According to one picture of practical reasoning, people are decision-making animals, assessing the advantages and disadvantages of proposed courses of action and choosing in accordance with that assessment. This picture plays a familiar role in economics and decision theory; in various forms, it is central to leading descriptions of reasoning in law and politics. Even in psychology, where models of bounded rationality are pervasive and where it is common to speak of “satisficing” rather than optimizing, the deviations can be understood only against the background of this picture.

This understanding of practical reasoning is quite inadequate. An important problem is that it ignores the existence of simplifying strategies that people adopt well before on-the-spot decisions must be made.Footnote 1 People might not like making decisions; doing so might create anxiety and stress, and perhaps an unwelcome sense of responsibility. People also know that they might err. They seek to overcome their own shortcomings – calculative, moral, or otherwise – by making some meta-choice before the moment of ultimate decision. Ordinary people and social institutions are often reluctant to make on-the-spot decisions.

Second-order decisions involve the strategies that people use in order to avoid getting into an ordinary decision-making situation in the first instance. There are important issues here about cognitive burdens and also about responsibility, equality, and fairness. In daily life, we might adopt a firm rule: Never lie or cheat, for example, or never drink alcohol before dinner. In law, some judges favor a second-order decision on behalf of rules, on the ground that rules promote predictability and minimize the burdens of subsequent decisions. In politics, legislatures often adopt a second-order decision in favor of a delegation to some third party, like an administrative agency. But there are many alternative strategies, and serious questions can be raised by rule-bound decisions (as opposed, for example, to small, reversible steps) and by delegations (as opposed, for example, to rebuttable presumptions).

People have diverse second-order strategies, and a main goal here is to identify them and to understand why one or another might be best. As we shall see, these strategies differ in the extent to which they produce mistakes and also in the extent to which they impose informational, moral, and other burdens on the agent and on others, either before the process of ultimate decision or during the process of ultimate decision. There are three especially interesting kinds of cases.

The first involves second-order decisions that greatly reduce the burdens of on-the-spot decisions, and that might even eliminate those burdens, but that require considerable thinking in advance. Consider a decision about how to handle a health problem – a decision that once made, requires few decisions, or even no decisions, in the future. Decisions of this kind, which we might call High-Low, may be difficult and not at all fun to make before the fact; the question is whether those burdens are worth incurring in light of the aggregate burdens – cognitive, moral, cognitive, and otherwise – of second-order and first-order decisions taken together.

The second are Low-Low. These second-order strategies impose little in the way of decisional burdens either before or during the ultimate decision. This is a great advantage. A major question is whether the strategy in question (consider a decision to flip a coin) produces too many mistakes or too much inconsistency or unfairness.

The third are Low-High. These second-order strategies involve low before-the-fact decisional burdens for the agents themselves, at the cost of imposing possibly high subsequent burdens on the agent’s future self, or on someone else to whom the first-order decision is “exported.” A delegation of power to some trusted associate, or to an authority, is the most obvious case.

An understanding of actual practices provides guidance for seeing when one or another strategy will be chosen, when one or another makes best sense, and how both rational and boundedly rational persons and institutions might go about making the relevant choices.Footnote 2 No particular strategy can be said to be better in the abstract; but it is possible to identify, in the abstract, the factors that argue in favor of one or another strategy, and also the contexts in which each approach makes sense. We shall see, for example, that a second-order decision in favor of firm rules (a form of High-Low) is appropriate when an agent faces a large number of decisions with similar features and when advance planning is especially important; in such cases, the crudeness of rules might be tolerated because of their overall advantages.

By contrast, a second-order decision in favor of small, reversible steps (a form of Low-Low) is preferable when the agent lacks reliable information and reasonably fears unanticipated bad consequences; this point helps explain the method that is often at work in both personal lives and common law courts (and argues against some of the critics of that method). A sensible agent will choose the alternative second-order strategy of delegating to another person or institution (a form of Low-High) when there is a special problem with assuming responsibility – informational, moral, or otherwise – and when an appropriate delegate, with sufficient time and expertise, turns out to be available; this point helps illuminate debates over delegations including those within families, the workplace, religious organizations, legislatures, administrative agencies, and other groups.Footnote 3 In the process it will be necessary to address a range of ethical, political, and legal issues that are raised by various second-order decisions.

Decisions and Mistakes

Strategies

The following catalogue captures the major second-order strategies. The taxonomy is intended to be exhaustive of the possibilities, but the various items should not be seen as exclusive of one another; there is some overlap between them.

Rules

People anticipating hard or repetitive decisions may do best to adopt a rule. A key feature of a rule is that it amounts to a full, or nearly full, ex ante specification of results in individual cases. People might decide, for example, that they will never park illegally, stay up after midnight, eat meat, or fail to meet a deadline. For individuals, an evident advantage of rules is that people do not have to spend time making decisions in individual cases; that might make life simpler and more pleasant. A legislature might provide that judges can never make exceptions to the speed limit law or the law banning dogs from restaurants, or that everyone who has been convicted of three felonies must be sentenced to life imprisonment.

Presumptions

Sometimes ordinary people and public institutions rely not on a rule but instead on a presumption, which can be rebutted. The result, it is hoped, is to make fewer mistakes while at the same time incurring reasonable decisional burdens.Footnote 4 People might decide, for example, that they will not park illegally unless the circumstances really require it. An administrative agency might presume that no one may emit more than X tons of a certain pollutant, but the presumption can be rebutted by showing that further reductions are not feasible.

Standards

Rules are often contrasted with standards.Footnote 5 A ban on “excessive” speed on the highway is a standard; so is a requirement that pilots of airplanes be “competent,” or that student behavior in the classroom be “reasonable.” These might be compared with rules specifying a 55-mph speed limit, or a ban on pilots who are over the age of seventy, or a requirement that students sit in assigned seats. In daily life, we might adopt a standard. We will not eat or drink “too much,” and we will not drive “too much.”

Routines

Sometimes a reasonable way to deal with a decisional burden is to adopt a routine. This term is meant to refer to something similar to a habit, but more voluntary, more self-conscious, and without the pejorative connotations of some habits (like the habit of chewing one’s fingernails). A forgetful person might adopt a routine of locking his door every time he leaves his office, even though sometimes he knows he will return in a few minutes; a commuter might adopt a particular route and follow it every day, even though on some days another route would be better; an employee might arrive at the office by a specified time every morning, even though he does not always need to be in that early.

Small steps

A possible way of simplifying a difficult situation at the time of choice is to make a small, incremental decision, and to leave other questions for another day. When a personal decision involves imponderable and apparently incommensurable elements, people often take small, reversible steps first.Footnote 6 For example, Jane may decide to live with Robert before she decides whether she wants to marry him; Marilyn may go to night school to see if she is really interested in law. A similar “small-steps” approach is the hallmark of Anglo-American common law.Footnote 7 Judges typically make narrow decisions, resolving little beyond the individual case; at least this is their preferred method of operation when they lack confidence about the larger issues, not only in the common law but in constitutional law too.Footnote 8

Picking

Sometimes the difficulty of decision, or symmetry among the options, pushes people to decide on a random basis. They might, for example, flip a coin, decide in favor of the option they see first, or make some apparently irrelevant factor decisive (“it’s a sunny day, so I’ll take that job in Florida”). Thus they might “pick” rather than “choose” (taking the latter term to mean basing a decision on preference or by reference to reasons).Footnote 9 A legal system might use a lottery to decide who serves on juries or in the military. Indeed, lotteries are used in many domains where the burdens of individualized choice are high, and when there is some particular problem with deliberation about the grounds of choice, sometimes because of apparent symmetries among the candidates. In day-to-day life, we often decide by reference to something like a lottery, even if the decision to do that happens unconsciously and rapidly.

Delegation

A familiar way of handling decisional burdens is to delegate the decision to someone else. People might rely on a spouse, a lover, an expert, or a friend, or choose an institutional arrangement by which certain decisions are made by authorities established at the time or well in advance. Such arrangements can be more or less formal; they involve diverse mechanisms of control, or entirely relinquished control, by the person or people for whose benefit they have been created.

Heuristics

People often use heuristic devices, or mental shortcuts, as a way of bypassing the need for individualized choice. For example, it can be overwhelming to figure out for whom to vote in local elections; people may therefore use the heuristic of party affiliation. When meeting someone new, your behavior may be a result of heuristic devices specifying the appropriate type of behavior with a person falling in the general category in which the new person seems to fall. A great deal of attention has been given to heuristic devices said to produce departures from “rationality.”Footnote 10 But often heuristic devices are fully rational, if understood as a way of producing pretty good outcomes, and perhaps excellent outcomes, while at the same time reducing cognitive overload or other decisional burdens.

Costs of Decisions and Costs of Errors

Under what circumstances will, or should, a person or institution make some second-order decisions rather than making an all-things-considered judgment on the spot? And under what circumstances will, or should, one or another strategy be chosen? Many people have emphasized the particular value of rules, which can overcome myopia or weakness of will;Footnote 11 but the problem is far more general, and rules are just one of many possible solutions.

Recall that second-order strategies differ in the extent to which they produce decisional burdens and mistakes. Those burdens might be emotional; it might be unpleasant to make decisions on the spot, and second-order strategies might reduce or eliminate that unpleasantness. Those burdens might be cognitive; it might take a lot of time and energy to make decisions on the spot, and second-order strategies might be a blessing. Second-order strategies should be chosen by attempting to minimize the sum of the costs of making decisions and the costs of error, where the costs of making decisions are the costs of coming to closure on some action or set of actions, and where the costs of error are assessed by examining the number, the magnitude, and the kinds of mistakes.Footnote 12

“Errors” are understood as suboptimal outcomes, whatever the criteria for deciding what is optimal; both rules and delegations can produce errors (the rule may be crude; the delegate may be incompetent). If the emotional and cognitive costs of producing optimal decisions were zero, it would be best to make individual calculations in each case, for this approach would produce correct judgments without compromising accuracy or any other important value (bracketing the possibility that advance planning might be helpful or important). This would be true for individual agents and also for institutions. It is largely because people (including public officials) seek to reduce decisional burdens, and to minimize their own errors, that sometimes they would like not to have options and sometimes not to have information; and they may make second-order decisions to reduce either options or information (or both).Footnote 13

Three additional points are necessary here. The first involves responsibility: People sometimes want to assume responsibility for certain decisions even if others would make those decisions better, and people sometimes want to relieve themselves of responsibility for certain decisions even if other people would make those decisions worse. These are familiar phenomena in daily life; you might want to be the person who decides what you will do for the next year, and you might not want to be the person who makes certain boring financial decisions. So too in business, politics, and law, where people with authority might gain a great deal from making the decisions themselves, or might gain a great deal for giving that responsibility to others. A failure of responsibility might be understood as a kind of “cost,” but it is qualitatively different from the decision costs and error costs discussed thus far, and raises separate questions. Special issues are created by institutional arrangements that divide authority, such as the separation of powers; such arrangements might forbid people from assuming or delegating certain decisions, even if they would very much like to do so.

The second point comes from the fact that multiparty situations raise distinctive problems. Above all, public institutions (including legislatures, agencies, and courts) may seek to promote planning by setting down rules and presumptions in advance. The need for planning can argue strongly against on-the-spot decisions even if they would be both correct and costless to achieve. As we will see, the need for planning can lead in the direction of a particular kind of second-order strategy, one that makes on-the-spot decisions more or less mechanical.

The third and most important point is that a reference to a “sum” of decision costs and error costs should not be taken to suggest that a straightforward cost-benefit analysis is an adequate way to understand the choice among second-order strategies. There is no simple metric along which to align the various considerations. Important qualitative differences can be found between decision costs and error costs, among the various kinds of decision costs, and also among the various kinds of error costs. For any one of us, the costs of decision may include time, money, unpopularity, sadness, stress, anxiety, boredom, agitation, anticipated ex post regret or remorse, feelings of responsibility for harm done to self or others, injury to self-perception, guilt, or shame.

Things become differently complicated for multimember institutions, where these points also apply, but where interest-group pressures may be important, and where there is the special problem of reaching a degree of consensus. A legislature might find it especially difficult to specify the appropriate approach to climate change, given the problems posed by disagreement, varying intensity of preference, and aggregation issues; for similar reasons, a multimember court may have a hard time agreeing on how to handle an asserted right to physician-assisted suicide. The result may be strategies for delegation or for deferring decision, often via small steps.

An institution facing political pressures may have a distinctive reason to adopt a particular kind of second-order decision, one that will deflect responsibility for choice. Jean Bodin defended the creation of an independent judiciary, and thus provided an initial insight into a system of separated and divided powers, on just this ground; a monarch is relieved of responsibility for unpopular but indispensable decisions if he can point to a separate institution that has been charged with the relevant duty.Footnote 14 This is an important kind of enabling constraint, characteristic of good second-order decisions.

In many nations, the existence of an independent central bank is often justified on this ground. In the United States, the president has no authority over the money supply and indeed no authority over the Chair of the Federal Reserve Board, partly on the theory that it is advantageous to separate the president from necessary but unpopular decisions (such as refusing to increase the supply of money when unemployment seems too high); presidents might be reluctant to make such decisions, the fact that the Federal Reserve Board is unelected is an advantage here. There are analogues in business, in workplaces, and even in families, where a mother or father may be given the responsibility for making certain choices, partly in order to relieve the other of responsibility. Of course, this approach can cause problems of unfairness and inequality, and it might lead to mistakes.

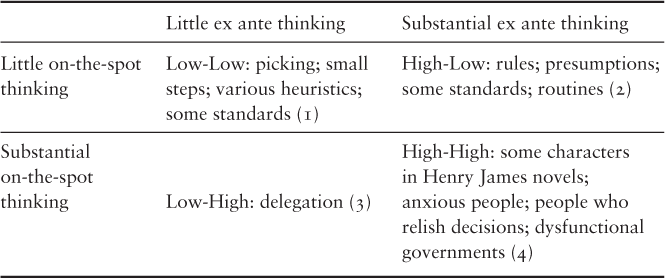

Burdens Ex Ante and Burdens on the Spot

The inquiry into second-order strategies can be organized by noticing a simple point: Some such strategies require substantial thought in advance but little thought on the spot, whereas others require little thought before the situation of choice arises and also little thought on the spot. Still others involve little ex ante thought, which leads to imposing the possibly high decisional burdens on self or others. Thus there is a temporal difference in the imposition of the burdens of decision, which can be described with the terms “High-Low,” “Low-Low,” and “Low-High.” To fill out the possibilities, we should add “High-High” as well. The term decision costs refers here to the overall costs, which may be borne by different people or agencies: The work done before the fact of choice may not be carried out by the same actors who will have to do the thinking during the ultimate choice. Consider Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Ex ante burdens and burdens on the spot

Little ex ante thinking | Substantial ex ante thinking | |

|---|---|---|

Little on-the-spot thinking | Low-Low: picking; small steps; various heuristics; some standards (1) | High-Low: rules; presumptions; some standards; routines (2) |

Substantial on-the-spot thinking | Low-High: delegation (3) | High-High: some characters in Henry James novels; anxious people; people who relish decisions; dysfunctional governments (4) |

Cell (1) captures strategies that promise to minimize the overall burdens of having to make decisions (whether or not they promote good overall decisions). These are cases in which agents do not invest a great deal of thought either before or at the time of decision. Picking is the most obvious case; consider the possibility of flipping a coin. Small steps are more demanding, since the agent does have to make some decisions, but because the steps are small, there need be comparatively little thought before or during the decision.

The most sharply contrasting set of cases is High-High, Cell (4). As this cell captures strategies that maximize overall decision costs, it ought for current purposes to remain empty, or at least nearly so. Fortunately, it seems to be represented only by a small minority of people in actual life; usually they are doing themselves no favors. Often those who fall in Cell (4) seem hopelessly indecisive, but it is possible to imagine people thinking that High-High represents a norm of moral responsibility, or that (as some people seem to think) incurring high burdens of decision is something to relish. It is also possible to urge High-High where the issue is extremely important and where there is no other way of ensuring accuracy; consider, for example, the decision whether to take a job, to leave a marriage, or to start a war, decisions that may reasonably call for a great deal of deliberation both before and during the period of choice.

Cell (2) captures a common aspiration for individuals and agents that prefer their lives to be rule-bound. Some institutions and agents spend a great deal of time choosing the appropriate rules; once the rules are in place, decisions become extremely simple, rigid, even mechanical. Everyone knows people of this sort; they can seem both noble and frustrating precisely because they follow rules to the letter. (No drinking, ever; no staying up late, ever; no fun, ever.) Legal formalism – the commitment to setting out clear rules in advance and mechanical decision afterwards, a commitment defended by US Supreme Court Justices Hugo Black and Antonin Scalia – is associated with cell (2).Footnote 15

When planning is important and when a large number of decisions must be made, cell (2) is often the best approach. For each of us, rules are a blessing – and a great simplifier of life – even if it takes time and trouble to come up with them. Or consider the twentieth-century movement away from the common law and toward bureaucracy and simple rules. Individual cases of mistake, and individual cases of error or even unfairness, may be tolerable if the overall result is to prevent the system from being overwhelmed by decisional demands. Cell (2) is also likely to be the best approach when many people are involved and it is known in advance that the people who will have to carry out on-the-spot decisions constantly change. Consider institutions with many employees and a large turnover (the army, entry levels of large corporations, and so forth). The head of an organization may not want newly recruited, less-than-well-trained people to make decisions for the firm: Rules should be in place so as to ensure continuity and uniform level of performance.

On the other hand, the possibility that life will confound the rules often produces arguments for institutional reform in the form of granting power to administrators or employees to exercise “common sense” in the face of rules.Footnote 16 An intermediate case can be found with most standards; the creation of the standard may itself require substantial thinking, but even when the standard is in place, agents may have to do some deliberating in order to reach closure.

Cell (3) suggests that institutions and individuals sometimes do little thinking in advance but may or may not minimize the aggregate costs of decision. The best case for this approach involves an agent who lacks much information or seeks for some other reason to avoid responsibility, and a delegate who promises to make good decisions relatively easily. As we have seen, delegations may require little advance thinking, at least on the substance of the issues to be decided; the burdens of decision will eventually be faced by the object of the delegation (who may be one’s future self). While some delegations are almost automatic (say, in a family), some people think long and hard about whether and to whom to delegate. Also, some people who have been delegated power will proceed by rules, presumptions, standards, small steps, picking, or even subdelegations. Note that small steps might be seen as an effort to “export” the costs of decision to one’s future self; this is important in ordinary life and related to an important theme in the common law, one that is highly valued by many judges.

It is an important social fact that many people are relieved of the burdens of decision through something other than their own explicit wishes. Consider young children and people with cognitive problems or mental health issues; in a range of cases, society or law makes a second-order decision on someone else’s behalf, often without a clear or binding indication of that person’s own desires. The displacement of another’s decisions is typically based on a belief that the relevant other will systematically err. This is of course a form of paternalism, which can arises when there is delegation without consent.

In some cases, second-order decisions produce something best described as Medium-Medium, with imaginable extensions toward Moderately High-Moderately Low, and Moderately Low-Moderately High. Consider some standards, which, it will be recalled, structure first-order decisions but require a degree of work on the spot, with the degree depending on the nature of the particular standard. But after understanding the polar cases, analysis of these intermediate cases is straightforward.

Let us now turn to the contexts in which individuals and institutions will, or should, follow one or another of the basic second-order strategies.

Low-High (With Special Reference to Delegation)

Informal and Formal Delegations

I have lunch periodically with a good friend, who happens to be a behavioral economist. For years, I have asked him, in advance, where he would like to go. I thought that was a polite thing to do. On one of those occasions, he responded, “Why don’t you decide?” Before I did, I asked him why he wanted me to be the decider. He replied, sweetly, “I never like deciding where to go for lunch. Actually I hate doing that.”

Suppose that you do not like making some set of decisions; they are really not fun to make. Or suppose that you know that you are not good at making some set of decisions; you might get it badly wrong. You might direct, or ask, someone else to decide. As a first approximation, a delegation is a second-order strategy that exports decision-making burdens to someone else, in an effort to reduce the agent’s burdens both before and at the time of making the ultimate decision. A typical case involves an agent who does not enjoy making the relevant decisions, who does not trust her own capacity to decide wisely, or who seeks to avoid responsibility (for some strategic or ethical reason, or because of a simple lack of information) – and who identifies an available delegate whom she trusts to make a good, right, or expert decision.

Informal delegations occur all the time. One spouse may delegate to another the decision about what the family will eat for dinner, what investments to choose, or what car to buy. Such delegations often occur because the burdens of decision are high for the agent but low for the delegate, who may have specialized information, who may lack relevant biases or motivational problems, or who may not mind (and who may even enjoy) taking responsibility for the decision in question. (These cases may then be more accurately captured as special cases of Low-Low.) The intrinsic burdens of having to make the decision are often counterbalanced by the benefits of having been asked to assume responsibility for it (though these may be costs rather than benefits in some cases). Some delegates are glad or even delighted to assume their role; this is relevant to some ethical issues involving delegation (consider the question of justice within the family; if a husband delegates too many decisions to his wife, we might have an issue of justice). And there is an uneasy line, raising knotty conceptual and empirical questions, between a delegation and a division of labor (consider the allocation of household duties). A key issue here is whether the recipient of the delegation has the authority to decline, or is essentially forced to say “yes!” or at least “okay!”

In business, delegations often occur for parallel reasons. One person in a company might delegate to another, with the delegator believing that she is busy with other matters or that she lacks relevant expertise. Someone within the company might have plenty of time to figure things out, or might be a specialist in the matter at hand. When I worked in the White House under President Barack Obama, I was part of a small team of officials working on financial regulatory reform under the leadership of Larry Summers, who was head of the National Economic Council. Summers would sometimes disagree with his team, and after a brief argument, he would occasionally say, “All right you geniuses, you figure it out.”

Government itself is a large recipient of delegated decisions, at least if sovereignty is understood to lie in the citizenry. On this view, various public institutions – legislatures, courts, the executive branch – exercise explicitly or implicitly delegated authority, and there are numerous subdelegations, especially for the legislature, which must relieve itself of many decisional burdens. A legislature may delegate because it believes that it lacks information about, for example, environmental problems or changes in the telecommunications market; the result is an Environmental Protection Agency or a Federal Communications Commission. Or the legislature may have the information but find itself unable to forge a consensus on underlying values about, for example, the right approach to climate change, nuclear power, or age discrimination.

Often a legislature lacks the time and the organization to make the daily decisions that administrative agencies are asked to handle; consider the fact that legislatures that attempt to reconsider agency decisions often find themselves involved in weeks or even months of work, and fail to reach closure. Or the legislature may be aware that its vulnerability to interest-group pressures will lead it in bad directions, and it may hope and believe that the object of the delegation will be relatively immune. Interest-group pressures may themselves produce a delegation, as where powerful groups are unable to achieve a clear victory in a legislature but are able to obtain a grant of authority to an administrative agency over which they will have power. The legislature may even want to avoid responsibility for some hard choice, fearing that decisions will produce electoral reprisal. Self-interested representatives may well find it in their electoral self-interest to enact a vague or vacant standard (“the public interest,” “reasonable accommodation” of the disabled, “reasonable regulation” of pesticides), and to delegate the task of specification to someone else, secure in the knowledge that the delegate will be blamed for problems in implementation. There are close parallels in companies and in daily life.

When to Delegate

Delegation deserves to be considered whenever an appropriate and trustworthy delegate is available and there is some sense in which it seems undesirable for the agent to be making the decision by himself. But obviously delegation can be a mistake – an abdication of responsibility; a source of unfairness; a recipe for more rather than fewer errors, and so for even higher (aggregate) costs of decision. And since delegation is only one of a number of second-order strategies, an agent might want to consider other possibilities before delegating.

Compared to a High-Low approach, a delegation will be desirable if the delegator does not want to face the burdens of decision or is unable to generate a workable rule or presumption (and if anything it could come up with would be costly to produce), and if a delegate would do well enough or better on the merits. This may be the case for an individual who just does not know how to make a decision (about, say, where to eat lunch, how to handle a difficult medical problem, or how to make investments). It may also be the case on a multimember body that is unable to reach agreement, or when an agent or institution faces a cognitive or motivational problem, such as weakness of will or susceptibility to outside influences. A delegation will also be favored over High-Low if the delegator seeks to avoid responsibility for the decision for political, social, or other reasons, though the effort to avoid responsibility may also create problems of legitimacy, as when a legislator relies on “experts” to make value judgments about environmental protection or disability discrimination.

As compared with small steps or picking, a delegation may or may not produce higher total decision costs (perhaps the delegate is slow or a procrastinator). Even if the delegation does produce higher total decision costs, it may also lead to more confidence in the eventual decisions, at least if reliable delegates are available. In private life, you might choose to rely on a financial advisor or a doctor, simply because you will trust the eventual decision. In the United States, the Federal Reserve Board has often had a high degree of public respect, which means that there is little pressure to eliminate or reduce the delegation. But a delegate – a friend, an expert, a spouse, the Environmental Protection Agency – may prove likely to err, and a rule, a presumption, or small steps may emerge instead. Special issues are raised in technical areas, which create strong arguments for delegation, but where the delegate’s judgments may be hard to oversee (even if they conceal controversial judgments of value) return to the Environmental Protection Agency, which might be relied upon because of his expertise, but might be troublesome if it is seen as a free agent. Here again there are parallels in ordinary life, in which we might be tempted to rely on experts but are worried about their motivations and the risks that might arise if they are independent.

There is also the concern for fairness. In some circumstances, it is unfair to delegate to a friend or a spouse the power of decision, especially but not only because the delegate is not a specialist. People might hate the delegation; it might be a burden or a curse. Issues of gender equality arise when a husband delegates to his wife all decisions involving the household and the children, even if both husband and wife agree on the delegation. Apart from this issue, a delegation by one spouse to another may well seem inequitable if (say) it involves a child’s problems with alcohol, because it is an abdication of responsibility, a way of transferring the burdens of decision to someone else who should not be forced to bear them alone.

In institutional settings, there is an analogous problem if the delegate (usually an administrative agency) lacks political accountability even if it has relevant expertise. The result is the continuing debate over the legitimacy of delegations to administrative agencies. Such delegations can be troublesome if they shift the burden of judgment from a democratically elected body to one that is insulated from political control. A legislature has plenty of alternatives to delegation. If it wants to avoid the degree of specificity entailed by rule-bound law, it might instead enact a presumption or take small steps (as, e.g., through an experimental pilot program). Related issues are raised by the possibly illegitimate abdication of authority when a judge delegates certain powers to law clerks (as is occasionally alleged about Supreme Court justices) or to special masters who are experts in complex questions of fact and law.

Three Complications

Three complications deserve comment. First, any delegate may itself resort to making second-order decisions, and it is familiar to find delegates undertaking each of the strategies described here. Sometimes delegates prefer High-Low and hence generate rules; this is the typical strategy of the tax authorities. Alternatively, delegates may use standards or proceed by small steps. Having been delegated certain decisions by a patient, a doctor might proceed incrementally, and refuse to do anything large or dramatic. In the United States, this has been the general approach of the National Labor Relations Board, which (strikingly) has tended to avoid rules, and prefers to proceed case-by-case. Or a delegate may undertake a subdelegation; confronted with a delegation from her husband, a wife may consult a sibling or a parent. Asked by Congress to make hard choices, the president may and frequently does subdelegate to some kind of commission, for some of the same reasons that spurred Congress to delegate in the first instance. Of course, a delegate may just pick.

The second complication is that the control of a delegate presents a potentially serious principal-agent problem. How can the person who has made the delegation ensure that the delegate will not make serious and numerous mistakes, or instead fritter away its time trying to decide how to decide? There are multiple possible mechanisms of control. Instead of giving final and irreversible powers of choice to the delegate, a person or institution might turn the delegate into a mere consultant or advice-giver. A wide range of intermediate relationships is possible. In the governmental setting, a legislature can influence the ultimate decision by voicing its concerns publicly if an administrative agency is heading in the wrong direction, and the legislature has the power to overturn an administrative agency if it can muster the will to do so.

Ultimately the delegator will usually retain the power to eliminate the delegation. To ensure against (what the delegator would consider to be) mistakes, it may be sufficient for the delegate to know this fact. In informal relations, involving friends, colleagues, and family members, there are various mechanisms for controlling any delegate. Some “delegates” know that they are only consultants; others know that they have the effective power of decision. All this happens through a range of cues, which may be subtle.

The third complication stems from the fact that at the outset, the burdens of a second-order decision of this kind may not be so low after all, since the person or institution must take the time to decide whether to delegate at all and if so, to whom to delegate. Complex issues may arise about the composition of any institution receiving the delegation; these burdens may be quite high and perhaps decisive against delegation altogether. A multimember institution often divides sharply on whether to delegate, and even after that decision is made, it may have trouble deciding on the recipient of the delegated authority.

Intrapersonal Delegations and Delegation to Chance

The focus thus far has been on cases in which the delegator exports the burdens of decision to some other person or party. What about the intrapersonal case? Can current John delegate decisions to future John?

On the one hand, there is no precise analogy between that problem and the cases under discussion. On the other hand, people confronted with hard choices can often be understood to have chosen to delegate the power of choice to their future selves. Consider, for example, such decisions as whether to buy a house, to have another child, to get married or divorced, or to move to a new city. In such cases, agents who procrastinate may understand themselves to have delegated the decision to their future selves.

There are two possible reasons for this kind of intrapersonal delegation, involving timing and content respectively. You may believe you know what the right decision is, but also believe it is not the right time to be making that decision, or at least not the right time to announce it publicly. It might not be the right time because you are in no mood to make it; making the decision would make you miserable. It might not be the right time because you may not know what the right decision is and believe that your future self will be in a better position to decide. You may think that your future self will have more information, enjoy making the decision more or hate making the decision less, suffer less or not at all from cognitive difficulties, bias, or motivational problems, or be in a better position to assume the relevant responsibility. Perhaps you are feeling under pressure, suffering from illness, or not sure of your judgment just yet. In such cases, the question of intrapersonal, intertemporal choice is not so far from the problem of delegation to others. It is even possible to see some overlapping principal-agent problems with similar mechanisms of control, as people impose certain constraints on their future selves. There are close parallels for judges and legislators, who care a great deal about both timing and content, and who may wait for one or another reason.

From the standpoint of the agent, then, the strategy of small steps, like that of delay, can be seen as a form of delegation. Also, the strategy of delegation itself may turn into that of picking when the delegate is a chance device. When I make my future decision depend on which card I draw from my deck of cards, I have delegated my decision to the random card-drawing mechanism, thereby effectively turning my decision from choosing to picking.

High-Low (With Special Reference to Rules and Presumptions)

We have seen that people often make second-order decisions that are themselves costly, simply in order to reduce the burdens of later decisions in particular cases. This is the most conventional kind of precommitment strategy. The most promising setting for rule-bound precommitment involves a large number of similar decisions and a need for advance planning (as opposed to improvisation). In such a setting, the occasional errors inevitably produced by rules are likely to be worth incurring. When this process is working well, there is much to do before the second-order decision has been made, but once the decision is in place, things are greatly simplified.Footnote 17

Diverse Rules, Diverse Presumptions

We have seen that rules and presumptions belong to the High-Low category, and frequently this is true. But the point must be qualified; some rules and presumptions do not involve high burdens of decision before the fact. For example, a rule might be picked rather than chosen – drive on the right-hand side of the road, or spoons to the right, forks to the left. Especially when what it is important is to allow all actors to coordinate on a single course of conduct, there need be little investment in decisions about the content of the relevant rule. A rule might even be framed narrowly, so as to work as a kind of small step. Rules can embody small steps. The same points can be made about presumptions, which are sometimes picked rather than chosen and which might be quite narrow.

Let us focus on situations in which an institution or an agent is willing to deliberate a good deal to generate a rule or a presumption that, once in place, turns out greatly to simplify (without impairing and perhaps even improving) future decisions. This is a familiar aspiration in life, law, and politics. A family might adopt a presumption: We will take a vacation where we did last year, unless there is special reason to try something new. A legislature might decide in favor of a speed limit law, partly in order to ensure coordination among drivers, and partly as a result of a process of balancing various considerations about risks and benefits. People are especially willing to expend a great deal of effort to generate rules in two circumstances: (1) when planning and fair notice are important and (2) when a large number of decisions will be made.Footnote 18

People do that consciously or unconsciously in daily life; habits are rules or presumptions. The conscious creation of habits, and the conscious or unconscious adherence to habits, make life a lot easier. In most well-functioning legal systems, it is clear what is and what is not a crime. People need to know when they may be subject to criminal punishment for what they do. In theory if not in practice, the American Constitution is taken to require a degree of clarity in the criminal law, and all would-be tyrants know that rules may be irritating constraints on their authority. So too, the law of contract and property is mostly defined by clear rules, simply because people could not otherwise plan, and in order for economic development to be possible they need to be in a position to do so.

When large numbers of decisions have to be made, there is a similar tendency to spend a great deal of time to clarify outcomes in advance. Doctors adopt a host of rules for treating cancer and heart disease. In the United States, the need to make a large number of decisions has pushed the legal system into the development of rules governing social security disability, workers’ compensation, and criminal sentencing. The fact that these rules may produce a significant degree of error is not decisive; the sheer cost of administering the relevant systems, with so massive a number of decisions, makes a certain number of errors tolerable.

Compared to rules, standards and “soft” presumptions serve to reduce the burdens of decision ex ante while increasing those burdens at the time of decision. This is both their virtue and their vice. In daily life, we might adopt standards and rebuttable presumptions for food and liquor consumption, or to help manage expenditures. Or consider the familiar strategy of enacting rigid, rule-like environmental regulations while at the same time allowing a “waiver” for special circumstances. The virtue of this approach is that the rigid rules will likely produce serious mistakes – high costs, low environmental benefits – in some cases; the waiver provision allows correction in the form of an individualized assessment of whether the statutory presumption should be rebutted. The potential vice of this approach is that it requires a fair degree of complexity in a number of individual cases. Whether the complexity is worthwhile turns on a comparative inquiry with genuine rules. How much error would be produced by the likely candidates? How expensive is it to correct those errors by turning the rules into presumptions?

Of Institutions, Planning, and Trust

Often institutions are faced with the decision whether to adopt a High-Low strategy or to delegate. We have seen contexts in which a delegation is better. But in three kinds of circumstances, the High-Low approach is to be preferred.

First, when planning is important, it is important to set out rules (or presumptions) in advance. The law of property is an example. Second, there is little reason to delegate when the agent or institution has a high degree of confidence that a rule (or presumption) can be generated at low enough cost, that the rule (or presumption) will be accurate, and that it will actually be followed. Third, and most obviously, High-Low is better when no trustworthy delegate is available, or when it seems unfair to ask another person or institution to make the relevant decision. If you do not trust anyone with whom you work, you might make relevant decisions yourself. And if you like making decisions, you might do the same thing.

Many nations take considerations of this kind as special reasons to justify rules in the context of criminal law. The law defining crimes is reasonably rule-like, partly because of the importance of citizen knowledge about what counts as a crime, partly because of a judgment that police officers and courts cannot be trusted to define the content of the law. Legislatures tend in the direction of rule-like judgment when they have little confidence in the executive; in the United States, important parts of the Clean Air Act are a prime example of a self-conscious choice of High-Low over delegation.

When would High-Low be favored over Low-Low (picking, small steps)? The interest in planning is highly relevant here and often pushes in the direction of substantial thinking in advance. If an individual or institution has faith in its ability to generate a good rule or presumption, it does not make much sense to proceed with a random choice or incrementally. Families adopt a host of rules, and so do investors. Legislatures have often displaced the common law approach of case-by-case judgment with clear rules set out in advance. In England and the United States, this was a great movement of the twentieth century, largely because of the interest in planning and decreased faith in the courts’ ability to generate good outcomes through small steps. Mixed strategies are possible. An institution may produce a rule to cover certain cases but delegate decisions in other cases; a delegate may be disciplined by presumptions and standards; an area of law, or practical reason, may be covered by some combination of rule-bound judgment and small steps.

Private Decisions

We have said enough to show that in their individual capacity, people frequently adopt rules, presumptions, or self-conscious routines in order to guide decisions that they know might, in individual cases, be too costly to make or might be made incorrectly because of their own lack of information or motivational problems (including problems of self-control). Sarah might decide that she will turn down all invitations for out-of-town travel in the months of September or October, or John might adopt a presumption against going to any weddings or funerals unless they involve close family members, or Fred might make up his mind that at dinner parties, he will drink whatever the host is drinking. Rules, presumptions, and routines of this kind are an omnipresent feature of practical reason; sometimes they are chosen self-consciously and as an exercise of will, and often they are, or become, so familiar and simple that they appear to the agent not to be choices at all. Problems arise when a person finds that he cannot stick to his resolution, and thus High-Low may turn into High-High, and things may be as if the second-order decision had not been made at all.

Some especially important cases involve efforts to solve the kinds of intertemporal, intrapersonal problems that arise when isolated, small-step, first-order decisions are individually rational but produce harm to the individual when taken in the aggregate. These cases might be described as involving “intrapersonal collective action problems.”Footnote 19 Consider, for example, the decision to smoke a cigarette (right now), or to have fudge brownies for dessert, or to have an alcoholic drink after dinner, or to gamble on weekends. Small steps, which may be rational choices when taken individually and which may produce net benefits when taken on their own, can lead to harm or even disaster when they accumulate. There is much room here for second-order decisions. As a self-control strategy, a person might adopt a rule: cigarettes only after dinner; no gambling, ever; fudge brownies only on holidays; alcohol only at parties when everyone else is drinking. But a presumption might work better – for example, a presumption against fudge brownies, with the possibility of rebuttal on special occasions, when celebration is in the air and the brownies look particularly amazing.

Well-known private agencies designed to help people with self-control problems (Alcoholics’ Anonymous, Gamblers’ Anonymous) have as their business the development of second-order strategies of this general kind. The most striking cases involve recovering addicts, but people who are not addicts, and who are not recovering from anything, often make similar second-order decisions. When self-control is particularly difficult to achieve, an agent may seek to delegate instead. Whether a delegation (Low-High) is preferable to a rule or presumption (High-Low) will depend in turn on the various considerations discussed earlier.

Low-Low (With Special Reference to Picking and Small Steps)

Equipoise, Responsibility, and Commitment

Why might an individual or institution pick rather than choose? When would small steps be best?

Suppose that you are at a restaurant, and there are thirty items on the menu, and you think you would like six of them. Should you focus on which of the six you would like most? Should you think about them at length and in detail? Should you interrogate the waiter? Maybe so, if you are the sort of person you likes that sort of thing. Maybe you greatly enjoy pondering what dinner choice would be best; maybe that improves your experience. But maybe you are at the restaurant to enjoy a night out with your partner or friend, and maybe you do not much care whether the meal is exceptional, very good, or good enough. If so, you will pick.

At the individual level, it can be obvious that when you do not enjoy choosing or when you are in equipoise, you might as well pick. It simply is not worthwhile to go through the process of choosing, with its high cognitive or emotional costs. As we have seen, the result can be picking in both low-stakes (cereal choices) and high-stakes (employment opportunities) settings. Picking can even be said to operate as a kind of delegation, where the object of the delegation is “fate,” and the agent loses the sense of responsibility that might accompany an all-things-considered judgment. Thus some people sort out hard questions by resorting to a chance device (like flipping a coin).

Small steps, unlike a random process, are a form of choosing. Students in high schools tend to date in this spirit, at least most of the time; often adults do too. Newspapers and magazines offer trial subscriptions; the same is true for book clubs. Often advertisers (or for that matter prospective romantic partners) know that people prefer small steps, and they take advantage of that preference (no commitments).

In the first years of university, students are often told that they need not commit themselves to any particular course of study. They can take small steps in various directions, sampling as they choose. Typical situations for small steps thus involve a serious risk of unintended bad consequences because a large decision looms when people lack sufficient information; hence reversibility is especially important.

On the institutional side, consider lotteries for jury service. The appeal of a lottery for jury service stems from the relatively low costs of operating the system and the belief that any alternative device for allocation would produce more mistakes, because it would depend on a socially contentious judgment about who should be serving on juries, with possibly destructive results for the jury system itself. The key point is that the jury is supposed to be a cross-section of the community. A random process seems to be the best way of serving that goal (as well as the fairest way of apportioning what many people regard as a social burden). In light of the purposes of the jury system, alternative allocation methods might be thought to be worse; consider stated willingness to serve, an individualized inquiry into grounds for excuse, or financial payments (either to serve or not to serve).Footnote 20

Change, Unintended Consequences, and Reversibility

Lotteries involve random processes; small steps do not. People often take small steps to minimize the burdens of decisions and the costs of error. Anglo-American judges often proceed case by case for the same reasons. Many legal cultures embed a kind of norm in favor of incremental movement. They do this partly because of the distinctive structure of adjudication and the limited information available to the judge: In any particular case, a judge will hear from the parties immediately affected, but little from others whose interests might be at stake. Hence, there is a second-order decision in favor of small steps.

Suppose, for example, that a court in a case involving the scope of freedom of speech by high-school students online finds that it has little information; if the court attempted to generate a rule that would cover all imaginable situations in which that freedom might be exercised, the case would take a very long time to decide. Perhaps the burdens of decision would be prohibitive. This might be so because of a sheer lack of information, or it might be because of the pressures imposed on a multimember court consisting of people who are unsure or in disagreement about a range of subjects. Such a court may have a great deal of difficulty in reaching closure on broad rules. Small steps are a natural result.

When judges proceed by small steps, they do so precisely because they know that their rulings create precedents; they want to narrow the scope of future applications of their rulings given the various problems described earlier, most importantly the lack of sufficient information about future problems. A distinctive problem involves the possibility of too much information. A particular case may have a surplus of apparently relevant details, and perhaps future cases will lack one or more of the relevant features, and this will be the source of the concern with creating wide precedents. The existence of (inter alia) features X or Y in case A, missing in case B, makes it hazardous to generate a rule in case A that would govern case B.

In ordinary life, small steps can also make special sense if circumstances are changing rapidly. Perhaps relevant facts and values will change in such a way as to make a rule quickly anachronistic even if it is well suited to present conditions. We can draw some lessons here from law. For example, any decision involving the application of the right of freedom of speech in the context of new communications technologies, including the Internet, might well be narrow, because a broad decision, rendered too early, would be so likely to go wrong. On this view, a small step is best because of the likelihood that a broad rule would be mistaken when applied to cases not before the court.

In an argument very much in this spirit, Joseph Raz has connected a kind of small step – the form usually produced by analogical reasoning – to the special problems created by one-shot interventions in complex systems.Footnote 21 In Raz’s view, courts reason by analogy in order to prevent unintended side-effects from large disruptions. Similarly supportive of the small-step strategy, the German psychologist Dietrich Dorner has done some illuminating computer experiments designed to see whether people can engage in successful social engineering.Footnote 22 Participants are asked to solve problems faced by the inhabitants of some region of the world. Through the magic of the computer, many policy initiatives are available to solve the relevant problems (improved care of cattle, childhood immunization, drilling more wells). But most of the participants produce eventual calamities, because they do not see the complex, system-wide effects of particular interventions.

Only the rare participant is able to see a number of steps down the road – to understand the multiple effects of one-shot interventions on the system. The successful participants are alert to this risk and take small, reversible steps, allowing planning to occur over time. Hence Dorner, along with others focusing on the problems created by interventions into systems,Footnote 23 argues in favor of small steps. Many of us face similar problems, and incremental decisions are a good way of responding to the particular problem created by ignorance of possible adverse effects.

From these points we can see that small steps may be better than rules or delegation. Often an individual or institution lacks the information to generate a clear path for the future; often no appropriate delegate has that information. If circumstances are changing rapidly, any rule or presumption might be confounded by subsequent developments. What is especially important is that movement in any particular direction should be reversible if problems arise. On the other hand, a small-steps approach embodies a kind of big (if temporary) decision in favor of the status quo; in the legal context, a court that tries to handle a problem of discrimination incrementally may allow unjust practices to continue, and so too with a state that is trying to alleviate the problem of joblessness in poor areas. A small-steps approach might also undermine planning and fail to provide advance notice of the content of law or policy. It cannot be said that a small-steps approach is, in the abstract, the right approach to limited information or bounded rationality;Footnote 24 whether it is a (fully optimal) response or a (suboptimal) reflection of bounded rationality depends on the context.

The analysis is similar outside of the governmental setting. Agents might take small steps because they lack the information that would enable them to generate a rule or presumption, or because the decision they face is unique and not likely to be repeated, so that there is no reason for a rule or a presumption. Or small steps may follow from the likelihood of change over time, from the fact that a large decision might have unintended consequences, or from the wish to avoid or at least to defer the responsibility for large-scale change.

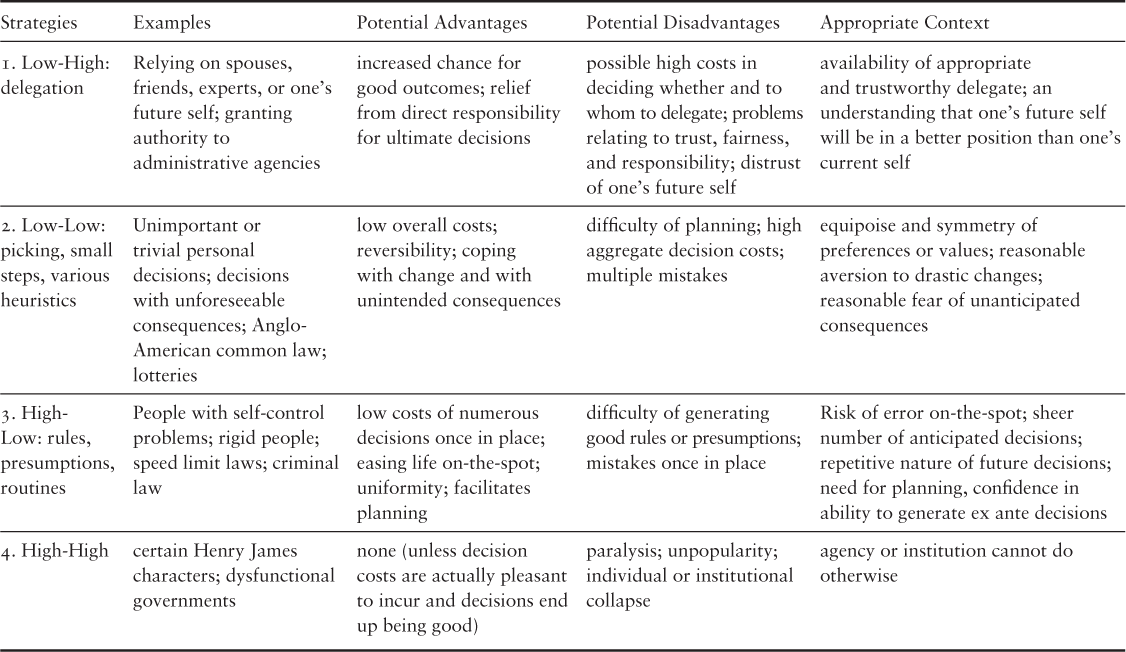

Second-Order Strategies

The discussion is summarized in Table 1.2. Recall that the terms “low” and “high” refer to the overall costs of the decision, which are not necessarily borne by the same agent: With Low-High the costs are split between delegator and delegate; with High-Low they may be split between an institution (which makes the rules, say) and an agent (who follows the rules).

Table 1.2 Second-order strategies

Strategies | Examples | Potential Advantages | Potential Disadvantages | Appropriate Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Low-High: delegation | Relying on spouses, friends, experts, or one’s future self; granting authority to administrative agencies | increased chance for good outcomes; relief from direct responsibility for ultimate decisions | possible high costs in deciding whether and to whom to delegate; problems relating to trust, fairness, and responsibility; distrust of one’s future self | availability of appropriate and trustworthy delegate; an understanding that one’s future self will be in a better position than one’s current self |

2. Low-Low: picking, small steps, various heuristics | Unimportant or trivial personal decisions; decisions with unforeseeable consequences; Anglo-American common law; lotteries | low overall costs; reversibility; coping with change and with unintended consequences | difficulty of planning; high aggregate decision costs; multiple mistakes | equipoise and symmetry of preferences or values; reasonable aversion to drastic changes; reasonable fear of unanticipated consequences |

3. High-Low: rules, presumptions, routines | People with self-control problems; rigid people; speed limit laws; criminal law | low costs of numerous decisions once in place; easing life on-the-spot; uniformity; facilitates planning | difficulty of generating good rules or presumptions; mistakes once in place | Risk of error on-the-spot; sheer number of anticipated decisions; repetitive nature of future decisions; need for planning, confidence in ability to generate ex ante decisions |

4. High-High | certain Henry James characters; dysfunctional governments | none (unless decision costs are actually pleasant to incur and decisions end up being good) | paralysis; unpopularity; individual or institutional collapse | agency or institution cannot do otherwise |

There are two principal conclusions. The first is that no second-order strategy can reasonably be preferred in the abstract. The second is that it is possible to identify the settings in which one or another is likely to make sense, and also the factors that argue in favor of, or against, any particular approach.

Making Second-Order Decisions

When do people, or institutions, actually make a self-conscious decision about which second-order strategy to favor, given the menu of possibilities? The simplest answer is: often. An employer might adopt a host of firm rules to simplify life for its employees. A family may choose, self-consciously, to proceed incrementally in terms of living arrangements (lease, don’t buy); a legislature may deliberate and decide to delegate rather than to generate rules; having rejected the alternatives, a president may recommend a lottery system rather than other alternatives for admitting certain aliens to the country. An institution or a person will often make an all-things-considered decision in favor of one or another second-order strategy.

Sometimes, however, a rapid assessment of the situation takes place, rather than a full or deliberative weighing of alternative courses of action. This is often the case in private decisions, where judgments often seem immediate. Indeed, some second-order decisions might be too costly if they were a product of an optimizing strategy; so taken, they would present many of the problems of first-order decisions. As in the case of first-order decisions, it may make sense to proceed with what seems best, rather than to maximize in any systematic fashion, simply because the former way of proceeding is easier (and thus may maximize once we consider decision costs of various kinds). For both individuals and institutions, the salient features of the context often strongly suggest a particular kind of second-order strategy; there is no reason to think long and hard about the second-order decision.

These are intended as descriptive points about the operation of practical reason. But there is a normative issue here as well, for people’s second-order decisions may go wrong. People tend to make mistakes when they choose strategies on the fly, and often they would do better to be self-conscious and reflective about the diverse possibilities. Pathologically rigid rules can be a serious problem for life, law, and policy. Sometimes delegation is a most unfortunate route to travel. At the political level, and occasionally at the individual level too, it would be much better to be more explicit and self-conscious about the various alternatives, so as to ensure that societies and institutions do not find themselves making bad second-order decisions, or choosing a second-order strategy without a sense of the candidates.

Rationality and Bounded Rationality

As we have seen, second-order strategies may solve the problems posed by unanticipated side-effects and the difficulty of obtaining knowledge about the future. They might be a response to anxiety or stress, or a recognition of the sheer unpleasantness of making certain kinds of decisions. Or they may respond to people’s awareness that they are prone to err when a decision must be made on the spot. People might try, for example, to counteract their own tendencies toward impulsiveness, myopia, and unrealistic optimism. In these ways, second-order decisions can be seen as rational strategies by people making those decisions with full awareness of the costs of obtaining information and of their own propensities for error.

But a lack of information or bounded rationality can affect second-order decisions as well. A lack of information may press people and institutions in the direction of suboptimal second-order strategies. For example, an individual or an institution may choose small steps even though rules would be much better. The availability heuristic – by which people make probability judgments by asking if relevant events are cognitively “available” and hence come readily to mind – helps account for some erroneous judgments about appropriate second-order strategies. An impulsive or myopic person or institution may fail to see the extent to which rules will be confounded by subsequent developments; an unrealistically optimistic agent or institution may overestimate its capacity to take optimal small steps. People may choose second-order strategies that badly disserve their own goals.

Burdens and Benefits

Return to the major themes. Ordinary people and official institutions are often reluctant to make on-the-spot decisions; they respond with one or another second-order strategy. Some such strategies involve high initial burdens but make life much easier for the future. These strategies, generally taking the form of rules or presumptions, are best when the anticipated decisions are numerous and repetitive and when advance notice and planning are important. They might also be best when people face serious self-control problems. Other strategies involve both light initial burdens and light burdens at the time of making the ultimate decision. These approaches work well in diverse situations: when the stakes are low; when a first-order decision is simply too difficult to make (because of the cognitive or emotional burdens involved in the choice); when the first-order decision includes too many imponderables and a risk of large unintended consequences; and when a degree of randomization is appealing on normative grounds (perhaps because choices are otherwise in equipoise, or because no one should or will take responsibility for deliberate decision). A key point in favor of small steps involves reversibility.

Still other strategies involve low initial burdens but high exported burdens at the time of decision, as when a delegation is made to another person or institution, or to one’s future self. Delegations take many different forms, with more or less control retained by the person or institution making the delegation. Strategies of delegation make sense when a delegate is available who has relevant expertise (perhaps because he is a specialist) or is otherwise trustworthy (perhaps because he does not suffer from bias or some other motivational problem), or when there are special political, strategic, or other advantages to placing the responsibility for decision on some other person or institution. Delegations can raise serious ethical or political issues and create problems of unfairness, as when delegates are burdened with tasks that they do not voluntarily assume, or would not assume under just conditions.

The final set of cases involves high burdens both before and at the time of decision, as in certain characters in novels and films, some people who are really struggling in life (and who may be crippled by anxiety), and highly dysfunctional governments. This strategy is usually a terrible idea. It can be considered reasonable only on the assumption that bearing high overall burdens of decision is something to relish (perhaps because it is actually pleasant) or an affirmative good (perhaps for moral reasons). This assumption is usually unrealistic. But it is not hard to identify situation in which people do incur high burdens well before they make decisions, and also at the time that they make decisions–behavior that often provides the motivation to consider the other, more promising second-order decisions discussed here.