1. Introduction

In countries such as Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands, the health care system is based upon the principles of managed competition. In these systems, health insurers are expected to act as prudent buyers of care on behalf of their enrolees. Enrolees are allowed to choose an insurer based on the insurer's ability to buy good quality health care at the lowest price possible. However, the Dutch experience indicates that overall consumer trust in health insurers is low and that consumers focus primarily on price when buying health insurance (Bes et al., Reference Bes, Wendel, Curfs, Groenewegen and de Jong2013; Groenewegen et al., Reference Groenewegen, Hansen and de Jong2019; Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2019). Hence, the important question arises if consumers really perceive and trust health insurers as prudent buyers of care. We address this question by using a mixed-method approach of focus groups and a survey. The Dutch situation provides an interesting setting for studying the purchasing role of insurers since the Netherlands is commonly perceived as a frontrunner in implementing managed competition in health care (Jeurissen and Maarse, Reference Jeurissen and Maarse2021).

The central aim of our study is to find out if consumers perceive and trust the health insurer as a prudent buyer of care. Our study contributes to the current literature by focusing specifically on consumer perceptions of private insurers' health care purchasing role in the context of managed competition. There are many previous studies that focus on consumer trust in health insurers. We will discuss these in section 2. However, the specific link between consumer trust and consumer perception of the purchasing role is included in only one previous study (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and de Jong2015). Yet a key feature of the managed competition model is that consumers choose an insurer based on their perception of the ability of this insurer to act in their interest as prudent buyer of care (Enthoven and Van de Ven, Reference Enthoven and Van de Ven2007). If consumers do not perceive health insurers to be prudent buyers of care and/or do not trust health insurers in this role, insurers will not be effectively motivated to act this way. Using recent data and a more sophisticated conceptual model of health insurers' purchasing role can contribute to improving health care systems with managed competition. Our study aims to do so and builds upon previous studies by updating, broadening and refining the insights available from the current literature.

2. Background

In the Dutch health system with managed competition, insurers are obliged to offer a legally defined standardised benefit package (basic health plan). They also must accept all applicants, irrespective of their health risk, at a community rated premium (i.e. insurers must charge the same premium for everyone with the same health plan). Insurers are free to contract health care providers selectively but have a legal ‘duty of care’, implying that they must ensure access to adequate, timely and sufficient care for their clients. To reduce incentives for risk selection, the government compensates health insurers ex-ante for the risk profiles of their customers through a risk equalisation system. On a separate market, consumers can also buy supplementary insurances to cover health care that is not covered by the basic health plan, primarily consisting of physical therapy and dental care for adults. Buying a basic health plan is mandatory for consumers whilst buying supplementary insurance is voluntary.

In 2022, there were 20 risk bearing health insurers in the Dutch insurance market, which were part of 10 independent insurance concerns. The four largest concerns had a joint market share of about 85 per cent. All four large concerns and most other insurers find their roots in former sickness funds, are not-for-profit and organised as cooperatives (Kroneman et al., Reference Kroneman, Boerma, van den Berg, Groenewegen, de Jong and van Ginneken2016). For most insurers their ‘social mission’ – the moral obligation to act upon the public goals of the system – is an important driver (Stolper et al., Reference Stolper, Boonen, Schut and Varkevisser2019). At the same time, insurers cannot ignore the financial incentives within the system. Even though the Dutch system of risk equalisation is generally considered to be one of the most sophisticated in the world, evidence shows that to some extent it is still profitable for insurers to attract healthy people and unprofitable to attract unhealthy people (Croes et al., Reference Croes, Katona, Mikkers and Shestalova2018; Van Kleef et al., Reference Van Kleef, Van Vliet, Eijkenaar and Van de Ven2019; McGuire et al., Reference McGuire, Schillo and van Kleef2020; Stolper et al., Reference Stolper, Boonen, Schut and Varkevisser2022).

Once a year, during the ‘switching season’ (a fixed, 6-week open enrolment period at the end of the year) consumers are free to switch between insurers (Minister of Health, 2004). The percentage of customers that switches between insurers has been stable for years, averaging between 6 and 8 per cent (Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit (NZa), 2021). Younger people switch considerably more than older people. Switching behaviour is primarily motivated by price and, to a much lesser extent, by the coverage of supplementary insurance. Quality of contracted care is not a factor of significance in a consumer's choice of a health insurer (Holst et al., Reference Holst, Brabers and de Jong2021). Exact information on which providers are contracted by the health insurers is often unavailable during the switching season since negotiations between insurers and providers tend to carry on until the end of the switching season or even later. Moreover, consumers with lower education or a lower income are more likely to have a low ‘health insurance literacy’, implying that they are more likely to have difficulty choosing and using a health insurance policy (Holst et al., Reference Holst, Rademakers, Brabers and de Jong2022).

From the literature it follows that the overall trust of consumers in health insurers is low. Maarse and Jeurissen (Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2019) provide a comprehensive overview of these studies and suggest that the lack of trust is institutional – i.e. something insurers have to live with. Explanations range from a lack of information, a negative attitude towards competition in health care and resistance to interference in the patient/physician relation. Additionally, the perception that health insurers have commercial goals and therefore face a conflict of interest between making a profit and providing good care also plays a role (Bes et al., Reference Bes, Wendel and de Jong2012; Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and de Jong2015). Trust in health insurers is considerably lower than trust in health care providers. Whereas in 2022 92 per cent of the Dutch population trust GPs and 77 per cent have trust in hospitals, only 26 per cent expressed that they trust health insurers (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and de Jong2015; Meijer et al., Reference Meijer, Brabers and de Jong2022). Furthermore, people's trust in their own health insurer is slightly higher than in other health insurers (van der Hulst et al., Reference van der Hulst, Brabers and de Jong2023). Various studies made clear that the lack of trust hampers the role of health insurers to act as purchasers of care and therefore is one of the reasons why Dutch health insurers are hesitant to engage in selective contracting (Boonen and Schut, Reference Boonen and Schut2011; Groenewegen et al., Reference Groenewegen, Hansen and de Jong2019; Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2019; Jeurissen and Maarse, Reference Jeurissen and Maarse2021).

3. Methods

3.1 Overall study design

Our study used a mixed-methods approach, beginning with focus groups and followed by a survey, to investigate whether consumers perceive and trust a health insurer as a prudent buyer of care and to examine which factors are associated with perception and trust levels. We chose this approach considering the challenging nature of the research topic, i.e. health insurance is a low interest product for consumers and consumer knowledge of the concepts that we intended to measure could be limited. We used the focus groups to explore the key concepts and deepen our insight in consumers understanding of the subject matter. The combination of the qualitative data gathered from the focus groups and the available literature were instrumental in crafting the survey questions, helping us to formulate the right questions and thereby enhance the validity of the survey instrument. The survey allowed us to quantify the prevalence of our focus group findings across a larger and more representative sample. Furthermore, based on the survey data we constructed two latent variables about perception of and trust in the purchasing role of health insurers and performed a regression analysis to examine which factors are associated with the constructed perception and trust levels.

3.2 Focus groups

In contrast to previous studies, our research focussed specifically on the purchasing role of health insurers. To do so, it was essential to explore how we could conceptualise the purchasing role in a for consumers understandable way. Therefore, we organised two different focus groups with Dutch consumers. We chose for two groups because we wanted to be able to compare the results. Through these focus groups we could establish a preliminary, conceptual understanding of what consumers know about the purchasing role of health insurers and about the level of trust they have in this role. We shared an open invitation for both focus groups on various platforms and used our personal networks to recruit participants. We accepted all applications from Dutch adults with health insurance until the intended number of participants (between 6 and 10 people per focus group) was reached. The set-up of the focus groups was semi-structured, and the sessions lasted around 1.5 hours. Two of us moderated the sessions using a topic guide (see Appendix A) and one researcher was present as an observer.

We used the ‘thematic network approach’ to analyse the data of the focus groups (Attride-Stirling, Reference Attride-Stirling2001). Both sessions were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Using ATLAS.ti as research software, two members of our team coded the transcripts. To avoid bias and establish inter-coder reliability, all data were coded twice and differences in coding were discussed until a consensus was reached. Codes were clustered into broad categories that emerged from the data. Through interpretation of the themes within these categories and subsequent group discussion in our team, we identified the most relevant insights within the qualitative data.

The insights of the focus groups allowed us to formulate tentative conclusions about how consumers perceive the insurers' purchasing role and whether they trust insurers in performing this role. They also enhanced our insight in consumer understanding of basic concepts such as the purchasing role of insurers in general and the government's role in determining the benefits covered by the basic health plan. Furthermore, the focus group discussions made clear how the use of concrete examples can enhance consumer comprehension of insurers' role as health care purchasers.

3.3 Survey

Based on the insights from the focus groups and the literature, we designed an online survey with multiple choice and Likert scale questions (see Appendix B). In April 2022, we issued the survey to a large panel representative for the general Dutch adult population managed by a professional market research bureau (Kantar). For participation in this panel, Kantar approached and selected the individuals, ensuring maximum representation of the general Dutch population based on age, sex, education level, and region. The duration of the survey was around 10–15 minutes, and most questions were closed. Before sending out the survey to this panel, we tested it among a small number of persons to ensure that all questions were unambiguous.

We identified 12 different purchasing tasks of health insurers from the statutory duties of health insurers (as described in the Dutch Health Insurance Act), the existing literature and policy documents, as well as from expert judgement of the authors (see Box 1). For each of these tasks, we asked respondents whether they were familiar with these purchasing tasks, whether they perceived these tasks as an appropriate part of the purchasing role, and to what extent they trusted insurers with these tasks. In addition, we asked respondents whether they would take these tasks into account when choosing a health insurer.

Box 1. The 12 purchasing tasks

1. Purchase care and medicines for a low price

2. Purchase care and medicines of good quality

3. Set criteria for quality of care that providers supply

4. Inform policyholders about price and quality of the purchased care

5. Determine the care needs of the policyholder population

6. Determine from which providers services are (not) fully reimbursed

7. Ensure that enough care is available on time

8. Ensure that care is available in the area

9. Take into account policyholder preferences

10. Stimulating prevention in health care (e.g., quitting smoking)

11. Take research and developments about evidence-based medicine into account

12. Play a role in the concentration of highly specialised care in fewer hospitals

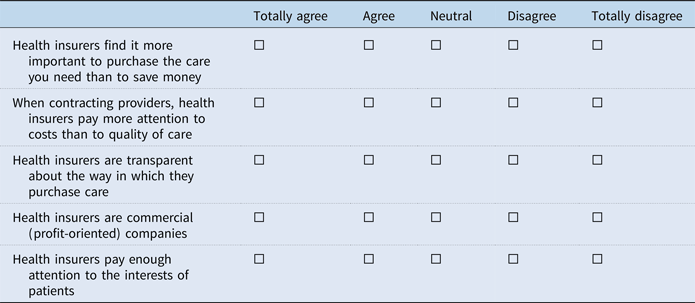

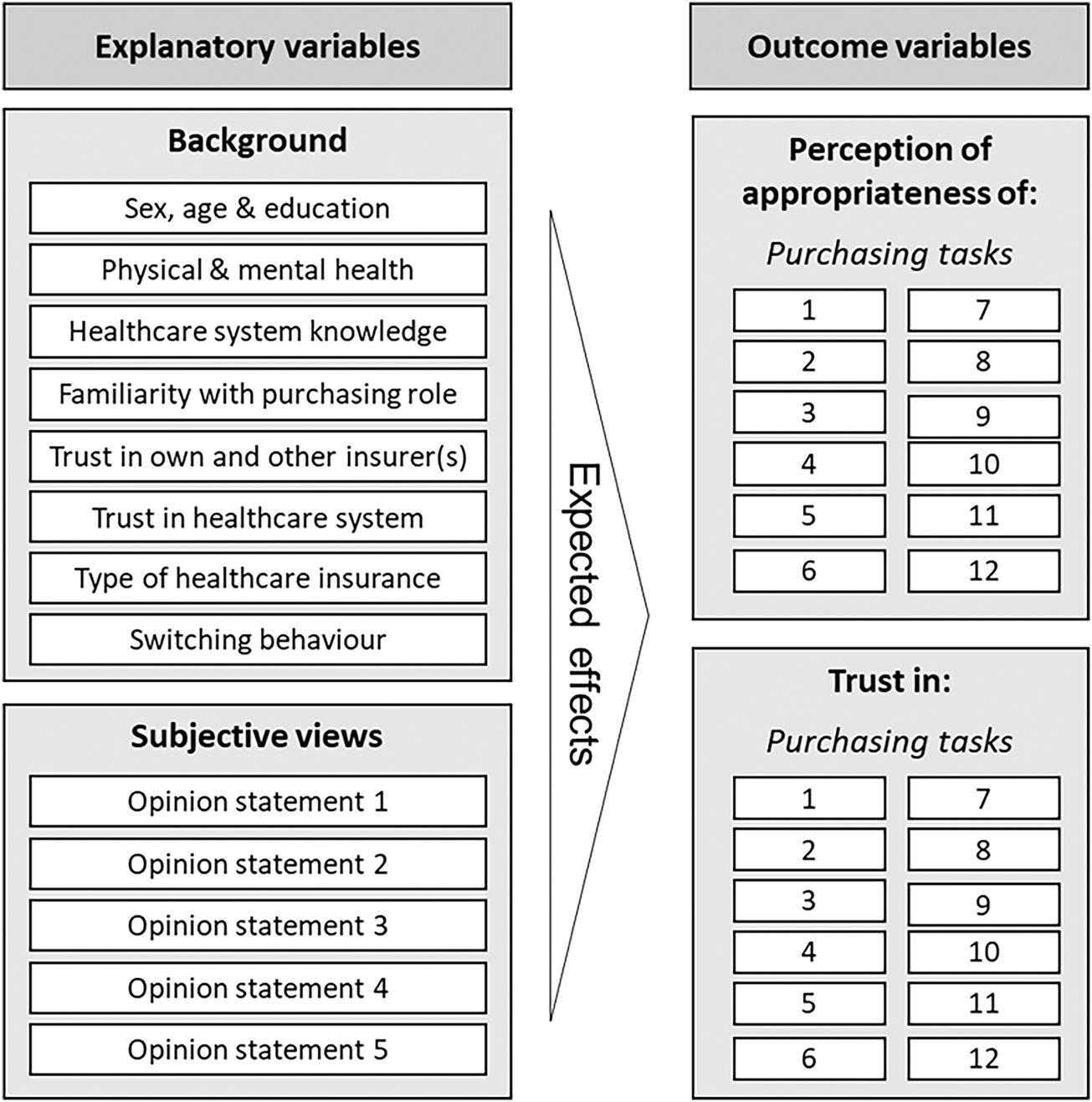

Next, we asked respondents about possible drivers of trust in and perception of the purchasing role of health insurers, which we derived from the focus group results and the literature (see Appendix C for an overview). Specifically, in addition to some general background characteristics (age, level of education), we asked respondents about their physical health, mental health as well as knowledge and familiarity of the health care system because these variables are likely to be related to their perception of and trust in the purchasing role of health insurers (Goold and Klipp, Reference Goold and Klipp2002; Balkrishnan et al., Reference Balkrishnan, Dugan, Camacho and Hall2003; Balkrishnan et al., Reference Balkrishnan, Hall, Blackwelder and Bradley2004; Goold et al., Reference Goold, Fessler and Moyer2006). For the same reason we included questions about the level of trust in one's own health insurer, health care professionals or the health care system as a whole and the satisfaction with their current health insurer (Balkrishnan et al., Reference Balkrishnan, Dugan, Camacho and Hall2003; Goold et al., Reference Goold, Fessler and Moyer2006; Bes et al., Reference Bes, Wendel, Curfs, Groenewegen and de Jong2013; Gabay and Moore, Reference Gabay and Moore2015; Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2019). Finally, we added five opinion statements in order to assess individuals' subjective views about the purchasing role. By including these statements, we aimed to measure underlying beliefs about health insurers (e.g., whether they were believed to be transparent and serving patients' interests) to deepen our insight into the root causes of specific perceptions and generally low trust levels in insurers. See Box 2 for the five opinion statements and Box 3 for a conceptual model of the explanatory variables and outcome variables.

Box 2. The five opinion statements

1. Health insurers find it more important to purchase the care you need than to save money

2. When contracting providers, health insurers pay more attention to costs than to quality of care

3. Health insurers are transparent about the way in which they purchase care

4. Health insurers are commercial (profit-oriented) companies

5. Health insurers pay enough attention to the interests of patients

Box 3. Conceptual model of explanatory variables and outcome variables

3.4 Regression analysis

The survey data were analysed using both descriptive statistics and multiple linear regression analysis. For the regression analyses, we constructed two latent outcome variables to measure respondents ‘perception of the purchasing role’ and ‘trust in the purchasing role’ based on their answers to the survey questions about the perceived appropriateness of, and trust in insurers performing the 12 identified purchasing tasks. Both variables consisted of the answers to questions concerning the 12 purchasing tasks of insurers. For ‘perception’, respondents were asked to indicate on a five-point scale (ranging from 0 to 4) for each of the 12 purchasing tasks to what extent they think this task fits the purchasing role of a health insurer. We measured the results per task separately and – after combining ‘totally agree’ and ‘agree’ as well as ‘disagree’ and ‘totally disagree’ into two joint answer categories – took the sum of the scores per respondent as outcome variable. Likewise, for ‘trust’, we measured the level of trust of respondents on a five-point scale for each of the 12 purchasing tasks and – after combining ‘very much’ and ‘much’ as well as ‘little’ and ‘totally disagree’ into two joint answer categories – took the sum of scores as outcome variable. Respondents who answered ‘don't know’ to questions about trust in some of the purchasing tasks were assumed as having ‘no trust’ in these specific tasks, i.e. these answers were coded as zero. Since the number of responses for which this applies is small, this assumption does not affect our results. In addition, 32 respondents (5 per cent) reporting that they did not know having trust in any of the 12 purchasing tasks were excluded from the regression analysis because their level of trust could not be interpreted. This clearly is an outlier group, since almost all other respondents answered most or all of the questions about trust (see Table 2 below).

Using factor analysis, we tested both the construct validity and internal consistency (or reliability) of both outcome variables (factors). We found that all items load highly on both factors (almost all factor loadings exceeding 0.45), confirming the construct validity of the scales (see Appendix D). Hence, both scales accurately reflect the construct they are intended to measure. In addition, for both construct variables we found high Cronbach's alpha values (0.86 and 0.97 for perception and trust, respectively) indicating that response values for each respondent across the 12 task items are consistent.

All explanatory variables were derived from the survey questions and are either dichotomous or measured on a scale ranging from three to six points. Physical health and mental health are self-assessed and measured on a five-point scale (Doiron et al., Reference Doiron, Fiebig, Johar and Suziedelyte2015). Health care system knowledge is measured based on five true or false statements about the Dutch health care system and set up as a composite variable consisting of the total number of correct answers to the statements. For the variables ‘familiarity with purchasing role’ and ‘importance of purchasing role in choice behaviour’, respondents were asked to indicate on a three- and five-point scale, respectively, for each of the 12 purchasing tasks if they are (somewhat) familiar or unfamiliar with the purchasing tasks and to what extent the purchasing role could play an important role in their choice behaviour. The mean of the scores for all the 12 purchasing tasks together was taken to measure mean familiarity and mean importance of the purchasing role. Note that the latter variable is not included in the regression models but is only used for descriptive statistics. Furthermore, to properly build the regression models, several of the explanatory variables were recoded to merge small answer categories.

In our final regression models, we only included those explanatory variables that added predictive power (see Table 4). To select these variables, we used hierarchical regression analysis. To take into account multicollinearity between explanatory variables and possible overlap with outcome variables, correlation analysis was used on the entire dataset to measure the degree of association between variables.

3.5 Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in both the focus groups and the survey. Participants were provided with detailed information regarding the purpose, procedures, and potential risks and benefits of their participation. They were assured of confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence. Only those who provided explicit consent proceeded to participate in the research activities.

4. Results

4.1 Focus groups results

In total, 16 consumers participated in our focus groups, distributed evenly amongst the two groups. Participants were aged between 25 and 74, were slightly higher educated than average and varied qua intensity of care use. In what follows, we describe the results of both focus groups together since there was no notable difference in results between the two groups.

In general, participants indicated that they considered the purchasing role of insurers a difficult topic to discuss. Participants sometimes needed a little help from the moderators to understand the subject matter. After some additional explanation, participants were more or less able to formulate what they expected the purchasing role of health insurers to be. Sometimes, these expectations were in accordance with the actual purchasing tasks that health insurers have. In other instances, participants appeared to have expectations of the purchasing tasks that did not align with reality (e.g., determining the benefits to be covered by the basic health plan).

Unfamiliarity with the purchasing role was a central theme in the focus groups. Most participants were aware that insurers purchase health care but indicated having a limited notion of what the purchasing role encompasses. They also made clear that they have insufficient information to assess whether health insurers are adequate (i.e. able to meet customer preferences) in performing their role as a purchaser of care.

Various participants proactively indicated that a lack of transparency about how insurers purchase care hinders them to form an informed opinion about the effectiveness of the purchasing role. Because of this, participants found themselves unable to say if insurers could be trusted in their purchasing role, and neither could they incorporate this aspect into their choice behaviour even though some participants indicated that they would be willing to do so. Finally, several participants mentioned that they perceived (financial) conflicts of interest between insurers and insured and therefore doubted whether insurers always would act in the best interest of their enrolees.

4.2 Survey results

In total, 708 participants responded to our survey, constituting a response rate of 45 per cent. Compared to the general Dutch population the sample has a representative distribution on sex, age, and physical health. The sample has a slightly lower share of people with low education, a lower share of people with a poor or fair self-reported mental health and a higher share of people who switched between health insurers in 2021 (see Appendix C).

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the composite outcome variables on perception and trust.

Table 1. Descriptives of regression models' outcome variables (n = 708)a

a Respondents who answered ‘don't know’ to some questions about trust in the various purchasing tasks were assumed as having ‘no trust’ in these specific tasks, i.e. these answers were coded as zero; 32 respondents answering ‘do not know’ to all statements were excluded from the regression analysis and from calculating the mean and SD of the trust variable (these figures are based on n = 676).

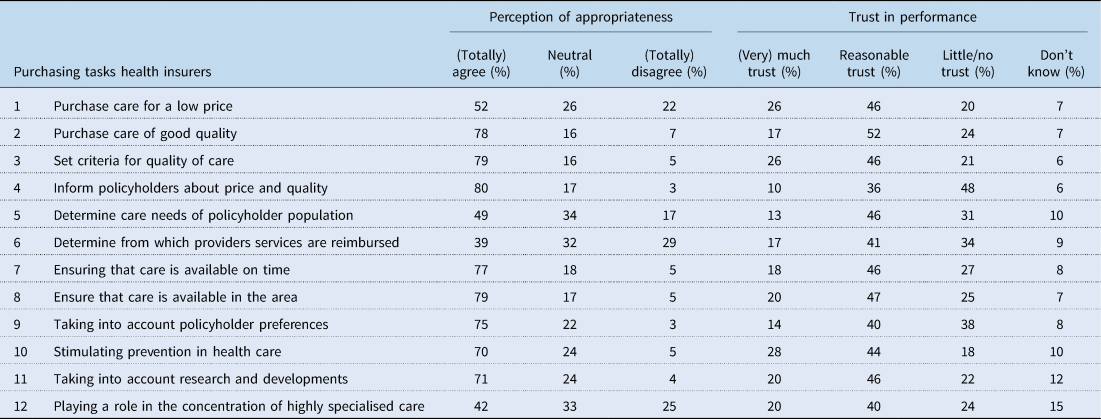

As shown, on average trust in the listed purchasing tasks is lower than the perceived appropriateness of these tasks. Whereas 66 per cent of the respondents (taking the average score across the 12 tasks) perceived these tasks as appropriate to the purchasing role, only a minority of the respondents has (very) much trust in insurers acting as purchasers on their behalf (on average 19 per cent across all purchasing tasks), while a considerable minority (28 per cent) responds having little to no trust in this role. The largest group (44 per cent) reports having reasonable trust, suggesting that their trust in this role may be fragile.

In Table 2 for both composite outcome variables the survey responses per task for the various answer categories are specified. Respondents report the lowest agreement about the appropriateness of the purchasing tasks ‘determining from which providers care is reimbursed’ and ‘playing a role in care concentration’. Still, these purchasing tasks load quite highly on the perception variable (see Appendix D).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of perception of appropriateness and in trust in performance of 12 purchasing tasks (n = 708)

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics of the explanatory variables. Interestingly, almost all respondents (94 per cent) are (somewhat) aware that health insurers purchase health care on behalf of their enrolees. When confronted with the 12 purchasing tasks, 72 per cent of the respondents (taking the average score across the 12 tasks) indicated being (somewhat) familiar with these tasks. The general trust in insurers of our sample is relatively high as 62 per cent of the respondents has reasonable to (very) much trust compared to the literature discussed in section 2 (Hoefman et al., Reference Hoefman, Brabers and de Jong2015; Meijer et al., Reference Meijer, Brabers and de Jong2022). This difference may be due to the fact that the answer category ‘reasonable’ was not an option in the survey of the study we referred to, which only included the categories ‘(very) much’, ‘(very) little’ and ‘no opinion’.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of explanatory and separate variables (n = 708)

An important result, in line with the results of the focus groups, is that only few respondents (8 per cent) agree that insurers are transparent about the way they purchase care (opinion statement 3). Most of the respondents (57 per cent) (totally) disagree with this statement. Another important finding that confirms findings from the focus groups is that a large majority (69 per cent) thinks that Dutch health insurers are commercial, profit-driven organisations, while almost all health insurers are not-for-profit entities (opinion statement 4). Finally, a notable finding is that 62 per cent of the respondents indicate that the purchasing role could be an important factor when choosing a health insurer (which is positively correlated with age and trust).

4.3 Results regression analysis

Table 4 presents the results of our regression models. The results of the first model, about the perception of the purchasing role, show that agreeing with opinion statement 1 (believing that for insurers buying the care you need is more important than saving costs) is associated with a higher likelihood of perceiving the purchasing tasks of insurers as appropriate. As expected, a positive perception of the appropriateness of the purchasing role of insurers is associated with a higher level of trust in this role. In addition, older people (aged over 55 years) clearly have a more positive perception of the purchasing role of insurers than younger people. The results of the second model show that those who trust insurers in general and those who think that insurers pay enough attention to consumers' interests are also more likely to have trust in insurers' purchasing role. Furthermore, we found that people who believe that health insurers are transparent about how they purchase care (opinion statement 3) have more knowledge about the health care system in general and are more familiar with the purchasing tasks, ceteris paribus have more trust in the purchasing role of the insurer. These findings suggest that being well-informed about the way insurers purchase care is constitutive for trust in the purchasing role of insurers. We also found that being female and having switched insurers every year during the past 5 years is negatively associated with having trust in the purchasing role of insurers. Finally, people with good or excellent physical health also are found to have more trust in insurers' purchasing role.

Table 4. Results of regression models 1 and 2

Note. ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1. SE = standard error.

a Similar effects were found for the variables regarding trust in one's own health insurer and trust in the health care system as to trust in health insurers in general. Due to multicollinearity, these variables were estimated in separate models.

b A single hyphen (-) means that this variable was not taken into account as an explanatory variable.

c 32 observations were removed from the full sample concerning respondents answering ‘do not know’ for trust with regard to all 12 purchasing tasks, making their level of trust in the purchasing role uninterpretable.

5. Discussion

In the Dutch health care system, insurers are expected to act as prudent buyers of care. That is, they should buy good quality health care at the lowest price possible on behalf of their customers. In reality, however, overall trust in insurers is low and quality of care does not play a significant role when consumers buy health plans (Maarse and Jeurissen, Reference Maarse and Jeurissen2019; Holst et al., Reference Holst, Brabers and de Jong2021). The aim of our study was to find out if consumers perceive and trust the health insurers as prudent buyers of care. If this would not be the case, a key element of the health care system – being the idea that consumers ‘vote with their feet’ by choosing the insurer that in their eyes is most able to act as their purchasing agent – will not work as it was designed to work.

When it comes to perception, the findings from both our focus groups and the survey show that most people do in fact know that insurers buy health care on their behalf. Additionally, the survey showed that most people, when confronted with a list of potential purchasing tasks, feel that most of these tasks suit the role of health insurers and even have reasonable trust in the purchasing competencies of the insurer, although this trust seems to be fragile. Moreover, our survey results made clear that consumers are in principle inclined to incorporate how insurers fulfil this purchasing role in their health plan choice which is an important precondition for the managed competition to function as intended and makes studying perception of and trust in the purchasing role even more relevant.

However, the results of the focus groups and the survey also revealed that consumers report insufficient information about the content and merits of the purchasing role of health insurers. Most of the participants in both the focus groups and the survey indicate that health insurers are not transparent about the way they purchase care. We know from the focus groups that because of this lack of information consumers are not able to cast a judgement about the capabilities and success of health insurers as purchasers of care. Additionally, many respondents believe health insurers to be commercial profit-driven organisations. As we learned from the focus groups, in the eyes of consumers this constitutes a potential conflict of interest for the insurer while purchasing care.

Hence, a lack of transparency and a perceived conflict of interest seem to be the biggest obstacles for insurers to function as prudent buyers of health care. This conclusion is strengthened by our findings that both (i) being better informed about the Dutch health care system in general and the purchasing role of insurers specifically and (ii) having confidence that the insurer acts in the interest of consumers correlate positively with trust in the purchasing role of insurers.

At first glance, the implications of our findings are straightforward. For policymakers and health insurers, our conclusions should be a motivation to improve transparency on how the insurers' purchasing role is fulfilled. This means first and foremost that consumers should be able to understand the implications of the choices that insurers make as purchasers of care. At the beginning of the open enrolment period – i.e. the time window in December–January when people can switch health plans – it should be clear which providers are contracted, what agreements are made between the insurer and the provider and which additional benefits the insurer as the purchaser of care has to offer to its enrolees. Secondly, it should be easier for consumers to (1) critically assess the quality of health care contracted by the insurers and (2) compare it to the quality of contracted care of competing offers. To achieve the former, insurers and providers need to find a way to provide clarity on the outcome of their negotiations before the switching season starts. And insurers and intermediaries (e.g., comparison websites) need to translate this outcome in a consumers’ comprehensible and accessible way. To achieve the latter, it is of crucial importance to improve the publicly available information on the quality of health care. Health insurers, health care providers and policymakers should join hands to create access to understandable and reliable quality indicators. These indicators should support consumers when choosing a health plan and give insight into the consequences of choosing one insurer rather than the other. Additionally, insurers could explain better to the public that they have a social mission and are mostly organised as not-for-profit cooperatives. If insurers collaborate to convince the public that they are dedicated to the public goals of the health care system, including its financial sustainability, the prevalence of the (mis)perception that there is a conflict of interest could possibly be diminished.

When doing all the above, policy makers and insurers should be aware of the needs of groups with low health literacy skills. These groups will find it difficult to find, interpret and apply (digital) information. The solution, it seems, is not to provide more information but to provide better information and explore new, possibly non-digital, ways to reach out to these individuals.

At a second glance, the solution to our finding that consumers find themselves unable to cast a judgement about the merits of the health insurer as the purchaser of care is less obvious. It could be argued that no amount of information will ever enable all consumers to truly evaluate the complicated role of the insurer as a purchaser of health care. There is an inherent complexity in the system that makes it very difficult for consumers to assess the merits of health care procurement, especially for consumers with low health insurance literacy skills. This complexity is manifest in many of the aspects of the purchasing tasks but is most visible in the intrinsically challenging concept of quality of health care. Quality of health care has many dimensions, varying from the quality of the clinical process to the medical outcome and patient satisfaction with the treatment. It is profoundly difficult to measure all these dimensions adequately and bring together the information about these dimensions in a consumers’ understandable and accessible way. Let alone bring together all the information on these different dimensions for all the different sorts of care (hospital care, mental care, etc.) that have been contracted by an insurer for a specific health plan. The Dutch progress in creating comparable quality indicators at the provider level is encouraging (primarily at the hospital level) but this information is still fragmented and cannot be translated into reliable and comprehensible composite quality indicators at the health plan level measuring the quality of the contracted provider network and procurement arrangements (Barros et al., Reference Barros, Brouwer, Thomson and Varkevisser2016; Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit (NZa), 2017).

Another inherent difficulty to support public trust in the purchasing role of insurers is that insurers must monitor health care costs and efficiency to keep premiums affordable, while individual patients do not experience the marginal cost of health care consumption due to low co-payments. Hence, for patients there are concentrated benefits but diffused costs. This implies that for an individual patient, the trade-off between (high) marginal benefits and (low) marginal cost is different than for insurers who experience high marginal costs and limited marginal benefits (especially when the risk equalisation system does not adequately compensate for chronically ill patients). Hence, some of the purchasing decisions that health insurers make will be beneficial for the common interest of all enrolees (or even for the health care sector in general) but disadvantageous for the specific interests of individual patients. This tension can be eased by better information about the purchasing role and the quality of care that is purchased and by improving risk equalisation but can never be fully solved.

For policymakers and health insurers, these inherent complications imply that the current situation, in which consumers are not able to fully apprehend the merits of insurers' purchasing role, should be considered (semi) permanent for at least the near future. That means that consumers evaluating health insurers mainly on price and thereby incentivising insurers to focus on health care spending is to be considered as a given for the coming years. This requires additional measures from policymakers to ensure that health insurers will take integral purchasing responsibility and give more consideration to the quality and accessibility of health care. For insurers, these insights require continuously searching for a delicate balance between their broad social mission on the one hand and market incentives to focus solely on cost containment on the other. Intensified collaboration among health insurers aimed at improving quality of health care without engaging in anticompetitive practices therefore seems desirable.

The authors acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, we recognise the potential for selection bias in the focus groups, although this was mitigated through conscious participant selection. In addition, slight differences between the demographic composition of the survey sample and the broader Dutch population might also have biased our results, although we believe these variations are unlikely to substantially alter our findings about consumer perceptions and trust in the purchasing role of health insurers. Moreover, variations in people's experiences with health insurers may affect their perception of and trust in the purchasing role of health insurers. Although, we have included several proxies to account for these differences we cannot rule out the possibility that these differences may have affected our results.

The strength of our study is the combination of qualitative and quantitative research and the specific focus on the purchasing role of the health insurers. This allowed us to reveal that most consumers are aware of the purchasing role of health insurers and have reasonable, though fragile, trust in it. They are even inclined to incorporate this in their switching behaviour but have insufficient information to cast a judgement about it.

Overall, from our study it follows that organising a systematic, consistent and intensive long-term collaborative effort by all relevant parties to improve transparency on the role and performance of insurers as purchasers of care is crucially important for improving consumers' trust and the performance of this purchasing role by insurers. The findings presented in this paper are not only relevant for the Dutch health care system but also for many other countries, such as Germany, Israel, and Switzerland, relying on consumer choice to incentivise competing third-party payers to act as prudent purchasers of care.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to declare.

Financial support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

Karel C. F. Stolper was employed at CZ Groep at the time of the study. This research, however, was conducted independently outside the employment of CZ Groep but with their consent

Appendix A

Focus group topic guide

1. Welcome

• Digital walk-in 10 minutes before the start of the focus group.

• Start recording.

2. Introduction focus group

• Agenda focus group.

• Purpose of the focus group.

• Background information focus group.

• Personal introduction of participants

Individual opening question 1: Who are you and what do you think is the job of the health insurer?

Individual opening question 2: Were you previously familiar with the purchasing role of health insurers?

3. Start of group conversation

Question 1: What do you understand by the purchasing role of health insurers?

Various keywords of the input given by participants are written on an online white board and shared with the group if necessary to guide the conversation.

Guiding questions:

• What does the purchasing role entail according to the participants? Which aspects are important?

• According to policyholders, what is important about health care purchasing and do they see this in practice?

◦ Do the other participants agree?

• Do the participants find the following aspects (important) parts of the purchasing role? Back-up question if people do not mention certain aspects (from literature/research) at all.

◦ Ensuring that the quality of the purchased care is high

◦ Ensuring that care is purchased at a reasonable price

◦ Purchasing according to the preferences of policyholders – taking into account the composition of the insured population

◦ Selective contracting – for example, they do not contract all hospitals but only a limited number

◦ Include waiting times in health care purchasing

◦ Waiting list mediation

• Do the participants see the health insurer as the right person to fulfil the purchasing role? Why or why not?

• According to the participants, is there another (better) party that could take on health care procurement? Why?

Question 2: How much trust do you have in the purchasing role of health insurers?

Guiding questions:

• Do you have trust in institutions in general? E.g. banks, pension funds, government?

• Do you have trust in health insurers in general?

• Do you have trust in your own health insurer?

• Do you have trust in the health insurer as a health care purchaser? Alternatively: how much trust do you have that you will receive the care you need?

Aspects of purchasing role that have been brought forward by participants are presented on a whiteboard.

• In which aspects of the purchasing role do you have trust or no trust?

• What determines the degree of trust that the participants have?

• Does your opinion change when we talk about your own health insurer?

Question 3: Did the way in which the health insurer purchases health care play a role in your choice of a health insurer?

Guiding questions:

• Is the purchasing role something you take into account when you choose a health insurer?

• Did (the trust in) the purchasing role play a role in the choice of the (current) insurer?

• How do you take it into account?

4. End of group conversation

Optional closing questions: How could trust be increased? How could the health insurer fulfil the purchasing role better/differently?

• Drawing general conclusions with the entire group.

• Are there any comments/additions?

• How did the participants experience the group conversation?

Appendix B

Survey

Introduction

Dear Sir or Madam,

Thank you for participating in this study.

This research aims to gain insight into your expectations about how the health insurer purchases care for you and the trust you have in this purchasing role. This helps us to better understand the point of view of policyholders in the Netherlands.

Completing the questionnaire takes about 12 minutes. You decide whether you want to participate in this study and can, if you wish, terminate your participation at any time. Your data is handled reliably and the results are processed anonymously.

1: Questions about health insurance characteristics

In the next section we ask you questions about your health insurer and insurance.

1. With which health insurer are you currently insured?

◦ a.s.r.

◦ Aeviate (Eucare)

◦ Anderzorg

◦ Besured

◦ Bewuzt

◦ CZ

◦ CZdirect

◦ De Friesland Zorgverzekeraar

◦ Ditzo

◦ DSW

◦ FBTO

◦ Hema

◦ Interpolis

◦ inTwente

◦ IZA

◦ IZZ

◦ Jaaah

◦ Just

◦ Menzis

◦ Nationale-Nederlanden

◦ OHRA

◦ ONVZ

◦ PMA

◦ PNOzorg

◦ Promovendum

◦ Pro Life

◦ Salland

◦ Stad Holland

◦ UMC

◦ United Consumers VGZ

◦ Univé

◦ VGZ

◦ VinkVink

◦ VvAA

◦ ZEKUR

◦ ZieZo

◦ Zilveren Kruis

◦ Zorg en Zekerheid

◦ Zorgdirect

◦ I don't know

2. What type of policy do you have with your current health insurer?

◦ Restitution policy

◦ In-kind policy

◦ Combination policy

◦ I don't know

3. Are you participating in a group contract (for example through your employer, sports club or trade union)?

◦ Yes

◦ No

◦ I don't know

4. Do you have a supplementary health insurance in addition to your basic insurance?

◦ Yes

◦ No

◦ I don't know

5. Have you opted for a voluntary deductible?

◦ Yes

◦ No

◦ I don't know

6. How satisfied are you with your current health insurer?

◦ Very satisfied

◦ Satisfied

◦ Neutral

◦ Dissatisfied

◦ Very dissatisfied

7. Have you ever had a problem with your health insurer?

◦ No, never

◦ Yes, about the service provision

◦ Yes, about the reimbursement of care

◦ Yes, about something else; namely… [insert open field]

2: Questions about health insurance knowledge and opinion statements

In this section we ask what you know about the role of health insurers.

1. Are you aware that health insurers purchase care on behalf of their policyholders (i.e. make agreements with health care providers about the care to be provided)?

◦ I'm aware of that.

◦ I'm somewhat aware of that.

◦ I'm not aware of that.

2. Can you indicate to what extent you are aware that the following tasks are part of the purchasing role of health insurers?

3. Can you indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements?

4. Can you indicate whether you think the following statements are true or not?

3: Questions about trust in general

In this section we ask you questions about your trust in different organisations and individuals.

4: Questions about the purchasing role and trust in this

Since the introduction of the Health Insurance Act in the Netherlands, health insurers have been given the legal task of purchasing care for their policyholders. This means that health insurers make agreements with health care providers such as hospitals and general practitioners about the price, quality and quantity of care. Health insurers can also choose to offer no contract to certain health care providers.

In the next section we will ask questions about how you as a policyholder view this purchasing role of health insurers and whether you trust the health insurer in this.

1. To what extent do you agree that the following tasks fit the purchasing role of health insurers?

2. Are there any other tasks that you think belong to the purchasing role of health insurers?

◦ Yes, namely … [insert open field]

◦ No

3. Do you think the health insurer is the right party to purchase the care?

◦ Yes (go to question 5a)

◦ No (go to question 4 and then to 5b)

◦ I don't know (go to question 6)

4. If question 3 = No; Which party do you think is more suitable for purchasing care?

◦ Government

◦ Health care providers (e.g. doctors, pharmacists)

◦ Employer

◦ The patients themselves

◦ I don't know

◦ Otherwise, namely … [insert open field]

5. a: If question 3 = Yes; What is the main reason why you think the health insurer is the right party to buy care?

◦ Because of my experiences with health insurers

◦ Because of the objective that I think health insurers have

◦ Because of the tasks that health insurers have

◦ Because of the interests of health insurers

◦ Because of the expertise of health insurers on health care procurement

◦ Because of the transparency of health insurers about the agreements they make with health care providers

◦ Otherwise, namely … [insert open field]

5b: What is the main reason why you feel that the health insurer is not the right party to buy care?

◦ Because of my experiences with health insurers

◦ Because of the objective that I think health insurers have

◦ Because of the tasks that health insurers have

◦ Because of the conflicting interests of health insurers

◦ Due to the lack of expertise of health insurers on health care procurement

◦ Due to the lack of transparency of health insurers about the agreements they make with health care providers

◦ Otherwise, namely … [insert open field]

6. How much trust do you have in health insurers carrying out the purchasing tasks properly?

5: Questions on consumer choice behaviour

Every year you have the opportunity to choose a different health insurer or health insurance policy. Perhaps you have changed or you have chosen to stay with your current insurer. The following questions are about this choice.

In the next section, we will ask you questions about whether the tasks of the purchasing role of health insurers and the trust in this have influenced your choice of a health insurer.

1. Did you change health insurance during the last transition season 2021/2022?

◦ Yes

◦ No

◦ I don't know

2. How many times have you changed your health insurance in the past five years?

◦ Never

◦ 1 time

◦ Several times, but not every year

◦ Every year

◦ I don't know

3. Which parts of the purchasing role could be important to you when making a choice for health insurance?

4. How much influence has your trust in the way health insurers purchase care had on the choice of your current health insurer?

◦ A lot

◦ Many

◦ Reasonable

◦ Few

◦ No

◦ I don't know

6: Personal characteristics

In the next section we ask you several questions about yourself.

1. Are you a man or a woman?

◦ Man

◦ Woman

◦ Otherwise

2. What is your year of birth?

[insert drop-down list]

3. What is your highest completed education?

◦ Low

◦ Intermediate

◦ High

4. How would you assess your physical health in general?

◦ Excellent

◦ Very good

◦ Good

◦ Fair

◦ Poor

5. How would you assess your mental health overall?

◦ Excellent

◦ Very good

◦ Good

◦ Fair

◦ Poor

6. How much care do you use?

◦ None

◦ Very little

◦ Little

◦ Much

◦ Very much

Closing

Thank you for completing this questionnaire.

Appendix C

Descriptive statistics

Table C1. Background characteristics of the survey sample (n = 708)

Appendix D

Table D1. Results factor analysis for the construct variables perception of appropriateness and in trust in performance of 12 purchasing tasks