 8 displays similar data but for a few phase speeds

![]() $c$

.

$c$

.

Figure 7. Neutral curves in the

![]() $(\mu ,Re)$

-plane for

$(\mu ,Re)$

-plane for

![]() $A=0.06$

and (a)

$A=0.06$

and (a)

![]() $\alpha =1$

, (b)

$\alpha =1$

, (b)

![]() $\alpha =1.5$

, (c)

$\alpha =1.5$

, (c)

![]() $\alpha =2$

. Stars identify the critical Reynolds number

$\alpha =2$

. Stars identify the critical Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{cr}$

and the critical vortex wavenumber

$Re_{cr}$

and the critical vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu _{cr}$

.

$\mu _{cr}$

.

Figure 8. Neutral curves in the

![]() $(\mu ,Re)$

-plane for

$(\mu ,Re)$

-plane for

![]() $A=0.06$

and (a)

$A=0.06$

and (a)

![]() $c=300$

, (b)

$c=300$

, (b)

![]() $c=400$

, (c)

$c=400$

, (c)

![]() $c=500$

. Stars identify the critical Reynolds number

$c=500$

. Stars identify the critical Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{cr}$

and the critical vortex wavenumber

$Re_{cr}$

and the critical vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu _{cr}$

.

$\mu _{cr}$

.

Figure 9. (a) Neutral curves in the

![]() $(\mu ,Re)$

-plane for different

$(\mu ,Re)$

-plane for different

![]() $A$

values. Stars identify the critical Reynolds number

$A$

values. Stars identify the critical Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{cr}$

and the critical vortex wavenumber

$Re_{cr}$

and the critical vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu _{cr}$

. (b) Variations of the critical Reynolds number

$\mu _{cr}$

. (b) Variations of the critical Reynolds number

![]() $Re_{cr}$

as a function of wave amplitude

$Re_{cr}$

as a function of wave amplitude

![]() $A$

. All results are for

$A$

. All results are for

![]() $\alpha =1.5,\ c=500$

.

$\alpha =1.5,\ c=500$

.

Given a certain wave speed, there is the most effective wavenumber leading to the lowest

![]() $Re_{cr}$

. When

$Re_{cr}$

. When

![]() $c=300,400,500$

, the most effective

$c=300,400,500$

, the most effective

![]() $\alpha$

is always

$\alpha$

is always

![]() $\alpha \approx 0.7,$

leading to

$\alpha \approx 0.7,$

leading to

![]() $Re_{cr}=680,700,790$

, respectively (see figure 8), producing vortices with similar wavenumbers, i.e.

$Re_{cr}=680,700,790$

, respectively (see figure 8), producing vortices with similar wavenumbers, i.e.

![]() $\mu \approx 0.75$

. When

$\mu \approx 0.75$

. When

![]() $\alpha =1,1.5,2$

, there is the most effective phase speed, and it is

$\alpha =1,1.5,2$

, there is the most effective phase speed, and it is

![]() $c=350,350,300$

for

$c=350,350,300$

for

![]() $\alpha =1,1.5,2$

, with critical vortex wavenumber

$\alpha =1,1.5,2$

, with critical vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu _{cr}\approx 0.85,1.2,1.85$

, respectively (see figure 7). All these data demonstrate the existence of the most effective wavenumber and wave phase speed leading to the smallest

$\mu _{cr}\approx 0.85,1.2,1.85$

, respectively (see figure 7). All these data demonstrate the existence of the most effective wavenumber and wave phase speed leading to the smallest

![]() $Re_{cr}$

.

$Re_{cr}$

.

We deduce from figures 5 and 6 that small changes in the vibration wave characteristics can significantly alter the corresponding

![]() $Re_{cr}$

. The resulting vortex size, as measured by

$Re_{cr}$

. The resulting vortex size, as measured by

![]() $\mu _{cr}$

, changes only marginally with

$\mu _{cr}$

, changes only marginally with

![]() $c$

, but is much more sensitive to the precise value of

$c$

, but is much more sensitive to the precise value of

![]() $\alpha$

.

$\alpha$

.

The effects of the changes in the wave amplitude are considered in figure 9. The critical Reynolds number decreases with larger vibrations

![]() $A$

, and seems to grow proportional to

$A$

, and seems to grow proportional to

![]() $A^{-2/3}$

as

$A^{-2/3}$

as

![]() $A\rightarrow0$

. It would be interesting to show theoretically that this is indeed the case, but such detailed asymptotic work is deferred to later study.

$A\rightarrow0$

. It would be interesting to show theoretically that this is indeed the case, but such detailed asymptotic work is deferred to later study.

Figure 10. Zones of instability (marked in green) in the

![]() $(\alpha{,}c)$

-plane for the wave amplitude

$(\alpha{,}c)$

-plane for the wave amplitude

![]() $A=0.06$

. The background shows variations in the normalised force correction

$A=0.06$

. The background shows variations in the normalised force correction

![]() $F_{norm}={F_{1,B}}/({Re\,F_{0}A^{2}})$

; the grey shading indicates negative

$F_{norm}={F_{1,B}}/({Re\,F_{0}A^{2}})$

; the grey shading indicates negative

![]() $F_{norm}$

, while the red line shows

$F_{norm}$

, while the red line shows

![]() $F_{norm}=0$

.

$F_{norm}=0$

.

All the information relating to the instability can be combined to give an overall picture of the flow characteristics. The results in figure 10 include convincing evidence that only subcritical waves can produce vortex instability. The range of wave phase speeds leading to destabilisation expands as

![]() $Re$

grows; however, they are always subcritical and cannot propagate against the flow. As the range of phase speeds expands, so too does the interval of vibration wavenumbers. Of particular interest in connection with figure 10 is the region of parameter space where the green- and grey-shaded zones overlap. Those pairs of

$Re$

grows; however, they are always subcritical and cannot propagate against the flow. As the range of phase speeds expands, so too does the interval of vibration wavenumbers. Of particular interest in connection with figure 10 is the region of parameter space where the green- and grey-shaded zones overlap. Those pairs of

![]() $\alpha$

and

$\alpha$

and

![]() $c$

that lie in this common zone identify vibration waves that can reduce flow losses while simultaneously creating vortices through destabilisation. These waves are obviously of great interest in mixed intensification.

$c$

that lie in this common zone identify vibration waves that can reduce flow losses while simultaneously creating vortices through destabilisation. These waves are obviously of great interest in mixed intensification.

5.1. Disturbance properties and instability characteristics

We will now probe the disturbance properties and instability characteristics in greater detail. We begin with figure 11, which displays the disturbance spectra that identify the unstable modes. These modes have zero frequency, demonstrating that they do not propagate and can be identified as streamwise vortices. They can be connected to the Squire spectrum in the infinitesimal amplitude limit

![]() $A\rightarrow 0,$

as demonstrated by the data shown in figure 12. Moreover, these results confirm that wave amplitude

$A\rightarrow 0,$

as demonstrated by the data shown in figure 12. Moreover, these results confirm that wave amplitude

![]() $A$

must exceed a certain minimum size before instability may occur, and that there is a finite range of wave phase speeds

$A$

must exceed a certain minimum size before instability may occur, and that there is a finite range of wave phase speeds

![]() $c$

over which the flow is destabilised.

$c$

over which the flow is destabilised.

Figure 11. Spectra for

![]() $Re=1000$

,

$Re=1000$

,

![]() $A=0.08$

,

$A=0.08$

,

![]() $\alpha =0.7$

,

$\alpha =0.7$

,

![]() $\mu =0.7$

,

$\mu =0.7$

,

![]() $\delta =0.$

The labels OS and Squire identify the Orr–Somerfield and Squire modes.

$\delta =0.$

The labels OS and Squire identify the Orr–Somerfield and Squire modes.

Figure 12. Variations of the amplification rate

![]() $\sigma _{i}/Re$

(a) as a function of the wave amplitude

$\sigma _{i}/Re$

(a) as a function of the wave amplitude

![]() $A$

, and (b) as a function of the wave phase speed

$A$

, and (b) as a function of the wave phase speed

![]() $c$

, for

$c$

, for

![]() $Re=1000$

,

$Re=1000$

,

![]() $\alpha =0.7$

,

$\alpha =0.7$

,

![]() $\mu =0.7$

,

$\mu =0.7$

,

![]() $\delta =0$

. The horizontal dashed line in (a) corresponds to the least attenuated Squire mode of Couette flow.

$\delta =0$

. The horizontal dashed line in (a) corresponds to the least attenuated Squire mode of Couette flow.

Figure 13. Distributions of the three leading (

![]() $n=0,1,2$

) eigenfunctions for the disturbance velocity components for the wave amplitude

$n=0,1,2$

) eigenfunctions for the disturbance velocity components for the wave amplitude

![]() $A=0.08$

, wavenumber

$A=0.08$

, wavenumber

![]() $\alpha =0.7$

, flow Reynolds number

$\alpha =0.7$

, flow Reynolds number

![]() $Re=1000$

, and vortex wavenumber

$Re=1000$

, and vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu =0.7$

.

$\mu =0.7$

.

Figure 14. (a) Distributions of mode zero

![]() $g_{u}^{(0)}$

of the x-component of the disturbance velocity vector, and (b) variations of the position

$g_{u}^{(0)}$

of the x-component of the disturbance velocity vector, and (b) variations of the position

![]() $y_{max}$

of the maximum of

$y_{max}$

of the maximum of

![]() $g_{u}^{(0)}$

as a function of the wave phase speed

$g_{u}^{(0)}$

as a function of the wave phase speed

![]() $c$

for the wave amplitude

$c$

for the wave amplitude

![]() $A=0.08$

, wavenumber

$A=0.08$

, wavenumber

![]() $\alpha =0.7$

, flow Reynolds number

$\alpha =0.7$

, flow Reynolds number

![]() $Re=1000,$

and vortex wavenumber

$Re=1000,$

and vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu =0.7$

. Thin dotted vertical lines in (b) show the neutral stability conditions.

$\mu =0.7$

. Thin dotted vertical lines in (b) show the neutral stability conditions.

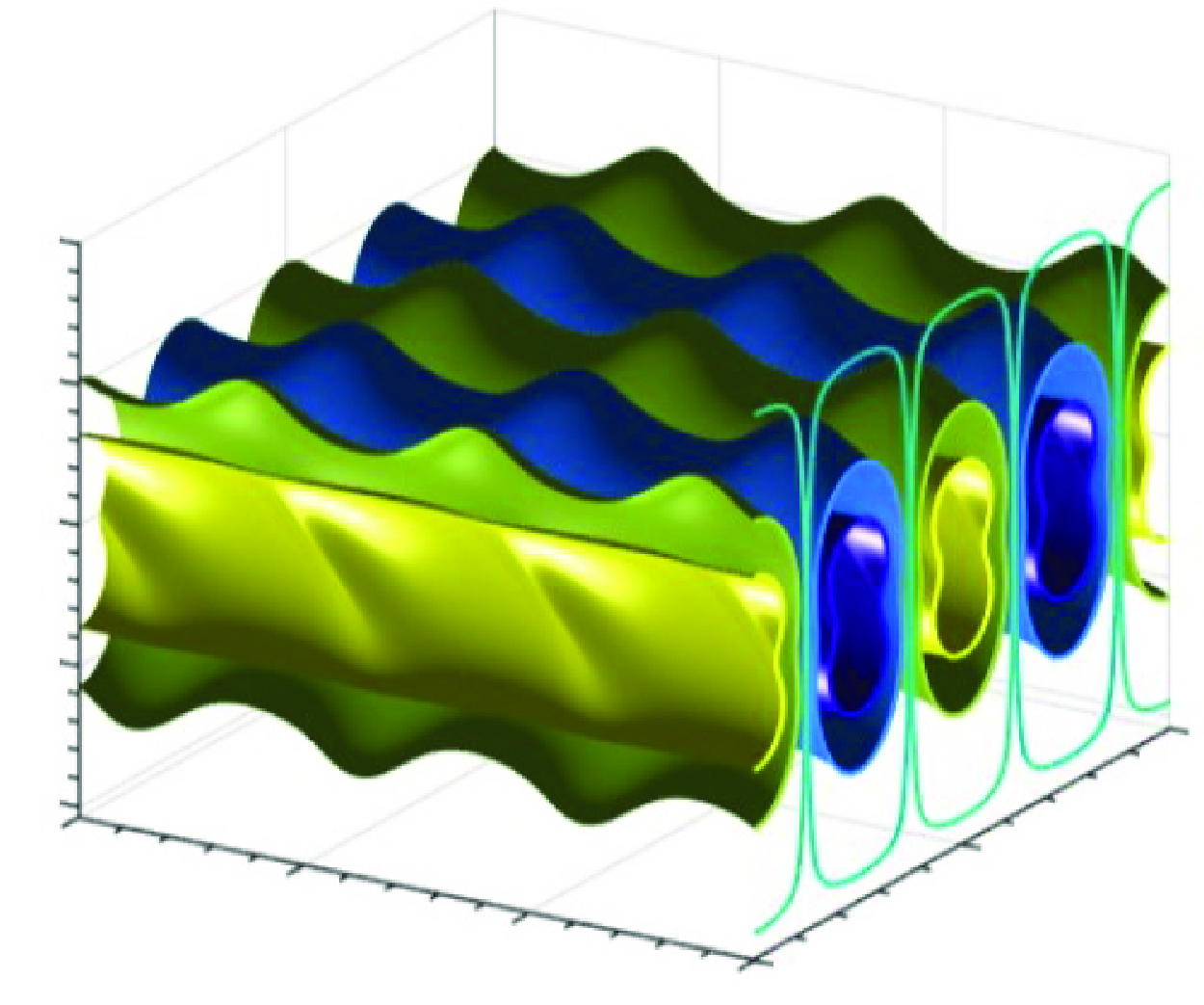

The topology of the disturbance velocity field can be inferred from the plots of eigenfunctions displayed in figure 13. This structure is characteristic of streamwise vortices in shear layers. Vibrations produce vortices in cross-planes, which transport low-speed fluid away from the wall (upwash) and high-speed fluid towards the wall (downwash), thereby creating longitudinal streaks (Floryan Reference Floryan1991). The disturbance velocity field is dominated by mode

![]() $n=0,$

representing the vortex motion, while higher-order modes represent streamwise modulation of this vortex. In particular, we note that the mode shapes

$n=0,$

representing the vortex motion, while higher-order modes represent streamwise modulation of this vortex. In particular, we note that the mode shapes

![]() $g_{u}^{(0)}$

and

$g_{u}^{(0)}$

and

![]() $g_{v}^{(0)}$

are purely real, and

$g_{v}^{(0)}$

are purely real, and

![]() $g_{w}^{(0)}$

is purely imaginary, while the remaining modes are complex. The rotational movement exhibited by

$g_{w}^{(0)}$

is purely imaginary, while the remaining modes are complex. The rotational movement exhibited by

![]() $v_{D}$

and

$v_{D}$

and

![]() $w_{D}$

is quite weak but is sufficient to result in a large defect in the streamwise velocity distribution. That this is the case is confirmed by the observation that the mode

$w_{D}$

is quite weak but is sufficient to result in a large defect in the streamwise velocity distribution. That this is the case is confirmed by the observation that the mode

![]() $g_{u}^{(0)}$

is roughly an order of magnitude larger than either

$g_{u}^{(0)}$

is roughly an order of magnitude larger than either

![]() $g_{v}^{(0)}$

or

$g_{v}^{(0)}$

or

![]() $g_{w}^{(0)}$

. The disturbance velocity field comprises two layers of vortices when

$g_{w}^{(0)}$

. The disturbance velocity field comprises two layers of vortices when

![]() $c=250$

(the first row in figure 13) and one layer when

$c=250$

(the first row in figure 13) and one layer when

![]() $c=500$

(the second row) but reverts to two layers again once

$c=500$

(the second row) but reverts to two layers again once

![]() $c=750$

(the third row). The structure of

$c=750$

(the third row). The structure of

![]() $g_{u}^{(0)}$

displayed in figure 14(a) illustrates these transitions as

$g_{u}^{(0)}$

displayed in figure 14(a) illustrates these transitions as

![]() $c$

increases. The maximum of

$c$

increases. The maximum of

![]() $g_{u}^{(0)}$

is close to the vibrating wall when the phase speed is small; the velocity field comprises two layers of vortices, and the flow is stable. As

$g_{u}^{(0)}$

is close to the vibrating wall when the phase speed is small; the velocity field comprises two layers of vortices, and the flow is stable. As

![]() $c$

increases, the principal zone of intense activity shifts towards the middle of the slot; the flow field now consists of only a single layer of vortices, and the flow is unstable. Further increase of

$c$

increases, the principal zone of intense activity shifts towards the middle of the slot; the flow field now consists of only a single layer of vortices, and the flow is unstable. Further increase of

![]() $c$

moves the activity zone towards the smooth plate; the flow field consists of two layers of vortices, and the flow becomes stable again. The change from one layer of vortices to two layers tends to increase the velocity gradients, enhancing the dissipation, and is conducive to flow stabilisation.

$c$

moves the activity zone towards the smooth plate; the flow field consists of two layers of vortices, and the flow becomes stable again. The change from one layer of vortices to two layers tends to increase the velocity gradients, enhancing the dissipation, and is conducive to flow stabilisation.

A characteristic flow field topology associated with unstable vortices is illustrated in figure 15. The structure of the disturbance velocity field corresponding to unstable vortices is independent of the wavenumber

![]() $\alpha$

(see figures 16

a,b). The centre of the vortex moves closer to the vibrating wall as

$\alpha$

(see figures 16

a,b). The centre of the vortex moves closer to the vibrating wall as

![]() $Re$

increases, and the disturbance velocity field eventually splits into two layers of vortices, with the primary vortex near the vibrating wall being directly driven by the instability (figures 16

c,d).

$Re$

increases, and the disturbance velocity field eventually splits into two layers of vortices, with the primary vortex near the vibrating wall being directly driven by the instability (figures 16

c,d).

Figure 15. Contour plot of the streamwise disturbance velocity component

![]() $u_{D}$

for the wave amplitude

$u_{D}$

for the wave amplitude

![]() $A=0.08$

, wavenumber

$A=0.08$

, wavenumber

![]() $\alpha =0.7$

, wave speed

$\alpha =0.7$

, wave speed

![]() $c=500$

, flow Reynolds number

$c=500$

, flow Reynolds number

![]() $Re=1000$

, and vortex wavenumber

$Re=1000$

, and vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu =0.7$

.

$\mu =0.7$

.

Figure 16. Distributions of mode zero

![]() $g_{u}^{(0)}$

of the x-component of the disturbance velocity vector, and variations of locations of their maxima, as functions of (a,b) the wavenumber

$g_{u}^{(0)}$

of the x-component of the disturbance velocity vector, and variations of locations of their maxima, as functions of (a,b) the wavenumber

![]() $\alpha$

, and (c,d) the Reynolds number

$\alpha$

, and (c,d) the Reynolds number

![]() $Re$

. All results are for the vortex wavenumber

$Re$

. All results are for the vortex wavenumber

![]() $\mu =0.7$

and the wave amplitude

$\mu =0.7$

and the wave amplitude

![]() $A=0.08$

.

$A=0.08$

.

Finally, we point out that the vortices‘ streaks are susceptible to instabilities (Park, Hwang & Cossu Reference Park, Hwang and Cossu2011). If these occur, then they may lead to either optimal roll structures that maximise the transient temporal growth of the streaks (Schmid & Henningson Reference Schmid and Henningson2001) or asymptotic growth in the form of normal modes leading to secondary instabilities (Floryan Reference Floryan1991).

6. Energy analysis

Further information concerning the properties of the flow can be gleaned by considering the form of the energy transfer between the base flow and the disturbances. To explore this, we can start with the field equations expressed in terms of primitive variables, i.e.

The variables are separated into the basic state plus the disturbances, so that

Substitution of (6.2) into (6.1) and linearisation show that

An appropriate mechanical energy functional can be constructed by taking the scalar product of the momentum equation with the disturbance velocity vector. The result is then integrated over a control volume that extends across the channel and over one wavelength in the x- and z-directions. This gives (in index notation)

\begin{align}&\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\!\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\!\left(\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left(v_{D,i}v_{D,i}\right)+{v_{D,i}}V_{B,j}\frac{\partial v_{D,i}}{\partial x_{j}}+v_{D,i}v_{D,j}\frac{\partial V_{B,i}}{\partial x_{j}}+v_{D,i}\frac{\partial p_{D}}{\partial x_{i}}\!\right){\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\quad=\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\left({\pmb\nabla} ^{2}v_{D,i}\right).v_{D,i}\, {\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y.\end{align}

\begin{align}&\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\!\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\!\left(\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left(v_{D,i}v_{D,i}\right)+{v_{D,i}}V_{B,j}\frac{\partial v_{D,i}}{\partial x_{j}}+v_{D,i}v_{D,j}\frac{\partial V_{B,i}}{\partial x_{j}}+v_{D,i}\frac{\partial p_{D}}{\partial x_{i}}\!\right){\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\quad=\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\left({\pmb\nabla} ^{2}v_{D,i}\right).v_{D,i}\, {\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y.\end{align}

The application of periodicity conditions and Green’s theorem leads to

\begin{align}&\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left(v_{D,i}v_{D,i}\right) {\rm d}x {\rm d}z {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\quad=-\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\frac{\partial v_{D,i}}{\partial x_{j}}\frac{\partial v_{D,i}}{\partial x_{j}}{\rm d}x {\rm d}z {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\qquad-\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}v_{D,i}v_{D,j}\frac{\partial V_{B,i}}{\partial x_{j}}{\rm }x {\rm d}z {\rm d}y\end{align}

\begin{align}&\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left(v_{D,i}v_{D,i}\right) {\rm d}x {\rm d}z {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\quad=-\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\frac{\partial v_{D,i}}{\partial x_{j}}\frac{\partial v_{D,i}}{\partial x_{j}}{\rm d}x {\rm d}z {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\qquad-\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}v_{D,i}v_{D,j}\frac{\partial V_{B,i}}{\partial x_{j}}{\rm }x {\rm d}z {\rm d}y\end{align}

where the factor

![]() $\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}$

is included to demonstrate that all quantities are evaluated per unit length in the x- and z-directions. The first term on the right-hand side of this balance describes dissipation, which is always positive, with the normalisation of the disturbance velocity field chosen to make this integral unity. The normalised energy relation then becomes

$\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}$

is included to demonstrate that all quantities are evaluated per unit length in the x- and z-directions. The first term on the right-hand side of this balance describes dissipation, which is always positive, with the normalisation of the disturbance velocity field chosen to make this integral unity. The normalised energy relation then becomes

\begin{align}&\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left(v_{D,i}v_{D,i}\right) \,{\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\quad=-1-\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}v_{D,i}v_{D,j}\frac{\partial V_{B,i}}{\partial x_{j}}\,{\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y.\end{align}

\begin{align}&\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left(v_{D,i}v_{D,i}\right) \,{\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y\nonumber\\&\quad=-1-\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}v_{D,i}v_{D,j}\frac{\partial V_{B,i}}{\partial x_{j}}\,{\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y.\end{align}

The left-hand side (

![]() $I_{kin}$

) denotes the rate of growth of kinetic energy of disturbances. This energy increases with time if the second term on the right-hand side, which captures the inertial effects (

$I_{kin}$

) denotes the rate of growth of kinetic energy of disturbances. This energy increases with time if the second term on the right-hand side, which captures the inertial effects (

![]() $I_{\textit{inertia}}$

), dominates over the dissipation. This occurs when

$I_{\textit{inertia}}$

), dominates over the dissipation. This occurs when

![]() $I_{\textit{inertia}}\lt -1$

. The identification of elements of the base flow responsible for the instability requires an explicit decomposition of the inertial integral so that

$I_{\textit{inertia}}\lt -1$

. The identification of elements of the base flow responsible for the instability requires an explicit decomposition of the inertial integral so that

\begin{align}I_{\textit{inertia}}&=\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\left(u_{D}u_{D}\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial x}+u_{D}v_{D}\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial y}+v_{D}u_{D}\frac{\partial v_{B}}{\partial x}+v_{D}v_{D}\frac{\partial v_{B}}{\partial y}\right)\nonumber\\&\quad\times {\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y=I_{1}+I_{2}+I_{3}+I_{4}.\end{align}

\begin{align}I_{\textit{inertia}}&=\lambda _{x}^{-1}\lambda _{z}^{-1}\int _{-1}^{1}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{z}}\int _{0}^{\lambda _{x}}\left(u_{D}u_{D}\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial x}+u_{D}v_{D}\frac{\partial u_{B}}{\partial y}+v_{D}u_{D}\frac{\partial v_{B}}{\partial x}+v_{D}v_{D}\frac{\partial v_{B}}{\partial y}\right)\nonumber\\&\quad\times {\rm d}x\, {\rm d}z\, {\rm d}y=I_{1}+I_{2}+I_{3}+I_{4}.\end{align}

Integration in the x-direction was divided into two parts to enable easy identification of those contributions ascribed to effects of the downwelling and those corresponding to the upwelling parts of the wave. Some typical results are summarised in table 1. These demonstrate that

![]() ${\partial u_{B}}/{\partial y}$

combined with Reynolds stresses is mainly responsible for the energy transfer to the disturbances, with other terms having an almost negligible effect. The upwelling and downwelling parts of the wave contribute similar amounts to the energy transfers. The inertial terms have insufficient strength to overcome dissipation when

${\partial u_{B}}/{\partial y}$

combined with Reynolds stresses is mainly responsible for the energy transfer to the disturbances, with other terms having an almost negligible effect. The upwelling and downwelling parts of the wave contribute similar amounts to the energy transfers. The inertial terms have insufficient strength to overcome dissipation when

![]() $c=250$

and

$c=250$

and

![]() $c=750$

, but can do it when

$c=750$

, but can do it when

![]() $c=500$

. When this happens, the Reynolds stress is responsible for the energy transfer.

$c=500$

. When this happens, the Reynolds stress is responsible for the energy transfer.

Table 1. Elements of the energy integral for

![]() $A=0.08,\ Re=1000,\ \alpha =0.7,\ \mu =0.07$

.

$A=0.08,\ Re=1000,\ \alpha =0.7,\ \mu =0.07$

.

A qualitative analysis of the energy transfers aids insight into the flow dynamics. The reference flow dominates the primary state as the vibration-created flow modifications are at least an order of magnitude smaller, as was seen in figure 3. This means that

The disturbance velocity field is dominated by mode zero, as portrayed in figure 13. This means that

Energy integrals

![]() $I_{1}, I_{3}, I_{4}$

can be neglected, and

$I_{1}, I_{3}, I_{4}$

can be neglected, and

![]() $I_{2}$

can be approximated as

$I_{2}$

can be approximated as

This integral must be sufficiently negative to enable growth in the disturbance energy. This is possible only if the x- and y-disturbance velocity components are out of phase, which indeed is the case as illustrated in the eigenfunctions displayed in figure 13. The phase difference between

![]() $u_{D}$

and

$u_{D}$

and

![]() $v_{D}$

can be explained with the help of the sketch displayed in figure 17. Vortex motions in the downwash zone have a negative

$v_{D}$

can be explained with the help of the sketch displayed in figure 17. Vortex motions in the downwash zone have a negative

![]() $v_{D}$

that brings high-velocity fluid closer to the lower plate and generates a positive

$v_{D}$

that brings high-velocity fluid closer to the lower plate and generates a positive

![]() $u_{D}$

. The product

$u_{D}$

. The product

![]() $v_{D} u_{D}$

is therefore negative, which is the necessary condition to maintain the instability.

$v_{D} u_{D}$

is therefore negative, which is the necessary condition to maintain the instability.

Figure 17. Sketch of the unstable fluid movement.

Experimental verification of the above predictions would be desired. Theoretically, at least, one could create well-controlled surface vibrations using a system of piezoelectric pistons turned on and off in a proper sequence to produce surface waves with the desired wavelength and phase speeds. However, this description is somewhat over-simplistic, for it should be recognised that many practical difficulties are associated with constructing such a system. Practical progress is likely to be slow.

7. Summary