Americans long have sought answers, even blame, for their lost war in Vietnam. Literature on the conflict’s military dimensions – at least those works arguing the war was winnable – contend the United States squandered its chances for victory in Southeast Asia because of a misguided strategy. Such narratives claim that, once President Lyndon B. Johnson deployed American ground combat troops to South Vietnam, General William C. Westmoreland, head of the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), pursued an ill-advised strategy of attrition. Rather than concentrating on population security and counterinsurgency, Westmoreland instead wrongly engaged in a conventional war aimed at little more than racking up high body counts.Footnote 1 Worse, the storyline continues, MACV’s commander implemented this strategy despite being presented with a clear alternative from US Marine Corps commanders operating in the northern provinces of South Vietnam. There, marines focused more appropriately on winning the “hearts and minds” of the local population. Their supposed successes implied that Westmoreland had missed a grand opportunity to win the war in Vietnam.

Nowhere was this better illustrated than on Life magazine’s cover in late August 1967. With his back to the camera, a young Vietnamese boy on crutches strolls beside an American marine carrying fishing poles in one hand and rifle in the other. According to editor George Hunt, Ngo Cuoc, called “Louie” by his American companions, is “bright, tough and high-spirited.” His habit of calling marines “Sweetheart” and his crutches, provided by a US medical team, point to the kindhearted warrior image so carefully constructed on the magazine’s cover. But for the rifle and military jeep in the photograph’s background, “Louie” and his fishing partner might be heading to the local pond in almost any rural American town. Despite a full-scale war raging for nearly two years, the image is one of compassion rather than destruction. Coupled with the picture, the cover story’s title, “To Keep a Village Free,” indicates that the US Marines in Hòa Hiệp had found a better way to help South Vietnam protect itself from the dangers of a staunch communist insurgency. Their mission was not only to defend but also to befriend.Footnote 2

This idyllic depiction on Life’s cover has become a mainstay of historical critiques condemning American strategy in Vietnam. Take, for instance, Andrew Krepinevich’s well-received The Army and Vietnam. In a scathing analysis of the US Army’s performance, Krepinevich denounced senior military leaders for their obsession with conventional tactics in a war requiring a more enlightened strategic approach. To the former West Point faculty member, the army “left counterinsurgency to the RVNAF [Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces], while US commanders went out in search of the big battles.” Moreover, when presented with a different approach, the marines’ Combined Action Platoon (CAP) concept, the army’s reaction “was ill-disguised disappointment, if not outright disapproval.” The missed opportunity could not be more discouraging. If only army leaders had broken free of their conventional mindsets and listened to their marine brethren, who believed that the CAP model of saturating the countryside with small, American-led security units offered a surer path toward victory, the war might well have turned out differently. “Casualties would have been minimized, and population security enhanced,” argued Krepinevich.Footnote 3

Such counterfactuals found broad acceptance in both postwar memoirs and scholarly monographs. In his 1970 account Strange War, Strange Strategy, marine general Lewis W. Walt argued that of all the innovations in Vietnam “none was as successful, as lasting in effect, or as useful for the future as the Combined Action Program.” Less than a decade later, RAND analyst Douglas Blaufarb opined that CAP tactics, “if used on a wider scale, could have made a vast difference in the war for the countryside.”Footnote 4 More recent pundits followed suit. Foreign-policy analyst Max Boot contended in 2002 that Westmoreland’s “big war stymied pacification efforts” and thus “the Combined Action Program was never more than a sideshow to the army’s conventional campaign.” In Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, John Nagl similarly blamed MACV’s commander for his narrow-minded advocacy of a “‘search and destroy’ strategy.” Despite encouraging results – Nagl contended that the CAP program “worked almost immediately” – Westmoreland ignored prevailing evidence and refused to “widen the concept to include army units.”Footnote 5 In short, the general chose a strategy of firepower over winning hearts and minds.

Such conventional wisdom, however, presents a flawed picture of American strategy under Westmoreland. MACV’s commander, like his successor Creighton Abrams, never subscribed to an “either–or” approach to confronting a political–military threat inside South Vietnam’s borders. At no point did Westmoreland concentrate solely on conventional battle at the expense of counterinsurgency. Likewise, the general never believed local civic action or pacification programs were a magic bullet to convince Hanoi’s leaders their own war was unwinnable. In reality, American strategy from 1964 to 1968 rested on a belief that South Vietnam faced a dual threat – both conventional and unconventional – requiring a similarly comprehensive response. A reexamination of American strategy under Westmoreland and the marines’ Combined Action Program reveals no “missed opportunity,” a conclusion that raises important questions about the limits of American military power abroad in the mid-1960s and how historical myths can distort interpretations of the past.

Westmoreland’s War: Myth versus Reality

If one accepts claims that the US Army in Vietnam simply conducted “search and destroy” missions supporting an imprudent strategy of attrition, the marines’ Combined Action Program surfaces as an attractive alternative. Clearly, popular narratives of the Vietnam War build from the foundation of attrition warfare. Veterans and historians alike have condemned Westmoreland for relying “mainly on massive operations conducted by brigade and division and multi-division sized forces.”Footnote 6 Rather than concentrating on population security and helping build bonds between rural inhabitants and the Saigon government, MACV’s commander chose instead to grind down the enemy through superior firepower.Footnote 7 Almost all the clichés of Vietnam are present in these indictments – attrition, search and destroy, body count. Worse, the supposed infatuation with killing the enemy led to untold civilian suffering as murder, rape, torture, and abuse, at least according to one account, became “virtually a daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam.”Footnote 8 Not merely had Westmoreland lost the war through his faulty strategy: he also oversaw the destruction of a countryside and its people.

As compelling as this narrative appears, especially for Americans seeking to lay blame for their lost war, reevaluating the historical record finds that Westmoreland waged a far different war. First, the general used the word “attrition” not simply to describe combat operations but to portray the war in Vietnam as a protracted conflict. In mid-1965, Westmoreland wrote to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Earle Wheeler that US forces would be in for the “long pull.” Describing the escalating conflict that summer, MACV’s commander saw “no likelihood of achieving a quick, favorable end to the war.”Footnote 9 Two years later, Westmoreland repeated the warning both privately and publicly. In a January 1967 message to Wheeler, the general concluded the enemy was “waging against us a conflict of strategic political attrition in which, according to his equation, victory equals time plus pressure.” That April, Westmoreland spoke at the annual luncheon of the Associated Press. While praising his soldiers’ accomplishments, the general summarily dismissed notions of gaining an easy victory. “I do not see any end of the war in sight.”Footnote 10 Even when the president called Westmoreland and Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker home in November to offer “proof” of the war’s progress to support a White House–directed salesmanship campaign, the two warned that the American effort in Vietnam was “not a short-range proposition.”Footnote 11 Attrition, in truth, meant more than just body counts.

Second, Westmoreland never subscribed to a strategic approach in which killing was the ultimate goal. The so-called search-and-destroy strategy was a term constructed by critics aiming to simplify MACV’s multifaceted concept for waging a complex war. To both his subordinates and the larger American public, Westmoreland was clear – the threat to South Vietnam required more than simply applying firepower. The general saw his principal objective as maintaining and expanding military and political control in key population areas while seeking to “restore security, develop Vietnamese allegiance to the GVN [Government of South Vietnam], and to degrade the effectiveness of the Viet Cong [VC] apparatus.”Footnote 12 Westmoreland believed pacifying South Vietnam meant destroying not only enemy main-force units but also the political infrastructure that sustained a deep-rooted insurgency.

Without question, Westmoreland’s faith in the ability of American military force to strengthen the bonds between the civilian population and the Saigon government was misplaced. It is doubtful that any foreign force entering into the long Vietnamese civil war could have fortified such bonds. Still, the general grasped the struggle’s larger political aspects. As he publicly declared in April 1967, “I think it’s impossible in view of the nature of the war – a war of subversion and invasion, a war in which political and psychological factors are of such consequence – to sort out the war between the political and the military.”Footnote 13

Westmoreland’s point about subversion and invasion is crucial when considering the viability of the marines’ Combined Action Program. The National Liberation Front (NLF) insurgency posed a multilayered threat within South Vietnam’s borders. As the 1965 MACV command history noted, in facing the insurgent menace, “it was apparent that RVNAF strength was insufficient for both offensive operations and support of the pacification program.” Nor did it help that Saigon’s government appeared “unstable and ineffective” to the point that MACV considered it in “near-paralysis.”Footnote 14 Yet the insurgency and Saigon’s political woes represented only a portion of the threat to South Vietnam’s future.

Of particular concern to Westmoreland were the armed forces of North Vietnam, “which were backing the uncompromising political stance of Hanoi with significant military capability.” MACV had to consider not only the insurgency’s political cadre and local militia units but also People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) regulars. In 1966 alone, the American command estimated Hanoi had infiltrated some 48,400 soldiers into South Vietnam. (Another 25,600 infiltrators may also have entered, though hard intelligence proved elusive.)Footnote 15 Even if Westmoreland had wanted to concentrate on securing the South Vietnamese population from the insurgency, PAVN regular units precluded him from focusing exclusively on one type of threat.

So too did the larger mission from President Johnson. The March 1964 National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 288 stated that the US objective in Vietnam was a “stable and independent noncommunist government.”Footnote 16 Westmoreland’s military strategy thus derived from the broad principle that Saigon’s government needed to function in a secure environment. Military victories alone were insufficient for achieving this ambitious political goal. Of course, security required military action, and Westmoreland developed plans that included destruction of PAVN forces, protection of the people, liberation of populated areas dominated by the NLF, and destruction of enemy base areas inside South Vietnam.Footnote 17 Thus, any focus on battle had to facilitate larger objectives of helping develop and maintain a viable local government. As Johnson articulated in late 1966, success “must also be brought about through the effective application of broad and comprehensive politico-economic-sociological-psychological programs designed both to improve the well-being of and to orient the population toward the central government.”Footnote 18 Had Westmoreland concentrated solely on body counts, he would have been out of step with the mission articulated by civilian policymakers.

Certainly, offensive operations were necessary to Westmoreland’s strategic concept. In 1965 alone, Hanoi sent seven regiments and twenty separate battalions down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail into South Vietnam. Adopting a strictly counterinsurgency approach made little sense unless coupled with plans to defeat these North Vietnamese regulars. As Westmoreland noted, the “essential tasks of revolutionary development and nation building cannot be accomplished if enemy main forces can gain access to the population centers and destroy our efforts.”Footnote 19 Still, MACV focused on population security. Despite the presence of large enemy formations, Westmoreland believed the insurgency inside South Vietnam “must eventually be defeated among the people in the hamlets and towns.” To accomplish this goal, however, meant securing the country from well-organized and equipped forces while simultaneously securing the people from “the guerrilla, the assassin, the terrorist and the informer.”Footnote 20 Westmoreland argued that American troops could contribute best in the first category while the South Vietnamese could make better progress in the second. The problem, as MACV saw it, was that communist forces were drawing the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) away from the population. Thus, if American units could construct a shield behind which the ARVN could operate, insurgents would be cut off from external support and, over time, population security attained.

MACV’s resultant three-phase strategic concept first sought to “halt the losing trend” by the end of 1965. To do so required defending political and population centers while strengthening the RVNAF and preserving areas under governmental control. Next, Westmoreland would resume the offensive to destroy enemy forces and reinstitute rural construction activities. During this crucial phase, MACV hoped to expand pacification operations by providing security to the people. This point, often underappreciated by Westmoreland’s detractors, served as the centerpiece of US military strategy inside South Vietnam. Offensive operations were not an end unto themselves. Rather, American troops would “participate in clearing, securing, reserve reaction and offensive operations as required to support and sustain the resumption of pacification.” Only by securing cleared areas could allied troops help extend the government’s control over the population. In the final phase, Westmoreland sought the insurgency’s complete destruction while offering assistance to the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) for maintaining internal order and protecting its borders. Though MACV ostensibly aimed to complete this final phase by the end of 1967, Westmoreland warned that any timeline for American withdrawal would depend on enemy resistance.Footnote 21

Without question, Westmoreland’s was an ambitious strategy, arguably outside allied troop capabilities. Yet to discount that strategy as simply “search and destroy” or “attrition” misses the nuances of a complex war and a reasoned American approach to fighting it. Far from being wedded to a conventional approach, Westmoreland realized the importance of the village war, local politics, and limiting civilian casualties. Moreover, he understood the effect a burgeoning American presence was having on the local population. While emphasizing the necessity of US forces moving at will through the countryside, he also stressed that they should “constantly demonstrate their concern for the safety of noncombatants – their compassion for the injured – their willingness to aid and assist the sick, the hungry and the dispossessed.”Footnote 22 Clearly, this balancing act required skill and maturity on the part of American soldiers and marines. Westmoreland was asking them to simultaneously destroy and build. Still, MACV’s commander realized the final battle would be “for the hamlets themselves” and, as such, American forces would be drawn “toward the people and the places where they live.”Footnote 23

Contemporary counterinsurgency doctrine supported such operational concepts. So too did prevailing theories on revolutionary warfare. The army’s field manual on “Counterguerrilla Operations” advised commanders to pay special attention to local inhabitants and assess their loyalty, morale, and strength of will for resisting insurgencies. Moreover, doctrine recommended that US forces make “maximum use of existing police and paramilitary forces.”Footnote 24 In fact, internal defense was deemed the host nation’s primary responsibility, with Americans advising and assisting. Providing security meant more than military action. Thus, as the marines’ counterinsurgency manual noted: “A number of diversified actions such as tactical operations, psychological warfare, civil populace control, and civic action (political, social, and economic) are conducted concurrently.”Footnote 25 Both doctrine and theory, however, suggested a sequential approach to counterinsurgency. Marines might conduct a number of concurrent operations but providing security ranked first among all other considerations. The message was clear. Defeating the enemy preceded pacification and government stability.Footnote 26

Of course, the enemy’s defeat required important contributions from local forces. South Vietnam’s military structure included not only the ARVN but also regional and local militia units that Westmoreland needed to consider. MACV thus proposed to accentuate the unique strengths of both US and South Vietnamese forces. Relying on their advantages in mobility and firepower, American troops would operate against large enemy formations away from population centers. Because of their “greater compatibility with the people,” the ARVN and local militia units would secure the population once cleared of enemy influence.Footnote 27 Westmoreland worried, though, that, as pacification efforts expanded in 1966 and 1967, local Popular Forces (PFs) – in essence, village militia – might not meet the demands of providing village security. Still, MACV envisioned a symbiotic relationship between American and South Vietnamese allies. US forces would help the ARVN dislodge the communists from contested locales while militia units would help control these “cleared” areas. Only then would allied operations have a “lasting effect.”Footnote 28

The varying capabilities within the South Vietnamese defense establishment matched the war’s grand mosaic. Given vast regional differences in geography, demographics, and political support for the Saigon government, strategic flexibility remained a priority throughout Westmoreland’s tenure. MACV thus determined that all operations “would be conducted through centralized direction, but decentralized execution.”Footnote 29 In reality, Westmoreland had little choice. The heavily populated Mekong Delta presented immensely different challenges than provinces along the Laotian border or the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between North and South Vietnam. Whereas residents in the southern delta encountered a largely insurgent threat, US marines in the northern provinces grappled with NLF and North Vietnamese main-force units which had infiltrated the country via the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. Hence, the conventional tactics employed by the US Army’s 1st Cavalry Division at the famous 1965 battle in the Ia Đrӑng Valley, while wholly appropriate against PAVN regiments, often proved counterproductive in more populated areas. As one MACV officer recalled, “each situation required different military tactics and a different mixture of military and political” action.Footnote 30

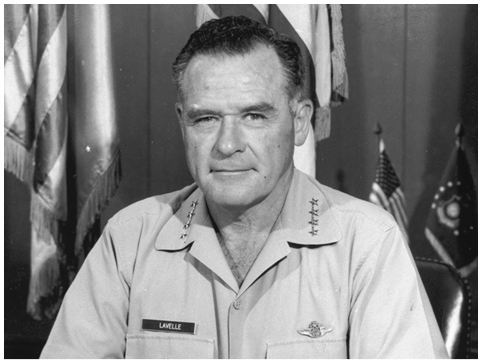

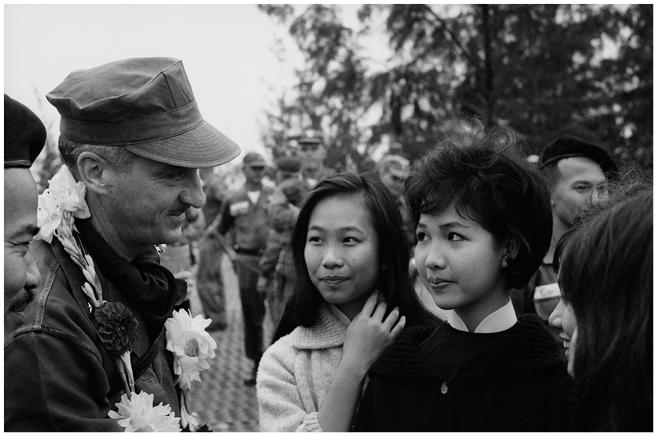

Figure 1.1 US Army officer William Westmoreland (center) with Nguyễn Cao Kỳ (right), Chief of the Vietnam Air Force, in Đà Nẵng (July 18, 1964).

The war’s mosaic nature is worth considering when evaluating arguments that a nationwide adoption of the marines’ Combined Action Program would have led to victory. Westmoreland understood early on that there was no single answer for the complex political–military conflict that was at once a war of internal subversion and one of external invasion. By necessity, MACV’s strategy was multifaceted. Never did Westmoreland concentrate solely on a “big unit war” at the expense of counterinsurgency. Historian John Prados has usefully summarized the elements of Westmoreland’s approach “as isolation of the battlefield, pacification of the villages, and main force combat.”Footnote 31 All of these elements factored into the larger objective of sustaining an independent, noncommunist South Vietnam. The US Marine Corps, however, believed they had found a better way.

The Marines Weigh In

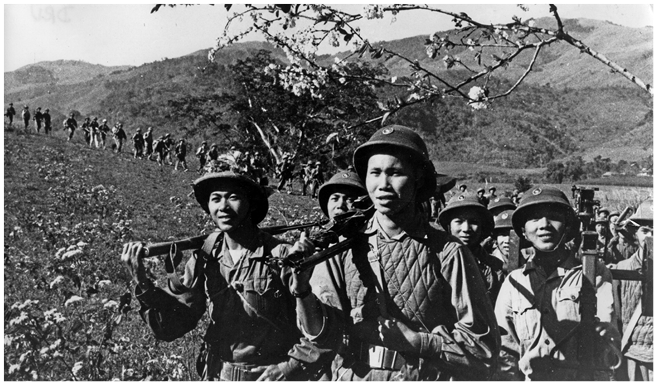

In March 1965, the first contingent of marines landed at Đà Nẵng in Quảng Nam province. Their mission, to defend American air bases supporting the bombing of North Vietnam, called for setting up three defensive “enclaves” at Phú Bài, Đà Nẵng, and Chu Lai. By June’s end, seven battalions were operating in I Corps, the five northernmost provinces of South Vietnam. Designated the III Marine Amphibious Force (MAF) under the command of Major General Lewis W. Walt, the security force had no immediate plans for conducting nonmilitary civic action programs.Footnote 32 Base security ranked as the primary focus in these early months. Walt, though, was anxious to protect the local civilian population and soon gained Westmoreland’s approval to conduct more ambitious operations against the NLF insurgency. As the marines expanded from their enclaves, they met more than just isolated guerrilla units. In August, during Operation Starlight, the marines battled a full NLF infantry regiment in the coastal lowlands near Chu Lai. Inflicting more than 700 enemy casualties, the operation indicated that protecting the population would require heavy fighting.Footnote 33

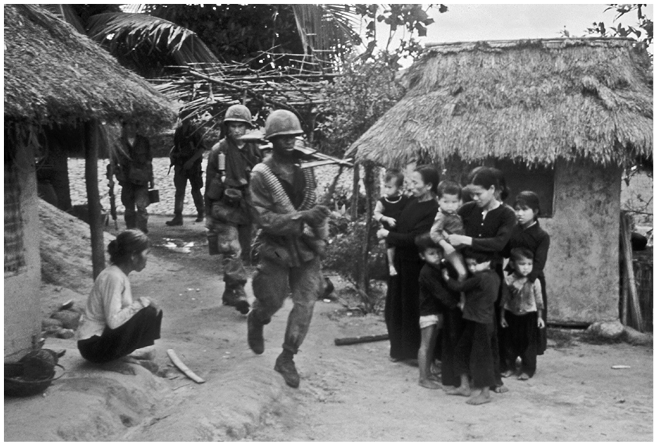

Walt, however, concluded that defending his base areas required pacifying the population and weeding out the insurgency. Security meant patrolling, and patrolling meant close contact with South Vietnamese civilians. Judging that the main threat came from local guerrillas, III MAF commanders advocated a clear-and-hold approach in which hamlets would be taken apart “bit by bit,” cleared of enemy influence, and then put back “together again.”Footnote 34 Such an approach obviously put civilians in a vulnerable position. As the official Marine Corps history noted, civilians in combat zones “presented difficulties. The first attempts to evacuate them were difficult; the people were frightened and did not trust the Marines.” Moreover, the Americans had to make grim choices when facing stubborn resistance. “Although attempts were made to avoid civilian casualties, some villages were completely destroyed by supporting arms when it became obvious that the enemy occupied fortified positions in them.” Both Westmoreland and Walt might have seen pacification as the “ultimate goal,” yet early experiences suggested counterinsurgency could be just as destructive as conventional warfare.Footnote 35

Still, Walt deemed population security key and the village war central to victory. The III MAF commander learned, though, that as marines expanded outward insurgents often flowed back into “liberated” areas. Worse, one officer recalled, the ARVN, supposedly maintaining security in cleared areas, “came not to stay, but to loot, collect back taxes, reinstall landlords, and conduct reprisals against the people.” To remedy this problem, marines in Phú Bài formed a Joint Action Company with local PFs to help disrupt NLF activities.Footnote 36 Despite these tactical innovations, Walt increasingly disagreed with Westmoreland over strategy. The MACV commander worried that continued occupation of defensive enclaves along the coastline would cede the countryside to enemy main-force units. Westmoreland later argued that, with the enemy “free to recruit in regions the Marines had yet to enter and to operate in nearby hills with impunity, every subsequent move … to extend the peripheries of the beachheads would become progressively more difficult and would make the beachheads more vulnerable.” Walt retorted that the bulk of I Corps’ population resided along the coast. Strikes against communist main-force units were necessary, but providing day-to-day population security mattered most.Footnote 37

Westmoreland, for his part, believed conventional enemy offensives required a response. The I Corps Tactical Zone (CTZ) particularly troubled him. Roughly 200 miles long and varying in width from 30 to 80 miles (50–130 km), I Corps included more than 2.5 million inhabitants living on a diverse landscape – coastal lowlands, a hilly piedmont region, and jungle highlands. Regional transportation facilities, according to one American officer, were “poorly developed.”Footnote 38 Geographical concerns aside, Westmoreland worried most about the enemy buildup just outside South Vietnam’s boundaries. All but one of I Corps’ five provinces bordered either Laos or the DMZ separating the two Vietnams. Westmoreland thus felt it urgent to “prevent the enemy from generating a major offensive designed to ‘liberate’ the provinces” in I Corps.Footnote 39 Intelligence reports of the enemy deploying anti-aircraft weapons southward and stockpiling supplies just outside South Vietnam’s borders only heightened his fears. So too did the fact that the number of main-force NLF battalions in I CTZ doubled during 1965, reaching fifteen by year’s end. In March 1966, two full PAVN regiments attacked a Special Forces camp in Thừa Thiên province.Footnote 40 Westmoreland could not ignore local insurgents within the villages, but neither could he disregard the conventional threat to South Vietnam.

While Walt and Lieutenant General Victor H. Krulak, commander of the Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, agreed with MACV on the need for a “multipronged effort,” they lashed out at criticisms that their “offensive pace” was “inordinately slow.” Walt acknowledged the fifteen confirmed enemy battalions and sensed an increasing threat in late 1965. Yet the infiltration of PAVN units into South Vietnam reinforced marine views that MACV’s strategy, aiming to “attrit the enemy to a degree which makes him incapable of prosecuting the war,” was “inadequate.”Footnote 41

In truth, Walt’s and Krulak’s criticisms missed their mark on two levels. First, the marine commanders underappreciated that enemy main-force units operating so close to sanctuaries outside South Vietnam did not require the population’s support for survival. Without question, relationships between main forces, smaller units, and hamlet organizations existed in the marines’ “three-front war.” Success in pacification, however, did not lead necessarily to starvation and thus defeat of the enemy’s big units.Footnote 42 Second, Krulak in particular mislabeled MACV strategy as simple attrition. More accurately, Walt wrote Westmoreland in late 1965 that he understood his primary missions were “to defend the established bases … to support the RVNAF effort, and to provide a security shield behind which the ARVN can develop a rural construction program.” Clearly commanders debated how best to create such a shield, yet Krulak’s assessment that MACV did not understand the critical importance of the people was simply wrong.Footnote 43

Westmoreland unquestionably saw enemy main-force units as the most pressing threat to South Vietnam’s security. Yet his skepticism about the marines’ concept resulted not from some narrow devotion to attrition but rather from a clear-sighted understanding of the war’s environment. The tasks MACV assigned to I Corps units illustrate a balanced approach with which Walt and Krulak actually agreed. Westmoreland directed the marines to develop and protect secure base areas, coordinate their operations with the RVNAF, maintain reserves for exploitation, and conduct a “vigorous rural construction program.” Stressing protection of the people, III MAF operations were to “concentrate on heavily populated areas to clear villages and hamlets in the coastal region. Such operations would require maximum mobility, discriminatory use of firepower, and flexibility in adjusting to the situation.”Footnote 44 Given concerns over the ARVN’s lackluster rural pacification efforts, Westmoreland unsurprisingly advocated marine participation in local area security. Even Krulak admitted the Vietnamese military had “little stomach” for the day-to-day task of protecting the population. Moreover, a singular approach to pacification miscalculated the reality of available manpower resources. When asked in late 1966 how many Americans were needed to secure and pacify South Vietnam, Marine Corps commandant Wallace M. Greene, Jr., said it would take “as many as 750,000 troops.”Footnote 45 Surely Westmoreland would have welcomed that number.

Leaders in the Hanoi Politburo equally debated the appropriate role of military force in their strategy to unite Vietnam. The decision to commit PAVN regulars did not come easily. Yet after tumultuous deliberations among party leaders, some of whom advocated a more cautious approach, General Secretary Lê Duẩn’s campaign to escalate the war militarily won the day. Never losing sight of the political struggle, Lê Duẩn argued it was necessary to “smash the enemy’s military forces.” Thus, the armed struggle played a “direct and decisive role.”Footnote 46 By 1965, Hanoi had committed itself to full-fledged escalation. Both the military forces and civilian population in I Corps witnessed the results. Journalist Robert Shaplen reported in 1967 that the enemy was employing “sophisticated Russian howitzers, artillery, mortar, and rockets” just south of the DMZ.Footnote 47 Marine intelligence indicated in late 1967 that forty-three PAVN and eighteen NLF battalions were operating in I Corps alone, not including the DMZ. If some Hanoi leaders still thought in terms of protracted warfare, Lê Duẩn was undeniably seeking a decisive battlefield victory to force the collapse of Saigon’s “puppet army” and the expulsion of US troops from Vietnam.Footnote 48

Thus, marine criticisms that Westmoreland’s strategy failed to account for local security undervalue Lê Duẩn’s own commitment to winning the war through decisive military action. Such assessments equally dismiss the parallels between marine and army approaches to civic action and assisting the local population. Both services agreed that aggressive patrolling and offensive operations kept the enemy off balance. Marines in Vietnam likely supported army Lieutenant Colonel John McCuen’s contention that local “militia should be the backbone of self-defence.” Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smithers’s belief that “the Viet Cong ultimately must be challenged and defeated in the village and the hamlet where they maintain their primary effort” would also have gained approval.Footnote 49 One US Army War College student in early 1968, assessing the two services’ approaches to civic action, found the concepts adopted by the two to be “identical.” Even in South Vietnam, Westmoreland took interest in the marines’ County Fair program despite concerns that pacification-oriented programs might dissipate US strength and leave American units vulnerable to enemy main-force attacks.Footnote 50

Programs like the County Fair – in which marines surrounded a village to root out insurgents while concurrently establishing dental and medical aid stations, conducting a census, and providing “native entertainment” – illustrated a population-centric approach.Footnote 51 Officers such as Walt and Krulak might acknowledge the presence of PAVN regulars in I Corps but they still believed that defeating the insurgency would lead to local security and the enemy’s ultimate downfall. Marines participating in Operation Golden Fleece, consequently, sought to protect farmers during the harvest season. If the NLF were kept from collecting rice taxes, the population might see clear rewards from receiving governmental protection. Yet whether through commodity distribution or medical care, the marines’ “emphasis was on short-term, high-impact, low-cost projects.”Footnote 52 Few questioned whether such projects would be sustainable, especially in the absence of American troops and support. But, by the summer of 1965, the marines had already convinced themselves that they alone held the key to victory in Vietnam.

CAPs: The False Alternative

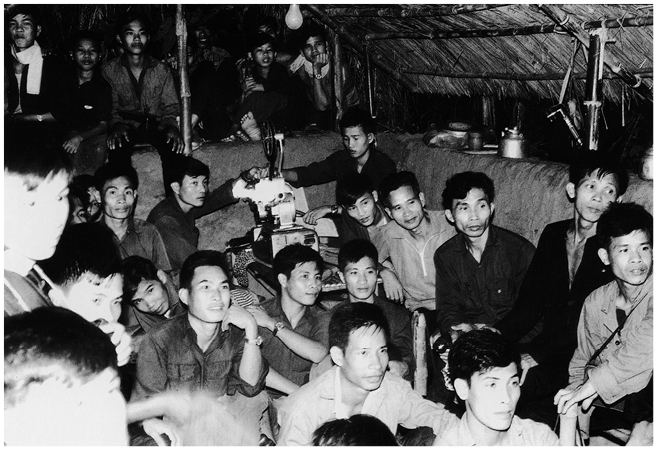

Still tied to their enclaves in mid-1965, marines at Phú Bài drafted plans to incorporate local Popular Forces into their base security system. By integrating militia platoons with marine rifle squads, the allies might enlarge their enclaves thanks to additional manpower from these newly combined units. Marines would enter a nearby village and provide military training to the PFs, while patrolling the local countryside and participating in civic action. Encouraged by upbeat reports, Walt authorized an expansion of the program in January 1966. By July, III MAF had thirty-eight Combined Action Platoons spread across the three marine enclaves. Each of these CAPs consisted of one thirteen-man marine squad and a PF platoon of thirty-four South Vietnamese.Footnote 53 According to one veteran, the scheme was simple. “If the PFs could be properly trained in firearms and squad tactics, if they could be instilled with pride and discipline, they just might be transformed into a viable, cohesive unit to augment the CAP Marines in the villes.” Paternalistic notions aside – could Americans truly instill pride in rural villagers? – the marines did their best to coordinate with Vietnamese district chiefs. Though Walt wanted to establish seventy-five CAPs by year’s end, fifty-seven combined platoons were operating by the opening of 1967, an impressive growth even if it was not as much as Walt had hoped.Footnote 54

The program’s expansion meant that recruiting capable marines for CAP duty quickly became a concern. Though ostensibly admitting only volunteers, the program accepted many men who were “volunteered” by their commanders. Moreover, participants needed a level of maturity to train local militiamen while facilitating a village’s economic and social growth. A CAP School at Đà Nẵng consequently taught a wide array of subjects, from Vietnamese language and customs to civic action and patrolling techniques. An emphasis on military training illustrated that many CAP marines were not infantrymen but came instead from combat support units.Footnote 55 More importantly, the volume of tactical instruction belied arguments that marines promoted a less violent approach to counterinsurgency. Of all the CAP pacification progress indices, “destruction of organized VC military forces” ranked first. Thus, the training of local militia endeavored to “bring the PF soldier to a state of military proficiency by which he is capable of providing his own village/hamlet defense.” Certainly, CAP marines supported “nation-building activities,” but contemporary directives on village pacification made clear that security mattered most. Thus, CAP members heard familiar tasks in their mission briefs: seek and destroy the Viet Cong, defend against VC attacks and subversion, and develop the PFs’ ability to resist the insurgency.Footnote 56

Such phrases should not surprise, given received wisdom on the relationships between security and pacification. Marines presumed that, once they gained the trust of the local militia and then the people, villagers would provide them with intelligence on the NLF’s military operations and political infrastructure. In short, the marines believed “security for the rural population remained the basic requirement for pacification.” Senior leaders at MACV agreed wholeheartedly. Ambassador Robert Komer, head of MACV’s revolutionary development program, noted that “sustained territorial security” was the “indispensable first stage of pacification.”Footnote 57 Perhaps, but did progress in security truly lead to pacified areas? Given that MACV defined pacification as linking the South Vietnamese villager to a distant central government in Saigon, such notions rested on dubious hypotheses. Not only was defining and measuring security difficult but, even once the area was secured, many villagers found little reason to throw their support behind a shaky Saigon government. CAP members surely aspired to a “unity of interest between the South Vietnamese villager and the individual Marine.”Footnote 58 Yet too often the local populace maintained its own agenda while navigating through a complex war in which the threat of returning insurgents made throwing one’s open support behind American troops a dangerous proposition.

As the CAP program expanded, so too did opportunities for daily contact with the rural population. Official reports suggested encouraging results. A combined action unit in a village usually served to keep the indiscriminate use of American firepower away, surely important for building relations with local militia. Between August and December 1966, some 39,000 Popular Forces had deserted, yet none involved troops assigned to combined action units. Other figures noted that PFs assigned to CAPs were achieving impressive “kill ratios” against the Viet Cong. One report boasted that these trends “underscore the improved military performance that is possible through the melding of highly motivated professional Marines with heretofore poorly led, inadequately trained, and uninspired Vietnamese.”Footnote 59 The lessons were clear. With the proper leadership, local militia could defeat the NLF insurgency, provide security to the population, and help turn the tide of a stalemated war.

Below the surface, however, problems were brewing. The “crash course” in language and cultural instruction left marines ill equipped to deal with the intricacies of South Vietnam’s village life. As journalist Frances FitzGerald found, American troops walked “through the jungle or through villages among small yellow people, as strange and exposed among them as if they were Martians.” Because many battalion commanders resisted giving up their best marines, the quality of CAP members ran the gamut from “outstanding to abysmal.”Footnote 60 Thus, through a lack of professional education, persistent language difficulties, the environment’s unfamiliar nature, and the uneven quality of the marines themselves, the CAP program actually exposed larger issues with American intervention in Vietnam. One marine made a common assumption that potentially undermined the very presence of combined action units. “Anyone seen or heard moving around in the dark of night was considered to be VC and shot without hesitation.” Such aggressiveness may have kept local insurgents off balance but also risked innocent civilian casualties as marines shouldered the responsibility for village security. ARVN Lieutenant General Nguyễn Đức Thắng, for example, opposed the combined action concept because he felt the South Vietnamese were “inclined to sit back and let the Marines” do all the work.Footnote 61

In fact, the Popular Forces remained a nagging weakness. Lieutenant Colonel William R. Corson, the CAP program’s first director in February 1967, argued that PFs were “the building blocks upon which a successful strategy in Vietnam could have been based.”Footnote 62 While many marines sympathized with their ill-equipped, untrained allies, harsh realities undermined Corson’s lofty aspirations. For one thing, district and village chiefs controlled PF units, not the marines. CAP sergeants and corporals thus found their influence circumscribed by a separated chain of command. As advisors, marines could coordinate and cajole but not command. Edward Palm, a CAP patrol leader, noted that this separation inhibited relationships with the local militia. “Despite numerous suggestions, complaints, and threats, we were never able to form integrated, cohesive patrolling teams. It was the luck of the draw every time out.” Perhaps unavoidably, Palm recalled the “inevitable suspicion” that “our PFs were in league with the enemy and were tipping them off about our patrols.”Footnote 63 True, PF soldiers were a mixed lot. If marines coming from combat service support units “lacked skills in scouting and patrolling,” some PFs joined up for the sole reason of avoiding conscription into the regular army. Thus, the marines’ official history arrived at a somber evaluation. “The PFs were to provide continuous security in the hamlets, but events had proved conclusively that they were incapable of carrying out their mission.”Footnote 64

If local militia effectiveness proved elusive, the growing conventional threat in I Corps during 1967 equally placed strains on the CAP program. As Hanoi sent more PAVN units into South Vietnam’s northern provinces, marine commanders dispatched their own troops forward into battle. Walt found his Vietnamese counterparts slow to pick up the pacification slack. Worse, large-scale military operations not only ravaged the countryside but also drove thousands of villagers out of their homes and into resettlement camps. Even before the “border battles” of late 1967, at least 300,000 people in I Corps had become refugees. The Tet Offensive in early 1968 caused a further spike in the number of displaced persons.Footnote 65 Not only did Combined Action Platoons struggle to meet demands of this human suffering, they found it increasingly difficult to maintain their own security. While Walt hoped to expand the CAP program, his combined action marines were suffering two and half times the number of casualties as their PF counterparts. So many CAPs had been overrun during the Tet Offensive that III MAF decided “to reduce their vulnerability by operating thereafter as mobile units without a fixed base.” Though controversial, the pronouncement meant the marines more closely mirrored the mobile advisory concept adopted by MACV in mid-1967.Footnote 66 Walt and Krulak might disparage Westmoreland’s focus on the “big unit war” but Lê Duẩn’s commitment to military action left them little choice but to follow suit.

Because of this dual threat – from outside South Vietnam’s borders and inside its villages and hamlets – the marines’ aspirations of providing lasting population security ultimately came up short. Without question, CAPs put their shoulders into it. In a two-month summer period of 1966, the combined action unit at Fort Page engaged in more than seventy firefights. During the 1967 national election period, III MAF as a whole conducted an average of 1,240 small-unit patrols, ambushes, and company-sized search-and-destroy missions a day. The results, however, proved disappointing. Los Angeles Times correspondent Jack Foisie found that, even “after the areas behind the US line of advance have been cleared of the enemy, harassment continues unless the villages are garrisoned.”Footnote 67 Yet III MAF never possessed the manpower to sustain its security advances. Moreover, a garrison state hardly encouraged loyalty to Saigon’s government. Marines involved in both large-unit and combined action operations surely made inroads against the insurgency by keeping the enemy off balance and driving wedges between the population and the NLF. The question of sustainability, though, remained. As one senior ARVN officer recalled, the “security attained was not a guarantee that it would be immune to enemy spoiling actions and that the trend was irreversible. The results only reflected the situation at a certain time; they did not represent the kind of solid, permanent achievements that defied retrogression.” One CAP veteran was more succinct: “We had managed neither to protect our village nor secure the support of the people.”Footnote 68

Contemporary literature, however, presented a sanguine picture. Laying the foundation for future “lost opportunity” narratives, marines highlighted the number of villagers voting in the 1967 election. Mayors, once “scared off by the Viet Cong,” were returning to their hamlets. The Marine Corps Gazette boasted of militia taking “heart from the Marines’ firepower and combat aggressiveness” and that civic action was having a “significant role in the transformation” of villages under the Corps’ protection.Footnote 69 Corson himself offered up impressive figures. In hamlets with CAPs, four out of five hamlet chiefs resided full time in their homes. “In hamlets without a CAP,” the program director claimed, “29 per cent have functioning hamlet councils; in those with a CAP 93 per cent have reached this level of progress.” Corson even maintained in a 1967 interview with the Washington Post that 1,000 marines were providing security for 250,000 people. (Journalist Ward Just called the remark “startling.”)Footnote 70 Even civilian think tanks such as the Hudson Institute offered measured praise. One 1967 report acknowledged that the CAPs had “not eliminated the infrastructure in every hamlet,” nor “have they ever been able to feel they could leave a village safely behind.” Nonetheless, they promoted an enhanced “mobile defense capability … based on local intelligence.” As the report concluded, the combined action approach “should be applied to a solid mass of villages, as they [CAPs] have not been up to now.”Footnote 71

Despite these glowing testimonies, the marines’ inability to link security with social and economic development plagued the CAP program and illustrated fundamental inconsistencies with the larger American presence in South Vietnam. In areas in which they operated, combined units often increased the level of security among the local villages and hamlets. Yet physical control of the population hardly addressed social grievances or economic hardships. In truth, development rarely achieved “revolutionary” levels. In large part, the Saigon government was still grappling with ways to extend its influence into the rural countryside. As The Pentagon Papers authors realized, “despite their good intentions to work through the existing GVN structure, the Marines found in many cases that the existing structure barely existed, except on paper, and in other cases that the existing structure was too slow and too corrupt for their requirements.”Footnote 72 Too often the governmental chain from hamlet to Saigon was either broken or indifferent to the people’s needs. As much as marine officers wanted to help win villagers’ “allegiance and loyalty,” no foreign occupation force could serve as a surrogate for functioning local government. And no amount of tactical skill in providing village security or in training PF militia could overcome inherent weaknesses within the South Vietnamese political community. Too many rural people simply felt out of step with their government in Saigon.Footnote 73

To his credit, Westmoreland gave I Corps’ leadership space to experiment with CAPs while confronting the PAVN threat across South Vietnam’s border. Arguments that MACV vetoed plans for expansion of the program fall flat. In the end, the Marine Corps itself allocated less than 2 percent of its manpower to CAPs.Footnote 74 In late 1967, for instance, 1,343 marines and 2,074 PF members were assigned to combined action units. Never did the program exceed 2,500 marines, even when III MAF reached its peak of roughly 85,000 troops in 1968. Despite such a large presence, Westmoreland reasoned that III MAF controlled only 2 percent of the terrain and 13 percent of the population in all of I Corps.Footnote 75 As with “security,” the word “control” surely held diverse meanings. Still, the few villages in which the CAPs operated hardly served as a paradigm for marine operations in the country’s northernmost provinces. Westmoreland correctly realized, given Hanoi’s intentions, that scattered combined action units did little to secure the population from the main-force threat. In Douglas Blaufarb’s words, the marines’ failure “to link the various CAPs together into an interlocking and mutually supporting network” only exacerbated the MACV commander’s concerns.Footnote 76 Marines, however, tended to blame such shortcomings on Westmoreland’s strategy of attrition.

While this popular narrative has appealed to a broad audience for decades, it ignores the realities behind MACV strategy and the tactical problems and solutions shared by the US Army and Marine Corps in Vietnam. In his official report on the war, Westmoreland noted that “cordon and search” and County Fair operations, “first developed by the Marines,” were adopted by all ground commands. Though Walt disagreed with MACV’s emphasis on larger, offensive operations, he conceded during and after the war that he could not ignore enemy main-force units.Footnote 77 Moreover, Westmoreland argued that he “simply had not enough numbers to put a squad of Americans in every village and hamlet.” Although Krepinevich later countered that “it was not necessary to place army squads in every village simultaneously” if one followed the “oil spot” principle of steady expansion, at least some veterans had doubts. One CAP member disputed that “we could ever have found enough Marines with the intelligence and sensitivity to make it work on a large scale, nor could we have provided the language and cultural training.”Footnote 78 Critics of America’s lost war, however, concluded that “if only” Westmoreland had followed the marines’ approach, the war “might have” turned out differently.

Conclusions: The Perils of Mythmaking

Proponents of the CAP alternative have long relied on counterfactual arguments that, under closer scrutiny, call into question whether Westmoreland missed a grand opportunity to win the war. In truth, US Army units experimented with pacification just as the Marine Corps did – oftentimes, with similarly mixed results. In the 1st Infantry Division, operations such as Rolling Stone sought to balance the interrelated fields of civic action, psychological warfare, and combat operations. By providing long-term security to the population in Bình Dương province, the division hoped to achieve its primary objective of opening the area to “RVN economic and military influence.”Footnote 79 Similar goals guided the 25th Infantry Division. In May 1966, Westmoreland directed commanders to work more closely with their ARVN counterparts “in order to improve their morale, efficiency and effectiveness.” Soon afterwards, the 25th instituted the Combined Lightning Initial Project (CLIP), modeled on the marines’ Combined Action Program, to help achieve the division’s pacification goals. Soldiers not only trained local PFs, but also conducted clear and hold missions to “help expand the security ‘oil spot’” around the division’s Củ Chi base camp. In the 4th Infantry Division, operating along Cambodia’s border, the “Good Neighbor” program equally sought to balance local security with the threat posed by PAVN main-force units.Footnote 80

The experiences of these US Army divisions directly challenge popular “lost war” narratives. Army commanders weighed offensive operations against pacification efforts just like their marine brethren. The failure of both services says more about the inability of Americans to resolve underlying problems within the South Vietnamese political community than it does about US military strategy. CAPs simply could not achieve the “credible permanence” so necessary for gaining the population’s true support.Footnote 81 Especially after the 1968 Tet Offensive and the de-Americanization of the war, villagers were unconvinced the marines would not abandon them. Lacking a long-term commitment to their security, many rural peasants deemed it too risky to support the Saigon government over the NLF. Thus, Americans remained little more than an occupation force. In the process, persistent questions over the legitimacy of the government of South Vietnam made any gains against the National Liberation Front fragile at best.Footnote 82 True, the NLF’s influence waned in the years following Tet, but it seems doubtful though that any expansion of the CAP program would have been enough to break the communists’ will. In short, there were some political issues that military force simply could not resolve.Footnote 83

Perhaps this uncomfortable truth helps explain why the false alternative of the marines’ Combined Action Program remains so congenial. In the aftermath of Vietnam, Americans wanted to believe there was a better way, that victory lay within their grasp. The alternative, though, was a myth. At its peak in 1969, there were only 114 CAPs for an I Corps population of roughly 2.5 million people. Evidence also indicated that in the “‘softer’ areas of civic action, psychological operations, and general institution- and nation-building” CAPs never performed all that well.Footnote 84

Yet, long before the war’s end, the marines already had judged their program a success. In May 1968, Krulak called on his colleagues to “stand up to their Army critics and extol the ‘proud’ record of the Marine Corps in Vietnam.” In Krulak’s view, his officers would have to defend the Corps’ “right to fight by reciting its record of ‘achievement’ in Vietnam” since “our postwar survival may well turn on our ability to articulate our contribution.” Suppressing the limits of the CAP program thus not only helped to honor the sacrifices of young marines but, perhaps more importantly, to solidify the Corps’ reputation in a war already being condemned by critics as a failure. Krulak, in a large sense, was setting the foundations for a key myth of the Vietnam War: Westmoreland’s strategy of attrition had flopped while the Marine Corps’ strategy of population security had measured up.Footnote 85

Though such narratives have found receptive audiences over the past five decades, especially those hoping to salvage one military branch’s reputation after the American loss in Vietnam, the reality proves much more complicated. Westmoreland never made exclusive choices between attrition and counterinsurgency. The Combined Action Program thus ranked as one among many tools used by American military officers to help sustain a tenuous South Vietnam government under assault from both political and military agents. There existed no “magic solution” to the dual threat of external invasion and internal subversion.Footnote 86 Hence, the CAP “alternative” should be viewed as historical myth built by proud marine officers and uncritical military historians. Certainly, studying the merits of the marine approach offers valuable historical perspectives. But myths based on “if only” arguments do little to further our understanding of the Vietnam War. By judging that war only through stories we find congenial, through narratives in which victory always is possible, history loses its functionality for deeper understanding. In the end, counterfactuals based on false alternatives take us only so far.

At 11:30 p.m. on August 4, 1964, in Washington, DC, President Lyndon Johnson informed the American public that he had ordered air strikes on North Vietnam in response for the apparent attacks by North Vietnamese patrol boats on US Navy ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. At that moment half a world away, fifty-two navy fighters from the carriers USS Ticonderoga and USS Constellation flew toward patrol-boat bases at Phúc Lợi, Quảng Khê, and Hòn Gai, and the oil storage depot at Vinh. The air strikes, dubbed Operation Pierce Arrow, wrecked half of North Vietnam’s small torpedo-boat flotilla and almost one-fourth of its oil supply, but the attackers did not emerge unscathed. Anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire claimed two A-4 Skyhawks, killing Lieutenant Junior Grade Richard Sather and forcing Lieutenant Junior Grade Everett Alvarez to parachute from his stricken aircraft. Alvarez would remain a prisoner of war of the North Vietnamese for eight long years.

At the time of the air strikes, few if any Americans realized that the raids signaled the start of an extended application of air power that would deposit 8 million tons of bombs on the landscape of Southeast Asia between 1964 and 1973. Half of that total fell on South Vietnam, the United States’ ally in the perceived struggle against communist aggression. Roughly 3 million tons fell on Laos and Cambodia, so-called neutrals in the Vietnamese conflict. The remaining million tons landed on North Vietnam, with the bulk of that falling during the Operation Rolling Thunder air campaign of 1965–8.Footnote 1 Despite the enormous amount of ordnance dropped, and the vast displays of technology dropping it, two years after the United States removed its forces from the war, South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia were communist countries.

Did the inability of bombing – and innumerable airlift and reconnaissance sorties – to prevent the fall of South Vietnam demonstrate the limits of air power, or did it reveal that the strategy that relied heavily on air power’s kinetic application to achieve success was fundamentally flawed? From the vantage point of more than a half-century after the bombing began, and more than forty years after the last bomb fell, the answer to both questions remains yes. Yet the two questions are intimately related, and answering them reveals the enormous impact that a political leader can have on the design and implementation of an air strategy, especially in a limited war. Ultimately, the air wars in Vietnam demonstrate both the limits of air power and the limits of a strategy dependent on it when trying to achieve conflicting political goals. The legacies of the air wars in Vietnam remain relevant to political and military leaders grappling with the prospects of applying air power in the twenty-first century.

The reliance on air power to produce success in Vietnam was a classic rendition of the “ends, ways, and means” formula often used for designing strategy. Air power was a key “means” to achieve the desired “ends” – victory – and how American political and military leaders chose to apply that means to achieve victory yielded the air strategy that they followed. Much of the problem in Vietnam, though, was that the definition of “victory” was not a constant. For Johnson, victory meant creating an independent, stable, noncommunist South Vietnam. His successor, President Richard Nixon, pursued a much more limited goal, one that he called “peace with honor” – a euphemism for a South Vietnam that would remain noncommunist for a so-called decent interval, accompanied by the return of American prisoners of war and the end of the United States’ Vietnam involvement.

For American air leaders as well as Johnson, the million tons of bombs dropped on North Vietnamese soil counted far more than those that fell elsewhere in terms of helping to achieve the desired political objectives. Rolling Thunder offered the promise of ending the war independently with air power, while the bombs falling on South Vietnam promised a ground victory that air power had supported. In the end, a victory of any sort that achieved Johnson’s objective of a noncommunist, stable South proved impossible to obtain with American military force. Many air leaders, however, viewed Johnson’s political restrictions as the key reason that air power had failed to achieve independent success during Rolling Thunder. They pointed to the 1972 bombing as an example of what unfettered air power could achieve, and many focused specifically on Nixon’s eleven-day December bombing effort known as Operation Linebacker II. Yet those air commanders who argued that a Linebacker II in 1965 would have “won the war” then failed to see that conditions in 1965 were not the same as those in 1972. Moreover, the objective of Nixon’s aerial onslaught differed significantly from Johnson’s goal of an enduring noncommunist South and was much easier to achieve, particularly given the type of war confronted by American air power in 1972.

The Strategic Foundations of American Air Power

Vietnam proved an especially thorny problem for American air leaders because it did not suit their expectations. After finally achieving the holy grail of service independence in 1947, the air force had become the United States’ first line of defense in the anticipated “general” war against the Soviet Union. That defense was in fact an offense, in which Strategic Air Command’s (SAC) bombers were the centerpiece of the designated strategy. “Massive retaliation,” the guiding principle of President Dwight Eisenhower’s defense policy, promised a tremendous assault with nuclear air power against the Soviet heartland should either the Soviets or a proxy Soviet state launch an attack against the United States or its allies. The concept suffered as a credible option, but the air force ingrained the emphasis on an independent aerial victory in its doctrine. Air leaders realized that air power had failed to win a victory in Korea, but they viewed the limited war there as an anomaly, especially given Eisenhower’s endorsement of massive retaliation. Although they realized that such a limited conflict might recur, they also believed that readiness for general war – a synonym for nuclear combat – sufficed for wars of lesser magnitude.

The air force’s preparation for general war on the eve of Vietnam hearkened back to the prophecy of Billy Mitchell, the teachings of the Air Corps Tactical School, and the perceived effectiveness of strategic bombing in World War II. Mitchell had maintained that air power alone could defeat a nation by paralyzing “vital centers,” which included great cities where people lived, factories, raw materials, foodstuffs, supplies, and modes of transportation.Footnote 2 All were essential to wage modern war, Mitchell had written in the aftermath of World War I, and all were vulnerable to air attack. Moreover, he deemed that many such targets were fragile, and wrecking them promised a victory both quicker and cheaper than one achieved by surface forces. Air power could attack vital centers directly, avoiding the senseless slaughter that had characterized World War I land combat. Bombers would wreck an enemy’s will to fight by destroying its capability to do so, and the essence of that capability was not its army or navy, but its industrial and agricultural underpinnings. Eliminating industrial production “would deprive armies, air forces and navies … of their means of maintenance.” Air power also offered the chance to attack the will to fight directly, but Mitchell thought that bombers did not necessarily have to kill civilians to wreck a nation’s will to resist.Footnote 3

Mitchell’s conviction that air forces could achieve an independent victory in war by such “beneficial bombing” became a hallmark of Air Corps officers who promoted his vision of independent air power founded on the bomber. Basing many of their assertions on their study of American industry and population centers, they refined Mitchell’s notions into an “industrial web theory” that offered a blueprint for how to wreck an enemy state with air power. After World War II, many American airmen viewed the bombing of Germany and Japan as a vindication of such theories. Although bombing had not singlehandedly defeated Germany, the air campaign against the German homeland had significantly damaged its ability to wage war.

The result was an independent air force with a doctrine geared to achieving an independent victory. Enough similarities remained between the notion of an industrial web and the damage rendered to Germany and Japan for American airmen to make the theory their doctrinal cornerstone. Published a few months after the Eisenhower administration announced its massive retaliation policy, Air Force Manual 1-8 defined strategic air operations as attacks “designed to disrupt an enemy nation to the extent that its will and capability to resist are broken.” Such operations would be autonomous, “conducted directly against the nation itself,” rather than auxiliary operations supporting friendly land and sea forces against an enemy’s deployed armies and navies. The authors concluded that destroying petroleum or transportation systems would cause the most damage to a nation’s will to resist. Only “weighty and sustained attacks,” however, would succeed in wrecking either system.Footnote 4

On the eve of sustained combat in Vietnam, this mindset portended ill for the US Air Force. Although their doctrine stated that the industrial web theory applied to “modern” nations, many airmen equated “modern” to “all,” and in Vietnam they would futilely try to determine the key industrial component that made agrarian North Vietnam tick. Part of the problem was that the airmen’s predecessors had designed the industrial web theory based upon their own vision of the United States, and that vision may not have been accurate. Part of the problem was also that post–World War II airmen had transformed the notion into a guideline for nuclear attack, and the prospects of nuclear bombing did not translate exactly into actual warfare, especially for an agrarian nation like North Vietnam. Yet air force doctrine taught that they did translate, and that preparation for nuclear war sufficed to ready the air force for combat at any level. That belief received a significant boost in October 1962, when the threat of SAC B-52s, supplemented by a fledgling intercontinental ballistic missile force, compelled the Soviet Union to back down during the Cuban Missile Crisis. If the threat of bombing could make the Soviets – the United States’ mightiest potential enemy – retreat, surely that threat would make other, lesser, nations fall into line as well. So believed many American airmen and political leaders as the United States looked for a quick, cheap solution in Vietnam.

Launching Rolling Thunder

With the Saigon regime teetering on the verge of collapse in early 1965 to National Liberation Front (NLF) insurgents and their North Vietnamese allies, air power appeared to offer the answer to South Vietnam’s survival when American political and military chiefs agreed to initiate Rolling Thunder. As to how bombing North Vietnam would yield an independent, noncommunist South Vietnam, there existed a wide disparity of opinion, ranging from the signal air power would send to the North Vietnamese – that bombs would ultimately destroy their heartland and its nascent industrial apparatus – to the signal that it would send to the United States’ South Vietnamese allies – that it would bolster their fighting spirit, making them fight harder and cause them to prevail against the forces of the NLF and the contingent of North Vietnamese troops supporting them. Although many airmen believed that North Vietnam lacked the Soviet Union’s will to resist, and that the threat of aerial destruction would force Hồ Chí Minh to surrender, their motivations for bombing the North also subscribed to their doctrine: they believed that the NLF, which formed the vast bulk of the enemy forces in South Vietnam, could not fight without the support and direction of the North Vietnamese, and that bombing North Vietnam would deny the NLF the capability to keep fighting. Lyndon Johnson and his political advisors endorsed this perspective as well in spring 1965. The notion was the fundamental premise of Rolling Thunder, and one that American airmen would continue to support after Johnson’s political advisors had given up on it. Unfortunately for American leaders, the premise was fundamentally flawed.

Although American political and military leaders frequently stated that the enemy waged guerrilla warfare, they also assumed that the destruction of resources necessary for conventional warfare would weaken the enemy’s capability and will to fight unconventionally. During the Rolling Thunder era, however, the enemy rarely fought at all. Hanoi had only 55,000 North Vietnamese troops in the South by August 1967; the remaining 245,000 communist soldiers were part of the NLF.Footnote 5 None of these forces engaged in frequent combat, and the NLF intermingled with the Southern populace. Enemy battalions fought an average of one day in thirty and had a total daily supply requirement of 380 tons. Of this amount, they needed only 34 tons a day from sources outside the South, a total that consisted of mostly ammunition; the NLF and the People’s Army of North Vietnam (PAVN) troops obtained food from rice fields in the South.Footnote 6 Seven two-and-a-half ton trucks could transport the 34-ton requirement, which was less than 1 percent of the daily tonnage imported into North Vietnam. No amount of bombing could stop that paltry supply total from arriving in the South. Sea, road, and rail imports averaged 5,700 tons a day, yet Hanoi possessed the capacity to import 17,200 tons. Defense Department analysts estimated in February 1967 that an unrestrained air offensive against resupply facilities, accompanied by the mining of Northern harbors, would reduce the import capacity to 7,200 tons.Footnote 7 The amount of goods that the communists shipped south “is primarily a function of their own choosing,” the Joint Chiefs remarked in August 1965.Footnote 8 Their appraisal remained valid throughout Rolling Thunder. Still, by fighting an infrequent guerrilla war, the NLF and PAVN could cause significant losses. In 1967 and 1968, two years that together claimed 25,000 American lives, more than 6,000 Americans died from mines and booby traps.Footnote 9

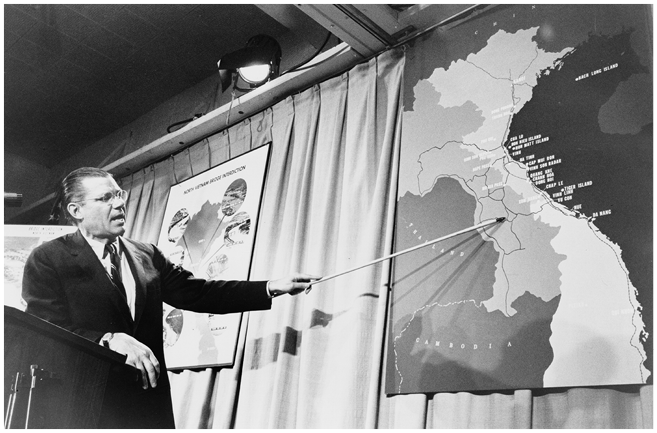

Initially, though, American political and military chiefs agreed that the NLF could not function without Hanoi’s support. Air force chief of staff Curtis LeMay, and General John P. McConnell, who served as LeMay’s vice chief and succeeded him as chief of staff on February 1, 1965, called for a concentrated air attack ranging from sixteen to twenty-eight days against transportation centers, bridges, electrical power facilities, and the sparse components of North Vietnamese industry. Admiral U. S. Grant Sharp, the commander of Pacific Command, who controlled the forces that would conduct such an attack, eagerly endorsed it, as did Lieutenant General Joseph H. Moore, the commander of the 2nd Air Division in Saigon, who directed many of the air force aircraft that would participate. To air commanders, the “sudden, sharp knock” of a three-week air offensive would not just disrupt North Vietnam’s war effort; it would also disrupt the fabric of Northern economic and social welfare – or, at the minimum, threaten its functioning, much as American bombers had threatened the Soviets in October 1962. American leaders understood that the North Vietnamese received the bulk of their war-making hardware from the Soviets and Chinese, and that Hồ Chí Minh could boast of only a single steel mill, one cement factory, and fewer than ten electric power plants. Yet those leaders also surmised that the threat of bombing could hold the meager Northern industrial apparatus “hostage” to the danger of attack. They believed that Rolling Thunder would creep steadily northward until it threatened the nascent industrial complexes in Hanoi and Hải Phòng, and that Hồ Chí Minh, being a rational man who certainly prized that meager industry, would realize the peril to it and stop supporting the NLF. Denied assistance, the insurgency would wither away, and the war would end with the United States’ high-tech aerial weaponry providing a victory that was quick, cheap, and efficient.

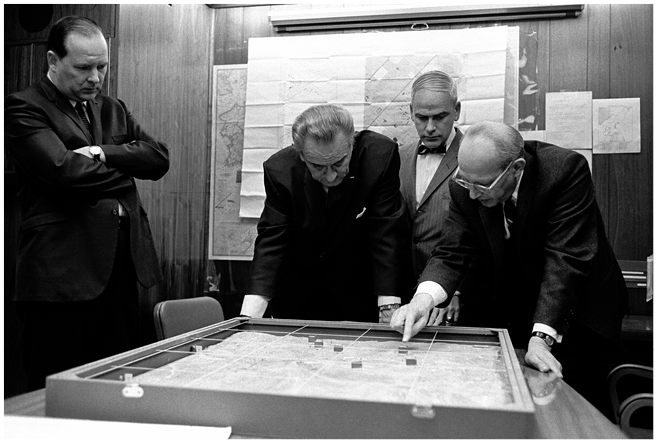

In February 1965, Johnson and his political advisors accepted that air power was an appropriate instrument with which to bully North Vietnam: it would cost fewer American lives than sending in American ground troops; they could focus it on key North Vietnamese targets; and, above all, they could control its intensity. Control was essential for Johnson. Although he had committed personal as well as national prestige to preserving a noncommunist South Vietnam, equally important was ensuring that the war in Southeast Asia did not expand into a larger conflict involving either the Chinese or the Soviets. Remembering Chinese intervention in the Korean War, Johnson was terrified that the Chinese would send troops to support their communist neighbors in North Vietnam or, worse yet, that the Soviets would actively join in the conflict – possibly even with nuclear weapons.Footnote 10 Both the president’s key advisors, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, warned Johnson not to implement the proposed intensive, three-week air campaign against North Vietnam because of the unknown impact that such bombing would have on the communist superpowers. Rusk, as assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs during the Korean War, had seen at first hand the effects of miscalculating Chinese intentions, while McNamara had played a key role in helping resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis. Johnson placed an enormous amount of trust in the opinions of both men.

Besides his fears that Vietnam might expand into World War III, Johnson’s commitment to establishing a “Great Society” caused him to shun a heavy air attack on North Vietnam. He feared that a massive increase in military force in Southeast Asia would advertise the seriousness of the threat to South Vietnam, causing the attention of Congress and the American public to shift away from the social programs that he cherished. A rapid increase in military pressure would have further repercussions. The president hoped to secure a favorable perception of the United States among Third World nations. Too much force in Vietnam might cause those countries to view the American effort as motivated by imperial ambitions or feelings of racial superiority. Exerting too much force against North Vietnam would make the United States appear as a Goliath pounding a hapless David, and likely drive small nations searching for a Cold War benefactor into the communist embrace. Johnson also wished to maintain the support of NATO and other Western allies. The greater the effort in Vietnam, the more allies elsewhere would question the ability of the United States to sustain its military commitments.

Johnson’s conflicting goals combined to produce the main principle of air strategy against North Vietnam: gradual response. American political leaders believed that military force was necessary to guarantee the South’s existence, yet other goals prevented them from unleashing the United States’ full military power. To ensure that the war remained limited, Johnson prohibited military actions that threatened, or that the Chinese or Soviets might perceive as threatening, the survival of North Vietnam. Bombing would begin slowly in the southern part of North Vietnam and incrementally “roll” northward toward the heartland containing Hanoi and Hải Phòng. Meanwhile, Johnson and his political chiefs would scrutinize bombing’s effects, with a wary eye focused on the reactions of Moscow and Beijing. Based on those reactions, as well as the response of the American public and the world community at large, they could tighten or loosen the bombing faucet as they saw fit. Rolling Thunder’s initial attack on March 2, 1965, struck only one target, an ammunition depot well south of the heartland, and was the only attack of the week. The following week fighters bombed barracks and ammunition depots, again south of the 20th parallel, on a single day.

Johnson and his political advisors hoped that the attacks would signal to Hồ Chí Minh that ultimately air power would demolish its meager industrial apparatus north of the 20th parallel. Fighters bombed more targets, on more days, during the third week of March, and the bombs crept northward toward Hanoi. During this span, Admiral Sharp stated that he expected that the limited interdiction would yield success by degrading transportation, diverting manpower to rebuilding roads and bridges, and conveying American “strength of purpose” that would “make support of the VC [Viet Cong] as onerous as possible.”Footnote 11 This faith, also shared by political leaders, that the threat of greater destruction would suffice to make the North Vietnamese balk, stemmed from the Soviet retreat during the Cuban Missile Crisis.Footnote 12 Noted National Security Council official Chester L. Cooper: “It seemed inconceivable that the lightly armed and poorly equipped Communist forces could maintain their momentum against, first, increasing amounts of American assistance to the Vietnamese Army, and subsequently, American bombing.”Footnote 13

Evaluating Rolling Thunder

The belief that Hồ would cower to air power lasted very briefly, although a slim regard for North Vietnam’s tenacity endured throughout the Johnson presidency. By early April 1965, after only six Rolling Thunder missions, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy began pressing Johnson to change the focus of American military effort to ground power. Sharp and other air chiefs redoubled their efforts to convince political leaders to bomb key elements of Northern war-making capability directly, but Bundy, Rusk, McNamara, and general-turned-ambassador to South Vietnam Maxwell Taylor persuaded Johnson to emphasize – and enlarge – the American military effort on the ground in the South. To American political leaders after July 1965, bombing the North would serve as a means of supporting American troops in South Vietnam by denying enemy forces unlimited supplies and placing a “ceiling” on the magnitude of the war that they could fight. Many air commanders, however, continued to advocate increased attacks on North Vietnamese heartland targets in the hopes that air power might ultimately wreck the North’s capability and will to fight.