Introduction

One of the most significant current phenomena in politics – the third wave of autocratization (for example, Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Wiebrecht et al. Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023) – demonstrates that political competition can be structured primarily around the question of regime type, that is, whether a country ought to be democratic or autocratic (for example, Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013; Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020). In many countries, this regime change has been identified as a process led by executives variably termed ‘executive aggrandizement’ (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016), ‘incumbent takeover’ (Baturo and Tolstrup Reference Baturo and Tolstrup2023), and going hand in hand with higher levels of ‘personalism’ (Frantz et al. Reference Frantz, Kendall-Taylor, Nietsche and Wright2021). However, a second strand of literature has also emphasised the importance of analyzing opposition parties as key actors for resistance to autocratization (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022; Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023; Wiebrecht et al. Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023; Cleary and Öztürk Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022).

These two branches of research highlight the need to approach this as a dimension of the party system. Yet, we lack a framework to analyze the potential differences of regime preferences within and across party systems. The literature shows that party systems structure competition between parties primarily on policy positions (Sartori Reference Sartori1976), such as economic (Mair Reference Mair1997; Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Anna Vachudova2022; Dalton Reference Dalton2008), religious, as well as cultural (Abou-Chadi and Wagner Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020; Dassonneville, Hooghe and Marks Reference Dassonneville, Hooghe and Marks2024; Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020), and ethnic dimensions (Posner Reference Posner2004; Vogt et al. Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015), impacting voting behaviour (Dalton Reference Dalton2008) and influencing the formation of coalitions defining the balance of power between government and opposition (Sartori Reference Sartori1976; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988).

However, recent research shows that in many autocratizing countries, differences around economic ideologies and/or cultural divides have become overshadowed by conflicts around regime preferences as such (McCoy, Rahman, and Somer Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; McCoy and Somer Reference McCoy and Somer2019; Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020). It is therefore essential to capture the extent to which diverging regime preferences are present in party systems and how prevalent they are. This is not the least the case since this party-system dimension is possibly also crucial to explaining the advance or resistance of regime changes in either direction (Mainwaring and Scully Reference Mainwaring and Scully1995; Ong Reference Ong2022; Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024; Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022). To what extent is a party system (anti-)democratic?

To answer this question, we introduce and provide a conceptualization of party systems’ democratic positions, that is, the prevalence of preferences for democracy or autocracy in a party system. We place party systems on a continuum in which regime preferences are homogeneous at both ends (near-perfect commitment to democracy and absolute refusal of democratic preferences) while they are heterogeneous at intermediate levels. In addition, we provide a new empirical measure to estimate party systems’ democratic positions, the Party-System Democracy Index (PSDI), and validate it extensively empirically. Finally, we also show that party systems’ democratic positions are a significant predictor of regime changes in either direction. Results show the non-linear relationship between PSDI and onsets of democratization as well as autocratization, where countries experiencing intermediate levels of PSDI are more likely to be exposed to regime changes. We also present evidence for negative changes in PSDI triggering autocratization onsets and that positive changes in PSDI are associated with democratization onsets, though more weakly.

This article makes three contributions. First, complementing other structural factors of party systems such as the number of parties, their institutionalization, closure, nationalization, and fragmentation (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Blondel Reference Blondel1968; Duverger Reference Duverger1959; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2016; Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2018; Caramani Reference Caramani2004), we introduce a neglected dimension of party systems, namely their democratic positions. This dimension allows us to capture the prevalence of regime preferences for democracy and autocracy within and across party systems. As such, our work is the first to our knowledge to estimate the position of a party system on a democracy-autocracy continuum and responds to recent calls to study ‘regime cleavages’ in more detail (McCoy, Rahman, and Somer Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; McCoy and Somer Reference McCoy and Somer2019; Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020).

Second, we introduce an empirical measure that can capture this dimension cross-nationally. The PSDI has extensive global coverage at the party-system level (178 countries from 1970-2019) which is broader than any other party-system variable and allows scholars to link this new dimension of party systems with national-level outcomes. We corroborate its validity following Adcock and Collier’s (Reference Adcock and Collier2001) framework and highlight content validity by showing that the PSDI corresponds well to regime types and different measures of democracy. Additionally, we demonstrate convergent validity by testing its relationship with related measures such as normative regime preferences and power-sharing among social groups. Finally, we perform construct validation by linking the PSDI to party systems’ left-right economic dimensions, party system institutionalization indices, and constitutional types. Additionally, we also replicate Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán’s (2013, Chapter 4) findings on episodes of democratization in Latin America, and replace their variable on ‘normative preferences for democracy’ with the PSDI.

Third, extending the long tradition of research on democratization and autocratization (for example, Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2006; Diamond Reference Diamond1999), we test the relationship between levels and changes in PSDI and episodes of democratization and autocratization. Our results highlight the importance of analyzing all actors, that is, government and opposition, simultaneously in studying regime changes since they may all advance or resist such developments. Here, we combine findings from recent work on regime changes highlighting either the role of the executive (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016) or the opposition (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022; Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023) into a common framework.

The PSDI provides a new tool to understand party competition across the globe and its consequences for political institutions and broader society. We highlight four implications and possible applications beyond the focus on regime change in this article. First, it may help future research understand when and why mobilization for democracy and autocracy takes place. Second, the PSDI provides insights into government coalitions’ and opposition groups’ commitment to democracy. Third, current debates around voters’ susceptibility to vote for anti-democratic parties (for example, Svolik Reference Svolik2019) may also benefit from taking a broader perspective and incorporating party-system factors such as the PSDI into their analysis. Finally, party-system characteristics such as the PSDI should also provide additional explanatory power in understanding divergent policy outcomes across countries and regimes.

Conceptualizing Democratic Levels in Party Systems

The world is facing a large wave of autocratization meaning that not only are global levels of democracy declining but also that several countries have become autocracies in recent decades (Wiebrecht et al. Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023). Attributed to leaders such as Erdoğan and Orbán, autocratization has largely been described as an executive-led process (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Sato and Wiebrecht Reference Sato and Wiebrecht2024). While this is an accurate representation, recent research also points to the important role of the opposition parties in instances of autocratization (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022; Cleary and Öztürk Reference Cleary and Öztürk2022; Wiebrecht et al. Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023; Laebens and Lührmann Reference Laebens and Lührmann2021; Tomini, Gibril, and Bochev Reference Tomini, Gibril and Bochev2023). Their preferences and actions are also decisive for outcomes in autocratization processes as they may resist it with varying success.

The existing literature on democratization similarly focuses on individual parties and their elite-led episodes of democratization (Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013; Kavasoglu Reference Kavasoglu2022). This line of work shows that incumbent elites often purposefully change their regime preferences to stay in power and therefore come to initiate democratization episodes. Others also highlighted opposition parties’ fundamental role as a driving force whose democratic regime preferences can lead to democratization (Ong Reference Ong2022; Gandhi and Ong Reference Gandhi and Ong2019; Wahman Reference Wahman2013). In sum, most research on regime change looks at government and opposition actors in isolation, while both exist in a broader institutional setting simultaneously. Therefore, a comprehensive approach is needed in studying regime change that can account for government and opposition positions simultaneously.

We propose that analysing party systems can provide such a comprehensive approach and combine research on executive and opposition actions. Party systems structure the competition between individual parties allowing them to develop competing policy positions (for example, economic, religious, and ethnic) and influencing the formation of coalitions (Sartori Reference Sartori1976; Lipset and Rokkan Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967; Panebianco Reference Panebianco1988). Party systems have key implications beyond mere party politics. Previous literature has, for instance, identified party-system characteristics as important in determining voting behaviour including for anti-political establishment parties (Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Casal Bértoa and Rama Reference Casal Bértoa and Rama2020) polarization in society (Lupu Reference Lupu2015; Bischof and Wagner Reference Bischof and Wagner2019), and decentralization (Riedl and Tyler Dickovick, Reference Riedl and Tyler Dickovick2014). As such, they are also likely to be important factors regarding regime changes.

Previous work in this area has predominantly focused on the structural characteristics of party systems. Among others, these include the number of parties and party systems’ closure, volatility, institutionalization, and nationalization (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999; Blondel Reference Blondel1968; Duverger Reference Duverger1959; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2016; Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring2018; Caramani Reference Caramani2004). Yet, the consequences of these structural characteristics on political regimes remain debated (Valentim and Dinas Reference Valentim and Dinas2024; Casal Bértoa Reference Casal Bértoa2017).

Building upon these structural dimensions, we suggest that party systems are also a reflection of individual parties’ political and ideological positions. In other words, party systems are also defined by how prevalent certain ideas are across all parties. While governments are naturally in a privileged position to enact their preferences, due to veto players on different levels, they may not always directly translate into policies and outcomes. Previous research shows that the positions of the opposition and the party system as a whole also matter for welfare (Jensen and Bech Seeberg, Reference Jensen and Bech Seeberg2015) and immigration policies (Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2016). Yet, in contrast to party positions that have been measured using various methods and data (for example, Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Anna Vachudova2022; Pemstein et al. Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Medzihorsky, Krusell, Miri and von Römer2022; Gemenis Reference Gemenis2013; Carroll and Kubo Reference Carroll and Kubo2019), estimating overall party-system positions of this kind received much less attention.

We suggest that one of the most important dimensions of party systems for analysing regime changes is the prevalence of democratic (and authoritarian) preferences. Already Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) stressed the importance of ‘normative preferences for democracy’ of national political elites as a source of democratic regime stability in Latin America. Recent studies suggest that ‘democracy cleavages’ – differences over conceptions of democracy beyond conventional socioeconomic cleavages – are potential drivers of autocratization (Somer and McCoy Reference Somer and McCoy2018), for instance, in the cases of Turkey (Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020) and Venezuela (García-Guadilla and Mallen Reference García-Guadilla and Mallen2019). This points to the pressing task of accurately measuring the extent to which party systems are democratic or authoritarian on a global scale.

Although related (as shown below), the prevalence of democratic and authoritarian preferences is also different from countries’ democratic levels. Naturally, in a near-perfect liberal democracy, most parties and actors are expected to have a strong preference for democracy. The reverse is also expected at the other end of the continuum. Nevertheless, most countries in the world are not found at those extremes. In addition to famous examples such as Weimar Germany failing under the rise of the Nazi party (De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2024), one can now find anti-pluralist parties in most democracies and they often influence their competitors’ policies and agendas (Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024; Abou-Chadi and Krause Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). Similarly, in authoritarian regimes, ruling parties may decide to hold onto power in their restrictive systems or liberalize them subsequently (Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2022; Treisman Reference Treisman2020), while opposition parties may also either advocate democratic transitions or favour the status quo regime type, for instance, because they were co-opted (Howard and Roessler Reference Howard and Roessler2006; Reuter and Robertson Reference Reuter and Robertson2015).

Figure 1 illustrates this conceptualisation visually. In any party system, competition may arise around regime preferences on the abovementioned democratic-authoritarian continuum. The nature and extent of this competition depend on individual political parties’ regime preferences and the political influence they yield in their respective party systems. The latter may be most easily identified by parties’ seat shares in parliament. Together, parties’ preferences and influence constitute the latent democratic level of the whole party system where democratic stances may be either respected, contested, or rejected. Measuring the configuration of democratic preferences taking into account the strength of each party is a novel way of capturing this dimension of the party system and conceptually distinct from democracy levels. We suggest that all party systems can be placed on a continuum ranging from all parties being highly committed to democracy to all parties being decidedly anti-pluralist, that is, authoritarian.

Figure 1. From political parties to party-system democratic levels.

We illustrate the reasoning with three cases along this continuum. First, in near-perfect liberal democracies, the overwhelming majority of parties will be committed to democracy. Regime preferences are therefore not expected to structure party competition. Instead, differences in policies, either captured by parties’ positions on the traditional economic left-right or GAL-TAN dimensions (Gabel and Huber Reference Gabel and Huber2000; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Bakker, Brigevich, De Vries, Edwards, Marks, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2010) or on newly-emerging topics such as migration and integration (Polk and Rosén Reference Polk and Rosén2024; Bakker, Jolly, and Polk Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2022) will structure political parties’ interactions. Examples here include Norway and Switzerland, where a number of parties represent different positions and ideologies but where preferences around regime types do not structure the party system.

At the other end of this continuum, closed authoritarian regimes and hegemonic party systems also feature homogeneous preferences, but for autocracy. Again, therefore, regime preferences are not expected to structure political parties’ interactions. At the extreme, we find closed autocracies like China and Cuba where opposition parties are de jure or de facto disbanded, the ruling party fully controls the legislative chamber and legally does not allow for alternative political preferences (Angiolillo Reference Angiolillo2023). Thus, either de jure or de facto, debates around regime types are extremely limited, if not entirely absent.

Finally, in the middle, preferences for and commitment to regime types are heterogeneous. The more differences concerning democratic commitments characterize the party system, the more the latent trait of the party system’s democratic level will be contested. Between the two extremes on the democratic-autocratic continuum, parties’ interactions within the party system will be also structured around frictions on regime preferences, above and beyond the dimensions that existing party-system indices measure. When this (new) dimension is contested, one can observe what scholars term ‘democracy cleavages’ (Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020; García-Guadilla and Mallen Reference García-Guadilla and Mallen2019). It is also these contexts where we would expect most regime changes to begin. In other words, for episodes of autocratization or democratization to be initiated, there have to be actors in the party system advocating for changes that take the regime in either direction.

One implication of the theoretical expectations above is that if a party system moves from one of the extremes towards the middle along this dimension, it should be an ‘early warning’ sign of increasing potential for a regime change. Democracies’ party systems moving toward intermediate levels indicates an emerging anti-pluralism in the system that could translate into either executives engaging in aggrandizement (Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024; Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016) or into anti-regime opposition parties shifting the structure of political competition to new areas of contestation (Svolik et al. Reference Svolik, Avramovska, Lutz and Milaèiæ2023; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2012). Recent contributions also highlight that a large part of the electorate, even in democracies, is ready to support undemocratic actions, especially in polarized political contexts (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020). Hence, changes in parties’ appeals to the electorate and their commitment to democratic values can have dire consequences on the overall party system. As a result, party systems’ regressions along the democratic-autocratic continuum can then signal creeping movements towards more contested regime preferences. This could progressively stir away political parties’ discussions on policy preferences and, instead, pave the way for autocratization by attacking accountability mechanisms (Laebens and Lührmann Reference Laebens and Lührmann2021; Sato et al. Reference Sato, Lundstedt, Morrison, Boese and Lindberg2022; Linz Reference Linz1978).

Similarly, if the party system in an autocracy moves toward intermediate levels, it could indicate an increasing probability of subsequent democratization. In closed dictatorships, it could foreshadow ruling elites’ increasing acceptance of (limited) pluralism while in less dictatorial settings it could signal the opening of fairer multi-party elections that in themselves can contribute to democratization (Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2006; Donno Reference Donno2013). An overall shift away from authoritarian stances in the party system may then signal a decision among governing parties to liberalize the regime entirely (Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013; Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020). At the same time, an improvement toward the middle can also be seen if a (liberal) opposition party or parties contribute to this change due to an increase in their (electoral) strength (Ong Reference Ong2022; Wahman Reference Wahman2013).

Measuring the Party-System Democracy Index

To capture the latent democratic position of party systems across time and space, we created the Party-System Democracy Index (PSDI). The PSDI measures how preferences for democracy or autocracy are distributed in party systems across the globe by taking stock of parties’ individual levels of anti-pluralism and aggregating them on the party-system level taking parties’ relative strength into account. This measure is computed drawing from the V-Party dataset, which is the largest resource on political parties available, covering 3,151 elections across 178 countries from 1970 to 2019 and measures 3,467 political parties (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasogly, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken and Laebens2022; Pemstein et al. Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Medzihorsky, Krusell, Miri and von Römer2022). V-Party generates estimates through the leading V-Dem expert-rating methodology (Pemstein et al. Reference Pemstein, Marquardt, Tzelgov, Wang, Medzihorsky, Krusell, Miri and von Römer2022; Coppedge et al., Reference Coppedge2023). Yet, the V-Party raters were recruited mostly from outside the regular V-Dem pool of experts for their expertise on political parties in specific countries.Footnote 1 The V-Party data collection also took place separately and at a different time from the regular V-Dem coding period, making it unlikely that experts remember how they rated for V-Dem when they coded for V-Party. The questions posed in the V-Party expert survey focusing on stances expressed by individual parties are also independent of and of a different nature than V-Dem surveys focusing on country averages. In addition, V-Party’s Item Response Theory (IRT) model is able to produce high and low bounds when aggregating expert coding that functions similarly to traditional confidence intervals. Finally, V-Party indicators and indices have been validated by previous studies (Düpont et al. Reference Düpont, Berker Kavasoglu, Lührmann and John Reuter2022; Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024). We thus feel confident in the quality and independence of the V-Party data. To estimate the PSDI, we use the following equation:

$${\rm{PSDI}} = 1 - \mathop \sum \limits_{p = 1}^N \left( {{\rm{AP}}{{\rm{I}}_{{\rm{pt}}}}{{\ *\ }}w{s_{{\rm{pt}}}}} \right)$$

$${\rm{PSDI}} = 1 - \mathop \sum \limits_{p = 1}^N \left( {{\rm{AP}}{{\rm{I}}_{{\rm{pt}}}}{{\ *\ }}w{s_{{\rm{pt}}}}} \right)$$

Where p represents political parties, t is the time of the election-year, and ws the weight for each party’s seat share within the lower house (v2paseatshare), while API is the anti-pluralist index (v2xpa_antiplural). In creating Equation 1, we follow two main steps leveraging on (i) the anti-pluralist index by Medzihorsky and Lindberg (Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024) and (ii) the party-system level as a whole.

In the first step, the PSDI builds on V-Party’s anti-pluralist index (API), which is an aggregated measurement of parties’ commitment to political pluralism,Footnote 2 respect of political opponents, defence of minority rights, and rejection of political violence. The API ranges from 0 (highly pluralistic) to 1 (highly anti-pluralistic) (Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024), and captures the extent to which a party is committed to the core elements of democratic standards (Linz Reference Linz1978). It is worth emphasizing that this conceptualization of pluralism goes to the heart of parties’ stance toward democracy as a political system and is distinct from policy stances. The API has also been validated extensively making it a suitable index to build upon (Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024).

In the second step, as parties’ influence on the political system changes according to their electoral performances, we weight the anti-pluralism levels by parties’ seat shares in parliament, which is a common approach to account for parties’ relative size and political power (Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020). Moreover, this approach also reduces some possible V-Party data structure limitations since ‘as the general rule experts coded data for all parties that reached more than 5 per cent of the vote share at a given election’ (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasogly, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken and Laebens2022, p.5). As shown in the Appendix, we find that weighting by vote share would mildly increase missingness, particularly in countries using single-member district electoral systems, where the composition of parliament is well-known but aggregated national voting results may not be known.

Lastly, we rescale the PSDI to range from 0 to 1 and the resulting measure is subtracted from 1. This allows us to structure the PSDI so that lower levels are associated with more authoritarian party systems and higher levels with more democratic ones. This direction is intuitively comparable across countries, time, and other prominent cross-national measurements (for example, V-Dem, Polity V, Freedom House).

To summarize, the PSDI is the empirical result of (i) the anti-pluralist position of each political party p in the party system, (ii) weighting political parties by their seat shares, and finally, (iii) computing the democratic stances of the overall party system.Footnote 3 As a result, we leverage the wealth of data from party-country-election-year to reach a continuous variable at the country-election-year, ranging from 0 to 1, with values closer to 0 corresponding to more authoritarian party systems, and values closer to 1 translating into party systems being more democratic.Footnote 4

Along with the PSDI, we provide two sub-component variables related to the government’s and opposition’s democratic levels,Footnote 5 which brings at least three additional benefits. First, we increase the transparency of the PSDI, allowing for the inspection of the sub-components independently of, and together with, the PSDI. Second, these two sub-components can help develop further research on the government’s and opposition’s regime attitudes separately, connecting them with citizens’ voting behaviours (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Laebens and Öztürk Reference Laebens and Öztürk2021) and inter-party coalition and coordination challenges (Arriola Reference Arriola2013; Wahman Reference Wahman2013), among others. Third, by providing PSDI’s sub-components, it is possible to better unpack the origins of regime changes and assess with higher precision the role of governmental parties’ democratic position (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019) compared to the entire party system’s.

Validation

We follow Adcock and Collier’s (Reference Adcock and Collier2001) framework in validating the PSDI performing content, convergent, and construct validation.

Content Validation

Figure 2 compares the PSDI to the three most prominent continuous measures of democracy: V-Dem’s Electoral Democracy Index (EDI) (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Angiolillo, Bernhard, Borella and Cornell2024), Polity Score by Polity5, and Freedom House’s Freedom in the World. According to the ‘adequacy of concept’ by Adcock and Collier (Reference Adcock and Collier2001, p. 538), we should expect that most parties in highly democratic countries (closer to 1, +10, or 100 in the datasets’ respective scales) do not have preferences for undermining the political system as such. Therefore, parties’ individual scores on the anti-pluralism index should in most cases be low and, consequently, the PSDI should be closer to 1 (more democratic party systems). Conversely, authoritarian party systems where formal opposition is not allowed should have a high density at the lowest democracy levels.

Figure 2. PSDI and different measures of democracy.

Figure 2 confirms this expectation showing that there are three quite distinct fitted lines across the three measures pointing to the linear relationship between levels of democracy and party-system democratic positions. The high density of observations around the top-right corners in the three panels in Figure 2 shows the commitment to pluralism from the vast majority of parties in high-level democracies. Conversely, the high density of observations at the bottom-left corners in the three panels is mainly driven by de jure or de facto lack of opposition parties in closed autocracies.

Figure 2 also shows more scattered observations when PSDI is lower than 0.8. This illustrates that both electoral democracies and electoral autocracies can have party systems that are relatively more democratic or authoritarian. This result highlights how parties’ commitment to democratic stances can have a higher variation in these regimes, which previous literature shows as more likely to be exposed to regime transformations (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Diamond Reference Diamond2015; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019). Between the two extremes of highly democratic or authoritarian party systems, we find scattered observations when focusing on electoral autocracies and democracies (or hybrid regimes). The primary reason has to do with the heterogeneity in democratic commitment among parties involved in the party system, which makes it a contested space. In electoral autocracies, the limited freedoms opposition parties have in competing in free and fair elections result in severely undermining alternative regime preferences (for example, democratic). In electoral democracies, the rise of anti-democratic parties could drive the PSDI away from the top-right corners and shift the party system to a more contested space.

Figure A1 in the Appendix shows Figure 2 through a density plot. Figures A2–A7 in the Appendix report each country’s PSDI levels between 1970-2019. We also provide an alternative measurement using the PSDI distribution by regime types according to the Regimes of the World measure (Lührmann, Lindberg, and Tannenberg Reference Lührmann, Lindberg and Tannenberg2017) (Figure A8 in the Appendix), which shows that the highest levels of PSDI are concentrated in liberal democracies, while it has more variation in electoral democracies and moves towards 0 in autocracies.

Four Typical Cases

In Figure 3, we present the change in the PSDI over time in four typical cases: (i) a liberal democracy (Germany), (ii) an episode of autocratization in India since 2008 (Edgell et al. Reference Edgell2023), (iii) an episode of democratization in Mexico between 1988 and 2001 (Edgell et al. Reference Edgell2023), and (iv) the Soviet Union as a closed autocracy (1917-1990) and the subsequent Russian Federation as an electoral autocracy since 1991.

Figure 3. The PSDI and regime stability, democratization, and autocratization episodes.

Note: The dotted lines refer to the PSDI’s confidence intervals, while the two solid lines represent the PSDI (blue) and EDI (red) The lower and upper bounds are calculated by substituting the API with its low/high intervals in Equation 1 (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Angiolillo, Bernhard, Borella and Cornell2024, 33).

For stable liberal democracies like Germany, the party system is characterized by high levels of commitment to democratic values across all parties. In addition, the German case also shows that once an anti-pluralist party enters parliament, the PSDI captures the change and decreases accordingly. The rise of the decisively anti-pluralist party Alternative for Germany (AfD) (Arzheimer and Berning Reference Arzheimer and Berning2019) changed the German PSDI from 0.97 in 2013 to 0.87 in 2017, a statistically significant decrease in Figure 3. Meanwhile, Germany’s EDI remains virtually unchanged (the small drop between 2013 and 2023 is not statistically significant) (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Angiolillo, Bernhard, Borella and Cornell2024).

The autocratization case of India illustrates that the PSDI can be an ‘early warning’ indicator of a higher probability of democratic backsliding. The gradual decline in the PSDI dimension of the party system started in the 1980s, predating the onset of autocratization as measured by the EDI by over a decade. In Figure 3, India’s PSDI declined from 0.82 in 1980 to 0.45 in 2014, while the EDI was relatively stable with a non-statistically significant change from 0.65 in 1980 to 0.62 in 2014. It captures the increasingly different regime preferences between the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and that Modi’s BJP not only became more anti-pluralist but also increased its size in parliament. The BJP’s anti-pluralist stances became an effective appeal to voters, especially in social contexts with high fractionalization of other cleavages, such as ethnic and religious (Chhibber and Verma Reference Chhibber and Verma2018; Harriss Reference Harriss2015). The Indian case presents some evidence of how the PSDI dimension became increasingly salient, changing the nature of inter-party interactions and leading to severe tensions around regime preferences.

In Mexico, the hegemonic electoral authoritarian government under the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that allowed opposition only formally (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006) led to a fairly low PSDI for a long time.Footnote 6 During the 1990s, the PSDI gradually increased when PRI’s internal reforms led to a reduction of anti-pluralism in the ruling party (Langston Reference Langston2017), a decline in its share of seats, and the emergence of other more pluralist parties in the party system (Levitsky et al. Reference Levitsky, Loxton, Van Dyck and Domínguez2016). Figure 3 shows how the PSDI captures this and reaches its peak following the 2000 elections that led to the first alternation in power and, according to many observers, the inauguration of democracy in Mexico. With the PRI in opposition with a smaller number of seats in parliament, the PSDI increased from 0.4 in 1988 to 0.76 in 2000 with a similar change in EDI passing from 0.34 in 1988 to 0.67 in 2000. This elite-led democratization (Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020), which allowed national elites to liberalize the country and the party system simultaneously, led to changes in both, PSDI and EDI, and therefore the PSDI does not precede changes in EDI.

Autocracies may be closed completely or their party systems may be dominated by ruling parties (Angiolillo Reference Angiolillo2024), like in Russia. Figure 3 shows the flat PSDI score at 0 for the Soviet Union’s single-party regime between 1970-1989. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the PSDI increased, following the democratization of the party system. However, this was followed by a first drop in the PSDI already under Yeltsin (1991-1999), and a second erosion of the party system under Putin and the establishment of his party, United Russia (Reuter Reference Reuter2017). Between 1993 and 2003, the PSDI moved from 0.53 to 0.19, while the EDI had a milder, yet statistically significant, decrease from 0.48 to 0.34. United Russia can be seen as a hegemonic ruling party, which resonates with the low PSDI levels as these regimes allow formal opposition parties, but their chances of victory are marginal and even they do not have a strong commitment to democracy, which reflects the lower PSDI score than Mexico during the PRI era.

Figure A9 in the Appendix reproduces the case studies in Figure 3 by disaggregating the PSDI into its two possible sub-components of government and opposition democracy positions, providing further evidence on the aggregate parties’ (anti)democratic drivers. In additional content validity tests, a paired plot (Figure A10 in the Appendix) demonstrates that the PSDI indeed captures party-system dynamics that differ from merely measuring the anti-pluralism index of the governing coalition, and compare with studies (typically focusing on Western Europe) using party system-level indicators measured with vote-share weights instead of seat-share (for example, Dalton Reference Dalton2008; Reiljan Reference Reiljan2020); we recompute Equation 1 using vote shares. Figure A11 in the Appendix shows that there is no major difference between the two measures. However, there is a marginal 3.8 per cent of the sample that takes extreme values depending on the selected weight (cases listed in Table A1), which strengthens the confidence in using the seat share and we articulate the reasons in the Appendix. Lastly, Figure A12 shows that there are no significant differences across majoritarian, proportional, and mixed electoral systems.

Convergent Validation

For tests of the convergent validity, we use two measurements, elites’ preferences for democracy and distribution of power by social groups, of varying similarity to the PSDI.

Panel A in Figure 4 shows the PSDI’s relationship to the ‘normative preferences for democracy’ across all elites in Latin American countries between 1970-2010 developed by Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013). Although Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán’s (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) measure focuses on elites and the PSDI on party systems, these two measures are expected to be highly correlated. Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) variable ranges from -1 (absence of democratic preferences) to +1 (high democratic preferences). Panel A corroborates our expectation, further strengthening the convergent validity of the PSDI. Moreover, PSDI’s coverage extends further than only Latin American countries and features a global sample.

Figure 4. Correlations of the party-system democracy index (PSDI) and related concepts.

In Panel B in Figure 4, we explore the PSDI’s convergent validity further by using Marquardt’s (Reference Marquardt2021) ‘Identity-based exclusion’ measure,Footnote 7 a latent variable aggregating the V–Dem and Ethnic Power Relations Projects’ inclusion variables by Vogt et al. (Reference Vogt, Bormann, Rüegger, Cederman, Hunziker and Girardin2015), which adjusts the distribution of power by social groups accounting for the political relevance of such groups. We expect convergence between these two measures since a somewhat equal power distribution across social groups is almost definitionally a characteristic of a democratic party system (Dahl Reference Dahl2008). Panel B corroborates this expectation further strengthening the convergent validity of the PSDI.

Construct Validation

We organize the construct validation in two complementary approaches. First, we test the PSDI against different concepts expected to be correlated. Second, we replicate the findings by Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) on the relationship between elites’ normative preferences for democracy and democratization.

Panel A in Figure 5 compares the PSDI with the party-system economic left-right dimension, which is computed using Equation 1 and replacing ‘API’ with ‘economic left-right’ from the V-Party dataset (Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasogly, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken and Laebens2022). This generates values for every party system on a scale from 0 (extremely left-wing) to 1 (extremely right-wing). We expect the PSDI index to have a second-polynomial correlation with left-right levels since democratic regime preferences can be undermined when party systems’ centrifugal directions are predominant (Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024; Schamis 2006; Weyland Reference Weyland2013; Sartori Reference Sartori1976). The results shown in Panel A conform with our expectations of party systems across the globe. Furthermore, we retest the same convergence by using CHES Europe data on left-right economic positions (Jolly et al. Reference Jolly, Bakker, Hooghe, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Anna Vachudova2022), which yielded similar results as shown in panel A in Figure A13 in the Appendix.

Figure 5. Construct validation of the party-system democracy index (PSDI).

Panel B in Figure 5 shows the correlation between the PSDI and party-system institutionalization index as computed by Kim (Reference Kim2023), which is limited to democracies around the world and captures the following concepts: aggregate legislative volatility, aggregate government volatility, minor party performance, party distinctiveness, and party switching. Kim’s (Reference Kim2023) index ranges from lack of party system institutionalization (-3) to highly institutionalized (1). Previous literature finds that more institutionalized party systems are associated with higher levels of democracy (Chiaramonte and Emanuele Reference Chiaramonte and Emanuele2022; Ridge Reference Ridge2023; Casal Bértoa and Enyedi Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2021), which leads to the expectation that more democratic party systems also tend to be more institutionalized. Panel B corroborates this expectation with the PSDI. We also test for an alternative measurement presented by Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2022) on ‘party system closure’ in Europe, which yields similar results as reported in panel B in Figure A13 in the Appendix.

Panel C in Figure 5 shows the correlation between the PSDI and constitutional types differentiating between presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary, drawn from Scartascini, Cruz, and Keefer (Reference Scartascini, Cruz and Keefer2021). The literature points to higher levels of democracy in parliamentary systems compared to presidential ones (Linz Reference Linz1990; Stepan and Skach Reference Stepan and Skach1993; Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021), which are corroborated by results in panel C where parliamentary systems have significantly higher levels of PSDI than other constitutional typologies. We also use Cheibub’s (Reference Cheibub2007) data to replicate this convergence in panel C in Figure A13, which leads to similar results.

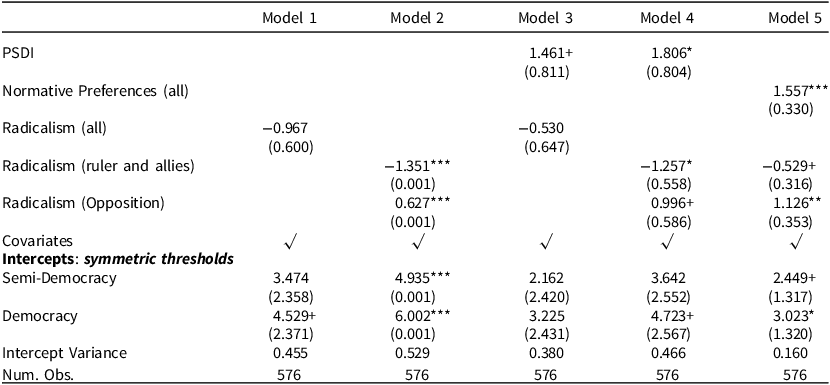

The last construct validation entails the replication of previous findings replacing the variable most closely related to the PSDI with it. Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán’s (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) ‘normative preference for democracy’ refers to the commitment to democratic norms of ruling and opposition elites. Although their approach is limited to individuals rather than parties or party systems, their concept relates to the overall democratic commitment of actors placed in a favourable position to effectively influence the governance of a country. For these reasons, ‘normative preference for democracy’ and the PSDI relate to similar enough concepts to perform a construct validity. Hence, we replicate the quantitative analysis on regime change in Latin American countries presented by Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013, 104–105). They test how actors’ normative preferences for democracy are, on average, the driver for regime transition from an autocracy to a semi-democracy or a democracy. Table 1 shows similar results to the original multilevel logit models presented by Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013), where we replace their ‘normative preferences for democracy’ variable with the PSDI. This strengthens the construct validity of the PSDI.

Table 1. Replication of Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013, Tab 4.2) using PSDI

Note: Random-effects ordered logistic coefficients (standard errors) with symmetric thresholds. P-value: p<0.1+, p<0.05*, p<0.01**, p<0.001***.

Empirical Application: PSDI and Regime Change

Inspired by the results of replicating the study on regime survival in Latin America, we move to test if the PSDI is also a good predictor for a wider scope of regime changes on a global scale. We draw from Maerz et al.’s (Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2023) definition of regime transformations as a ‘substantial and sustained’ (p.5) change in democratic levels to identify positive (democratization) or negative (autocratization) episodes of regime transformation. We focus on the onset of regime transformation, which is defined as the year in which the autocratization or democratization begins.

The literature suggests that regimes classified as hybrid, electoral (democracies and autocracies), and semi-democratic are more likely to be exposed to regime transformations (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Diamond Reference Diamond2015; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2006), while highly democratic or authoritarian regimes are on average more stable (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz Reference Geddes, Wright and Frantz2014; Lachapelle et al. Reference Lachapelle, Levitsky, Way and Casey2020; Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021). It seems reasonable to intuit that varying levels of democratic commitments that structure party systems could play a role in this. At the extremes, parties are unified in their commitment to democratic or Cheibub’sauthoritarian stances, while heterogeneity structuring political competition in the ‘muddled middle’ can contribute to regime transformations (McCoy, Rahman, and Somer Reference McCoy, Rahman and Somer2018; Evans and Whitefield Reference Evans and Whitefield1995; Selçuk and Hekimci Reference Selçuk and Hekimci2020). For these reasons, we expect:

H1a: A negative quadratic relationship between PSDI levels and onsets of autocratization

H1b: A negative quadratic relationship between PSDI levels and onsets of democratization

Previous literature shows the important role of anti-pluralist political parties coming into power to start autocratization episodes (Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024; Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020), which tallies with others highlighting the predominant role of the executive driving it (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019) and the opposition resisting it – sometimes successfully (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022; Wiebrecht et al. Reference Wiebrecht, Sato, Nord, Lundstedt, Angiolillo and Lindberg2023). In addition, democratic commitment may also wane among the supporters and elites of established parties (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Krishnarajan Reference Krishnarajan2023; Wuttke, Gavras, and Schoen Reference Wuttke, Gavras and Schoen2022). Building on these streams of literature, we intuit that changes in party systems on the PSDI dimension are also predictors of regime changes by altering the probability of an onset. Accordingly, we should also expect that a negative change in the PSDI is a predictor of autocratization episode onsets. The second hypothesis is:

H2: A negative change in PSDI is associated with an increase in the probability of autocratization onsets.

Conversely, the literature on political parties and democratization focusing on authoritarian parties’ elite-led episodes of democratization shows that they often purposefully change their regime preferences to secure survival in power (Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2013; Albertus and Menaldo Reference Albertus and Menaldo2018; Kavasoglu Reference Kavasoglu2022). Others have studied the role of opposition parties’ democratic regime preferences play as driving forces of democratization (Ong Reference Ong2022; Gandhi and Ong Reference Gandhi and Ong2019; Wahman Reference Wahman2013). Taken together, we infer from this literature that changes in the overall party system level of commitment to a more democratic regime should be of importance to the probability of whether democratization takes place or not. We thus expect that:

H3: A positive change in PSDI is associated with an increase in the probability of democratization onsets.

Model Specifications

To test these hypotheses, we employ probit models with year-level random effects and standard errors clustered at the country-level. Different from the analyses above replicating Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán’s (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) study, we now use two dichotomous variables from the Episodes of Regime Transformations (ERT) by Maerz et al. (Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2023) as dependent variables. The first captures the onset of autocratization (1) or not (0), while the second identifies whether an onset of democratization takes place (1) or not (0).Footnote 8

The key independent variables in Hypotheses 1a and 1b are the PSDI level and the quadratic PSDI level, which ensures capturing non-linear relationships of interest. In the evaluation of Hypotheses 2 and 3, we use the change of PSDI but also compute it over different time periods to gain further insights into the dynamics of regime transformations. Previous literature suggests that autocratization can start shortly after an autocratic incumbent is elected into office (Laebens and Lührmann Reference Laebens and Lührmann2021) and that the extent of autocratization can even deepen in the mid-run (Lührmann and Lindberg Reference Lührmann and Lindberg2019; Knutsen, Mokleiv Nygård and Wig, Reference Knutsen, Mokleiv Nygård and Wig2017). Opposed to this, democratization often is a slower process that requires authoritarian elites’ commitment to democratization and/or opposition parties’ gaining traction from the popular vote (Ong Reference Ong2022; Wahman Reference Wahman2013; Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2006).

We also employ a set of control variables on economic, political, and social aspects. First, we follow Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013) and Carter and Signorino (Reference Carter and Signorino2010) and add a cubic transformation of the regime’s age as reported by Maerz et al. (Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2023) ERT framework, controlling for possible duration-dependence. Second, we use a set of economic variables from the Maddison Project Database (MPD) in the form of one-year per cent GDP growth, GDP per capita (logged), and one-year per cent GDP per capita change, which can influence regime stability. Third, due to a suggested neighbourhood effect (Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021), we also control for the average democratic level of the political regions with a one-year lag, as well as whether the incumbent accepted electoral outcomes, levels of legislative constraints, and the extent of civil society participation, all three lagged at one-year as well, as previous literature shows these variables’ importance in possible regime transformations (Boese et al. Reference Boese, Edgell, Hellmeier, Maerz and Lindberg2021; Kim, Bernhard, and Hicken Reference Kim, Bernhard and Hicken2023; Hellmeier and Bernhard Reference Hellmeier and Bernhard2023)Footnote 9 These variables are taken from the V-Dem dataset by Coppedge et al. (Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Henrik Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Angiolillo, Bernhard, Borella and Cornell2024), which is different from the V-Party dataset by Lindberg et al. (Reference Lindberg, Düpont, Higashijima, Kavasogly, Marquardt, Bernhard, Döring, Hicken and Laebens2022) from which we create the PSDI using Equation 1. Lastly, we also control for identity-based exclusion from Marquardt (Reference Marquardt2021), which can further explain some societal tensions.

Main Results

Figure 6 reports the predicted probability for the relationship between PSDI and autocratization (panel A) and democratization (panel B) onsets, while Table A3 reports the full results testing H1a (Models 1–3) and H1b (Models 4–6). While the PSDI levels are significant in predicting autocratization and democratization onsets, the second polynomial function of PSDI provides strong evidence for the non-linear relationship that the PSDI has on both regime changes. In panel A, Figure 6 shows graphical results from Table A3, Models 1–3. The curve highlights the non-linear and negative relationship between PSDI and predicted probabilities of autocratization expressed in percentage points. When the PSDI is at 0.41, it is associated with the highest probability of autocratization onset at 10.23 per cent. On the one hand, this can be the result of a deterioration in party systems’ democratic levels. This would progressively lead to party systems declining from higher levels of the PSDI to levels around 0.41, making autocratization more possible. On the other hand, it can also be the case that party systems with an already heterogeneous stance on democratic values are linked with a more anti-pluralist government coalition (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024), opening the opportunity for an autocratization onset to take place.

Figure 6. Predicted probabilities of autocratization and democratization onsets by PSDI.

Furthermore, the probability of an autocratization onset is relatively high when the PSDI is between 0.20 and 0.55. This appears to confirm that while at the extremes of the PSDI, there is a much stronger commitment to democratic (top PSDI values) or authoritarian values (bottom PSDI values), the increasing disagreements and resulting heterogeneity in commitment to democratic values can result in autocratization episodes beginning.

Moving to democratization onsets, Figure 6 graphically shows the results from Table A3, Models 4–6. First, the curve is skewed on the right, and when the PSDI is around 0.30, there is a 17.29 per cent probability of democratization onset. The size of this effect is almost twice the highest probability for onsets of autocratization. One of the primary reasons is that party systems’ democratic positions are notably stronger in predicting episodes of democratization when there is a stark transition from an authoritarian to a democratic regime. This finding resonates well with previous literature on authoritarian-led democratization as well as the effects of opposition parties’ political alliances and democratization (Ong Reference Ong2022; Gandhi and Ong Reference Gandhi and Ong2019; Riedl et al. Reference Riedl, Slater, Wong and Ziblatt2020; Slater and Wong Reference Slater and Wong2022; Wahman Reference Wahman2013), which can be the result of changes in elites’ interests for regime change along with opposition parties’ electoral strategies adaptation.

Second, the PSDI seems to play a much stronger role in onsets of democratization in the authoritarian regime spectrum than in setting off episodes of democratic deepening (Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán2013; Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2023). At higher levels of PSDI where we know that most regimes are also reasonably democratic, the instances of democratization onsets decrease considerably.Footnote 10 This finding is also in line with the literature suggesting that aspects such as access to liberal rights, civil society participation, and government and public administration performance contribute to democratic deepening (Schedler Reference Schedler1998; Diamond Reference Diamond1999).

Taken together, Panels A and B in Figure 6 show that the PSDI predicts the highest likelihood of autocratization at slightly higher levels (0.41) than the highest chances of democratization (highest at 0.3). As democratization can be defined as a significant and substantial increase in democratic standards (Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2023), we would expect party-system democratic levels to also be relatively lower than already established democracies. Looking at the somehow sharp decrease in democratization’s predicted probability when the PSDI increases, this can also be linked to a ‘ceiling effect’ where highly democratic party systems are not expected to experience further democratization anymore. When comparing this result with PSDI levels and chances of autocratization, the starting point of a significant and substantial decrease in democratic standards (Maerz et al. Reference Maerz, Edgell, Wilson, Hellmeier and Lindberg2023), it is likely that a party system’s worsening in democratic commitment influences the regime transformation already at higher levels than 0.3, which is the PSDI level with the highest probability of democratization onset.

These results demonstrate the significant potential of the PSDI in predicting regime transformations in both directions, corroborating H1a and H1b. To expand on these findings, H2 and H3 posit that also a change in PSDI is associated with onsets of regime changes. Table 2 and Figure 7 present the results, and we highlight three primary findings. First, negative changes in PSDI are significantly associated with autocratization onset in the short- and mid-run. Model 1 in Table 2 shows that a one-unit decrease in PSDI per cent change since the last election is associated with an almost 0.7 per cent (e0.007 = 1.007) increase in chances of autocratization. Model 2 in Table 2 presents the same relationship but models the PSDI per cent change since two elections before any given election year. The coefficient is similar at a 0.9 per cent (e0.009 = 1.009) increase in autocratization onset with a one-unit decrease in PSDI per cent Change. Meanwhile, Model 3 shows that there is no relationship between PSDI per cent Change and autocratization onset when using the difference between PSDI and its value three election cycles before. Apparently, anti-pluralists have a limited window of up to around eight years to trigger autocratization after gaining enough strength to start affecting the structure of competition in the party system. A span of three elections is considerable (that is, between twelve to fifteen years) and recent literature suggests that such a time frame could even embed episodes of democratic resistance or turnarounds (Gamboa Reference Gamboa2022; Nord et al., (Reference Nord, Angiolillo, Lundstedt, Wiebrecht and Lindberg2025)).

Table 2. PSDI Changes over three election years and influence on regime change, 1970-2019

Note: ‘EC’ refers to ‘electoral cycle’. P-value: p<0.1+, p<0.05*, p<0.01**, p<0.001***.

Figure 7. Summary for PSDI Changes Estimates on Onset of Regime Change from Table 2.

Note: This figure summarizes results in Table 2, focusing on the estimates of PSDI per cent Change on regime changes. For each Model, we draw three levels of confidence intervals (CIs) at 85, 90, and 95 per cent. To interpret the CI, thicker lines represent bigger CIs (that is, CI = 85 is the thickest line and CI = 95 is the slimmest line).

Second, there is limited evidence of an association between short- and medium-term positive changes in PSDI and democratization onsets, hinting at the much slower process of party systems’ democratization. Yet, Model 6 in Table 2 shows how this relationship is somewhat significant when looking at PSDI per cent change between a given election and PSDI levels three election cycles before. Thus, there is some evidence to posit that positive changes in PSDI can be influential for democratization onsets if sustained across multiple elections. These results resonate with previous findings on the role of multiparty elections for democratic onsets as a slow development of democratic values (Lindberg, Reference Lindberg2006; Howard and Roessler Reference Howard and Roessler2006; Donno Reference Donno2013).

Taken together, Figure 7 summarizes the results in Table 2 by showing how the relationship between changes in PSDI and autocratization and democratization follows different patterns. This suggests that negative changes in PSDI can have strong predictive power for autocratization onsets within a short range (for example, one election span), while positive changes seem to be influential for democratization onsets only as a constant and progressive improvement. Hence, the results corroborate H2 and lend some support for H3, yet highlighting the importance of different time spans for both types of regime changes.

In the Appendix, we provide robustness checks on the presented main models. A first possible challenge to Table A3 is that the PSDI is computed according to the data structure at the election-country-year level, yet we use a country-year data structure and replace the resulting PSDI missing values with the PSDI value associated with the election through which a legislature is formed.Footnote 11 Hence, in Tables A4–A5 we re-run the same models as in Table A3 but using the election-country-year data structure, yielding similar results. Another aspect to consider is whether looking at the entire party system is a less precise predictor than only focusing on government coalitions’ democratic stances, as previous literature has consistently done (Medzihorsky and Lindberg Reference Medzihorsky and Lindberg2024; Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016). Tables A6–A7 provide evidence that re-running Models 1–6 in Table A3 reaches similar results, yet only looking at the government coalitions provides weaker results than looking at the entire party system. Another aspect to consider is whether the main results hold if we consider the commitment to democracy in party systems relative to countries’ overall democracy levels. To this end, we create the variable ‘democratic tension’ as the difference between PSDI and EDI and use this to replicate the models in Table A3 (Figure A8). The results show that when the EDI is higher than the PSDI, countries are more likely to experience autocratization, whereas democratization is more likely when the PSDI is higher than the EDI. These results are qualitatively similar to the main models, with stronger results for models on democratization. We also test the influence of the fall of the Soviet Union on regime changes in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The collapse of the Soviet Union could affect the relationship between PSDI and democratization onset as many countries within the former Soviet Union subsequently liberalized with around seventy countries democratizing between 1990-1993 (Nord et al., Reference Nord, Angiolillo, Lundstedt, Wiebrecht and Lindberg2025). In Table A9, we exclude countries directly affected by the fall of the Soviet Union between 1989 and 1999 and reach results similar to the main models. We also run the main model by replacing the logit function with multinomial logistic regressions (Table A10) and find that the results are even stronger than the main findings. To further test the main function, we run a Cox semi-parametric analysis using as time dimension the years before an episode of regime change occurs. Table A11 and Figures A15–A16 present strong evidence corroborating the main results.

Moreover, previous literature focusing on party systems also discusses whether regime changes are influenced by the party or party-system institutionalization (Casal Bértoa Reference Casal Bértoa2017; Enyedi and Casal Bértoa Reference Enyedi and Casal Bértoa2018; Kim, Bernhard, and Hicken Reference Kim, Bernhard and Hicken2023). Hence, we replace the PSDI from Table A3 with different measures of party and party-system institutionalization: party institutionalization by Bizzarro, Hicken, and Self (Reference Bizzarro, Hicken and Self2017), party-system closure by Casal Bértoa and Enyedi (Reference Casal Bértoa and Enyedi2016), and party-system institutionalization by Kim (Reference Kim2023). The results in Tables A12–A13 show that PSDI is systematically better than any of these widely used measures when predicting autocratization and democratization onsets. While Tables A14–A15 show the full results for Table 2, in Tables A16–A20 we perform a similar exercise to retest results in Table 2 as well, yielding very similar results where changes in PSDI are more precise than any of the alternative measures.

Conclusion

One of the most vivid aspects of contemporary world developments is the undermining of democracy. Assessing to what extent a party system is democratic, authoritarian, or divided in between, is, therefore, an increasingly important dimension for analyzing party systems. Yet, the literature on party systems has not developed a framework to analyze this cleavage. The existing measures of party system dimensions that structure parties’ interactions focus on left-right, GAL-TAN, ethnic, or religious cleavages representative of policy positions. Moreover, these highly influential measures typically also have limited regional and/or temporal scope. In this study, we introduce the new and comprehensive PSDI based on parties’ levels of anti-pluralism, with global coverage from 1970 to 2019. Following Adcock and Collier (Reference Adcock and Collier2001), we highlight the index’s content, convergent, and construct validity. We also provide an empirical application estimating the relationship between PSDI and regime changes. The results demonstrate a strong non-linear association with both autocratization and democratization episodes. Future research can build on this new measure to test research questions such as, but not limited to, sources of autocratization and democratization at the party-system level, the consequences of the PSDI for interstates or social conflicts, relationships between political institutions (for example, the parliament and the executive), or elected representatives and voters.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123424000887

Data availability statement

Replication data for this paper can be found at Angiolillo, Wiebrecht and Lindberg (Reference Angiolillo2024) in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9BVJGU.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and the three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions. For discussions and feedback on previous versions, we also thank Ryan Bakker, Paul Bederke, Tiago Fernandes, Laura Gamboa, Airo Hino, Ann-Kristin Kölln, Kyle Marquardt, Juraj Medzihorsky, Aníbal Pérez-Liñan, Marina Nord, Jonathan Polk, Yuko Sato, Michael Wahman, Fernando Casal Bértoa, and audiences at APSA 2023, Demscore Conference 2023, EPSA 2023, Aarhus University, University of Gothenburg, and the University Institute of Lisbon.

Funding

We recognize support by the Swedish Research Council, Grant 2018-01614, PI: Staffan I Lindberg; by Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation to Wallenberg Academy Fellow Staffan I. Lindberg, Grant 2018.0144; by European Research Council, Grant 724191, PI: Staffan I. Lindberg; as well as by internal grants from the Vice Chancellor’s office, the Dean of the College of Social Sciences, and the Department of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg. The computations of expert data were enabled by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS), partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement no. NAISS 2023/5-406.

Competing interests

None.