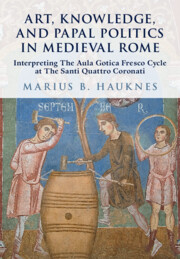

At their completion, at some time between 1244 and 1254, Cardinal Conti’s fresco decorations extended across every available wall in Santi Quattro Coronati’s great hall, from the floor level to the tops of the ribbed vaults, and even across the jambs of the doors and windows (Figure 1.1).1 At present, less than half of the original wall paintings remain intact. Preserved are portions of the south bay vault and the upper halves of all six walls; however, the paintings that covered the north bay vault and the lower halves of the walls are lost. In light of such lacunae, it is remarkable that the paintings which do remain offer a relatively clear sense of the mural program’s thematic focus as a whole. A quick scan of the preserved frescoes reveals a unified system of knowledge organized into distinct subunits. In the south bay, the months of the year and the personified seasons represent knowledge of time, the stars and planets painted on the vault represent cosmological knowledge, and images of the liberal arts in the lunettes represent knowledge of the ancients as preserved and disseminated through institutionalized education (Figures 1.2–1.4). In the north bay, the cycle of virtues and vices represents moral, historical, and theological knowledge, while the images of Roman antiquities represent the city’s material heritage and the idea of Rome as a site of Christian triumph over paganism (Figures 1.5–1.7). This program of images constitutes a “pictorial encyclopedia” in the sense that its combined treatment of temporal, cosmological, historical, moral, and educational themes approximates the diversity of subject matter and organizational logic found in textual encyclopedias of the medieval period. While comparable iconographic programs were executed in sculpture for the façades of French cathedrals in the twelfth century, Conti’s great hall is one of the earliest fresco programs to feature encyclopedic knowledge.

1.2. Frescoes on west wall of south bay showing labors of the months (January–April) in lower register, liberal arts (Geometry and Grammar) in lunette, and personifications of the seasons (Spring and Winter) in spandrels, ca. 1244–54, Santi Quattro Coronati, Rome.

1.3. Frescoes on south wall of south bay showing labors of the months (May–August) in lower register, liberal arts (Arithmetic and Music) in lunette, and personifications of the seasons (Summer and Spring) in spandrels, ca. 1244–54, Santi Quattro Coronati, Rome.

1.4. Frescoes on east wall of south bay showing calendar cycle (September–December) in lower register, liberal arts (Astronomy) in lunette, and personifications of the seasons (Summer and Autumn) in spandrels, ca. 1244–54, Santi Quattro Coronati, Rome.

The broader cultural phenomenon of medieval encyclopedism is one of several pertinent backdrops against which the Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes should be analyzed. This chapter aims to outline this and other contextual and methodological parameters that will aid our understanding of the monument. In what follows, we will see that the encyclopedism of Conti’s fresco cycle resided not only in its choice of iconographic motifs but also in its treatment of architectural space. The effect of visual and spatial enclosure resulting from the coming together of architectural space and painting in the fresco medium strongly enhanced the monument’s capacity to convey the notion of encyclopedic knowledge to its spectators. We will also see how the retelling of sacred history through the great hall’s cycle of the virtues invites us to examine the frescoes in light of the thirteenth century’s political turbulence, and how the prominent depiction of King Solomon at the center of the north wall encourages reflection on the relationship between Conti’s frescoes and the political motivations underlying the cultivation of worldly knowledge by the papacy. Before addressing these historical contexts, however, we must examine the art historical relationships between the Quattro Coronati frescoes and other thematically similar monuments produced in Rome and the papal state during the period. The most relevant of these are the closely related, yet notoriously obscure, frescoes in the crypt of Anagni Cathedral; it is only fitting that this is where we begin.

The Anagni Crypt

In the history of medieval Italian art, the Anagni crypt has been treated as something of an outlier. Its anomalous status can be ascribed to several factors. Few hall crypts in medieval Italy were richly decorated with frescoes or furnished with costly floors like the marble pavement installed at Anagni by the Cosmati family of papal builders around 1231 (see Figure I.3).2 An uncommon architectural configuration further distinguishes the crypt; in the thirteenth century, it could be entered only from the town square, through a doorway on the west side of the transept (Figures 1.8 and 1.9).3 Accordingly, the crypt was not really a “crypt” in the conventional sense.4 Rather, it functioned both as a richly decorated burial chamber for the remains of local saints and as a type of palatine chapel oriented toward the papal residence across the piazza.5 Yet, it is above all the perplexing combination of images contained within its iconographic program that has baffled art historians from the time of its first investigation by Pietro Toesca in 1902.6 Anyone who has visited the Anagni crypt has likely experienced the distinct interpretive difficulty of its sweeping mural scheme. Many scholars have noted that, while the fresco program conveys a sense of conceptual and formal unity, the true nature of this unity remains unclear.7 This interpretive difficulty arises in large part from the mural’s thematic diversity, which combines biblical, hagiographical, apocalyptic, theological, medical, and cosmological images within a stylistically and spatially unified pictorial program.

1.8. Three-dimensional rendering of Anagni Cathedral. Arrow shows location of original entrance to the crypt and the Oratory of Saint Thomas Becket.

Like Cardinal Conti’s murals at Santi Quattro Coronati, the Anagni frescoes engaged with the highly versatile concept of the medieval encyclopedia. Yet, whereas the Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes featured classic encyclopedic motifs and were organized with scholastic clarity, the crypt frescoes adopted a more open-ended organization and a significantly more variegated iconographic repertoire. Indeed, the Anagni frescoes could most appropriately be compared to the particular type of encyclopedia known as the florilegium, which was an anthology of religious and scientific motifs collected as supports for contemplation in a manner comparable to picking flowers and herbs for medicinal purposes.8 Florilegia could be organized in any number of idiosyncratic ways and did not have to be read or studied in linear order.9 Analogously, the Anagni mural appears to have been devised as an open-ended compendium of knowledge in which different pictorial motifs could be spliced together in various ways to produce different interpretive outcomes. The collection of scholarly pictorial motifs near the crypt’s entrance provides a conceptual basis for understanding the Anagni fresco scheme. The diagrams representing the microcosm, the interconnections between the elements, and the planets and constellations foreground an understanding of the world in which all material things are purposefully bound (Figure 1.10). The epigraph inscribed on the books near Hippocrates and Galen articulates this philosophical premise: “That which is in this world results from the concatenation of the elements. It is from these that all things created are formed.”10 The view that humans and the material universe are inextricably linked was the founding principle of all medieval philosophical systems. The chapters that follow detail how Cardinal Conti’s hall calls attention to this philosophical idea by unifying architectural space with paintings that linked divine creation with human ingenuity and perseverance. The Anagni crypt follows the same conceptual pathway but arrives at a more complex and thematically diverse presentation of the material world’s fundamental interconnectedness.

In characteristic fashion, the crypt’s fresco program juxtaposes erudite diagrams with hagiographical images that address the funerary dimension of the space (Figure 1.11). Narrative images and iconic portraits in the two lateral apses contextualize the relics of the local saints Secundina, Aurelia, Neomisia, and Sebastian, which are contained in the crypt’s altars (Figure 1.12).11 Relatedly, an extensive narrative sequence spanning the lower register of the central apse recounts the legendary transfer of the bodily remains of the town’s patron saint, Magnus, from the site of his martyrdom near Fondi to Anagni Cathedral (Figure 1.13).12 As Michael Q. Smith aptly demonstrated, this translation cycle was designed as a typological analog to the series of Old Testament narratives about the travels of the Ark of the Covenant.13 These narratives, depicted in the vaults above the central aisle, introduce a variety of innovative compositional designs with ornamental crosses, medallions, trapezoids, and kaleidoscopic circles in order to tell the story of the ark’s tortuous journey across Israel and Philistia (Figure 1.14). The crypt’s narrative climax is organized in and around the central apse, where eight painted fields display the events surrounding the reversal of creation foreseen by the prophet John and codified in his Book of Revelation.

That this wondrously diverse collation of iconic, narrative, ornamental, philosophical, prophetic, and theological imagery was meant to be understood as a conceptually unified whole might seem unlikely. Yet, unity is precisely what the crypt’s stylistic coherence and spatial continuity convey. Indeed, the frescoes’ capacity to hint at their own conceptual unity while at the same time denying access to any such holistic understanding is, to my mind, what makes the Anagni crypt a monument of enduring importance in the history of Italian art. This tension arises particularly at the level of spectatorship. For viewers, the cognitive strain experienced in the face of iconographic complexity is exacerbated by the real-life limitations of embodied spectatorship. Viewers in the Anagni crypt explore the painted space with eyes and bodies that face the world in one direction at a time; yet the sheer number of painted forms and figures in view makes it difficult to stick to any single interpretive pathway. As viewers move through the space, new paintings come into view and others disappear. This experience is particularly heightened with the vault frescoes, whose concave surfaces can be seen only at a certain proximity, and whose diagrammatic and kaleidoscopic compositions require viewers to turn their bodies while gazing upwards in order to see the images “right side up.” This physical pivoting combined with the diffuse attention induced by the mural’s figural saturation diminishes one’s sense of interpretive directionality in the fresco program as a whole.

As I demonstrate in Chapter 5, the distinct difficulty of interpreting the Anagni crypt was an integral aspect of the mural’s purpose and function. Rather than affording an “external” vantage point from which the mural could be seen in full, the crypt required viewers to experience the frescoes from within, and thereby to experience themselves as constituent elements of the monument. In other words, the Anagni crypt made its human beholders experience their physical and cognitive limitations in order to show them that they too belonged to the interconnected world conceptualized in the mural’s iconographic program.

Palace Painting in Thirteenth-Century Rome

Prior to the recovery of the Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes, the decades bookended by Honorius IV’s splendid apse mosaic at San Paolo fuori le Mura (ca. 1220–30) and Nicholas III’s Sancta Sanctorum (ca. 1277–80) seemed almost devoid of significant artistic commissions. In art historical studies, the artistic “void” of the mid-thirteenth century was typically linked to the period’s political turbulence, marked by the long-drawn-out conflict between the papacy and Emperor Frederick II.14 The general thinking was that during such volatile times, the typical patrons of large-scale artistic enterprises – popes, cardinals, and members of Rome’s nobility – chose to avoid any expenditures that might seem unwarranted or frivolous. Today, almost two decades after the initial discovery of Conti’s painted hall, our perspective on the cultural and artistic situation in Rome during the central decades of the thirteenth century has changed radically. We now know that this period witnessed an unprecedented flowering in papal court culture and gave rise to entirely new forms of artistic expression through ambitious projects created for Rome’s most prestigious residences. We can now also appreciate that these artistic and cultural developments occurred in parallel with – and to some extent were fueled by – the simmering political rivalry between the papal court in Rome and the Hohenstaufen court in southern Italy.

Most surviving large-scale fresco and mosaic decorations from the thirteenth century are found in Rome’s myriad basilicas, including San Paolo fuori le Mura, San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Santa Maria Maggiore, Santa Maria in Trastevere, and Santa Maria Nova. Generally speaking, these works involved adaptations and refinements to iconographic schemes and compositional modes that had been in circulation for centuries in Rome: symmetrically arranged apse compositions with holy personages set against paradisiacal backgrounds, and narrative sequences featuring biblical and hagiographical stories organized as grids on church walls. What sets the Santi Quattro Coronati murals apart from these ecclesiastical works is their thematic focus on encyclopedic knowledge, their use of complex allegorical modes of representation, and their setting in a cardinal’s residence. In the context of Roman art, Conti’s frescoes are a rare instance of the survival of medieval palace paintings. However, as shown by the substantial evidence gathered in Serena Romano’s recent installations of La pittura medievale a Roma, Conti’s frescoes were not the only “palace paintings” created in Rome during the thirteenth century. Evidence of contemporaneous non-ecclesiastical paintings exist at San Clemente, San Saba, Santa Maria de Aventino, Abbazia delle Tre Fontane, and the Palazzo Senatorio on the Capitoline Hill. The magnitude and comparable intactness of the Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes allow them to serve as an anchor point around which these more fragmented palace paintings can coalesce. However piecemeal this evidence might be, it leaves little doubt that thirteenth-century Rome was home to a robust corpus of residential and palatial frescoes whose painterly sophistication and thematic innovation rivaled the city’s better-known ecclesiastical wall decorations.

Among the most tantalizing fresco fragments to be considered in conjunction with the Santi Quattro Coronati murals are the vivid representations of allegorical animals discovered in the Dominican monastery attached to the basilica of San Clemente.15 Painted in the mid-thirteenth century, the frescoes likely formed part of a larger decorative program created for Cardinal Raniero Capocci, one of the highest-ranking members of the Roman Curia and an ardent opponent of Emperor Frederick II. His situation at San Clemente appears to have been similar to that of Stefano Conti at Santi Quattro Coronati. Since San Clemente was an ancient titulus church to which no cardinal had been assigned during the thirteenth century, Capocci was permitted to develop parts of the monastic complex into an urban palace.16 The residence appears to have included a frescoed representational hall on the second floor of the east wing of the current monastery – a direct equivalent to the great hall at Santi Quattro Coronati. Alas, today only small sections of these medieval frescoes survive in the roof space of the edifice, providing little indication of what the hall’s decorative program looked like in the thirteenth century.17 While similarly fragmented, the allegorical animals preserved in the small private chamber of the tower in the north wing give a better sense of the sophistication and thematic outlook of Capocci’s mural decorations. Flanking a small window on the west wall are delicately executed representations of a stag and a doe. These are matched, in corresponding locations on the east wall, by images of a snarling lion and a wild griffin sharpening its claws (Figure 1.15). The four creatures appear against blue and green backgrounds strikingly similar to those in Conti’s great hall at Santi Quattro Coronati. The snarling lion at San Clemente, as Serena Romano has shown, invites comparison with the related figure found above the principal doorway in the south bay of Conti’s hall (Figure 1.16). Taken as a group, the allegorical animals at San Clemente are also evocative of what Eva Hoffman has described as the “international court imagery” found on Byzantine and Islamic textiles as well as in the twelfth-century mosaic decorations of the Norman reception room in the Royal Palace at Palermo (Figure 1.17).18 The decorative scheme in the Norman hall includes symmetrically arranged images of lions, deer, and griffins rendered in profile. Capocci likely had occasion to see these mosaics during his diplomatic visits to Frederick II’s court in Sicily. One such visit was memorably recorded in Leonardo Fibonacci’s mathematical treatise Flos, which is styled as a dialogue between Capocci and Frederick II.19 The iconographic and compositional parallels between the Norman reception room and the frescoes at San Clemente and Santi Quattro Coronati suggest that the latter two monuments formed part of a broader network of Mediterranean court art.

That Rome was party to a Mediterranean courtly culture is confirmed by another set of Roman murals similarly evocative of Sicilian court imagery: the puzzling cosmological images found in the truncated residential tower attached to the basilica of San Saba on the Piccolo Aventino.20 Three frescoed roundels show an enthroned figure flanked by female archers with fluttering veils (Figure 1.18). Scholars have offered differing interpretations of these enigmatic figures, for which few direct iconographic equivalents survive. Most convincing is the suggestion from Irene Quadri, who placed the figures in conversation with the thoroughly illuminated Liber astrologiae, a pictorial treatise created for Emperor Frederick II around 1230 by a certain Georgius Fendulus.21 The Liber astrologiae includes an array of visually compelling, full-page illuminations representing the zodiac signs, the planets in their “celestial houses,” and the decans assigned to each of the twelve constellations (Figure 1.19). Quadri aptly notes that the codex’s images of planets enthroned as medieval rulers resemble the seated figure at San Saba, and, likewise, that several of the figures in the manuscript’s gallery of decans evoke the elegantly draped archers in the frescoes. These iconographic links further suggest that the San Saba murals may have originally featured a more elaborate cosmological scheme that highlighted the complex interconnections between the months of the year and the varied influences exerted by celestial objects on the natural world and human life. If the enthroned human figure at San Saba was indeed intended to represent a planet, it would be one of the earliest known representations of a planetary ruler in medieval Italian monumental art. Along with the allegorical animals at San Clemente and the myriad erudite pictorial motifs in Stefano Conti’s fresco cycle, the San Saba fragments strengthen the well-documented cultural and scientific links between Roman and Sicilian court culture. More and more, we are realizing that, despite the political tensions between the papal and imperial courts during the central decades, the two arenas enjoyed significant intellectual exchange in the realms of science, poetry, and – not least – the visual arts.22

Calendar imagery is one area in which the newfound frescoes at Santi Quattro Coronati serve an important coalescing role vis-à-vis the larger corpus of medieval Roman palace painting. Judging from the surviving evidence, large-scale calendars executed in fresco formed part of the standard repertoire of thirteenth-century Roman noble and monastic residences.23 Indeed, Conti’s Santi Quattro Coronati residence included two such frescoed calendars. The small room adjacent to the Sylvester Chapel on the ground floor features a (now mostly ruined) liturgical calendar in which the months of the year are represented as large sheets of parchment held by standing figures (Figure 1.20).24 This liturgical almanac is complemented by the frescoes depicting the labors of the months on the walls of the south bay in the great hall. Both the liturgical calendar and the labors of the months establish pictorial and thematic links with a series of other calendars that once decorated the walls of thirteenth-century Roman residences.

The enigmatic fresco scheme at San Saba, for example, included a cycle of the labors of the months alongside the cosmological imagery discussed above. In the cycle’s current state of preservation, only the months from August to December survive (see Figure 3.15).25 The September scene shows a figure tromping around in a rectangular trough brimming with colorful grapes, while subsequent scenes show a cooper constructing a wine barrel (October), two oxen pulling a plow to till the soil (November), and a pig being slaughtered for meat (December). As discussed in Chapter 3, this sequence of agricultural activities corresponds closely to those represented in Stefano Conti’s great hall.

Frescoes depicting the labors of the months were also included in the wall decorations created for a space of unknown dimensions in the medieval Palazzo Senatorio on the Capitoline Hill.26 The few remaining fragments of these murals portray natural scenery and ornamental frames, along with two scenes of labor showing the agricultural activities associated with the summer and fall. In one of the scenes, a farmer has collected a heap of seeds in his cloak for sowing; this activity corresponds to that seen in November at Santi Quattro Coronati (see Figure 3.3). Another fragment shows two farmers with sticks heaving a heap of grain onto a grinding stone. This threshing is also found at Santi Quattro Coronati, where it appears under July at the center of the south wall. The fragmented calendar frescoes, which today are hidden in a small chamber used for photocopiers, probably formed part of a larger decorative scheme created for a meeting hall used by medieval Rome’s trade guilds in the thirteenth century. Irene Quadri has linked the frescoes with a series of interior renovations documented to have taken place in the Palazzo Senatorio in the 1250s. These renovations, according to Quadri’s analysis, may have been requested by the Bolognese nobleman Brancaleone degli Andalò, who served as Rome’s senator in 1252–5 and again in 1257–8.27

Another large-scale calendar mural was created for the portico of the monastic residence at Santa Maria de Aventino at some point in the 1240s or 1250s.28 Destroyed during Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s remodeling of the church and monastery in 1765, the frescoes had been recorded a century or so earlier in watercolor drawings created by Antonio Eclissi on commission from the Italian collector Cassiano dal Pozzo.29 Eclissi’s drawings show two frescoed lunettes, each decorated with a detailed liturgical calendar organized as six columns of text superimposed with images of the labors of the months (Figure 1.21). When Eclissi produced his drawings in the mid-seventeenth century, the fresco showing the first half of the calendar year (January–June) appears to have been fully intact while that representing the second half (July–December) was already badly damaged. Eclissi’s drawings show two lunette-shaped frescoes that were clearly made for a vaulted portico. The upper portion of the first fresco includes the portrait of a deacon saint flanked by two unidentified hagiographical stories. At the top left, a nobleman kneels in prayer before the saintly figure while a servant attends to his horse. At the top right, a bishop addresses a sick woman lying on the ground with a young boy (presumably her son) standing beside her. The presence of a truncated caption, MIRACVLA, along the lower border suggests a story of healing.

Organized as a horizontal strip below the hagiographical stories are the agricultural and courtly activities associated with the months of the year. January is depicted as a man seated before a fire, February as a young farmer pruning a thicket, March as an enthroned woman removing a thorn from her foot, April as a boy herding sheep, May as a nobleman riding with a falcon on his right arm, and June as a man harvesting grain. This iconographic program aligns closely with that in the great hall at Santi Quattro Coronati, although the latter fleshed out its agricultural motifs into more elaborate scenes with multiple figures.30 The lost Aventine fresco combined two types of calendars into a single composition. While the labors at Santa Maria de Aventino were comparably spartan versions of the agricultural scenes in Conti’s great hall, the detailed columnar calendar displayed in the lower part of Eclissi’s drawing was as scholarly in nature as the liturgical calendar decorating the Sylvester Chapel’s antechamber (Figure 1.20). These text-based calendars were to some extent frescoed versions of the type more commonly seen in liturgical manuscripts. The close adherence to manuscript conventions can be observed in the neatly gridded boxes of each calendar “page,” and in the use of alternating black and red script against backgrounds that clearly imitated parchment. Like liturgical calendars in manuscript form, these mural calendars required not only basic literacy but also a more intricate understanding of the computational systems that underpinned medieval time measurement. In order for the Santa Maria de Aventino and Santi Quattro Coronati calendars to function perpetually, viewers had to perform their own calculations for determining when important dates would occur. For example, to determine the date of Easter Sunday in a given year, viewers could use the “golden” numbers of the metonic cycle (both calendars include these numbers in the far left column of each calendar page), along with the hebdomadal letters corresponding to the day of the week (inscribed in the second column from left), to calculate the precise date for the first Sunday after the full moon that occurs on or after the vernal equinox.

The liturgical calendars at Santi Quattro Coronati and Santa Maria de Aventino were overtly interactive images that transposed aspects of learned manuscript culture into the medium of wall painting. This particular type of calendar appears to have been quite popular in thirteenth-century Rome, for another such calendric frieze is known to have decorated the portico of the monastic residence at the Cistercian abbey of Tre Fontane on the ancient Via Laurentina.31 These frescoes were visible as late as the eighteenth century, when they were recorded in a drawing by Seroux d’Agincourt. The drawing produced by the French archeologist shows that the almanac was organized horizontally in the manner of a Gothic clerestory with tri-lobed window niches populated by male figures unfurling scrolls of parchment.32 The design closely matched the one preserved in the ground-floor antechamber at Santi Quattro Coronati. The latter, as Silvia Maddalo has suggested, may well have served as inspiration for the calendar at Tre Fontane.33

The newfound frescoes at Quattro Coronati have also impacted our understanding of the so-called Vita Humana murals at Tre Fontane, commonly dated to around 1300.34 The nine surviving panels of the Vita Humana cycle originally formed part of a substantial mural scheme created for the great hall in the abbot’s quarters at the Cistercian monastery (Figure 1.22). Like the clerestory-level paintings in Cardinal Conti’s great hall, the Tre Fontane frescoes feature sophisticated allegorical representations set against ogive-arched windows to form a horizontal gallery. The Tre Fontane frescoes include two unusual wheel diagrams that outline the conditions of human mortality and sensibility (Figures 1.23 and 1.24). These diagrams combine with an eclectic selection of motifs drawn from medieval bestiaries, fable collections, and the Old Testament. In her authoritative analysis of the murals, Kristin Aavitsland has shown that the cycle’s disparate pictorial motifs can be understood as a visual florilegium aimed at encouraging associative meditation on the basic conditions of postlapsarian human existence.35 This contemplative cycle opens with a representation of the physical hardship suffered by Adam and Eve beyond the gates of Eden. Considered in the context of the other eight panels, the singular biblical scene appears excerpted from its broader narrative context to serve as a springboard for speculation around the origins of the human condition and the idea that manual labor could serve as a means to salvation in accordance with Cistercian thinking.36 Subsequent scenes in the cycle define the distinctive characteristics of human existence from a variety of perspectives. A wheel diagram portrays the five senses of the human body through symbolic representations of animals in whom each of the senses was believed to be well developed: a spider for the sense of touch, an ape for taste, a wild boar for hearing, a hound for smell, and a lynx and an eagle for vision. The animal symbols are arranged in six medallions encircling a central medallion that bears the image of a man in his youth, the phase of life when one is most susceptible to the senses. This diagram is accompanied by a second formally equivalent wheel diagram showing the various stages of human life, from childhood through old age to death, pictured as an old man on his deathbed at the diagram’s center.

According to Aavitsland, the two wheel diagrams are best understood as rhetorical “exempla,” in the sense that their neat geometric organization modeled the way medieval students were taught to mentally organize knowledge in the form of easily retrievable “memory pictures.”37 As such, the two diagrams underscore the intellectual engagement that the Vita Humana frescoes were intended to solicit. Each panel functioned as an externalized memory picture that could trigger a chain reaction of internal memory pictures in the minds of beholders. The wheel diagrams invited spiritual meditation around the vanity of sensory pleasure and the transitory nature of human life. In turn, contemplation of these aspects of the human condition would induce more edifying forms of thinking around actionable strategies for avoiding sinful indulgence and for overcoming corporeal transience through ascetic living in accordance with the principle of contemptus mundi, or disdain for the world.

The Vita Humana frescoes postdate the Quattro Coronati murals by half a century, and there are important formal, iconographic, and contextual differences between the two monuments. Yet, their shared characteristics are worth highlighting. Both fresco cycles demonstrate an interest in defining the distinct conditions of human existence, and in deploying erudite and interpretively challenging motifs to spur sustained intellectual engagement. Both were created for large representational spaces where members of Rome’s ecclesiastical elite would meet, dine, and engage in conversation. Both were “rediscovered” after centuries of oblivion – the Tre Fontane frescoes in 1960 and the Quattro Coronati murals in 1995 – and even though these retrievals were both cases of happenstance, their rediscovery served to underscore the sheer quantities of medieval Roman palace paintings that have been lost permanently. To us, these monuments surely appear more unusual than they did to the eyes of Rome’s thirteenth-century elite, who were likely just as accustomed to allegorical palace frescoes as they were to the mesmerizing apse mosaics and grand narrative cycles that we tend to associate with “medieval Roman art.”

Art, Knowledge, and Papal Politics

Cardinal Conti’s great hall is situated on the second floor of a large tower that forms part of the medieval palace attached to the twelfth-century church of Santi Quattro Coronati (Figures 1.25–1.27).38 According to a dedicatory inscription found in the complex’s ground-floor chapel, the palace was built on commission from Stefano Conti and completed by 1246.39 Stefano was a particularly well-connected cardinal of the Roman Curia. His family, the powerful Conti clan of Anagni, was the dominant force in Roman politics during the first half of the thirteenth century. Stefano’s uncle, Lotario dei Conti di Segni, had ruled for eighteen years as Pope Innocent III (1198–1216); and two other relatives, Ugolino and Rinaldo, ruled as popes Gregory IX (1227–41) and Alexander IV (1254–61), respectively.40 The family also enjoyed significant influence in Roman civic affairs. Stefano’s father, Riccardo Conti, was a powerful nobleman whose wealth and authority were emblematized in the largest of Rome’s baronial towers, known as the Torre dei Conti, the base of which still rises above the Forum of Nerva.41 In 1216, Pope Innocent III appointed Stefano as cardinal deacon of the church of Saint Hadrian, housed in the former Curia Julia on the Roman Forum. In 1228, Stefano was promoted by Pope Gregory IX to cardinal presbyter of Santa Maria in Trastevere. The relatively small size of the college of cardinals in the period allowed Stefano to remain titular cardinal of the trans-Tiberian basilica and at the same time develop Santi Quattro Coronati into a lavishly decorated residence for himself.42 Located a few hundred meters from the Lateran, the venerable basilica had been reconstructed in the twelfth century as a relatively small church set within a significantly larger architectural shell. This diminution made it possible for Stefano Conti to integrate parts of the old basilica into his new palace.43 In the decades following Stefano’s death in 1254, the Santi Quattro Coronati residence would remain one of Rome’s most desirable dwellings. It served as home to Charles I of Anjou during the Sicilian king’s stint as senator of Rome, and later as cardinalate residence to personages including Ottaviano degli Ubaldini – apparently known to his contemporaries as “the Cardinal” – and the notorious Benedetto Caetani, who would later rise to Saint Peter’s chair as Boniface VIII (1297–1304).44

1.26. Thirteenth-century layout of Santi Quattro Coronati complex; cardinal’s residence in blue; twelfth-century basilica in green; Benedictine monastery in yellow.

1.27. Partial plan of cardinal’s residence, Santi Quattro Coronati; left plan shows ground floor with Sylvester Chapel; right plan shows second floor with great hall.

Stefano Conti’s curial career coincided with two important developments in the history of the medieval papacy. The central decades of the thirteenth century witnessed an unprecedented cultural flowering at the papal court due to its active recruitment of learned individuals and its embrace of the “new” learning made available through translations of ancient and medieval Arabic texts. This very same period was marked by the long-drawn-out conflict between the papacy and its great imperial rival to the south, Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. This conflict had started in 1198, when Frederick was crowned king of Sicily at age three. At the time, Stefano’s uncle, the newly elected Pope Innocent III, was named as the young ruler’s guardian while the eminent Cardinal Cencio Savelli (later Pope Honorius III) was appointed as Frederick’s tutor. Pope Innocent had planned to groom Frederick into a papal ward and prevent the young king from assuming titles and powers that might eventually threaten the papal state. The plan, however, proved unsuccessful. Frederick quickly amassed significant military strength and diplomatic support to position himself as a true rival to papal power. In 1220, Honorius III agreed to crown his former pupil Holy Roman Emperor on the understanding that Frederick would immediately bring his armies east to salvage the Fifth Crusade (or, God forbid, be killed in the effort). However, to the papacy’s great annoyance, Frederick delayed his departure for the Holy Land indefinitely, devoting his efforts instead to securing territorial holdings on the Italian peninsula.

Under Pope Gregory IX, the papacy took a firmer line. Immediately upon his ascension to the papal throne in 1227, Gregory excommunicated Frederick and dispatched the papal army to reclaim lands that had been seized by the emperor from Riccardo Conti (father to Stefano Conti and uncle to Gregory IX) in southern Italy. A shaky truce between the pope and Frederick was brokered in 1230 in Anagni, but the tension between them continued until 1239, when Gregory excommunicated the emperor for a second time and launched a vociferous propaganda campaign against the empire.45 By the time Innocent IV (1243–54) was elected, the war had reached a climax: Frederick stationed his troops to the north of Rome and the pope fled in secrecy to Lyons to seek protection from the French King Louis IX. From his new base in Lyons, Pope Innocent renewed the emperor’s excommunication in forceful terms. However, despite the epistolary bravado issuing from his chancery, the pontiff decided to remain north of the Alps until Frederick’s death from dysentery in 1250 made it safe to return to the Italian peninsula.

This politically turbulent period was also a time of significant cultural expansion at the papal and imperial courts. Historical records show that the two courts developed into vibrant arenas of intellectual discourse as both Frederick and his papal rivals actively recruited university-educated administrators as well as doctors, scientists, and artists to their respective entourages.46 These parallel efforts at curial intellectualization were in part practical responses to growing bureaucratic needs, but they were also important extensions of the political rivalry between the pope and the emperor. Rather than impede cultural expansion, the political conflict appears to have stimulated the period’s artistic and epistemic flowering. Not only did scholars and artists gain increased access to financial support as the two courts vied for their services; the circulation of texts and learned men between the two cultural arenas also spurred productive intellectual exchange, as Agostino Paravicini Bagliani has aptly demonstrated.47

Stefano Conti’s murals responded to these complexly intertwined historical circumstances. This was particularly so with the Sylvester Chapel frescoes, which advanced an unambiguous assertion of papal power at a time when Frederick remained camped on Rome’s doorstep.48 With Pope Innocent and most of the Curia in self-imposed exile across the Alps, Stefano Conti was one of four cardinals selected to stay behind and handle the affairs of the papal state and direct the ongoing war with Frederick. From his fortified residence at Santi Quattro Coronati, Stefano effectively ruled the city for about a decade (ca. 1244–54) as the papally appointed cardinal vicar of Rome (vicarius urbis Romae).49 During this period, the cardinal publicly declared – on two occasions, in 1246 and again in 1248 – the church’s crusade against Frederick.50 Conti’s Sylvester Chapel frescoes were in many ways conceived as a pictorial complement to this verbal propaganda.51 Designed as political spin in visual narrative form, the paintings reminded viewers of how the fourth-century emperor Constantine had (allegedly) agreed to transfer authority in all religious and temporal matters to the then pope Sylvester (d. 335). Across the painted cycle, Constantine is depicted as submissive toward Sylvester; in one scene the emperor is seen humbly walking on foot as he leads the pontiff’s white horse toward the Lateran Palace (Figure 1.28).52 The procession motif was a deliberately anachronistic reference to a feudal ritual of homage known as the “office of the groom” (officium stratoris).53 Its use in the Sylvester Chapel invited viewers to metaphorically project the ongoing political struggle between Innocent IV and Frederick II onto the fourth-century tale of Constantine’s transfer of power, which centuries earlier had been codified in the spurious legal charter known as the Donation of Constantine.54 In this way, Conti’s narrative frescoes extended the ongoing propaganda war between the imperial and papal chanceries, wherein both sides made inventive use of the forged document.55

The murals in Santi Quattro Coronati’s great hall expanded the jurisdictional claims of the Sylvester frescoes to include all essential temporal knowledge, including time reckoning, agronomy, astrology, moral law, and antiquarianism, along with the philological and mathematical disciplines. Considered as a whole, and seen in its political context, Conti’s frescoed hall articulates the papal Curia’s embrace of worldly knowledge as an aspect of political power. This newly fashioned identity for the papacy, as a cultured monarchy and a proprietor of learning, is neatly encapsulated in the figure of King Solomon. The biblical ruler is positioned at the center of the north wall frescoes, flanked by a cortège of armored virtues, and directly in the line of sight of visitors entering through the principal doorway (Figures 1.6 and 1.29). King Solomon was understood by his thirteenth-century interpreters as a model ruler who combined virtuous kingship with divinely ordained wisdom. Such widespread admiration for the biblical ruler lies behind the epithet “new Solomon,” which was lavished on Frederick II as well as on Pope Innocent III to describe their mastery of worldly knowledge, particularly in the realm of law.56 The figure of Solomon at Santi Quattro Coronati was perhaps intended as homage to the late Innocent III, whose eighteen-year reign had launched the papacy’s embrace of scholarship and, not least, the Conti family’s decades-long dominance in curial politics. The murals depict Solomon in the guise of an Ancient Roman emperor so as to implicitly proclaim the pope as the true heir to the religious and temporal powers once possessed by Constantine, and now “illegitimately” claimed by Frederick.

In the north bay frescoes, Solomon is the central figure around which Conti’s innovative cycle of virtues and vices revolves. Several of the vanquished villains in this allegorical cycle were thinly veiled pictorial allusions to Frederick. The myriad broadsides issued by the papal chancery against the emperor left no doubt that the church perceived Frederick not only as the present-day arch-nemesis of the pope but as an embodiment of the Antichrist.57 For example, in a pamphlet issued by Gregory IX in 1239, titled “A beast rose from the sea” (Ascendit de mare bestia), the pontiff likened Frederick to the apocalyptic dragon Leviathan.58 Stefano Conti’s virtues cycle engaged with these rhetorical polemics; several of the foes trampled underfoot by the virtues – particularly Pharaoh, Nero, Simon Magus, and Muhammad – were understood in strikingly similar terms as historical incarnations of the Leviathan/Antichrist motif. Like Prudentius’s allegorical portrayal of battles between the virtues and vices in the Psychomachia, the scriptural passages describing God’s battles against the sea monster were metaphorical renderings of the struggle between good and evil, and between order and chaos. Conti’s virtues cycle thus framed the papacy’s conflict with Frederick as an extension of the church’s historical struggles against the forces of chaos and evil. In the same way that the mural program as a whole cast the papacy as the implicit heir to Solomon’s wisdom, the virtues cycle in the north bay implicitly cast Frederick as an historical agent of chaos in the molds of Pharaoh and Nero.

In this context, too, the murals in the crypt of Anagni offer additional evidence of the papacy’s development of monumental painting as an instrument of political propaganda. Aspects of these wondrously diverse fresco decorations can be understood as veiled commentaries on the contemporaneous political struggle between Frederick II and Pope Gregory IX, who in all likelihood sponsored the crypt’s murals. This is particularly so with the episodes drawn from John’s Revelation in the crypt’s main apse and its surrounding walls, which align with the eschatological outlook of Conti’s virtues cycle. Frederick Hugenholtz, in his rigorous historical analysis of the Anagni crypt, argued that the crypt’s apocalypse frescoes should be interpreted in the context of Gregory IX’s well-documented preoccupation with the world’s apocalyptic end and the pope’s frequent characterizations of Frederick II as the Antichrist (see Figure 1.13).59 According to Hugenholtz, the Revelation cycle at Anagni was intended as a papal “manifesto” directed at the emperor. The cycle was an attempt to situate the period’s political conflict in an eschatologically informed history in which the papacy belonged on the side of Christ, whose victorious return would bring an end to the line of temporal usurpers to which Emperor Frederick II belonged.60 Other individual images in Anagni have also been interpreted as motivated by the period’s papal–imperial polemics. Miklos Boskovits, for example, has argued that the scene of Saul’s anointment by Samuel in the south aisle asserted the power of the pontiff to bestow the title of king (Figure 1.30) Thus, in Boskovits’s interpretation, Samuel and Saul were to be understood as allegories of Gregory IX and Frederick II, respectively.61

Beyond their political facets, the Anagni frescoes constitute one of the most important historical testaments to the thirteenth-century papacy’s interest in worldly knowledge. Clustered around the crypt’s entrance is a collection of cosmological diagrams, including images of the microcosm, the zodiac, and planets, along with a so-called syzygy schema outlining the connections between the four elements and their physical properties. Accompanying these cosmological diagrams are portraits of four (no longer identifiable) astrologers and the ancient physicians Hippocrates and Galen. These erudite motifs are exceedingly rare in the realm of monumental painting and were clearly directed at the highly educated members of the papal Curia. As will be seen in Chapter 5, the cosmological images at Anagni commemorated the thirteenth-century papacy’s cultivation of astrology and medicine, which were valued for their immediate practical utility in the realm of politics. Astrology and other predictive arts could be harnessed to procure advance knowledge of future events, including natural phenomena, forthcoming wars, and the future fates of individual persons. The utility of medicine was its ability to safeguard one’s continued rise in the curial hierarchy by curing ailments and slowing the body’s natural corruption. As Paravicini Bagliani has shown, members of the thirteenth-century Curia harbored significant anxiety about illness, death, and the brevity of life.62 Indeed, the presence of the pope and his court in Anagni was directly related to curial members’ wish to avoid the “incendiary air” and malarial “fevers” that plagued Rome in the hot summer months.63 The medieval papacy was an institution that rewarded longevity; any cardinal with his sights set on Saint Peter’s chair needed, before all else, to outlive whoever currently occupied it. On the other hand, pontiffs were considered to be particularly susceptible to illness and death; medieval popes were commonly elected toward the ends of their lives and, once elevated, “never lived very long, but died in a short space of time,” as Peter Damian noted in his treatise On Brevity.64 Recognition of the political implications of illness and mortality was an important motivating factor for the thirteenth-century papacy’s cultivation of worldly knowledge. The Anagni frescoes engaged with these cultural and political developments by placing pictorial motifs for astrology, medicine, and cosmology in conversation with a larger mural program devoted to broad philosophical speculation about sacred history, political eschatology, and the place of humankind in the cosmos.

The process by which thirteenth-century court culture became intellectualized was multifaceted. There was, on the one hand, increased emphasis on education among the clerical elite.65 From Innocent III onward, possessing a degree from one of Europe’s burgeoning universities became a de facto criterion for promotion within the curial hierarchy.66 By midcentury, this consistent practice of promoting candidates with master’s degrees to the college of cardinals had turned the court into a circle of rigorously educated and comparatively outward-looking individuals. Increasingly, curial members had been exposed to Aristotelian and Islamic philosophical writings, which were commonly discussed and disseminated in thirteenth-century university circles.67 Such increased exposure to new and at times controversial lines of thinking spurred a concerted expansion in the kinds of learning considered within the papacy’s purview. In addition to their traditional focus on theology and law, popes and cardinals now actively cultivated natural philosophy and what Roger Bacon termed “experimental science.”68 These forms of knowledge were increasingly understood as necessary instruments for the church’s continued supremacy in political affairs.69

The first phase of this intensified cultivation of worldly knowledge can be traced to the 1220s, when the translator and polymath Michael Scot appears to have enjoyed the patronage of popes Honorius III and Gregory IX.70 A papal decree of the time describes Scot as an eminent scholar and declares that “the apostolic seat delights in erudite men.”71 In the late 1220s, Scot moved on to the court of Frederick II in Sicily, where he served as court astrologer and continued his translation activities while also producing original writings on topics ranging from cosmology and music to physiognomy, alchemy, and the healing arts.72 Scot was one of several scholars employed by both pope and emperor, demonstrating what Steven Williams calls a “shared cultural world of the papal and imperial courts.”73 Texts and manuscripts also appear to have moved with ease between the two courts. A treatise on delaying the misfortunes of old age (De retardatione accidentium senectutis), written by a certain Dominus Castri Goet in the 1240s, exists in two slightly different versions, one of which bears a dedication to Innocent IV and the other to Frederick II.74 The treatise incorporates material from a small handbook known as the “Secret of Secrets” (Secretum secretorum), which had been translated from Arabic into Latin in around 1230 by a papal cleric known as Philip of Tripoli.75 At the time, it was believed that the “Secret of Secrets” had been written by Aristotle and comprised a collection of exclusive and confidential advice addressed to Alexander the Great.76 Organized as a small encyclopedia for kings and other rulers, the book includes discourses on government, medicine, and astrology, as well as more occult sciences, including alchemy and lapidary magic.77 The text enjoyed widespread circulation at both the papal and imperial courts, and its Aristotelian advice was incorporated into other learned texts, including the writings of Michael Scot and Roger Bacon.78 As Williams has demonstrated, the micro-history of the “Secret of Secrets” and its introduction to the Latin West via the papal court is emblematic of the papacy’s receptive attitude to “new” Greek and Arabic learning. It is one of many examples that capture the pivotal role of the Curia as a center for translation and the production of new knowledge in the first half of the thirteenth century.

The Santi Quattro Coronati Murals and Visual Encyclopedism

Conti’s Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes demonstrate that the Curia’s cultural expansion in the thirteenth century extended to the realm of mural painting. They also suggest that the papacy’s political struggles prompted artistic innovation as a complement to the written propaganda issuing from the Curia’s chancery. Yet, the frescoes at Santi Quattro Coronati can also be examined in relation to a significantly broader development in medieval culture: what might be described as the “encyclopedism” of the scholastic period.79 Viewed in this light, Conti’s murals attest to the broadening interest in the production of knowledge-ordering works, which found expression in the realms of prose and poetry, as well as in the visual arts.

Among the most widely disseminated prose encyclopedias of the scholastic period were Alexander Neckham’s De naturis rerum, Thomas of Cantimpre’s De natura rerum, Bartholomeus Anglicus’s De proprietatibus rerum, Vincent of Beauvais’s Speculum maius, Honorius of Autun’s Imago mundi, and Brunetto Latini’s Le livre du trésor. Like the early medieval compendia of knowledge on which they were modeled, these texts sought to condense the contents of an entire scholarly library into a single volume by synthesizing Greco-Roman knowledge with scriptural materials and theological writings.80 While none of these works were known as “encyclopedias” in the period, they nevertheless conform to our modern understanding of the term.81 Medieval compendia of knowledge were organized in accordance with overarching concepts, which were usually theological and philosophical in nature, such as the six days of creation or the analogy between microcosm and macrocosm.82 Furthermore, like modern encyclopedias, medieval books of knowledge aspired to a certain completeness of coverage, with individual articles on topics ranging from the verbal and mathematical sciences, medicine, law, and theology to geography, agriculture, food, the things of nature, and everyday objects such as tools and clothing. These individual entries were typically written with a certain rhetoric of objectivity and appear to have been aimed at moderately educated audiences.

To describe Conti’s great hall as “encyclopedic” is not to say that written compendia of knowledge served as direct sources for the varied pictorial motifs contained within its fresco cycle. To be sure, the iconographic program at Santi Quattro Coronati, with its combinatory treatment of worldly and theological knowledge, resembles the thematic substance of textual encyclopedias. Yet, there are other important factors that contributed to the frescoes’ encyclopedic character. Among the hallmarks of medieval books of knowledge were their organizational logic and commitment to the idea of completeness. Regardless of the medium in which they were expressed, and regardless of their actual content, all medieval encyclopedias advanced a certain rhetorical claim to comprehensiveness. To my mind, it is this rhetorical posture that most intimately connects the great variety of encyclopedias produced during the scholastic period to the Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes. Conti’s mural cycle reinforces the impression of encyclopedic comprehensiveness through its uniform color scheme, stylistic coherence, painted framework, and treatment of architectural space. In the great hall at Santi Quattro Coronati, fresco decorations extend across four walls and two vaults in such a way that architectural space and painting conjointly create the effect of visual and spatial enclosure. When combined with a stylistically uniform pictorial program that is iconographically premised on the notion of comprehensive knowledge, these spatial characteristics assume their own form of encyclopedic rhetoric. As discussed below, historical viewers could experience the frescoed room as a thematically and stylistically uniform “knowledge-whole” comprised of carefully selected “knowledge-parts” (the liberal arts, the months, the seasons, the virtues, the vices, and the stars and planets). Additionally, the fact that the mural as a whole could never be seen in its entirety but always only in its parts strengthened the encyclopedic rhetoric of the space. The potential for comprehensiveness was kept alive by its non-availability to direct visual verification.

The scholastic period saw not only an increase in the production of encyclopedic works but also increased interest in visualizing knowledge through the use of pictorial structures such as diagrams, tables, charts, and maps.83 These concurrent developments in medieval culture underpinned the creation of “visual encyclopedias,” knowledge-ordering works in which images served as the primary mode of communication. Examples of visually dominant encyclopedic manuscripts include Herrad of Landesberg’s Hortus delicarum (ca. 1176–96) and Lambert of Saint-Omer’s Liber floridus (ca. 1120).84 These richly illuminated codices included a wide variety of diagrams, tables, maps, and other pictorial structures for visualizing knowledge (Figure 1.31). In these manuscripts, images and figures did not merely “illustrate” the codices’ textual contents but instead functioned as self-sufficient pictorial articulations of theological, moral, and philosophical forms of knowledge. Other examples of intrinsically visual encyclopedic manuscripts include spectacular world maps such as the Hereford Mappa Mundi and the Ebstorf Map, both produced around 1300 (Figure 1.32).85 These large-scale sheets of parchment layered historical, theological, and mythological knowledge onto the geographic framework of the known world.86 In both maps, the geographic world was drawn as a circle with the three continents – Asia, Europe, and Africa – arranged around Jerusalem at the center. Alongside geographic locations were texts and images conveying information drawn from biblical stories, classical myths, prophetic material, theological writings, bestiaries, and books of nature. By combining this diverse subject matter within the confines of a circular composition, the Hereford and Ebstorf maps generated distinctly encyclopedic effects. Viewers were presented with vast pictures that appeared to show not only the spatial extent of the world but also its entire history and sacred significance, as though the material and spiritual dimensions of creation had been brought together in a single image.

The twelfth century gave rise to the celebrated portal programs of French cathedrals, which the nineteenth-century art historian Émile Mâle memorably interpreted as encyclopedias fashioned in stone.87 The west portals of the cathedrals of Saint-Denis and Chartres, for example, displayed coherent systems of knowledge, wherein sculptural representations of the months, the zodiac signs, and (at Chartres) the liberal arts were integrated within theologically grounded schemata of Christian salvation history. As Conrad Rudolph has shown, such programs of architecturally embedded sculptures introduced a new form of erudite public art in which theoretical concepts and complex ideas could be elucidated not only through individual figures but also through the innovative systematization of knowledge components into coherent spatial wholes.88 From the mid-thirteenth century onward, comparable large-scale programs of knowledge executed in sculpture and fresco emerged on the Italian peninsula as well. Prominent examples include the Fontana Maggiore in Perugia (ca. 1278), the Florentine campanile reliefs (ca. 1340–60), Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Sala dei Nove frescoes in Siena (1337–40), the sculpted capitals of the Doge’s Palace in Venice (1342–8), and Andrea di Bonaiuto’s frescoes in the Dominican chapterhouse at Santa Maria Novella in Florence (ca. 1369). In a seminal 1896 study, Julius von Schlosser charted the rise and development of these and other “encyclopedic picture-cycles” (enzyklopädischer Bildkreise) from twelfth-century France, via the Angevin court and the burgeoning civic cultures of late medieval Italy, to their alleged artistic culmination in Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura.89 In strictly chronological terms, Stefano Conti’s rediscovered murals slot in between French sculptural programs and the Italian works mentioned above, many of which were created for civic contexts. One wonders what role the Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes would have played in von Schlosser’s grand historical narrative, had they been discovered a century and a half earlier than they were.

The medieval emphasis on visualizing knowledge in the creation of encyclopedic works was not limited to traditional pictorial media. More than in previous centuries, authors of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries explored the generative potential of visual metaphors and literary description in the formation and communication of complex knowledge structures. On the one hand, encyclopedists deployed terms such as image (imago) and mirror (speculum) in the titles of their written works to suggest a particular relationship between knowledge totalities and visual description.90 Through their suggestive titles, works such as Honorius of Autun’s Imago mundi and Vincent of Beauvais’s Speculum Maius proposed that visual structures could most effectively account for the ways in which encyclopedias marshal diverse forms of knowledge into conglomerate wholes. Thus, in the preface to Imago mundi, Honorius of Autun tells his readers that the book has been “given the name Image of the World because the disposition of the whole world can be seen in it as in a mirror.”91 On the other hand, twelfth- and thirteenth-century poets foregrounded the heuristic potential of verbally rendered pictorial programs to embody complex systems of knowledge.92 For example, in Alan of Lille’s De planctu naturae and Chrétien de Troyes’s Érec et Énide, descriptions of the garments worn by individual characters became occasions for the authors to showcase their scholarly erudition.93 The shoes, robes, mantles, and regalia worn by Chrétien’s Érec and Alan’s personified Nature are outfitted with pictures of the sciences and all the plants and creatures of the world, thereby turning these poetic characters into icons for the microcosm–macrocosm analogy.94 Relatedly, didactic poems such as Baudri of Bourgueil’s Adelae comitissae and the Italian work known as L’Intelligenza feature detailed descriptions of rooms of knowledge in which encyclopedic subject matter is presented ekphrastically as medium-specific works of art.95 L’Intelligenza, written in Italy during the second half of the thirteenth century, describes Lady Intelligence’s palatial residence, which is situated at the center of the world and opulently decorated with erudite frescoes depicting the Wheel of Fortune, classical deities, and world-historical events from biblical times, the Trojan War, the lives of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, and Arthurian legend. Baudri’s poem, dedicated to Countess Adela of Blois around 1100, describes the countess’s bedchamber as a spatial and visual microcosm of the world: The walls are covered with tapestries depicting pagan and biblical stories, the floor is inlaid with a mosaic map of the world, the painted ceiling represents constellations and planets, and the bed features sculpted images of the liberal arts, philosophy, and medicine, as well as a finely woven tapestry depicting the Norman invasion of England by William the Conqueror (who was also Adela’s father). Taken together, these texts expanded the classic association between knowledge and cognitive imagery by linking knowledge structures with multimedia pictorial programs that incorporated sculptures, paintings, floor mosaics, tapestries, clothing, and jewelry. Through their innovative use of encyclopedic ekphrasis, the medieval poets made a case not only for the epistemic potential of cognitive visualization but also for the imagined physical activity of viewing specific works of art.

The Fresco Medium and Embodied Spectatorship

Whereas readers of Adelae comitissae and L’Intelligenza were invited to mentally project themselves into verbally constructed rooms of knowledge, visitors to Cardinal Conti’s hall at Santi Quattro Coronati could physically enter a space whose walls displayed the world’s essential knowledge in the form of a visual panorama. Yet, the encyclopedism of Conti’s great hall resided not only in the subject matter of its fresco decorations. To fully understand how the great hall functioned as a large-scale pictorial encyclopedia, we must consider the dynamic interplay between wall paintings, architectural space, and the intellectual engagement and physical movements of its beholders. A central tenet of this book is that the fresco medium was particularly well suited to an iconographic program that thematized encyclopedic comprehensiveness. Unlike oil and tempera painting, where color pigments cling to the surface with the help of adhesive binders, paint pigments applied al fresco penetrate the wall itself, rendering the paintings constituent parts of their architectural matrix.96 The fresco medium unifies painting with its built environment. Thus, to stand inside a room entirely decorated in fresco is in many ways to stand inside the painting itself. At Santi Quattro Coronati, the medium’s environment-forming capacity, along with the uniform color scheme and stylistic coherence of the paintings, strengthened the message conveyed by the iconographic program. The pictorial program’s iconographic orientation around the notion of comprehensive knowledge coordinated with the pictorial medium’s ability to generate the effect of being enclosed within an integrated whole.

In the same way that wall paintings shape how spaces are experienced architecturally, architectural space affects how paintings are experienced as three-dimensional images. In many cases, art historical scholarship overlooks the spatial dimension of wall paintings, treating images in fresco as though they were portable pictures hanging on a wall.97 The use of photographic reproductions in scholarly publications undoubtedly facilitates such abstractions.98 Photographs crop and flatten the world, and so pictures of frescoed spaces often negate mural painting’s environment-forming capacity.99 Rather than isolating images from their architectural environments, my approach restores the spatial condition of medieval murals by focusing on the ways in which frescoed monuments bring viewers and images into relationships of interdependency. In so doing, I draw on the work of key art historical and archeological theorists who have attended to the relational, embodied, and spatial conditions of art. In his landmark study Real Spaces, David Summers advocated for a definition of art that takes into account the “conditions of human corporality and spatial existence.”100 When we attend to artworks in their real spatial conditions instead of focusing solely on their visual aspects, we come to understand that we interact with art in much the same way that we interact with the world more generally – which is to say, bodily as well as cognitively.101 Archeological theorist Ian Hodder’s description of the dialectics of entanglement and codependency in the relationship between human and things also offers a framework for understanding the relationship between spectators and architecturally embedded paintings.102 Several historians of Byzantine art have productively expanded Otto Demus’s foundational thesis about the affective power of mural imagery in order to explore the performative and multisensorial dimensions of medieval church spaces.103 Staale Sinding-Larsen, Liz James, and Bissera Pentcheva have shown that the domed interiors of Byzantine churches were activated not only by means of the perspectival treatment and placement of images, but also through the dynamic interplay between spectators, portable objects, and the varied sounds and smells generated by liturgical rites.104 These interventions have demonstrated the value of approaching medieval spaces as dynamic scenarios that produce referential, symbolic, as well as non-representational forms of meaning through their interactions with human participants.105

The great hall at Santi Quattro Coronati was designed to elicit broad sensory engagement on the part of its spectators. The highly educated clerics for whom the frescoes were painted were required to move around the space while taking note of images located in different areas in order to establish meaningful links between them. Through this dynamic process, viewers became aware of their own roles as embodied spectators – that is, of how their combined cognitive and bodily engagement with the densely figured space activated latent levels of meaning. That the Santi Quattro Coronati painters wanted to call attention to the great hall’s particular viewing conditions is evident in their treatment of the illusionistic telamones occupying the vault springers. When observed from the floor level, these figures appear to wrap around the acute angles of the masonry groins. The sharp edges formed by the intersection of masonry surfaces seem to push out through the figures, highlighting the intrinsic relationship between painting and architecture in the fresco medium. The telamones’ appearance, however, also changes depending on one’s viewing position. When seen from one angle, a figure such as the acrobat next to the month of December appears stretched out by the angled masonry groin (Figure 1.33). Yet, when seen from a slightly different angle, the same figure no longer appears subject to its masonry support but rather negates its own architectural fixity. Hanging playfully on the painted red lattice while dangling his left leg into the viewer’s space, the figure draws us in and makes us momentarily forget the underlying surface of the wall. Likewise, the acrobat to the right of Emulatio Sancta makes viewers aware of their own bodily movements and physical contortions as they observe the paintings in Cardinal Conti’s hall (Figure 1.34). This acrobat strikes an unlikely pose by bending his body so far back that his head is upside down. The acrobat appears to poke fun at viewers observing from the floor level; his strangely warped posture is in many ways an exaggerated version of the pose they are required to assume in order to view the figure on the springer.

1.33. Fresco showing acrobatic figure (telamon), ca. 1244–54, south bay, Santi Quattro Coronati, Rome.

The interdependent relationship between viewers, frescoes, and architectural space is central to the great hall’s encyclopedic function as well as its capacity to generate knowledge beyond the level of base iconography. While we cannot know precisely how thirteenth-century visitors to Conti’s hall would have experienced its encyclopedic mural decorations, we can know that these historical individuals occupied human bodies that stood upright, faced the world in one direction at a time, and were endowed with the five senses and a basic appreciation of scale. We can therefore surmise that, like us, historical observers would have experienced the basic tension between the whole and its parts that is a central characteristic of the great hall at Santi Quattro Coronati. In all likelihood, thirteenth-century viewers would have experienced the way in which the walls and vaults create the effect of spatial enclosure, and how the stylistic uniformity and thematic coherence of the frescoes convey a sense of wholeness. Yet, at any given time, these viewers (again, like us) would have been able to focus their vision on only a relatively small part of the mural. In fact, assuming that the basic mechanics of vision have not significantly changed since the thirteenth century, everything more than five degrees beyond the point of focus would have been “felt” more than “seen” through what is sometimes called “ambient vision” – which is what enables us to be aware of our surroundings even if we can consciously observe only a small part at any given time.106 Within a frescoed space such as Conti’s great hall, the vast field sensed by ambient vision is always yet another part of the painting. Beyond vision, other human capacities, such as proprioception and memory, also play into the interpretive experience. As viewers move around within the space, new images continuously come into view while others vanish from their field of vision. All the while, proprioception, ambient vision, and memories of images just seen make it possible for spectators to remain aware of the fresco cycle as a whole even if they can see only one of its parts.

It is precisely this dynamic interplay between architectural space, paintings, and kinesthetic engagement that enabled the Santi Quattro Coronati frescoes to function as a visual encyclopedia. The mural’s capacity to thematize the relationship between the whole and its constituent parts was dependent on the presence of human viewers whose real physical limitations prevented them from ever seeing the whole. Furthermore, the fresco cycle’s interactive design meant that viewers were consciously aware of how their bodily movements within the space and their intellectual engagement with the paintings activated the monument’s encyclopedism. This tension between the seen part of the mural and its unseen, but nevertheless registered, remainder serves as a metaphor for the relationship between partial and complete knowledge. This relationship, which played out at the level of spectatorship, modeled the central tenet in medieval Christian epistemology regarding the contrast between the imperfect knowledge of humans and the perfect knowledge of God.107 Divine knowledge was all-encompassing and timeless. The divine gaze was like a disembodied eye that apprehended the world in its past, present, and future at once. By contrast, human knowledge was hampered by its temporal fixity and fleshly embodiment. The human gaze could apprehend only a segment of the wider world from the vantage point of the present moment. At Santi Quattro Coronati, this epistemic distinction was dramatized through the distinct interplay between pictorial decorations, architectural space, and the intellectual activity and physical movements of viewers.

The Santi Quattro Coronati paintings encouraged reflective viewing practices also at the level of individual images. The learned iconographies developed in Conti’s great hall did more than translate verbal knowledge into visual form; they also produced intellectual experiences in educated spectators. Examples of images that encouraged reflective viewing include the complex compositions of virtues and vices, which juxtapose allegorical figures and historical characters in unexpected ways. For instance, the composition featuring Sobriety overcoming Luxury on the north wall includes the Old Testament prophet Daniel seated on the virtue’s shoulder and the prophet Muhammad alongside the personified vice (Figure 1.35). Here, Luxury exhibits a scroll reading “COMMEDAMVS ET BIBAMVS” (Let us eat and drink), which at face value seems to be a relatively simple reference to indulgent behavior. The appearance of Muhammad next to Luxury can be seen as a reference to the Arabic world imagined as a realm of sensual delights. However, the highly educated viewers for whom the frescoes were painted would likely have recognized the phrase “Let us eat and drink” as a quote from Isaiah’s eschatological rumination about Jerusalem’s downfall at the hands of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar. They would likely also have seen the contrast drawn between Daniel and Muhammad as an invitation to reflect on the papacy’s use of eschatological tropes to cast the prophet of Islam as a precursor to the Antichrist. In fact, the citation from Isaiah 22 was probably meant to invoke Pope Innocent III’s 1213 circular announcing the Fifth Crusade, in which the Conti pontiff described Muhammad as the “Son of Perdition” who seduced people “through worldly enticements and carnal delights.” As such, the relatively abstruse quotation and the particular pairing of historical characters encouraged spectators to deploy exegetical forms of thinking and to recall knowledge from their memory in order to bring out latent meaning from the fresco.

Other images that encouraged reflective viewing include the ambiguous antiquities placed in the lunettes above the cycle of virtues and vices in the north bay (see Figures 3.29–3.32). These figures are among the only images in the great hall that are not identified by written labels, suggesting that they were designed to function as interpretively ambiguous motifs. Such figures required spectators to engage in open-ended thinking around the figures’ possible identities and their relation to the cycle of virtues and vices below. The exploratory mode of engagement reflected the positive view of significational ambiguity in medieval exegesis, wherein all manner of written, visual, and material works were understood as open to multiple interpretations. The paintings also appear to have drawn inspiration from the distinctly speculative interpretations generated by the real antique statues and architectural ruins that could be seen along the streets and in the piazzas of medieval Rome. Related forms of ambiguity appear throughout the cycle of liberal arts in the south bay lunettes, as I detail in Chapter 2. Here, each scene includes a personification of the art in question alongside an ancient progenitor of this art. Whereas the female personifications are easily identifiable by means of inscriptions and attributes, the male progenitors are unidentified. Such unidentified originators were meant to spur reflective viewing and intellectual discussion among the highly educated courtiers for whom the Quattro Coronati murals were painted. Members of the thirteenth-century papal court were more rigorously educated and were significantly more familiar with ancient and Islamic natural philosophy than their clerical predecessors. It was this rigorous training in the liberal arts and fascination with worldly knowledge that enabled papal courtiers to engage with Cardinal Conti’s frescoes in open-minded and exegetical ways.