1 Introduction

A recent literature in economics and psychology argues that human behavior can be understood as the interaction between two different decision systems (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2002, Reference Kahneman2011): one that is fast, intuitive, automatic and largely effortless (“System 1”), and one that is slower, more deliberate, and requires some level of reflection and cognitive effort (“System 2”). For some decisions, the two systems may diverge in the choices they favor: while deliberation may pull the individual towards a certain choice (e.g., keeping a healthy diet), intuition may pull them towards a different choice (e.g., eating tasty but highly caloric food). In these cases, an individual must use willpower and spend cognitive resources to override the intuitive impulse and take the choice favored by the deliberative system.

It has been suggested that altruistic behavior can also be rationalized by this dual-system framework (Loewenstein and O’Donoghue Reference Loewenstein and O’Donoghue2007; Moore and Loewenstein Reference Moore and Loewenstein2004; Zaki and Mitchell Reference Zaki and Mitchell2013; Deck and Jahedi Reference Deck and Jahedi2015; Dreber et al. Reference Dreber, Fudenberg, Levine and Rand2016). One of the most debated questions in this literature is whether altruism (and pro-social behavior more generally) is a spontaneous and intuitive response, where individuals must use willpower if they wish to act in their self-interest; or whether instead self-interest is intuitive, and individuals must use willpower to behave pro-socially.

A number of experiments have been designed to address this question. These experiments rely on different types of manipulations, designed to inhibit one of the systems and promote the other. For example, subjects in an experiment may be asked to distribute an amount of money between themselves and another participant (e.g., in a dictator game), while at the same time performing another task that is more or less cognitively-taxing (e.g., holding a 7-digit or 3-digit number in their memory). Compared to subjects who perform the easier task, subjects who perform the hard task are under “cognitive load”: they have fewer cognitive resources to devote to the dictator game decision, and are therefore less able to use their deliberative system when deciding how much to give to the other participant. Other commonly used types of manipulations include: “ego depletion” where subjects participate in a sequence of two tasks, the first to deplete cognitive resources, and the second to measure how the consequent reduced ability to use deliberation affects behavior; “time pressure” where subjects are forced to make a decision either quickly or after having deliberated for some time; and “priming” where subjects are consciously or subconsciously encouraged to decide using either their intuitive or deliberative system.

In this paper, we report a meta-analysis of the experimental studies that have used cognitive load, ego depletion, time pressure, and priming to study the effects of promoting intuition on altruistic behavior. Our meta-study covers 22 papers involving a total of 60 experiments and more than 12,000 subjects. We find that in 57% of the experiments, promoting intuition leads to more self-interested behavior, suggesting that self-interest is an intuitive response. In the other 43% of experiments promoting intuition encourages more altruistic behavior, suggesting that altruism, and not self-interest, is intuitive. These effects, however, are statistically significant only in a minority of studies. In the large majority of cases (78% of experiments), the effect of promoting intuition is insignificantly different from zero. The overall effect size estimated across all 60 experiments is only − 0.015, and we cannot reject the null hypothesis that this is actually zero.

It is unclear how to interpret this evidence. On the one hand, taken at face value, the fact that the literature has found effects in either direction, and an average estimated effect close to zero, may suggest that the true underlying effect is actually very small or non-existent, and that the few significant effects reported in the literature are false positives. That is, altruism is neither fast nor slow: this type of behavior simply escapes the logic of the dual-system framework.

On the other hand, some researchers have argued that whether intuition favors altruism or self-interest may depend on a variety of individual, social, and contextual factors. While for some subgroups of individuals in some specific situations intuition may favor altruism, for other subgroups or situations intuition may favor self-interest (e.g., Hauge et al. Reference Hauge, Brekke, Johansson, Johansson-Stenman and Svedsäter2016; Rand et al. Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016; Grossman and Van der Weele Reference Grossman and Van der Weele2017; Balafoutas et al. Reference Balafoutas, Kerschbamer and Oexl2018). That is, the mixed results reported in the literature could simply reflect a genuine heterogeneity in the underlying decision processes that different individuals use in different situations—and since this heterogeneity is typically unanticipated and unaccounted for in most existing studies, this could explain why the reported overall effect is small and close to zero in most of the literature.

To assess the role of heterogeneity in explaining the mixed results found in the literature, we conduct a mediator analysis to identify factors that may account for systematic differences across studies in the size and direction of the effect of intuition on altruism. We examine a variety of factors that have been proposed in the literature as possible mediators of the effect, including gender (Rand et al. Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016), the frame of the game (Hauge et al. Reference Hauge, Brekke, Johansson, Johansson-Stenman and Svedsäter2016; Banker et al. Reference Banker, Ainsworth, Baumeister, Ariely and Vohs2017; Gärtner Reference Gärtner2018), and the experimental stakes (Mrkva Reference Mrkva2017; Andersen et al. Reference Andersen, Gneezy, Kajackaite and Marx2018). With the possible exception of the frame of the game, for which we find mixed support, we find no evidence that any of the factors we consider can explain the variance in effect sizes across studies. For gender, a previous meta-analysis by Rand et al. (Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016) found that promoting intuition has significantly different effects for women and men: the effect is positive and significant for women, but negative and insignificant for men. If anything, our analysis, which subsumes most of Rand et al.’s data and is based on a much larger number of studies, finds the opposite: the effect is negative for both women and men (significantly so only for the latter), and we cannot reject the null of no difference in the size of the effect between genders.

These results lend little support to the argument that there may be a genuine heterogeneity in the size and direction of the effect of intuition on altruism across different subsamples and that this may explain the mixed evidence reported in the literature about the overall effect of intuition on altruism. To further probe this conclusion, in the last part of the paper we report a new experimental test of the hypothesis that altruistic behavior responds to the logic of the dual-system model. While existing studies have tested this hypothesis by studying whether promoting System 1 makes individuals more altruistic or more self-interested, we examine whether making choices that involve a trade-off between altruism and self-interest triggers a conflict between the two systems that is cognitively taxing and willpower-depleting. An advantage of our experimental test is that, unlike existing experiments, it is robust to the presence of heterogeneity in whether System 1 favors altruism or self-interest. Even if System 1 is altruistic for some individuals and self-interested for others, both types of subjects would have to spend willpower to regulate a conflict between self-interest and altruism, as long as System 1 and 2 diverge in the behavioral motive that they favor. We do not find evidence that facing a trade-off between self-interested and altruistic choices depletes willpower. Taken together the results from our meta-study and our new experiment offer little support for a dual-system theory of altruistic behavior.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2 we present the findings of our meta-analysis of the existing literature. Section 3 describes the design and results of the new experiment. Section 4 concludes.

2 Meta-study

2.1 Design

We searched the literature for experimental studies investigating the effect of promoting intuition on altruistic behavior. We include studies that use one of the four standard types of interventions to promote intuition at the expense of deliberation (cognitive load, ego depletion, time pressure, or priming), and that assess the effect of these interventions of individuals’ decisions to distribute wealth between themselves and another passive player.Footnote 1 The passive player can be another participant in the experiment (as in standard dictator games), or a charitable organization (as in donation experiments). In all cases, the decisions must involve a trade-off between the decision-maker’s and passive player’s payoffs (i.e., we exclude settings in which the decision-maker can increase the passive player’s payoff at no cost for themselves; or cases where the choice that maximizes the decision-maker’s payoff also maximizes the passive player’s payoff). We require that the study adheres to the methodology of experimental economics (i.e., no deception), and that decisions have real monetary consequences for the parties involved (i.e., no hypothetical studies). For more details on the selection process, see Appendix A in the Online Supplementary Materials (OSM).

Based on our inclusion criteria, the meta-study covers 22 studies involving 60 experiments conducted with a total of 12,574 subjects across 12 countries.Footnote 2 About half of the experiments were run with university students, a third with Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) workers, and the rest with other specific non-student samples, for instance junior school students or members of the general population. About two-thirds of experiments involved some type of dictator game decision (where the passive players are other experiment participants), while the rest involved a charitable donation decision. Table A.1 lists all included studies and the number of experiments each study contributed to the meta-study.Footnote 3

For each experiment, we quantified the effect that promoting intuition had on altruistic behavior by calculating the standardized mean difference (Cohen’s d) in altruism between the experimental condition that promoted intuition and the condition that promoted deliberation.Footnote 4 In most cases, we measured altruism as the monetary amount (or fraction of endowment) that the decision-maker gives to the passive player; in studies involving binary dictator decisions, we used the fraction of decision-makers sacrificing own payoff to increase the passive player’s payoff.Footnote 5 In all cases, a positive effect size indicates that individuals became more altruistic when intuition was promoted, relative to the condition that promoted deliberation. In contrast, a negative effect size indicates that promoting intuition made individuals more self-regarding.

2.2 Results

Figure 1 contains a forest plot showing, for each of the 60 experiments included in our study, the associated effect size and 95% confidence interval.Footnote 6 The figure is divided into four panels, one for each type of intervention included in the meta-study. In each panel, the bottom row reports the average effect size and associated confidence interval of each intervention, estimated using a random-effects meta-analysis model. The last row of the figure reports the overall effect size estimated across all four types of interventions.

Fig. 1 Results of the random-effects meta-analysis of promoting intuition on altruism.

Note: Effect sizes (ES) measured as standardized mean difference in altruism between conditions where intuition or deliberation were promoted. Positive values imply more altruism in the intuitive condition. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The size of the grey boxes indicates the weight of the effect size in the meta-analysis (the relative weights are also reported in the last column of the figure). In each panel of the figure, the row labeled “Subtotal” reports the average effect size for each type of intervention, estimated by the random-effects meta-analysis model. The last row of the figure (labeled “Overall”) reports the average effect size across all experiments and its associated confidence interval. For a legend of the experiment IDs refer to Table A.1 in the OSM

For each type of intervention, there are experiments associated with both negative and positive effect sizes. Across the four types of interventions, 57% of experiments report a negative effect of promoting intuition, while the remaining 43% report a positive effect. In most cases, however, the 95% confidence interval of the effect size includes zero. Only in 13 out of 60 experiments (22% of cases) does the confidence interval not contain zero: in 8 cases the estimated effect size is negative, and in the remaining 5 cases it is positive.

As a consequence, the average effect size of each type of intervention is very small and not different from zero at the 5% significance level or lower: 0.021 for cognitive load studies (p = 0.766), − 0.034 for time pressure studies (p = 0.349), − 0.025 for ego depletion studies (p = 0.803), and 0.012 for priming studies (p = 0.858). Across all types of interventions, the overall effect size is − 0.015, with an associated 95% confidence interval of [− 0.070, 0.041]. We cannot reject the null that the overall effect size is actually zero (z = 0.51, p = 0.607).

Based on these results, what should we conclude about the role of intuition and deliberation for altruistic behavior? The face-value interpretation of our findings is that promoting intuition has only a very small (if any) effect on altruistic choices. Thus, one may conclude that the logic of the dual-system model does not extend to altruistic behavior.

However, several researchers have suggested that the mixed evidence concerning the overall effect of promoting intuition on altruism may reflect a genuine heterogeneity in the size and direction of the effect across different subgroups of the population, or across different decision settings. That is, the researcher may observe no aggregate effect of the intervention on altruistic behavior, when in fact the manipulation may have led a subgroup of subjects to become more altruistic and another subgroup to become more self-regarding—with the two opposing effects cancelling each other out in the aggregate.

Rand et al. (Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016) for instance, propose that what is automatized as an intuitive response depends on the strategies that are typically advantageous in one’s daily social interactions. They argue that what constitutes a socially advantageous strategy may vary across individuals or groups, and propose that gender may be an important moderating factor in the case of altruism: altruism may be an intuitive social response for women, but less so for men. Other researchers have argued that the underlying pro-social inclinations of the individual may moderate the effect of intuition on altruism: while altruism may be an intuitive response for pro-social types, the opposite may be true for self-interested types (e.g., Balafoutas et al. Reference Balafoutas, Kerschbamer and Oexl2018; Chen and Krajbich Reference Chen and Krajbich2018). Moreover, some researchers have focused on contextual and situational factors as possible mediators of the effect of promoting intuition on altruism. Andersen et al. (Reference Andersen, Gneezy, Kajackaite and Marx2018) and Mrkva (Reference Mrkva2017), for instance, examine the role of experimental stakes. Banker et al. (Reference Banker, Ainsworth, Baumeister, Ariely and Vohs2017) propose that there is an interaction between the effect of promoting intuition and whether the decision situation uses a “giving” or “taking” frame: in the former case, manipulations that promote intuition may decrease altruism, while in the latter case they may increase altruism.

However, because the evidence of heterogeneous effects inevitably relies on multiple tests of the same hypothesis (e.g., separate tests among men and women of the hypothesis that intuition promotes altruism), a potential concern is that some of the reported heterogeneous effects may actually be false positives rather than reflect a genuine heterogeneity in the effect for different subgroups or contexts. The problem may be exacerbated in cases where the multiple comparisons are the result of data-dependent analyses, a phenomenon that has been referred to as “forking” (e.g., Gelman and Loken Reference Gelman and Loken2013). Moreover, the problem may be further amplified when the reported heterogeneous effects are discovered by aggregating data from several studies that contain false-positive results, as it may be the case in “internal meta-analyses” where inferences are based on the aggregated analysis of multiple experiments reported in the same paper (Vosgerau et al. Reference Vosgerau, Simonsohn, Nelson and Simmons2018).

In the next section, we use the meta-study to assess the extent to which various individual and situational factors discussed in the literature can explain the variance in effect sizes across experiments included in our analysis. The advantage of this approach is that we can test the role of each factor by relying on information from papers that did not necessarily focus on that factor to organize their own data. For instance, we can test the hypothesis that intuition promotes altruism among women but not among men, by combining data from studies that did and did not analyze the effect disaggregated by gender. Since we can rely on information from variables that the original authors may not have used in their analysis or publication decisions, this approach potentially mitigates the bias introduced by data-dependent analyses.

2.3 Mediator analysis

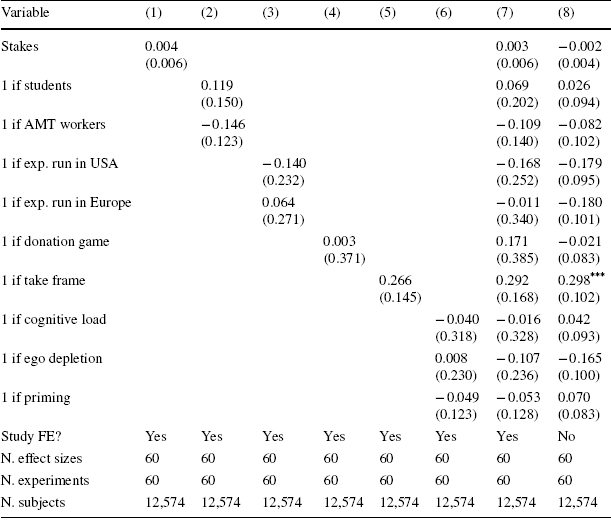

We examine the extent to which the effect of promoting intuition on altruism may be moderated by a long list of factors discussed in the literature, namely: the role of gender; the type of intervention used to manipulate cognitive resources; the frame of the game (give or take); the nature of the passive player (another participant or a charity); the stakes used in the experiment, the type of subject pool used to conduct the study (e.g., students, AMT workers, etc.); and the location where the experiment was run. For each factor, we conduct a random-effects meta-regression where the dependent variable is the effect size detected in the experiment, and where each experiment is weighted by the inverse of its variance so that more precise studies have more influence in the analysis. The regressions for these variables (with the exception of gender, discussed below) are reported in Table 1.

Table 1 Mediator analysis: random-effects meta-regressions

|

Variable |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stakes |

0.004 (0.006) |

0.003 (0.006) |

− 0.002 (0.004) |

|||||

|

1 if students |

0.119 (0.150) |

0.069 (0.202) |

0.026 (0.094) |

|||||

|

1 if AMT workers |

− 0.146 (0.123) |

− 0.109 (0.140) |

− 0.082 (0.102) |

|||||

|

1 if exp. run in USA |

− 0.140 (0.232) |

− 0.168 (0.252) |

− 0.179 (0.095) |

|||||

|

1 if exp. run in Europe |

0.064 (0.271) |

− 0.011 (0.340) |

− 0.180 (0.101) |

|||||

|

1 if donation game |

0.003 (0.371) |

0.171 (0.385) |

− 0.021 (0.083) |

|||||

|

1 if take frame |

0.266 (0.145) |

0.292 (0.168) |

0.298*** (0.102) |

|||||

|

1 if cognitive load |

− 0.040 (0.318) |

− 0.016 (0.328) |

0.042 (0.093) |

|||||

|

1 if ego depletion |

0.008 (0.230) |

− 0.107 (0.236) |

− 0.165 (0.100) |

|||||

|

1 if priming |

− 0.049 (0.123) |

− 0.053 (0.128) |

0.070 (0.083) |

|||||

|

Study FE? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

N. effect sizes |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

|

N. experiments |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

|

N. subjects |

12,574 |

12,574 |

12,574 |

12,574 |

12,574 |

12,574 |

12,574 |

12,574 |

Dependent variable is the effect size associated to an experiment

The last two columns of Table 1 report specifications where all mediators are simultaneously included in the regression. In column (7) we include study dummies—not reported in the table—to account for study fixed effects (these are also included in all regressions of columns 1–6), while in column (8) we report a specification without study fixed effects (see Table A.3 in the OSM for versions of regressions 1–6 without study fixed effects). There are advantages and disadvantages to either specification. The study fixed-effects specification exploits within-study variation in the mediators of interest, controlling for potential unobservable idiosyncrasies of the individual studies (e.g., specific characteristics of the subject pool used in a given study). This is a very clean form of identification, especially for variables that the researcher has randomized at the study level (e.g., take or give frame treatments). However, the large number of study dummies (22) compared to the relative small number of observations (60) raises potential concerns about overfitting. Moreover, removing the study fixed-effects allows to exploit between-study variation in the mediators of interest, which, as discussed earlier, is valuable if one is concerned that the choice of treatments within a study may have been partly data-driven. As we show below, although estimates vary between the two approaches, the two identification strategies lead to the same conclusions in all but one case (the effect of the frame of the game).

Stakes Some authors have argued that whether intuition favors altruism or self-interest depends on the amount of money at stake in the decision situation. For instance, Mrkva (Reference Mrkva2017) argues that when stakes are high, an individual’s impulsive response is to reject a request for money, and that generosity may thus be fostered by deliberation, while the reverse may happen when stakes are low. The stake level is defined as the maximum payoff available to the decision-maker (e.g. in a dictator game, the endowment received by the dictator), converted in 2017 USD PPP and multiplied by the probability that this amount is actually paid to the subject (in several studies not all choices made by subjects are paid with certainty, either because the study uses role uncertainty or because the giving decision is part of a set of tasks and the random lottery incentive system is used).Footnote 7 Column (1) of Table 1 reports the regression results. We do not find any significant association between stake level and effect size (p = 0.522). We find the same result in the regressions of columns (7) and (8), where we control for other mediators. We conclude that stakes are not a significant mediator of the effect of intuition on altruism.

Sample In column (2) we investigate whether there is heterogeneity in the effect sizes associated with different types of samples with which the experiments were run (students, AMT workers, etc.). The base category in the regression are studies run with non-student samples that are not AMT workers. We do not detect any significant differences between the base category (n. experiments = 7) and AMT workers (n = 20) or students (n = 33). We also do not find any significant difference between AMT workers and students (F-test: p = 0.129). This is also true for the regressions in columns (7) and (8).

Location of the experiment In column (3) we explore whether the location where the experiment was run affects the estimate of the effect size. About half of the experiments were run in the US (n = 31), about a third in Europe (n = 23), while the rest in other countries such as Chile, India, Israel or Tunisia (the base category in the regression, n = 7).Footnote 8 We do not detect any difference between experiments run in Chile, India, Israel or Tunisia and those run in the US or Europe, nor do we find a difference between Europe and the US (F-test: p = 0.151). The same holds for the regressions in columns (7) and (8).

Charity as passive player About a third of experiments were based on donation games (n = 17), where decision-makers decide how much money to donate to a charitable organization. We do not find that the effect sizes in these studies differ from those reported in the dictator game experiments, as shown in columns (4), (7) and (8).

Frame of the game Banker et al. (Reference Banker, Ainsworth, Baumeister, Ariely and Vohs2017) argue that the framing of the decision situation plays an important role in determining whether altruism or self-interest are an intuitive response. This is because intuition may favor choices that are salient. When the choice involves taking money that has been initially allocated to the passive player, the salient cue is to leave the amount with the passive player, and therefore promoting intuition will lead to more altruism. The reverse may happen when the choice involves giving money that has been initially allocated to the decision-maker. Gärtner (Reference Gärtner2018) entertains a similar hypothesis. Hauge et al. (Reference Hauge, Brekke, Johansson, Johansson-Stenman and Svedsäter2016) also report games with either give or take frames. In column (5) we test whether experiments using a take frame (n = 8) are associated with larger effect sizes (indicating more altruism in the intuitive condition) than experiments using a give frame. The coefficient of the take frame dummy is indeed positive but not significantly different from zero at the 5% level or lower (p = 0.074). The same holds in column (7) (p = 0.093). However, in column (8), where we do not control for study fixed effects and exploit both within- and between-study variation in the frame of the game, we find a statistically significant positive effect (p = 0.005). Based on these analyses, we tentatively suggest that the frame of the game might be a mediator of the effect of intuition on altruism, although more research on this specific factor seems warranted given the mixed results.

Type of intervention In column (6) we test whether there are systematic differences between the effect sizes reported in studies that use different types of manipulation of cognitive resources. For instance, one may hypothesize that some types of manipulations (e.g. priming manipulations that prompt participants to consider the positive effects of “carefully reasoning through a problem”) may be more prone to demand effects than others, and thus promote a stronger effect. We thus include dummies for experiments relying on cognitive load (n = 15), ego depletion (n = 9), and priming (n = 9), with time pressure experiments (n = 27) as the base category.Footnote 9 We do not find any difference between types of manipulation, in any of the possible bilateral comparisons (all p > 0.690). The same holds for the regressions in columns (7) and (8).

Gender Rand et al. (Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016) propose that gender is an important mediator of the role of intuition and deliberation on altruism. They argue that altruism may be an intuitive response for women more than for men. In their meta-study, they indeed find a significant difference between effect sizes for men and women. Moreover, in line with their hypothesis, they find that the estimated effect size is positive and significant for women, while negative and insignificant for men (they use 5% as the probability of type-I error in their study, as we do in this paper).

For nearly all studies in our meta-analysis we can compute separate effect sizes for men and women and thus re-test the hypothesis put forward by Rand et al. (Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016) with a much larger sample than they had available in their meta-study (50 experiments involving 10,728 subjects compared to 22 experiments and 4366 subjects in Rand et al.). Table 2 reports random-effect meta-regressions based on the subsample of experiments for which we can compute gender-specific effect sizes.

Table 2 Mediator analysis: the role of gender

|

Variable |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 if female |

0.052 (.041) |

0.054 (.041) |

0.054 (.049) |

0.053 (.044) |

|

Study FE? |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Additional controls? |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

N. effect sizes |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

N. experiments |

50 |

50 |

50 |

50 |

|

N. subjects |

10,728 |

10,728 |

10,728 |

10,728 |

Random-effects meta-regressions. Dependent variable is the effect size associated to an experiment. The additional controls are the other mediators examined in Table 1

In column (1) we only include a gender dummy as well as study dummies to control for study fixed effects, while in column (2) we also add the mediators listed in Table 1 as additional controls. In columns (3) and (4) we report analogous specifications but without study fixed effects. In all cases, we only detect a small difference between effect sizes for men and women, which is not statistically significant (p > 0.193).

Figure 2 further illustrates this result. It contains forest plots showing the effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals of the 50 experiments used in the gender analysis. The top panel of the figure shows the forest plot for men, while the bottom panel shows the plot for women. The last row of each panel reports the overall effect size estimated across all experiments.

Fig. 2 Effect sizes for men (top panel) and women (bottom panel).

Note: Effect sizes (ES) measured as standardized mean difference in altruism between conditions where intuition or deliberation were promoted. Positive values imply more altruism in the intuitive condition. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The size of the grey boxes indicates the weight of the effect size in the meta-analysis (the relative weights are also reported in the last column of the figure). The last row of the figure (labeled “Overall”) reports the average effect size across all experiments and its associated confidence interval. For a legend of the experiment IDs refer to Table A.1 in the OSM

In either case the gender-specific effects sizes are quite small. For men, the overall effect size is negative (− 0.079) and we can reject the null that the effect size is not zero at the 1% level (p = 0.002). For women, the overall effect size is also negative (− 0.008), but not different from zero at any conventional level of significance (p = 0.843). Thus, our results are in contrast with the findings reported by Rand et al. (Reference Rand, Brescoll, Everett, Capraro and Barcelo2016), who found that promoting intuition increases altruistic behavior among women, but has no effect among men.Footnote 10

Note that the sample we used to conduct the gender analysis differs in two ways from Rand et al.’s sample: we have added 32 experiments from 17 studies that were not available to Rand et al. at the time of their meta-analysis, and we have excluded 4 experiments from 2 studies that Rand et al. had included, because they involved deception. Is the difference in results between our meta-analysis and Rand et al.’s due to the addition of new studies, or to the exclusion of the studies that involved deception? We repeated the analysis above using only the studies included in Rand et al. except those that involved deception. We can replicate Rand et al.’s results in this subsample: for men the overall effect size is negative (− 0.078), but insignificant at the 5% level or lower (p = 0.087), while for women the overall effect size is positive (0.135) and significant (p = 0.003). We then performed the analysis using only the new studies that were not available to Rand et al. In this case, the effect size is negative for both men (− 0.066) and women (− 0.070), and insignificantly different from zero at the 5% significance level or lower for either group (p = 0.063 for men; p = 0.139 for women). Thus, the difference in results is due to the addition of the 32 experiments that were not included in Rand et al.Footnote 11

Taken together, our results lend little support to the argument that there may be genuine heterogeneity in the size and direction of the effect of intuition on altruism across different subsamples, and that this may explain the mixed evidence reported in the literature about the overall effect of intuition on altruism. We think that the most likely explanation for the conflicting evidence reported in previous studies (and reproduced in our meta-analysis) is that this actually reflects contrasting false positive results. To further probe this conclusion, in the next section we report results from a novel experimental paradigm that, as we explain below, may allow to identify the effect of intuition on altruism even in the presence of heterogeneity in the direction of the effect triggered by the manipulation of cognitive resources.

3 New experiment

The starting point of our experimental design is the observation that, if choices that involve trade-offs between altruism and self-interest trigger a conflict between intuition and deliberation, then individuals exposed to such trade-offs will have to consume cognitive resources and willpower to regulate this conflict. Note that this is true regardless of whether one’s theory proposes that altruism is intuitive and self-interest deliberate, or whether it proposes instead that self-interest is intuitive and altruism deliberate. In the former case, willpower is required to rein in the pro-social impulse; in the latter it serves to override the selfish impulse. In either case, the individual will have to use willpower when they face decisions that involve a trade-off between altruism and self-interest. In other words, these trade-offs are willpower-depleting.

This implies a straightforward prediction: individuals exposed to trade-offs between altruism and self-interest will have less willpower available for subsequent tasks that also require the use of willpower. A crucial advantage of this prediction is that it holds irrespective of whether altruism or self-interest are intuitive: it only requires that the intuitive process diverges from the deliberate process so that a conflict between the two systems arises. Therefore, the presence of heterogeneity in the direction of the effect does not constitute a problem. Even if intuition promotes self-interest for a subgroup of subjects while it promotes altruism for another subgroup, both subgroups will experience a conflict when exposed to trade-offs between altruism and self-interest, and this will affect the cognitive resources that both types of subjects have access to in subsequent tasks.

3.1 Experimental design

We test this prediction in a new experiment where we reverse the order of tasks typically used in ego depletion experiments: we use a series of 16 dictator games as the first, willpower-depleting task; and a second cognitively-demanding and willpower-requiring task (a version of the Stroop Reference Stroop1935 color-word task)" to be consistent with the way citations appear when parentheses are used elsewhere in the paper, to measure the effect of participating in the dictator games on residual willpower.

In the first task, subjects were randomly matched in pairs to participate in the 16 dictator games shown in Table 3. In each pair, one subject was allocated the role of dictator and the other the role of recipient. Pairs and roles were kept fixed across the 16 games. Across two between-subject treatments, we manipulated the extent to which the dictator games required exertion of willpower by varying the structure of payoffs of the games. In the 16 games of our Conflict treatment, the option that maximized the dictator’s payoff always minimized the recipient’s payoff. Thus, in this treatment dictators faced a series of trade-offs between self-interested and altruistic choices, as is customary in standard dictator games. In our NoConflict treatment, we removed this trade-off by manipulating payoffs so that the option that maximized the dictator’s payoff also maximized the recipient’s payoff.

Table 3 Payoffs in the binary dictator games

|

Conflict |

NoConflict |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Game |

Option A |

Option B |

Option A |

Option B |

|

1 |

8; 8 |

12; 0 |

8; 0 |

12; 8 |

|

2 |

11; 1 |

8; 8 |

11; 8 |

8; 1 |

|

3 |

9; 1 |

7; 5 |

9; 5 |

7; 1 |

|

4 |

7; 5 |

8; 2 |

7; 2 |

8; 5 |

|

5 |

10; 6 |

12; 0 |

10; 0 |

12; 6 |

|

6 |

8; 8 |

16; 0 |

8; 0 |

16; 8 |

|

7 |

6; 6 |

8; 4 |

6; 4 |

8; 6 |

|

8 |

10; 2 |

9; 7 |

10; 7 |

9; 2 |

|

9 |

12; 0 |

6; 6 |

12; 6 |

6; 0 |

|

10 |

11; 5 |

15; 1 |

11; 1 |

15; 5 |

|

11 |

8; 4 |

10; 2 |

8; 2 |

10; 4 |

|

12 |

9; 3 |

8; 4 |

9; 4 |

8; 3 |

|

13 |

10; 6 |

8; 8 |

10; 8 |

8; 6 |

|

14 |

13; 3 |

10; 6 |

13; 3 |

10; 3 |

|

15 |

6; 6 |

8; 2 |

6; 2 |

8; 6 |

|

16 |

10; 0 |

6; 4 |

10; 4 |

6; 0 |

In each game, dictators could choose between two options, A or B, each implying a different distribution of money between themselves and the recipient. For each option, the first number indicates the dictator’s payoff and the second number the recipient’s payoff (both displayed in GBP). In both treatments, the 16 games were presented to subjects in the same order as shown in the table

In both treatments, subjects then participated in a version of the Stroop (Reference Stroop1935) color-word task, which is often used to measure willpower depletion.Footnote 12 Subjects were shown, for five minutes, a series of words of color names printed in various font colors. Both color names and font colors were either black, blue, green, red, or yellow. The font colors and color names were randomly matched so that, for each word, the font color did not correspond to the color name. Subjects had to indicate, for each word, which color it was printed in, and not the color that the word read.Footnote 13 This task requires regulation of choice because, in order to submit a correct answer, subjects must override their intuitive and automatic impulse to respond by reading the color name of the word, and look at its font color instead. Thus, the task demands continuous exertion of willpower by the participant to regulate the conflict that arises between their intuitive and deliberative systems.

If willpower is a resource that can be depleted with use (Muraven and Baumeister Reference Muraven and Baumeister2000; Baumeister et al. Reference Baumeister, Vohs and Tice2007), and if the 16 games of the Conflict treatment require more use of willpower than the corresponding games of NoConflict, then we would expect dictators in Conflict to arrive at the Stroop task with less residual willpower than those in NoConflict, and therefore to be comparatively less able to expend further willpower during the Stroop task. In Sect. 3.3, we test this hypothesis by comparing the number of correct answers given by dictators in the Stroop task between our two treatments.

Note that the crucial assumption underlying our test is that the trade-offs faced by dictators in the 16 games of the Conflict treatment trigger a series of motivational conflicts that are depleting in terms of willpower, whereas such conflicts (and hence willpower depletion) do not arise in the NoConflict treatment. The rationale for this assumption is based on recent findings from the depletion literature that making choices, particularly choices that involve large trade-offs between options, is costly in terms of willpower. Vohs et al. (Reference Vohs, Baumeister, Schmeichel, Twenge, Nelson and Tice2008), for instance, show that even mundane, small-cost choices (e.g., choosing between different colored t-shirts) cause willpower depletion as measured in a series of tasks that require exertion of self-control (e.g., making oneself drink an unsavory beverage; or submerging one’s arm in cold water). Spears (Reference Spears2011) reports analogous findings using a Stroop-like task to measure willpower depletion. Moreover, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Novemsky, Dhar and Baumeister2010) show that choices involving large trade-offs are more depleting than choices involving small trade-offs. These findings suggest that, to the extent that dual-system theories extend to altruistic behavior, the trade-offs implied in the 16 games of the Conflict treatment should in principle also be willpower-depleting.

Of course, an ancillary assumption for our test is that the induced depletion of willpower is large enough to produce a detectable effect given the statistical power of the experiment.Footnote 14 Thus, our design includes a series of elements aimed at strengthening the effect and hence maximizing the chances of detection. First, based on the evidence that the extent to which willpower is depleted is positively related to the duration of the depleting task (Vohs et al. Reference Vohs, Baumeister, Schmeichel, Twenge, Nelson and Tice2008; Hagger et al. Reference Hagger, Wood, Stiff and Chatzisarantis2010), we had dictators face 16 decision problems, each time with different payoffs, so that they were forced to reconsider their choice each time a new game was presented to them.Footnote 15 Moreover, we chose to decrease dictator-recipient anonymity and to have recipients interact with dictators throughout part one in order to reduce social distance between dictators and recipients and create a starker conflict between altruism and self-interest.Footnote 16

In order to test whether we were successful in creating a perceivable conflict between altruistic and self-interested motives in the Conflict treatment, we included in the post-experimental questionnaire, as a manipulation check, two questions asking dictators to rate the extent to which they found the dictator game choices “hard” and “uncomfortable”.Footnote 17 Dictators in the Conflict treatment reported that choices in the dictator games were harder and more uncomfortable relative to dictators in NoConflict (hard: mean 3.07, s.d. 2.64 vs. mean 0.84, s.d. 1.75; discomfort: mean 4.12, s.d. 3.26 vs. mean 1.05, s.d. 1.90). For both questions, we find that responses are significantly different across the two treatments (Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests; hard: p < 0.001; discomfort: p < 0.001).Footnote 18 This suggests that dictators in the Conflict treatment may have indeed perceived a stronger motivational conflict than dictators in NoConflict. In Sect. 3.3, we test whether the (perceived) stronger conflict resulted in a more severe depletion of willpower as measured by dictators’ Stroop task performance across the two treatments.

3.2 Experimental procedures

The experiment was programmed in z-Tree (Fischbacher Reference Fischbacher2007) and was conducted at the University of Nottingham using students from a wide range of disciplines recruited through the online recruitment system ORSEE (Greiner Reference Greiner2015). We have 396 subjects in total across 13 sessions, equally divided between the two treatments. Thus, our analysis is based on 99 dictators per treatment. This implies that we can detect effects of size 0.40 or larger (Cohen’s d) with 80% power and 5% probability of a type-I error, using a two-sided Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test.

We report a detailed description of the procedures used in the experiment in Appendix B in the OSM and reproduce the experimental instructions in Appendix C. We paid subjects using a random incentive lottery system. At the end of each session, one of the two parts of the experiment was selected at random and subjects were paid according to their earnings from the selected part. If part one was selected, one of the 16 games was chosen at random and subjects were paid according to their earnings in that game. Sessions lasted approximately 50 min and earnings ranged between GBP0 and GBP19, averaging GBP11.81 (s.d. 4.77).

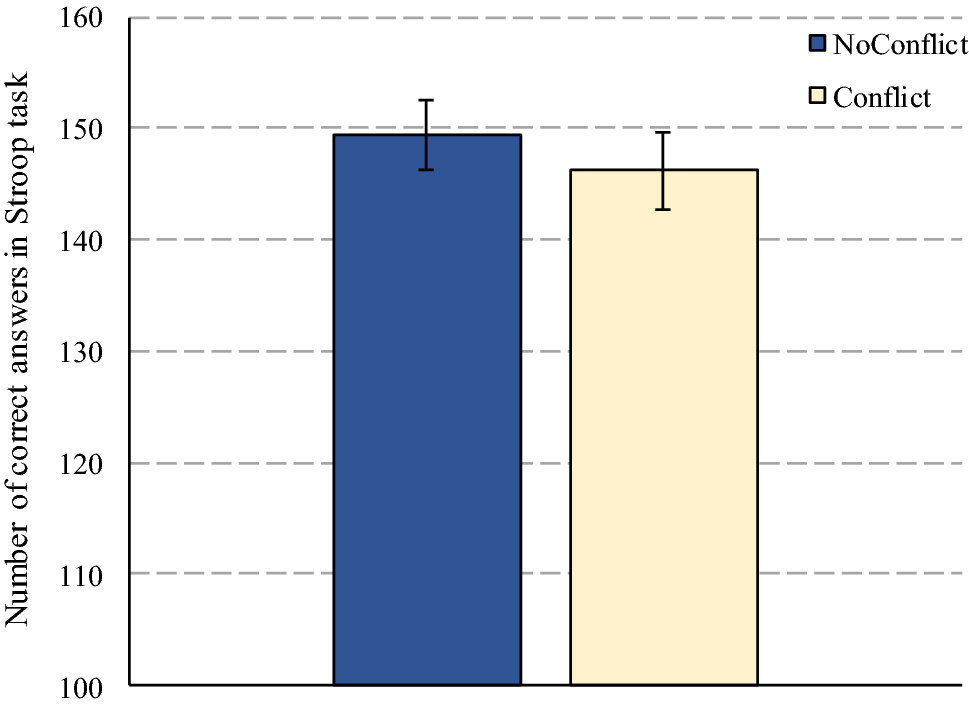

3.3 Dictators’ performance in the Stroop task

Figure 3 shows the average number of correct answers in the Stroop task by dictators in the Conflict and NoConflict treatments. Dictators in Conflict gave fewer correct answers compared to NoConflict (Conflict: mean 146.21, s.d. 17.67; NoConflict: mean 149.44, s.d. 15.82). The resulting effect size (measured as Cohen’s d) is − 0.192. The difference in performance is not statistically significant according to a Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test (p = 0.157). An OLS regression (reported in Appendix D in the OSM) confirms that the difference in performance remains insignificant after controlling for a number of observable characteristics of the subjects (including gender) and of the decision setting.Footnote 19

Fig. 3 Performance in the Stroop task, by treatment.

Note: Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals computed as

![]() where

where

![]() is the estimated mean,

is the estimated mean,

![]() is its standard error, and 1.96 is the z-score for the 97.5 percentile point of the normal distribution

is its standard error, and 1.96 is the z-score for the 97.5 percentile point of the normal distribution

4 Discussion and conclusions

In this paper, our aim was to probe the validity of a dual-system approach to altruistic behavior, by testing the hypothesis that trade-offs between self-interest and altruism trigger a conflict between our “fast”, intuitive System 1 and our “slower”, more deliberative System 2. We performed a meta-analysis of the existing literature on the relation between altruism and intuition/deliberation and found that the manipulations used in previous experiments to promote the intuitive system at the expense of the deliberative system (using ego depletion tasks, cognitive load, time pressure or priming) have an overall effect on altruism that is very close to, and not significantly different from, zero.

Can this aggregate null result be due to the fact that the relation between altruism and our two systems is genuinely heterogeneous across different subgroups and decision situations, as some researchers have suggested? We find little evidence that this may be the case. We first run a mediator analysis based on the existing literature and consider a number of potential mediators of the relation between intuition and altruism (including mediators previously suggested in the literature, such as gender, the stakes of the experiment, or the frame of the task). We find that none of the mediators included in the analysis play a significant role in explaining the mixed results in existing studies. One possible exception is the frame of the task, for which we find evidence of a mediating effect in some specifications of the analysis, but not in others.

We then designed and ran a new experiment that allowed us to probe the validity of dual-system theories of altruism without being vulnerable to the presence of unobserved and/or unanticipated heterogeneity in the relation between altruism and intuition. We argue that, if trade-offs between altruism and self-interest trigger a conflict between the intuitive and deliberative systems, then being exposed to these trade-offs should be willpower-depleting. We do not find evidence that this is the case. Directionally, the effect is in line with the hypothesis: subjects who were exposed to trade-offs between altruism and self-interest perform worse on a task that requires willpower than subjects who were not exposed to such trade-offs. However, we cannot reject the null that the two groups perform similarly.Footnote 20

Overall, the combination of evidence from the meta-study and the new experiment suggests that choices that involve trade-offs between altruism and self-interest do not trigger any strong conflict between intuition and deliberation. This could be because, in the realm of altruistic behavior, the decision processes governed by the intuitive and deliberative systems may actually both lead to the same outcome for any given individual. That is, the two systems are not actually in conflict when it comes to making these type of decisions, and hence their outcome is the same. Alternatively, the null results reported in the literature and in our new experiment could mean that the lens of dual-system models does not extend to altruistic behavior. In either case, our study offers little support for the notion that, in the domain of altruistic choices, the individual must spend cognitive resources to override the intuitive impulse when the person wants to take a choice favored by the deliberative system.

Acknowledgements

We thank Valerio Capraro, John Duffy, Dirk Engelmann, Johannes Lohse, Fabio Tufano, Roberto Weber, two anonymous referees, and participants at the CeDEx Brownbag seminar, the 2015 Inaugural RES Symposium of Junior Researchers, and the 2015 ESA European meeting, for helpful comments. We thank Carlos Alos-Ferrer, Valerio Capraro, Manja Gärtner, Zack Grossman, Eliran Halali, Karen Evelyn Hauge, Guy Itzchakov, Agne Kajackaite, Judd Kessler, Michał Krawczyk, Johannes Lohse, Kellen Mrkva, Jonathan Schulz, and Eirik Strømland for sharing the data of their studies with us. This work was supported by the University of Nottingham and the British Academy & Leverhulme Trust (grant number SG140436). The paper was previously circulated under the title: “Do Tradeoffs between Self-interest and Other-Regarding Preferences Cause Willpower Depletion?”.

μ±1.96∗SEμ

μ±1.96∗SEμ μ

μ SEμ

SEμ