1 Introduction

Why do group-based economic and social disparities continue to exist in our societies and organizations? After decades of efforts, achieving inclusion and equity with now-typical diversity statements and policies has proven to be what Churchman (Reference Churchman1967) would call a wicked problem, complex and persistent. This is so for many but, importantly, not for all organizations. Some public and nonprofit organizations have achieved sustained success with diversity. An important goal for research is to identify the problematic phenomena that challenge diversity and how some organizations have overcome those challenges. Evidence strongly suggests that we, as societies, can do better through an informed organizational approach.

1.1 The Opportunity

Repeatedly over time, political and social forces arise that counter efforts to improve social justice. The stark reality in the United States is that economic progress for underrepresented groups has stagnated since the ending decades of the last century. As but one example of findings reviewed next, the Black–White wage gap for both men and women has not decreased but, rather, increased since 1980 (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Hobijn and Pedtke2017), Taking into account such realities, this monograph presents an evidence-based approach to achieving goals of inclusion, equity, social justice, and organizational performance with diversity. Its analyses identify and deal with continuing social phenomena antithetical to these goals, drawing on systematic reviews of large bodies of empirical research from multiple fields and multiple case studies of public and nonprofit organizations. These bodies of evidence lead to understandings that call for and identify a new path forward in organizations. The understandings are:

1. Contrary to popular opinion, progress on equity and social justice for underrepresented groups in the United States has stagnated for many decades.

2. Long-standing, currently dominant formal policies and practices for increasing representation of underrepresented groups have failed to produce progress on equities at the societal and workplace levels, with many of these practices being counter-effective for those groups.

3. Current political and social realities are but the most recent manifestation of underlying dynamics at societal and organizational levels that continually reproduce social disparities and lost organizational effectiveness.

4. At the workgroup level inclusion of members of underrepresented groups is a key to achieving sustained performance and equity from diversity.

5. Effective antecedents (stimulators) of inclusion are managerial practices typically adopted to increase workgroup and organizational performance. Avoiding the resistance historically engendered by formal diversity management policies, proper performance-oriented practices create task-productive interpersonal interactions among all workgroup members.

6. Differing versions of such workplace practices for inclusion are readily available to fit a particular public or nonprofit sector organization’s mission, history, and operational context.

7. “Checking the box” by adopting a diversity management statement and policy is insufficient. Achieving inclusion and equity requires managerial persistence and attention to feedback.

1.2 Research and Practice Issues for Public and Nonprofit Organizations

The findings and conclusions from recent literature reviews and key empirical studies in the fields of public administration and nonprofit governance point to the key diversity issues and challenges facing organizations in those sectors. In the public sector much diversity research has proceeded from a focus on representation, with social justice and effective mission attainment calling for representation in the organization’s workforce of populations reflecting the community and client-base being served (Sabharwal et al., Reference Sabharwal, Levine and D’Agostino2018). However, such representation, when achieved, has largely been limited to lower occupational positions, with underrepresented groups crowded into lower-level jobs and equitable representation lacking at higher levels in federal, municipal, and nonprofit organizations (Piatak et al., Reference Piatak, McDonald and Mohr2022).

Recent empirical studies published in the most prestigious journal for public administration point to the problems associated with this continuing reality and the nature of organizational practices that can overcome the problems. Regarding issues of equity, research on over 240,000 employees in 25 federal agencies finds that “as workforce diversity increases, the perception of organizational justice decreases when the relationship is moderated by an active form of diversity management” (Hoang et al., Reference Hoang, Suh and Sabharwal2022, p. 537). That is, formal organizational programs to improve workgroup diversity produce unintended effects, leading to lower, rather than improved, perceptions of justice as diversity increases. The authors note that these programs can be seen by organizational members as preferential to underrepresented groups, an issue that is investigated in detail next.

Concerning performance, Sabharwal et al.’s (Reference Sabharwal, Levine and D’Agostino2018) review of seventy-five years of research in public administration reports “there is very little empirical research that investigates the link between diversity and performance, and that line of work has produced conflicting results at best” (p. 252). They note the “call for more ‘practice-oriented’ research” and that “existing research has produced little ‘usable knowledge’” (p. 253) and report findings that standard diversity management efforts are insufficient to enhance performance, while inclusion in the form of giving employees a voice in decision-making processes does increase performance.

The main theme in the evolving research, then, is that pursuing representation through currently common diversity programs is insufficient to achieve equity and performance. Achieving equity requires that members of all groups receive formal rewards commensurate with their work accomplishments (Mowday, Reference Mowday, Porter, Bigley and Steers1991), and this is increasingly seen as dependent on a frequently missing workplace component: inclusion in critical organizational processes (Nishii, Reference Nishii2013) of all organizational members, regardless of gender and race. For underrepresented group members inclusion has been found to depend on personal elements such as the gender and ethnic composition of an individual’s social networks within and outside their organization (Jung and Welch, Reference Jung and Welch2022). Our interest here, however, is in practices that organizations and their managers can institute. Hoang et al.’s study of federal employees finds that inclusive leadership practices are associated with higher perceptions of organizational justice, indicating that certain workplace practices can generate inclusion and result in perceived justice. Similarly, contemporary research in local-level public sector organizations identifies several performance-driven workplace practices that are antecedents of inclusion: lived practices for member voice, decentralized decision-making, and teamwork are related to higher departmental-level perceptions of a positive diversity climate (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, DeHart‐Davis and Borry2022).

In nonprofit organizations recent research finds that governance decisions play a key role. Public administration literature suggests that, regarding diversity management, the main goal of organizations was to avoid legal sanctions (Sabharwal et al., Reference Sabharwal, Levine and D’Agostino2018). Similarly, boards of nonprofit organizations have been criticized for a “check the box” approach, believing that development of a diversity policy was sufficient to deal with diversity issues. By not taking seriously the call to diversify their boards, nonprofits are impeding their board and organizational performance. When nonprofits commit to board diversity with inclusive behaviors and practices, board performance improves (Buse et al., Reference Buse, Bernstein and Bilimoria2016). More recently, Evans et al. (Reference Evans, Kuenzi and Stewart2024) found that visibly diverse boards have more inclusive governance practices, positively impacting organizational performance.

In sum, research in public administration and nonprofit organizations points to the importance of inquiry that addresses core issues and extends the recent promising findings on performance-oriented workplace practices:

Why have inclusion, equity, social justice, and improved mission attainment remained so elusive, even as many organizations have adopted diversity management policies and pursued representation? What social and organizational phenomena are undermining the currently dominant diversity management programs?

What board, administrative, and managerial practices in the workplace can counter these phenomena and achieve inclusion, equity, social justice, and increased mission attainment?

Findings and issues parallel to those discussed earlier are also found in research on business organizations (Castilla & Benard, Reference Castilla and Benard2010; Dobbin et al., Reference Dobbin, Schrage and Kalev2015; Kalev et al., Reference Kalev, Dobbin and Kelly2006; Leslie et al., Reference Leslie, Mayer and Kravitz2014), indicating that the challenges proceed from social phenomena affecting all types of organizations. Accordingly, insights on the nature of these problematic phenomena can be gained from research published in many academic fields, covering various levels of analysis and types of organizations. The insights can then be adapted to the specific contexts of the public and nonprofit sectors. Here, we draw on our transdisciplinary synthesis of research, reported in greater detail in Bernstein et al. (Reference Bernstein, Salipante and Weisinger2022). The synthesis integrates empirical research in the academic disciplines of psychology, social psychology, sociology, and economics and the applied fields of management and organizations, urban studies, and health care, enabling scholars and managers in each discipline and field to leverage the knowledge generated in other fields.

1.3 Motivations for Driving Diversity with Inclusion and Equity

The stakes of succeeding with diversity are high for underrepresented groups, organizations, and society at large. Accordingly, members of nonprofit and public organizations can be motivated by either or all of four arguments, two being fundamental societal arguments for diversity with inclusion and equity and two being organizational arguments for superior mission attainment. The first fundamental argument, the moral/social justice argument, recognizes that every individual has value to contribute. From a moral perspective, many nonprofit and public sector organizations are created to improve society and therefore, should be diverse, inclusive, and equitable. The social justice perspective highlights the need to address the barriers and historical factors that have led to unfair conditions for marginalized populations. The moral/social justice argument has become increasingly relevant given the recent political and legal actions taken to inhibit diversity (see Section 10.2). These actions are eroding prior advancements in, and public opinion about, diversity and inclusion.

Second is the economic argument, based on the idea that organizations and countries that tap into diverse talent pools are stronger and more economically efficient. With labor economics analyses (Section 3) revealing that progress in reducing race/ethnicity and gender disparities has stalled, the United States is bearing a sizeable loss of economic performance. The estimated annual loss due to deficient use of human capital is on the order of $1 trillion, approximately 15 percent of Gross National Product (Buckman et al., Reference Buckman, Choi, Daly and Seitelman2021). To remedy this loss, equity and performance can be simultaneously achieved by decision-makers avoiding a taste for discrimination (Becker, Reference Becker1971) and, instead, basing personnel decisions such as hiring and promoting solely on criteria that reflect an individual’s actual capabilities for high performance. Adding to these criteria a preference for a particular group dilutes the decision’s validity and results in diminished utilization of talent for the organization and society. Workplace discrimination creates further costs for organizations as they expend effort to replace the more than two million American workers who leave their jobs each year due to unfairness and discrimination (Center for American Progress, 2012). Simply, for organizations to be more diverse and inclusive makes economic sense as they leverage the talent pools of different populations.

The third, client argument is predicated on the idea that organizations will better achieve their missions if they reflect the diversity of their client base (Ely & Thomas, Reference Ely and Thomas2001; Sabharwal et al., Reference Sabharwal, Levine and D’Agostino2018). Nonprofit and public sector clients want to see themselves represented in the organizations that serve them, and organizations with representative leadership are more likely to understand and serve their clients’ needs well. Finally, the results argument is based on the understanding that diverse teams and workgroups have the potential to perform better (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Salipante and Weisinger2022). Diverse teams can provide multiple perspectives and lived experiences that result in better decision-making and problem solving, finding better solutions to organizational and social problems. However, as we discuss next, research finds that improved performance from diversity is far from automatic, requiring organizations to create particular team conditions to achieve superior results.

Achieving performance and equity from diversity depends not only on the presence of talented, diverse individual work unit members but also on the social practices and organizational values that organizational members follow as they interact with each other to achieve their organization’s goals. From our public and nonprofit organizational cases, we identify the value and feasibility of

pursuing specific practices and values for inclusion and equity of all organizational members, and

promoting this pursuit as an avenue to superior mission attainment.

Even where “DEI” policies are under political attack, high-achieving nonprofits and governmental organizations can demonstrate to other organizations the performance, social justice, moral, client, and economic reasons for adopting workplace practices for inclusion and equity. However, we caution leaders against promoting these practices to their members as diversity management initiatives. Given the backlash accompanying DEI being politicized (see Section 4) and the reality that teamwork and other performance-driven workplace practices are antecedents of inclusion (Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, DeHart‐Davis and Borry2022), our case analyses (Sections 7 and 9) find that success with diversity and equity can result from managers and staff promoting inclusive workplace practices for team performance and mission achievement. The mission-oriented logic is a natural fit in the many nonprofit and public sector organizations whose members are committed to attaining an important societal mission. By adopting practices and values for fully including all members in mission pursuit, alert nonprofit and public organizations can both benefit from and demonstrate to other organizations the performance and equity advantages of properly leveraging diversity through inclusion (Bernstein & Salipante, Reference Bernstein, Salipante and Renz2024).

1.3.1 An Illustrative Case: Partial Success and Missed Opportunity

Girl Scouts of the USA (GSUSA) illustrates diversity policy logics, opportunities, and shortfalls (Weisinger & Salipante, Reference Weisinger and Salipante2005, Reference Weisinger and Salipante2007). During the 1990s this large nonprofit was among the first in the United States to seriously pursue racial/ethnic diversity, having a goal of membership growth. Among its girl members, although not its troop leaders, it was highly successful in greatly improving the national representation of groups previously scarce in scouting. This approach was similar to compliance approaches centered on improving representation of underrepresented groups, but it largely neglected inclusion. The human tendency to prefer engaging with similar others kept individual troops largely homogeneous, even in racially integrated schools and communities. To overcome this separation, some GSUSA councils created valuable opportunities for differing troops to interact in positive, mission- and values-driven activities at inter-troop sleepovers. However, these opportunities were too scarce and infrequent to achieve any meaningful measure of sustained inclusion. The potential for inclusion and equity from diversity was available to the organization, but a limited policy focus and resistance from some adult members hampered its achievement. This case and others are described and analyzed in Sections 7 and 9.

1.4 Requisite Analyses: The Dynamics of Complex Systems

Across the many academic disciplines that study diversity phenomena, we could find little research that has taken a system perspective on diversity phenomena or investigated dynamics driving the reproduction of diversity problems over time. Given the historical challenges, analyses that examine the dynamics of complex systems (Forrester, Reference Forrester1961, Reference Forrester1990; Mabin & Cavana, Reference Mabin and Cavana2024; Meadows, Reference Meadows2008; Sterman, Reference Sterman2002) are required to produce relevant knowledge. In contrast, assumptions of short-term causal effects of one or a few actions have proven erroneous over the longer-term. Systems thinking identifies the many factors in play, and dynamic analyses of feedback processes reveal the interplay of the multiple factors over time, pointing to actions that support or undermine the intended effects of policies.

1.5 Evidence-Based Modeling

Applying empirical findings from research studies, we model system processes to identify the reinforcing feedback loops that positively or negatively amplify change over time, creating virtuous or vicious cycles. Modeling systems dynamics in this way can guide researchers, policymakers, organizational leaders, and workgroup managers to evidence-based knowledge for effective action. Systems thinking is a causality-driven approach to describing interactive relationships among different elements within a system as well as influences from outside the system, allowing for consideration of both internal and external forces. Systems thinking enables one to describe and understand the causality and interrelations between variables using complex models. Within systems thinking we include concepts of system dynamics (Meadows, Reference Meadows2008) to emphasize feedback processes among these variables, processes that generate the system’s behavior over multiple periods of time. Systems thinking can guide leaders to attend to feedback effects in order to evolve over time a comprehensive set of policies and practices that fit their context.

Our goal is to identify virtuous cycles that accomplish desired goals over time, counteracting the various vicious cycles that have stymied progress. One example is a fundamental virtuous cycle for society driven by organizations’ productive utilization of human capital: As organizations succeed in providing more equitable career opportunities and rewards for members of underrepresented groups, those groups have greater incentives to personally pursue and collectively press for improvements in education, training, and other important social contexts, stimulating organizations to make yet more and more equitable utilization of talents from those groups over time.

Systems tools make visible the problematic dynamics that undermine most contemporary diversity efforts and, in contrast, the favorable dynamics that generate sustainable organizational successes in inclusion, equity, and work unit performance over time. Our focus is on the organizational and workgroup levels. Acknowledging problematic factors in the overall society – in educational, community and other social settings – we consider in the following sections well-validated research and illustrative cases that provide insights on how nonprofit and public organizations can productively employ the often underutilized talent available from diverse populations to boost equity and mission attainment, benefiting their organizations, all their members, and those they serve. Recent research on unintended, negative effects of contemporary diversity policies (Section 4) is incorporated in our models.

Using system modeling tools, we specify that the primary leverage point for organizations to overcome these effects and succeed with diversity is the intentional structuring of inclusive interaction practices, formal and informal workplace practices that lead to inclusive interactions among all members. While our specific diversity focus is on members’ gender and race/ethnicity, we feel strongly that many of our analyses are applicable to other forms of diversity.

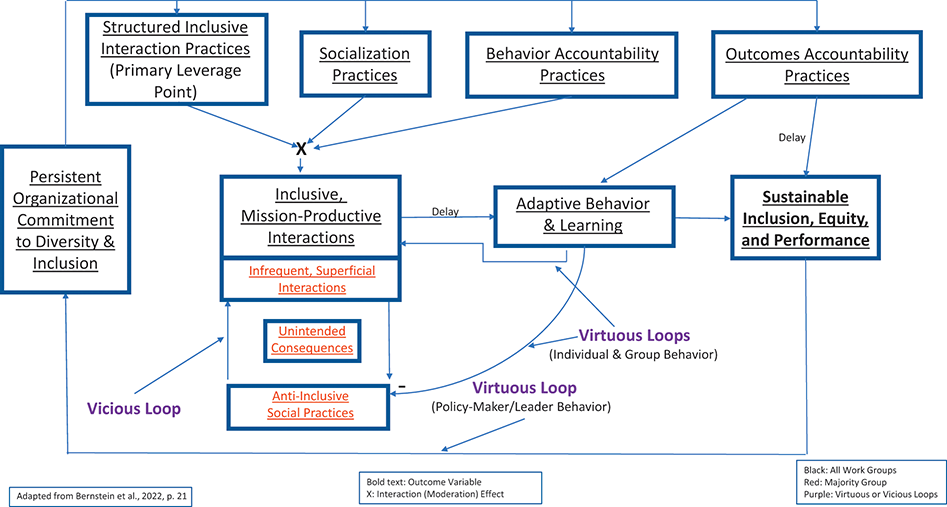

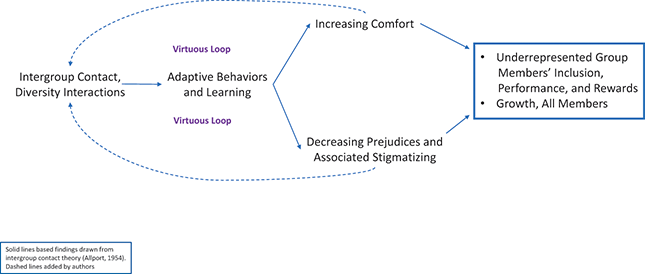

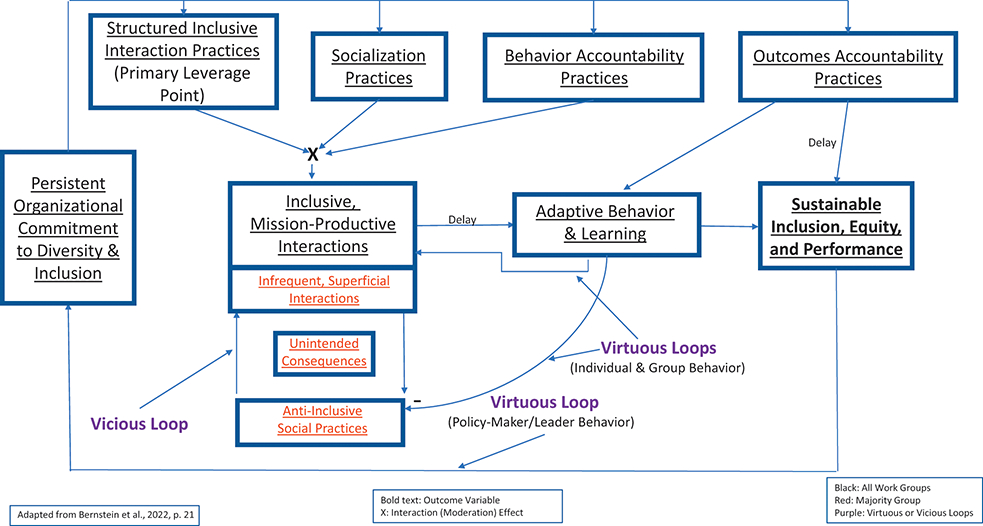

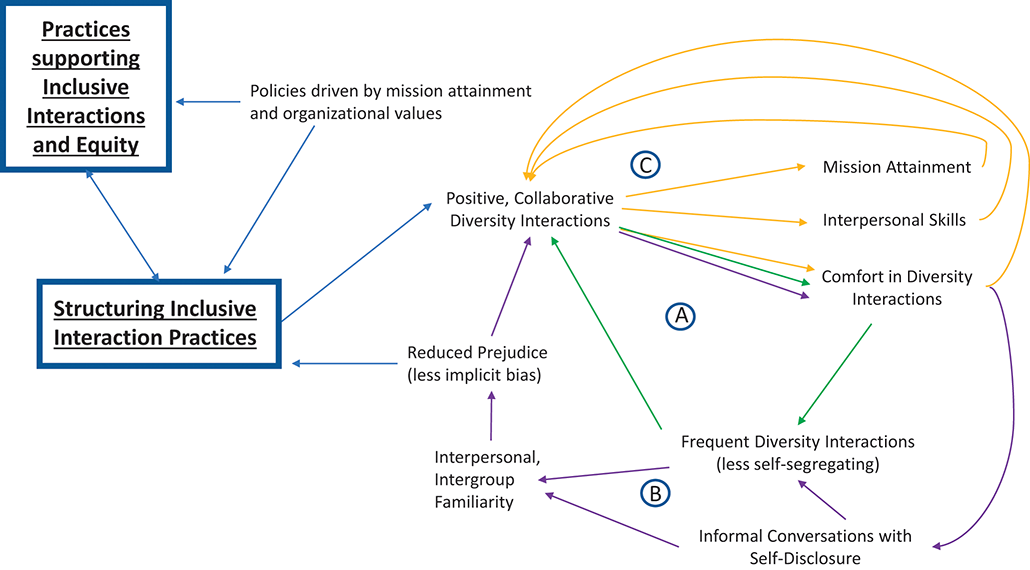

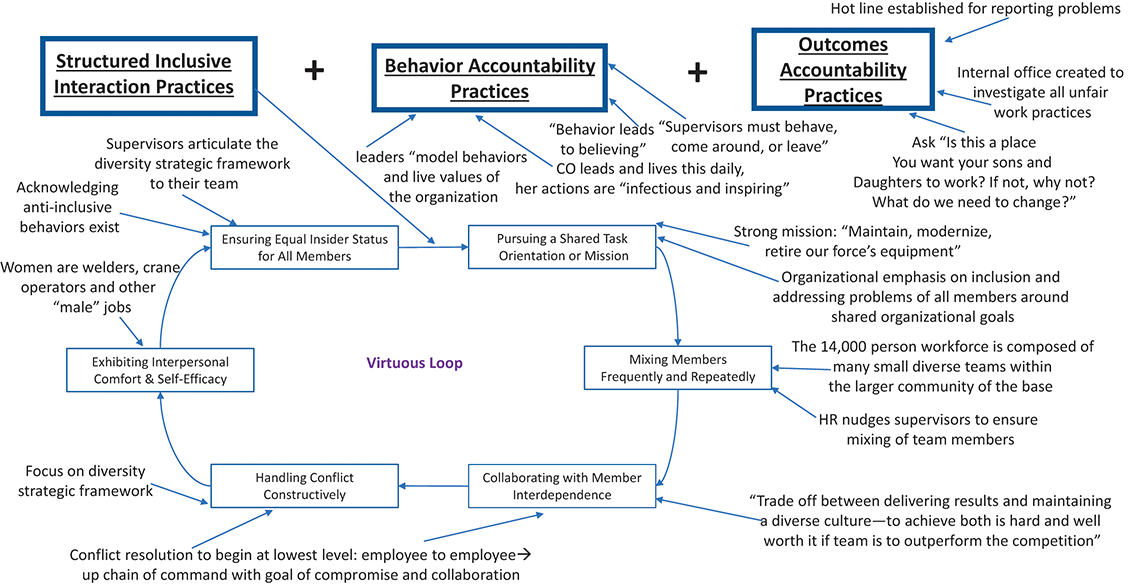

1.6 A Framework for Inclusive Interactions, Equity, and Performance

We begin with a framework (Figure 1), created and refined by a transdisciplinary synthesis of empirical research, in-depth interviews, and comparative case analyses. In the framework and the breakout models presented in the following sections, all the modeled relationships are based on research literature. Throughout, we have attempted to follow the rule that, if it is not empirically supported, then it is not in our models. However, our purpose here is not to provide all the citations that support the models’ relationships. Rather, given those empirically revealed relationships, our purpose is to identify the system dynamics in play and how they shape diversity-relevant outcomes over time. Detailed discussion of the relevant empirical literature, with additional citations, can be found in Bernstein et al. (Reference Bernstein, Salipante and Weisinger2022). Here marrying the many findings from that transdisciplinary synthesis with concepts and tools from systems dynamics reveals dynamics that impede or support inclusion, equity, and mission attainment over time.

Figure 1 Framework for inclusive interactions, equity, and performance

Figure 1 and those in the following sections use formatting that differentiates groups of individuals and types of constructs, feedback loops, and causal effects. The formatting is defined in Box 1.

Box 1 Interpreting the figures

Color coding differentiates three differing constructs:

1. Black typeface represents organizational elements (such as the nature of diversity policies and also the workforce in general, both its dominant and underrepresented group members)

2. Green represents perceptions and actions of underrepresented group members

3. Red represents perceptions and actions of dominant group members

Lines and arrows:

1. In figures with both solid and dashed lines, solid lines in the figures represent the findings from the cited research studies and dashed lines represent our attempted identification of feedback loops based on other extant research and strongly supported theories analyzed in our prior transdisciplinary synthesis (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Salipante and Weisinger2022).

2. All lines are positive, unless noted with a negative sign (–).

Other:

Outcome variables are indicated by bold font.

X’s indicate interaction or moderation effects

Purple is used to depict the feedback loops that operate over time:

1. Virtuous, policy-reinforcing

2. Vicious, policy-defeating. The vicious loops indicate the dynamic, self-reinforcing nature of diversity-undermining phenomena

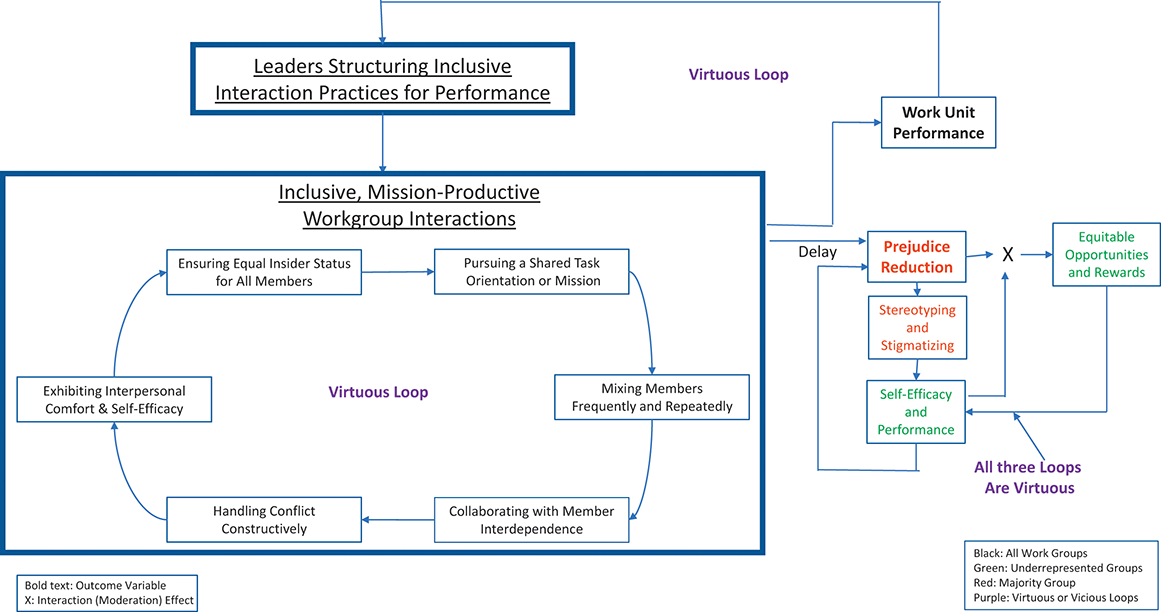

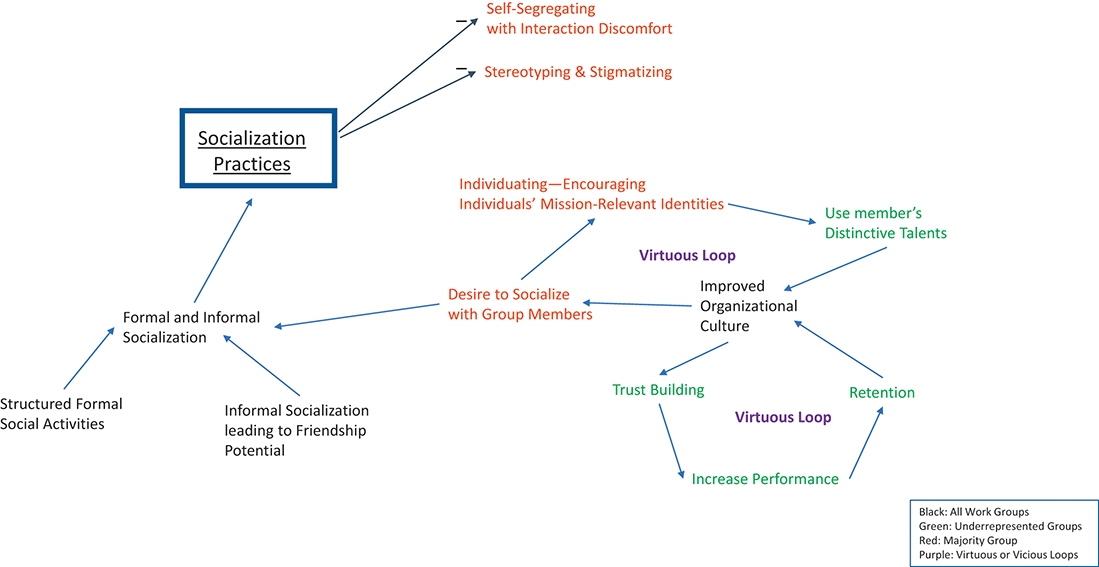

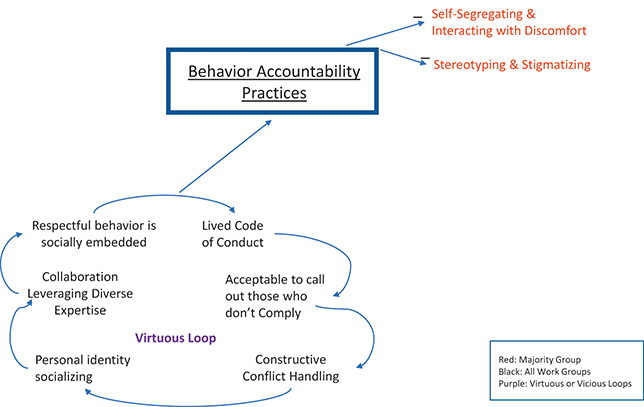

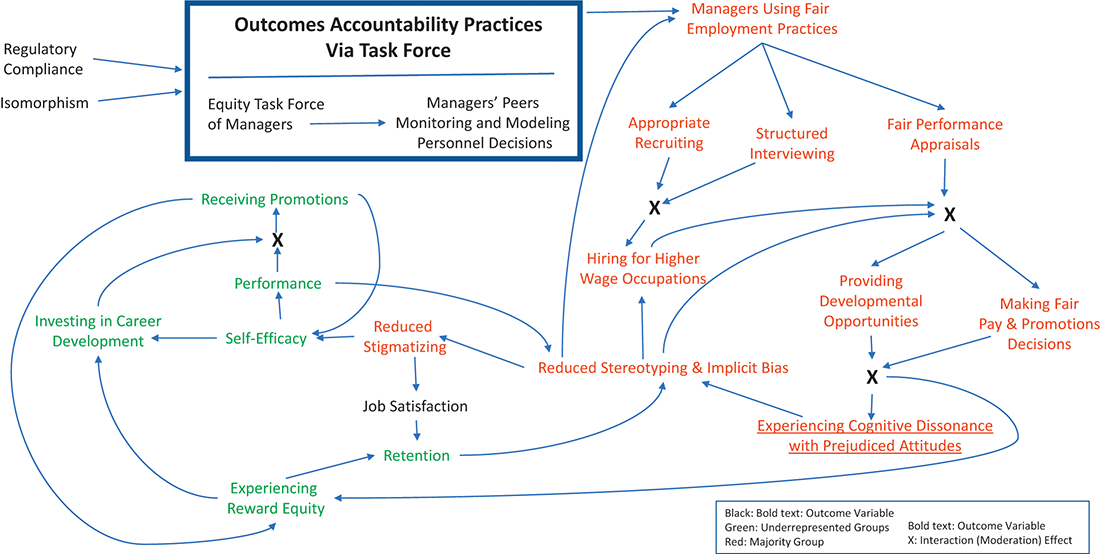

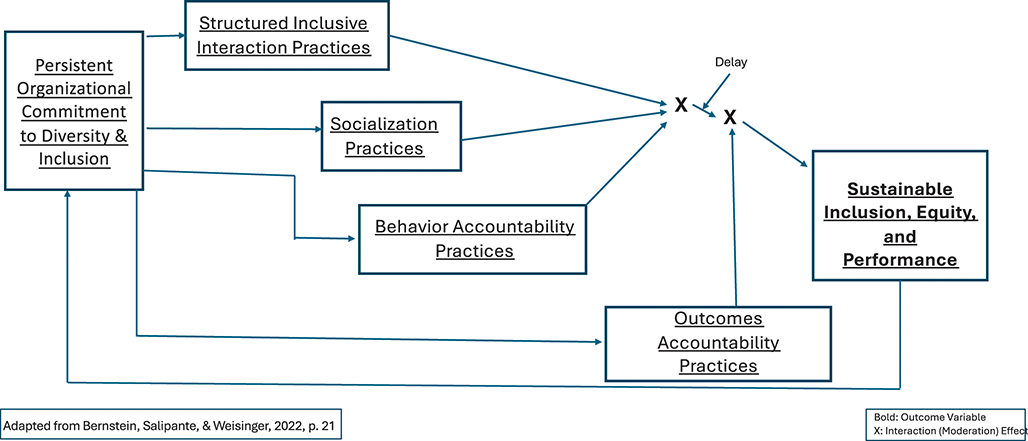

Following the call for a focus on practices, the framework serves as a flow chart. The framework highlights three sets of practices – those for Structured Inclusive Interactions, Socialization, and Behavior Accountability – necessary for enabling meaningful inclusive, mission-productive interactions among all work unit members. A fourth set of practices – Outcomes Accountability – drive Adaptive Behavior and Learning and then Sustainable Inclusion, Equity and Performance. Expanding on intergroup contact theory (Allport, Reference Allport1954; Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006), the Structured Inclusive Interaction Practices are six-fold – pursuing a shared task orientation or mission, mixing members frequently and repeatedly, collaborating with member interdependence, handling conflict constructively, exhibiting interpersonal comfort and self-efficacy, and ensuring equal insider status for all members. These practices facilitate comfortable, inclusive interactions. When combined, these six practices help members overcome three sets of anti-inclusive social practices – self-segregating and interacting with discomfort, stereotyping and stigmatizing, and making decisions based on implicit biases. These exclusionary practices impede interactions and negatively impact performance. Practices for Socialization and Behavior Accountability further foster meaningful inclusive interactions that enable work unit members to challenge their preexisting stereotypes, learn from their interactions, and alter their behavior. Experiencing Adaptive Behavior and Learning leads to Sustainable Inclusion, Equity, and Performance, with Outcomes Accountability Practices further assuring that equity is being achieved. Noted on the framework are dynamics in the form of virtuous and vicious loops indicating where inclusive, productive behaviors are reinforced or inhibited over time.

The framework provides a basis to answer our central question: How can organizations better achieve inclusion, equity, and superior performance from diversity? By applying systems thinking to the various constructs in this framework, we are able to take a deeper dive into each construct to determine where leverage points may exist, where policy resistance may arise, particularly as a result of undesired, unanticipated effects, and how vicious and virtuous loops propagate desired or undesired actions and behaviors. For example, many organizations mistakenly “check the box” on diversity efforts by requiring members to participate in diversity training, training that research finds to be ineffective or counter-effective (Dobbin et al., Reference Dobbin, Schrage and Kalev2015). It fails to create lived experiences with authentic, inclusive interactions that change attitudes and behaviors. In contrast, the evidence-based framework can guide serious pursuit of inclusive interactions to produce equity and superior mission attainment.

Our modeling, based on extant research, is not a definitive claim of causality but, rather, a call to researchers and organizational leaders to incorporate and evaluate a combination of the promising practices identified in empirical studies and captured by the modeling. Inquiry and policy practice can deploy and benefit from systems thinking, from analyses that recognize present problems and point to alternatives to currently dominant organizational policies. Accordingly, we advise organizational leaders to increase their willingness to pursue, persist, experiment with, refine, and advise and model for other organizations evidence-based policy alternatives that fit current realities and achieve individual, organizational and societal benefits from diverse workforces and populations.

1.7 Reader’s Guide

To determine what practices actually achieve inclusion and equity from diversity, along with superior performance, our models follow system dynamics concepts outlined in Section 2. For the subsequent sections, the flow is from the dispiriting findings on processes that inhibit success with diversity to a consideration of more successful processes and organizational cases that illustrate them. The flow of sections is intended to form a logical argument, but we encourage readers to make an initial scanning of sections to identify issues and practices of particular interest.

Section 2: System dynamics ideas on two weaknesses in policymaking and human behavior help to explain the lack of progress in inclusion and equity: (1) not applying systems thinking – the need to acknowledge that multiple cause-effect sequences are interacting in a complex social system, creating a wicked problem; (2) a lack of temporal thinking – the reality that change takes time as a result of delays in responses to policy changes or enactments.

Section 3: Statistics and empirical findings specify the severity and costs of the diversity problem for societies, organizations, and various gender and racial/ethnic groups, contradicting the prevailing social narrative of progress on equity and meritocracy in employment, a narrative found by research to stifle contemporary progress.

Sections 4 and 5: System models based on bodies of well-validated research evidence identify the problematic feedback loops and social processes undermining many current diversity efforts in organizations. Vicious feedback loops operating over time continually reproduce failing policy outcomes, disallowing diversity goals to be reached. This policy resistance operates primarily through backlash and the perpetuation of societal structures and processes that impede inclusive interactions and equity.

Sections 6–8: The large, well-validated body of research findings on intergroup contact theory point to a more effective way forward through instituting workgroup practices that enhance the productive interactions of all workgroup members, creating virtuous loops fostering over time sustainable inclusion, equity, and superior mission attainment. In Section 7, two cases are presented to illustrate workgroup practices.

Section 9: Comparative analysis of more vs. less successful cases from the nonprofit and public sectors illustrate combinations of effective practices and the feasibility of various types of organizations customizing the practices to their specific contexts.

Section 10: This final section discusses how dynamic system models guide organizational leaders and researchers, emphasizing for the former the role of policy persistence over time to diagnose inclusion-related problems and evolve practices that produce a combination of performance and equity, and for the latter the need to incorporate in their analyses the dynamic processes and actionable practices that affect inclusion, equity and performance.

Table 1 undergirds the framework presented earlier, summarizing the core issues and selected citations that, when analyzed with system dynamics concepts, provide insights into the lack of progress with current diversity programs and the potential, as demonstrated by successful cases, for achieving sustainable inclusion, equity, and performance through structured workplace practices.

Table 1 Core issues and citations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 System Dynamics Insights for Overcoming Policy Shortfalls

The persistence of the wicked problem of achieving inclusion and equity calls for new thinking if the current disappointing trends are to be reversed. System dynamics offers ways to understand and act on wicked problems that we, as people, typically miss. To explore and communicate these ways, we draw heavily on the work of Donella Meadows (Reference Meadows2008) and John Sterman (Reference Sterman2002, Reference Sterman2006), work that is rooted in systems concepts developed by Jay Forrester (Reference Forrester1961, Reference Forrester1990). We extend their accumulated wisdom on dynamic systems to the challenge of explaining past and current shortfalls in diversity policies. The general thrust of systems dynamics is that intentional policy actions typically lead to a combination of desired and undesired follow-on effects. Often, the undesired effects that follow cannot be readily anticipated. Table 2 provides a list of the figures presented in this section.

Table 2 Section 2 figures

| Figure Number | Description |

|---|---|

| 2 | Using System Dynamics modeling to persist and achieve policy success through ongoing monitoring and diagnosing of desired and undesired effects. |

| 3 | Basics of System Dynamics modeling for achieving policy goals. |

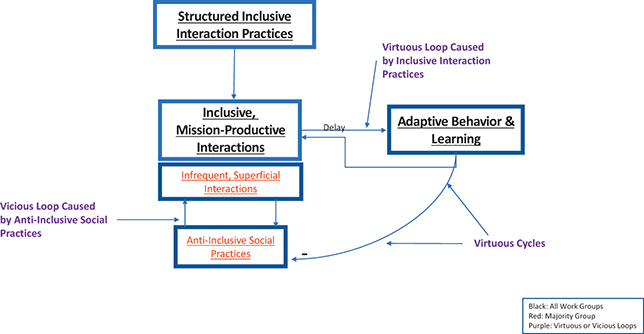

| 4 | Competing social practices in the organization support or undermine inclusive interactions, equity, and work unit performance. |

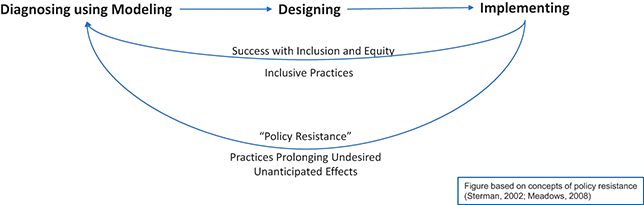

A systems-oriented policy that persists over time, as depicted in Figure 2, deals with overcoming the resulting policy resistance. Alert decision-makers repeatedly assess achievement of diversity policy goals, gather feedback to diagnose the problematic practices prevalent in the organization that are impeding better achievement, and (re)design policy elements to strengthen practices for inclusion, equity, and mission attainment.

Figure 2 Policy persistence using system dynamics modeling: Continually securing feedback to diagnose, redesign, and implement

Based on a career studying global, societal, and community systems, Meadows advises that complex social systems are not controllable but, rather, are inherently unpredictable. They are also susceptible to processes of slow decline in which a system’s members become more and more accepting of the problems the system exhibits. Because they face such complexity, unpredictability, and social acceptance of problems, policymakers’ short-term and technocratic solutions will fail to achieve desirable levels of performance. However, on the other side of the coin, social systems are self-organizing. Being unpredictable, they have the ability to create new structures and processes, such as community members coming together to engage in mutual aid in response to a catastrophe. Consequently, systems are capable of producing human benefits that exceed what policymakers are able to anticipate at any one time. While not controllable, systems can be redesigned, re-envisioned, brought into being and evolved over time through human creativity and persistence.

System dynamics enables us to examine the sources of policy resistance, which Sterman describes as how and why “today’s problems often arise as unintended consequences of yesterday’s solutions” (Sterman, Reference Sterman2002, p. 1). Underlying policy resistance are two broad issues (Repenning & Sterman, Reference Sterman2002; Sterman, Reference Sterman2002). First, complex systems are characterized by feedback loops, the interplay of multiple actors, time delays, and other processes that enable well-intentioned policy efforts to be undermined by the system’s responses over time. To aid policymakers, these feedback processes are depicted in causal loop diagrams. Second, policy development is flawed by human interpretations and heuristics that are, among other difficulties, simplistic in terms of cause-effect relationships, being subject to multiple challenges. These challenges include: disciplinary, sectoral, and organizational boundaries that narrow our focus; bounded rationality and limited information used for decision-making (Simon, Reference Simon1996); and a fundamental attribution error (Ross, Reference Ross1977) of ascribing problems to individuals’ dispositions rather than to system structure. For example, ineffective diversity training efforts (Dobbin et al., Reference Dobbin, Schrage and Kalev2015) persist due to policymakers’ simplistic assumptions about the determinants of participants’ attitudes and behavior. Another example is that narratives of women’s empowerment lead to an interpretation that progress on their inclusion and equality is the responsibility of women changing rather than the need for system structures to be changed (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Fitzsimons and Kay2018).

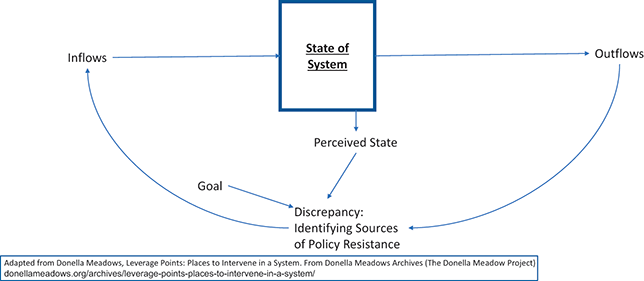

The basics of system dynamics modeling are depicted in Figure 3. A model attempts to capture causal effects that operate and shift over time (Meadows, Reference Meadows2008). Inflows of various types – for diversity issues, these are primarily social conditions and associated beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors manifested by individuals – place a system into a particular state. Over time, that state produces characteristic outflows, for example, shortfalls in achieving diversity, equity, and increased performance. Individuals can act on the system based on their perceptions of the system’s state, its outflows, and their goals. Discrepancies between outflows, system state, and goals represent feedback that can drive changes in inflows. In a well-functioning system, the feedback leads to adjustments in inflows to produce the desired behavior in a sustained fashion.

Figure 3 System dynamics modeling

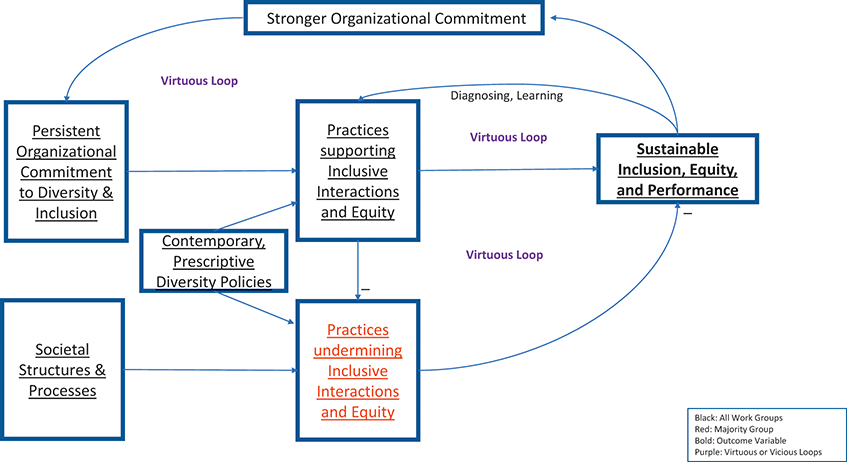

When confronted with a wicked problem, policymakers can use system dynamics models to guide them in identifying system behavior that favors or impedes attaining their policy goals. In Sections 4 through 6 we present such models based on empirical findings from multiple bodies of research. The models focus on habitual practices that members follow and that affect the system’s outflows relevant to diversity-related goals. Over time, with persistent commitment, leaders can create new inflows designed to increase the stock of their organizational members’ practices (as depicted in the center of Figure 4) that support inclusion and equity and, in turn, work unit performance. To the degree that leaders’ inflows succeed, these successes reinforce continued organizational commitment to diversity and inclusion.

Figure 4 Competing processes for inclusion and equity

However, the new policy inflows form only some of the inflows that the system then experiences, since other inflows are occurring in parallel. As depicted along the bottom of Figure 4, the stock of practices in the system includes ones that resist the intended effects of the diversity policies. These undermining practices are imported into the organization from societal structures and processes that influence how members of the organization think and behave. Following the key understanding from system dynamics outlined earlier, new policy inflows are likely to produce not only the intended results but also unintended effects representing policy resistance.

We can model these intended and unintended dynamics as due to two competing sets of social practices, with each set producing causal loops. One dynamic is driven by workgroup members following particular social practices that reinforce inclusion and equity. The competing dynamic rests on members following other social practices that undermine diversity policy goals by generating effects of exclusion and inequity unintended by the policymakers. Rather than being static, these unfavorable dynamics evolve over time as societal events occur, creating an ongoing challenge. Research reviewed in Sections 3 and 4 finds, counter-intuitively, that many contemporary diversity policies contribute to this challenge by driving social beliefs and practices that undermine inclusion, equity, and mission attainment.

With a wicked organizational problem – such as satisfying rapidly changing customer needs or, in the present case, achieving inclusion, equity and performance from diversity – the dynamic evolution of societal issues and associated social practices requires continual policy persistence by organizational and work unit leaders. Alert organizations cannot control this societal evolution but can continue to succeed by adjusting their own policies to achieve sustained inclusion and equity.

To sum up, systems-level analysis enables us to understand diversity policy resistance by modeling and diagnosing a comprehensive set of consequential phenomena that matches a system’s problematic complexity. Since the emphasis of systems thinking is on diagnosing the issues as residing in structures and practices, as opposed to blaming actors or events for a current lack of success, leaders can take initiatives to change organizational structures and practices that affect inclusion and equity. As depicted in Figure 2, by persisting with policy evolution based on diagnosing successes and setbacks, leaders can alter the organizational-level dynamics to better achieve inclusion, equity and performance. Diagnosing with systems thinking identifies relevant feedback loops in the form of virtuous cycles that reinforce the intended effects and vicious cycles sustaining unintended effects. Hereafter, these cycles are represented in feedback loops labelled virtuous loops and vicious loops. In the following sections, we use research findings to identify the elements in these loops. The challenge for leaders and researchers is to identify leverage points that drive the feedback loops so we can create and strengthen the virtuous loops and weaken the vicious loops. Systems thinking informs us about the basic nature of less and more useful leverage points, as we consider next.

2.1 Leverage Points

To identify leverage points, Meadows (Reference Meadows2008) argues the need to be as awake when engaging with systems as we are when playing a sport or accomplishing a difficult task, “dancing with the system” (p. 170), being willing to let go of our favorite solutions and open to multiple ways of seeing and acting on a system, each incomplete. Modeling a system is valuable in making our assumptions visible and open to critique, but every model is inherently limited. Value lies in bringing together a variety of models from a variety of organizational fields and academic disciplines, as we are attempting in this monograph, and recognizing the variety and varying potency of leverage points available to us.

Meadows (Reference Meadows2008) guides decision-makers by listing a dozen possible leverage points, assessing the impact and practicality of each. At the poorer end lies the use of numbers, which she notes can have short-term effects but fails to deal with the system’s behavior. A diversity policy example would be a focus on representation with prescriptive targets and quotas for hiring. These have been found to trigger backlash effects, such as beliefs that the hires are tokens and underqualified (Dover et al., Reference Dover, Kaiser and Major2020). Another relatively poor leverage point is buffers, stabilizing stocks that have the potential to impede unwanted dynamics. Buffers can be highly effective, but the difficulty lies in creating them. Regarding diversity and equity, an example is strong representation of women at higher levels in an organization, a buffer that can mitigate the use of male bias in networking and promotions. The challenge, as we document next, is that attaining a sufficient level of representation at high levels has proven to be unacceptably slow and sporadic across sectors and regions over many decades.

Middle-range leverage points, in terms of a combination of effectiveness and feasibility, including self-reinforcing feedback loops and information flows that drive the system in the direction of desired behavior, “delivering feedback to a place where it wasn’t going before” (Meadows, Reference Meadows2008, p. 157). For instance, creating a managerial task force to periodically review organization-wide information and monitor for equitable outcomes, making this information available within the organization, has been found to drive equitable managerial behavior (Castilla, Reference Castilla2015). However, its effects take time to become embedded, due to delays between behavior change and attitude change. Meadows (Reference Meadows2008) and Sterman (Reference Sterman2002, Reference Sterman2006) note that such delays raise complications for policies, eroding commitment to continue with the policies. Meadows also cautions that some virtuous loops are valuable only infrequently and tend to be dropped due to cost and other considerations, making the system vulnerable to future setbacks.

Among the more effective leverage points is rule-setting. “Power over rules is real power” (Meadows, Reference Meadows2008, p. 158). Those with rule-setting power can create deep system malfunctions or desired system behavior. For example, among our case studies, we found leaders in some high-tech, Silicon Valley firms had values and rules about mission and inclusive behavior printed on employee badges. The badges were then referred to by managers and peers to identify and sanction transgressions. Other rules are central to equity, such as informal, in-practice rules and criteria that managers use for promotions and pay raises (Castilla, Reference Castilla2008, Reference Castilla2015). Differing from formal Fair Employment Practices promoted by human resource staff, these informal rules can produce inequitable personnel decisions.

Shared goals are an important leverage point identified by Meadows. They counteract dynamics that underlie much resistance to diversity policies – namely, groups pursuing their own self-interest at the expense of the collective good, a tragedy of the commons. Shared goals encourage attending to the functioning of an entire system rather than only to the benefit of particular entities. Such goals fit the mission-achievement motivation typical among members of many nonprofit and public sector organizations. For example, we found the value of mission-achievement goals in a research unit in an elite nonprofit health care system (described in more detail in Section 6). Its leader had designed work practices and facilities that would accomplish its compelling, frequently stated goal: contributing to society’s physical health by publishing a high volume of rigorous, critically evaluated medical research studies. The goal fit the elite organization’s mission and self-concept, motivating all the unit’s members to act inclusively with each other and other members of the organization while producing personal satisfaction and career benefits for themselves.

The medical research unit’s elite self-concept is an example of another powerful leverage point noted by Meadows – paradigms. Members’ social construction of their reality as an elite unit produced sustained commitment to leveraging all members’ talents to achieve its highly valued mission. Conversely, in many other situations, a socially constructed paradigm that carries negative group-based stereotypes of inferior talent and competence for underrepresented groups impedes performance and undermines inclusion and equity. Current diversity policies, such as diversity training, are found to have failed in changing these social constructions. We identify leverage points that have proven to shift that paradigm by influencing how members of differing groups interact with each other over time.

3 Policy Shortfalls: Realities vs. Beliefs about Equity and Performance

The previous analyses help us realize that many leverage points are available, some more powerful than others, some more difficult to implement than others. Leaders’ motivation to access and experiment with these points should be based on a realistic assessment of their organization’s degree of success with gaining performance and equity from diversity. Countering a misplaced belief in progress, knowledge of societal trends gives us pause and spurs that motivation.

3.1 Sustained and Costly Policy Shortfalls That Inhibit Inclusion, Equity, and Performance

That achieving inclusion, equity and performance from a diverse workforce has proven to be a wicked problem, complex and persistent, is made clear by statistical analyses of trends in the United States. The large annual losses to Gross National Product noted earlier have, apparently, not provided sufficient motivation for an effective societal response to the problem’s complexity. U.S. national statistics on wage gaps and employment at higher organizational levels show improvements for underrepresented groups in the decades immediately following passage of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act in 1972, but since then there has been little progress and even regression for some groups. For example, reductions in occupational segregation occurred among Blacks, Hispanics, and women from 1966 to 1980, but from then into this century only for women (Tomaskovic-Devey et al., Reference Tomaskovic-Devey, Zimmer and Stainback2006). These trends continue to the present day with stagnation since 1990 in reducing wage disparities (Daly et al., Reference Daly, Hobijn and Pedtke2017), and an analytic review of studies from 2005 to 2020 showing no evidence of a decline in hiring discrimination (Lippens et al., Reference Lippens, Vermeiren and Baert2023).

These dual issues of equity and performance confront organizations as workforce diversity and migrations rise, not only in North America but globally. Race/ethnicity and gender differences among an organization’s members create the potential for either an increase or decrease in performance. As captured in the Categorization-Elaboration Model (van Knippenberg et al., Reference Van Knippenberg, De Dreu and Homan2004), decreased performance can result from tensions due to categorizing (negatively stereotyping) differing others, while the potential for higher performance rests on constructive handling of differences in perspectives and the elaboration of information for better decision-making. The competition between these two processes has proven, to the present time, to be “a wash”: A systematic review of empirical research shows that diversity has an equal potential to raise or lower team performance (Joshi & Roh, Reference Joshi and Roh2009).

Achieving the potential for organizational and economic gain from diversity is, then, problematic, far from automatic. Success requires a shift in focus from mere representation of underrepresented groups to their inclusion (Nishii, Reference Nishii2013) in productive work relationships, inclusion being a path to more effective human capital utilization. A similar theme emerges from longitudinal research on a large sample of major U.S. corporations, revealing that several well-intended diversity management initiatives designed to improve equity, counterintuitively do the opposite (Dobbin et al., Reference Dobbin, Schrage and Kalev2015; Kalev et al., Reference Kalev, Dobbin and Kelly2006). Practices found to be ineffective, even detrimental to many underrepresented groups, include mandatory diversity awareness training and several fair employment practices such as job tests for promotions. These findings call for improved policymaker knowledge and organizational practices to counter backlash that these practices trigger among coworkers, impeding inclusion (Brannon et al., Reference Brannon, Carter, Murdock‐Perriera and Higginbotham2018). Theories of social behavior identify several sources of backlash among members of dominant groups: perceived restriction of autonomy; preference for the current situation and a colorblind perspective; and beliefs that social equalities have been achieved (Brannon et al., Reference Brannon, Carter, Murdock‐Perriera and Higginbotham2018). Beliefs that employment equity has been reached through our organizations having meritocratic reward systems are especially problematic (Castilla & Benard, Reference Castilla and Benard2010). The belief in meritocracy affects not only workgroup members but also organizational leaders who then feel little need to identify and pursue prejudices and inequities.

3.2 Prevalent Inaccurate Beliefs about Inequalities and Meritocracy

At a societal level, then, two competing explanations reflect differing beliefs, often exacerbated by political debates, concerning the source of inequalities in employment and earnings:

1) Underrepresented groups are receiving the wages and occupational positions that they merit. There is inequality but equity due to meritocracy in the ways that the labor market and organizations allocate rewards.

2) Societal dynamics continue to exist that inhibit equity. Meritocracy has not been achieved.

These differing beliefs center on meritocracy and equity. If the first explanation is correct, differences in preparation (qualifications) for higher-level occupations account fully for inequalities in occupational and income attainment, such as the crowding of some groups into lower-level occupations. The differences can be due to personal choices and/or structural inequities in societal institutions. Logics that favor the personal choice explanation include women’s higher involvement in family-raising, causing interruptions in career progress. For example, research has identified gender differences in work preferences at various life stages, with women tending to favor family balance issues more at early life stages and men favoring these issues at later life stages (Mainiero & Gibson, Reference Mainiero and Gibson2018). The explanation of structural inequities is supported by research on the American educational system. Lower graduation rates of women and other underrepresented group members pursuing STEM degrees, particularly in engineering and math, are associated with everyday practices in STEM education, such as grading on a curve to weed out a fixed percentage of students regardless of their relative performance (Museus et al., Reference Museus, Palmer, Davis and Maramba2011). Existence of disparities due to such practices and, most importantly, the possibilities for ameliorating them are supported by the dramatically higher graduation rates of STEM-educated Blacks at historically Black colleges and universities (McGee, Reference McGee2020).

If the second explanation is correct – that contemporary dynamics continue to inhibit equity – we should see differences in employment decisions that reflect bias against underrepresented groups, the “taste for discrimination” that Becker (Reference Becker1971) phrased. Powerful evidence for this explanation comes from audit studies that continue to show bias in hiring. These studies have repeatedly found differential callbacks from job applications sent to employers, applications that are experimentally manipulated to be equivalent in qualifications (Bertrand & Duflo, Reference Bertrand and Duflo2017). Worse, audit studies are likely to underestimate discrimination since callbacks are largely determined by human resource management staff generally attuned to legal issues of discrimination, while biased decisions have been found to reside heavily in the discretion allowed managers on final personnel decisions (Castilla, Reference Castilla2008).

This demonstrated persistence of hiring discrimination belies common beliefs in meritocracy (Amis et al., Reference Amis, Mair and Munir2020). As examined next in Section 4, beliefs in meritocracy produce greater discrimination (Castilla & Benard, Reference Castilla and Benard2010). Contemporary research, then, reveals widespread public beliefs in a narrative of diversity progress, with this narrative driving a resistance to diversity efforts (Kraus et al., Reference Kraus, Torrez and Hollie2022).

A systems thinking perspective encourages us to ask: What effects does continuing discrimination in hiring, pay, and advancement produce over time? As we discuss more fully in the following sections, discrimination feeds a self-fulfilling prophecy of lack of talent, connecting the two competing explanations outlined earlier. One dynamic forming a vicious loop is as follows: The likelihood of discrimination against underrepresented group members decreases their economic incentives to invest in the education and training that leads to higher occupational outcomes; over time, this economically rational behavior of groups experiencing discrimination leads to their possessing inferior qualifications, reinforcing beliefs that their lesser employment outcomes are merited due to a lack of talent, competence, and motivation. Consequently, a failure to make equitable personnel decisions at the organizational level feeds stereotypes at the societal level that see and sustain inequalities as merited. Organizations that succeed with inclusion and equity can help in eroding this self-fulfilling vicious process since inclusive, fair treatment increases the incentives for self-investment. Next we further address the implications of not addressing workplace inequities.

3.3 Implications for Policies, Leaders, and Researchers

Progress on inclusion, equity, and performance has been disappointing overall. That disparities in employment are due, in part, to disparities in other parts of society, such as education, is not an excuse for overlooking bias and discrimination in our organizations and failing to make mission-attaining use of all organizational members’ human capital. As noted earlier, for most underrepresented groups overall progress in employment has ceased since the 1980s and 1990s. Where progress has continued, it has varied across groups, fields and organizations, calling for leaders and researchers to assess the nature of shortfalls to be addressed in their context. For example, women’s representation in medical schools and medical practice has improved dramatically over decades. However, in academic medicine, analyses indicate that retention and attaining of leadership positions has lagged and gender disparities in pay have not improved since 1995 (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Gunn, Kaplan, Raj and Freund2015). More broadly, for women in STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine), a consensus report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine included among its conclusions that “Bias, discrimination, and harassment are major drivers of the underrepresentation of women …; they are often experienced more overtly and intensely by women of intersecting identities (e.g., women of color, women with disabilities, … ” (Bear et al., Reference Bear, Colwell and Helman2020).

The challenge for policymakers, organizational leaders, and researchers is to identify the severity and nature of the diversity problems faced in their setting, seeking practical knowledge on policy-undermining dynamics that apply to their context, as we discuss next in Sections 4 and 5, and on practices that aid rather than detract from achieving inclusion, equity, and performance, as discussed in Sections 6 through 9.

4 Dynamics Undermining Diversity Policy Efforts

Organizational policies must do justice to the scope and complexities of phenomena that, over time, limit and undermine success in achieving inclusion, equity, and organizational performance. Building on research evidence from prior decades, recent literature reviews and studies are identifying a variety of persistent system dynamics that produce unintended, undesired diversity consequences in our organizations. The figures included in this section are listed in Table 3.

Table 3 Section 4 figures

| Figure Number | Description |

|---|---|

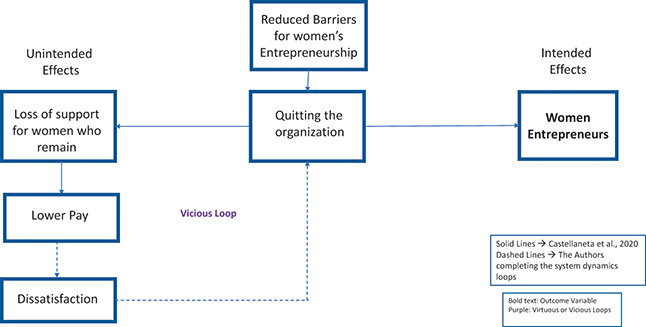

| 5 | The dynamics of intended and unintended effects of reducing barriers to women’s entrepreneurship, identifying negative effects on women who do not become entrepreneurs. |

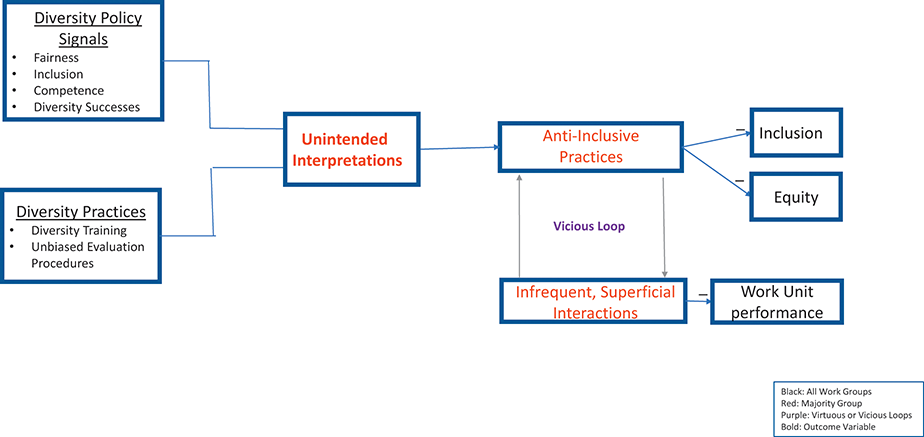

| 6 | Common diversity policies trigger unintended interpretations that reinforce anti-inclusive social practices and infrequent, superficial diversity interactions, producing a vicious cycle in workgroups that reduces workgroup performance, inclusion, and equity. |

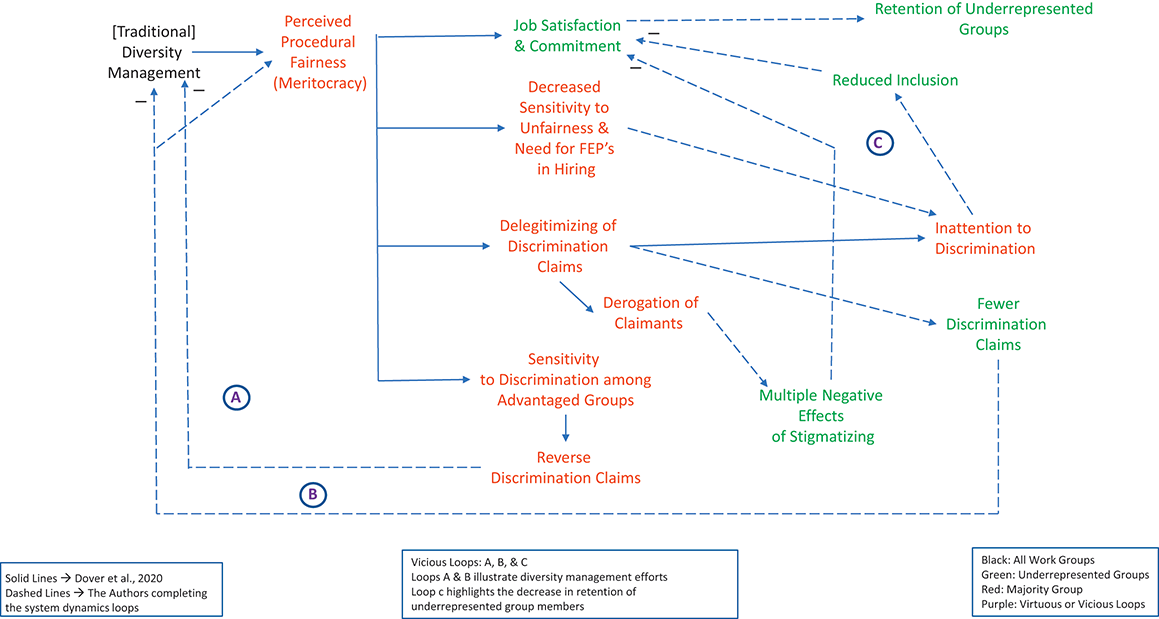

| 7 | Fairness signals of traditional diversity policies generate perceptions of meritocracy that, among underrepresented groups, support several positive outcomes and, among dominant groups, produce several negative outcomes including inattention to discrimination, derogation of claimants, and dominant group members claiming reverse discrimination. |

| 8 | Diversity training triggers competing dynamics. Two virtuous loops increase women’s advancement to high level positions, while numerous vicious loops undermine their advancement and earnings through interpretations by the dominant group that increase gender stereotyping and biased personnel decisions. |

4.1 Modeling Dynamics of Unintended Consequences

As an initial illustration of complexities and unintended consequences, consider findings from a recent empirical study investigating the effects of policies that lower the barriers to entrepreneurship (Castellaneta et al., Reference Castellaneta, Conti and Kacperczyk2020, p. 1274):

We propose that institutions that reduce barriers to entrepreneurship lead to intended consequences, increasing entry rates among individuals facing obstacles to entrepreneurship, such as women. But these regulations also have unintended consequences, decreasing the value appropriated by women who stay in paid employment, as these women lose support of their departing peers. … These effects are amplified for women in managerial positions who benefit if they leave but lose if they stay.

The dynamics of these intended and unintended effects are modeled in Figure 5. To the aforementioned findings (solid lines) we add a feedback loop (dashed lines) to capture follow-on effects of loss of support and lowered pay causing more women to leave the organization, creating yet less support for women who remain, with this vicious cycle repeating over time.

Figure 5 The intended and unintended effects of entrepreneurship policies: Problems for employed women

This phenomenon of a mixture of intended and unintended follow-on effects is but one example of system complexities that confound diversity policies. The complexities produce not only desired but also undesired dynamics that, over time, limit and undermine success in achieving inclusion, equity, and higher mission attainment. Increasingly, research studies are identifying a variety of system dynamics that are producing unintended, policy-undermining consequences in our organizations. Here, we draw on their findings as well as research-based evidence from prior decades that provides insights into the social system complexities that confound contemporary efforts to achieve inclusion, equity, and performance from diversity. By modeling the variety of system dynamics in play, we demonstrate how complex and problematic these dynamics are. However, fortunately, modeling also points to leverage points for effective policies (Meadows, Reference Meadows2008). In later sections we identify and model successful organizational policies that deal with these system complexities to produce inclusion, equity and high performance from diversity.

4.2 Findings on Unintended Effects of Contemporary Diversity Policies

Resistance to diversity policies is driven by interpretations that members draw from their organization’s diversity efforts. A meta-analysis of 110 studies (Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Kravitz, Mayer, Leslie and Lev-Arey2006) found strong Black–White differences in supportive vs. unsupportive attitudes for diversity programs. The more prescriptive the program for achieving equality in personnel outcomes, the greater the differences in attitudes, with the differences in lack of support being four times greater for the most vs. least prescriptive programs.

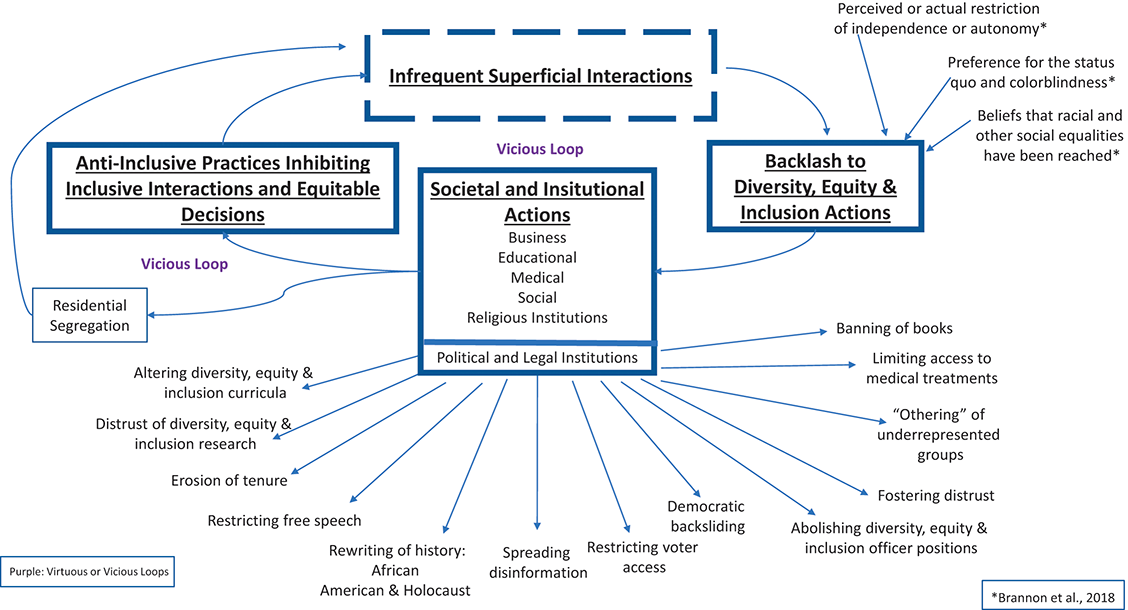

The findings from this and similar research are modeled in a general fashion in Figure 6, with unintended interpretations triggered by diversity programs leading to interpersonal behavior that, among other negative impacts, reinforces a vicious loop in workgroups. That loop is driven by the anti-inclusive social practices (such as stereotyping and stigmatizing) that are imported from the broader society and followed by some or many members of the organization. These practices, and the infrequent, superficial interactions that they produce, reinforce each other, with this vicious loop hampering inclusion, equity, and work unit performance.

Figure 6 Unintended consequences of common diversity policies and practices

The left side of Figure 6 highlights the counterintuitive findings from two highly informative studies that examine a range of unintended effects caused by contemporary diversity policies. First, a literature review of social psychology studies (Dover et al., Reference Dover, Kaiser and Major2020) identifies the de facto, signals, often unintended, that commonly implemented diversity initiatives send to organizational members. These signals trigger individuals’ interpretations of those efforts, some of which initiate and sustain resistance to the organization’s diversity policies. Second, Caleo and Heilman (Reference Caleo and Heilman2019) extensively review studies identifying processes that undermine three common diversity efforts – diversity training, emphasizing successes with diversity, and unbiased evaluation procedures – designed to counter gender bias. Contrary to expectations, Caleo and Heilman found that these efforts produced follow-on effects that sustain stereotyping and biased behavior and decisions.

Illustrating the types of dynamic phenomena creating resistance to diversity policies, Figures 7 and 8 are breakout models that detail two examples of the unintended effects found in these recent reviews of empirical studies. First, modeled from Dover et al.’s (Reference Dover, Kaiser and Major2020) literature review, Figure 7 depicts the unintended effects of fairness signals sent by diversity programs or initiatives. When reading these figures, note that solid lines represent the literature review’s findings, while the dashed lines represent our’ completion of feedback loops, with all lines reflecting research-based evidence.

Figure 7 Effects of fairness signals from diversity initiatives

Figure 8 Gender stereotyping: Competing phenomena affect gender stereotyping and advancement to high positions over time

In Figure 7, an important dynamic is that fairness signals sent as part of an organization’s diversity policies for fair employment practices (such as job tests for hiring or promoting) increase perceptions of the organization being meritocratic. These perceptions create positive effects of increased job satisfaction and commitment for underrepresented group members, providing a positive effect on their retention. However, among other organizational members, the signals tend to be interpreted in ways that lead to inattention to discrimination. The interpretations include majority group members being less sensitive to issues of unfairness and to claims of discrimination, and being more sensitive to discrimination against their (majority) group. Follow-on effects then include the delegitimizing of discrimination claims by members of underrepresented groups and derogation of those claimants.

Based on other bodies of research, we model in Figure 7 several feedback effects of these member interpretations, depicted as three vicious loops labelled A, B, and C. The effects include a weakening of diversity management efforts and, among underrepresented groups, reduced job satisfaction due to being stigmatized and excluded, and a reduction in discrimination claims. The delegitimizing of discrimination claims and the resulting inattention to discrimination lowers the inclusion and job satisfaction of underrepresented groups, creating a downward effect on their retention. Among dominant groups the reduction in discrimination claims feeds back to sustain perceptions of meritocracy and to support the perceived adequacy of the current diversity efforts. Perceived adequacy hampers the policy-persisting diagnosing and redesigning (Figure 2, Section 2) required to evolve effective policies. Over time, the various feedback effects create a self-reinforcing, policy-defeating cycle.

In sum, the intended equity effects of diversity and equity efforts such as fair employment practices are countered by workgroup members’ interpretations that claims of unfairness by underrepresented members are unjustified, leading to behaviors that erode diversity management and the inclusion and retention of underrepresented group members. Dover et al. (Reference Dover, Kaiser and Major2020) further examined the impact of inclusion and competence signals with similar outcomes of good intentions resulting in negative unintended consequences.

Unintended effects of diversity policies are similarly specified in Caleo and Heilman’s (Reference Caleo and Heilman2019) wide-ranging review of studies, identifying processes that undermine three common diversity efforts designed to counter gender bias: diversity training; emphasizing successes with diversity; and unbiased performance evaluation procedures. An example of the follow-on effects of these diversity policies is modeled in Figure 8.

In Figure 8 several aspects of diversity training produce a combination of intended and unintended effects through their influence on gender-based stereotyping. Regarding favorable effects, emphasizing the communal aspects of the organization’s jobs favors the advancement of more women to high level positions, which reinforces their communal aspects, creating a virtuous loop. Further, an increased number of women in top positions feeds another virtuous loop, with more mentoring reducing anxieties experienced by women at lower levels, reducing their probability of quitting and increasing their likelihood of advancing to high levels, an example of a system buffer (Meadows, Reference Meadows2008). Also, driving the intended result of decreased gender stereotyping is diversity training that emphasizes the value of perspective-taking (lower-left of the figure) – that is, how differing individuals take differing perspectives to interpret a particular situation, leading to the elaboration of information (van Knippenberg et al., Reference Van Knippenberg, De Dreu and Homan2004) and fuller knowledge of the situation.

In contrast, training acknowledging group differences (upper-left of figure) reinforces attitudes that bias is normal and unconscious, reducing individuals’ felt responsibility for having bias, thereby sustaining gender-based stereotyping. Several vicious loops proceed from the gender stereotyping (right side of figure). One is that biased personnel decisions by managers, sustained by gender stereotyping, constrain the number of women advanced to high level positions, eroding that diversity-favoring buffer. When diversity policy highlights the success of those few women, members tend to interpret those high performers as atypical, sustaining their gender stereotypes of women as inferior to men at leadership. Further (right side of figure), if the organization spreads the few high-level women across the organization, they tend to be seen as tokens, increasing their anxieties and quit rates and decreasing their numbers at top levels. The resulting vicious cycle is then driven by a decreased climate for inclusion (bottom-left of figure) that enables the organization’s members to maintain their gender stereotypes. Dover et al. (Reference Dover, Kaiser and Major2020) confirmed these findings by illustrating that the stereotype threat of stigmatizing leads not only to anxieties but also to diminished assessments of one’s self-competence, an additional negative impact on underrepresented group members.

In addition, Caleo and Heilman’s review examined organizational policy that emphasizes its successes with diversity. These publicized successes help in leaders’ persisting with accountability procedures that make managers’ personnel decisions more visible. Especially when combined with individuals’ desires to present themselves positively and with norms that proscribe uncivil behavior, this visibility tends to reduce members’ overt discriminatory behavior. These are the types of effects desired and anticipated by policy leaders. However, less desirable and likely to be anticipated are other effects. The policies may shift discrimination from overt to more subtle, less visible behavior, as also noted in Dover et al.’s (Reference Dover, Kaiser and Major2020) review. The consequences are important: A meta-analysis of empirical studies finds that subtle discrimination produces greater inequities than does overt discrimination (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Peddie, Gilrane, King and Gray2016).

An additional finding reported by Caleo and Heilman as increasing the likelihood of discrimination is superiors stating justifications for discriminatory behavior, which tends to legitimize managers’ engaging in such behavior even when it is overt, and more likely to be overlooked when it is subtle. Triggered by an emphasis on diversity success are two other factors that shelter discriminating behavior: members believing that the organization is procedurally fair (mirroring other findings on the undermining effects of beliefs in meritocracy) and its members are unbiased. Caleo and Heilman further found that unintended effects can be engendered by individuals tasked with making personnel evaluations. When members of underrepresented groups are the evaluators, others are more likely to see the evaluations as unfair, biased toward those groups. Those others reduce their diversity-valuing behavior, increasing the likelihood of their making biased evaluations. Another unintended effect is triggered by unbiased evaluation procedures, a fair employment practice that requires evaluators to engage in additional, more conscious thinking. These procedures can create cognitive strain that encourages evaluators to short-cut the evaluation process and rely instead on stereotypes, sustaining biased decisions. However, once recognized, these unintended effects can be countered by selecting evaluators with a high need for cognition and by training evaluators on the use of evaluation tools, reducing the strain that they experience.

The confounding overall finding from these two reviews of research is that explicitly labelled diversity policies themselves tend to reinforce various attitudes and behavior, both overt and subtle, that are discriminatory and lead to inequitable outcomes, such as lack of women advancing to executive positions, and to self-fulfilling prophecies of low competence that erode individual and group performance over time. These dynamics fit Meadows’ (Reference Meadows2008) analysis of systems that experience and then accept slow declines in policy effectiveness and performance. Even in the breakout models earlier, the causal relationships are complex and not obvious, contrasting with the more simple causal assumptions that we tend to make when formulating and implementing policies (Sterman, Reference Sterman2002). The dynamic effects of unanticipated and unrecognized feedback loops undermine policy goals, such as gender stereotyping (Figure 8) being reinforced rather than countered by diversity policy initiatives. Yet, in contrast to the repeated diagnosing and redesigning processes for effective policymaking depicted in Figure 2, many organizations continue with these long-common diversity efforts rather than assessing outcomes, diagnosing the favorable and unfavorable dynamics driving the outcomes, and revising their policies.

Since they are based on findings from social psychological studies, the policy-undermining dynamics depicted earlier cross-validate and explain the earlier-noted findings (Section 3) from longitudinal societal and organizational field studies – namely, that U.S. society and its organizations in general have failed to improve equity through commonly used diversity policies that rely on diversity awareness training and attempts to institute fair employment practices. In the following section, we examine social practices that undermine diversity policies, further limiting the success of existing diversity initiatives.

5 Policy-Undermining Dynamics Driven by Three Common Social Practices

The findings and models in Section 4 can inform organizational policymakers, work unit managers, and scholars how common diversity efforts produce unintended effects that are continually reproduced over time. To better understand and address these effects, they can draw on knowledge reviewed in this section on problematic social practices that spill over into organizations from the broader society. From research studies we identify three sets of anti-inclusive practices: stereotyping and stigmatizing different others; making decisions based on implicit bias; and self-segregating. These everyday social practices are often taken-for-granted and unconscious. They are a common part of human interactions, simplifying life and reducing cognitive strain, but in an organizational context they reduce the inclusion of underrepresented group members in productive work activities, hampering both equity and work unit performance. Table 4 describes the figures included in this section.

Table 4 Section 5 figures

| Figure Number | Description |

|---|---|

| 9−12 | The complex, self-reinforcing dynamics of three everyday, ubiquitous, anti-inclusive practices of intergroup contact – self-segregating and interacting with discomfort, implicit bias, and stereotyping and stigmatizing – that shape unwelcome diversity interactions and inequitable decisions. |

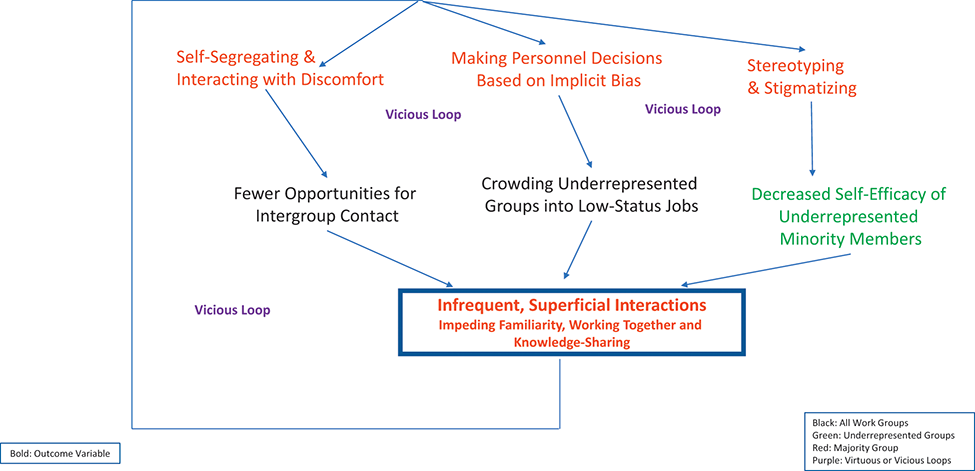

| 9 | The three anti-inclusive practices operate in a self-prophesizing vicious cycle, reducing underrepresented group members’ self-efficacy and performance by impeding interactions, collaboration, and knowledge sharing needed for high performance. |

| 10 | Self-segregating and interacting with discomfort by dominant group members self-reinforce over time, sustaining intergroup distancing and unfamiliarity. The resulting infrequent, superficial interactions produce inferior workgroup creativity and decision-making. |

| 11 | Triggered by prescriptive diversity initiatives, stereotyping and stigmatizing of underrepresented group members as incompetent and unlikeable reduces their self-efficacy and raises their anxieties, appearing to confirm the stereotypes. |

| 12 | Evaluators’ personnel decisions influenced by implicit bias negatively impact underrepresented groups’ compensation and promotion opportunities, lowering their performance motivation, increasing their quits and firings, and appearing to confirm stereotypes. |

| 13 | Combining the phenomena in the preceding models, processes among both dominant and underrepresented groups operate over time to sustain reduced inclusion, equity, and workgroup performance. |