1 Introduction

Strategy revision opportunities describe possibilities for players to change a strategy during the play of a repeated game. The role of strategy revision opportunities is somewhat of a conundrum for economists. From a theory perspective, strategy revision opportunities should not affect behaviour, since behaviour strategies, which allow full flexibility during the course of play, and mixtures over strategies chosen at the start of the game are seen as equivalent in games of perfect recall (Kuhn Reference Kuhn, Kuhn and Tucker1953; Aumann Reference Aumann, Dresher, Shapley and Tucker1964). Any revision a decision-maker may want to make to a strategy during the course of play can be encoded in a suitably specified mixed strategy as long as arbitrarily complex strategies are allowed. As soon as there is some limit to the complexity (number of states) of strategies, revision opportunities could become important.

While standard subgame perfect equilibria are unaffected by revision opportunities, there are two types of considerations that can give some role to revision opportunities. One such refinement is renegotiation proofness. While renegotiation proofness implies that revision opportunities cannot increase collusion—since with revision opportunities players may not be able to credibly commit to the required punishment paths—weak renegotiation proofness, for example, has no bite in oligopoly games (Farrell Reference Farrell, Myles and Hammond2000; Aramendia et al. Reference Aramendia, Larrea and Ruiz2005). Another consideration is miscoordination, which could play an important role given the large number of possible equilibria in indefinitely repeated oligopoly games.

In this paper we conduct a laboratory experiment to study the impact of strategy revision opportunities on strategy choices and levels of collusion. This experimental approach enables us to elicit information about the strategies participants use in the repeated game, allowing us to identify strategy revisions and observe intended behavior off the realized outcome path. Such data is crucial to understand the mechanisms through which revision opportunities affect collusive behavior, and typically would be impossible to obtain from field data. Our experiment systematically varies revision opportunities across treatments, while keeping other factors such as the timing of moves, the available strategy sets, the size of the stakes, the number of players and the incentives to deviate or cooperate constant.

In the experiment, participants play an indefinitely repeated game where the stage game is either a game of strategic substitutes or of strategic complements. The stage games are derived from linear duopoly games (Cournot and Bertrand, respectively) and reduced to symmetric, normal-form games in which both players have four actions to choose from. The demand systems and action sets are chosen so that the resulting payoff matrices are as close as possible: they have identical diagonal elements (including the collusion and Nash outcomes), as well as identical temptation and sucker payoffs. The games primarily differ in the location of the (myopic) best response to collusion. In the substitutes game, the best response to collusion is less cooperative than the Nash action, while in the complements game it is more cooperative than the Nash action.

At the beginning of a supergame, participants program a strategy by choosing an initial action choice and a dynamic response machine, which specifies a recommended action in response to their rival’s previous action choice. Three treatment variations change the degree to which strategy revisions are possible. These variations are labeled the baseline, unilateral and bilateral variations. In the baseline treatment participants cannot change their dynamic response machine; that is, they lack revision possibilities. Under the unilateral variation, unilateral changes are possible, while under the bilateral variation mutual consent is required to change one’s dynamic response. The unilateral variation allows for full revision opportunities, while the bilateral variation is designed to mimic orchestrated revisions, such as those covered by renegotiation theory. In all variations, participants can deviate from their recommendation using one-shot deviations—these deviations come at a small cost.Footnote 1 A machine revision allows participants to economize on such costs in future choices.

We find that the existence of revision opportunities has no effect on cooperation under strategic substitutes, yet has a significant, positive effect under strategic complements. The second effect is large enough to reverse the ranking of collusion rates between interaction types: there is more cooperation under strategic substitutes if revision possibilities are absent, while the opposite is true if unilateral revisions are possible. Neither standard risk dominance nor considerations of renegotiation can explain these results. Given the large multiplicity of equilibria in these games, it is intuitive that fear of miscoordination might play an important role. We define a notion of “fear of miscoordination”, based on minmax regret, and show that it yields predictions consistent with our main results on the effect of revision opportunities.

Our paper contributes mainly to two literatures: (1) literature on strategy revision opportunities and (2) the literature on cooperation in games of strategic substitutes and complements.

There is not much research on strategy revision opportunities per se, but there is some experimental literature on cooperation/collusion that explicitly investigates the role of communication and renegotiation. Fonseca and Normann (Reference Fonseca and Normann2012), Andersson and Wengström (Reference Andersson and Wengström2012) or Cooper and Kühn (Reference Cooper and Kühn2014), for example, study renegotiation with communication and find mixed results as to whether communication, and the timing of communication, leads to more collusion or not. Our setting and results provide insight into renegotiation when explicit communication is not possible.Footnote 2

A seminal study on cooperation in games of strategic substitutes and complements was conducted by Potters and Suetens (Reference Potters and Suetens2009). They find more cooperation when actions exhibit strategic complementarities. As all their treatments are within a framework of behavior strategies, their results are best compared to our unilateral variations where strategy revision is possible. Our results with strategy revision opportunities confirm theirs. However, without revision opportunities, we find the opposite is true: there is more collusion with strategic substitutes. We discuss the intuition behind these differences in detail in Sect. 4.

Finally, our results also relate to the experimental literature on indefinitely repeated games. Usually this literature either elicits strategies without revision possibilities (Selten et al. Reference Selten, Mitzkewitz and Uhlich1997; Dal Bó and Fréchette Reference Dal Bó and Fréchette2017) or lets subjects play the game in a “hot” setting without eliciting strategies (Dal Bó Reference Dal Bó2005; Casari and Camera Reference Casari and Camera2009). Our results show that which setting is chosen can potentially affect behavior, at least when the game is one of strategic complements. One exception is Mengel and Peeters (Reference Mengel and Peeters2011), who have a “semi-hot” treatment (hot but with small costs) and a treatment without revision opportunities in a study comparing contributions by partners and strangers in a repeated public good game. Their setting is not suitable to study strategy revisions, however, since, although participants are allowed to deviate from pre-programmed strategies in some treatments, they are not allowed to revise strategies.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 outlines the experimental design and experimental procedures. Section 3 establishes our primary empirical results, in particular that revision opportunities have a positive effect under strategic complements and that this effect is large enough to reverse the ranking of collusion rates between the interaction types. Section 4 provides a discussion of the alternative explanations for our results, and formalises the concept of fear of miscoordination. A final section concludes.

2 The experiment

Designing experiments to understand strategic behaviour in indefinitely repeated games has two principal challenges. The first is the well-known theoretical problem of characterising the entire set of equilibrium strategies. The second concerns the complexity to directly elicit strategies due to the size and complexity of the strategy space, and constraints on participants’ time, cognitive abilities and experience. Related to this second challenge, the existing experimental literature has usually limited the strategy space considerably in order to do so (Dal Bó and Fréchette Reference Dal Bó and Fréchette2017). Such an approach has clear consequences for studying strategy revision opportunities since, under a restricted strategy space, the equivalence of behaviour and mixed strategies can break down. On the other hand, the impossibility to encode everything into a mixed strategy is one of the primary reasons why revision opportunities may matter in many real-life situations of interest.

Our design resolves these tensions by restricting participants to program a unit-recall dynamic response, but allowing them to deviate from the action proposed by the response to make available the full strategy space in all treatments. The experiment then studies revision opportunities in a

![]() design with three levels of strategy revision opportunities and two types of strategic interaction.

design with three levels of strategy revision opportunities and two types of strategic interaction.

2.1 Design

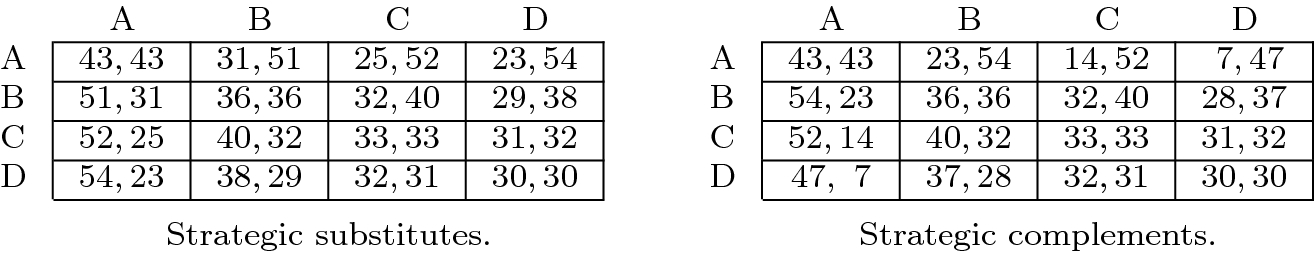

The two stage games. Participants play one of two possible games in Fig. 1 that differ in the type of strategic interaction: strategic substitutes or strategic complements. Payoffs are in experimental currency units (ECU), which are converted to Euros at the end of the experiment.

Fig. 1 The two stage games in the experiment

The structure and payoffs of the games are designed so that, while each game has a natural duopoly analogue, the two are as identical as possible. To provide this analogue, the substitutes game is a discretized version of a differentiated-goods linear Cournot duopoly and the complements game is a discretized version of a differentiated-goods linear Bertrand duopoly. In both cases, the duopolists produce differentiated-goods that are product substitutes. To ensure a fair comparison across games, the underlying duopoly games were calibrated so that the majority of payoffs for key action pairs are identical across games:

1. the Nash equilibrium payoffs (

) that result from both players playing action C are identical.

) that result from both players playing action C are identical.2. the joint payoff maximizing payoffs (

) that result from both choosing action A are identical.

) that result from both choosing action A are identical.3. the optimal deviation against the co-player playing action A, which requires playing action B in the complements game and action D in the substitutes game, yields the same payoff (

) for the defector and the sucker across games.

) for the defector and the sucker across games.4. the remaining actions in the games, action D for the complements game and action B for the substitutes game, are such that all diagonal elements are identical across games.Footnote 3

Sustaining cooperation via trigger strategies requires

to be satisfied. All the payoff parameters involved in this inequality are the same for both our complements and substitutes variations.Footnote 4 As a consequence of these choices, the minimal discount factor needed to sustain collusion via trigger strategies is the same in both games (

![]() ) and the chosen continuation probability of

) and the chosen continuation probability of

![]() is above this level.

is above this level.

The crucial difference between the two games is the location of the optimal deviation against the co-player playing the joint payoff maximizing action, which is action B with strategic complements and action D with strategic substitutes. For convenience, we will refer to the actions A, B, C and D as respectively Collusion, Dev.SC, Nash and Dev.SS.

Repeated game strategies. At the beginning of a repeated game, participants are asked to specify an intended strategy. This strategy consists of an initial action, to be played in the first stage, and a programmed machine, which recommends at each later stage an action conditional on their co-player’s action in the previous stage. The machine is denoted by a quadruple

![]() specifying which action

specifying which action

![]() the machine is programmed to play if the opponent has chosen action

the machine is programmed to play if the opponent has chosen action

![]() in the previous stage. An intended strategy is denoted by

in the previous stage. An intended strategy is denoted by

![]() , where the first element refers to the initial action choice.

, where the first element refers to the initial action choice.

The most general strategy one can formulate in a repeated game maps any possible history of observed action profiles into actions. In this design, however, participants’ intended strategies are restricted so that actions can only be conditioned on their co-player’s action in the previous stage. Some examples of familiar strategies that can be programmed are: unconditional cooperation (A–AAAA), tit-for-tat (A–ABCD), (forgiving) Nash reversion (A–ACCC), and always Nash (C–CCCC). Also strategies such as myopic best responses can be programmed. A well-known machine that cannot be programmed is grim-trigger. The ACCC-machine that comes closest implements a forgiving grim-trigger; that is, it reverts to cooperation if the opponent chooses to cooperate in some stage following a deviation.

While the focus is on simple strategies with few states and hence lower complexity, we allow participants to play other strategies as well. In particular, in all treatments participants are allowed to take an action that differs from the one recommended by their machine. Such changes are referred to as one-shot deviations. Consequently, more general strategies, such as grim-trigger, become feasible to implement via one-shot deviations.Footnote 5 These trigger strategy can be used to sustain collusion for all discount rates above the

![]() calculated earlier for the standard repeated game (i.e. just action choices in each period).Footnote 6

calculated earlier for the standard repeated game (i.e. just action choices in each period).Footnote 6

To provide participants with an incentive to program their machines (strategies) carefully, one-shot deviations are costly. Each one-shot deviation costs 3 ECU. Hence, we expect participants to rely mostly on unit recall strategies. However, if participants have strong enough preferences to choose another strategy, the full strategy space is available for participants in all treatments.

Revision opportunities. There are no revision opportunities in the treatments labeled baseline. Here, participants keep their machines for the entire duration of the repeated game, and can only deviate from the recommendations of their machines via one-shot deviations. In the unilateral treatments strategy revisions are possible. Participants can modify their machines after any stage of the repeated game.

To provide participants with an incentive to program their machines (strategies) carefully, machine modifications also have a small cost associated with them. In particular each machine modification costs 1 ECU, irrespective of the number of elements of the machine that are changed. Choosing the costs in such a manner we hoped to ensure that playing with a poorly programmed strategy is more costly in the baseline (where one needs to rely on one-shot deviations) than with unilateral revision opportunities (where machine changes are possible).

Again, collusive equilibria can be supported for all discount rates above

![]() using the same trigger strategy (A–ACCC) as in the baseline, which only relies on one-shot deviations to ensure permanent Nash reversion—see Section B.3 of the supplementary materials for further details.Footnote 7 Under the third variation—labeled bilateral—participants can modify their machines if and only if consent to a modification has been given by their opponent.

using the same trigger strategy (A–ACCC) as in the baseline, which only relies on one-shot deviations to ensure permanent Nash reversion—see Section B.3 of the supplementary materials for further details.Footnote 7 Under the third variation—labeled bilateral—participants can modify their machines if and only if consent to a modification has been given by their opponent.

2.2 Procedures

The experiment was conducted in the BEElab at Maastricht University during October–December 2011. 288 students were recruited using ORSEE (Greiner Reference Greiner2015) and participated in one of the six treatments.Footnote 8 For each of our treatments we have six independent observations. During each session, three matching groups were run in parallel on separate z-Tree servers (Fischbacher Reference Fischbacher2007). Sessions lasted an hour and a half on average, including a twenty minute instruction period. On average participants earned between 12.60 and 15.30 Euro for their participation.

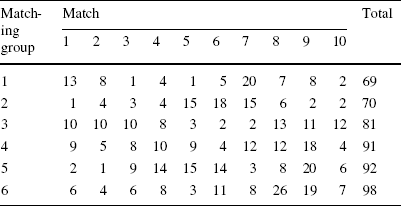

For each treatment six matching groups were run. Each matching group comprised eight participants that all played the repeated game (of the same treatment) ten times. At the beginning of a match, as a single repeated game is referred to, participants within a matching group were randomly paired. At the end of a session, participants were paid in cash according to the amount of ECUs they earned in one randomly drawn match. Table 2 gives the number of observations for each treatment.

Participants were fully informed about all details of the decision task, the environment and procedures in the experimental instructions (see Section C of the supplementary materials for an example of the instructions). Participants were never informed of the machine employed by other participants, but instead observed the history of play. That is, after every stage they were informed of their own action and the action of the person they were matched with, as well as the resulting payoffs.

For all members in a matching group, any given match consisted of the same number of stages, but this number changed across matches. Across matching groups this sequence of match-lengths differed. However, to facilitate comparison between treatments, the sequences were generated at random upfront and the same sequences were used for the different matching groups of each treatment. Table 1 provides details on the sequence of match lengths for the different matching groups.

Table 1 Number of stages played in the ten matches for the six different matching groups

|

Matching group |

Match |

Total |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

||

|

1 |

13 |

8 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

20 |

7 |

8 |

2 |

69 |

|

2 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

15 |

18 |

15 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

70 |

|

3 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

13 |

11 |

12 |

81 |

|

4 |

9 |

5 |

8 |

10 |

9 |

4 |

12 |

12 |

18 |

4 |

91 |

|

5 |

2 |

1 |

9 |

14 |

15 |

14 |

3 |

8 |

20 |

6 |

92 |

|

6 |

6 |

4 |

6 |

8 |

3 |

11 |

8 |

26 |

19 |

7 |

98 |

3 Results

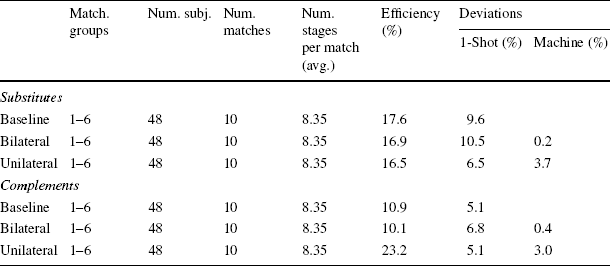

Table 2 provides a summary of the six treatments. In general participants had difficulty establishing more cooperative behavior, capturing on average less than

![]() of the potential gains from cooperating in all treatments. The treatments with strategic complements provided both the least and the most cooperative behavior, with low levels of cooperation in the baseline and bilateral treatments and high levels in the unilateral treatment. In all treatments, participants incurred very low costs for deviating from or modifying their machines. One-shot deviations are observed in less than 11% of stage games. In the unilateral treatments, machine modifications were implemented after less than 4% of stage games, while in the bilateral treatment (in which mutual agreement was required), machine modifications were made after less than 1% of stage games.

of the potential gains from cooperating in all treatments. The treatments with strategic complements provided both the least and the most cooperative behavior, with low levels of cooperation in the baseline and bilateral treatments and high levels in the unilateral treatment. In all treatments, participants incurred very low costs for deviating from or modifying their machines. One-shot deviations are observed in less than 11% of stage games. In the unilateral treatments, machine modifications were implemented after less than 4% of stage games, while in the bilateral treatment (in which mutual agreement was required), machine modifications were made after less than 1% of stage games.

Table 2 Summary of treatments

|

Match. groups |

Num. subj. |

Num. matches |

Num. stages per match (avg.) |

Efficiency (%) |

Deviations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1-Shot (%) |

Machine (%) |

||||||

|

Substitutes |

|||||||

|

Baseline |

1–6 |

48 |

10 |

8.35 |

17.6 |

9.6 |

|

|

Bilateral |

1–6 |

48 |

10 |

8.35 |

16.9 |

10.5 |

0.2 |

|

Unilateral |

1–6 |

48 |

10 |

8.35 |

16.5 |

6.5 |

3.7 |

|

Complements |

|||||||

|

Baseline |

1–6 |

48 |

10 |

8.35 |

10.9 |

5.1 |

|

|

Bilateral |

1–6 |

48 |

10 |

8.35 |

10.1 |

6.8 |

0.4 |

|

Unilateral |

1–6 |

48 |

10 |

8.35 |

23.2 |

5.1 |

3.0 |

![]() , where the stage game payoff is averaged over all matches and all stages. The column 1-shot deviations shows the percentage of stage games in which one-shot deviations were observed and the column “Machine” shows the percentage of stage games in which machine changes are observed

, where the stage game payoff is averaged over all matches and all stages. The column 1-shot deviations shows the percentage of stage games in which one-shot deviations were observed and the column “Machine” shows the percentage of stage games in which machine changes are observed

The majority of the subsequent analysis uses data from the last third of a session (matches 7–10). This sub-sample provides a reasonable trade-off between using the final matches, where subject behavior is most likely to have converged, and ensuring enough observations. Only when analysing the evolution of behavior across matches, or behavior in particular histories for which there is the need to expand the sample size, we increase the sub-sample to data from the last two-thirds of a session (matches 4–10). In terms of stages we use only data from stages twelve or earlier. The reason is that later stages did not exist in each match for each matching group (see Table 1). All reported regressions and statistical tests use cluster-robust standard errors, corrected for arbitrary correlation at the matching-group level (see Section E.3 of the supplementary materials for robustness checks using matching-group averages and non-parametric statistics).

3.1 Impact of revision opportunities on cooperation

We consider two measures of cooperation. The primary measure is the actual surplus generated over and above the one-shot Nash equilibrium as a percentage of the maximum available surplus (efficiency). This measure aggregates the impact of all choices, including partial collusion and deviation choices. The secondary measure focusses on just the percent of (full) collusion choices by subjects.

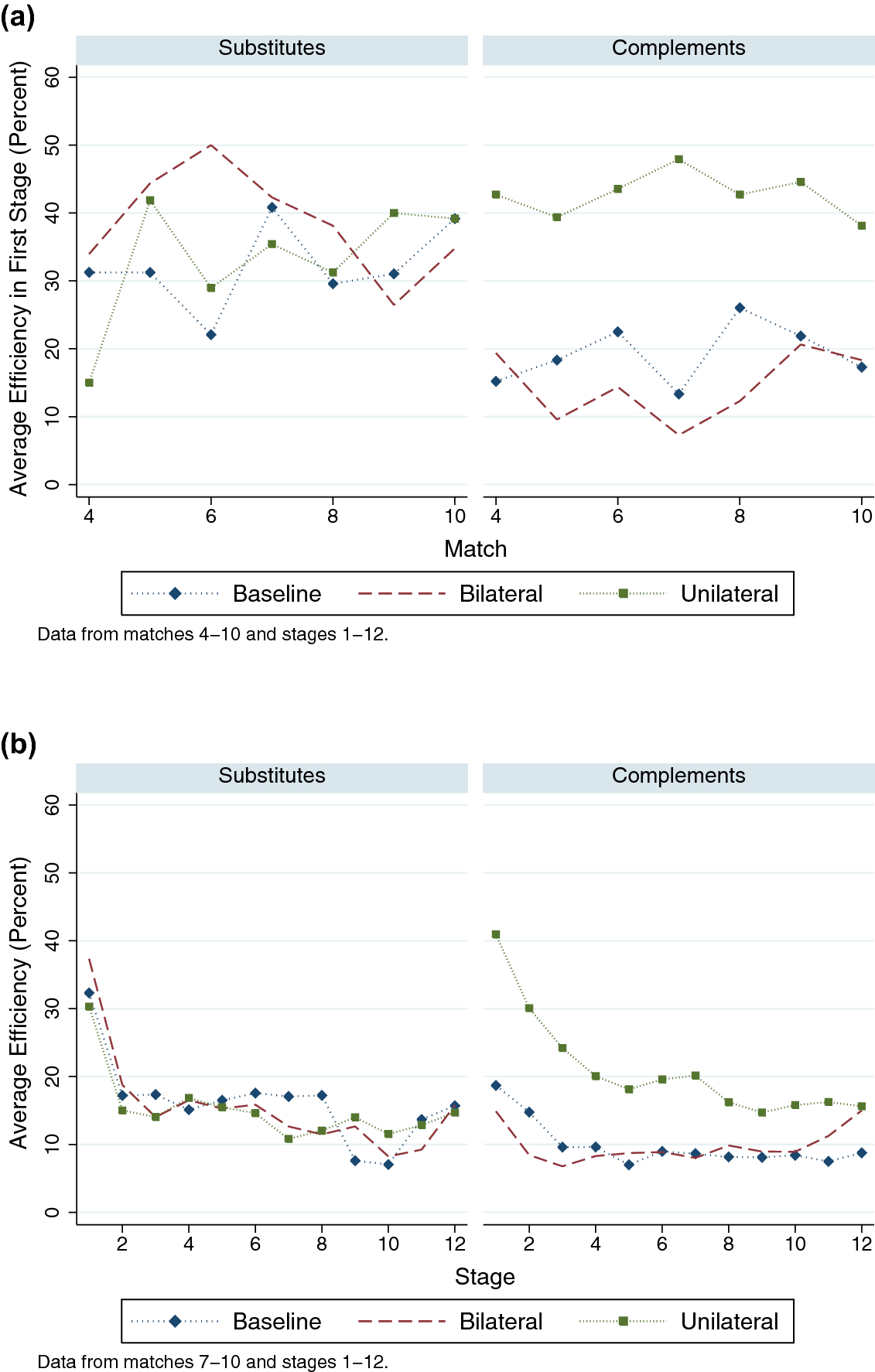

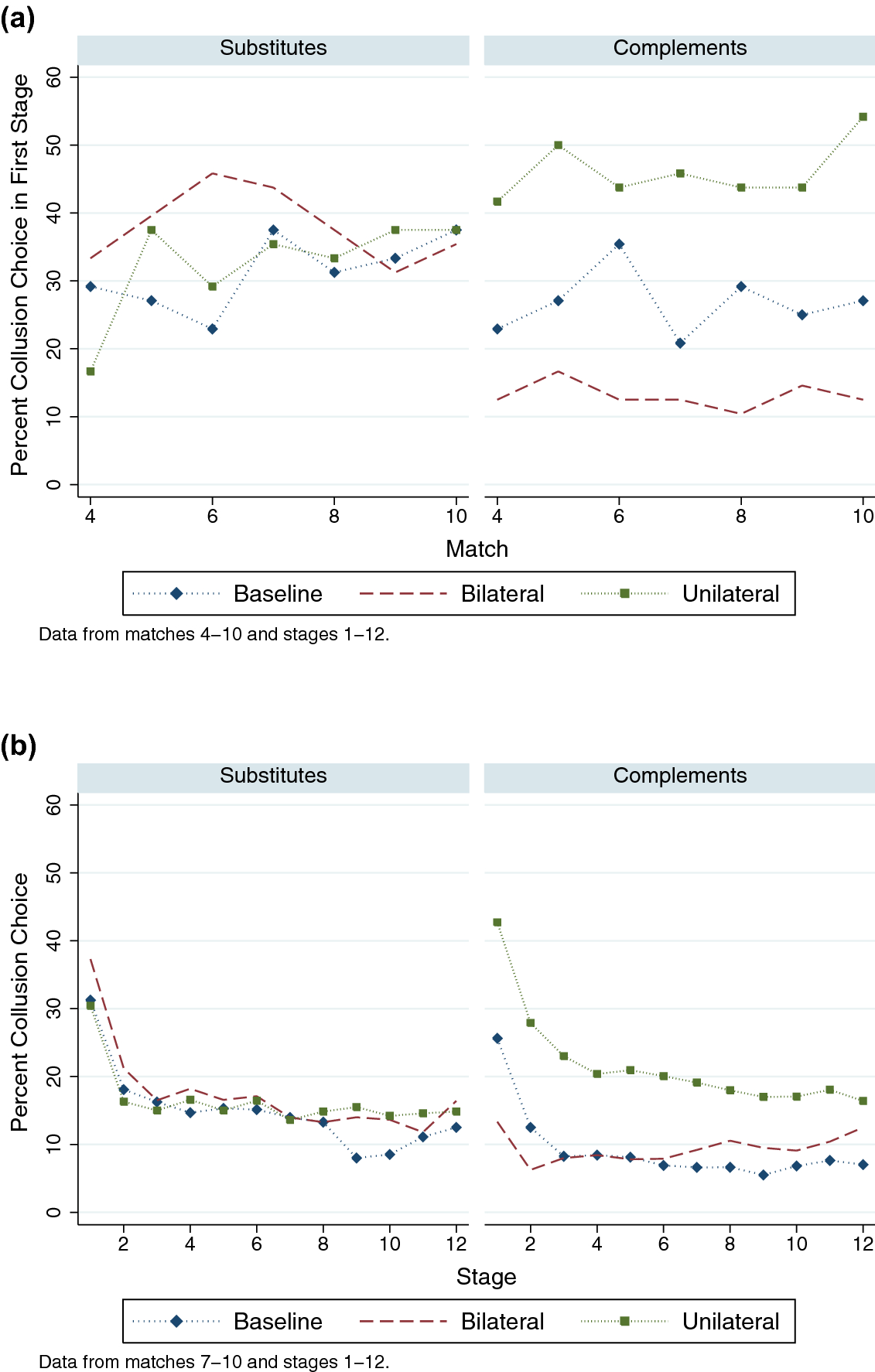

Figure 2 shows the evolution of efficiency both across matches and within matches. As can be seen, across matches (Panel a) revision opportunities do not seem to affect first-stage efficiency with strategic substitutes while there is a clear separation of the unilateral variation from the other two conditions with strategic complements. All treatments show the same pattern of decline of efficiency across stages within matches (Panel b).

Fig. 2 The effect of strategy revision opportunities on efficiency with strategic complements and substitutes. a Efficiency across matches. b Efficiency within matches

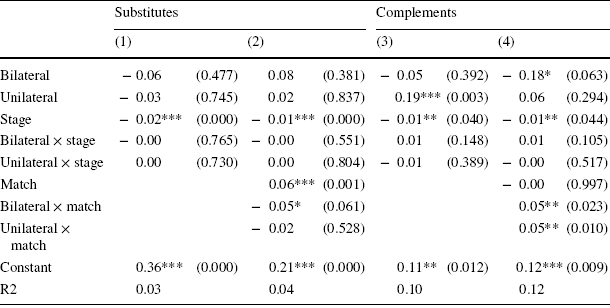

Table 3 Linear regression of payoff efficiency in the stage game

|

Substitutes |

Complements |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|||||

|

Bilateral |

− 0.06 |

(0.477) |

0.08 |

(0.381) |

− 0.05 |

(0.392) |

− 0.18* |

(0.063) |

|

Unilateral |

− 0.03 |

(0.745) |

0.02 |

(0.837) |

0.19*** |

(0.003) |

0.06 |

(0.294) |

|

Stage |

− 0.02*** |

(0.000) |

− 0.01*** |

(0.000) |

− 0.01** |

(0.040) |

− 0.01** |

(0.044) |

|

Bilateral × stage |

− 0.00 |

(0.765) |

− 0.00 |

(0.551) |

0.01 |

(0.148) |

0.01 |

(0.105) |

|

Unilateral × stage |

0.00 |

(0.730) |

0.00 |

(0.804) |

− 0.01 |

(0.389) |

− 0.00 |

(0.517) |

|

Match |

0.06*** |

(0.001) |

− 0.00 |

(0.997) |

||||

|

Bilateral × match |

− 0.05* |

(0.061) |

0.05** |

(0.023) |

||||

|

Unilateral × match |

− 0.02 |

(0.528) |

0.05** |

(0.010) |

||||

|

Constant |

0.36*** |

(0.000) |

0.21*** |

(0.000) |

0.11** |

(0.012) |

0.12*** |

(0.009) |

|

R2 |

0.03 |

0.04 |

0.10 |

0.12 |

||||

The baseline case is the baseline treatment. All regressions use data from matches 7–10 and stages 1–12 and include match-stage composition dummies. All regressions have 2352 observations across 18 matching groups (clusters). VCE clustered at the matching-group level. p values are reported in parentheses. ***1%, **5%, *10% significance

A linear regression on efficiency is used to formally quantify the effect of strategy revision opportunities and to understand statistical significance. Table 3 reports the results of this analysis separately for strategic substitutes and complements. In columns (1) and (3), a complete set of dummies for the various levels of revision opportunities is interacted with the stage number of the match.Footnote 9 This regression confirms the impression that strategy revision opportunities have no impact on rates of collusion under strategic substitutes, but have a significant impact under strategic complements. With strategic complements, the unilateral variation is associated with significantly higher rates of collusion (column (3)), while the baseline and bilateral variation have statistically similar rates. Note also that the R2 is substantially higher for the complements variation, arguably because revision opportunities can explain more of the observed variation in this setting.

Columns (2) and (4), expand the specification to include the match number as a dependent variable. Doing so reveals that strategy revision opportunities also work through the dynamics across matches. These regressions also show significant effects for the bilateral variation in the treatments with strategic complements. Here the mean is about the same as in the baseline but the dynamics are quite different, as can be seen in column (4). These patterns are most easily seen in Figure E.1 of the supplementary materials, which graphs the predicted efficiency from the linear regression.

Figure 3 shows the evolution of choices for the collusive action over time. Panel (a) shows this time trend across matches for choices in the first stage. With strategic substitutes (left panel), initial stage collusive choices are increasing over matches for the baseline and unilateral variations, while no clear trend is seen when bilateral consent is needed to modify machines. An obvious ranking of levels of revision opportunities, on the extent to which it generates collusion, cannot be made on the basis of this graph. With strategic complements (right panel), the graph illustrates a clear separation of treatments. Collusion rates are highest under unilateral. Under the baseline and bilateral variations, collusion rates are lower. There is a trend for collusion rates to increase over time in the unilateral treatment. However, no such trend is evident for the other treatments. Panel (b) of Fig. 3 shows how the rates of collusion change within a match. It displays the typical pattern of collusion decreasing sharply after the first few stages, then remaining approximately constant at a lower level. A logit regression using choice of action A as the dependent variable can be found in Table E.4 of the supplementary materials. The results of the logit regression show the same qualitative patterns in terms of treatment comparisons as the OLS regressions on efficiency shown in Table 3.

Fig. 3 The effect of strategy revision opportunities on collusion with strategic substitutes and complements: percentage of collusion. a Collusion choice across matches. b Collusion choice within matches

To sum up, we find that with strategic substitutes, strategy revision opportunities do not affect average collusion, while with strategic complements, strategy revision opportunities have a positive effect on collusion. This conclusion is based on the following Result:

Result 1

(1) Under strategic substitutes there is no treatment difference in average efficiency or collusion rates across the baseline, unilateral and bilateral variations. (2) Under strategic complements average efficiency as well as average collusion rates are higher under the unilateral compared to the other variations.

3.2 Difference between complements and substitutes

Strategy revision opportunities also affect the comparison between complements and substitutes. With fewer or no revision opportunities there is more collusion with strategic substitutes than with strategic complements: 35.2 versus 19.6% for first stage choice under the baseline variation (p value

![]() ), and 35.4 versus 14.6% under the bilateral variation (p value

), and 35.4 versus 14.6% under the bilateral variation (p value

![]() ).Footnote 10 However, with revision opportunities there is more collusion with strategic complements: 36.5 versus 43.5% (p value

).Footnote 10 However, with revision opportunities there is more collusion with strategic complements: 36.5 versus 43.5% (p value

![]() ) under the unilateral variation.

) under the unilateral variation.

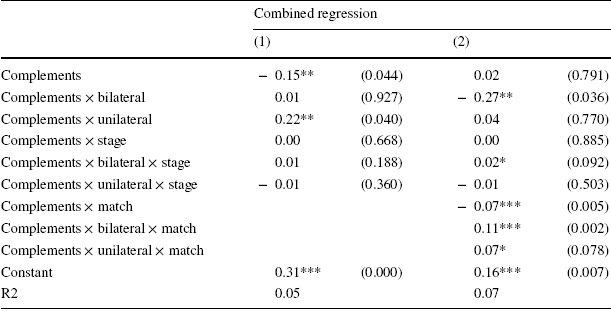

Table 4 Linear regression of payoff efficiency in the stage game—strategic substitutes versus complements

|

Combined regression |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) |

(2) |

|||

|

Complements |

− 0.15** |

(0.044) |

0.02 |

(0.791) |

|

Complements × bilateral |

0.01 |

(0.927) |

− 0.27** |

(0.036) |

|

Complements × unilateral |

0.22** |

(0.040) |

0.04 |

(0.770) |

|

Complements × stage |

0.00 |

(0.668) |

0.00 |

(0.885) |

|

Complements × bilateral × stage |

0.01 |

(0.188) |

0.02* |

(0.092) |

|

Complements × unilateral × stage |

− 0.01 |

(0.360) |

− 0.01 |

(0.503) |

|

Complements × match |

− 0.07*** |

(0.005) |

||

|

Complements × bilateral × match |

0.11*** |

(0.002) |

||

|

Complements × unilateral × match |

0.07* |

(0.078) |

||

|

Constant |

0.31*** |

(0.000) |

0.16*** |

(0.007) |

|

R2 |

0.05 |

0.07 |

||

The baseline case is the baseline treatment with strategic substitutes. All regressions use data from matches 7–10 and stages 1–12 and include match-stage composition dummies. Both regressions have 4704 observations across 18 matching groups (clusters). VCE clustered at the matching-group level. p-values are reported in parentheses. ***1%, **5%, *10% significance. The table reports just the results for regressors involving the complements dummy variable plus the constant term; see Table E.5 of the supplementary materials for the complete output

This strategic interaction effect is further quantified using analogous regression specifications to those reported in Table 3, except the data from both game types are pooled and additional dependent variables are added – a strategic complements indicator interacted with the levels of revisions opportunities and stage and with the level of revision opportunities and match. Table 4 reports the results of this exercise.Footnote 11 The results show that in the baseline treatment, average payoff efficiency is higher under substitutes as illustrated by the negative coefficient on the complements dummy in column (1) (p value 0.044). In the unilateral treatment, by contrast, payoff efficiency is higher under complements, as shown by the sum of coefficients on “complements” and “complements

![]() unilateral” (p value 0.073). These results also confirm the overall message, with respect to the comparison across game types that is visible in Fig. 2. Namely, there is a significant effect of the type of strategic interaction on the development of collusion across matches. The development of collusion within a match is comparable across game types.

unilateral” (p value 0.073). These results also confirm the overall message, with respect to the comparison across game types that is visible in Fig. 2. Namely, there is a significant effect of the type of strategic interaction on the development of collusion across matches. The development of collusion within a match is comparable across game types.

Result 2

With revision opportunities (unilateral) there is (weakly) more collusion in first-stage choices and (weakly) higher average payoff efficiency with strategic complements. Without revision opportunities (baseline) there is (weakly) more collusion in first-stage choices and (weakly) higher average payoff efficiency with strategic substitutes.

3.3 Individual behavior

The previous subsections dealt with the impact of revision opportunities and the type of strategic interaction by assessing outcomes along the realized path of play. To understand further what drives these realized paths, this subsection analyses individuals’ intended strategies. To this end, Table 5 gives the distribution of the machines programmed at the beginning of matches 7–10, along with a breakdown of the initial choices associated with each machine.

In principle there are 256 different machines—that is, the dynamic response part of the intended strategy—that participants could use. However, only seven types were used with a frequency of at least 5 percent in at least one of the treatments.Footnote 12 These prominent types of machine seem reasonable, with the majority corresponding to strategies that are commonly seen either in prior experimental studies or from the theory of repeated games. The first four—AAAA, ABC(C/D), ACCC and BBCC—attempt to establish some collusion, either unconditionally or conditionally.Footnote 13 Of the non-cooperative machines, there is the static Nash machine (CCCC), the myopic best response machine (DCCC under substitutes and BCCC under complements) and the punishing machine (DDDD).

Table 5 Distribution of initial choice and machine categories (in percent)

|

Prominent |

Strategy |

Substitutes |

Complements |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Machine category |

Initial-machine |

Base |

Bil |

Uni |

Base |

Bil |

Uni |

|

Unconditional cooperation |

AAAA |

1 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

1 |

8 |

|

A- |

1 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

1 |

8 |

|

|

Conditional cooperation |

ABC(C/D) |

18 |

16 |

11 |

10 |

18 |

23 |

|

A- |

12 |

8 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

19 |

|

|

B- |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

4 |

|

|

Nash reversion |

ACCC |

12 |

16 |

7 |

16 |

5 |

12 |

|

A- |

10 |

13 |

7 |

12 |

2 |

12 |

|

|

Partial collusion + Nash rev. |

BBCC |

1 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

7 |

1 |

|

B- |

0 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

|

|

Nash |

CCCC |

17 |

10 |

22 |

22 |

26 |

14 |

|

C- |

11 |

9 |

14 |

21 |

19 |

13 |

|

|

Myopic best reponse |

DCCC |

16 |

12 |

19 |

|||

|

C- |

7 |

4 |

7 |

||||

|

D- |

7 |

7 |

11 |

||||

|

BCCC |

25 |

21 |

15 |

||||

|

B- |

5 |

10 |

10 |

||||

|

C- |

17 |

10 |

4 |

||||

|

Punishing |

DDDD |

0 |

7 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

D- |

0 |

7 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Other |

——– |

35 |

36 |

31 |

20 |

22 |

27 |

|

All machines with a ... |

|||||||

|

Cooperative response to action A |

40 |

48 |

35 |

33 |

30 |

52 |

|

|

Cooperative response to action B |

28 |

28 |

29 |

22 |

33 |

39 |

|

|

Deviation response (D/B) to action A |

31 |

33 |

38 |

35 |

35 |

32 |

|

|

Punishing response to deviation (D/B) |

22 |

37 |

23 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

|

Distribution of prominent machines programmed at the beginning of matches 7–10 (in bold), along with a breakdown of the prominent initial choices associated with each machine (in italics). Machine combinations that were used with a frequency below 5 percent in every treatment are categorized as “Other”. A cooperative response to A is any machine that chooses A in response A; a cooperative response to B is any that chooses A or B in response to B; a punishing response to the deviation action is any that chooses D in response to D under substitutes and D in response to B under complements

The treatment comparisons in Table 5 mirror those seen in the data from the realized path of play. Under strategic substitutes there is no consistent effect of revision opportunities on intended strategies. In particular, there is no significant difference between the baseline treatment and the unilateral treatment in the likelihood of programming a collusive dynamic response—that is, either responding cooperatively to the other player having played A (40 vs. 35%; p value

![]() 0.520) or to the other player having played B (28 vs. 29%; p value

0.520) or to the other player having played B (28 vs. 29%; p value

![]() 0.785).Footnote 14 Indeed the only significant difference under substitutes is that subjects are more likely to respond cooperatively to action A with bilateral revision opportunities than unilateral ones. This more collusive response under bilateral is counter-balanced by a greater use of punishing responses, especially after the other player has played the deviation action (although in isolation this difference between bilateral and unilateral, 37 vs. 23%, is not significantly different, p value

0.785).Footnote 14 Indeed the only significant difference under substitutes is that subjects are more likely to respond cooperatively to action A with bilateral revision opportunities than unilateral ones. This more collusive response under bilateral is counter-balanced by a greater use of punishing responses, especially after the other player has played the deviation action (although in isolation this difference between bilateral and unilateral, 37 vs. 23%, is not significantly different, p value

![]() 0.125).

0.125).

By contrast, revision opportunities have a significant and positive effect on the cooperativeness of intended strategies under strategic complements. In the unilateral treatment, subjects are significantly more likely to respond in a collusive manner after the other player chose A than in both the baseline (52 vs. 33%; p value

![]() 0.019) and the bilateral (52 vs. 30%; p value

0.019) and the bilateral (52 vs. 30%; p value

![]() ) treatments. In addition, subjects are also more likely to respond with a collusive action after action B in the unilateral than in the baseline treatment (39 vs. 22%; p value

) treatments. In addition, subjects are also more likely to respond with a collusive action after action B in the unilateral than in the baseline treatment (39 vs. 22%; p value

![]() 0.012). As seen in Table 5, intended strategies are generally composed of the “intuitive” initial choice to go with the chosen machine. Furthermore, as seen in Figs. 2 and 3, stage-one choices and efficiency respond strongly to the change in revision opportunities under strategic complements.Footnote 15

0.012). As seen in Table 5, intended strategies are generally composed of the “intuitive” initial choice to go with the chosen machine. Furthermore, as seen in Figs. 2 and 3, stage-one choices and efficiency respond strongly to the change in revision opportunities under strategic complements.Footnote 15

Result 3

(1) With strategic substitutes, strategy revision opportunities have no clear effect on intended strategies. (2) With strategic complements, strategy revision opportunities lead to an increase in the use of more cooperative dynamic responses.

In summary, strategic complementarity appears to induce more collusive outcomes when players have the opportunity to revise their initial intended strategies for two reasons. The first, and most direct effect, is that intended strategies are more collusive, both in terms of more efficient initial choices and more cooperative dynamic responses. However, there is a second reinforcing effect in how participants respond to myopic best response actions (action B under strategic complements and action D under strategic substitutes), which is revealed by the numbers in the bottom part of Table 5. The myopic best response action triggers a punishing response in 22–37% of the cases under strategic substitutes and in only 2–4% of the cases under strategic complements. Under complements, a participant playing the myopic best response is still quite likely to iterate to at least a partially cooperative outcome; under substitutes, such a strategy most likely instigates a spiral towards a Nash or punishment outcome.

4 Discussion

Our primary result is that, while strategy revision opportunities have no effect on collusion under strategic substitutes, they have a significant positive effect under strategic complements. What could explain the role of revision opportunities, given that the standard prediction from game theory suggests it should play no role? In what follows, we discuss two popular concepts from the theoretical and experimental literature on repeated games (see, for example, Farrell and Maskin Reference Farrell and Maskin1989; Fonseca and Normann Reference Fonseca and Normann2012; Blonski et al. Reference Blonski, Ockenfels and Spagnolo2011; Dal Bó and Fréchette Reference Dal Bó and Fréchette2011). Neither will be able to provide a satisfactory explanation for our results. We define a notion of fear of miscoordination that yields predictions in line with the observed effect of changing the availability of revision opportunities.

4.1 Renegotiation

The observed ranking of collusion rates across treatments goes against the intuition delivered by the renegotiation literature. In particular, with fewer revision opportunities, and hence reduced concerns for renegotiation, we observe less collusion under strategic complements.

Although renegotiation should never happen in equilibrium—whether collusion is weak renegotiation proof or not—it is reasonable to expect the strategic forces that drive the concept would need to be learnt by experience. Consequently, there is still the possibility that subjects engaged in something like renegotiation, but that such efforts did not feed back into reduced collusion at the beginning of a match. We can look at our data from the bilateral treatment to see whether many attempts to “renegotiate” were made. Bilateral modifications take place very rarely. In particular, during matches 7–10 there were only 6 bilateral deviations (out of over 1200 interactions) with strategic substitutes and 9 with strategic complements from respectively 5 and 7 machines. Consequently, there are few instances where participants succeeded in coordinating on a mutual modification of their machines.

Nonetheless, the data collected on strategic decisions throughout the experiment allows some analysis regarding which paths are “renegotiated”, and if so, how. To do so, we study when and how machines are (attempted to be) modified conditional on the last outcome of the realized path of play. We classify paths into three categories: (1) “failed collusion” (outcomes (B,A) and (A,B)), (2) “miscoordination” (from the perspective of a cooperative agent; outcomes (A,C), (A,D), (B,C) and (B,D)) and (3) “punishment paths” (outcomes (C,D), (D,C) and (D,D)). After a “miscoordination” stage, participants mostly try to modify cooperative machines into more punishing machines. Along “punishment paths”, participants mostly (want to) modify non-cooperative machines, but rarely modify them into more collusive machines. Renegotiation theory, though, would say that participants modify punishing machines into more cooperative machines that allow them to leave a punishment stage.Footnote 16 Hence, in addition to the treatment comparisons, there is also no direct evidence that participants engaged in something like renegotiation.

4.2 Risk-dominance

Given the large number of possible equilibria in these indefinitely repeated games, it seems intuitive that considerations of renegotiation might be overshadowed by concerns of coordination on one of the different equilibria. Hence, it seems reasonable to look at risk-dominance, since it gives a role for a fear of equilibrium miscoordination. As discussed in Dal Bó and Fréchette (Reference Dal Bó and Fréchette2011), extending the idea of risk-dominance to infinitely repeated games poses a number of difficulties, even with only two actions for each player. These difficulties include extending the definition to repeated-game strategies and the issue that two repeated-game strategies can generate equivalent outcome paths. To these difficulties, our environment also adds the issue of extending the definition of risk dominance to more action choices in the stage game.

Blonski et al. (Reference Blonski, Ockenfels and Spagnolo2011) consider an extension of the concept to the repeated prisoners’ dilemma that involves only the strategies permanent Nash reversion and static Nash. Translating this approach to our environment results in the prediction that Nash reversion, with an initial choice of cooperation, is the risk-dominant strategy for both types of strategic interaction and all levels of strategy revision opportunities.Footnote 17 In what follows, we discuss how a definition of fear of miscoordination, which does not restrict itself to equilibrium miscoordination, can accommodate the observed behavior.

4.3 Fear of miscoordination

Since neither renegotiation nor risk dominance considerations are in line with our results, we consider a refinement based on a notion of “fear of miscoordination”. Given the large number of possible equilibria in indefinitely repeated games, fear of miscoordination seems a particularly relevant concern and its effect may overshadow any potential effect of renegotiation. Intuitively, players will be less concerned about mis-coordinating if they have the possibility to revise their strategy during the course of play. Hence fear of miscoordination delivers exactly the opposite intuition compared to renegotiation in terms of how revision opportunities should affect collusion.

We formalize this idea as follows. For a player i using repeated game strategy

![]() , the maximal regret possible for this strategy is given by

, the maximal regret possible for this strategy is given by

![]() is constructed as the difference between the payoff i expects when choosing

is constructed as the difference between the payoff i expects when choosing

![]() , while expecting her opponent to do the same, and the worst possible payoff that she could obtain by choosing this strategy. Notice that this definition is formulated from the perspective of a symmetric equilibrium in the context of two-player games, which is sufficient for the purpose of this study, but not crucial for the result we will state below.Footnote 18

, while expecting her opponent to do the same, and the worst possible payoff that she could obtain by choosing this strategy. Notice that this definition is formulated from the perspective of a symmetric equilibrium in the context of two-player games, which is sufficient for the purpose of this study, but not crucial for the result we will state below.Footnote 18

![]() Footnote 19 Equation (1) describes the fear of miscoordination in cases where strategy revision is not possible.

Footnote 19 Equation (1) describes the fear of miscoordination in cases where strategy revision is not possible.

To define fear of miscoordination if strategy revision is possible, define a sequence of pure strategies

![]() with the interpretation that at t the action prescribed by

with the interpretation that at t the action prescribed by

![]() given the history induced by

given the history induced by

![]() is chosen. Note that any fixed sequence of strategies can simply be expressed as a (potentially very complex) strategy itself and that constant sequences are possible as well. Denote by

is chosen. Note that any fixed sequence of strategies can simply be expressed as a (potentially very complex) strategy itself and that constant sequences are possible as well. Denote by

![]() a pair of such sequences

a pair of such sequences

![]() and by

and by

![]() player i’s discounted average payoff under

player i’s discounted average payoff under

![]() . Fear of miscoordination F can then be defined as,

. Fear of miscoordination F can then be defined as,

Of course the question arises, why would a player ever want to revise their strategy? After all, any situation under which a player would want to make a revision can be encoded in initial strategies as we have discussed in the introduction (Kuhn Reference Kuhn, Kuhn and Tucker1953). However, such strategies may be relatively complex, for example being automata involving many states. If there is any arbitrarily small but fixed cost of using automata with more states, agents would not want to use these additional states to encoding revisions for zero probability events (that is, histories that they do not expect to be reached).

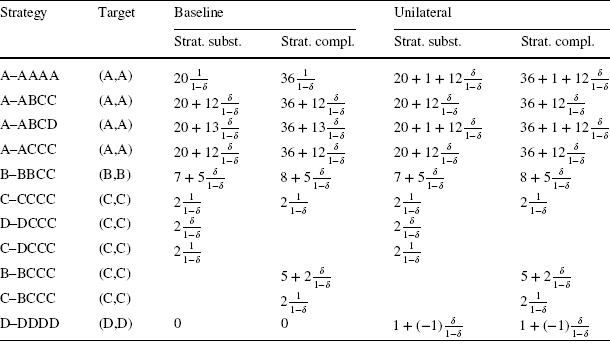

Table 6 Fear of miscoordination F for the most used machines

|

Strategy |

Target |

Baseline |

Unilateral |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Strat. subst. |

Strat. compl. |

Strat. subst. |

Strat. compl. |

||

|

A–AAAA |

(A,A) |

|

|

|

|

|

A–ABCC |

(A,A) |

|

|

|

|

|

A–ABCD |

(A,A) |

|

|

|

|

|

A–ACCC |

(A,A) |

|

|

|

|

|

B–BBCC |

(B,B) |

|

|

|

|

|

C–CCCC |

(C,C) |

|

|

|

|

|

D–DCCC |

(C,C) |

|

|

||

|

C–DCCC |

(C,C) |

|

|

||

|

B–BCCC |

(C,C) |

|

|

||

|

C–BCCC |

(C,C) |

|

|

||

|

D–DDDD |

(D,D) |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Maximal regret is obtained if the opponent plays D–DDDD. The second column labeled “target” is the outcome on which the strategy aims to coordinate on. The maximal regret is computed relative to this target

Table 6 shows the level of fear of miscoordination for prominent strategies in our main treatments, where “prominent strategies” are those that are used in at least

![]() of the cases in at least one treatment.Footnote 20 As can be seen, fear of miscoordination is higher if there are no revision opportunities. The biggest difference in fear of miscoordination is identified when we compare the baseline and the unilateral variation for strategies with (A,A) target (

of the cases in at least one treatment.Footnote 20 As can be seen, fear of miscoordination is higher if there are no revision opportunities. The biggest difference in fear of miscoordination is identified when we compare the baseline and the unilateral variation for strategies with (A,A) target (

![]() , see Table 6). Here we also see in our results that participants do use more cooperative machines in the unilateral variation compared to the baseline variation (52 vs. 33%; p value

, see Table 6). Here we also see in our results that participants do use more cooperative machines in the unilateral variation compared to the baseline variation (52 vs. 33%; p value

![]() 0.019, see Table E.11) at least for strategic complements.

0.019, see Table E.11) at least for strategic complements.

Fear of miscoordination is also higher for collusive strategies with complements than with substitutes. In particular, for strategies that target (A,A), the difference in fear of miscoordination between strategic complements and substitutes is

![]() in the baseline condition and 16 under the unilateral variation. Thus, fear of miscoordination can also explain why revision opportunities (that decrease fear of miscoordination) have a bigger effect on the incidence of cooperative strategies under strategic complements compared to strategic substitutes.

in the baseline condition and 16 under the unilateral variation. Thus, fear of miscoordination can also explain why revision opportunities (that decrease fear of miscoordination) have a bigger effect on the incidence of cooperative strategies under strategic complements compared to strategic substitutes.

4.4 Comparison to Potters and Suetens (Reference Potters and Suetens2009)

Despite some design differences our result of greater collusion under strategic complements than strategic substitutes in the presence of strategy revision opportunities replicates Potters and Suetens (Reference Potters and Suetens2009)’s seminal finding.Footnote 21 Potters and Suetens (Reference Potters and Suetens2009) explain their finding by suggesting that in response to a collusive move “best responding players will move in the same direction if choices are complements and in the opposite direction if choices are substitutes.” In other words, conditional on using for example myopic best responses, we should see more collusion under complements.

Our design allows us to also identify effects on intended strategies which tend to be more collusive under complements with revision opportunities (Sect. 3.3). The effect of revision opportunities on intended strategies can also explain why we find the opposite ranking than Potters and Suetens (Reference Potters and Suetens2009) in the absence of strategy revision opportunities. Fewer cooperative strategies are used under strategic complements compared to strategic substitutes if revision opportunities are missing. This can, for example, be explained with fear of miscoordination as described in the previous subsection.

Finally, one can ask which environment (presence or absence of revision opportunities) seems more relevant in applications. The answer to this question can depend, among others, on the attention the decision-maker gives to the interaction, whether there are organisational constraints that allow or impede quick revisions or whether human actors or computers (for example, price bots) execute a strategy. The importance of these factors in applications will determine whether they are best thought of as settings with or without strategy revision opportunities.

5 Conclusion

We have studied the effect of strategy revision opportunities on collusion in infinitely repeated games and found that, while revision opportunities do not affect collusion with strategic substitutes, they have a positive effect with strategic complements. The latter effect is strong enough that, although there is more collusion with substitutes if there are few or no revision opportunities, there is more collusion with complements if there are revision opportunities.

Our findings challenge received wisdom in the repeated game literature. This literature has largely ignored strategy revision opportunities due to the theoretical equivalence between behaviour strategies, which allow full flexibility during the course of play, and mixtures over strategies chosen at the start of the game are seen as equivalent in games of perfect recall. Our results show that revision opportunities matter, despite the fact that participants have a “large” strategy space available and could encode most standard behaviour strategies at the beginning of the game.

Our results could be of importance in a number of possible applications. Revision opportunities are often set by higher-level management and play an important role in the design of organizations. Managers at higher levels of an organization have to make day-to-day decisions on strategic oversight—that is, how much flexibility to give to lower-level management to make choices, or revise initially set strategies, as market conditions unfold (Daily et al. Reference Daily, Dalton and Cannella2003). The extent to which corporations regulate franchises “top down” or allow revisions to, for example, pricing strategies is only one example of such decisions. Policy makers should also be concerned about revision opportunities. Legal restrictions on meetings and agreements between market participants do affect the possibility of (orchestrated) strategy revisions and potentially affect prices and competition in local markets (see, for example, McCutcheon Reference McCutcheon1997). In some markets, including those for gasoline and ready-mixed concrete, competitors are sometimes forced by authorities to announce their prices upfront, leaving little room for spontaneous price revisions. In some other markets computers (for example, price bots) are typically executing strategies and to which extent they are regulated differs across settings. Our findings suggest that in markets where competition exhibits strategic complementarity, any policy which complicates strategy revisions might have an additional preventative effect on collusion. By contrast, such policies seem less likely to have an effect in a market of strategic substitutes. Future research could explore strategy revision in more applied designs to allow us to gain more insight into the importance of these questions in these applications.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jose Apesteguia, Antonio Cabrales, Pedro Dal Bó, Guillaume Fréchette, Lata Gangadharan, Konrad Mierendorff, Hans Theo Normann, Carlos Oyarzun, Sevgi Yüksel, two anonymous Reviewers as well as seminar participants in Brisbane, Düsseldorf, Maastricht (BEElab meeting), New York (ESA 2012), Vienna (Exp. Econ. workshop), Boston (IIOC 2013) and Lisbon (EARIE 2016) for valuable comments and the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and the European Union (FP7-ERG-277026) for financial support.